ABSTRACT

The link between gender equality and fertility has been the topic of a growing literature. Using data from the International Social Survey Program (ISSP) of 2012 (n = 27,062 individuals, 39 countries), and applying multi-level modelling techniques, we explored the associations between individual gender egalitarian attitudes, societal gender equality and fertility ideals. The results show that individual gender egalitarianism is negatively associated with fertility ideals even across a broad set of countries from different regions. Additionally, we find that while societal gender equality is positively associated with fertility ideals, we also observe a small but statistically significant interaction effect between individual attitudes and societal gender equality. The cross-level interaction suggests that the negative fertility implications of individual egalitarian attitudes are amplified rather than mitigated in gender equal contexts. Thus, while the findings point to the potential importance of context and societal gender equality, they do not clearly confirm dominating theories. In future, the interplay between individual attitudes and societal support should be further explored in cross-country research, and more studies should include countries from the global South.

Introduction

The latter half of the twentieth century has seen several structural changes within society and the household unit, with women increasingly entering the workforce and men entering care-giving roles (Knight & Brinton, Citation2017). These developments towards more gender-egalitarian societies coincide with declining fertility trends and, as a result, a vast literature has developed around the issue of gender equality and fertility, particularly in Western developed societies. Notably, however, results point in different directions depending on the level of measurement. In general, micro-level studies show a negative correlation between individual egalitarianism and fertility (Jang et al., Citation2017; Lappegård et al., Citation2021) while macro-level studies indicate that, beyond a certain threshold, societal gender equality is conducive to fertility (Arpino et al., Citation2015; Kolk, Citation2019). At the same time, very few studies have explored the interplay between individuals’ gender egalitarianism and societal support for gender equality in relation to fertility.

In the present article, we use ISSP data to compare fertility ideals in 39 countries representing different parts of the world. The overall aim is to study how individual egalitarianism and societal gender equality might influence fertility ideals. Using multilevel modelling, we first examine the association between individual gender egalitarian attitudes and fertility ideals across this broad set of countries. Secondly, we investiagte whether societal gender equality, measured by the Global Gender Gap index, can modify the association between individual egalitarianism and fertility ideals.

Previous research on gender equality and fertility

Several scholars have argued that changes in gender role attitudes and practices, both in the public sphere and within the household influence ideals and decisions related to fertility (Goldscheider et al., Citation2013). Empirically, a range of studies have explored the correlation between gender role attitudes and fertility at the individual level, typically finding that more gender egalitarian attitudes are associated with lower levels of fertility or fertility intentions (Jang et al., Citation2017; Lappegård et al., Citation2021; Li et al., Citation2021). That is, individuals with more gender egalitarian attitudes tend to prefer fewer children than individuals with more traditional attitudes.

Theoretically, such findings have been attributed to tensions between work and family roles. Women with egalitarian attitudes may be more oriented towards employment and career, and due to expected conflict between the work and family demands, they may prefer fewer children than women focused on a traditional caring role (Lappegård et al., Citation2021).Footnote1 Another explanation is that for individuals with more egalitarian attitudes, ideas of femininity may be less dependent on adhering to traditional mothering norms and thus, they may be more prone to remain voluntarily childless (Agrillo & Nelini, Citation2008).

At the same time, however, individuals’ deliberations on gender roles, work-family reconciliation and fertility are likely to be influenced by the social norms and institutions of their society, with countries still varying substantially regarding the opportunities provided for women (and men) (Kolk, Citation2019). A number of studies have explored this relationship between gender equality and fertility at the macro-level. A main theory explaining the association has been put forward by McDonald (Citation2000, Citation2013), who argues that the relationship between gender equality and fertility within a society is not unidirectional, but rather follows a U-shaped curve. When women enter the workforce, while retaining a main responsibility for housework and childcare, the more enhanced burden of balancing the work and family spheres can cause a decline in fertility, as more women will chose the ‘exit route’ and have fewer or no children (Anderson & Kohler, Citation2008). However, according to McDonald (Citation2000), the negative correlation between gender equality and fertility will be reversed once countries provide sufficient institutional support for gender equality. Empirically, some macro-level studies have provided support to this prediction of a U-shaped relationship between gender equality and fertility by showing that higher levels of societal gender equality tends to be associated with higher fertility (Arpino et al., Citation2015; Kolk, Citation2019). In the same vein, Baizan et al. (Citation2016) show that contexts providing policies that support de-familialization of care display higher levels of fertility.

