ABSTRACT

The Capuchin Catacombs of Palermo are one of the most visited sites on the island of Sicily and are home to one of the world’s largest assemblages of human mummies. Within the framework of a multidisciplinary project aimed at investigating the biohistories of non-adults buried at this site, the authors wished to better understand how visitors felt about the display of these young individuals and whether they had prior knowledge of these mummies before their visit. In order to capture guest feedback, questionnaires were distributed to 105 visitors in September 2022. While there were no clear-cut patterns based on the demographic and social attributes of visitors, this research revealed some recurring themes. Several visitors felt that there should be signs warning guests of the Children’s Room due to the large number of young individuals displayed in this area. Furthermore, visitors felt that more information was needed throughout the site and queried whether the non-adults, or their kin, had consented to their display. These issues could be addressed by the inclusion of information boards in the catacombs. The findings of this research ultimately have implications for the way in which non-adult remains are displayed in catacombs and other heritage contexts.

Introduction

Within contemporary western society, encounters with the dead are a rarity (Blanco and Vidal Citation2014; Mather Citation2024). Interactions with death are typically reserved to medical settings, funerals of loved ones, or during visits to museums and heritage sites (Brooks and Rumsey Citation2008). The display of Egyptian mummies is always one of the most popular exhibits in museums and allows the public to face death in ways that would not normally be possible (Taylor and Antoine Citation2014). In museums, human remains are often housed in climate-controlled glass cases and, increasingly, there are notices warning visitors of the presence of skeletons or mummies in certain areas of an exhibition (Bonney, Bekvalac, and Phillips Citation2019; Redfern and Bekvalac Citation2013; Stringer Clary Citation2018). Some have suggested that the display of human remains in these settings removes the corporeal aspect of the body and transforms them into ‘objects’ (Alberti et al. Citation2009; Licata et al. Citation2020; Nilsson Stutz Citation2023). In contrast to museums, catacombs offer an entirely different experience for the visitor as human remains, either skeletonised, partially skeletonised, or mummified, are rarely in glass casesFootnote1 meaning the barrier between life and death is removed.

The Capuchin Catacombs in Palermo, Sicily, are an excellent example whereby visitors can walk through a network of corridors which are lined with mummified and partially mummified remains. This site is of particular importance as it is the largest of its kind in Europe, containing over 1,284 spontaneous and anthropogenic mummiesFootnote2 (Squires and Piombino-Mascali Citation2021). The catacombs were initially founded by the Capuchin Order in 1599 C.E. as a place to store the spontaneously mummified bodies of 45 Capuchin Friars (Squires and Piombino-Mascali Citation2024). Initially, the funerary space was reserved for the clergy but was subsequently opened up to the nobility and the middle classes (Piombino-Mascali Citation2018). This mortuary rite was expensive and was consequently reserved for the wealthiest members of society. Those able to afford this rite (or their surviving kin) consented to the mummification process and indefinite display in the catacombs. The mummification process took place in drainage rooms within the catacombs. Individuals were afforded enhanced spontaneous mummification, which involved draining the body fluids and drying the body out before being filled with taw and straw, or anthropogenic mummification, which involved the removal of internal organs or injecting chemicals to preserve the body. The dead were dressed in their finery and displayed for the purpose of commemoration and worship as it was believed that mummification preserved the social persona after death (Piombino-Mascali et al. Citation2012; Squires and Piombino-Mascali Citation2021). The practice of mummifying the dead continued in Palermo until 1880 C.E. when political and social changes led to the implementation of stronger hygiene measures and the use of new cemeteries (Piombino-Mascali and Nystrom Citation2020).

Since its inauguration in the late sixteenth century, the site has been open to visitors, either for religious purposes, morbid curiosity, or lay fascination. In the early years, guests were predominantly the local populace visiting their deceased relatives but with the increase in mass tourism in the mid-twentieth century, tourists have outnumbered the small number of locals that frequent the underground crypt. Every year, the catacombs attract thousands of visitors from around the world, many of whom are part of organised trips with cruise tour operators (Squires and Piombino-Mascali Citation2021). Yet despite such high volumes, there is limited official online reading material that tourists can study in preparation for their excursion; thus, relying heavily upon the official (Sito ufficiale delle Catacombe Frati Cappuccini Palermo Citation2022) and unofficial (Palermo Catacombs Citationn.d.) Capuchin Catacombs websites, Wikipedia (Wikipedia Citation2023), and TripAdvisor (Squires and Piombino-Mascali Citation2021).

Of the 1,284 individuals housed in the Capuchin Catacombs, 163 belong to neonates, infants, and children. The presence of children, bar the famous mummy of Rosalia Lombardo, is not well-reported in tourist-focused literature except for the official (Sito ufficiale delle Catacombe Frati Cappuccini Palermo Citation2022) and unofficial (Palermo Catacombs Citationn.d.) websites and an online audio guide about the site (Piombino-Mascali and Franco Citation2016). As a result, those visiting may be unaware of the inclusion of neonate, infant, and child mummies. Very little research has been published which solely focuses on public perceptions of the display of non-adult human remains (e.g. Squires and Piombino-Mascali Citation2021; Wilson Citation2015). The majority of research that explores visitor reactions to non-adult remains typically form part of larger studies that look at the display of human remains more generally (e.g. Biers Citation2019; Chamberlain and Parker Pearson Citation2001; Korn and Associates, Inc. Citation1999; Leeds Museums and Galleries Citation2018; Quorum Citation2019; Wilson Citation2015). One of the drawbacks with many of these pieces of research is that the emphasis is on displays in museums, and not catacombs. Squires and Piombino-Mascali (Citation2021) examined 1,011 English TripAdvisor reviews of the Capuchin Catacombs of Palermo in July 2020 to better understand visitor attitudes towards non-adult remains. Of the reviews examined, only 220 (22%) mentioned the presence of children’s remains. Visitors held mixed views towards the young individuals at this site, which was akin to those in studies that focused on museums. Following on from this preliminary study, and as part of a wider research project on the mummified and skeletonised remains of non-adults in the Capuchin Catacombs, two of the authors (KS and DP-M) felt it was necessary to speak with visitors to better understand their attitudes towards the display of juvenile human remains, and whether social and cultural factors play a part in their perceptions of these children. The research also aimed to explore whether visitors had prior knowledge of the non-adult mummies before their excursion to the site and if this influenced their decision to visit. Furthermore, the authors hoped to establish whether visitors had sufficient access to contextual information about the catacombs before and during their excursion. This article reports on the findings from this research and presents broader implications for catacombs, museums, and other heritage settings that display the remains of young individuals.

Method

Based on the findings of a preliminary study conducted by two of the authors (KS and DP-M) in 2020, exit questionnaires were developed to address gaps in the research, such as comparisons between demographic data and attitudes towards non-adult mummies (Squires and Piombino-Mascali Citation2021). Questionnaires were subsequently distributed to visitors at the Capuchin Catacombs between Monday 19 September 2022 and Friday 23 September 2022. Respondents were required to complete a consent and participation form prior to filling out the research questionnaire. It was emphasised that no identifying information would be collected. All documents were available in both English and Italian to capture a range of perspectives. Quantitative and qualitative data were captured through the use of these questionnaires. Visitors were asked to provide basic demographic data (questions 1–5), alongside details of their prior knowledge of the site (questions 6–8), how the non-adult mummies made them feel and whether such young individuals should be displayed (questions 9–15), and the availability of information in the catacombs (questions 16–17; the full list of questions can be found in ). Upon completion, all questionnaires were assigned a unique participant (P) number; this facilitated data organisation and analysis. In total, responses from 105 visitors were collected, all of whom were over 18 years of age. Data were subsequently analysed using Microsoft Excel 2021, IBM SPSS version 29, and R version 4.2.0. In some cases, statistical analyses could not be carried out due to the small numbers of respondents in some demographic groups. Ethical approval to conduct this research was granted by the Staffordshire University Ethics Committee on 10 November 2021 (reference: DEF-KES-004; SU_21_025).

