ABSTRACT

This paper presents findings from an original survey of US public attitudes toward nuclear proliferation issues to determine what types of elite messaging, if any, impact those attitudes. It considers two contemporary proliferation topics, the Iran nuclear deal and the AUKUS nuclear-powered-submarine initiative, making it among the first to gather data on how Americans view the trilateral security partnership among Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The findings demonstrate that elite messaging does impact attitudes toward proliferation issues, but that those effects vary across different issues. Various types of messaging impacted attitudes toward the Iran deal, whereas only messaging related to alliance considerations impacted attitudes toward the AUKUS initiative. Although the survey provides mixed results as to whether different types of messaging have distinct effects on proliferation attitudes, the findings further reveal that opposition to the Iran deal is particularly insensitive to messaging and that messaging does more to confuse than clarify public views on the AUKUS initiative. The survey results provide insight into the nature and pliability of Americans’ proliferation attitudes, with important implications for policy makers seeking to identify effective messaging strategies for engaging the public on future nuclear-proliferation policies.

Introduction

From pervasive concerns about Iran’s nuclear activities to mainstream discourse around a potential South Korean nuclear-weapons program, nuclear-proliferation issues increasingly occupy foreign-policy agendas. Russia’s invasion of and threats of nuclear use against Ukraine have induced concern that other states may seek nuclear weapons. US Secretary of State Antony Blinken hinted at this possibility during the August 2022 review conference of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), stating that Russia’s behavior sends “[t]he worst possible message … [to] any country around the world that may think that it needs to have nuclear weapons to protect, to defend, to deter aggression against its sovereignty and independence.”Footnote1

Most proliferation scholarship focuses on state and elite actors, from why and how states pursue nuclear-weapons programs to the effectiveness of various nonproliferation efforts.Footnote2 Comparatively little attention focuses on the public’s engagement with nuclear-proliferation issues, although some important research has analyzed public opinion on questions of nuclear-weapons use.Footnote3 What exactly does the public think about the potential spread of nuclear weapons? How might those opinions change? Does messaging impact the public’s proliferation attitudes?Footnote4

This paper helps to fill that gap by examining the nature of public opinion on nuclear-proliferation issues. It specifically focuses on American public opinion regarding two prominent issues of relevance to the United States: the Iran nuclear deal—formally known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)—and the AUKUS nuclear-powered-submarine initiative.Footnote5 The study is premised on the assumption that public opinion on proliferation issues matters and, more specifically, that public attitudes toward nonproliferation agreements are important—though not entirely dispositive—determinants of their durability. Existing scholarship at the nexus of foreign policy and public opinion supports this assertion.Footnote6 Numerous scholars have demonstrated the often indirect ways in which public opinion can affect foreign policy—constraining decision makers, shaping priorities, and exerting political costs, to name a few.Footnote7 Moreover, public support contributes to the sustainability of policies. It gives policy makers an important tool for combating critics, helping to provide political cover to advance and implement their policy objectives. Failure to garner public support can have the opposite effect. For instance, the Clinton administration struggled to build public support for the 1994 Agreed Framework, which aimed to thwart a North Korean nuclear-weapons program.Footnote8 That left the administration without a key bulwark against Republican opposition, emboldening Republicans in Congress to withhold the funding needed to implement the deal, which contributed to its eventual dissolution.

Garnering public support for agreements like the Agreed Framework that specifically deal with nuclear-proliferation issues is especially important given the political stakes involved. Particularly in the American context, these types of agreements often require policy makers to expend significant political capital to overcome opposition because they typically involve providing concessions to the other party (or parties) in exchange for the cessation of concerning proliferation activities. Policy makers thus have incentives to build public support so that, in spending their political capital, they can insulate the agreement from domestic political pushback and thus improve its durability.Footnote9

This paper seeks to consider how policy makers might engage the public on some of the most pressing and contentious proliferation issues. To do so, it presents and analyzes the results of an original survey experiment designed to test what types of messaging from elites, if any, impact US public attitudes toward proliferation issues. The online public-polling firm YouGov fielded the survey in January 2022, capturing responses from a nationally representative sample of 1,000 US respondents split into four treatment groups using a methodology that yielded a margin of error of 3.4 percent.Footnote10 The survey introduced all respondents to and asked their initial opinions of the Iran nuclear deal and the AUKUS nuclear-powered-submarine initiative. Surveying public opinion on these two distinct issues allowed consideration of whether public attitudes toward nuclear proliferation, including the potential effect of messaging on those attitudes, vary by context. Each treatment group then received a distinct set of arguments for and against each agreement, differentiated by types of thematic messaging. Finally, the survey again asked respondents their opinions about the proliferation issues to assess whether the arguments presented impacted their initial attitudes toward each.Footnote11

The findings demonstrate that elite messaging does indeed impact US public attitudes toward proliferation issues, but that those effects vary across different issues. Various types of messaging prompted changes in attitudes toward the Iran deal, while only messaging related to alliance considerations prompted changes in attitudes toward the AUKUS initiative—a counterintuitive finding to the extent that messaging had a greater effect on a more widely reported and well-known issue. The findings are mixed as to whether different types of messaging have distinct effects on Americans’ proliferation attitudes. Notably, the survey also shows that opposition to the Iran deal is particularly insensitive to the effects of messaging, and that messaging seems to sow greater confusion about the AUKUS initiative. These findings hold important implications for both elite proponents and opponents of nonproliferation agreements seeking to identify effective messaging strategies for engaging the public.

This paper has three parts. First, it expands on the research agenda by introducing and explaining the paper’s hypotheses and the survey design implemented to test them. Second, it presents the survey results, provides detailed analyses of each proliferation issue and treatment, and considers whether messaging impacted some respondents more than others. The paper concludes by discussing the policy implications of those findings and outlining areas for future research.

Examining public attitudes toward nuclear-proliferation issues

Does messaging impact public attitudes toward nuclear-proliferation issues? If so, what kind of messaging impacts those attitudes and how? Does the effect of that messaging vary across different proliferation issues?

Scholarship on foreign-policy cues, which argues the public takes cues from others in forming attitudes about foreign affairs,Footnote12 suggests messaging should impact public attitudes toward nuclear-weapons issues.Footnote13 Many scholars argue that elite cues are the primary shapers of public opinion—that is, that the public tends to adopt the attitudes and positions of trusted elites on foreign policy issues.Footnote14 Others instead contend that cues from social peers will have a greater effect than elite cues on attitudes, as members of the public tend to adopt positions that reflect their social group.Footnote15 This paper follows the elite-cues approach and aims to extend this scholarship to nuclear-proliferation issues. Not only do elites have informational advantages over the nonspecialist public given the complexities of proliferation issues, but the political capital associated with negotiating and implementing nonproliferation agreements also suggests elites have more interest in shaping public opinion of those agreements. The survey thus specifically tests the effect of elite messaging on public attitudes, which shapes the paper’s central and null hypotheses:

H1: Elite messaging impacts US public attitudes toward nuclear-proliferation issues.

H0: Elite messaging does not impact US public attitudes toward nuclear-proliferation issues.

To test these hypotheses, the survey began by introducing respondents to the Iran nuclear deal and AUKUS nuclear-powered-submarine initiative. The Iran deal is an agreement negotiated between Iran and the so-called P5 + 1—China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Germany—in 2015. The deal lifted some international economic sanctions against Iran in exchange for strict and verified limits on its nuclear activities, with the goal of preventing Iran from taking steps that could advance its capacity to develop nuclear weapons. The Trump administration withdrew from the agreement in 2018 and reimposed US sanctions on Iran. A year later, Iran resumed nuclear activities it had frozen under the deal.Footnote16 Since 2021, several states have made substantial efforts to bring Iran back into compliance and the United States back into the deal.

