Abstract

Quality enhancement projects in universities frequently rely on short-term, fragmented studies implemented in response to snapshot data linked to student feedback. Such projects may not address the complex interplay across stakeholder groups and do not always acknowledge the unintended consequences of change. This article, focused on systems design, draws on research conducted over seventeen years and demonstrates how an intentional approach to linked quality enhancement projects can influence quality culture across an institution. The use of a longitudinal wicked problem theory approach allows the consideration of students’ experiences as multi-faceted, influenced by a wide range of stakeholders and interrelated factors. This approach can be used to co-create actions, build trust in the cultural changes needed for long-term improvements and ensure that investment in large-scale institutional changes is effective.

Introduction

The importance of quality assurance in higher education is widely assumed (Cardoso et al., Citation2015) but relatively little scholarly work has discussed the development and enhancement of a quality culture that embeds consideration of quality across a university (Legemaate et al., Citation2022). A significant quantity of research involves relatively small-scale and short-term surveys with a focus on performance indicators that can oversimplify complex problems and overlook interlinked elements (Hamshire et al., Citation2017; Harvey, Citation2022a). There may be a focus on a single measurement instrument such as the United Kingdom (UK) National Student Survey (Brown et al., Citation2015; Buckley, Citation2012; Burgess et al., Citation2018; Langan et al., Citation2015) or on a metric such as student persistence in university. A common reductionistic approach to addressing perceived educational problems in higher education, such as student progression or student satisfaction, is to implement a tactical short-term project, focusing on outcomes. A programme team might respond to a drop in student satisfaction with group assessment by removing group work altogether. When the programme is next reviewed, employers may report that graduates are insufficiently prepared for teamwork and so the groupwork is reinstated. If students say that feedback is not timely, the university may focus on monitoring the dates when feedback is returned rather than exploring what students’ perceptions of timeliness are and whether it is perceived differently across programmes.

A temporary concentration on these single, if complex, issues may have a short-term impact but may not reveal anything about how the whole culture of a university can be enhanced so that all activities are of high quality. A more critical examination of quality in higher education is needed, with consideration of how it relates to shared values and collective ownership (Harvey, Citation2022a; Legemaate et al., Citation2022).

Kacaniku’s analysis of Kosovo’s moves towards joining the European Higher Education Area suggests that accountability has tended to take precedence in quality discussions but that there is a need to have a balance between accountability and improvement to develop a quality culture (Kaçaniku, Citation2020). A focus on accountability does not acknowledge that students’ experiences across a diverse population are individual (Hamshire & Jack, Citation2016): many readers will be familiar with the suggestion that ‘we changed X in response to student evaluation last year, and this year the students said they would prefer it to be the original way’. Acknowledging that the factors that affect students’ experiences of higher education are complex and that surveys at single points can only ever collect a ‘temporal slice’ of their experiences is an essential first step (Hamshire et al., Citation2017). Understanding students’ experiences needs to be grounded in empirical evidence and critical social research that recognises that individual needs, motivations and expectations shift and change throughout students’ studies, influenced by both personal and external factors (Benson, Citation2006; Hamshire et al., Citation2013b; Kandiko & Mawer, Citation2013; Skinner, Citation2014).

Further work analysing and improving processes to ensure that they work for the whole student population across their higher education experiences is required, with a focus on deconstructing dominant discourses and reconstructing an understanding that identifies the social and historical interrelationships (Harvey, Citation2022a). This article presents a process that uses a wicked problem-solving approach to enhance quality, with examples from practice, including what started out as short-term studies.

Concatenated research

Concatenated research describes a form of longitudinal qualitative exploration in which a series of studies are linked, as if in a chain, leading to cumulative grounded theory (Stebbins, Citation1992). Initial studies are predominantly exploratory and each subsequent study examines or re-examines a related aspect (Stebbins, Citation1992). For example, qualitative interviews with students might be followed by a large-scale quantitative survey to determine scale. This approach can support the understanding of complex and persistent problems over time to locate student and staff voices as their experiences develop and identify what factors influence their experiences.