Table 1. Questions included in the visitor questionnaire.

Results and discussion

Demographics

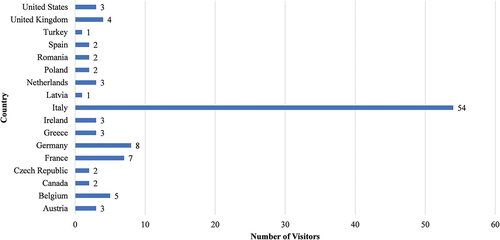

Of the 105 respondents, 54 (51.4%) visitors were from Italy while those from other countries hailed from across Europe and North America, and were recorded in much smaller numbers (). Only one person was from Palermo, indicating other visitors had heard of the site through other means. The Capuchin Catacombs are located around two kilometres from the centre of Palermo and visitors are unlikely to happen across the site by accident. This was highlighted by one respondent:

There are no buses or shuttles. Inaccessible! P49 (55–59-year-old, female from Italy).

Travel guides (e.g. Lonely Planet Citation2023; Piombino-Mascali and Franco Citation2016) and cruise operators (e.g. Costa Cruises Citation2021; Princess Citation2020), alongside online articles and videos, advertise the catacombs as a tourist attraction and are likely to alert tourists to the site’s existence. While tour operators do run trips to the catacombs, they provide limited information about what to expect, as demonstrated by one respondent:

Who are these people? Why are they [the mummies] there to be looked at? But this is mostly my fault for not looking into it before (many places are visited during our cruise). P8 (40–44-year-old, female from The Netherlands).

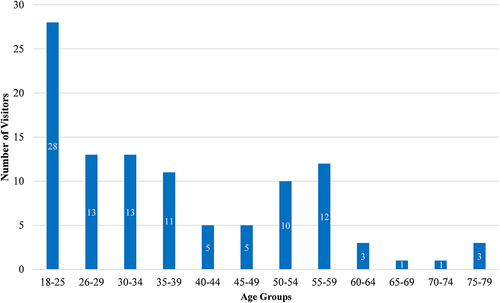

The age distribution of guests was skewed towards younger visitors (). Individuals aged between 18–25 years formed the highest number of respondents (n = 28; 26.7%), followed by both 20-24- and 26–29-year-olds (n = 13; 12.4%). The primary reason for smaller numbers of older individuals in the study sample is because they were often part of a large tour group meaning they did not have time to complete the questionnaire following their visit. The gender of respondents was a relatively even split of females (n = 50; 47.6%) and males (n = 54; 51.4%), with one (1.0%) transgender visitor. The relatively high number of female visitors suggests that warnings, as seen on TripAdvisor for example, stating that this demographic group should stay away from the catacombs due to the presence of young mummies have been ignored (Squires and Piombino-Mascali Citation2021) or were not seen by guests. In the present study there were no specific comments alerting females of the presence of children, though two visitors felt warnings about the Children’s Room were needed:

I found the infant and baby section ok, but there should be a notice up to expect this.P15 (55–59-year-old, female from Germany)

… Warn about the presence of neonates prior to entering.P85 (50–54-year-old, female from Italy).

Respondents aged 60–79 years, and males were more likely to say that if they had known about the Children’s Room they would have avoided it, while females stated they would be less likely to visit the catacombs if they had prior knowledge that non-adult mummies were on display. It should be noted that respondent numbers were small in these demographic groupings and should be interpreted with caution. Overall, only 15 (14.9%) respondents stated they would avoid the Children’s Room had they known about it; this is in stark contrast with the 86 (85.1%) visitors who would not have avoided it. Comments illustrate a range of feelings towards this area of the catacombs, though negative remarks were rare.

It was available so I did not avoid them, but I was surprised since I did not expect to see children.P27 (18–25-year-old, female from Italy).

I think it is not right, but I am also interested in seeing this. Maybe that’s a bit of a paradox.P40 (26–29-year-old, male from Germany).

It is part of our cultural history.P78 (55–59-year-old, female from Italy).

Whether you like it or not, it is part of the experience.P99 (30–34-year-old, male from Spain).

You need to be prepared to see any type of mummies. It is also part of the ‘morbid fascination’.P100 (30–34-year-old, female from Ireland).

On the whole, there is a lack of evidence to suggest that concerns about the display of non-adults are held by a specific demographic group. Regardless, it is clear from the comments provided that individuals have a strong emotional response when faced with the mummified and skeletonised remains of the youngest members of society which may be long-lasting after they leave the site (Biers Citation2019; Quorum Citation2019; Suchy Citation2006).

Prior knowledge of the Capuchin Catacombs

Antón et al. (Citation2018) have highlighted that visitors to museums who have prior knowledge and understanding of the displays are able to interact and participate to a greater extent than those that do not. Indeed, this may be applicable to the Capuchin Catacombs. Visitors were thus asked whether they had conducted research about the catacombs prior to their excursion. This question was posed as the preliminary study by Squires and Piombino-Mascali (Citation2021) highlighted that if visitors had not carried out research before visiting the site, it is unlikely that they would know the catacombs contained the mummified remains of children. This, in part, may be due to the lack of available official resources, as one respondent exclaimed:

I didn’t know where to find information.P63 (18–25-year-old, female from Italy).

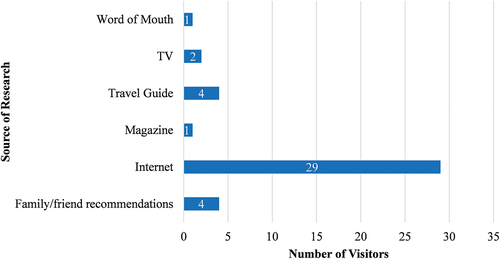

In the present study, only 37 (35.2%) respondents carried out research before visiting the site. Of those who responded to this question, 33 respondents provided additional information about where they found information about the catacombs. Some respondents (n = 5) used more than one source of information before visiting. The most common resource used was the internet (n = 29; 72.5%), followed by both travel guides and recommendations from family or friends (n = 4; 10%; ). Where specified, ‘Google’ (n = 7), the Capuchin Catacomb webpages (Sito ufficiale delle Catacombe Frati Cappuccini Palermo Citation2022; Palermo Catacombs Citationn.d.; n = 5), Wikipedia (Citation2023; n = 4), and travel blogs (e.g. Along Dusty Roads Citation2023; n = 1) were most widely utilised when planning their trip to the site. Interestingly, TripAdvisor was not mentioned despite being ‘the world’s largest travel platform’ (TripAdvisor Citation2023). This may indicate that visitors were looking at more objective sources of information to learn about the catacombs, rather than subjective reviews.

