Abstract

Although children view pets (i.e. companion animals) as family members, child-pet relationships are rarely studied alongside other family relationships. In a socially diverse sample of 77 British families with pre-adolescent children (Mage = 12.14 years, SD = 0.29 years), we examine how the quality of children’s relationships with their pets and siblings vary in the context of adversity, and controlling for parent-child relationship quality, predict their behavioral adjustment. Children reported on the quality of their relationships and mothers rated child adjustment. Mother, child, and researcher ratings were combined to construct a multi-informant index of adversity. Child-pet positivity differed by adversity level for girls (but not boys) and, in low adversity contexts, was associated with greater concurrent prosocial behavior. Sibling positivity was unrelated to adversity, but had a buffering effect, in that adversity only predicted increases in problem behaviors over 12 months for those with low sibling positivity.

About 57% of households in the UK own pets (UK Pet Food, Citation2023), with families relying on pets (companion animals) as sources of support to alleviate stress and loneliness (Jalongo, Citation2021). However, developmental and family psychology have widely overlooked pet relationships despite their importance in family life; indeed, children commonly view pets as part of the family (e.g. Morrow, Citation1998). This is a notable gap, as the few exceptional studies to examine child-pet relationship quality show links with the quality of other family relationships (Bonas et al., Citation2000; Kerns et al., Citation2017). Researchers investigating human-animal interaction (HAI) also emphasize that children’s relationships with animals must be understood in the context of their relationships with humans (Melson, Citation2011).

In middle childhood and adolescence, children spend less time with their parents, as alternative relationships, such as those with siblings, become increasingly important (McHale et al., Citation2007). Pets and siblings are both important sources of support and companionship (e.g. Cassels et al., Citation2017; Hughes et al., Citation2023; White & Hughes, Citation2017), but child-pet and child-sibling relationships differ markedly in quality, with potentially important implications for children’s adjustment. As siblings typically differ in age, differences in social, cognitive, and language abilities may provide an important context for children to learn from each other (Howe et al., Citation2010). Children also learn from interactions with their pet but such learning is likely to be indirect through the new skills they develop as they care for their pet (Purewal et al., Citation2017). This study examines how pre-adolescents’ self-reported relationships with siblings and pets are linked to positive and negative behavioral outcomes and family adversity.

Children’s close relationships in adversity

As children’s interactions with others are embedded in a broader environmental context, adversity is likely to impact the quality of children’s close relationships (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979), yet views on the nature of this impact differ. For example, adversity results in stress, which can ‘spill over’ into family relationships, including sibling relationships (e.g. Kretschmer & Pike, Citation2009). In this view, adversity has cascading effects, where psychosocial stressors affecting one individual or relationship dyad in the family are transmitted to other individuals because of their relational interdependence (Masarik & Conger, Citation2017). However, in an alternative ‘compensatory’ view, siblings may band together in the face of adversity and be particularly close in the context of shared hardship, when they are facing the same stressors (e.g. Jenkins et al., Citation1989; McHale et al., Citation2007; Milevsky & Levitt, Citation2005). Evidence for each of these competing models is mixed.

Supporting the compensatory model, in a sample of African-American families, low parental education was associated with more positive sibling relationships in middle childhood and adolescence (McHale et al., Citation2007). Supporting the spillover model, two UK studies have shown that lower parental education and occupational status are each associated with increased rates of sibling antisocial behavior in early childhood, and with less positive sibling relationships in pre-adolescence (Dunn et al., Citation1994; Ensor et al., Citation2010). Adding to the complexity of findings, results from the UK-based Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) suggest a developmental contrast: at age 4, parental income was unrelated to older siblings’ negativity (Dunn et al., Citation1999), whereas at age 12, social class was negatively associated with sibling bullying (Bowes et al., Citation2014).

Some researchers have gone beyond socioeconomic disadvantage to examine the impact of other stressors on sibling relationships. Supporting a spillover perspective, Kretschmer and Pike (Citation2009) found that sibling positivity in 4- to 8-year-old children was more strongly related to chaos in the home environment than to socioeconomic status (parental education and housing density). Similarly, in a US study of Head Start pre-schoolers, Stoneman et al. (Citation1999) noted that residential instability was unrelated to sibling conflict but negatively associated with sibling harmony. Conversely, supporting a compensatory model, close and supportive sibling relationships have been noted in children who lack supportive parent-child relationships (e.g. Bank & Kahn, Citation1982; Hetherington, Citation1988).

Evidence regarding links between adversity and pet relationship quality remains inconclusive. On the one hand, children may reenact conflictual interactions experienced in human relationships with their pets (e.g. exposure to abuse or violence at home is a risk factor for childhood animal cruelty; Currie, Citation2006; Duncan et al., Citation2005). On the other hand, children may seek out their pet as a source of support during difficult times (e.g. Mueller et al., Citation2021). Pet attachment appears unrelated to family affluence in Scottish 7- to 12-year-olds (Hawkins & Williams, Citation2017). Similarly, in a study of UK pre-adolescents, the index of multiple deprivation was not associated with pet attachment (Westgarth et al., Citation2013). Yet pet attachment has been reported to be higher among American adults with fewer educational qualifications or lower incomes than college graduates or those with higher incomes (Cohen, Citation2002; Johnson et al., Citation1992; Lago et al., Citation1987), as well as in female undergraduate students exposed to childhood neglect (Barlow et al., Citation2012).

In measuring adversity, sibling and HAI researchers have typically focused on family income and parental education or occupation. Much less is known about how other types of disadvantage (e.g. neglect, parental mental illness, negative life events) affect children’s close relationships; this is a notable gap, as models of risk and resilience highlight the cumulative impact of exposure to risk (e.g. Evans et al., Citation2013; Masten, Citation2013). To address this gap, the present study examined positivity in children’s relationships with siblings and with pets in relation to a multi-informant index of adversity that drew on mothers’ responses to the Life History Calendar interview (Caspi et al., Citation1996) and Beck Depression Inventory (Beck et al., Citation1961), children’s responses to a measure of socioeconomic status, as well as researchers’ ratings of child neglect and participants’ home environment. We also examined gender differences in these associations, as prior research indicates that girls tend to report more positivity in their relationships with pets compared with boys (e.g. Hawkins & Williams, Citation2017; Hirschenhauser et al., Citation2017; Kerns et al., Citation2017; Muldoon et al., Citation2019).

Children’s close relationships and behavioral adjustment

Links between sibling relationship quality and child adjustment (including both positive and negative behavioral outcomes) are well established. In a meta-analytic review of 34 studies, sibling conflict and reduced sibling warmth were each associated with both internalizing and externalizing problems in children and adolescents (Buist et al., Citation2013). From the perspective of attachment theory, low levels of sibling warmth (i.e. insecure attachment to a sibling) lead to negative views of the self and the social world, which in turn promote anxiety, depression, aggression and antisocial behavior (Ainsworth, Citation1989; Fraley & Tancredy, Citation2012). Other researchers (e.g. Stauffacher & DeHart, Citation2006) suggest that social learning processes (Bandura, Citation1971) may underpin associations between sibling conflict and externalizing problems. For example, children may show behavioral problems when they observe conflictual interpersonal strategies being reinforced in family interactions (Pauldine et al., Citation2015), or when they imitate older siblings who engage in maladaptive behavior (Kim et al., Citation2007). Conversely, positive sibling interactions may provide an important context for children to learn and practice positive social behaviors. For example, a British study of 101 school-aged children showed that, beyond effects of parent-child relationship quality, more parent-reported positivity in sibling relationships predicted higher levels of parent-reported prosocial behavior (Pike et al., Citation2005). Similar independent longitudinal associations between child adjustment and sibling relationship quality have also been reported for a sample of 308 American adolescents, where sibling affection was positively associated with later prosocial behavior, and sibling hostility was positively associated with later externalizing behavior (Harper et al., Citation2014).

