Abstract

This article describes my recent carved wood sculptures of warrior women as a response to and reimagination of historical and mythological accounts of Amazons. I emphasize aspects of queerness and gender non-conformity in the figurative sculptures through iconographical details. This body of work is grounded in readings of classical mythology and popular culture, as well as reference to historical Amazons and women warriors in African and Indian cultures.

Introduction

As a sculptor of icons, goddesses and wondrous women, I have been called a scavenger for the heroines of humanity and my current project is no different. My interest in Amazons as a subject for research and concurrent art project was sparked by seeing the painting “Wounded Amazon” by Franz von Stuck in the Harvard Art Museum (von Stuck, Citation1905). I found it hard to imagine a warrior fighting naked. The use of gratuitous nudity is incongruous with the portrayal of a powerful mythic warrior woman such as an Amazon. In Von Stuck’s treatment, Amazons’ bodies are objectified and evident products of the male gaze (Mulvey, Citation1975, p. 11). This imagery perpetuates harmful gender stereotypes and romanticizes problematic ideas about women’s agency, intelligence and power (Duncan, Citation1994, p. 109). It brings into question the intention of the artist who made this painting. What if a woman had made the painting about her own Amazon foremothers?

While an academic scholar contributes knowledge to the field of feminist art through research, writing, dialogue and publication, as an artist and wood carver I translate knowledge into sculptures. In a similar vein, Judy Chicago, for her work entitled “Dinner Party,” researched the names of mythic and historical women—warriors, artists, saints, goddesses, queens—and metaphorically seated them together at a table (Chicago, Citation1974-1979). She invited a community and a conversation that did not exist, and can never exist. Her combination of ceramic plates, tile floors, tablecloths, and woven tapestries brought to light women who had been forgotten or overlooked. The power of that installation lies in daring to imagine it, research it, and then create it.

In addition to the inspiration Chicago offers, my own feminist creations have been influenced by Women Who Run with the Wolves: Myths and Stories of the Wild Woman Archetype by Clarissa Pinkola Estes (Citation1992). The spirit of her book drives me to make challenging contemporary amazon archetypes. My project communicates a vision of the heroines we need now. My sculptures strive to be aspirational, futuristic, and transformative, while simultaneously building upon a foundation of powerful woman warriors throughout history.

My introduction to Wiccan pedagogies through Mary Daly’s Citation1990 book Gyn/ecology caused a profound shift for the development of my work. Authors often say: “I write the books I want to read.” I make the kind of art I want to see. I have been asked, “If you are so inspired by Egyptian art, why do you work in wood and not stone?” As a child, I spent a lot of time climbing trees. Among the highest branches, swaying in the wind, I felt connected to the tree, the earth, and the universe and at peace with myself. I started carving logs of Osage orange from my grandfather’s farm in Illinois. I have progressed to a variety of salvaged wood logs that my friends find and bring to me from around New England. Each piece of wood speaks to me in a different voice. I sculpt with a chainsaw and a belt sander as well as chisels, rasps, and files. The wood’s surfaces are smoothed out with sandpaper, colored with paint or pigment, and finished in varnish and wax. My pieces range from the intimate to the monumental. These iconic goddesses are crafted in the manner of fine woodworking. They are unique objects and each piece has a forceful presence.

Background

My use of animal-headed female figures connects with many art historical traditions from Egyptian, Indian, Mexican, and indigenous to contemporary American cartoons. In patriarchal societies, women are often severed psychologically from our own bodies. Therefore, visual representations of women embracing their animal natures is a feminist proposition. My work seeks to depict goddesses, warriors and wonder women that are not subject to the male gaze.

My 2009 Elephant sculptures were inspired by female heads of state—Margaret Thatcher, Indira Gandhi, and Madame Chiang Kai-shek. The figures evolved into a community of matriarchs. As I developed this series, I was pondering why the United States has never had a female president. My meditation on this glaring societal omission led me to create “Madam President,” measuring 15 ft tall. My presidential monument imagines a mythical woman president, “Madam President: A Monument to the First Female President of the USA and to the Dream that Every Girl Can Become the President of the USA.” “Madam President” has a lioness head since they are the apex predator of the African continent and female lions do most of the hunting in their family group. My sculpture has pink gloves that imply the elegance of a head of state, and green hair because any woman who has the role will be “green” or new and she will bear the groundbreaking work of being the first.

