Abstract

With the promulgation of the Apostolic Constitution Veritatis Gaudium in 2018, Roman Catholic ecclesiastical higher education institutions had a quality evaluation process imposed on them, developed by the Holy See’s Agency for the Evaluation and Promotion of Quality in Ecclesiastical Universities and Faculties (AVEPRO). It is yet a case of ‘lex imperfecta’, with no formal consequences following the reviews. This study argues that the Agency is using persuasion in its policy text to ensure institutional buy-in. Persuasive patterns are displayed through the exploration of metadiscourse and its links to Aristotle’s concepts of ethos, pathos and logos. While logos or rational argumentation would more naturally be expected in policy guidelines, the use of metadiscourse markers related to pathos or emotional appeal is high. A supplemental layer of analysis also unearthed a significant level of ethos, a means of convincing the audience by appealing to the authority and credibility of the author(s).

Introduction

The Apostolic Constitution Veritatis Gaudium has been considered ‘one of the largest education reform attempts worldwide’ (Vettori et al., Citation2019, p. 40). In this text promulgated in 2018, the Catholic Pope refers to ‘a radical paradigm shift’ and ‘a bold cultural revolution’ for ecclesiastical higher education (Francis, Citation2018, p. 4). One of the most significant changes resulting from Veritatis Gaudium has been the development of a newly imposed quality evaluation process for all ecclesiastical institutions related to the Roman Catholic Church across the world. The Holy See’s Agency for the Evaluation and Promotion of Quality in Ecclesiastical Universities and Faculties (AVEPRO) was charged to develop and implement the quality assurance policy, taking into consideration the specificities of a distinctive higher education context. While the Constitution enforced AVEPRO’s quality reviews, it is yet a case of ‘lex imperfecta’ (Vedung, Citation1998, p. 31), when no consequence is linked to the evaluations, whether they are positive or negative. In light of the specific nature and scope of the Holy See’s higher education system, how does AVEPRO intend to ensure institutional buy-in and compliance with its quality assurance policy?

Through the exploration of metadiscursive markers, this study reveals the persuasive language used in AVEPRO’s quality assurance policy, and makes the argument that, in the absence of coercive authority on ecclesiastical institutions, the Agency is using persuasion in the texts as a governance tool to execute its mandate.

Setting the stage: the Holy See’s higher education system

In international law, the Holy See is considered as the jurisdiction of the Pope, being himself regarded as a juridical personality. The Holy See therefore represents the governance system of the Roman Catholic Church. It has a territorial basis, the Vatican, but its scope of activities, including higher education, extends globally (Barbato, Citation2013). ecclesiastical higher education institutions have been set up within this system with the aim of studying and teaching canon law, theology, biblical studies, church history and philosophy, as part of the Church’s evangelising mission (Congregation for Catholic Education [CCE], Citation2012, p. 3). There are currently 792 institutions situated in all parts of the world, and for historical reasons a majority (494) are based in Europe (AVEPRO, Citation2019a, p. 4). Some take the form of stand-alone institutions, while others are inserted in larger institutions, such as a catholic university or a public university. Beyond the large geographical coverage and consequent cultural diversity, their organisational structure varies as well, with 289 ecclesiastical faculties and 503 related entities classified as either affiliated, aggregated, connected to or incorporated into a faculty. Ecclesiastical higher education institutions grant academic degrees in the name of the Holy See, and are governed by the Code of Canon Law, the Apostolic Constitution Veritatis Gaudium and its norms of application.

AVEPRO’s quality evaluation policy

AVEPRO published a revised quality evaluation policy in 2018, shortly after the promulgation of Veritatis Gaudium. The policy is collected in a set of five documents:

Guidelines: Nature, context, purpose, standards and procedures of quality evaluation (AVEPRO, Citation2019d);

Guidelines for Self-Evaluation (AVEPRO, Citation2019b);

Guidelines for External Evaluation

Guidelines on Strategic Planning (AVEPRO, Citation2019c);

The Ecclesiastical Higher Education System in the Global World: The rationale of AVEPRO’s evaluation system (AVEPRO, Citation2019a).

