Abstract

The fearless ancient Amazons have been seen as forebears and prototypes by lesbians, feminists, and transgender men. In this introduction, I will explore why the Greek legends of the Amazons lend themselves to such interpretation. Ancient Greek literature details how the Amazons challenged patriarchy, lived without men, and defeated their male enemies, thus setting a precedent that would later be emulated by feminists and lesbians. Though the Amazons are clearly designated as women they are also identified with men in ancient Greek lore; in ancient Greek vase painting, they wear masculine outfits and engage in masculine habits, including fighting and hunting. Thus I will examine the Amazons’ gender transgression in ancient Greek contexts in order to understand how and why these myths set the stage for the adoption of the Amazons as role models by later generations of gender nonconformists. I will also briefly examine the history behind those myths, a history which is just as important to lesbian and other queer communities as the myths which it spawned. Finally, I will weave my analysis of the ancient Greek ideology of Amazons with innovative, new research on the reception of the Amazons found in the six other articles that make up this special edition. These essays explore the powerful place of Amazons and Amazon-like women in the imaginaries of peoples ranging from the ancient Romans to modern lesbian feminists, and the importance of historical and legendary warrior women who defied patriarchy and colonialism in locales ranging from the West to Africa to India.

The Amazon has been an enduring figure of inspiration for lesbians, women of all kinds, and transgender men. Armed with the labrys, a double-headed ax, the Amazon is a symbol of resistance against patriarchy. Legends of Amazons living separately from men and fighting against their oppression have circulated widely since the times of the ancient Greeks. Various Greek authors and artists portrayed the Amazons as brave and heroic, even in the face of defeat, and handed their stories down to the Romans. Fascination with the Amazons carried forward into the Middle Ages and featured prominently in Renaissance “feminism,” where the Amazons were held up as proof of the virtues and capabilities of women (Jordan 1990, p. 109, 202–203, 224–225, 266 n.14). In more recent times, the Amazon has served as a prototype for the lesbian feminist and gender nonconformist alike. That one figure could inspire groups that have often been at odds with one another is indicative of the varied reception of the Amazon legend.

In ancient Greece, women were expected to remain in the private sphere, tending to children, the hearth, and the loom. Yet beginning with Homer (3.189, 6.186), the earliest known Greek author, the stories of the Amazons arose to defy those expectations. While the myths of the Amazons being defeated at the hands of Greek men certainly may have served an ideological function—to reinforce traditional Greek gender roles—myths of Amazon strength and independence served another function for those ancients oppressed by Greek gender ideology, to escape from it.Footnote1 Like any other myth, the legend of the Amazons has morphed over time, and, ultimately, has taken on a new function, which is to provide a form of fictive ancestry for many who identify as queer.Footnote2

In the 1970s, lesbian feminists in the United States adopted the Amazons as their forebears as they defied patriarchy and decided to live without men, in a fashion that became known as lesbian separatism.Footnote3 Lesbians have also used the labrys, the double-ax head associated with the ancient Amazon Hippolyte, as an amuletic symbol of their movement (Walker, Citation1988, p. 95; see also Stevens Citation2000, p. 748, Mayor Citation2014, p. 220).Footnote4 One of several lesbian pride flags prominently displays the labrys in the center, imposed upon a black triangle with a lavender background (see ). The black triangle is a symbol that was once used by the Nazis to identify “asocials,” a group which included lesbian women; it has been reclaimed on this flag but its reclamation is not without controversy (see further Elman Citation1996, pp. 4–6). The labrys pride flag was designed by Sean Campbell, a gay male graphic designer, in 1999 and originally published in the Gay and Lesbian Times, Palm Springs Pride issue in 2000 (Bendix Citation2015). The magazine is no longer in print, but the flag, despite its controversial makeup, lives on as one of several lesbian flags inhabiting cyberspace and sometimes donned in pride parades.

Transgender activists have also seen the Amazons as their ancestors, so to speak. In many retellings of the myth, the Amazons are equated with men. Such Greek lore led author Leslie Feinberg (Citation1996, pp. 22, 57–58) to include the Amazons amongst their Transgender Warriors. In ancient Greek legends and iconography, the Amazons are understood as gender nonconforming individuals.

Given their widespread appeal, it is necessary to view the Amazon myths in a broad perspective, beginning with the Greeks who detailed these legends, which is my main purpose in this introduction. I will begin by assessing the Greek understanding of Amazons as homoerotically-inclined women. Second, I will discuss Amazon separatism and reproduction, as detailed in ancient Greek myth. Third, I will discuss Greek identification of the Amazons with men in textual sources in light of Amazon gender non-conformity as displayed in ancient Greek vase paintings. Fourth, I will discuss the historical basis for the Amazons by comparing Greek texts and iconography to archaeological evidence of ancient women buried with weapons. Finally, I will explore the reception of the Amazons in later periods by briefly describing the other six articles that make up this special issue. As the contributors to this special issue demonstrate, the Amazons served many purposes in later eras. They set precedent by refusing the yoke of marriage and the confines of male domination as well as transgressing gender roles and sexual mores, but, like male warriors, they have also been used to stress the perils of war.Footnote5

Amazons and homoeroticism

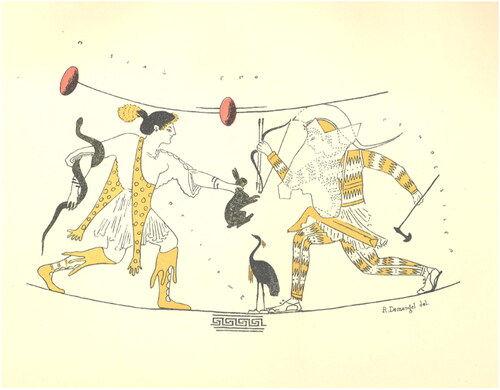

Perhaps the most important question one might raise about the Amazons in the pages of the Journal of Lesbian Studies is whether or not the ancient Amazons were thought to be women-loving women by the Greeks who told their stories. Greek literary sources are silent on the homoeroticism of the Amazons, but some evidence of Amazons as homoerotically-inclined women is found in ancient Greek vase painting. The best evidence of this is found on a white-ground alabastron in the National Archaeological Museum at Athens dating to the late fifth/early fourth-century BCE (see ) (Demangel, Citation1923, pp. 67–97, pl. III; Lissarague, Citation1990, pp. 235–237; Mayor Citation2014, pp. 135–136, Figure 8.2; Penrose Citation2016, pp. 83–84, Figure 2.5).

Figure 2. Maenad hunter presenting Penthesilea a hare. National Archaeological Museum, Athens 15002. Drawing R. Damengel. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture.

On this vase, the woman on the left is identified as Theirichme by an inscription and is dressed like a Thracian maenad (a follower of the wine god Dionysus). She presents a hare, presumably as a gift, to the Amazon Penthesilea, who is armed with a bow and an ax. Theirichme has been identified as a woman hunter, and her gift of a hare is significant. In courtship scenes between males found on Attic vases, such as a red-figure kylix, or drinking cup, now in the Louvre (G 121), this is a gift of choice, where the erastēs, or the lover, gives a hare to his erōmenos, or beloved. Lear and Cantarella (Citation2008, pp. 32–37) understand the hare as both a courtship gift in scenes of male homoeroticism, and, when shown in other contexts, as synecdoche (a symbolic representation) of male homoeroticism itself. Such homoeroticism was not necessarily exclusive of heteroeroticism; both men and women in ancient Greece were expected to marry. At the same time, the courtship scene between the women Theirichme and Penthesilea is found on an alabastron, or perfume container, a vase that would have been used by women.Footnote6 Thus the external viewer of the scene was in all probability a woman (Rabinowitz Citation2002, p. 107; Penrose Citation2016, p. 84).

On another vase owned by the Museum of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (formerly the Cabinet des Médailles, Amasis Painter, 222), two embracing maenads offer a hare to Dionysus, most probably as a sacrifice (see further Meixner, Citation1995, p. 104, Figure 40; Brooten Citation1996, p. 58 n. 132; Penrose Citation2016, pp. 84–85, Figure 2.6). As Theirichme on the vase in Athens is dressed in wild skins that are associated with maenads on other vases, and the two women here are discerned to be maenads because they worship Dionysus, it is tempting to draw a link between these pots. Given the comparison to scenes containing hares that allude to male homoeroticism, it seems quite possible that the hare in this depiction is symbolic of woman-to-woman courtship.