The work described here began as separate exploratory studies, one focusing on student experiences (Hamshire & Cullen, Citation2010, Citation2014) and the other on staff experiences (Forsyth & Cullen, Citation2016). Following data collection and presentation at institutional conferences for the two studies, it became apparent that there would be considerable advantages to working collaboratively to inform institutional developments and cultural change to develop understanding of substantive issues (Harvey, Citation2022a). As the authors each continued to progress subsequent research projects and collaborate, the value of sequentially combining data from these educational studies was evident, as a process to subsequently develop insights into learning and teaching from both students and staff as a type of longitudinal research (Stebbins, Citation1992)

Each exploratory study unfolded with an accumulation of research and application of theory (Stebbins, Citation2001) to build on the findings of previous work, providing opportunities to explore both the intended and unintended consequences of institutional change. The collated staff and students’ narratives were therefore central to successive institutional developments, as they articulated their individual and team experiences. These seventeen years of research provide unique insights into the impact of historical issues and social and cultural factors to facilitate incremental solutions to wicked problems. This approach challenges taken-for-granted views and offers an alternative perspective (Harvey, Citation2023), advancing the study of sets of related groups and quality processes towards increased methodological and theoretical rigor (Stebbins, Citation1992).

Wicked problems

The ‘wicked problem’ framework developed by Rittel and Webber (Citation1973) was initially proposed to address significant, complex problems that were difficult to progress, identified by ten key properties (). Such wicked problems were characterised as both dynamic and challenging to solve (Sherman & Peterson, Citation2009) and, as a consequence, solutions may have no stopping points or definitive outcomes (Hamshire et al., Citation2019). The framework has been used across a wide range of policy areas, with a focus on problems that cannot be addressed through linear, reductionist approaches (Prowse & Forsyth, Citation2017; Thompson & Houston, Citation2024).

Table 1. The ten properties of a wicked problem

Wicked problems within a higher education context

Quality in higher education exhibits all the characteristics of a wicked problem, requiring contextually appropriate solutions, as well as being difficult to solve absolutely. Frequently, there is no definitive agreement on what the problem is and, without this agreement, the search for a solution is open-ended (Roberts, Citation2000). Addressing such problems requires multidisciplinary collaboration and change within and across institutional microcultures (Roxå & Mårtensson, Citation2015) to include diverse and divergent voices (Hamshire et al., Citation2019).

Using a wicked problem theory framework to explore quality enhancement acknowledges the inter-relatedness of complex factors and provides a focus for taking a long view about problem resolution. An expectation of conflicting views and uncertainty encourages a focus on both the intended and unintended consequences of any solutions (Pohl et al., Citation2017; Prowse & Forsyth, Citation2017). This leads to an iterative approach involving continuous learning, adaptation and refinement of strategies. The intentional inclusion of all stakeholders and micro-cultures, alongside a recognition that there is no simple solution, ensures that solutions and processes work for a diverse student population across their higher education experiences. This enables the focus to be moved away from short-term, linear solutions to longer-term quality enhancement through embedded consultation and feedback on outcomes, collective ownership and shared values.

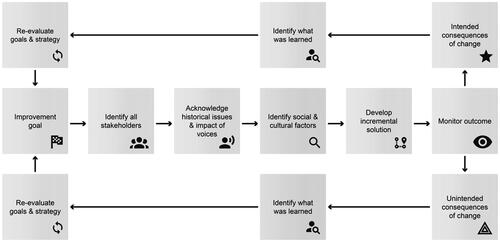

This approach is represented in the general model for wicked problem management shown in (adapted from Hamshire et al., Citation2019). It was developed during a regional study exploring student attrition from healthcare programmes within the northwest of the UK, with a recognition that a shift in thinking was required to recognise the complex interplay across factors and predict the potential consequences of interventions (Hamshire et al., Citation2019, Citation2012b).

Figure 1. General model for wicked problem management (Hamshire et al., Citation2019).

Accepting that large-scale changes in a university can be conceptualised as wicked problems facilitates the reframing of discussions about students’ experiences from small-scale, local interventions towards holistic, multi-stakeholder solutions (Hamshire et al., Citation2012a, Citation2012b). This conceptual change also emphasises that challenges can frequently be due to systems and problems that interact with one another rather than standalone issues (Sabin, Citation2012). Teams may be working on separate but interconnected tasks without good understanding of other parts of the university’s work: changes in one team’s policies may have consequences for resourcing in other areas. For example, changing a mitigating circumstances policy in response to student requests might lead to a substantial increase in appeals which are dealt with by another department.