Positive pet relationships have been linked to children’s wellbeing and mental health (e.g. Gadomski et al., Citation2022). While teaching a child responsibility and care is one of the most frequent reasons parents cite for getting a family pet (Charmaraman et al., Citation2022; Fifield & Forsyth, Citation1999), few studies have examined how pet relationship quality is associated with children’s behavioral adjustment. One US study showed that positive general attitudes toward pets were associated with less delinquency and more prosocial behavior in 9–19 year-olds (Jacobson & Chang, Citation2018). Furthermore, for UK-based 7–13 year-olds, child-dog attachment was, through the way in which they interacted with their dogs, associated with increased prosocial behavior and reduced behavioral problems (Hawkins et al., Citation2022). However, the cross-sectional nature of these two studies precludes any causal inferences.

The present study expands the current understanding of links between children’s close relationships and their adjustment in two ways. First, extending HAI research on the association between positive pet relationships and adjustment (e.g. Hawkins et al., Citation2022), we examine this link across a one-year period. Second, building on research examining different types of close relationships (e.g. Harper et al., Citation2014; Kerns et al., Citation2017), we compare the contribution of sibling and pet relationships to children’s behavioral outcomes.

The interplay between adversity and close relationships in predicting children’s adjustment

Whether exposure to adversity leads to adaptive or maladaptive behavior depends on close relationships (Luthar, Citation2015). Forming attachments with close others is an adaptation that has evolved to provide protection and encourage exploration of the environment (Bowlby, Citation1982). Hence, the disruption of these close relationships leaves children vulnerable to adversity. Conversely, close relationships can foster resilience in children and promote adaptive behavior even in high risk contexts (Masten, Citation2013).

Findings from several studies suggest that, in the context of risk, positive sibling relationships may foster child adjustment. Supportive sibling relationships appear to mitigate children’s internalizing problems following stressful experiences such as social isolation, bullying, or negative life events (e.g. Gass et al., Citation2007). Likewise, a study of American pre-adolescents suggests that warm, harmonious sibling relationships attenuate the associations between parental psychological distress and child adjustment problems (Keeton et al., Citation2015). And in a recent six-site study conducted in the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic that involved 2,516 parents of 3- to 8-year-old children, Hughes et al. (Citation2023) found that the presence of an older sibling was associated with lower parental ratings of child adjustment problems.

Experimental studies with both children and adults have reported that interacting with pets can mitigate stress caused by laboratory-based stressful tasks (Beetz, Julius, et al., Citation2012; Kertes et al., Citation2017; Matijczak et al., Citation2023). Despite a strong rationale for exploring the buffering effect of pet relationships in the context of risk (e.g. Strand, Citation2004), few studies have examined how positive relationships with a pet might attenuate links between adversity and children’s adjustment, and their findings are mixed. In a sample of 107 American school-aged boys, children’s feelings of self-esteem derived from their relationship with their favorite pet attenuated the association between socioeconomic status and peer-reported reactive aggression (Bryant & Donnellan, Citation2007). However, other aspects of the pet relationship such as companionship and intimacy, did not moderate the link between adversity and aggression. In two studies of low-income families in the USA, positive interactions with pets buffered the negative impact of exposure to intimate partner violence on pre-adolescents’ internalizing symptoms, post-traumatic stress, and callous-unemotional traits (Hawkins et al., Citation2019; Murphy et al., Citation2022). However, pet ownership during the COVID-19 pandemic had no protective effects in a cross-sectional US-based sample of adolescents, who were more likely to perceive stress compared with those who didn’t have pets (Mueller et al., Citation2022). In another US-based study, while accounting for pre-pandemic levels of loneliness, pet positivity was unrelated to adolescents’ loneliness during the pandemic (Mueller et al., Citation2021).

Together, these findings suggest the protective effects of sibling and potentially, pet relationships for children facing adversity. However, as research in this field has typically focused on one relationship context and relied on single measures of social disadvantage, it is not clear whether sibling and pet relationships can compensate for a lack of support from other family relationships or buffer against the cumulative effects of different forms of adversity. This is important given cumulative risk indicators of adversity are stronger predictors of child outcomes than individual indicators (Evans et al., Citation2013). Thus, our final aim is to examine how pet and sibling positivity interact with a multi-informant index of adversity to predict both behavior problems and prosocial behavior.

Aims and hypotheses

The current study compared pre-adolescents’ relationships with their sibling and their pet and had three over-arching goals. The first of these was to compare how adversity affects sibling versus pet relationships. Although somewhat mixed, results from studies using single markers of disadvantage suggest a differential picture of competing processes in the two relationships, such that negative consequences of adversity spill over into sibling relationships, while pet relationships may compensate for adversity. We therefore hypothesized that in the context of high levels of adversity, children would report more positive pet relationships but less positive sibling relationships. Based on prior literature, we also examined gender differences in these associations, and hypothesized that girls would report more positivity in their relationships with pets compared with boys. Our second goal was to examine whether sibling and pet positivity contribute to variation in children’s behavior problems and prosocial behavior (both concurrently and one year later), over and above gender, social adversity, and parent-child relationship quality. Based on previous literature, we hypothesized that more relationship positivity (in both sibling and pet relationships) would be associated with fewer behavior problems and more prosocial behavior. Our final goal was to examine whether children’s relationships with siblings and pets buffered the negative impact of adversity on children’s adjustment. We hypothesized that, in the face of adversity, children with more positive relationships would exhibit fewer behavioral problems and more prosocial behavior.

Method

Participants

From a larger sample of 117 children taking part in a longitudinal study of social and cognitive development (for more details see Hughes, Citation2011), this study focuses on a subset of 77 children at the sixth wave of data collection who had both a pet and a sibling at home. This subsample was socially diverse: at the first time point of the current study 40% of mothers had age-16 qualifications, 37% had age-18 qualifications, and 23% had a tertiary degree. In addition, 30% of families were headed by a single parent. 35.6% of children had spent at least one year in a solo parent household, 63.6% of families had experienced four or more negative life events, and 21.9% of mothers scored above the “minimal range” threshold of depressive symptoms on the Beck Depression Inventory.

Reflecting the local population, 95% of the participating families were White British. Target children (41 boys and 36 girls) were, on average, 12.14 years old (SD = 0.29 years) at the first time point (Time 1) and 13.26 years old (SD = 0.40 years) at the second time point (Time 2). For ease of analysis, this study focuses on children’s relationship with one sibling who was closest to them in age and one pet. The average age of these siblings (39 brothers, 38 sisters) was 13.99 years (SD = 2.14 years) at Time 1 and 15.40 years (SD = 2.09) at Time 2. Siblings were on average 1.86 years older (SD = 2.13 years) than the target children but ranged from 3.36 years younger to 6.84 years older. At the first time-point the children had owned their pet for, on average, 4.32 years (SD = 3.42 years, range = 0.17–12.10 years). Of the 77 pets, 40% were dogs, 35% were cats; the remaining 25% included (most commonly) rabbits, guinea pigs, hamsters, fish, and chickens.

Procedure

As outlined above, this study was framed within two waves of a larger longitudinal study; for reasons of space, only methods relevant to the current study are discussed here. At the first time point (Time 1), two researchers visited study families in their homes for a 2-hour session, typically in the early evening. Mothers completed the Life History Calendar (Caspi et al., Citation1996) with a researcher, and both mothers and children completed a questionnaire booklet. Families were given £20 as a thank you for their time. After the session, the two researchers completed a questionnaire about their impressions of the home environment and family interactions during the visit. At the second time point (Time 2), parents were sent questionnaires by post and received a £10 gift voucher as a token of appreciation. Study procedures were approved by the University of Cambridge Research Ethics Committee, and all participating family members provided informed consent before each session.

Measures

Pet and sibling relationship positivity

Children reported on the quality of their relationship with their sibling and their pet using the Companionship, Intimate Disclosure, and Satisfaction subscales from the Network of Relationships Inventory (NRI; Furman & Buhrmester, Citation1985). The NRI has been widely used to measure children’s close relationships and was adapted for pets for this study (for more details see Cassels et al., Citation2017). Each NRI subscale contains three items which are rated on a 5-point scale from never to the most, and then averaged. For both pet and sibling relationships, ratings on the Companionship, Intimate Disclosure, and Satisfaction subscales were moderately to highly correlated (for siblings mean r = 0.59, p < .001; for pets mean r = 0.40, p < .001) and so these subscale scores were averaged to construct overall indicators of positive relationships with siblings (αsib = 0.80) and pets (αpet = 0.66).