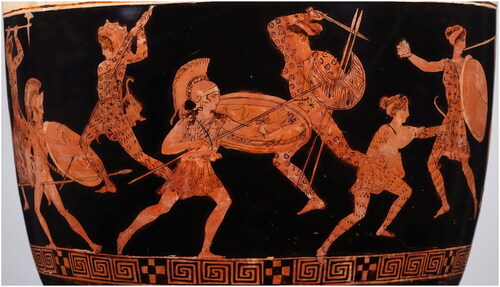

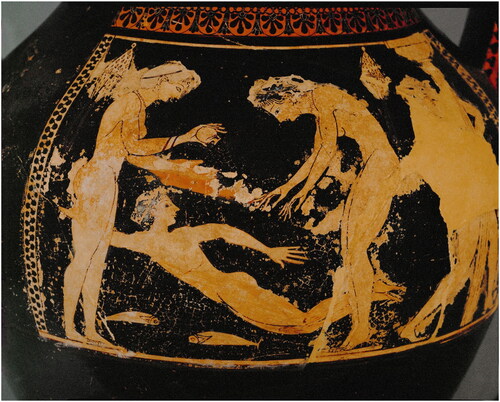

The only other possible iconographic evidence of Amazon homoeroticism of which I am aware is found on a sixth century BCE red-figure vase now owned by the Louvre. On one side of the vase, Amazons are either dressing or disrobing. On the other, they are bathing (). The (dis)robing suggests there is a relationship between the two scenes painted on each side of the vase; the swimming naturally follows or precedes the undressing or dressing.Footnote7 The presence of an aryballos, an oil flask, in the hand of one of the women may suggest homoerotic activity, but scholars disagree on this point. Kilmer (1993, pp. 89–90) notes that bathing scenes are generally of an erotic nature and finds this particular scene to “have mild sexual implications,” but, after noting that the fish is a “phallic” symbol asserts that “the overall impression gives no specific indication that the women plan sexual activity among themselves.” Rabinowitz (Citation2002, p. 137), on the other hand, notes that “there is no internal male audience,” and “the women seem content with themselves.” Certainly, this is a homosocial scene, with women only, and possibly homoerotic.

Figure 3. Amazons swimming and bathing. Red-figure amphora, Andocides Painter. Musée du Louvre F203. Photo Credit: Erich Lesser/Art Resource, NY.

In her popular book, The Amazons: lives and legends of warrior women across the ancient world, Adrienne Mayor asserts that “same-sex desire among Amazons is not in evidence in ancient Greco-Roman art or literature…” (2014, p. 135). At the same time, Mayor discusses the scene of woman-to-woman courtship on the Greek vase that I have described above (), evidence which, as Oliver (Citation2023) also notes in this issue, contradicts Mayor’s denial of said homoeroticism among the Amazons. Instead of acknowledging that this evidence might lead us to believe that at least some ancient Greeks thought of the Amazons as women-loving women, Mayor (Citation2014, pp. 135–136) emphasizes the heterosexual encounters of the Amazons, asserting that numerous “Greek and Roman writers agreed that Amazons were eager sexual partners with chosen male lovers and that they sometimes formed long-term relationships with men…” Furthermore, Mayor (p. 25) asserts that “The image of the Amazons as man-hating lesbians is a twentieth century twist…” To prove this point, Mayor argues that the fourth-century BCE Greek author Hellanicus describes the Amazons as philandros, which she translates as “man-loving,” when, in all likelihood, it means “loving masculine habits” in Hellanicus.

Hellanicus writes: “The Cimmerian Bosporus having been frozen over, the golden-shielded, silver-axed, masculine-habit-loving (philandros), male-infant-killing (arsenobrephoktonos), enormous host of the Amazons, having crossed over it long ago, came” (FGrHist 4 F 167, ed. Jacoby). The Amazons came to Athens to fight for the release of the Amazon Antiope, who had been abducted by the Athenian King Theseus. In my 2016 book, I also translated philandros as “man-loving” and arsenobrephoktonos as “male infant killing” in this passage, and I understood these terms to mean that the Amazons had sex with men (which of course would be necessary to procreate) but killed the male infants and raised only the females (Penrose Citation2016, p. 3).

Upon further reflection, I have since come to change my mind. A translation of philandros as “loving masculine habits,” instead of “man-loving,” makes more sense in Hellanicus. First of all, the translation of “man-loving” contradicts Hellanicus’ assertion that the Amazons are also arsenobrephoktonos, or “male infant killing.” Secondly, the prefix phil- is derived from philia, a type of love in Greek thought that is not generally erotic. Finally, in a fragment of the fifth-century playwright Sophocles (fr. 1111), Atalanta, another masculine woman hunter in Greek myth, is called philandros. According to the standard Greek-English Lexicon by Lidell, Scott, and Jones, philandros in this Sophocles passage means “loving masculine habits.” Indeed, Atalanta was a young woman who preferred the masculine pursuits of hunting and being outdoors to gendered feminine behavior. This reading for philandros makes more sense in Hellanicus as well, and would thus negate a translation of the Amazons as “man-loving.”

Mayor is correct that Amazons in Greek legends do have sexual encounters with men for the purposes of procreation, and they do occasionally form long-term relationships with men. Mayor does not note, however, that Hellanicus also calls the Amazons “male-infant killing,” that philandros can mean “loving masculine habits,” and that Amazons who do form long-term relationships with Scythian men in Herodotus (4.110-117) cease to be Amazons but rather form a new tribe, the Sauromatians (Penrose Citation2016, pp. 3–4). Other evidence also from the Classical Period (fifth to fourth centuries BCE) supports my new reading of Hellanicus, particularly the passage in Aeschylus’ Prometheus Bound (723-4), in which the host of the Amazons is called stuganōr, or “man-hating.” Nor does procreating with men require “loving” them; the sexual act can be simply sexual.Footnote8

Ancient Amazon separatism

Aeschylus is among several ancient Greek authors who portray the Amazons as separatists who rejected men. Acquiring an understanding of these Greek myths helps to explain why lesbian feminists found the Amazon legends so integral to their mission, a subject which my fellow contributors take up in their submissions to this journal issue.Footnote9 In Aeschylus’ Suppliant Women (287-8), when suppliant refugees, the daughters of Danaos who have escaped their husbands, claim Argive heritage, the suspicious King of Argos rattles off a list of women whom he might have suspected them of being, had they looked different. Among his ramblings, he tells them “Certainly I would have guessed that you were the manless (anandrous), carnivorous (kreoborous) Amazons, if you were armed with bows.” This sentence, in a passage without any further context, suggests that Aeschylus understood the Amazons to be hunters, as they are bow carrying and meat-eating, as well as women who lived without men (Blok Citation1995, p. 184), an aspect of their myth that would later appeal to lesbian feminists.

Aeschylus does not explain how the Amazons came to be a single-sex community or ethnic group, nor, for that matter, does Homer (Iliad 3.189, 6.186), the earliest known author to mention the Amazons in the eighth century BCE. It is only from later sources that we learn about the origins of the Amazons. According to the fourth-century BCE Greek historian Ephorus: “…the Amazons were treated insolently by their husbands, and, when some of the men went to war, the Amazons killed those left behind and refused entrance to those returning from abroad” (FGrHist 70 F 60a, ed. Jacoby). Afterwards, we are told by Pompeius Trogus, the Amazons had no desire to marry again: “They [the Amazon women] had no desire to marry their neighbors at all, calling this slavery, not matrimony” (apud. Justin 2.4, ed. Jeep). Of course, Pompeius Trogus wrote in the first century BCE, much later than Ephorus, but the story he tells is similar. As Page du Bois notes, the Amazons were “hostile to marriage. Their very society denied the necessity of marriage. Men were used by them for procreation, but their domestic life was predicated on exclusion” (1982, p. 40).

