Abstract

A recurrent theme in the geosciences is the persistent need for more student demographic diversity, especially in academic programs. A strategy to make the geosciences inclusive and motivating for one marginalized group may not succeed with another, requiring the search for new approaches. The Geoscience Ambassadors, an extracurricular program for undergraduate and graduate students at The University of Texas at Austin, explored the value of involving students in the essential work of social and cultural transformation in the geosciences. The program aimed to empower the next generation of geoscientists to learn about, communicate and challenge ideas about what it means to be a geoscientist. Students explored their unique pathways into the geosciences using an autobiographical narrative approach. In taking on the role of Geoscience Ambassador, students translated their pathway experiences into influential personal stories and inspirational videos tailored for different audiences, and they designed a changemaking activity for a community of their choice. Evaluation addressed program implementation and program value to students using participation metrics, participant observation, participant interviews, and a focus group. Value was identified in the impact on ambassadors’ personal growth: self-efficacy, geoscience identity, leadership identity, sense of accomplishment, and satisfaction with their perceived impact on their chosen community. We conclude that with preparation and guidance, students can be empowered to play a critical role in changing the geosciences by sharing their pathway stories, mentoring other geoscience students, and engaging in social and cultural transformation. We propose design principles for refining and adapting the approach to changemaking in other contexts and at scale.

Purpose and learning goals

Despite decades of discourse and action in pursuit of diversity, equity and inclusion in the geosciences (Gillette, Citation1972; Williams, Citation2018), the geosciences remain less successful than other sciences in recruiting students from historically marginalized groups (Callahan et al., Citation2017; Carter et al., Citation2021). Efforts to attract students to the geosciences in the United States have often emphasized outdoor experiences. Considered by many to be central to a foundational geoscience education (Kastens et al., Citation2009; Mosher et al., Citation2014, Waldron et al., Citation2016; Whitmeyer et al., Citation2009), evidence gathered from practicing geoscientists and pre-college studies of both historically marginalized and white students point to positive outdoor experiences as key factors in influencing career choice or the decision to major in geoscience (LaDue & Pacheco, Citation2013; Levine, et al., Citation2007; Stokes et al., Citation2015).

Approaches to recruiting in geosciences have begun to shift, however, with increased appreciation of the diversity of research settings of contemporary, interdisciplinary geosciences and the different ways these field learning settings are experienced by women and historically marginalized communities (e.g., Posselt & Nuñez, Citation2022; Stokes et al., Citation2015). A recent study by Carter et al. (Citation2021) questions the use of outdoor field experiences as a primary recruiting strategy. The authors report that altruistic values motivate current historically marginalized undergraduate college students in their choice of study area. These students cited “helping people and society” and “helping the environment” as being the most important factors that they weigh when considering an “ideal” career. If the argument put forth by Carter et al. (Citation2021) has merit, then implementing new approaches that complement outdoor experiences may help reduce the “persistent underrepresentation of minoritized Hispanic, Black, African American, or Native American students” (Carter et al., Citation2021, p. 3).

People with disabilities (PwDs) are also underrepresented in the geosciences (Carabajal et al., Citation2018). They comprise the largest historically marginalized population in the U.S., with the reported percentage of PwDs in the U.S. population ranging from 19.4 to 25% (Carabajal et al., Citation2018; Chakraborty, Citation2021). The continued emphasis on field-based training may disadvantage some PwDs. In the past decade, geoscience education researchers have promoted innovative technology-driven approaches and new instructional strategies, including virtual learning environments, to remove barriers to inclusion for students with disabilities (Carabajal et al., Citation2018).

Radically new solutions are needed to ensure that all students, including historically marginalized Hispanic, Black, African American, or Native American students, and those with a physical or sensory disability, feel welcome in the geosciences and aware of the variety of career opportunities encompassed by geoscience practice. This paper describes a new program, Geoscience Ambassadors, which was launched in fall 2018 in the Jackson School of Geosciences at The University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin) as part of a Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) Undergraduate Science Education grant in the Professors Program.

Conceived as an extracurricular program structured to extend over the fall and spring semesters, the goals of Geoscience Ambassadors were twofold:

Develop Transformational Geoscientific Identities: support a diverse cohort of undergraduate and graduate student geoscientists as they crafted personal narratives that strengthened their relation to the discipline as well as their commitment to changemaking and outreach to historically marginalized communities; and

Empower Action for Change: empower the next generation of geoscientists to learn about, communicate, challenge and redesign cultural norms and ideas about what it means to be a geoscientist through their storytelling and outreach activities of their own design.

Design and theory of change

We know that structured approaches to pipeline and pathway formation can lower barriers to access to geoscience programs, but they are not on their own enough to promote engagement and persistence in the field, particularly among students from historically marginalized groups (Núñez et al., Citation2020; Ormand et al., Citation2022). Researchers and designers of STEM learning experiences have more recently turned their attention to the cultivation of disciplinary identity as a project of critical educational significance, examining how the cultural norms and practices that characterize STEM disciplines play into the subjective, affective processes of interest and identity development (Azevedo & Mann, Citation2022; Bang & Medin, Citation2010; Bell et al., Citation2017; Gee, Citation2000; Nasir & Saxe, Citation2003; Semken et al., Citation2017; van der Hoeven Kraft et al., Citation2011). Scientists are trained to be technically articulate researchers. From a sociocultural perspective, geoscience educators who seek to expand and diversify their discipline must do much more than promote the mastery of technical skills or understanding of scientific concepts among their students; they must also support “identity learning,” that is, the values-based work of developing a meaningful, deep, durable and potentially critical relationship with their discipline, its history, and its possible futures. Engaging students in the formation of geoscientific identities that speak to broad audiences in socially and ethically articulate ways allows them to see themselves in their discipline and to know how and why to change the discipline for the better.

Storytelling, story listening and the crafting of narratives are important ways that humans make sense of themselves (their identities) and the world (e.g., their disciplines and the role they should play). The stories we tell others about ourselves (e.g., as members of certain groups, as “good” or “bad” students, or as scientists of one sort or another) interweave reasoning about what is true about ourselves and the world, what Bruner (Citation1986) would call paradigmatic or logico-scientific sensemaking, with reasoning about how to find meaning and value in our experience, that is, narrative sensemaking. To the extent that stories plausibly convey both truth and meaning to others, they can be powerful organizers of the sensemaking and activity of others (Boje, Citation2011; Lejano et al., Citation2013; Orr, Citation1996; Weick, Citation1995). From a critical perspective, changing a historically exclusive, inequitable and unjust science involves–in part–the crafting of plausible, meaningful, and powerful counternarratives (Solórzano & Yosso, Citation2002) that push against the grain of the status quo sensemaking about scientific disciplines and scientists.

The Geoscience Ambassadors program was therefore designed to help students draw stories from their own experiences that speak in powerful and influential ways about who they are in relation to their discipline, inviting more diverse engagements with the geosciences and repatterning the geosciences in ways that make it more hospitable and relevant. Throughout the program, ambassadors reflected upon their identity, where they came from, barriers, pivotal experiences and tensions they had experienced, and ultimately crafted authentic, video-based "changemaking stories" that narrated their personal journey into the geosciences in a way that spoke effectively to an identity group or home community to which they felt connected.

The Geoscience Ambassadors program embodied a model for change centering on an understanding of self and empathy for others, used storytelling, empowered students to identify and research their “home” communities or those with which they identify, and design a changemaking activity for that community. Ultimately, the program aimed to create a new cohort of leaders with the ability to share their unique stories and broaden the understanding and appreciation of geosciences in diverse communities.

