Abstract

The task of foster care impacts all members of the fostering family, not least the birth children of foster carers. This systematic review provides a qualitative evidence synthesis of the experiences of birth children and adolescents of foster carers. Utilizing thematic synthesis, data from 15 identified studies were analyzed, with five analytical themes identified: “Responsibility and Power in the Fostering Task,” “Adaptations of the Family System,” “Buffering against the Challenges of Fostering,” “Shaped by the Realities of Fostering,” and “Collaborating with Others beyond the Family.” Themes are discussed in terms of existing research and implications for future research and practice.

Introduction

Foster care was developed to provide care for children who for various reasons, such as neglect or abuse, are unable to remain with their birth families (Ainsworth & Maluccio, Citation2003). Foster care provides a familiar context that supports children’s developmental needs (Gouveia et al., Citation2021), and for either a short-term or long-term basis, offers an intimate and continuous relationship with another family (Ainsworth & Maluccio, Citation2003). Family foster care can produce good outcomes in terms of child functioning and contributes positively to foster children’s development (Humphreys et al., Citation2018; Li et al., Citation2019; Smyke et al., Citation2010).

The task of foster care

Given the adverse and often traumatic experiences that children entering foster care have typically experienced, they may struggle with emotional, behavioral, and relationship difficulties (Ainsworth & Maluccio, Citation2003). Children in foster care are at greater risk of mental health difficulties, often experiencing emotional and behavioral problems (Minnis et al., Citation2006). Foster placement instability may compound such difficulties (Rubin et al., Citation2007), and contribute to further relational trauma, highlighting the importance of social services’ task to ensure the stability of foster placements. Foster carers also carry significant responsibility in caring for the children placed with them (Blythe et al., Citation2014) and are an important determinant in child outcomes (Sinclair & Wilson, Citation2003).

Unsurprisingly, providing foster care has been recognized as a complex and challenging task (Vanderfaeillie et al., Citation2016). Foster carers must contend with challenges such as the placement of unrelated foster children, frequent placement disruption and replacement, visits from the foster child’s birth family, impermanent emotional relationships, and intrusion on family privacy (Ainsworth & Maluccio, Citation2003). Furthermore, the emotional and behavioral problems often experienced by foster children can place additional strain on foster carers (Cooley et al., Citation2015; Farmer et al., Citation2005). Problems in recruiting and retaining foster carers have been identified internationally (Blythe et al., Citation2014; Gouveia et al., Citation2021; Rodger et al., Citation2006). A relevant factor in placement disruptions and continuation of fostering appears to be the presence of foster carers’ own children in the home. Research has demonstrated positive associations between the presence of foster carers’ biological children and placement instability (Kalland & Sinkkonen, Citation2001; Rock et al., Citation2015). Foster carers often experience concerns about the impact of fostering on their biological children (Poland & Groze, Citation1993) with conflict between biological and foster children cited by some foster carers as the reason for discontinuation of their role (Rhodes et al., Citation2001). However, the exact impact of biological children in foster families remains unclear, with Sinclair et al. (Citation2005) indicating that the effects of the presence of birth children are complex as in some situations, they were found to be helpful. Thus, while research is ambivalent about their effects, clearly, the carers’ birth children are important and relevant to the task of fostering.

Understanding the impact on and influence of foster carer’s birth children

A systemic perspective illuminates how fostering may impact upon and be influenced by foster carers’ birth children. The family system is conceptualized as dynamic and co-evolving with its environment (Hayes, Citation1991). From within, it is shaped by members’ development and their relationships with each other (Hayes, Citation1991; Minuchin, Citation1974). Unlike the semi-closed modern nuclear family, the foster family is an open system. However, too much change and too much openness can be damaging to the system’s wellbeing and sense of identity (Eastman, Citation1979). For foster families, the arrival of a foster child and their social workers causes stress to the system and requires the family to appropriately adapt and transition (Eastman, Citation1979). Successful foster families require a balance between a strong sense of identity established through appropriately rigid boundaries, and the ability to manage frequent and unpredictable changes in family composition and expectations (Eastman, Citation1979).

The entry of a foster child into the family may bring difficulties similar to those identified with the arrival of a birth sibling. The birth of a sibling is a challenging adjustment, with research linking it to increased adjustment problems in firstborn children (Stewart et al., Citation1987). From a psychoanalytic perspective, it has been theorized that the birth of a new sibling can be a threatening crisis, as the older sibling is faced with the realization that they are not unique, with a new other threatening their place in the family (Mitchell, Citation2013). For fostering families, such changes may be made more complicated due to recurring disruption and role change, with family reorganization occurring as a continual process.

Additionally, what is known about foster carers’ experiences of fostering reveals implications for how fostering may impact on the birth children in the home. As highlighted earlier, the task of fostering brings many stressful challenges. Parental stress is associated with various adverse outcomes including parental mental health difficulties, less effective parenting, and increased child behavior problems (Neece et al., Citation2012). Thus, it is possible that through the impact of the stress of the fostering task on the parents, the wellbeing of the birth children in the home may be impacted.

Foster carers’ birth children: current literature

It has become clear that fostering may impact the birth children of foster carers in significant and complex ways. Furthermore, it appears that the presence of birth children influences the fostering task, although the literature seems inconclusive regarding how birth children affect fostering and placements. While research addressing the birth children of foster carers has been limited in comparison to that which explores foster carers or foster children (Williams, Citation2017), there is a growing body of literature focussing on this population. This literature predominantly consists of exploratory, qualitative research exploring the experiences of birth children of foster carers. These studies tend to have small samples, sometimes which consist of children (Spears & Cross, Citation2003), sometimes which consist of adults retrospectively giving accounts of their childhood experiences (Williams, Citation2017), and sometimes combinations of both populations (Poland & Groze, Citation1993).

In a bid to further the understanding of birth children’s experiences of living with foster siblings, Thompson and McPherson (Citation2011) systematically reviewed the literature and conducted a thematic analysis on studies capturing the experiences of birth children aged between three and 32 years. However, the age span of participants is a limitation of this review as the inclusion of the experiences from such a broad range of ages may skew the findings regarding what it is like to be the birth child of a foster carer. Thus, although the review highlighted potentially relevant themes such as loss, conflict, and positive experiences, data pertaining to both children and adults were synthesized together, making it impossible to conclude what experiences were specific and relevant to the child population.

Rationale for the current review

In light of the above, a comprehensive review and synthesis of existing research focusing on the experiences specific to foster carers’ birth children, and only including those who were children and adolescents at the time of data collection, may further progress the developing understanding and knowledge regarding the impact upon and influence of birth children living in fostering families. It appears that a gap exists for such a review. The current review addresses this gap, focussing on reviewing and synthesizing data relating specifically to the birth children and adolescents of foster carers. As research exploring the birth children of foster carers is predominantly exploratory and qualitative in nature, a qualitative evidence synthesis (QES) seems warranted.

The aim of the current review was to identify, assess, and synthesize evidence from qualitative studies of the biological children and adolescents of foster carers’ regarding their experiences of living in a foster family. In the current review, the World Health Organization’s (WHO, n.d.) definitions of childhood and adolescence were used to define children and adolescents as individuals aged up to 19 years. The review was guided by the following question: “What are the experiences of the birth children and adolescents of foster carers, of living in fostering families?”

Methods

The RETREAT (Booth et al., Citation2018), criteria-based review was used to identify the most suitable approach to this synthesis. Based on these criteria, Thomas and Harden’s (Citation2008) thematic synthesis approach was chosen. The “Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ)” statement (Tong et al., Citation2012) was used in this review to facilitate comprehensive reporting. A review protocol was preregistered on PROSPERO (CRD42021293483; https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=293483).