My 2012 bird series, “Flock Together,” was a riff on Marija Gimbutas’ Citation1989 book, The Language of the Goddess: Unearthing the Hidden Symbols of Western Civilization. I used an ancient bird-headed fertility goddess symbol to interpret contemporary fairy tales such as “Little Red Riding Hood,” “Little Match Girl,” “Cinderella,” and “Mother Hen.” One of my bird-headed women was a Cardinal, as if women could hold the sacred rank of a “Cardinal” in the Catholic Church.

In 2016, fascinated by Ai Wei Wei’s touring series, “Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads,” I was moved to create female goddesses interpreting the twelve figures of the Chinese Zodiac (Weiwei, Citation2010). I then added twelve interpretations of the Western Zodiac, to challenge the universality of the primarily male gendered gods associated with the constellations for which the astrological signs are named.

In 2018, I created “Match of the Matriarchs,” an all-female life-sized chess set that considers the game of chess as a metaphor for global dialogues about women and the ways they wield power. The exhibit featured my mysterious animal-human hybrid wood figures configured as a chess set. Inspired by the history of ship prow carvings, I reimagined a series of stereotypically hypersexualized mermaid figures as powerful matriarchs. The deep-sea battle between the squid and the whale informed my decision to create opposing teams of the cephalopods—octopus, squid and cuttlefish—facing the cetaceans—orca, narwhal and elephant seal—on the chessboard. Historically, the chess set was composed of a King, general, infantrymen, foot soldiers and mounted male military figures. The queen appeared in the game as early as the tenth century, but in the 16th century, the queen piece’s rewritten rules transformed her from the weakest to the most powerful piece, comprising a new iteration of the game pejoratively called “Madwoman’s Chess.” My chess set subverts the traditional vocabulary of the game figures and replaces the male-centric and gender-neutral terminology of the chess set with battling matriarchies.

The Amazons

I began my Amazon project during Covid, in 2020, as the world began to feel more apocalyptic. I imagined reconceptualizing Albrecht Durer’s “Four Horsemen,” from the Apocalypse series, as Amazon Warriors (Durer, Citation1498). Durer’s “Four Horsemen” are allegories of the plagues themselves, but my four warrior women sculptures embody the heroines we need now to battle the contemporary woes facing humanity. The year 2021 marked the trifecta of America’s most famous superheroine Wonder Woman’s 80th birthday, the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage in this country, and the inauguration of America’s first woman Vice President who is also of Black Caribbean and South Asian heritage. These historic milestones for women were in the air as I developed the ideas for my Amazons.

Also appearing at this time was a tide of live-action films centered around fictional women warriors, including Black Panther (Citation2018), Wonder Woman 1984 (Citation2020), Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (Citation2022) and Woman King (Citation2022). These cinematic women characters were very influential in the creation of the first three sculptures in this series, Alpha Female, Black Panther and Cybele. Alongside these fictional Amazons, real-life women warriors fueled my work.

While researching the Amazons and historically renowned women warriors from around the world, I saw two live action films that brought an historic heroine into our contemporary lives: Manikarnika, The Queen of Jhansi (Citation2019) and The Warrior Queen of Jhansi (Citation2019). I expanded my “Amazon” series to include Lakshmibai, as she is also called, the Rebel Queen of Jhansi (India) who challenged the British East India Trading Company’s colonial rule and united her nation in 1857.

I had the impression that the Amazons were mighty women warriors, yet in a classical or academic sense, the Greek and Roman myths and corresponding images often portray the Amazons as being defeated. For example, the “Marble statue of a wounded Amazon, Citation32.11.4” in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art is monumental, but instead of showing her fighting and victorious, she is shown with blood dripping down her side from a wound. This is not an inspiring image. Where are the Amazon victors?

Given that the Greek and Roman Amazons were portrayed as mighty warriors who were often defeated, I wanted to imagine a series of woman warriors who were triumphant pioneers and military strategists alongside being lovers, wives, mothers, and daughters. Arguably, women’s studies has brought many examples of these women from history to light, and in more recent years even to mainstream children’s books, movies, graphic novels, and TV shows, yet still we don’t hear enough of these stories; they are still on the margins of mainstream historical narratives and popular culture. As an artist I seek to center these fictional and historical women warriors through my gallery and museum shows and public art. This body of work is specifically intended for art galleries, but I also see these figures as potential small scale models for public monuments that could reach a wider audience, engage historical narratives, and provide visual representation for the heroines that we need now.

The iconography of the warrior suits me. I fight battles all the time, even if not as in warfare with guns and weapons. My battles, living in a predominantly patriarchal culture, are political, psychological, emotional, and spiritual. As a sculptor, seeing the defeated Amazon provides the motivation to make victorious women warriors in my own wood sculptures.