These documents provide guidance to all ecclesiastical institutions to prepare for the mandatory AVEPRO external review. These institutions, however, are also required to be accredited by the Congregation for Catholic Education (CCE). While accreditation remains the prerogative of the CCE, AVEPRO is in charge of quality evaluation and quality improvement of the ecclesiastical institutions. This shared responsibility adds to the previously mentioned contextual complexity of AVEPRO’s mandate. The CCE has a potential coercive power by not accrediting or reaccrediting an institution, and derives its authority and legitimacy from being part of the Roman Curia, the centralised government of the Catholic Church (Catholic Church, Citation1983, cc. 360–61). According to the Agency, the CCE takes into consideration AVEPRO’s external evaluation reports in its own accreditation work (AVEPRO, Citation2019a, p. 59), yet this is a case of a policy anomaly, or ‘lex imperfecta’, since there is no pass or fail decision following AVEPRO reviews, nor formal consequences in the case of negative feedback.

A recent report of AVEPRO’s operations by the European Association for Quality Assurance in Higher Education (ENQA) pointed out the contextual challenges faced by the Agency, in particular as it relates to its scope of work, but it also ‘found a culture and operations very much benefitting from a shared sense of mission and good will’ (Vettori et al., Citation2019, p. 40) and recognised a ‘focus on the promotion of a quality culture that is dialogue oriented’ (Vettori et al., Citation2019, p. 29). The ENQA report further mentioned that ‘the approach of the agency to create trust as a foundation for any further activities is vital, as within the context of the higher education system of the Holy See AVEPRO very much relies on “soft power”’ (Vettori et al., Citation2019, p. 16). This emphasis on dialogue and trust creates a bridge to the empirical analysis of the next section. According to Pelclová and Lu (Citation2018) and Stensaker (Stensaker, Citation2018), trust cannot simply be taken and normally derives from the social environment but it can also be developed and manipulated through persuasion. Pelclová and Lu’s collection of essays on persuasion in public discourse highlighted the strong connection between trust and persuasion (Pelclová & Lu, Citation2018, p. 232). This will be further explored in the next section, and its implications on governance.

Modes of public governance and persuasion

Governance and persuasion are connected notions in the academic literature, yet there is no agreement on the extent of this relationship (Steurer, Citation2011). Governance itself is a fuzzy term and various definitions have been offered by scholars. For this paper, public governance best refers to using various means ‘to shape or change the behaviour of people’ (Bell et al., Citation2010, p. 852). The processes and interactions between governing and governed actors have traditionally been categorised within three modes of governance: hierarchy, market and network (Powell, Citation1990). Hierarchy incorporates a notion of top-down steering, in the form of ‘command and control’ (Hysing, Citation2009). Changes in behaviour occur from constraints or threats. Market-based governance leaves action in the hands of competition and auto-regulation. Here governed actors are altering their behaviour on the basis of financial incentives. Network governance is characterised by the involvement of interdependent public and private actors in policy decision-making and implementation. Behavioural change results in this case from negotiations and bargaining between these actors (Steurer, Citation2011).

Bell et al. (Citation2010) put forward the concept of persuasion as a distinctive element in the governance literature, which they describe as a non-coercive way to change people’s behaviour, and therefore to govern. The authors argued that ‘persuasion constitutes a further and distinctive mode of governance’ (Bell et al., Citation2010, p. 853). Governance scholars are split as to whether persuasion should be considered as a mode of social steering on its own or should rather be seen as an underlying part of existing governance modes (Steurer, Citation2011). The debate, however, most certainly confirms the importance of persuasion when discussing governance and policy-making in today’s complex, interconnected, and multi-actor world (Gottweis, Citation2006b, pp. 462–63, Majone, Citation1997, p. 269). It is now broadly recognised that ‘acts of persuasion are inherent in policy and political processes, just as they are within all communications’ (Nicoll & Edwards, Citation2004, p. 45, emphasis added). There are nevertheless various levels of persuasion and persuasive intent in policy discourse. This leads this argumentation towards a rhetorical look at the concept of persuasion and how discourse analysis can help establish the persuasive nature and degree of policy discourse.

