ABSTRACT

Research shows that people’s perceptions of historical violence shape many present-day outcomes. Yet it is also plausible that people emphasize or downplay certain events of the past based on how these resonate with their beliefs and identities today. With a population of diverse orientations involving Russia and Europe, Ukraine in 2019 was an important case for exploring how people’s present geopolitical orientations shaped perceptions of victimization in World War II. Drawing on a survey experiment, we find evidence for “motivated reasoning” among Western-oriented respondents, who emphasized their family’s suffering in World War II when faced with information that attributed blame to the Soviet regime. We find no evidence for motivated reasoning among the Russian-oriented respondents.

Introduction

How do present beliefs shape people’s perceptions of their past? Specifically, to what extent do political identities of the day influence people’s memories of historical violence? These are the theoretical questions at the heart of this study, focusing on people’s memories of their family and community’s victimization during World War II, which we investigate in the case of Ukraine. Let us set the scene.

It is May 9, 2019, Victory Day, in Kyiv. Thousands walk toward the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, which commemorates the soldiers who died in World War II, or the “Great Patriotic War” as it is known in Russia and many former Soviet countries. The crowd, taking part in an event known as the “immortal regiment” that happens in several former Soviet countries on May 9, are clutching portraits of family members who died in the war. As they approach the obelisk to lay flowers, they encounter heckling from young men holding banners of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA). In Ukrainian nationalist circles, this wartime militia are heroes who fought a Soviet regime that terrorized and sacrificed its own population. To Soviet veterans and their families – and per the Russian framing of World War II – they were local fascists who collaborated with the Nazis.

On the same day, speaking at the Victory Day Parade in Moscow, President of Russia Vladimir Putin – echoing both past and future Victory Day speeches – stated that:

Today, we see how a number of countries are deliberately distorting war events, and how those who, forgetting honour and human dignity, served the Nazis, are now being glorified, and how shamelessly they lie to their children and betray their ancestors.

Our sacred duty is to protect the real heroes. We bow to all veterans from the generation of victors. You live in different countries, but the feat that you accomplished together cannot be divided. We will always honour all of you and glorify Victory, which has always been and remains one for all of us. (Kremlin Citation2019)

Neither the outgoing nor the incoming Ukrainian president – Petro Poroshenko or Volodymyr Zelensky – spoke on May 9, 2019. Since Ukraine’s parliament passed the “decommunization laws” in 2015, Ukraine has celebrated the end of World War II on May 8 instead, aligning commemorations of the war with countries of the European Union and the United States rather than with Russia. It has also aligned itself with the conventional Western World War II chronology, which dates it from September 1939 with the invasion of Poland (after the Nazi–Soviet pact), and not from June 1941 as the “Great Patriotic War” narrative has it. In 2019, the Ukrainian state marked three occasions that further emphasized aspirations toward Europe, the foundations of its independence, and Soviet oppression: the 5th anniversary of the Revolution of Dignity (or Euromaidan, in 2013–2014), the 100th anniversary of key events of the Ukrainian Revolution for independence (1917–1921), and the 85th anniversary of the Holodomor, which it refers to as the Soviet regime’s “genocide of the Ukrainian people” (Ukraine Institute of National Memory Citation2018).

The organization of the present around a favored past has long been a central feature of geopolitical tensions within Ukraine. People well beyond Ukraine’s borders became acutely aware of the politicization of Ukraine’s history on February 21, 2022 (Andrejsons Citation2022), when, in a televised speech, Putin described Russia’s neighbor as “historically Russian land” that had become controlled by a “neo-Nazi” and Western “puppet” regime (Kremlin Citation2022). Three days later, Putin invoked the Soviet fight against Nazism in World War II to justify the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Since the fall of the Soviet Union, collective memories of the past have been tools in struggles over Ukrainian identity. We know that state elites use the past for present-day political ends. We know less about how ordinary people’s views of the past may be shaped by their beliefs and identities today. While much research on war and violence focuses on how individuals’ memories, perceptions, and experiences of past violence may influence their present beliefs, the causal arrow at the center of our study goes the other way: from the present to the past. Drawing on an original survey experiment from Ukraine in December 2019, we examine whether and how people’s geopolitical orientations shape their views of a historic violent event: World War II or, as Soviet nomenclature rendered it, the “Great Patriotic War.”

The creation of coherent narratives about historical events are central to states’ nation-building efforts. National anthems, school curriculum, and content of television programs are tools that governments use to forge a sense of national identity and shared history. These tools are not confined to the borders of the state. The post-Soviet Russian government has used the “Great Patriotic War” to forge a shared collective memory both within Russia and across the former Soviet countries in its “near abroad.” Ukrainian citizens have long found themselves on the front line in a contest between opposing narratives that are promoted by different political elites for political ends. As such, Ukraine is an ideal case for exploring whether and how people’s perceptions of the past have been shaped by their present-day geopolitical orientations toward Russia or the West.

We proceed as follows: Situating our study within research on collective memories and motivated reasoning, we outline the mechanisms through which present-day beliefs and identities can influence memories of past violence. We focus specifically on how, in the context of the former Soviet space, people’s geopolitical orientations can engender motivated reasoning and shape their memories of their family and community’s victimization in World War II. Drawing on an original survey experiment conducted in Ukraine in December 2019, we find some evidence for motivated reasoning. Specifically, we observe confirmation bias on the part of Western-oriented individuals (though not Russian-oriented individuals), who emphasized their family’s losses in World War II when faced with information that attributes blame to the Soviet regime for deaths that occurred during the war. We conclude by considering implications for research and policy.

Past Violence, Present Identities, and Motivated Reasoning

Do perceptions of the past shape present beliefs, or can it be the other way around? Can people’s present beliefs and identities shape how, or what, they remember of the past, specifically when it comes to their family or community’s past victimization?

The Past Explaining the Present?

A large and growing body of research shows that violence in people’s past – violence experienced by themselves, their family members, or their communities – shape present-day political outcomes, including political attitudes and behaviors, identities, as well as inter-personal, inter-group, and political trust. Political violence also has intergenerational effects. Examining the long-term effects of the Spanish civil war, Balcells (Citation2012) finds that the wartime victimization of an individual’s family members in this historic event led the individual to reject the perpetrator’s political identity in terms of present-day political cleavages (cf. Schaub Citation2023 on the Armenian genocide). She acknowledges the possibility that the story goes the other way and suggests that future research examine whether individuals’ present-day political identities would influence what they report about their families’ wartime experiences.Footnote1 Gerber and van Landingham (Citation2021) show that family members’ experience of historic violence during the 1930s repressions in Stalin’s USSR influenced whether and what people know about those events, but the challenge is the same as for Balcells (Citation2012), namely that even the awareness of family members’ experiences of past violence might be colored by respondents’ present-day views.

While many studies rely on individuals’ self-reports of past violence and victimization, increasingly, researchers aim to overcome the possibility of reverse causation by avoiding self-reports. Several studies rely on research designs utilizing geographic data to capture past violence within an individual or her ancestor’s area, examining the impact on either attitudinal or behavioral outcomes in the present (e.g. De Juan and Pierskalla Citation2016; Gilligan, Pasquale, and Samii Citation2014; Villamil Citation2021). For instance, studies of Ukraine that exploit exogenous spatial effects find that violence has an intergenerational impact on political preferences (Rozenas, Schutte, and Zhukov Citation2017) and that there are long-lasting legacies of the Holodomor (Rozenas and Zhukov Citation2019). Another way of overcoming the challenge of self-reports and potential reverse causation is to conduct multigenerational surveys, as in the Lupu and Peisakhin (Citation2017) study of Crimean Tatars in Crimea. In their study, interviewers randomly sampled households until they found respondents old enough to have experienced Stalin’s 1944 deportations first-hand and then interviewed first-generation respondents down their family chain. They find that the descendants of Crimean Tatars who suffered the most from violence during the deportations are different from those who did not suffer from the same historic violence in a number of ways: they are more likely to be politically active, identify with their ethnic group, and support their ethnic leaders.