Wicked problem management for quality enhancement

Although quality improvement must be incremental and continuous, change projects often begin as top-down initiatives to address numerical performance indicators or perceptions of the university, such as those presented by rankings or league tables (Hamshire et al., Citation2017). Funding must be secured and, for that, objectives must relate to the apparent ‘problem’ and the project must have specific deliverables. This can make it difficult to link changes in projects to past and future work. Acknowledging these issues and using a concatenated approach in conjunction with the wicked problem framework enabled the authors to explore how policies and social factors contributed to institutional culture and ultimately affected students’ learning experiences over time in relation to a series of institutional change priorities and projects. This iterative process also allowed the authors to focus on the experiences of the stakeholder groups, acknowledge historical issues and the impact of their voices, to discuss how quality improvements could be achieved through integrated stakeholder involvement.

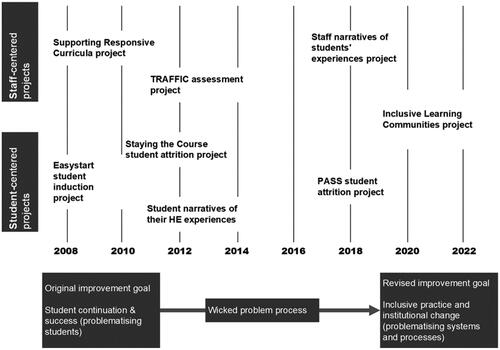

The concatenated research presented here focused on stakeholder involvement by combining research from two strands, staff perspectives and student perspectives () and applied the Hamshire et al. (Citation2019) wicked problem model to develop incremental solutions through inclusive practice to achieve sustained institutional change. These projects are detailed in .

Table 2. Projects included within the two strands of the concatenated research

Strand 1: an exploration of student experiences moving away from problematising the students to problematising the systems

Students’ higher education experiences are widely acknowledged as being multifaceted, yet research studies frequently fragment and thematically split their experiences focusing on a particular snapshot in time of the students’ overall experience; or targeting a particular aspect of that experience (Hamshire et al., Citation2013a). To critique the studies presented here, the beginnings of this concatenated research were in 2006 when one of the authors explored the barriers and facilitators to level four student engagement with online learning resources ‘Easy Start’ (Hamshire & Cullen, Citation2010, Citation2014). This initial project explored students’ transition to higher education and formed the foundation for an exploration of the factors that contributed to healthcare student attrition in the ‘Staying the Course’ study (Hamshire et al., Citation2012a, Citation2012b, Citation2013a, Citation2013b). Implicit within these projects was an exploration of how institutional support systems and resources could be developed to meet the needs of a diverse student population; essentially a deficit model problematising students rather than institutional systems. Both studies utilised a mixed-methods approach combining quantitative and qualitative data for a comprehensive analysis (Creswell, Citation2003) to consider multiple viewpoints, perspectives and positions (Johnson et al., Citation2007). However, whilst this research was satisfactory, it effectively reinforced the status quo and did not dig beneath the surface of ‘taken-for-granteds’ (Harvey, Citation2022a, p. 2).

Reflecting on this fragmentation and problematisation, a subsequent four-year longitudinal narrative study, which began in 2010, aimed to listen to students describe their experiences at a range of points within their studies (Hamshire & Wibberley, Citation2014; Hamshire & Jack, Citation2016). The student narratives collected during this study portrayed how individual students interpreted and narrated their experiences of being a student and whilst there were varieties, variance and difference, they also overlapped and commonalities could be identified (Hamshire & Wibberley, Citation2014). Four significant themes were identified as having a significant impact on the students’ engagement: peer support, finances, learner development and personal circumstances; and the findings underlined the importance of listening to students to understand their experiences. This research also noted the difficulties of exploring the complexity of individual stories when students are sampled at single points in time and only a ‘temporal slice’ of their experiences is considered (Hamshire et al., Citation2017).

Building on the findings from these studies, the authors were awarded funding for a large-scale, regional, mixed-methods project that combined an extensive analysis of regional student training database data with a second phase of focused analysis of students’ experiences and perceptions using survey and interview data, to identify the factors that had an impact on progression. This ‘PASS project’ was funded by Health Education England and combined data from students at eleven institutions in the Northwest of the UK (Hamshire et al., Citation2017; Jack et al., Citation2018; Harris et al., Citation2019). The purpose of this study was to explore student success and retention to gain greater understanding of what influenced students’ experiences and to develop a benchmarking tool (Langan et al., Citation2015; Harris et al., Citation2019).

