Abstract

Public Administration’s attempts to understand race and racism insufficiently engage with the historical processes and legacies of White Supremacy. This paper problematizes whiteness and proposes an approach to expand social equity and deepen the field’s racial analysis. Drawing on institutional logics perspective, we identify and describe logics of whiteness, an analytic approach that reveals whiteness through the logics of racial capitalism and whiteness as property and provides entry for historical, systems-connected, multi-level analyses of race, racism, racial categorization, and racialized power. We locate whiteness in the institution of citizenship to engage these logics and interrogate how citizens and citizenship are defined by and served in the bureaucracy. Neoliberalism has allowed the administrative state to assign differential citizenship identities across groups according to the logics of whiteness, with both symbolic and material implications for individual lives and for Public Administration theory and praxis.

Introduction

Public Administration’s attempts to understand race and racism insufficiently grapple with the historical processes and legacies of white supremacy. Scholars frequently locate concerns about race and racism within the field’s values and aspirations for social equity. Social equity emphasizes equality in the distribution of public services, fairness and citizen participation in public policy creation and management, responsiveness to the needs of citizens rather than the needs of public organizations, and responsibility for decisions and program implementation by public managers (Frederickson, Citation1980; Gooden, Citation2017; Guy & McCandless, Citation2012; Lopez-Littleton & Blessett, Citation2015). Social equity scholarship suggests a distinct focus on equality and fairness in public policy creation, public management, and the distribution of public services, and an approach to the study and education of Public Administration that is interdisciplinary, applied, problem-solving in nature, and theoretically sound. As such, social equity is framed as not only a value of public administration but also a rationale, a course of action, and an administrative goal (Guy & McCandless, Citation2012).

The field’s approach to social equity is widely attributed to ideas first conveyed by Frances Harriet Williams in 1947 and later coalesced at the Minnowbrook I Conference in 1968 under the aspirations and ambitions of New Public Administration (NPA). NPA proposed a “new” approach to U.S. public administration and policy that deviates from more orthodox approaches in its presumption that public administrators and the field itself are not value-neutral but value-laden (Frederickson, Citation1980; Gooden, Citation2017; Gooden & Portillo, Citation2011; Portillo et al., Citation2022). NPA was conceptualized to draw attention to the tangibly different realities of the citizenry, to challenge the notion of objectivity in public administration and policy, to highlight the existence of differences between citizens at the individual level, and also that pluralistic government systematically discriminates in favor of bureaucracies at the expense of those who lack political and economic resources (Frederickson, Citation1980). These underpinning ideas have generated a body of social equity scholarship and practice that emphasizes the difference between equality and equity (Gooden, Citation2015); a corrective distribution of values and resources (Denhardt, Citation2004); fair reflection and representation of bureaucratic actors (Bishu & Headley, Citation2020; Meier, Citation2019; Vinopal, Citation2019); and alignment to a democratic ethos of public administration (Nabatchi et al., Citation2011), primarily across U.S. federal and municipal public organizations and their systems. Despite the aspirations of NPA, a deeply embedded value of social equity that prompts comprehensive attention and solution to institutional and systemic inequities has yet to be fully realized (Gooden & Portillo, Citation2011). The field’s social equity frame is too “nervous” to confront the formation and persistence of race, racism, racial categorization, and racialized power (Gooden, Citation2014). Important scholarship on issues of social equity, race, and racism in the public sector is not part of the canon of Public Administration literature, which overwhelmingly places value on efficiency, economy, expertise, hierarchy, and rationality in a colorblind public administration (Heckler, Citation2017). Consequently, the field’s scholarship is largely anchored in theories that embrace equality and colorblind neoliberalism (Witt, Citation2006), hindering researchers’ ability to question the relevance of race and racism, to expand approaches when examining racism and racial injustice, and to interrogate how public sector organizations enact or perpetuate it (Headley, Citation2020).

Racism is a system that distributes resources to advantage one racial group over another (Tatum, Citation2017). In this system, discriminatory ideas of individuals are not exclusively responsible for this uneven distribution. However, when combined with access to resources, individual racism is given license and its impact amplified. Although individual beliefs and behaviors are reflected in it, racism cannot be reduced solely to these; instead, "…through conscious intent, unconscious bias, or policies and practices…" (Ray, Citation2022, p. 18), discriminatory ideas, actions, and processes are built into cultural messages as well as institutional rules and laws that have the effect of producing unequal access to social and material resources by race. In this way, racism structures the abilities of individuals and groups to access, connect to, and apply resources in their lives. In this system, the legitimacy associated with social organizations backed by state power grants privilege to the racial groups they represent, even without the express action of privileged group members. As a result, racism engenders racialized power.

In this paper, we problematize whiteness—a feature of racialized power—and propose an approach to expand social equity and deepen Public Administration’s racial analysis. Encompassing, yet distinct from the white racial identity, whiteness is the vested interest in the white identity (Gillborn, Citation2005) that was constructed from colonial social relations, legitimated by science, and protected by law through time as supposed objective fact. Whiteness is both a possession predicated on exclusion and exploitation (Harris, Citation1993) and a racial discourse (Gillborn, Citation2005) that infers and accepts that the white identity is something of value, privileging those “perceived to be white over people of color” (Yoon, Citation2012, p. 589).Footnote1

Like white identity, whiteness is socially, economically, and politically constructed and thus directs power and social relations in the system of white supremacy (Ansley, 1997 in Gillborn, Citation2005). It is produced and reproduced through the social advantages it yields (Harris, Citation1993). As a result, it concentrates power in economic, political, psychosocial, and cultural structures and processes and portrays inequality as natural and necessary, endowing it with hegemonic status (Yoon, Citation2012)—invisible especially to those it benefits. Whiteness is the organizing principle of the social fabric, absolving it of scrutiny and in turn "othering" nonwhite groups (Gillborn, Citation2005; Shome, Citation2009). This bolsters its command as a tool that purports and maintains racial inequality. Whiteness, therefore, is itself an institution—a “[collection] of rules, norms, and cultures that dictate meaning for social life”—that attaches white phenotype and racial identity to privilege and “assumptions of superiority” (Heckler, Citation2019, pp. 268–269).

Drawing on the institutional logics perspective, we introduce logics of whiteness, an analytic approach wherein whiteness is revealed through the institutional logics of racial capitalism and whiteness as property. Institutional logics are material or cultural symbols and practices that reflect socially constructed and historical values and beliefs which shape individual and organizational meaning and behaviors (Thornton et al., Citation2012). Racial capitalism and whiteness as property, we assert, are two institutional logics that shape and maintain racialized reality in the U.S. Racial capitalism maintains that the interconnected systems of the U.S. political economy depend on racial practice and hierarchy, which produce and sustain inequality (Gilmore, Citation2022). Whiteness as property is a conceptual framework that captures how whiteness evolved historically in the U.S. to reflect the legal legitimacy of status and property accumulation for those deemed white to the exclusion of Black and Native American peoples (Harris, Citation1993). By engaging the logics of racial capitalism and whiteness as property, it becomes possible to understand and engage race beyond the mark of a demographic category.

