ABSTRACT

Evidence of the association between childhood maltreatment (CM) and intimate partner violence (IPV) in adulthood often relies on retrospective data. This study examined the association of both retrospectively and prospectively reported CM and IPV at 30-year follow-up in 2401 participants from the same birth cohort in Queensland, Australia. The cohort was linked to CM notifications to statutory agencies made by the age of 16. Data on IPV victimization and self-reported CM came from the revised Composite Abuse Scale and Child Trauma Questionnaire, respectively. Rates of self- and agency-reported maltreatment were 589 (24.5%) and 137 (5.7%), respectively. After adjustment, self-reported maltreatment of all forms showed significant associations with all types of IPV. In the case of agency-reported CM, this was limited to significant associations between substantiated neglect or sexual abuse and the most serious IPV events, as well as overall notifications and physical IPV. Associations with agency-reported CM were strongest for females.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) victimization includes any physical, psychological, or sexual harm by any existing or previous intimate partner while child maltreatment (CM) is any violence against a child by a caregiver (Li et al., Citation2019). Both are major, interlinked public health concerns. For instance, past experience of CM including neglect, sexual, physical, and emotional abuse, is often associated with victims experiencing one or more forms of IPV later in life (Messman-Moore & Long, Citation2000; Widom et al., Citation2008), such as sexual, physical, and psychological violence (Benedini et al., Citation2016; Messman-Moore & Long, Citation2000, Citation2003; Noll et al., Citation2003; Trickett et al., Citation2011). More specifically, child sexual abuse doubles the risk of lifetime IPV victimization, while combined physical and sexual CM increases the likelihood of both lifetime physical and sexual IPV by a factor of seven (Barrios et al., Citation2015). In terms of subtypes, all forms of CM types were equally associated with IPV victimization in the largest meta-analysis to date (k = 46 studies; Li et al., Citation2019).

There may be a number of possible reasons for this association. One hypothesis is that victims of CM may have difficulty developing the social skills necessary for handling emotions and forming lasting and healthy relationships following CM (Wyatt et al., Citation2000). Mental health challenges, such as the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) resulting from CM may also increase the likelihood of experiencing or perpetrating IPV (Abajobir et al., Citation2017). Research conducted in high school and child protection settings has demonstrated that PTSD may cause individuals to withdraw from regular social interactions, leading to increased hypervigilance and a greater likelihood of committing acts of IPV (Wekerle et al., Citation2001). Other potential contributing factors include early economic disadvantage and aggression in adolescence (Abajobir et al., Citation2017; Costa et al., Citation2015).

Gender may also play a role, although this is the subject of debate. There exist two competing theories in the current literature, albeit restricted to binary differences (i.e., male versus female). One theory suggests there are differences between genders with males more likely to be perpetrators, and female victims, of IPV as a result of a general imbalance of power between genders (Archer, Citation2000; Stith et al., Citation2000). By contrast, family violence theory maintains that there are gender similarities in the association between CM and IPV victimization, such that gender does not play a moderating role in the association between the two (Hamel, Citation2020; Li et al., Citation2019).

There are some gaps in the literature regarding the relationship between CM and IPV victimization. One is a reliance on largely cross-sectional designs and/or studies of self-reported CM with possible reporting and recall bias (Stevens et al., Citation2005; Widom et al., Citation2004). In addition, most work focuses on sexual and physical abuse rather than neglect or emotional abuse and does not differentiate between different types of IPV measured using validated instruments (Davis & Petretic-Jackson, Citation2000; Gómez, Citation2010; Herrenkohl et al., Citation2004). For instance, in the largest meta-analysis to date (k = 46 studies), there was little gender difference in IPV victimization among the four types of CM (physical, emotional, sexual abuse and neglect; Li et al., Citation2019). However, there were considerable differences in the amount of information by CM type. For example, there were 56 significant associations for overall CM and IPV victimization, 27 for physical abuse, and 22 for sexual abuse. By contrast, there were only 16 significant associations for emotional abuse and four for neglect (Li et al., Citation2019).

Longitudinal studies of IPV victimization using prospectively recorded measures of CM are less common. In a cohort study from the United States, children who experienced CM prior to the age of 11 and whose cases were Court-substantiated were interviewed approximately 30 years later (Widom et al., Citation2008, Citation2014). In comparison with controls who were matched on age, race, and family socio-economic status, individuals in which CM was substantiated showed a greater risk of both IPV victimization and victimization in general in adulthood (Widom et al., Citation2008, Citation2014). The latter included witnessing someone else being assaulted or being burgled or mugged (Widom et al., Citation2008). However, this work did not consider emotional abuse. Three further studies that were restricted to cases of substantiated physical abuse had mixed findings (Costa et al., Citation2015). In two of these studies, physical abuse in either childhood or adolescence was associated with subsequent physical IPV victimization (Linder & Collins, Citation2005; Sunday et al., Citation2011). However, in a third such study, physical abuse and IPV were found to be unrelated (Ireland & Smith, Citation2009).