AUKUS is a trilateral security partnership among Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States intended to augment their collective defense capabilities in the Indo-Pacific region, particularly in light of China’s growing economic and military strength. Announced in September 2021, its most prominent effort is to help Australia acquire nuclear-powered submarines. The submarines’ nuclear reactors will be fueled with highly enriched uranium (HEU), material that could be used in nuclear weapons. The submarines will not, however, be armed with nuclear weapons. Nevertheless, the initiative raises concerns about the potential risks of non-nuclear-weapon states using nuclear materials for naval propulsion. In particular, since the material will necessarily operate outside of the international safeguards system, some fear the initiative could set a negative precedent that could allow other countries to use nuclear-powered-submarine programs as a cover to develop nuclear weapons.Footnote17

After reading these short introductions, respondents were asked their initial opinions about the two agreements. For each issue, they could indicate support or opposition or that they did not know their position. The survey then exposed respondents to messaging reflecting US elite arguments for and against both agreements. In presenting a set of pro and con arguments about both issues to each respondent, the survey design served to simulate the policy debates that characterize elite discourse on the issues, helping to add a real-world quality to the survey experiment. Respondents were then asked their opinions about the agreements again to determine if the messaging prompted any changes in their initial attitudes. This pre-survey/post-survey design proved useful because it offered “a closer look at treatment effect heterogeneity by allowing an analysis of how respondents change their opinions throughout an experiment,”Footnote18 without substantial concerns about demand effects.Footnote19

To disaggregate the potential effect of messaging on public attitudes, each treatment group received a different set of thematic arguments for and against the two agreements.Footnote20 Across the treatment groups, this procedure facilitated efforts to determine what kind of thematic messaging, if any, impacts public attitudes and to consider if any type of messaging is particularly impactful. Within each group, the procedure helped to determine whether the same messaging type impacted public opinion (and in the same direction) across contexts: while the specific arguments for each agreement inevitably differ, the common theme helped to reveal whether certain kinds of arguments consistently impact public attitudes.

The arguments included in the survey reflect existing policy debates surrounding each proliferation issue and are provided in Appendix 1.Footnote21 Subject-matter experts vetted the arguments to ensure they accurately captured these debates. Each argument falls into one of the following thematic categories:

Nature of the Agreement (Treatment Group 1): This messaging focuses on the intrinsic merits and demerits of the agreements.

Alliance Considerations (Treatment Group 2): This messaging focuses on how each agreement affects US alliances.

Security Implications (Treatment Group 3): This messaging focuses on how each agreement affects US security interests.

Trust (Treatment Group 4): This messaging focuses on the role of trust in each agreement, including the trustworthiness of Iran and Australia, respectively, as well as institutional mechanisms to enforce the agreements (for example, verification by the International Atomic Energy Agency).

In adopting message type as the independent variable, the survey follows the subset of elite-cue-taking literature that is primarily interested in the content of elite messages.Footnote22 It is distinct from much of the cue-taking literature, though, in that it did not attribute the arguments to any specific elite actor. This allowed closer consideration of the merits of the arguments themselves. Since messengers are typically defined by their party affiliation, the exclusion of messengers here also facilitated comparisons between the two proliferation issues, one of which has partisan connotations while the other seemingly does not.Footnote23 Future research could incorporate an additional independent variable to consider how the identity of a messenger may affect the impact of elite messaging on public attitudes toward proliferation issues.Footnote24

Scholarship focusing on the content of elite messages provides insight into how different messages may have different effects on public opinion. For instance, Stephen Herzog, Jonathon Baron, and Rebecca Davis Gibbons find that security and institution cues against the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons have stronger effects on US public support for the treaty than does a norms cue, although they do not find a statistically significant difference between the effect of the security and institution cues.Footnote25 Extrapolating from these insights with the goal of distinguishing between types of messaging specifically relevant to debates on proliferation issues leads to the paper’s second hypothesis:

H2: Different types of messaging will have distinct effects on US public attitudes toward nuclear-proliferation issues.

Further hypothesizing of how exactly each type of messaging might impact public attitudes toward specific proliferation issues (for example, how much or in which direction), though, is particularly difficult, especially as the survey takes two different kinds of proliferation issues as its primary focus. While the Iran nuclear deal aims to address concerns about a state taking steps that could advance its capacity to develop nuclear weapons, the AUKUS initiative raises concerns about the potential proliferation risks of non-nuclear-weapon states using nuclear materials for naval propulsion. In addition to these substantive concerns, the Iran deal involves a US adversary while AUKUS involves a US ally. Americans have also been relatively well exposed to the Iran deal compared with the much newer AUKUS partnership.

The distinctiveness of the issues suggests that public attitudes toward these issues will differ. Existing polling appears to support this assumption. For instance, since 2016, the Chicago Council on Global Affairs has found that, in aggregate, Americans generally support the Iran nuclear deal.Footnote26 However, an analysis of the disaggregated data reveals substantial partisan differences.Footnote27 Because it is a relatively new endeavor, polling on the AUKUS initiative is much less robust. The Chicago Council finds, though, that compared with support for the Iran deal, a larger majority of Americans support selling “arms and military equipment” to Australia, and with a much smaller partisan split.Footnote28

More uncertain is whether the effect of messaging on those attitudes will also differ, including whether messaging will impact attitudes toward one issue more than the other, which informs the paper’s final hypothesis:

H3: The effect of messaging on US public attitudes varies across different proliferation issues.

The hypotheses are summarized in . Two final notes about the survey’s research design merit consideration. First, in addition to its experimental utility, the survey helps to fill important gaps in the existing polling record. While a substantial amount of polling captures American attitudes toward the Iran deal, many of these polls focus primarily on assessing whether or not Americans support the deal.Footnote29 They do not provide as much insight into why the public supports or opposes the deal, and, more specifically, what arguments for or against the agreement impact those attitudes, as this survey does.Footnote30 Given the nascency of the partnership, this survey is also among the first to gather data on US public attitudes toward AUKUS.Footnote31 Additionally, in focusing on the fairly nuanced nonproliferation debate surrounding the partnership’s nuclear-powered-submarine initiative, it provides insight into whether and how the public thinks about particularly complex proliferation issues.

Second, it is important to consider timing in assessing the survey findings. At the time of the survey fielding in January 2022, parties to the Iran deal were in the midst of a monthslong series of negotiations to try to salvage the agreement after the United States’ withdrawal and Iran’s progressive violation of the agreement.Footnote32 And, after announcing the partnership in September 2021, the AUKUS partners were four months into the 18-month consultation period of determining the best way forward for delivering the submarine initiative.Footnote33 At the time of this writing, a return to the Iran deal appears increasingly unlikelyFootnote34 and the AUKUS partners have announced their plan to deliver the submarine initiative.Footnote35

Results and analysis

The survey began by asking respondents to rank the severity of five different nuclear threats to the United States. The results provide a useful characterization of how the public perceives the more general threat of proliferation compared with challenges posed by specific states. A plurality of respondents (48 percent) ranked “the spread of nuclear weapons and weapons technology to other states” as the least serious threat, placing it below the respective nuclear capabilities of China, Iran, North Korea, and Russia. This finding suggests that Americans tend to associate greater risk with specific actors than with nuclear weapons as such. This provides useful background for considering respondents’ attitudes toward the two specific proliferation issues considered here and, especially, the performance of H3.Footnote36

The Iran nuclear deal

presents the survey findings on the Iran deal. For each treatment group, the table reports whether respondents supported the agreement, opposed it, or said they did not know their position on it initially (pre-messaging) and after receiving arguments for and against the agreement (post-messaging).Footnote37 It also presents the difference between these pre-messaging and post-messaging responses (change). Asterisks denote whether the differences between the pre- and post-messaging means within each treatment group are statistically significant, according to a paired-samples t-test (two-sided).

