Abstract

Corruption is recurrent in conversations and political debates, but it can have different meanings. This study aimed to assess how the words that 1,020 citizens and 120 politicians in Portugal associated with corruption interacted and varied. Data came from two surveys that collected responses to “What words do you associate with corruption?” from October 2020 to April 2021: the EPOCA-FCT survey conducted with citizens and the ETHICS-FFMS survey conducted with MPs and local elected officials in office. We used network analysis to find that the mass-elite incongruence when defining corruption can be used (a) to enhance corruption surveys and (b) as a tool to foster political will for anti-corruption reform in areas/sectors that are linked to corruption. In Portugal, corruption came down to “theft of money by politicians” (citizens) and “dishonesty and illegality in a crony relationship” (politicians), and the promotion of integrity in the Banking sector emerged as central to any anti-corruption reform. This was the first attempt to show that knowing what citizens and politicians have in mind can be a valid tool to enhance both the quality of future corruption surveys and the implementation of anti-corruption policies when no short-term political will for a change exists.

When we say “corruption,” it is possible that each one of us interprets its meaning differently. Corruption can be something minimalist and based exclusively on what the laws say, while it can be something maximalist, much more fluid, and linked to a “beyond the law” morality (Gouvêa Maciel & de Sousa, Citation2018; Gouvêa Maciel et al., Citation2022). Regardless of which approach we choose; it is possible to verify that we still know little about what citizens and politicians think when they use the word “corruption.”

Many indirect strategies of “asking about corruption” have been adopted to better understand the phenomenon. Since it is a sensitive subject that can cause some discomfort when answering (de Sousa et al., Citation2021), survey methods have explored the use of proxies to somehow translate what we know so far about corruption extension and experience into numbers, especially in democracy (Doorenspleet, Citation2019; Wysmułek, Citation2019). Nevertheless, much theoretical simplification is at stake when specific behaviors—such as bribery, abuse of power, nepotism, etc.—are considered corruption per se.

The argument of this article is simple: to tackle corruption adequately, we need to know the behaviors, actions, and places that citizens and politicians associate with corruption. Do they use similar expressions to refer to corruption? Do words vary depending on where you are? The first question is addressed here in detail, as there is data available in Portugal to make a direct mass-elite comparison (de Sousa & Coroado, Citation2023; Magalhães & de Sousa, Citation2021). The second may be an object for future investigation in the field.

More than reinforcing the endless discussion about the creation of a precise definition of corruption, this work shows that more emphasis should be placed on the contextual importance of the environment and norms (Jackson & Köbis, Citation2018; Kubbe & Engelbert, Citation2018; Lindner, Citation2014) for those being interviewed, especially those that occupy a position of power (Modesto & Pilati, Citation2020).

Surveys usually leave open the meaning of corruption and do not make any mention of what individuals interpret as being corruption (ISSP Research Group, Citation2016, Citation2018; Transparency International, Citation2017). Other times, the interviewers initially present a definition of corruption to the respondents to clarify what they will be asked about—i.e., the last special surveys on corruption of the European Commission (Citation2022, Citation2023).

Although those are valid approaches, both solutions represent a challenge. If a definition of corruption is not present, there is a risk that the respondents will answer about corruption without being clear or having a concrete understanding of what it is. On the other hand, if a definition of corruption is present, there is also a risk of influence on the respondents. One way or another, those approaches give a margin for personal interpretation. A third (less conventional) approach—the one to be explored here—has been marginally adopted: to use open-ended questions to explore the meanings of corruption itself. “Elites typically […] prefer open questions that allow them to articulate their views in more detail” (Vis & Stolwijk, Citation2021, p. 1290), which can add value to the exploration of the definition of corruption, since politicians should be careful when talking about a sensitive subject like corruption and will tend to avoid them when having to check an option box with predefined possibilities of answers, respond to yes-no items or define a value in a scale (Aberbach & Rockman, Citation2002; Keudel et al., Citation2023). To the best of our knowledge, only two studies in Australia did so with citizens in New South Wales (ICAC, Citation2003, Citation2006) and none did it with political elites.

By taking this “direct” path, it was not only possible to structure a map of the expressions that Portuguese citizens and politicians used to refer to corruption but also to understand the (in)congruence of the various expressions used by both groups. The idea was to explore how mass-elite maximalist overarching definitions—based on existing literature (Pozsgai-Alvarez, Citation2020)—and minimalist definitions of corruption—that are far from universal and influenced by socially determined norms (Heidenheimer, Citation1970; Truman, Citation1971)—interact and vary. We argue that assessing the words associated with corruption can be a valid way to (a) enhance the quality and validity of future corruption surveys and (b) foster political will for anti-corruption reform in specific areas and/or sectors.

To succeed in this endeavor, the article is structured in five additional sections. First, we discuss the importance of delving into the multiple ways to define corruption in a given social context, since it was already found that—contrary to prior expectations—political will to tackle corruption can emerge from the interactions among actors rather than coming from the initiative of specific political actors in power (Keudel et al., Citation2023, p. 19). Second, we describe data and methodology used to map the words that Portuguese citizens and political elite associated with corruption. Third, we present the words each group adopted when referring to corruption and the network of associations they made to define corruption in more than one word. Fourth, we detail the three categories of words that emerged from data analysis. Finally, we discuss these categories all together to provide a set of recommendations for the implementation of anti-corruption policies in economic activities and sectors that can be difficult to occur when no political will exists.