In a final birth cohort study, participants who had been the subject of a substantiated report to statutory agencies of neglect, sexual, physical, or emotional abuse were compared to the remainder of the sample (Abajobir et al., Citation2017). All forms of CM were associated with approximately twice the odds of experiencing physical IPV while experiencing harassment was 63% higher in those who had been emotionally abused. Severe combined abuse (being raped or threatened with a weapon) was approximately four times more likely in children who experienced emotional abuse or neglect than those who had not. However, this study was limited to 21-year-olds. This points to the limited available information on IPV in mid- and older adulthood (Costa et al., Citation2015).

A final gap in the literature is that there has been no study that compared the outcomes of agency and self-reported CM maltreatment in the same sample. This is concerning as there may be limited overlap between the two groups (J. M. Najman et al., Citation2020). For example, agency CM may not reflect the actual occurrence of maltreatment, as some research suggests that as many as one-third of adults with a history of substantiated CM report having no memory of the abuse (Widom et al., Citation1999; Williams, Citation1994). In addition, agency and self-reported CM may have different associations with other psychological outcomes including anxiety, depression, and increased risk of substance use following self-reported CM.

Current study

In light of previous findings and gaps in the literature, a specific aim of this study was to investigate any differences in the associations between self- or agency-reported CM types and subsequent IPV victimization subcategories including the influence of sex through subgroup and sensitivity analyzes. A birth cohort was used to compare the effect at 30-year follow-up of both notifications to statutory agencies and self-reported CM as measured by a validated tool. In this study design, participants are followed longitudinally across their life span from birth to measure associations between early exposures and subsequent outcomes (Canova & Cantarutti, Citation2020). We hypothesized that while most forms of CM would be associated with subsequent IPV victimization, the effects would be strongest for self-reported cases.

Method

Data sources

This longitudinal birth cohort study of IPV victimization in 30-year-olds used data from the “Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy” (MUSP) in Queensland, Australia (A. R. Najman et al., Citation2015). The University of Queensland Behavioral and Social Sciences Ethical Review Committee approved the study. The study collected data from 7,223 patients who had given birth to live singleton infants at Brisbane’s principal obstetrics hospital between 1981 and 1983 (A. R. Najman et al., Citation2015). Participants in the initial study were approached at their first prenatal hospital visit. Mothers and children were evaluated at the time of delivery, as well as when the children were 6 months, 5 years, 14 years, 21 years, and 30 years old. Additional information regarding follow-up at each stage of the study is available in previous reports (A. R. Najman et al., Citation2015). Of the original sample, 2,861 (40%) were contacted at 30 years old, with data collection having been completed in 2014 (A. R. Najman et al., Citation2015). This study involved 2,401 of the 2,861 adults who were contacted (84%), with data on both CM and IPV at the 30-year follow-up. Attrition was largely due to difficulties arising from changes of residence and contact details. For example, at 21-year follow-up, only 4.1% of traceable participants did not participate, while only 1.6% of 30-year-olds refused (Kisely & Najman, Citation2022).

Sample demographics

Of the 2,401 participants who provided data at 30-year follow-up, 1,449 were females (60.3%) and 952 (39.7%) were males. One hundred and fifty-four (6.4%) were non-White while 654 (28.5%) were born into a low-income household. Low income at baseline was defined as the lowest 20–25% of family incomes based on Australian data at the time of study entry and consistent with the National Poverty Line (Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, Citation2013). The parents of 224 participants (9.3%) were not living together at the time of their birth. Attrition from baseline was greater among participants who were male, or non-White as well as those whose parents were not living together at the time of their birth, and/or on a low income ().

Table 1. Factors significantly associated with loss to follow-up.

Agency-reported CM predictor measures

We used child protection agency notifications up to September 2000, at which time participants had reached the age of approximately 16 years. Data from the cohort at 14-year follow-up indicated that 4,986 (95.7%) of participants were still living in Queensland. We linked these data to the MUSP cohort with an anonymized identification number (Strathearn et al., Citation2009). There were 4 potentially overlapping CM subtypes: physical, sexual, or emotional abuse, and/or neglect. Reports were substantiated if, after investigation, there was a reasonable belief that CM had occurred.

Self-reported CM predictor measures

A validated instrument, the Child Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ), was administered at 30-year follow-up. This questionnaire has five sub-scales of five items covering experiences up to 16 years old (Bernstein et al., Citation2003). The physical and emotional neglect scales were combined to facilitate comparisons with agency reports of “neglect” in this work, as well as earlier MUSP papers on psychiatric disorders (Kisely et al., Citation2021). This involved using the highest score from either the physical neglect or emotional neglect sub-scales as the score for the overall category of “neglect.” The continuous subscale scores were split into “none/low” and “moderate/severe,” but we also carried out sensitivity analyzes of dividing scores into “severe” versus “all other” categories. Thresholds were determined by previously published sensitivity and specificity criteria (J. M. Najman et al., Citation2020).