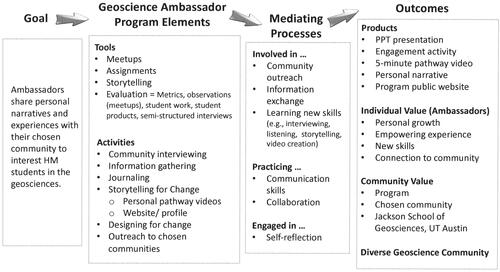

Our theory of change framework (), articulated in terms of a conjecture map (Sandoval, Citation2014), illustrates the connections between the design elements of the program, the mediating processes and expected outcomes. The framework was used flexibly in context, evolving in response to factors influencing processes that lead to the desired outcomes. The framework guided evaluation and served as a model against which to test hypotheses and determine which actions and interventions best produce the results (Taplin & Clarke, Citation2012).

Figure 1. Conjecture map for the theory of change developed in the geoscience ambassadors program. Structure modified after Sandoval (Citation2014).

Author positionality

Geoscience Ambassadors mobilized a multi-cultural, multi-generational, and ethnically diverse group of four program leaders with expertise in science teaching, geoscientific research, and educational research. Author KKE is a geoscience educator from Jamaica, a country with a predominantly mixed-race, multi-ethnic population. LJL, a French national, has a background in evolutionary biology and was a postdoctoral fellow during program implementation. Prior to joining the Jackson School, he conducted research work in France and South Africa. AP is a white, male learning scientist who has studied and designed for learning in a variety of disciplines. JAC is an evolutionary paleobiologist whose early diagnosis of a learning disability and tensions around disclosure have influenced her career pathway. Geoscience Ambassadors was a part of her program design proposal for the HHMI Professors Program. Due to their backgrounds and professional position within the university and discipline, the authors were likely perceived by many participating students as different from them. More importantly, the authors found that they learned about the meaning and power of their own pathway narratives in the context of the program. Each found that in working with each other and with students, they were able to surface aspects of their personal experience and identity that could be brought to bear on the design and implementation of the program, and each learned the importance of sharing aspects of their own counternarratives with students as a way of demonstrating their commitment to promoting change through vulnerability and the recognition of value in difference.

Study population and setting

The Jackson School of Geosciences runs a large doctoral-granting geoscience program at an R1 public university and is home to the Geoscience Ambassadors program. Geoscience Ambassadors were intentionally recruited by disseminating program information to the whole student body of the Jackson School via email, presentations at student groups, in classrooms and lab meetings. Recruitment materials emphasized assembling “a new cohort of geoscience leaders ready to use their unique stories to broaden understanding and appreciation of the geosciences.” The program’s specific interest in engaging communities representing historically marginalized groups was conveyed in both a description of the status of diversity in the geosciences included in the program advertisement materials and characterization of the ambassador role as “leaders for change.” Students filled out an application form which asked, among other things, their enrollment status, where they come from, a community of identity they might want to engage as an ambassador, a “message” for that community, why they wanted to be an ambassador, what would make them good at it, and how an ambassadorship would fit in with their professional and academic goals. Application materials stated that participants would receive a small stipend.

The recruiting and selection process resulted in 37 participants in three annual cohorts. Cohorts were intentionally limited in size (∼ 12 students) to allow participants to get to know each other and build trust. In terms of gender and racial/ethnic identification, these ambassadors were significantly more diverse than the student body of the Jackson School of Geosciences and the field of professional Geoscientists (). Ambassadors identified variously as Black, Hispanic, and students of color; persons with disabilities; transgender; gay; veterans and active members of the armed forces; first generation college students; representatives of rural communities; and international students. Overall, 54.1% of the ambassadors were undergraduates, and 45.9% were graduate students.

Table 1. Diversity in the geoscience ambassadors program relative to school, university, state, and national populations. HM stands for “historically marginalized,” that is, racial and ethnic identity groups that have historically been designated by the national science foundation as underrepresented in STEM fields, namely individuals who identify as hispanic, black or African American, or Native American. Participants’ gender was categorized based on self-reporting. These categories have been chosen for the purpose of rough statistical comparison with populations (i.e., school, university, discipline), and are not meant to reflect programmatic priority or preference relative to other identity groups.

In the first year, cohort 1 (2018–2019) participants met in person biweekly for two hours in the evening with the program leaders, which included a postdoctoral fellow (LJL). The setting was a small lecture room where students could build trust and feel comfortable sharing. The program leaders emphasized norms required for critical, dignity-affirming talk and action (respect, responsibility, confidentiality, and care). Only program team members and participants were present. Food and drinks were provided. In the second year (2019–2020), cohort 2 began meeting in person but the COVID-19 pandemic abruptly forced the program online in spring 2020, creating instructional challenges compounded by the personal and academic adjustments required of cohort 2 participants. To accommodate the reality of an ongoing pandemic, we suspended the program for one year and reorganized it as a hybrid in-person/online endeavor with increased schedule flexibility for cohort 3 (2021–2022) participants. The hybrid approach included online Zoom and in-person meetings. We shortened the length of the program to allow students to settle into the fall semester and to accommodate spring final exams. We also reduced meeting times from 2 to 1.5 h. The hybrid approach was successful initially, but the winter 2021 surge associated with the COVID Omicron variant forced program delivery back online and limited Ambassadors’ in-person outreach.

Materials and implementation

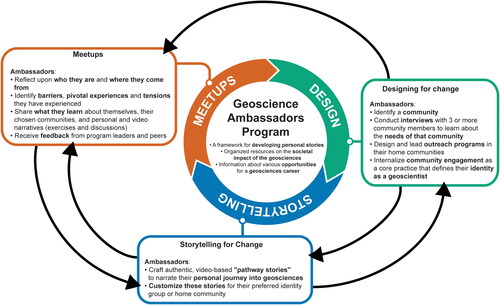

Geoscience Ambassadors had three main complementary program components with overlapping themes (): (1) Meetups for Active Community Building, (2) Storytelling and (3) Designing for Change.

Figure 2. General diagram of the three main overlapping components in the geoscience ambassadors program. Arrows indicate interactions between these components as developed by Ambassadors when crafting their personal stories.

Meetups for active community building

Geoscience Ambassadors activities were organized around informal meetups scheduled over the fall and spring semesters. Established as an extracurricular activity, attendance at meetups was expected but could not be required. The Canvas learning management system was used as a way of presenting meeting agendas and design activities expected for completion before the meetups and a place for participants to post reflections and report on community interviewing and outreach activities.

The meetups allowed participants to share and learn from each other, build community, and ultimately become empowered to effect change. We reviewed the Geoscience Ambassadors program goals, explained the rationale for the program, and discussed the geosciences as a field, emphasizing who geoscientists are, what they do, and why during the first meetup. The emphasis at the outset was on encouraging participants to get to know themselves and each other. As the program progressed, we introduced the concept of storytelling for change and prepared students to interview members of a community with which they identified and for whom they intended to design an engagement activity. During the second half of the program (spring semester), we guided the development and implementation of individual or small group outreach activities and supervised participants’ creation of personal web pages and video narratives.

An example of a two-semester schedule of meetups with descriptions of activities, recommendations for pre-meetup preparation and post-meetup assignments is included as Appendix A in the Supplementary Materials.