Discourse analysis and persuasion

Discursive approaches to the analysis of public policy were inspired by the ‘linguistic turn’ in social sciences and emerged in Anglo-Saxon public policy research at the end of the 1980s (Durnova & Zittoun, Citation2013). Moving away from the positivist idea that public policies can be analysed ‘as they are’, rationally and objectively, argumentative policy analysts suggest that language is both instrumentalised and instrumental in policy-making, and cannot be interpreted as value-free (Gottweis, Citation2006b). In this postpositivist and social constructionist perspective, discourse is recognised as socially and culturally situated and it is also creating a social and cultural reality: ‘Discourse, then, is both shaped by the world as well as shaping the world’ (Paltridge, Citation2012, p. 7). Discursive approaches place argumentation and rhetoric at the heart of policy practice and policy analysis. Rhetoric as defined by Aristotle represents ‘the faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion’ (Aristotle & Garner, Citation2005). He further developed the concept of persuasion around three persuasive means that may be used in combination or on their own, depending on the persuader’s intent and context:

Ethos, a means of convincing the audience by appealing to the persuader’s character, authority or credibility;

Logos, a technique appealing to the audience’s reason;

Pathos, a way of appealing to the audience’s emotions.

In spite of the development of communication technologies since Aristotle’s fourth century, scholarly works looking at persuasive patterns in discourse are still extensively based on the three pillars of persuasion defined by the philosopher (Pelclová & Lu, Citation2018, p. 8, Jucker, Citation1997, p. 126). The linguist Hyland (Citation2018) theorised the connection between Aristotle’s appeals of persuasion and metadiscourse. Although there is no universally accepted definition of the term, metadiscourse is a linguistic feature and its analysis in discourse ‘focuses our attention on the ways writers project themselves into their work to signal their communicative intentions’ (Hyland, Citation1998, p. 437). Hyland developed a model centred around rhetorical features (interactive versus interactional dimensions) and related linguistic markers (hedges, frame markers, transitions, endophoric markers, evidentials, code glosses, boosters, attitude markers, self-mentions and engagement markers) in order to analyse the writer-reader relational aspects of a discourse. Hyland argued that these markers, summarised in , are used by their authors not only to organise a text (interactive purpose) but also to position themselves vis-à-vis the reader (interactional purpose). In that sense, the analysis of metadiscourse use puts into light ‘how writers and speakers intrude into their unfolding text to influence their interlocutor’s reception of it’ (Hyland, Citation2018, p. 3).

Table 1. An Interpersonal model of metadiscourse (Hyland, Citation2018, p. 58)

Hyland connected specific metadiscourse markers with the three Aristotelian means of persuasion (Hyland, Citation2018):

Ethos can be achieved by using hedges, boosters and attitude markers;

Logos can be achieved by linking the arguments in a logical manner with interactive metadiscourse;

Pathos can be achieved by addressing the reader with interactional metadiscourse, in particular with the use of engagement markers, attitude markers and hedges.

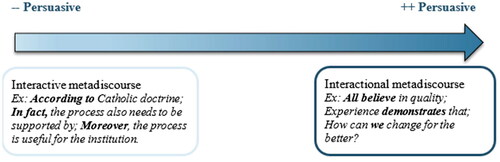

Analysing a document through this lens can uncover the means of persuasion potentially used in a text and the persuasive style chosen by the author. A higher use of interactional metadiscourse reveals a greater focus on persuading the audience through credibility or identity (ethos) or emotions (pathos), rather than through rational arguments (logos). Furthermore, the metadiscourse analysis method is valuable for evaluating the degree of persuasive intent in a text, given the fact that some markers have a more explicit persuasive function than others. On that basis, Dafouz-Milne (Citation2003) has developed a persuasion continuum, depicting the explicitness of persuasive intent in discourse. Interactive features are considered less explicitly persuasive than interactional ones. illustrates Dafouz-Milne’s continuum with examples found in the AVEPRO guidelines:

Figure 1. Adapted from Dafouz-Milne (Citation2003, p. 33).