While researchers who study legacies of violence have gone to great lengths to overcome potential challenges related to self-reports of individuals’ own or their community’s past victimization, the assumption underlying the avoidance of self-reports – that there are “doubts on the validity of self-reported exposure to victimization” (Grosjean Citation2014, 436) – remains largely untested in studies of political violence.Footnote2 A recent study of Ukraine suggests that, “contemporary appraisals of Stalin’s rule are not only explained by recollection and salience [of] past experiences, but by how people relate to today’s Russia under Vladimir Putin, who has used the power of Russian state media to engage in historical revisionism on a grand scale to justify expansionist policies” (Shkliarov, Mironova, and Whitt Citation2022, 976). The study relies on observational data and calls for an experimental approach to establish causality. We pick up on that call, focusing specifically on how ordinary people’s orientation toward Russia or the West may engender what social psychologists refer to as “motivated reasoning.”

Or the Present Explaining the Past?

Drawing on research in social psychology, we present theoretical reasons for when and how present beliefs would affect self-reported past victimization and examine the argument in an experimental research design. We do so in the context of Ukraine, arguing that people’s present-day geopolitical orientations may shape how they perceive their family and community’s past victimization.

We do not dispute that past violence and victimization, particularly historic events of violence, shape individual beliefs and identities today via socialization within the family, community, and across generations – through the memories and stories of the past that people are told at home, in history books, and through national anthems, monuments, and memorials – and, thus, explain broad patterns. But precisely because the mechanisms of transmission from the past to the present are memories and stories (cf. Walden and Zhukov Citation2020), there is the possibility that dynamics are more fluid – particularly when, at the elite level, the past is used to signal present-day positions.

Because memory plays such an important social role in defining who we are, we may selectively remember certain events and not others, downplay or emphasize certain elements of the past to fit the present (Fentriss and Wickham Citation1992). As noted by Baumeister and Hastings (Citation1997, 279–280), “(w)hen a group analyses some of the actions of its ancestors in the context of its new generational effects, it may selectively distort the memory of those events in order to fit them into the current set of beliefs.” Indeed, research shows that people process information about the world in ways that preserve their preexisting attitudes or allow them to arrive at self-serving conclusions based on their present beliefs or identities (Kunda Citation1990). In essence, individuals seek out or emphasize information that resonates with their beliefs or ignore information that is contrary to their beliefs in order to prevent cognitive dissonance, a discomfort that one feels when confronted with ideas that are contradictory. For example, Daniel Silverman (Citation2019) finds that people’s perceptions of violent events in war zones depend on their preexisting perceptions of the perpetrator (cf. Bausch, Pechenkina, and Skinner Citation2019). Similar processes can occur at an intergenerational level. Emma Dresler-Hawke (Citation2005), studying perceptions of grandparents’ role during the Holocaust, maintains that “collective memory is a reconstruction of the past in the broader contexts of community, politics and social dynamics of the present” (Dresler-Hawke Citation2005,144).

None of this is to say that people lie about their past, but instead that they present and value selective aspects of their history. It is people’s often complex and multifaceted pasts that allow them to “muster up the evidence necessary to support” their conclusions (Kunda Citation1990, 483). If an individual succeeds in accessing and constructing appropriate beliefs, she will feel justified in her conclusion and not realize that she also possessed knowledge that could support the opposite conclusion. This literature suggests that the memory search and belief construction of such “motivated reasoning” allow people to arrive at conclusions that fit their current beliefs.

Research on collective memories has long accepted that individuals do not “retrieve images of the past as they were originally perceived but rather as they fit into their present conceptions” (Misztal Citation2003, 53). Individuals’ present group identification may shape how they recall their own history and who they blame for historical harm committed or suffered by “their” group; Sahdra and Ross (Citation2007, 393) find that those with high group identification will recall “their group’s history in a manner that limits damage to their social identity” (cf. Doosje et al. Citation1998; Kahan Citation2013). Blame attribution will also differ. As noted by Doosje and Branscombe (Citation2003, 236), “(b)eing reminded of one’s ingroup negative history is likely to be threatening.” Hence, individuals tend to attribute past harm imposed by “their” group to external factors rather than ingroup factors. These studies all indicate that present-day group identification may shape individuals’ perceptions of their past.

Collective memories of historical violent events – particularly (in)famous ones, that is, historic ones – are central to communities’ “master narratives” (Hammack Citation2011), which guide people in how to tell their community’s history and serve as a template for future action (Hirst, Yamashiro, and Coman Citation2018). At the heart of these narratives are often historic events of collective suffering and glorious victories, highlighting national heroes and villains (e.g. Coakley Citation2004). Indeed, traumatic events, such as experiences of wars and violence, are often central to fostering shared identities through collective meaning (Hutchison Citation2016). They are central to defining who the “we” are and are transmitted both in people’s private (socialization in the family) and public spheres (through literature, arts, media, and education). Further, political elites use historical memories and myths for present-day political ends (Hobsbawm and Ranger Citation2012).

Given motivated reasoning, people may emphasize or downplay certain events of the past, historic violence in particular (as it is so central to national narratives and memories), based on how these events resonate with their beliefs today. Confirmation bias implies that individuals will seek out or emphasize and give credit to information that resonates with and reinforces their present beliefs and identities (Kunda Citation1990). In contrast, disconfirmation bias implies that when confronted with information that does not resonate with their beliefs, individuals will either actively denigrate and counterargue the information (Taber and Lodge Citation2006), emphasizing their present beliefs even more strongly through a “backfire effect” (Nyhan and Reifler Citation2010), or alternatively, simply ignore the new information.Footnote3

To empirically assess whether motivated reasoning is at work, we designed a study that allows us to vary attribution for historic violence.Footnote4 Most importantly, people are more likely to experience resonance or dissonance based on their present-day beliefs and identities if blame for past violence is clearly attributed, as attribution allows for ingroup versus outgroup identification. If blame for past violence is explicitly attributed to a certain actor from respondents’ perceived ingroup or outgroup, motivated reasoning will be more pronounced: people’s present-day beliefs and identities will be more likely to shape their assessment of the past, fostering either confirmation or disconfirmation bias. Similarly, if past violence is given an attribution that glorifies it, such an attribution, too, can foster motivated reasoning as individuals will, based on their present-day beliefs, want to think favorably about their perceived ingroup. In contrast, if no blame or glory is attributed, past violence is less likely to create either dissonance or resonance. As a result, bias that could result from motivated reasoning will be less pronounced.

We designed attribution primes that allow us to test for motivated reasoning in the form of both confirmation and disconfirmation bias, though the clearest expectation from the literature pertains to resonance creating confirmation bias, whereas dissonance can engender disconfirmation bias in the form of either resisting the information or simply ignoring it.

We present the specific propositions in in the research design section below, but first, we introduce the empirical setting. Given that national narratives and memories are often formed around violent and historic events, we examine people’s perceptions of past suffering in World War II, in the context of Ukraine.Footnote5 Ukraine is an ideal case for exploring whether and how people’s perceptions of historical violence are shaped by their present beliefs, particularly their geopolitical orientations, which concern how people perceive their belonging in a world of competing identities and narratives of belonging (cf. Toal Citation2017). Citizens in Ukraine have long found themselves in a geopolitical competition over their orientation toward Russia or the West, and memories of the past, particularly World War II, have been tools in this contest. Our survey was conducted in December 2019, before attitudes hardened due to Russia’s February 2022 full-scale invasion (though five years after the annexation of Crimea and the start of the Russian-backed separatist conflict in the Donbas). Even after the full-scale 2022 invasion, which has shifted public opinion in Ukraine toward the West (Bakke et al. Citation2023), Putin continues to draw on distorted versions of history to try to muster support for the war.

Table 1. Expectations for Treatment Primes (In Comparison to the Control Group)

Memory Wars and Geopolitics in the Former Soviet Space

Ordinary people in many of the post-Soviet states have long found themselves in an information competition with Russia over the framing of their past, so-called “memory wars” (e.g. Laruelle Citation2012; Torbakov Citation2011). Since the mid-2000s, the Russian government has tried to influence the beliefs and identities of ordinary people by promoting an image of a common Russkii Mir in its “near abroad” (e.g. Chapman and Gerber Citation2019; Hill Citation2006; Toal Citation2017). It has done so through pro-Russian social media, television programs, films, the church, and civil society organizations. In this effort, the “Great Patriotic War” has been a highly “politically usable” element of the past, which the Russian government has used, both within Russia and in the former Soviet states, to foster a common identity and collective memory around a shared history (Fedor Citation2017; Malinova Citation2017).