Literature review

First, corruption appears as a special case among many other concepts in the Social Sciences because “unlike [other] issues […], [it] does not give rise to positions for or against [i.e.,] nobody is in favor of corruption” (de Sousa, Citation2008, p. 11). The “negative connotation” of corruption makes it very influenced by any kind of social desirability bias (de Sousa, Citation2018). Closed-ended items that have options like “I don’t know the answer,” “I don’t want to answer,” or “It doesn’t apply to my case” are easy to be doomed. Open-ended items are more difficult to code and subject to higher levels of subjectivity, but they reduce the pressure associated with the necessity of “selecting the right answer” in a questionnaire (Aberbach & Rockman, Citation2002). Corruption surveys have been striving to target corruption and we believe that a more qualitative description of the linkages and flows that characterize corruption can work as a powerful tool to start surveys and experiments (to make sure that all individuals similarly interpret corruption and according to the specific wording used to refer to it in a given country). The idea is that the adoption of a pre-tested definition of corruption when collecting answers from a specific population can boost internal validity.

Second, “corruption as a policy issue is exceptional in the gap between talk and action: all officials can gain from publicly promising to take action, but bringing about change requires extensive effort by a large set of actors” (Keudel et al., Citation2023, p. 3). This is why we need a wider analysis of the definition of corruption, one that presents and combines all definitions of the individuals, instead of reducing it to an “average” definition that is unable to identify “flows,” “ties,” and “changes” (Borgatti et al., Citation2009). We consider that the definition of corruption can be seen as “a system in which large networks of components with no central control and simple rules of operation give rise to complex collective behavior, sophisticated information processing, and adaptation via learning or evolution” (Mitchell, Citation2009, p. 13). Similar to the way avian flocks consist of flying birds that adjust their positions within the group, corruption is made up of various dimensions and aspects that interact and adapt, ultimately forming a larger, adaptive concept. This understanding can be beneficial in fostering political will for change.Footnote1

Data and methods

The data for this study originated from an open-ended question: “When you hear about corruption, what words do you associate with this subject?” This question was part of two simultaneous initiatives. The first initiative was the EPOCA-FCT Survey (Magalhães & de Sousa, Citation2021). The survey aimed to gauge the perceptions, attitudes, and practices of residents in Portugal regarding various aspects of corruption. Between December 19, 2020, and April 21, 2021, a total of 1,020 responses were gathered from a representative sample that included residents of both genders, aged between 18 and 75, in Mainland Portugal and/or in any of the Portuguese Autonomous Regions (Azores and Madeira). The sample was stratified by NUTS-II and habitat, ensuring representation in terms of NUTS-II, habitat, gender, age, and level of education based on the 2011 Portuguese National Census (Instituto Nacional de Estatística, Citation2014). Respondents were randomly selected for a direct and personal interview in their residence, facilitated by a Computer-assisted Personal Interviews (CAPI) system. The questionnaire was developed by the Instituto de Ciências Sociais of the Universidade de Lisboa. The response rate for the interviews was 30.1% (Pereira et al., Citation2023).

The second dataset utilized in this study was derived from the ETHICS-FFMS Survey (de Sousa & Coroado, Citation2023). This survey aimed to gauge the perspectives of political officeholders on ethics in politics and employed a Computer-Assisted Web Interviewing (CAWI) methodology. Emails containing a questionnaire link were sent to 846 politicians in Portugal, including members of the parliament (MPs), aldermen, and mayors. The survey took place between October 12, 2020, and February 8, 2021, with an emphasis on not collecting sensitive information (such as party affiliation and specific political positions at the municipal level) to prevent the identification of individual MPs, aldermen, and mayors. The response rate for the survey was 14.1%, with a total of 120 participants (N = 120).Footnote2

Although our survey lacked a representative number of politicians, it still reflected the demographic diversity observed among Portuguese legislators. The average age of elected officials in our sample was 52 years, compared to the overall average of 49 years in the Portuguese parliament, the Assembleia da República. Additionally, the average years of experience in office for participants in our elite survey (6.3 years) closely matched the actual average of 7 years in office.

However, our elite sample exhibited some discrepancies when compared to real figures. Female participation, constituting nearly 31% of the total, fell short of the actual average of 40%. Moreover, there was a higher reported left-wing preference (75.1%) in our survey compared to the observed reality (62.6%) (de Sousa & Gouvêa Maciel, Citation2022, pp. 36–37; Pereira et al., Citation2023).

Despite these disparities, we did not consider the more male-centered composition of our elite sample to be inherently problematic. This choice was informed by previous research indicating that males are more susceptible to accepting greed corruption (Bauhr & Charron, Citation2020; Kubbe & Merkle, Citation2022), and political elites with a higher male presence tend to display greater inclinations toward corruption (Bauhr & Charron, Citation2021).