Hyland’s metadiscourse approach has been extensively used for the analysis of business and academic texts (Hyland, Citation2017, p. 16, Ho, Citation2016, p. 6), but less so in the field of public policy. Ho (Citation2016) intended to close that gap with his metadiscursive analysis of education policy texts in Hong Kong. Depicting public policy documents as a distinctive genre, or discourse type, Ho highlighted the ethos, pathos and logos dimensions and compared the metadiscourse findings of the texts with other genres such as academic writing, journalistic texts and business communication. The methodological approach adopted for the analysis of AVEPRO’s quality evaluation policy builds on Ho’s paper.

Methodology

This study sits within the argumentative policy analysis approach (Gottweis, Citation2006a). It applies discourse analysis as a theoretical and methodological framework, with a focus on the use of metadiscourse. Since ‘there is no shared methodology in argumentative policy research’ (Gottweis, Citation2006a, p. 467), a two-dimensional methodological approach was chosen that draws first on methods from discourse analysis through metadiscourse to disclose persuasive patterns in the texts. The metadiscourse analysis is strengthened by a supplemental read of the policy to identify textual elements with ethos, pathos or logos dimensions that cannot be revealed through metadiscourse analysis. This additional layer of analysis is necessary since metadiscourse is not focusing on what a text talks about or ‘the world outside the text’ (Hyland, Citation2017, p. 18). Argumentative policy analysis on the other hand is contextualist and ‘the data collected in a case study must be understood in terms of the studied phenomenon’s own context, history, and sociality’ (Flyvberg, Citation2001, p. 115).

Dataset and metadiscourse approach

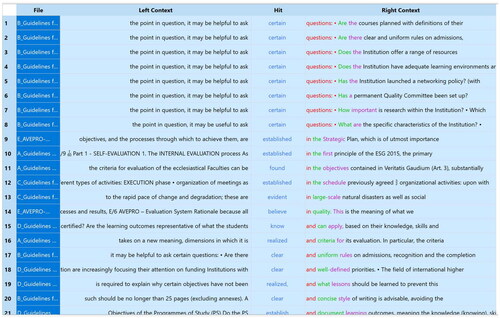

AVEPRO’s quality policy is composed of five documents. This analysis did not use the Guidelines for External Evaluation (document C) since they are targeted towards the external reviewers of the ecclesiastical institutions and not the institutions themselves. Hyland’s taxonomy of metadiscourse markers provides a list of search items, mostly words or expressions, that can flag the use of metadiscourse in a text, and whether it is interactional or interactive (Hyland, Citation2018). Measuring the frequency of specific words in a text is, however, insufficient to evaluate the degree of metadiscourse since, according to Hyland, metadiscourse is ‘pragmatic’ and every word should be examined in its sentential context to have any ‘explanatory power’ (Hyland, Citation2017, p. 19). For that reason the AntConc concordance and text analysis software (Anthony, Citation2022) was used to determine the frequency of metadiscourse markers and to easily display the words preceding and succeeding these markers. Each marker was then reviewed in context to confirm whether they can be classified as metadiscourse, and if so, in which marker classification. In this way a ‘reflexive’ qualitative approach to metadiscourse was adopted, rather than an ‘interactive’ or quantitative approach where a researcher would only take into account the frequency of words without further contextual investigation (Ädel & Mauranen, Citation2010, pp. 2–4) ().

