?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Religiosity in early childhood is an important, but underexamined, area of research, particularly in terms of parental influence. This study examines potential “transmission enhancers” in the association between parental and children’s religiosity in early childhood, ages 3 to 6. Overall, we hypothesized that parental religiosity will be positively associated with children’s religiosity. We examined religiosity for 235 dyads from Roman Catholic families through three dimensions: religious social identity, prayer, and God concept. We further tested four potential moderators which can enhance the association between parental and child religiosity, i.e. transmission. We considered one child variable (i.e. child age) and three familial variables (i.e. internalized parental religious motivation, active parental-child involvement, and credibility-enhancing displays). We expected that child age, internalized parental religious motivation, active parental-child involvement, and credibility-enhancing displays would strengthen the association between parental and children’s religiosity. However, for parents with lower religiosity, we hypothesized that none of these variables would moderate the link to child religiosity. Multivariate regression analysis of moderators with interactions did not show a significant effect of transmission enhancers but highlighted the importance of the child’s age as a predictor of children’s religiosity. Implications of transmission enhancers in the context of family religiosity are discussed.

Introduction

There is a significant association between parental and children’s religiosity from middle childhood to emerging adulthood (Stearns & McKinney, Citation2019a). Yet, this association in early childhood is relatively under-studied (Zammit & Taylor, Citation2023). In part, studying religiosity in the early years poses methodological challenges as such development co-occurs with significant cognitive, linguistic, and social development (e.g., Barrett et al., Citation2001; Boyatzis, Citation2005; Nyhof & Johnson, Citation2017). However, between ages 3–6, children develop an understanding of key religious concepts such as symbols (e.g., Connolly et al., Citation2002), prayer (e.g., Phelps & Woolley, Citation2001), and God (e.g., Barrett et al., Citation2001). Given the scarcity of research on this age group, important empirical questions about the possible transmission enhancers of the association between parental and children’s religiosity remain. First, which dimensions of parental religiosity influence children’s religiosity? Second, which factors enhance this transmission? We investigate the distinct associations between different dimensions of parental religiosity, such as religious social identity, prayer, and God concept. We further examine how child and family factors (e.g., child age, internalized religious motivation, active parental-child involvement, and credibility-enhancing displays) might strengthen this association. Understanding the development of religiosity in early childhood may have implications across the lifespan (Jung, Citation2018) and for families with different religious motivations (Neyrinck et al., Citation2005), in particular in societies that have compulsory religious education (Faas et al., Citation2016).

Dimensions of religiosity

Religious development has been defined as “the child’s growth within an organized community that has shared narratives, practices, teachings, rituals, and symbols in order to bring people closer to the sacred and to enhance one’s relationship to community” (Boyatzis, Citation2005, p. 125). This definition highlights the importance of the community through shared practices carried out. Rooted in this definition, this study will focus on religiosity through three dimensions: religious social identity, prayer practices and rituals, and the God concept. This study examines the association of these dimensions between parents and their children (H1).

Religious Social Identity

Group belonging determines the individual’s identity and life experiences (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979). The social identity approach shifts the focus to a group, rather than an individual (Hogg & Abrams, Citation1998). The group provides a representation of who an individual is and how she/he should behave (Hogg & Abrams, Citation1998). The strength of religious social identity, for example, is linked with higher religious participation (Greenfield & Marks, Citation2007). Church attendance, such as going to mass, was linked with stronger religious social identity among Catholic mothers in Northern Ireland (Goeke-Morey et al., Citation2015). Religious social identity, however, is represented by more than participation, but also other forms of group markers, such as symbols (Taylor et al., Citation2021).

Religious social identity has been studied through symbols since it is not perceptually different for young children (Taylor et al., Citation2020). Symbols act as non-verbal testimony indicating what is valued or not in a society, helping children to process and visualize unseen entities (Harris & Koenig, Citation2006). Symbols that have a shared meaning are objectified through worship (Boyatzis, Citation2005). The cases of a Muslim teacher’s right to wear a hijab and the right to display crucifixes in the classroom appearing in the European Court of Human Rights, reflect the importance of religious symbols in childhood and in education (Fancourt, Citation2021). Moreover, children can identify ingroup symbols before they can fully explain the symbols’ meaning (Connolly et al., Citation2009). Studying religious development through symbol awareness offers an age-appropriate measure, and is consistent with broader theories of children’s social identity development (e.g., Nesdale, Citation2004). A meta-analysis shows an association between parental and children’s religiosity (Beelmann & Heinemann, Citation2014; Stearns & McKinney, Citation2019b). Given the link between parent and child social identities, more broadly, we expect religious social identity of parents and children to positively correlate. Complementing social identity and shared symbols, religiosity can also be assessed through prayer rituals and practices.

Prayer

Prayer can be both intrinsically motivated (e.g., through adoration; Laird et al., Citation2004) as well as externally motivated (to gain protection; Gorsuch & McPherson, Citation1989). When facing challenges, people often pray for three different reasons: deferred coping by giving control to God for a solution to their problem, collaborative coping with God and resolving the problem together, or self-directed coping where the person remains responsible, but God is acknowledged for his/her problem-solving skills (Pargament et al., Citation1988). Perceiving that God is responding to prayer is linked with religious belief and belief in God (Exline et al., Citation2021).

Understanding how prayer is transmitted from parents to their children involves studying how children understand prayer practice. Since prayer involves thinking or talking to an immaterial supernatural being, the process of prayer transcends the physical laws as it involves transfer of thoughts from one being to another (Phelps & Woolley, Citation2001). A study of this concept in early childhood found that children aged 5 showed fuller awareness of prayer than aged 3; most children aged 3–4 did not know how God listened to their prayer (Phelps & Woolley, Citation2001). Children in highly religious homes were more likely to be aware of prayer, while children from less religious families were more likely to accept diverse and at times ambiguous content of a prayer (Phelps & Woolley, Citation2001). Age-related findings on the concept of prayer have also varied, with some research not finding the fuller understanding until age 9 or 10 (Long et al., Citation1967), with more recent studies replicating children’s understanding of the concept of prayer in early childhood (Bamford & Lagattuta, Citation2010). Maternal religious coping, such as the use of prayer, has been positively linked with their child’s relationship with God (Goeke-Morey et al., Citation2014)

Omnipresent god concept

God concept refers to an individual’s beliefs about the traits of a divine figure, such as how the divine relates to, thinks, and feels about humans (Davis et al., Citation2013). Personified (anthropomorphic) and impersonal (abstract) constructs of God have been studied through different concepts. The personified God is represented through concepts such as merciful and authoritarian God concept, while abstract representations include omniness, and supreme God concept (Johnson et al., Citation2019; Wong McDonald & Gorsuch, Citation2004). This study will focus on omniness, specifically on the omnipresent and a limitless God concept. The doctrine of omnipresence is related to eternity, which is timeless with an absence of succession (Stump, Citation2013). God’s presence is not limited to the past, present, or future, so God can be in two places at the same time. In this way, limitless God concept was positively correlated to viewing God as personal, mystical and as a cosmic force, religious fundamentalism, religious commitment, God’s engagement, individualistic spirituality and a relationship with God (Johnson et al., Citation2019). Thus, omnipresence portrays God as limitless, infinite, boundless and powerful.

In early childhood, three phases have been noted related to the development of the God concept (Nyhof & Johnson, Citation2017). At ages 3–4, the reality bias reflects children’s thinking that everyone knows more than them, at ages 4–5 children tend toward anthropomorphic associations in which the fallibility of humans applies to God, and at ages 5–7 children start to understand the extraordinary mental capacities of God. Regardless of their religious background, children aged 4 can distinguish God’s abilities from other agents, with this ability increasing with age (Nyhof & Johnson, Citation2017). Further distinguishing within early childhood, children aged 5 understand more about the supernatural powers of God than 3-year-olds (Barrett et al., Citation2001; Kiessling & Perner, Citation2014; Lane et al., Citation2010). Other tasks used in middle childhood, such as drawing God (Harms, Citation1944) or the house of God (Pnevmatikos, Citation2002), show children moving from a concrete (e.g., God as a human to God as part human living in heaven) to an abstract concept (e.g., God as a spirit). However, drawing studies in early childhood suggest that there is no variability across this age group (Konyushkova et al., Citation2016), noting children are in this “fairy-tale” stage (Harms, Citation1944). Thus, given cognitive development related to the development of religious abstract concepts (Elkind, Citation1970; Goldman, Citation1965), we will use established scales related to the omnipresent God concept.