Table 1. Hypotheses

Table 2. Attitudes toward the Iran nuclear deal

The findings demonstrate that all four treatments prompted statistically significant changes in public attitudes toward the Iran nuclear deal. Elite messaging therefore impacted those attitudes, supporting H1 and disproving the null hypothesis. However, an analysis of variance (ANOVA)—a commonly used statistical test—demonstrates there is no statistically significant difference between the post-messaging means of the four treatment groups. Put another way, there is no measurable variation in how the different types of messaging impacted public attitudes toward the deal. This finding provides evidence against H2.

All treatments prompted a decrease in support for the agreement by an average of 7 percentage points, while opposition and “don’t know” (DK) responses increased by an average of 3 and 4 percentage points, respectively. Since messaging had a greater and negative effect on support levels, these findings suggest that, across the full sample, support for the Iran deal was impacted by messaging more than opposition or DK responses were. A detailed evaluation of each treatment group, however, reveals a more nuanced picture.

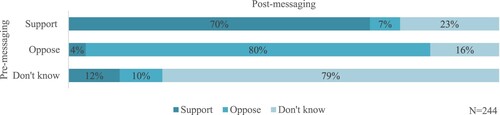

After respondents read arguments relating to the nature of the agreement, support for the Iran deal among Treatment Group 1 decreased by 8 percentage points, opposition increased by 2 percentage points, and DK responses increased by 6 percentage points, as presented in the first section of .Footnote38 presents a matrix that provides a more detailed illustration of how the subsample’s pre-messaging attitudes compare with its post-messaging attitudes. The figure demonstrates, for example, that, of those respondents who initially supported the Iran deal, 70 percent continued to support the deal after reading the arguments, while 7 percent now opposed the deal and 23 percent said they no longer knew their position. A collective 30 percent of those who initially supported the agreement therefore changed their minds after being presented with messaging about the nature of the deal. Meanwhile, 20 percent of those who initially opposed the deal changed their attitudes after reading the arguments, the majority of whom instead opted for DK responses (16 percent). And 22 percent of those who initially indicated DK adopted firmer positions—that is, support or opposition—once presented with the arguments, with a nearly even split of 12 percent supporting and 10 percent opposing the deal.

Figure 1. Pre-messaging and post-messaging attitudes toward the Iran deal—T1: nature of the agreement.

Note: Responses may not add to 100 percent, owing to rounding.

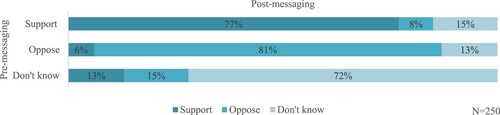

The second section of presents attitude changes among Treatment Group 2 after exposure to arguments about the Iran deal relating to alliance considerations. Support decreased by 4 percentage points, opposition increased by 5 percentage points, and DK responses decreased by 1 percentage point. provides a more detailed illustration that shows 23 percent of initial supporters changed their positions after reading the alliance arguments, most shifting to DK responses (15 percent). Fewer initial opponents changed their attitudes, with 19 percent adopting DK (13 percent) or support (6 percent) positions. The biggest change occurred among those who initially responded DK. Here, 28 percent adopted firmer positions, with nearly even proportions opting for support and opposition (13 and 15 percent, respectively).

Figure 2. Pre-messaging and post-messaging attitudes toward the Iran deal—T2: alliance considerations.

Note: Responses may not add to 100 percent, owing to rounding.

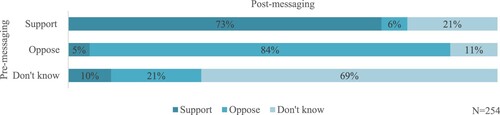

The third section of presents findings for Treatment Group 3, the subsample exposed to arguments relating to the security implications of the Iran deal. It shows that support decreased by 9 percentage points, opposition increased by 5 percentage points, and DK responses increased by 4 percentage points. presents the treatment group’s pre- and post-messaging matrix. It shows that 27 percent of initial supporters changed their attitudes toward the deal when exposed to security arguments, most adopting DK responses (21 percent). A combined 16 percent of initial opposers changed their attitudes, 5 percent opting to support the agreement and 11 percent opting for DK responses. And 31 percent of those who initially indicated DK changed their response, with more opposing (21 percent) than supporting (10 percent) the agreement.

Figure 3. Pre-messaging and post-messaging attitudes toward the Iran deal—T3: security implications.

Note: Responses may not add to 100 percent, owing to rounding.

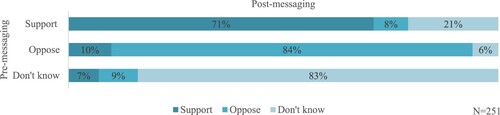

Finally, after respondents read arguments for and against the Iran deal that relate to trust, support among Treatment Group 4 decreased by 7 percentage points, opposition increased by 1 percentage point, and DK responses increased by 5 percentage points, as presented in the fourth section of . In comparing the pre- and post-messaging attitudes of each response group, demonstrates that 29 percent of initial supporters changed their attitudes toward the deal when presented with the trust arguments, most shifting to DK responses (21 percent). Fewer initial opponents and initial DK respondents changed their responses—16 percent each, with more initial opponents adopting support positions (10 percent) and initial DK respondents fairly evenly split between support and opposition (7 and 9 percent, respectively).

Figure 4. Pre-messaging and post-messaging attitudes toward the Iran deal—T4: trust.

Note: Responses may not add to 100 percent, owing to rounding.

Examining each treatment group thus illustrates in detail how specific types of elite messaging impacted Americans’ attitudes toward the Iran deal. The findings demonstrate that larger segments of each response group changed their attitudes toward the deal after being presented with any set of arguments than is captured by the collective data summarized in . Moreover, while the collective data suggest that support is impacted most by messaging (average support across the treatment groups changed more than average opposition or DK responses), the more detailed analyses demonstrate that this is the case only when respondents were presented with messaging related to the nature of the agreement and trust—types of messages that raise questions about the very fundamentals of the deal. DK responses are instead impacted most when respondents are presented with messaging related to alliance considerations and security implications, suggesting that messaging concerning the broader relevance and implications of the deal may have particular sway over those without firm positions.

Viewed differently, the detailed analyses reveal that opposition to the Iran deal was impacted least by messaging. Fewer initial opponents changed their attitudes after receiving any type of messaging about the agreement than those who initially supported or did not take a position on the deal,Footnote39 making opposition to the Iran deal the attitude most insensitive to messaging across the treatment groups. All types of messaging served to reinforce rather than sway that position, which appears to reflect the challenging task of building support for agreements that require the United States to negotiate and compromise with an adversary.Footnote40 Despite the insensitivity of the opposition attitude, however, it is important to highlight an additional consistency across all treatment groups: post-messaging support for the Iran deal remained higher than post-messaging opposition.Footnote41 This carries important implications for policy makers seeking to promote the agreement, as discussed below.

Among those who did change their attitudes across all the treatment groups, messaging did not tend to persuade initial supporters to oppose the deal but rather prompted them to question their firm position and adopt DK responses. Similarly, of the relatively smaller segment of initial opponents who were impacted by messaging, most adopted DK positions. Treatment Group 4, however, is a notable exception. Messaging related to trust persuaded more initial opponents to support the agreement, suggesting the relative strength of arguments concerning the Iran deal’s robust verification mechanisms.Footnote42 Respondents impacted by messaging who initially indicated DK tended to split nearly evenly between supporting and opposing the agreement, except in Treatment Group 3, where security messaging persuaded substantially more respondents to oppose the deal. This finding suggests that arguments about the limited scope of the Iran deal may be particularly impactful in shaping attitudes about the deal.Footnote43

Importantly, all of these attitude changes, or relative lack thereof, reflect how convincing each response group found the messaging, as assessed by additional survey questions that asked respondents to indicate whether they found each argument convincing or unconvincing and to what degree. Take, for example, findings from Treatment Group 3. As indicated above, a relatively large portion of initial supporters changed their attitudes toward the deal after reading the security arguments (27 percent). Even though a large majority of these initial supporters found the argument in favor of the agreement very or somewhat convincing (87 percent), a substantial majority also found the argument against it very or somewhat convincing (63 percent). That a majority found the “against” argument convincing helps to explain the relatively large post-messaging change. The relatively small change in initial opponents’ attitudes toward the Iran deal (16 percent) similarly appears to reflect the convincingness findings. Large majorities of this group found the “for” argument very or somewhat unconvincing (75 percent) and the “against” argument very or somewhat convincing (80 percent), shedding light on why most did not change their attitudes toward the deal. Finally, majorities of the DK response group found both arguments very or somewhat convincing, helping to explain why a relatively large portion adopted firmer positions on the Iran deal after reading the arguments (31 percent). More appeared to specifically shift to opposition (21 percent), since a larger majority found the “against” argument convincing (60 percent) than the “for” argument (52 percent). These convincingness findings as well as those from the other treatment groups are summarized in in Appendix 3.