A manual verification of each marker has proved necessary since some items identified in Hyland’s list as metadiscourse markers can in reality be propositional, or informative, rather than interpersonal, or reader-oriented. The paragraph below provides an example:

Moreover, the process is useful for the Institution as:

• It presents detailed information about the Institution, its mission, functions and activities, and the collective perceptions of staff and students of their role, not only in the university but in social and cultural development and, where appropriate, in the international community. (AVEPRO, Citation2019d, p. 12)

A small number of words to Hyland’s taxonomy have also been added since a closer read of the words in their textual context revealed a metadiscursive dimension. The word ‘like’ was for instance added to the list of code glosses since it links to an argument:

Universities must avoid all self-referentiality (like the idea that no-one can judge them, or that universities are kind of “private gardens” that must remain secret). (AVEPRO, Citation2019a, p. 5)

Findings

The metadiscourse data displayed in reveal 3600 metadiscursive markers in the four documents taken together, for a total of 26,030 words. The manual verification drastically reduced the number of markers to 730. This represents a frequency of use of metadiscourse markers of 28 per 1000 words. In comparison with other genres, this falls between business and journalism, in line with Ho’s findings on the Hong Kong educational policy reforms (Ho, Citation2016, p. 9). The next paragraphs will look at the use of some markers in more detail to reveal the ethos, logos and pathos persuasive dimensions of the texts.

Table 2. Metadiscourse analysis of AVEPRO guidelines A-B-D-E

Logos, or appeal to reason

The data in indicates that the proportion of interactive markers linked to logos, or rational reasoning, is 39.92% after manual review. AVEPRO’s documents are certainly presented in a way that attempts to logically guide the ecclesiastical higher education institutions in their evaluation process, with not only the use of interactive markers but also definitions of terms and step-by-step descriptions of the process, as well as the inclusion of templates the institutions can use to facilitate the review. The Guidelines also include sections where a problem is posed and a solution is provided, and the use of interactive markers supports the rationale:

In short, we are faced with a great cultural, spiritual and educational challenge, which, also for Ecclesiastical Institutions, implies processes of change towards a farsighted prospective configuration for ecclesiastical studies. This is another fundamental reason why all members of academic communities should immerse themselves, without hesitation, in the culture of quality. (AVEPRO, Citation2019a, p. 7, emphasis added)

Not all staff may be equally enthusiastic but, as far as possible, all should be encouraged to participate. The more the self-evaluation procedures are discussed and the further colleagues become involved, the more effective efforts to raise awareness of quality will be. Thus, staff and students will come into direct contact with the culture of quality and this will gradually lead to the development of a virtuous circle at all levels of the Institution. The culture of quality will therefore become an integral part even of routine procedures. (AVEPRO, Citation2019d, p. 13, emphasis added)

Pathos, or appeal to emotion

There is a larger range of interactional metadiscourse markers (60.08%) found in the text, in comparison with interactive markers. This result suggests the following two points. First, using Dafouz-Milne’s persuasion continuum (), the greater use of interactional metadiscourse indicates that the writers explicitly aimed to persuade the readers. Second, following Hyland’s work, it reveals pathos as the most used means of persuasion, showing the writer’s intent to demonstrate empathy and sympathy towards the readers and to involve them in the dialogue. Empathy and reader inclusion are most apparent in the extensive use of ‘you’ and ‘your’ categorised as engagement and self-mention metadiscourse markers. This is further strengthened by the use of the inclusive ‘we’, ‘our’ and ‘us’ in some parts of the texts. For example:

The Apostolic Constitution encourages reflection on the great changes of our era and motivates us to deal with the anthropological and environmental crisis that we are experiencing, with the hope of promoting a change in our developmental model. (AVEPRO, Citation2019d, p. 4, emphasis added)

The field of international higher education is increasingly competitive in terms of students, Faculties/facilities, research and funding; this also applies to “our” ecclesiastical Institutions. (AVEPRO, Citation2019c, p. 4, emphasis added)

You are invited to select the elements that you deem appropriate. (AVEPRO, Citation2019c, p. 23, emphasis added)

Thanks to the process of internal quality evaluation, the Institution has an opportunity to conduct a critical self-evaluation and review of the work it has carried out, as well as getting to know the point of view of students and other users of its various services. (AVEPRO, Citation2019d, p. 12)

Strategic planning and evaluation should not be viewed as mere “bureaucracy”, but rather as an opportunity for the academic community to create “a university life open to greater participation, a desire felt by all those in any way involved in university life” (cit. Foreword (V) to the Apostolic Constitution Sapientia Christiana). (AVEPRO, Citation2019c, p. 8)