Conceptualizing logics of whiteness allows scholars to widen the scope of equity using a racial analysis: to approach race, racism, and racial oppression through a historical, systems-connected, and multi-level framework where individual citizens and their agency are situated within organizational dynamics as well as social values, norms, and behaviors embodied by the administrative state. To illustrate our proposition, we locate whiteness in the institution of citizenship, a socially constructed identity formed through the convergence of territorial, national, cultural, linguistic, or moral boundaries (Williams, Citation2003), contextualized by time and place. We assert the utility of interrogating whiteness vis-à-vis the institution of citizenship to delineate how citizens and citizenship are defined by the administrative state and served in the bureaucracy through formal and informal organizations. Decisions about who meets the criteria for citizenship status rely on historical and contemporary processes and practices that are rooted in white supremacy, thus reifying whiteness by creating material and symbolic exclusion of othered groups from realizing full community participation (Alexander & Stivers, Citation2020; Blanco, Citation2022; Levine-Ransky, Citation2016).

The framework presented in this paper provides a point of view for researchers and practitioners to identify and interrogate whiteness where otherwise it goes unnoticed and to unveil the differences in citizenship, where belonging and rights are endowed to specific individuals and groups. The resultant inequalities particular groups experience through the underlying beliefs and demonstrable behaviors of the administrative state are linked to their perceived citizenship identities. The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. First, we discuss extant institutionalism literature and the institution of citizenship. We follow with an explication of the two logics of whiteness of interest in this paper: racial capitalism and whiteness as property. We provide an example of urbanization policies and processes to show how the logics of whiteness shape citizenship. Next, we further situate these logics of whiteness in contemporary examples of the administrative state’s neoliberalism to show the utility of this framework to a wide set of concerns in public administration and policy. Finally, we conclude with a discussion of how the field’s scholarship and practice can expand social equity toward full citizenship enfranchisement for all.

Institutional logics perspective

Scholarship on public administration and policy has long embraced institutional theories to depict sources of power and influence over organizational performance and decision-making. Whether using old institutionalism, neo-institutionalism, or institutional logics perspectives, they each understand that there are multiple layers of the institutional environment that, in various ways, hold sway over organizations within it, namely the sociocultural, formal or regulatory, organizational, and internal leadership or agency dimensions (Child, Citation1972; DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983; Selznick, Citation1953, Citation1996; Teodoro, Citation2014; Thornton et al., Citation2012). This dynamic interinstitutional environment has been argued to cause organizational stasis and rigidity that impedes organizational changes or undermines organizational goals (Kraatz & Zajac, Citation1996; Selznick, Citation1953). It has also been linked to organizational changes via institutional isomorphism (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983; Kraatz & Zajac, Citation1996; Teodoro, Citation2014; Tolbert & Zucker, Citation1983). Public Administration scholarship has utilized institutional scholarship to conceptualize inequalities in Black communities as an output of institutional racism (Blessett & Lopez-Littleton, Citation2017) and to frame whiteness as an institution that shapes all social behavior and public opinion (Heckler, Citation2019). Extant empirical scholarship has used institutional logics perspectives to explore organizational decision-making, outcomes, and civilian interactions with organizations (Ferry et al., Citation2019; Mattingly & Hall, Citation2008).

Institutional logics are “socially constructed, historical patterns of cultural symbols and material practices, including assumptions, values, and beliefs, by which individuals and organizations provide meaning to their daily activity, organize time and space, and reproduce their lives and experiences” (Thornton et al., Citation2012, p. 1). The institutional logics perspective helps researchers explore how individuals and organizational actors are influenced by their social context, where they exist within social situations within interinstitutional environments with multiple simultaneously occurring dimensions and layers. Within this ecosystem, no single dominant ideology dictates or constitutes the social context. Rather, institutional factors may influence actors through logics instilled with dynamic values that can change over time.

The institution of citizenship

The administrative state, including bureaucratic units and actors, has always played a role in supporting and maintaining U.S. democracy (Mosher, Citation1982; Raadschelders, Citation1995) and thus the boundaries of citizenship. U.S. democracy has developed and is asserted to be the model for the rest of the world, as it facilitates capitalist markets and engenders liberty and freedom (Almond, Citation1991). Through democratic processes, the government provides opportunities for effective and equal civic and political participation to exercise voice and control over the public agenda and for intellectual and moral enlightenment (Dahl, Citation1998). However, the administrative state and the bureaucrats who enact it are not bystanders to defining and drawing the boundaries of citizenship status and involvement (Denhardt & Denhardt, Citation2000) but instead actively behave in ways that sacrifice the citizen voice for efficiency operations (Cooper & Gulick, Citation1984). Rather than universally enable self-determination so all people may “live under laws of their own choosing” (Dahl, Citation1998, p. 53), the reality of U.S. democracy is one of explicit exclusion across racialized, gendered, and propertied lines (Davis, Citation2011; Du Bois, Citation1935; Mouffe & Holdengräber, Citation1989). The restrictive and circumscribed nature of U.S. democracy has prompted questions regarding how citizens can improve public service provision through their involvement and in what ways (Raadschelders, Citation1995), and is harmful to individuals and groups forcibly excluded. This is particularly true for groups racialized as other than white, non-cis-hetero males, and the impoverished (Berry, Citation2009; Hicks, Citation2010; Schwalm, Citation1997).

Citizenship is an institution imbued with great normative value and meaning and is produced and reproduced by actors and shaped by core logics (Bellamy, Citation2008). It signals “the promise of personal engagement, community well-being, and democratic fulfillment” (Bosniak, Citation1999, pp. 450–451). We conceptualize citizenship as an institution that is “constitutive of the societal community” (Turner, Citation1990, p. 189) to allow for engaging multiple conceptualizations of citizenship depending on the community of research or theoretical interest (such as nation, state, city, neighborhood, or demographic group). Following Collins (Citation2017), we view communities as the “template for power relations” that shape collective behavior and individual and collective identities. By linking individuals to organized society, these formal and informal organizations then mediate power and serve as sites of social reproduction or disruption of intersecting power relations. Citizenship then depicts the relationship of the individual to their community and the intersecting systems of power within said community. Citizenship, therefore, is an identity; it is an institution socially constructed by community members and depicts the shared fate of those belonging to that community (Williams, Citation2003).

The institution of citizenship is a socially constructed identity formed through the convergence of territorial, national, cultural, linguistic, and/or moral boundaries (Williams, Citation2003). The symbolic meanings of these boundaries are intertwined with the material structure and practice that define and recognize it; even as their symbolic meanings change over time (Raadschelders, Citation1995). For example, scholars have illuminated processes by which the standard of the native-born, white, propertied male structurally norms inclusive and exclusionary beliefs and behaviors over time (Alexander & Stivers, Citation2020; Hartman, Citation1997; Portillo et al., Citation2020). Scholars show that conceptualizations of citizenship have long been formed in this context of political and economic priorities and shifts, which continually shape the symbolic meaning and material structures that define the institution. The changing boundaries of citizenship (i.e., its inclusion and exclusion criteria) reflects the needs of the powerful and becomes associated with the racial categories as decided and delineated in that socio-political context (Ray, Citation2022).