Mother-child relationship quality

Children rated the quality of their relationship with their mother using Kern’s Security Scale (Kerns et al., Citation1996). This 15-item questionnaire employs the question format devised by Harter (Citation1982), where children responded to statements such as “Some kids find it easy to trust their mum BUT other kids are not sure if they can trust their mum” on a 4-point scale, by indicating which version they identified with and to what extent. The items assessed how responsive and available children perceived their mother to be, how much they relied on their mother in stressful circumstances, and how easy it was for them to communicate with their mother. Children’s scores across the 15 items were averaged to create an index of mother-child relationship quality (α = .83). Higher scores indicated a better quality of relationship.

Child adjustment

At both time points, mothers completed the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), a measure that has been used extensively in both clinical and community research samples (Goodman, Citation1997, Citation2001). The SDQ contains 25 items assessing children’s prosocial behavior and their emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, and peer relationship problems. Mothers rated each item on a 3-point scale indicating whether the item is not true, somewhat true, or certainly true for their child. We focused on the prosocial behavior subscale (T1 α = 0.85; T2 α = 0.80) and a total difficulties score created by summing the four problem subscale scores (T1 α = 0.67; T2 α = 0.78). Higher scores reflect higher levels of prosocial behavior and higher levels of behavior problems, respectively.

Adversity

A multi-informant aggregate index of family adversity was created for each child at the first time point by averaging standardized scores on seven indicators of socio-economic disadvantage: (i) negative life events; (ii) years in a solo-parent household; (iii) maternal depressive symptoms; (iv) maternal education; (v) child-rated socio-economic status; (vi) parental neglect; and (vii) quality of the home environment. These indicators were gathered at the first time point from several sources. The first of these was a maternal interview that included both demographic information and the Life History Calendar (Caspi et al., Citation1996), from which researchers rated the number of negative life events (e.g. deaths, illness, accidents, parental separation, difficulties at school) experienced during the child’s life time, and the number of years the child had spent living in a solo-parent household (range = 0–12 years). A second source was the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck et al., Citation1961), completed by mothers to report their experience of depressive symptoms (scores can range from 0 to 63). Mothers’ education was indexed by the age at which they had left full-time education (range = 15–29 years, with scores reversed before inclusion in the aggregate score). In addition, children completed the Family Affluence Scale (Boyce et al., Citation2006), a 4-item child-friendly measure of socio-economic status. Scores on this index can range from 0 to 9 and were reversed for the aggregate so that higher scores indicated higher levels of social disadvantage. Finally, two researchers each completed the Post-Visit Rating Scale (Moffitt, Citation2002), which includes global ratings of the home environment and interactions between family members. On the rating scale, 14 items ask about (rare) instances of neglect (e.g. lack of nourishment, lack of parental emotional support, lack of attention to grooming/personal hygiene), and 7 items assess the state of the home (e.g. safety of home, cleanliness, overcrowding). The two researchers’ scores for these subscales (which could range from 0 to 28 for neglect and from 0 to 14 for poor home environment) were checked for inter-rater reliability (state of home ICC = 0.92; neglect ICC = 0.90) and then averaged for each subscale.

Each of the seven different adversity scores was converted to a z-score and then averaged to create the multi-informant aggregate representing children’s exposure to adversity (α = 0.72).

Results

Analytic strategy

Our first goal was to compare the quality of children’s relationships (with pets and with siblings) for boys and girls, and for children experiencing low versus high levels of adversity (categorised using a median split; median = −0.11). In the absence of multicollinearity, using median splits is justifiable and allows for more parsimonious interpretations of associations (Iacobucci et al., Citation2015). So, we conducted a mixed design ANOVA with NRI scores as the dependent variable, gender and adversity level as between-subject variables, and relationship type (pet versus sibling) as a within-subject variable. Our second goal was to investigate whether variation in the quality of children’s relationships with siblings and/or pets predict individual differences in adjustment, over and above effects of adversity and mother-child relationship quality. Here, we conducted separate regression analyses, with either concurrent or later adjustment as the dependent variable and effects of gender, adversity, and parent-child relationship quality controlled at the first step. Our third goal was to explore the interplay between relationship positivity and exposure to adversity as predictors of children’s adjustment. To do this, we extended the regression analyses to include a variable representing the interaction between adversity group and relationship positivity. Significant interaction terms were explored by conducting simple slopes analysis. To avoid issues with multi-collinearity, sibling, pet, and parent-child relationship quality variables were centered before inclusion in regression analyses.

Descriptive statistics

displays descriptive statistics and correlations between the study variables. Individual differences in total difficulties (r = 0.79, p < .001) and in prosocial behavior (r = 0.80, p < .001) were highly stable across the one-year period of the study; mean scores for these variables also did not differ across time-points; total difficulties: t(60) = 0.50, p = .62, prosocial behavior: t(60) = −1.16, p = .25. Positivity with a pet or a sibling was related to higher maternal ratings of prosocial behavior both concurrently, and when assessed a year later. There were no differences in the magnitude of the association across time points (pet positivity: z = 0.14, p = .89; sibling positivity: z = 0.40, p = .69). Sibling but not pet positivity was also associated with lower levels of behavioral difficulties at both time points, and there was no significant difference in the magnitude of association (z = 0.94, p = .34).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and inter-correlations between study variables.

How do the quality of pet and sibling relationships vary in the context of adversity?

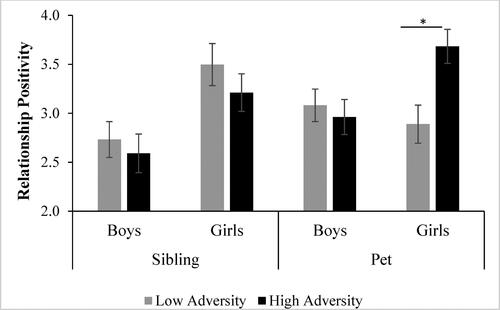

A mixed-design repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted to examine the effect of child gender and adversity on the quality of children’s relationships with siblings and with pets. Children’s reports of relationship positivity did not differ by type (sibling or pet; see for means), F(1, 73) = 1.39, p = .24, η2 = 0.02. However, on average, girls reported more positive relationships than boys, F(1, 73) = 11.44, p = .001, η2 = 0.14. Overall, the high and low adversity groups did not differ in relationship quality, F(1, 73) = 0.19, p = .66, η2 = 0.00, and there was no significant interaction between gender and adversity, F(1, 73) = 1.85, p = .18, η2 = 0.03. However, there was a small but significant interaction between adversity and relationship type, F(1, 73) = 4.93, p = .03, η2 = 0.06, such that pet positivity was higher for children experiencing high levels of adversity than children experiencing low levels of adversity, but there was little difference in sibling positivity between the low and high adversity groups. Finally, there was a small three-way interaction effect, F(1, 73) = 4.53, p = .04, η2 = 0.06, indicating that the effects of relationship and adversity differed by child gender. As shown in , boys experiencing high levels of adversity gave similar ratings of pet positivity and sibling positivity compared to boys experiencing low levels of adversity, for siblings t(39) = 0.57, p = .57, Hedges’ g = 0.18, and for pets t(39) = 0.51, p = .61, Hedges’ g = 0.16. Girls’ ratings of sibling positivity were also similar in the low and high adversity groups, t(34) = 0.92, p = .37, Hedges’ g = 0.30; however, girls experiencing a high level of adversity reported higher levels of positivity with a pet than girls experiencing low levels of adversity, t(34) = −2.89, p = .007, Hedges’ g = 0.95.

How do sibling and pet positivity contribute to children’s problem behavior?