Political elites in some of the former Soviet republics have seen these efforts as threatening to their national identity and have, as such, sought to distance themselves from Russia (e.g. Feklyunina Citation2016; Rotaru Citation2018), rather seeking to orient their future toward the West. Anti-Soviet narratives of World War II and accounts of the Soviet regime’s violence and repression have been central to post-Soviet nation-building projects (e.g. Torbakov Citation2011; Yurchuk Citation2017). This narrative does not fit well with the Russian-promoted narrative about the past. Indeed “(t)he theme of the people’s double victimhood – at the hands of Hitler and Stalin alike – has virtually disappeared from [the Russian government’s] official discourse” (Malinova Citation2017, 63).

This competition over the past, used to signal the country’s present-day identity, is particularly prominent in Ukraine. It has been especially salient since Euromaidan in 2013–2014, Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, and the war with Russian-backed separatists in eastern Ukraine, although history, memory, and commemoration have been at the center of political division within Ukraine and in the Ukrainian–Russian relationship ever since the disintegration of the USSR (e.g. Ishchenko Citation2011; Lieven Citation1990; Portnov Citation2013; Törnquist-Plewa and Yurchuk Citation2019). Since the full-scale Russian invasion in 2022, Ukraine’s historical place among Western nations and its democratic origins have been an important emphasis in President Zelensky’s speeches (e.g. European Parliament Citation2023).

Ukraine long adopted a decentralized approach to commemoration and memory, with different regions commemorating different heroes and events (Portnov Citation2013). In western Ukraine, Western-leaning political elites adopted a historical narrative that Taras Kuzio (Citation2006) refers to as “Ukrainophone” – one that emphasizes a post-colonial discourse – while in eastern and southern Ukraine, more Russian-leaning political elites adopted a “Russophile” or “Sovietophile” narrative of Ukrainian history (Kozachenko Citation2019). The balancing act between regional geopolitical preferences about the country’s future changed after Euromaidan in 2013–2014 and the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014 (Klymenko Citation2020), when Ukrainian foreign policy shifted toward the West. This shift was reflected in the state’s official narrative of history and important events, which sought to end regional variation and promote the idea of an independent Ukrainian nation. In 2015, President Poroshenko pushed forward “decommunization laws,” which banned Communist symbols, and laws that recognized the Ukrainian Nationalist Organization (OUN) and its militia, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), as “independence fighters.”Footnote6 Through official commemorations, the Ukrainian government further emphasized the independent Ukrainian Republic (1917–1918), the atrocities committed by the Soviet regime in the Holodomor (1932–1933), and the OUN insurgency against the Soviet Union during and after World War II (1943–1950) (Katchanovski Citation2015).

While the growing body of research on “memory wars” have provided in-depth insights into the elite-level frames in this competition over the past – which is about the country’s orientation toward Russia or the West – we know less about how ordinary people navigate this competition. Individuals in Ukraine – and many countries in the former Soviet space – have for years found themselves torn between distinct narratives about the past that are used to signal their country’s geopolitical future. To the degree that motivated reasoning is at work, we would expect individuals oriented toward Russia to be more likely to view the past in line with the Russian-promoted narrative and those oriented toward the West to be more skeptical.

Research Design

Survey

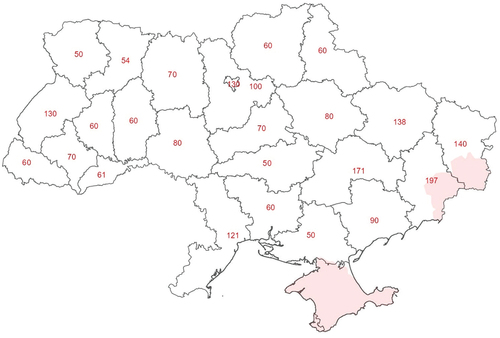

In December 2019, we designed and fielded a nationwide survey in Ukraine that allows us to investigate these relationships between the present and the past. It asked the respondents a range of questions aimed at capturing their geopolitical orientations, interest in politics (both domestic and international), political trust, views on historical events, outlook for the future, and socio-demographic background. The survey was conducted face-to-face on people’s doorsteps. Respondents were assured that their answers were anonymous and confidential, and they could opt to end the survey at any point.Footnote7 The sample (2,012 respondents) is nationally representative (excluding the areas not controlled by the Ukrainian government at the time in the Donbas and Crimea) (map in ). The survey was conducted for us by an experienced and reputable survey firm, the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KIIS). In our analyses, survey responses are weighted to account for sociodemographic imbalances with the respective population ratios. Only weighted results are shown.

Survey Experiment

To examine whether the survey respondents emphasize or downplay historic violence experienced by their community or family depending on their present-day geopolitical orientation, we conducted a priming experiment about World War II.Footnote8 We assess whether the respondents are more or less likely to emphasize victimization in this historic event if there is either a blame or glorification attribution. As discussed above, motivated reasoning is more likely to be at work if there is an attribution that triggers people to associate past violence with their perceived ingroup or outgroup.

The research design makes for a tough test for motivated reasoning. Individuals’ geopolitical orientation and perceptions of the past are the result of years of socialization. The primes in our experiment come “on top” of these longer processes, and we measure the outcome variables – perceptions of past victimization – by specific questions. Hence, if we do find that the primes elicit divergent responses in individuals’ perceptions of past victimization depending on their present-day geopolitical orientation, it is a strong indication that motivated reasoning is at work.

Control and Treatment Groups

We randomly assigned respondents to a control group and two treatment groups that received different primes about the Soviet Union’s responsibility for the deaths of Soviet citizens during World War II. Our main test is based on a prime that blames, or “vilifies,” the Soviet regime emphasizing its responsibility for deaths of Soviet citizens during the war (treatment group one). Here, we attribute blame to the Soviet regime for the deaths of both citizens (“repression”) and soldiers (“inhumane treatment”). Additionally, we developed a prime that “glorifies” those dying in defense of the Soviet Union during the war (treatment group two), which allows us to examine if what we can think of as a “glory” attribution will also elicit motivated reasoning. In this case, we attribute both civilian and military deaths to the defense of “their motherland,” emphasizing that these losses were part of a common struggle “made by all peoples and republics of the Soviet Union.” The primes represent two different framings of a historical event, and no disinformation was employed (the primes reflect frames about World War II used by the Russian and Ukrainian governments in 2019). As they are informed by elite narratives of the past, and, thus, focus on different causes of death, they cannot be directly compared to one another. The treatment groups should be compared to the control condition in which no framing is presented to respondents. All respondents then received the same questions intended to measure their self-reported family or community’s victimization in this historic event.

The control group received the following information about deaths in World War IIFootnote9:

Control: During the Second World War, it is estimated that between 22 and 28 million Soviet citizens died.

As there is no attribution for the violence in the control group, motivated reasoning based on present-day beliefs is likely to be low, so we expect that respondents’ present geopolitical orientation will have little bearing on how they answer questions about their family or community’s victimization. In contrast, in the treatment groups, we expect the attribution primes to elicit different responses about self-reported past victimization conditional on respondents’ geopolitical orientation.

The first treatment group received the same information as the control group but was primed to place responsibility for many of these deaths on the Soviet regime itself (a “vilification” prime). This narrative is explicitly anti-Soviet, but it is not anti-Russian. Nevertheless, it is a narrative that resonates with ethno-nationalist political elites in Ukraine, who often transpose “Soviet” and “Russia.” They view the Soviet Union as a period of Russian occupation under which “Russia is perceived as having inflicted suffering on Ukrainians, and Ukrainians are portrayed as having fought for Ukrainian statehood” (Klymenko Citation2020).

“Vilification” treatment: During the Second World War, it is estimated that between 22 and 28 million Soviet citizens died. Many also died as a result of the Soviet government’s inhumane treatment of its soldiers and repression of its own citizens: many were executed or died in prison, in the Gulag, and during the deportations.