Stakeholders from higher education institutions, practice placements, regional networks and students were all given opportunities to identify social and historical issues and develop incremental solutions within the PASS project. Students’ voices and experiences were given prominence throughout the data collection processes via both a survey and in-depth narrative interviews to ensure that their lived experiences of being a student were considered as a more holistic system issue rather than focusing on individual student characteristics. Ultimately, the project was focused on exploring students learning experiences through continuous quality improvement to provide:

systematic comparison of performance across programmes and institutions, allowing a better understanding of relative performance;

a comparison of relative sector or programme averages;

a process of self-evaluation and self-improvement by institutions using standardised metrics;

identification of institutional ‘position’ in comparison to others, strengths and weaknesses, and best practice across the region.

The complexity of the student responses indicated that there was a need to improve systems and support across the range of interactions and services that contribute to their experiences. To do this effectively, the impact of systemic change on staff and institutional micro-cultures also needed to be considered and a staff development programme devised. This complex multi-system change was being explored within strand 2 of this concatenated work and the findings from both strands were used to inform the development of the other.

Strand 2: managing complex multi-system change in a university

In 2008, the authors began work on a university-wide quality enhancement project to restructure the curriculum (Bird et al., Citation2015). The overarching aim was to make the university more responsive to the needs of stakeholders, particularly students, employers and professional bodies. The project baseline report reported broad agreement that curriculum change was needed but that this was hampered by:

overly bureaucratic processes;

competing demands on staff;

conflicting time cycles in different parts of the university;

unclear lines of responsibility for curriculum change;

lack of sense of personal ownership;

inertia, owing either to the scale of the task or to the existence of long-established and effective ‘work-arounds’ in some areas (Bird et al., Citation2015).

The original improvement goals were to simplify and align processes, clarify responsibilities and enable a flexible approach to curriculum review and change.

At the beginning of the project, the university leadership made some decisions about major changes to the curriculum structure which were to be implemented across the university. The proposed changes were intended to provide a common structure for curriculum design, to provide more flexibility in the choice of modules for students and to enable the implementation of university-wide systems for timetabling, learning management systems and library integration. The systematic change created a singular credit structure, with all module leaders required to rewrite the module specifications and, in many cases, combine different modules, requiring much explanation, cultural change and staff development across the organisation.

Inevitably, staff were concerned about the changing systems that had been in place since the university had had a different, less independent, form of governance. Many members of both teaching and administrative staff were sceptical about the chances of success with such huge changes. This has been characterised as ‘holistic paralysis’ (Ericson, Citation1970), or ‘we can’t change anything because we’d have to change everything’ (Bird et al., Citation2015). To facilitate the change process an evidence base, using a wide range of existing data, such as student satisfaction, student continuation, graduate employment, staff workloads and assessment sizes was reviewed, alongside workshops involving staff and students from across the institution. This work revealed complex interdependencies and varied curriculum change processes across campuses, disciplines and cohort characteristics.

Many lessons were learned from this experience of the complexities of, and anxieties caused by, large-scale change in universities leading the team to identify two very specific recommendations.

Academic decisions must be made at the level of the department or programme team wherever possible and systems should be designed to make this possible.

The project team needs to make changes as small and easy to execute as possible.

In 2011, a project was launched to improve assessment management (TRAFFIC), using all of the lessons learned about collaboration from the curriculum project and the student experience research in Strand 1. Students, as significant stakeholders, were meaningfully represented in all working groups, contributing to decisions about assessment types and formats, criteria, feedback policies, extensions for late work and appeals processes. There was a significant shift to a more student-centred approach. Regulations and guidance were updated to reflect latest research in assessment literacy and institutional-level changes were kept to a minimum, with a focus on developing staff skills in designing and managing assessment in a valid, reliable and secure way.

Alongside this systems development, a further project explored staff narratives of first-generation students’ experiences (Forsyth et al., Citation2022; Hamshire et al., Citation2021). The purpose of this study was to explore whether a mismatch between staff perceptions and students’ experiences might be a possible contributor to inequalities in student success. The study explored and compared staff discourses about the experiences of first-generation students at two universities, one in the UK and the other in South Africa. While staff identified system issues that contributed to these disparities, they were unsure of their own roles in relation to developing processes to shape an inclusive environment (Forsyth et al., Citation2022).

One core element of these projects was a policy change on supporting decision-making at the closest possible point to teaching (Forsyth et al., Citation2015, Citation2024) minimising top-down regulations. Achieving this required a process of iteration of proposals through cycles of presentation and active discussion with stakeholders, as indicated in the wicked framework model.