In addition to examining the association among parents and children for these three dimensions of religiosity, we will also consider four possible constructs that might moderate this association, in other words, transmission enhancers (for a comprehensive review on religious transmission, see Chamratrithirong et al., Citation2013; Milevsky et al., Citation2008; Stearns & McKinney, Citation2019b).

Transmission enhancers

Extending previous research, this study examines potential “transmission enhancers,” which may strengthen the influence of parental religiosity on children’s religiosity in early childhood. More specifically, this association may be enhanced as children age (H2), when parents view religiosity as an end in itself (H3), through active parental-child involvement in religious activities promoting autonomy (H4), and children exposed to religious beliefs through credibility-enhancing displays (H5). We review the existing evidence for each of these potential transmission enhancers.

Child age

Intergenerational transmission of beliefs may be strongest in early childhood when parents have a monopoly over the child’s beliefs (Beit-Hallahmi & Argyle, Citation1997), with the religious influence of parents decreasing in adolescence (Day, Citation2022; Glass et al., Citation1986). In the early years, parents are typically the central authority figure in the child’s life; children may identify with them, including around religion. Age 3 to 6 is also characterized by significant cognitive and social shifts; for instance, children become aware of social categories and group-based distinctions (e.g. Hailey & Olson, Citation2013; Killen et al., Citation2018). Additionally, significant cognitive changes are associated with the development of the Theory of Mind, which is linked to moral reasoning (Baird & Astington, Citation2004), as well as to the comprehension of supernatural attributes of God (Knight et al., Citation2004), and the understanding of God’s mind (Heiphetz et al., Citation2016). We predict that age will be a transmission enhancer in early childhood (H2); in other words, there will be a stronger association of parental to children’s religiosity among children aged 6 compared to those aged 3.

Internalized parental religious motivation

Internalized motivation is linked to greater religiosity for an individual and across family members. For example, for adolescents, higher internalized religious regulation was positively correlated with religious importance and religious identity, while lower religious regulation was not (Hardy et al., Citation2022). Moreover, parents who have internalized religious motivation support their children in developing autonomy and demonstrating religious values as their way of life (Brambilla et al., Citation2015). This suggests that internalized parental religious motivation has a role in the association between parental and children’s religiosity. Given that intrinsic motivation is particularly important in the early years (Deci & Ryan, Citation2000), we expect internalized parental religious motivation to moderate the transmission from parental to children’s religiosity (H3).

Active parental-child involvement

Religion is not only enacted on children (e.g., baptism of infants in Christianity, Mahoney et al., Citation2008), but also children may transform parental input and become active agents in religious transmission (Lawrence & Valsiner, Citation1993). For example, parental religious behaviors predict religiosity in children aged 10–12; this link was stronger in families that engaged in dyadic discussions as opposed to unidirectional discussions about religion (Flor & Knapp, Citation2001). This finding suggests religious autonomy and active involvement may be key to children’s religiosity. In the early years, children may be given the choice to pray before a meal or bedtime, or to attend religious activities. Accordingly, we expect that active parental-child involvement in their religion will strengthen religious transmission (H4).

Credibility-enhancing displays

How parents verbalize and model religious beliefs has implications for children’s religiosity. Children attend to credibility-enhancing displays by their parents such as watching them pray, attending church, and fasting (Henrich, Citation2009). The more costly the credibility-enhancing display is to the believer, the more commitment to that belief is shown. So, the greater the cost to the parent perceived by the child, the greater the influence on the learner. Credibility-enhancing displays involving action are better predictors of religiosity than verbalizations, emphasizing the importance of religious behaviors (Lanman & Buhrmester, Citation2016). For example, children are more likely to imitate parents who pray, than children whose parents tell them about the importance of prayer. Transmission is enhanced if parents set an example through living their religion (Kelley et al., Citation2021). Thus, we expect that credibility-enhancing displays will enhance religious transmission (H5).

Current study

This study contributes to literature in four ways. First, it focuses on the association between parental and children’s religiosity in the early years. Second, multiple reporters (i.e., parent and children; see Spilman et al., Citation2013) will report on their own religiosity, increasing validity (e.g., Crosby III & Smith, Citation2015; Kim et al., Citation2009). Third, the current study works with children directly; that is, it is not a retrospective study of the influence of parental factors on children’s religiosity (e.g., Hardy et al., Citation2011; Pearce & Thornton, Citation2007; Schwartz, Citation2006). Fourth, it examines potential enhancers of religious transmission with the family. We formulated the following hypotheses: Parental religiosity will be positively associated with child religiosity (H1), and this link will be strengthened for older children (H2), parents with higher internalized religious motivation (H3), in families with more active parent-child involvement (H4), and when there are greater parental credibility-enhancing displays (H5).

Given that various studies have found different levels of religious transmission between mother’s and father’s religiosity (Dickie et al., Citation2006; Reinert & Edwards, Citation2009; Stearns & McKinney, Citation2019b), we controlled for parental gender. We also controlled for demographic variables of parental socio-economic status, parental educational level, nationality, and developmental variables of child language/communication development and theory of mind (TOM). Data collection was completed by April 2023. The findings of this study have implications for understanding development of religiosity in early childhood.

Method

The present study examined the association between parental and children’s religiosity, moderated by child age, internalized parental religious motivation, active parental-child involvement, and parental credibility-enhancing displays in children aged 3–6. In a correlational design, parents answered questions about the three dimensions of religiosity (religious social identity, prayer, and God concept), transmission enhancers (internalized parental religious motivation, active parental-child involvement, and credibility-enhancing displays), as well as covariates (demographics, and child’s language/communication skills). Children participated in tasks to assess their developing religious social identity, prayer, and God concept, as well as a covariate of TOM.

The social context

Catholicism is the majority religious background in Malta, a small island in the Mediterranean of 316 km2 (Venice is 414.6 km2, Boston is 232.1 km2). According to the constitution of Malta (Laws of Malta, Citation2016), Catholicism is taught in state (i.e., public) schools. Among Malta’s 365 Catholic churches, religious attendance is rapidly declining (Archdiocese of Malta, Citation2018). Cultural changes, such as the introduction of divorce (2011), the legalization of same-sex marriage (2017), and the current planning for abortion (2023), overlap with increasing immigration (Giordmaina & Zammit, Citation2019). Despite these changes, Malta is a homogeneous country with 82.6% of Maltese people identifying as Catholic (National Statistics Office (NSO) Malta, Citation2023), that is, the majority religion.

Participants

Participants were recruited through state schools.Footnote1 Although compulsory education in Malta starts at age 5, over 90% of children ages 3–5 attend kindergarten in state schools, religious schools, and private schools (EUROSTAT, Citation2021). Classes have a maximum of 15 students at age 3, 20 students at age 4, and 25 students at 5 years and over (Malta Ministry for Education and Employment, Citation2013). In each school, there are two to seven classes for each age group.

Inclusion criteria for the analysis was between age 3 to 6 from the majority religion. That is, children from any background were allowed to participate, but only the data from the majority Catholic sample was included in the proposed analysis. Exclusion criteria included a communication score on the CDC measure of < 1.5 (2 SD below the mean) and confirmed by not responding to open-ended questions. Finally, anticipating a response rate of 30% of parental consent and a child assent of 90%, we approached 6 schools with 1,130 eligible families and received 313 parental consent forms, stopping when the proposed sample size was reached (see power analysis below). Of these, 10 parents did not answer the questionnaire, and 32 children had missing data (refer to for reasons of missing child data). Moreover, based on the exclusion criteria, 22 non-Catholic participants, 1 participant with missing data for religious affiliation, 9 children with a mean communication score less than 1.5, 1 child with missing communication scores, and 3 children aged less than 3 were excluded from the final sample of 235 dyads. This was very close to the proposed sample size obtained from the power analysis (i.e., n = 231).