Of the 37 respondents who conducted research before visiting the Capuchin Catacombs, 17 (45.9%) visitors felt there was sufficient available information about the site, three (8.1%) identified there to be minimal amounts of information, seven (18.9%) individuals did not think there was enough information, while 10 (27.0%) visitors did not respond to this question. One respondent made an important point when asked if there was enough information:

No, but only because my research was quite superficial as I hadn’t initially planned to visit the site.P45 (30–34-year-old, male from Belgium).

Even though official tourist literature about the catacombs is scant, visitors who spent more time researching and preparing for their visit are likely to have recovered more visitor information than those who spent less time searching. Research has highlighted the importance of an online presence for heritage sites (e.g. Lo Presti and Carli Citation2021; Permatasari, Adukaite, and Cantoni Citation2016; Zarezadeh and Gretzel Citation2020) and the positive impact prior research can have on destination satisfaction (e.g. Castañeda, Frías, and Rodríguez Citation2007; Xiang et al. Citation2014). By improving online communication and promotion of the catacombs, it is possible to widen access and raise awareness of its existence, improve visitor experience upon arrival, and educate those working in travel and tourism which can improve visitor understanding and knowledge of a cultural asset prior to arrival (Permatasari, Adukaite, and Cantoni Citation2016). By curating online content on a website and/or on social media, it will be possible to create a more positive narrative celebrating the culture of the past communities that practiced mummification in Palermo and will improve the image of this site. Furthermore, such resources would be particularly useful when addressing visitor concerns about who these individuals were and how they came to be in the catacombs.

The recent launch of the official Capuchin Catacombs website (Sito ufficiale delle Catacombe Frati Cappuccini Palermo Citation2022) has allowed the site’s caretakers (the Capuchin Friars) to communicate basic visitor information about the catacombs and to answer frequently asked questions. There are also some general details about the demographic groupings that can be found on display alongside information about the mummification process. By launching this website, visitors know what to expect when they visit. There are some photographs on the webpage, though these tend to be overview shots of corridors with some focussing on clothing and coffins (Sito ufficiale delle Catacombe Frati Cappuccini Palermo Citation2022). Further enhancing visitor online resources, such as 3D tours, have been adopted by some heritage bodies, for example the Paris Catacombs (Les Catacombes de Paris Citation2018). Some have championed the use of online videos and 3D virtual reconstructions of catacombs in Italy which encourage long-term conservation of sites (Lo Presti and Carli Citation2021). However, there are concerns around digitisation and the move online from an ethical stance as one must remember that the Capuchin Catacombs are the final resting place of many individuals (Squires and Piombino-Mascali Citation2021, Citation2024). The dead (or surviving family members) consented to their display in the catacombs after death but did not consent to their inclusion in digital reconstructions of the site (Kaufmann and Rühli Citation2010; Schug et al. Citation2020). We will return to the point of consent later in this article.

Visitor attitudes towards the display of non-adult mummies

Respondents were asked whether they were aware of the presence of non-adult mummies in the Capuchin Catacombs. In total 68 (64.8%) visitors knew there were child mummies in the catacombs prior to their visit, 37 (35.2%) did not, and one person did not offer a response. Even though the majority of visitors did not prepare for their visit by way of research, they may have already been aware of the most famous mummy in the Capuchin Catacombs, a young girl called Rosalia Lombardo who is renowned for her outstanding preservation (Gershon Citation2022; Piombino-Mascali Citation2020) and has been featured in popular magazines and television shows, such as National Geographic Magazine (Voices from the Crypt, February 2009) and National Geographic Explorer (Italy’s Mystery Mummies, February 2009) (Piombino-Mascali Citation2020).

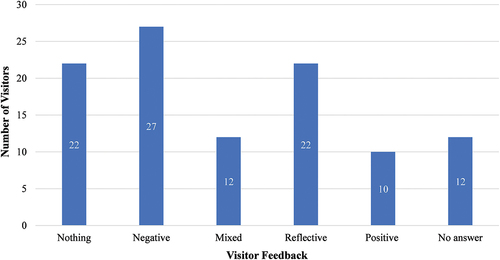

When visitors were asked how non-adult mummies made them feel, respondents provided a variety of feedback ().Footnote3 Of the 105 respondents, 22 (21.0%) felt nothing, while 27 (25.7%) visitors offered negative feedback. Reflective comments were provided by 22 (21.0%) visitors, while 10 (9.5%) respondents wrote positive comments. A total of 12 (11.4%) visitors had conflicting, mixed feelings, and the same number of respondents did not offer any feedback for this question. As shown by the visitor comments below, feedback on the whole was rather mixed, but demonstrated that some visitors had a degree of understanding of the socio-cultural importance of the site and the mummification rite afforded to these non-adults.

Figure 4. Quantification of feedback when visitors were asked how neonate, infant, and child mummies made them feel.

You need to understand the context of time and burial practice, as it was normal back then. I did not feel disgust or other negative feelings.P73 (30–34-year-old, female from Italy).

This is extremely fascinating how they managed to preserve these fragile bodies. They cause sadness because of the fact that they [children] did not manage to live their life.P77 (18–25-year-old, female from Italy).

Thought they [children] looked more ‘religious’, as put into ‘glory’, which was different from the adults.P100 (30–34-year-old, female from Ireland).

There were no clear trends in the data, though it is worth highlighting that of the visitors who responded that they felt ‘nothing’ when looking at the non-adult mummies, five (22.7%) were female and 17 (77.3%) were male. The lack of emotional involvement associated with males when viewing mummified remains has been recorded elsewhere. Day (Citation2005, Citation2006), for instance, recounted examples of visitors making stereotypical jokes and comments about mummies. Much research has been undertaken that explores the use of humour in stressful situations (e.g. Craun and Bourke Citation2014; Grandi et al. Citation2021; Scott Citation2007). In this case, relief theory is particularly pertinent as it would appear that visitors are using humour and laughter as a release of nervous energy (Meyer Citation2000). Likewise, the lack of outward emotive involvement may be a coping mechanism when dealing with complex emotions or the inability to express how they feel when viewing the bodies of young individuals (Saroglou and Anciaux Citation2004). There were no instances of joking or inappropriate behaviour in the questionnaires distributed to visitors to the Capuchin Catacombs, but this has been observed by two of the authors (KS and DP-M) when working at the site. Clear explanations regarding who these children were and why they were mummified will undoubtedly humanise mummies in the Children’s Room and improve visitor behaviour.

The state of preservation and chronological age of the non-adult mummies was also raised by visitors. This appears to play a part in the emotional response to individuals on display.

I felt different according to state of mummification. More connection to ones that were less skeletal. Human features and greater emotion.P21 (35–39-year-old, male from the UK).

Considering that they are very old, this does not create problems for me.P67 (18–25-year-old, female from Italy).

The mummified children in the catacombs don a range of outfits, which gives a sense of personhood and connection to the deceased (Robb Citation2009). Nevertheless, visitors may feel more disconnected with those that exhibit advanced stages of decomposition (Sutton-Butler et al. Citation2023). In some cases, partially skeletonised remains may be viewed by visitors as less human, a scientific study object, or fake (Day Citation2006). Day (Citation2006) highlights that visitors can have stronger visceral feelings when faced with older, poorly preserved mummies due to visual decay which can be associated with pollution and dilapidation. In contrast, Quorum (Citation2019) reports a less complete adolescent mummy which members of a focus group felt had endured a traumatic episode, though this did not deter them from viewing this individual. It would thus appear that while poor preservation may remove an aspect of human connection between visitor and mummy, it does not entirely deter guests from viewing them.