It then becomes necessary to ask how the Greeks believed that the Amazons procreated. The geographer Strabo, who wrote around the time of the emperor Augustus in the first century CE, tells a story of how the Amazons met up with neighboring men once a year to copulate. Strabo relates that:

Others, among whom are Metrodorus of Scepsis and Hypsicrates…say that the Amazons dwell in lands bordering on those of the Gargarians, in the northern foothills of the Caucasus Mountains which are called Ceraunian, and they spend the rest of their time among themselves…but they have two chosen months in the Spring during which they go up into the nearby mountain that separates them from the Gargarians. The Gargarians also go up following an ancient custom, and they sacrifice together and have intercourse with the women to beget children secretly and in the dark, the men having sex with whichever women they chance upon, and having impregnated them they send them away; and if the child is female the women keep it, and if it is male they return it to the men to raise; and each man to whom the child is given considers it his own due to the uncertainty (11.5.1, ed. Meineke).Footnote10

Amazons and matriarchy

The above-mentioned versions of the myth record the Amazons as living in a separatist fashion from men, but Diodorus Siculus, who wrote in the first century BCE, asserts that the Amazons lived among men in a matriarchal fashion, taking the place of men in an inverted society, at least from a Greek perspective. Footnote11 According to Diodorus, the Amazon women hunted, fought, and farmed the land while they forced the men of their tribe to do domestic labor. Diodorus writes: “And now along the Thermodon River there was a dominant tribe ruled by women, and the women, just like the men, took up military service…” (2.45.1, ed. Vogel). Footnote12 Over time, however, one of the women drilled the other women into a formidable fighting force and placed the men under the yoke of the women, once and for all. Diodorus continues “To the men she assigned the wool spinning and the other household duties of women. She also introduced laws, on account of which she led the women forth into contests of war, while she bound the men in humiliation and enslavement. With regard to their offspring, they mutilated the legs and arms of the males, rendering them useless for the pursuits of war…” (2.45.2-3, ed. Vogel).

It should be noted here that the spinning of wool was a task normally assigned to women in ancient Greece, as were other household chores (Pomeroy Citation1995, pp. 30, 43, 71–72, 113, 144–145). In contrast, men trained for war, generally speaking. (Spartan women who threw javelins and engaged in wrestling and other physical sports like the men, at least according to Plutarch (Lycurgus 14.2), are exceptional in this regard—normally women in other Greek cities were not trained in spear throwing.)

Amazon body modification and gender nonconformity

According to the best-known etymology attributed to the fourth century BCE Greek author Hellanicus of Lesbos (FGrHist 4 F 107), the term Amazon means “breastless.” Footnote13 The alpha privative, or a in English, means without, and mazos is an Ionic Greek variant of the Attic Greek mastos, or breast. The text of Hellanicus has been preserved by a scholiast, or commentator. The scholiast writes: “Amazons are so-called because they cut off their right breast, in order that it will not be in the way when they shoot a bow. This is false, because they would have died from it. Hellanicus and Diodorus say that they cauterized this spot with an iron object before it began to grow, in order that it would not grow” (Hellanicus FGrHist 4 F 107, ed. Jacoby). Of course, one would not need to cut off a breast to shoot a bow, as we know from the modern Olympics. Additionally, in ancient art, Amazons are displayed with two breasts in both the well-known statue of the “wounded Amazon” housed today in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (also known as the Landsdowne Amazon) as well as in other ancient Greek and Roman sculptures and vase paintings (Penrose Citation2016, esp. p. 79 Figures 2.1-2, p. 82 Figure 2.4, p. 125; Mayor Citation2014, pp. 84–93). A word such as Amazon, which was understood to mean breastless in Greek, might have been an epithet that conjured up notions of masculinity in women to the Greeks, even if the said woman did have breasts (Penrose Citation2016, p. 125; Taylor Citation1996, p. 200). Amazons fought and hunted, tasks normatively assigned to men in ancient Greece.

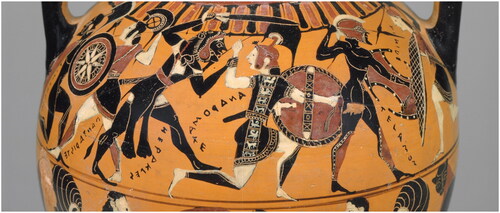

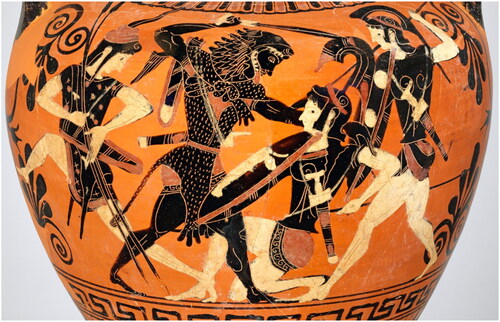

Figure 4. Amazonomachy. Attic black-figure small-neck amphora. Metropolitan Museum of Art 61.11.16. Purchase: Christos G. Bastis Gift, 1961.

In the twenty first century, however, the body modification practiced by the Amazons has been related to gender diversity. One transgender theorist, M.W. Bychowski, has compared the breast removal undergone by Amazons to gender affirming top surgeries undertaken by those who identify as transgender men today. Bychowski (Citation2016) writes: “while Amazons play a role in the history of strong and/or butch cisgender women, they have more genealogical connections with trans men than previously imagined.”

In this context, stories of Amazons function as myths of queer ancestry, providing a much-needed past precedent for transgender men in addition to women. As the term transgender was not coined until the 1960s or 1970s (Williams Citation2014, p. 233), some scholars see the application of it to figures of the historical past as anachronistic (e.g. Robey Citation2019, p. 66). Nevertheless, the fourth-century BCE Athenian orator Lysias (2.4) does perhaps inspire what we today might call a “transgender reading.” He writes:

The Amazons were the daughters of Ares in ancient times who lived beside the River Thermodon. They alone of those dwelling around them were armed with iron, and they were the first of all peoples to ride horses, and, on account of the inexperience of their enemies, they overtook by capture those who fled, or left behind those who pursued. They were esteemed more as men on account of their courage than as women on account of their nature. They were thought to excel men more in spirit than they were thought to be inferior due to their bodies (2.4, ed. Hude).

They [the Amazons] ruled over many nations, and they had indeed enslaved those living around them, but, having heard a report of the great glory of our country, for the sake of their own great reputation and in high hope they gathered together the most warlike of peoples and marched against this city. Having encountered valiant men, however, they found that their spirits were like to their nature [i.e. sex], and they earned the opposite of their former renown, and more from their perils than from their bodies they were deemed to be women (2.5, ed. Hude).

Once I went to Phrygia, rich in vines, and there I saw numerous Phrygian men with galloping horses, the armies of Otreus and godlike Mygdon, who were then camping near the banks of the Sangarius River. I had chosen to be among the allies with them, and it was on that day that Amazons, the equals of men, [Amazones antianeirai] came (Iliad 3.184-189, ed. Mazon).

Thus, in early extant Greek literature, the Amazons are clearly defined as women, but gender nonconforming, masculine ones at that. Although they are sexed as women, the Amazons are either called men in some fashion or another, as in Lysias (2.4), or equated with them, as in Homer (3.189, 6.186) as mentioned above. Thus, the myths have appealed to transgender activists and scholars (Feinberg Citation1996, p. 22, 57–58; Bychowski Citation2016). And while vase iconography only has a little to tell us about the sexuality of the Amazons (see the “Amazons and Homoeroticism” section above), it tells us much more about the gender of the Amazons. First of all, Amazons are almost always depicted fighting, which, according to the Greeks at least, was the domain of men. Secondly, Amazons are depicted wearing men’s clothing.