Search strategy

The SPIDER (sample, phenomenon of interest, design, evaluation, research type) framework (Cooke et al., Citation2012), was used to guide question development, search strategy, and the study selection process. Early scoping work, initial limited searches, and consultation with a subject specialist librarian, also informed the key terms and search strategy. Five databases were searched: Child Development and Adolescent Studies, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL Plus), International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (IBSS), PsycINFO, and Scopus. Key search terms included variations of the following terms: Biological child; natural child; own child; birth child; foster; foster carer; and foster parent. Search terms were applied in line with database-specific methods and no limits or filters were applied to the database searches. Database searches were completed in January 2022. Studies identified for inclusion were searched using a forward and backward strategy to identify additional, potentially relevant studies (Horsley et al., Citation2011).

Study selection

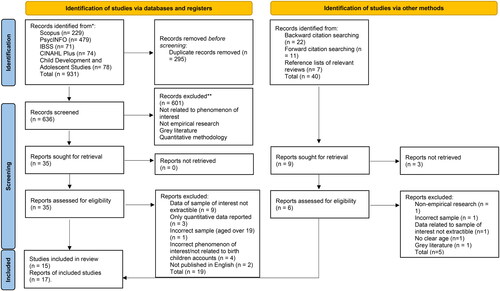

All studies retrieved through the database searches were exported to reference management software EndNote 20, where duplicates were removed. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review () were used to create a screening tool. The screening tool was initially piloted by the lead author and a second reviewer on the title and abstracts of a sample of 30 studies, to ensure comprehensive understanding of the inclusion and exclusion criteria by both reviewers (Boland et al., Citation2017). The title, keywords and abstract of all studies were then screened by the lead author using the screening tool to assess eligibility for inclusion. A sample of the studies (20%) was also independently screened by the second reviewer at this stage.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria used to screen studies.

For the second stage of screening, the full text of all the papers identified as potentially relevant by one or both screeners were retrieved. These were then reviewed independently by the lead author and the second reviewer for eligibility. Reviewers had 100% agreement at both title and abstract stage and at full-text screening stage. Where the same study, using the same sample and methods, was presented in different reports, these reports were collated so that each study, rather than each report, was the unit of interest in the review. The PRISMA flow chart (Page et al., Citation2021) displayed in Appendix A displays the search results and the process of screening and selecting studies for inclusion.

Quality appraisal

Two review authors independently assessed methodological limitations for each study using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme qualitative checklist (CASP, Citation2018). The CASP is a 10-item tool for assessing the strengths and limitations of any qualitative research methodology (Long et al., Citation2020) and is endorsed by both Cochrane and World Health Organization guideline processes (Long et al., Citation2020; Noyes et al., Citation2018).

Data extraction

A pre-designed data extraction form was used to record data extracted from each study. As informed by relevant guidance (Noyes et al., Citation2018; Thomas & Harden, Citation2008) the data extracted from the studies included descriptive information about the study and participants, information about the methodology, and the study findings. In the current review, first-order data (i.e., verbatim extracts from participants) and second-order data (which includes themes and interpretations by the author), that reflected the review question were extracted. These findings were taken from the sections of the studies labeled “results” or “findings.” In line with existing guidance (Noyes et al., Citation2018; Thomas & Harden, Citation2008), the abstracts and sections labeled “discussion” or “conclusion” were also checked for findings. Data extraction was completed independently by two review authors.

Synthesis

Thomas and Harden’s (Citation2008) thematic synthesis approach was used to synthesize the relevant qualitative data extracted from the included studies. This comprised of three stages which were completed by the lead author. The first stage consisted of free “line by line” coding and axial coding of the data. These codes were then organized into related areas to develop “descriptive themes.” The final stage consisted of the generation of “analytical themes,” which led to the production of new interpretations that answered the review question. The processes of coding and theme generation were discussed in supervision with two review authors. NVivo software (Release 1.6.2; QSR International Pty Ltd, 2022) was used to support analysis at all stages of the synthesis and to enhance transparency and provide an audit trail (Houghton et al., Citation2017). Analytical themes were broken into subthemes to reflect core findings.

The GRADE-CERQual approach was used to assess confidence in each of the review findings (Lewin et al., Citation2018). Four components were assessed as part of this approach: Methodological limitations, coherence, adequacy of data, and relevance.

Review author reflexivity

The lead author is epistemologically positioned by a critical realist perspective, which holds that knowledge of reality is mediated by perceptions and beliefs. The lead author is not a foster parent, nor a biological child of a foster parent. Furthermore, the lead author has no experience of being a child placed in foster care. However, in line with quality standards for rigor in qualitative research, the lead author considered her views and presumptions regarding the biological children of foster carers as potential influences on the decisions in conducting the study. The lead author also considered how the results of the study may have influenced those views and opinions. These were extensively explored through reflexivity and supervision. Progress with the review was regularly discussed among the review authors with critical exploration of decisions made. Two authors have previous experience in qualitative evidence synthesis, and the lead author regularly engaged in supervision with these members regarding the process, ensuring rigor when completing the review. In supervision, all members remained mindful of presuppositions and worked together to minimize the risk of these biasing the review processes.

Results

Summary of included studies

The PRISMA flow chart (Page et al., Citation2021) displayed in Appendix A displays the search results and the process of screening and selecting studies for inclusion. Searches retrieved a total of 931 studies, of which 295 duplicate records were removed. A total of 636 records were screened, with 35 of these reports sought for retrieval and assessed for eligibility in the review. From these, seventeen reports pertaining to fifteen studies were identified for inclusion in the review (Adams et al., Citation2018; Höjer, Citation2007; Kaplan, Citation1988; Martin, Citation1993; Njøs & Seim, Citation2019; Nordenfors, Citation2016; Ntshongwana & Tanga, Citation2018; Raineri et al., Citation2018; Reed, Citation1994, 1996–1997; Rees & Pithouse, Citation2019; Roche & Noble-Carr, Citation2017; Spears & Cross, Citation2003; Stoneman & Dallos, Citation2019; Sutton & Stack, Citation2013; Targowska et al., Citation2016; Twigg, Citation1994). The studies were conducted between 1988 and 2019. Seven of the studies were conducted in the United Kingdom (UK), two in Australia, and one each in the United States of America (USA), Canada, Italy, Norway, South Africa, and Sweden. The studies appeared to capture experiences relating to fostering as implemented by authority systems and operated by independent agencies. Participants were aged from 4 years upwards. Seven studies used interviews to collect data, one used discussion groups, and another used focus groups. The remaining six studies integrated various forms of data collection including interviews, focus groups, and drawings. Eight studies had included the views of individuals other than the sample of interest and the data relating to those views were not extracted for inclusion in this review. A range of methodologies were utilized for study design and analysis. Three studies utilized interpretative phenomenological analysis, two studies reported using thematic analysis, two used content analysis, and one employed a grounded theory approach. Two studies described their analysis as theme generation, another study reported that data were analyzed qualitatively, and one study reported their analysis to include categorization of data and examination for presence of psychoanalytic constructs. Three studies did not detail analysis method. The study characteristics are displayed in .

Table 2. Characteristics of included studies.

Quality appraisal of the included studies

The quality of the included studies was assessed independently by two review authors, with 91% agreement between the two reviewers. Disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third review author. The results of the quality appraisal of the studies are displayed in . The quality of the included studies was mixed. All had clearly stated aims for which qualitative methodology was appropriate. The studies largely provided rich data pertaining to the birth children’s experiences. Most studies did not provide information relating to the impact of the researcher on the research. Some studies lacked detail regarding the data analysis method. Detail evidencing consideration of ethical issues were not available in some studies.

Table 3. CASP tool quality appraisal.

The results of the quality appraisal demonstrated that it was not always possible to assess items due to a lack of detailed information in the study reports. This may be because of space limitations in publications and may represent the published report rather than the quality of the research. Studies were not excluded from the review as a result of the quality appraisal, as each study had the potential to add valuable insights to the review. However, the methodological rigor of each contributing study was considered in the assessment of confidence of each review finding.