Ethos or appeal of the writer’s authority and credibility

Ethos represents the third mode of persuasion reflected in the Guidelines, with the use of hedges, boosters and attitude markers (15.34%). The data show that hedges have been used more frequently than attitude markers and boosters. Hedges can signal the writer’s uncertainty about facts, and expressing caution was identified as a credibility-builder by rhetoricians (Hyland, Citation2018, p. 81). Hedges can also be used in certain rhetorical situations as artefacts to open the dialogue with the reader (Hyland, Citation2018, p. 61). This writer-reader relationship is illustrated multiple times in the Guidelines for Self-Evaluation, with ‘may’ sentences such as ‘it may be helpful to ask certain questions’ and ‘The Institution may also provide additional data to that expressly required, if it deems this of use for specific purposes’ (AVEPRO, Citation2019b). This can be interpreted as the Agency’s will to show respect and flexibility towards the institutions by not being overly prescriptive. This can reassure institutions that are often not experienced with quality assurance and strategic planning processes (de Wit et al., Citation2018, p. xv), or those that are sceptical about their ability to comply. Similarly, all AVEPRO documents insist on the fact that it is the institution’s responsibility to set up an internal quality process that fits its own nature and mission. This is particularly evident in the following sentence, with words emphasised in bold by AVEPRO:

It goes without saying that, as the Institutions differ enormously in terms of tradition, scope, size and form, they are certainly not all expected to do all that is indicated in this document. (AVEPRO, Citation2019c, p. 5, original emphasis)

The presence of boosters and specific attitude markers also contributes to ethos and helps establishing an authoritative positioning of the Agency. This occurs by showing certainty in the argumentation, which in turn restricts the space for dialogue and opposing views. Authority is apparent in the following examples:

This introduction intends to show how strategic planning has emerged as a clear necessity within universities. (AVEPRO, Citation2019c, p. 3, emphasis added)

Experience demonstrates that a high profile Quality Committee should be created. (AVEPRO, Citation2019d, p. 11, emphasis added)

Second, although AVEPRO does not have formal coercive powers, the threat of consequences is present when the Guidelines mention that:

the Evaluation Report is sent to the authorities: the Congregation for Catholic Education/CCE, the Grand Chancellor and any other academic authorities (Dean, Head, Rector), then published on the Agency’s website. (AVEPRO, Citation2019d, p. 20, original emphasis)

and

The Congregation reserves the right to take corrective actions, if necessary, in the light of problems emerging from the External Evaluation Report. (AVEPRO, Citation2019d, p. 9)

Last, as has been seen with the use of metadiscourse, the framing of the dialogic space can be a rhetorical device employed to assert authority. Earlier in this paper the word ‘appropriate’ was presented as an attitude marker in the following sentence: ‘The Agency needs to support the ecclesiastical Institutions in Europe to ensure that they achieve an appropriate position in the world of higher education’ (AVEPRO, Citation2019d, p. 7). This represents a case of rhetorical representation of a certain vision of the world, and of the role of quality evaluation. The use of ‘appropriate’ implies here that if ecclesiastic institutions do not follow the Agency’s guidance, then they will not be well placed in the international higher education stage. Other instances of framing occur throughout the texts, some being more explicit than others. In the example below, references are made to changing external contexts and demands, which imply a need for change at the institutional level:

The Ecclesiastical Institutions of higher education have an excellent tradition and history of providing services to the Church and society. However, they risk becoming static entities, closed and slow in responding to external challenges, and incapable of considering new priorities. (AVEPRO, Citation2019c, p. 3, emphasis added)

Conclusions

Persuasive patterns in AVEPRO’s quality policy have been displayed through the exploration of metadiscourse and its links to ethos, pathos and logos. The degree of persuasive intent in the texts is substantial as shown by the higher use of interactional markers. The metadiscourse analysis found that the policy’s authors greatly appealed to emotions or pathos, yet a supplemental layer of analysis of the texts also unearthed a high level of ethos to convince the readers. While logos or rational argumentation would more naturally be expected in policy guidelines, these results tend to show how AVEPRO aims to build a relationship with the readers and persuade them to abide by the policy in the absence of coercive power.