On a black-figure vase now owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (61.11.16), an Amazonomachy between Heracles (called Hercules in Latin and English) and three Amazons is depicted (see ). An Amazonomachy is a battle between Greeks, on the one hand, and Amazons, on the other. It is a fairly common theme on Greek pottery as well as temple reliefs.Footnote15 In this depiction, there are no inscriptions, but we can tell that the male is Heracles by a number of his attributes. First of all, in black-figure pottery, which was prevalent during the sixth-century BCE, men are depicted with black skin, and women with white skin. Thus skin color tells us about sex/gender, not ethnicity or race. Secondly, the male figure is wearing a lion skin and holding a club—these are both well-known attributes of Heracles. Additionally, in Greek and Latin texts Heracles/Hercules is described as fighting Amazons, in particular Hippolyte and her sisters (Diodorus Siculus 2.46.3-4; Pausanias 5.10.9; Quintus Smyrnaeus Posthomerica 6.240-45; Hyginus Fabulae 30). On the vase, in contrast to Heracles, the Amazons are depicted as white-skinned. Again, this is a marker of sex, of being a woman, rather than a denotation of race or ethnicity. At the same time, the Amazons wear clothing and have other attributes—namely military equipment—that were associated with men by the ancient Greeks. First of all, the Amazons on the right side, at least, are wearing helmets and a type of body armor known as a breast plate, or cuirass. Secondly, they wear a short tunic that was generally worn by men in Greece, even if it may look like a woman’s mini skirt to the modern eye (Vaness Citation2002, pp. 97–98). The central Amazon and Heracles, in fact, wear the same short tunic. In ancient Greek iconography, the short tunic is worn not only by Amazons, but also by other young women such as Atalante, who transgressed against conventional female norms of ancient Greece in both text and art, living an active lifestyle (Parisinou Citation2002, esp. pp. 59, 61–62). The goddess Artemis also wore short skirts, identifying her as a huntress (Parisinou Citation2002, passim).

Greek women typically wore a long chiton, that came down to their ankles (Wagner-Hasel Citation2002, pp. 17–18, 18 ), whereas Greek men generally wore a short chiton, which fell above the knee. The Amazons wear a short chiton—again, men’s clothing, even if it may look like women’s dress to us—on the Amazon reliefs from the Mausoleum, which date to ca. 350 BCE (Penrose Citation2016, pp. 78-79, Figures 2.1, 2.2 = British Museum 1857, 1220.270, 1865, 0723.1). That said, one can differentiate between the Greeks and the Amazons based upon physicality—the Amazons have breasts and the Greeks are naked, revealing their bodies and genitalia. Once again, the Amazons appear to have both breasts, but they are dressed in a masculine fashion and engage in a masculine pursuit—fighting. The Amazon on the right appears ready to strike the Greek, who cowers below her, but her weapon has been broken off the relief. Whereas Amazons are often (but not always) defeated in Greek literature, on the Mausoleum reliefs and in other ancient Greek artwork they are often depicted in a pitched battle with men, with neither side winning (Penrose Citation2016, p. 78).

Amazons appear on Greek painted vases starting in ca. 575 BCE (Vaness Citation2002, p. 96). On black-figure vases, they are distinguished not only by the color of their skin—white, as opposed to the black skin of the Greek male warriors—but also sometimes by subtle differences in outfits as on a vase from the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston by the Timiades painter (see ). The Amazon on the right wears a short, male tunic, but it is decorated like we see on longer chitons worn by other, more gender-conforming women (Vaness Citation2002, p. 97). The Amazons’ outfits contrast with that of Heracles, and their helmets with the helmet of the male Greek warrior, Telamon, on the far right. Such differences are typical but are done in a mix and match pattern. Helmets, weapons, shields and other attributes found on Greeks on one vase might be found on Amazons on another. The same can be said for the wild skins worn by Heracles, as they are sometimes worn by Amazons, such as Penthesilea. Such skins might seem to indicate barbarian status on Penthesilea, meaning non-Greek, but Heracles is Greek and is represented in a similar fashion. The patterns vary, but are indicative of the masculinity of the Amazons—they wear similar clothes and often fight with the same weapons as the Greeks. At the same time, they are conceived of as very different from the men whom they fight (Vaness Citation2002, p. 97). In twenty-first-century parlance, we might think of the Amazons as gender non-binary or transmasculine, but from an ancient Greek perspective, they might be better understood as representative of female masculinity (Penrose Citation2016, p. 2).

Thracians and Scythians: the history behind the myth?

Thus far, I have explored Amazons wearing Greek male outfits and sporting Greek weapons and shields. Starting around 550 BCE, and with greater frequency thereafter, Amazons begin to appear with Scythian and Thracian attributes (Shapiro, Citation1983, p. 106). This is perhaps due to the fact that among the Scythians and Thracians there were historical women warriors. I do not wish to equate Amazons with these historical warrior women, but rather to suggest that a relationship existed between them. Myth is often a way for people to explain the natural and physical world around them. For example, lightning was understood to be Zeus throwing his spear down upon humans in anger. In Greek texts, Amazons tend to show up in places like Thrace, Scythia, and Sauromatia, where historical warrior women lived (Penrose Citation2016, p. 105), but they are described as mythical beings, the daughters of Ares, whose lifestyle is often not just in marked contrast to, but an inversion of, Greek norms.Footnote16 In other words, the Greeks mapped the Amazons onto the more historical warrior women in the same way that they mapped Zeus’ spear onto lightning. Whereas Adrienne Mayor (Citation2014, p. 12) has argued that “Amazons were Scythian women,” I see the relationship as far more complex. Although I do think the Amazons are loosely based upon the idea of historical warrior women, they are a Greek way of understanding those women as semi-mythical beings, as the “daughters of Ares.”

Archaeological evidence of women buried with weapons has been excavated among not just the Scythians, but also among Thracians and Sauromatians, ancient peoples who lived in Eastern Europe and Central Asia (see further Davis-Kimball & Behan, Citation2002, pp. 46–66; Mayor Citation2014, pp. 63–83; Penrose Citation2016, p. 5, 105–111; Rolle Citation1986, Citation1989, pp. 86–91, 2010; Teleaga Citation2010). Ancient Greek vase paintings show Amazons wearing Scythian and possibly Thracian clothing, and using Scythian and Thracian weapons as well.Footnote17 In some of the earliest Greek literature, the Aithiopis of Arctinus, the Amazon Penthesilea was apparently called Thracian. Unfortunately, this text is now lost, but a summary of it was preserved by Proclus in the fifth century CE: “The Amazon Penthesilea, a daughter of Ares and Thracian by race, arrives to assist the Trojans as an ally. Achilles kills her as she acts heroically and the Trojans bury her” (Chrestomathia 2, ed. Gaisford). This scene is beautifully illustrated by the sixth-century BCE Greek vase painter Exekias on a black-figure amphora today owned by the British Museum (1836,0224.127; Penrose Citation2016, pp. 127–129, Figure 3.1, Mayor Citation2014, p. 296, Figure 18.2). Penthesilea, shown on the right of the vase, wears a leopard skin, but otherwise has the accoutrements of a Greek hoplite (infantry soldier), including a round hoplon or shield, a spear, and a helmet. Alan Shapiro (Citation1983, p. 108) has convincingly argued that leopard skins on Greek vases associate Amazons with Thrace. First of all, Proclus, following Arctinus, asserts that Penthesilea was both thought to be a daughter of Ares, yet also of the Thracian race. Secondly, maenads, the followers of Dionysus, also came from Thrace, and are depicted wearing leopard skins on Greek vases as well. But perhaps the most easily identifiable attribute that is associated with Amazons is the pelta, or the Thracian half-moon shield carried by two Amazons on an amphora from Munich (inv. 1504; Penrose Citation2016, pp. 95–97, Figures 2.14-15). These are women, as the white skin identifies them, and have been understood as Amazons due to their weapons and shields (Von Bothmer Citation1957, p. 101 no. 116). On the reverse side are two Thracian men, who are identified as such because they wear a zeira, or patterned cloak that we know to be Thracian. The women and the men are dressed differently; the women do not wear Thracian cloaks, but they do carry Thracian half-moon shields, or peltae. The iconographic evidence supports the literary quote in associating the Amazons with Thracians, an historical people.

As mentioned above, the Amazons are also associated with Scythians (Mayor Citation2014, esp. 34-39; Penrose Citation2016, esp. 4-5, pp. 102–104, 105, 111). Whereas Lysias (2.4-5), writing in the fourth century BCE, tells us that the Amazons attacked Athens alone, Diodorus Siculus asserts that they did so as allies of the Scythians: “When the Scythians had allied themselves with the Amazons, indeed a powerful force worthy of mention had been mustered, with which the leaders of the Amazons crossed the Cimmerian Bosporus, and marched through Thrace. In the end, having advanced through much of Europe, they came to Attica, where they camped at the place that is now called after them, the Amazoneion” (4.28.2, ed. Vogel). Diodorus further asserts that, having been defeated by the Athenians, the Amazons returned to Scythia (the modern Ukraine), and decided to settle there instead of going back to their original home of Themiscyra, in northern Turkey: “The Amazons who survived renounced their ancestral homeland and returned with the Scythians to Scythia and dwelled among them” (4.28.4, ed. Vogel).