IPV outcome/dependent measures

Intimate partner violence at 30-year follow-up was assessed using 30 items of the Composite Abuse Scale (CAS; Hegarty et al., Citation1999, Citation2005). This is a self-report questionnaire that covers possible abuse in the most recent 12 months by a current or previous partner. Each response is rated on a six-point scale from “never” to “daily.” Internal consistency is high for all items (α = 0.95) as well as the four subscales. Specifically, it is 0.90 for the eleven items for “emotional IPV;” 0.89 for the seven items for “physical IPV;” 0.72 for the four items for “harassment;” and 0.79 for the eight items for “severe combined abuse” of all forms of IPV victimization. The CAS has been widely translated and reliably measures IPV types and severity with high concurrent, criterion, discriminant, and construct validity worldwide (Hegarty & Valpied, Citation2013; Hegarty et al., Citation1999, Citation2005).

Areas covered by the CAS include disparaging remarks about appearance, intelligence or mental health, controlling behavior, isolation from family or friends, and physical or sexual violence. The severe combined abuse included rape or the experience of violence with a knife, gun, or other weapon. As in previous work, numbers of each IPV experience were summed to yield the total score (Abajobir et al., Citation2017). As recommended in the CAS manual, five mutually non-exclusive composite indices of IPV (i.e., “emotional IPV,” “physical IPV,” “harassment,” and “severe combined abuse”) were then generated using recommended cutoff scores for each subscale (i.e., ≥3 “emotional IPV,” ≥1 “physical IPV,” ≥2 “harassment,” and ≥ 1 “severe combined abuse;” Hegarty & Valpied, Citation2013). The four dichotomous subscales were summed and dichotomized into the top 10% and bottom 90% of scores to generate an overall or combined victimization variable (α = 0.93).

As suggested by the designers of the CAS, the instrument was supplemented with a question about whether participants had ever feared their partner over their lifetime, as well as the previous 12 months (Signorelli et al., Citation2022). These questions demonstrated acceptable sensitivity and specificity with the CAS (Signorelli et al., Citation2022). For instance, fear in the previous 12 months had an area under the receiver operating curve (ROC) value of 0.80 (95% CIs = 0.78–0.81; Signorelli et al., Citation2022).

Covariates

We adjusted for covariates that had previously shown associations with self- or agency-reported maltreatment in this cohort (Kisely et al., Citation2021). Depending on the specific CM variable, this included sex at birth and being unemployed or on government benefits at 30-year follow-up, as well as participants’ parents not living together at the time of their birth, and/or being considered low-income at baseline. Covariates were added that were associated with IPV victimization based on a review of the literature and previous work (Abajobir et al., Citation2017). These included participants who were unmarried, female, or noted to have had aggressive behavior at 14 years old, as well as those whose mothers reported negative life events on the Life Events Scale from the first antenatal clinic visit to 5-year follow-up (Holmes & Rahe, Citation1967) These were similar to our earlier study of IPV at 21-year follow-up thereby allowing comparisons between the two studies (Abajobir et al., Citation2017).

Analyses

First, we used odds ratios and their 95% confidence intervals to examine bivariate associations between the predictor, covariate, and outcome variables. We then ran separate logistic regression models for each CM and IPV category to calculate adjusted estimates of the association between CM, the covariates, and all five forms of intimate partner violence victimization. Statistical significance was set at less than 0.05. There were also two sets of sensitivity analysis. Firstly, we ran separate analyzes by sex. Secondly, we ran a propensity analysis in which we added a variable representing the baseline confounders across the whole cohort at risk of exposure. This was to identify possible effects of differential attrition on the association between CM and IPV.

Results

Of the 2,401 young adults at 30-year follow-up, 589 (24.5%) reported experiencing one or other CM type, with 322 (13.4%) describing it as severe. Neglect was the most frequent (n = 372), followed by emotional (n = 223), sexual (n = 196) and physical abuse (n = 192).

There were fewer agency-notified cases of CM. For instance, 137 (5.7%) had some type of notification by the age of 16. In order of frequency, these were physical abuse (n = 76), neglect (n = 65), emotional abuse (n = 62), and sexual abuse (n = 50). Seventy-eight (3.2%) were substantiated, most commonly for physical and emotional abuse, followed by neglect and sexual abuse.

Self- or agency-reported CM and combined IPV victimization

The overall prevalence of combined IPV victimization was 10.2% (n = 245). On unadjusted analyzes, the following variables were associated with combined IPV at follow-up: non-married status and being unemployed or on a pension by the age of 30, as well as evidence of aggression by the age of 14, and overall self- or agency-reported maltreatment (). Associations on adjusted analyzes remained statistically significant for self-reported maltreatment, as well as non-married status, and being unemployed or on a pension by the age of 30 ().

Table 2. Factors associated with combined IPV victimization at 30 years old.

Results for combined IPV victimization were significant for all sub-types of self-reported CM, as well as severe maltreatment, on both unadjusted and adjusted analyzes (). However, none of the results were significant for agency-notified or substantiated CM ().

Table 3. Child maltreatment subtypes and combined IPV victimization at 30 years old.