Additionally, the average Left-Right political scale, ranging from 1 (Extreme Left) to 7 (Extreme Right), was consistent across surveys (scoring 3 in this scale). This uniformity suggested that citizens and politicians in Portugal shared similar levels of left-wing preference, facilitating a meaningful comparison between the two groups (de Sousa & Gouvêa Maciel, Citation2022, p. 36).

The answers to the question “What words do you associate with corruption?” were then parameterized to give the same meaning to words (a) with incorrect spelling, (b) that appeared in singular or plural forms, (c) in masculine or feminine forms, as well as (d) those that gave more than one meaning to corruption.Footnote3 This exercise constituted a qualitative analysis of all the 3,420 possible responses (for each individual, it was possible to catalog up to three words) that resulted in 290 cataloged unique words about the meaning of corruption in Portugal.

The maps of the existing relationships between words were made recurring to the adoption of Forceatlas2 (Jacomy et al., Citation2014), a force-directed algorithm available at the Gephi Graph Visualization and Manipulation software version 0.10.1. This type of analysis is suitable for simplifying data through images and creating “communities” where there is more interaction (in this specific case, it created “communities” of corruption words). To create these “communities” of expressions, we used modularity, a technique that measures the density of associations within communities compared to associations between communities (Blondel et al., Citation2008). The disadvantage of this procedure is that we end up reducing the resulting analysis of the associations exclusively to the visual level. The benefit is that—instead of having a quantifiable result of “types of definitions”—this technique maps the “paths” of the associations between the three words used to define corruption and provides a visual qualitative interpretation of all meanings citizens and politicians give to corruption.

Words that defined corruption

Before debating the words, one fact called our attention: 235 citizens (out of 1,020) simply could not express what corruption meant. In sum, 23% of the mass public sample surveyed had difficulties in describing the corrupt act, which reveals a significant cleavage between “those who do not have a specific association with the idea of what corruption is” and “those who characterize corruption as something that can be associated with other phenomena.” Meanwhile, the political elite had no difficulties when associating other phenomena with corruption, all 120 politicians fully answered the open-ended question.

This “emptiness” of what corruption may represent to citizens in Portugal can be linked to the fact that the more maximalist, generalized, and mediatic use of the term “corruption” may have created the idea that any unethical and/or dishonest behavior is indeed labeled as corrupt, which makes corruption difficult to describe in words. Thus, corruption gains vague and imprecise contours, ending up being associated with any social transgression where deviant behavior occurs. From this perspective, everything that refers to dishonesty is then likely to be labeled as corrupt. Even a non-payment of the bus ticket or the undue claim of a social security benefit would be considered acts of corruption. However, what makes corruption deserve attention is its singularity as an unethical and dishonest behavior: it involves something else, it involves abuse of power (Modesto & Pilati, Citation2020; Pozsgai-Alvarez, Citation2020). Probably, this is the reason why politicians had no difficulties answering it, even keeping in mind that they were approached to give direct opinions about a sensitive topic.

It is departing from the most common definition of corruption—corruption as “abuse of power for private benefit” (Pozsgai-Alvarez, Citation2020)—that we explore the results in this article. From now on, we try to identify (and discuss) what is seen as unethical, dishonest, and abuse of power in the Portuguese context to develop definitions of corruption that are adjusted to this culture and identify words that can foment political will for anti-corruption reform.

The word citizens used the most was “Money” (10% of the total sample). An association that reflected the importance of the impact that corruption could have on society, especially the financial one. The second word citizens used was “Politicians” (9.6% of the total) and the third, was “Robbery” (8.1% of the total). At the same time, politicians associated corruption more with “Dishonesty” (33.3% of the political elite), “Illegality” (25.8%), and “Cronyism” (24.1%). shows the top five words that citizens and politicians associated with corruption in Portugal.

Table 1. Top five words that citizens and politicians used to define corruption.

In a certain way, these words summarize what populated the minds of citizens and politicians when they referred to something as corrupt. The centrality of “Money,” “Politicians,” and “Robbery” for the popular understanding of corruption was unquestionable. It should be highlighted that this did not mean that only what involved money, politicians, and robbery was perceived as corrupt. This association should not be seen as something limiting, but, on the contrary, it should be considered a starting point for a deeper understanding of corruption.

The same could be said about the political elite: dishonesty and illegality in a crony relationship did not limit what was perceived as corrupt, they only guided the multiple possibilities of expressing what political corruption meant. Thus, we found an evident mass-elite incongruence regarding the definition of corruption in Portugal.