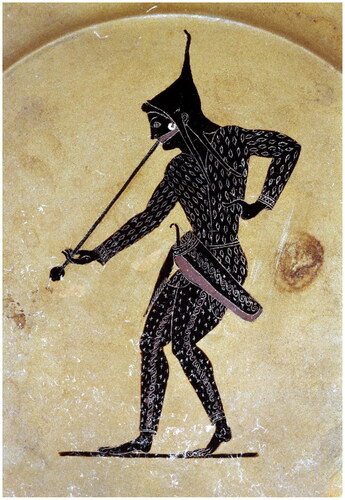

Amazons are depicted with Scythian attributes in Greek vase painting by the 550s BCE and are shown wearing fully Scythian garments by the 520s BCE (Shapiro, Citation1983, p. 111; Gleba Citation2008, p. 15). Scythians were known as excellent archers in antiquity. On a Greek black-figure pinax (plate) now in London at the British Museum (see ), a Scythian archer is depicted with a quiver, to hold arrows, an arrow, and wearing a Scythian costume, consisting of spotted leggings or pants, a spotted short tunic, and a pointed cap (Gleba Citation2008, pp. 14–15, Figure 2.1).

On a red-figure vase, also in the British Museum, a Scythian archer in a similar outfit is shown, but with a slightly different cap, which is rounded (Gleba Citation2008, p. 16, Figure 2.2). Pants were developed in the northern parts of the world, because they keep one warmer (Bonfante Citation2011, p. 19), and may have had little or nothing to do with gender upon their inception. They are also more practical for riding horses. On a red-figure terracotta lekythos now in New York (), which dates from ca. 440-410 BCE, we see Amazons fighting Greeks, although we can only see two Greeks in this view. On red-figure vases, which we first see around 530 BCE, gender is not as clearly marked as on black-figure vases. Dress and visible breasts distinguish Amazons from Greeks on this vase. The Greek male warrior is shown in the center left wearing a short chiton, a traditional Greek helmet, and is holding a traditional hoplon or Greek shield. He is engaged in hand-to-hand combat with an Amazon wearing Scythian dress, whose breasts are apparent, but does not engage in archery. Instead, she uses a sword to fight and holds a Thracian shield. While the dress of each of the Amazons varies somewhat, each seems to be dressed in a non-Greek outfit. The portrayal of various ethnic dress and attributes is typical on Amazons in Greek iconography (Gleba Citation2008, p. 15; Shapiro Citation1983, p. 111).

Regardless, it is tempting to say that, in comparison to the male Scythian archer (), the Amazon in , on the center right, is wearing male Scythian clothing. The problem that arises with such a reading, however, is that we know very little about Scythian women’s dress (Gleba Citation2008, p. 23). Whereas Herodotus (7.64) provides us with a description of Scythian male dress, consisting of tall, pointed caps and pants, no such description of Scythian women’s dress is found in Greek literature, and, if the Scythians themselves left a written record behind, it has not survived. It does not help that Herodotus’ description of Scythian territory, as stretching from the Danube to the Don (roughly equivalent to the modern Ukraine) conflicts with his testimony that the Sacae, who lived in central Asia, were a Scythian people (4.21, 7.64). Analysis of frozen tombs in Siberia have been used to infer how Scythian women dressed, as both the interred in Siberia and the Scythians were steppe nomads. At the Siberian site of Pazyrak, the clothes of nomads buried there have been preserved by permafrost. At Pazyrak, young women are buried wearing trousers, which may indicate that they were warriors (Mayor Citation2014, pp. 204–205), which could correspond to Amazons on vases wearing pants. Older women wear robes or skirts over leggings. The only evidence from Scythia proper is a gold plaque depicting what is thought to be a goddess. She wears long, flowing robes. Burials of Scythian women with weapons found in the Ukraine do not contain clothing, as they have decayed. Greek iconography of Amazons, as noted above, seems to use a mix and match approach, where Amazons wear various outfits, some Greek, some Scythian, and some Persian, with Thracian attributes thrown in here or there (Vaness Citation2002, esp. 96).

Whether the Amazons were real or mythical has been a matter of contention among scholars. The truth probably lies somewhere in between these dichotomous viewpoints (Penrose Citation2016). The Amazons were at least based, in part, on historical warrior women. Regardless, the Greeks perceived them as traversing preconceived Greek notions of gender and sexuality. In contrast to the ways in which the Greeks perceived femininity in men, they did not necessarily understand the masculinity of the Amazons negatively, but rather used them to effeminize non-Greek others, as seen in the passage of Lysias (2.4-5) quoted above. Whereas they defeated “barbarian” men, they were usually (but not always) defeated by Greeks in Greek lore.Footnote18

The reception of Amazons

Given the ways in which they challenge patriarchy as well as socially constructed notions of gender, the ancient Greek legends of the Amazons have had a rich reception from the time of the Romans onwards. The other six articles that make up this special issue each tell a unique story of this reception. Of course, the reception of the Amazons is vast and no one journal issue or volume could possibly purport to tell the whole story. Yet the articles contained herein strike some of the most important notes of this abundant reception, especially as the Amazon legends pertain to an audience interested in Lesbian Studies.

As I have noted above, the evidence suggesting that the Amazons were proto-lesbians (i.e., women-loving women) or the equivalent is quite limited. As Jay Oliver (Citation2023) notes in their article “Acca soror: queer kinship, female homosociality, and the Amazon-huntress band in Latin literature,” female homoeroticism was not a subject that received much attention in ancient literature, at least not in that which has survived the ravages of time, most of which was written by men. Sources that did explicitly discuss female homoeroticism may have been destroyed or were simply lost (Penrose Citation2014, esp. pp. 422-24; 2016, p. 86). This, however, is not to say that there is no association of queerness and women in ancient literature. Thus, Oliver suggests a paradigm shift, in which aspects of kinship and relationality, in conjunction with gender nonconformity, can be used to understand queerness in lieu of homoeroticism alone. Oliver notes this begins with Greek legends of Amazons, where matrilineality and the raising of only female children present the reader with deviation from norms of Greek patriarchy.

The main focus of Oliver’s work, however, is Latin literature that details aspects of Amazon-like huntresses, such as Camilla in Virgil. Through a close reading of such Amazon huntresses in several Latin texts, Oliver defines a model of queer kinship that is not based upon marital or blood relations, but rather upon bonds of sodality and adoptive sisterhood. The character Acca in Virgil’s Aeneid illustrates this well; she is devoted to the warrior woman, Camilla, “beyond all others.” In turn, Camilla calls her soror, or sister, even though the two are not related by blood. The story of Camilla is not a central focus of Virgil’s narrative, but rather a side show of sorts. Oliver notes that Camilla’s lifestyle involves preserving her virginal status by shunning male company (except for military alliances), repudiating household labor, living in the wild, and being utterly and completely devoted to the virginal goddess of the hunt, Diana. This lifestyle, which Oliver terms “Embracing Diana” is queer in and of itself, whether or not it involves homoeroticism. Oliver’s “Embracing Diana” paradigm does acknowledge and is suggestive of female homoeroticism, however, in another Roman author, Ovid. Oliver points to Ovid’s myth of Callisto, in which Jupiter, the king of the gods, disguises himself as the goddess Diana in order to seduce the huntress Callisto, who, like Camilla, has eschewed the company of men and chosen to devote herself to Diana. Ovid’s descriptions of the kisses shared between the two is suggestive of, if not explicit about, the potential homoeroticism between human women found in the Amazon huntress lifestyle as exposed in Latin literature. Certainly, Callisto’s erotic desire is for other women; otherwise, Zeus would need not have disguised himself as Diana.