The AUKUS nuclear-powered-submarine initiative

presents the survey’s findings on the AUKUS initiative. As in the case of the Iran-deal findings, the table reports respondents’ initial attitudes (pre-messaging), their attitudes after receiving the arguments for and against the agreement (post-messaging), and the difference between the two (change).Footnote44 Asterisks denote the statistical significance of the differences between pre- and post-messaging means within each treatment group according to a paired samples t-test (two-sided).

Table 3. Attitudes toward the AUKUS nuclear-powered-submarine initiative

The results demonstrate that only messaging related to alliance considerations (Treatment Group 2) prompted a significant change in public attitudes toward the AUKUS initiative. Since some type of elite messaging impacted those attitudes, this finding supports H1. It also provides some support for H2. Alliance messaging had a measurable effect and thus can be characterized as having a different effect than the other messaging types. And because one messaging type significantly impacted attitudes toward the AUKUS initiative, compared with all messaging types significantly impacting attitudes toward the Iran deal, these results also support H3: the effect of elite messaging on US public attitudes varies across different proliferation issues.

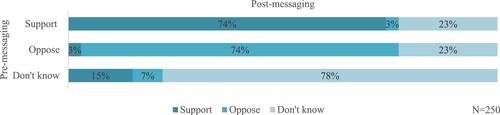

Comparing the findings from Treatment Group 2 across the two issues highlights further differences. While alliance messaging prompted a decrease of 4 percentage points in support for both agreements, it prompted a 5-percentage-point increase in opposition responses and a 1-percentage-point decrease in DK responses in the Iran case compared with no change in opposition and a 4-percentage-point increase in DK responses in the AUKUS case. presents a more detailed illustration of the attitude changes toward the AUKUS initiative. It shows that, while 74 percent of both initial supporters and initial opponents did not change their positions after reading the alliance arguments for and against the initiative, a collective 26 percent in each group did, most adopting DK responses (23 percent). Meanwhile, fewer respondents who initially gave DK responses changed their position: 22 percent adopted firmer positions when presented with the alliance arguments, with more opting to support the initiative (15 percent). Here, then, DK responses are less sensitive to messaging than support or opposition attitudes.

Figure 5. Pre-messaging and post-messaging attitudes toward the AUKUS initiative—T2: alliance considerations.

Note: Responses may not add to 100 percent, owing to rounding.

These findings stand in contrast to the Treatment Group 2 findings for the Iran deal, which, as shown in , indicate that opposition attitudes are the most insensitive and DK attitudes are the most sensitive to messaging. The more detailed examinations of the subsample’s attitudes captured by the pre- and post-messaging matrices thus only reinforce the finding that elite messaging—and, specifically, alliance messaging—has a distinct effect on attitudes toward different proliferation issues.

Attitude changes among initial DK respondents and initial opponents in the AUKUS case appear to reflect how convincing these response groups found the alliance arguments about the submarine initiative. Majorities of initial DK respondents found arguments both for and against the initiative very or somewhat unconvincing (60 and 63 percent, respectively), which helps to explain why relatively few changed their attitudes toward the initiative. And even though a large majority of initial opponents found the “for” argument very or somewhat unconvincing (81 percent), a majority also found the “against” argument very or somewhat unconvincing (52 percent). That a majority found the “against” argument unconvincing helps to explain why a relatively large portion of initial opponents changed their position and, since many also found the “for” argument unconvincing, why most of these attitude changers specifically adopted a DK response.

Changes in attitudes among initial supporters, however, do not similarly appear to reflect how convincing they found each argument. A majority found the “for” argument very or somewhat convincing (83 percent) and the “against” argument very or somewhat unconvincing (67 percent), which would suggest that support levels should not have changed all that much. A relatively large portion of initial supporters did, however, change their attitudes toward the AUKUS initiative, most opting for DK responses. This could suggest that, rather than swaying their position, the arguments made some respondents think that they did not fully understand the initiative.Footnote45

As indicated in , no other treatment prompted significant changes in public attitudes toward the AUKUS initiative. The high levels of both pre- and post-messaging DK responses across these groups, as well as responses to an additional survey question that indicated that a majority of respondents do not follow the initiative “at all closely” (51 percent), suggest that a lack of familiarity with—and perhaps understanding of—the issue could have precluded respondents from critically engaging with the messaging. This lack of engagement, in turn, could help to explain why these messaging types did not impact their attitudes.

Nonetheless, descriptively assessing the pre- and post-messaging responses from these groups provides greater insight into how Americans are responding to the new AUKUS partnership and its particularly prominent nuclear-powered-submarine initiative. These assessments suggest that opposition to the initiative may be particularly sensitive and support and DK responses more insensitive to messaging. More initial opponents selected different responses after reading arguments relating to the nature of the agreement, security, and trust than did initial supporters or DK respondents. This stands in contrast to the Iran-deal findings and may signify a greater receptiveness to the submarine initiative, perhaps because of its novelty or the involvement of a US ally rather than an adversary. Importantly, though, attitudes toward the AUKUS initiative among these groups did not necessarily reflect how convincing respondents found the arguments about the initiative, as indicated in in Appendix 3. This apparent disparity merits further examination, as it may, for example, help to explain why these messaging types did not have a significant effect on public attitudes.Footnote46

Nevertheless, of most relevance to this paper’s research agenda, the AUKUS findings demonstrate that only one type of messaging, alliance considerations, significantly impacted public attitudes toward the partnership’s nuclear-submarine initiative. And this messaging specifically prompted greater apparent confusion about the initiative. DK responses were impacted least by messaging, and post-messaging changes among initial supporters and opponents primarily resulted in more DK responses. This makes some intuitive sense given the nascency of the AUKUS partnership and its submarine initiative, as well as the complexities of the proliferation arguments surrounding the initiative. Notably, of those initial DK respondents in Treatment Group 2 who did adopt a firmer position after reading the arguments, more supported the initiative, perhaps indicating greater prioritization of Indo-Pacific than European regional issues,Footnote47 reflective of the Biden administration’s own priorities.Footnote48

Attitude changers

Analysis presented thus far demonstrates that elite messaging impacted public attitudes toward both the Iran nuclear deal and AUKUS nuclear-powered-submarine initiative, the former across all messaging types and the latter only with regard to alliance considerations. But who exactly was impacted by this messaging—that is, which respondents changed their minds? And did this vary by issue?

An average 24 percent of respondents across the full survey sample changed their attitudes toward the Iran deal after reading arguments about it, the full sample being relevant because all four treatments prompted statistically significant changes in attitudes toward the deal. Similarly, 24 percent of Treatment Group 2 changed their attitudes toward the AUKUS initiative after reading the alliance arguments, the subsample being relevant because only this treatment prompted statistically significant changes in attitudes toward the AUKUS initiative. , however, demonstrates that these figures vary according to five different factors: age, education, gender, party, and political interest.Footnote49

Table 4. Changed attitudes by age, education, gender, party, and political interest

The results presented by age reveal that more Generation Z respondents (27 percent) changed their opinion of the Iran deal compared with the full sample average of 24 percent, while fewer Silent Generation respondents (19 percent) changed their opinion compared with the average. Put another way, the youngest respondents were impacted most by elite messaging about the Iran deal and the oldest respondents were impacted least. This finding perhaps reflects differences in levels of exposure to the issue, considering, for example, that most members of Generation Z were not yet of voting age when the Iran deal was finalized in 2015. Importantly, the finding does not translate to the AUKUS issue, where the percentage of respondents who changed their attitudes varies substantially across the age groups, both below and above the Treatment Group 2 average.