Contribution and hypotheses

Although an extensive literature has developed on the topic, our understanding of the relationship between gender equality and fertility remains incomplete. As discussed, empirical findings are puzzling given that micro-level studies tend to show negative correlations while some positive associations are found at the macro-level. Furthermore, most studies have focused on European/Western industrialized countries, and the interplay between individual egalitarianism and societal context has not been sufficiently explored.

The present study makes two main contributions to the literature. First, we consider both individual- and country-level predictors of fertility ideals and measure directly the interplay between individual egalitarianism and societal gender equality. Previous research suggests that the negative fertility implications of changing gender roles – particularly women’s commitment to work and career – can be a transitional phenomenon that is contingent on the context. As discussed, McDonald (Citation2000, Citation2013) argues that the work-family tensions that drive women to limit their fertility aspirations will diminish when societies develop more supportive institutions. Further, as noted by Goldscheider et al. (Citation2015) this would require policies that support not only women’s employment but also men’s involvement in care work, that is a dual-earner/dual-carer policy model.Footnote2 Based on such reasoning, we will empirically examine whether a high level of societal gender equality can mitigate a negative correlation between the individual’s gender egalitarianism and their fertility ideals. The basic argument is that in a context where the dual-earner/dual family model is institutionalized, work and family will not be regarded as incompatible and therefore, career-minded women may be less inclined to forego children than women in countries based on a male provider model. While prior studies have attempted to highlight the importance of context (Lappegård et al., Citation2021), most studies do not look simultaneously at individual and societal gender equality, and to the best of our knowledge, the interaction between individual gender egalitarian attitudes and societal gender equality has not been studied empirically.

Second, we broaden the perspective by including 39 countries representing different regions of the world. This approach ensures a larger variation both in terms of individual egalitarianism and societal institutions as compared with most previous studies. Methodologically, we add to previous research by applying multi-level modelling techniques (see methods section) and a comprehensive measure of societal gender equality, namely the Global Gender Gap (GGG) index. To the best of our knowledge only one prior study explores how comprehensive gender equality is associated with fertility (Mills, Citation2010).Footnote3 The study shows that higher scores on the Global Gender Gap Index (GGG) were positively associated with fertility intentions, although this result is not significant. While this study highlights the importance of country or societal context, it also corroborates with previous evidence demonstrating that even among countries with similar levels of development, overall gender equality is one of the most crucial deciding factors for predicting fertility trends (Myrskylä et al., Citation2011).

Further, it is worthwhile to note the considerable variation in terms of the measures of gender equality at the individual level. For instance, in previous research, measures of gender equality tend to vary, with studies at the individual-level focusing either on egalitarian attitudes (Lappegård et al., Citation2021; Okun & Raz-Yurovich, Citation2019; Puur et al., Citation2008) or domestic division of labour (Goldscheider et al., Citation2013; Kan et al., Citation2019). Further, it is interesting to note that the manner in which gender equality is measured also differs globally. For instance, studies from Asia and Africa often formulate questions around gender equality relating more to concepts such as women’s empowerment and decision making (Upadhyay et al., Citation2015). Within this study, we utilize gender egalitarian attitudes as the measure of gender equality at the individual level. In doing so, we aim to add to research providing a more global cross-country perspective on the variations in egalitarian attitudes across a broad set of countries and on the relationship between gender equality and fertility.