Thematic synthesis

Five analytic themes emerged from the analysis, each containing analytic subthemes. These are discussed below, accompanied by extracts from the primary studies. A summary of the analytic themes and subthemes are displayed in , alongside the GRADE-CERQual assessment of confidence. Additional information regarding which studies contributed to each theme is available upon request from the authors.

Table 4. Summary of qualitative findings.

Responsibility and Power in the Fostering Task

This theme captures the studies that reported biological children’s gains of responsibilities through the fostering task and reflects that despite these responsibilities, the degree of inclusion in decision making and preparation for fostering varied.

Children as carers

Across 11 studies it was evident that the biological children assumed active caring roles in the fostering task. Seven studies detailed how the children engaged in practical caretaking tasks with foster children such as helping with homework, cooking for them, and safeguarding internet usage (Nordenfors, Citation2016; Ntshongwana & Tanga, Citation2018; Raineri et al., Citation2018; Reed, Citation1994, 1996–1997; Roche & Noble-Carr, Citation2017; Spears & Cross, Citation2003; Stoneman & Dallos, Citation2019). Six studies reported how the biological children provided emotional care and support to their foster siblings (Adams et al., Citation2018; Nordenfors, Citation2016; Raineri et al., Citation2018; Roche & Noble-Carr, Citation2017; Stoneman & Dallos, Citation2019; Targowska et al., Citation2016). “Birth children considered themselves an “active part of the foster care,” and they explained in detail the ways in which they helped, including collaboration in everyday life, help with schoolwork, and cuddling for babies” (Raineri et al., Citation2018, p.628).

Two studies (Kaplan, Citation1988; Reed, Citation1994, 1996–1997) specified that it tended to be the older children in their sample who spoke of this caretaking role.

Eight studies reported positive feelings related to these caregiving roles, such as pride, enjoyment, achievement, satisfaction and gaining value through providing care to the foster siblings (Adams et al., Citation2018; Raineri et al., Citation2018; Reed, Citation1994, 1996–1997; Roche & Noble-Carr, Citation2017; Spears & Cross, Citation2003; Stoneman & Dallos, Citation2019; Sutton & Stack, Citation2013; Targowska et al., Citation2016).

Children actively contributed to providing a caring home environment for foster children and were proud of their ability to assist someone who was in need: ‘I feel proud and kind just in general that I’m doing it and that I’m helping this person’ (YC). (Roche & Noble-Carr, Citation2017, p. 70)

Three studies reported positive gains from caregiving responsibilities such as enhanced development through learning to be independent and responsible from an early age and learning how to take care of children (Ntshongwana & Tanga, Citation2018), development of relational and caring skills (Roche & Noble-Carr, Citation2017) and improved self-esteem, (Stoneman & Dallos, Citation2019).

It was documented in three studies that caregiving duties could be experienced negatively, particularly if tasks were perceived as burdensome, demanding, or restrictive (Roche & Noble-Carr, Citation2017; Reed, Citation1994, 1996–1997; Stoneman & Dallos, Citation2019). Six studies captured how the children’s sense of caring responsibility prompted worry for the welfare and wellbeing of the foster children (Adams et al., Citation2018; Ntshongwana & Tanga, Citation2018; Raineri et al., Citation2018; Reed, Citation1994; Stoneman & Dallos, Citation2019; Sutton & Stack, Citation2013).

The active caring role in the foster family often extended to include assumption of caring responsibilities toward their parents. In seven studies it was apparent that the children were attuned to the negative impact of fostering on their parents, the stress and strain it could cause and sometimes worried about the impact of the task on them (Adams et al., Citation2018; Nordenfors, Citation2016; Raineri et al., Citation2018; Reed, Citation1994; Spears & Cross, Citation2003; Sutton & Stack, Citation2013; Targowska et al., Citation2016). Interestingly, in the study by Sutton and Stack (Citation2013), these concerns were limited to mothers only. An attunement to the parents needs often led to children minimizing their own needs, putting parents’ feelings and needs before their own, sometimes due to not wanting to add to their parents’ difficulties or make them feel guilty for the impact of the fostering task (Adams et al., Citation2018; Kaplan, Citation1988; Nordenfors, Citation2016; Raineri et al., Citation2018; Reed, Citation1994; Sutton & Stack, Citation2013; Targowska et al., Citation2016).

The caring responsibility toward foster children appeared to overlap with the duty of care evident toward parents, with five studies reporting that children felt they held responsibility to support their parents in their role (Adams et al., Citation2018; Ntshongwana & Tanga, Citation2018; Reed, Citation1994, 1996–1997; Spears & Cross, Citation2003; Targowska et al., Citation2016).

Sophie spoke similarly about feeling the need to help her parents if they were having any problems with the foster children: ‘I don’t want my mum just to have to deal with it all or my dad.’ She felt an obligation to help her parents as a result of staying attuned to their needs. (Adams et al., Citation2018, p. 145)

Inclusion in decision-making and preparation for fostering

Despite the documented responsibilities that many studies reported children gained through fostering, the inclusion of the children in the preparation and decision-making related to fostering varied.

Four studies reported that some biological children felt involved in discussions and planning for fostering by their family (Njøs & Seim, Citation2019; Raineri et al., Citation2018; Spears & Cross, Citation2003; Targowska et al., Citation2016) while five studies reported experiences of children not being included in decision to foster (Ntshongwana & Tanga, Citation2018; Raineri et al., Citation2018; Roche & Noble-Carr, Citation2017; Stoneman & Dallos, Citation2019; Targowska et al., Citation2016). Targowska et al. (Citation2016) reported how even though consultations were often limited in that children felt pressure to agree to fostering, inclusion at this stage was still beneficial:

Despite the limitations of parent-guided discussions, biological children in the sample who were included in such discussions in the initial stages of fostering reported feeling more in control, and seemed more willing to accept fostering than those children who were not included in the consultation process: ‘at the start I was a little like ‘I don’t really want to’, because I thought I would be like pushed to decide, but no, I wasn’t, so we talked it through lots, and I thought cool, it sounded decent’. (p. 32)

Children recalled being informed of their parents’ intentions to foster but experienced uncertainty or false expectations about what this entailed. The children’s knowledge around fostering was expressed as coming from experience rather than preparation: ‘Mum said, ‘When you come back there’ll be some children here’ and I was like ‘What does that mean?’ and she said, ‘Well, it basically means that we’re going to be looking after children for a while now.’ I felt happy cos I thought it was gonna be like ‘Oh yeah! New friends that will get to come on holiday with us.’ (Callum). (Stoneman & Dallos, Citation2019, p. 174)

Some of the children in Reed (1996–1997) and Spears and Cross (Citation2003), were satisfied with their level of involvement and information received. However, in eight studies, children advocated the importance of biological children being included in the discussions and preparation for fostering, and of being more informed (Martin, Citation1993; Nordenfors, Citation2016; Ntshongwana & Tanga, Citation2018; Raineri et al., Citation2018; Reed, 1996–1997; Roche & Noble-Carr, Citation2017; Spears & Cross, Citation2003; Targowska et al., Citation2016). The children in these studies indicated that better preparation in advance would have been beneficial.

Overall, children reported being involved in discussions and decision-making related to fostering in only four studies. More widespread across the studies were experiences of lack of involvement, information and preparation related to fostering. This lack of inclusion, influence, and power contrasts with the degree of responsibility that was evidenced in the primary studies.

Adaptations within the Family System

This theme reflects the disruption and adaptation which studies reported children experienced in their families, due to fostering.