Consistently across both issues, the percentage of respondents who changed their attitudes decreases as education levels increase. A notably high portion of respondents without a high school degree were impacted by messaging related to the AUKUS initiative (62 percent) and a notably low portion of respondents with a postgraduate degree were impacted by messaging related to the Iran deal (15 percent), compared with the 24 percent averages of both Treatment Group 2 and the full sample. The higher the education level, then, the smaller the effect of messaging. Changes according to gender also diverge from the averages across both issues. More women changed their attitudes than men, indicating that women were consistently impacted more by messaging. This finding merits closer consideration, especially as it relates to literature on gender gaps in public attitudes toward foreign policy.Footnote50

In terms of party affiliation, the percentage of Democrats who changed their position remains fairly close to the averages for the full sample and Treatment Group 2—slightly under in the Iran case (23 percent) and slightly over in the AUKUS case (25 percent). Meanwhile, fewer Republicans changed their attitudes toward the Iran deal (20 percent) and far more changed their attitudes toward the AUKUS initiative (36 percent), compared with the averages. That more Republicans remained firm in their positions on the Iran deal may speak to the polarization surrounding the agreement, especially following President Donald Trump’s comments in 2018 that implicitly blamed former president Barack Obama for negotiating “one of the worst and most one-sided transactions the United States has ever entered into.”Footnote51 The reverse trend, however, occurred among independents, as more were impacted by messaging on the Iran deal (28 percent) than on the AUKUS initiative (16 percent).

The final factor represents a metric of respondents’ political interest.Footnote52 Those who self-identified as most politically interested changed their attitudes toward both issues less than average (17 percent), a seemingly intuitive finding, as it is reasonable to expect that those who follow government and public-affairs issues closely will have stronger and firmer opinions about those issues. Among the other interest levels, somewhat counterintuitive findings emerge. For instance, larger portions of those who self-identified as politically interested “some of the time” changed their attitudes toward both issues than those who self-identified as “hardly at all” interested. This is especially stark for the AUKUS initiative: 33 percent of the “somewhat interested” group changed their attitudes while only 12 percent of the “uninterested” group did. Following the above logic, it seems counterintuitive that less politically interested respondents would have firmer opinions about the issues, perhaps suggesting a relative lack of receptiveness to new information or a sense of apathy to the extent that these respondents remained firm in their DK responses.

Characterizing attitude changers according to age, education, gender, party, and political interest thus reveals interesting patterns that provide greater insight into which types of respondents are particularly affected or unaffected by messaging and how this varies or is consistent across proliferation issues. Importantly, though, while the analysis here considered each of them individually, these factors are inevitably linked and are consequently important to consider in relation to each other.

Conclusions and implications

The survey findings provide clear support for both H1 and H3: elite messaging impacts US public attitudes toward nuclear-proliferation issues, but those effects vary across different issues. All types of messaging impacted attitudes toward the Iran nuclear deal, but only messaging related to alliance considerations impacted attitudes toward the AUKUS nuclear-powered-submarine initiative. Meanwhile, the survey results provide mixed evidence on H2, suggesting that whether different types of messaging have distinct effects on US public attitudes toward proliferation issues depends on the issue. Alliance messaging can be characterized as having a distinct effect on attitudes toward the AUKUS initiative relative to the other messaging types. Meanwhile, different messaging types did not have distinct effects on attitudes toward the Iran deal.Footnote53 These findings, and especially those revealed by the detailed analyses of each treatment group, hold potential implications for policy makers seeking to identify effective messaging strategies for engaging the public on these and other proliferation issues.

The Iran deal findings demonstrate that, even though support remained higher after respondents were exposed to all types of messaging, opposition to the deal is particularly insensitive to elite messaging. This suggests that critics of the deal may have notable success in fostering that opposition through messaging. It also suggests that policy makers seeking to garner support for the deal should prioritize countering negative messaging and tailoring positive messaging toward those without a firm position rather than focus on changing the minds of those who oppose the deal. As no particular type of messaging had a distinct effect on attitudes toward the deal, both proponents and opponents could benefit from drawing on an array of arguments in making their case. Based on the patterns of attitude changers, they might find particular success in engaging younger, less-educated, female, and independent respondents. In practice, though, the partisanship surrounding the Iran deal in the United States would likely make it difficult to significantly affect public attitudes.Footnote54 Moreover, at the time of this writing, prospects for a return to the deal look grim, so elite proponents in particular may find little value in expending political capital to promote the deal. But if a new deal to limit Iran’s nuclear activities is reached, these findings may help inform how policy makers engage the public.Footnote55 The Iran-deal findings may also provide insight into the nature of Americans’ attitudes toward proliferation issues involving other US adversaries and concerns about a state potentially seeking to acquire nuclear weapons, compared with more complex proliferation challenges, especially those posed by US allies, as in the AUKUS case.

The AUKUS findings demonstrate that only messaging related to alliance considerations had a significant effect on public attitudes toward the nuclear-powered-submarine initiative. But, rather than persuading respondents to adopt a firm position, this messaging prompted greater confusion, encouraging more DK responses. While messaging related to the nature of the agreement, security, and trust did not significantly impact public attitudes, descriptive analyses of these treatment groups similarly suggest that the public does not know much about the AUKUS partnership and its submarine initiative and that elite messaging about the initiative seems to do more to confuse than persuade. Collectively, these findings suggest that, regardless of their position, policy makers should undertake greater efforts to educate the public on the submarine initiative and, based on the findings of which demographic groups changed their attitudes, target an array of audiences in doing so. These efforts, which may gain particular traction if focused on alliance considerations, should be as straightforward as possible to make the complexities of and proliferation concerns surrounding naval nuclear propulsion by a non-nuclear-weapon state more accessible to the nonspecialist public.

A final point of comparison across the two issues presents perhaps the most broadly policy-relevant finding: messaging had a greater effect on an issue with which the public is more familiar.Footnote56 More accurately, more types of messaging impacted attitudes toward a more familiar issue. Intuitively, one might expect that, because the Iran nuclear deal is a much more established and well-known issue and the public has been more exposed to it, positions toward the deal would be more fixed and any type of messaging would therefore have a limited effect. By contrast, one might expect messaging to have a more substantial effect on attitudes toward the AUKUS initiative because the public presumably does not know much or have firm conceptions about this relatively new issue. That the survey results demonstrate the opposite could hold important implications for policy makers in addressing broader sets of proliferation issues—perhaps including a potential US–Saudi agreement for peaceful nuclear cooperation, a prospect that has already raised proliferation concerns.Footnote57 This finding may indicate not only that public attitudes toward proliferation issues may not be as fixed as stagnant elite debates suggest but also that greater familiarity with an issue can help the public engage more deeply with that issue. Such familiarity appears to encourage the public to think more critically about the issue rather than default to apathy fueled by a lack of expertise or understanding. Policy makers could leverage that engagement to garner support for their position on the issue, which, in turn, could give them greater political cover and maneuverability—an especially useful asset if elite positions on the issue are particularly entrenched. Additionally, this finding indicates that policy makers should be thoughtful in developing messaging and engagement strategies that take into account the public’s familiarity with various proliferation issues.