Self- or agency-reported CM and fear of a partner

Seventeen percent of the participants (n = 409) reported having been afraid of their partner at some time in their life. Associated variables were similar to those of combined IPV victimization, except that over 90% were female (OR = 8.29; 95% CIs = 5.87–11.71; p < 0.001). Results for self-reported CM and all the sub-types were significant on both unadjusted and adjusted analyzes (). By contrast, the only result that was significant for agency-reported CM was that for sexual abuse, where there were significant associations between lifetime-ever fear of a partner and both notifications (ORadj = 2.41; 95% CIs = 1.30–4.54; p = 0.006) and substantiated reports (ORadj = 4.83; 95% CIs = 1.99–11.69; p < 0.001). There were similar findings for the 92 participants who reported fear of their partner in the previous 12 months except that the results for substantiated sexual abuse were no longer significant ().

Table 4. Child maltreatment subtypes and lifetime- or 12-month fear of partner at 30 years.

Subgroup analyses by self-reported CM and IPV victimization sub-categories

In terms of the IPV victimization sub-categories, 3.9% (n = 94) reported severe combined abuse, while the percentages reporting physical abuse, harassment, and emotional abuse were 10.9% (n = 261), 7.5% (n = 180) and 16.7% (n = 402), respectively. As was the case with IPV victimization overall, there was a strong and statistically significant association between all forms of CM and severe combined, physical, harassment, or emotional IPV victimization ().

Table 5. Factors associated with subtypes of interpersonal violence victimization at 30 years old.

Subgroup analyses by self-reported CM and IPV victimization sub-categories

Results for the associations between IPV victimization subtypes and agency-reported or substantiated maltreatment were mixed. On unadjusted analyzes, all agency-reported or substantiated subtypes showed a significant association with severe combined IPV. The only exception was agency-notified emotional abuse. However, on adjusted analyzes, only the results for substantiated neglect and sexual abuse remained significant ().

Table 6. Child maltreatment and severe combined or physical IPV at 30 years old.

The results for the other forms of IPV were even less consistent. In the case of physical IPV, both notified and substantiated CM overall, as well as the physical abuse subtypes, were significantly associated, although only notified CM showed a significant association on adjusted analyzes (). In the case of harassment, there were significant results on unadjusted analyzes for notifications overall (OR = 1.83; 95% CIs = 1.07–3.11; p = 0.03) and physical abuse that was notified (OR = 2.31; 95% CIs = 1.19–4.46; p = 0.01) or substantiated (OR = 3.03; 95% CIs = 1.23–7.48; p = 0.02) but none were significant after adjustment. The only finding that was significant for emotional IPV was that for notified sexual abuse, including the adjusted results (ORadj = 1.91; 95% CIs = 1.00–3.65; p = 0.05)

Sensitivity analyses

Running separate analyzes by sex did not greatly alter the findings for self-reported CM with the exception that the findings for sexual abuse and physical or emotional IPV were no longer significant in males. However, there were different results by sex in the case of agency-reported CM. For instance, results for males were no longer significant for the association between substantiated neglect and severe combined IPV or between notified sexual abuse and emotional IPV. By contrast, there were significant results in females for the association between severe combined IPV and notified neglect in addition to the previously significant results for substantiated neglect (). There were also significant associations for substantiated emotional or sexual abuse and more than one substantiation (). Similarly, in the case of physical IPV, results were now significant for notified subtypes of neglect and sexual abuse in addition to the previously significant overall category (). Results for females were unchanged for harassment or emotional IPV (data not shown). Finally, results for fear of a partner over a lifetime were unchanged although those for fear in the previous 12 months were no longer significant, possibly because of inadequate power (data not shown).

Table 7. Factors associated with severe combined or physical IPV at 30 years old in females.

There was little change to the results in propensity score analyzes using baseline covariates across the entire cohort (e.g., the result for overall CM and physical IPV was 1.89 (95% CIs = 1.18–3.02; p = 0.008), while that for sexual abuse and severe combined IPV was 5.39 (95% CIs = 1.64–17.7; p = 0.006).

Discussion

We believe this is the first study to consider 30-year outcomes of both self- and agency-reported CM on IPV in adulthood following adjustment for hypothesized common causes of CM and IPV. Unlike previous reports of the same cohort at 21 years old that was restricted to agency-reported CM (Abajobir et al., Citation2017), this study also considered self-reported CM. Self-reported CM of all types showed the strongest associations with all types of IPV later in life. Effects for the overall categories of agency-reported and/or substantiated CM were restricted to severe combined or physical IPV and less marked than in our previous study at 21-year follow-up (Abajobir et al., Citation2017). Of the CM subtypes, substantiated neglect and sexual abuse showed statistically significant associations with severe combined IPV, while notified CM was significantly associated with physical IPV victimization. Notified sexual abuse also showed a significant association with emotional IPV victimization Associations with a small number of additional agency-reported subtypes were significant for females, but not males. Otherwise, there were few differences between genders. There were similar findings for the association between lifetime-ever fear of a partner and self-reported CM; however, in the case of agency-reported cases, results were only significant for sexual abuse. Our findings for IPV therefore reflect those of other adverse psychosocial outcomes that have been shown to follow both self- and agency-reported CM, even though the strength of that association may vary (Kisely et al., Citation2021; Mills et al., Citation2016; Newbury et al., Citation2018; Scott et al., Citation2012).