Thornton et al.’ institutional logics framework (2012) acknowledges the duality of agency and structure, that institutions are both material and symbolic as well as historically contingent and can engage multiple levels of analysis. Citizenship satisfies the duality principle in that it has both individual and structural components. Individuals assume the identity of the citizen but also reproduce that identity through their actions and how they interpret their and others’ citizenship (Bosniak, Citation1999). Citizenship is also a social structure created by actors historically to assess the belonging, rights, and entitlements of those in the citizen in-group and out-groups (Williams, Citation2003). Citizenship is both symbolic (imbued with meaning and represents ideals that can change) and material (some formal structures or practices lead to citizenship or the recognition of it). Citizenship is historically contingent; in some historical periods, decision-makers first decided who could hold citizenship based on the prevailing institutional logics of the time, and changes over time are a response to the decisions that came before. Finally, citizenship can be investigated at multiple levels (Collins, Citation2017): nation, state, local, organizational, demographic, neighborhood, and others.

Conceptual framework: Logics of whiteness

Drawing on the institutional logics perspective, we identify and describe logics of whiteness, an analytic approach wherein the logics of racial capitalism and whiteness as property (re)shape the cultural symbols and material practices that constitute and reify whiteness. Following the institutional logic perspective, racial capitalism and whiteness as property operate according to three principles, such that they (1) have co-constitutive material and symbolic implications, (2) are historically contingent, and (3) operate at multiple levels of analysis. presents how the logics of racial capitalism and whiteness as property operate in each of the three principled manners shaping the institution of citizenship.

Table 1. The institutional Logics of Whiteness—racial capitalism and whiteness as property—and their principal elements.

The logic of racial capitalism

Capitalism in the United States is a system rooted in racism. Mindful that the field of Public Administration was established and is maintained within the nation’s political economy, the tensions between capitalism and democracy have been the subject of scholarship (Almond, Citation1991; Dahl, Citation1998; Schumpeter, Citation2010).Footnote2 However, extant scholarship scarcely addresses the interdependence of capitalism, democracy, and public administration and policy (Farazmand, Citation1999; Fortner, Citation2023). To address this gap, field scholarship needs a critique of capitalism and its role in racialization to grapple with the stratified and exclusionary nature of U.S. democracy and the bureaucracy.

Racial capitalism refers to the material and ideological stance of the capitalist mode of production built on and through inequality among racial groups and racial oppression, which extends and sustains social hierarchies (Gilmore, Citation2022). Building from W.E.B. Du Bois’s (Citation1935) telling of a corrected version of the Reconstruction period of U.S. history, Cedric Robinson (Citation1983, 2021) translated the concept of racial capitalism from South Africa’s anti-Apartheid intellectual and activist movements of the 1970s to the U.S. context. Robinson corrects the idea that racial thinking and rule emerged only after Christopher Columbus stumbled upon the Americas in 1492. He traces back to the dawn of European civilization, when conceptions of race, racial categorization, and racial oppression emerged out of feudalism. Robinson argues that capitalism was born with and continued to develop a racial hierarchy that extended from the economic to the social and political sensibilities in the U.S. through British colonial actions. Although race (i.e., white supremacy) and capital (i.e., capitalist accumulation) were fused in the early formation of the U.S. colony under the British, Du Bois and many later scholars showed the violence against and exploitation of Black people in the institution of slavery was indispensable to the building of wealth and capital in the U.S. and internationally. Slavery fundamentally molded the economic and social conditions for white workers drawn into collusion materially as overseers and psychologically through their identification with white supremacy (Alexander, Citation2010; Blackmon, Citation2009; Koshy et al., Citation2022; Wilkerson, Citation2020), to engender division among all working people (Du Bois, Citation1935).

The legacy of European colonialism in the U.S. and globally has resulted in a possessive investment in whiteness due to the white supremacist foundations of our democracy and capitalist society (Lipsitz, Citation1995). So embedded is racism in the economic, social, and political formation of the United States that capitalism is more accurately racial capitalism (Melamed, Citation2015). Race, along with all forms of white privilege, is "part of the internal gearing of capitalism" (Pierce, Citation2015, p. 292). This has implications for material and ideological interests that organize society and structure the behaviors of the administrative state (Brown & De Lissovoy, Citation2011).

The framework of racial capitalism allows scholars to understand democracy as racialized, to connect ideas on democracy and capitalism, and to address the reality of racism in the bureaucracy. In the nearly forty years since Robinson detailed the racial capitalism framework and its global application, scholars across academic disciplines have extended and applied its assertions to understand the racialized organization of society, social systems, and their institutions (see Gilmore, Citation2007, Citation2022; Kelley, Citation2017; McMillan Cottom, Citation2020; Woodly, Citation2022). However, Public Administration scholarship has yet to engage with this concept, writ large, with only several exceptions.

The concept of racial capitalism provides a logic where citizenship:

Rests on white supremacy and capitalist accumulation, fused together to organize society and social systems in both material and symbolic ways. Common material practices resulting from white supremacy as a structuring condition were indispensable to capitalist accumulation in the U.S. and internationally. (Principle 1 – Has co-constitutive material and symbolic implications)

Draws on conceptions of race and racial categorization that are historically contingent: they began at the dawn of European society to racialize European peoples and adjusted over time to accommodate new contexts. Capitalism developed a racial hierarchy that extended from the economic to the social to the political sensibilities in the U.S. through British colonial actions toward citizenship, the economy, and property. (Principle 2 – Is historically contingent)

Intertwines an individual’s lived experience in the broader social order through their relationship to the mode of production and engagement with civil, political, and social organizations that comprise the broader ecosystem. Power—the ability to access and allocate resources—at one level may be used to exert influence in another. (Principle 3 – Operates across multiple levels)

The logic of whiteness as property

A critical race scholar in legal studies, Cheryl Harris (Citation1993) set out arguments to identify whiteness as a form of property, providing an analysis that can be applied to visualize how whiteness functions. Harris provides an account of the roots of property rights in racial domination, elaborates on traditional, modern, and intangible conceptualizations of property, and describes how whiteness developed over time within those conceptions of property. In the traditional legal conceptualization, whiteness and white identity were characteristics (or the property) of free human beings; not having a white identity meant being the property of another or subject to displacement or death. In modern conceptions of whiteness as property, property is more broadly defined to include “jobs, entitlements, occupational licenses, contracts, subsidies, and a whole host of intangibles that are the product of labor, time, and creativity” (p. 1728). Harris further expands whiteness as property to be based upon one’s expectations of property due to established patterns and legal precedent, where the historical precedent of those racialized as white experiencing social, economic, and political power creates an expectation of privilege, resulting in those white privileges being legally protected as rights. The historical precedent of Black, Indigenous, and other communities of color differs significantly from white privileges, leading to a lack of protection due to a lack of precedent and, thus, expectation. Therefore, whiteness is a possession that can be tangible but also articulates an expectation or a right.