Future research could expand on these findings. While this experimental survey tested how distinct types of messaging impact public attitudes, it is difficult to differentiate messaging types in the real world. It is therefore possible that the effects of the different messaging types could compound one another, potentially prompting even greater segments of the population to shift their attitudes. Additionally, the survey artificially presented respondents with arguments both for and against the proliferation agreements and did not attribute the messaging to a specific elite actor. In reality, the public is unlikely to receive such two-sided messaging and may prioritize messages from particular elites, potentially prompting more biased responses. Finally, the survey focused on how Americans engage with proliferation issues, which may differ from how other publics engage, especially given that real-world policy debates surrounding these issues differ across political contexts. These considerations are worth further exploration; they not only would provide additional insight into the nature of public attitudes toward nuclear proliferation issues but also would contribute to broader efforts to ensure experimental survey research remains reflective of real-world contexts.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to James Acton, Natasha Bajema, Eric Brewer, Toby Dalton, Sarah Higdon, Daniel Horner, Doreen Horschig, Alexander Marsolais, Nick Miller, Ankit Panda, Todd Sechser, participants at the International Studies Association 2023 Annual Convention, and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback and comments on the survey and paper.

The author ran the survey and drafted an early version of this manuscript while a Stanton Foundation Nuclear Security Pre-Doctoral Fellow during the 2021–22 academic year.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jamie Kwong

Jamie Kwong is a fellow in the Nuclear Policy Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Her research focuses on public opinion on nuclear-weapons issues; challenges that climate change poses to nuclear weapons; and multilateral regimes, including the P5 Process, the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, and the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. She completed her PhD in War Studies at King’s College London, where she studied as a Marshall Scholar. Her dissertation examined US public opinion of North Korea’s nuclear-weapons program.

Notes

1 US Department of State, “Secretary Antony J. Blinken’s Remarks to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference,” August 1, 2022, <https://www.state.gov/secretary-antony-j-blinkens-remarks-to-the-nuclear-non-proliferation-treaty-review-conference/>.

2 Scott D. Sagan, “Why Do States Build Nuclear Weapons? Three Models in Search of a Bomb,” International Security, Vol. 21, No. 3 (1996), pp. 54–86, <https://www.jstor.org/stable/2539273>; Vipin Narang, Seeking the Bomb: Strategies of Nuclear Proliferation (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2022); Rebecca Davis Gibbons and Stephen Herzog, “Durable Institution under Fire? The NPT Confronts Emerging Multipolarity,” Contemporary Security Policy, Vol. 43, No. 1 (2021), pp. 50–79, <https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2021.1998294>.

3 Scott D. Sagan and Benjamin A. Valentino, “Revisiting Hiroshima in Iran: What Americans Really Think about Using Nuclear Weapons and Killing Noncombatants,” International Security, Vol. 42, No. 1 (2017), pp. 41-79, <https://doi.org/10.1162/ISEC_a_00284>.

4 As used here, a message impacts public attitudes if it prompts a change in attitudes toward a proliferation issue. The public can find a message convincing without it impacting attitudes.

5 By focusing on US attitudes toward outward-facing proliferation issues, this paper also helps supplement scholarship that examines how domestic audiences might perceive efforts by their own government to acquire nuclear weapons. See, for example, Lauren Sukin, “Credible Nuclear Security Commitments Can Backfire: Explaining Domestic Support for Nuclear Weapons Acquisition in South Korea,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 64, No. 6 (2020), pp. 1011–42, <https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002719888689>; Toby Dalton, Karl Friedhoff, and Lami Kim, “Thinking Nuclear: South Korean Attitudes on Nuclear Weapons,” Chicago Council on Global Affairs, February 2022, <https://globalaffairs.org/research/public-opinion-survey/thinking-nuclear-south-korean-attitudes-nuclear-weapons>.

6 Benjamin I. Page and Robert Y. Shapiro, The Rational Public: Fifty Years of Trends in Americans’ Policy Preferences (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992); Ole R. Holsti, Public Opinion and American Foreign Policy, 2nd ed. (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2004); Matthew A. Baum and Philip B.K. Potter, “The Relationships Between Mass Media, Public Opinion, and Foreign Policy: Toward a Theoretical Synthesis,” Annual Review of Political Science, Vol. 11, No. 1, pp. 39–65, <https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.060406.214132>.

7 Matthew A. Baum and Philip B.K. Potter, War and Democratic Constraint: How the Public Influences Foreign Policy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015); Michal Onderco, Michal Smetana, Sico van der Meer, and Tom W. Etienne, “When Do the Dutch Want to Join the Nuclear Ban Treaty? Findings of a Public Opinion Survey in the Netherlands,” Nonproliferation Review, Vol. 28, Nos. 1–3 (2021), pp. 149–63, <https://doi.org/10.1080/10736700.2021.1978156>; Michael Tomz, Jessica L.P. Weeks, and Keren Yarhi-Milo, “Public Opinion and Decisions about Military Force in Democracies,” International Organization, Vol. 74, No. 1 (2020), pp. 119–43, <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818319000341>.

8 Joel S. Wit, Daniel B. Poneman, and Robert L. Gallucci, Going Critical: The First North Korean Nuclear Crisis (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2004), pp. 334–35, 377.

9 Jamie Kwong, “The Public and Proliferation: U.S. Public Opinion of North Korea’s Nuclear Weapons Program,” PhD diss., King’s College London, 2023, p. 244, <https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/en/studentTheses/the-public-and-proliferation>; Suzanne Maloney, “Deception and the Iran Deal: Did the Obama administration Mislead America, or Did the Rhodes Profile?” Brookings, May 11, 2016, <https://www.brookings.edu/blog/markaz/2016/05/11/deception-and-the-iran-deal-did-the-obama-administration-mislead-america-or-did-the-rhodes-profile/>.

10 See Appendix 4 for an extended discussion of the survey methodology.

11 See Appendix 1 for the full survey script.

12 For a literature review of the scholarship on cue taking, see Joshua D. Kertzer and Thomas Zeitzoff, “A Bottom-up Theory of Public Opinion about Foreign Policy,” American Journal of Political Science, Vol. 61, No. 3 (2017), pp. 544–45, https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12314>.

13 Stephen Herzog, Jonathon Baron, and Rebecca Davis Gibbons, “Antinormative Messaging, Group Cues, and the Nuclear Ban Treaty,” Journal of Politics, Vol. 84, No. 1 (2022), pp. 591–96, <https://doi.org/10.1086/714924>.

14 Robert M. Entman, Projections of Power: Framing News, Public Opinion, and US Foreign Policy (London: University of Chicago Press, 2004); Alexandra Guisinger and Elizabeth N. Saunders, “Mapping the Boundaries of Elite Cues: How Elites Shape Mass Opinion across International Issues,” International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 61, No. 2 (2017), pp. 425–41, <https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqx022>.

15 Kertzer and Zeitzoff, “A Bottom-up Theory of Public Opinion about Foreign Policy.”

16 Substantial efforts were made in the survey text to clarify the sequence of these events, including by noting that Iran had been adhering to the terms of the agreement at the time of the US withdrawal. Nevertheless, respondents may have had pre-existing misconceptions about this sequence, especially given the political nature of the issue, with potential implications for how they viewed the deal in the survey experiment.

17 James Acton, “Why the AUKUS Submarine Deal Is Bad for Nonproliferation—and What to Do about It,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, September 21, 2021, <https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/09/21/why-aukus-submarine-deal-is-bad-for-nonproliferation-and-what-to-do-about-it-pub-85399>.

18 Scott Clifford, Geoffrey Sheagley, and Spencer Piston, “Increasing Precision without Altering Treatment Effects: Repeated Measures Designs in Survey Experiments,” American Political Science Review, Vol. 115, No. 3 (2021), p. 1061, <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000241>.

19 Jonathan Mummolo and Erik Peterson, “Demand Effects in Survey Experiments: An Empirical Assessment,” American Political Science Review, Vol. 113, No. 2 (2019), pp. 517–29, <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055418000837>.

20 YouGov randomized which argument respondents received first, to avoid priming or otherwise influencing their responses.

