ABSTRACT

Family-based treatment (FBT) is a first-line treatment for adolescents with eating disorders (ED’s) for which weight gain early in treatment and caregiver empowerment are predictive of success. A variety of dietary interventions are used in practice, but little is known about their effectiveness. We compared clinical outcomes of patients (N = 100) undergoing eating disorder treatment, and user experience across two virtually delivered interventions: (1) Daily calorie target and (2) Plate-by-Plate™ approach. The calorie group gained more weight on average, though the difference was small (β = 1.62 [−0.02, 3.26]). Participants in both groups improve their eating disorder symptoms at roughly the same rate (β = 0.09 [−0.83, 1.04]). Caregivers in the Plate-by-Plate group increased confidence at a slower rate (β = 0.05 [−0.002, 0.09]). Caregivers rated the daily calorie target as more effective (β = 2.18 [0.94, 3.6]), and rated the two approaches equally for ease of use (β = -0.73 [−1.92, 0.48]). The daily calorie target approach was rated as more effective and was preferred overall by caregivers and dietitians. Findings challenge long-standing assumptions underlying FBT and suggest that clinicians should consider using a calorie framework with caregivers to guide renourishment efforts.

Clinical implications

The daily calorie target demonstrated slightly more weight gain relative to the Plate-by-Plate approach. Other clinical outcomes were not different across treatment groups.

Dietitians expressed an overall preference for the daily calorie target intervention, and both dietitians and caregivers rated it more effective for weight restoration.

Despite longstanding safety concerns around use of a daily calorie target in practice it appears to be a safe, effective and well accepted approach for caregivers of individuals engaged in FBT for an eating disorder.

Introduction

Eating disorders (EDs) impact people across all ages, genders, races, ethnicities, and body size (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). National ED prevalence estimates are 9%, and anorexia nervosa (AN) specifically has the second highest mortality rate (Chesney et al., Citation2014). Family-Based Treatment (FBT), the first-line treatment for adolescents and young adults, is an approach through which caregivers are empowered to renourish their child at home, with the support and guidance of trained specialists. FBT is the preferred approach for AN, and has demonstrated promise for other ED subtypes (Le Grange et al., Citation2007; Lock et al., Citation2018). This approach rests upon the fundamental importance of parental empowerment and self-efficacy, and the therapist taking a non-authoritarian stance in treatment in order to support parental empowerment.

Nutritional rehabilitation is a central treatment element across all ED subtypes, and weight gain within the first few weeks of FBT is considered a primary predictor of remission (Le Grange et al., Citation2013; Marzola et al., Citation2013). Nutrition requirements for patients with ED’s are uniquely complex and require individualization, as patients often present with a myriad of micronutrient and macronutrient deficiencies as well as metabolic alterations (Marzola et al., Citation2013). Kilocalorie needs can reach 70–100 kcals/kg/day, and caregivers generally require guidance to successfully navigate home-based refeeding.6 While RD support is part of standards of care in all other ED treatment modalities aside from FBT, in this approach, guidance around feeding has historically been provided only by a family therapist, as specialized nutrition support is thought to undermine parental empowerment (Lian et al., Citation2019; Patterson et al., Citation2022). However, the RD supports various needs that arise over the treatment course (management of malnutrition, refeeding syndrome, weight plateaus, slow rate of weight gain, gastrointestinal symptoms, erroneous belief systems around food and weight, lack of diversity in food choices, needs adjustments for patients returning to sport) that may be unaddressed by therapists, but are vital for remission (Lian et al., Citation2019; Schmidt et al., Citation2021). Assessment of an appropriate and individualized target weight also generally falls under the RD’s purview in most settings, and is of critical importance for a successful outcome (Lian et al., Citation2019; Steinberg et al., Citation2023).

A variety of dietary interventions are used in practice across the EDs field, often dependent on the RD’s training and expertise. Briefly, the most common interventions used in practice are 1) daily calorie target approach; 2) Plate-by-Plate™ model; and 3) Daily Exchanges. Lian et al., Citation2019 In the daily calorie target approach, caregivers are provided a daily kilocalorie goal, and generally the number of meals and snacks will also be prescribed, each with an associated kilocalorie goal. Calorie targets are sometimes provided to caregivers as a means of guiding home-based refeeding efforts, though they have historically been regarded as ‘too prescriptive’ with potential to undermine caregiver instincts around feeding. The Plate-by-Plate™ model is a visual approach developed specifically for use in FBT. Caregivers are instructed to prepare ‘normal’ portions/plates versus using calories to guide meal planning with plates consisting of 50% starch, 25% protein, 25% vegetables/fruits, with dairy and fat servings specified by the RD for the meals. Key features of this approach include primary caregivers making the decision around what and how much to serve, with an emphasis on dietary variety and exposure to all foods (Sterling et al., Citation2019). These features are thought to uphold parental empowerment and reinforce caregiver self-efficacy, both core tenets of FBT (Rienecke & Le Grange, Citation2022). The daily exchange system is seldom used in FBT given the different needs of caregivers versus patients, and as such, was not included as an intervention Sterling et al., Citation2019.