Using the findings of each of these projects, a significant programme of staff development was designed and implemented, using many different approaches to persuade colleagues of the value of the changes. Cornford and Pollock (Citation2003) described the importance of lateral relationships in bringing about change in universities: not only within teams but between professional and academic staff, as well as between staff and students. During this project, considerable work went into facilitating these lateral relationships and better mutual understanding of roles and responsibilities. Techniques used included the design of games to depersonalise the introduction to difficult decisions (Hamshire & Forsyth, Citation2013) and the use of scenarios to capture complex student experiences (Hamshire et al., Citation2021).

Bringing the two strands of research together

A key element of the concatenated approach was to link new projects to previous ones, showing coherence in institutional strategy and acknowledgement of existing skills and knowledge. In the case of the work reported here, the core theme was the adaptation of teaching, assessment and institutional management systems to the needs of a diverse student population. Through these consecutive projects, there was a natural progression from the problematisation of students (their diversity requires special adaptations) to the problematisation of cultures (our systems exclude or create barriers for some students).

In 2019, the authors began a project to improve the experiences of students from historically marginalised backgrounds, which was designed from the beginning to foreground students’ perceptions of their experiences to make systemic improvements to attitudes, processes and procedures. This student-led project provided a structure for acknowledging and improving situations and approaches that had led to inadvertent but real impact on students’ sense of belonging and ability to achieve in the university. Using the learning from the previous projects, the institutional culture was problematised from the beginning but without criticism or judgement of the existing situation and with a focus on deconstructing dominant discourses and reconstructing an understanding that identified the social and historical interrelationships (Harvey, Citation2022a, Citation2023). The focus was on how to articulate and use shared values to take collective ownership of what evidence showed to be a real problem: the difference in achievement of students with different personal characteristics, particularly for students from historically minority backgrounds.

The core activities of this project included listening events with both staff and students to explore lived experiences (Gamote et al., Citation2022; Hamshire et al., Citation2023). The key elements that enabled this institution-wide change were aligned with the general model for wicked problem management (Hamshire et al., Citation2019) and included the following.

Student and staff perceptions of their experiences led all interventions.

The current situation was critiqued but without criticising individual people or previous actions: the focus was on solving the wicked problem.

Actions were reviewed regularly and discussed with all stakeholders, leading to changes in approach or processes.

The project focused on changing the culture to one in which all activities are reviewed in relation to student and staff perceptions, rather than on simply fixing the original problem.

This changed culture was intended to include widespread understanding that there would never be a stopping point to quality improvement.

Conclusions and recommendations

Enhancing a quality culture in higher education is complex. Addressing longstanding problems and finding sustainable solutions requires longitudinal, inclusive approaches that value all stakeholders and consider the impact of multiple interacting systems. One challenge is a lack of perceived ownership (Legemaate et al., Citation2022) and a second is an inherent conservatism in relation to organisations: traditional curriculum and assessment structures have been in place in recognisable format for centuries and there is a natural reluctance to change what has previously worked. Despite considerable research on quality cultures, there are limited studies on the potential of a systems approach to quality enhancement (Legemaate et al., Citation2022) and quality enhancement projects frequently rely on short-term, fragmented studies implemented in response to snapshot data.

The two strands of research presented within this article highlight some of the inherent social and cultural complexity of cultural change across stakeholder groups. Acknowledging this complexity as well as valuing historical voices, in partnership with all stakeholders, enables us to focus on developing incremental solutions (Hamshire et al., Citation2019). Fundamental to this process, there needs to be a recognition of the multifaceted intersections of student and staff experience and an acknowledgment of the unintended consequences of change, ensuring that investment in large-scale institutional changes is effective. Working within complex systems, staff can perceive that the solution to challenges is for students to adapt and change to fit in with a conventional institutional culture rather than substantial changes in institutional approach (Forsyth et al., Citation2022).

Quality enhancement processes and systems have multiple purposes, including public accountability, the improvement of teaching, learning and assessment and portfolio management. Over the last twenty years, there has been a significant increase in the use of both learning analytics and performance indicators to reconnect learning to quality assurance (Harvey, Citation2022b), however, if learning and teaching is to be improved for the individual student, it is necessary to recognise the importance of listening to students as valued stakeholders and move away from problematising the students to problematising the systems. Re‐conceptualising quality as a systems problem, facilitates long-term holistic change by identifying overarching themes that may be driving the change management agenda and avoiding the repetition of modest solutions. To facilitate long-term systemic change, it is therefore vital to stop reporting on single case studies and take a longer view that allows for the review and reframing of problems with the participation of diverse stakeholders.