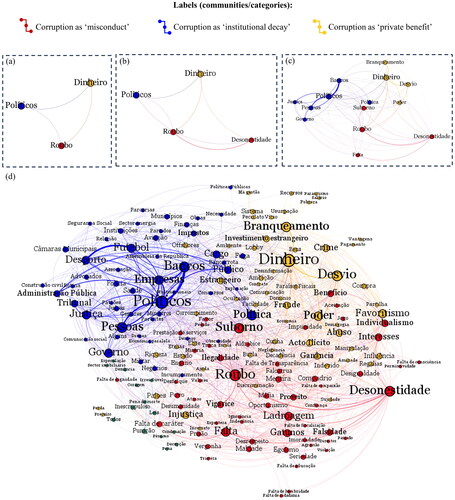

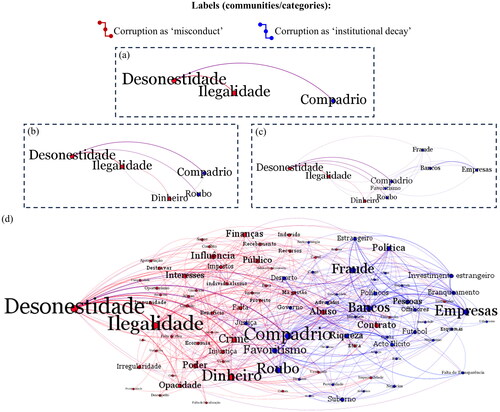

and reveal the relations among words associated with corruption in the “imaginary” of citizens and politicians. Both figures present the most minimalist ( and ) and maximalist maps of words ( and ). Maps show us a much more complex universe for the definition of corruption, depending on the power status.

Figure 1. Communities/categories of words that citizens associated with corruption.

Source: Magalhães and de Sousa (Citation2021).

Figure 2. Communities/categories of words that politicians associated with corruption.

Source: de Sousa and Coroado (Citation2023).

From the citizens’ viewpoint, we identified three major categories/communities of words (). In red, we have words that associate corruption with misconduct, i.e., unfair procedures. In blue, words that describe the relationship of corruption with the most diverse types of institutions, somehow creating an interpretation of corruption based on a process of decay of governance, public-private relations, and/or democratic institutions. In yellow, words related to the results and benefits of corruption (Gouvêa Maciel & de Sousa, Citation2018; Gouvêa Maciel et al., Citation2022; Lessig, Citation2013; Megías et al., Citation2023; Rothstein, Citation2014).

From the politicians’ viewpoint, there was not a clear separation between misconduct and institutional decay, meaning that power status associated with money permeated the other categories. The absence of a “private benefit” category shows how difficult it was for politicians to recognize corruption as a private gain. Instead, politicians used proxies for private benefit, combining them with misconduct or institutional decay, depending on the interests involved.

The maps allow us to draw two conclusions. First, corruption in Portugal was a three-dimensional social construct, involving misconduct, private benefit, and institutional decay. In other words, the definition of corruption was not confined to one of these three categories/communities. It expanded to incorporate the interaction between them, i.e. there were “multiple paths” of words, each of them corresponding to different ways to define corruption. For example, a corrupt act could not involve robbery, but foreign investments; not materialize in money but in power; and not be confined to political institutions but to banks instead. Even without directly involving “Money,” “Politicians,” and “Robbery,” we could still have a corrupt act in the Portuguese conception. The same held for politicians, it was not necessary to have an illegal, dishonest, crony interaction to still have other forms of “being corrupt” emerging.

Second, the most salient words of each category/community carried multiple meanings. Thus, the most used ones operated as symbols (Becquart-Leclercq, Citation1984) that explained the different vocabulary citizens and politicians resorted to when referring to the same construct, corruption.

The meanings of corruption

Corruption as “misconduct”

In this category, citizens highlighted words such as “Robbery” (8.3%), “Dishonesty” (6.9%), “Bribery” (6%), “Lack (absence of)” (5.2%), and “Theft” (4.4%). At the same time, politicians referred to “Dishonesty” (7.5%), “Illegality” (5.8%), “Money” (4.7%), “Abuse” (3.5%), and “Crime” (3.5%) ().

Table 2. Top five words that citizens and politicians used to define corruption as “misconduct.”

In this context, corruption was seen as something disconnected from the legal/formal standards, differentiating practices, and labeling them as objectionable or not. Corruption could be defined here as a morally objectionable action, although not necessarily a crime (de Sousa & Triães, Citation2009), at least for citizens. A large part of the generalized “feeling of corruption” in Portugal was found in this category.

However, corruption could also involve a violation of written contracts (codes and rules that are broken or moral codes that are transgressed), but not necessarily laws (Jancsics, Citation2014). Thus, although morally reprehensible, not all individualistic, self-interested, opportunistic, disrespectful, or dishonest people will be considered corrupt (legally) according to a mass public definition.

What differentiated citizens from politicians was the relevance that illegality and crime (and also money and abuse) had in this category. It seemed that the political elite put “private benefit” and mechanisms to achieve it together with misconduct. In other words, politicians were prone to use the private benefit involved to orient when conduct was corrupt or not.

It is worth mentioning that these words did not appear in a vacuum, they communicated with the remaining communities/categories. There was no dishonesty, illegality, lie, lack (of character, respect, etc.) without resources (money, power, etc.) nor agents/institutions (political, business, etc.). It was interesting to note that “misconduct” was an essential part of the meaning of corruption for both citizens and politicians.

Corruption as “institutional decay”

The most revealing in the maps was the fact that citizens and politicians associated corruption with something more than just “misconduct.” Emphasis also fell on power relations that are defined by institutions present in society, whether public or private. This is a remarking finding, meaning that corruption appeared as something that “goes beyond” contact with public institutions. Particular attention should be given to the political view that associated corruption with business.