For Western-oriented individuals who received this “vilification” prime, confirmation bias is likely to make them emphasize that victimization (in comparison to the control group) (Proposition 1). The blame attribution resonates with their more skeptical view of the Russian government and the Soviet past, reinforcing their present beliefs. If, in contrast, individuals who are Russian-oriented received the “vilification” prime, disconfirmation bias is likely to make them downplay that victimization (in comparison to the control group) (Proposition 2). The blame attribution does not resonate with the present Russian-promoted narrative about World War II and may, thus, not resonate with how Russian-oriented individuals see violence committed by the Soviet regime. Alternatively, these individuals may simply ignore the information that is contrary to their beliefs today.

The second treatment group also received the same information as the control group, followed by a prime that glorifies the Soviet Union, echoing the Russian government’s rhetoric about the “Great Patriotic War.” The language used – “sacrifices,” “motherland,” and “defend” – is based on that used in presidential addresses by Vladimir Putin and other official documentation.Footnote10

“Glorification” treatment: During the Second World War, it is estimated that between 22 and 28 million Soviet citizens died. They died to defend their motherland in the Great Patriotic War, and victory was the result of sacrifices made by all peoples and republics of the Soviet Union.

This treatment allows us to see if a “glory” attribution elicits motivated reasoning – and is a test of whether the Russian government’s efforts to create an identity around a shared past have had an effect on how ordinary people in the “near abroad” view historical violence. We note that whereas the “vilification” prime clearly attributes blame to an outgroup, in the “glorification” prime, no respondents’ ingroup is blamed for the violence, and therefore, the prime may not be as damaging to their social identity. As such, it may be less able to distinguish if motivated reasoning is at work.

If Russian-oriented individuals received the “glorification” prime, confirmation bias may make them emphasize suffering (in comparison to the control group) (Proposition 3). The prime’s “glory” attribution resonates with their present beliefs and identities – a sense of a shared Soviet past. If Western-oriented individuals received the “glorification” prime, disconfirmation bias may make them downplay the suffering of the past (Proposition 4). The “glory” attribution does not resonate with the narrative about the Soviet Union that is part of their present geopolitical orientation, which emphasizes a distance from a common Soviet past. Alternatively, these individuals may simply ignore the information that is contrary to their beliefs today.

Our expectations are summarized in . If motivated reasoning is at work, the effects of the primes will be conditional on present-day geopolitical orientations of the respondents (heterogenous and conditional treatment effects). Given the literature, the strongest expectation is that the prime that most clearly attributes blame – the “vilification” prime – elicits motivated reasoning, particularly in the form of confirmation bias.

Measuring Victimization in Historic Violence

To measure respondents’ self-reported family or community (ingroup) victimization in a case of historic violence, we asked two questions about their family and neighbors’ victimization in World War II.Footnote11 First, we asked: “How much did your family or neighbors suffer from death and violence during the Second World War?” We refer to this as our “historic suffering” variable, and the overall distribution of answers is “not at all” (16.3%), “some” (45.6%) and “a lot” (37.9%), providing an ordinal measure that captures intensity of victimization. Second, we asked, “Did you or your family suffer personal losses during the Second World War?,” to which respondents could say “no” (37.6%) or “yes” (62.5%).Footnote12 We refer to this as the “family loss” variable. Both questions are specific and, thus, a tough test for assessing motivated reasoning. Answers to the second question should be a particularly hard test for motivated reasoning because it limits opportunity to emphasize or downplay historical victimization in two ways: (1) it is a binary response and so there are simply fewer options, and (2) it is specifically about personal losses, limiting the possible evidence that respondents can “muster up” to support their conclusions (Kunda Citation1990, 483).

Measuring Geopolitical Orientations

We argue that the effect of the primes is conditional on present-day geopolitical orientations of the respondents. To measure respondents’ geopolitical orientations – whether they lean toward Russia or the West – we employed two survey questions. Respondents were asked to what extent they agreed with the following statements, each on a five-point scale: “I see myself as a person of the Western civilization” and “I see myself as a person of the Russian civilization.” The idea is to capture a broad sense of belonging. Capturing geopolitical orientations by asking about belonging to a civilization speaks directly to political discourse in the former Soviet space. For instance, many new NATO members have framed tensions with Russia as a civilization struggle (Toal Citation2017, 7). We created two dummy variables, to capture those who were explicitly oriented toward Russia or the West. Those who “strongly agree” or “agree” to the Western civilization question are coded as 1 on Western orientation (31.3%), while those who “strongly disagree” or “disagree,” as well as those who “neither agree nor disagree,” are coded as 0. Those who “strongly agree” or “agree” to the Russian civilization question are coded as 1 on Russian orientation (24.0%), while those who “strongly disagree” or “disagree,” as well as those who “neither agree nor disagree,” are coded as 0. As a check of whether these measures capture an association with a Ukrainophone or Russophile narrative of the past, in the Appendix, we examine whether they map onto questions capturing views of historical events, figures, and monuments – which they do.

Results

We first analyze the results of the experiment visually by plotting the means of the key dependent variables across the control and treatment groups, and then conduct linear and logistical regression analysis.

Inspecting the Differences in Mean

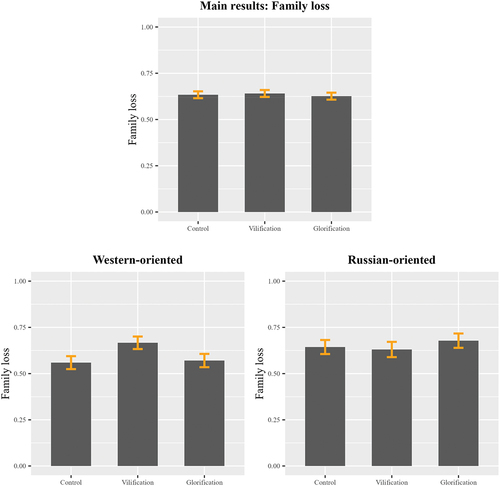

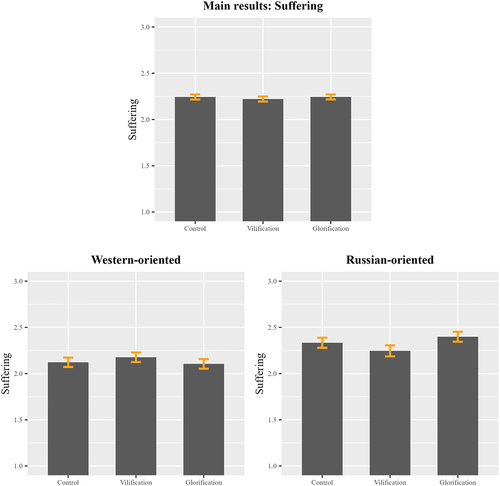

In , the x-axes show the treatment group and the y-axes show reported family loss and historic suffering, respectively. As the treatments are randomly assigned, differences in the means (between control and treatment groups) can be interpreted as the treatment effect of the “vilification” and “glorification” primes. The orange lines are error bars around the means for the groups. When they are overlapping, we cannot know at 95 percent confidence whether the differences between the bars are due to sampling error.

Figure 1. Difference in means in reported historic family loss across control and treatment groups for all respondents (top row) and subset by Western- and Russian-oriented respondents (bottom row).

Figure 2. Difference in means in reported historic suffering across control and treatment groups for all respondents (top row) and subset by Western- and Russian-oriented respondents (bottom row).

Consider first the top rows of , which show the average responses to questions about family loss and historic suffering, respectively. There is little discernible difference between the treatment and control groups for both questions. Focusing on the moderating effects of respondents’ geopolitical orientations, the bottom plots in the figures are more telling. Results for Western-oriented respondents are consistent with our expectations with respect to motivated reasoning in the form of confirmation bias. The means for those who receive the “vilification” prime is higher for both dependent variables. This prime clearly attributes blame. Being reminded of the fact that deaths also happened at the hands of the Soviet Union resonates with Western-oriented respondents’ present-day geopolitical orientation. This effect is particularly apparent and statistically significant for the reporting of family loss in , with 65.7% answering “yes” when they receive the “vilification” prime, compared to 56.1% of respondents in the control group, who receive no prime.Footnote13 We do not see any evidence for disconfirmation bias among Western-oriented respondents. They do not downplay historic suffering when treated with a “glorification” prime (rather, self-reported family losses increase slightly compared to the control group, though the difference is not statistically significant). This goes contrary to our expectations but is consistent with research suggesting that we are more likely to find evidence for confirmation bias than disconfirmation bias, as individuals who are confronted with information going contrary to their beliefs may simply ignore it.