Within the examples given here, engagement with students and staff demonstrated that an intentional approach to linked quality enhancement projects was key to the successful implementation of initiatives. This approach can be used to co-create actions, building trust in the cultural changes needed for long-term improvements. When colleagues and students believed in the motivation for the changes, they were able to adapt interventions using their own skills and experience. As with the projects detailed here, it may take some time for the links between projects to become apparent, so a prospective concatenated research study may not be the initial design. However, it is valuable to consider the possibility of this whenever universities are embarking on institutional change in response to complex external and internal drivers. An intentional approach to learning from each complex intervention ensures that project teams establish a commitment to considering and learning from local conditions and expertise. This process demonstrates to staff that such interventions are an integral and inevitable part of continuous quality enhancement in line with university values and not simply individual projects developed in a reactive response to individual data points or government policy.

Effective change management in universities therefore requires incremental intervention with intentional evaluation and review to direct next steps, executive agility (goal change) to enable adaptation; conversations between significant others (and a willingness to consider a wider range of significant others); and a clear focus on shared goals. Staff development needs to be a fundamental element of each project or system change and include listening as well as telling and opportunities to influence projects during their lifetime. Student engagement needs to be meaningful and to focus on what students can bring, rather than relying on simple representation in forums designed for employees. The use of a wicked problem framework allows for all these conditions and considers both the intentional and unintentional consequences of change.

When reviewing quality systems, it is vital to consider all stakeholders at all stages to surface the complexities and interdependencies that can lead to difficulties in the implementation of change. Better quality research and evaluations are therefore needed to strengthen knowledge, in partnership with both students and external third parties, to deconstruct current perceptions, recognise complexity and predict the potential impact of system changes, offering an alternative way of thinking about dynamic quality issues. This approach will allow the consideration of quality as a complex interactions of many interrelated factors and avoids the pitfalls of small-scale interventions and over-simplistic assumptions of cause and effect. This article has provided a framework to conceptualise quality enhancement within a concatenated research approach, using a wicked problem management framework. Using this approach in partnership with diverse stakeholders should result in contextually effective systems and ultimately improve learning and teaching experiences for all students.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Benson, R., 2006, ‘Alternative study modes in higher education: students’ expectations and preferences’, Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 46(3), pp. 337–63.

- Bird, P., Forsyth, R., Stubbs, M. & Whitton, N., 2015, ‘EQAL to the task: stakeholder responses to a university-wide transformation project’, Journal of Educational Innovation, Partnership and Change, 1(2), np.

- Brown, G.D.A., Wood, A.M., Ogden, R.S. & Maltby, J., 2015, ‘Do student evaluations of university reflect inaccurate beliefs or actual experience? A relative rank model’, Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 28(1), pp. 14–26.

- Buckley, A., 2012, Making it Count: Reflecting on the National Student Survey in the process of enhancement (York, Higher Education Academy).

- Burgess, A., Senior, C. & Moores, E., 2018, ‘A 10-year case study on the changing determinants of university student satisfaction in the UK’, PLOS ONE, 13(2), pp. 1–15

- Cardoso, S., Rosa, M.J. & Stensaker, B., 2015, ‘Why is quality in higher education not achieved? The view of academics’, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 41(6), pp. 1–16.

- Cornford, J.R. & Pollock, N.P., 2003, Putting the University Online: Information technology and organizational change (Maidenhead, Oxford University Press).

- Creswell, J.W., 2003, Research Design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method approaches, second edition (California, Sage).

- Ericson, R.F., 1970, ‘The policy analysis role of the contemporary university’, Policy Sciences, 1(1), pp 429–42.

- Forsyth, R. & Cullen, R., 2016, ‘“You made me fail my students!”: tensions in implementing new assessment procedures’, paper presented at the SEDA Spring Learning and Teaching Conference [Staff and Educational Development Association], Edinburgh, Scotland, 12–13 May.

- Forsyth, R., Cullen, R., Ringan, N. & Stubbs, M., 2015, ‘Supporting the development of assessment literacy of staff through institutional process change’, London Review of Education, 13(3), pp. 34–41.

