ABSTRACT

‘Access for all’ is a recurring theme in tertiary education. In Aotearoa New Zealand improving access for underserved groups, including Indigenous Māori, is a priority to educational reforms. We undertook a realist evaluation of tertiary education sector participation rates across three regions formerly served by three separate industry training providers. Analysis of enrolment data across the regions reveals ‘educational deserts’ with limited access and low participation in several areas, despite longstanding policy rhetoric regarding equity of access for rural and Māori communities. Patterns are also observed between regions in the level of enrolments outside main population centers, which we argue relate to strategic decisions taken by providers influenced by funding settings. Five considerations arise for policy and leadership practice: (1) the impact of centralisation in creating ‘educational deserts’; (2) the relationship between funding models and an entity’s ability to deliver regionally; (3) the possible impact of international students on domestic students and host organisations; (4) the relationship between ‘belonging’ and tertiary education participation; and (5) an entity’s role in closing equity gaps. Current reforms must move beyond rhetoric and avoid overly centralised education and training provision. Effective policy and resourcing solutions are critical to address current inequities.

Introduction

Equity is increasingly framed as a moral issue, and universally accepted credence that all people are equal with equal rights to access chances in life. This includes equal access to publicly funded services, infrastructure, health, and education. The benefits of equitable access to education are supported by a very large literature demonstrating strong links between education and positive life outcomes (Hong et al. Citation2020; Mahoney Citation2014; Park Citation2014; Peercy and Svenson Citation2016). Persistent inequalities remain in many countries for inner urban, rural, remote, and socially disadvantaged communities and indigenous peoples (Hillman and Weichman Citation2016; Hillman Citation2016; Klasik et al. Citation2018; Mahoney Citation2014; Park et al. Citation2021). Addressing inequalities and providing equitable access to tertiary education has clear capacity to change lives, enhance longevity, and strengthen entire communities (Hong et al. Citation2020; Satherly Citation2021; Scott Citation2021; Theodore et al. Citation2018). In the New Zealand context, educational inequalities are well-recognised (Mayeda et al. Citation2022; Meehan et al. Citation2017; Theodore et al. Citation2018; Wikaire et al. Citation2016), for example, Level 4 certificate are linked with higher employment and income than high school qualifications. For example, men with level four qualifications have excellent rates of employment and higher than usual income – probably due to link of these qualifications with trades (Earle Citation2010), however, the spatial dimension to such advantage and the persistent inequalities in regional areas is underexplored. This gap, in the context of reforms to the vocational education sector, where 25 entities have merged into a unified national provider, form the impetus for this study.

Higher education in New Zealand

Historically there has been a range of different provider types within New Zealand’s tertiary education sector (Ministry of Education Citation2022a) including universities; institutes of technology and polytechnics (ITPs); wānanga (entities with educational models embedding Māori ways of learning and knowing)Footnote1; and private training establishments (PTEs). Industry-owned industry training organizations (ITOs) receive government funding for arranging workplace training and as such have also been part of the sector (Doyle et al. Citation2022; NZ Chambers of Commerce Citation2022). Each post-school education providers (including PTEs) is funded via the Tertiary Education Commission (TEC) and, with the exception of PTE’s, operate as Crown entities or subsidiaries (Ministry of Education Citation2022a; Public Service Commission Citation2022).

Prior to 1990, New Zealand’s education sector was centrally controlled and tightly regulated (Doyle et al. Citation2022; Smyth Citation2012). Significant changes occurred in the late 1980s including moves to a deregulated economy and shifts to a market approach in the governance, structure, and operations of government services with phased implementation over the ensuing decade (Doyle et al. Citation2022; James Citation1992; Smyth Citation2012). Controlled structures and inflexible funding models were blamed for situations whereby tertiary providers, particularly polytechnics, could not respond to market conditions or industry-specific local needs and underwent radical reform. The first sequence of reforms, enacted in the Education Act 1989 (New Zealand Government Citation1989 ) and implemented in a sequential fashion, included demand-driven funding based on the specific needs of regions; establishment of wānanga for delivery of education in a Māori context; provision for private providers (i.e. PTEs) to be funded on the same basis as public providers; provider autonomy over fee setting; competition for students; and, the ability for all providers to recruit and enroll international students in a full-cost recovery model. For ITPs, reforms also saw the introduction of new governance models with councils autonomously overseeing each provider at arm’s length from government. The new governance model was also applied to ITP’s, colleges of education and wānanga with traditional university councils modified to provide a common governance model across the sector. The intent expressed was for providers to better meet the needs of industry and more responsively service local communities, including Māori and Pasifika (Crawford Citation2016; Doyle et al. Citation2022; James Citation1992; Smyth Citation2012). Further reform over the next two decades focused on refining governance and funding arrangements. Funding caps were introduced in 1990, removed near the end of the decade and then re-introduced in 2005 with providers required to perform within designated funding arrangements and maintain organisational viability (Crawford Citation2016). The heavy free-market approach was further modified in 2000, involving development of national strategies and the establishment of a Tertiary Education Commission to give effect to national policy decisions (Crawford Citation2016). Notably, elements of the free market model were retained inasmuch as providers were required to demonstrate and maintain a sustainable financial position (Crawford Citation2016).

These later reforms aimed to ensure stronger accountability of providers to local community need (including Māori), and better alignment with regional industry requirements (James Citation1992; Smyth Citation2012). Central government provided guidance via publication of a ‘Māori Tertiary Education Framework’ which outlined expectations and educational best practices for delivery to Māori (Horomia and Maharey Citation2003). It is notable that in the past several decades, New Zealand government leaders and policy makers have placed a priority focus on Māori development and attempts to close the gap between Māori and non-Māori education participation and success (Māori Tertiary Reference Group Citation2003; Ministry of Education Citation2022b; New Zealand Government Citation2014). Some improvements are evident (Ryan Citation2022), however, despite the rhetoric regarding equity of access, ‘educational deserts’ (Hillman and Weichman Citation2016; Hillman Citation2016; Mayeda et al. Citation2022), or areas of limited tertiary education access and low participation, remain (Earle Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Meehan et al. Citation2017; Wikaire et al. Citation2016). Educational access is especially limited for Māori communities (McCelland Citation2006; Porta Citation2022; Ussher Citation2006), with Māori students in both regional of urban contexts less likely to pass first-year subjects and more at risk of completion than non-Māori students, with consistently lower grade point averages. Many Māori learners are first in their family to enroll in tertiary education, are more likely to have gaps in secondary school achievement and may be further challenged by socioeconomic disadvantage (Earle Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Mahoney Citation2014; Mayeda et al. Citation2022; Meehan et al. Citation2017; Wikaire et al. Citation2016). Additionally, Māori learners are more highly concentrated in rural communities and so face the geographical challenges of location and the known negative impact of travel distance on learners who travel for study (Brownie et al. Citation2023). Regional and local access to education, particularly vocational education, is of critical importance as 50% of school leavers are reported as beginning their tertiary study within 20 km of where they attended school with a third starting their tertiary education within 150 km of their school, while travelling further for university level study (Porta Citation2022).

RoVE – New Zealand reform of vocational education

Despite New Zealand’s history of recurrent reforms, education inequities have persisted with successive reports noting continued disparity in learning outcomes between Māori and non-Māori as well as areas of significant skills shortage (Huntington Citation2022; Mayeda et al. Citation2022; Meehan et al. Citation2017; Ryan Citation2022; Sherwin et al. Citation2017; Theodore et al. Citation2018; Wikaire et al. Citation2016). In August 2019, New Zealand’s Minister of Education announced further reform of the vocational education and training (VET) sector – ‘Reform of Vocational Education’ (RoVE) a major initiative of the Labour-led government (Hipkins Citation2019; Tertiary Education Union Citation2019). This included the merger of 16 ITPs and 9 ITOs into a single national provider, Te Pūkenga, (the New Zealand Institute of Skills and Technology), with a new unified funding model (implemented in early 2023) promising to address existing deficits and inequities and better alignment with industry (Huntington Citation2022; Tertiary Education Commission Citation2019, Citation2023; Tertiary Education Union Citation2019). Central tenets of the reforms include placing priority attention on industry connection and ensuring more equitable access and participation for ‘underserved learners’ – Māori, Pacific peoples, disabled people and people with low levels of previous education (Tertiary Education Commission Citation2019; Tertiary Education Union Citation2019). However, whether the allocations within the unified funding model cater sufficiently to support educational delivery into the regions remains to be seen.