To operationalize fertility, we use fertility ideals. In literature that examines the association between gender equality and fertility, we see that there are several inconsistencies in fertility measurement. Often, studies focus on actual fertility (the number of children an individual has) or on fertility intentions, with limited studies that aim to provide insights on an individual’s fertility ideals. While actual fertility or fertility intentions can provide useful information on an individual’s fertility behaviour, they are often influenced by a number of socio-demographic, economic and cultural factors (Götmark & Andersson, Citation2020). Additionally, since fertility behaviour follows a sequential process, measuring fertility in the form of ‘fertility intentions’ refers to a more actionable plan as compared with ‘ideals’ (Chen & Yip, Citation2017). In this study, we focus on measuring an individual’s fertility ideals. Since we are examining individuals’ attitudes, societal gender equality and its association with fertility, ‘ideals’ then becomes a useful tool as it provides a more accurate reflection of societal norms whilst still being indicative of individual preferences (Philipov & Bernardi, Citation2012). In contrast to studies examining actual fertility or fertility intentions, there have been limited studies that explore an individual’s fertility ideals, and how these vary by societal context. Thus, by focusing on fertility ideals within this study, we attempt to fill this gap in literature and enhance our understanding of the association between gender equality and fertility.

Hypotheses

Based on the arguments outlined above, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Globally, gender egalitarian attitudes are negatively associated with fertility ideals. That is, controlling for socio-demographic characteristics, individuals with gender egalitarian attitudes display lower fertility ideals as compared to individuals with traditional attitudes.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): On average, fertility ideals are higher in countries with high levels of societal gender equality and stronger institutional support for gender equality (as measured by the Global Gender Gap Index).

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Finally, the negative correlation between individual gender egalitarian attitudes and fertility ideals is moderated by societal gender equality. In other words, this correlation will be weaker in countries with high scores on the Global Gender Gap Index than in those with lower scores.

Materials and methods

The data for the analysis comes from the 2012 wave of the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) on Family and Changing Gender Roles. The ISSP is a cross-national set of surveys which includes information on a wide range of topics. In total, 41 countries participated in the survey, however two of these were excluded from the analysis due to lack of information on societal gender equality (Taiwan) and individual egalitarianism (Spain). Further, we selected individuals aged 14–50 years in order to make the sample representative of individuals in childbearing ages. The final sample included 27,062 individuals nested in 39 countries.

The outcome variable in the analysis is fertility ideals. It is based on the question ‘All in all, what do you think is the ideal number of children for a family to have?’, which the survey respondents were asked to answer by providing a numeric value.Footnote4 The variable ranges from 0 to 45. In order to identify the potential outliers, we calculated the z-score for all observations within the sample. Based on the general rule of thumb, any z-score greater than 3 or less than −3 is considered to be an outlier (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2013) and thus, we removed those data points that had z-scores outside this range (89 observations). Following the removal of outliers, the variable ranges from 0 to 7.

The main explanatory variable at the individual level is gender egalitarian attitudes. Here, we used four survey items that capture attitudes towards women’s employment and their role within the household. The response options were designed as a Likert scale with the alternatives strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, strongly disagree. Gender egalitarian attitudes is an additive index of the four items, which are as follows:

‘A preschool child is likely to suffer if his/her mother works’

‘All in all, family life suffers if a woman has a full-time job’

‘A job is alright, but what most women really want is a home and children’

‘A man’s job is to earn money; a woman’s job is to look after the house’

The Cronbach’s Alpha for the index is 0.76 and the scale varies from 4 to 20, with higher scores signifying more egalitarian attitudes. Participants who indicated that they ‘Don’t know’ (N = 648) or ‘Can’t choose’ (N = 3,114) were excluded from the analysis.

At the country-level the main explanatory variable is societal gender equality, measured with the Global Gender Gap Index (GGG) developed by the World Economic Forum. Specifically, we used the statistics in the Global Gender Gap Report 2012 (Hausmann et al., Citation2006). The GGG is a multidimensional measure based on four specific areas of gender equality: level of economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, health and survival and political empowerment of women. This is a suitable measure for this study, as we needed a comprehensive indicator that could be applied across a large number of countries in which gender equality is at different stages and may take different forms. On a scale of 0–1, a higher score on the Global Gender Gap Index (GGG) indicates higher levels of societal gender equality and the countries included in this study ranged from 0.60 (Turkey) to 0.86 (Iceland).