Only 10 (9.5%) respondents had positive feelings (e.g. interest, curiosity, fascination) when viewing the non-adult mummies in the Capuchin Catacombs. This is a rather low figure when compared to feedback from museum visitor feedback elsewhere. In Turkey, 83.3% of 780 visitors felt ‘interested or curious’ when viewing human remains (of both non-adults and adults) in museums (Doğan, Thys-Şenocak, and Joy Citation2021). The disparity between the two studies could be explained by the fact that the question posed in our questionnaire focused on children which could have impacted upon the feelings of respondents. In the present study, it is possible that the way in which non-adult remains are displayed could affect how visitors feel towards them. In the catacombs, visitors are faced with hundreds of mummified bodies with little context. However, in museums, mummified remains on display are carefully selected to be the best preserved, they are fewer in number, and are typically not the only ‘attraction’ in an exhibition. Furthermore, non-adult remains are rarely displayed, and information panels or labels typically accompany each exhibit. One visitor to the catacombs felt:

[T]he exhibition could be improved with more details and protective glass.P88 (18–25-year-old female from Italy).

It must be remembered that the site is a catacomb and not a museum where one would expect human remains to be housed in glass cases. Brooks and Rumsey (Citation2008) highlight that glass cases act as an additional barrier between the living and the dead and can cause the deceased to appear almost unlike real human remains. Indeed, Jody Joy (Citation2014) states that the display of four bog bodies in clear glass displays in the National Museum of Ireland gives the remains a ‘forensic’ or ‘neutral’ appearance. This is particularly apparent when one compares mummified remains that are placed behind glass and those that have been left in their original resting place. The 17th-18th-century C.E. Klatovy Catacombs in Czechia are a good example of this. Due to deteriorating environmental conditions, the remaining 38 mummified individuals from an original assemblage of decedents belonging to the Jesuit order, local nobility, and burghers were placed in new coffins which had been fitted with glass lids (Klatovské Katakomby Citationn.d.). This offers a very different experience to catacombs whereby the mummified remains are not encased in any way, for instance, the Capuchin Catacombs in Palermo and the Capuchin Crypt in Brno (Czechia). Even though the mummies remain in the Klatovy Catacombs, and have not been moved to a museum, the displays are more neutral as curators and conservators have moved the dead from their original context to new encased coffins and have made decisions on the arrangement of the coffins that differ from those originally responsible for the display of the dead (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett Citation1998). Placing all individuals in glass cases is unfeasible in the case of Capuchin Catacombs due to the cost and the fact that this would turn the final resting place of many of Palermo’s inhabitants into a museum, which would dramatically change both the nature and the authenticity of the site. This in turn would result in a completely different visitor experience to what is currently available.

Of the visitors who had done research about the catacombs prior to their visit (n = 37; 35%), 84% (n = 31) were aware that the site contained the mummies of neonates, infants, and children. This compares with 55% (n = 37) of those who had not done any previous research but were still conscious that the catacombs contained non-adult mummies. Of the visitors who were aware of mummies belonging to this demographic group, 91% (n = 60) thought it was appropriate to display them in the catacombs, while this figure fell to 74% (n = 26) for visitors who were not previously aware of their presence. There was a statistically significant difference between these two figures, X2 (df = 1, n = 101) = 3.77, p = 0.052, possibly suggesting that prior knowledge and understanding of mummification and the purpose of catacombs was important in shaping visitor opinions of non-adult displays. In contrast, prior awareness of the non-adult mummies did not notably affect views on whether it was appropriate to display non-adult mummies in museums, as 84% (n = 27) of those who were aware of child mummies and 83% (n = 53) of those who were not previously aware said it was appropriate, which may be the result of visitors being more familiar with the display of non-adult remains in museums.

When reviewing all questionnaire responses, the majority of visitors believed it was appropriate to display non-adult remains in both catacombs and museums (catacombs: n = 86, 85.1%; museums: n = 81, 83.5%). Pearson residuals tests showed some increased association between holding a master’s degree and the likelihood of the respondent stating that it is appropriate to display non-adult mummies in catacombs. These findings may indicate that respondents believe catacombs are appropriate places to house the dead, possibly because the deceased and/or kin consented to their display in this manner; this is in stark contrast to the display of human remains in museums where consent is rarely obtained (Alberti et al. Citation2009; Doğan, Thys-Şenocak, and Joy Citation2021; Holm Citation2001; Squires and Piombino-Mascali Citation2021). Several visitors address consent in their responses.

… Is that appropriate? I’m not sure if it is if there was no prior consent.P8 (40–44-year-old, female from The Netherlands).

It’s very interesting for me. It is part of life - it only can be disrespectful for the dead people inside the catacombs. But they gave their consent.P31 (18–25-year-old, female from Germany).

I think it would be appropriate, if the person that is shown had agreed to it when he/she was alive, but that is difficult with children.P39 (18–25-year-old, female from Germany).

There are complexities with regard to the consent of children in this mortuary rite. In modern Palermo (1599–1880 C.E.), when mummification was practiced, society had a patriarchal structure, and it was the father who normally made decisions for the rest of the family (Sindoni Citation2017). Therefore, it is likely that the deceased’s kin permitted this funerary treatment. Despite the fact that consent was granted, associated names, or even biographical information, are at times no longer available as many of the tags that were originally associated with the bodies have been lost or degraded. Furthermore, death records that are held in the Capuchin Convent’s library are of limited use. These registers list names of the deceased, year of death, and in some cases whether the deceased was afforded anthropogenic mummification. However, it is not always possible to marry up this information with each of the individuals on display as there is no precise indication of where these individuals were displayed, what they were wearing, or any other identifiable information. Furthermore, some mummies have been moved around over time and are unlikely to be in the location they were initially placed. In the present study, the ‘Children’s Room’ was focused upon and there were no names associated with the mummies in this part of the catacombs due to the fact that their tags have been lost over time.

Even though 59 (60.8%) respondents felt the catacombs should be open to visitors of all ages, and 38 (39.2%) visitors felt it should be restricted, it was apparent that younger respondents were slightly more likely to say that the catacombs should not be open to all ages. Feedback for this question varied, with respondents feeling younger visitors needed to be aware that death is part of life, while others felt they were not emotionally developed to deal with the sight of mummified juveniles, and may even be noisy and disrespectful; the latter point has been raised in other contexts (Day Citation2006; Moore and Mackenzie Brown Citation2007). However, children learn about mummies (particularly from Ancient Egypt) at school and are widely exposed to mummies in popular culture (Day Citation2006, Citation2014). TripAdvisor comments have also shown that young children have found the non-adult mummies in the Capuchin Catacombs to be interesting (Squires and Piombino-Mascali Citation2021). This in part can be attributed to educating children about the mummies before visiting the site, as well as ‘gamifying’ the experience (e.g. children guessing the age of mummified neonates); a method seen elsewhere when teaching children about mummification (Day Citation2006). Interestingly, Doğan, Thys-Şenocak, and Joy (Citation2021) reported that student groups were frequently the most engaged when visiting mummy displays, while children visiting the Body Worlds exhibition offered positive feedback about the foetus exhibition (Moore and Mackenzie Brown Citation2007). Ultimately, if children are prepared before the visit, they can greatly benefit from visiting the mummified non-adults in the Capuchin Catacombs as they offer a glimpse into childhood and child mortality in the past.