For Russian-oriented respondents, the means for both dependent variables are higher than in the control group when Russian-oriented respondents receive the “glorification” prime, suggesting that there may be motivated reasoning in the form of confirmation bias. When respondents receive the “vilification” prime, they appear to downplay both forms of historical suffering, suggesting there may be motivated reasoning in the form of disconfirmation bias. However, the overlapping confidence intervals (shown by the error bars in the figures) leave us uncertain about these differences.Footnote14

Overall, these figures provide some evidence for a motivated reasoning effect, though the differences in means across the groups are small.

Regression Analyses

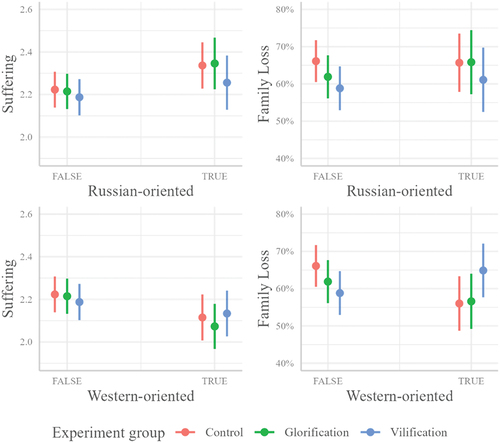

To test whether the differences identified above are statistically significant, we conduct regression analyses. Reported intensity of historic suffering and family losses are dependent variables. As above, we expect the treatments to have heterogenous effects contingent on the geopolitical orientations of the respondents. Hence, we include interaction effects between the treatments and the geopolitical orientations of respondents, both of which are dummy variables.Footnote15 Results for the interaction terms are presented in , which demonstrate support for confirmation bias on the part of the Western-oriented respondents.

Table 2. Results of Survey Experiment Including Demographic Controls. Models Include Robust Standard Errors

shows the results for interactions between the treatments (“vilification” or “glorification” primes) and the respondents’ geopolitical orientations. The first column shows the results for historic suffering as a dependent variable and the second column shows the results for reported family loss. For Western-oriented individuals, we expect the “vilification” prime to trigger confirmation bias: people will emphasize past victimization, given that the prime’s clear blame attribution reinforces their present beliefs. We do find that the effect of the interaction between Western-orientation and the vilification prime goes in a positive direction in both models and is statistically significant (p < .05) for respondents’ reported family loss. In the Appendix, we present predicted probability figures () and show that the findings are robust to alternative model specifications, including the inclusion of oblast-level fixed effects and imputed data ().

When Western-oriented respondents are confronted with the “glorification” prime, the coefficient signs across most of the models are in the expected negative direction, but these associations are not statistically significant. That is, there is no evidence of disconfirmation bias. There are a few reasons why this might be the case. First, as noted above, the attribution is less clear in the “glorification” than in the “vilification” prime, hence the effects may be weaker. Second, also as noted above, it may be that for some respondents, a prime that presents people with information that goes contrary to their beliefs may simply be ignored. Third, and more substantially in our empirical context, it is plausible that even though respondents who are Western-oriented may want to distance themselves from a shared and “glorious” Soviet past, that distancing does not extend to their memories of past victimization.

We turn then to the results for Russian-oriented respondents. Our expectation was that Russian-oriented respondents receiving the “vilification” prime are likely to downplay past victimization (motivated reasoning in the form of disconfirmation bias). And, we expected a positive effect for the “glorification” interaction (motivated reasoning due to confirmation bias). The interaction terms do not reach traditional levels of statistical significance in any model specification, though we note that coefficient signs are in the expected directions for reported historic suffering (though not the family loss variable) for the “vilification” interaction, and for reported family losses (though not for the historic suffering variable) for the “glorification” interaction. That is, there is no evidence for motivated reasoning on the part of the Russian-oriented respondents.Footnote16 This goes contrary to expectations though is consistent with the intuition that the “glorification” prime is the weaker prime, as it less clearly attributes responsibility, so it would be harder to find evidence for confirmation bias. And, as above, the vilification prime may, for some respondents, have been ignored. It may also be – and we probe below – that Russian-oriented respondents do not see the Soviet Union as their ingroup today, whereas Western-oriented respondents do see the Soviet Union as their outgroup.

In sum, we find some evidence for confirmation bias when the outgroup is explicitly blamed for historic victimization. When reminded of the deaths that happened at the hands of the Soviet regime (“in prison, in the Gulag, and during the deportations”), Western-oriented individuals are more likely to emphasize family losses in World War II than respondents who were given no such prompt.Footnote17 On average, compared to the control group, seven percent more Western-leaning respondents report a family loss (Model 4) – that is, they or their family suffered personal loss – when they receive the “vilification” prime. The “vilification” appears to reinforce, or resonate with, the view of respondents who already embrace a negative narrative about the Soviet regime, which is indicative of motivated reasoning in the form of confirmation bias.

Probing a Key Assumption and Alternative Explanations

An assumption underpinning such a relationship – and the priming experiment – is that Western-oriented respondents link Russia today and the Soviet Union as related to the same outgroup and Russian-oriented respondents link Russia today and the Soviet Union as related to the same ingroup. To probe this assumption, in , we examine a survey question that asked respondents how much they agreed with the following statement: “The Russian Federation should accept responsibility for the crimes committed against ordinary people during the Soviet Union.” A clear majority of Western-oriented respondents agree, whereas only a minority of Russian-oriented respondents do.

Table 3. Opinion on Russia’s Responsibility for Soviet Crimes, Broken Down Per Respondents’ Geopolitical Orientation

That is, a large majority of respondents who are geopolitically oriented toward the West attribute blame for victimization under the Soviet regime to Russia today. From this we conclude that the blame attribution of the “vilification” prime does evokes associations to the ingroup/outgroup and, per the logic of motivated reasoning, could be expected to reinforce the beliefs of those who are oriented toward the West and challenge those who are oriented toward Russia.

In terms of the different motivated reasoning findings for the Russian and Western-oriented respondents, we note that more Western-oriented respondents agree with the link between Russia today and violence in the Soviet past (76.3%) than Russian-oriented respondents who disagree with it (67.2%). Putin’s Russia has facilitated memorialization of victimhood associated with the Soviet Union (not without controversy), for example a Museum of the History of the Gulag opened in Moscow in 2015 and Putin inaugurated a monument to the victims of Soviet repressions in 2017 (Gullotta Citation2020). Possibly, although the frame of suffering in the “Great Patriotic War” dominates, this recognition of the Soviet past could be fostering a weaker ingroup association for the Russian-oriented respondents with the “vilification” prime. In turn, this could explain the stronger finding for motivated reasoning (in the form of confirmation bias) on the part of the Western-oriented respondents. It may also be that because victimhood in general features in both contemporary Ukrainian nationalist and Russian nationalist narratives, with public expressions of private suffering and loss (e.g. Laruelle Citation2021; Wood Citation2011), it may be too high of an expectation that a prime vilifying (or glorifying) the Soviet Union will overcome the centrality of suffering and engender motivated reasoning.

An alternative explanation for our finding is that the priming experiment causes respondents to give the answer they think the interviewer wants to hear. This could result in response bias in the form of social desirability bias, in which respondents attempt to present a favorable image of themselves. We do not think this is the case for two key reasons. First, given the political context in Ukraine, it is more likely that Russian-oriented respondents suffer from social desirability bias than Western-oriented respondents. However, the priming experiments do not have a statistically significant effect on Russian-oriented respondents. Therefore, we doubt that it is driving the finding for Western-oriented respondents.