Control variables

The socio-demographic controls included educational level, age, marital status, number of children in the household, current work status and sex. Years of education and age were used as continuous variables. Marital status, number of children and work status were coded into dummy variables with the following categories: Currently married (reference: Unmarried); One or more children in the household (reference: No children), In paid work (reference: Not in paid work) and Female (reference: Male). At the country-level, we controlled for Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita.

presents the socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants. About 55% of the participants identified as female. Overall, 54% of the participants reported being married and 61% of participants had at least one child in the household. On average, the participants were 35 years old and had spent 12 years in education.

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of survey participants (N = 27,062).

Analytic plan

Multi-level regression models were utilized to explore how individual attitudes towards gender equality and societal gender equality might influence fertility ideals. Multi-level modelling allows us to take into account the clustered nature of the data, that is, the fact that individuals are nested within countries. Thus, it allows for a more precise estimation than OLS models which assume that all individuals are independent (Hox,Citation2010). In line with common practice, we first run a null model to ascertain whether the individual’s country of residence explained any of the variance in fertility ideals, thus justifying the need for multi-level models. We then estimate four multi-level models examining the association between individual and country-level factors and fertility ideals. In models 1 and 2, we study the individual-level relationships by including gender egalitarian attitudes and socio-economic controls (H1). To understand how fertility ideals varies across countries with differing levels of gender equality (H2), we add the Global Gender Gap Index (GGG) as a continuous variable in Model 3. However, considering the discussions above (e.g. the U-curve hypothesis), there is also reason to further compare countries that are at different levels of gender equality. Thus, in model 4, we divide the GGG measure into quartiles. Here, Quartile 4 comprises countries with the highest scores on the GGG, i.e. the highest level of gender equality. At the other end of the spectrum, Quartile 1 comprises the countries with the lowest levels of gender equality. Finally, to address H3, an interaction term for individual egalitarian attitudes and societal gender equality, namely GGG*Gender Egalitarian Attitudes, is added in Model 5.

Results

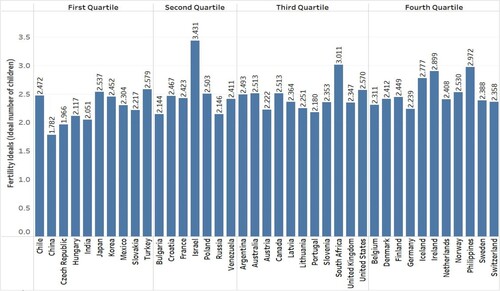

We first provide an overview of country-level fertility ideals, segregated by quartiles measuring societal gender equality (). Quartile 4 includes countries ranked with the highest levels of gender equality (based on the Global Gender Gap Index), while quartile 1 represents the least gender equal countries. Overall, we see a somewhat consistent pattern across quartiles, although the most gender equal quartile (quartile 4) includes three of the countries with the highest reported fertility ideals (Iceland, Ireland and the Philippines). Conversely, the results show that the least equal gender quartile (quartile 1) has some of the countries with the lowest reported fertility ideals (China, India, Czech Republic). While there is not a lot of variation within quartiles, we see that Israel comes up as an anomaly in quartile 2 with being the highest in fertility ideals (3.43).

Figure 1. Fertility Ideals (Ideal number of children per person) within countries by gender equality quartiles*.

*The countries included in the analysis are grouped according to quartiles based on their scores for the Global Gender Gap Index. Countries in Quartile 4 represent those with the highest scores on the Global Gender Gap Index, and highest levels of gender equality.