Harris further determined four property functions of whiteness to make explicit the behaviors and consequences of whiteness: (1) the right of disposition; (2) the right to use and enjoyment; (3) reputation and status property; and (4) the right to exclude. Through its property functions, Harris asserts, the power and privileges of whiteness may be withdrawn for some while allowing those who possess it to enjoy rights made unavailable to othered groups. Further, whiteness assigns a high value and status marker to those associated with it, whereas historically, it was an insult to be called Black, an affront upheld by law. As Nishi (Citation2021) states, “To put it plainly, those who are racialized as white tend to believe they have the right to own and enjoy the power and privileges that come with being white and the right to prevent BIPOC from participating in the same power and privileges" (p. 1166).

The concept of whiteness as property provides a logic where citizenship:

Symbolizes legitimacy and belonging to a community or government, enabling claims to material accumulation of property, status, state services, rights, and protections and influencing community or government decisions. This symbolic meaning bears material implications directly affecting where and how people live. (Principle 1 – Has co-constitutive material and symbolic implications)

Is shaped by ideas of U.S. settler colonialism, where property is the principal determinant of who is granted and may possess the status of citizen. White European, propertied males are viewed as full citizens to the exclusion of Indigenous, Black, Asian peoples, and all women. (Principle 2 – Is historically contingent)

Is codified through the property functions of whiteness in the ways that law has accorded those who possess whiteness the fundamental privileges and benefits that allow them agency in their own lives, influence on how others’ lives are structured, and a voice in how the broader society is organized. (Principle 3 – Operates across multiple levels)

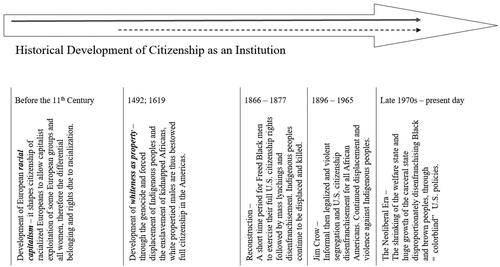

Considering the logics of whiteness vis-à-vis the institution of citizenship suggests that who is perceived to be a full citizen and who is permitted to identify as a full citizen has long been determined by the institutional logics of the administrative state. Though presented here alongside one another, the logics of racial capitalism and whiteness as property are intertwined in their constructions over time and place to reveal whiteness in the institution of citizenship. Together, these logics represent a set of interconnected conditions and outcomes that guide actions. These actions occur at the micro, meso, and macro levels—where the legitimacy conferred by citizenship is constructed and exercised among individuals, within organizations, across the public sector, and within the broader societal structure over time. depicts the logics of whiteness (racial capitalism gray arrow and whiteness as property dotted arrow) as they shape conceptions of citizenship (large arrow).

Urbanization policies and processes and logics of whiteness

Racial capitalism and whiteness as property provide logics of whiteness where perceived citizenship and citizenship rights are undermined for Black and brown residents. Dantzler (Citation2021) uses the concept of racial capitalism to illustrate how urban development policies and processes in the U.S. are fundamentally racialized to promote capitalist accumulation. We build from this understanding to add a discussion of whiteness as property and how it shapes the membership criteria of citizenship which frame belonging. Dantzler shows how racially minoritized individuals and communities are dispossessed of or displaced from urban spaces through economic and community development “redlining, blockbusting and segregation” (p. 121) as well as contemporary gentrification policies. Through these processes of dispossession and displacement, citizenship is undermined for racially minoritized communities and low-income communities for the benefit of wealthy and often white individuals and corporations. Whiteness as property manifests as a logic where those with wealth who are white have expectations of housing and housing value accumulation. Racial capitalism fundamentally shapes these property expectations which then prompts the dispossession and displacement of low-income Black and brown communities—extracting value from Black and brown properties to the benefit of white-owned property accumulation.

Dispossession and displacement reflect the material and symbolic implications of the logics of whiteness for urban residents, disenfranchizing Black, brown, and low-income residents. Dispossession takes place through either material dislocation from the neighborhood or home (via foreclosures and evictions), or symbolically through the strategic devaluation of the neighborhood or home. Allowing urban spaces to devalue through infrastructure neglect makes Black and brown communities ripe for redevelopment by corporations or wealthy and white individuals (Taylor, Citation2020). Displacement of these communities occurs when white residents, deemed as more deserving of the space, "[call] for more policing to promote public safety and protect their property values” (Dantzler, Citation2021, p. 122). Material displacement occurs through the loss of housing or the selling of rental properties to owners that eventually price out low-income and Black and brown residents. Symbolic displacement occurs through the over-policing of Black and brown residents deemed suspicious, a danger to the newly acquired property of wealthy and white individuals or corporations, and thus deemed to not belong in the reorganized urban space.

As emphasized earlier, these logics are historically contingent—where early disinvestment policies have enabled subsequent and selective redevelopment to expand space for the wealthy and white while marginalizing communities of color and poor communities. The re-organization of urban spaces has forced movements of people and changed the nature of civic engagement and political representation, resulting in changed economic, social, and political conditions and systems. These logics continually shape the priorities of the administrative state, and its organizations and bureaucrats in urban planning and policymaking.

Citizenship in the neoliberal era

The logics of whiteness are centuries old, and yet, have easily adapted to new social and political eras and contexts. The economic, social, and political distribution of power within the U.S., racialized through its colonial roots, has been further intensified by the neoliberal U.S. state. Although the mid-20th Century in the U.S. saw growth in the administrative state resulting from New Deal and civil rights legislation resource expansion, ideologies emerged to maintain the power of the institutional logics of racial capitalism and whiteness as property in shaping conceptions of citizenship such that resource expansion was uneven. Starting in the 1950s, political economists like Milton Freidman and the Chicago school theorized neoliberalism as:Footnote3

[A] transnational political project aiming to remake the nexus of market, state, and citizenship from above. This project is carried by a new global ruling class in the making, composed of the heads and senior executives of transnational firms, high-ranking politicians, state managers, and top officials of multinational organizations (the OECD, WTO, IMF, World Bank, and the European Union), and cultural-technical experts in their employ (chief among them economists, lawyers, and communications professionals with proper training and mental categories in the different countries) (Wacquant, Citation2010, p. 213).

The U.S. neoliberal state is a bipartisan endeavor that took off dramatically under Reagan’s presidency and expanded under all subsequent presidential administrations (Harvey, Citation2007; Wraight, Citation2019). Scholars of neoliberalism describe its central tenets as economic deregulation through marketization and financialization alongside an emphasis on individual responsibility (MacLean, Citation2018; Prasad, Citation2012). According to neoliberalism, the government’s role in economic activities is minimal, only to ensure business quality and money flow, while the state uses its resources to protect private property rights and free-market dynamics through the mobilization of military, police, and legal institutions. An artifact of centuries-old European colonial bureaucratic design, the mobilization of punitive state agencies is not simply a technical aspect of the neoliberal state but, like the colonial project, a selective and aggressive political power (Raadschelders, Citation1995; Wacquant, Citation2010). Scholars assert that the reduction and marketization of the welfare state occur strategically alongside the expansion of the carceral state and carceral ideologies to discipline the working class disproportionately along racial/ethnic lines (Soss et al., Citation2011; Wacquant, Citation2009).