One of the top five words in this community/category () stood out due to its private nature: “Banks” (with an occurrence of 7.3% in the entire population and 4.8% among politicians). The other words mentioned by citizens described spheres of public power, “Politicians” (11.7%), “Politics” (6.2%), and “Justice” (5.8%), linked to the personalization and/or individualization of the power status, referring to “People” involved in corrupt acts (7.6%). Politicians mixed misconducts like “Cronyism” (6.3%), “Robbery” (5.7%), “Favoritism” (5%), and “Fraud” (5%) with power coming from private institutions related to “Business” (4.8%) and, more specifically, banks.

Table 3. Top five words that citizens and politicians used to define corruption as “institutional decay.”

The evaluation of the institutional dimension of the definition of corruption was largely asymmetric and based on an outgroup influence (Aguiar et al., Citation2017; Leite et al., Citation2016). While citizens said that corruption came from politicians, politicians said that corruption came from business interests that influenced misconduct in politics.

To put it straightforwardly, corruption (for the Portuguese people), more than the occurrence of a “misconduct” to extract “private benefits,” needs an institutional element, whether an organization or an individual with power status, to happen. Corruption therefore was defined based not only on the conduct but also on the hierarchical and power disparity it generated. It was precisely this dimension of “capacity distortion,” “manipulation” of laws, and direct interaction with private firms that made citizens connect officeholders in power with the very nature of corruption.

Corruption as “private benefit” (only in the eyes of citizens)

As observed, politicians reduced private benefits to misconduct or institutional decay depending on the circumstances of the corrupt behavior. It did not mean that they could not refer to corruption in such terms. It meant that there was a predisposition to reduce the importance of personal benefits to characterize corruption.

Citizens differentiated this category from the previous ones because they emphasized that, for corruption to occur, resources must exist, i.e., corruption needs resources and constitutes a market (Cartier-Bresson, Citation1992, Citation1997). Exchanges between those who seek to obtain a favor, a favorable decision, or power, and those who are in a position to “sell” or “offer” those goods needed to take place for corruption to happen. The most conventional way to materialize a “private benefit” was through “Money” (11.1% of occurrences of expressions in the community/category) (). Other sophisticated forms of benefits may involve financial resources, but they ended up being more indirect and less subject to social condemnation, thus less evident as “misconduct.”

Perhaps for this reason, corruption was not limited to “misconduct” and “institutional decay” in the eyes of citizens. It needed to be associated with an advantage that often goes beyond receiving “cash.” “Deviation/financial diversion” (7% of occurrences), “Money laundering” (5.5%), or even an advantage in terms of “Power” (5.3%) and/or “Favoritism” (4.9%) were equally sufficient to reinforce the idea of corruption as a “private benefit.”

The risk of interpreting corruption solely as a “private benefit” lies heavily on the perils of limiting corruption only to transactions. Recent studies have pointed out that it is necessary to consider “institutional decay” together with “misconducts” and “private benefits” (Gouvêa Maciel & de Sousa, Citation2018; Gouvêa Maciel et al., Citation2022; Kaufmann & Vicente, Citation2011; Lessig, Citation2013; Megías et al., Citation2023; Thompson, Citation2018).

Finally, the interpretation of power appeared to cause a mismatch between citizens’ and politicians’ ideas of corruption. Power status seemed to permeate the entire definition of corruption without being properly analyzed. There is room to further investigate this “gray zone” of corruption definition that resorts to the characteristics of power and serves as a resource to limit what should or should not be considered socially corrupt (Allen & Birch, Citation2012; de Sousa & Gouvêa Maciel, Citation2022; Heidenheimer, Citation1970; Modesto & Pilati, Citation2020).

Table 4. Top-5 words that citizens used to define corruption as “private benefit.”

Conclusion

It is time now to put the different meanings that corruption assumed together. First, we identified that the definition of corruption worked more as a combination of multiple words that interacted and resulted in a macro interpretation of corruption that was more than the sum of all words used. The definition was closer to a combination of expressions that could change depending on whether citizens or politicians expressed them. The maps of words revealed corruption as something contextually defined and not confined to specific words, but rather to the combination of them (and the values they carried when put together) in a given social context. Future research can verify whether or not the corruption “vocabulary” changes depending on the country studied. By doing so, it will become possible to create an even larger map of social definitions of corruption that are specific to each culture.

Second, we found specific ways to operationalize the definitions of corruption in Portugal that considered the levels of interpretation for the meaning of corruption available in the literature (de Sousa et al., Citation2022, p. 16, Part 1). summarizes what Portuguese citizens and politicians defined as corruption at the minimalist and maximalist levels.

Table 5. Definitions of corruption by meaning (at the minimalist and maximalist levels).

By identifying a “Portuguese” version of the minimalist definition, it became possible to locate where corruption was more salient: in the politics-business relations that have happened through ties of friendship preferably in the banking sector.Footnote4 The “Portuguese” maximalist definition emphasized the importance of the institutional aspects of corruption (i.e. the distortion of laws and procedures that result in biased political will for a change). It was also shown that the interpretation of how power operates was central to the mismatch between what citizens and politicians defined as corruption in Portugal. Again, it is possible to search for those definitions in other countries and also inside public and private institutions—which can carry ideas of what corruption is that are disconnected from the social context in which they are part.

