Abstract

This article explores dating as/in performance, especially regarding the ‘first date’. It shows that modern data-driven Internet/app dating can seem quite mundane and lead to work-like 'burnout', which is most likely why dating-performers such as the infamous 'Tinder Swindler', a male dater who often played the 'role' of an heir to a diamond tycoon on Tinder to defraud women, opted to make the app dating experience more exceptional and 'immersive' – and at the same time dangerous and fraudulent. He thereby arguably responded to a heightened yearning for exceptional, emotional experiences in the face of a growing datafication and rationalization that is in line with current developments in capitalist culture. The article demonstrates that a blended performance of the mundane and the exceptional can work against such extremes of 'burnout' or capitalist exploitation, by giving a voice and agency to those who have not been listened to – or have often been viewed as passive – in the dating process, for instance due to their gender and ethnicity. Theories of the performance of the everyday and of digital everyday performance are employed to enhance the understanding of how such blended pieces work, but it will also be shown that the 'mundane' and the 'exceptional' can take on a multiplicity of meanings in this context, or even resist a fixed meaning altogether at times, in order to counteract simplistic readings or (pre-)conceptions regarding gender and ethnicity. The case studies analysed here – Lían Amaris Sifuentes’ and Luke DuBois' Fashionably Late for the Relationship (2007-8) and Jacob Boehme's Blood on the Dance Floor (2016) – work with feminist and queer-indigenous-HIV-positive dramaturgies to shed light on the dating process, embrace the performance of the mundane, but, as I argue, also work creatively with blendings between the mundane and the exceptional in order to provoke socio-political change.

Dating has in a sense always been a performance, especially regarding the ‘first date’. In the process of getting ready for it, one might try on different ‘costumes’, rehearse different ‘scripts’, potentially bring a certain gift/‘prop’ along to impress the date and ‘perform’ in a special space. Afterwards, one is often anxious/curious what the ‘audience’/date thinks about the ‘performance’ and wonders if one should follow the informal ‘rule’ of waiting three days to get in touch again. Dating thus seems to share characteristics that Richard Schechner typically associates with ‘restored behavior’: ‘actions … that are prepared or rehearsed’ (2013: 29) and with play, games, sports, theatre and ritual: ‘1) a special ordering of time; 2) a special value attached to objects; 3) non-productivity in terms of goods; 4) rules. Often special places – non-ordinary places’ (2003: 8). However, the expectation frequently is that such a date-performance will not just be ‘special’, but extraordinary – a once-in-a-lifetime ‘meetcute’ story of how someone met ‘the one’. As behavioural scientist Logan Ury explains, while written poems of exceptional love have existed for at least four millennia, it was largely the influence of love poetry during the Age of Romanticism, twentieth- and twenty-first-century TV/film romantic comedies and Disney-like fairy tales that have led to such ‘sky-high expectations’ of extraordinariness today (2021: 25).

Modern online or app dating, however, which did not exist until the 1990s and 2010s respectively, can highlight the more mundane sides of such a date-performance. It has seemingly turned dating from special events to performances akin to job interviews and has commercialized the process. As Eva Illouz points out, Internet dating is a much more rationalized, economic transaction-like process than dating was in the past – at least since the idea of romantic love took hold (2007: 90). The ‘cost-benefit aspects of [the] search’ can lead to a ‘combination of tiredness and cynicism’ (89). Older forms of dating, which emerged in the United States from about the 1890s onwards, already made it common for daters to ‘sell themselves’ on a ‘free market’ (Weigel Citation2017: 7–12). However, online dating has increased such competition enormously (Illouz Citation2007: 88), which in turn has heightened the pressure to perform ‘well’ on a date. Via their profiles, the prospective daters can theoretically be seen by millions of other daters – and vice versa. This potentially large number of options and dates that one person can have might take away some of its excitement and increase the mundanity of dating. While the process of swiping on a dating app can become addictive and lead to short highs when a new match appears, to those who swipe frequently, it can become an everyday event and wear out with time, even resulting in dating ‘burnout’ (Pearson Citation2022).

I argue that because of the increased mundanity that is often felt nowadays regarding the dating process, some modern daters have gone to the other extreme and have opted to make their performance as exceptional as possible in order to stand out, sometimes to extremely detrimental effects. One of the perhaps most notorious examples in this regard is the so-called ‘Tinder Swindler’, whose performance attracted quite a large audience – both in terms of the number of women he dated and defrauded, and in the form of an eponymous 2022 Netflix documentary that was made about his criminal behaviour. However, as this article will demonstrate, rather than such extreme performances – which can lead to either a work-like feeling of dating burnout or result in falling prey to malicious exceptional dating performances – there are also performances that work creatively with blendings between the mundane and the exceptional. As will be shown, such blendings have the potential to work against imbalances of power between dater and ‘audience’/date and against dating ‘scripts’ that are overly dominated by male/white/Western/heterosexual perspectives.

Blended performances can help give a voice and agency to those who have not been listened to – or have often been viewed as passive – in the dating process, for instance due to their gender and ethnicity. After looking in more detail at the idea of regarding dating as a performance, using theories of performance of the everyday put forward by Erving Goffman, Richard Schechner and Alan Read as well as concepts of digital everyday performance, presented by Richard Lonergan, Lyndsay Michalik Gratch and Ariel Gratch, I will first analyse the ‘Tinder Swindler’s’ more extreme performance, which shows a clear power imbalance and capitalist exploitation, before turning to the notion of a blended performance when examining the following two performance pieces: Lián Amaris Sifuentes’ and Luke DuBois’ Fashionably Late for the Relationship (performance 2007; film 2008Footnote1) and Jacob Boehme’s Blood on the Dance Floor (premiered 2016; published 2021). Both of these pieces, which work with feminist and queerindigenous-human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive dramaturgies, respectively, shed light on the dating process, embrace the performance of the mundane, but, as I argue, also work creatively with blendings between the mundane and the exceptional in order to provoke socio-political change. While Fashionably Late for the Relationship, however, lures the audience in through an initial emphasis on the exceptional, Blood on the Dance Floor arguably attracts the audience through a preliminary use of familiar mundane strategies, before revealing a more extraordinary, mysterious and traumatic underbelly of the supposedly trivial performance of dating.