Table 1. Reason for missing child data.

Power analysis

Power analysis was carried out for each moderator with varying effect sizes using G*power version 3.1.9.7 (Faul et al., Citation2009) in a fixed effects ANCOVA with main effects and interactions, an α = .05, 7 covariates, and power = .90. Relevant to the direct effect, a previous meta-analysis of 30 studies found a large effect size of .53 (ɀ = .53, r = .49, p < .001) between parent and child religiosity in middle childhood, adolescence, and emerging adulthood (Stearns & McKinney, Citation2019a). Thus, the final sample size of 231 parent-child dyads was estimated for d = .25 (medium effect size). This sample is also adequate to detect weak moderator effects (Champoux & Peters, Citation1987), represents 3.4% of the total population of children in kindergarten state primary schools (N = 6,855) in the country of Malta (National Statistics Office (NSO) Malta, Citation2021). This was an ambitious sample size for this age group in Malta (e.g., 175 children in Attard & Cordina, Citation1997, p. 105 children in; Mizzi Harber & Grima, Citation1999).

Supporting this, additional power analyses were conducted for the four moderators. First, a sample size of 58 dyads for age as a moderator was calculated based on an interaction between age and marital adjustment. For example, age moderated the link from marital adjustment to child externalizing behaviors (B = .52, p < .05; (Mahoney et al., Citation1997). Second, a sample size of 93 dyads for internalized religious motivation was estimated using effect size of .40, based on correlations with public religious involvement (r = .39 [CI .33, .46], p < .001), private religious involvement (r = .50 [CI .43, 57], p < .001) and religious identity (r = 63 [.56, .69], p < .001 (Hardy et al., Citation2022).; Third, a sample size of 54 dyads was calculated based on a medium effect size (r = .54, p < .0001 (Flor & Knapp, Citation2001); to religious importance when children were actively involved. Finally, a sample size of 173 dyads for credibility-enhancing displays was estimated based on the link to religiosity in adulthood (r = .29 to .59, p < .01) (Łowicki & Zajenkowski, Citation2019).

Procedure

The study was approved by UCD Ethics committee (Research Ethics Reference Number: HS-22-38-Zammit-Taylor) and Malta Directorate for Research, Lifelong Learning and Employability (Reference: R09–22 1256). Permission from the school principals and parental informed consent was gained prior to data collection. Children also provided assent throughout data collection. Each school was given €150 book vouchers, parents were given a €5 book voucher, and child participants were given a certificate of participation and stickers as a token of appreciation. Teachers who collected 50% response rate or more from their class were given a €20 voucher. Deidentified data for this paper is shared through Open Science Framework.

Translation and back-translation procedures were performed for all the measures by different bilingual scholars to ensure the precise Maltese translation of the original meaning and cultural appropriateness of the measures was retained (Son, Citation2018). Translations were revised to reflect child-friendly language in their respective languages. The first author piloted the child protocol with six children to refine timing and instructions. One of the pilots was recorded, with parental permission, and used for training purposes with the research assistants.

Through the class teachers, parents of the first three schools were given a participation information sheet, consent form and QR code for the online questionnaire to complete at home. Parents could request a printed copy of the questionnaire. Given the low response rate in these schools (mean response rate = 20%), the printed questionnaire was provided to parents in the other three schools providing a final response rate of 25.3%. Consent forms were returned via the child’s teacher within two weeks. The questionnaire consisted of demographic data for the child and family, the religious internalization scale, the active parental-child involvement scale, the credibility-enhanced display exposure scale, and the communication subscale of the CDC checklists and milestones. The questionnaire took approximately 10–15 minutes to complete. Data collected in hard copies were stored in a locked cabinet in a locked office. The original hard copies were destroyed once deidentified data was entered for analysis.

The researchers worked one-to-one with the children who had parental consent at school in a designated private room or quiet area of the school, adhering to public health guidelines. The child tasks took 10–15 minutes and were conducted in the child’s preferred language (Maltese, English or Italian) indicated in the parental consent form. Tasks were programmed in Microsoft Teams and collected using a password-protected tablet. Deidentified data files were stored on Novell Drive (NetStorge) provided by UCD accessed through Multi-Factor Authentication to secure and protect research data.

Materials and measures

Parental religiosity measures

Parental religiosity was an average of the z scores for the following three dimensions: religious social identity, prayer, and God concept.

Parental religious social identity

Participants reported their religious affiliation then rated 5 items on 5-point scale from 1 (rarely) to 5 (very often) with a higher score showing higher religious social identity (Brown et al., Citation1986; Merrilees et al., Citation2013). For example, “Would you say you are a person who identifies with your religious (e.g., Catholic, Muslim, etc.) community?” Internal consistency of the religious social identity items was high in the current sample. (α = .93).

Parental prayer

The validated brief measure of Perceived Divine Engagement and Disengagement in response to prayer was used (Exline et al., Citation2021). Participants were asked “How often do you pray?” Parents could respond either: never (0), once in a while (1) or often (2) to the question, with a higher score showing higher prayer engagement. This was followed by the prompt: “When you pray, how often do you perceive or experience the following?” Four items from the divine engagement subscale were listed (e.g., “received guidance from God regardless of the matter you are praying for.”) and rated as never (1), rarely (2), sometimes (3), often (4), and always (5), with a higher score indicating more perceived divine engagement. Internal consistency for this sample was also high (α = .90).

Parental god concept

The subscale of a limitless God from the LAMBI measure of omnipresent God representations was used (Johnson et al., Citation2019). Parents were asked to rate how much a list of 5 words (limitless, vast, immense, infinite, boundless) describes God based on their own experience and beliefs, as opposed to theologically correct beliefs. Parents rated the words on a 7-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree); higher scores indicate greater sense of limitless God. Internal consistency for this scale was also high (α = .95).

Child religiosity measures

Children’s religiosity was an average of the z scores for the following three concepts: religious social identity, prayer, and God concept.

Children’s religious social identity

Symbols depicting the Catholic religion, as the majority religion, and symbols of other religions were used to measure children’s religious social identity (adapted from Taylor et al., Citation2020). This task was engaging, yet simple enough for children at this age given their cognitive, linguistic, and physical (fine motor) abilities. A total of 10 pairs of images representing different religious symbols, traditions, celebrations, and clothing were presented. Two symbols, one from the majority/one from another religion (e.g., a priest and an Imam), were presented at a time on a tablet through Microsoft Teams. The child was asked to point to the picture, which is Catholic, which the researcher read out loud. If the symbol is categorized with the correct label, a score 1 is given (e.g., a Catholic Church is chosen as Catholic.), otherwise a score 0 is given. The higher scores indicate that the children have a greater awareness of ingroup religious symbols and thus a higher religious social identity.

Children’s prayer

This measure was an adaptation of Long et al. (Citation1967) and Phelps and Woolley’s (Citation2001) interview to explore the development of the prayer concept. Given the linguistic abilities of children in this age range, this was a structured interview. Children were shown a picture of a family praying in majority religion (i.e., Catholic) (picture 1). Children were asked to describe what is happening in the picture. If the child showed no understanding of what is happening in the picture, the researcher told the child that the family is praying and a score of 0 was given. If the answer was related to church or God, or a related symbol, e.g., putting their hands together, a score of 1 was given. If the child showed awareness of what a prayer is, a score of 2 was given. This was followed by a short, structured interview of 6 entity questions of prayer, 3 prayer request questions, 3 timing of prayer questions, a question about God’s engagement, and 2 questions about outgroup prayer (Refer to supplementary material for scoring details). A higher total mean score indicated a higher prayer concept.