When visitors were asked what they had learnt about the mummified children during their visit, 27 (25.7%) respondents reported that they learned very little or nothing at all. This was largely due to the lack of information panels, audio guides, and tour guides. Yet those that did offer reflective comments addressed one’s own mortality (n = 7), the death of individuals before their time (n = 4), mummification and preservation (n = 3), and the love and respect towards children through this funerary rite (n = 3). Other researchers have identified similar themes when museum visitors have been asked about the display of juvenile human remains (Hall Citation2013; Moore and Mackenzie Brown Citation2007; Randi Korn and Associates, Inc. Citation1999). A large proportion of respondents (n = 47; 44.8%) in the present study did not provide an answer when asked what they had learnt about mummified children. It is difficult to know why responses were not offered for this question. Respondents may have felt uncomfortable answering this question, particularly if they had a negative experience and/or had not learned anything (in part due to the dearth of information in the catacombs), or they may have been suffering from survey fatigue given that this question was asked towards the end of the questionnaire (Aransiola Citation2023; Brace Citation2013).

Information at the site

When visitors were asked whether they felt there were sufficient visitor resources and information panels about the mummies throughout the Capuchin Catacombs, 73 (69.5%) individuals responded ‘no’, 27 (25.7%) answered ‘yes’, while five (4.8%) did not answer the question. Interestingly, 122 (12.1%) TripAdvisor comments mentioned the lack of information at the site (Squires and Piombino-Mascali Citation2021). It could be argued that this figure is much smaller than the present study’s questionnaire responses as reviewers were not explicitly asked to provide feedback on the amount of available visitor information and there was likely a delay between the time of the visit and publication of reviews (Song et al. Citation2019). It is worth highlighting that there are no audio guides or leaflets available, and there are very few information panels in the catacombs. There are some resources, which include a photo guidebook published in different languages and costs 20 euros, that can be bought at the entrance of the catacombs (Cenzi and Vannini Citation2014), though the aforementioned book is missed by some visitors:

What was the point [of mummification and display of individuals]? What was the meaning of all that? Not a trifle word and not even a single book to explain. Why is this found? Why here? Who decided these people were ok with being mummified? Panels?P2 (75–79-year-old, male from France).

Many visitors wanted context to accompany the deceased as evidenced from a number of responses.

If background information to the mummies is accessible it would be great to read about it, since every single mummy once was a human being with its own life story.P30 (18–25-year-old, male from Germany).

I was thinking about the lack of information throughout the whole visit. There should be a lot more information to give context.P40 (26–29-year-old, male from Germany).

… [T]his is just a skull exhibition. Tell their story!P94(35–39-year-old, female from Italy).

I’d like more explanations’. (e.g. mummification process, elements to recognise professions or times of death, such as clothing uses …).P101 (30–34-year-old, male from Germany).

Some further simplified information (given the sacredness of the place) could more fully give a value to the uniqueness of the site.P105 (40–44-year-old, male from Italy).

Two respondents made stark comments about the lack of available information in the Capuchin Catacombs:

There needs to be more educational focus to the catacombs - at the moment they feel more sensational than educational.P24 (26–29-year-old, female from the UK).

The visit was more like an attraction. I regret the creep show effect of the visit.P48 (30–34-year-old, male from Belgium).

The lack of context within the catacombs removes the cultural and societal importance of the site. The introduction of an entrance fee to the Capuchin Catacombs (which has recently been increased from three euros to five euros in 2023) has led to a fundamental shift in the way in which the dead are viewed by the living (Polzer Citation2019). It could be argued that the site has transformed from its original purpose as catacombs and a place to worship the ancestors to a heritage site of interest in its own rite with the primary purpose of entertaining visitors and generating revenue (Polzer Citation2018, Citation2019). However, this should not be a profitable business as such. All funds should either be used for upgrading and maintaining the catacombs or contributing to the Capuchin Brothers’ charity work. To date, this revenue stream has yet to be used for the purpose of adding signage and further information throughout the site. Visitor questionnaires from other contexts have also highlighted the desire for more information about human remains that are on display. For example, some visitors to the Body World exhibition felt there was insufficient information about the human remains on display and the lack of conceptual goals of the exhibition led some to believe that the financial success of the installation was a priority to its organisers (Leiberich et al. Citation2006). Meanwhile, Korn and Associates, Inc. (Citation1999) reported that visitors would have found a display of foetuses at the National Museum of Health and Medicine (Washington, DC) less disturbing if there were associated information panels. Wilson (Citation2015) highlights the importance of supplemental information in the display of foetal and juvenile human remains as it advances visitor knowledge about collections and promotes transparency and confidence in the legitimacy of institutions curating the remains of children. Nonetheless, one must remember that the Capuchin Catacombs are just that – they are catacombs and not a museum. It could be argued that the installation of information panels and incorporation of digital heritage (Burlingame Citation2022) may distract visitors from fully experiencing and immersing themselves at the site. This approach makes the Capuchin Catacombs an ‘experience-based’ site rather than an ‘information-based’ exhibition, which is more typical of museums (Tzortzi Citation2018). That being said, a balance needs to be struck. The catacombs need to retain the emotive nature of the site while simultaneously offering some text panels to guide the visitors on their journey through the catacombs.

There were very few associations between demographic groupings and whether there was sufficient information in the catacombs, bar the home country group and education level. Sample sizes in these analyses were small, so we must be cautious when interpreting these findings. However, some general trends emerged. Respondents from France, Germany, and Austria were more likely to stipulate that there was enough information. Differential feedback may, in part, be the result of socio-cultural factors of the home countries in which individuals grew up and inhabit. Indeed, Wang and Kirilenko (Citation2021) identify that tourists from different countries or regions interpret travel experiences differently. Pearson residuals revealed an even stronger association between education level and whether there was sufficient information. In total, 60% (n = 6) of those with ‘some high school’ education said there was sufficient information, compared to most of the other education groups where the percentage was 26% or lower. It is possible that these visitors may have also taken the view that this was a site where minimal information was needed and was designed to be experienced rather than be treated like a museum. Likewise, motivations for visiting the site for educational and/or entertainment purposes may have influenced their desire for further information. Falk et al. (Citation1998) highlight that those visiting exhibitions with high education motivations have a greater desire for conceptual information (e.g. information panels) than those with high entertainment motivations, who placed greater emphasis and focus on the artefacts on display.

A chi-square test revealed that visitors who had conducted research prior to their visit were more likely to say there was sufficient information in the Capuchin Catacombs compared to those who had not done any previous research, X2 (df = 1, n = 104) = 4.04, p = 0.044. This possibly suggests that research and preparation prior to visiting the catacombs equipped visitors with knowledge of the site, meaning less information was needed during their visit. Research has shown that visitors to heritage institutions can greatly benefit from using online resources both before and during their visit, as they encourage active engagement with displays (Collins, Mulholland, and Zdrahal Citation2008; Hughes and Moscardo Citation2017; Marty Citation2007, Citation2008; Sheng and Chen Citation2012). The official Capuchin Catacombs website (Sito ufficiale delle Catacombe Frati Cappuccini Palermo Citation2022) offers useful information about the mummies, mummification process, and history of the site. The promotion of this resource by tour operators and the Department of Tourism, Sport and Entertainment would not only benefit the catacombs, as it would increase the site’s visibility to potential visitors, but tourists would be more aware of this source of information and could be better prepared for their visit. Falk et al. (Citation1998) highlight that visitor experience is strongly influenced by prior experiences and knowledge. By improving promotion and dissemination of information about the Capuchin Catacombs, visitors will get the most out of their visit to the site.