There may be several explanations for the differences in findings between the two reporting sources. One is that different people are identified by the two methods (J. M. Najman et al., Citation2020). Another is that IPV may differentially affect recall of CM, although there is also evidence that people are accurate reporters of childhood maltreatment experiences (Pinto et al., Citation2014). Self-reported data may give a more comprehensive picture than reports to agencies because the latter could only represent the most extreme cases of child maltreatment, backed up with physical evidence. Agency reports may only be filed in situations where there is a physical threat to the child, disregarding less conspicuous experiences of abuse and neglect. Another problem is that reports to agencies or organizations might not accurately reflect the extent to which CM is truly occurring, resulting in an underpowered study that failed to detect statistically significant associations.

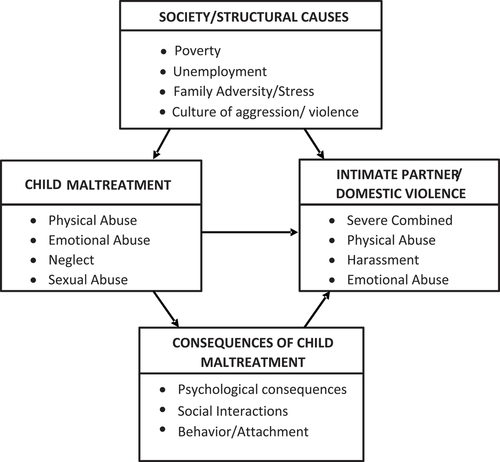

There may be a number of explanations for our results (). One is that the cumulative impact of CM has a direct effect on mental health or emotional development and thus a greater likelihood of experiencing or carrying out IPV (Anda et al., Citation2006; Arata et al., Citation2007). Childhood maltreatment may also adversely affect the development of social skills leading to difficulty in establishing healthy relationships (Wyatt et al., Citation2000).

Figure 1. Possible interactions between childhood maltreatment and interpersonal violence victimization.

Psychosocial problems and adverse life events in the family can also contribute as they are associated with both CM and IPV (Thornberry & Henry, Citation2013). Additional factors include early economic disadvantage and aggression in adolescence (Abajobir et al., Citation2017; Costa et al., Citation2015), or witnessing domestic violence in general (Abajobir et al., Citation2017) However, after adjusting for many of these variables (household income and parental relationship at birth, maternal life-events in the first 5 years and offspring’s aggression at 14 years old), we found that self-reported CM, as opposed to agency-reported cases, still had an independent association with IPV victimization. A disadvantaged background, or aggression in adolescence, do not therefore completely explain our findings of an association between self-reported CM and IPV victimization.

Finally, there were no major differences between sexes in the association between CM and IPV victimization, any differences being restricted to the small number of agency-reported cases. This is in keeping with most other studies using population-based samples (Li et al., Citation2019; Stith et al., Citation2000), although this finding of gender asymmetry in such populations is not universal (Desai et al., Citation2002). In this sample, at least, both males and females had vulnerabilities and psychological responses in common, such as low self-esteem, difficulty in establishing healthy relationships, and impaired emotional regulation, thereby placing them at increased risk of subsequent IPV victimization. By contrast, studies using clinical samples do find gender asymmetry in females and these generally measure more serious IPV victimization (Li et al., Citation2019; Stith et al., Citation2000). Two kinds of IPV victimization have therefore been proposed (Johnson, Citation2005). One is severe and linked to gender, called patriarchal terrorism, and is found in clinical samples (Johnson, Citation2005). The other, common couple violence, is found more equally between genders and seen in population surveys such as in this study (Johnson, Citation2005).

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include follow-up of a large cohort from birth to 30 years old, thereby allowing adjustment for covariates at individual and family levels. In contrast to other work, we used objective, agency-reported CM, thereby minimizing the potential effects of recall bias (McGee et al., Citation1995). A validated instrument was administered to measure subsequent IPV. Finally, we considered the effect on four different IPV categories of CM subtypes.

A limitation of this study is that, due to its longitudinal nature spanning over a period of 30 years, there was attrition and the participants not included at follow-up had higher levels of social disadvantage (Kisely et al., Citation2021). Thus, the generalizability of this study is limited. However, previous research on the MUSP cohort shows that missing data have little effect on measures of association (Saiepour et al., Citation2019), with results being similar using multiple imputation (Najman et al., Citation2015; Saiepour et al., Citation2019). This reflects findings from other long-term studies (Wolke et al., Citation2009). Finally, our results were similar using propensity score analyzes that took into account covariates at baseline across the entire MUSP cohort.

Another potential limitation was the relatively low number of agency-notified cases, especially sexual CM. In line with the general literature on actual incidence versus identified cases of abuse or neglect, the relatively low number of agency-notified cases in this study may similarly suggests that the actual number of cases could be higher than the levels reported. Furthermore, this low number may not have been sufficient to detect statistically meaningful results for some of the outcomes. This may also be an explanation for the smaller number of statistically significant results for agency-notified CM than those at the 21-year follow-up (Abajobir et al., Citation2017). However, this would not account for the strong association between agency-substantiated sexual abuse (the least common CM type) and both severe combined IPV victimization or lifetime-ever fear of a partner, nor would it explain the significant associations between severe combined or physical IPV and notified or substantiated neglect in analyzes restricted to females. A further limitation is that notifications to statutory authorities in one jurisdiction from 15 to 20 years ago may not reflect more recent practice or policies elsewhere. Finally, we did not adjust for multiple testing given the a priori nature of the hypotheses. However, the risk of false-positive findings should be considered in the interpretation of our findings, particularly the agency-reported cases where p-values were higher than those for self-reported CM.