The 2019 RoVE business case provided four operating options for the Government to consider, from continued regionalisation of provision to a highly centralised model (Ministry of Education Citation2019). Of note, establishment of a single national body includes elements of a return to centralized control that was not recommended by officials; however, the model has sought, at least in theory, to ensure that Te Pūkenga retains responsibility to develop local solutions in response to local needs. This expectation is set out in legislation:

To meet the needs of regions throughout New Zealand, Te Pūkenga – New Zealand Institute of Skills and Technology must:

(a) offer in each region a mix of education and training, including on-the-job, face-to-face, and distance delivery that is accessible to the learners of that region and meets the needs of its learners, industries, and communities (New Zealand Government Citation2020).

(b) operate in a manner that ensures its regional representatives are empowered to make decisions about delivery and operations that are informed by local relationships and to make decisions that meet the needs of their communities (New Zealand Government Citation2020).

Improving regional and ethnic equity of access, participation and outcomes, is a priority mandate within RoVE reforms (Tertiary Education Commission Citation2019; Tertiary Education Union Citation2019), however, there is a paucity of evaluative data to inform the current reform process, particularly various strategies developed and implemented by former, regionally-based tertiary education providers. This study is conceived as an evaluative inquiry, asking ‘what works?’ about differing strategies and approaches undertaken by previously autonomous entities may provide relevant insights for the reforming sector to address vexing issues of inequality in educational access and outcomes.

Study rationale and aim

This study explores historic patterns of tertiary education access and participation across three regions located in the central North Island of New Zealand: Hauraki – Waikato, Bay of Plenty – Waiariki and Hawkes’ Bay Tairāwhiti. Enrolments across all providers are examined, with specific attention focused on enrolments at the three former local ITPs: Waikato Institute of Technology (Wintec), Toi Ohomai Institute of Technology (Toi Ohomai), and the Eastern Institute of Technology (EIT). We interrogate relevant administrative data to identify the level of success or otherwise of providers in promoting participation across their regions, with the aim of enabling reflection on previous strategies and informing future policy formation, decision making around resource allocations and leadership action.

We consider enrolment data in various tertiary education settings: university, wānanga, ITPs and ITOs, and consider how differing strategies of providers may have influenced access and participation. A primary focus lies in considering how reforms in the sector, such as combination of providers into a single regional mega grouping may risk exacerbating rather than resolving inequities of access. We highlight ‘educational deserts’ as areas with limited access and low participation in tertiary education.

Method

A case study approach with ‘realist evaluation’ (Van Velle et al. Citation2022) frames this study. The objective of realist evaluation is to discover ‘what works for whom in what circumstances’, rather than merely assessing if something works. Culture and context are important rather than the strategy and/or intervention alone. Realist evaluations approach a topic or scenario by considering three criteria (Pickering Citation2021):

Context – we have considered the issue of place and culture in the three differing regional contexts in our study.

Mechanism/s – we have highlighted the different strategies and approaches implemented by each council and executive team.

Outcomes – we have accessed data to demonstrate the different outcomes evident within each region.

Realist evaluation is ‘method neutral’ in that it comfortably and unapologetically derives data from multiple sources (Pickering Citation2021; Van Velle et al. Citation2022). Harrison and Waller (Citation2017) posit that evaluation is a circular process from which gathered data raises questions which lead to further interrogation and honing of evaluative questions (Harrison and Waller Citation2017). Thus, the evaluative method adopted in this work is intended to provide insights and inform future operational and evaluative inquiry. Information has been drawn from multiple sources, including government policy documents, government legislation, annual reports, peer reviewed literature, and government datasets.

Data

Spatial enrolment data are drawn from New Zealand Ministry of Education datasets held in the Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI), a centralised research database administered by Statistics New Zealand (Social Investment Agency Citation2017; Stats New Zealand Citation2022b). Access to the IDI was granted to researchers in October 2020 (with a variation agreed in October 2021 to include tertiary education datasets). Written permission was obtained from Te Pūkenga to access enrolment data at the individual institution and campus level.

Ministry of Education Tertiary Education data which includes information about students enrolled in government funded post-secondary education organisations in New Zealand was used (Stats New Zealand Citation2022a). These include universities, wānanga, ITPs, and PTEs that received direct government allocation of Student Achievement Component (SAC) funding to 2021 and ITOs that received funding via the Industry Training Fund. Note that while ITPs and most functions of industry training organisations were bought together as Te Pūkenga – New Zealand Institute of Skills and Technology in April 2020, these organisations were still differentiated in the dataset.

The analysis includes enrolments at any time over a given calendar year in a qualification of greater than 0.03 equivalent full-time students (more than one week's duration). Given our primary interest lies in the total reach and impact of tertiary education we present headcounts of students (not EFTS). Ethnicity data is as recorded by the provider, with total response ethnicity used so that totals may sum to greater than the number of respondents (Education Counts Citation2022). International students are students without New Zealand/Australian citizenship or permanent residency; domestic students hold such citizenship or status. At the time of analysis, the tertiary education dataset used in this analysis included data current to the end of 2021.

Location

Analysis is based on intramural student enrolments recorded by individual education institutions in the geographic area approximating the Waikato, Bay-of Plenty – Waiariki and Hawke's Bay-Tairāwhiti Education Regions, as defined by the Ministry of Education (Ministry of Education Citation2022b).

These regions include enrolments at the University of Waikato (campuses in Hamilton and Tauranga), the former Wintec (main campus in Hamilton, and regional locations Thames, Otorohanga, and Te Kuiti), Toi Ohomai (formed from a merger of Bay of Plenty Polytechnic and Waiariki Institute of Technology in 2016 and with main campuses in Tauranga and Rotorua and secondary campuses in Tokoroa, Taupō, Ōpōtiki and Whakatane) and EIT (formed from a merger of the former EIT with Tairawhiti Polytechnic in 2011, and with main campuses in Gisborne and Napier and regional learning centers in Wairoa, Ruatoria, Waipukurau, Hastings and Maraenui). It also includes enrolments at the two wānanga with campuses in region: Te Whare Wānanga o Awanuiārangi (main campus in Whakatane), and Te Wānanga o Aotearoa, headquartered in Te Awamutu and with locations in each of the three regions. PTEs, which tend to be somewhat smaller, have a physical presence in many places across the three regions. Finally, ITO (work-based learning) data is included where the location of employment was in the region of interest (note that learners can participate in training in multiple locations in each year. They are counted in each location in which they appear).

Findings

Proportion of people participating in study

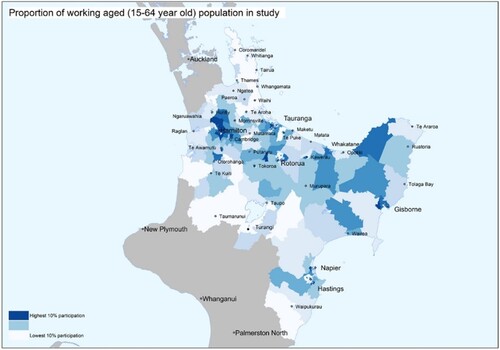

Assessing levels of access to tertiary education began by examining proportions of the working aged population who were engaged in study at the time of the most recent (2018) census. For clarity, the rate is the number of people engaged in full-time/part-time study (Stats New Zealand Citation2018), as a percentage of those aged between 15 and 64, calculated at the Statistical Area 2 (SA2) level.Footnote2 Rates across the study area are shown in .