Conclusion

The principal aim of this research was to better understand visitor perspectives of non-adult mummies in the Capuchin Catacombs and the visitor information available to them. After distributing questionnaires to 105 visitors, no clear-cut patterns emerged in relation to demographic groupings. In some cases, there were slightly stronger associations between certain groups and questions posed, but these were not statistically significant and, in some cases, occurred in small numbers rendering them not wholly reliable. However, some of the key themes that have been addressed in previous studies of heritage sites and museums where children have been displayed (e.g. Biers Citation2019; Hall Citation2013; Korn and Associates Citation1999; Moore and Mackenzie Brown Citation2007; Squires and Piombino-Mascali Citation2021) were repeated in this study. Whilst numerous individuals found the display of children to be interesting and allowed reflection, some visitors raised concerns that there was no warning ahead of the Children’s Room, meaning they could not prepare themselves for the high concentration of neonates, infants, and juveniles. This is an increasingly common practice in museums and could potentially be extended to other types of heritage sites where the human remains of non-adults are on display, such as the Capuchin Catacombs. Visitors queried whether these young individuals, or their families, had consented to displaying their bodies after death. This question could be answered by incorporating an information panel at the entrance of the catacombs. The inclusion of some information panels may be beneficial to visitors, particularly those who know nothing of the site upon arrival. This will put into context why children were mummified and emphasise the socio-cultural importance of this practice in Palermo.

This research was conducted as part of a larger study focusing on the health, development, and funerary rites afforded to non-adults in late modern Palermo. As part of this project, a tourist information leaflet detailing child mortality in modern Palermo, pathology, and the lives and deaths of these young individuals will be created. There will be a QR code on the reverse of the leaflet where visitor feedback can be shared with the research team which can, in turn, be passed on to the Capuchin Friars with the hope of further improving the dissemination of information to visitors while not taking away how the non-adult mummies were intended to be displayed.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Capuchin Friars, the Superintendence for the Cultural and Environmental Heritage of Palermo, and the Department of Cultural Heritage and Sicilian Identity for their continued input and support of our research. We would also like to thank the 105 questionnaire respondents for participating in this project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kirsty Squires

Kirsty Squires is an Associate Professor of Bioarchaeology and MSc Forensic Science course leader at Staffordshire University. She is the principal investigator of an Arts and Humanities Research Council funded project that explores the health, development, and social identity of children afforded mummification in the Capuchin Catacombs (Palermo, Sicily). Her research interests include: the archaeology of childhood, funerary archaeology, ethics in bioarchaeology and forensic anthropology, and the analysis and interpretation of cremated bone from archaeological and forensic contexts.

Alison Davidson

Alison Davidson is a Technical Specialist in Analytical Chemistry at Staffordshire University. Her research interests range from the analysis of fragrances to the chemistry of taphonomy and the burial environment. She contributes and supports a range of research projects that require data analysis and statistical testing. She is currently undertaking an MSc in Applied Statistics at the University of Sheffield.

Dario Piombino-Mascali

Dario Piombino-Mascali is a Chief Researcher in Human Biology at Vilnius University, and an Adjunct Professor at the Specializing School in Archaeological Heritage of the University of Salento. He is also a National Geographic Explorer and a Visiting Fellow of Cranfield University, as well as an Erasmus+ Scholar at the University of Coimbra. He specializes in the bioarchaeology of mummified human remains.

Notes

1. Exceptions to the rule include Rosalia Lombardo, a twentieth-century child in the Capuchin Catacombs, Italy (Panzer et al. Citation2013; Piombino-Mascali Citation2020; Piombino-Mascali and Zink Citation2023) and three eighteenth-century mummies from a museum in Vác, Hungary (Csukovits and Forró Citation2024).

2. Catacombs is a term derived from early Christian burials, which is sometimes inappropriately given to other, more recent subterranean structures or crypts. In many of these catacombs, historic human remains have been removed from display (e.g. crypt of the Dominican Church, Vác, Hungary). Elsewhere, skeletal remains are displayed by element type and are sometimes presented in decorative formations (e.g. Catacombs of Paris, France, Fontanelle Cemetery, Naples, Italy, and ossuary of the Church of Saints Peter and Paul, Mělník, Czechia) or in closed coffins (e.g. crypt of the Evangelical Reformed Church of Kėdainiai, Lithuania). Spontaneous-enhanced mummification and the continued display of mummies in catacombs is a unique practice in southern Italy rarely seen elsewhere (Cardin Citation2015; Fornaciari Citation1998).

3. Feedback was categorised into five main groupings: felt nothing (e.g. no specific feeling or unable to describe how they felt); negative feedback (e.g. felt sick, strange, shocked, unnerved, uncomfortable, sadness); reflective (e.g. humble, compassion, emotional, felt moved); positive feedback (e.g. interesting, fascinating, curiosity); mixed feelings (e.g. negative, reflective, and/or positive feelings).

References

- Alberti, S. J. M. M., P. Bienkowski, M. J. Chapman, and R. Drew. 2009. “Should We Display the Dead?” Museum & Society 7 (3): 133–149.

- Along Dusty Roads. 2023. “13 Wonderful Things to Do in Palermo | a City Break Guide.” Along Dusty Roads. https://www.alongdustyroads.com/posts/things-to-do-in-palermo.

- Antón, C., C. Camarero, and M.-J. Garrido. 2018. “Exploring the Experience Value of Museum Visitors as a Co-Creation Process.” Current Issues in Tourism 21 (12): 1406–1425. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2017.1373753.

- Aransiola, O. J. 2023. “What Is Survey Dropout Analysis?” Formplus. https://www.formpl.us/blog/what-is-survey-dropout-analysis.

- Biers, T. 2019. “Rethinking Purpose, Protocol, and Popularity in Displaying the Dead in Museums.” In Ethical Approaches to Human Remains: A Global Challenge in Bioarchaeology and Forensic Anthropology, edited by K. Squires, D. Errickson, and N. Márquez-Grant, 239–263. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Blanco, M.-J., and R. Vidal. 2014. “Introduction.” In The Power of Death: Contemporary Reflections on Death in Western Society, edited by M.-J. Blanco and R. Vidal, 1–9. New York, NY: Berghahn.

- Bonney, H., J. Bekvalac, and C. Phillips. 2019. “Human Remains in Museum Collections in the United Kingdom.” In Ethical Approaches to Human Remains: A Global Challenge in Bioarchaeology and Forensic Anthropology, edited by K. Squires, D. Errickson, and N. Márquez-Grant, 211–237. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Brace, I. 2013. Questionnaire Design. How to Plan, Structure and Write Survey Material for Effective Market Research. 3rd ed. London, UK: KoganPage.

- Brooks, M. M., and C. Rumsey. 2008. “The Body in the Museum.” In Human Remains: Guide for Museums and Academic Institutions, edited by V. Cassman, N. Odegaard, and J. Powell, 261–289. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press.

- Burlingame, K. 2022. “High Tech or High Touch? Heritage Encounters and the Power of Presence.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 28 (11–12): 1228–1241. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2022.2138504.

- Cardin, M., edited by 2015. Mummies around the World: An Encyclopedia of Mummies in History, Religion, and Popular Culture. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-Clio.