This article contributes to the debate about the role of persuasion in governance. Although it does not answer the question whether it is a mode of governance in itself, or rather an instrument of governance through hierarchy, market and network, it confirms, however, that in a complex system, governance is not only about technical procedures, nor is it only regulatory or political, there is a relationship dimension to make it work that comes from trust and legitimacy, which can be built through persuasion in discourse. On the methodology side, this article also affirms metadiscourse as a relevant analytical tool to study interactions and gain insights into what a public policy text conveys; it should, therefore, not be limited to the academic and business genres that are traditionally found in studies using this method. It is suggested to extend this study by applying metadiscourse analysis to policies from other quality assurance systems, and observe whether similar discursive patterns are used in an attempt to achieve the acceptance of their audience.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Ädel, A. & Mauranen, A., 2010, ‘Metadiscourse: diverse and divided perspectives’, Nordic Journal of English Studies, 9, pp. 1–11.

- Anthony, L., 2022, AntConc. 4.1.2 (Tokyo, Japan, Waseda University).

- Aristotle & Garner, E., 2005, Poetics and Rhetoric (New York, Barnes & Noble).

- Agency for the Evaluation and Promotion of Quality in Ecclesiastical Universities and Faculties (AVEPRO), 2019a, The Ecclesiastical Higher Education System in the Global World: The rationale of AVEPRO’s evaluation system. Available at: www.avepro.glauco.it/avepro/allegati/1133/E_AVEPRO-Rationale_2019.pdf (accessed 15 September 2022).

- Agency for the Evaluation and Promotion of Quality in Ecclesiastical Universities and Faculties (AVEPRO), 2019b, Guidelines for Self-Evaluation. Available at: www.avepro.glauco.it/avepro/allegati/1133/B_Guidelines%20for%20SELF-EVALUATION%202019.pdf (accessed 15 September 2022).

- Agency for the Evaluation and Promotion of Quality in Ecclesiastical Universities and Faculties (AVEPRO), 2019c, Guidelines on Strategic Planning. Available at: www.avepro.glauco.it/avepro/allegati/1133/D_Guidelines%20on%20STRATEGIC%20PLANNING%202019.pdf (accessed 15 September 2022).

- Agency for the Evaluation and Promotion of Quality in Ecclesiastical Universities and Faculties (AVEPRO), 2019d, Guidelines: Nature, context, purpose, standards and procedures of quality evaluation and promotion. Available at: www.avepro.glauco.it/avepro/allegati/1133/A_Guidelines%20AVEPRO%202019.pdf (accessed 15 September 2022).

- Barbato, M., 2013, ‘A state, a diplomat, and a transnational church: the multi-layered actorness of the Holy See’, Perspectives: Review of International Affairs, 21(2), pp. 27–48.

- Bell, S., Hindmoor, A.M. & Mols, F., 2010, ‘Persuasion as governance: a state-centric relational perspective’, Public Administration, 88, pp. 851–70.

- Catholic Church, 1983, Code of Canon Law (Vatican). Available at: www.vatican.va/archive/cod-iuris-canonici/cic_index_en.html (accessed 17 September 2022).

- Congregation for Catholic Education (CCE), 2012, Quality Culture. A handbook for ecclesiastical faculties (Vatican, Vatican Press).

- Dafouz-Milne, E., 2003, ‘Metadiscourse revisited: a contrastive study of persuasive writing in professional discourse’, Estudios Ingleses De La Universidad Complutense, 11, pp. 29–52.

- De Wit, H., Bernasconi, A., Car, V., Hunter, F., James, M. & Véliz, D. (Eds.), 2018, Identity and Internationalization in Catholic Universities: Exploring institutional pathways in context (Leiden, The Netherlands, Brill).

- Durnova, A. & Zittoun, P., 2013, ‘Les approches discursives des politiques publiques’ [Discursive approaches to public policy], Revue française de science politique, 63, pp. 569–77.