Neoliberalism has allowed for differential citizenship identities of groups and individuals to be enacted by the administrative state according to the logics of whiteness. The neoliberal state’s resources are employed to uphold economic markets which then shape citizenship rights and perceptions at an institutional (governmental and regulatory) level. Consequently, they shape how organizations, both bureaucratic and market, perceive and racialize individuals and groups, and how they provide or withhold resources and services. A result of persistent variation in citizenship identity is the enduring and increasing inequality across public service and exacerbated along racial/ethnic demographic categories. Most recently, these inequalities have worsened due to the COVID pandemic and economic challenges (Harper-Anderson et al., Citation2023).

Citizenship differentiation in the neoliberal era is evidenced across fields of study and areas of public policy and administration. Social safety nets for individuals and families have weakened, causing low-income and disproportionately Black and brown communities and individuals to suffer health disparities, food and housing insecurity, and over-policing (Cobbina-Dungy & Jones-Brown, Citation2021; Schanzenbach & Pitts, Citation2020; Swope & Hernández, Citation2019). Those suffering have no recourse to improve their conditions yet are blamed for these structural deficits, which evidence reduced citizenship status (O’Connor, Citation2017). Accordingly, income and wealth inequality in the U.S. has grown significantly across racialized and ethnic groups (Toney & Hamilton, Citation2022; Weller & Karakilic, Citation2022). Meanwhile, the carceral state continues to increase in size and brutality, despite relatively stable crime rates, and although criminal activity is engaged proportionately across racial and ethnic groups, the carceral state disproportionately brutalizes and incarcerates Black and brown individuals (Cobbina-Dungy & Jones-Brown, Citation2021; Davis, Citation2011; Gilmore, Citation2007; Wacquant, Citation2010). Further, the responsibilities of social control are no longer confined to only those working in law enforcement but are now part of everyone’s duties (Charo, Citation2021; Stumpf, Citation2020; Zgonjanin, Citation2014). For instance, schools have become spaces of widespread surveillance and increased deputization of student behaviors, which disproportionately penalizes Black and brown children and youth (Shi & Zhu, Citation2022; Williams III et al., Citation2020). In another example, with the recent overturn of Roe v. Wade, states like Texas incentivize civilians to police one another, providing large bounties to those who turn in someone suspected of having or assisting in an abortion (Charo, Citation2021; Jackson, Citation2022).

The concentration of wealth and its connection to whiteness exacerbated by neoliberalism in the U.S. has ensured a status quo that dictates political discussions, policymaking, and their implementation in the bureaucracy (Lipsitz, Citation1995), undermining full citizenship. Neoliberalism serves to repress alternative perspectives that argue that a more robust welfare state is needed for the health of the populace and that the market will not undo the historical and contemporary wrongs fostered by the unequal distribution of economic, political, and social power (Collins, Citation2017; Davis, Citation2011; Harvey, Citation2007; Patel, Citation2016). The 2020 summer of protests against the carceral state were calls to address and make amends for the colonial, genocidal, inhumane foundation of our democracy and the mechanisms still in place today. The responding calls for increased funding for the carceral state by both Republican and Democratic parties signal the strong presence of bipartisan neoliberalism that endorses partial or negligible citizenship for low-income, immigrant, and communities of color, and the continued bureaucratic neglect and violation of citizenship rights for disenfranchized groups.

A project of full citizenship for expanded social equity

Mainstream Public Administration research has both reproduced and reinforced neoliberal values—colorblindness, hyper-individualism, commodification, financialization, and privatization—while too often ignoring the harms enacted by the administrative state. This brings us to where we are today: a field that continues to assume in our research and our practice an underlying objectivity and neutrality of bureaucratic decisions and behaviors despite the harm to individuals and communities of color at their hands (Feit et al., Citation2022). Owing to the logics of whiteness that differentially shape citizenship status and identities, scholarship should consider applying this racial analysis when examining and analyzing pressing and persistent public problems. This analysis may suggest solutions beyond a representative bureaucracy or similar strategies rooted in a race-evasive equity frame.

We provide this framework for Public Administration researchers and practitioners to grapple with the multiple conceptualizations of citizenship due to the dual logics of racial capitalism and whiteness as property. Carefully considering logics of whiteness has implications for scholarly and practical activity in the making of public administration and policy. Acts of public service by public servants are informed by patterns of individual and organizational power, developed, and assigned meaning over time, where racialized organizations shape agency (Ray, Citation2019). Pressing and persistent social problems in public administration and policy require a historical analysis, and solutions must consider what occurs at the organizational and institutional level rather than be left only to individual discretion. Further, considerations of who is involved in making administration and policy—which groups are granted citizenship and thus permission for full civic engagement—must occur so that both our scholarship and practice may consider whose voice and power are represented or marginalized.

We follow Dahl & Soss (Citation2014) in pressing the field to think about how our research approaches may reify the neoliberal status quo, which we argue maintains the logics of whiteness. We urge the exploration of how a conceptualization of citizenship that is racially-based manifests in institutional norms, the development and selection among policy alternatives, the management and governance of organizations, and the interpersonal interactions between bureaucrats and the public. Close attention must be paid to the conceptualizations of citizenship for Black, Indigenous, Latine, Asian, gender nonconforming, female, and other targeted individuals and groups. By acknowledging that these logics shape bureaucratic conceptions of citizen membership, belonging, and rights, scholars are prompted to understand and engage race beyond the mark of a demographic category. In so doing, unveiling whiteness allows scholars to widen the scope of social equity with a more tuned racial analysis.

Moreover, our broad conceptualization of citizenship requires that the scholarly community cease eroding the scholarly citizenship of Black and brown scholars, particularly women who have long pushed for equitable and just research outcomes and policy solutions to administrative harms. This demands a practice of deep reflexivity and a continued embrace of critical race theory scholarship despite the current violent and unfounded backlash, in addition to other bodies of literature long developed by Black and brown scholars both within and outside of the academy.Footnote4 For instance, intersectionality scholars have long pushed for an acknowledgment of multiple systems of oppression and professed solutions to the problems they and their communities experience (e.g., Blessett, 2023; Collins, Citation2019; Crenshaw, Citation2006; Jones, Citation2009; Lépinard, Citation2020; Nash, Citation2018; Taylor, Citation2017; Watkins-Hayes, Citation2019). Abolitionist scholars and activists have similarly asserted solutions to the violent citizenship disenfranchisement of centuries-long logics of whiteness (e.g., Abbott, Citation1991; Abu-Jamal, Citation2015; Davis, Citation2011; Gilmore, Citation2022; Green, Citation2008; Hernández, Citation2011; James, Citation2004; Sudbury, Citation2009; Ưguez, Citation2006). With the long history and continued settler coloniality maintained by the logics of whiteness, there exists a body of scholarship created to push forth decolonial solutions to the persistent disenfranchisement of Indigenous peoples (e.g., Byrd, Citation2011; Fanon et al., Citation1963; Veracini, Citation2008; Walia, Citation2014). Each of these scholarly perspectives has been marginalized in the academy, reducing the scholarly citizenship of these majority Black and brown intellectuals.