Disruption to familial balance

Across many studies it appeared that the arrival of a foster child brought a sense of threat to the biological children, and increased tension in the home. Six studies reported that children were aware of increased tension, strain, and disruption in the home, with increased arguments in the family resulting from fostering (Adams et al., Citation2018; Höjer, Citation2007; Ntshongwana & Tanga, Citation2018; Reed, Citation1994, 1996–1997; Spears & Cross, Citation2003; Targowska et al., Citation2016). Reed (Citation1994) reported that children resented the disputes which arose from fostering. Two studies reported that fostering caused less disruption for older children, who had more independence and led more separate lives (Reed, Citation1994, 1996–1997; Spears & Cross, Citation2003).

Several studies reflected how the presence of the foster children appeared to threaten the biological children’s role and position in the family (Martin, Citation1993; Ntshongwana & Tanga, Citation2018; Stoneman & Dallos, Citation2019; Sutton & Stack, Citation2013; Targowska et al., Citation2016; Twigg, Citation1994). Twigg (Citation1994, p. 308) reported how “all FPOC,” that is, foster parent’s own children, “found that foster children were a threat to their position in the family.” The age of the foster child seemed relevant to the threat they posed, with children sometimes reporting a preference for younger foster children as they were less threatening to their familial position and role (Martin, Citation1993; Sutton & Stack, Citation2013). Some children in Stoneman and Dallos (Citation2019) also reported that those closer in age were more threatening to their role.

The presence of foster children created a rivalry for parental resources. Twelve studies documented how this often meant reduced access to parental time, attention, and shared activities (Adams et al., Citation2018; Martin, Citation1993; Njøs & Seim, Citation2019; Ntshongwana & Tanga, Citation2018; Raineri et al., Citation2018; Reed, Citation1994, 1996–1997; Roche & Noble-Carr, Citation2017; Spears & Cross, Citation2003; Stoneman & Dallos, Citation2019; Sutton & Stack, Citation2013; Targowska et al., Citation2016; Twigg, Citation1994). Specific emotions prompted by this were documented in several studies, and included jealousy (Kaplan, Citation1988; Ntshongwana & Tanga, Citation2018; Raineri et al., Citation2018), irritation (Njøs & Seim, Citation2019; Spears & Cross, Citation2003; Sutton & Stack, Citation2013; Twigg, Citation1994) and feeling neglected (Reed, 1996–1997; Stoneman & Dallos, Citation2019).

The FPOC [foster parent’s own children] resented having to compete with the foster children for parental time and attention. ‘Would the foster children give me time with my parents? Would they give me my parents?’ The 15-year-old male FPOC who asked this question estimated that his parents spent 90% of their time with the foster children and 10% of their time with their own children. (Twigg, Citation1994, p. 307)

In addition, five studies reported that biological children contended with feeling that foster children received preferential treatment from their parents with regards to discipline and blame, heightening the sense of rivalry (Adams et al., Citation2018; Höjer, Citation2007; Ntshongwana & Tanga, Citation2018; Roche & Noble-Carr, Citation2017; Spears & Cross, Citation2003). Sharing the familial home was also reported to bring further rivalry and challenges, as the children adjusted to sharing space and possessions (Martin, Citation1993; Ntshongwana & Tanga, Citation2018; Raineri et al., Citation2018; Raineri et al., Citation2018; Reed, Citation1994, 1996–1997; Rees & Pithouse, Citation2019; Spears & Cross, Citation2003; Stoneman & Dallos, Citation2019; Targowska et al., Citation2016; Twigg, Citation1994).

Making space for new members

Across several studies, the process and impact of integrating foster children into the family was evident.

An initial sense of wariness of new members (Raineri et al., Citation2018; Rees & Pithouse, Citation2019; Spears & Cross, Citation2003) or awkwardness with foster children (Sutton & Stack, Citation2013) was reflected in some studies. Two studies reported how the children learned to make quick assessments of new additions (Martin, Citation1993; Rees & Pithouse, Citation2019), while another two studies documented how there could also be excitement and anticipation for new arrivals (Njøs & Seim, Citation2019; Sutton & Stack, Citation2013).

Integration of the children into the family was evidenced in several studies. Strategies to get to know the children were documented in four studies, such as playing with the children and talking to them (Rees & Pithouse, Citation2019; Roche & Noble-Carr, Citation2017; Spears & Cross, Citation2003; Sutton & Stack, Citation2013). The foster sibling’s presence brought benefits such as companionship, friendship, and enjoyment (Raineri et al., Citation2018; Reed, Citation1994, 1996–1997; Rees & Pithouse, Citation2019; Roche & Noble-Carr, Citation2017; Spears & Cross, Citation2003; Sutton & Stack, Citation2013; Targowska et al., Citation2016). Significant, close relationships often developed between the biological and foster children, (Raineri et al., Citation2018; Spears & Cross, Citation2003; Targowska et al., Citation2016), and five studies detailed how foster children were viewed and treated as part of the family (Njøs & Seim, Citation2019; Ntshongwana & Tanga, Citation2018; Reed, Citation1994, 1996–1997; Roche & Noble-Carr, Citation2017; Sutton & Stack, Citation2013).

Six studies documented that children perceived familial benefits through the adaptation to the new member such as feeling closer and more unified with family (Ntshongwana & Tanga, Citation2018; Stoneman & Dallos, Citation2019) and increased family activities and special occasions (Roche & Noble-Carr, Citation2017; Spears & Cross, Citation2003; Stoneman & Dallos, Citation2019; Sutton & Stack, Citation2013; Targowska et al., Citation2016). Many of these are captured in the excerpt from Sutton and Stack (Citation2013):

Participants gave credit to the presence of their new sibling for ‘solving’ problems they perceived out with their own control: ‘It’s better when there’s lots of people there cause it means that you’re not bored and you can do stuff, cause I’m shy and I don’t really make friends’ (P3). ‘I always wanted a wee brother or sister, cause I’m an only child and my mum and dad broke up when I was two, so there was no chance of that, so I really enjoyed the idea of having someone else’ (P2). All the participants also commented on how the addition of their foster sibling led to the opportunity for many more outings and holidays than they had previously had. (p. 601)

Grappling with placement endings

Seven studies captured that when foster children left the family it was often experienced as a loss (Njøs & Seim, Citation2019; Ntshongwana & Tanga, Citation2018; Rees & Pithouse, Citation2019; Spears & Cross, Citation2003; Stoneman & Dallos, Citation2019; Sutton & Stack, Citation2013; Targowska et al., Citation2016).

Foster siblings who moved out often left a void in the family. Nina (11) said ‘It was kind of strange here. There was no one at the dinner table, and no one that I had to lock the toilet door for. It was all a bit strange’. (Njøs & Seim, Citation2019, p. 168)

The ways in which children coped with this loss varied. Sutton and Stack (Citation2013) reported how supportive others, and a “rest” period (p. 605) between placements allowed the time for consolidation of personal and family identities, to explore and make sense of the placement end and accompanying feelings. Targowska et al. (Citation2016) reported how children adapted to the transitional nature of fostering over time, and relatedly invested less. Stoneman and Dallos (Citation2019) reported that when faced with the emotional impact of a child leaving, some children focussed upon the positive aspects of the child leaving, dismissing their own sadness. Stoneman and Dallos (Citation2019) also reported that relationships in the family changed when a foster child left, the nature of such change depending on the experience of the placement, with some children feeling more distant within family relationships after the exit of a foster child.

Some studies reflected concern children held for the wellbeing of their foster sibling leaving (Kaplan, Citation1988; Njøs & Seim, Citation2019; Roche & Noble-Carr, Citation2017; Targowska et al., Citation2016). Three studies captured the children’s long-term commitment to foster children, wanting to maintain contact or still considering them a part of their family (Roche & Noble-Carr, Citation2017; Reed, 1996–1997; Stoneman & Dallos, Citation2019). “‘We’ve always remembered all of the people that we’ve fostered; they’re still a part [of the family]’ (Jeremia). ‘They stay in my heart’ [taps heart with hand] (Skye)” (Stoneman & Dallos, Citation2019; p. 180).