Figure 1. Percent of working-age (15–64-year-old) population in full-time or part-time study, 2018 Census. Geographic boundaries (SA2) at 1 January 2018. Extracted from (Stats New Zealand Citation2023a).

Distributed into 10 quantiles (with each band representing ∼10% of the SA2 in the study area), darker hues represent a higher proportion of working-age residents engaged in study. A considerable range is observed, from fewer than 0.1 percent in sparsely populated SA2 covering rural or commercial areas, to over half of working age residents (51.6 percent) in the Greensboro SA2, which neighbours the University of Waikato campus in Hamilton (by way of comparison, nationally almost 15 percent of the working-age population was studying). It is unsurprising that there are higher rates of participation near where main university and ITP campuses are located, and lower in less populated areas – but note the important exception of relatively high participation rates in the lower populated East Coast areas incorporating Wairoa, Tologa Bay, and Ruatoria. The lowest rates of participation are observed in the Taumarunui and Thames-Coromandel areas – raising questions as to why these ‘educational deserts’ have occurred.

Tertiary enrolments by subsector

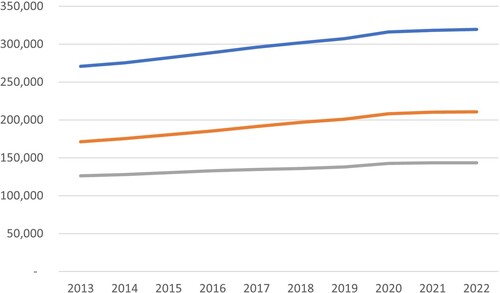

To assess access and participation, we undertook a detailed analysis of regional tertiary enrolments over time. For context, shows the official estimated working-age population for the three regions for the period 2012–2021 (per Statistics New Zealand) and the number of local school-leavers in each year. The total working age population grew in all three regions over the period. The total working age population is important because in 2020, 29.2% of full-time full-year domestic students and 66.5% of part-time full-year domestic students were over the age of 25 (Sin et al. Citation2022). Along with increases in the working-age population, the number of school leavers have remained steady (e.g. 12,248 across the study area in 2012 and 13,423 in 2020). Importantly, the growing working age population, and stable school leavers, suggests that all else being equal, enrolments in tertiary settings in these regions would not be expected to decline due to demographic effects of contraction in age cohorts which are a partial determinant of enrolments.

Figure 2. Working age (15–64-year-old) population, Waikato, Bay of Plenty–Waiariki, Hawke's Bay-Tairāwhiti regions, 2012–2022. Source: Statistics New Zealand, Subnational population estimates (RC, SA2), by age and sex, at 30 June 1996–2022. Extracted from NZ.Stat (Stats New Zealand Citation2023a).

Figure 3. School leavers by year, Waikato, Bay of Plenty–Waiariki, Hawke's Bay-Tairāwhiti regions, 2012–2022. Source: Ministry of Education, Time Series Data: School Leavers with Highest Attainment (2013–2023) (Education Counts Citation2023b)

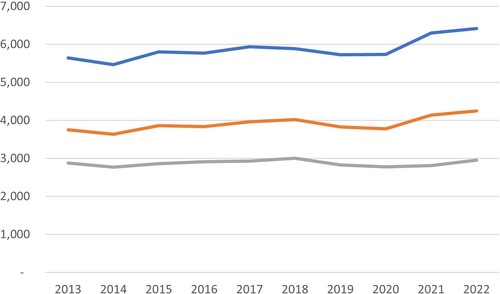

shows the total number of individual students enrolled in the various tertiary education or training subsectors (i.e. university, ITPs, wānanga, PTEs or industry training/ITOs) in the three regions, and nationally for context, from 2013 to 2022. Shown are students enrolled and studying intramurally (on-campus) at delivery sites located in each region for tertiary institutions, and for industry training learners, in locations of employment in each region. Separate charts are presented for total (overall), domestic, and Māori enrolments.

Figure 4. Tertiary student enrolments (headcount) by subsector, Waikato, Bay of Plenty – Waiariki and Hawke's Bay – Tairāwhiti regions and national (total New Zealand), 2012–2022. Students are counted in each sub-sector they enroll in, so the sum of the various sub-sectors may not add to the total. Study region is based on the delivery site of the courses that intramural students were enrolled in or the location of employment for industry training (ITO) learners. Students are counted in each region they enroll in, so the sum of the various regions may not add to the total. Source: Ministry of Education Provider based enrolment data (Education Counts Citation2023c); Ministry of Education Participation in industry training data (Education Counts Citation2023a).

For the three regions and nationally, workplace-based training (ITOs) and ITPs served broadly similar numbers of learners in the early part of the period, but in more recent years these have increasingly diverged in favour of workplace training, with the number of students enrolled in ITP settings declining from around 2017 onwards. This national trend is amplified in Waikato and Bay of Plenty-Waiariki, though ITP enrolments remained stable in Hawkes Bay-Tairāwhiti (where almost all students are domestic and there is no university presence). A broad increase in enrolments across tertiary education subsectors is apparent in 2020/2021, reflecting the initial impact of COVID19 and associated lockdowns on jobs and the economy. While in most subsectors these increases were not sustained in 2022 as the economy recovered, ITO enrolments have continued to grow since 2020, likely at least in part to illustrate the success of the government’s Apprenticeship Boost policy, which provided support for employers to retain and take on new apprentices as the economy recovered from the impacts of COVID.

At the regional level there are some patterns worth noting: in the Waikato, university enrolments are comparable, exceeding in some years those of ITPs, while for Māori, wānanga/PTEs play a larger role. In the Bay of Plenty, enrolments in wānanga sometimes exceeded those in ITPs or ITOs. University, PTE and to a slightly lesser extent wānanga enrolments were stable over the period. In the regions of interest, University enrolments are concentrated in the Waikato where the University of Waikato’s main Hamilton campus is located, with significantly fewer, though growing, enrolments in the Bay of Plenty (where the University maintains a campus outpost at Tauranga) and nil in Hawke’s Bay – Tairāwhiti, where there is no university presence.

It should be mentioned in this context that universities are a particular kind of tertiary education provider that differ from others in their range of activities (especially a commitment to research and creation of knowledge) and, in most cases, their scale (Norton Citation2023). They have the effect of drawing people at younger and working ages to metropolitan centers where university campuses are located (Porta Citation2022). McCelland (Citation2006) notes that ‘internal migration data shows a relationship between population decline in areas that do not contain a university and population increase in areas that do contain a university’ (p. 27), with non-university areas experiencing large net outflows in the 15-to-19 and 20-to-24-year age groups, while university cities experience large net migration inflows in these age groups (McCelland Citation2006). The impact on localities where these campuses are located is evidenced in the very high numbers of people studying in SA2 near campuses shown in .