Oliver extends his analysis of embracing Diana to the character of Phaedra, who, in Euripides’ Greek version of the tragedy named for her, had lusted after her stepson due to divine intervention by Aphrodite. In Seneca’s Latin Phaedra, in contrast, more focus is placed upon Phaedra’s desire to be like Hippolytus’ mother, the Amazon Hippolyte, due to the freedom that she held, in contrast to the confining life of marriage and seclusion in the house of Theseus, her husband and Hippolytus’ father, that Phaedra has instead experienced. Oliver’s astute readings of Virgil, Ovid, and Seneca provide scholars with new ways to think about queerness and gender nonconformity in ancient texts on Amazon huntresses.

Amazonian gender nonconformity is also a central theme in Michael Anthony Fowler’s article “Rosa Bonheur the Amazon? Equestrianism, Female Masculinity, and The Horse Fair (1852-1855).” Fowler (Citation2023) begins his article by noting that the famed French artist Rosa Bonheur claimed that her most-celebrated painting, The Horse Fair, was inspired by the Parthenon frieze. Previous scholarship has failed to note Bonheur’s reception of Classical Greek art in this painting. Furthermore, Bonheur seemingly included herself, dressed entirely in male clothing, as one of the riders. Fowler further argues that although in nineteenth-century France there was a popular conception of an Amazon as a woman who wore a feminine riding habit replete with a skirt and rode side saddle, Bonheur fashioned herself as an Amazon more so along the lines of the ancient Amazons. She obtained permission, interestingly, to wear only men’s clothing while engaged in her work (which included visiting horse fairs and other venues where she painted animals) in order to avoid being molested by men in addition to having the freedom to enter male-dominated spaces. Bonheur also sought and achieved success in a male-dominated world of art. Thus, she sought equality with men in much the same fashion as the ancient Amazons of Greek lore. Fowler’s contribution to scholarship is particularly poignant at this moment in time, when the owner of the Château de Rosa Bonheur, Rosa’s home on the edge of the Fountainebleau Forest, has denied that she was a lesbian, despite the fact that she never married and had documented relationships with two women (Liu Citation2022).

The next article in this issue, “Queer and/or Lesbian?: Amazons in Christa Wolf’s Cassandra,” by Nancy S. Rabinowitz, explores East German author Christa Wolf’s deployment of Amazons in her genre-bending Cassandra: A Novel and Four Essays. Wolf retells the story of the Trojan War from the perspective of Cassandra, a seer and Trojan princess. She uses the Amazons to present a contrast to her protagonist. Wolf’s message is anti-war and anti-heteronormative, but she does not idealize the Amazons as many lesbian feminists of her time did; she resisted western feminism, falsely defining it as simply man-hating although she was well read in important feminist texts of her day.

The Amazons are clearly lovers of women in Cassandra. Early on in the novel, the reader encounters Cassandra’s desire for the Amazon Myrine, who came with her lover/queen, Penthesilea, to fight on the side of the Trojans. Cassandra later takes Aeneas as a male lover. Whereas Cassandra is either bisexual or pansexual, the Amazons are definitively lesbian and remain steadfast in their homoeroticism.

Wolf criticizes the traffic in women and compulsory heterosexuality of the Trojans, but she is also critical of the Amazons. The fact that the Amazons are equals of men is problematic for Wolf; they eschew patriarchy, on the one hand, but recreate its problems, on the other hand, through their warlike nature. Wolf is more in favor of a third space that she develops in the novel, which welcomes all outsiders, including men who are wounded. That space is underground. The Amazons refuse this space, but Cassandra ultimately ends up there.

Wolf thus stands apart from the wholesale adoption of the Amazons as prototypes and forebears that was undertaken by U.S.-based lesbian feminists of the 1970s and 1980s. Amy Pistone explores the latter subject in her article, “Lesbian Nation is Amazon Culture: Lesbian Separatism and the Uses of Amazons.” Pistone explores lesbian appropriations of the Amazon myths in the separatist process of lesbian nation-building. In the 1970s and 1980s, lesbian feminists adopted the Amazons as their forebears by reformulating the Greek legends. Lesbian feminists excerpted tales of Amazons defying patriarchy and reformulated their own identities as Amazons in a paradigm that centered women, stripping lesbian identity of any attachment to men. The term ‘Amazon’ became popular in names that signaled business commitments to serve lesbians, such as the Amazon Bookstore Cooperative, in conceptions of lesbian separatist organizations, such as Amazon Nation, and in the renaming of locales, such as the Amazon Trail, a corridor of lesbian lands in Northern California and Southern Oregon. The separatism of the Amazons became a model for lesbian feminist separatism, a movement designed to remove the oppression of patriarchy from the lives of lesbians. The very terms used in Greek myths to describe the Amazons, such as “man-destroying,” “manless,” and “man-hating” supplied a fertile ground for lesbian separatists/feminists to reclaim and reappropriate the Amazon legends for their own needs.

Pistone’s article creates a paradigm for thinking about the relationship of the experiment of lesbian/Amazon nation building to more current ideas of queer liberation. Specifically, Pistone, following Ward (2016) uses “dyke-centric queer methods” to underscore the messy, fluid, and ever shifting taxonomies of queerness. Pistone notes that the lesbian feminist movement was built upon a binary model of sex/gender, current in the 1970s and 1980s, that looked at men and women as opposing forces, and this binary opposition was part and parcel of why the process of Amazon nation building ultimately, for the most part, failed. The natural fluidity that queerness brings to any political movement was overshadowed by the whiteness of the lesbian feminist movement. Questions such as who the citizens would be in such a lesbian, Amazon nation became issues. Intersectionality was at stake; some women in the movement were loath to give up connections to Black liberation movements, for example. Pistone looks to theorists such as Homi Bhabha, whose concepts of mimicry and hybridity might better serve both to rethink the past, where women’s bodies were colonized by men, and the future, where the need exists to think of queer liberation from a multi-gender, intersectional, and less exclusive lens, as well as to create a movement that makes allies of those outside the lesbian community.

The next article in this issue, “Archives and Amazons: a quilter’s guide to the lesbian archive” by Sarah-Joy Ford, continues to investigate the lesbian feminist use of Amazons as symbols. Ford stresses the need to find a lesbian history, noting poignantly that the importance of archaeological discoveries of Amazons allows them to become “tangible matriarchal ancestors” of lesbians (Ford Citation2024, p. 5). In order to record, recover, and reimagine the lesbian history of the 1970s and 1980s, Ford engages deeply with archival materials, deploying symbols such as Amazons, the labrys, the double interlocking Venus, as well as yonic and vulvic symbols in her quilted works of art. Ford understands such symbols as political means of communication that, in visual form, exist outside of language. Ford’s quilts evoke the desire of a younger generation for the vitality and radicalization of the lesbian movements of the 1970s and 1980s but do so in a thoughtful manner that channels nostalgia “not without criticality” (Ford Citation2024, p. 3).

Specifically, Ford’s analysis, or “auto-ethnography” of her own work describes a process in which she employs symbols used by varying groups of lesbians who were at odds with one another. Lesbian feminists who created the London Lesbian Archive and Information Center in 1984, and whose platform included separatism, anti-pornography, and anti-S&M directives, employed the Amazon as a symbol of the strength of their movement. Correspondingly, Ford deploys one such image of a riding Amazon, derived from this archive, on her masterful quilt, Archives and Amazons, which was displayed at an exhibition utilizing the same name at HOME in Manchester. Ford’s work brings this image, and all that it represents, into dialogue with another use of the Amazons in the work of Tessa Boffin. Boffin, who embodied a political agenda across the aisle from the lesbian feminists of the London Lesbian Archive and Information Center, photographed two women, with their breasts bare, pulling back bows in a reenactment of Amazon vitality pleasured by physicality. The photographs derive from Boffin’s groundbreaking compilation, Wet and Wild Women of the Cleaxe Age, published in Quim magazine. Boffin, in contrast to the lesbians who founded the London Lesbian Archive and Information Center, sought to create sex-positive images of lesbians, in addition to advocating for the inclusion of women in safe-sex campaigns at the height of the AIDS crisis. Through the inclusion of the symbolism of these various groups in her own art, Ford seeks to entangle the factions opposed in the lesbian sex wars in a dialogue that not only reclaims, but also re-sexualizes and revisions the Amazons.