Storytelling

Central to the program was the use of storytelling by participants to help them understand their own experiences and translate it into a compelling personal narrative that is relatable to others. Storytelling and story-listening are important across cultures and for all ages and levels of learners, functioning as critical processes for re-organizing power relations in ways that support individual and community life (Barajas-López & Bang, Citation2018; Bruner, Citation1991; Gee, Citation1985; Marin et al., Citation2020).

Pathway mapping

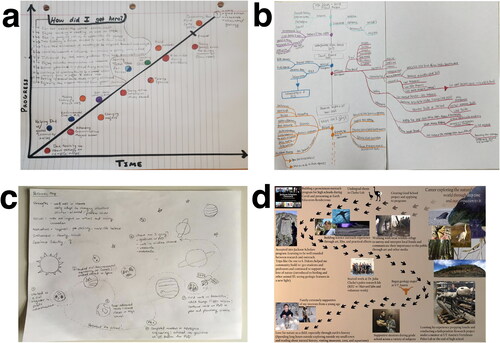

As a first step toward framing their personal narratives, each ambassador created a pathway map as an individual assignment to address three broad questions: (1) How did I get here? (2) Where am I going? and (3) How will I get there? The mapping exercise encouraged ambassadors to identify their unique attributes and lived experiences and understand how these motivated them to embark on a career in the geosciences. and were compiled to show ambassadors examples of elements that they might include on a pathway map. We encouraged ambassadors to be creative—to draw, sketch, scheme, and scribble in whatever way helped them to think about and represent their own personal journey. During meetups, ambassadors could share their pathway maps with others; they also engaged in exercises to help them further define their identities. features four different ambassadors’ pathways maps showing the range of approaches taken.

Figure 3. Examples of pathway maps designed by geoscience ambassadors during the program. ambassadors either drew maps by hand (a–c) or designed it as an image file (d).

Table 2. Pathway elements considered by students when answering question ‘(1) How did I get here?’.

Table 3. Pathway elements considered by students when answering questions ‘(2) Where am I going?’ and ‘(3) How will I get there?’.

Ambassadors have a variety of attributes, experiences and perspectives, some of which are deeply personal and may even evoke past trauma. We counseled them to consider the audience and context and disclose only those elements or parts of their story that they were comfortable sharing. Over time, developing a supporting community helped students feel comfortable sharing. Each person’s story is rich, complex and changes with time. Ambassadors could choose to deploy different aspects of their stories in different contexts to make an empathetic connection with the audience.

Community interviewing

Once ambassadors identified a community with which they had an affinity, we used the meetups to guide participants to explore how they could learn more about these communities. Ambassadors identified whom they could interview to learn about their selected communities and determined how to contact them. Ideally, ambassadors conducted interviews with at least three different community representatives. Ambassadors interviewed directors of diversity initiatives, museum administrators, youth program leaders, educators, and people serving in the military. The interviews helped them gather information on how the geosciences are perceived as a science and profession, gain insight into meaningful ways to connect communities to the geosciences and learn how community members could be better supported while pursuing an education or career in geosciences. Some ambassadors reconnected with inspirational figures they identified as thought leaders from their chosen communities. Each ambassador created an interview script with questions for each of their interviewees. shows examples of questions, grouped in three categories, that ambassadors asked interviewees. The semi-structured interviewing tools and techniques used by ambassadors were informed by Merriam and Tisdell (Citation2016).

Table 4. Example template used by ambassadors for community interviewing. Selected examples from geoscience ambassadors’ interview scripts (Ellins et al. Citation2021).

Refining changemaking narratives

In meetups, students were introduced to the notion of a counternarrative (Solórzano & Yosso, Citation2002), which for the purposes of this program we define as a story that is rooted in authentic personal experience that pushes back against status quo understandings (and misconceptions) about what the geosciences are and who gets to be a geoscientist. Using their pathway maps and written reflections on their community interviews as a raw material, ambassadors began to iteratively craft, share and refine their own counternarratives. This storytelling process was initiated with reflective prompts like:

What are unique aspects to your pathway story?

What “tensions” in your life have driven you over time along your pathway?

How did you grapple with these tensions, resolve them, or how do they still drive you?

What “characters,” events, circumstances or aspects of society cause these tensions, or help you deal with or resolve them?

Who/what has helped you learn, change, adapt, see things differently, or make decisions along your pathway?

What about your pathway experience might others relate to?

What have you learned through dealing with your “tensions” that others should know?

What aspects of your story may go against our normal understanding of where you come from, what the geosciences are, or how or why one becomes a geoscientist?

In what ways might your story change people, change the field?

Students initially worked out stories in a quick and low-stakes fashion by talking through them with each other at meetups, then they moved on to refining them in written form through reflection and feedback, and eventually producing them as 2 to 5-min video stories, which were workshopped in groups. Feedback on stories addressed the following:

Are potential audiences clear?

Are messages clear?

Is the story engaging?

What opportunities for connection and change do you see in the story?

What do you like?

What was confusing, or what could be improved or clarified?

What would you like to know more about?

Ultimately, students posted video versions of their stories for change to a personal page on the Geoscience Ambassadors website. They provided written and key takeaways by summarizing their “pathway” and articulated what was “surprising” about their story (i.e., what pushed against status quo understandings), and what lessons they wanted to share (i.e., how they wanted others to learn from and change through their story).

Designing for change

Community interviewing informed ambassadors’ work designing and implementing targeted outreach, education, or engagement activities. Cohorts 1 and 2 worked on individual outreach programs. Cohort 3 ambassadors worked individually or in small teams of participants who shared similar goals and perspectives. Ambassadors received a small award ($500) to cover the costs associated with their outreach activities and to support their time participating in the program. Ambassadors used hands-on science activities, lectures, web-based apps, and online platforms to reach their intended audiences. Ambassador-led outreach activities took place in schools, museums, social and church groups, extended family gatherings, science cafes, organizations for students with disabilities, military veteran groups, teacher professional development programs, and an online pre-college summer enrichment STEM program. Due to COVID-19 disruptions, some cohort 3 ambassadors created websites with geoscience career information, content for museum visitors and online lessons for use by middle school science teachers. Cohorts 1 and 2 ambassadors tracked the number of individuals interviewed and the size and type of audiences reached through their community outreach. Each ambassador’s final product for the program is a written synthesis of activities and a video narrative, uploaded to their webpage on the Geoscience Ambassadors website. As they shared their stories and carried out their outreach activities with their chosen communities, ambassadors documented their work on their personal pages on the program website (https://www.geoscienceambassadors.net).

Evaluation

Our evaluation focused on (1) understanding and documenting value and (2) monitoring implementation for ongoing adaptation of the program model and theory. Per the initial purpose and learning goals, the Geoscience Ambassadors program sought to generate both short- and long-term value for students and communities of identity with which they engaged. Therefore, Wenger et al. (Citation2011) value assessment framework was used to structure an evaluation of the program at five different “stages” (). We used several types of qualitative approaches and data (), following Creswell (Citation2003). UT Austin’s Institutional Review Board approved the evaluation study (Study #: 2018080116).

Table 5. Geoscience ambassadors program value creation organized into the stages of the value assessment framework (Wenger et al., Citation2011).

Table 6. Data sources and types.