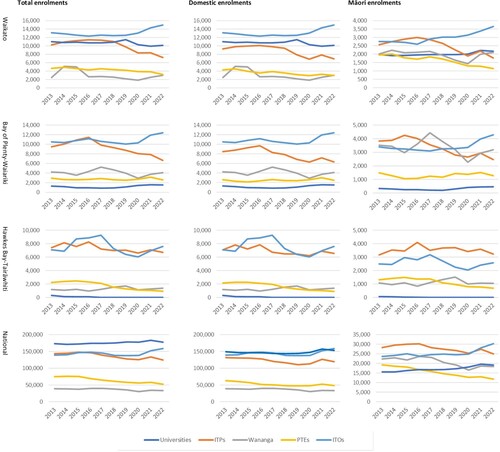

Regional campus enrolments

Given the explicit legislative requirement of this sector ‘to be responsive to and to meet the needs of the regions, their learners, industries, employers, and communities’ (New Zealand Government Citation2020, s.315c) and the focus of recent reforms, it is instructive to examine enrolments in the ‘regional’ campuses of the 3 local ITPs: Wintec, Toi Ohomai and EIT. ‘Regional’ or ‘branch’ campuses are those located away from the primary, city campuses of these institutions. They are intended to cater for learners who cannot travel long distances for study due to work, family or financial limitations (Watt and Gardiner Citation2016).

show the number of enrolments in courses of more than one week duration in the regional campus locations of Wintec, Toi Ohomai and EIT, respectively. As shown in , the number of students enrolled in Wintec regional campuses has declined considerably over the period in which data is available (2005–2019). Enrolments in Te Kuiti, which exceeded 1,500 in 2008, declined to 9 in 2016 following which the campus was closed. A campus opened in Otorohanga in 2011 but annual enrolments have never exceeded 200. Enrolments in Thames, ∼1,400 in 2008, declined until 2011 and since then have numbred around 200–400.

Table 1. Wintec regional campus enrolments (headcount), 2003–2020.

Table 2. Toi Ohomai regional campus enrolments (headcount), 2014–2020.

Table 3. EIT regional campus enrolments (headcount), 2005–2020.

Toi Ohomai regional campus data, shown in , is only available from 2014. Enrolments have declined at the largest regional campus (Whakatane) and in Ōpōtiki, the smallest of the delivery sites, but are stable in Tokoroa and Taupō.

Enrolments at Eastern Institute of Technology regional learning centers, shown in , were steady or grew over the period 2005–2020. Ruatoria, some 2 h by car from the Gisborne campus, had its first enrolments in 2015, increasing every year to 400 in 2020. Enrolments in Hastings (itself a city) have been large, over 1000 in some years. Enrolments in Wairoa have been around 300 for some time, and Waipukurau enrolments are similarly steady, though somewhat higher in number. Maraenui is notable as an EIT regional learning center established in 2007 – it is in a lower socio-economic suburb of Napier and was established explicitly to bring learning into the community. Recent enrolments have been around 200.

Noting that Rotorua was the city in the three regions with the lowest rates of study participation in 2018 (), we also examined in closer detail enrolments over time at the local Toi Ohomai campus. Toi Ohomai was formed from a 2016 merger of Waiariki Institute of Technology (with its main campus in Rotorua) with the Tauranga-centered Bay of Plenty Polytechnic. shows the number of enrolments by selected student types at Waiariki – Toi Ohomai Rotorua campuses between 2008 and 2020. Notably, the number of domestic enrolments consistently declined from 2016, coinciding with a significant increase in international enrolments.

Table 4. Waiariki – Toi Ohomai Rotorua headcount enrolments by student type, 2008–2020.

Discussion

Tertiary education is delivered within a complex system of intersecting and ever changing demographic, economic, cultural, financial, and spatial factors (Jacobson et al. Citation2019). Educational providers deal with many complex issues which cannot be addressed with large scale, one-size fits all approaches. The Te Pūkenga charter includes requirements to provide for the diversity of regional need, explicitly stating that the entity ‘must’ offer a mix of ‘accessible’ industry and community connected educational opportunities in each region (New Zealand Government Citation2020). Te Pūkenga has adopted a regional operating structure but this includes four regions only (versus the previous sixteen ITPs and nine ITO’s) through which the merged national provider will engage with industry, employers, and communities (Te Pūkenga Citation2022). The extent of local input and autonomy of funding or delivery which will be possible across each of the four mega-regions remains unclear. Further, the Te Pūkenga regional boundaries do not necessarily align with either tribal or Māori electoral boundaries, raising concerns relating to Māori consultation and engagement across and within regions.

Implementation of the 1987–1989 reforms and the Education Act 1989 (James Citation1992; New Zealand Government, Citation1989) gave providers arm’s-length autonomy to diversify and more flexibly respond to industry and community need. One strength of these reforms lay in recognising that tertiary education is delivered in complex contexts in which one-size-fits-all solutions do not adequately reflect regional diversity and complexity and in granting autonomy for providers to develop, implement and evaluate within an educational ‘system which learns’ (Crawford Citation2016; James Citation1992; Smyth Citation2012). It was expected that different strategies would be adopted by the councils governing each entity as they responded to local industry and identified specific, cultural, and socioeconomic need within their regions. Per the realist evaluation method, where specific contexts and mechanisms are emphasised, it is worth considering local drivers for these enrolment trends.

Eastern Institute of Technology

From January 2011, EIT Hawke’s Bay merged with Tairāwhiti Polytechnic and became EIT, covering both Hawke’s Bay and Tairāwhiti (Eastern Insitute of Technology Citation2011). These regions are largely rural in nature, characterised by significant Māori populations and face challenges in respect to remotely located communities and (in some areas) socioeconomic deprivation. From the outset, EIT focused its mission on addressing these challenges, particularly those of educational accessibility, learner achievement, industry connectivity and the well-being of whānau and communities. Addressing equity issues for Māori was consistently noted as top priority for the organisation (Eastern Institute of Technology Citation2022). EIT leadership pursued a strategy of ‘growth into the region’, taking learning to the people via a network of regional learning centers, outreach education services and Marae-based delivery. Courses were delivered at all levels, i.e. NZQA levels 1–9 with a broad range of industry connected offerings at Certificate Level 2 and Level 3. Often a key limitation on participation became the number of seats in a mini-van as EIT provided transportation to support the participation of students at remote learning locations and Marae-based activities (Eastern Institute of Technology Citation2022).

Although the geographically-blind funding model of the sector did not adequately support the higher costs of regional delivery, EIT purposefully established an Auckland-based international graduate school to provide funding to support implementation of its ‘growth into the region’ strategy (Eastern Institute of Technology Citation2022). Profits from international enrolments provided funding streams to invest in the distributed educational model implemented across the two regions. shows significant participation in rurally remote areas. The relative success of this model is apparent, with enrolments continuing to grow over the study period (see ). These are impressive outcomes in respect to government expectations of service to the region and in addressing issues of access and equity for underserved learners.

Waikato Institute of Technology

The approach taken by Wintec was very different. Wintec has retreated from its regional learning centers (see ) in favour of a growth strategy focused on centralising domestic enrolments and building infrastructure primarily within its two Hamilton city campuses along with parallel intent to significantly increase its international presence (Waikato Institute of Technology Citation2016). Aspirations of national expansion included an explicit intent to be the leading responder to national skills shortages in engineering, health, and ICT via recruitment outside of the entities’ geographic boundaries and use of blended delivery models. Internationally, Wintec’s strategy included moves to expand its presence in the Middle East, China and the Pacific and partnerships with providers in India, China, and Southeast Asia. A purposefully structured market portfolio diversified the student cohort to include learners from more than fifty offshore nations (Waikato Institute of Technology Citation2016). Implementation of this strategy saw enrolments plummet in the regional outposts (see ). Wintec reports that approximately 40% of the region’s population lives outside of Hamilton – but that enrolments in the institution’s regional centers have continued to decline and are now only ‘provided in pockets’ on an ‘ad hoc’ basis mostly ‘short-term in nature’ (Waikato Institute of Technology Citation2021). Arguably, the areas with low tertiary education participation (‘educational deserts’) across the Waikato region, particularly the Taumarunui and Thames-Coromandel areas, are the outcome of Wintec’s deliberate strategic approach, which do not appear to have well-served the government’s stated sector aims and expectations of equity of access for regional communities, particularly Māori.