Lián Amaris Sifuentes in the boudoir setting on busy Union Square traffic island, New York, in Fashionably Late for the Relationship. Photo by Doug DuBois

These three examples were chosen because they are all linked by first dates. Furthermore, they bring together the digital and ‘real life’. The portrayal of modern dating is currently on the rise – with popular TV shows such as Channel 4’s First Dates and newspaper items about ‘blind dates’ (for example, in The Guardian) also tapping into this phenomenon. The theatre company Paines Plough presented Miriam Battye’s first-date piece Strategic Love Play at the Edinburgh Festival in 2023. There are also other theatre/performance pieces such as Patrick Marber’s Closer (1997) or Ontroerend Goed’s Internal (2007) that explore the idea of a first date. However, such shows appear to focus mostly on the more curious/extraordinary aspects of modern dating and modern love. Marber’s Closer contains a scene in which two characters meet in a chat room, with one of them pretending to be someone else. The play is often linked to the highoctane ‘in-yer-face’ tradition, as it drastically highlights a transactional view of love and the cruelty of betrayal. Its emphasis is on the destructive sides of modern ‘love’, caused by commercialization. Ontroerend Goed’s Internal was an immersive experience that centred on live one-to-one dates between performers and audience-participants, and the subsequent public revelation of details obtained from the participants during those ‘intimate’ encounters. The emphasis here lay on the complexities surrounding the building of ‘intimacy’ in a short period of time, and the ethically problematic disclosure of ‘internal’ information. While important in their own right, Closer and Internal seem to focus more on speed and excitement. In contrast, the works by Amaris Sifuentes/DuBois and Boehme include slowness/everydayness and embrace both the mundane as well as the exceptional.

I argue that ‘mundanity’ in the context of dating can take on different meanings – such as tediousness, rationality, commercialization, data-drivenness, familiarity, privacy, triviality, superficiality, light-heartedness, slowness and quietness. At the opposite end of the spectrum, the ‘exceptional’ can be seen to include meanings such as excitement, emotionality/irrationality, danger, glamour, unfamiliarity, mysteriousness, publicity, melancholy, trauma, speed and loudness. This creates a multiplicity of meanings and, at times, a resistance to fixed meaning altogether, both in Fashionably Late for the Relationship and Blood on the Dance Floor, which can counter-act simplistic readings and conceptions of gender and ethnicity in these performances and in the dating process.

It is important to note, however, that quite a number of the above-mentioned meanings of ‘mundanity’ are connected to the fact that dating is increasingly becoming a more everyday, work-like activity. Neoliberal fast-paced concepts of work and the speed of digital communication have aimed to counter-act the often-perceived slowness of dating, by making it part of ‘fun’ game-like swiping apps. Nevertheless, as Catherine Pearson (Citation2022) in a recent New York Times article has pointed out, the impression of the tediousness of the process often remains for many app users, as lasting ‘results’ of this ‘game’ often take time to come to fruition, if they come about at all. The idea of dating turning almost into a second job (ibid.) and thus being part of everyday routines, links it to the wider area of performance theory and performance of everyday life. Erving Goffman’s analysis of how we perform in everyday sociocultural situations is still highly relevant in this context. First dates are about first impressions and Goffman’s focus is very much on the impression we (intentionally) ‘give’ and (potentially unintentionally) ‘give off’ to others. He writes:

Of the two kinds of communication – expressions given and expressions given off – this report will be primarily concerned with the latter, with the more theatrical and contextual kind, the nonverbal, presumably unintentional kind, whether this communication be purposely engineered or not. (Goffman Citation2021: 12)

Goffman is thus more concerned with the effect of a performance, rather than with intentionality or ‘truth’, which is also important in the context of online dating where often multiple self-identities are created with different effects (Gratch and Gratch Citation2022: 21). He seems fascinated by the impressions we leave on others and what might happen if those impressions get disrupted – for example, through ‘unmeant gestures, inopportune intrusions, faux pas and scenes. These disruptions, in everyday terms, are often called “incidents.” When an incident occurs, the reality sponsored by the performers is threatened’ (Goffman Citation2021: 187). The disruption of the performance can affect the entire ‘story’ created by the performer, which is often tied to their ego (214), and can thus lead to embarrassment and humiliation (ibid.). This observation seems particularly apt in a dating context where the fear of rejection is frequently at the back of the mind of potential daters.

Regarding dating and performance, Richard Schechner’s observations on performances of ‘one’s life roles in relation to social and personal circumstances’ (2013: 29) are crucial, which connect art with ordinary life – as are his writings on ritual and performance, as dating is often seen as a kind of ritual (Weigel Citation2017: 7). Schechner establishes a connection between sexuality and performance, and famously argues that ritualistic human fertility and hunting dances, which link sexuality, fertility and hunting, were perhaps among the earliest human performances (2003: 68–9). While dating is no longer necessarily associated with fertility, the idea of a kind of ritual – or even dance – that two daters perform, and where perhaps one or both are chasing the other, has persisted. This can also be seen in Jacob Boehme’s performance Blood on the Dance Floor, which will be discussed later in this article.