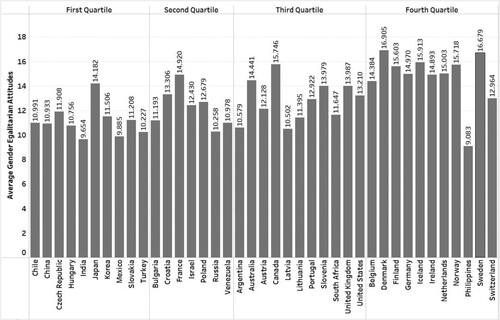

shows the country-level aggregates for gender egalitarian attitudes. Unsurprisingly, we find that the most gender equal countries (quartile 4) also show the most egalitarian attitudes among individuals. Within this quartile, the Nordic countries of Sweden, Denmark and Iceland have the most gender egalitarian attitudes. In quartile 4, Philippines emerges as an anomaly reporting the lowest levels of egalitarian attitudes despite being one of the countries with the highest overall score on the Global Gender Gap index.

Figure 2. Aggregate gender egalitarian attitudes within countries by gender equality quartiles*.

*The countries included in the analysis are grouped according into quartiles based on their scores for the Global Gender Gap Index. Countries in Quartile 4 represent those with the highest scores on the Global Gender Gap Index, and highest levels of gender equality.

Results from regression analyses

presents the results from the multi-level regression models. The null model shows that individuals are indeed clustered in groups at the country-level. According to the intra-class correlation coefficient, 13% of the variance is concentrated at the country-level.Footnote5 Our first hypothesis (H1) concerns the association between individual gender egalitarian attitudes and fertility ideals. In Model 1, the negative and statistically significant coefficient indicates that individuals with more gender egalitarian attitudes report lower fertility ideals than those who have more traditional attitudes. After controlling for socio-demographic variables in Model 2, the size of the coefficient decreases but remains statistically significant (B = −0.017, p < 0.001). Additionally, we see that work status, education, marital status and number of children within the household are significantly associated with fertility ideals. Individuals who already had children in the household had higher fertility ideals than those who did not have children (B = 0.107, p < 0.001). In contrast, those who reported being currently unemployed had lower fertility ideals as compared to individuals who were in paid work (B = −0.095, p < 0.001). Finally, no gender differences in fertility ideals appear when controlling for socio-demographic variables and individual attitudes.

Table 2. Results from multi-level regression analysis model for fertility ideals, including interaction of individual and country-level factors (n = 27,062).

In Model 3 we introduce the variable measuring societal gender equality, that is, the Global Gender Gap Index (GGG). As shown, the GGG is positively associated with individual fertility ideals, however, this relationship is not statistically significant. In Model 4, we instead use the GGG index divided into quartiles. With this measurement, the average reported fertility ideals was significantly higher for individuals in both quartile 2 and quartile 4 in comparison to the least gender equal countries in quartile 1. Thus, controlling for socio-demographic factors and individual egalitarian attitudes, we find that individuals belonging to countries that had a more gender equal context had higher fertility ideals as compared with individuals from countries that were unequal.

Next, we turn to H3 which stated that the negative association between individual-level egalitarianism and fertility ideals would be moderated by societal gender equality, such that the correlation would be weaker in more gender equal countries. To explore this proposition, an interaction term (egalitarian attitudes*GGG) was added in Model 5. As shown, there is a small but statistically significant interaction effect, however, it is observed only between quartile 1 and quartile 4 and, more importantly, it is not in the expected direction. Contrary to expectations, we find that the negative association between individual attitudes and fertility ideals is comparatively larger in the most gender equal countries (quartile 4) than in those with the lowest levels of societal gender equality (quartile 1).

As a robustness check, we re-ran the models using an alternate measure of societal gender equality. Instead of the Global Gender Gap Index, we tested the models using a continuous variable measuring country-level aggregates of egalitarian attitudes. We obtained similar results, and a significant and negative interaction effect of individual and country-level attitudes on fertility ideals, lending support to our hypothesis. We also ran a three-way interaction of individual attitudes, societal gender equality and gender to ascertain whether the results differed by sex, however, we found no statistically significant interaction effect in this case. Furthermore, we note that China could be considered somewhat of an anomaly because of a history of restrictive family policies. Thus, we conducted a sensitivity analysis removing China from the data. However, we did not see any notable differences in the results.