Despite widespread use of these interventions among ED specialists, existing research on their effectiveness is sparse. This randomized comparison study examined the preliminary effectiveness and acceptability of 1) Daily calorie target and 2) The Plate-by-Plate™ approach for families undergoing virtually delivered FBT. We hypothesized that families assigned to the daily calorie target group will experience greater weight gain and will show no meaningful differences in patient reported ED symptom severity, caregiver burden and caregiver self efficacy. We also anticipate higher ratings for effectiveness for the daily calorie target group across both caregivers and RD interventionists, but that caregivers will give higher scores for ease of use for the Plate-by-Plate™ model. Finally, we expect that a daily calorie target will be preferred overall by both interventionists and caregivers.

Methods

Participants

Participants self-selected for virtual eating disorder treatment across the U.S. Eligible patients were ages 6–24, diagnosed with AN or ARFID, and had an apparent need for weight restoration upon admission to the program. Both AN and ARFID were included because weight gain was a primary outcome, and was most likely to be a goal of treatment for this group of participants. Further, there is no research on dietary interventions in FBT for patients with ARFID (Hellner et al., Citation2023) Participants must have consented to participate in treatment optimization research upon program admission, and be assigned to a trained RD interventionist. Participants were screened by study personnel at the time of program admission. This study was reviewed by the Biomedical Research Alliance of New York (BRANY) IRB, and it was determined it does not meet criteria for human subject’s research. This is a quality improvement study, and thus, did not require registration on clinicaltrials.gov.

Recruitment and group assignment

Patients seeking treatment inquired through email or phone. One hundred eligible patients who enrolled in ED treatment on a rolling basis from May 2022 through August 2022 were randomized using a block design to receive either the daily calorie target approach or the Plate-by-Plate™ approach during sessions with the RD.

Final sample

Of the 100 patients randomized, 24 were administratively withdrawn: 5 of the 24 discharged prior to study completion, 6 were determined to be weight restored upon admission after further review, 7 were withdrawn from the study per clinical judgment (3 expressed a strong preference for an approach other than Plate-by-Plate, 2 expressed a strong preference for an approach other than the daily calorie target, and 2 changed diagnoses), 4 changed treatment providers during treatment, and 2 deferred admission. Of those withdrawn, 12 were in the Plate-by-Plate group and 12 were in the daily calorie target group. This left 76 participants for analysis, 38 in each of the two treatment groups.

Assessments and measures

Outcome measures are described briefly below, and in more depth elsewhere (Hellner et al., Citation2023). The following demographic data were extracted from the medical record: age, state of residence, biological sex, gender identity, ED diagnosis, and height.

Patient measures

Upon admission, caregivers receive instruction from medical personnel on proper procedure for weight collection and scale calibration. Weights are taken in the morning, after voiding, prior to any oral intake and patients are asked to wear light clothing. Caregivers are also instructed by medical personnel upon permission on scale calibration and weight collection. Weight is taken by caregivers at baseline and twice weekly and communicated via text message to a HIPAA-compliant medical record platform. For each patient, the RD calculates a minimum target weight for weight restoration. Target weight is calculated using expected weight data from each patient’s CDC BMI-for-age Growth Charts. Growth charts are collected upon admission and reviewed prior to the RD intake assessment. Deviations from the patient’s growth trajectory at the onset of the eating disorder are noted, with the objective generally being to restore the patient to their premorbid growth trajectory. Additional information that may be used by the RD in assessment of EBW includes assessment of current dietary intake and eating disorder behaviors, current and historical physical activity patterns, and all available medical data. Caregivers are asked to provide information about lifestyle patterns associated with weight changes at various time points as noted on the growth charts. For patients with a prepubertal ED onset, the RD uses prepubertal weight to determine trajectory and adjusts target weights as needed throughout treatment.

The Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire Short Form (EDE-QS) was used to assess eating disorder symptoms, and was given at baseline and weekly thereafter. The EDE-QS, an abbreviated 12-item version of the 28-item Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) survey, captured eating disorder symptom severity (Gideon et al., Citation2018).

Caregiver measures

Caregivers completed the Burden Assessment Scale (BAS) questionnaire at baseline and every 40 days thereafter, which measures specific objective and subjective caregiver consequences of individuals with mental illness (Reinhard et al., Citation1994). They were also given the Parent Versus Eating Disorder (PVED) scale at day 14 and every 40 days thereafter, which was adapted from the Parent Versus Anorexia (PVA) scale. The PVED was designed to capture caregivers’ belief in their ability to overcome their loved one’s eating disorder (Rhodes et al., Citation2005). Finally, a semi-structured interview (Appendix A) was completed with caregivers after week 8 of treatment via phone to assess experience with the assigned renourishment strategy, which included the following two likert-scale questions which assessed perceived effectiveness and ease of use:

On a scale of 1–5, with 1 = ‘very ineffective’ and 5 = ‘very effective’, how effective do you feel this approach was in helping your child restore weight?