It must be highlighted that those definitions of need to be read with some caution. As said, corruption is a phenomenon that varies over time and according to culture (Lambsdorff, Citation2006) and, as such, its definition can change a lot depending on “when” and “where” we run the survey. Definitions presented here are valid only for Portugal and in the historical moment in which the EPOCA-FCT and the ETHICS-FFMS surveys were conducted. The interpretations of corruption cannot be directly expanded to other periods and other cultures/countries.

We believe that this visual word-oriented network analysis of the definition of corruption can enhance the quality of future surveys on corruption by providing definitions of corruption that are familiar to those being surveyed, boosting internal validity. Questions and items can use the most salient words to develop questionnaires that can produce knowledge on sectors and markets that are pointed as vulnerable and more inclined to be affected by corruption.

This analysis can also help the development of policies that need a more precise definition of corruption to orient strategies and effective action against corruption in sectors and economic areas that lack political will for corruption control. In Portugal, the financial sector emerged as relevant. Other sectors and/or institutions may appear as easy targets for corruption in other countries. Finally, we expect that this exercise (using words that are somehow associated with a specific concept) can be replicated in any other type of socio-political construct that is expected to vary significantly across cultures.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Luís de Sousa (ICS-ULisboa), who made this partnership to write the article possible. It would be impossible to finalize this article without his support and knowledge. Thanks also to Ilona Wysmułek (Polish Academy of Sciences), Marina Povitkina (Universitetet i Oslo), and Oksana Huss (Università di Bologna) for their precise and constructive comments on an earlier version of this article. Finally thanks to the reviewers for their important contribution, which made the article more coherent and robust.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no competing interests to declare relevant to this article’s content and are solely responsible for the contents and any errors and omissions that may be detected in the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Democracy can be used as an example here (Claassen et al., Citation2023; Pinto et al., Citation2012). Multiple aspects (universal suffrage, free and fair elections, the existence of freedoms and guarantees, when put together result in something bigger than the sum of each aspect. We name it democracy instead.

2 This response rate was not unusual and resembles those found in previous studies that approached politicians (Pereira et al., Citation2023, n. 10). In addition, it is worth mentioning that the topic “corruption” is a sensitive one and can be associated with lower response rates if compared to other less controversial topics (de Sousa, Citation2018).

3 The analysis of words was conducted in Portuguese. The words/expressions presented in all figures of this article kept the original spelling in Portuguese, as to avoid loss of meaning when translating into English. Only the most used words/expressions were translated to make it possible to develop the discussion of results in English.

4 A series of scandals involving the Portuguese banking sector have been reported in the media (Diário de Notícias, Citation2017; Expresso, Citation2015, Citation2020; Financial Times, Citation2023; RTP, Citation2018). “Revolving doors abound in the [Portuguese] financial sector, with a disproportionate share of regulators of that sector coming from, and moving back, to the industry” (Coroado & Magalhães, Citation2022), while there is only diffuse mention of it in the most recent National Anti-Corruption Strategy (Governo de Portugal, Citation2020).

References

- Aberbach, J. D., & Rockman, B. A. (2002). Conducting and coding elite interviews. Political Science & Politics, 35(04), 673–676. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096502001142

- Aguiar, T., Campos, M., Pinto, I. R., & Marques, J. M. (2017). Tolerance of effective ingroup deviants as a function of moral disengagement/Tolerancia de la disidencia efectiva de los miembros del endogrupo como función de la desconexión moral. Revista de Psicología Social, 32(3), 659–678. https://doi.org/10.1080/02134748.2017.1352169

- Allen, N., & Birch, S. (2012). On either side of a moat? Elite and mass attitudes towards right and wrong. European Journal of Political Research, 51(1), 89–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2011.01992.x

- Bauhr, M., & Charron, N. (2020). Do men and women perceive corruption differently? Gender differences in perception of need and greed corruption. Politics and Governance, 8(2), 92–102. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v8i2.2701

- Bauhr, M., & Charron, N. (2021). Will women executives reduce corruption? Marginalization and network inclusion. Comparative Political Studies, 54(7), 1292–1322. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414020970218

- Becquart-Leclercq, J. (1984). Paradoxes de la corruption politique. Pouvoirs, Revue Française d’études Constitutionnelles et Politiques, 31, 19–36.

- Blondel, V. D., Guillaume, J.-L., Lambiotte, R., & Lefebvre, E. (2008). Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment, 2008(10), P10008. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-5468/2008/10/P10008

- Borgatti, S. P., Mehra, A., Brass, D. J., & Labianca, G. (2009). Network analysis in the social sciences. Science, 323(5916), 892–895. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1165821

- Cartier-Bresson, J. (1992). Éléments d’analyse pour une économie de la corruption. Tiers-Monde, 33(131), 581–609. https://doi.org/10.3406/tiers.1992.4710

- Cartier-Bresson, J. (1997). Corruption networks, transaction security and illegal social exchange. Political Studies, 45(3), 463–476. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.00091

- Claassen, C., Ackermann, K., Bertsou, E., Borba, L., Carlin, R. E., Cavari, A., Dahlum, S., Gherghina, S., Hawkins, D., Lelkes, Y., Magalhães, P. C., Mattes, R., Meijers, M., Neundorf, A., Oross, D., Ozturk, A., Sarsfield, R., Self, D., Stanley, B., … Knoll, D. (2023). Conceptualizing and measuring support for democracy: A new approach. https://ssrn.com/abstract=4622645