Data collection

Data for evaluation were collected from five different sources (). Interviews and focus groups were used to collect specific value creation narratives from participants, that is, highly personalized participant accounts of the value that was created by the program based on their own experience and perceptions. Other narratives were collected in field notes and memos by the first and third authors acting as participant observers. Artifacts of participant learning and creativity in the program were collected via Canvas (UT Austin’s learning management system), on the project’s collaboratively constructed Google Sites website, and in a shared set of Google Drive folders used by participants to organize program activities. Program and process metrics were assembled for each year, and included: number of applicants, demographics, number accepted, their participation in meetups, the number of profile pages and video stories produced, the number of changemaking projects designed and implemented, and estimates of the number of people engaged and types of audiences (provided by ambassadors).

Interviews

Semi-structured participant interviews were informed by a constructivist/interpretive paradigm (Creswell, Citation2003; Denicolo et al., Citation2016; Merriam & Tisdell, Citation2016). The authors KKE and ASP organized the interview questions into three categories, focusing on (1) the value of the program to individual participants, their chosen community (participants’ perceptions), and to others, such as fellow students (participants’ perceptions); (2) the value of participation in informing their geoscience identity, their definition of a geoscientist, and perceptions about the geoscience community and their relationship to this community; and (3) the program’s effect on personal and professional growth. (The interview script and organizational framework are included in the Supplemental Materials, Appendix B). We probed for narratives of value creation in these three categories and related the findings to the five stages of the value assessment framework as shown in .

Interviews lasting 45 min were conducted (by author KKE) with cohort 1 (n = 10) and cohort 2 (n = 4) ambassadors via Zoom after they had completed the program. A responsive interviewing technique (Rubin & Rubin, Citation2005) was used because the interviewer was deeply involved in the program as a facilitator and participant observer, and had established relationships with participants. All interviews were recorded and transcribed. Author KKE took detailed notes during the interviews.

Focus group and artifacts

Only four cohort 2 ambassadors participated in the interview process because of COVID-19 disruptions in 2020. In response to these challenges organizing interviews and to supplement the relatively small sample of individual interviews, data on value created by the program was also collected via a focus group discussion and review of ambassadors’ drafts of reflections and personal narratives, website profiles, and video stories. A Zoom focus group was conducted with cohort 3 participants using questions in the interview guide to prepare the discussion.

Data analysis

Author KKE relied on her detailed notes taken during the interviews and the focus group discussion to relate the opinions and ideas expressed by participants to a priori codes based on the value assessment framework (see ) and the interview guide (Supplemental Materials, Appendix B). Transcripts of the interviews and the focus group discussion were checked to clarify points of confusion or provide additional information about interview responses. Recurring phrases, key points, and ideas within each participant’s responses were highlighted. Comparing all participants’ responses allowed author KKE to identify the similarities and the frequencies of recurring words and ideas and assign these to the different a priori codes. Participants’ artifacts were not coded for analysis but reviewed to triangulate with and materially ground participants’ self-reported (interview and focus group data) experience in the program over time. The themes that emerged through comparison were organized in the value creation framework model. Through this process of data collection and ongoing analysis, Author KKE developed iterative qualitative data displays (Miles & Huberman, Citation1994) summarizing indicators of value at each stage of the value creation model.

Per guidance by Creswell and Poth (Citation2018), two different strategies were engaged to enhance trustworthiness of findings in analysis: (1) ongoing member-checking in successive interviews of emergent themes and findings and (2) periodic peer review of themes and findings with members of the research team who were not involved in data collection or analysis of primary data.

Results

In examining the program goals to transform geoscientific identities and empower action for change, we analyzed results from both the success of the implementation and the value for the participants within the program. Here we summarize the results. Overall, three cohorts of students were successfully engaged in three iterations of the design. However, details of implementation were adjusted over time by the program team, especially in response to higher-than-expected graduate student interest and experimentation with hybrid modes of (online/face-to-face) programming prompted by COVID-19. We found diverse indications of novel value generated through participation in the program. Our assessment of the implementation and value of the program focused on the engagement of, and outputs produced by, the ambassadors themselves. Audience response to the Ambassadors’ interventions in their respective home communities could not be comprehensively evaluated (except for feedback from ambassadors), since these interventions took place over an extended period of time in many different locations. The level of data collection and analysis that would have been required to evaluate these outputs was beyond the scope and funding of the program.

Program implementation and adaptation

We observed the three components of the program (meetups, storytelling, and design) working in an integrated fashion as designed: The ambassadors actively participated in meetups, enthusiastically giving and receiving feedback on their personal narratives and outreach designs. We noted that this personal and potentially sensitive work required familiarity and trust among cohort members, which was easier to foster when meeting face-to-face and in smaller numbers (of 12 to 15 participants). We also observed in meetups and drafts of stories and reflections that the storytelling undertaken by students in the Geoscience Ambassadors program promoted deep reflection about self, community, and the discipline. Students drew intricate pathway maps showing how they became geoscientists and used them to imagine how their own stories would play out into the future (). They crafted and shared refined “versions” of their stories for the purpose of sharing knowledge, influencing community perceptions about the geosciences, and inspiring marginalized students to consider the field as a career. We observed students citing their community interview experiences, using what they learned to inform storytelling goals and messages, and integrating goals, lessons and community contacts identified through interviewing and in meetup discussions and group work to design and implement novel changemaking activities.

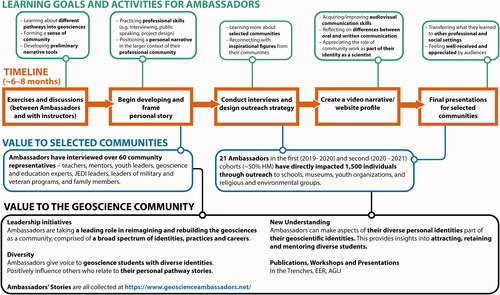

In the end, 26 of 37 ambassadors recruited for cohorts 1, 2 and 3 completed the Geoscience Ambassadors program, ultimately producing 26 short video stories and accompanying website profiles, and 10 novel outreach activities. Cohort 1 (2018–2019) included one graduate and nine undergraduate students, and cohort 2 (2019–2020) comprised seven undergraduate and five graduate students. While originally designed for undergraduates, year 1 recruitment revealed considerable interest from graduate students. They applied to the program at higher rates than reflected in the admitted cohorts. The inclusion of graduate students was found to be beneficial because it allowed the more experienced graduate students to work as near-peer mentors to undergraduates, and the program was adjusted to engage proportionally more graduate students than initially anticipated. By cohort 3 (2021–2022), four of the nine participants who completed the program were graduate students .

Figure 4. Extended timeline of the geoscience ambassadors program for a given cohort, from the first meeting to final presentations by ambassadors. Boxes branching off from the main timeline (in orange) show goals and activities (in green) for Ambassadors at each step of the program, and outputs of value to targeted communities outside the program (in blue and black).

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which began in March 2020, required a shift from in-person meetups to online sessions for cohort 2. Despite increased schedule flexibility, the emergence of COVID-variants in 2021 and 2022 further challenged our ability to deliver the planned program. Cohorts 2 and 3 both saw challenges of participation and attrition that were not seen in cohort 1, as pandemic-affected ambassadors dealt with isolation that affected their ability to attend meetups, collaborate, share, and build trust. Eleven participants dropped out, citing competing obligations and heavy course workloads.

Program value

We found indicators of program value for participants, communities and the discipline across all five value creation stages defined by Wenger, et al. (Citation2011; ). Details are provided in a data display in Appendix C in Supplemental Materials.