- Flyvberg, B., 2001, Making Social Science Matter. Why social inquiry fails and how it can succeed again (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press).

- Francis, 2018, Veritatis Gaudium Apostolic Constitution on Ecclesiastical Universities and Faculties (Vatican, LEV Libreria Editrice Vaticana).

- Gottweis, H., 2006a, ‘Argumentative policy analysis’, in Handbook of Public Policy, Chapter 27 (London, Sage).

- Gottweis, H., 2006b, ‘Rhetoric in policy making: between logos, ethos, and pathos’, in Frank, F. & Miller, G.J. (Eds.), 2006, Handbook of Public Policy Analysis: Theory, Politics, and Methods (New York, Routledge).

- Héritier, A. & Eckert, S., 2008, ‘New modes of governance in the shadow of hierarchy: self-regulation by industry in Europe’, Journal of Public Policy, 28, pp. 113–38.

- Ho, V., 2016, ‘Discourse of persuasion: a preliminary study of the use of metadiscourse in policy documents’, Text & Talk, 36, pp. 1–21.

- Hunter, F. & Sparnon, N., 2017, ‘Quality assurance in ecclesiastical institutions of higher education: “Did we pass?”’, Educatio Catholica, 3, pp. 169–74.

- Hyland, K., 1998, ‘Persuasion and context: the pragmatics of academic metadiscourse’, Journal of Pragmatics, 30, pp. 437–55.

- Hyland, K., 2017, ‘Metadiscourse: what is it and where is it going?’, Journal of Pragmatics, 113, pp. 16–29.

- Hyland, K., 2018, Metadiscourse: Exploring interaction in writing (London, Bloomsbury Publishing).

- Hysing, E., 2009, ‘Governing without government? The private governance of forest certification in Sweden’, Public Administration, 87, pp. 312–26.

- Jucker, A.H., 1997, ‘Persuasion by inference: analysis of a party political broadcast’, Belgian Journal of Linguistics, 11, pp. 121–37.

- Majone, G., 1997, ‘The new European agencies: regulation by information’, Journal of European Public Policy, 4, pp. 262–75.

- Nicoll, K. & Edwards, R., 2004, ‘Lifelong learning and the sultans of spin: policy as persuasion?’, Journal of Education Policy, 19, pp. 43–55.

- Paltridge, B., 2012, Discourse Analysis: An introduction (London, Continuum).

- Pelclová, J. & Lu, W.-L., 2018, ‘Persuasion across times, domains and modalities: theoretical considerations and emerging themes’, in Pelclová, J. & Lu, W.-L. (Eds.), 2018, Persuasion in Public Discourse (Amsterdam & Philadelphia, John Benjamins).

- Powell, W., 1990, ‘Neither market nor hierarchy: network forms of organization’, Research in Organizational Behaviour, 12, pp. 295–336.

- Stensaker, B., 2018, ‘Quality assurance and the battle for legitimacy—discourses, disputes and dependencies’, Higher Education Evaluation and Development, 12, pp. 54–62.

- Steurer, R., 2011, ‘Soft instruments, few networks: how ‘new governance’ materializes in public policies on corporate social responsibility across Europe’, Environmental Policy & Governance, 21, pp. 270–90.

- Vasheghani Farahani, M., 2020, ‘Metadiscourse in academic written and spoken English: a comparative corpus-based inquiry’, Research in Language, 18, pp. 319–41.

- Vedung, E., 1998, ‘Policy instruments: typologies and theories’, in Bemelmans-Videc, M.-L., Rist, R.C. & Vedung, E. (Eds.), 1998, Carrots, Sticks, and Sermons: Policy instruments and their evaluation (Piscataway, NJ & London, Transaction Publishers).

- Vettori, O., Heintze, R., Niemi, H. & Kitching, M., 2019, ENQA Agency Review: Holy See’s Agency for the Evaluation and Promotion of Quality in Ecclesiastical Universities and Faculties (AVEPRO). Available at: www.enqa.eu/wp-content/uploads/AVEPRO-external-review-report.pdf (accessed 17 September 2022).