At both time points, sibling but not pet positivity was inversely associated with mothers’ ratings of problem behavior (see ). To examine whether this inverse association persisted when effects of gender, adversity, and parent-child relationship were controlled, we conducted two regression analyses predicting Time 1 and Time 2 SDQ total difficulties scores (see ). In the first analysis we entered gender, adversity, and mother-child relationship quality scores into the first step of the regression model: these variables together accounted for 20.1% of the variance in Time 1 problem behavior, and both adversity (B = 3.45, 95% CI [0.85, 6.06], SE = 1.31, ß = 0.29, p = .010) and mother-child relationship quality (B = −3.29, 95% CI [–6.43, −0.15], SE = 1.57, ß = −0.24, p = .040) predicted unique variance. Sibling positivity (B = −2.24, 95% CI [–3.77, −0.71], SE = 0.77, ß = −0.33, p = .005) and pet positivity (B = 1.06, 95% CI [–0.62, 2.75], SE = 0.84, ß = 0.14, p = .213) were then added into the model and this step contributed an additional 9% (p = .015) of variance in problem behavior. Variables representing the interaction between sibling positivity and adversity (B = −0.80, 95% CI [–3.76, 2.17], SE = 1.48, ß = −0.08, p = .466), and pet positivity and adversity (B = 1.20, 95% CI [–2.64, 5.05], SE = 1.92, ß = 0.13, p = .534) were included in a final step but did not predict any additional variance in total difficulties (ΔR2 = 0.01, p = .777).

Table 2. Hierarchical regression models predicting mothers’ reports of total difficulties on the SDQ at Time 1 and Time 2.

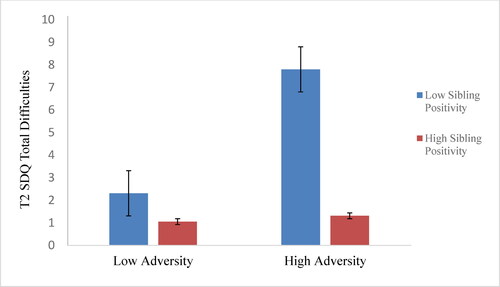

We then conducted similar analyses predicting SDQ total difficulties at Time 2. Gender, adversity, mother-child relationship quality and Time 1 problem behavior were included in the first step and together predicted 63.9% (p < .001) of the variance in mothers’ ratings of problem behavior at the second time point. Adversity (B = 3.12, 95% CI [0.72, 5.53] SE = 1.20, ß = 0.24, p = .012) and previous behavior problems (B = 0.70, 95% CI 0.49, 90], SE = 0.10, ß = 0.65, p < .001) each had unique effects in this model. In the second step of the model, sibling positivity (B = −1.99, 95% CI [–3.31, −0.68], SE = 0.65, ß = −0.27, p = .004), but not pet positivity, contributed a small but significant portion of additional variance (ΔR2 = 0.05, p = .012). Finally, we added sibling positivity by adversity and pet positivity by adversity interaction terms. This step of the model accounted for an additional 3.3% of variance (p = .045), and in this final model, the sibling positivity by adversity interaction term was significant (B = −2.87, 95% CI [–5.14, −0.59], SE = 1.13, ß = −0.26, p = .014). displays the interaction between sibling positivity and adversity. Simple slopes analysis showed that the regression slope was significant for low sibling positivity, B = 5.49, t(54) = 3.61, p = .001, but not high sibling positivity, B = 0.26, t(54) = 0.17, p = .87. That is, adversity was associated with higher maternal ratings of total difficulties only among children who had reported low levels of sibling positivity.

How do sibling and pet positivity contribute to children’s prosocial behavior?

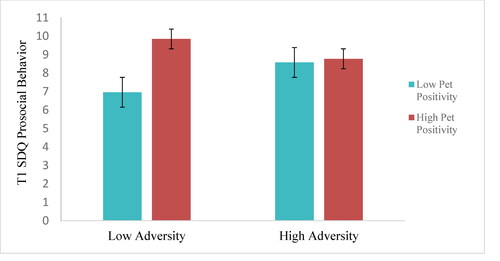

shows that Time 1 relationship positivity with pets and with siblings were each positively associated with mothers’ ratings of prosocial behavior at both time points. To examine whether sibling and pet positivity contributed unique variance to ratings of prosocial behavior we conducted two regression analyses predicting prosocial behavior at Time 1 and Time 2. For the first model predicting concurrent prosocial behavior, gender, adversity, and mother-child relationship quality were entered in the first step. Together, these variables accounted for 29.5% of the variance (p < .001) but only gender (B = −1.88, 95% CI [–2.87, −0.90] SE = 0.49, ß = −0.41, p < .001) and mother-child relationship quality (B = 1.35, 95% CI [0.23, 2.47], SE = 0.56, ß = 0.26, p = .019) were significant predictors of prosocial behavior. Sibling and pet positivity were then added into the model; these variables accounted for an additional 7.1% of the variance (p = .025) but only pet positivity was a unique predictor of prosocial behavior (B = 0.64, 95% CI [0.04, 1.25], SE = 0.30, ß = 0.22, p = .038). Pet positivity by adversity and sibling positivity by adversity interaction terms were entered in the final step (ΔR2 = 0.06, p = .035), which demonstrated a statistically significant interaction between pet positivity and adversity (B = −1.72, 95% CI [–3.03, −0.40], SE = 0.66, ß = −0.49, p = .038). A simple slopes analysis showed that the regression slope was significant for low pet positivity, B = 1.62, t(66) = 2.46, p = .02, but not high pet positivity, B = −1.08, t(66) = −1.54, p = 0.13. As depicted in , those with less positive pet relationships showed lower levels of prosocial behavior, but only in the low adversity context.

We then conducted similar analyses predicting prosocial behavior at Time 2 to test whether pet and sibling positivity contributed to prosocial behavior a year later, over and above the effects of concurrent behavior. In the first step, gender, level of adversity, mother-child relationship quality and Time 1 prosocial behavior together accounted for 64.1% of the variance (p < .001) in Time 2 maternal ratings of prosocial behavior, but only earlier prosocial behavior was a significant predictor (B = 0.69, 95% CI [0.51, 87], SE = 0.09, ß = 0.74, p < .001). Adding sibling and pet positivity into the model did not predict any additional variance (ΔR2 = 0.00, p = .864); adding in interaction terms between adversity and pet and sibling positivity also did not improve the model’s prediction (ΔR2 = 0.00, p = .710). The regression models for prosocial behavior are depicted in .

Table 3. Hierarchical regression models predicting mothers’ reports of prosocial behavior on the SDQ at Time 1 and Time 2.

We also ran these analyses predicting problem behavior and prosocial behavior using adversity as a continuous variable and found the same pattern of results, although the pet positivity by adversity interaction was not statistically significant (see Supplemental Materials).

Discussion

Our analyses yielded three main findings. First, a three-way interaction demonstrated that the impact of family adversity on relationship quality varied by both relationship type and child gender. Specifically, reports of pet (but not sibling) relationship positivity differed for girls experiencing high versus low levels of adversity, with girls experiencing high levels of adversity reporting especially positive relationships with their pets. In contrast, boys’ reports of relationship positivity (with either pets or siblings) did not vary by adversity levels. Second, at both time-points, parental ratings of children’s behavioral problems were significantly related to self-report measures of sibling positivity but were unrelated to self-reported positivity in relationships with pets. In contrast (at Time 1 only), positivity in children’s relationships with pets (but not siblings) explained unique variance in children’s prosocial behavior. Third, adversity predicted higher levels of problem behavior at Time 2, but only in the context of low sibling positivity. Positive sibling relationships had protective effects: adversity was unrelated to problem behavior for those who reported high levels of sibling positivity. Adversity was unrelated to children’s prosocial behavior at either time point, but the association between positive pet relationships and concurrent prosocial behavior was restricted to low adversity contexts.

Children’s close relationships and adversity

In this demographically diverse sample of pre-adolescents, adversity was unrelated to sibling relationship positivity. This finding aligns with the results of prior work using parental income as an index of risk (Dunn et al., Citation1999), but contrasts with research using other measures of social disadvantage such as home environment (e.g. Kretschmer & Pike, Citation2009). Prior mixed findings may be attributed to how adversity was measured; our index of adversity encompassed responses from multiple informants, and was more comprehensive, reflecting the effects of cumulative risk. These results suggest that sibling relationships may be more resilient to adversity than parent-child and couple relationships (e.g. Dhondt et al., Citation2019; Neff & Karney, Citation2017), possibly because contextual risk factors are more likely to impact on parenting attitudes and practices rather than children’s “emotionally uninhibited” relationships with each other (Kretschmer & Pike, Citation2009).