Archaeology tells us that there have been women warriors in many cultures, which contradicts the narrative dichotomy of male hunter/female gatherer and gender superiority/inferiority associations that align strength and courage with men. This insight was of great significance for my sculpture series, “Amazons Among Us.”

Throughout history, many stories of battling heroines have been translated into art. Yet, I have found little satisfying scholarship on the real-life warriors of the ancient world who might have inspired the Greek and Roman Amazon myth and legends. With no written histories and no specific geographically-relevant archaeological results, their culture remains unresolved. With the goal of reimagining the Amazons as victorious warriors, as many women warriors in history were, I set about making my amazon warriors.

Used colloquially, an “Amazon” denotes a warrior-like woman, whose fighting prowess evokes the legendary Amazons. The word itself denotes a woman with physical strength, one who is in command, a masculine lesbian, or a gender non-conforming woman. The woodcarving that I do requires physical strength, creativity, and psychic stamina. Through my work, I relate to this lineage of women. Amazons have become synonymous with women warriors who have existed in many cultures around the world. They have inspired myths, legends, and some of the greatest art that survives from the ancient world. I see myself in these Amazons.

Women Warriors

As I researched the Amazons further, it became clear that the word has global context and meaning. For example, the global superpower “amazon.com,” derives its name from the Amazon River in South America (Hall, Citation2023, p. 1). The Amazon River or the “River of the Amazons” was given its name when the explorer Pedro de Magalhaes de Gandavo encountered a group of female warriors in Northeastern Brazil (Feinberg, Citation1996, p. 58). Notable women warriors who have inspired my own sculptures in this series include Lakshmibai and the Dahomey Amazons (Africa), an all-female military regiment which existed from the 1700s until the early 1900s (Toler, Citation2020, p. 184). Warrior women have always been with us, yet harmful gender stereotypes and misconceptions have prevented us from recognizing them. I wanted to create these “Amazons” among us, using wood, a traditional ancient art material, to insert myself into this global dialogue.

My artwork celebrates the mystical relationship between human beings and the animal kingdom. Through hybrid female-animal forms that I sculpt in wood, I flesh out sensuality, sexuality, and soul with a well-proportioned figurative vocabulary. The natural grain of the wood interacts with the form and shape of my sculptures in a descriptive way, suggesting nostrils and nipples or garments and fabric textures. I often stylize each piece to enhance the girl, woman, princess, queen, or goddess within. The mouths, or in some cases beaks, are closed to suggest the mysteries they embody. These figures are sculpted in sizes ranging from the intimate to the monumental. I use color in both subtle and bold ways to activate each piece. My inspiration comes from ancient iconography and mythological imagery.

From my position as a white European-American, my willingness to share and connect with a wide variety of colleagues comes from a place of vulnerability, curiosity, and humility. I believe a transcultural exchange widens the relevance of my work by bridging cultures and evoking empathy. By engaging with the work of Black, Brown, Middle Eastern and Asian artists and thereby bringing a wider range of art historical narratives to my predominantly white art audiences, I aim to draw more diverse audiences into my predominantly white academic and art worlds and invite critical engagement or dialogue that has the potential to move issues of race toward ever greater justice.

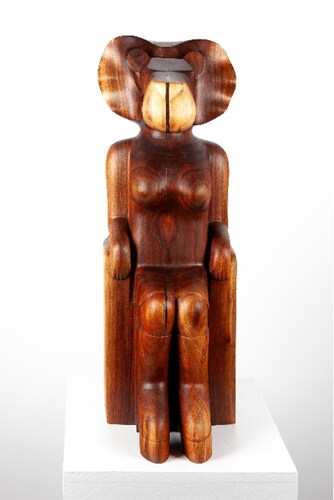

Alpha Female

I chose the title “Alpha Female” () for the first sculpture I created in my amazon series. Admittedly Alpha Male carries the meaning of a strong leader but also the negative implication of toxicity. My sculpture is created in contrast to this male trope. My “Alpha Female” is inspired by my Great Aunt, Major Martha Alice Pichon, the first born in her family, a first-generation college graduate who taught high school classes in Alpha, Illinois, a self-sufficient woman, and whose name began with “A,” the first letter in the alphabet. I use the title “Alpha Female” consciously and also conscientiously to mean that, in the case of my sculpture, the Alpha signifies power not aggression.

Figure 1. Alpha Female, 41” tall, spalted pear, oak, enamel, colored pencil, 2020. Photo credit: Brian Wilson.