Like Goffman and Schechner, Alan Read (Citation1995) also brings together theatre and everyday activities, but adds a specific focus on the ethics of performance in regard to (everyday) oppression, discrimination and censorship. While there is perhaps an over-emphasis on the everyday giving rise to performance (vi) – rather than the everyday being performative, Read’s book provides an important lens for my analysis as my examples about dating and performance are concerned with ethical and political issues. They use feminist and queer-indigenous-HIV-positive dramaturgies in order to highlight, and ideally change, power imbalances. Read writes:

My everyday life inevitably impinges on someone else’s and it is there that the pleasures of human interaction occur and the possibilities of theatre begin. It is also here that issues of racial oppression, sexist discrimination and censorship manifest themselves, and the concept of everyday life is expected to reveal these fundamental politics, not conceal them with vagaries. (Read Citation1995: 97)

He thus emphasizes the importance of performance shedding light on the politics of a certain everyday context. Shortly after that, however, he also talks about the need for performance to ideally transform and improve everyday life ‘for as many as possible’ (Read Citation1995: 100): ‘there is a specific ethical, political and aesthetic purpose to the choice of the everyday as the realm within which theatre is to be most usefully thought’ (98). He cautions against aiming to find one single theory of the everyday in relation to theatre, but rather encourages to pay close attention to specific temporal and spatial contexts regarding performance and everyday life (98–100), which is what I aim to do in my analysis of particular examples.

In regard to everyday performances that specifically happen through digital technologies, Patrick Lonergan’s book about Theatre and Social Media (2016) and Lyndsay Michalik Gratch and Ariel Gratch’s Digital Performance in Everyday Life (2022) offer important insights. While only mentioning dating platforms in passing, they both suggest that anyone who sets up an online profile can be seen as performing. People present themselves – or rather their persona/e – in a certain way because they want to be seen in a specific way, which may or may not coincide with how they are received by the ‘audience’ of other online users. They edit and curate their lives for the purpose of this performance, and, depending on the platform(s) they are using, they might present themselves differently and thus create various personae and different performances (Gratch and Gratch Citation2022: 21). Lonergan cites Brenda Laurel, who in 1991 established an analogy between a computer interface and a theatre stage (2016: 13–15). He also points out that it was the development of Web 2.0 that mainly allowed for interactivity and self-expression online, resulting in computer users becoming not just like audience members but also ‘like actors, playwrights and directors’ (16). Gratch and Gratch see the greatest potential of digital performances mainly in the way they ‘can help us see and encounter reality in more diverse ways’ (2022: 2). Regarding the political potential of digital performances provoking change, they see the dangers of ‘echo chambers and filter bubbles’ (10), but emphasize that digital performances can offer ‘new forms of political engagement’ (ibid.). As will be demonstrated, Amaris Sifuentes/DuBois’ Fashionably Late, in particular, explores such diverse ways of political engagement – both through ‘live’ performance and through a digital one. Before talking about Fashionably Late and Blood on the Dancefloor, however, I would first like to turn to the ‘Tinder Swindler’ as an extreme example of using dating for the purpose of an ‘exceptional’ performance.

The so-called ‘Tinder Swindler’, born Shimon Hayut, aimed to create an extraordinary performance for his dates, especially at the very beginning. He seemed obsessed with first impressions as that was how he established the credibility of his persona, which can be connected to Goffman’s observation of the performer often linking the success or failure of creating an impact on others very closely to their own ego (2021: 214). He even went so far as to change his name from Shimon Hayut to Simon Leviev, that is, he adopted various personae – not only online but also on his passport, thus blurring the boundary between ‘real life’ and his online performance. Pretending to be the son of a wealthy Israeli-Russian diamond tycoon called Lev Leviev, he used the Tinder dating app to defraud numerous women across Europe. All in all, it is believed that he conned women out of ten million dollars in total. As the 2022 Netflix documentary of the same title directed by Felicity Morris shows, the ‘Tinder Swindler’ created an elaborate ‘script’ for his first dates, and made sure that the women he conned followed this script by becoming emotionally attached to him early on, thus establishing a clear power imbalance through his performance, which he then exploited for his fraudulent behaviour. Whenever he first connected with a woman, it appears as if he wanted to create a fully immersive one-to-one experience for her. His modus operandi, and thus the ‘script’ of his performance, seemed similar in all cases: he set up an online profile on which he showed off his exaggerated lifestyle. Once he related to a woman on Tinder, he ‘love-bombed’ her, that is he constantly showered her with attention and affectionate messages, followed by a glamorous first date – for example, on a flight on his private jet – to impress upon her the belief of extreme financial luxury.

As the Netflix documentary demonstrates, after the women fell in love with him – or rather with the persona he had created – he suddenly introduced a plot twist in his performance, for instance, that his life was in danger, he needed money and could not use his own credit card as that would be traceable (Morris Citation2022). To emphasize that the threat to his life was ‘real’, he sent his love interests a picture that showed that his bodyguard had been beaten up, and he expressed his own fear via a seemingly credible breathless and anxious performance over voice messaging. As soon as a woman he was dating sent him a credit card or gave him cash to help him out, he had the funds again for his lifestyle and the opportunity to deliver an impressive performance for yet another woman he met on Tinder, thus setting up a Ponzi scheme. He established lines of loans and credit in the women’s names and left them holding the bills. Interestingly, when he was caught, he never showed any signs of ethical qualms, as he argued that he gave the women what they needed: an experience. As he put it, ‘I never took a dime from them; these women enjoyed themselves in my company, they travelled and got to see the world on my dime’ (Staff Citation2019). He is thereby continuing to gaslight the women he conned, and this article in no way wishes to state that the victims can be blamed for the horrible scheme that the ‘Tinder Swindler’ used.

It appears that he fully exploited the fact that online dating can entail quite tedious and mundane performances. Modern dating has become a commercialized and rationalized process that relies on data, which in turn can foster a yearning for an emotional high. Eva Illouz writes about growing rationalization presently going hand in hand with greater emotional intensity. Referring also to Sara Ahmed’s The Promise of Happiness (2010), Illouz states that ‘[f]ar from heralding a loss of emotionality, capitalist culture has on the contrary been accompanied with an unprecedented intensification of emotional life, with actors self-consciously pursuing and shaping emotional experiences for their own sake’ (2018: 5). Instead of mundanity, the moneyoriented ‘Tinder Swindler’ offered a different extreme: a fast connection and an exciting, even dangerous, performance. As the creation of his dating experience showed, he took advantage of the fact that we are now increasingly living in an ‘experience economy’, which is no longer first and foremost about goods and services, but where customers ‘spend time enjoying a series of memorable events that a company stages – as in a theatrical play – to engage [them] in an inherently personal way’ (Pine and Gilmore Citation2011: 3). As B. Joseph Pine II and James H. Gilmore clearly state, the driving forces behind such experiences can be morally virtuous or immoral (xxvi), but if they are engaging and memorable their perceived value can rise (xxii). The ‘Tinder Swindler’ provided an exceptional experience, until his actions were laid bare by some of the women he had conned. To some extent this discovery deflated him and led to a temporary arrest, but it also resulted in continued interest via the Netflix documentary.