The centralist approach of Wintec appears to be longstanding in nature. A 2004 study commissioned by the Department of Labour into the ‘Future of Work’, explored the aspirations of Māori students aged 15 years and over from the northern Waikato and Thames-Coromandel region. Participating students stated that there appeared to be no providers in their region who could meet their expectations for tertiary education and that they had no option other than moving away to a large city or town if they wanted to undertake post school education and training (Steedman Citation2004). The sustained, multi-year application of a centralist strategy is perhaps unsurprising given the 16-year 6-month tenure of the entity’s former CEO (Waikato Business News Citation2019). This proffers insight into the link between organisational leadership and the implementation, or otherwise, of intended government policy.

Toi Ohomai Institute of Technology

Toi Ohomai formed following the 2016 merger of Waiariki and Bay of Plenty Polytechnics. In a similar manner to EIT, it focused its mission and priorities on regional engagement and delivery and in addressing issues of Māori participation and success in tertiary education. The strategy drew international students to help fund a dispersed delivery model (Toi Ohomai Institute of Technology Citation2022). Toi Ohomai’s strategy was monitored via clearly set and achieved targets for regional learners (Toi Ohomai Institute of Technology Citation2022) with significant progress across five campuses and 20 delivery sites. Outreach delivery shows considerable success, such as in the sparsely populated area north of Ōpōtiki in which specific horticultural related courses were delivered. Though there are evident successes in regional reach, a concerning decline is evident at the Mokoia Campus in Rotorua (see ). The head count of domestic enrolments at this campus dropped by 955 in the twelve-year period from 2008 to 2012 while international enrolments rose by 868 in the same period. In a similar manner to EIT, Toi Ohomai needed to raise additional funds to support its distributed educational delivery model. Their strategy involved large scale recruitment of foreign students from India to provide income to support wider regional engagement including development of a Tokoroa satellite campus. While successful in funding regional delivery, given the coinciding drop in domestic enrolments it is possible that this strategy had a negative impact on the number of domestic students enrolled at this campus. This speculative connection requires further research.

Reflections on findings

Conclusions can be drawn, and lessons learned from the different strategies implemented by the three entities in this study. Previous reforms allowed providers the freedom to develop, implement and evaluate different approaches within an educational ‘system which learns’ (Crawford Citation2016; James Citation1992; Smyth Citation2012). However, little if any, evaluative research has considered the impact and effectiveness of the diverse strategies subsequently implemented. In attempting to do so for these regions, four key factors become apparent: (1) the adverse impact of centralisation in creating ‘educational deserts’; (2) the relationship between central funding models and an entity’s ability to deliver into a region; (3) the yet to be explored impact of international students on domestic students and host organizations; (and the relationship between ‘belonging’ and tertiary education participation); and (4) the role of an entity in closing equity gaps. Each issue is worthy of further discussion.

Centralisation versus regional/local delivery

The most significant contrast exists in the patterns of enrolment participation in the geographies served by Wintec versus EIT (see ). All providers were mandated to deliver to priorities within the government’s tertiary education strategy (New Zealand Government Citation2014) and Māori tertiary education framework (Horomia and Maharey Citation2003) which direct providers to focus attention on meeting the diverse needs of their region. However, Wintec’s delivery strategy purposefully retreated to its main campuses with a focus on centralised infrastructure and establishing a national and international profile (Waikato Institute of Technology Citation2016). In contrast, EIT strategically focused on meeting the needs of the region, connecting with communities and prioritised improved access and equitable outcomes for Māori (Eastern Institute of Technology Citation2022). A similar regionally focused strategy was implemented by Toi Ohomai.

Educational deserts pose serious threats to educational participation and indigenous learning (Brownie et al. Citation2023; Hillman and Weichman Citation2016; Hillman Citation2016; Klasik et al. Citation2018). Reversal of inequity requires educational leaders to ensure that matters of geography have a central role in informing strategic conversations and decision. Inadequate consideration of geography or ‘place of learning’ reduces espoused commitments to diversity and equity as simply a mirage (Hillman Citation2019; Citation2016). The current RoVE reforms include elements indicative of a return to a centralised tertiary education system whereby a centralised body will govern, set operational policy and oversee four ‘mega’ regions (Te Pūkenga Citation2022). While Te Pūkenga is unequivocally required to meet regional needs and support an empowered decision making model (New Zealand Government Citation2020; Ryan Citation2023), the mechanisms by which this will be achieved remain unclear.

Funding tertiary education

The Education Act 1989 (New Zealand Government Citation1989) aimed to give tertiary education providers freedom and autonomy to make operational decisions (Minister of Education Citation2019). But reforms introduced a funding model whereby core funding was sufficient for basic costs only, with financial viability arguably dependent upon providers securing additional income outside of government sources. Providers were granted autonomy to increase fees for domestic students and recruit full fee-paying international students (Doyle et al. Citation2022; Huntington Citation2022; Smyth Citation2012). Each of the ITP entities in this study responded differently, particularly in respect to the sourcing of supplemental revenue via full fee-paying international students.

While both EIT and Toi Ohomai engaged in significant international recruitment activities to enable regional responsiveness to localised community need, EIT supplemented its on-campus international student provision in Hawke’s Bay with strategic international activities in Auckland i.e. well outside of its region (Eastern Insitute of Technology Citation2022) and offshore via a joint venture in China whereas Toi Ohomai undertook large-scale international enrolment at its Mokoia Campus, which has subsequently seen an unexplained decline in domestic enrolments, particularly Māori (Toi Ohomai Institute of Technology Citation2022). The specific reasons for the decline in domestic enrolments on the Mokoia campus are uncertain and requires further research. Wintec was equally active in recruiting international students centralising these enrolments in its major city campus in Hamilton, with the funding used to add to supplement core funding to build infrastructure and expand offshore campuses and activities (Waikato Institute of Technology Citation2016, Citation2021). The outcome of Wintec’s decision to increase international presence and centralise domestic operations raises questions about the alignment of this strategy with expectations in government strategy for provision into the region and equality of access for Māori communities and regionally dispersed learners (Horomia and Maharey Citation2003; New Zealand Government Citation2014).

The funding model is based on the number of students in a class rather than the actual costs of delivery, with a dispersed educational delivery model entailing smaller class sizes. Regional delivery involves higher costs than delivery on a large urban campus (OECD Citation2021). Simply put, it costs more to teach regional students than city-based students. Toi Ohomai’s commitment to regional delivery aligns with a ‘double negative impact on delivery margins’ because of lower average class size and higher costs (Toi Ohomai Institute of Technology Citation2022). While detailed discussion regarding tertiary education funding models is outside the scope of this paper, it is clear from our findings that a core funding model based on numbers of students in a class rather than the real cost of delivery adversely impacts the capacity of providers to effectively serve regional areas. While the new unified funding model for VET does have a ‘mode of delivery’ weighting, we would question whether these weightings provide sufficient drivers for regional engagement and delivery in an increasingly centralised system.

The impact of international students

While international income has been pivotal in enabling and subsidising the strategies of each of the three ITPs considered in this paper, the real impacts do seem to be underexplored. At around the time international student numbers began to significantly increase in New Zealand, the Ministry of Education commissioned a report entitled ‘The impact of international students on domestic students and host institutions’ (Ward Citation2001). This considered the potential cultural, social, and educational impact of international students on domestic students and their host educational entities. Ward (Citation2001) emphasised the paucity of information available and recommended priority be given to further research (Ward Citation2001), however, twenty years on, little further official inquiry seems to have been undertaken. Given the significant drop in domestic enrolments occurring alongside the increasing international enrolments at Toi Ohomai’s Rotorua campuses (see ) and the widespread educational deserts across Wintec’s jurisdiction (see ), this remains an important area for further inquiry.