The “Alpha Female” has an eagle head, serving as a patriotic symbol honoring Alice’s US military service. She wears shoes similar to those seen in historic photographs of women in uniform during World War II. Recalling Adrienne Mayor’s mention that the ancient Amazons had tattoos (Mayor, Citation2014, p. 95), I tattooed on this sculpture’s calf an image of Pallas Athena’s helmet. I also gave her metallic breast shields to celebrate the lineage of women warriors—referencing the classical depictions of Amazons and the goddess Pallas Athena herself—from ancient times to the present day.

Through my family, I am connected to the American history of women in the military. My Great Aunt Alice was a pioneer as one of the first 40 Illinois women officer enlistees in the Women’s Army Corps (WACs). As I studied the 1942 photo of her in uniform, I noticed that the pin on her lapel is a replica of Pallas Athena’s helmet. Oveta Culp Hobby, the first WAC director, who served from 1942 to 1945, was responsible for this choice of their insignia.

[When] [t]he Heraldic Section of the Quartermaster General’s Office … submitted designs for insignia … [they] produced … a busy-bee like insect, which Mrs. Hobby pronounced a bug, adding that she had no desire to be called Queen Bee. Designers then hit upon the idea of a head of Pallas Athene, a goddess associated with an impressive variety of womanly virtues and no vices either womanly or godlike. She was the goddess of handicrafts, wise in industries of peace and arts of war, also the goddess of storms and battle, who led through victory to peace and prosperity. (Treadwell, Citation1954, p. 39)

Women were recruited to serve in the military campaign in World War II to free up men to fight in combat, and it was a successful strategy that led to the USA victory. I would like to think that this was accomplished by Oveta Culp Hobby’s invocation of the Greek Goddess and Pallas Athena’s seal of approval on every one of our women in uniform.

In addition to her headdress, Pallas Athena is often portrayed in art history with breast plates or shields, as a sign of her warrior status. Two notable examples are the Athena statue by Carl Kundmann, located prominently outside the Austrian Parliament building in Vienna which references Phidias’ composition of Athena from the Parthenon and the figure of Athena painted on the Terracotta neck-amphora (jar) of Panathenaic shape ca. 520 B.C., attributed to the Antimenes Painter, held in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum (Accession Number: Citation06.1021.51).

Real-life women have not always received credit for their warrior status, even when their skeletons were found with weapons. As recently as 30 years ago, if a skeleton was found with weapons it was more often assumed to be male. Now archaeology uses modern DNA techniques which have proven the existence of women warriors (Davis-Kimball & Littleton, Citation1997). This discovery has changed existing narratives about human remains by casting doubt on previous assumptions and opening up new interpretations of ancient archaeological sites. For example, a gravesite that was found in 1878 misidentified the skeleton as male until 2017 when it was reassigned its proper status as a female warrior (Hedenstierna-Jonson et al., Citation2017, p. 854). Archaeological discoveries of female warriors imply that women warriors have existed since ancient times. It follows that women serving in combat is our rightful heritage, which is what my wood sculpture implies.

Black Panther and Cybele

The second and third sculptures in this series are “Black Panther” and “Cybele” (). In creating this pair, I decided that “Cybele” would be a lion-headed feline figure riding in a chariot, not a literal twin but an equal to “Black Panther,” as a feline-headed goddess seated on a throne. When adding the painted designs to “Black Panther” and “Cybele,” I made several deliberate choices based on my research and intentions; for example, instead of the Scythian axe often associated with the ancient Amazons, I drew a labrys symbol on “Cybele’s” chariot to represent lesbian feminism. The labrys is also associated with the Ancient Amazon Hippolyte. According to legend, Heracles took it from her (Plutarch and et al. Citation1927 Greek Questions 45 = Moralia 302a). I often quote the male features of animal heads on my female figures to signify gender non-conforming, transgender, and gender fluid characters. These anthropomorphic sculptures—half animal, half human—evoke the queerness or otherness of the Amazons.

Figure 3. “Black Panther,” 30” tall, black walnut and colored pencil, 2020. Photo credit: Brian Wilson.

I gave “Black Panther” and “Cybele” matching tattoos of a panther paw inside of a Venus symbol, an image that references the raised fist of the Black Panther Party and symbolizes Black power and resistance to oppression. The shape of the mane on “Black Panther” is reminiscent of the iconic hairstyle or afro of Angela Davis, a Brandeis alum, former Black Panther Party activist, and powerful Black lesbian. “Cybele’s” strong posture and ample stature evoke for me the figure of Octavia Butler, the mother of Afrofuturism, a gender non-conforming woman herself and another strong Black woman who lived by radical self-definition.