In the final article in this special issue, “Amazons Among Us: Reflections on creating the heroines we need now,” Donna Dodson rethinks Amazon imagery in her own artistic practice. Dodson’s sculptures seek to empower women generally, and queer women particularly. Dodson lays out the inspirations behind and the intentions of her new “Amazons Among Us” wood sculpture series. In this series, Dodson reimagines Albrecht Durer’s “Four Horsemen” from his Apocalypse series as Amazon warriors. Whereas Durer’s four horsemen were allegories of plagues, Dodson’s four Amazons are symbols of “the heroines we need now” to battle the challenges that lie before us as humans. The first sculpture in Dodson’s series, “Alpha Female,” is so named to reclaim the “alpha” from the toxicity associated with the masculinity of the “alpha male.” The inspiration behind “Alpha Female” is the military service of women, particularly that of Dodson’s own great aunt, which has so often gone unrecognized. “Alpha Female” brings into question what benefits the leadership of women might provide to humanity as a whole.

The next two sculptures in the series “Black Panther” and “Cybele,” are inspired by two women lovers of the Dora Milaje fictional warrior women found in the Black Panther comics who were left out of the 2018 Black Panther film, but were incorporated into the 2022 Black Panther: Wakanda Forever movie. These sculptures evoke the historical African warrior women of the Kingdom of Dahomey (or present day Benin). “Black Panther” has a feline head and mane, not unlike the ancient Egyptian goddess Sekhmet. Dodson’s panther queen is seated on the throne of Wakanda, which, in the 2022 film, she rules. “Cybele,” Black Panther’s lover, is based upon the ancient goddess Cybele, who, like the Amazons, is depicted in ancient Greek artwork as riding a lion. Cybele was a mother goddess whose origins derive from Asia Minor (modern Turkey).

The fourth sculpture in Dodson’s series, “Lakshmibai,” is inspired by the queen of Jhansi (1828-58) who became a national Indian heroine after leading the 1857 Indian revolt against the British. “Lakshmibai,” like the Amazons of Greek lore and iconography, wore men’s clothing, partook in warfare (which is too often described as the domain of men), and thus could be described as representative of either female masculinity or transmasculinity. Like her other three counterparts, Lakshmibai’s memory evokes the possibility of challenging patriarchal forces with courage, grit, and determination. Like “Black Panther” her story also challenges colonialism and sets an example of how we might rethink leadership today from female, gender nonconforming, and/or non-Eurocentric points of view. Dodson’s quartet of these four Amazons brings so many salient issues before our eyes for examination and reexamination.

Conclusion

In this article, I have introduced the reader to the ancient Greek legends of the Amazons, and the history behind them, both of which came to matter greatly in the epochs that followed. The authors in this special issue discuss how the Amazons resonated in later contexts, especially for women-loving women who wished to live outside of patriarchy. From the huntresses of Latin literature to the women warriors of Dahomey, the term Amazon has been applied to signal transgression from both gender norms and the confines of heteronormativity. The symbolism of the Amazon endures, as the Amazons ride on to destabilize patriarchy and colonialism in art and text. Furthermore, in the late twentieth and twenty-first centuries, an expansive rearticulation of the Amazon myth has arisen. While the legends of the Amazons have provided a fictive ancestry for lesbians, today they also serve as a myths of ancestry for transgender and gender nonbinary audiences as well.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Ella Ben-Hagai, Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Lesbian Studies for her incredible support during this process, Esther Rothblum, previous Editor-in-Chief of the journal for her encouragement of this work in its infancy, the six contributors to this issue whose dedication and brilliance shines through their articles to enlighten us all, Sarah Brucia Breitenfeld, who co-organized the panel at the Society for Classical Studies Annual Meeting in 2022 from which this issue arose, and Marcia Gallo for her suggestions on lesbian history. A special thank you is due to Blanche Wiesen Cook, who, years ago during a job interview, looked at me and said “You’re going to prove that the Amazons existed? That’s great!” I will be forever grateful to Blanche for her support of my career; she is the lesbian Amazon whose generosity inspired me to carry forward with this project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Walter Duvall Penrose,

Walter Duvall Penrose, Jr. is Associate Professor of History at San Diego State University, specializing in the History of Gender and Sexuality. He is the author of Postcolonial Amazons: Female Masculinity and Courage in Ancient Greek and Sanskrit Literature (Oxford 2016). Walter has also published essays and journal articles on the reception of Sappho from antiquity to the early Renaissance, the role of the Amazons in Wonder Woman (DC) and Troy Fall of a City (BBC/Netflix), queer pedagogy in the Classics classroom, homoeroticism in ancient tomb paintings, conceptions of disability in ancient Greece, as well as homoeroticism and gender in South Asian history.

Notes

1 All translations are mine. Blundell (Citation1998), pp. 55–56, Goldberg (Citation1998), pp. 89–100. Morales (Citation2007) identifies a number of functions of myth, including but not limited to escapism, projecting ideology, providing (fictive) ancestry, and queering sexuality.

2 On myths of ancestry, see Morales (Citation2007), ch. 1.

3 On the use of the Amazons by lesbian feminists, see further Ford (Citation2024), Pistone (Citation2024) in this issue.

4 Plutarch Greek Questions 45 (=Moralia 302a) tells the story of how Heracles took the Amazon Hippolyte’s double-headed axe, the labrys.

5 On the former, see Oliver (Citation2023), Fowler (Citation2023), Ford (Citation2024), Pistone (Citation2024), and Dodson (Citation2024) in this issue; on the latter, see Rabinowitz (Citation2024) in this issue.

6 On alabastra as women’s vases, see Rabinowitz (Citation2002), p. 107.

7 Cf. Corso (Citation2023).

8 Plutarch (Theseus 26) does also note that the Amazons were philandroi, which Rabinowitz in this issue translates as “well-disposed to men.” The context of this passage does warrant such a translation, as it is when the Amazon Antiope approaches the visiting king of Athens Theseus’ ship to give him gifts. He returns the favor by abducting her and taking her to Athens. It should also be noted that Plutarch wrote more than five centuries after Hellanicus. The same can be said of Diodorus, who, as I will discuss below, describes the Amazons as living in a matriarchal function and ruling over men. In the 5th century BCE account of Herodotus (4.110-17), the Amazons are captured by the Greeks and taken on board ships headed from Themiscyra, the Amazon homeland on the Black Sea, but kill their captors. They then meet and mate with Scythian men, forming a new tribe, the Sauromatians. They cease to be ethnically Amazons when they marry the Scythians. In Herodotus, the marriage of the Amazons to the Scythians seems to form an aetiological purpose, that is to explain the warlike nature of Sauromatian women.

9 See especially Ford (Citation2024) and Pistone (Citation2024) in this issue.

10 I have translated the Greek myself from the edition of Meineke. An online, unredacted English translation of Strabo’s story of the Amazons can be found at https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Strabo/11E*.html.

11 The earliest instance of this version of the Amazon myth may predate Diodorus. According to Stephanus of Byzantium, Ephorus (FGrHist 70 F 60b), writing in the fourth century BCE, told a similar tale, except that he noted that the Amazons were called Sauromatians in his day, which confuses the matter. See further Dowden (Citation1997), pp. 11–12. Amazons are shown among men on Greek vases at an earlier date, although the context of such depictions is difficult to discern. See further Penrose (Citation2016), pp. 133–136; Bothmer (Citation1957), pp. 97–100.

12 I have translated this text myself. An English translation by Oldfather may be found at https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Diodorus_Siculus/home.html.

13 Other etymologies of the term Amazon have been proposed stemming from Greek and other languages. See further Blok (Citation1995), esp. pp. 21–30; Mayor (Citation2014), pp. 85–88. I have here decided to focus on the best-known etymology, that of Hellanicus, as it is most relevant to the purpose of this article.

14 On courage as a marker of gender diversity in other ancient Greek texts, see further Penrose (Citation2016), esp. pp. 38–43.

15 Some examples of Amazonomachy scenes are found on the Mausoleum reliefs, now housed in the British Museum (on which see below); examples on vases include Figures 4, 5, and 7.

16 Burials of women in the Caucasus region predate the earliest Greek representations of Amazons in literature and artwork by at least a century. See further Ateshi (Citation2011), pp. 11–13, 43; Penrose (Citation2016), 138; cf. Ivantchik (Citation2013)

17 The case for Sauromatian clothing in Greek vase painting is less clear. On the literary connections between Amazons and Sauromatians, see above n. 8.