To avoid the push-and-pull effect of a performance of mundanity versus a yearning for an emotionally intense performance, modern dating might be approached differently, namely through a blending of mundanity and exceptionality. A prospective dater could use the more rational beginnings of modern dating to their advantage in the hope of finding someone special. Interestingly, online dating coaches such as Jonathon Aslay (Citation2020) and Matthew Hussey (Citation2022) state that, while the emphasis is still on meeting up in person as soon as possible after connecting online to see if there is attraction, one can use the seemingly more tedious, disembodied and conversation-based nature of first encounters in Internet/app dating as an opportunity to ask better questions of prospective dates and to thereby actually start getting to know someone on a deeper level instead of relying purely on chemistry. What Illouz depicts as a negative – that is, the fact that ‘cognitive knowledge … precede[s] one’s sentiments’ (2007: 90) in modern digital dating contexts – can be turned into a positive. One could argue that the performance of the mundane, which in this case comprises the asking of meaningful questions rather than the over-reliance on a romantic spark, could mix with an exceptional performance, when one is open to slowly building a connection with someone special, rather than expecting fast results.

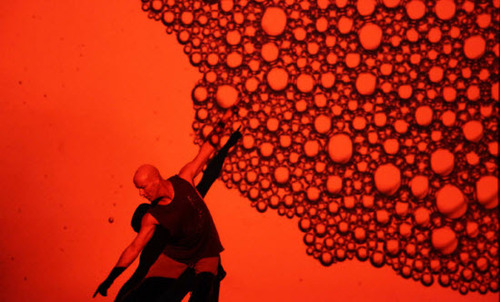

Jacob Boehme dances in partnership with blood cells by multi-media artist Keith Deverell in Blood on the Dance Floor. Photo by Dorine Blaise. Courtesy of ILBIJERRI Theatre Company

I would now like to examine two performance pieces – Lián Amaris Sifuentes’ and Luke DuBois’ Fashionably Late for the Relationship (2007–8) and Jacob Boehme’s Blood on the Dance Floor (premiered 2016; published 2021) – that shed light on the dating process, embrace the performance of the mundane, but, as I argue, also work creatively with blendings between the mundane and the exceptional to provoke change. To use Alan Read’s words, these performances do not just highlight an issue but aim to improve everyday life ‘for as many as possible’ (1995: 100). In Fashionably Late, Amaris can be seen to approach this via a feminist dramaturgy that de-centres the importance of meeting a man, that is, of the date event itself, and instead emphasizes the process of getting ready as a performance in its own right. ‘The man’ is no longer seen as the goal, that is, a typical sense of male/Western teleology is taken out of the equation and Amaris refuses to follow traditional notions of speeding up the preparation process in order to get to that supposed goal. Instead, she completely slows the process down and chooses to be ‘fashionably late’. Furthermore, rather than opting for an intimate setting, she lays bare the workings of the date preparation in full public view, on Union Square traffic island in New York, thus potentially highlighting the problematic fact that women’s emotional labour is often invisible and that they are usually expected to put more effort into date preparations than men. Eva Illouz, for instance, writes how women often spend much more time and money when it comes to preparing for a date (2018: 1). While this performance piece does not specifically mention online dating or apps, it is linked to the ‘digital’ through its online (co-existence) as a shorter film version created by DuBois. This film version turns Amaris’ performance into a never-ending one, much like an online presence does a date.

At first glance, Fashionably Late might seem to be more about the extraordinary than the mundane. In the bipartite work of art, that is, in both the ‘live’ performance and the film, Lián Amaris can be seen in various glamorous vintage dresses in a boudoir setting that contains a dark red chaise longue. She wore ‘five dresses that … comprised a ’30s fulllength gown, a ’50s party dress with petticoats, a ’60s beaded shift dress, a timeless black cocktail dress, and a contemporary pink redux of a Seven Year Itch-inspired halter dress’ (Amaris Citation2008: 184). While not presenting one specific time, she wanted to capture classic notions of femininity, and in all of her actions she aimed for the ‘beautifying and beautiful’ (ibid.): ‘I did not … pluck wanton hairs or put on deodorant’ (ibid.). Young girls who quickly stopped by to watch seemed to be in awe of the glamour presented in front of them. Amaris comments:

[T]hey looked as though they desperately wanted to break … into this perfect, glamorous world. Perhaps the most painful irony of the piece was that my (re) presentation of beauty would likely reinforce the impossible standards many of these girls would labor under for the rest of their lives. (Amaris Citation2008: 190)

As Amaris mentions here, the reaction of these girls was not what she was aiming for. She highlights ‘the problematic male gaze’ (2008: 190), performativity and construction of gender according to Judith Butler (183), and the ‘ritualiz[ing] of Erving Goffman’s concept of the performance of self in everyday life, referencing popular images of femininity’ (190). Rather than being a pin-up girl that others emulate, she wanted to show that this is a construct. Nevertheless, she brings together a glamorous performance of femininity with the mundanity of her preparatory events, the latter of which is emphasized through the slowness of these events. The ‘live’ performance was in fact a 72-hourlong endurance piece, and Amaris performed all her actions extremely slowly. She stretched out the time it would usually take to perform all her date-preparation activities from a 72-minute estimate to a 72-hour performance. For instance, drinking a glass of wine took her seven hours (185). The glamorous, exceptional side of the performance might have lured spectators in, but if they opted to stay longer they were confronted with the mundane side of Amaris’ performance. Taken together, the exceptional and the mundane arguably here have the effect of questioning traditional notions and expectations of femininity and of enabling Amaris to show the full extent of her agency in her own solo performance.