Second, we conduct a robustness test that exploits the fact that characteristics of the interviewer may result in response bias (Agresti Citation2018, 32). Language identity – measured as native language as opposed to communicate language – is a strong predictor of people’s attitudes regarding salient issues such as historical memory (Kulyk Citation2011). We recorded the language in which the survey was conducted; almost perfectly half in Ukrainian and half in Russian. Enumerators conducted the interviews in Ukrainian or Russian depending on whether respondents greeted the enumerator in Russian or Ukrainian. This allows us to control for whether the survey was collected in a language that is different from each respondent’s native language. We expect that response bias will be higher if the self-declared native language of the respondent is different from the language in which the survey was conducted. Creating a binary variable that is 1 if the respondent’s native language is different from the language in which the survey was conducted and 0 if it is the same, we find that 22.7% of surveys were conducted in a language that was different from the respondent’s self-declared native language. We expect that if social desirability bias is driving our findings, then this variable, added to our existing analyses, will be statistically significant. shows that it is not significant in any of our models and its inclusion does not affect our findings.

Conclusion

Do people’s present-day beliefs or identities shape their views of the past? We draw on research in social psychology to develop an argument about how people’s present-day geopolitical orientations may shape their memories of past victimization in a historic violent event. We focus on people’s memories of their family members and community’s victimization during World War II, in the context of Ukraine. Ukraine is the ideal and important case for such an examination as competing versions of history have long been central to political divisions within the country – namely between a Ukrainophone narrative dominant in western Ukraine and a more Russophile/Sovietophile narrative in the southern and eastern regions – and between the country’s elites and the Russian government. Even before interstate relations deteriorated dramatically in 2014 and Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022, the two states have been competing in what scholars and political commentators refer to as “memory wars,” in which political elites draw on certain memories of the past to signal their present political orientation. While much research has focused on how governments and politicians in the former Soviet countries use the past for present-day political ends, we know less about how ordinary people’s perceptions of the past may be shaped by their present beliefs. We examine whether individuals emphasize or downplay historic victimization depending on their geopolitical orientation toward the West or Russia. The hypothesized mechanism is motivated reasoning: the tendency of individuals to selectively process information about the past so as to arrive at self-serving conclusions that fit their present-day beliefs and identities.

We designed a survey experiment that allows us to test if motivated reasoning is at work by varying attribution for historical violence. If blame is explicitly attributed to a certain actor from respondents’ perceived ingroup or outgroup, motivated reasoning – in the form of confirmation or disconfirmation bias – is likely to be more pronounced, and people’s present-geopolitical orientation will be more likely to shape their assessment of their past.

The experiment provides some evidence for confirmation bias. When confronted with a prime that reminds them of the deaths that happened at the hands of the Soviet regime, Western-oriented individuals are more likely to emphasize family losses in World War II than respondents who were not given such a “vilification” prime. This is a prime that resonates with Western-oriented respondents’ present-day geopolitical orientation, reinforcing their views. Though we expected motivated reasoning in the form of disconfirmation bias for individuals who identify as geopolitically oriented toward Russia if they were confronted with the same “vilification” prime, we find no such effect.

We also designed a prime that “glorified” those dying in defense of the Soviet Union, to see if this would elicit confirmation bias among the Russian-oriented respondents and disconfirmation bias among the Western-oriented respondents. This is potentially a weaker test for the argument as it is an attribution that does not clearly blame an outgroup, though it is a test for whether Russia’s attempt at creating a narrative of shared suffering in the “near abroad” has an effect on how people perceive the past. We found that this “glorification” prime made little difference in whether people emphasized or downplayed their family members’ or friends’ past victimization depending on their present geopolitical orientation.

Our experiment yields some evidence for a motivated reasoning effect, indicating that under certain circumstances, individuals will emphasize historical suffering in ways that confirm their present-day beliefs or identities. The findings show evidence only for confirmation bias, and only among the Western-oriented respondents, though the difference between the Western- and Russian-oriented respondents is well worthy of further investigation. Suffice to say here, given that the primes come “on top” of years of socialization and the questions we ask are rather specific – that is, we are presenting a tough test to examine whether motivated reasoning is at work – it is noteworthy that by simply adding a sentence of blame attribution, people appear to remember the past differently. These findings call for further research on the conditions under which motivated reasoning shapes people’s perceptions of historic victimization but speak in favor of caution when using self-reported perceptions of past violence to explain present-day outcomes. Our work poses further questions. Future work should consider the types of memories that are more or less malleable, under what conditions present-day elites activate salient memories, when and which past events predict political outcomes today, and how long such effects may last.

The results also have policy – and political – implications for countries where competing versions of history are central to political divisions. When blame for past violence is clearly attributed, people may come to view their community’s past victimization differently depending on their present-day beliefs. But we find no evidence that “glorifying” a common past affects how people report their historical suffering. This may, in part, help explain why Putin overestimated the extent of pro-Russian sentiment in Ukraine on the eve of the 2022 invasion. Despite years of the glorification of a common past, this narrative did not resonate with Ukrainians – even those who were already oriented toward Russia.

Acknowledgments

We thank Natalia Kharchenko, Oleksandr Bevziuk-Voloshyn, and their team at the Kyiv International Institute for Sociology (KIIS) for their guidance in the development of our survey instrument and for fielding the survey. The project is funded by a joint NSF-ESRC (SBE-RCUK 1759645 & ES/S005919/1) grant “With Russia or Not? The Geopolitical Orientations of Russia’s Neighbouring State Populations.” The paper, in various forms, has benefited from feedback in various fora: the annual meetings of the American Political Science Association, the British Association for Slavonic and East European Studies, and the Conflict Research Society, as well as seminars at University College London (UCL) and the Institut für die Wissenschaften vom Menschen (IWM). We thank Laia Balcells, Alexandra Hartman, and Leonid Peisakhin for their input in the early stages of developing our survey experiment. We thank the editor and reviewers at Problems of Post-Communism for their constructive suggestions.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data Availability Statement

The data and materials that support the findings of this study are available here: https://osf.io/aqkwy/.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Our study is inspired by Laia Balcells (Citation2012), who suggests this would require an experimental set-up.

2. There is a longer-standing literature on attitude formation in political behavior and foreign policy analyses that investigate motivated reasoning (e.g. Kertzer, Rathbun, and Rathbun Citation2020; Redlawsk Citation2002).

3. Per cognitive dissonance theory (Feistinger Citation1957), respondents may update or change their beliefs, though many beliefs are resistant to change, so people may also be avoiding information that would cause dissonance or exposing themselves to information that is consistent with their beliefs (cf. Frey Citation1982). While it is theoretically possible that respondents change their beliefs, it is not possible to evaluate this using our survey and experimental set up. A panel survey could enable us to look at changes over time, but ultimately, a single informational prompt, as in our experiment, is unlikely to change beliefs that have been acquired through years of socialization.

4. We do not examine how the source of the attribution (endorsement) may shape motivated reasoning (e.g. Bolsen, Druckman, and Cook Citation2014) or how the credibility of a source may shape the message’s effect (e.g. Hovland and Weiss Citation1951), as we do not provide a specific source of the information given.

5. This design does not enable us to explore whether memories of historic violent events, such as World War II, are more or less malleable than “smaller” historical violent events or nonviolent historic events. Given that violent historic events tend to be central to state- and nation-building efforts, they are likely to be at once both sticky and prone to entrepreneurial use in present political debates.

6. In the war, the UPA fought for independence from the Soviet Union and, in the process, collaborated with German forces perceived as sympathetic to that cause. The Ukrainophone narrative of the UPA and its political wing, the Ukrainian Nationalist Organization (OUN) and leader Stepan Bandera, is selective about their role during the war. Historians claim that the UPA were perpetrators in the Holocaust and the ethnic cleansing of the Polish population in the northwestern Volyn oblast (for more, see Liebich and Myshlovska Citation2014).

7. The survey was reviewed and approved by the Internal Review Board at the University of Colorado and the Ethics Committee at University College London.

8. While we presented the same expectation at several workshops and conferences before data collection, we did not pre-register the experiment and, therefore, all analysis should be considered exploratory.

9. E.g. Rummel (Citation1990) and Bacon (Citation1992) for estimates of Soviet repression during the war, including estimates for people sent to the Gulags.

10. Drawing on some of the terms highlighted by Olga Malinova (Citation2017) in her analysis of Putin’s rhetoric about the world war. See also, for example, Putin’s 2019 Victory Day speech (http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/transcripts/60490).