Stage 1. Immediate value: Activities and interactions

Ambassadors saw their experience in the program activities and interactions as clearly and immediately valuable (Supplemental Materials, Appendix C, Stage 1). For example, they appreciated the opportunity to form a supportive community and connect with others, and they enjoyed sharing aspects of themselves and linking their own histories and pathways into the geosciences with the experience of others. They found interview and outreach interactions with their communities valuable as well, with some respondents reporting that the program helped them “reconnect” with their communities in important ways. One ambassador commented, “Once I retired from the army, I did not want to go back and didn’t want anything to do with the army again” but added that the program encouraged him to reconnect with the military community and show them how they could continue “Service to Country” via careers in the geosciences. Overall, interviews and observation data revealed that ambassadors had a positive immediate reaction to the designed activities. They appreciated the program structure that supported community engagement and reported feeling welcome, appreciated and gratified by audience interest and curiosity.

Stage 2. Potential value: Knowledge capital

In addition to the immediate positive experience reported by participants, ambassadors also perceived longer-term value in terms of their own knowledge gains, professional development, networks and capacities for continued learning, and the development of resources (Supplemental Materials, Appendix C, Stage 2 A). Specifically, meetups helped participants learn to communicate about themselves and their science, expand their understanding of what counts as a geoscientist and how one becomes a geoscientist, and change their impression of what aspects of themselves were important to their geoscientific identity and practice. One ambassador, for instance, realized that she “should incorporate more of her art into her meandering pathway and that this was really a strength” to share with others. Another ambassador learned to see how important parts of her history and identity–her work ethic and creativity she developed as a dancer–contributed to her geoscientific identity and practice.

Ambassadors also made progress in becoming deeper, more central participants in their geoscientific communities, reporting gains in social capital, including new friendships, a deeper connection to the Jackson School’s geosciences department, and forming new group friendships through project work (Supplemental Materials Appendix C, Stage 2B). By sharing stories, ambassadors “become more than just college colleagues” and found the “voice to express” themselves as people in their academic program and in the field more. They developed new resources and assets for their continued development as ambassadors, including their changemaking stories, presentations for outreach and novel educational materials (Supplemental Materials, Appendix C, Stage 2 C). The Geoscience Ambassadors website hosts ambassadors’ video stories, personal narratives, and information about changemaking interventions for others to learn from. Ambassadors led workshops with program leaders (Ellins et al., Citation2021; Papendieck et al., Citation2021), delivered presentations at professional geoscience meetings (Campos et al., Citation2022; Ross et al., Citation2020), and contributed to a practitioner-oriented article about Geoscience Ambassadors (Ellins et al., Citation2021). Ambassadors valued being positioned as role models through the program, representing both the discipline and the Jackson School (Supplemental Materials, Appendix C, Stage 2D).

The program helped ambassadors build confidence, hone public speaking abilities, and develop interviewing skills that transformed their abilities to learn about communities (Supplemental Materials Appendix C, Stage 2E). They reported learning to be mindful about presenting themselves to reach different audiences and recognized the value of a cohesive narrative to inspire others to consider the geosciences as a career. The program improved ambassadors’ willingness to learn more about increasing the participation of more individuals from marginalized groups in the geosciences, as evidenced by some ambassadors reporting a deeper appreciation of diversity, equity and inclusion issues and a need to investigate or act on them.

Stage 3. Applied value: Changes in practice

Not only did ambassadors react positively to their experience and report advances in knowledge and the ability to learn and grow as geoscientists, but we also found indications that the experience led to changes to their day-to-day practice and behaviors (Supplemental Materials Appendix C, Stage 3). Ambassadors reported becoming active leaders and advocates for the geosciences in diverse group contexts, such as scouts, faith-based youth groups, and the GeoLatinas outreach group. They shared their messages about the geosciences in museums, schools, churches, social service organizations, and with their families and friends. They reported that their time in the program influenced how they wrote applications for graduate schools, and how they thought about and approached science practice as something that is linked to communication, policy and education.

Stage 4. Realized value: Performance improvement

The long-term theory of change of the Geoscience Ambassadors program is that by fostering deeper geoscientific identities among marginalized students and preparing and supporting them as designers of equity- and inclusivity-oriented changemaking interventions, the program will substantially impact the culture and composition of the field. While we cannot yet reliably assess the longer-term performance of the program, we did see the program make important progress in testing and supporting its theory of change (Supplemental Materials, Appendix C, Stage 4).

We saw that ambassadors’ professional identities evolved from narrowly focused (e.g., geologist, geochemist, computation scientist) to the broader identity of geoscientist or Earth scientist. Ambassadors also embraced an expanded definition of a geoscientist as a person with various attributes, abilities, skills, and creative talents that can be leveraged in the geosciences. In some cases, ambassadors reexamined their career goals, choosing to remain on their path or to realign career aspirations to match their identities better. One ambassador learned what interested her and applied this realization to completing a master’s degree conducting research in the Caribbean, collaborating with colleagues who closely resembled members of her chosen community. Another said she realized that she “doesn’t want to stay in academia” and wants to work in science policy.

Ambassadors created a wide variety of stories that linked diverse aspects of their identity to a commitment to the geosciences. We saw one ambassador, for instance, craft a changemaking story that combined his Christian identity with his geoscientific identity in a way that rationalized a commitment to caring for the Earth and to supporting young people who feel pressure to choose between science and faith. Such stories are meaningful, if early, indications that the program helps ambassadors cultivate transformational geoscientific identities, that is, identities that are both deeply embedded in the field and deeply committed to changing the field and how it is perceived. Ambassadors’ video stories and personal narratives on the program website reached 1,500 individuals through their community outreach. While documenting community response to outreach was beyond the scope of the evaluation, we know that their stories have been taken up in a variety of other programs and workshops. During the COVID pandemic, for instance, the Jackson School’s historically marginalized-serving GeoFORCE program used an ambassador-created series of virtual field trips in their delivery of online instruction as part of a weeklong summer program for high school students. In addition, ambassadors’ video stories were shared with teacher participants of UT Austin’s Petroleum Science and Technology Institute in the summers of 2019 and 2021.

Stage 5. Reframing value

Finally, participating in the Geoscience Ambassadors program fundamentally challenged notions of value for many participants, as well as program leaders. While the Geoscience Ambassadors program was initially organized by goals of “outreach” to marginalized geographic communities, it became immediately clear in the initial set of applicants that the program’s value was broader, and the planned activities could be organized to engage a wide variety of communities of identity. Indeed, the reflective processes of storytelling and story listening represented ideal ways to identify the most salient communities of identity for ambassadors to engage.

A second major shift in the way value was understood related to the direction or target of engagement emphasized by the program. Over the course of implementation, participants and program leaders alike began to move beyond outreach, and more clearly conceptualize and design for value through what they called “inreach.” For program leaders, inreach complemented work to engage and change how “external” or marginalized communities perceived and related to the geosciences by carefully organizing work for “internal” changes to both self and discipline. At the level of the individual student, inreach is considered identity work, that is, students reflecting on who they are, which aspects of themselves are and are not traditionally valued as part of a geoscientific identity, and how unique aspects of their intersectional identities position themselves as good scientists and as changemakers in the disciplines.

At a disciplinary level, inreach involved reflecting on established structures, routines, culture and practices that characterize and maintain the geosciences. While Geoscience Ambassadors primarily engaged students in this critical reflection and changemaking in the discipline, as program leaders refined the model and activities, they began to see potential value in engaging more established geoscientists situated in influential culture-norming institutions (e.g., professional societies, industry employers, and academia).