Alternatively, the lack of contrast in sibling relationship quality for children experiencing low and high adversity may reflect competing spillover and compensatory processes between different families, or different types of adversity acting in tandem to produce a null effect. Children may compensate for adversity conferred by proximal parental processes such as maternal depression and parental neglect by developing close, positive relationships with siblings. For example, pre-adolescents tend to seek support from siblings to cope with interparental conflict (Jenkins et al., Citation1989). On the other hand, spillover effects of distal, contextual factors, such as household chaos may negatively affect relationship quality (Kretschmer & Pike, Citation2009). Another possibility is that the impact of adversity in early adolescence on sibling relationship quality is gradual in nature and so not discernible in the short-term. For example, in a study of low-income American families with children at risk for delinquency, family conflict during pre-adolescence predicted sibling relationship quality in adulthood (Pauldine et al., Citation2015).

In contrast with the results for siblings, our findings suggest that, for girls at least, pets may play a compensatory role in the context of adversity. Girls have scored higher than boys on pet attachment, affection and compassion in several studies of middle childhood and adolescence (e.g. Hawkins & Williams, Citation2017; Hirschenhauser et al., Citation2017; Kerns et al., Citation2017; Muldoon et al., Citation2019). Why might girls rather than boys seek out comfort from a pet in difficult circumstances? One explanation is that girls are more likely to seek out social support than boys in the face of adversity (e.g. Eschenbeck et al., Citation2007). More generally, adolescent girls tend to be more sociable, report better relationship quality with peers, and draw on social support more than boys (e.g. Colarossi, Citation2001; Ma & Huebner, Citation2008; Qu et al., Citation2021; Thomas & Daubman, Citation2001). Alternatively, parents may be more likely to share details of difficult circumstances with their daughters than with their sons, such that girls are more affected by adverse events than boys and so have a greater need for social support. Moreover, girls tend to be more vulnerable to stressors around puberty (Rudolph & Flynn, Citation2007; Zahn-Waxler et al., Citation2008). It is interesting, therefore, that girls experiencing high levels of adversity reported more pet positivity but did not differ from those experiencing relatively low levels of adversity in terms of sibling positivity. This finding may suggest that pets are seen as better confidants in the context of adversity because they provide non-judgmental companionship (e.g. Bonas et al., Citation2000) and emotional support when human support is lacking (Kerns et al., Citation2023). The companionship offered by pets may be particularly important for children in the context of family adversity because siblings are experiencing the same stressors as them and may not have the capacity to provide emotional support in addition to their own coping.

Children’s close relationships and adjustment

Our results indicated that, above and beyond the influence of mother-child relationship quality, sibling positivity in pre-adolescence is associated with fewer behavioral difficulties both concurrently and a year later. These results are consistent with previous research linking sibling relationship quality to behavioral adjustment (e.g. Kim et al., Citation2007; Pike et al., Citation2005). Processes such as social learning and colluding to undermine authority have been used to explain externalizing behavior and delinquency in siblings (e.g. Bullock & Dishion, Citation2002). In a similar way, siblings can be sources of support and companionship, and model and reinforce adaptive social behavior (Branje et al., Citation2004; Kim et al., Citation2007). Positive social experiences in sibling relationships can provide conjoint emotion regulation and serve as learning opportunities for self-regulation, which promotes adjustment and buffers against stress (Morgan et al., Citation2012).

We did not find an association between sibling positivity and prosocial behavior, although sibling relationship quality has been linked with prosocial behavior in younger samples (Pike & Oliver, Citation2017). This association, however, became weaker three years later as the younger siblings in the sample also transitioned to primary school and so became more exposed to peer influences (Pike & Oliver, Citation2017). Another posibility is that older children have fewer opportunities to demonstrate prosocial behavior, such as comforting, as younger siblings become older and more skilled at regulating their own emotions (Hughes et al., Citation2018). The link may also be exaggerated in studies that use parent reports for both sibling relationship positivity and prosocial behavior (e.g. Pike et al., Citation2005), as parents may conflate observations of sibling positivity and prosociality. Birth order and the age gap between siblings are also important to consider since older siblings, with better socio-cognitive skills, are more likely to show helping and caring behaviors (Hughes et al., Citation2018), and have shown unique protective effects in stressful contexts (Hughes et al., Citation2023).

We did, however, find concurrent associations between pet relationship positivity and prosocial behavior. Our findings support and extend previous research suggesting that positivity toward pets, rather than simple pet ownership, plays a role in reducing youth delinquency, and in increasing empathy and prosocial behavior (Jacobson & Chang, Citation2018). The strength of children’s pet attachment impacts how they treat their pets (Hawkins et al., Citation2022). Children with stronger attachments to their dog tend to display more positive and fewer negative behaviors toward their dog, and score higher on prosocial behaviors, and lower on behavioral problems (Hawkins et al., Citation2022). Caring for pets and forming attachment bonds with them gives children opportunities to think about others’ welfare and facilitates the development of “humane” attitudes and tendencies, such as empathy, compassion, and prosocial behavior (Hawkins & Williams, Citation2017).

The lack of a longitudinal association between pet positivity and prosocial behavior is consistent with previous literature. A study of British 8- to 12-year-olds showed that mothers reported that their children were significantly less “naughty” and more cooperative than non-dog-owning children when the family first got a dog but these differences between the two groups did not last at 6-month and 1-year follow up visits (Paul & Serpell, Citation1996). Pet positivity may affect children’s behavioral state rather than trait or tendency for prosocial behaviors over time. It is also possible that pet relationship quality is not as stable as sibling relationship quality over time, so early positivity doesn’t impact later outcomes.

In addition, we did not find any significant association between pet positivity and behavioral difficulties. Here, exisiting evidence has been mixed and of questionable quality (see Purewal et al., Citation2017 for a review). Our relationship quality measure did not consider negative and harmful interactions, which may be a more crucial indicator of adjustment problems than the absence of positivity. Indeed, animal cruelty in childhood and adolescence is associated with behavioral problems and is predictive of interpersonal violence in adulthood (Longobardi & Badenes-Ribera, Citation2019). Increases in self-esteem and social competence have been suggested as the mechanisms underlying the positive effects of pet ownership on reducing behavioral problems (Hergovich et al., Citation2002). Different types of social support serve different functions, so it is possible that companionship, disclosure, and satisfaction with relationship do not matter for problem behaviors. For example, affection from pets enhancing children’s self-importance and pride predicted lower anger retaliation in a sample of 8- to 13-year-old boys, but pet companionship and intimate disclosure were unrelated to this maladaptive conflict resolution strategy (Bryant & Donnellan, Citation2007). Furthermore, pets are not considered to be social role models in the same way as siblings or peers and therefore cannot reinforce deviant behavior in the same capacity.

Close relationships as a buffer against adversity

We found that pre-adolescents experiencing high levels of adversity had more behavioral problems a year later when the sibling relationship quality was poor. This is consistent with findings from the ALSPAC sample demonstrating that positive sibling relationships buffered against the negative impact of stressful life events on children’s internalizing problems in middle childhood (Gass et al., Citation2007). Similarly in a Dutch sample, while controlling for parent-child relationship quality, high sibling support was associated with reduced post-divorce externalizing problems in children of divorced parents (van Dijk et al., Citation2022). In other words, siblings can be an important source of support for children experiencing stress and living in adversity.

Attachment theory assigns a dominant role to children’s relationship with their parents, because parents provide a secure base in stressful situations (Bowlby, Citation1982). When children lack parental support, however, siblings may act as sources of comfort and security (Gass et al., Citation2007). For example, in a study of British pre-adolescents, positive sibling relationships attenuated the negative impact of marital conflict on children’s emotional and behavioral problems (Jenkins & Smith, Citation1990). The present study extends these findings on the protective effects of sibling positivity for pre-adolescents to suggest that sibling relationships can also confer resilience in the face of cumulative adversity.