Children’s god concept

The God concept was measured in three items through knowledge of the physical attributes of the omnipresence of God. The first item was adapted from Kiessling and Perner (Citation2014) where the children were asked an open-ended question about knowledge of God. The second and third items of this task were adapted from Nyhof and Johnson (Citation2017). These were closed-end questions measuring the child’s knowledge that God can get in a closed box without opening it (item 2) and be in more than one place at the same time (item 3). A higher total score (range 0 to 3) reflected greater knowledge about God’s supernatural ability of omnipresence (Refer to supplementary material for scoring details).

Transmission enhancers

Transmission Enhancers were measured through the child’s age, parental internalized religious motivation, active parental-child involvement, and credibility-enhancing displays, which were modeled as moderators.

Parental internalized religious motivation

The Religious Internalization Scale was adapted from Ryan et al. (Citation1993) and Neyrinck et al. (Citation2006). Parents were asked to write a religious activity they perceive as most helpful in expressing their religious belief attitude. This was followed by 16 items assessing parental belief regulations (integrated, identified, introjected and external) on a 4-point scale from 1 (not true at all) to 4 (very true), so that higher scores indicated more internalized parental religious motivation. An example of an item showing high internalization is “because it connects well with what I want in life” whilst an item low in internalization is “because others put me under pressure to do so.” Items 9 to 16 were reversely scored. This produced an adequate internal consistency for the scale (α = .71). Internal consistency showed no improvement if any item was deleted, so all items were retained.

Active parental-child involvement

Seven items (four of which constructed from (Crosby III & Smith, Citation2015) measured the extent to which parents actively involve their children in religious practices. Adaptations were inclusive of different religions, for example, “Bible” was adapted to “holy scripture.” Adaptations were also carried out to allow for involvement through giving children a choice to be assessed e.g., “I pray with my child before bedtime” was changed to “My child decides if they want to pray before bedtime.” Parents were asked to respond on a scale from 1 (never) to 4 (very often), so that the higher the score, the higher the active religious engagement. Parents were asked to tick “not relevant” if the practice was not carried out. Items marked as “not relevant” were recoded as missing data. This scale had an adequate internal consistency (α = .73) when items 1 and 4 were removed. Item 1 was removed since more than half of the parents (n = 129, 55%) reported that item 1 was not relevant, showing that the Bible was not read at home. From those who rated this item, the mean score was the lowest of all the items in the scale (μ = 2.05, SD = 1.04, n = 106). Item 4, “I enjoy telling my child about God/the Divine.” did not correlate with the rest of the items on the scale, so it also was omitted from the final scale.

Credibility-enhancing displays

This was measured through an adaptation of the Credibility Enhanced Display Exposure scale (Lanman & Buhrmester, Citation2016). This scale was designed to be used by children retrospectively, to rate their perception of their primary caregiver/s’ religious behaviors. The seven items of this scale were adapted for parents to rate their own behavior, e.g. “To what extent did your caregiver(s) engage in religious volunteer or charity work” was adapted to: “How often do you engage in religious voluntary or charity work?” An 8th item adapted from the Duke University Religion Index (DUREL; Koenig & Büssing, Citation2010) measured how often parents spend time in private religious activities. All items were scored on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (always). Scores were averaged so that higher scores indicated more self-reported credibility-enhancing displays. This scale produced an adequate internal consistency (α = .80) which would not have improved if any items were dropped, so all items were retained.

Covariates

Parental gender, socioeconomic status, parental education level, and nationality, were used as control variables. Given children’s age, two developmental control variables were used: child communication and TOM (see supplementary material for a description for the covariates measures). Children included in the analysis had a mean communication score of 1.5 or better.

Proposed hypothesis testing

In the initial phase of our analysis, we computed the total score for each of the parental and children’s religiosity scales, that is, measures for religious social identity, prayer, and God concept. We employed the maximum likelihood estimation method, assuming that the missing data occurred at random, and applied a criterion of 80% or more of non-missing data for inclusion. Subsequently, we calculated Z-scores for each of the parental and children’s religiosity measures and standardized the mean scores of these three measures. This standardization process enabled us to place both predictor (parental religiosity) and outcome (children’s religiosity) variables on a common scale. Next, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted on the moderators, that is, parental religious motivation, active parental-child involvement, and credibility-enhancing displays so that each moderation scale could be calculated. Finally, we mean-centered all moderators and interaction terms in preparation for analysis. To examine these interactions of transmission enhancers in the association of parental to children’s religiosity, we employed a multivariate regression model with bootstrapping (using 1,000 bootstrap samples), to decrease the potential threat of multicollinearity. The results are reported with 95% confidence. The predictor, moderators, and the computed interactions were entered into the model as independent variables, together with the covariates (refer to for conceptual model).

Figure 1. Conceptual model of the association between parental religiosity and children’s religiosity in early childhood moderated by age, internalized parental religious motivation, active parental-child involvement, and credibility-enhancing displays. (covariates not depicted for readability; (parental variables): parental gender, socioeconomic status, parental education, nationality; (child developmental variables): communication skills, theory of mind task).

Results

Preliminary analysis

An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted in SPSS (version 27) on three scales, that is, the 16-item Parental Internalized Religious Motivation scale (RM; Neyrinck et al., Citation2006; Ryan et al., Citation1993), the 7-item Active Parental-Child Involvement scale (ACI; adapted from Crosby III & Smith, Citation2015), and the 7-item Credibility-Enhancing Display scale (CRED; Koenig & Büssing, Citation2010; Lanman & Buhrmester, Citation2016), among parents of 3–6-year-olds in Malta. EFA utilized Principal Component Analysis with Oblimin rotation. For the RM scale, Eigen values with a suitable KMO (<.8) and a significant Bartlett’s test supported a three-factor structure explaining 64.3% of the variance. Eight items loaded on Factor 1, explaining 36.8% of the variance (eigenvalue = 5.9), six items on Factor 2 explaining 17.4% (eigenvalue = 2.8), and the last two items on Factor 3 explaining 10.1% (eigenvalue = 1.6), aligning with findings in Neyrinck et al.’s research (Neyrinck et al., Citation2006). Reliability analysis and Pearson correlations confirmed that no items need to be omitted. For the ACI scale, Eigen values, the Scree plot, a suitable KMO value (<.7), and a significant Bartlett’s test revealed a two-factor structure. The two-factor solution, explaining 65.68% of the variance, included three original items and item 5 on Factor 1, while item 4 and the last two items loaded on Factor 2 (all loadings > .7). A subsequent analysis, excluding items 1 and 4, increased explained variance to 71% but slightly reduced internal consistency (α = .734). For the CRED scale, Eigen values, the Scree plot, a suitable KMO value (<.7), and a significant Bartlett’s test indicated a two-factor structure. Factor 1 accounted for 46% of the variance (eigenvalue = 3.21), and Factor 2 accounted for 20% of the variance (eigenvalue = 1.37) (Williams et al., Citation2010). As this study does not differentiate between types of components resulting from the EFA, all the three scales were treated as continuous variables in the moderation model analysis.

presents the means, standard deviations, and ranges for all numerical study variables and controls. presents bivariate correlations of all numerical variables. Parents’ ages ranged from 21 to 51 years, with the majority being Maltese (94%, n = 221). Among the parents, 85.5% were mothers, and 86.4% were in an emotional relationship. Regarding education, 39.6% had a secondary or post-secondary education, while 35.8% had a diploma or degree. Additionally, 78.3% of parents were in employment, and 78% placed themselves between the 5th and 7th rung of the social ladder (10th rung was the highest rung, representing higher financial status). The sample was balanced by gender; with 51.9% (n = 122) of the children being girls. The average age of the children was 4 years ( = 4.15, SD = 0.97). Specifically, 30.6% were aged 3, 33.6% were aged 4, 26% were aged 5, and 9.8% were aged 6. Most of the children (94.9%) demonstrated the highest score for communication skills. However, only 31.1% succeeded in the theory of mind task, while 20.9% struggled with one of the two agents on this task, and 48.1% failed this task.