The ‘live’ performance took place on a very hot and busy post-fourth-of-July weekend – from midnight on Friday 6 July 2007, until midnight 9 July 2007 (DuBois Citation2007). Amaris could be seen preparing herself for a date in a boudoir setting right in the middle of a traffic island. The boudoir consisted of a dressing table, with mirror and small stool, a chaise longue, a phone and clock, a screen, a dress-rack, a rug, various dresses, a bottle of wine, a wine glass, a pitcher of water, a water glass, a fruit bowl, a vase containing flowers, two lamps and an ashtray (ibid.). During the 72 hours she performs actions that are typically associated with getting ready for a date: having a pre-date nap, eating small things (in this case an orange and a banana), washing, sitting down, drinking a cocktail, taking a phone call, brushing her hair, doing her makeup (foundation, eye shadow, eye liner, mascara, lip liner, lipstick, perfume), choosing an outfit (dress), selecting shoes, putting on jewellery, retouching her makeup, packing the purse, checking the mirror and leaving (Amaris Citation2008: 185).

These are all rather mundane actions, and Amaris writes herself that it was a ‘presentation of the quiet, the banal, and the private’ (183). However, she did not just replicate trivial actions from everyday life. Through her extreme slowmotion performance and through bringing the private into the public sphere, she turned these actions more visibly into rituals and thus clearly showed how ‘context distinguishes ritual, entertainment, and everyday life from each other’ (Schechner and Shuman Citation1976). In doing so, and in combining the exceptional with the mundane, Amaris’ performance can highlight several new meanings of the seemingly trivial actions connected to ‘getting ready for a date’. It can draw attention to and thereby problematize what is often expected of women in terms of preparing for a date and in regard to the pre-formed ‘scripts’ they need to follow according to traditional male/ white/Western/heterosexual perspectives. Second, it can also demonstrate that the preparation for the date is already a performance and important in its own right. It does not require the date to happen. No man is needed to fully complete her – or her performance.

In a similar way to Amaris’ piece, Luke DuBois also creates a blend between an exceptional and mundane performance. While he emphasizes that he wanted to explore the topic of (exceptional) obsession with a muse in his film version (DuBois Citation2007), his piece, like that of Amaris, was not created for viewers to be merely seduced by the spectacle, but to also question traditional notions of femininity, by highlighting Amaris’ mundane actions, albeit in a slightly different way. The film version is not just a documentary of Amaris’ piece. It is a multi-camera and thus multi-perspective 72-minute version of that performance that is not merely shortened or accelerated, but also blended in terms of time and space. As Matthew McLendon notes: ‘[Amaris] seems not to be smoking, and then she is smoking again. Then she is on the phone. To the left of the screen she stands, pacing back and forth, while on the right side of the screen she simultaneously sits, still talking on the phone’ (2014: 18). This creates a complicated viewing experience – both regarding the ‘live’ version and the filmed one – which in turn resists a mere fast consumption of the spectacle.

What perhaps links Amaris’ performance most closely to DuBois’ film version is the fact that, while they are both public, they show that in a time when often the most private aspects of one’s life end up on social media, there can still be performances that are not easily turned into commodities for consumption. DuBois plays with letting the viewer be seemingly taken in by his work of art. By turning it into a film that is readily available on Vimeo and that shows Amaris from various angles and freezes her in time, Amaris seemingly becomes an object. She appears to exist not in her own right, but for the benefit of DuBois’ gaze – he speeds up her performance, slows it down and edits as he sees fit. She thereby also becomes an object for the gaze of the viewer of his film. This would appear to be counter to what Amaris herself intended. She was the author of her own piece, and the film could take this control away from her.

However, since DuBois manipulated time and space in the film version, the ‘real’ Amaris cannot ever be fully reached. Just like in her endurance piece, she retains her power and autonomy in the film; the viewer might aim to find out what was ‘real’ and not and carefully try to see what details might have been missed but will never completely attain the ‘original’ performance. Some scenes only ever happened in the ‘real-life’ performance and cannot be captured by media, as Amaris is careful to point out, alluding to Peggy Phelan (2008: 192). DuBois is a media artist who challenges his audience to not be taken in by data (2016). His work emphasizes that we need to question what we are being shown today, how data is created and to what purpose. He is a highly ethical data artist who wants us to look behind what we think might be ‘fake’ or ‘real’. DuBois draws attention to the paradox that we are all wary of surveillance but become obsessed with knowing everything about a celebrity (2016). By bringing together the exceptional and the mundane, both Amaris’ piece and DuBois’ film resist simplistic readings and consumption and instead encourage careful viewing and reflection. And they both give power and centrality to female spaces and rituals that might otherwise seem invisible.

Like Fashionably Late, Jacob Boehme’s Blood on the Dance Floor (2016) is an empowering solo performance and also takes the idea of getting ready for a date as a starting point. However, it looks at it from another angle and takes a different form. Blood on the Dance Floor is an autobiographical piece that combines theatre, dance, Indigenous ceremony, monologue and image. It was written and developed by Boehme, directed by Isaac Drandic, choreographed by Mariaa Randall and produced in partnership with ILBIJERRI Theatre Company, one of Australia’s leading Indigenous companies. By adopting the autobiographical persona of ‘Jake’ but also taking on other personae, Boehme explores the politics of queer, Indigenous and HIV-positive/ ‘poz’ identities in this piece. Via ‘Jake’, Jacob Boehme, who comes from the Narangga and Kaurna nations of South Australia and was diagnosed with HIV in 1998, seems to invoke the past in this piece in order to both stare trauma directly in the face and to have a potentially healing effect on the present time.