After accounting for the quality of children’s relationships with mothers, siblings, and pets, adversity was unrelated to prosocial behavior in our sample. Nevertheless, the concurrent association between positive pet relationships and prosocial behavior was only evident in the context of low adversity. When adversity was high, there was no difference in mean levels of prosocial behavior between pre-adolescents with contrasting levels of positivity in pet relationships. The influence of adversity may differ across various subtypes of prosocial behavior (Eisenberg et al., Citation2015; Larson & Moses, Citation2017). Equally, the buffering effects of pet positivity may only manifest in acute stressful situations (e.g. Kerns et al., Citation2018), through physiological mechanisms such as reduction in cortisol and activation of the oxytocin system (Beetz, Julius, et al., Citation2012; Beetz, Uvnäs–Moberg, et al., Citation2012), rather than being protective in contexts of chronic stress due to adversity. Our findings extend and qualify previous research on the positive effects of pet attachment (e.g. Hawkins et al., Citation2022).

Strengths, limitations, and future directions

This study has several notable strengths. To our knowledge, it is the first to directly compare how relationships with pets and siblings vary in the context of adversity, and how these relationships contribute to children’s adjustment. In doing so this study responds to calls within the HAI community to investigate pet relationships as they relate to human relationships (Melson, Citation2011), and expands the scope of both the developmental psychology and HAI literature on children’s close relationships. Second, unlike previous research using single measures of social disadvantage this study employed a multi-measure, multi-informant index of adversity that allowed us to examine how the combined effects of different types of social risk impact children’s close relationships. Third, this study increased the rigor of existing research on pet relationships and adjustment by examining these links longitudinally.

Several study limitations also deserve note. First, time and resource constraints at the second time point precluded assessment of children’s relationship positivity with pets and siblings at both time points. As a result, there could be differences in the relative stability of children’s reports of their relationship with their sibling versus their pet that may have important implications for their adjustment. Second, to ensure directly comparable measures of relationship positivity with siblings and pets we only analyzed one child’s view of the sibling relationship. Although, there is usually a reasonable degree of congruence between siblings’ reports of their relationship, these perspectives are by no means identical, and may have different implications for adjustment (e.g. Howe et al., Citation2010). However, our focus on the child’s perspective of the relationship is justified in the sense that the child’s own perception of their close relationships are likely to be particularly important for their adjustment (e.g. Harold et al., Citation2007). Third, our study lacked the power to assess whether links between relationship quality and adversity or adjustment vary for different pet types (e.g. Daly & Morton, Citation2003), or for sibling dyads with different gender or age-gap compositions. Future studies should consider birth order effects in these associations (e.g. Hughes et al., Citation2023). Given that parents often cite instilling responsibility in children as a reason for getting a pet (Charmaraman et al., Citation2022; Fifield & Forsyth, Citation1999), it would also be valuable for future research to account for children’s level of responsibility and involvement in caring for their pet when examining these associations. Fourth, the internal consistency of the Total Difficulties variable at T1 and pet positivity was relatively low in this sample. Future research should examine whether the pattern of associations found using the overall aggregate scores replicates for each subscale of these measures. Finally, the design of the study precludes any conclusions regarding causality.

Conclusion

Taken together, our findings suggest that although children may give similar ratings of their sibling and pet relationships, variation in these two relationships are linked to children’s adjustment and family circumstances in different ways. Importantly, both relationships make independent and unique contributions to different child outcomes, over and above parent-child relationship quality, echoing findings from previous studies examining the relative contribution of different relationships to children’s adjustment (e.g. Harper et al., Citation2014). Girls experiencing high levels of adversity report more pet positivity. Furthermore, pet relationship positivity is positively related to pre-adolescents’ concurrent prosocial behavior in low adversity contexts. Children experiencing different levels of adversity did not differ in how they rated sibling relationship positivity. However, children with high levels of sibling positivity showed resilience, such that the association between adversity and later behavioral problems was only evident for those with low levels of sibling positivity. Positivity in relationships with pets and with siblings makes unique contributions to behavioral outcomes in pre-adolescence.

Theorists have called for interventions that enhance parents’ functioning to promote positive outcomes for vulnerable children (Shonkoff & Fisher, Citation2013). Our findings suggest that the scope of such interventions could be widened horizontally to encompass other family relationships, including sibling and pet relationships to enhance adjustment and foster resilience in children experiencing adversity.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (20.9 KB)Acknowledgements

This study was funded by grants from the ESRC (ES/J005215/1) and the Waltham Foundation (W04-27270) (Funder ID 188613). We thank the families who participated in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data are available on request from the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ainsworth, M. (1989). Attachments beyond infancy. The American Psychologist, 44(4), 709–716. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.44.4.709

- Bandura, A. (1971). Social learning theory. General Learning Press.

- Bank, S., & Kahn, M. D. (1982). Intense sibling loyalties. In M. Lamb & B. Sutton-Smith (Eds.), Sibling relationships: Their nature and significance across the lifespan (pp. 251–266) Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Barlow, M. R., Hutchinson, C. A., Newton, K., Grover, T., & Ward, L. (2012). Childhood neglect, attachment to companion animals, and stuffed animals as attachment objects in women and men. Anthrozoös, 25(1), 111–119. https://doi.org/10.2752/175303712X13240472427159

- Beck, A., Ward, C., Mendelson, M., Mock, J., & Erbaugh, J. (1961). An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 4(6), 561–571. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004

- Beetz, A., Julius, H., Turner, D., & Kotrschal, K. (2012). Effects of social support by a dog on stress modulation in male children with insecure attachment. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 352. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00352

- Beetz, A., Uvnäs–Moberg, K., Julius, H., & Kotrschal, K. (2012). Psychosocial and psychophysiological effects of human-animal interactions: The possible role of oxytocin. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 234. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00234

- Bonas, S., McNicholas, J., & Collis, G. M. (2000). Pets in the network of family relationships: An empirical study. In A. L. Podberscek, E. S. Paul & J. Serpell (Eds.), Companion animals and us: Exploring the relationships between people and pets (pp. 209–236) Cambridge University Press.

- Bowes, L., Wolke, D., Joinson, C., Lereya, S. T., & Lewis, G. (2014). Sibling bullying and risk of depression, anxiety, and self-harm: A prospective cohort study. Pediatrics, 134(4), e1032–e1039. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-0832

- Bowlby, J. (1982). Attachment: Second Edition. Basic Books.

- Boyce, W., Torsheim, T., Currie, C., & Zambon, A. (2006). The family affluence scale as a measure of national wealth: Validation of an adolescent self-report measure. Social Indicators Research, 78(3), 473–487. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-005-1607-6

- Branje, S. J. T., van Lieshout, C. F. M., van Aken, M. A. G., & Haselager, G. J. T. (2004). Perceived support in sibling relationships and adolescent adjustment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(8), 1385–1396. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00332.x

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). Contexts of child rearing: Problems and prospects. American Psychologist, 34(10), 844–850. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.844

- Bryant, B. K., & Donnellan, M. B. (2007). The relation between socio-economic status concerns and angry peer conflict resolution is moderated by pet provisions of support. Anthrozoös, 20(3), 213–223. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279307X224764

- Buist, K. L., Deković, M., & Prinzie, P. (2013). Sibling relationship quality and psychopathology of children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(1), 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.10.007

- Bullock, B. M., & Dishion, T. J. (2002). Sibling collusion and problem behavior in early adolescence: Toward a process model for family mutuality. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 30(2), 143–153. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014753232153

- Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., Thornton, A., Freedman, D., Amell, J. W., Harrington, H., Smeijers, J., & Silva, P. A. (1996). The life history calendar: A research and clinical assessment method for collecting retrospective event-history data. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 6(2), 101–114. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1234-988X(199607)6:2<101::AID-MPR156>3.3.CO;2-E

- Cassels, M. T., White, N., Gee, N., & Hughes, C. (2017). One of the family? Measuring young adolescents’ relationships with pets and siblings. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 49, 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2017.01.003

- Charmaraman, L., Cobas, S., Weed, J., Gu, Q., Kiel, E., Chin, H., Gramajo, A., & Mueller, M. K. (2022). From regulating emotions to less lonely screen time: Parents’ qualitative perspectives of the benefits and challenges of adolescent pet companionship. Behavioral Sciences (Basel, Switzerland), 12(5), 143. Article 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12050143