Table 2. The means (total mean), standard deviations, ranges for all numerical study variables and controls.

Table 3. Bivariate correlations and descriptive statistics of all study variables.

Parents were asked about their religious activities and participation. Results showed that 23% of parents reported never or almost never attending religious services or meetings, while 29.8% reported never or almost never engaging in private religious activities. A small minority (3.8%) stated that they never pray. Interestingly, only 76.6% of parents identified a religious activity helpful in expressing religious belief, whilst 20.4% did not consider any activity as helpful (not even prayer), and consequently they did not complete the items on the parental religious motivation scale. Among the reported religious activities, going to church was the most common (44.3%), followed by praying (11.1%), and attending Sunday mass (5.5%).

The child tasks assessed young children’s comprehension of religious concepts, such as prayer. When presented a picture of a family praying from the majority religion, only 43.4% of the children were able to correctly relate the picture with praying. Regarding their understanding of the meaning of prayer, 37.4% of the responses were related to prayer actions, such as making the sign of the cross, clasping their hands together, or demonstrating the ability to say a prayer. Some children (19.6%) could not connect prayer with God, while 9.4% linked prayer with expressions of gratitude or verbal requests. Only 2.1% perceived prayer was a conversation with God. This shows that most of the children in this sample lacked a well-developed understanding of the meaning of prayer, despite 72.8% of them claiming to know what prayer means.

Children’s religiosity was also assessed by examining their knowledge of God. Most of the children (81.7%) indicated that they knew who God/Jesus is. However, when asked about God’s location, 38.7% either did not know or were uncertain, while 21.7% believed God to be in the clouds, sky or “up there.” Additionally, 12.8% placed God in church, or in a familiar physical setting such as with his mother, at home or in the classroom (11.5%). Notably, during the Catholic religious period of lent, some children (6%) mentioned that Jesus lives on the cross and provided vivid descriptions of his suffering. Few children conceptualized God in abstract locations, with 2.1% suggesting heaven, and 3.4% expressing beliefs of God being everywhere or residing within their hearts. Furthermore, when questioned about God’s omnipotence, 65.5% responded that God could be in two places simultaneously, but interestingly, they also claimed that both themselves (63.4%) and the researcher (61.7%) could likewise be in two places at once.

Hypothesis testing

Our first hypothesis predicted that parental religiosity would be positively associated with child religiosity (H1). Pearson correlation found no significant correlation between parental and children’s religiosity r(210) = .002, p = .98.

A multivariate regression was conducted to predict children’s religiosity based on parental religiosity and four moderators: child age, parental internalized religious motivation, active parental-child involvement, and credibility-enhancing displays. The hypothesis posited that these moderators would enhance the relationship between parents’ and children’s religiosity. The overall model was statistically not significant, F(6, 88) = 0.44, p < . 851), with an R2 of .309. This indicates that our predictors explain 31% of the variance in children’s religiosity levels, while 69% of the variance might be attributed to other factors not included in the model. However, contrary to our hypotheses, none of the interactions between parental religiosity and the moderators were statistically significant in predicting children’s religiosity. Child’s age was the only significant predictor of children’s religiosity ().

Table 4. Child’s age, parental internalized religious motivation, active parental-child involvement, parental credibility enhancing displays as moderators of the relationship between parental religiosity and child religiosity, and covariates.

Exploratory analysis

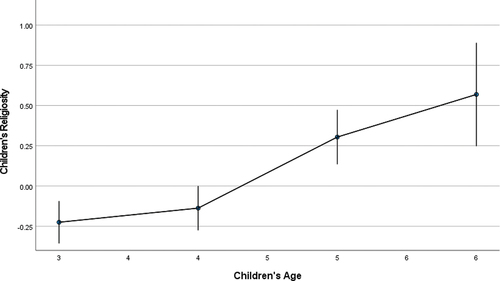

Since age was the only significant predictor in the model, further investigation focused on examining the relationship between children’s age and their religiosity. A one-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of the children’s age on their level of religiosity, F(3, 222) = 15.57, p < .001. Post Hoc Tests indicated no significant differences in religiosity between children aged 3 and 4, or between children aged 5 and 6. However, there was a significant difference in religiosity between children aged 3 and 4, in comparison to those age 5 and 6 (p < .001); in other words, older children reported higher religiosity compared to younger children ().

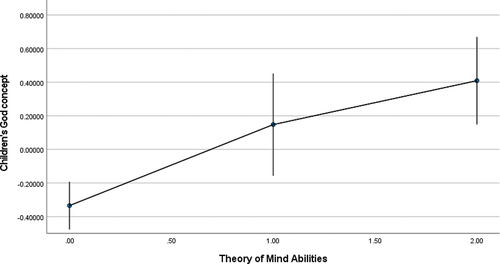

Due to the correlation between the Theory of Mind (TOM) task and children’s religiousness, a further analysis was conducted to explore their relationship. A one-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of the TOM task on children’s religiosity, F(2, 223) = 5.86, p = .003. Furthermore, a one-way MANOVA was performed to determine the relationship TOM to the various constructs that contribute to the children’s religiosity score, namely prayer, religious social identity, and God concept. Results showed a significant difference in the scores for the God concept based on the success of TOM task, F(2, 223) = 14.65, p < .001; Wilk’s lambda = 0.876, partial eta squared = 0.116. Post hoc analysis indicated that children who were successful on the TOM task (score of 2) exhibited significantly higher God concepts ().

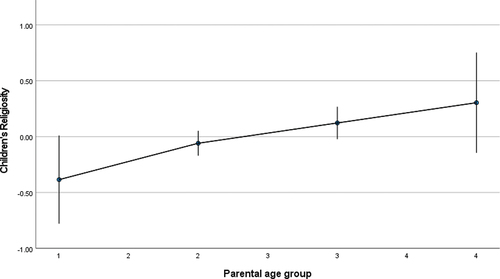

Since parental age was the only parental variable correlating with children’s religiosity, it was subjected to further investigation. A one-way ANOVA revealed a significant difference in children’s religiosity scores depending on parental age group (F(3, 221) = 3.97, p = .009) indicating that higher parental age groups were associated with higher levels of children’s religiosity. Children whose parents were below the age of 35 scored below the standardized mean of children’s religiosity, while children whose parents were aged 36 and over scored above the standardized mean of children’s religiosity. Moreover, children’s religiosity differed significantly between parents aged 21 to 26 and 27 to 35, compared to parents aged 36 to 41 and over 42. However, there was no significant difference between parents aged 36 to 41 and those over 42 ().

Discussion

This study contributes to the limited body of research on the transmission of religious belief and practice from parents to children during early childhood. Data was directly collected from both young children and their parents, focusing on enhancers of the association between parental and children’s religiosity. However, the initial hypothesis (H1) proposing a correlation between parental and children’s religiosity was not supported. Likewise, the moderating hypotheses related to children’s age (H2), parental internalized religious motivation (H3), active parental-child involvement (H4), and credibility-enhancing displays (H4) were not supported. Possible explanations and implications of these findings will be discussed in the context of early childhood, family factors, and the study’s design.

Early childhood

One possible explanation for the lack of significance in the association is that children within this age group may be too young to have fully developed religiosity. The average age of the children in the study was 4 years, with only a small percentage (9.8%) aged 6. Notably, in Malta, parents can choose to enroll their children in church schools at age 5, resulting in a lower population of children aged 5–6 in state primary schools compared to the earlier kindergarten classes (aged 3–5). Moreover, findings from bi-variate correlations of the different children’s religiosity scales indicate that only a few children understood the meaning of prayer, and most children did not grasp the concept of God’s omnipotence. Exploratory analysis revealed that children’s religiosity at ages 3 and 4 was significantly lower than that of children aged 5 and 6, suggesting less developed religiosity in younger children.