The theme of dating marks the beginning – as well as end – point of the performance, and it seems to trigger all other memories and events. In contrast to Fashionably Late, which initially seems to attract viewers by linking dating to exceptionality, in Boehme’s piece, dating may at first appear to be solely a mundane performance. That is, the audience here interestingly seems to be lured in by the mundanity of a familiar scenario. In the persona of ‘Jake’, Jacob Boehme refers to the common activity of online dating, where one often relies on mundane bulletpoint-type lists of one’s date’s characteristics. However, dating is then quickly presented as potentially highly traumatic, as it is here linked to the difficult question of how and when to inform the prospective partner about an HIV infection, which then may lead to rejection and despondence.

The mundane thus constitutes the starting point and hook of the performance, but this then opens up into a more extraordinary exploration of the ghosts of Jake’s past, present and future, which then blends the exceptional with the mundane. Jake feels haunted by different time periods. In what can be seen as a preface to the piece, the drag queen Percy – one of the different personae Jacob adopts in the performance alongside his own persona/e – for instance speaks about the aftermath of the height of the AIDS epidemic being like ‘Halloween: Ghosts and skeletons, standin’ at the bar, on the dance floor’ (Boehme Citation2021: 5). Bookended by the topic of dating, which gives it a circular structure overall, the piece is based on associations and goes back and forth in space and time. As Boehme points out in an interview, ‘[t]his work is all the shit that goes through the mind when walking up the hallway to answer the door [to a date]. The play is actually ten seconds long’ (2018: 361). This seems to be like DuBois’ play with time and space, which also resists traditional male/ white/Western/heterosexual linearity and teleology. The date with a new love interest and the topic of rejection lead Jake to remember and enact various other scenes from his life where either he or his father felt rejected and discriminated against.

The different episodes of the piece are also connected to metaphorical meanings of colours – brown as the colour of his father’s skin, and red as the colour of blood. Blood not only inspired the title of the entire piece, by referring to Boehme’s experience of dancing on floorboards with nails in them after his diagnosis and leaving a trail of blood behind him (Boehme Citation2018: 347). It is also central to the overall dramaturgy, as it takes on the double meaning of referring to bloodline and to the fluid that carries the human immunodeficiency virus, which in the performance creates a link between various types of discrimination – due to his heritage, queerness and HIV-positive identity. As Boehme explains in an interview, the act of looking at his own blood was a crucial source of inspiration for the piece: ‘it sounds mystical, but my father’s voice started to come; my grandma’s voice started to come; ancestors’ voices started to come’ (346). In developing the piece, Boehme became interested in epigenetics and how ‘responses to trauma’ are ‘passed on’ through the bloodline (ibid.). The metaphor of blood arguably evokes a certain mysteriousness and otherworldliness that defies a spectator’s mastering reading and ‘know-it-all’ gaze for this performance about shame linked to HIV and how to overcome it. João Florêncio importantly notes in his chapter in Queer Dramaturgies that in relation to AIDS and art, metaphor can be used ‘as a device that enables the artist to allude to AIDS as a reality that is both unlocatable and irreducible to its symptoms’ (2016: 178). Instead of creating a power imbalance between audience-witness and story-teller, such mysteriousness arguably ‘co-implicate[s]’ (ibid.) the viewers by confronting them with something that is not easily graspable, and helps to take them along on Jake’s difficult journey.

What could be an entirely bleak piece about discrimination and rejection in life and love becomes filled with hope and courage. This happens whenever Jake conjures up moments of love and connection in his past, and when he is in touch with a sense of community. This invocation, which occurs not merely through text, but also via image and dance, was directly influenced by ancient Indigenous ceremonies (Boehme Citation2018: 349) and brings those traditional markers of community into contact with his solitary thoughts of despair. The ghosts of Jake’s past (his ancestors, people who died of AIDS, his friend Anthony who committed suicide), present (his father) and future (his own future self) drive him to continue looking for love and community.

As mentioned, Jacob Boehme also takes on other personae during his solo-performance. In the prelude to the piece, he starts off as Percy, an ageing drag queen who is about 50 or 60 years old, and who is meant to show ‘a different take on the HIV conversation to date – being very irreverent and very dark, black humour’ (Boehme Citation2018: 352). Percy remembers the early days of the AIDS epidemic in Sydney, ‘which took out every drag queen … Total apocalypse. And the funerals. We’d be goin’ 2,3,4 times a week!’ (Boehme Citation2021: 5). The drag queen then talks about newer medical developments, which made contracting HIV less feared – to the point of even attracting groups of ‘bug chasers’ who want to get infected (6). This leads Percy to conclude that the disease ‘took the best of us and left us with a steaming pile usually found down the bottom of the vegetable garden’ (ibid.), potentially indicating that some of those who are still around feel ‘less than’ and a kind of survivor’s guilt. Shortly after that statement, Boehme changes from Percy into ‘Jake’, Boehme’s alter ego on stage, a ‘white Aboriginal man of about 30 or 40’ and begins to dance. At first, this dance sequence that connects him to his ancestors seems to show a man who is full of confidence. His proud and – at times – animal-like movements appear to firmly link him to the natural world and to being in harmony with the earth. They might also hark back to a kind of mating dance ritual that Schechner alludes to (2003: 68–9). However, Jake’s confidence quickly disappears when he stops dancing, starts nervously pacing back and forth and talking about his upcoming date with a man he started seeing a few weeks ago and whom he later refers to as Oscar.