11. The questions were designed to reflect questions used in other surveys, such as “Were you, your parents or your grandparents physically injured or killed during the Second World War?” (Grosjean Citation2014) and “Do you know if, as a consequence of the civil war, any member of your family or close person … ?” (Balcells Citation2012).

12. This is similar to the Life in Transition Survey (LITS) conducted in 2010, which reported 60.6% “yes” to a similar question (Grosjean Citation2014).

13. While a Cohen’s d test indicates that this is a small effect size (0.22), we consider an almost 10 percentage point decrease to be theoretically substantive (Cohen Citation1988).

14. For details, see and .

15. In , we report the results from a split sample analysis, which supports the finding that when Western-oriented individuals are confronted with a “vilification” prime, they emphasize past victimization; and Balance tests () indicate that the treatment groups are balanced. However, as a robustness check we run alternative model specifications controlling for gender, age, education, and income, as well as oblast-level fixed effects (). Our interpretations remain the same.

16. We treat the control variables as controls (Keele, Stevenson, and Elwert Citation2020) but note that higher age and higher education are positively associated with the reporting of suffering and family loss.

17. This finding chimes with the Krawatzek and Friess (Citation2023) study of young people in Russia, in which they find that the clearest pattern for current political orientation shaping how people think of the past was related to the violence perpetrated by Stalin and the Red Army – with regime critics diverging from the official narrative.

References

- Agresti, A. 2018. Statistical Methods for the Social Sciences. London: Pearson Publishing.

- Andrejsons, K. 2022. “Putin’s Speech Laid Out a Dark Vision of Russian History.” Foreign Policy, February 22. https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/02/22/putin-speech-ukraine-war-history-russia/.

- Bacon, E. 1992. “Glasnost’ and the Gulag: New Information on Soviet Forced Labour around World War Ii.” Soviet Studies 44 (6): 1069–1086. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668139208412066.

- Bakke, K. M., G. Toal, K. Rickard, and J. O’Loughlin. 2023. “Putin’s Plan to Stop Ukraine Turning to the West Has Failed: Our Survey Shows Support for NATO at an All-Time High.” The Conversation, January 4. https://theconversation.com/putins-plan-to-stop-ukraine-turning-to-the-west-has-failed-our-survey-shows-support-for-nato-is-at-an-all-time-high-196967.

- Balcells, L. 2012. “The Consequences of Victimization on Political Identities: Evidence from Spain.” Politics & Society 40 (3): 311–347. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329211424721.

- Baumeister, R. F., and S. Hastings. 1997. “Distortions of Collective Memory: How Groups Flatter and Deceive Themselves.” In Collective Memory of Political Events: Social Psychological Perspectives, edited by J. W. Pennebaker, D. Paez, and B. Rimé, 277–293. London: Psychology Press.

- Bausch, A. A., A. O. Pechenkina, and K. K. Skinner. 2019. “How Do Civilans Attribute Blame for State Indiscriminate Violence?” Journal of Peace Research 56 (4): 545–558. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343319829798.

- Bolsen, T., J. N. Druckman, and F. L. Cook. 2014. “The Influence of Partisan Motivated Reasoning on Public Opinion.” Political Behavior 36:235–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-013-9238-0.

- Chapman, H. T., and T. P. Gerber. 2019. “Opinion-Formation and Issue-Framing Effects of Russian News in Kyrgyzstan.” International Studies Quarterly 63 (3): 756–769. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqz046.

- Coakley, J. 2004. “Mobilizing the Past: Nationalist Images of History.” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 10 (4): 531–560. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537110490900340.

- Cohen, J. 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. New Jersey: Erlbaum.

- De Juan, A., and J. H. Pierskalla. 2016. “Civil War Violence and Political Trust: Microlevel Evidence from Nepal.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 33 (1): 67–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0738894214544612.

- Doosje, B., and N. R. Branscombe. 2003. “Attributions for the Negative Historical Actions of a Group.” European Journal of Social Psychology 33 (2): 235–248. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.142.

- Doosje, B., N. R. Branscombe, R. Spears, and A. S. Manstead. 1998. “Guilty by Association: When One’s Group Has a Negative History.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 75 (4): 872. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.4.872.

- Dresler-Hawke, E. 2005. “Reconstructing the Past and Attributing the Responsibility for the Holocaust.” Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal 33 (2): 133–148. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2005.33.2.133.

- European Parliament. 2023. “Visit of Volodymyr Zelenksyy, President of Ukraine to the European Parliament – Formal Sitting: Address by Volodymyr Zelenksyy, President of Ukraine.” The European Parliament, February 9. https://multimedia.europarl.europa.eu/en/video/visit-of-volodymyr-zelenskyy-president-of-ukraine-to-the-european-parliament-formal-sitting-address-by-volodymyr-zelenskyy-president-of-ukraine_I237062.

- Fedor, J. 2017. “Memory, Kinship, and the Mobilization of the Dead: The Russian State and the “Immortal Regiment” Movement.” In War and Memory in Russia, Ukraine and Belarus, edited by J. Fedor, M. Kangaspuro, J. Lassila, and T. Zhurzhenko, 307–346. New York: Springer International Publishing.

- Feistinger, L. 1957. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Feklyunina, V. 2016. “Soft Power and Identity: Russia, Ukraine and the ‘Russian World(S)’.” European Journal of International Relations 22 (4): 773–796. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066115601200.

- Fentriss, J. J., and C. Wickham. 1992. Social Memory: New Perspectives on the Past. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Frey, D. 1982. “Different Levels of Cognitive Dissonance, Information Seeking, and Information Avoidance.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 43 (6): 1175–1183. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.43.6.1175.

- Gerber, T. P., and M. E. van Landingham. 2021. “Ties that Remind: Known Family Connections to Past Events as Salience Cues and Collective Memory of Stalin’s Repressions of the 1930s in Contemporary Russia.” American Sociological Review 86 (4): 639–669. https://doi.org/10.1177/00031224211023798.

- Gilligan, M. J., B. J. Pasquale, and C. Samii. 2014. “Civil War and Social Cohesion: Lab‐in‐the‐Field Evidence from Nepal.” American Journal of Political Science 58 (3): 604–619. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12067.

- Grosjean, P. 2014. “Conflict and Social and Political Preferences: Evidence from World War Ii and Civil Conflict in 35 European Countries.” Comparative Economic Studies 56 (3): 424–451. https://doi.org/10.1057/ces.2014.2.

- Gullotta, A. 2020. “Russia and the Gulag: Putin is Fighting for State Control over How Soviet Horrors are Remembered.” The Conversation, July 20. https://theconversation.com/russia-and-the-gulag-putin-is-fighting-for-state-control-over-how-soviet-horrors-are-remembered-142438.

- Hammack, P. L. 2011. “Narrative and the Politics of Meaning.” Narrative Inquiry 21 (2): 311–318. https://doi.org/10.1075/ni.21.2.09ham.

- Hill, F. 2006. “Moscow Discovers Soft Power.” Current History 105 (693): 341–347. https://doi.org/10.1525/curh.2006.105.693.341.

- Hirst, W., J. K. Yamashiro, and A. Coman. 2018. “Collective Memory from a Psychological Perspective.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 22 (5): 438–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2018.02.010.

- Hobsbawm, E., and T. Ranger. 2012. The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hovland, C. I., and W. Weiss. 1951. “The Influence of Source Credibility on Communcaiton Effectiveness.” Public Opinion Quarterly 15 (4): 635–650. https://doi.org/10.1086/266350.

- Hutchison, E. 2016. Affective Communities in World Politics: Collective Emotions after Trauma. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Ishchenko, V. 2011. “Fighting Fences vs Fighting Monuments: Politics of Memory and Protest Mobilization in Ukraine.” Debatte: Journal of Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe 19 (1–2): 369–395.

- Kahan, D. M. 2013. “Ideology, Motivated Reasoning, and Cognitive Reflection: An Experimental Study.” Judgment and Decision Making 8 (4): 407–424. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1930297500005271.

- Katchanovski, I. 2015. “Terrorists or National Heroes? Politics and Perceptions of the OUN and the UPA in Ukraine.” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 48 (2–3): 217–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postcomstud.2015.06.006.