The lack of success on the Theory of Mind (TOM) task may also contribute to the lower levels of religiosity observed, as only a small percentage of children in this sample (31.1%, n = 73) were successful in the TOM task. The positive correlations between TOM and all child religiosity scales, along with the variance analysis, highlight the potential role of TOM in shaping children’s understanding of religious concepts during early childhood. For instance, some children provided remarkable reasons for why individuals cannot pray at any time, such as not praying in the library to be silent (implying that praying requires speaking aloud for God to hear) or fearing that Jesus might experience a headache or become sick due to prayer. However, a significant variance existed between TOM and children’s omnipotent God concept. During the child task, the researcher posed a question to the children about how they or the researcher could be in two rooms simultaneously. Despite their inability to explain it, the children consistently maintained the omnipotent response for all entities, including themselves, the researcher, and God.

An alternative interpretation suggests that young children are inclined toward naturalistic rather than supernatural explanations. This tendency is evident in their attribution of natural biological reasons over religious ones for unobservable phenomena. For example, in their reflections of the meaning of death, 7-year-olds are more likely to interpret it as a biological inevitability rather than a religious event, unlike 11-year-olds (Harris, Citation2018). This tendency is mirrored in the current study, wherein nearly half of the participants (47.8% = No, 2.6% = unsure) negated the possibility of obtaining sweets through prayer, citing potential dental harm as their rationale. Despite children in the current study being younger, children also favored biological consequences over divine means for acquiring sweets. This preference may be akin to observations from China, where children in our study receive mixed messages regarding dental hygiene and religious practices (Davoodi et al., Citation2020). However, for the Catholic children in Malta, who are also the majority group, the emphasis on dental care at home and school makes scientific rationale more attractive than belief in unobservable entities. These insights support the culturally nuanced nature of religious learning in children, suggesting that the participants in this study might be indeed too young for the religious transmission process to have fully happened.

Consistent with recent studies (Kiessling & Perner, Citation2014), children in this sample anthropomorphized God’s mind, possibly due to the “preparedness hypothesis,” suggesting innate abilities in children to represent God as superhuman (Barrett & Richert, Citation2003). This hypothesis is closely linked to the early stages of TOM development, as children appear to be born with the ability to comprehend God’s omnipotence (Barrett & Richert, Citation2003; Barrett et al., Citation2001). However, the current study also revealed that children attributed omnipresence not exclusively to divine entities but also to other agents, including themselves and the researcher. Just like the Maya children the Maltese children in our study may not have been accustomed to participating in such research endeavors and responding to questions of this nature (Knight et al., Citation2004). This observation finds reinforcement in the fact that some parents completed the questionnaire but expressed reservations about their children’s participation, deeming them too young for the study. These findings suggest that the children in this study occupy early stages of religious development, assimilating societal and religious norms regarding divine entities, yet not fully embracing the concept of omnipresence as an exclusively divine attribute. This underscores the pivotal role of cultural context in research studies of this nature.

Both prayer and omnipotence concepts require an understanding of God’s mind, which might explain the lower levels of religiosity observed in the sample. Conversely, children’s religious social identity did not impose the same cognitive demands, possibly accounting for the higher scores obtained in that aspect. This finding suggests that assessing children’s religious social identity may be a valuable tool for measuring religiosity in this age group. Complementing basic developmental processes, family factors were also considered.

Family factors

This study assessed dimensions of parental religiosity through religious social identity, prayer, and God concept, as well as family moderators such as internalized parental religious motivation, active parental-child involvement, and credibility-enhancing displays. All these parental factors demonstrated positive correlations with one another, except for the active parental-child involvement scale, supporting the construct validity of parental religiosity.

The unique characteristics of the sample, such as low parental religiosity, could account for some of the study’s outcomes. For instance, after exploratory analysis, item 1 was removed due to over half of the parents reporting that the Bible is not read at home. Additionally, a surprisingly low percentage of parents listed a religious activity that aided them in expressing their religiosity. These findings suggest low level of engagement in religious practices in a country with no religious conflict, which aligns with the reported decrease in religious attendance (Archdiocese of Malta, Citation2018). Recent research also indicates a declining belief in God in Malta, with percentages decreasing from 93.5% in 2021 to 88.5% in 2023 (Marmarà, Citation2023). Furthermore, an analysis of variance between children’s religiosity and parental age group suggests that younger parents (under 35 years) are associated with lower levels of children’s religiosity, consistent with research showing varying belief rates across age groups (Marmara, Citation2021). Further analysis into the mediating effect of parental age on the relationship between parental and children’s religiosity might shed light on nuances of this association.

In our analysis of family factors influencing children’s religious beliefs, a significant gap was the exploration of how parents may anthropomorphize God when communicating with their children, potentially shaping their children’s religious conceptions. Our study, while delving into parental beliefs, did not investigate the specific communication methods parents utilize to transmit religious concepts, such as portraying God with human-like qualities in telling their children, “say the prayer as God is listening.” Previous research shows that people tend to attribute human emotional states to God (Gray & Wegner, Citation2010; Haslam et al., Citation2008), and parents play a role in fostering anthropomorphism in their children (Heiphetz et al., Citation2016). Recent research involving parent-child discourse observation demonstrates that parental religiosity predicts the way religious entities are presented to children, and these beliefs subsequently influence children’s religious judgments (McLoughlin et al., Citation2021). The nuance of whether such depictions by parents in their children’s formative years influence their understanding of God’s cognitive abilities was not addressed, leaving a potential explanatory factor for the lack of association found in our results, questioning the universality of the preparedness hypothesis.

Additionally, cultural context is pivotal in interpreting our findings. For instance, in secular countries like the U.S. and China, religious parents often use uncertainty cues when discussing unobservable religious concepts (e.g., God) compared to science concepts (e.g., germs), and show limited belief variation when interacting with their 5-to-11-year-olds (McLoughlin et al., Citation2021, Citation2023). This cultural complexity in religious belief transmission aligns with Richert et al. (Citation2022) argument that cognitive development is intricately linked to culture, emphasizing the inseparable connection between cognition and enculturation. These cultural insights underscore the need for a more comprehensive examination in our study design to fully elucidate the nonsignificant results regarding parental transmission of religious beliefs.

Study design

One potential explanation for the lack of significance in the interactions could be the study design. Research indicates that sample size and moderator variance structure can impact the ability to detect moderation effects in partially nested designs (Cox & Kelcey, Citation2023). In this study, participants belonged to different groups based on factors like religiosity levels, children’s age, active parental-child involvement, and credibility-enhancing displays. The partially nested design with individuals in different groups might have affected the power analysis’ ability to detect moderation effects, especially given the relatively low number of children (n = 23) in the higher end of the age group, potentially reducing the power of age as a moderator in the analysis.

The means of data collection might also account for the lack of association. Since the children in the study were in their early years, parental religiosity data was collected through parents’ self-reports. This involved adapting scales like credibility-enhancing displays and active parental-child involvement to suit parental reporting. Despite adequate internal reliability of these measures, self-reporting bias could have influenced the results.

It is worth noting that previous research on the association between parental and children’s religiosity primarily focused on older children (see metanalysis: Stearns & McKinney, Citation2019b), with few studies involving children under the age of 6, and only one study with age 6 as the youngest group (Kim et al., Citation2009). The scarcity of published studies in early childhood highlights the significance of this preregistered study’s findings, which might contribute to future research in this area (van ’t Veer & Giner-Sorolla, Citation2016).

Conclusions

This study found no significant relationship between parental and children’s religiosity, as well as no significant transmission-enhancing effects for any of the moderators in early childhood. These results diverge from previous associations observed in later childhood. This discrepancy might be attributed to the study design or the possibility that children in this age group are too young to manifest religiosity as measured with the current constructs.