- Coroado, S., & Magalhães, P. C. (2022). Rules or legacies? Industry and political revolving doors in regulators’ careers in Portugal. Governance, 36(3), 741–758. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12691

- de Sousa, L. (2008). ‘I don’t bribe, I just pull strings’: Assessing the fluidity of social representations of corruption in Portuguese Society. Perspectives on European Politics and Society, 9(1), 8–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/15705850701825402

- de Sousa, L. (2018). O estudo da corrupção através de métodos de inquérito: desafios e cuidados a ter. In I. R. Pinto & J. M. Marques (Eds.), Olhares sobre desvio e crime na sociedade portuguesa (pp. 65–83). Legis Editora/Mais Leituras.

- de Sousa, L., & Coroado, S. (2023). Ethics and integrity in politics: Perceptions, control, and impact (ETHICS), 2021. Arquivo Português de Informação Social, Lisboa. APIS0096. http://hdl.handle.net/10400.20/2116

- de Sousa, L., & Gouvêa Maciel, G. (2022). What ethical standards are expected in politics?. In L. de Sousa & S. Coroado (Eds.), Ethics and integrity in politics: Perceptions, control, and impact (pp. 24–50, 180–182). FFMS. https://www.ffms.pt/pt-pt/estudos/etica-e-integridade-na-politica

- de Sousa, L., Magalhães, P. C., & Clemente, F. (2022). Corrupção e Crise económica: percepções dos portugueses sobre corrupção [Policy Brief] (Vols. 1–2). Instituto de Ciências Sociais, Universidade de Lisboa.

- de Sousa, L., Pinto, I. R., Clemente, F., & Gouvêa Maciel, G. (2021). Using a three-stage focus group design to develop questionnaire items for a mass survey on corruption and austerity: A roadmap. Qualitative Research Journal, 21(3), 304–319. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRJ-09-2020-0110

- de Sousa, L., & Triães, J. (2009). Capital Social e Corrupção. In L. de Sousa (Ed.), Ética, Estado e Economia: Atitudes e Práticas dos Europeus (pp. 93–125). ICS Publicações.

- Diário de Notícias. (2017, May 1). Caso Berardo. Breve cronologia de uma investigação que soma 11 arguidos. https://www.dn.pt/sociedade/caso-berardo-breve-cronologia-de-uma-investigacao-que-soma-11-arguidos-14841509.html

- Doorenspleet, R. (2019). Democracy and corruption. In R. Doorenspleet (Ed.), Rethinking the value of democracy (pp. 165–200). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91656-9_5

- European Commission. (2022). Special Eurobarometer 523, Corruption. (https://data.europa.eu/doi/10<?sch-permit JATS-0034-007?>.2837/110098, Ed.). Directorate-General for Migration and Home Affairs. https://doi.org/10.2837/110098

- European Commission. (2023). Special Eurobarometer 534, Citizens’ attitudes towards corruption in the EU in 2023. Directorate-General for Migration and Home Affairs. https://doi.org/10.2837/5674

- Expresso. (2015, December 30). Oito anos de escândalos financeiros. https://expresso.pt/economia/2015-12-30-Oito-anos–de-escandalos-financeiros

- Expresso. (2020, June 12). Governo abre guerra a lei anti-Centeno. Nomeação para o Banco de Portugal na mão do Bloco. https://expresso.pt/politica/2020-06-12-Governo-abre-guerra-a-lei-anti-Centeno.-Nomeacao-para-o-Banco-de-Portugal-na-mao-do-Bloco

- Financial Times. (2023, November 13). Portugal’s central bank chief faces ethics review after being proposed as PM. https://www.ft.com/content/b1a58ef3-fe41-4ff7-a41e-6bd5f3064008

- Gouvêa Maciel, G., & de Sousa, L. (2018). Legal corruption and dissatisfaction with democracy in the European Union. Social Indicators Research, 140(2), 653–674. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1779-x

- Gouvêa Maciel, G., Magalhães, P. C., de Sousa, L., Pinto, I. R., & Clemente, F. (2022). A scoping review on perception-based definitions and measurements of corruption. Public Integrity, 26(1), 114–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/10999922.2022.2115235

- Governo de Portugal. (2020). Estratégia nacional de combate à corrupção 2020-2024. República Portuguesa. https://justica.gov.pt/Portals/0/Estrategia%20Nacional%20de%20Combate%20a%20Corrupcao%20-%20ENCC.pdf

- Heidenheimer, A. J. (1970). Political corruption: Readings in comparative analysis. Holt, Rinehart & Winston of Canada Ltd.