- Forsyth, R., Cullen, R. & Stubbs, M., 2024, ‘Implementing electronic management of assessment and feedback in higher education’ in Evans, C. & Waring, M. (Eds.), 2024, Research Handbook on Innovations in Assessment and Feedback in Higher Education (Cheltenham, Elgar).

- Forsyth, R., Hamshire, C., Fontaine-Rainen, D. & Soldaat, L., 2022, ‘Shape-shifting and pushing against the odds: staff perceptions of the experiences of first generation students in South Africa and the United Kingdom’, The Australian Educational Researcher, 49(2), pp. 307–21.

- Gamote, S., Edmead, L., Stewart, B., Patrick, T., Hamshire, C. & Forsyth, R., 2022, ‘Student partnership to achieve cultural change’, International Journal for Students as Partners, 6(1), pp. 99–108.

- Hamshire, C. & Cullen, R., 2010, ‘Developing a spiralling induction programme: a blended approach’ in Anagnostopoulou, K. & Parmar, D. (Eds.), 2010, Supporting the First Year Student Experience through the Use of Learning Technologies (York, Higher Education Academy).

- Hamshire, C. & Cullen, W.R., 2014, ‘Providing students with an Easystart to higher education: the emerging role of digital technologies to facilitate students’ transitions’, International Journal of Virtual and Personal Learning Environments, 5(1), pp. 73–87.

- Hamshire, C. & Forsyth, R., 2013, ‘Contexts and concepts: crafty ways to consider challenging topics’, in Whitton, N. & Moseley, A., (Eds), 2013, New Traditional Games for Learning: A case book (London, Routledge).

- Hamshire, C., Forsyth, R., Bell, A., Benton, M., Kelly-Laubscher, R., Paxton, M. & Wolfgramm-Foliaki, E., 2017, ‘The potential of student narratives to enhance quality in higher education’, Quality in Higher Education, 23(1), pp. 50–64.

- Hamshire, C., Forsyth, R., Khatoon, B., Soldaat, L. & Fontaine-Rainen, D., 2021, ‘Challenging the deficit discourse’, in Ralarala, M.K., Hassan, S.L. & Naidoo, R. (Eds.), 2021, Knowledge Beyond Colour Lines: Towards repurposing knowledge generation in South African higher education (Volume 2, Edition 1) pp. 151–68, (Stellenbosch, African Sun Media).

- Hamshire, C., Forsyth, R. & Player, C., 2018, ‘Transitions of first generation students to higher education in the United Kingdom’, in Bell, A. & Santamaria, L.J. (Eds.), 2018, Understanding Experiences of First Generation University Students: Culturally responsive methodologies, pp. 121–42 (London, Bloomsbury).

- Hamshire, C., Gamote, S., Norman, P., Forsyth, R. & McCabe, O., 2023, ‘Working towards the inclusive campus: a partnership project with students of colour in a university reform initiative’, in Conner, J., Gauthier, L., Valenzuela, C.G. & Raaper, R. (Eds.), 2023, The Bloomsbury Handbook of Student Voice in Higher Education, pp. 163–78 (London, Bloomsbury).

- Hamshire, C. & Jack, K., 2016, ‘Becoming and being a student: a Heideggerian analysis of physiotherapy students’ experiences’, The Qualitative Report, 21(10), pp. 1904–19.

- Hamshire, C., Jack, K., Forsyth, R., Langan, A.M. & Harris, W.E., 2019, ‘The wicked problem of healthcare student attrition’, Nursing Inquiry, 26(3), pp 1–8.

- Hamshire, C. & Wibberley, C., 2014, ‘The listening project: physiotherapy students narratives of their higher education experiences’, in Bryson (Ed.), 2014, Understanding and Developing Student Engagement (London, Routledge).

- Hamshire, C., Willgoss, T.G. & Wibberley, C., 2012a, ‘Mind the gaps: health professions students views of support systems’, Widening Participation and Lifelong Learning, 14(1), pp. 108–27.

- Hamshire, C., Willgoss, T.G. & Wibberley, C., 2012b, ‘“The placement was probably the tipping point”—The narratives of recently discontinued students’, Nurse Education in Practice, 12(4), pp. 182–86.

- Hamshire, C., Willgoss, T.G. & Wibberley, C., 2013a, ‘Should I stay or should I go? A study exploring why healthcare students consider leaving their programme’, Nurse Education Today, 33(8), pp. 889–95.

- Hamshire, C., Willgoss, T.G. & Wibberley, C., 2013b, ‘What are reasonable expectations? Healthcare student perceptions of their programmes in the North West of England’, Nurse Education Today, 33(2), pp. 173–79.