Finally, at a high-level, our experience with the geoscience Ambassadors program caused us to re-think how students are valued, empowered and positioned in many large-scale and established programs focused on influencing the culture and composition of the field. Both student participants and program leaders developed a deeper appreciation and understanding of the value of students not just as supporters of, contributors to or beneficiaries of established agendas and programs, for instance, but in engaging them to articulate and prioritize new issues of diversity, equity and inclusion, and in empowering them to frame, reframe and act upon these issues in new ways (Supplemental Materials, Appendix C, Stage 5).

Discussion

What can we say about the value of the Geoscience Ambassadors program, and how it might be further refined and adapted to promote intertwined processes of (1) geoscientific identity development (goal 1) and (2) empowering action for change (goal 2)? We first discuss evidence of unique value, before articulating some lessons we have learned about how the program works as a model that might be refined and adapted.

Novel value to students: Transforming identities

Evaluation results show that students see novel value in participation. One of the most important ways that students found value in the program was as an opportunity to think, write and talk in ways that helped them make progress in developing what we have called transformational geoscientific identities. Such intersectional identities weave together diverse understandings of self and others in ways that both edify a commitment to the discipline and motivate and rationalize a conviction to make it better, more just and more inclusive. The identity work and learning required to construct such transformational identities involves weaving together considerations of and accountabilities to different communities, places, affinity groups, professions, histories, cultures, and values.

The Geoscience Ambassadors program is one example of how storytelling, counternarratives, and design can engage students in the long-term but influential work of identity learning. Other educators will likely see these and other pedagogies that link identity work to action for change in their own educational work with students, pedagogies that could be taken up, described and refined for systematically developing students who are committed to the discipline and know what they want to do to make it new. Going forward, for example, this design team intends to further study how identity work combines both retrospective sensemaking and prospective changemaking in ways that allow students to reason about the relationship between who they are, what their discipline is, and what they want it to be. We know others are working in similar directions (see, for example, contributions to the recent AGU session ‘Understanding and Enhancing Science Identity As a Strategy to Broaden Participation In STEM’ convened by Christensen et al., Citation2022).

Novel value of students and others at the margins: Empowering students for change

We also find that the program specifically positioned, prepared and empowered students as communicators and mediators of the relationship between geoscientific disciplines and communities that have historically been marginalized and excluded from them. In valuing students as important changemakers, the Geoscience Ambassadors program presents novel value to communities and the geosciences as a discipline. We know that persistent inequity and lack of diversity in the geosciences is more than a structural issue of access to programs and resources; it is also a deeply cultural and historical issue. This means that programs and policies that impact visibility of and access to geoscientific academic and career pathways may have only limited potency. The Geoscience Ambassadors program is one example of a program that organized and prepared students and other individuals at the margins or periphery of the discipline to learn about and sustain the difficult, long-term, but essential work of social and cultural change. Programs like Geoscience Ambassadors which link critique and productive action for cultural change can provide an essential complement to important and more established outreach and educational initiatives in the geosciences that work to communicate and break down barriers to access academic and professional pathways, such as the AGI Career Compasses and Geoscience Resources on Opportunities in the Workforce (GROW: https://www.grow-geocareers.com/home.html). We would like to see more programs that legitimize students as change agents with something important to say and do about the culture and composition of the field.

Lessons and resources for design and adaptation

Evaluation of the implementation process revealed that meetups, storytelling and intervention design function as an integrated set of activities that can be flexibly implemented to engage both undergraduate, graduate students and potentially others. We view our experience with the Geoscience Ambassadors as an ongoing, experimental case of a model that links student identity learning with discipline-focused change. Rather than specifying a hard and fast model or sequence of lessons, we note that the materials we have assembled appear to promote a variety of valuable processes for learning and change, and that specific designed activities could be replaced with others that promote similar processes. Therefore, to refine and adapt this model, we emphasize the importance of designing activities and programs that promote and integrate the following general processes:

Community-building: In the Geoscience Ambassadors program, meetups were used to establish an environment that was intentionally separated from the social pressures of the discipline, but also focused on the discipline. This allowed students to reflect upon their own relationship to the field and treat it as both valuable as well as questionable. Meetups were organized by an ethic that promoted open and respectful discussion of sensitive and deeply personal issues. In scaling or adapting this design, we stress the importance of establishing these spaces for critique, reflection and the formation of new solidarities, what other educators and researchers have called, for example, counterspaces (e.g., Ong et al., Citation2018).

Identity work: Storytelling was deployed in the Geoscience Ambassadors program as a way of weaving holistic, intersectional understandings of self and discipline together for sensemaking and changemaking. Community interviewing contributed to identity development by building empathy for and understanding of diverse communities and cultures, and also how those communities relate to self and science. In designing the Geoscience Ambassadors program, we conceptualized identity pedagogy as creating opportunities for students to gradually and iteratively position themselves, others, their communities, and their discipline per socially, culturally and ethically salient categories (Gee, Citation2000; Varelas et al., Citation2012). Our appreciation of identity work as a narrative process (Bruner, Citation1986; Gee, Citation2000) of self-authoring led us to storytelling and the production of counternarratives (Solórzano & Yosso, Citation2002), but there are many ways to develop learning environments and experiences that promote equitable disciplinary identification (e.g., Bell et al., Citation2017), and there are many geoscience educators who are deploying the construct of identity in other ways to design for change in the field (e.g., Christensen et al., Citation2022).

Change work: The Geoscience Ambassadors program organized student-led design of programs as a way of putting student counternarratives and visions of alternative, more inclusive disciplinary futures into action. This kind of action-oriented work could be organized in other ways, implemented in other disciplinary contexts and in different settings, and over shorter time periods. While the Geoscience Ambassadors program was inspired by principles of human-centered design and co-design (Lee, Citation2008; Roschelle & Penuel, Citation2006), critical and action-oriented strategies for empowering students and marginalized individuals for social and disciplinary change have deep and substantial roots in critical pedagogy (Freire, Citation2000).

In designing similar programs, designers must recognize that the highly personal and potentially sensitive nature of the storytelling work and the complex nature of intervention design both depend upon building a strong and trusting community. While the richness and immediacy of face-to-face interactions in small cohorts can help build this, we learned that the program can function with a percentage of the interactions done online via videoconferences. A model for a hybrid or distributed version of the program might take an “executive format,” for instance, emphasizing an intensive period of face-to-face community-building interactions, followed by an online phase that brings efficiency to collaboration and feedback, and concluding with a return to a face-to-face setting in order to share work and shore up social cohesion before the cohort disperses. We recommend program implementers have a plan in place to address interpersonal conflict resolution and ensure that students get the care they need to support their revisiting of potential trauma should the need arise.

Workshop resources (Ellins et al., Citation2021; Papendieck et al., Citation2021) and a Storytelling for Change Toolkit (Clarke et al., Citation2023; see also https://www.geoscienceambassadors.net/education/storytelling-for-change) are available for others interested in potentially implementing similar programs or elements of the changemaking model at their institutions. This collection of open educational resources was designed for potential adaptation to classrooms, recruiting events, lab meetings, workshops, conferences, or wherever students and scientists may be comfortable learning and sharing together. The tools help students and scientists engage in a reflective and creative process of storytelling, a process that strengthens and grounds scientific identity and positions them for change in the field. By broadly sharing the curricular resources and ambassadors’ stories created through this program, we hope there will be a longer-term impact on the geosciences as the participants move into careers and positions of leadership and their changemaking stories and identities gain power and influence.