A strong sense of belonging has been shown to improve motivation, well-being and success rates in education (Suhlmann et al. Citation2018). A 2017 report of the New Zealand Productivity Commission regarding ‘New Models of Tertiary Education’ highlighted that sense of belonging and collective cultural identity is particularly important for Māori and Pasifika learners (Sherwin et al. Citation2017), see also (Berryman and Eley Citation2019; Highfield and Webber Citation2021). One New Zealand-based study conducted with students in a business school found student-to-student interactions primarily occur between students in the same ethnic group, wherein students reported the greatest levels of comfort and belonging (Brown and Daly Citation2004). It is possible that the rapid influx of international students at Toi Ohomai’s Rotorua campuses may have disrupted an otherwise successful organisational strategy by disturbing the feeling of belonging and cultural identity among local students, particularly Māori. The authors found no particular research in this field but did note research in a related field, specifically, the impact of large migrant cohorts on the educational attainment and retention of domestic (described as native) students in primary and secondary school settings in various countries. A study in Chile (Contreras and Gallardo Citation2020) another in Denmark (Jensen and Rasmussen Citation2011) and another in the USA (Betts and Fairlie Citation2003) report various unintended impacts on native (domestic) students attainment and retention following mass migration into a classroom or school. In an IZA report, Jensen (Citation2015) provides a summary of global evidence suggesting that high concentrations of immigration in the classroom sometimes harms the educational outcomes of domestic (native) students and may impact the retention of domestic learners (Jensen Citation2015). More study is needed to better understand the impact of higher proportions of international students in specifically tertiary education contexts. This will enable appropriate support to maximise belonging, retention, and favourable outcomes for all learners (domestic and international).

Closing the equity gap

Morris and Jacobi (Citation2022) assert that issues of educational access and equity are multi-causal in origin and it takes the purposeful efforts and interventions of the tertiary education entity to close equity gaps (Morris and Jacobi Citation2022). Interventions are needed at regional, local and entity specific levels as demonstrated within the strategic priorities and operational plans of EIT and Toi Ohomai and include operational action such as multi-site delivery into the region, transport provision, locally accessible academic support, culturally appropriate pastoral support and more. Authentic demonstration of culturally appropriate leadership was a high priority for both EIT and Toi Ohomai. Both entities placed equity issues as central at corporate governance and senior executive level, profiling work and student success in regional contexts (Eastern Institute of Technology Citation2022; Toi Ohomai Institute of Technology Citation2022). An example of the commitment to these values is seen in how Toi Ohomai worked closely with Māori iwi of the region to design a Tiriti Partnership Model, culminating in the signing of a New Zealand-first Mana Ōrite Tiriti relationship agreement in 2018. This agreement outlined the framework, objectives, principles, expectations, and protocols for a relationship between Te Kāhui Mātauranga (senior Māori leaders of the region) and Toi Ohomai. In demonstration of the authenticity of relationship, Te Kāhui Mātauranga conducted (and submitted to the Toi Ohomai board) an annual assessment of the performance of the Toi Ohomai Chief Executive (Toi Ohomai Institute of Technology Citation2022).

EIT and Toi Ohomai resourced and implemented a range of culturally attuned strategies including:

Readily accessible student support at regional learning centers managed by staff familiar with the hinterland, locally informed, well-versed in tikanga (traditional Māori customs and values) and strongly connected to each entity’s Māori and Pacific learning support units.

Tikanga-based delivery on location with cohorts with whom students were comfortable and familiar – in familiar surroundings such as Marae, local farms, and community venues and halls – a strategy aligned with the known benefits of ‘belonging’ in improving student outcomes (Berryman and Eley Citation2019; Suhlmann et al. Citation2018).

Te Taupānga App, an online Māori software platform produced by Toi Ohomai. An educational resource to help staff, students, and wider community to interact in Te Ao Māori.

Local staff wherever possible and all staff external to the locality/region provided with cultural training and development support prior to local delivery.

Ultimately, strategies of EIT and Toi Ohomai involved very active and authentic engagement with iwi and industry leaders and communities. This was key to achieving equity of access and participation at both the regional and local level.

Limitations

While our focus on specific regions/institutions allows for a more detailed analysis than possible at a wider scale, the limitations of this study include that national factors may be obscured by our focus on the Central North Island. While we have included important contextual information including the working-age population and number of school leavers in each region, demand in the ITP and ITO sector is ‘highly counter-cyclical, driven by unemployment’ (Minister of Education Citation2019). Over the core 2013–2022 study period official unemployment rates were low and on a downward trend. Future research in this area should take into greater account the impact of local economic conditions on enrolment rates. In addition, the Ministry of Education datasets used in this study (though not the census data shown in ) exclude distance learners studying extramurally with providers outside the region. The largest providers of distance learning in New Zealand include Massey University in the university sector and Open Polytechnic and SIT2LRN (Southern Institute of Technology) in the ITP sector. We acknowledge the important role that this type of provision plays in ensuring access to tertiary education across the country (though often to a very different type of learner than intramural settings).

Conclusions

A learning system is one in which implemented strategy is continually monitored and evaluated and in which locally relevant information is available as an input to future decision making (Harrison and Waller Citation2017; Sherwin et al. Citation2017; Sydner Citation2014) – a premise on which the realist evaluation approach of this study is based and re which there is limited earlier evaluation. Findings highlight the two-fold benefit of the arms-length autonomy previously granted to educational providers. In the first instance it provided room for providers to respond to the needs of local communities and industry more innovatively and flexibly. Second, it provided an opportunity for various approaches to be reviewed and evaluated over time and for lessons to be drawn to inform future strategy development. Key lessons from this study illustrate the adverse impact of local centralisation versus the positive impact of strategies with ‘growth into the region’ and priority on equitable and accessible educational delivery. Lessons can also be drawn in respect to a funding model which requires providers to rely heavily on international enrolments. A conundrum is posed by reliance on funding from international students to fund delivery into rural and remote locations versus the (unexplored) potential impact that significant numbers of international students have on domestic students.

As New Zealand moves to dismantle the Te Pūkenga single national provider model of unified ITP and ITO provision and returns to regional provision, lessons arise from these regional profiles and illustrate that a simple return to regional provision does not guarantee better outcomes. Rigorous consideration must be given to the strategic, operational policy informing the action of reconstituted regional entities, particularly the appointment of local, high-quality, governance committed to local requirements. As this regional case study has demonstrated, successful outcomes require clear governance, competent leadership, and regular monitoring. Our results indicate that the impact of significant differences in the strategic approaches between regional institutions is underappreciated.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements and thanks are given to Te Pūkenga regional CEO’s Dr Leon de Wet Fourie and Mr Chris Collins for their insights regarding regionally developed and implemented strategy and their expert peer review of this manuscript prior to submission for publication.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Wānanga, unique to the New Zealand context, are defined in the Education and Training Act 2020 as institutions that are “characterized by teaching and research that maintains, advances, and disseminates knowledge and develops intellectual independence, and assists the application of knowledge regarding āhuatanga Māori (Māori tradition) according to tikanga Māori (Māori custom).”

2 SA2 are geographic areas, typically suburbs in cities and rural settlements with the surrounding area, with varying populations of up to approximately 4,000 people Stats New Zealand (Citation2023b). Statistical Area 2 2023 (generalised) GIS. Stats New Zealand. https://datafinder.stats.govt.nz/layer/111227-statistical-area-2-2023-generalised/.

References

- Berryman M, Eley E. 2019. Student belonging: critical relationships and responsibilities. International Journal of Inclusive Education. 23(9):985–1001. doi:10.1080/13603116.2019.1602365.

- Betts JR, Fairlie RW. 2003. Does immigration induce ‘native flight’ from public schools into private schools? Journal of Public Economics. 87(5):987–1012. doi:10.1016/S0047-2727(01)00164-5.