My sculptures present historic heroines as global players throughout human history. In the Afro-futuristic live-action film, Black Panther (2018), the fictional warrior women, Dora Milaje, were based on the historic Agojie, or Dahomey “Amazons.” Admittedly, the use of the word Amazon here derives from a Euro-centric colonial term for these real-life women warriors, which arguably makes this concept of powerful women warriors intelligible to a Western audience who might have been unfamiliar with them prior to seeing this feature film. Woman King (Citation2022), a recent historical fiction film explores the lives and narratives of the Dahomey Warriors and their role in the transatlantic slave trade. Note that the title of this film implies gender-bending, gender fluidity or gender non-conformity. These legendary warriors are the inspiration for a woman protagonist, my Black Panther.

More than five decades after the appearance of the first Black superhero in mainstream comics, the movie Black Panther (2018) was the first major studio film devoted to a black superhero. Likewise, the sequel, Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (Citation2022) features a Black superheroine nearly 50 years after the appearance of the first Black superheroines appeared in comics. In 2016, Ta-Nehisi Coates commissioned Roxane Gay to write a special issue of the Black Panther comic book, “World of Wakanda,” and she updated the comic book narratives and characters to include queer women (Gay, Citation2016). Gay wrote a story that centered two Dora Milaje (all-female special forces of Wakanda) lovers and moved the Black Panther character to the background of the story. But Gay’s revisionist and intellectual contributions to the comics did not make it into the Black Panther movie in 2018. This was a missed opportunity since comics and movies are often marketed heavily to young people whose gender identity and sexuality need validation in the form of visible role models. As an ally, I wanted to amplify Gay’s idea, so I decided to bring these two women lovers to life through my sculptures. As an aside, I will note that Gay’s idea of two Dora Milaje lovers did make it into the sequel Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, but only as a sub-plot, and furthermore, the Black Panther character is a woman in Wakanda Forever but she does not have a woman lover (yet).

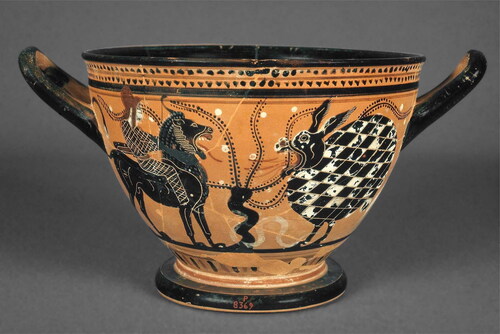

As I was puzzling over how to portray “Black Panther’s” lover, I discovered that the Amazons were often associated with Cybele, the mother of the Gods in Greek mythology. In my research at the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) in Boston, I came across a Drinking cup (skyphos) with a warrior riding a lion confronting a monster, by the ancient Greek Theseus Painter, from the Late Archaic Period, 515–500 B.C. () I learned from the description that the figure is an “Amazon with a bow case and bow who wears Phrygian cap and tights with a long-sleeved top. Her white skin identifies her as female.” The lion on this enigmatic and highly unusual cup made the connection for me between the Amazons and Cybele. In the Greek and Roman collection of the Boston MFA, I discovered three other compositions of a female figure riding a lion, all described as Cybele herself. (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Citation1972.45)

An older statue of a mother goddess titled “Seated Woman of Çatalhöyük,” is a Neolithic clay and ceramic artifact created in ca. 6000 BCE. Currently located in the collection of the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Turkey, this sculpture evokes the traditional composition of Cybele as a queen seated on a throne flanked by lions. Cybele is also portrayed in art history seated in a chariot pulled by the iconic pair of lions flanking her as seen in the Fountain of Cybele in Madrid, Spain. Whether on a throne or in a chariot, these art historic compositions gave me the idea to pair “Black Panther” with “Cybele” and to incorporate both the throne and the chariot in my compositions.

My “Black Panther” figure is also reminiscent of the single anthropomorphic figure of Sekhmet, a lion headed Egyptian goddess often portrayed seated on a throne. My introduction to Egyptian goddess figures was from an image I saw of Genevieve Vaughn’s commission for a temple dedicated to the Goddess Sekhmet in the journal SageWoman (Vaughn, Citation1998, p. 42).

In ancient Egyptian art, there is a religious pantheon of gods and goddesses that make up the mythology, and whose imagery resonates with me on a personal level. I create my own wood sculptures as spiritual icons, or personal totems that are infused with a personal mythology. My intent is to evoke something larger about goddesses or womankind.