Tonight’s the night. He’s taking me to Chin Chins, some fabulous restaurant in Flinders Lane apparently. He’s a foodie. Likes his cafes and restaurants and eating out. He knows some of the quirkiest little places. Tick. He swims. Does Yoga. Doesn’t drink! Very Zen. Loves to travel. Big tick. Paris is one of his favourite cities. I’ve always wanted to go back to Paris with someone. (Boehme Citation2021: 7)

It is as if Jake is going through the bullet-point information presented on an online dating profile again, and he puts his date on a pedestal, while putting himself down. He is not sure whether or not it is too early to say ‘I love you’ (8). When he gets a text message saying, ‘We need to talk’, he immediately thinks he is going to be ‘dumped’ (ibid.). When it actually turns out to be positive news, that is, the man he is dating says ‘[m]aybe we should think about being exclusive’ (8–9), Jake imagines a scenario where they both go shopping together at IKEA, which leads to a row that quickly ends their relationship. He repeats the words said by Percy ‘I tell ya, it took the best of us and left us with a steaming pile’ (9). He is hesitating to get closer to Oscar as he had ‘written [him]self off for any of this stuff’ (8), but on the other hand he likes this man and is yearning for intimacy and connection. Jake’s monologue is interspersed with images of an older man that are shown in the background. As it turns out later in the performance these are images of an older Jake, who is lonely, ‘hasn’t been touched in years’ (25) and is living a dismal existence. The first appearance of these images just affects Jake’s mood, but the second appearance affects him physically (10). These imaginary visions of the future and his strong desire not to end up alone push Jake to continue with this potential relationship.

Jake then talks about another date he has with Oscar, where he wonders whether to reveal his ‘poz’ identity or not. This time the date takes place at Oscar’s home. While helping his love interest prepare the vegetables for their dinner, Jake accidentally cuts into his finger and quickly withdraws his hand as Oscar approaches to kiss the bloody wound. These actions are both verbally and physically narrated. Instead of revealing that he withdrew his bleeding finger due to his being HIV-positive, Jake just says, ‘Don’t do that. I’m not good with blood. Makes me sick’ (11). The focus on blood and the colour red leads to another empowering but also threatening dance in front of a red screen depicting blood cells, which is accompanied by an unsettling music score. As Boehme points out when talking about the role of movement and dance in the piece, ‘It’s when you can’t speak any more that you have to let it out of your body’ (2018: 352). It seems Jake is seeking courage and reassurance through this dance, but this feeling does not last, as it is soon followed by a scene in which Jake reflects on his past and calls up traumatic events surrounding rejections. Blended voiceover and visceral breath recordings are used to surround him with numerous memories both of the time he got infected himself and of the rejections he has received due to the tendency of potential partners to want unprotected sex. Scenes alluding to casual sexual encounters at a ‘beat’ on a beach at nighttime are evoked through images created by videographer Keith Deverell, and Jake is confronted multiple times with the brutal, and loudening, dating question: ‘Man, I’d love to fuck you raw / Are you clean?’ (Boehme Citation2021: 14). It becomes clear that he was rejected many times, and often he was blamed for having contracted HIV. He is accused of lacking self love. A menacing voice adds: ‘If I see you online again, I’ll let them all know what you are’ (16). It becomes obvious how his selfesteem and mental health had been affected by such cruel rejections. At the same time, the gut-wrenching question ‘are you clean?’ is then also directed at the audience (Boehme Citation2018: 358), thereby again co-implicating the spectators in an embodied way in Jake’s journey.

Earlier in the performance, Jake thinks about what the right time is to reveal certain details about oneself in the dating process. He mentions playing several roles or aspects of a persona, rather than presenting the ‘real’ him:

So far, I’ve been charming Jake. Funny Jake. Rolling off my list of degrees of awards. On paper I’m not half bad, ya know Bit of a ‘know it all’, but I’d date me. Now he’s gonna learn all those things you just don’t want them to know. Like I … don’t cook, I’m a closet ‘Roseanne’ fan – I’ve got every series hidden behind the bookshelf. And I buy my laundry liquid from Aldi. Things you just don’t want them to know. He’s gonna run a mile. (Boehme Citation2021: 10)

This shows that the mundanity – in the sense of light-heartedness – of modern dating is not really possible for him as he sees it. ‘Just seeing where it goes’ is not really an option, as he must think about wider consequences. There is always a deep seriousness – or even sadness – about dating for him. This seems to hark back to Judith Butler’s writings on queerness and the melancholy caused by ‘a certain foreclosure of possibility that produces a domain of homosexuality understood as unlivable passion and ungrievable loss’ (1995: 168). In Jake’s case, however, his ‘poz’ identity seems to immensely increase such feelings of melancholy. Even the reference to ‘Aldi’ is not light-hearted, as it is linked to another perceived source of shame – issues of class. As Boehme notes about the reference to Aldi, ‘if there wasn’t HIV, then what else? What else would make you nervous. The class thing … ’ (2018: 362).

About mid-way through the performance we are introduced to Jake’s father, who is alone, ill and not visited by the other siblings. Boehme here alternates between the persona of Jake and that of Jake’s father. The father can be seen as a kind of ghost of the present that resembles Jake’s own future image and thus emphasizes his fear of ending up like his father, who in fact cautions him against being alone. We learn about the discrimination that both son and father were confronted with in their past due to their Indigenous background. And the scene also shows how Jake’s upbringing was influenced by his own skin colour being different from that of his father, which might have led to a sense of disconnection to his ancestry. His past was also impacted by his dad’s dislike of his own skin colour and by his father’s belief in an overly romanticized, heterosexual love that seems to have put a lot of pressure on Jake. Furthermore, his father’s lack of self-esteem appears to have in turn harmed Jake’s own sense of self-worth, which points to the idea that trauma is being passed on through the bloodline.

However, ultimately the ghosts of the past, present and future drive Jake on, rather than bringing him down. Remembering the suicide of an HIV-positive friend called Anthony, who had been disowned by his family and whose name was no longer spoken, Jake decides to actively reconnect with his family and ancestry and to look for love. He wants to make the most of his life and he does not want to end up alone like his father. So instead, he seeks community. He invokes his ancestry – especially in his various dances throughout the performance, which in the end give him courage to truly embrace all aspects of his identity, in public.