On a scale of 1–5, with 1 = ‘very difficult to use’ and 5 = ‘very easy to use’, how easy do you feel this approach was for you to learn and implement/use?

Interventionist measures

A semi-structured interview with the RD interventionists (Appendix B) was completed via Zoom to assess the interventionists general experience with each approach at the end of the study period. RDs were also asked to rate on a scale of 1–10 the effectiveness of each approach for weight restoration, the ease of implementing each approach in session, and caregiver receptivity to each approach.

Procedures

In the first phase of treatment, the RD met exclusively with caregivers weekly for the first 4 weeks, and thereafter either weekly or every other week in accordance with the RD’s clinical judgment and mutual availability. At the end of the first session, caregivers were introduced to the assigned intervention. Caregivers were instructed to supervise, support, and prompt the patient to complete meals and snacks, and in the case of food refusal, oral supplements were recommended to replace remaining nutrition. Goals for optimal rates of weight restoration (1–2 lbs/week) are shared with caregivers in the first or second session with the RD, and are supported by the initial nutrition prescription and by the escalating adjustments made to the prescription in subsequent sessions.

A summary of each intervention’s procedures is as follows:

Daily calorie target: Caregivers were prescribed a daily calorie goal. For example, the goal of 3000 kcals/day may include 700 kcal meals 3 times daily, and 300 kcal snacks 3 times daily. Additionally, caregivers were provided 7-day sample menus that align with their calorie prescription. Adjustments were made throughout the treatment course to calorie goals to facilitate the recommended rate of weight gain of 1–2 lbs per week. During the initial session, caregivers were instructed to send photos and caloric density estimates of all meals or items consumed by the patient to the RD, and feedback was given around adequacy of intake in follow-up sessions.

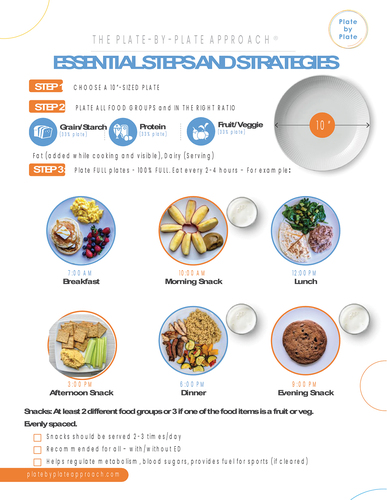

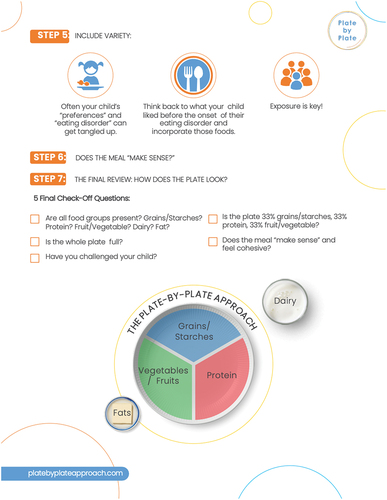

The 7-step Plate-by-Plate™ model was reviewed in session one with caregivers, and a summary of steps were shared via an electronic handout (Appendix C). As part of the model, the caregivers were advised to offer three meals and either two or three snacks. Similar to the daily calorie target group, RD’s provided supporting resources (pictures of appropriately plated meals and snacks), and RD’s reviewed photos taken by caregivers of meals and snacks in subsequent sessions, offering guidance around the adequacy of portion sizes.

Step 1: Choose 10-inch plate

Step 2: Plate all food groups

Step 3: Fill plate

Step 4: Caregiver decides whether to include 2 or 3 snacks

Step 5: Include variety

Step 6: Does the meal make sense?

Step 7: Final review: Does the plate make sense?

Training and fidelity

Therapist credentials include licensed social workers, marriage and family therapists, or psychologists. As part of standard operating procedures, all are trained on manualized FBT. Fidelity raters review therapy sessions to ensure that providers are maintaining fidelity to FBT. All providers receive extensive training and group and individual supervision on FBT at regular (generally weekly) intervals thereafter.

The RD interventionists underwent a live training session overviewing study protocols, and a pre-recorded training on the Plate-by-Plate™ intervention (led by the authors of Plate-by-Plate™). Interventionists were trained to notify research staff of any fidelity issues or protocol deviations.

Electronic records were reviewed by study personnel on a weekly basis to ensure adherence to the assigned treatment approach. Training and fidelity are outlined in more detail elsewhere (Hellner et al., Citation2023).

Statistical analysis

Treatment outcomes were collected via our HIPAA-compliant medical record platform, and were extracted by trained research personnel. Clinical outcomes were evaluated throughout the entirety of a patient’s treatment course. Chi-squared tests and t-tests were used to explore statistical differences among demographic variables across treatment groups using an alpha of 0.05 for significance testing. Bayesian general linear models were used to estimate the treatment effect on weight and ED symptoms, and to estimate how caregivers rated the treatments.