18 E.g. Lysias 2.4-5; Pseudo-Apollodorus Bibliotheke 2.5.9; Plutarch Theseus 27-8. The Amazon defeat of their Greek captors in Herodotus (4.110) stands as an exception.

References

- Ateshi, N. (2011). The Amazons of the Caucasus: The real history behind the myths. Baku, Azerbeijan.

- Bendix, T. (2015). Why don’t lesbians have a pride flag of our own? AfterEllen. https://afterellen.com/dont-lesbians-pride-flag/.

- Blok, J. H. (1995). The early Amazons: Modern and ancient perspectives on a persistent myth (P. Mason, Trans.). E. J. Brill.

- Blundell, S. (1998). Marriage and the maiden: Narratives on the parthenon. In S. Blundell & M. Williamson (Eds.), The sacred and the feminine in ancient Greece (pp. 47–70). Routledge.

- Bonfante, L. (2011). Classical and Barbarian. In L. Bonfante (Ed.), The Barbarians of Ancient Europe: Realities and interactions (pp. 1–36). Cambridge University Press.

- Bothmer, D. V. (1957). Amazons in Greek art. Clarendon Press.

- Brooten, B. J. (1996). Love between women: Early Christian responses to female homoeroticism. University of Chicago Press.

- Bychowski, M. W. (2016). The Island of Amazons: The medieval place of transgender. http://www.thingstransform.com/2016/04/the-island-of-amazons-medieval-place-of.html.

- Corso, A. (2023). The front of a temple and swimming girls by the andokides painter (around 520 BC). Acta Archaeologica, 93(1), 111–118. https://doi.org/10.1163/16000390-20210020

- Davis-Kimball, J., & Behan, M. (2002). Warrior women: An archaeologist’s search for history’s hidden heroines. Warner Books.

- Demangel, R. (1923). “Un nouvel alabastre du peintre Pasiades.” Fondation Eugène Piot: Monuments et mémoires 26, 67–97.

- Dodson, D. (2024). Amazons among Us: Reflections on creating the heroines we need now. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 28(2), pp. 1-19, https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2024.2303903.

- Dowden, K. (1997). The Amazons: Development and functions. Rheinisches Museum Für Philologie, 140(2), 97–128.

- Du Bois, P. (1982). Centaurs and Amazons: Women and the pre-history of the great chain of being. University of Michigan Press.

- Elman, A. (1996). Triangles and tribulations: The politics of nazi symbols. Journal of Homosexuality, 30(3), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v30n03_01

- Feinberg, L. (1996). Transgender warriors: Making history from Joan of arc to Dennis Rodman. Beacon Press.

- Ford, S.-J. (2024). Archives and Amazons: A quilter’s guide to the lesbian archive. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 28(2), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2024.2313381.

- Fowler, M. A. (2023). Rosa Bonheur the Amazon? Equestrianism, female masculinity, and The Horse Fair. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 28(2), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2023.2261698

- Gleba, M. (2008). You are what you wear: Scythian costume as identity. In M. Gleba, C. Munkholt, & M.-L. Nosch (Eds.), Dressing the past. Oxbow Books, pp. 13–28.

- Goldberg, M. Y. (1998). The Amazon myth and gender studies. In K. J. Hartswick & M. C. Sturgeon (Eds.), Stephanos: Studies in honor of Brunilde Sismondo Ridgway (pp. 89–100). University of Pennsylvania Museum.

- Ivantchik, A. I. (2013). Amazonen, Skythen und Sauromaten: Alte und modern Mythen. In C. Schubert & A. Weiss (Eds.), Amazonen zwischen Griechen und Skythen: Gegenbilder in Mythos und Geschichte (pp. 73–87). de Gruyter.

- Lear, A., & Cantarella, E. (2008). Images of ancient Greek pederasty: Boys were their gods. Routledge, Taylor&Francis Group.

- Lissarague, François. (1990). “Uno sguardo ateniese.” In Georges Duby and Michelle Perrot (Eds), Storia delle donne, vol. 1: L’antichità, (pp. 179–240). Laterza.

- Liu, J. (2022, October 19). Who’s afraid of Rosa Bonheur’s sexual identity? Hyperallergic. https://hyperallergic.com/771626/whos-afraid-of-rosa-bonheurs-sexual-identity/.

- Mayor, A. (2014). The Amazons: Lives and legends of warrior women across the ancient world. Princeton University Press.

- Meixner, G. (1995). Frauenpaare in kulturegeschichtlichen Zeugnissen. Verlag Frauenoffensive.

- Morales, H. (2007). Classical Mythology: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press.

- Oliver, J. (2023). Acca soror: Queer kinship, female homosociality, and the Amazon-huntress band in Latin literature. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 28(2), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2023.2294676

- Parisinou, E. (2002). The ‘language’ of female hunting outfit in ancient Greece. In L. Llewellyn-Jones (Ed.), Women’s dress in the ancient Greek world (pp. 55–72). Duckworth and the Classical Press of Wales.

- Penrose, Jr., W., (2014). Sappho’s shifting fortunes from antiquity to the early renaissance. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 18(4), 415–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2014.897922

- Penrose, Jr., W., (2016). Postcolonial Amazons: female masculinity and courage in ancient Greek and Sanskrit literature. Oxford University Press.

- Pistone, A. (2024). Lesbian nation is Amazon culture: Lesbian separatism and the uses of Amazons. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 28(2), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2024.2309057

- Pomeroy, S. B. (1995). Goddesses, whores, wives, and slaves: Women in classical antiquity. Schocken Books.

- Rabinowitz, N. (2002). Excavating women’s homoeroticism in ancient Greece: The evidence from vase painting. In N. Rabinowitz & L. Auanger (Eds.), Among women: From the homosocial to the homoerotic in the ancient world (pp. 106–166). University of Texas Press.

- Rabinowitz, N. (2024). Queer and/or lesbian?: Amazons in Christa Wolf’s Cassandra. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 28(2), pp. 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2024.2309056.

- Risch, E. (1974). Wortbildung der homerischen Sprache. Walter de Gruyter.

- Robey, Molly K. 2019. Androgynes, Amazons, agenes: Transgender studies and the college girl, 1878. Legacy, 36(1), 65–86. https://doi.org/10.5250/legacy.36.1.0065

- Rolle, R. (1986). Die Amazonen in der archäologischen Realität. In J. Kreutzer (Ed.,), Kleist-Jahrbuch 1986: Im Auftrage des Vorstandes der Heinrich-von-Kleist-Gesellschaft (pp. 38–62). Erich Schmidt.

- Rolle, R. (1989). The world of the Scythians (F. G. Walls, Trans.). University of California Press.

- Rolle, R. (2010). Tod und Begräbnis: Nekropolen und die bisher erkennbare Stellung von Frauen mit Waffen. In Amazonen: Geheimnisvolle Kriegerinnen (pp. 113–117). Historisches Museum der Pfalz Speyer Minerva.

- Shapiro, H. A. (1983). Amazons, Thracians, and Scythians. Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 24(2), 105–114.

- Stevens, C. (2000). Symbols. In B. Zimmerman (Ed.), Lesbian histories and cultures: An encyclopedia (1st ed.). Garland Publishing.

- Taylor, T. (1996). The prehistory of sex: Four million years of human sexual culture. Bantam Books, pp. 747–48.

- Teleaga, E. (2010). Die Prunkgräber aus Agighiol und Vraca. In Amazonen: Geheimnisvolle Kriegerinnen (pp. 78–85). Historisches Museum der Pfalz Speyer Minerva.

- Vaness, R. (2002). Investing the Barbarian? The dress of Amazons in Athenian art. In L. Llewellyn-Jones (Ed.), Women’s dress in the ancient Greek world (pp. 95–110). Duckworth and the Classical Press of Wales.

- Wagner-Hasel, B. (2002). The graces and color weaving. In L. Llewellyn-Jones (Ed.), Women’s dress in the ancient Greek world (pp. 17–32). Duckworth and the Classical Press of Wales.

- Walker, B. G. (1988). The women’s dictionary of symbols and sacred objects. Harper & Row.

- Williams, C. (2014). Transgender. TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly, 1(1–2), 232–234. https://doi.org/10.1215/23289252-2400136