Implications

In terms of possible interventions, there is no one cause of IPV, rather IPV results from an interaction of multiple and interrelated factors at individual, familial, community, and societal levels (Campo, Citation2015). However, CM is one of the many risk factors for subsequent IPV victimization that are present from adolescence, or before, and a risk factor that could therefore be a target for primary prevention (Niolon, Citation2017; Olds, Citation2006). Possible interventions include early childhood home visits and preschool enrichment including family engagement and assistance with parenting skills (Niolon, Citation2017). Examples include the Nurse – Family Partnership (NFP) program that provides support and education to vulnerable families through home visits both before and after birth in the United States (Olds, Citation2006). Other initiatives such as Child Parent Centers and Early Head Start can enhance the pre-school with positive effects on their cognitive skills, academic achievement, social skills, and behavior, all of which help will likely reduce CM child abuse and subsequent IPV (Niolon, Citation2017). Later on, school-based initiatives such as the Strengthening Families program can target children exposed to both CM and domestic violence (Spoth et al., Citation2004). Greater individual support for children and their families who are at risk may also help (Costa et al., Citation2015). This might include programs to prevent alcohol and drug use among teens, especially for vulnerable youths facing multiple challenges, such as the Communities That Care model (Costa et al., Citation2015). Lastly, screening people presenting with IPV for past experiences of CM is recommended by the World Health Organization as a prelude to possible trauma-informed care (Campo, Citation2015; Feder et al., Citation2013; Niolon, Citation2017). This does not always mean direct treatment of trauma from childhood. Instead, it suggests that clinicians should be aware that people who seek help might have experienced trauma when younger and that presenting symptoms might be connected to that past trauma (Knight, Citation2015).

Conclusion

The findings of this study suggest that IPV victimization is likely another adverse outcome, among many, of CM. However, further research is indicated with larger samples to specifically study the role of agency-reported CM given the present study may have been underpowered to achieve statistical significance for this CM type. Primary and secondary prevention can include home visits, both before and after birth (Olds, Citation2006), and school-based initiatives for children exposed to both CM and domestic violence (Spoth et al., Citation2004), as well as screening people presenting with IPV for a history of CM (Feder et al., Citation2013).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abajobir, A. A., Kisely, S., Williams, G. M., Clavarino, A. M., & Najman, J. M. (2017). Substantiated childhood maltreatment and intimate partner violence victimization in young adulthood: A birth cohort study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(1), 165–179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0558-3

- Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., Bremner, J. D., Walker, J. D., Whitfield, C., Perry, B. D., Dube, S. R., & Giles, W. H. (2006). The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 256(3), 174–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4

- Arata, C. M., Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J., Bowers, D., & O’Brien, N. (2007). Differential correlates of multi-type maltreatment among urban youth. Child Abuse and Neglect, 31(4), 393–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.09.006

- Archer, J. (2000). Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 126(5), 651. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.651

- Barrios, Y. V., Gelaye, B., Zhong, Q., Nicolaidis, C., Rondon, M. B., Garcia, P. J., Sanchez, P. A. M., Sanchez, S. E., Williams, M. A., & Elhai, J. D. (2015). Association of childhood physical and sexual abuse with intimate partner violence, poor general health and depressive symptoms among pregnant women. PLOS ONE, 10(1), e0116609. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0116609

- Benedini, K. M., Fagan, A. A., & Gibson, C. L. (2016). The cycle of victimization: The relationship between childhood maltreatment and adolescent peer victimization. Child Abuse and Neglect, 59, 111–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.08.003

- Bernstein, D. P., Stein, J. A., Newcomb, M. D., Walker, E., Pogge, D., Ahluvalia, T., Stokes, J., Handelsman, L., Medrano, M., Desmond, D., & Zule, W. (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the childhood trauma questionnaire. Child Abuse and Neglect, 27(2), 169–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0

- Campo, M. (2015). Children’s exposure to domestic and family violence: Key issues and responses. Journal of the Home Economics Institute of Australia, 22(3), 33.

- Canova, C., & Cantarutti, A. (2020). Population-Based Birth Cohort Studies in Epidemiology. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(15), 5276. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155276

- Costa, B. M., Kaestle, C. E., Walker, A., Curtis, A., Day, A., Toumbourou, J. W., & Miller, P. (2015). Longitudinal predictors of domestic violence perpetration and victimization: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 24, 261–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2015.06.001

- Davis, J. L., & Petretic-Jackson, P. A. (2000). The impact of child sexual abuse on adult interpersonal functioning: A review and synthesis of the empirical literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 5(3), 291–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1359-1789(99)00010-5

- Desai, S., Arias, I., Thompson, M. P., & Basile, K. C. (2002). Childhood victimization and subsequent adult revictimization assessed in a nationally representative sample of women and men. Violence and Victims, 17(6), 639–653. https://doi.org/10.1891/vivi.17.6.639.33725

- Feder, G., Wathen, C. N., & MacMillan, H. L. (2013). An evidence-based response to intimate partner violence: WHO guidelines. JAMA, 310(5), 479–480. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.167453

- Gómez, A. M. (2010). Testing the cycle of violence hypothesis: Child abuse and adolescent dating violence as predictors of intimate partner violence in young adulthood. Youth & Society, 43(1), 171–192.