Treatment effect over time was estimated using a linear model fitting to patient weights. The model included intervention group, (log) treatment week, and their interaction. The patients target weight and the interaction between the target weight and log treatment week were added as covariates to adjust for the fact that patients with higher target weights might either start out with higher weights on average or take slightly different trajectories through treatment. The target weight was z-scored. Random effects intercepts, and patient-level slopes on the logged treatment weeks allowed for different patient trajectories through treatment. In a second model, weight change over time was estimated using the patient’s weight expressed as a proportion of their target weight with a linear model using the same model terms as above. Missing values were imputed in the Bayesian analysis, but the analysis was also run using only the complete observations, and the results were consistent. The EDE-QS, PVED, and BAS surveys are likert-style response scales. In these cases, similar modeling was performed, except target weight was not included, and an ordinal logistic link function was used. Caregiver ratings of the effectiveness and ease of use of the assigned intervention were estimated with multivariate ordinal logistic regression. Terms included in the model were the intercepts (cutoffs for each latent category boundary), and the treatment group.

All analysis was performed in R (version 4.2.3) using the tidyverse (version 2.0.0). The R targets package was used as the analysis management tool (version 0.14.3) (Landau, Citation2021). Bayesian models were run using brms (version 2.19.0; Bürkner 2017, 2018, 2021) which is a wrapper around the Stan probabilistic programming language (cmdstan version 0.5.3; Stan Development Team, 2023). All models were run with 4 chains (2,000 warmup samples, 3,000 total iterations) on a Macbook Pro 2.6 GHz 6-Core Intel Core i7 with 16 GB of ram. All models converged with.

Qualitative analysis of interview data

Caregiver and RD interventionist’s interviews were completed remotely via Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) compliant Zoom platform by doctoral level research personnel and responses transcribed verbatim into an electronic survey document. Thematic analysis was used to analyze interview transcripts, beginning with data familiarization, and then data were coded using an inductive approach. Caregiver interviews were analyzed within each intervention group, and clinician interviews across the two interventions. Themes were then summarized in text, and direct quotes representative of content were identified.

Results

Demographics

The patient sample ranged from 11 to 23 years old (M = 15.2, SD = 2.4). Most patients identified as cisgender females (82.9%); the remaining identified as cisgender males (6.6%), non-binary (4%), transgender males (2.6%), and other (4%). Most patients identified as White (72.4%); the remaining identified as BIPOC (25%) or did not specify their race or ethnicity (2.6%). Our sample consisted of 68.4% of patients diagnosed with AN restricting subtype (AN-R), 18.4% with AN binge/purge subtype (AN-BP), and 13.2% with ARFID.

The treatment groups (daily calorie target and Plate-by-Plate™) did not significantly differ in age (t(74) = –0.58, p = .57), gender (X2 = 5.1, p = .35), race or ethnicity (X2 = 2.1, p ≈ 1), diagnosis (X2 = 2.6, p = .3), prior treatment status (X2 = 0.6,p ≈ 0.99), or comorbidities (X2 = 6.95, p = .73). Both groups had a similar amount of weight to gain at the start of treatment (t(60.93) = 0.4, p = .69).

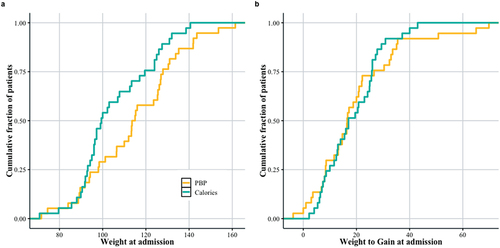

Weight changes

shows the distribution of patient weights at treatment onset, and 1b shows distribution of the amount of weight they need to gain in order to reach their target weight. While there were more patients in the daily calorie target group () with lower weights relative to the Plate-by-Plate™ group, groups were not significantly different in terms of amount of weight required for weight restoration (). The calorie group’s average weight upon admission was 105 lbs (SE = 3.06), and at week 24 of treatment was 121 lbs (SE = 3.04). The Plate-by-Plate™ group averaged 108 lbs (SE = 3.3) upon admission and 119 lbs (SE = 3.1) at week 24. Over the first 24 weeks, the average percent of the goal weight across groups increased from 83% (SE = 2%) to 96% (SE = 2%) for the calorie group and 85% (SE = 2%) to 93% (SE = 2%) for Plate-by-Plate™ (). Approximately 25% of the patients in both groups had admission weights under 100 lbs. However, the daily calorie target group has a higher density of patients with lower weights (approximately 100 lbs) than the Plate-by-Plate™ group, with the highest density of patients around 130 lbs, which was unexpected due to the randomization experimental design. Patients in both groups have roughly the same amount of weight to gain, with 25% of patients requiring less than 10 lbs, and 75% of patients less than 30 lbs. The median amount of weight gain required across patients was 20 lbs.