In sum, the results support H1, as they demonstrate that there is a statistically significant and negative association between individual gender egalitarian attitudes and fertility ideals even in this broad set of countries. Also, H2 receives some support, as fertility ideals are clearly lower in the most unequal countries than in the most equal countries. Finally, in terms of H3, although we do find a significant cross-level interaction, it suggests that the negative implications of individual-level egalitarianism are amplified rather than moderated in highly equal societies.

Discussion

Changing gender roles – in particular, women’s increasing commitment to work and career – have been widely discussed as a driver of declining fertility levels. Despite a growing literature, however, the discrepancies between micro- and macro-level findings and the geographical delimitation of the research raise new questions about the links between gender equality and fertility. The thrust of this study, based on ISSP data, was to simultaneously explore the importance of individual egalitarian attitudes and societal gender equality for fertility ideals across 39 countries in different parts of the world.

At the micro level, the results show that fertility ideals are lower among individuals with more gender egalitarian attitudes than among those with more traditional attitudes towards women’s roles in work and family. Although such a negative correlation has been reported in several studies (Jang et al., Citation2017; Lappegård et al., Citation2021), our study contributes by replicating these results for countries outside of a western and Euro-centric context. The negative correlation has been regarded as indicative of the challenges facing women at a stage where they engage in paid work but retain the responsibility for childcare and housework (Lappegård et al., Citation2021; Testa, Citation2007). The negative correlation across contexts with varying norms and institutions suggests that most countries are still at this stage, termed as the first half of the gender revolution (Goldscheider et al., Citation2015). Additionally, considering that much discussion has focused on women’s conflicts between work and family, it is interesting to note that the association between egalitarian attitudes and fertility ideals does not differ by gender.

Arguably, however, the relationship between gender equality and fertility cannot be fully understood by considering only individual characteristics and attitudes. The importance of the context has been highlighted by McDonald’s (Citation2000) theory that as societies move further along the gender revolution and develop institutions and mechanisms supporting the combination of work and family life, there is a reversal in the declining fertility trend. Our study lends some support to these arguments. Using the Global Gender Gap Index, we find a positive but non-significant linear association between societal gender equality and fertility ideals, while a quartile-based measure shows that individuals from countries that have the highest scores on the Global Gender Gap Index and belong to the most gender equal quartile (quartile 4) have higher fertility ideals. In many of the countries in this quartile, such as the Nordic countries, individuals have access to supports such as public childcare and long paid parental leave. Thus, for countries belonging to this quartile, institutional supports and family-friendly policies could perhaps help reduce the impact of a work-family conflict enabling individuals to realize their fertility ideals (Baizan et al., Citation2016).

Finally, a main contribution of the study was to explore the interaction between individual egalitarianism and societal gender equality in relation to fertility ideals. We hypothesized that the negative implications of individual egalitarianism would be modified in societies with strong support for gender equality; however, this prediction was not borne out. Instead, we found a negative interaction coefficient showing that individual egalitarian attitudes take on greater importance in the most gender equal quartile of countries as compared to the least equal quartile. A possible explanation for this counter-intuitive finding might be that since countries scoring high on the Global Gender Gap Index provide extensive support for work-family reconciliation, individual preferences may be more consequential. Arguably, individuals (not least women) in such countries may be less dependent on family ties and thus, fertility decisions might be more influenced by their own preferences and choices. In contrast, among countries that rank lower in overall gender equality, the individuals’ fertility ideals may reflect both expectations and support from family or community to a larger extent. Given the modest size of the coefficient, the finding should not be over-interpreted but points to the need for further exploration.