21 All efforts were made to avoid confounding arguments across the messaging types.

22 Herzog et al., “Antinormative Messaging, Group Cues, and the Nuclear Ban Treaty;” Jonathan Baron, Rebecca Davis Gibbons, and Stephen Herzog, “Japanese Public Opinion, Political Persuasion, and the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons,” Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament, Vol 3, No. 2 (2020), pp. 209–309, <https://doi.org/10.1080/25751654.2020.1834961>; Jonathan Baron and Stephen Herzog, “Public Opinion on Nuclear Energy and Nuclear Weapons: The Attitudinal Nexus in the United States,” Energy Research & Social Science, Vol. 68 (2020), pp. 1–11, <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101567>.

23 Whereas the Iran nuclear deal is widely recognized as a polarizing issue because the negotiation of the deal is so closely associated with the Obama administration and the US withdrawal from the deal with the Trump administration, the AUKUS nuclear-submarine initiative did not appear to be as polarizing at the time of the survey fielding or of this writing.

24 Guisinger and Saunders, “Mapping the Boundaries of Elite Cues.”

25 The authors’ security cue indicates that the US government opposes the treaty because it aims to eliminate nuclear weapons that are used to protect against other nuclear powers. Their institution cue indicates that the government opposes the treaty because it is a weak international institution that lacks enforcement and verification. The norms cue indicates that the government opposes the treaty because it could subvert the norms of the NPT. Herzog et al., “Antinormative Messaging, Group Cues, and the Nuclear Ban Treaty,” pp. 592, 594.

26 Aggregate support levels in Chicago Council polling have ranged from a peak of 66 percent in 2018 to a low of 57 percent in 2021. Notably, additional polling shows greater variability in support levels, with question phrasing seeming to play a substantial role in priming respondents’ attitudes. Chicago Council on Global Affairs, “2021 Chicago Council Survey: U.S. Public Topline Report,” August 9, 2021, p. 27, <https://globalaffairs.org/research/public-opinion-survey/2021-chicago-council-survey> (hereafter “2021 Topline Report”); “Iran,” PollingReport.com, n.d., <https://www.pollingreport.com/iran.htm>.

27 Chicago Council on Global Affairs, “2021 Topline Report,” p. 27.

28 An aggregate 73 percent supported these sales in 2021. Chicago Council on Global Affairs, “2021 Topline Report,” p. 16.

29 See, for example, Dina Smeltz, Ivo H. Daalder, Karl Friedhoff, Craig Kafura, and Emily Sullivan, “2021 Chicago Council Survey,” Chicago Council on Global Affairs, October 7, 2021, <https://globalaffairs.org/research/public-opinion-survey/2021-chicago-council-survey>.

30 There are a few important exceptions to this trend. In particular, the Program for Public Consultation at the University of Maryland conducted surveys in 2015—upon the deal’s conclusion and Congress’s review—and in 2017—amid the Trump administration’s consideration of withdrawal—that assessed how convincing respondents found arguments for and against the deal. While helpful references in designing the survey presented here, these surveys go into far more technical detail about the deal than is replicable or useful for the purposes of this paper. Additionally, in presenting arguments for and against the deal, they combine a number of types of arguments (for example, trust and alliance considerations), making it difficult to differentiate the effect of specific types of messaging on public attitudes toward the deal. Nancy Gallagher and Steven Kull, “Assessing the Iran Deal,” Program for Public Consultation, School of Public Policy, University of Maryland, September 2015, <https://cissm.umd.edu/sites/default/files/2019-10/Assessing_the_Iran_Deal_Quaire.pdf>; Steven Kull and Clay Ramsay, “U.S. Role in the World: Abbreviated Questionnaire—Iran Nuclear Deal,” Program for Public Consultation, School of Public Policy, University of Maryland, January 2017, <https://cissm.umd.edu/sites/default/files/2019-07/US_Role_in_World_Quaire-IRAN.pdf>.

31 See also Association of Marshall Scholars, “2021 US National Public Opinion Survey: Global Strategic Partnerships and Education Diplomacy,” Association of Marshall Scholars and Emerson College Polling, October 5, 2021, <https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5e5d88060457825545de8ab1/t/615ca9d4395b2c7d98d72558/1633462744165/AMS_ECP+National+Poll+2021.pdf >.

32 Kelsey Davenport, “Timeline of Nuclear Diplomacy with Iran, 1967–2023” Arms Control Association, last reviewed January 2023, <https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/Timeline-of-Nuclear-Diplomacy-With-Iran>.

33 White House, “Remarks by President Biden, Prime Minister Morrison of Australia, and Prime Minister Johnson of the United Kingdom Announcing the Creation of AUKUS,” September 15, 2021, <https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2021/09/15/remarks-by-president-biden-prime-minister-morrison-of-australia-and-prime-minister-johnson-of-the-united-kingdom-announcing-the-creation-of-aukus/>.

34 Nadeen Ebrahim, “Iran’s President Defends Uranium Enrichment after Europeans ‘Trampled on their Commitments,’” CNN, September 24, 2023, <https://edition.cnn.com/2023/09/24/middleeast/iran-raisi-fareed-zakaria-interview-intl/index.html>.

35 White House, “Joint Leaders Statement on AUKUS,” March 13, 2023, <https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/03/13/joint-leaders-statement-on-aukus-2/>.

36 The survey also asked respondents about their attitudes toward and awareness of the NPT—often referred to as the “cornerstone of the nonproliferation regime”—to similarly help contextualize the public’s understanding of nonproliferation issues. The results show that the public generally has little knowledge or awareness of the NPT, supporting the notion that the public thinks about proliferation issues as distinct from rather than related to this foundational treaty.

37 Table 2 presents the pre- and post-messaging responses of each treatment group subsample. Table A1 in Appendix 2 presents responses by age, education, gender, party, and political interest across the full survey sample.

38 All arguments are provided in Appendix 1 as part of the survey script.

39 A slight exception here is Treatment Group 4, where an equal proportion of initial DK respondents and initial opposers changed their attitudes.

40 For example, the Clinton administration struggled to build domestic support for the 1994 Agreed Framework with North Korea. Wit et al., Going Critical, pp. 334–35, 377.

41 Post-messaging support responses were also higher than post-messaging DK responses in Treatment Groups 2 and 3, while post-messaging DK responses were higher than post-messaging support responses in Treatment Group 1 and equal in Treatment Group 4.

42 The “for” version of the trust argument reads, “The Iran Nuclear Deal is not based on trust. It includes robust verification measures that allow international inspectors unprecedented access to monitor Iran’s nuclear program to determine whether Iran is living up to its responsibilities. These inspectors confirmed that Iran was complying with the deal when the United States withdrew from the agreement in 2018.”

43 The “against” version of the security argument reads, “The Iran Nuclear Deal does not address all of Iran’s dangerous activities, including its ballistic missile program and its support for terrorism. Iran therefore will continue to pose a serious threat to US national security.”

44 Responses here are reported for each treatment group subsample. Table A2 in Appendix 2 reports responses by age, education, gender, party, and political interest across the full survey sample.

45 After indicating their post-messaging attitudes, respondents were asked to explain their position. Responses to this open-ended question from initial supporters in Treatment Group 2 who changed their responses to DK provide some evidence to support this possibility. One such respondent, for example, stated, “I am very unsure about this [proliferation issue]. Need more information.” Another respondent indicated they would “need to read up on the situation more.”

46 These results will be considered in greater detail in future research efforts.

47 The “for” version of the alliance argument reads, “Some U.S. allies and partners in the Indo-Pacific support the AUKUS submarine initiative. Taiwan, for example, welcomes the AUKUS partners’ efforts to develop more advanced capabilities to defend the region.” The “against” version of the alliance argument reads, “France and many of America’s European allies oppose the AUKUS submarine initiative. In joining AUKUS, Australia cancelled its previous arrangement to buy diesel-powered submarines from France. France called this a ‘stab in the back’ and the European Union said ‘[o]ne of our member states has been treated in a way that is not acceptable.’”