Table 1. Summary of patient demographic and outcome differences across treatment groups*.

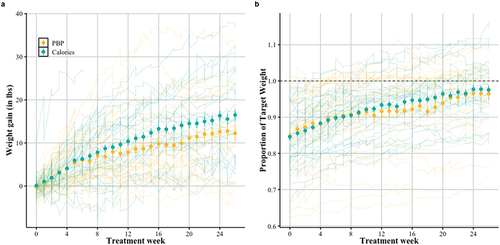

show weight gain in the first 6 months (26 weeks) of treatment. shows weekly rate of weight gain (lbs), and shows the patient’s weight expressed as the proportion of their target weight (such that at 1.0 the patient has reached the target weight). The large filled circles represent the mean, and the error bars the standard error of the mean. The individual patient trajectories are shown as light lines in the background. There are considerable individual differences across patients.

Both groups gained weight over treatment (β = 3.45 [2.27, 4.65]). The daily calorie target group gained more weight on average (), relative to the Plate-by-Plate™ approach (β = 1.62 [−0.02, 3.26]). Similarly, shows that patients take nearly identical trajectories toward their individualized weight targets, although the model’s best estimate is that the daily calorie target group’s trajectory is steeper (β = 0.01 [−0.002, 0.03]). There is considerable variability in how patients progress through treatment, but on average weight increases logarithmically throughout treatment. The daily calorie target approach showed slightly higher weight gain, but the difference between the approaches is small. Given that, in this patient population, the median target weight is about 20 lbs above weight upon admission, and patients gain roughly 0.6 lbs per week, the average patient will reach their target at 30–35 weeks. Patients on both approaches move toward their target weight at roughly the same rate, although patients in the daily calorie target group show a slightly steeper increase.

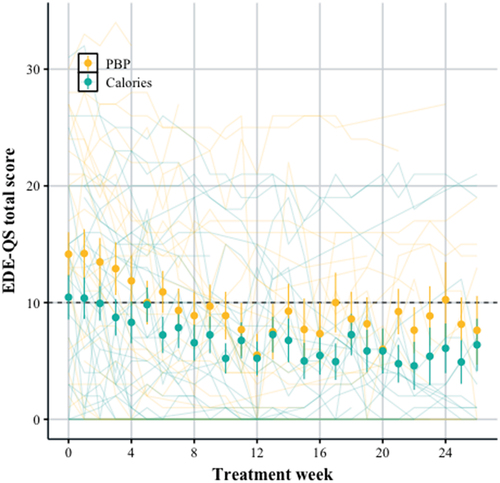

Eating disorder symptoms (EDE-QS)

shows improvement in eating disorder symptoms (EDE-QS scores) for patients with AN over the first 26 weeks of treatment in both the daily calorie target and Plate-by-Plate™ groups (β = –1.41 [−2.12, −0.75]). The large filled circles represent the mean (with standard errors), and the individual patient trajectories are displayed in the background. The daily calorie target group appears to have slightly lower scores upon admission and throughout treatment, though there is high uncertainty around this estimate (β = –3.06 [−6.56, 0.52]). The individual patient scores show considerable variability. Patients in both groups improve their eating disorder symptoms at roughly the same rate (β = 0.09 [−0.83, 1.04]). On average eating disorder symptoms decrease logarithmically throughout treatment. The average score improved from 14.7 to 6.6 over 24 weeks for the daily calorie target group, and 19.2 to 11.9 for Plate-by-Plate™ group ().

Caregiver burden (BAS)

Caregivers in both groups reported feeling less burdened over time (β = –0.07 [−0.12, −0.02]), but there were no reliable differences in the ratings between caregivers in the daily calorie target or Plate-by-Plate™ groups (β = 0.42 [−0.6, 1.45]).

Caregiver confidence (PVED)

Similarly, parents felt more confident in their role supporting the patient through treatment (β = 0.07 [0.03, 0.10]). The caregivers in the Plate-by-Plate™ group may have increased their confidence at a slower rate, but the estimated effect is small with large uncertainty (β = 0.05 [−0.002, 0.09]).

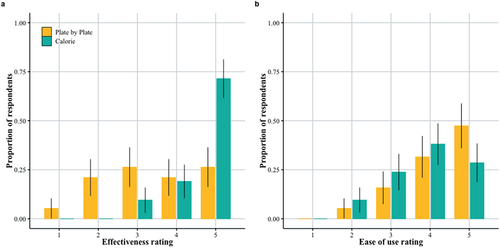

Caregiver survey ratings – effectiveness and ease of use

As part of the caregiver semi-structured interview, caregivers were asked to rate on a scale of 1–5 how effective they felt their assigned approach was in helping their child restore weight, and how easy they felt the approach was for them to learn, implement, and use. There were 40 responses total (21 in daily calorie target group, 19 in Plate-by-Plate™ group). Despite the above result that both approaches had similar levels of effectiveness, caregivers felt that the daily calorie target approach was more effective (β = 2.18 [0.94, 3.6]). More caregivers scored a 5 (very effective) in the daily calorie target group than any other score, and compared to the Plate-by-Plate™ group (). Caregiveres rated the two approaches similarly for ease of use (; β = –0.73 [−1.92, 0.48]).