A limitation of the present study is that it uses cross-sectional data, which provides only a snapshot of countries at a certain time and does not allow us to track within-person changes or country-level moves towards more egalitarianism. This study utilizes ISSP data from 2012; although, a more recent version of this module has been repeated in 2022, it was not available at the time of the study. Also, while the ISSP data enables us to include a wide range of countries, several countries with very low levels of gender equality, e.g. in the Middle East and Africa were not included. Further, the conceptualization of gender equality is worth considering. The measure of gender egalitarian attitudes used in this study primarily captured views on women’s roles in the family and household. Ideally, however, attitudes towards men’s involvement in the domestic sphere should also be measured (Neyer et al., Citation2013). Finally, the ISSP 2012 questionnaire includes information on whether respondents currently had any children living in the household, with no survey questions on total number of children ever born or pregnancies that an individual had. This prevented any differentiation between individuals who have never had children and those that currently do not have children within the household, thus not allowing for an in-depth analysis on whether number of children might influence the relationship between gender equality and fertility explored in this study.

All in all, the study adds to the literature by including a broader set of countries and by considering the direct and interactive effects of individual and societal-level gender equality. To further our understanding of the complex relationship between gender equality and fertility, we would like to point to two avenues for future research. First, the interplay between individual and context has been understudied. Here, both theoretical development and empirical explorations are needed to reveal mechanisms at different levels. Second, the discussion should be extended beyond the context of developed and middle to high income countries. This is imperative from a global perspective to understand how societies can reconcile gender equality with sufficiently high fertility.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability

The data used in this study is available from the International Social Survey Program (ISSP) – https://issp.org/

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Interestingly, however, some studies suggest that patterns may vary by gender. For example, research from Europe that focuses specifically on men’s gender role attitudes find that men with egalitarian attitudes in fact have higher fertility aspirations than their more traditional counterparts (Okun & Raz-Yurovich, Citation2019).

2 Goldscheider et al. (Citation2015) discuss men’s gender changing roles as crucial to increases in fertility. The authors discuss a gender revolution as having two parts; the first part refers to the phase when women enter the public sphere (notably the workforce) at a large scale. At this stage, the prospect of a double burden with both paid and unpaid work will force women to limit their fertility; however, at the second stage, when men are more actively involved in housework and childcare these problems will be mitigated and thus, fertility can increase.

3 In their study, Mills (Citation2010) utilizes six gender inequality indices and examines their effect on fertility intentions using data from 24 countries across Europe. The findings reveal a positive association between gender equality and fertility intentions, such that higher scores on Gender-related Development Index (GDI) and Gender Equity Index (GEI) were significantly associated with higher fertility intentions.

4 The measurement of fertility ideals here could be argued to be ambiguous due to the lack of a reference point in the survey question. That is, respondents were not specifically asked whether the question pertained to their personal preferences or to societal ideals. However, since the question is framed in a manner that is open to interpretation, it seems unlikely that individuals would specifically answer in line with societal ideals of fertility.

5 The clustering at the group-level is captured by the intra-class correlation coefficient which is the variance at the group-level divided by the sum of the variance at the individual and the group level.

References

- Agrillo, C., & Nelini, C. (2008). Childfree by choice: A review. Journal of Cultural Geography, 25(3), 347–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/08873630802476292

- Anderson, T., & Kohler, H. P. (2015). Low fertility, socioeconomic development, and gender equity. Population Development Review, 41(3), 381–407. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00065.x

- Arpino, B., Esping-Andersen, G., & Pessin, L. (2015). How do changes in gender role attitudes towards female employment influence fertility? A macro-level analysis. European Sociological Review, 31(3), 370–382. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcv002

- Baizan, P., Arpino, B., & Delclòs, C. E. (2016). The effect of gender policies on fertility: The moderating role of education and normative context. European Journal of Population, 32(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-015-9356-y

- Chen, M., & Yip, P. S. F. (2017). The discrepancy between ideal and actual parity in Hong Kong: Fertility desire, intention, and behavior. Population Research and Policy Review, 36, 583–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-017-9433-5

- Goldscheider, F., Bernhardt, E., & Brandén, M. (2013). Domestic gender equality and childbearing in Sweden. Demographic Research, 29(December), 1097–1126. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2013.29.40

- Goldscheider, F., Bernhardt, E., & Lappegård, T. (2015). The gender revolution: A framework for understanding changing family and demographic behavior. Population and Development Review, 41(2), 207–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00045.x.