48 US Department of Defense, “2022 National Defense Strategy of The United States of America,” October 2022, <https://media.defense.gov/2022/Oct/27/2003103845/-1/-1/1/2022-NATIONAL-DEFENSE-STRATEGY-NPR-MDR.PDF>.

49 The table reports findings where there is a statistically significant difference between pre- and post-messaging means. Since all four treatments prompted significant changes in attitudes toward the Iran deal, the Iran data reflect the full survey sample. Since only one treatment prompted significant changes in attitudes toward the AUKUS submarine initiative, the AUKUS data reflect the Treatment Group 2 subsample. The table shows the percentage of respondents who changed their attitudes according to each of the five factors. The tables in Appendix 2 show respondents’ pre- and post-messaging attitudes according to each factor.

50 See, for example, Miroslav Nincic and Donna J. Nincic, “Race, Gender, and War,” Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 39, No. 5 (2002), pp. 547–68, <https://www.jstor.org/stable/1555342>.

51 White House, “President Donald J. Trump Is Ending United States Participation in an Unacceptable Iran Deal,” May 8, 2018, <https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefings-statements/president-donald-j-trump-ending-united-states-participation-unacceptable-iran-deal/>.

52 YouGov gauges political interest levels by asking, “Some people seem to follow what’s going on in government and public affairs most of the time, whether there’s an election going on or not. Others aren’t that interested. Would you say you follow what’s going on in government and public affairs: most of the time, some of the time, only now and then, or hardly at all?”

53 As discussed above, the treatments all prompted statistically significant changes in public attitudes toward the deal, but their individual effects were not statistically distinguishable.

54 See Table A1 in Appendix 2 for a breakdown of responses by party.

55 Patrick Wintour, “UK, France and Germany Refuse to Lift Sanctions on Iran under Nuclear Deal,” The Guardian, September 14, 2023, <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/sep/14/uk-france-and-germany-refuse-to-lift-sanctions-on-iran-under-nuclear-deal>.

56 A combined 29 percent of respondents said that they follow the Iran deal “very” or “fairly” closely while only 19 percent said they follow the AUKUS initiative as closely. Even more illustrative of the public’s relative lack of familiarity with the AUKUS issue, a majority 51 percent noted they do not follow the initiative “at all closely,” whereas only 37 percent indicated the same for the Iran deal.

57 Jane Nakano, “The Saudi Request for U.S. Nuclear Cooperation and Its Geopolitical Quandaries,” Center for Strategic & International Studies, September 7, 2023, <https://www.csis.org/analysis/saudi-request-us-nuclear-cooperation-and-its-geopolitical-quandaries>.

1 YouGov, “Nuclear Proliferation Survey Experiment,” codebook provided to author, January 25, 2022.

2 YouGov, “About our panel,” n.d., <https://today.yougov.com/about/panel>.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Survey script

Background

| 1. | [All] Please rank the following nuclear threats to the United States in order of their severity with (1) being the most serious and (5) being the least serious.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. | [All] Do you support or oppose the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT)?

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3. | [All] How closely have you followed developments related to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT)?

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4. | [All] As far as you know, is the United States a member of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT)?

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Iran nuclear deal

[All] The Iran Nuclear Deal is an agreement negotiated between Iran and China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Germany (P5 + 1) in 2015. The deal lifts some international economic sanctions against Iran in exchange for strict and verified limits on its nuclear program. The United States withdrew from the agreement in 2018 and re-imposed US sanctions on Iran. At the time of the US withdrawal, international inspectors had verified Iran was complying with its obligations under the deal. Since 2019, Iran has violated the deal in increasingly serious ways. Negotiations are currently underway to try to bring Iran back into compliance and for the United States to re-join the deal.

| 5. | [All] Do you support or oppose the Iran Nuclear Deal?

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6. | [All] How closely have you followed this issue?

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7. | [All] As far as you know, is Iran a member of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT)?

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[T1: Nature of Agreement] The Iran Nuclear Deal is a ground-breaking agreement. It significantly increases the time it would take Iran to produce the materials needed to build a nuclear weapon. It also includes a robust verification regime and an unprecedented procedure to reimpose United Nations sanctions against Iran if it does not live up to its responsibilities.

[T2: Allies] The United States’ European allies support the Iran Nuclear Deal. They argue the agreement makes the world a safer place and have remained active participants in promoting and preserving the deal.

[T3: Security] The Iran Nuclear Deal advances U.S. national security interests. It prevents a long-standing U.S. adversary from developing nuclear weapons and helps to stop the spread of nuclear weapons in the Middle East.

[T4: Trust] The Iran Nuclear Deal is not based on trust. It includes robust verification measures that allow international inspectors unprecedented access to monitor Iran’s nuclear program to determine whether Iran is living up to its responsibilities. These inspectors confirmed that Iran was complying with the deal when the United States withdrew from the agreement in 2018.

| 8. | [Treatment Groups] How convincing do you find this argument?

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[T1: Nature of Agreement] Most restrictions on Iran’s nuclear program expire after 10–15 years. The Iran Nuclear Deal therefore delays rather than completely prevents Iran from being able to produce the materials needed to build a nuclear weapon. Moreover, because the deal lifts some international sanctions, Iran will be in a stronger position to develop nuclear weapons as the restrictions on its nuclear programs are phased out.

[T2: Allies] Israel, an important U.S. partner in the Middle East, opposes the deal. It argues that the deal’s restrictions are too weak and that the lifting of sanctions will leave Iran with more resources to act aggressively in the region.

[T3: Security] The Iran Nuclear Deal does not address all of Iran’s dangerous activities, including its ballistic missile program and its support for terrorism. Iran therefore will continue to pose a serious threat to U.S. national security.

[T4: Trust] We cannot trust Iran to adhere to the Iran Nuclear Deal. Its violations of the agreement since 2019 prove that the restrictions put on its nuclear program as part of the deal can be easily undone. Further, Iran has not cooperated with efforts by international inspectors to investigate potentially undeclared nuclear material in Iran.

| 9. | [Treatment Groups] How convincing do you find this argument?

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10. | [Treatment Groups] All things considered, do you support or oppose the Iran Nuclear Deal?

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11. | [Treatment Groups; open-ended] Why? If you have changed your mind, please explain why. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

AUKUS

[All] AUKUS is a trilateral security partnership between Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States aimed at preserving security and stability in the Indo-Pacific region, particularly in light of China’s growing economic and military strength. Announced in September 2021, its most prominent initiative will be to help Australia acquire nuclear-powered submarines. These submarines will be powered by nuclear reactors, but they will not be armed with nuclear weapons. However, it is likely that the nuclear fuel for these reactors will be made from a form of uranium that could be used in nuclear weapons.

| 12. | [All] Do you support or oppose the United States helping Australia acquire nuclear-powered submarines?

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13. | [All] How closely have you followed this issue?

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14. | [All] As far as you know, is Australia a member of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT)?

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[T1: Nature of Agreement] The AUKUS agreement is a next-generation partnership that increases cooperation between the three allies at a time when China’s economic and military strength is growing. Helping Australia acquire nuclear-powered submarines clearly demonstrates and strengthens America and Britain’s commitment to Australia and the Indo-Pacific region.

[T2: Allies] Some U.S. allies and partners in the Indo-Pacific support the AUKUS submarine initiative. Taiwan, for example, welcomes the AUKUS partners’ efforts to develop more advanced capabilities to defend the region.

[T3: Security] Nuclear-powered submarines are superior in their military capabilities to other submarines. They are therefore better suited to countering Chinese capabilities and ensuring the security interests of the United States and its allies in the Indo-Pacific region.

[T4: Trust] Australia has a strong record of supporting efforts to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons. We can trust that they will not use the nuclear material needed to power the submarines for nuclear weapons.

| 15. | [Treatment Groups] How convincing do you find this argument?

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||