- Cohen, S. P. (2002). Can pets function as family members? Western Journal of Nursing Research, 24(6), 621–638. https://doi.org/10.1177/019394502236636

- Colarossi, L. G. (2001). Adolescent gender differences in social support: Structure, function, and provider type. Social Work Research, 25(4), 233–241. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/25.4.233

- Currie, C. L. (2006). Animal cruelty by children exposed to domestic violence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 30(4), 425–435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.10.014

- Daly, B., & Morton, L. L. (2003). Children with pets do not show higher empathy: A challenge to current views. Anthrozoös, 16(4), 298–314. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279303786992026

- Dhondt, N., Healy, C., Clarke, M., & Cannon, M. (2019). Childhood adversity and adolescent psychopathology: Evidence for mediation in a national longitudinal cohort study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 215(3), 559–564. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.108

- Duncan, A., Thomas, J. C., & Miller, C. (2005). Significance of family risk factors in development of childhood animal cruelty in adolescent boys with conduct problems. Journal of Family Violence, 20(4), 235–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-005-5987-9

- Dunn, J., Deater-Deckard, K., Pickering, K., Golding, J., The, A., & Study, T. (1999). Siblings, parents and partners: Family relationships within a longitudinal community study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 40(7), 1025–1037. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00521

- Dunn, J., Slomkowski, C., & Beardsall, L. (1994). Sibling relationships from the preschool period through middle childhood and early adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 30(3), 315–324. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.30.3.315

- Eisenberg, N., Eggum-Wilkens, N. D., & Spinrad, T. L. (2015). The development of prosocial behavior. In D. A. Schroeder & W. G. Graziano (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of prosocial behavior (pp. 114–136). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195399813.001.0001

- Ensor, R., Marks, A., Jacobs, L., & Hughes, C. (2010). Trajectories of antisocial behavior towards siblings predict antisocial behavior towards peers. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 51(11), 1208–1216. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02276.x

- Eschenbeck, H., Kohlmann, C.-W., & Lohaus, A. (2007). Gender differences in coping strategies in children and adolescents. Journal of Individual Differences, 28(1), 18–26. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-0001.28.1.18

- Evans, G. W., Li, D., & Whipple, S. S. (2013). Cumulative risk and child development. Psychological Bulletin, 139(6), 1342–1396. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031808

- Fifield, S. J., & Forsyth, D. K. (1999). A pet for the children: Factors related to family pet ownership. Anthrozoös, 12(1), 24–32. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279399787000426

- Fraley, R. C., & Tancredy, C. M. (2012). Twin and sibling attachment in a nationally representative sample. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(3), 308–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211432936

- Furman, W., & Buhrmester, D. (1985). Children’s perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology, 21(6), 1016–1024. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.21.6.1016

- Gadomski, A., Scribani, M. B., Tallman, N., Krupa, N., Jenkins, P., & Wissow, L. S. (2022). Impact of pet dog or cat exposure during childhood on mental illness during adolescence: A cohort study. BMC Pediatrics, 22(1), 572. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-022-03636-0

- Gass, K., Jenkins, J., & Dunn, J. (2007). Are sibling relationships protective? A longitudinal study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 48(2), 167–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01699.x

- Goodman, R. (1997). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 38(5), 581–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x

- Goodman, R. (2001). Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(11), 1337–1345. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015

- Harold, G., Aitken, J., & Shelton, K. (2007). Inter-parental conflict and children’s academic attainment: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 48(12), 1223–1232. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01793.x

- Harper, J. M., Padilla-Walker, L. M., & Jensen, A. C. (2014). Do siblings matter independent of both parents and friends? Sympathy as a mediator between sibling relationship quality and adolescent outcomes. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 26(1), 101–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12174

- Harter, S. (1982). The perceived competence scale for children. Child Development, 53(1), 87–97. https://doi.org/10.2307/1129640

- Hawkins, R. D., McDonald, S. E., O'Connor, K., Matijczak, A., Ascione, F. R., & Williams, J. H. (2019). Exposure to intimate partner violence and internalizing symptoms: The moderating effects of positive relationships with pets and animal cruelty exposure. Child Abuse & Neglect, 98, 104166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104166

- Hawkins, R. D., Robinson, C., & Brodie, Z. P. (2022). Child–dog attachment, emotion regulation and psychopathology: The mediating role of positive and negative behaviors. Behavioral Sciences, 12(4), 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12040109

- Hawkins, R. D., Williams, J. M. (2017). Childhood attachment to pets: Associations between pet attachment, attitudes to animals, compassion, and humane behaviour. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(5), 490. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14050490

- Hergovich, A., Monshi, B., Semmler, G., & Zieglmayer, V. (2002). The effects of the presence of a dog in the classroom. Anthrozoös, 15(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279302786992775

- Hetherington, E. M. (1988). Parents, children and siblings: Six years after divorce. In R. A. Hinde & J. Stevenson-Hinde (Eds.), Relationships within families: Mutual influences. Oxford University Press.

- Hirschenhauser, K., Meichel, Y., Schmalzer, S., & Beetz, A. M. (2017). Children love their pets: Do relationships between children and pets co-vary with taxonomic order, gender, and age? Anthrozoös, 30(3), 441–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2017.1357882

- Howe, N., Ross, H. S., & Recchia, H. (2010). Sibling relations in early and middle childhood. In P. K. Smith, & C. H. Hart (Eds.), The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of childhood social development (pp. 356–372). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444390933.ch19

- Hughes, C. (2011). Social understanding and social lives: From toddlerhood through to the transition to school. Psychology Press.

- Hughes, C., McHarg, G., & White, N. (2018). Sibling influences on prosocial behavior. Current Opinion in Psychology, 20, 96–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.08.015

- Hughes, C., Ronchi, L., Foley, S., Dempsey, C., & Lecce, S. (2023). Siblings in lockdown: International evidence for birth order effects on child adjustment in the Covid-19 pandemic. Social Development, 32(3), 849–867. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12668

- Iacobucci, D., Posavac, S. S., Kardes, F. R., Schneider, M. J., & Popovich, D. L. (2015). The median split: Robust, refined, and revived. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 25(4), 690–704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2015.06.014

- Jacobson, K. C., & Chang, L. (2018). Associations between pet ownership and attitudes toward pets with youth socioemotional outcomes. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2304. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02304

- Jalongo, M. R. (2021). Pet keeping in the time of COVID-19: The canine and feline companions of young children. Early Childhood Education Journal, 51, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01251-9

- Jenkins, J. M., & Smith, M. A. (1990). Factors protecting children living in disharmonious homes: Maternal reports. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 29(1), 60–69. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199001000-00011

- Jenkins, J. M., Smith, M. A., & Graham, P. J. (1989). Coping with parental quarrels. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 28(2), 182–189. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-198903000-00006

- Johnson, J. P., Garrity, T. F., & Stallones, L. (1992). Psychometric evaluation of the Lexington Attachment to Pets Scale (LAPS). Anthrozoös, 5(3), 160–175. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279392787011395

- Keeton, C. P., Teetsel, R. N., Dull, N. M. S., & Ginsburg, G. S. (2015). Parent psychopathology and children’s psychological health: Moderation by sibling relationship dimensions. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43(7), 1333–1342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-015-0013-z

- Kerns, K. A., Dulmen, M. H. M., Kochendorfer, L. B., Obeldobel, C. A., Gastelle, M., & Horowitz, A. (2023). Assessing children’s relationships with pet dogs: A multi-method approach. Social Development, 32(1), 98–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12622

- Kerns, K. A., Klepac, L., & Cole, A. (1996). Peer relationships and preadolescents’ perceptions of security in the child-mother relationship. Developmental Psychology, 32(3), 457–466. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.32.3.457

- Kerns, K. A., Koehn, A. J., van Dulmen, M. H. M., Stuart-Parrigon, K. L., & Coifman, K. G. (2017). Preadolescents’ relationships with pet dogs: Relationship continuity and associations with adjustment. Applied Developmental Science, 21(1), 67–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2016.1160781