Although less often, endings sometimes prompted more ambivalent feelings. Children sometimes felt glad and relieved when placements ended, particularly if they had been difficult, however, this often was accompanied by guilt, regret, or sadness (Raineri et al., Citation2018; Roche & Noble-Carr, Citation2017; Spears & Cross, Citation2003; Stoneman & Dallos, Citation2019; Sutton & Stack, Citation2013; Targowska et al., Citation2016).

Buffering against the Challenges of Fostering

This theme captures what the primary studies reported as helpful to the birth children in coping with the challenges brought by fostering.

Internal coping mechanisms

Eleven studies detailed the ways in which birth children appeared to cope with the challenges of fostering at an individual level.

Some studies reported how children tended to minimize their own needs and reframe the foster child as having greater needs, in a bid to help them to cope with the threat posed by sharing parental resources (Adams et al., Citation2018; Martin, Citation1993; Reed, Citation1994; Stoneman & Dallos, Citation2019). “‘For that moment, and for that month, they needed the attention more than I did’ (Casey)” (Adams et al., Citation2018, p. 144). The children in the primary studies often demonstrated good perspective-taking abilities, incorporating the views of others in the family into their thinking to help them cope with challenges (Kaplan, Citation1988; Sutton & Stack, Citation2013).

Eight studies reported how the biological children’s development of empathy and understanding of foster children’s life experiences helped them to make sense of and cope with their challenging behavior (Höjer, Citation2007; Kaplan, Citation1988; Raineri et al., Citation2018; Roche & Noble-Carr, Citation2017; Spears & Cross, Citation2003; Stoneman & Dallos, Citation2019; Sutton & Stack, Citation2013; Targowska et al., Citation2016).

The birth children said that knowing the foster child’s story and putting themselves in his/her shoes was useful to justify the foster child’s behaviours, to refrain from hurting him/her, to avoid having naïve expectations, and sometimes even to be able to give support or advice. ‘Track in your mind the journey of his childhood…think that the things we take for granted, he has never had…and try to think how you would react.’ (Gloria, 15). (Raineri et al., Citation2018, p. 629)

Two studies reported how younger children in their samples tended to more directly express negative feelings about foster children compared to older children in the sample (Kaplan, Citation1988; Martin, Citation1993).

In her study, Kaplan (Citation1988) reported the identification with mothers in the caretaking role served as a defence for children. Similarly, Stoneman and Dallos (Citation2019), found that the caregiving role increased the children’s sense of inclusion by parents, helping to mitigate against feelings of displacement and rivalry. Indeed, engaging in a caretaking role appeared to bring a sense of value, purpose, pride and accomplishment to some of children in five of the primary studies, appearing to help sustain children in their fostering experiences, providing as described in Raineri et al. (Citation2018, p. 631): “‘an impetus to go on’ Gloria, 15.” (Adams et al., Citation2018; Raineri et al., Citation2018; Stoneman & Dallos, Citation2019; Sutton & Stack, Citation2013; Targowska et al., Citation2016).

The protective power of attuned parenting

In eight studies it was apparent that parents played a key role in helping their biological children cope with the demands of living in a fostering family (Adams et al., Citation2018; Martin, Citation1993; Ntshongwana & Tanga, Citation2018; Raineri et al., Citation2018; Reed, Citation1994; Spears & Cross, Citation2003; Stoneman & Dallos, Citation2019; Sutton & Stack, Citation2013).

Feeling valued and cared for in their relationship with their parents was important in helping the biological children cope with the demands brought by fostering. Such feelings often arose through experiences of having protected time alone with parents or having confidence that this was available to them (Adams et al., Citation2018; Raineri et al., Citation2018; Stoneman & Dallos, Citation2019; Sutton & Stack, Citation2013). Being able to have open dialogue with parents about the worries and difficulties related to fostering also appeared to buffer against such difficulties, sometimes helping the child feel part of the fostering team (Adams et al., Citation2018; Martin, Citation1993; Raineri et al., Citation2018; Reed, Citation1994; Spears & Cross, Citation2003; Stoneman & Dallos, Citation2019; Sutton & Stack, Citation2013).

We spoke to mum and dad and told them how we feel, they explained and told us that they love us and just because they spend time with the looked-after child doesn’t mean that we’re not loved. Just being told that worked (P5). (Sutton & Stack, Citation2013, p. 602)

Three studies referenced how a secure attachment and strong bond with parents provided a context integral to supporting the children to share parental resources with foster children and support adaptive coping strategies (Adams et al., Citation2018; Ntshongwana & Tanga, Citation2018; Sutton & Stack, Citation2013). However, all the helpful parental support captured in this theme is likely to occur in such a context, given the attunement to the children’s needs evidenced in it.

Shaped by the Realities of Fostering

This theme reflects the impact that the human adversities inherent to fostering had on the biological children living in fostering families, as evidenced in the primary studies.

Loss of innocence

Seven studies captured how the experience of living in a fostering family often exposed children to knowledge about the adversities faced by foster children and their biological families, gaining awareness of family breakdowns, abuse, neglect, and violence (Höjer, Citation2007; Kaplan, Citation1988; Martin, Citation1993; Raineri et al., Citation2018; Spears & Cross, Citation2003; Stoneman & Dallos, Citation2019; Targowska et al., Citation2016).

In some instances children felt they had been exposed to issues they did not want to consider, for example, being told about homosexuality and sexual abuse. One said, ‘I don’t want to think about it.’ They also found it difficult to deal with people who ‘do not wash, get drunk and take drugs.’ Some of them had seen someone who was drunk/overdosed and had been very frightened. (Spears & Cross, Citation2003, p. 43)

For some children, it was difficult to fully understand the human hardship they were faced with (Höjer, Citation2007; Kaplan, Citation1988; Targowska et al., Citation2016), and some conceptualized their own reasons for the child’s entry to foster care (Kaplan, Citation1988). Some studies reported that foster children had made disclosures about abuse to the biological children, or in their presence (Martin, Citation1993; Stoneman & Dallos, Citation2019; Targowska et al., Citation2016). Knowledge of adverse life experiences appeared to prompt worry and concern for children, some of whom wondered if they too may be abandoned by their parents (Kaplan, Citation1988; Raineri et al., Citation2018).

Children were also exposed to challenging behaviors that foster children displayed, such as aggression, stealing, and destruction of possessions, sometimes struggling to make sense of these (Höjer, Citation2007; Martin, Citation1993; Raineri et al., Citation2018; Reed, Citation1994; Roche & Noble-Carr, Citation2017; Spears & Cross, Citation2003; Sutton & Stack, Citation2013; Targowska et al., Citation2016). “‘They punch, they kick, they nip, they scratch, they bite’; ‘they kicked the dog, pulled his tail, pulled his ears, poured tomato sauce in his ears and he had like an ear infection after one of them did that’” (Targowska et al., Citation2016, p. 33). Foster children’s challenging behaviors brought feelings of anger (Spears & Cross, Citation2003) sadness (Höjer, Citation2007), concern for their parents (Spears & Cross, Citation2003; Sutton & Stack, Citation2013) and helplessness (Targowska et al., Citation2016). However, exposure to knowledge of the children’s life experiences appeared to help them to resolve such feelings and better understand the children and their behaviors (Höjer, Citation2007; Raineri et al., Citation2018; Stoneman & Dallos, Citation2019; Sutton & Stack, Citation2013).

Personal growth and development

It was evident in 11 studies that exposure to the life adversities inherent to fostering brought growth and personal development to biological children.