Outcomes from caregiver semi-structured interviews- plate-by-Plate™

Many of the caregivers assigned to the Plate-by-Plate™ felt that it was easy to learn, and the approach was noted by caregivers who routinely cook and prepare family meals to be a natural fit (versus those more apt to rely on prepared foods/take-out). They also appreciated the accompanying example photos, and specifically those who cited having an aversion to counting and measuring enjoyed having a ‘visual approach’ as an alternative.

Having to count or measure would have been overwhelming at first and anxiety is already very high.

Caregivers also felt that use of Plate-by-Plate™ would facilitate a more seamless transition to later phases of FBT.

Not having to count calories is beneficial as they aren’t often available on many of the foods we eat. It will be helpful for our daughter as well, when it comes time for her to manage the meals herself. It’ll be a good transitional plan. (Participant 2)

Caregivers in the Plate-by-Plate™ group also shared a number of concerns with this approach. Many felt it to be a better fit for later stages of treatment, and preferred more explicit guidance around how much and what to feed their child earlier on. They expressed fear around caloric density being inadequate as well to achieve an optimal rate of weight restoration. Many shared that the ‘full plate’ was overwhelming for their child. Caregivers who were using a different approach prior to admission and vegetarian families also struggled more with Plate-by-Plate™.

Outcomes from caregiver semi-structured interviews-daily calorie target group

Caregivers assigned a calorie target regarded the target as a necessity for success with home-based refeeding, especially in the early stages of treatment. Some felt that parents need to be aware of specific requirements for weight restoration, as needs were not intuitive. Many expressed frustration with not being given a calorie target in prior encounters with ED providers, and specifically with being discouraged from using a calorie-counting framework.

The thing that I find interesting is that it is contrary to what everyone had told us about having a calorie target. I’m so angry for being told that for so long. (Participant 3)

It was really helpful. I’d seen nutritionists in the past, and they would say ‘eat more, she needs more’. I never got a straight answer on how much she needs. It was frustrating. Knowing the calories gave me some much needed clarity. (Participant 4)

Many referred to having a calorie target as ‘game changing’.

This is the first thing that’s worked after years of treatment. We’ve been told by other programs never to talk about calories. It was all really vague, and I’m so excited to talk with you about this, because it was exactly what we needed. Once we presented the calorie target to our daughter, she felt more secure and was suddenly totally on board. She likes the certainty and feels more safe. (Participant 5)

The daily calorie target approach was generally well accepted by caregivers who used a different approach prior to admission, and was consistently preferred for use with higher acuity cases and ARFID cases. Caregivers who identified as ‘more analytical’ or ‘numbers people’ preferred calories, and some cited their preference for calorie counting as a product of past struggles with disordered eating, as they were already savvy with caloric density of various foods. Caregivers liked that it allowed for reliance on more compact meals of smaller volume, which helped by alleviating some fullness and by reducing the overwhelm experienced by the patient. A few noted that having a specific calorie goal decreased meal time conflict.

For us, it was literally life changing. It is the only reason she is back in school as we speak. The ability to know what she is getting and to be in control has been key to her not starving herself. (Participant 6)

Other sentiments expressed by most of the caregivers in this group were that having a daily calorie target gave them peace of mind and confidence that needs were being met, and allowed for an objective assessment of adequacy of meals and snacks. Nearly all reported feeling empowered by having a daily calorie target, especially as the targets were frequently adjusted early in treatment. “Knowing the calories was instrumental for me in mastering the weight gain piece”.

Caregivers also spoke to the limitations of the daily calorie target approach. Many felt it was tedious and time consuming, especially in the first several weeks of treatment, with a ‘steep learning curve’, especially for caregivers who weren’t as familiar with calorie content of foods. Many also anticipated some challenges in having to likely learn a different approach in later phases of FBT.

Dietitian semi-structured interviews

The RDs (N = 7) cited the following as primary benefits of the Plate-by-Plate™ approach: Ease of instruction, helpful visual aids, easy to assess caregiver understanding of concepts. They also expressed a preference for this approach for use with caregivers with lived experience with an eating disorder, and as a favorable transitional approach for later stages of FBT. However, they noted that caregivers who presented as ‘more analytical’ in nature perceived Plate-by-Plate™ as too ambiguous or vague, often expressing preference for more direct guidance (i.e. a numeric target). They felt the ambiguity gave way to more resistance and ED-rooted negotiations. They found this approach more difficult and less acceptable for higher acuity patients and also those struggling with feelings of persistent fullness.