Limitations

A limitation of the study is the potential bias introduced by the self-selection of individuals into an extra-curricular program that emphasized outreach to marginalized populations. This selection bias resulted in a representation of historically marginalized populations as Geoscience Ambassador participants that differed systematically from other Jackson School of Geosciences students. Such a difference, while a limitation, also served the goal of the program to showcase the diverse backgrounds of its participants, and emphasizes the need for greater discussion and empowerment of geoscientists from historically marginalized communities. In practice, the hybrid approach implemented in response to the COVID-19 interruptions was also a program limitation; however, it offered insights to improve program delivery in the future.

The evaluation plan was designed to produce trustworthy, particularized and contextualized knowledge about a novel program case and any novel value it generated. The legitimacy of lessons drawn to inform educational programming or learning in other contexts is dependent upon the degree to which that context is analytically similar (Yin, Citation2014) to the context within which this program was implemented. Due to the small size of the cohorts of ambassadors, the program evaluation did not focus on making statistical claims about outcomes among participating students, nor did the evaluation claim to sample representativeness required for generalizability to other groups. Finally, while the ambassadors’ stories have been shared, we do not know how many people have seen them, nor is the timeframe of our evaluation capable of producing clear evidence of long-term individual and disciplinary change. We did not conduct formal surveys of the online audience for ambassadors’ videos, nor of the audience reached by ambassadors through their in-person changemaking interventions.

Implications

The Geoscience Ambassadors’ video stories and profiles help dismiss the perception that there is a single, linear, appropriate or normal path toward a geoscience degree or career (National Academies of Sciences et al., 2011). The braided stream geoscience workforce career model captures the many varied ways in which individuals enter the geosciences and maps out how careers evolve with new opportunities, interests, personal responsibilities, and lifestyle choices (Batchelor et al., Citation2021), but not how individuals are drawn to geosciences in the first place, or what students may want to say or do to change their disciplinary destination. The program examined in this paper challenges us to think more creatively about how students experience pathways into and within the geosciences, and what students can do to organize and communicate new pathways to new disciplinary spaces for themselves and others. While documenting the clear impact of ambassadors’ video stories and outreach is beyond the program’s scope, our evaluation results show that this type of program did reach historically marginalized populations and engage students in integrating and designing for marginalized identities and communities. We suggest that with preparation and guidance, students can potentially play a critical role in the geosciences by sharing their pathway stories, mentoring other geoscience students, and engaging in social and cultural transformation through program and intervention design, for instance. To that end, we are collaborating beyond the Jackson School to design and conduct in-depth research on models that integrate Geosciences Ambassadors and its pedagogies into an existing national program that will link community-building, identity work and change work. Our work suggests that there is particular value in intentionally empowering and supporting students in “outreach” to engage and welcome specific populations, and “inreach” to change the culture and norms of the discipline itself.

Ms. No. UJGE_2022-0065_SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIALS.docx

Download MS Word (41.8 KB)Acknowledgements

We express our sincere gratitude to the Geoscience Ambassadors who willingly gave their time and effort to inspire others to follow their lead and make a difference in their communities. We thank the GSA OTF workshop leaders for deploying the pathway mapping activity in a different context, and the mentors and participants for demonstrating its potential in career preparation. We also gratefully acknowledge the thoughtful comments of the anonymous reviewers and journal editors; their knowledgeable feedback helped us improve this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Azevedo, F. S., & Mann, M. J. (2022). An investigation of students’ identity work and science learning at the classroom margins. Cognition and Instruction, 40(2), 179–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370008.2021.1973007

- Bang, M., & Medin, D. (2010). Cultural processes in science education: Supporting the navigation of multiple epistemologies. Science Education, 94(6), 1008–1026. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.20392

- Barajas-López, F., & Bang, M. (2018). Indigenous making and sharing: Claywork in an indigenous STEAM program. Equity & Excellence in Education, 51(1), 7–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2018.1437847

- Batchelor, R. L., Ali, H., Gardner-Vandy, K. G., Gold, A. U., MacKinnon, J. A., & Asher, P. M. (2021). Reimagining STEM workforce development as a braided river. Eos, 102. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021EO157277

- Bell, P., Van Horne, K., & Cheng, B. H. (2017). Special issue: Designing learning environments for equitable disciplinary identification. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 26(3), 367–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2017.1336021

- Boje, D. M. (Ed.). (2011). Introduction to agential antenarratives that shape the future of organizations. In Storytelling and the future of organizations: An antenarrative handbook (pp. 1–19). Routledge.

- Bruner, J. (1986). Actual minds, possible worlds. Harvard University Press.

- Bruner, J. (1991). The narrative construction of reality. Critical Inquiry, 18(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1086/448619

- Callahan, C. N., LaDue, N. D., Baber, L. D., Sexton, J., van der Hoeven Kraft, K. J., & Zamani-Gallaher, E. M. (2017). Theoretical perspectives on increasing recruitment and retention of underrepresented students in the geosciences. Journal of Geoscience Education, 65(4), 563–576. https://doi.org/10.5408/16-238.1

- Campos, D., Clarke, J., Ellins, K. K., & Papendieck, A. (2022). Navigating through turbulence in STEM higher education: Geoscience Ambassadors personal pathway storytelling. Geological Society of America Annual Meeting, South-Central Section, McAllen (TX). https://doi.org/10.1130/abs/2022SC-374161

- Carabajal, I. G., Marshall, A. M., & Atchison, C. L. (2018). A synthesis of instructional strategies in geoscience education literature that address barriers to inclusion for students with disabilities. Journal of Geoscience Education, 65(4), 531–541. https://doi.org/10.5408/16-211.1

- Carter, S. C., Griffith, E. M., Jorgensen, T. A., Coifman, K. G., & Griffith, W. A. (2021). Highlighting altruism in geoscience careers aligns with diverse US student ideals better than emphasizing working outdoors. Communications Earth & Environment, 2(1), 213. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-021-00287-4

- Chakraborty, J. (2021). Social inequalities in the distribution of COVID-19: An intra-categorical analysis of people with disabilities in the U.S. Disability and Health Journal, 14(1), 101007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.101007

- Christensen, A., Hubenthal, M., Rowe, S. R. M. (2022). Understanding and enhancing science identity as a strategy to broaden participation in STEM. Education Section, Annual Meeting of the American Geophysical Union, Chicago (IL). https://agu.confex.com/agu/fm22/meetingapp.cgi/Session/165645

- Clarke, J. A., Papendieck, A., & Ellins, K. K. (2023). Storytelling for change kit. Texas Data Repository. https://doi.org/10.18738/T8/9MAW8X

- Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). SAGE Publications, Incs.

- Denicolo, P., Long, T., & Bradley-Cole, K. (2016). Constructivist approaches and research methods. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526402660

- Ellins, K. K., Papendieck, A. S., & Clarke, J. A. (2021). Geoscience ambassadors: A change-making program that is reinventing what it means to be a geoscientist. In the Trenches, 11(1). https://nagt.org/nagt/publications/trenches/v11-n1/index.html

- Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of the oppressed (30th anniversary ed.). Continuum.