I became very inspired by and interested in the visual language of animal-human hybrid goddesses in Egyptian art such as Sekhmet (a lion headed goddess figure) and Tauret (a hybrid hippo/lion/crocodile midwife goddess figure) who are strong yet sensual, primal yet refined, fierce yet beautiful. My art work is also inspired by the falcon-headed (Horus) baboon-headed (Hapi) and crocodile-headed (Sobek) Egyptian male gods. From them, I create female counterparts in the goddess figures.

My “Black Panther” and “Cybele” sculptures are created in a small scale, approx. 2-3 ft tall, but they have a large presence. They invite pause and careful looking in the viewer and they each exude a strong personality. Their body language and stature commands attention. This is how I imagine a victorious woman warrior would be represented.

Lakshmibai

For the fourth figure in this series, I chose Lakshmibai, The Rani (Queen) of Jhansi as my inspiration. When considering warriors, one does not often think of mothers. But The Rani of Jhansi (1828–1858) is one notable example of a mother warrior who became a national heroine fighting against the injustice of British colonial rule. The presence of a global feminine spirit in art was reinforced by my reading Robert Graves’, Citation1958 White Goddess, a work that untangles the riddles of poetry that disguise a fierce goddess presence, whose mystery underlies and explains a vital life force and system of belief. One of the archetypes that Graves discusses is called the White Sow, a fierce maternal presence. Anyone can imagine the ferocity with which a mother would guard her child. With this spirit in mind, I created Lakshmibai.

Lakshmibai was one of the leading figures of the Indian Rebellion of 1857 against British colonial powers. She became known as a symbol of resistance to the British Raj for uniting Indian nationalists. The dominant composition of her in Indian art history references a famous story that I chose to quote in my work: as the British were capturing her kingdom, she grabbed her son, tied him to her back, grabbed her sword and leapt off the castle wall onto the back of her horse and rode away. Women are often not thought to be important enough to be the subject of written histories, but Lakshmibai was resurrected, reinvented, and reinterpreted in literature, poetry, and song with every generation that came after her reign (Singh, Citation2015).

The Rani complicates traditional gender roles and narratives, not unlike the other women warriors I have mentioned in this article. One similarity between the Rani and the Dahomey is the all-female army regiment of the Indian National Army that was named after Lakshmibai. I felt a kinship to these women warriors as I created my all female army of wood sculptures. Furthermore, Vishṇubhatta Goḍaśe’s My Travels in the 1857 Rebellion, the one eyewitness account of the Rani’s revolt, makes mention of her wearing male clothing and exhibiting transmasculine habits (Godase, Citation2014, p. 74). In the famous poem by Subhadra Kumari Chauhan, taught in schools throughout India, the refrain “It was the Rani of Jhansi who fought with the valor of a man” evidences how her gender non-conforming performance informs her myth and lore (Singh, Citation2019 p. 26).

As a national heroine, the Rani of Jhansi has significant spiritual connections to India. She was named after Lakshmi, the Indian goddess associated with the lotus flower. This flower is a complicated symbol: in spite of its beautiful blossoms, a lotus can grow only in a swamp. In other words, it takes the grit born of harsh surroundings to create true beauty. I chose to use the pink lotus associated with the goddess Lakshmi as the image for her tattoo on her left arm. Her right arm holds her sword that is drawn from its sheath and poised to fight.

Lakshmibai’s fierce national pride and her fighting spirit evoke another important national symbol of India: the Bengal tiger, or Royal Bengal tiger (Panthera Tigris), a subspecies of tiger native to India, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Bhutan. This tiger has been a prominent symbol of India since about the 25th century BCE, when it was displayed on the Pashupati seal or early stone tablet that belonged to the Indus Valley civilization in South Asia. Thus, I chose to create a tiger-headed woman warrior to honor this powerful heroine.

Since Lakshmibai is both a historic figure and a folk legend of national importance to India, I used the color palette of the Indian flag in my composition: saffron, white, and green (). The wood I used suggests the saffron color of the flag. Her child, who is too old to need carrying, is bound to her back with a white sash, symbolizing the feeling of fleeing. Her shoes are painted green, like the bottom band of the Indian flag, representing her connection to her homeland. The blue dot at the center of her belt evokes the blue chakra wheel on the India Flag and signifies the globe, since she is heroine of global significance and connected to women warriors around the world.

Amazons Among Us

In 2021, I premiered a selection of my sculptures in a solo exhibition, Amazons Among Us (), at the Boston Sculptors Gallery in Massachusetts. That exhibition, the culmination of my research and art project, was met with critical acclaim (Amore, Citation2021; Foritano, Citation2021; McQuaid, Citation2021). Cate McQuaid notes that “Unlike Dürer’s threatening quartet, who hurtle toward societal destruction, these figures are rock steady and proud. It’s like a chapel dedicated to ferocious protection and love.” B. Amore situates the work in the contemporary moment,

Figure 6. Installation view of Amazons Among Us show at Boston Sculptors Gallery, Citation2021.