- ICAC. (2003). Community attitudes to corruption and the ICAC. NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption. https://www.icac.nsw.gov.au/ArticleDocuments/573/Community-attitudes-to-corruption-and-the-ICAC.pdf.aspx

- ICAC. (2006). Community attitudes to corruption and the ICAC: Report on the 2006 survey. NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption. https://www.icac.nsw.gov.au/ArticleDocuments/573/Community-attitudes-to-corruption-and-the-ICAC-Report-on-the-2006-survey.pdf.aspx

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística. (2014). Censos 2011, Portugal. https://censos.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpgid=censos2011_apresentacao&xpid=CENSOS

- ISSP Research Group. (2016). International Social Survey Programme: Citizenship II—ISSP 2014. In ZA6670 Data file Version 2.0.0. GESIS Data Archive. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.12590

- ISSP Research Group. (2018). International Social Survey Programme: Role of Government V—ISSP 2016. In. ZA6900 Data file Version 2.0.0. GESIS Data Archive. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.13052

- Jackson, D., & Köbis, N. C. (2018). Anti-corruption through a social norms lens. U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre, 7.

- Jacomy, M., Venturini, T., Heymann, S., & Bastian, M. (2014). ForceAtlas2, a continuous graph layout algorithm for handy network visualization designed for the Gephi software. PLoS One, 9(6), e98679. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0098679

- Jancsics, D. (2014). Interdisciplinary perspectives on corruption. Sociology Compass, 8(4), 358–372. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12146

- Kaufmann, D., & Vicente, P. C. (2011). Legal corruption. Economics & Politics, 23(2), 195–219. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0343.2010.00377.x

- Keudel, O., Grimes, M., & Huss, O. (2023). Political will for anti-corruption reform communicative pathways to collective action in Ukraine (QoG Working Paper Series, 3).

- Kubbe, I., & Engelbert, A. (Eds.) (2018). Corruption and norms: Why informal rules matter. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-66254-1

- Kubbe, I., & Merkle, O. (2022). Norms, gender and corruption: Understanding the nexus. Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781802205831

- Lambsdorff, J. G. (2006). Causes and consequences of corruption. In S. Rose-Ackerman (Ed.), International handbook on the economics of corruption (pp. 3–51). Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

- Leite, A. C., Pinto, I. R., & Marques, J. M. (2016). Do ambiguous normative ingroup members increase tolerance for deviants? Swiss Journal of Psychology, 75(1), 47–52. https://doi.org/10.1024/1421-0185/a000170

- Lessig, L. (2013). Foreword: ‘Institutional corruption’ defined. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 41(3), 553–555. https://doi.org/10.1111/jlme.12063

- Lindner, S. (2014). Literature review on social norms and corruption. U4 Helpdesk Answer. U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre, Chr. Michelsen Institute. https://www.u4.no/publications/literature-review-on-social-norms-and-corruption.pdf

- Magalhães, P. C., de Sousa, L. (2021). Inquérito à população portuguesa no âmbito do projecto EPOCA: Corrupção e crescimento económico, 2021. PTDC/CPO-CPO/28316/2017. Arquivo Português de Informação Social APIS0086. http://hdl.handle.net/10400.20/2106

- Megías, A., de Sousa, L., & Jiménez-Sánchez, F. (2023). Deontological and consequentialist ethics and attitudes towards corruption: A survey data analysis. Social Indicators Research, 170(2), 507–541. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-023-03199-2

- Mitchell, M. (2009). Complexity: A guided tour. Oxford University Press.

- Modesto, J. G., & Pilati, R. (2020). “Why are the corrupt, corrupt?”: The multilevel analytical model of corruption. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 23(e5), e5. https://doi.org/10.1017/SJP.2020.5

- Pereira, M. M., Coroado, S., de Sousa, L., & Magalhães, P. C. (2023). Politicians support (and voters reward) intra-party reforms to promote transparency. Party Politics. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/13540688231203528

- Pinto, A. C., C Magalhães, P., & de Sousa, L. (2012). Is the good polity attainable?—Measuring the quality of democracy. European Political Science, 11(4), 447–455. https://doi.org/10.1057/eps.2011.45

- Pozsgai-Alvarez, J. (2020). The abuse of entrusted power for private gain: Meaning, nature and theoretical evolution. Crime, Law and Social Change, 74(4), 433–455. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-020-09903-4

- Rothstein, B. (2014). What is the opposite of corruption? Third World Quarterly, 35(5), 737–752. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2014.921424

- RTP. (2018, October 15). João Rendeiro condenado a prisão. https://arquivos.rtp.pt/conteudos/joao-rendeiro-condenado-a-prisao/

- Thompson, D. F. (2018). Theories of institutional corruption. Annual Review of Political Science, 21(1), 495–513. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-120117-110316

- Transparency International. (2017). Global Corruption Barometer Core Questionnaire 2017. Global Corruption Barometer 9th Edition. https://files.transparencycdn.org/images/Global_Corruption_Barometer_Core_Questionnaire2017.pdf

- Truman, D. B. (1971). The governmental process: Political interests and public opinion. Alfred A. Knopf.

- Vis, B., & Stolwijk, S. (2021). Conducting quantitative studies with the participation of political elites: Best practices for designing the study and soliciting the participation of political elites. Quality & Quantity, 55(4), 1281–1317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-020-01052-z

- Wysmułek, I. (2019). Using public opinion surveys to evaluate corruption in Europe: Trends in the corruption items of 21 international survey projects, 1989–2017. Quality & Quantity, 53(5), 2589–2610. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-019-00873-x