- Gee, J. P. (1985). The narrativization of experience in the oral style. Journal of Education, 167(1), 9–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/002205748516700103

- Gee, J. P. (2000). Chapter 3: Identity as an analytic lens for research in education. Review of Research in Education, 25(1), 99–125. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X025001099

- Gillette, R. (1972). Minorities in the geosciences: Beyond the open door. Science, 177(4044), 148–151. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.177.4044.148

- Kastens, K. A., Manduca, C. A., Cervato, C., Frodeman, R., Goodwin, C., Liben, L. S., Mogk, D. W., Spangler, T. C., Stillings, N. A., & Titus, S. (2009). How geoscientists think and learn. Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union, 90(31), 265–266. https://doi.org/10.1029/2009EO310001

- LaDue, N., & Pacheco, H. A. (2013). Critical experiences for field geologists: Emergent themes in interest development. Journal of Geoscience Education, 61(4), 428–436. https://doi.org/10.5408/12-375.1

- Lee, Y. (2008). Design participation tactics: The challenges and new roles for designers in the co-design process. CoDesign, 4(1), 31–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710880701875613

- Lejano, R. P., Ingram, M., & Ingram, H. M. (2013). The power of narrative in environmental networks. The MIT Press.

- Levine, R., González, R., Cole, S., Fuhrman, M., & Le Floch, K. C. (2007). The geoscience pipeline: A conceptual framework. Journal of Geoscience Education, 55(6), 458–468. https://doi.org/10.5408/1089-9995-55.6.458

- Marin, A., Halle-Erby, K., Bang, M., McDaid-Morgan, N., Guerra, M., Nzinga, K., Meixi, Elliott-Groves, E., & Booker, A. (2020). The power of storytelling and storylistening for human learning and becoming. In M. Gresalfi & I. S. Horn (Eds.), The interdisciplinarity of the learning sciences (Vol. 4, pp. 2199–2206). International Society of the Learning Sciences. https://repository.isls.org//handle/1/6512

- Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. Jossey-Bass.

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). Sage Publications, Inc.

- Mosher, S., Bralower, T., Huntoon, J., Lea, P., McConnell, D., Miller, K., Ryan, J., Summa, L., Villalobos, J., & White, L. (2014). Future of undergraduate geoscience education: Summary report for summit on future of undergraduate geoscience education. School of Geosciences Faculty and Staff Publications. http://www.jsg.utexas.edu/events/files/Future_Undergrad_Geoscience_Summit_report.pdf.

- Nasir, N. S., & Saxe, G. B. (2003). Ethnic and academic identities: A cultural practice perspective on emerging tensions and their management in the lives of minority students. Educational Researcher, 32(5), 14–18. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3699876 https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X032005014

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2019). The science of effective mentorship in STEMM. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25568

- National Academy of Sciences (NAS), National Academy of Engineering, and Institute of Medicine. (2011). Expanding underrepresented minority participation: America’s science and technology talent at the crossroads. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/12984

- Núñez, A. M., Rivera, J., & Hallmark, T. (2020). Applying an intersectionality lens to expand equity in the geosciences. Journal of Geoscience Education, 68(2), 97–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/10899995.2019.1675131

- Ong, M., Smith, J. M., & Ko, L. T. (2018). Counterspaces for women of color in STEM higher education: Marginal and central spaces for persistence and success. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 55(2), 206–245. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21417

- Ormand, C. J., Macdonald, R. H., Hodder, J., Bragg, D. D., Baer, E. M. D., & Eddy, P. (2022). Making departments diverse, equitable, and inclusive: Engaging colleagues in departmental transformation through discussion groups committed to action. Journal of Geoscience Education, 70(3), 280–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/10899995.2021.1989980

- Orr, J. E. (1996). Talking about machines: An ethnography of a modern job. Cornell University Press.

- Papendieck, A., Clarke, J., Ellins, K. K. (2021). Storytelling for change in the geosciences [two-day workshop]. Earth Educator’s Rendezvous. https://serc.carleton.edu/earth_rendezvous/2021/program/afternoon_workshops/w14.html

- Posselt, J. R., & Nuñez, A. M. (2022). Learning in the wild: Fieldwork, gender, and the social construction of disciplinary culture. The Journal of Higher Education, 93(2), 163–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2021.1971505

- Roschelle, J., Penuel, W. R. (2006). Co-design of innovations with teachers: Definition and dynamics. Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Learning Sciences, 606–612.

- Ross, C. H., Ellins, K. K., Papendieck, A., & Clarke, J. (2020). Geoscience ambassadors program: Mentoring students in geoscience within home communities [Paper presentation]. Geological Society of America Annual Meeting, South-Central Section, Fort Worth (TX). https://doi.org/10.1130/abs/2020SC-343617

- Rubin, H. J., & Rubin, I. S. (2005). Qualitative interviewing: The art of hearing data (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452226651

- Sandoval, W. (2014). Conjecture mapping: An approach to systematic educational design research. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 23(1), 18–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2013.778204

- Semken, S., Ward, E. G., Moosavi, S., & Chinn, P. W. U. (2017). Place-based education in geoscience: Theory, research, practice, and assessment. Journal of Geoscience Education, 65(4), 542–562. https://doi.org/10.5408/17-276.1

- Solórzano, D. G., & Yosso, T. J. (2002). Critical race methodology: Counter-storytelling as an analytical framework for education research. Qualitative Inquiry, 8(1), 23–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/107780040200800103

- Stokes, P. J., Levine, R., & Flessa, K. W. (2015). Choosing the geoscience major: Important factors, race/ethnicity, and gender. Journal of Geoscience Education, 63(3), 250–263. https://doi.org/10.5408/14-038.1

- Taplin, D. H., Clarke, H. (2012). Theory of change basics: A primer on theory of change, ActKnowledge, Inc. https://www.theoryofchange.org/wp-content/uploads/toco_library/pdf/ToCBasics.pdf.

- Texas Education Agency, Performance Reporting Division. (2020). Snapshot 2020: State totals. https://rptsvr1.tea.texas.gov/perfreport/snapshot/2020/state.html

- van der Hoeven Kraft, K. J., Srogi, L., Husman, J., Semken, S., & Fuhrman, M. (2011). Engaging students to learn through the affective domain: A new framework for teaching in the geosciences. Journal of Geoscience Education, 59(2), 71–84. https://doi.org/10.5408/1.3543934a

- Varelas, M., Martin, D. B., & Kane, J. M. (2012). Content learning and identity construction: A framework to strengthen African American students’ mathematics and science learning in urban elementary schools. Human Development, 55(5/6), 319–339. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26764633

- Waldron, J. W. F., Locock, A. J., & Pujadas-Botey, A. (2016). Building an outdoor classroom for field geology: The geoscience garden. Journal of Geoscience Education, 64(3), 215–230. https://doi.org/10.5408/15-133.1

- Weick, K. E. (1995). Sensemaking in organizations. SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Wenger, E., Trayner, B., de Laat, M. (2011). Promoting and assessing value creation in communities and networks: A conceptual framework. Rapport 18, Ruud de Moor Centrum, Open University of the Netherlands. https://wenger-trayner.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/11-04-Wenger_Trayner_DeLaat_Value_creation.pdf.

- Whitmeyer, S. J., Mogk, D. W., & Pyle, E. J. (2009). An introduction to historical perspectives on and modern approaches to field geology education. In S. J. Whitmeyer, D. W. Mogk, & E. J. Pyle (Eds.), Field geology education: Historical perspectives and modern approaches. The Geological Society of America Special Paper 461 (pp. vii–vix). https://doi.org/10.1130/2009.2461(00)

- Williams, B. M. (2018). Updated diversity and inclusion plan open for member comment. Eos, 99. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018EO107689

- Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research design and methods (5th ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.