Six studies documented how exposure to knowledge of the adversities faced by people in life broadened and enhanced the biological children’s worldviews and perspectives (Martin, Citation1993; Ntshongwana & Tanga, Citation2018; Raineri et al., Citation2018; Roche & Noble-Carr, Citation2017; Stoneman & Dallos, Citation2019; Sutton & Stack, Citation2013). Many studies reported that through the fostering experience, children had developed a better understanding of others and others’ behavior, and enhanced capacity for empathy and compassion (Nordenfors, Citation2016; Rees & Pithouse, Citation2019; Spears & Cross, Citation2003; Stoneman & Dallos, Citation2019; Targowska et al., Citation2016). “One gets to know a lot about how people are, and what they have experienced. Why they behave in certain ways. Compared to my friends, I have a totally different perspective. (Questionnaire, woman, 18)” (Nordenfors, Citation2016, p. 866).

Some reported that fostering experiences facilitated the development of kindness, sensitivity, altruism (Ntshongwana & Tanga, Citation2018; Raineri et al., Citation2018; Rees & Pithouse, Citation2019; Spears & Cross, Citation2003). Considering the increased awareness of life’s adversities, some reported an increased gratefulness for their own fortunate circumstances, and a re-calibration of what problems consist of (Spears & Cross, Citation2003; Sutton & Stack, Citation2013).

Fostering provides insights into the adversity many people face and the children and young people who foster often mentioned this, especially in relation to understanding a foster child’ s behaviour. They frequently gain some understanding of the difficulties foster children have been through and therefore learned to appreciate their own circumstances: ‘[It] made me value what I have and not take things for granted… how lucky I am to have good parents.’ (Spears & Cross, Citation2003, p. 42)

Collaborating with Others Beyond the Family

This final theme documents how the children in the primary studies negotiated the fostering tasks with others, outside of their families.

The importance of recognition and inclusion by the system

Six studies reported on children’s experiences of recognition and inclusion by social work systems and agencies implementing the foster placements (Martin, Citation1993; Ntshongwana & Tanga, Citation2018; Raineri et al., Citation2018; Reed, 1996–1997; Roche & Noble-Carr, Citation2017; Spears & Cross, Citation2003). Three of these captured a lack of inclusion of birth children by professionals, reporting how the children’s points of view and feelings about fostering were not sought or considered by social workers (Ntshongwana & Tanga, Citation2018; Raineri et al., Citation2018; Reed, 1996–1997) and some reported that they were often not included in preparation programme by social workers (Ntshongwana & Tanga, Citation2018; Spears & Cross, Citation2003). “Carla: No, we never, never talked to any social worker. We have not even been taken into account at all” (Raineri et al., Citation2018, p. 630).

Five studies (Martin, Citation1993; Raineri et al., Citation2018; Reed, 1996–1997; Roche & Noble-Carr, Citation2017; Spears & Cross, Citation2003) captured a desire by some of the children to be recognized in their role and included in the preparation and support provided to foster families.

They argued that they should be involved in the plan to take a particular child, and that they needed to be given as much information as possible about the children. They realized that this might challenge the commitment of social workers to a particular view of confidentiality, but felt that if they themselves had the information they could better understand and be tolerant of the children joining their family. (Martin, Citation1993, p. 18)

Reed’s (1996–1997) study captured more ambivalent experiences, reporting that some participants who appeared to accept being part of a foster family were less concerned about contact with social workers and didn’t argue for increased social work support. Reed (1996–1997) also reported that some of those who were happy wanted greater involvement so that they could contribute further to the care of the foster child.

The impact and influence of peers

With regards to the influence and impact of the birth children’s peers, two studies reported that biological children were able to integrate foster siblings with their friendship groups (Raineri et al., Citation2018; Reed, Citation1994, 1996–1997). For these children, integration seemed possible and peer friendships were maintained. “Some of the older teenagers explained how they involved the young person living with them in their social life outside the home, for instance going out for a meal with friends” (Reed, 1996–1997, p. 37).

However, five studies reported how for some children, integrating the fostering task with peers was more difficult. Targowska et al. (Citation2016) reported that children experienced weakened peer relationships because of distress and embarrassment over foster children’s behavior. Spears and Cross (Citation2003) also reported weakened peer relationships due to the fostering task. Martin (Citation1993) reported how some children felt “under pressure being different” (p. 19) from school friends due to being in a fostering family. Raineri et al. (Citation2018) and Reed (Citation1994) reported that children found their peers’ lack of understanding of fostering and of foster children challenging.

Two studies reported that children’s experiences of peer support from the birth children of other foster families were beneficial and appreciated, as these peers were better able to understand (Raineri et al., Citation2018; Spears & Cross, Citation2003). Participants in Roche and Noble-Carr (Citation2017) study expressed interest in such a network, while those in Spears and Cross (Citation2003) called for such networks to be strengthened.

A form of peer support between birth children from different families is greatly appreciated because they ‘understand more.’ ‘Those parents have three biological children who are more or less our own age, and we talked to them when we went three or four times for dinner or saw them on the train. We talked to them; they are used to it. It was nice…It had an effect because when I told my grandparents, my uncles, my cousins…they did not know anything about these stories of fostering!’ (Anna, 14). (Raineri et al., Citation2018, p. 629)

Negotiating interactions with the birth families

Three studies reported on biological children’s experiences with foster children’s birth families, with the complexity of these relationships seemingly apparent to the children. Some children experienced uncertainty in how to regard the birth families (Höjer, Citation2007). Others appeared mindful as to how to respond to their behavior on access visits, recognizing a need to be “tactful and understanding” (Martin, Citation1993, p. 19). Raineri et al. (Citation2018) reported that children advocated for the need of good relations between the foster and birth family and for foster children to be told the truth about their biological families. The children in this study also appeared attuned to how contact visits may impact the foster children: “when he comes home from his mum, you have to be careful and see how he is, if he is happy or if he is sad …. (Alberto, 15)” (Raineri et al., Citation2018, p. 630)

Discussion

Summary of findings

The current review systematically identified and synthesized the qualitative evidence of the experiences of the birth children of foster carers, of living in fostering families, giving insight into the lived experiences of these individuals. The findings extracted from the fifteen identified studies were thematically synthesized, and five analytical themes with associated subthemes were found: “Responsibility and Power in the Fostering Task,” “Adaptations of the Family System,” “Buffering against the Challenges of Fostering,” “Shaped by the Realities of Fostering,” and “Collaborating with Others beyond the Family.”

The first theme captures the responsibility that the birth children appeared to gain through fostering. Across many studies, the birth children in foster families often gained extra caring duties, toward the foster child and their own parents, by virtue of the fostering assignment. These caring roles and duties often brought positive feelings and gains to the children. However, negative feelings were also documented. This was particularly the case if demands were perceived as too restrictive or onerous, and the responsibility held often led to the children worrying about the welfare of the foster child and their own parents. The responsibility contrasted with the degree of power children appeared to have in the task. Several studies reported that children were not involved in the family’s decision to foster or the preparation for fostering, and in many studies children called for greater inclusion in these. Thus, it appeared that while children often gained responsibilities similar to those held by parents, this occurred in the context of childhood control. The review by Thompson and McPherson (Citation2011) captured elements of this, including concern for the foster children, lack of preparation and information for the birth children, pressure to be more responsible, understanding, and caring, and expectations to help take care of the foster children. The current review sheds light on the children’s experiences of involvement with family decision-making related to fostering, which was not captured in the review by Thompson and McPherson (Citation2011).

Research has shown that when helping responsibilities conferred to a child are beyond their developmental abilities and are unreciprocated or unacknowledged, the child may begin to view themselves as inadequate and pathological outcomes may occur (Hooper et al., Citation2014). Conversely, the roles and responsibilities associated with caretaking responsibilities can bring potential benefits to children, including the development of relational, leadership and organizational skills (East, Citation2010). Thus, the positive and negative consequences of the children’s increased responsibilities captured in this review appear consistent with those in the wider literature, with such contributions to the family linked to both positive and negative psychological outcomes (Armstrong-Carter et al., Citation2019).