- Hamel, J. (2020). Explaining symmetry across sex in intimate partner violence: Evolution, gender roles, and the will to harm. Partner Abuse, 11(3), 228–267. https://doi.org/10.1891/PA-2020-0014

- Hegarty, K., Bush, R., & Sheehan, M. (2005). The composite abuse scale: Further development and assessment of reliability and validity of a multidimensional partner abuse measure in clinical settings. Violence and Victims, 20(5), 529–547. https://doi.org/10.1891/vivi.2005.20.5.529

- Hegarty, K., Sheehan, M., & Schonfeld, C. (1999). A multidimensional definition of partner abuse: Development and preliminary validation of the composite abuse scale. Journal of Family Violence, 14(4), 399–415. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022834215681

- Hegarty, K., & Valpied, J. (2013). Composite Abuse Scale (CAS) Manual. Department of General Practice, University of Melbourne.

- Herrenkohl, T. I., Mason, W. A., Kosterman, R., Lengua, L. J., Hawkins, J. D., & Abbott, R. D. (2004). Pathways from physical childhood abuse to partner violence in young adulthood. Violence and Victims, 19(2), 123–136. https://doi.org/10.1891/vivi.19.2.123.64099

- Holmes, T. H., & Rahe, R. H. (1967). The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 11(2), 213–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3999(67)90010-4

- Ireland, T. O., & Smith, C. A. (2009). Living in partner-violent families: Developmental links to antisocial behavior and relationship violence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(3), 323–339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-008-9347-y

- Johnson, M. P. (2005). Domestic violence: It’s not about gender: Or is it? Journal of Marriage and the Family, 1126–1130. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00204.x

- Kisely, S., & Najman, J. M. (2022). A study of the association between psychiatric symptoms and oral health outcomes in a population-based birth cohort at 30-year-old follow-up. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 157, 110784. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2022.110784

- Kisely, S., Strathearn, L., Mills, R., & Najman, J. M. (2021). A comparison of the psychological outcomes of self-reported and agency-notified child abuse in a population-based birth cohort at 30-year-follow-up. Journal of Affective Disorders, 280(Pt A), 167–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.017

- Knight, C. (2015). Trauma-informed social work practice: Practice considerations and challenges. Clinical Social Work Journal, 43(1), 25–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-014-0481-6

- Linder, J. R., & Collins, W. A. (2005). Parent and peer predictors of physical aggression and conflict management in romantic relationships in early adulthood. Journal of Family Psychology, 19, 252–26.

- Li, S., Zhao, F., & Yu, G. (2019). Childhood maltreatment and intimate partner violence victimization: A meta-analysis. Child Abuse and Neglect, 88, 212–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.11.012

- McGee, R. A., Wolfe, D. A., Yuen, S. A., Wilson, S. K., & Carnochan, J. (1995). The measurement of maltreatment: A comparison of approaches. Child Abuse and Neglect, 19(2), 233–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/0145-2134(94)00119-F

- Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research. (2013). Poverty lines: Australia March quarter 2013. The University of Melbourne.

- Messman-Moore, T. L., & Long, P. J. (2000). Child sexual abuse and revictimization in the form of adult sexual abuse, adult physical abuse, and adult psychological maltreatment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 15(5), 489–502. https://doi.org/10.1177/088626000015005003

- Messman-Moore, T. L., & Long, P. J. (2003). The role of childhood sexual abuse sequelae in the sexual revictimization of women: An empirical review and theoretical reformulation. Clinical Psychology Review, 23(4), 537–571. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(02)00203-9

- Mills, R., Kisely, S., Alati, R., Strathearn, L., & Najman, J. (2016). Self-reported and agency-notified child sexual abuse in a population-based birth cohort. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 74, 87–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.12.021

- Najman, A. R., Bor, W., Clavarino, A., Mamun, A., McGrath, J. J., McIntyre, D., O’Callaghan, M., Scott, J., Shuttlewood, G., Williams, G. M., & Wray, N. (2015). Cohort Profile Update: The Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy (MUSP). International Journal of Epidemiology, 44(1), 78–78f. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyu234

- Najman, J. M., Kisely, S., Scott, J. G., Strathearn, L., Clavarino, A., Williams, G. M., Middeldorp, C., & Bernstein, D. (2020). Agency notification and retrospective self-reports of childhood maltreatment in a 30-year cohort: Estimating population prevalence from different data sources. Child Abuse and Neglect, 109, 104744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104744

- Newbury, J. B., Arseneault, L., Moffitt, T. E., Caspi, A., Danese, A., Baldwin, J. R., & Fisher, H. L. (2018). Measuring childhood maltreatment to predict early-adult psychopathology: Comparison of prospective informant-reports and retrospective self-reports. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 96, 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.09.020

- Niolon, P. H. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). Preventing intimate partner violence across the lifespan: A technical package of programs, policies, and practices. Government Printing Office.