- Castañeda, J. A., D. M. Frías, and M. A. Rodríguez. 2007. “The Influence of the Internet on Destination Satisfaction.” Internet Research 17 (4): 402–420. https://doi.org/10.1108/10662240710828067.

- Cenzi, I., and C. Vannini. 2014. La veglia eterna: Catacombe dei Cappuccini di Palermo. Modena, Italy: Logos.

- Chamberlain, A. T., and M. Parker Pearson. 2001. Earthly Remains: The History and Science of Preserved Human Bodies. London, UK: The British Museum Press.

- Collins, T. D., P. Mulholland, and Z. Zdrahal. 2008. “Using Mobile Phones to Map Online Community Resources to a Physical Museum Space.” International Journal of Web Based Communities 5 (1): 18–32. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJWBC.2009.021559.

- Costa Cruises.2021. Mysteries of Palermo. https://www.costacruises.eu/excursions/02/0242.html.

- Craun, S. W., and M. L. Bourke. 2014. “The Use of Humor to Cope with Secondary Traumatic Stress.” Journal of Child Sexual Abuse 23 (7): 840–852. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2014.949395.

- Csukovits, A., and K. Forró. 2024. “Memento Mori Exhibition from the Dominican Crypt, Vác (Március 15 Square, 19), Hungary.” In The Routledge Handbook of Museums, Heritage, and Death, edited by T. Biers and K. S. Clary, 443–455. London, UK: Routledge.

- Day, J. 2005. ““Mummymania”: Mummies, Museums and Popular Culture.” Journal of Biological Research - Bollettino della Società Italiana di Biologia Sperimentale 80 (1): 296–300. https://doi.org/10.4081/jbr.2005.10226.

- Day, J. 2006. The Mummy’s Curse: Mummymania in the English-Speaking World. London, UK: Routledge.

- Day, J. 2014. “‘Thinking Makes it So’: Reflections on the Ethics of Displaying Egyptian Mummies.” Papers on Anthropology 23 (1): 29–44. https://doi.org/10.12697/poa.2014.23.1.03.

- Doğan, E., L. Thys-Şenocak, and J. Joy. 2021. “Who Owns the Dead? Legal and Professional Challenges Facing Human Remains Management in Turkey.” Public Archaeology 20 (1–4): 85–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/14655187.2022.2070209.

- Falk, J. H., T. Moussouri, and D. Coulson. 1998. “The Effect of Visitors’ Agendas on Museum Learning.” Curator the Museum Journal 41 (2): 77–144. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2151-6952.1998.tb00822.x.

- Fornaciari, G. 1998. “Italian Mummies.” In Mummies, Disease and Ancient Cultures, edited by A. Cockburn, E. Cockburn, and T. A. Reyman, 266–281. 2nd ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Gershon, L. 2022. “Researchers Are Using X-Rays to Solve the Mystery Behind Sicily’s Child Mummies.” Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/researchers-study-sicilian-child-mummies-180979386/.

- Grandi, A., G. Guidetti, D. Converso, N. Bosco, and L. Colombo. 2021. “I Nearly Died Laughing: Humor in Funeral Industry Operators.” Current Psychology 40 (12): 6098–6109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00547-9.

- Hall, M. A. 2013. “The Quick and the Deid: A Scottish Perspective on Caring for Human Remains at the Perth Museum and Art Gallery.” In Curating Human Remains: Caring for the Dead in the United Kingdom, edited by M. Giesen, 75–86. Woodbridge, UK: The Boydell Press.

- Holm, S. 2001. “The Privacy of Tutankhamen – Utilising the Genetic Information in Stored Tissue Samples.” Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics 22 (5): 437–449. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1013010918460.

- Hughes, K., and G. Moscardo. 2017. “Connecting with New Audiences: Exploring the Impact of Mobile Communication Devices on the Experiences of Young Adults in Museums.” Visitor Studies 20 (1): 33–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10645578.2017.1297128.

- Joy, J. 2014. “Looking Death in the Face. Different Attitudes Towards Bog Bodies and Their Display with a Focus on Lindow Man.” In Regarding the Dead: Human Remains in the British Museum, edited by A. Fletcher, D. Antoine, and J. Hill, 10–19. London, UK: The British Museum Press.

- Kaufmann, I. M., and F. J. Rühli. 2010. “Without ‘Informed Consent’? Ethics and Ancient Mummy Research.” Journal of Medical Ethics 36 (10): 608–613. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2010.036608.

- Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, B. 1998. Destination Culture. Tourism, Museums, and Heritage. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

- Klatovské Katakomby. n.d. Klatovské Katakomby. http://www.katakomby.cz/.

- Leeds Museums and Galleries. 2018. Visitor Responses to Human Remains in Leeds City Museum. Final Report. Leeds, UK: Leeds Museums and Galleries.

- Leiberich, P., T. Loew, K. Tritt, C. Lahmann, and M. Nickel. 2006. “Body Worlds Exhibition—Visitor Attitudes and Emotions.” Annals of Anatomy 188 (6): 567–573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aanat.2006.03.005.

- Les Catacombes de Paris. 2018. Les Catacombes de Paris. https://www.catacombes.paris.fr/en.

- Licata, M., A. Bonsignore, R. Boano, F. Monza, E. Fulcheri, and R. Ciliberti. 2020. “Study, Conservation and Exhibition of Human Remains: The Need of a Bioethical Perspective.” Acta Biomedica 91 (4): e2020110. https://doi.org/10.23750/abm.v91i4.9674.

- Lonely Planet. 2023. “Catacombe dei Cappuccini.” Lonely Planet. https://www.lonelyplanet.com/italy/sicily/palermo/attractions/catacombe-dei-cappuccini/a/poi-sig/1137512/360009.

- Lo Presti, O., and M. R. Carli. 2021. “Italian Catacombs and Their Digital Presence for Underground Heritage Sustainability.” Sustainability 13 (21): 12010. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112010.

- Marty, P. F. 2007. “Museum Websites and Museum Visitors: Before and After the Museum Visit.” Museum Management & Curatorship 22 (4): 337–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/09647770701757708.

- Marty, P. F. 2008. “Museum Websites and Museum Visitors: Digital Museum Resources and Their Use.” Museum Management & Curatorship 23 (1): 81–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/09647770701865410.

- Mather, J. 2024. “From Trauma to Tourism: Balancing the Needs of the Living and the Dead.” In The Routledge Handbook of Museums, Heritage, and Death, edited by T. Biers and K. S. Clary, 292–305. London, UK: Routledge.

- Meyer, J. C. 2000. “Humor As a Double-Edged Sword: Four Functions of Humor in Communication.” Communication Theory 10 (2): 310–331. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2000.tb00194.x.

- Moore, C. M., and C. Mackenzie Brown. 2007. “Experiencing Body Worlds: Voyeurism, Education, or Enlightenment?” Journal of Medical Humanities 28 (4): 231–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-007-9042-0.

- Nilsson Stutz, L. 2023. “Between Objects of Science and Lived Lives. The Legal Liminality of Old Human Remains in Museums and Research.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 29 (10): 1061–1074. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2023.2234350.

- Palermo Catacombs. n.d. The Capuchin Catacombs. http://www.palermocatacombs.com.

- Panzer, S., H. Gill-Frerking, W. Rosendahl, A. R. Zink, and D. Piombino-Mascali. 2013. “Multidetector CT Investigation of the Mummy of Rosalia Lombardo (1918–1920).” Annals of Anatomy 195 (5): 401–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aanat.2013.03.009.