- Brown JC, Daly AJ. 2004. Exploring the interactions and attitudes of international and domestic students in a New Zealand tertiary institution (Business Education, Issue). https://eprints.utas.edu.au/6733/1/Hawaii_Justine.pdf.

- Brownie S, Yan A-R, Broman P, Comer L, Blanchard D. 2023. Geographic location of students and course choice, completion, and achievement in higher education: a scoping review. Equity in Education & Society. doi:10.1177/27526461231200280.

- Contreras D, Gallardo S. 2020. The effects of mass migration on the academic performance of native students: evidence from Chile. Economics of Education Review. 91:1–25. doi:10.18235/0002732.

- Crawford R. 2016. New Zealand Productivity Commission research note: history of tertiary education reforms in New Zealand. https://www.productivity.govt.nz/assets/Documents/65759a16ed/History-of-tertiary-education-reforms.pdf.

- Doyle J, Chan S, Hale M. 2022. The evolution of NZ institutes of technology and polytechnics. In: Chan S, Huntington N, editors. Reshaping vocational education and training in Aotearoa New Zealand. SpringerLink.

- Earle D. 2010. Benefits of tertiary certificates and diplomas: exploring economic and social outcomes. https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/76494/Benefits-of-certs-and-dips-17052010.pdf.

- Earle D. 2018a. Factors associated with achievement in tertiary education up to age 20. Ministry of Education. https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/187939/Achievement-report-for-publication.pdf.

- Earle D. 2018b. Factors associated with participation in tertiary education by age 20. Ministry of Education. https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/187941/Participation-report-version-for-publication-.pdf.

- Eastern Insitute of Technology. 2011. Merger process continues for EIT. https://www.eit.ac.nz/2012/01/merger-process-continues-for-eit-2/.

- Eastern Insitute of Technology. 2022. EIT | Te Pūkenga Graduate School, Auckland Campus. https://www.eit.ac.nz/campus/auckland/.

- Eastern Institute of Technology. 2022. Annual reports. https://www.eit.ac.nz/about/corporate-information/annual-reports/.

- Education Counts. 2022. Ethnic group codes. Ministry of Education. https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/data-services/code-sets-and-classifications/ethnic_group_codes.

- Education Counts. 2023a. New Zealand's workplace-based learners: an overview of industry training and other workplace-based trends for the year ended December 2021. Education Counts. https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/statistics/new-zealands-workplace-based-learners.

- Education Counts. 2023b. School leaver's attainment. Education Counts. https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/statistics/school-leavers.

- Education Counts. 2023c. Tertiary participation: participation in tertiary education in New Zealand. Education Counts. https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/statistics/tertiary-participation.

- Harrison N, Waller R. 2017. Evaluating outreach activities: overcoming challenges through a realist ‘small steps’ approach. Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education. 21:81–87. doi:10.1080/13603108.2016.1256353.

- Highfield C, Webber M. 2021. Mana Ūkaipō: Māori student connection, belonging and engagement at school. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies. 56(2):145–164. doi:10.1007/s40841-021-00226-z.

- Hillman N. 2019. Place matters: a closer look at education deserts. Third Way. https://www.thirdway.org/report/place-matters-a-closer-look-at-education-deserts.

- Hillman N, Weichman T. 2016. Education deserts: the continued significant of ‘place’ in the 21st century (Voices in the Field Issue).

- Hillman NW. 2016. Geography of college opportunity. American Educational Research Journal. 53(4):987–1021. doi:10.3102/0002831216653204.

- Hipkins C. 2019. A new dawn for works skills and training. https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/new-dawn-work-skills-and-training.

- Hong K, Savelyez PA, Tan KTK. 2020. Understanding the mechanisms linking college education with longevity (Discussion Paper Series Issue).

- Horomia P, Maharey S. 2003. Maori tertiary education framework. New Zealand Government. https://www.beehive.govt.nz/sites/default/files/Maori%20Tertiary%20Education%20Framework.pdf.

- Huntington N. 2022. The reform of vocational education 2: looking to the future. In: Chan S, Huntington N, editors. Reshaping vocational education and training in Aotearoa New Zealand. Springer; p. 73–93.

- Jacobson MJ, Levin JA, Kapur M. 2019. Education as a complex system: conceptual and methodological implications. Educational Researcher. 48(2):112–119. doi:10.3102/0013189X19826958.

- James C. 1992. New territory: the transformation of New Zealand, 1984–92. Bridget Williams Books Limited.

- Jensen P. 2015. Immigrants in the classroom and effects on native children.

- Jensen P, Rasmussen AW. 2011. The effect of immigrant concentration in schools on native and immigrant children's reading and math skills. Economics of Education Review. 30(6):1503–1515. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2011.08.002.

- Klasik D, Blagg K, Pekor Z. 2018. Out of the education desert: how limited local college options are associated with inequity in postsecondary opportunities. Social Sciences. 7(9). doi:10.3390/socsci7090165.

- Mahoney P. 2014. The outcomes of tertiary education for Māori graduates: what Māori graduates earn and do after their tertiary education. Ministry of Education. https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/147243/The-outcomes-of-tertiary-education-for-Maori-graduates.pdf.

- Māori Tertiary Reference Group. 2003. Māori tertiary education framework; a report by the Māori Tertiary Reference Group. Ministry of Education Wellington New Zealand. https://www.beehive.govt.nz/sites/default/files/Maori%20Tertiary%20Education%20Framework.pdf.

- Mayeda D, France A, Pukepuke T, Cowie L, Chetty M. 2022. Colonial disparities in higher education: explaining racial inequality for Māori youth in Aotearoa New Zealand. Social Policy and Society. 21(1):80–92. doi:10.1017/S1474746421000464.

- McCelland J. 2006. A changing population and the New Zealand tertiary education sector. Ministry of Education. https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/178621/A-changing-population-and-the-NZ-tertiary-education-sector.pdf.

- Meehan L, Pushton Z, Pacheo G. 2017. Explaining ethnic disparities in bachelor's qualifications. New Zealand Productivity Commission. https://www.productivity.govt.nz/assets/Documents/explaining-ethnic-disparities/7129366354/Explaining-ethnic-disparities.pdf.

- Minister of Education. 2019a. Regulatory Impact Assessment: reform of vocational education. https://www.treasury.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2019-08/ria-minedu-rve-jun19.pdf.

- Ministry of Education. 2019b. Reform of vocational education program: programme business case. N. Z. Ministry of Education.

- Ministry of Education. 2022a. Different types of tertiary provider. Ministry of Education. https://parents.education.govt.nz/further-education/different-types-of-tertiary-provider/.

- Ministry of Education. 2022b. School network regions. https://www.education.govt.nz/school/new-zealands-network-of-schools/sc/.

- Morris H, Jacobi L. 2022. It takes the university to close the equity gap. The International Journal of Equity and Social Justice in Higher Education. 1:13–19. doi:10.56816/2771-1803.1006.

- New Zealand Government. 1989. Education Act. Parliamentary Counsel Office. https://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/1989/0080/latest/DLM175959.html.

- New Zealand Government. 2014. Tertiary Education Strategy 2014–2019. https://assets.education.govt.nz/public/Documents/Ministry/Strategies-and-policies/Tertiary-Education-Strategy.pdf.

- New Zealand Government. 2020. Education and Training Act. Parliamentary Counsel Office. https://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2020/0038/latest/LMS172572.html.

- Norton A. 2023. Mapping Australian higher education 2023. Australia National University Centre for Social Research and Methods. https://csrm.cass.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/docs/2023/10/Mapping_Australian_higher_education_2023_005.pdf.

- NZ Chambers of Commerce. 2022. Industry Training Organisations (ITOs). https://hvchamber.org.nz/education-to-employment/industry-training-organisations-itos/.

- OECD. 2021. Service delivery in rural areas. OECD. https://www.oecd.org/governance/service-delivery-in-rural-areas.htm.