The second analytic theme evidences the processes of adaptation by the family to integrate the foster child and subsequently adapt to their loss. It evidences how the foster child’s presence and the individual relationships of the foster child influence other members of the family, with birth children reporting feeling different degrees of familial closeness during and sometimes after the child’s placement. Many benefits of the new member are also evidenced here, with the birth children often developing significant relationships and associated benefits. These familial changes are consistent with a family systems conceptualization of the foster family’s task (Eastman, Citation1979). The birth children’s experiences also bear resemblance to the literature regarding the arrival of birth siblings (Mitchell, Citation2013), with many of the children developing good relationships with foster children whilst also feeling somewhat displaced by them. The current review evidenced how perceived preferential treatment of the foster child by parents was particularly challenging for children, which is also a documented challenge for birth siblings and associated with more conflicted, hostile sibling relationships (Dunn, Citation2002). This may help explain the conflict reported by foster carers between their children and foster children (Rhodes et al., Citation2001).

The third theme “Buffering against the Challenges of Fostering” documents how the birth children coped with the challenges of fostering. At an individual level some studies reported that children minimized their own needs and re-framed the foster child as having greater needs. Whilst in the short term, minimizing their emotions may help the children cope with difficult feelings, when used continually, such an avoidant coping mechanism is potentially maladaptive and may prevent the children from engaging in more functional strategies of catharsis and emotional processing (Carr, Citation2016). The caretaking role and duties assumed by many of the children were identified as protective against the difficulties faced in fostering. From a family systems lens, it is possible that the birth child’s alignment with the caregiver role of the parental subsystem was protective in that it strengthened their role and position, reducing threats. Furthermore, the caretaking role was reported to bring positive feelings to the birth children such as pride, value, and achievement. Engagement in voluntary behaviors intended to benefit another are inherently rewarding, with positive affect and emotions shown to be both caused by and resulting from such behaviors (Aknin et al., Citation2018). Thus, it is likely the emotional gains of these experiences cause and promote continued engagement in such helping behaviors, despite the documented challenges.

The protective power of attuned parenting was evident in over half of the studies. Feeling valued and cared for by their parents, having special protected time alone with them, and feeling that they were available to discuss problems and difficulties with them, all helped the children manage the challenges they faced through fostering. While three studies specifically referenced the secure attachment which contextualized such supportive behaviors, the clear attunement of parents to the children’s needs in other studies likely indicates a strong parent-child relationship and secure attachment context. Research has shown that positive parent-child relations are associated with pro-social and positive sibling relationships (Brody, Citation1998). Thus, positive parent-child relations are likely not only protective toward the birth child’s mental wellbeing but also likely to positively to influence the relationships with foster siblings.

The fourth theme captures the impact of exposure to the difficulties inherent to the fostering task on the children’s development. The children appeared to experience a loss of innocence through fostering in that they were exposed to knowledge of traumatic events and difficulties faced by foster children and their birth families, as well as the challenging behaviors often expressed by foster children. Vicarious exposure to the traumatic events documented in this review has the potential to cause secondary traumatic stress, that is, stress responses including symptoms similar to those seen in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Bridger et al., Citation2020). Secondary traumatic stress has previously been evidenced in foster carers (Bridger et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, research has shown that exposure to violence and aggression in the home is detrimental to children’s and adolescents’ functioning and wellbeing (Wolfe et al., Citation2003), as too are experiences of sibling violence (Perkins & O’Connor, 2015). Thus, exposure to these behaviors has the potential to be detrimental to the children’s wellbeing. Similar to post-traumatic growth, the occurrence of vicarious post-traumatic growth has been identified in the literature and has been shown to include changes in values and priorities, increased personal strength, spiritual growth and improved interpersonal relationships (Manning-Jones et al., Citation2015). Taken together, it is possible that the personal development identified in the current review could be explained by the concept of vicarious post-traumatic growth.

The fifth theme reflected how relevant others beyond the family influenced and impacted upon children’s experiences of fostering. Overall, interactions with, influences of, and impact upon others beyond the family featured less in the children’s accounts. Nevertheless, a sense of lack of inclusion by the social care systems implementing fostering was evident, with a call by many children to be recognized in their role and included in the preparation and support provided to families. This finding relates to the earlier finding regarding power and responsibility in fostering, with the social care systems and agencies recognized as powerful others which could assist with training and information. Peers were another group which children discussed in relation to their fostering experiences. The impact of being in a fostering family varied, with some children able to integrate the foster children with peers, and others finding it alienated them from peers. Factors related to the foster child appeared relevant, with regards to their behavior, and peer factors, in their ability to understand the task of fostering and the foster child’s behavior.

Some children had experience of receiving peer support from other biological children in fostering families, and where this had happened it was helpful. Indeed, peer support programs have been used with children and adolescents facing a variety of difficulties (D’Arcy et al., Citation2005; Foster et al., Citation2014), and have been shown to be beneficial and enhance coping, relationships, and self-esteem (Foster et al., Citation2014; Goodyear et al., Citation2009). Interactions with foster siblings’ birth families were referenced by three studies, although there were not a lot of data regarding these interactions. From the data that were synthesized, the complexity of the status of these others is evident. This final theme further adds to what is known about the impact of fostering on birth children, as the experiences of these others in relation to the fostering task were not captured in the previous review (Thompson & McPherson, Citation2011). This theme is presented tentatively, given the lower confidence in the findings contributing to this theme, as evidenced in .

Key contributions of the review to the literature

Overall, the review findings add to and are supported by existing literature. This review furthers this research area, through the systematic and thorough synthesis of existing qualitative evidence. The current review identified and synthesized data from 15 qualitative studies capturing the experiences of the birth children and adolescents of foster carers, of living in fostering families. By focussing on this particular age group, the current review has elucidated a synthesized account of the experiences specific to this population, which did not exist previously in the literature. In doing so, it addressed a need for a comprehensive systematic synthesis of this qualitative evidence and provides implications for how this may support future research, policy, and practice.

The review’s findings emphasize the active role these children take in the task of fostering. The disruption, adjustments, gains, and losses they experience through fostering are also evident. The ways in which these individuals cope with these challenges are identified, as too are the influences of significant others in their lives. The findings of the review are contextualized in the wider literature, to further the understanding of these experiences.

Strengths and limitations of included studies

As described earlier, the quality appraisal identified methodological limitations in some of the studies. Particularly widespread was the lack of reporting of researcher-participant relationships. Several studies also lacked detailed on the data analysis conducted. However, despite the methodological limitations, the included studies largely provided rich data pertaining to the birth children’s experiences. Furthermore, the majority of the current review findings were rated with moderate or high confidence. Confidence in the three findings “The Importance of Recognition and Inclusion by the System,” “The Impact and Influence of Peers,” and “Negotiating Interactions with the Birth Families” had reduced confidence due to concerns regarding adequacy of data and methodological rigor of contributing studies. Thus, caution is warranted in interpretation of these three findings. The included studies had a large geographical spread and appeared to incorporate various fostering experiences, with good coherence across studies with many reporting similar themes and findings. These characteristics add to the strength of the literature base, enhancing the generalizability of the findings.

Strengths and limitations of this review

Strengths of the current review include the transparent and thorough approach to identification, quality appraisal, and synthesis of qualitative evidence relating to the experiences of birth children of foster carers. Confidence in the identified findings was also rigorously and transparently assessed using the GRADE-CERQual approach. The process for identification of studies was comprehensive, incorporating a forward and backward search strategy, given the known difficulties with the indexing of qualitative research. The search strategy appeared robust in that all but one of the included studies were identified through database searches. The use of thematic synthesis methodology facilitated the review to go beyond simply summarizing the existing data and provided a synthesis. The use of NVivo software facilitated a transparent audit trail. Regular discussion and supervision facilitated reflection on decisions and further enhanced the rigor of the review. A second independent reviewer completed 20% of the title and abstract screening, and 100% of the full text screening. Furthermore, the quality appraisal and data extraction processes were completed by two independent reviewers, further minimizing risk of bias and enhancing thoroughness. Notably, few discrepancies occurred throughout the screening, appraisal, and extraction processes.