- Götmark, F., & Andersson, M. (2020). Human fertility in relation to education, economy, religion, contraception, and family planning programs. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8331-7

- Hausmann, R., Tyson, L. D., & Zahidi, S. (2006). The global gender gap report 2006. Geneva, Switzerland: World Economic Forum.

- Hox, J. J. (2010). Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications (2nd ed.). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Jang, I., Jun, M., & Lee, J. E. (2017). Economic actions or cultural and social decisions? The role of cultural and social values in shaping fertility intention. International Review of Public Administration, 22(3), 257–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/12294659.2017.1368004

- Kan, M. Y., Hertog, E., & Kolpashnikova, K. (2019). Housework share and fertility preference in four East Asian countries in 2006 and 2012. Demographic Research, 41(October), 1021–1046. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2019.41.35

- Knight, C. R., & Brinton, M. C. (2017). One egalitarianism or several? Two decades of gender-role attitude change in Europe. American Journal of Sociology, 122(5), 1485–1532. https://doi.org/10.1086/689814

- Kolk, M. (2019). Weak support for a U-shaped pattern between societal gender equality and fertility when comparing societies across time. Demographic Research, 40(January), 27–48. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2019.40.2

- Lappegård, T., Neyer, G., & Vignoli, D. (2021). Three dimensions of the relationship between gender role attitudes and fertility intentions. Genus, 77(1), https://doi.org/10.1186/s41118-021-00126-6

- Li, Z., Yang, H., Zhu, X., & Xie, L. (2021). A multilevel study of the impact of egalitarian attitudes toward gender roles on fertility desires in China. Population Research and Policy Review, 40, 747–769. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-020-09600-z

- Mcdonald, P. (2000). Gender equity, social institutions and the future of fertility. Journal of Population Research, 17, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03029445.

- Mcdonald, P. (2013). Societal foundations for explaining fertility: Gender equity. Demographic Research, 28, 981–994. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2013.28.34.

- Mills, M. (2010). Gender roles, gender (In)equality and fertility: An empirical test of five gender equity indices. Canadian Studies in Population, 37(3–4), 445. https://doi.org/10.25336/P6131Q

- Myrskylä, M., Hans-Peter, K., & Francesco, B. (2011). High development and fertility: Fertility at older reproductive ages and gender equality explain the positive link. Population Studies Center, University of Pennsylvania, PSC Working Paper Series, PSC 11-06. http://repository.upenn.edu/psc_working_papers/30/

- Neyer, G., Lappegård, T., & Vignoli, D. (2013). Gender equality and fertility: Which equality matters?. European Journal of Population, 29, 245–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-013-9292-7.

- Okun, B. S., & Raz-Yurovich, L. (2019). Housework, gender role attitudes, and couples’ fertility intentions: Reconsidering men’s roles in gender theories of family change. Population and Development Review, 45(1), 169–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12207

- Philipov, D., & Bernardi, L. (2012). Concepts and operationalisation of reproductive decisions: Implementation in Austria, Germany and Switzerland. Comparative Population Studies, 36, 2–3. https://doi.org/10.12765/CPoS-2011-14.

- Puur, A., Oláh, L. S., Tazi-Preve, M. I., & Dorbritz, J. (2008). Men’s childbearing desires and views of the male role in Europe at the Dawn of the 21st century. Demographic Research, 19, 1883–1912. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2008.19.56

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.). Pearson.

- Testa, M. R. (2007). Childbearing preferences and family issues in Europe: Evidence from the Eurobarometer 2006 survey. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 5, 357–379. https://doi.org/10.1553/populationyearbook2007s357

- Upadhyay, U. D., Gipson, J. D., Withers, M., Lewis, S., Ciaraldi, E. J., Fraser, A., Huchko, M. J., & Prata, N. (2015). Women’s empowerment and fertility: A review of the literature. Social Science and Medicine, 111, 111–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.06.014