- Park PN, Sanders SR, Cope MR, Muirbrook KA, Ward C. 2021. New perspectives on the community impact of rural education deserts. Sustainability. 13(21):12124. doi:10.3390/su132112124.

- Park Z. 2014. What young graduates do when they leave study: new data on the destinations of young graduates. Ministry of Education. https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/147383/What-young-graduates-do-when-they-leave-study.pdf.

- Peercy C, Svenson N. 2016. The role of higher education in equitable human development. International Review of Education. 62(2):139–160. doi:10.1007/s11159-016-9549-6.

- Pickering N. 2021. Enabling equality of access in higher education for underrepresented groups: a realist ‘small step’ approach to evaluating widening participation. Research in Post-Compulsory Education. 26(1):111–130. doi:10.1080/13596748.2021.1873410.

- Porta G. 2022. Travel to tertiary: an analysis of how far school leavers travelled for tertiary study. Ministry of Education. https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/217264/Travel-to-tertiary-002.pdf.

- Public Service Commission. 2022. Central government organisations. https://www.publicservice.govt.nz/system/central-government-organisations/#State-owned-enterprises.

- Ryan J. 2022. Tertiary education sector: what we saw in 2021. Controller and Auditor General. https://oag.parliament.nz/2022/tei-2021-audits/docs/tei-2021-audit-results.pdf.

- Ryan J. 2023. Summary: tertiary education institutions: 2021 audit results and what we saw in 2022. https://oag.parliament.nz/2023/tei-audit-results/docs/summary-tei-audit-results.pdf.

- Satherly P. 2021. Education and two social trust indicators. https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/210042/Education-and-two-social-trust-indicators.pdf.

- Scott D. 2021. Education and health. https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0016/206026/education-and-health-report.pdf.

- Sherwin M, Davenport S, Scott G. 2017. New models of tertiary education. New Zealand Productivity Commission Inquiry into New Models of Tertiary Education, Issue. https://www.productivity.govt.nz/assets/Documents/2d561fce14/Final-report-Tertiary-Education.pdf.

- Sin I, Minehan S, Watson N. 2022. Effective pathways through education to good labour market outcomes for Māori: literature summary. Motu Economic and Public Policy Research. https://motu-www.motu.org.nz/wpapers/22_05.pdf.

- Smyth R. 2012, Sept. 20 years in the life of a small tertiary education system: analysis and advice on tertiary education in New Zealand. Paris: General Conference of the OECD Unit Institutional Management in Higher Education.

- Social Investment Agency. 2017. SIA’s beginners’ guide to the IDI: how to access and use the Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI). https://swa.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Beginners-Guide-To-The-IDI-December-2017.pdf.

- Stats New Zealand. 2018. Study participation (information about this variable and its quality). Stats New Zealand, https://datainfoplus.stats.govt.nz/Item/nz.govt.stats/67b643ce-0ad7-4953-8408-584bf10f5038.

- Stats New Zealand. 2022a. Data in the IDI. Stats New Zealand. https://www.stats.govt.nz/integrated-data/integrated-data-infrastructure/data-in-the-idi#education.

- Stats New Zealand. 2022b. Integrated data infrastructure. Stats New Zealand. https://www.stats.govt.nz/integrated-data/integrated-data-infrastructure/.

- Stats New Zealand. 2023a. NZ.Stat table viewer. Stats New Zealand. https://nzdotstat.stats.govt.nz/wbos/Index.aspx.

- Stats New Zealand. 2023b. Statistical Area 2 2023 (generalised) GIS. Stats New Zealand,. https://datafinder.stats.govt.nz/layer/111227-statistical-area-2-2023-generalised/.

- Steedman SM. 2004. Aspirations of rurally disadvantaged Maori youth for their transition from secondary school to further education or training and work. Department of Labour. https://thehub.swa.govt.nz/assets/documents/Aspirations%20of%20rurally%20disadvantaged%20Maori%20youth.pdf.

- Suhlmann M, Sassenberg K, Nagengast B, Trautwein U. 2018. Belonging mediates effects of student-university fit on well-being, motivation, and dropout intention. Social Psychology. 49:16–28. doi:10.1027/1864-9335/a000325.

- Sydner S. 2014. The simple, the complicated, and the complex: educational reform through the lens of complexity theory. OECD Education Working Papers, Issue. https://www.oecd.org/education/ceri/WP_The%20Simple,%20Complicated,%20and%20the%20Complex.pdf.

- Te Pūkenga. 2022. Engagement: te Pūkenga Operating Model. Te Pūkenga. https://www.xn–tepkenga-szb.ac.nz/our-work/engagement/.

- Tertiary Education Commission. 2019. RoVE News: August 28 2019. Tertiary Education Commisison. https://www.tec.govt.nz/vocational-education/vocational-education/about-vocational-education/vocational-education-news/rove-news-august-28-2019/.

- Tertiary Education Commission. 2023. Introduction to the unified funding system. Tertiary Education Commission. https://www.tec.govt.nz/vocational-education/vocational-education/unified-funding-system-ufs/introduction-to-the-unified-funding-system/.

- Tertiary Education Union. 2019. RoVE announcements an opportunity for all New Zealanders. Tertiary Education Union. https://teu.ac.nz/news/rove-announcements-an-opportunity-for-all-new-zealanders/.

- Theodore R, Taumoepeau M, Kokaua J, Tustin K, Gollop M, Taylor N, Hunter J, Kiro C, Poulton R. 2018. Equity in New Zealand university graduate outcomes: Māori and Pacific graduates. Higher Education Research & Development. 37(1):206–221. doi:10.1080/07294360.2017.1344198.

- Toi Ohomai Institute of Technology. 2022. Annual report. https://www.toiohomai.ac.nz/about/annual-report.

- Ussher S. 2006. What makes a student travel for tertiary study? Ministry of Education. https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/7439/student-travel-tertiary.pdf.

- Van Velle S, Westhorp G, Marchal B. 2022. Realist evaluation. Global Evaluation Initiative. https://www.betterevaluation.org/methods-approaches/approaches/realist-evaluation.

- Waikato Business News. 2019. Farewell for retiring Wintec chief executive. Waikato Business News. https://wbn.co.nz/2019/04/03/farewell-for-retiring-wintec-chief-executive/.

- Waikato Institute of Technology. 2016. Strategic plan 2016-2018 Wintec. https://wintecprodpublicwebsite.blob.core.windows.net/sitefinity-storage/docs/default-source/annual-reports/wintec-strategic-plan-2016-2018.pdf?sfvrsn=7dd6e133_4.

- Waikato Institute of Technology. 2021. Waikato Institute of Technology (Wintec) Te Kuratini o Waikato Investment Plan 2019–2020. https://wintecprodpublicwebsite.blob.core.windows.net/sitefinity-storage/docs/default-source/about-wintec-documents/wintec-investment-plan-2019-2020.pdf?sfvrsn=b1d1bf33_2.

- Ward C. 2001. The impact of international students on domestic students and host institutions. https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/publications/international/the_impact_of_international_students_on_domestic_students_and_host_institutions.

- Watt H, Gardiner R. 2016. Satellite programmes: barriers and enablers for student success. Ako Aotearoa. https://ako.ac.nz/assets/Knowledge-centre/RHPF-N64-Satellite-Programmes/RESEARCH-REPORT-Satellite-Programmes-Barriers-and-Enablers-for-Student-Success.pdf.

- Wikaire E, Curtis E, Cormack D, Jiang Y, McMillan L, Loto R, Reid P. 2016. Patterns of privilege: a total cohort analysis of admission and academic outcomes for Māori, Pacific and non-Māori non-Pacific health professional students. BMC Medical Education. 16. doi:10.1186/s12909-016-0782-2.