- Permatasari, P. A., A. Adukaite, and L. Cantoni. 2016. The Online Presence of UNESCO World Heritage Sites in East, South, and South East Asia. Lugano, Switzerland: UNESCO.

- Piombino-Mascali, D. 2018. Le Catacombe dei Cappuccini. Guida storico-scientifica. Palermo, Italy: Kalós.

- Piombino-Mascali, D. 2020. Lo spazio di un mattino. Storia di Rosalia Lombardo, la bambina che dorme da cento anni. Palermo, Italy: Dario Flaccovio.

- Piombino-Mascali, D., and A. Franco. 2016. Catacombe dei Cappuccini. https://izi.travel/it/acd4-catacombe-dei-cappuccini/it#2ac4-il-progetto-mummie-siciliane/it.

- Piombino-Mascali, D., and C. N. Kenneth. 2020. “Natural Mummification As a Non-Normative Mortuary Custom of Modern Period Sicily (1600-1800).” In The Odd, the Unusual, and the Strange. Bioarchaeological Explorations of Atypical Burials, edited by T. K. Betsinger, A. B. Scott, and A. Tsaliki, 312–322. Gainsville, FL: University of Florida Press.

- Piombino-Mascali, D., F. Maixner, A. R. Zink, S. Marvelli, S. Panzer, and A. C. Aufderheide. 2012. “The Catacomb Mummies of Sicily. A State-Of-The-Art Report (2007-2011).” Antrocom Online Journal of Anthropology 8 (2): 341–352.

- Piombino-Mascali, D., and A. R. Zink. 2023. “Alfredo Salafia’s Handwritten Memoir and the Embalming of Rosalia Lombardo: A Commentary.” Anthropologischer Anzeiger 80 (1): 113–118. https://doi.org/10.1127/anthranz/2022/1630.

- Polzer, N. C. 2018. “Ancestral Bodies to Universal Bodies – the “Re-Enchantment” of the Mummies of the Capuchin Catacombs in Palermo, Sicily.” Cogent Arts & Humanities 5 (1): 1482994. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311983.2018.1482994.

- Polzer, N. C. 2019. “Material Specificity and Cultural Agency: The Mummies of the Capuchin Catacombs in Palermo, Sicily.” Mortality 24 (2): 167–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576275.2019.1585783.

- Princess. 2020. Capuchin Catacombs and Mysteries. https://www.princess.com/ports-excursions/sicily-palermo-italy-excursions/capuchin-catacombs-and-mysteries.

- Quorum. 2019. L’esposizione di resti umani nei musei. Turin, Italy: Museo Egizio.

- Randi Korn and Associates, Inc.1999. Responses to a Human Remains Collection: Findings from Interviews and Focus Groups. Prepared for the National Museum of Health and Medicine. New York, NY: Randi Korn and Associates.

- Redfern, R., and J. Bekvalac. 2013. “The Museum of London: An Overview of Policies and Practice.” In Curating Human Remains: Caring for the Dead in the United Kingdom, edited by M. Giesen, 87–98. Woodbridge, UK: The Boydell Press.

- Robb, J. 2009. “Towards a Critical Ötziography: Inventing Prehistoric Bodies.” In Social Bodies, edited by H. Lambert and M. McDonald, 100–128. New York, NY: Berhahn.

- Saroglou, V., and L. Anciaux. 2004. “Liking Sick Humor: Coping Styles and Religion As Predictors.” Humor - International Journal of Humor Research 17 (3): 257–277. https://doi.org/10.1515/humr.2004.012.

- Schug, G. R., K. Killgrove, A. Atkin, and K. Baron. 2020. “3D Dead: Ethical Considerations in Digital Human Osteology.” Bioarchaeology International 4 (3–4): 217–230. https://doi.org/10.5744/bi.2020.3008.

- Scott, T. 2007. “Expression of Humour by Emergency Personnel Involved in Sudden Deathwork.” Mortality 12 (4): 350–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576270701609766.

- Sheng, C.-W., and M.-C. Chen. 2012. “A Study of Experience Expectations of Museum Visitors.” Tourism Management 33 (1): 53–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.01.023.

- Sindoni, C. 2017. “Families, School and Society in Sicily in the “Long Century”: An Overview.” Quaderni di Intercultura 9:138–150. https://doi.org/10.3271/M54.

- Sito ufficiale delle Catacombe Frati Cappuccini Palermo. 2022. https://www.catacombefraticappuccini.com/it_it/.

- Song, S., H. Kawamura, J. Uchida, and H. Saito. 2019. “Determining Tourist Satisfaction from Travel Reviews.” Information Technology & Tourism 21 (3): 337–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-019-00144-3.

- Squires, K., and D. Piombino-Mascali. 2021. “Ethical Considerations Associated with the Display and Analysis of Juvenile Mummies from the Capuchin Catacombs of Palermo, Sicily.” Public Archaeology 20 (1–4): 66–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/14655187.2021.2024742.

- Squires, K., and D. Piombino-Mascali. 2024. “Striking a Balance: Preserving, Curating, and Investigating Human Remains from the Capuchin Catacombs of Palermo, Sicily.” In The Routledge Handbook of Museums, Heritage, and Death, edited by T. Biers and K. S. Clary, 51–64. London, UK: Routledge.

- Stringer Clary, K. 2018. “Human Remains in Museums Today.” History News 73 (4): 12–19.

- Suchy, S. 2006. “Connection, Recollection, and Museum Missions.” In Museum Philosophy for the Twenty-First Century, edited by H. H. Genoways, 47–58. Lanham, MD: AltaMira.

- Sutton-Butler, A., K. Croucher, P. Garner, K. Bielby-Clarke, and M. Farrow. 2023. “In Jars: The Integration of Historical Anatomical and Pathological Potted Specimens in Undergraduate Education.” Annals of Anatomy 247:152066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aanat.2023.152066.

- Taylor, J. H., and D. Antoine. 2014. Ancient Lives: New Discoveries. Eight Mummies, Eight Stories. London, UK: British Museum Press.

- TripAdvisor. 2023. “About TripAdvisor.” TripAdvisor. https://tripadvisor.mediaroom.com/uk-about-us.

- Tzortzi, K. 2018. “Human Remains, Museum Space and the ‘Poetics of Exhibiting’.” University Museums and Collections 10:23–34.

- Wang, L., and A. P. Kirilenko. 2021. “Do Tourists from Different Countries Interpret Travel Experience with the Same Feeling? Sentiment Analysis of TripAdvisor Reviews.” In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2021: Proceedings of the ENTER 2021 eTourism Conference, January 19-22, 2021, edited by W. Wörndl, C. Koo, and J. L. Stienmetz, 294–301. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Wikipedia. 2023. “Catacombe dei Cappuccini.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catacombe_dei_Cappuccini.

- Wilson, E. K. 2015. “The Collection and Exhibition of a Fetal and Child Skeletal Series.” Museum Anthropology 38 (1): 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/muan.12070.

- Xiang, Z., D. Wong, J. T. O’Leary, and D. R. Fesenmaier. 2014. “Adapting to the Internet: Trends in Travelers’ Use of the Web for Trip Planning.” Journal of Travel Research 54 (4): 511–527. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287514522883.

- Zarezadeh, Z., and U. Gretzel. 2020. “Iranian Heritage Sites on Social Media.” Tourism Analysis 25 (2–3): 345–357. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354220X15758301241855.