Regarding the daily calorie target, the RD’s described it as straightforward, concrete and less ambiguous relative to Plate-by-Plate™. They found it easier to assess adequacy of intake, and felt more confident that the patient’s caloric requirements were being met. They found this approach to be more successful and effective overall, in particular for facilitating a more optimal rate of weight restoration. However, they expressed that the daily calorie target took longer for carers to learn, and they perceived it to be overwhelming in caregivers when the target was higher than caregivers may have expected.

They were also asked to rate on a scale of 1–10 the (a) effectiveness of each approach for achieving an optimal rate of weight restoration, (b) ease of implementing each approach in session, and (c) caregiver receptivity to each approach. Five of seven rated the daily calorie target approach as more effective than Plate-by-Plate™. For ease of implementation, 3 of 7 rated the daily calorie target approach higher, 2 rated Plate-by-Plate™ higher, and 2 rated both approaches equally. For caregiver receptivity, 3 of 7 rated the Plate-by-Plate™ approach higher, 2 rated the daily calorie target approach higher and 2 rated both equally. Overall, when asked if they felt one was best for primary use in practice, 5 out of 7 preferred the daily calorie target over the Plate-by-Plate™ approach.

Discussion

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this was the first randomized comparison study of virtually-delivered dietary interventions for treatment of ED’s. The daily calorie target was preferred and deemed more effective overall in this setting in the early phase of treatment by both clinicians and caregivers. Additionally, the calorie group gained more weight over the study period, though the difference was small.This study was also the first to challenge long standing assumptions underlying FBT. Findings contrast the existing literature recommending against the use of the calorie framework in FBT, which specifically cite concerns around the approach being overly prescriptive, rigid and having potential to worsen ED symptoms (Lian et al., Citation2019; Sterling et al., Citation2019). On the contrary, caregivers felt empowered by the guidance they received around their child’s nutritional requirements, particularly during a time of crisis. While some caregivers express an aversion to calorie-counting, interview findings suggested that many more preferred to leverage their analytical strengths, and consequently felt that a specific calorie target enabled them to approach renourishment with clarity and confidence. The authors also felt it reasonable to assume that use of an approach that is perceived as more effective and favored overall may support motivation and rapport building.

Despite these strengths, there are a few noteworthy limitations. First, although FBT is indicated for ages 6–24, it is possible that there may be differences in how a family responds to an intervention across age ranges or developmental stages. While bias was minimized by randomization, we were unable to identify all potential confounding factors, such as prior treatment history. It is also possible that caregivers’ outcomes and ratings of interventions may have been different at the end of their treatment journey, though we were particularly interested in the early treatment response given that early response is predictive of recovery. Further, while the calorie group gained more weight on average, the difference was small, and it is possible that smaller sample size limited the ability to find statistically significant differences between groups. However, this was a comparative effectiveness study, where we were isolating small effects. Finally, results from patients with ARFID should be interpreted with caution given the small sample.

The mixed-methods design is a primary strength of this study. Given potential for important context to be lost when relying too heavily on quantitative outcomes, we felt it important to include a live interview component, which allowed space for rich discussion and a multi-dimensional understanding of their experience with the interventions. We were able to capture aspects of the patient, caregiver and clinician experience, which, taken together, supported use of a daily calorie target as a favored intervention. Also, our findings supported the notion that use of a calorie target does not contradict important core tenets, such as caregiver empowerment.

Conclusions

The daily calorie target emerged as the favored intervention by both clinicians and caregivers. However, In alignment with FBT’s ‘parental empowerment’ tenet, caregivers may be presented with options should they express a strong preference for a different approach given that both groups improved over the treatment course.

Future research should compare dietary interventions across other ED subtypes using larger sample sizes, and look at effectiveness of interventions across age and developmental stages. Testing daily calorie targets in treatment modalities outside of FBT may also be worthwhile.

Disclosure statement

All authors have equity in Equip Health.

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders DSM-5 (5th ed.). APA.

- Chesney, E., Goodwin, G. M., & Fazel, S. (2014). Risks of all-cause and suicide mortality in mental disorders: A meta-review. World Psychiatry, 13(2), 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20128

- Gideon, N., Hawkes, N., Mond, J., Saunders, R., Tchanturia, K., & Serpell, L. (2018). Correction: Development and psychometric validation of the EDE-QS, a 12 item short form of the eating disorder examination questionnaire (EDE-Q). Public Library of Science One, 13(11). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0207256

- Hellner, M., Steinberg, D., Baker, J. H., & Blanton, C. (2023). Digitally delivered dietary interventions for patients with eating disorders undergoing family-based treatment: Protocol for a randomized feasibility trial. JMIR Research Protocols, 12, 12. https://doi.org/10.2196/41837

- Landau, W. (2021). The targets R package: A dynamic Make-like function-oriented pipeline toolkit for reproducibility and high-performance computing. Journal of Open Source Software, 6(57), 2959. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.02959

- Le Grange, D., Accurso, E. C., Lock, J., Agras, S., & Bryson, S. W. (2013). Early weight gain predicts outcome in two treatments for adolescent anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47(2), 124–129. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22221