- Noll, J. G., Horowitz, L. A., Bonanno, G. A., Trickett, P. K., & Putnam, F. W. (2003). Revictimization and self-harm in females who experienced childhood sexual abuse results from a prospective study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 18(12), 1452–1471. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260503258035

- Olds, D. L. (2006). The nurse-family partnership: An evidence-based preventive intervention. Infant Mental Health Journal, 27(1), 5–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.20077

- Pinto, R., Correia, L., & Maia, Â. (2014). Assessing the reliability of retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences among adolescents with documented childhood maltreatment. Journal of Family Violence, 29(4), 431–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-014-9602-9

- Saiepour, N., Najman, J., Ware, R., Baker, P., Clavarino, A., & Williams, G. (2019). Does attrition affect estimates of association: A longitudinal study. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 110, 127–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.12.022

- Scott, K. M., McLaughlin, K. A., Smith, D. A., & Ellis, P. M. (2012). Childhood maltreatment and DSM-IV adult mental disorders: Comparison of prospective and retrospective findings. British Journal of Psychiatry, 200(6), 469–475. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.111.103267

- Signorelli, M., Taft, A., Gartland, D., Hooker, L., McKee, C., MacMillan, H., Brown, S., & Hegarty, K. (2022). How valid is the question of fear of a partner in identifying intimate partner abuse? A cross-sectional analysis of four studies. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(5–6), 2535–2556. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520934439

- Spoth, R., Redmond, C., Shin, C., & Azevedo, K. (2004). Brief family intervention effects on adolescent substance initiation: School-level growth curve analyses 6 years following baseline. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(3), 535–542. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.535

- Stevens, T. N., Ruggiero, K. J., Kilpatrick, D. G., Resnick, H. S., & Saunders, B. E. (2005). Variables differentiating singly and multiply victimized youth: Results from the national survey of adolescents and implications for secondary prevention. Child Maltreatment, 10(3), 211–223. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559505274675

- Stith, S. M., Rosen, K. H., Middleton, K. A., Busch, A. L., Lundeberg, K., & Carlton, R. P. (2000). The intergenerational transmission of spouse abuse: A meta‐analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(3), 640–654. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00640.x

- Strathearn, L., Mamun, A. A., Najman, J. M., & O’Callaghan, M. J. (2009). Does breastfeeding protect against substantiated child abuse and neglect? A 15-year cohort study. Pediatrics, 123(2), 483–493. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-3546

- Sunday, S., Kline, M., Labruna, V., Pelcovitz, D., Salzinger, S., & Kaplan, S. (2011). The role of adolescent physical abuse in adult intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(18), 3773–3789. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260511403760

- Thornberry, T. P., & Henry, K. L. (2013). Intergenerational continuity in maltreatment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41(4), 555–569. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-012-9697-5

- Trickett, P. K., Noll, J. G., & Putnam, F. W. (2011). The impact of sexual abuse on female development: Lessons from a multigenerational, longitudinal research study. Development and Psychopathology, 23(2), 453–476. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579411000174

- Wekerle, C., Wolfe, D. A., Hawkins, D., Pittman, A.-L., Glickman, A., & Lovald, B. E. (2001). Childhood maltreatment, posttraumatic stress symptomatology, and adolescent dating violence: Considering the value of adolescent perceptions of abuse and a trauma mediational model. Development and Psychopathology, 13(4), 847–871. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579401004060

- Widom, C. S., Czaja, S. J., & Dutton, M. A. (2008). Childhood victimization and lifetime revictimization. Child Abuse and Neglect, 32(8), 785–796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.12.006

- Widom, C. S., Czaja, S., & Dutton, M. A. (2014). Child abuse and neglect and intimate partner violence victimization and perpetration: A prospective investigation. Child Abuse and Neglect, 38(4), 650–663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.11.004

- Widom, C. S., Raphael, K. G., & DuMont, K. A. (2004). The case for prospective longitudinal studies in child maltreatment research: Commentary on Dube, Williamson, Thompson, Felitti, and Anda (2004). Child Abuse and Neglect, 28(7), 715–722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.03.009

- Widom, C. S., Weiler, B. L., & Cottler, L. B. (1999). Childhood victimization and drug abuse: A comparison of prospective and retrospective findings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67(6), 867–880. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.67.6.867

- Williams, L. M. (1994). Recall of childhood trauma: A prospective study of women’s memories of child sexual abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62(6), 1167–1176. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.62.6.1167

- Wolke, D., Waylen, A., Samara, M., Steer, C., Goodman, R., Ford, T., & Lamberts, K. (2009). Selective drop-out in longitudinal studies and non-biased prediction of behaviour disorders. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 195(3), 249–256. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.108.053751

- Wyatt, G. E., Axelrod, J., Chin, D., Carmona, J. V., & Loeb, T. B. (2000). Examining patterns of vulnerability to domestic violence among African American women. Violence Against Women, 6(5), 495–514. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801200006005003