- Kerns, K. A., Stuart-Parrigon, K. L., Coifman, K. G., van Dulmen, M. H. M., & Koehn, A. (2018). Pet dogs: Does their presence influence preadolescents’ emotional responses to a social stressor? Social Development, 27(1), 34–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12246

- Kertes, D. A., Liu, J., Hall, N. J., Hadad, N. A., Wynne, C. D. L., & Bhatt, S. S. (2017). Effect of pet dogs on children’s perceived stress and cortisol stress response. Social Development, 26(2), 382–401. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12203

- Kim, J.-Y., McHale, S. M., Crouter, A. C., & Osgood, D. W. (2007). Longitudinal linkages between sibling relationships and adjustment from middle childhood through adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 43(4), 960–973. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.4.960

- Kretschmer, T., & Pike, A. (2009). Young children’s sibling relationship quality: Distal and proximal correlates. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 50(5), 581–589. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02016.x

- Lago, D., Kafer, R., Delaney, M., & Connell, C. (1987). Assessment of favorable attitudes toward pets: Development and preliminary validation of self-report pet relationship scales. Anthrozoös, 1(4), 240–254. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279388787058308

- Larson, A., & Moses, T. (2017). Examining the link between stress events and prosocial behavior in adolescents: More ordinary magic? Youth & Society, 49(6), 779–804. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X14563049

- Longobardi, C., & Badenes-Ribera, L. (2019). The relationship between animal cruelty in children and adolescent and interpersonal violence: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 46, 201–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.09.001

- Luthar, S. S. (2015). Resilience in development: A synthesis of research across five decades. In D. Cicchetti, & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology (pp. 739–795). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470939406.ch20

- Ma, C. Q., & Huebner, E. S. (2008). Attachment relationships and adolescents’ life satisfaction: Some relationships matter more to girls than boys. Psychology in the Schools, 45(2), 177–190. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20288

- Masarik, A. S., & Conger, R. D. (2017). Stress and child development: A review of the Family Stress Model. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 85–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.05.008

- Masten, A. S. (2013). Risk and resilience in development. In P. D. Zelazo (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of developmental psychology, Vol. 2: Self and other (pp. 579–607). Oxford University Press.

- Matijczak, A., Yates, M. S., Ruiz, M. C., Santos, L. R., Kazdin, A. E., & Raila, H. (2023). The influence of interactions with pet dogs on psychological distress. Emotion, 24(2), 384–396. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0001256

- McHale, S. M., Whiteman, S. D., Kim, J.-Y., & Crouter, A. C. (2007). Characteristics and correlates of sibling relationships in two-parent African American families. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(2), 227–235. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.227

- Melson, G. F. (2011). Principles for human animal interaction research. In P. McCardle, S. McCune, J. Griffin & V. Maholmes (Eds.), How animals affect us (pp. 13–34). American Psychiatric Association.

- Milevsky, A., & Levitt, M. J. (2005). Sibling support in early adolescence: Buffering and compensation across relationships. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 2(3), 299–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405620544000048

- Moffitt, T. (2002). Contemporary teen aged mothers in Britain. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 43(6), 727–742. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00082

- Morgan, J. K., Shaw, D. S., & Olino, T. M. (2012). Differential susceptibility effects: The interaction of negative emotionality and sibling relationship quality on childhood internalizing problems and social skills. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40(6), 885–899. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-012-9618-7

- Morrow, V. (1998). My animals and other family 1: Children’s perspectives on their relationships with companion animals. Anthrozoös, 11(4), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279398787000526

- Mueller, M. K., King, E. K., Halbreich, E. D., & Callina, K. S. (2022). Companion animals and adolescent stress and adaptive coping during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anthrozoös, 35(5), 693–712. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2022.2027093

- Mueller, M. K., Richer, A. M., Callina, K. S., & Charmaraman, L. (2021). Companion animal relationships and adolescent loneliness during COVID-19. Animals, 11(3), 885. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11030885

- Muldoon, J. C., Williams, J. M., & Currie, C. (2019). Differences in boys’ and girls’ attachment to pets in early-mid adolescence. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 62, 50–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2018.12.002

- Murphy, J. L., Voorhees, E. V., O'Connor, K. E., Tomlinson, C. A., Matijczak, A., Applebaum, J. W., Ascione, F. R., Williams, J. H., & McDonald, S. E. (2022). Positive engagement with pets buffers the impact of intimate partner violence on callous-unemotional traits in children. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(19-20), NP17205–NP17226. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605211028301

- Neff, L. A., & Karney, B. R. (2017). Acknowledging the elephant in the room: How stressful environmental contexts shape relationship dynamics. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 107–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.05.013

- Paul, E. S., & Serpell, J. A. (1996). Obtaining a new pet dog: Effects on middle childhood children and their families. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 47(1-2), 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-1591(95)01007-6

- Pauldine, M. R., Snyder, J., Bank, L., & Owen, L. D. (2015). Predicting sibling relationship quality from family conflict: A longitudinal study from early adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Child and Adolescent Behaviour, 03(04), 231. https://doi.org/10.4172/2375-4494.1000231

- Pike, A., & Oliver, B. R. (2017). Child behavior and sibling relationship quality: A cross-lagged analysis. Journal of Family Psychology, 31(2), 250–255. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000248

- Pike, A., Coldwell, J., & Dunn, J. F. (2005). Sibling relationships in early/middle childhood: Links with individual adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology, 19(4), 523–532. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.523

- Purewal, R., Christley, R., Kordas, K., Joinson, C., Meints, K., Gee, N., & Westgarth, C. (2017). Companion animals and child/adolescent development: A systematic review of the evidence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(3), 234. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14030234

- Qu, W., Li, K., & Wang, Y. (2021). Early adolescents’ parent-child communication and friendship quality: A cross-lagged analysis. Social Behavior and Personality, 49(9), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.10697

- Rudolph, K. D., & Flynn, M. (2007). Childhood adversity and youth depression: Influence of gender and pubertal status. Development and Psychopathology, 19(2), 497–521. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579407070241

- Shonkoff, J. P., & Fisher, P. A. (2013). Rethinking evidence-based practice and two-generation programs to create the future of early childhood policy. Development and Psychopathology, 25(4 Pt 2), 1635–1653. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579413000813

- Stauffacher, K., & DeHart, G. B. (2006). Crossing social contexts: Relational aggression between siblings and friends during early and middle childhood. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 27(3), 228–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2006.02.004

- Stoneman, Z., Brody, G. H., Churchill, S. L., & Winn, L. L. (1999). Effects of residential instability on Head Start children and their relationships with older siblings: Influences of child emotionality and conflict between family caregivers. Child Development, 70(5), 1246–1262. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00090

- Strand, E. B. (2004). Interparental conflict and youth maladjustment: The buffering effects of pets. Stress, Trauma, and Crisis, 7(3), 151–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/15434610490500071

- Thomas, J. J., & Daubman, K. A. (2001). The relationship between friendship quality and self-esteem in adolescent girls and boys. Sex Roles, 45(1/2), 53–65. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1013060317766

- UK Pet Food. (2023, March 22). UK pet population. https://www.ukpetfood.org/information-centre/statistics/uk-pet-population.html

- van Dijk, R., van der Valk, I. E., Buist, K. L., Branje, S., & Deković, M. (2022). Longitudinal associations between sibling relationship quality and child adjustment after divorce. Journal of Marriage and Family, 84(2), 393–414. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12808

- Westgarth, C., Boddy, L. M., Stratton, G., German, A. J., Gaskell, R. M., Coyne, K. P., Bundred, P., McCune, S., & Dawson, S. (2013). Pet ownership, dog types and attachment to pets in 9–10 year old children in Liverpool, UK. BMC Veterinary Research, 9(1), 102. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-6148-9-102

- White, N., & Hughes, C. (2017). Why siblings matter: The role of brother and sister relationships in development and well-being. Routledge.

- Zahn-Waxler, C., Shirtcliff, E. A., & Marceau, K. (2008). Disorders of childhood and adolescence: Gender and psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 4(1), 275–303. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091358