Whiteness in public administration and policy must be unveiled to achieve social equity. A scholarship and practice that acknowledges and confronts the erosion of citizenship and embraces solutions advanced by those who have long been disenfranchized have the potential to contribute to a society where full citizenship is bestowed upon and protected for all of its members. Then, the way is paved to move away from a society that is shaped by the administrative state’s race-based perceptions of who is a full citizen, and toward a truly democratic and equitable society. Akin to Dewey’s notion of the publics (Citation1927), equity in the democracy would be inspired by or envisaged through belonging, cooperation, collaboration, capability, and compromise, but only if all are fully enfranchised. The resultant democratically determined consensus would then lay the foundation for just policies, their equitable bureaucratic implementation, and the realization of genuine community self-determination.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge our colleagues at The Ohio State University with whom we engaged during the 2020-2021 academic year in deep study of literatures on justice: Jill Davis, Dr. Adrienne DiTommaso, Dr. Alannah Glickman, Kathleen Krzyzanowski Guerra, Dr. David Landsbergen, Dr. Yinglin Ma, Ken Poland, Dr. Rebecca Smith, and Dr. Aditi Vaishali Thapar-Grohe. Through the design and facilitation of a student-led course, we engaged in a critical and integrative review that laid the seeds of this paper. We are grateful to these colleagues and others who are energized to build community toward equity and justice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Charity P. Scott

Charity P. Scott is an Assistant Professor at the Wilder School and the Research Institute for Social Equity.

Nicole Rodriguez Leach

Nicole Rodriguez Leach is Executive Director of Grantmakers for Education and a Ph.D. candidate at the Glenn College.

Notes

1 A full discussion of white racial identity is outside the scope of this paper. In brief, white as an identity was defined and constructed in ways that increased its value by reinforcing its exclusivity (Harris, Citation1993). Through historical exclusion from property and rights as codified in law and administrative process, and thus power, white identity in the U.S. is defined contextually by who is considered white not by who is definitively white (Delgado & Stefancic, Citation1998).

2 Dahl (Citation1998) asserts that the market economy creates inequality, therefore undermining full political equality among the citizenry. Schumpeter (Citation2010) also acknowledges how capitalism undermines the representativeness of democracy due to competition.).

3 We do not distinguish neoliberalism from neo-conservativism, as Wacquant (Citation2010) asserts it is a false dichotomy.

4 For foundational writings of critical race theory scholarship, see Bell (Citation1995), Crenshaw (Citation2006), Crenshaw (Citation2017), Delgado & Stefancic (Citation1998), Harris (Citation1993), and Yosso (Citation2005).

References

- Abbott, J. H. (1991). In the belly of the beast: Letters from prison. Vintage.

- Abu-Jamal, M. (2015). Writing on the wall: Selected prison writings of Mumia Abu-Jamal. City Lights Books.

- Alexander, M. (2010). The New Jim Crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. The New Press.

- Alexander, J., & Stivers, C. (2020). Racial bias: A buried cornerstone of the administrative state. Administration & Society, 52(10), 1470–1490. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399720921508

- Almond, G. A. (1991). Capitalism and democracy. PS: Political Science & Politics, 24(3), 467–474. https://doi.org/10.2307/420091

- Bell, D. A. (1995). Critical race theory: The key writings that formed the movement. The New Press.

- Bellamy, R. (2008). Citizenship: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press.

- Berry, M. F. (2009). My face is black is true: Callie house and the struggle for ex-slave reparations. Vintage.

- Bishu, S. G., & Headley, A. M. (2020). Equal employment opportunity: Women bureaucrats in male-dominated professions. Public Administration Review, 80(6), 1063–1074. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13178

- Blackmon, D. A. (2009). Slavery by another name: The re-enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II. Anchor.

- Blanco, F. (2022). Race matters at the DMV? Public values, administrative racism, and whiteness in local bureaucratic settings. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 44(1), 46–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2021.1948735

- Blessett, B. (2023). Black women been know: Understanding intersectionality to advance justice. Journal of Social Equity in Public Administration, 1(2), 42–50. https://doi.org/10.24926/jsepa.v1i2.5034

- Blessett, B., & Lopez-Littleton, V. (2017). Examining the impact of institutional racism in black residentially segregated communities. Ralph Bunche Journal of Public Affairs, 6(1), 3.

- Bosniak, L. (1999). Citizenship denationalized. Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies, 7(2), 447–509.

- Brown, A. L., & De Lissovoy, N. (2011). Economies of racism: Grounding education policy research in the complex dialectic of race, class, and capital. Journal of Education Policy, 26(5), 595–619. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2010.533289

- Byrd, J. A. (2011). ‘Been to the nation, lord, but i couldn’t stay there’: American Indian Sovereignty, Cherokee Freedmen and the Incommensurability of the Internal. Interventions, 13(1), 31–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369801X.2011.545576

- Charo, R. A. (2021). Vigilante injustice – Deputizing and weaponizing the public to stop abortions. The New England Journal of Medicine, 385(16), 1441–1443. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2114886

- Child, J. (1972). Organizational structure, environment and performance: The role of strategic choice. Sociology, 6(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/003803857200600101

- Cobbina-Dungy, J. E., & Jones-Brown, D. (2021). Too much policing: Why calls are made to defund the police. Punishment & Society, 25(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/14624745211045652

- Collins, P. H. (2017). The difference that power makes: Intersectionality and participatory democracy. In The Palgrave handbook of intersectionality in public policy (pp. 167–192). Springer.

- Collins, P. H. (2019). Intersectionality as critical social theory. Duke University Press.

- Cooper, T. L., & Gulick, L. (1984). Citizenship and professionalism in Public Administration. Public Administration Review, 44, 143–151. https://doi.org/10.2307/975554

- Crenshaw, K. W. (2006). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

- Crenshaw, K. W. (2017). On intersectionality: Essential writings. The New Press.

- Dahl, R. A. (1998). On democracy. Veritas Paperbacks.

- Dahl, R. A., & Soss, J. (2014). Neoliberalism for the common good? Public value governance and the downsizing of democracy. Public Administration Review, 74(4), 496–504. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12191

- Dantzler, P. A. (2021). The urban process under racial capitalism: Race, anti-Blackness, and capital accumulation. Journal of Race, Ethnicity and the City, 2(2), 113–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/26884674.2021.1934201

- Davis, A. Y. (2011). Abolition democracy: Beyond empire, prisons, and torture. Seven Stories Press.

- Delgado, R., & Stefancic, J. (1998). Critical race theory: Past, present, and future. Current Legal Problems, 51(1), 467–491. https://doi.org/10.1093/clp/51.1.467

- Denhardt, R. B. (2004). Theories of public organization. Thomson/Wadsworth.