- Keele, L., R. T. Stevenson, and F. Elwert. 2020. “The Causal Interpretation of Estimated Associations in Regression Models.” Political Science Research and Methods 8 (1): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2019.31.

- Kertzer, J. D., B. C. Rathbun, and N. S. Rathbun. 2020. “The Price of Peace: Motivated Reasoning and Costly Signaling in International Relations.” International Organization 74 (1): 95–118. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818319000328.

- Klymenko, L. 2020. “The Role of Historical Narratives in Ukraine’s Policy toward the EU and Russia.” International Politics 57: 1–17.

- Kozachenko, I. 2019. “Fighting for the Soviet Union 2.0: Digital Nostalgia and National Belonging in the Context of the Ukrainian Crisis.” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 52 (1): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postcomstud.2019.01.001.

- Krawatzek, F., and N. Friess. 2023. “A Foundation for Russia? Memories of World War Ii for Young Russians.” Nationalities Papers 51 (6): 1336–1356. https://doi.org/10.1017/nps.2022.12.

- Kremlin. 2019. “Victory Parade on Red Square.” The Kremlin, May 9. http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/60490.

- Kremlin. 2022. “Address by the President of the Russian Federation.” The Kremlin, February 21. http://www.en.kremlin.ru/events/president/transcripts/67828.

- Kulyk, V. 2011. “Language Identity, Linguistic Diversity and Political Cleavages: Evidence from Ukraine.” Nations and Nationalism 17 (3): 627–648. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8129.2011.00493.x.

- Kunda, Z. 1990. “The Case for Motivated Reasoning.” Psychological Bulletin 108 (3): 480–498. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.480.

- Kuzio, T. 2006. “National Identity and History Writing in Ukraine.” Nationalities Papers 34 (4): 407–427. https://doi.org/10.1080/00905990600842080.

- Laruelle, M. 2021. Is Russia Fascist? Unveiling Propaganda East and West. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Laruelle, M. 2012. “Negotiating History: Memory Wars in the Near Abroad and the Pro-Kremlin Youth Movements.” In Russian Nationalism, Foreign Policy, and Identity Debates in Putin’s Russia, edited by M. Laruelle, 75–105. Stuttgart: Ibidem Verlag.

- Liebich, A., and O. Myshlovska. 2014. “Bandera: Memorialization and Commemoration.” Nationalities Papers 42 (5): 750–770. https://doi.org/10.1080/00905992.2014.916666.

- Lieven, A. 1990. Ukraine and Russia: A Fraternal Rivalry. Washington, DC: US Institute of Peace Press.

- Lupu, N., and L. Peisakhin. 2017. “The Legacy of Political Violence across Generations.” American Journal of Political Science 61 (4): 836–851. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12327.

- Malinova, O. 2017. “Political Uses of the Great Patriotic War in post-Soviet Russia from Yeltsin to Putin.” In War and Memory in Russia, Ukraine and Belarus, edited by J. Fedor, M. Kangaspuro, J. Lassila, and T. Zhurzhenko, 43–70. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Misztal, B. 2003. Theories of Social Remembering. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Nyhan, B., and J. Reifler. 2010. “When Corrections Fail: The Persistence of Political Misperceptions.” Political Behavior 32 (2): 303–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-010-9112-2.

- Portnov, A. 2013. “Memory Wars in Post-Soviet Ukraine (1991–2010).” In Memory and Theory in Eastern Europe, edited by U. Blacker, A. Etkind, and J. Fedor, 233–254. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Redlawsk, D. P. 2002. “Hot Cognition or Cool Consideration? Testing the Effects of Motivated Reasoning on Political Decision Making.” Journal of Politics 64 (4): 1021–1044. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2508.00161.

- Rotaru, V. 2018. “Forced Attraction? How Russia Is Instrumentalizing Its Soft Power Sources in the “Near Abroad.”” Problems of Post-Communism 65 (1): 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2016.1276400.

- Rozenas, A., S. Schutte, and Y. Zhukov. 2017. “The Political Legacy of Violence: The Long-Term Impact of Stalin’s Repression in Ukraine.” The Journal of Politics 79 (4): 1147–1161. https://doi.org/10.1086/692964.

- Rozenas, A., and Y. M. Zhukov. 2019. “Mass Repression and Political Loyalty: Evidence from Stalin’s ‘Terror by Hunger’.” American Political Science Review 113 (2): 569–583. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055419000066.

- Rummel, R. J. 1990. Lethal Politics: Soviet Genocide and Mass Murder since 1917. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

- Sahdra, B., and M. Ross. 2007. “Group Identification and Historical Memory.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 33 (3): 384–395. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167206296103.

- Schaub, M. 2023. “Demographic and Attitudinal Legacies of the Armenian Genocide.” Post-Soviet Affairs 39 (3): 155–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/1060586X.2022.2143116.

- Shkliarov, V., V. Mironova, and S. Whitt. 2022. “Legacies of Stalin or Putin? Public Opinion and Historical Memory in Ukraine.” Political Research Quarterly 75 (4): 966–981. https://doi.org/10.1177/10659129211041633.

- Silverman, D. 2019. “What Shapes Civilian Beliefs about Violent Events? Experimental Evidence from Pakistan.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 63 (6): 1460–1487. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002718791676.

- Taber, C. S., and M. Lodge. 2006. “Motivated Scepticism in the Evaluation of Political Beliefs.” American Journal of Political Science 50 (3): 755–769. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00214.x.

- Toal, G. 2017. Near Abroad: Putin, the West, and the Contest over Ukraine and the Caucasus. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Torbakov, I. 2011. “History, Memory and National Identity: Understanding the Politics of History and Memory Wars in Post-Soviet Lands.” Demokratizatsiya 19 (3): 209–232.

- Törnquist-Plewa, B., and Y. Yurchuk. 2019. “Memory Politics in Contemporary Ukraine: Reflections from the Postcolonial Perspective.” Memory Studies 12 (6): 699–720. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750698017727806.

- Ukraine Institute of National Memory. 2018. “Report for 2018.” Ukraine Institute of National Memory. https://uinp.gov.ua/.

- Villamil, F. 2021. “Mobilizing Memories: The Social Conditions of the Long-Term Impact of Victimization.” Journal of Peace Research 58 (3): 399–416. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343320912816.

- Walden, J., and Y. M. Zhukov. 2020. “Historical Legacies of Political Violence.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.1788

- Wood, E. 2011. “Performing Memory: Vladimir Putin and the Celebration of WWII in Russia.” The Soviet and Post-Soviet Review 38 (2): 172–200. https://doi.org/10.1163/187633211X591175.

- Yurchuk, Y. 2017. “Reclaiming the Past, Confronting the Past: OUN-UPA Memory Politics and Nation Building in Ukraine.” In War and Memory in Russia, Ukraine and Belarus, edited by J. Fedor, M. Kangaspuro, J. Lassila, and T. Zhurzhenko, 107–137. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Appendix

Robustness Checks

In , we analyse the effect of the treatment on each subgroup (i.e. we split the sample), as opposed to employing interaction effects on the full sample, which we do in the manuscript. For example, column 1 shows the effect of the treatment groups (compared to the control group) on reported historic suffering (the ordinal dependent variable) for Russian-oriented respondents. For each group and dependent variable, we show results with and without demographic control variables. The final column supports the main findings in the manuscript, although the effect is statistically significant at 90 percent confidence levels (p<0.1).

Appendix table 1: Subgroup analysis of the experiment.

A concern in our main results reported in of the manuscript is the number of survey respondents that are dropped from the analysis. Almost 25 percent of respondents (N = 521) are not included in the analysis because they either answered “don’t know” or refused to answer one or more of the questions used to measure the variables included in the models (see data on missingness in ). We do not record worryingly high levels of missingness for any of our control variables or key independent variables. We record 10.4 percent and 10.6 percent missingness for historic suffering and family loss, which is not strikingly high for a question to which respondents may legitimately not know the answer. In we present the results using data that have been imputed using the demographic controls (age, education, gender, and income) (Naylor and O’Loughlin 2020). We conducted imputation using the MICE package in R. The results are substantively unchanged.

Appendix table 2: Analysis with imputed data.