To better understand how religiosity develops during early childhood, it may be beneficial to consider parental-child observation rather than relying solely on parental reports, and the development of scales such as those specifically tailored to early childhood. Longitudinal studies would also be valuable in providing insights into the developmental trajectory of religious transmission. Furthermore, promoting pre-registered reviewed studies, such as the current approach, is crucial in advancing this line of research and avoiding publication bias by sharing null findings. In summary, based on reports from multiple sources and including children ages 3–6, there was no significant association between parental and children’s religiosity.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (64.4 KB)Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the schools, teachers, parents, and students for their participation. Prof. Eilis Hennessy (University College Dublin) and Dr. Islam Borinca (University of Groningen) made valuable contributions to statistical analysis and discussions. We also appreciate Dr. Matthew Muscat Inglott’s (Malta College of Science and Technology) input on statistical analysis. Colleagues at GrouPSI provided insightful feedback on earlier study versions. This research received support from the John Templeton Foundation for the Open Science of Religion Project. Isabelle Zammit’s PhD thesis was financially supported by the Malta Tertiary Education Scholarship Scheme, with sabbatical leave granted by the Malta College of Arts, Science, and Technology to facilitate research completion.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/10508619.2024.2331891

Data availability statement

Data that support the findings of this study will be openly available at https://osf.io/w7h3f/?view_only=f06bd9d2ab6b4617893d3e2f0a971937.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Children aged 3–5 in Malta attend non-compulsory kindergarten inside a school.

References

- Archdiocese of Malta. (2018). Around 40% attend Sunday mass regularly – archdiocese of Malta. https://church.mt/around-40-attend-sunday-mass-regularly/

- Attard, N., & Cordina, M. (1997). The performance of gozitan kindergarten and year 1 pupils on three ability tests. University of Malta.

- Baird, J. A., & Astington, J. W. (2004). The role of mental state understanding in the development of moral cognition and moral action. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2004(103), 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/cd.96

- Bamford, C., & Lagattuta, K. H. (2010). A new look at children’s understanding of mind and emotion: The case of prayer. Developmental Psychology, 46(1), 78–92. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016694

- Barrett, J. L., & Richert, R. A. (2003). Anthropomorphism or preparedness? Exploring children’s god concepts. Review of Religious Research, 44(3), 300–312. https://doi.org/10.2307/3512389

- Barrett, J. L., Richert, R. A., & Driesenga, A. (2001). God’s beliefs versus mother’s: The development of nonhuman agent concepts. Child Development, 72(1), 50–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00265

- Beelmann, A., & Heinemann, K. S. (2014). Preventing prejudice and improving intergroup attitudes: A meta-analysis of child and adolescent training programs. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 35(6), 10–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2013.11.002

- Beit-Hallahmi, B., & Argyle, M. (1997). The psychology of religious behaviour, belief and experience. Routledge.

- Boyatzis, C. J. (2005). Religious and spiritual development in childhood. In R. F. Paloutzian & C. L. Park (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of religion and spirituality (pp. 123–143). The Guilford Press.

- Brambilla, M., Assor, A., Manzi, C., & Regalia, C. (2015). Autonomous versus controlled religiosity: Family and group antecedents. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 25(3), 193–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508619.2014.888902

- Brown, R., Condor, S., Mathews, A., Wade, G., & Williams, J. (1986). Explaining intergroup differentiation in an industrial organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 59(4), 273–286. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1986.tb00230.x

- Champoux, J. E., & Peters, W. S. (1987). Form, effect size and power in moderated regression analysis. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 60, 243–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1987.tb00257.x

- Chamratrithirong, A., Miller, B. A., Byrnes, H. F., Rhucharoenpornpanich, O., Cupp, P. K., Rosati, M. J., Fongkaew, W., Atwood, K. A., & Todd, M. (2013). Intergenerational transmission of religious beliefs and practices and the reduction of adolescent delinquency in urban Thailand. Journal of Adolescence, 36(1), 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ADOLESCENCE.2012.09.011

- Connolly, P., Kelly, B., & Smith, A. (2009). Ethnic habitus and young children: A case study of Northern Ireland. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 17(2), 217–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/13502930902951460

- Connolly, P., Smith, A., & Kelly, B. (2002). Too young to notice? The cultural and political awareness of 3-6 year olds in Northern Ireland. www.community-relations.org.uk

- Cox, K., & Kelcey, B. (2023). Experimental methodology: Statistical power for detecting moderation in partially nested designs. American Journal of Evaluation, 44(1), 133–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214020977692

- Crosby III, R. G., & Smith, E. I. (2015). Church support as a predictor of children’s spirituality and prosocial behavior. Article in Journal of Psychology and Theology, 43(4), 243–254. https://doi.org/10.1177/009164711504300402

- Davis, E. B., Moriarty, G. L., & Mauch, J. C. (2013). God images and god concepts: Definitions, development, and dynamics. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 5(1), 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029289

- Davoodi, T., Cui, Y. K., Clegg, J. M., Yan, F. E., Payir, A., Harris, P. L., & Corriveau, K. H. (2020). Epistemic justifications for belief in the unobservable: The impact of minority status. Cognition, 200(March), 104273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2020.104273

- Day, A. (2022). Age, gender and de-churchisation. In C. Starkeu & E. Tomalin (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Religion, gender and society: (1st ed., pp. 249–260). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429466953-19

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

- Dickie, J. R., Ajega, L. V., Kobylak, J. R., & Nixon, K. M. (2006). Mother, father, and self: Sources of young adults’ god concepts. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 45(1), 57–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1468-5906.2006.00005.X

- Elkind, D. (1970). The origins of religion in the child. Review of Religious Research, 12(1), 35–42. https://doi.org/10.2307/3510932

- EUROSTAT. (2021). Pupils in early childhood and primary education by education level and age - as % of corresponding age population.

- Exline, J. J., Wilt, J. A., Harriott, V. A., Pargament, K. I., & Hall, T. W. (2021). Is god listening to my prayers? Initial validation of a brief measure of perceived divine engagement and disengagement in response to prayer. Religions, 12(80), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12020080

- Faas, D., Barmody, M., & Sokolowska, B. (2016). Religious diversity in primary schools: Reflections from the Republic of Ireland. British Journal of Religious Education, 38(1), 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/01416200.2015.1025700

- Fancourt, N. (2021). The educational competence of the European court of human rights: Judicial pedagogies of religious symbols in classrooms. Oxford Review of Education, 48(2), 131–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2021.1933406

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(1), 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

- Flor, D. L., & Knapp, N. F. (2001). Transmission and transaction: Predicting adolescents’ internalization of parental religious values. Journal of Family Psychology, 15(4), 627–645. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.15.4.627

- Giordmaina, J., & Zammit, L. (2019). Shaping the identity of the new Maltese through ethics education in Maltese schools. Education Sciences, 9(4), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9040253

- Glass, J., Bengston, V. L., & Dunham, C. C. (1986). Attitude Similarity in Three-Generation Families: Socialization, Status Inheritance, or Reciprocal Influence? American Sociological Review, 51(5), 685–698. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095493

- Goeke-Morey, M. C., Cairns, E., Taylor, L. K., Merrilees, C. E., Shirlow, P., & Cummings, E. M. (2015). Predictors of strength of in-group identity in Northern Ireland: Impact of past sectarian conflict, relative deprivation, and church attendance. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 25(4), 283–295. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2211

- Goeke-Morey, M. C., Taylor, L. K., Merrilees, C. E., Shirlow, P., & Cummings, E. M. (2014). Adolescents’ relationship with god and internalizing adjustment over time: The moderating role of maternal religious coping. Journal of Family Psychology, 28(6), 749–758. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037170

- Goldman, R. (1965). Readiness for religion: A basis for developmental religious education (pp. 5). Routledge.