- Denhardt, R. B., & Denhardt, J. V. (2000). The new public service: Serving rather than steering. Public Administration Review, 60(6), 549–559. https://doi.org/10.1111/0033-3352.00117

- Dewey, J. (1927). The public and its problems. Holt.

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101

- Du Bois, W. E. B. (1935). Black Reconstruction in America: Toward a history of the part which black folk played in the attempt to reconstruct democracy in America, 1860–1880. Routledge.

- Fanon, F., Sartre, J.-P., & Farrington, C. (1963). The wretched of the earth (Vol. 36). Springer.

- Farazmand, A. (1999). Globalization and public administration. Public Administration Review, 59(6), 509–522. https://doi.org/10.2307/3110299

- Feit, M. E., Philips, J. B., & Coats, T. (2022). Tightrope of advocacy: Critical race methods as a lens on nonprofit mediation between fear and trust in the U.S. Census. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 44(1), 23–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2021.1944586

- Ferry, L., Ahrens, T., & Khalifa, R. (2019). Public value, institutional logics and practice variation during austerity localism at Newcastle City Council. Public Management Review, 21(1), 96–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2018.1462398

- Fortner, M. J. (2023). Public administration, racial capitalism, and the problem of “interest convergence:” A commentary on Critical Race Theory. Public Integrity, 2593), 262–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/10999922.2022.2113294

- Frederickson, H. G. (1980). New public administration. The University of Alabama Press.

- Gillborn, D. (2005). Education policy as an act of white supremacy: Whiteness, critical race theory and education reform. Journal of Education Policy, 20(4), 485–505.

- Gilmore, R. W. (2007). Golden gulag: Prisons, surplus, crisis, and opposition in globalizing California. University of California Press.

- Gilmore, R. W. (2022). Abolition geography: Essays towards liberation. Verso Books.

- Gooden, S. T. (2014). Race and social equity: A nervous area of government. M.E. Sharpe.

- Gooden, S. T. (2015). From equality to equity. In M. Guy & M. Rubin (Eds.), Public administration evolving: From foundations to the future (pp. 210–231). Routledge.

- Gooden, S. T. (2017). Frances Harriet Williams: Unsung social equity pioneer. Public Administration Review, 77(5), 777–783. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12788

- Gooden, S. T., & Portillo, S. (2011). Advancing social equity in the Minnowbrook tradition. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 21(Supplement 1), i61–i76. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muq067

- Green, T. T. (2008). From the plantation to the prison: African-American Confinement Literature. Mercer University Press.

- Guy, M. E., & McCandless, S. A. (2012). Social equity: Its legacy, its promise. Public Administration Review, 72(s1), 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02635.x

- Harper-Anderson, E. L., Albanese, J. S., & Gooden, S. T. (Eds.) (2023). Racial Equity, COVID-19, and public policy: The Triple Pandemic. Taylor & Francis.

- Harris, C. I. (1993). Whiteness as property. Harvard Law Review, 106(8), 1707–1791. https://doi.org/10.2307/1341787

- Hartman, S. V. (1997). Scenes of subjection: Terror, slavery, and self-making in nineteenth-century America. Oxford University Press.

- Harvey, D. (2007). A brief history of neoliberalism. Oxford University Press.

- Headley, A. M. (2020). Black lives and Public Administration: Current research and call to action. Retrieved from: https://academic.oup.com/jpart/pages/black-lives-vi/

- Heckler, N. (2017). Publicly desired colorblindness: Whiteness as a realized public value. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 39(3), 175–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2017.1345510

- Heckler, N. (2019). Whiteness and masculinity in nonprofit organizations: Law, money, and institutional race and gender. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 41(3), 266–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2019.1621659

- Hernández, K. L. (2011). Amnesty or abolition? Boom, 1(4), 54–68. https://doi.org/10.1525/boom.2011.1.4.54

- Hicks, C. D. (2010). Talk with you like a woman: African American women, justice, and reform in New York, 1890-1935. The University of North Carolina Press.

- Jackson, J. (2022). Full Text of Supreme Court Ruling Overturning Roe v. Wade. Newsweek. Retrieved from https://www.newsweek.com/read-supreme-court-ruling-overturning-roe-v-wade-1716972.

- James, J. (2004). Imprisoned intellectuals: America’s political prisoners write on life, liberation, and rebellion. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Jones, N. (2009). Between good and ghetto. In Between Good and Ghetto. Rutgers University Press.

- Kelley, R. D. G. (2017). The Rest of Us: Rethinking Settler and Native. American Quarterly, 69(2), 267–276. https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.2017.0020

- Koshy, S., Cacho, L. M., Byrd, J. A., & Jefferson, B. J. (2022). Colonial Racial Capitalism. Duke University Press.

- Kraatz, M. S., & Zajac, E. J. (1996). Exploring the limits of the new institutionalism: the causes and consequences of illegitimate organisational change. American Sociological Review, 61(5), 812–836. https://doi.org/10.2307/2096455

- Lépinard, É. (2020). Feminist trouble: Intersectional politics in postsecular times. Oxford University Press.

- Levine-Ransky, C. (2016). Whiteness Fractured. Routledge.

- Lipsitz, G. (1995). The possessive investment in whiteness: Racialized social democracy and the "white" problem in American studies. American Quarterly, 47(3), 369–387. https://doi.org/10.2307/2713291

- Lopez-Littleton, V., & Blessett, B. (2015). A framework for integrating cultural competency into the curriculum of public administration programs. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 21(4), 557–574. https://doi.org/10.1080/15236803.2015.12002220

- MacLean, N. (2018). Democracy in chains: The deep history of the radical right’s stealth plan for America. Penguin.

- Mattingly, J. E., & Hall, H. T. (2008). Who gets to decide? The role of institutional logics in shaping stakeholder politics and insurgency. Business and Society Review, 113(1), 63–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8594.2008.00313.x

- McMillan Cottom, T. (2020). Where platform capitalism and racial capitalism meet: The sociology of race and racism in the digital society. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 6(4), 441–449. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332649220949473

- Meier, K. J. (2019). Theoretical frontiers in representative bureaucracy: New directions for research. Perspectives on Public Management and Governance, 2(1), 39–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/ppmgov/gvy004

- Melamed, J. (2015). Racial capitalism. Critical Ethnic Studies, 1(1), 76–85.

- Nabatchi, T., Goerdel, H. T., & Peffer, S. (2011). Public administration in dark times: Some questions for the future of the field. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 21(Supplement 1), i29–i43. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muq068

- Nash, J. C. (2018). Black feminism reimagined: After intersectionality. Duke University Press.

- Mosher, F. C. (1982). Democracy and the public service. Oxford University Press.

- Mouffe, C., & Holdengräber, P. (1989). Radical democracy: Modern or Postmodern? Social Text, 1989(21), 31. https://doi.org/10.2307/827807

- Nishi, N. (2021). White hoarders: A portrait of Whiteness and resource allocation in college algebra. The Journal of Higher Education, 92(7), 1164–1185. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2021.1914495

- O’Connor, A. (2017). Poverty Knowledge. Princeton University Press.