The decision to extract relevant, clearly extractable findings from studies which included other non-relevant participants means the number of individuals contributing to this review cannot be calculated. However, this decision enhanced the number of contributing participants overall and permitted a more comprehensive synthesis of data pertaining to the experiences of birth children and adolescents.

Implications for research and practice

As has been highlighted, the lack of detailed information in some of the study reports may be due to space limitations in publications and may represent the published report rather than the quality of the research. Thus, the current review highlights the need for comprehensive and accurate reporting of qualitative research. Future researchers could use a qualitative quality assessment tool, such as the CASP checklist, to help guide comprehensive reporting of qualitative research. The findings of the current review also indicate areas which it may be beneficial for future research to further explore. Future research could add to and strengthen findings, particularly by exploring those where it has been judged that adequacy and methodological rigor appear to be unclear or lacking.

The current review indicates several implications for policy and practice. Firstly, it appears that policies, agencies, and systems governing the implementation of foster care should make efforts to include the birth children of foster carers into this task. This implication is made tentatively, given the lower confidence in the review finding relating to systems and agencies. As evidenced, greater acknowledgement of their role, as well as increased information and preparation were often sought. Furthermore, as highlighted in the above discussion, meeting this need may help mitigate against potential adverse effects of the responsibilities gained through fostering. The use of forums within agencies and care systems, for these children to have their voices heard and incorporated into their policies and practices may also be beneficial. The current review also indicates that strengthening the peer support networks available to birth children may be supportive to them. Again, this is made tentatively given the lower confidence in this review finding. However, as highlighted in the above discussion, such peer support groups have been evidenced as beneficial in various areas of research.

Birth children’s parents also appear to have a role in helping the children prepare for and feel included in the fostering task, not solely the systems and agencies. Furthermore, the protective power of parents and the documented impact of the foster child on the parent-child relationship evident in the current findings may be particularly important to incorporate into training with foster parents. Awareness of how fostering may impact their birth children and how they can mitigate negative effects would likely enhance their supportive capacity. Additionally, given the documented way in which the experiences of family members influence each other, interventions aimed at supporting and enhancing family relationships and functioning may be warranted if members are struggling in the fostering task. The consideration and availability of these could be incorporated into existing social work systems’ practice.

Conclusion

The current review identified and synthesized data from 15 qualitative studies capturing the experiences of the birth children and adolescents of foster carers, of living in fostering families. The current findings emphasize the active role these children take in the task of fostering, the impact of fostering on their lives, and the ways in which they cope with challenges presented by the task. The review findings suggest that greater inclusion and support of these children, by fostering agencies and systems as well as by their parents, may be protective of their wellbeing and enhance the role they take in the fostering task. Indeed, as captured by Martin (Citation1993, p. 17): “It is not just the parents who foster, it is the whole family.”

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

References

- Adams, E., Hassett, A. R., & Lumsden, V. (2018). ‘They needed the attention more than I did’: How do the birth children of foster carers experience the relationship with their parents? Adoption & Fostering, 42(2), 135–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308575918773683

- Ainsworth, F., & Maluccio, A. (2003). Towards new models of professional foster care. Adoption & Fostering, 27(4), 46–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/030857590302700407

- Aknin, L. B., Van de Vondervoort, J. W., & Hamlin, J. K. (2018). Positive feelings reward and promote prosocial behavior. Current Opinion in Psychology, 20, 55–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.08.017

- Armstrong-Carter, E., Olson, E., & Telzer, E. (2019). A unifying approach for investigating and understanding youth’s help and care for the family. Child Development Perspectives, 13(3), 186–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12336

- Blythe, S. L., Wilkes, L., & Halcomb, E. J. (2014). The foster carer’s experience: An integrative review. Collegian (Royal College of Nursing, Australia), 21(1), 21–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2012.12.001

- Boland, A., Cherry, G., & Dickson, R. (2017). Doing a systematic review: A student’s guide. SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Booth, A., Noyes, J., Flemming, K., Gerhardus, A., Wahlster, P., van der Wilt, G. J., Mozygemba, K., Refolo, P., Sacchini, D., Tummers, M., & Rehfuess, E. (2018). Structured methodology review identified seven (RETREAT) criteria for selecting qualitative evidence synthesis approaches. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 99, 41–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.03.003

- Bridger, K. M., Binder, J. F., & Kellezi, B. (2020). Secondary traumatic stress in foster carers: Risk factors and implications for intervention. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(2), 482–492. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10826-019-01668-2

- Brody, G. H. (1998). Sibling relationship quality: Its causes and consequences. Annual Review of Psychology, 49(1), 1–24. 1146/annurevpsych.49.1.1 https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.1

- Carr, A. (2016). The handbook of child and adolescent clinical psychology: A contextual approach. Routledge.

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2018). CASP (Qualitative Studies Checklist). https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

- Cooke, A., Smith, D., & Booth, A. (2012). Beyond PICO: The SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qualitative Health Research, 22(10), 1435–1443. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732312452938

- Cooley, M. E., Farineau, H. M., & Mullis, A. K. (2015). Child behaviors as a moderator: Examining the relationship between foster parent supports, satisfaction, and intent to continue fostering. Child Abuse & Neglect, 45, 46–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.05.007

- D’Arcy, F., Flynn, J., McCarthy, Y., O’Connor, C., & Tierney, E. (2005). Sibshops: An evaluation of an interagency model. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities: JOID, 9(1), 43–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629505049729

- Dunn, J. (2002). Sibling relationships. In P. K. Smith & C. H. Hart (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of childhood social development (pp. 223–237). Blackwell Publishers.

- East, P. L. (2010). Children’s provision of family caregiving: Benefit or burden? Child Development Perspectives, 4(1), 55–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.17508606.200900118.x

- Eastman, K. (1979). The foster family in a systems theory perspective. Child Welfare, 58(9), 564–570. https://www.jstor.org/stable/45393606?seq=1

- Farmer, E., Lipscombe, J., & Moyers, S. (2005). Foster carer strain and its impact on parenting and placement outcomes for adolescents. British Journal of Social Work, 35(2), 237–253. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bch181

- Foster, K., Lewis, P., & McCloughen, A. (2014). Experiences of peer support for children and adolescents whose parents and siblings have mental illness. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 27(2), 61–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcap.12072

- Goodyear, M., Cuff, R., Maybery, D., & Reupert, A. (2009). CHAMPS: A peer support program for children of parents with a mental illness. Australian e-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health, 8(3), 296–304. https://doi.org/10.5172/jamh.8.3.296

- Gouveia, L., Magalhães, E., & Pinto, V. S. (2021). Foster families: A systematic review of intention and retention factors. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 30(11), 2766–2781. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10826-021-02051-w

- Hayes, H. (1991). A re-introduction to family therapy clarification of three schools. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 12(1), 27–43. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/j.1467-8438.1991.tb00837.x

- Höjer, I. (2007). Sons and daughters of foster carers and the impact of fostering on their everyday life. Child & Family Social Work, 12(1), 73–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2006.00447.x

- Hooper, L. M., L’Abate, L., Sweeney, L. G., Ganesini, G., & Jankowsk, P. J. (2014). Models of psychopathology: Generational processes and relational roles. Springer.

- Horsley, T., Dingwall, O., & Sampson, M. (2011). Checking reference lists to find additional studies for systematic reviews. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2011(8), MR000026. 14651858pub2

- Houghton, C., Murphy, K., Meehan, B., Thomas, J., Brooker, D., & Casey, D. (2017). From screening to synthesis: Using NVivo to enhance transparency in qualitative evidence synthesis. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26(5–6), 873–881. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn13443