- Gorsuch, R. L., & McPherson, S. E. (1989). Intrinsic/Extrinsic measurement: I/E-revised and single-item scales. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 28(3), 348–354. https://doi.org/10.2307/1386745

- Gray, K., & Wegner, D. M. (2010). Blaming god for our pain: Human suffering and the divine mind. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14(1), 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868309350299

- Greenfield, E. A., & Marks, N. F. (2007). Religious social Identity as an explanatory factor for associations between more frequent formal religious participation and psychological well-being. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 17(3), 245–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508610701402309

- Hailey, S. E., & Olson, K. R. (2013). A Social Psychologist’s Guide to the development of racial attitudes. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 7(7), 457–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/SPC3.12038

- Hardy, S. A., Nelson, J. M., Fradesen, S. B., Cazzell, A. R., & Goodman, M. A. (2022). Adolescent religious motivation: A self-determination theory approach. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 32(1), 16–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508619.2020.1844968

- Hardy, S. A., White, J., Zhang, J., & Ruchty, Z. (2011). Parenting and the socialization of religiousness and spirituality. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 3(3), 217–230. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021600

- Harms, E. (1944). The development of religious experience in children. American Journal of Sociology, 50(2), 112–122. https://doi.org/10.1086/219518

- Harris, P. L. (2018). Children’s understanding of death: From biology to religion. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 373(1754), 20170266. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2017.0266

- Harris, P. L., & Koenig, M. A. (2006). Trust in testimony: How children learn about science and religion. Child Development, 77(3), 505–524. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00886.x

- Haslam, N., Kashima, Y., Loughnan, S., Shi, J., & Suitner, C. (2008). Subhuman, inhuman, and superhuman: Contrasting humans with nonhumans in three cultures. Social Cognition, 26(2), 248–258. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2008.26.2.248

- Heiphetz, L., Lane, J. D., Waytz, A., & Young, L. L. (2016). How children and adults represent God’s mind. Cognitive Science, 40(1), 121–144. https://doi.org/10.1111/COGS.12232

- Henrich, J. (2009). The evolution of costly displays, cooperation and religion: Credibility enhancing displays and their implications for cultural evolution. Evolution and Human Behavior, 30(4), 244–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2009.03.005

- Hogg, M. A., & Abrams, D. (1998). Social identifications: A social psychology of intergroup relations and group processes. Contemporary Sociology, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.2307/2073535.

- Johnson, K. A., Okun, M. A., Cohen, A. B., Sharp, C. A., & Hook, J. N. (2019). Development and validation of the five-factor LAMBI measure of god representations. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 11(4), 339–349. https://doi.org/10.1037/rel0000207

- Jung, J. H. (2018). Childhood adversity, religion, and change in adult mental health. Research on Aging, 40(2), 155–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027516686662

- Kelley, H. H., Galbraith, Q., & Korth, B. B. (2021). The how and what of modern religious transmission and its implications for families. Journal of Family Psychology, 35(4), 423–432. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000673

- Kiessling, F., & Perner, J. (2014). God–mother–baby: What children think they know. Child Development, 85(4), 1601–1616. https://doi.org/10.1111/CDEV.12210

- Killen, M., Elenbaas, L., & Rizzo, M. T. (2018). Young children’s ability to recognize and challenge unfair treatment of others in group contexts. Human Development, 61(4–5), 281–296. https://doi.org/10.1159/000492804

- Kim, J., Mccullough, M. E., & Cicchetti, D. (2009). Parents’ and children’s religiosity and child behavioral adjustment among maltreated and nonmaltreated children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 18(5), 594–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-009-9262-1

- Knight, N., Sousa, P., Barrett, J. L., & Atran, S. (2004). Children’s attributions of beliefs to humans and god: Cross-cultural evidence. Cognitive Science, 28(1), 117–126. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15516709cog2801_6

- Koenig, H. G., & Büssing, A. (2010). The Duke University Religion Index (DUREL): A five-item measure for use in epidemiological studies. Religions, 1(1), 78–85. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel1010078

- Konyushkova, K., Arvanitopoulos, N., Dandarova Robert, Z., Brandt, P.-Y., & Süsstrunk, S. (2016). God(s) Know(s): Developmental and Cross-Cultural Patterns in children drawings. ACM Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage, 2(3), 1–20. http://arxiv.org/abs/1511.03466

- Laird, S. P., Snyder, C. R., Rapoff, M. A., & Green, S. (2004). Research: Measuring private prayer: Development, validation, and clinical application of the multidimensional prayer inventory. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 14(4), 251–272. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327582ijpr1404_2

- Lane, J. D., Wellman, H. M., & Evans, E. M. (2010). Children’s understanding of ordinary and extraordinary minds. Child Development, 81(5), 1475–1489. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1467-8624.2010.01486.X

- Lanman, J. A., & Buhrmester, M. D. (2016). Religious actions speak louder than words: Exposure to credibility-enhancing displays predicts theism. Religion, Brain and Behavior, 7(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/2153599X.2015.1117011

- Lawrence, J. A., & Valsiner, J. (1993). Conceptual roots of internalization: From transmission to transformation. Human Development, 36(3), 150–167. https://doi.org/10.1159/000277333

- Laws of Malta. (2016). Malta’s Constitution of 1964 with Amendments Through 2016. https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Malta_2016.pdf?lang=en

- Long, D., Elkind, D., & Spilka, B. (1967). The child’s conception of prayer. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 6(1), 101–109. https://doi.org/10.2307/1384202

- Łowicki, P., & Zajenkowski, M. (2019). Empathy and exposure to credible religious acts during childhood independently predict religiosity. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 30(2), 128–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508619.2019.1672486

- Mahoney, A., Jouriles, E. N., & Scavone, J. (1997). Marital adjustment, marital discord over childrearing, and child behavior problems: Moderating effects of child age. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 26(4), 415–423. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp2604_10

- Mahoney, A., Pargament, K. I., Tarakeshwar, N., & Swank, A. B. (2008). Religion in the home in the 1980s and 1990s: A meta-analytic review and conceptual analysis of links between religion, marriage, and parenting. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 1, 63–101. https://doi.org/10.1037/1941-1022.S.1.63

- Malta Ministry for Education and Employment. (2013). Early childhood education & care in Malta: The way forward.

- Marmara, V. (2021). State of the nation survey. BMC Public Health, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11862-x

- Marmarà, V. (2023). State of the nation survey report. https://president.gov.mt/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Rapport-l-iStat-tan-Nazzjon-2023-VM-Final-Presentation.pdf

- McLoughlin, N., Cui, Y. K., Davoodi, T., Payir, A., Clegg, J. M., Harris, P. L., & Corriveau, K. H. (2023). Expressions of uncertainty in invisible scientific and religious phenomena during naturalistic conversation. Cognition, 237(April), 105474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2023.105474

- McLoughlin, N., Jacob, C., Samrow, P., & Corriveau, K. H. (2021). Beliefs about unobservable scientific and religious entities are transmitted via subtle linguistic cues in parental testimony. Journal of Cognition and Development, 22(3), 379–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/15248372.2020.1871351

- Merrilees, C. E., Cairns, E., Taylor, L. K., Goeke-Morey, M. C., Shirlow, P., & Cummings, E. M. (2013). Social Identity and youth aggressive and delinquent behaviors in a context of political violence. Political Psychology, 34(5), 695–711. https://doi.org/10.1111/POPS.12030

- Milevsky, I. M., Szuchman, L., & Milevsky, A. (2008). Transmission of religious beliefs in college students. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 11(4), 423–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674670701507541

- Mizzi Harber, M., & Grima, A. (1999). Nutrition in the early years of schooling. Issue May. University of Malta.

- National Statistics Office (NSO) Malta. (2021). Pre-primary, primary and secondary formal education: 2018-2019. Issue January

- National Statistics Office (NSO) Malta. (2023). Census of population and housing 2021: Final report: Population, migration and other social characteristics, 1

- Nesdale, D. (2004). Social Identity Processes and Children’s ethnic prejudice. In M. Bennett & F. Sani (Eds.), The development of the social self (pp. 219–245). Psychology Press, Taylor and Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203391099