- Le Grange, D., Crosby, R. D., Rathouz, P. J., & Leventhal, B. L. (2007). A randomized controlled comparison of family-based treatment and supportive psychotherapy for adolescent bulimia nervosa. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(9), 1049–1056. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.64.9.1049

- Lian, B., Forsberg, S. E., & Fitzpatrick, K. K. (2019). Adolescent anorexia: Guiding principles and skills for the Dietetic support of family-based treatment. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 119(1), 17–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2017.09.003

- Lock, J., Robinson, A., Sadeh‐Sharvit, S., Rosania, K., Osipov, L., Kirz, N., Derenne, J., & Utzinger, L. (2018). Applying family‐based treatment (FBT) to three clinical presentations of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: Similarities and differences from FBT for anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 52(4), 439–446. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22994

- Marzola, E., Nasser, J. A., Hashim, S. A., Shih, P. B., & Kaye, W. H. (2013). Nutritional rehabilitation in anorexia nervosa: Review of the literature and implications for treatment. BMC Psychiatry, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244x-13-290

- Patterson, J., Myers, J. L., Gallagher, E., Hartman, G. R., Lewis, J. B., Royster, C., Easton, E., O’Melia, A., & Rienecke, R. D. (2022). Family-empowered treatment in higher levels of care for adolescent eating disorders: The role of the registered dietitian Nutritionist. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 122(10), 1825–1832. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2022.06.010

- Reinhard, S. C., Gubman, G. D., Horwitz, A. V., & Minsky, S. (1994). Burden assessment scale for families of the seriously mentally ill. Evaluation and Program Planning, 17(3), 261–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/0149-7189(94)90004-3

- Rhodes, P., Baillie, A., Brown, J., & Madden, S. (2005). Parental efficacy in the family-based treatment of anorexia: Preliminary development of the parents versus anorexia scale (PVA). European Eating Disorders Review, 13(6), 399–405. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.661

- Rienecke, R. D., & Le Grange, D. (2022). The five tenets of family-based treatment for adolescent eating disorders. Journal of Eating Disorders, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-022-00585-y

- Schmidt, R., Hiemisch, A., Kiess, W., von Klitzing, K., Schlensog-Schuster, F., Hilbert, A. (2021). Macro- and micronutrient intake in children with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder. Nutrients, 13(2), 400. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13020400

- Steinberg, D. M., Perry, T. R., Freestone, D., Hellner, M., Baker, J. H., & Bohon, C. (2023). Evaluating differences in setting expected body weight for children and adolescents in eating disorder treatment. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 56(3), 595–603. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23868

- Sterling, W., Crosbie, C., Shaw, N., & Martin, S. (2019). The use of the plate-by-plate approach for adolescents undergoing family-based treatment. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 119(7), 1075–1084. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2018.06.011

Appendix A:

Caregiver interview script

Was your child prescribed a daily calorie target, or the Plate-by-Plate approach by your dietitian?

How would you describe your experience initially (at start of treatment) with the approach your dietitian used?

How did your thoughts on/feelings about the approach change over time?

What do you think are the benefits and challenges of the approach?

Do you have suggestions for how we could have adapted or changed the approach to make it easier and more effective for you?

On a scale of 1–5, with 1 = ‘very ineffective’ and 5 = ‘very effective’, how effective do you feel this approach was in helping your child restore weight?

On a scale of 1–5, with 1 = ‘very difficult to use’ and 5 = ‘very easy to use’, how easy do you feel this approach was for you to learn and implement/use?

Do you have any other comments or insights you’d like to share?

Appendix B:

Dietitian interview script

How would you describe the pros and cons of the Plate-by-Plate approach as they pertain to you as a provider? Please include thoughts around how easy it was to teach to caregivers, how easy it was to make adjustments, caregiver receptivity and effectiveness.

How would you describe the pros and cons of the daily calorie target approach as they pertain to you as a provider? Please include thoughts around how easy it was to teach to caregivers, how easy it was to make adjustments, caregiver receptivity and effectiveness.

Describe your approach and experience giving guidance to the patient directly in phase II of FBT. How did that differ by approach used by the family?

How would you describe the pros and cons of Plate by Plate in thinking about the caregiver experience?

How would you describe the pros and cons of the daily calorie target approach?

Did you notice any differences or similarities across eating disorder subtypes?

Describe which approach felt more successful and why. How did this differ by eating disorder subtype?

What surprised you most about using each approach with caregivers?

Do you have any other thoughts or insights you’d like to share?

On a scale from 1-10, with 1 being worst, 5 being average, and 10 being best how would you rank:

The effectiveness of the Plate by Plate approach for weight restoration?

The effectiveness of the daily calorie target for weight restoration?

The ease of implementing the Plate by Plate approach in session?

The ease of implementing the daily calorie target in session?

Caregiver receptivity to the Plate by Plate approach?

Caregiver receptivity when using the daily calorie target approach?

All other things equal, did you prefer the Plate by Plate or daily calorie target?

Appendix C:

Plate-by-plate instructions