- Patel, L. (2016). Reaching beyond democracy in educational policy analysis. Educational Policy, 30(1), 114–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904815614915

- Pierce, C. (2015). Mapping the contours of neoliberal educational restructuring: A recent review of neo-Marxist studies of education and racial capitalist considerations. Educational Theory, 65(3), 283–298. https://doi.org/10.1111/edth.12113

- Portillo, S., Bearfield, D., & Humphrey, N. (2020). The myth of bureaucratic neutrality: Institutionalized inequity in local government hiring. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 40(3), 516–531. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X19828431

- Portillo, S., Humphrey, N., & Bearfield, D. (2022). The Myth of Bureaucratic Neutrality: An Examination of Merit and Representation. Taylor & Francis.

- Prasad, M. (2012). The popular origins of neoliberalism in the Reagan tax cut of 1981. Journal of Policy History, 24(3), 351–383. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0898030612000103

- Raadschelders, J. C. N. (1995). Handbook of administrative history (1st ed.). Transaction Publishers.

- Ray, V. (2019). A theory of racialized organizations. American Sociological Review, 84(1), 26–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122418822335

- Ray, V. (2022). On Critical Race Theory: Why it matters & why you should care. Random House.

- Robinson, C. J. (1983, 2021). Black Marxism: The making of the Black radical tradition. (3rd ed.). Penguin.

- Schanzenbach, D., & Pitts, A. (2020). How much has food insecurity risen? Evidence from the Census Household Pulse Survey. Institute for Policy Research Rapid Research Report.

- Schwalm, L. A. (1997). A hard fight for we: Women’s transition from slavery to freedom in South Carolina. University of Illinois Press.

- Schumpeter, J. A. (2010). Capitalism, socialism and democracy. In Capitalism, socialism and democracy (3rd ed.). Harper Perennial Modern Classics.

- Selznick, P. (1953). TVA and the grass roots: A study in the sociology of formal organization (Vol. 3). University of California Press.

- Selznick, P. (1996). Institutionalism "old" and "new”. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41(2), 270–277. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393719

- Shi, Y., & Zhu, M. (2022). Equal time for equal crime? Racial bias in school discipline. Economics of Education Review, 88, 102256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2022.102256

- Shome, R. (2009). Outing whiteness. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 17(3), 366–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295030009388402

- Soss, J., Fording, R. C., & Schram, S. F. (2011). Disciplining the poor: Neoliberal paternalism and the persistent power of race. University of Chicago Press.

- Stumpf, B. (2020). The whiteness of watching: Surveillant citizenship and the carceral state. Radical Philosophy Review, 23(1), 117–136. https://doi.org/10.5840/radphilrev2020225105

- Sudbury, J. (2009). Reform or abolition? Using popular mobilisations to dismantle the ‘prison-industrial complex. Criminal Justice Matters, 77(1), 26–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/09627250903139223

- Swope, C. B., & Hernández, D. (2019). Housing as a determinant of health equity: A conceptual model. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 243, 112571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112571

- Tatum, B. D. (2017). Why are all the Black kids sitting together in the cafeteria? And other conversations about race. Basic Books.

- Taylor Jr, H. L. (2020). Disrupting market-based predatory development: Race, class, and the underdevelopment of Black neighborhoods in the U.S. Journal of Race, Ethnicity and the City, 1(1–2), 16–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/26884674.2020.1798204

- Taylor, K.-Y. (2017). How we get free: Black feminism and the Combahee River Collective. Haymarket Books.

- Teodoro, M. P. (2014). When professionals lead: Executive management, normative isomorphism, and policy implementation. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 24(4), 983–1004. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muu039

- Thornton, P. H., Ocasio, W., & Lounsbury, M. (2012). The institutional logics perspective: A new approach to culture, structure, and process. Oxford University Press.

- Tolbert, P. S., & Zucker, L. G. (1983). Institutional sources of change in the formal structure of organizations: The diffusion of civil service reform, 1880–1935. Administrative Science Quarterly, 28(1), 22–39. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392383

- Toney, J., & Hamilton, D. (2022). Economic insecurity in the family tree and the racial wealth gap. Review of Evolutionary Political Economy, 3(3), 539–574. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43253-022-00076-5

- Turner, B. S. (1990). Outline of a theory of citizenship. Sociology, 24(2), 189–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038590024002002

- Ưguez, D. R. (2006). Forced passages: Imprisoned radical intellectuals and the U.S. prison regime. University of Minnesota Press.

- Veracini, L. (2008). Settler collective, founding violence and disavowal: The settler colonial situation. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 29(4), 363–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/07256860802372246

- Vinopal, K. (2019). Socioeconomic representation: Expanding the theory of representative bureaucracy. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 30(2), 187–201. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muz024

- Wacquant, L. (2009). Punishing the poor: The neoliberal government of social insecurity. Duke University Press. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/authored-by/ContribAuthorRaw/Wacquant/Loïc.

- Wacquant, L. (2010). Crafting the neoliberal state: workfare, prisonfare, and social insecurity. Sociological Forum, 25(2), 197–220. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1573-7861.2010.01173.x

- Weller, C. E., & Karakilic, E. (2022). Wealth inequality, precariousness, household debt, and macroeconomic instability. Journal of Economic Issues, 56(2), 599–606. https://doi.org/10.1080/00213624.2022.2065864

- Walia, H. (2014). Undoing border imperialism (Vol. 6). Ak Press.

- Watkins-Hayes, C. (2019). Remaking a life: How women living with HIV/AIDS confront inequality. University of California Press.

- Wilkerson, I. (2020). Caste: The origins of our discontents. Random House.

- Williams, M. (2003). Citizenship as identity, citizenship as shared fate, and the functions of multicultural education. In Citizenship and education in liberal-democratic societies: Teaching for cosmopolitan values and collective identities (1st ed., pp. 208–246). Oxford University Press.

- Williams, J. A. III., Lewis, C., Starker Glass, T., Butler, B. R., & Hoon Lim, J. (2020). The discipline gatekeeper: Assistant principals’ experiences with managing school discipline in urban middle schools. Urban Education, 58(8), 1543–1571. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085920908913

- Witt, M. T. (2006). Notes from the margin: Race, relevance, and the making of Public Administration. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 28(1), 36–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2006.11029524

- Woodly, D. (2022). Reckoning: Black Lives Matter and the democratic necessity of social movements. Oxford University Press.

- Wraight, T. (2019). From Reagan to Trump: The origins of U.S. neoliberal protectionism. The Political Quarterly, 90(4), 735–742. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12709

- Yoon, I. H. (2012). The paradoxical nature of whiteness-at-work in the daily life of schools and teacher communities. Race Ethnicity and Education, 15(5), 587–613. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2011.624506

- Yosso, T. J. (2005). Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race, Ethnicity and Education, 8(1), 69–91.

- Zgonjanin, M. (2014). When victims become responsible: Deputizing school personnel and destruction of qualified immunity. Journal of Law and Education, 4(2), 455–462.