In this time of pandemic, there is a new recognition of the complex balancing act that is the reality of many women. On the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage, the artist’s striking exhibit, Amazons Among Us at Boston Sculptors Gallery, creates mythic figures that personify both historic and modern-day roles for women. The combination of ferocity and womanliness is a common theme (Amore, Citation2021).

Foritano underscores the living presence of the work:

I found action everywhere in the artist’s figures, especially in the limbs and hands where traditional mallet and chisel did more intimate figuration than power tools are capable of; also, in delicately penciled, discretely situated tattoos. And, surprisingly, for me, the views in back of these works are as arresting as the frontal poses of these Amazons, arresting in their grace, as if depth as well as readiness was inherent in every Amazon (Foritano, Citation2021).

Conclusion

Historically, the defeated Amazons were used to perpetuate the superiority of the Greek and Roman men over women. Now is the time to reimagine these ancient women warriors as heroines of the present moment as we fight our current battles, as for instance the 2017 Me Too Movement that unleashed the core energy of women’s sexual oppression by revealing the extent of sexual harassment and assault toward women. As a matter of representational justice, it is important to re-envision Amazons today.

Much of higher education in fine art and Western art history has traditionally ignored whole civilizations and canons of art, not to mention women makers. Although this has changed and vastly improved in the last 20 years, there is more work needed. If we reconsider myth, history, and image as forms of representation that speak to each other, I offer my own sculptures as powerful tools for intervening in myth-informed hegemonies of gender.

The implication and application of my creative engagements with classical Greek and Roman mythology as well as with women warriors in African and Indian cultures is that we might recognize ourselves in these sculptures. My hope is that we might engage with cultures and narratives that are unfamiliar. We deserve to know the stories of these heroines, and their stories deserve to be brought to light. My sculptures have the power to shift art historical dialogues to include goddess imagery, lesbian or same-sex eroticism, nontraditional gender performance, and superheroines/sheroes. These subjects, underrepresented in high art, frequently appear in so-called lowbrow culture or pop art—which begs, above all, for the transformation of high art. That is my goal in creating the “Amazons Among Us.”

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Walter Penrose, Jr. and Sarah Breitenfeld for co-organizing “Queer Representations and Receptions of Amazons” a Lambda Classical Caucus session at the Annual joint meeting of the Society for Classical Studies and the Archaeological Institute of America in 2022. Portions of this paper first appeared in my presentation “What Do We Call Courageous Women?”.

I am additionally appreciative of Walter Penrose Jr. for editing this special issue of the Journal of Lesbian Studies and of the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful and encouraging feedback. Any errors that remain are, of course, my own.

*Brandeis University Women’s Studies Research Center provided partial funding for my travel expenses related to my attendance at the 2022 joint meeting of the Society for Classical Studies and the Archaeological Institute of America.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Donna Dodson

Donna Dodson is an American sculptor based in Boston, MA. Currently she is a Scholar at the Brandeis University Women’s Studies Research Center, a visual arts Fellow at the St. Botolph Club in Boston and a former Fulbright US Scholar in Vienna Austria.

References

- Amore, B. (2021). Amazons among us: Sculpture by Donna Dodson. Art New England. https://artnewengland.com/amazons-among-us-sculpture-by-donna-dodson/.

- Bhise, S. (Director). (2019). The Warrior Queen of Jhansi [Film]. Cayenne Pepper Productions; Dune Films.

- Chicago, J. (1974–1979). The Dinner Party [Installation]. Brooklyn Museum, New York, NY. https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/exhibitions/dinner_party/

- Coogler, R. (Director). (2018). Black Panther [Film]. Marvel Studios.

- Coogler, R. (Director). (2022). Black Panther: Wakanda Forever [Film]. Marvel Studios.

- Daly, M. (1990). GYN/ecology, the metaethics of radical feminism: With a new intergalactic introduction. Beacon Press.

- Davis-Kimball, J., & Scott Littleton, C. (1997). Warrior women of the Eurasian Steppes. Archaeology, 50(1), 44–48.

- Dodson, D. (2021). Amazons Among Us [Exhibition]. Boston Sculptors Gallery, Boston, MA. https://www.bostonsculptors.com/artists#/donna-dodson/.

- Duncan, C. (1994). The aesthetics of power: Essays in the critical art history. Cambridge University Press.