- Harris, W.E., Langan, A.M., Barrett, N., Jack, K., Wibberley, C. & Hamshire, C., 2019, ‘A case for using both direct and indirect benchmarking to compare university performance metrics’, Studies in Higher Education, 44(12), pp. 2281–92.

- Harvey, L., 2022a, ‘Critical social research: re-examining quality’, Quality in Higher Education, 28(2), pp. 145–52.

- Harvey, L., 2022b, ‘Editorial’, Quality in Higher Education, 28(1), 1–5.

- Harvey, L., 2023, ‘Editorial: Critical social research’, Quality in Higher Education, 29(3), pp. 280–83.

- Jack, K., Hamshire, C. & Chambers, A., 2017, ‘The influence of role models in undergraduate nurse education’, Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26(23–24), pp. 4707–15.

- Jack, K., Hamshire, C., Harris, W.E., Langan, M., Barrett, N. & Wibberley, C., 2018, ‘“My mentor didn’t speak to me for the first four weeks”: perceived unfairness experienced by nursing students in clinical practice settings’, Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(5–6), pp. 929–38.

- Johnson, R.B., Onwuegbuzie, A.J. & Turner, L.A., 2007, ‘Towards a definition of mixed methods research’, Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 2(1), pp. 112–33.

- Kaçaniku, F., 2020. ‘Towards quality assurance and enhancement: the influence of the Bologna Process in Kosovo’s higher education’, Quality in Higher Education, 26(1), pp. 32–47.

- Kandiko, C.B. & Mawer, M., 2013, Student Expectations and Perceptions of Higher Education (London, King's Learning Institute).

- Langan, A.M., Scott, N., Partington, S. & Oczujda, A., 2015, ‘Coherence between text comments and the quantitative ratings in the UK’s National Student Survey’, Journal of Further and Higher Education, 41(1), pp. 16–29.

- Legemaate, M., Grol, R., Huisman, J., Oolbekkink–Marchand, H. & Nieuwenhuis, L., 2022, ‘Enhancing a quality culture in higher education from a socio-technical systems design perspective’, Quality in Higher Education, 28(3), pp. 345–59.

- Pohl, C., Truffer, B. & Hirsch-Hadorn, G., 2017, ‘Addressing wicked problems through transdisciplinary research’, in Frodeman, R. (Ed), 2017, The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity, pp. 319–31 (Oxford, Oxford University Press).

- Prowse, A. & Forsyth, R., 2017, ‘Global citizenship education—assessing the unassessable?’, in Davies, I., Ho, L.-C., Kiwan, D., Peck, C., Peterson, A., Sant, E. & Waghid, Y. (Eds.), 2017, The Palgrave Handbook of Global Citizenship and Education (London, Palgrave).

- Rittel, H.W. & Webber, M.M., 1973, ‘Dilemmas in a general theory of planning’, Policy Sciences, 4(2), pp. 155–69.

- Roberts, N., 2000, ‘Wicked problems and network approaches to resolution’, International Public Management Review, 1(1), pp. 1–19.

- Roxå, T. & Mårtensson, K., 2015, ‘Microcultures and informal learning: a heuristic guiding analysis of conditions for informal learning in local higher education workplaces’, International Journal for Academic Development, 20(2), pp 193–205.

- Sabin, M., 2012, ‘Student attrition and retention: untangling the Gordian knot’, Nurse Education Today, 32(4), pp 337–38.

- Sherman, J. & Peterson, G., 2009, ‘Finding the win in wicked problems: lessons from evaluating public policy advocacy’, The Foundation Review, 1(3), pp. 87–99.

- Skinner, K., 2014, ‘Bridging gaps and jumping through hoops: first-year history students’ expectations and perceptions of assessment and feedback in a research-intensive UK university’, Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 13(4), pp. 359–76.

- Stebbins, R.A., 1992, ‘Concatenated exploration: notes on a neglected type of longitudinal research’, Quality and Quantity, 26(4), pp. 435–42.

- Stebbins, R.A., 2001, Exploratory Research in the Social Sciences (Thousand Oaks, Sage).

- Thompson, J. & Houston, D., 2024, ‘Resolving the wicked problem of quality in paramedic education: the application of assessment for learning to bridge theory-practice gaps’, Quality in Higher Education, 30(1) pp. 1–18, published online 18 Oct 2022.