At the very end of the performance, the time circles back to his preparation for the first date with Oscar. Jake opts for full disclosure – both to the audience and, as he imagines, later to Oscar. Furthermore, Jacob Boehme sheds the persona of ‘Jake’ and speaks as himself to the audience:

I’m Jacob Boehme. I come from the Narangga and Kaurna people of South Australia. I’m poz. I was diagnosed in 1998, at the age of 25. I’ve been living with HIV for 20 years. I have an undetectable viral load. I take anti-retrovirals, 2 pills every morning. And I’m in love. Oh, and I don’t cook, I’m a closet Roseanne fan and yes, I buy my laundry liquid from Aldi … That sounded alright didn’t it? Didn’t it? Just say it like that? (Boehme Citation2021: 25–6)

Whereas only the more trivial aspects of his dating persona were mentioned at the beginning of the piece, Jacob now completely espouses both the mundanity and the exceptionality of his dating situation. This seems to go along with fully celebrating who he is and inspiring others to do the same – and the ghosts of his past, present and future appear to have helped him with this crucial step.

To conclude, both Lián Amaris Sifuentes’ and Luke DuBois’ Fashionably Late for the Relationship and Jacob Boehme’s Blood on the Dance Floor show how to take back power and agency in an increasingly commercialized dating context and in a dating process that is traditionally marked by power imbalances, often based on gender or ethnicity. Using feminist and queer-indigenous-HIV-positive dramaturgies, respectively, they work creatively with blendings between the mundane and the exceptional in order to defy pre-formed white/male/Western/heterosexual dating ‘scripts’ that can be not only limiting but traumatic and harmful. Mundanity and exceptionality in this context, while often being linked to a sense of everydayness vs. noneverydayness, here take on a multiplicity of meanings and, at times, even resist a fixed meaning altogether, in order to counter-act simplistic readings and conceptions of gender and ethnicity. As has been demonstrated, the blending of the mundane and the exceptional in both cases allows the artists to not only highlight problematic preconceptions, but also to forcefully work against them in order to provoke change.

Notes

1 See Amaris Sifuentes and DuBois (Citation2012 [2008]).

REFERENCES

- Ahmed, Sara (2010) The Promise of Happiness, Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Amaris, Lián (2008) ‘Beauty and the street: 72 hours in Union Square, NYC’, TDR 52(4): 182–92. doi: 10.1162/dram.2008.52.4.182

- Amaris Sifuentes, Lián and DuBois, Luke R. (2012 [2008]) Fashionably Late for the Relationship, https://vimeo.com/45470140, 9 July, accessed 16 February 2023.

- Aslay, Jonathon (2020) ‘Ask these five questions before you get serious with a man’, https://bit.ly/49VGzAC, 6 August, accessed 16 February 2023.

- Boehme, Jacob (2018) ‘Blood, shame, resilience and hope: Indigenous theatre maker Jacob Boehme’s Blood on the Dance Floor’. Interview with Jacob Boehme. Interviewed by Alyson Campbell and Jonathan Graffam, in Alyson Campbell and Dirk Gindt (eds) Viral Dramaturgies: HIV and AIDS in performance in the twenty-first century, Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 343–65.

- Boehme, Jacob (2021) Blood on the Dance Floor, Hobart: Australian Plays.

- Butler, Judith (1995) ‘Melancholy gender – refused identification’, Psychoanalytic Dialogues 5(2): 165–80. doi: 10.1080/10481889509539059

- DuBois, R. Luke (2007) ‘Fashionably Late for the Relationship: Some notes’, www.lukedubois.com, 1 October, accessed 16 February 2023.

- DuBois, R. Luke (2016) ‘Insightful human portraits made from data’, https://bit.ly/3T42zmT, 15 February, accessed 16 February 2023.

- Florêncio, João (2016) ‘Evoking the strange within: Performativity, metaphor and translocal knowledge in Derek Jarman’s Blue’, in Alyson Campbell and Stephen Farrier (eds) Queer Dramaturgies: International perspectives on where performance leads queer, Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 178–91.

- Goffman, Erving (2021) The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, New York, NY: Knopf Doubleday.

- Gratch, Lyndsay Michalik and Gratch, Ariel (2022) Digital Performance in Everyday Life, London: Routledge.

- Hussey, Matthew (2022) ‘Most of us let our emotions rule our life’, https://bit.ly/49VydJj, 11 August, accessed 16 February 2023.

- Illouz, Eva (2007) Cold Intimacies: The making of emotional capitalism, Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Illouz, Eva (2018) ‘Introduction: Emodities or the making of emotional commodities’, in Eva Illouz (ed.) Emotions as Commodities: Capitalism, consumption and authenticity, Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 1–29.

- Lonergan, Patrick (2016) Theatre and Social Media, London: Palgrave.

- McLendon, Matthew (2014) ‘Now – The temporality of data’, in Matthew McLendon, Anne Collins Goodyear, Dan Cameron and Matthew Ritchie (eds) R.Luke DuBois –Now, New York, NY: Scala, pp. 12–21.

- Morris, Felicity (2022) The Tinder Swindler, https://bit.ly/47QSUEn, 2 February, accessed 16 February 2023.

- Pearson, Catherine (2022) ‘A decade of fruitless searching’: The toll of dating app burnout’, https://bit.ly/46Rr4Hn, 31 August, accessed 30 October 2023.

- Pine, B. Joseph II and Gilmore, James H. (2011) The Experience Economy, Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Read, Alan (1995) Theatre and Everyday Life: Ethics of performance, London: Routledge.

- Schechner, Richard (2003) Performance Theory, London: Routledge.

- Schechner, Richard (2013) Performance Studies: An introduction, London: Routledge.

- Schechner, Richard and Shuman, Mady (1976) Ritual, Play and Performance: Readings in the social sciences/theatre, New York, NY: Seabury.

- Staff, Toi (2019) ‘”Tinder Swindler” extradited back to Israel to face charges’, Times of Israel, https://bit.ly/46zNj4o, 7 October, accessed 16 February 2023.

- Ury, Logan (2021) How to Not Die Alone: The surprising science that will help you find love, London: Piatkus.

- Weigel, Moira (2017) Labor of Love: The invention of dating, New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.