- Durer, A. (1498). The Four Horsemen from “The Apocalypse“ [Woodcut]. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/336215

- Estes, C. P. (1992). Women who run with the wolves: Myths and stories of the wild woman archetype. Ballantine Books.

- Feinberg, L. (1996). Transgender warriors: Making history from Joan of Arc to RuPaul. Beacon Press.

- Foritano, J. (2021). “Donna Dodson’s Amazons among US & Andy Moerlein’s Wood Stone Poem at Boston Sculptors Gallery.” Artscope Magazine. https://artscopemagazine.com/2021/05/donna-dodsons-amazons-among-us-andy-moerleins-wood-stone-poem-at-boston-sculptors-gallery/

- Gay, R., Coates, T.-N., Richardson, A., & Martinez, A. (2016). Black Panther: World of Wakanda. Marvel Worldwide, Inc., a subsidiary of Marvel Entertainment, LLC.

- Gimbutas, M. A. (1989). The language of the goddess: Unearthing the hidden symbols of western Civilization (1st ed). Harper & Row.

- Godase, V., Krishnan, M., Adarkar, P., & Gokhale, S. (2014). Adventures of a Brahmin priest: My travels in the 1857 Rebellion. Oxford University Press.

- Graves, R. (1958). The White goddess: A historical grammar of poetic myth. Vintage Books.

- Hall, M. (2023). “Amazon.Com.” Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Amazoncom.

- Hedenstierna-Jonson, C., Kjellström, A., Zachrisson, T., Krzewińska, M., Sobrado, V., Price, N., Günther, T., Jakobsson, M., Götherström, A., & Storå, J. (2017). A female viking warrior confirmed by genomics. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 164(4), 853–860. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.23308

- Jagarlamudi, R. K., & Ranaut, K. (Directors). (2019). Manikarnika: The Queen of Jhansi [Film]. Zee Studios.

- Jenkins, P. (Director). (2020). Wonder Woman 1984 [Film]. Warner Bros. Pictures; DC Films; Atlas Entertainment; The Stone Quarry.

- Marble statue of a wounded Amazon, Roman, Imperial period, 1st–2nd century CE, Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York NY, Accession Number: 32.11.4

- Mayor, A. (2014). The Amazons: Lives and legends of warrior women across the ancient world. Princeton University Press.

- McQuaid, C. (2021). “Artists Call upon the Ancients at Boston Sculptors Gallery” The Boston Globe- BostonGlobe.com. https://www.bostonglobe.com/2021/05/25/arts/artists-call-upon-ancients-boston-sculptors-gallery/.

- Mulvey, L. (1975). Visual pleasure and narrative cinema. Screen, 16(3), 6–18. https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/16.3.6

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Plate with a woman (Cybele?) riding a lion, Greek, Classical period, late 5th century B.C. Place of Manufacture: Greece, Attica, Athens. Accession Number 10.187; Cybele riding a lion, Greek, Late Classical Period, about 400 B.C., Place of Manufacture: Greece, Boeotia, Thebes. Accession Number 03.918; Statuette of Cybele/Magna Mater wearing a mural crown and riding a lion, Roman Imperial Period about A.D. 200 Accession Number 1972.45.

- Plutarch, E. N O’Neil., et al. (1927). Moralia. Translated by Frank Cole Babbitt, Harold F. (Harold Fredrik) Cherniss, Paul A. Clement, Phillip De Lacy, Benedict Einarson, Harold North Fowler, W. C. (William Clark) Helmbold Harvard University Press.

- Prince-Bythewood, G. (Director). (2022). The Woman King [Film]. TriStar Pictures; Entertainment One.

- Singh, H. (2015). The Rani of Jhansi: Gender, history, and fable in India. Cambridge University Press.

- Singh, H. (2019). India’s Rebel Queen: Rani Lakshmibai and the 1857 Uprising. In B. Cothran, J. Judge, & A. Shubert (Eds.), Women warriors and national heroes (pp. 23–37). Bloomsbury Acade.

- Terracotta neck-amphora (jar) of Panathenaic shape, Greek, Attic, ca. 520 BCE, Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York NY, Accession Number:06.1021.51.

- Toler, P. D. (2020). Women warriors: An unexpected history. Beacon Press.

- Treadwell, M. E. (1954). United States army in World War II, Special Studies, the Women’s Army Corps. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Vaughn, G. (1998). My journey with Sekhmet Goddess of power and change. SageWoman, 12(Summer), 42–48.

- von Stuck, F. (1905). Wounded Amazon [Painting]. Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum. https://harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/143495.

- Weiwei, A. (2010). Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads [Bronze].