ABSTRACT

The Protective + Risk Observations For Eliminating Sexual Offense Recidivism (PROFESOR) is designed to identify risk and protective factors for individuals aged 12–25 who have engaged in, or have been accused of engaging in, illegal or otherwise abusive sexual behaviour. Unlike most risk assessment tools which are designed to predict the future, the PROFESOR is designed to identify dynamic protective and risk factors that can inform interventions that will facilitate sexual and relationship health and, thus, eliminate sexual offense recidivism. The rationale for the development of the PROFESOR is outlined, and an investigation of the tool’s reliability is presented. For this study, 58 individuals (aged 12–20 years; M = 16.3; SD = 1.63) in residential treatment for male youth who have engaged in sexually harming behaviour were rated by a pair of clinicians from a group of 15 clinicians (therapists and their supervisors). Unlike typical investigations of interrater agreement where a small number of raters utilise identical file material, PROFESOR ratings were made based on the clinicians’ working knowledge of the individuals in their care. Excellent interrater agreement was demonstrated with the Total score, as were significant item-total correlations and internal consistency estimates, indicating encouraging evidence of the reliability of the PROFESOR.

PRACTICE IMPACT STATEMENT

This paper identifies the limitations of risk prediction tools for adolescent sexual recidivism and outlines the rationale for the development of the PROFESOR, an assessment tool designed to inform intervention goals and intensity by identifying both risk and protective factors. Data from therapists and supervisors at a residential treatment facility indicated encouraging evidence of the reliability (i.e. interrater agreement, item-total correlation, and internal consistency) of the PROFESOR.

Rationale for the development of the PROFESOR

It was long held that individuals who offended sexually are similar in many respects and that they are necessarily at a high risk of reoffending sexually, simply because of the nature of their criminal behaviour (Williams et al., Citation2015). Prior to 1990, therefore, there were very few structured assessment tools specifically addressing risk factors for sexual recidivism. With the dissemination of the Risk-Need-Responsivity (RNR) model in 1990 (Andrews et al., Citation1990), where it was argued that treatment for individuals involved in the criminal justice system is more successful if there is a match between the number of risk factors and treatment intensity, there has been a significant focus on the development of tools designed to identify risk factors, with a concomitant zeal to employ these tools to predict future risk within the criminal justice systems in the U.S., Canada, and the UK (Craig & Rettenberger, Citation2016). Efforts to develop tools that could predict sexual reoffending were also likely accelerated, at least in part, by the Citation1998 meta-analysis by Hanson and Bussière which identified a number of factors that were correlated (although primarily with small effect sizes) with adult male sexual recidivism. The push to develop reliable and valid risk prediction tools for sexual recidivism was also likely further influenced by the adoption of registration and community notification policies in the U.S. in the 1990s. Although these policies were originally developed for adults who offended sexually, many U.S. states applied registration and notification requirements to youth who offended sexually (Harris et al., Citation2016), and some U.S. states have utilised risk prediction tools to make decisions regarding registration and community notification for youth (e.g. Blasko et al., Citation2011).

The use of risk prediction tools for adolescent sexual recidivism increased substantially throughout the years such that, by 2009, 80% of treatment programmes in the U.S., for example, were using one or more of the available tools (McGrath et al., Citation2010). Two risk assessment tools in widespread use in the U.S. at that time were the Juvenile Sex Offender Assessment Protocol—II (J-SOAP-II; Prentky & Righthand, Citation2003) and the Estimate of Risk of Adolescent Sexual Offense Recidivism (ERASOR; Worling & Curwen, Citation2001), and these tools continue to be widely used both in the U.S. and internationally (e.g. Krause et al., Citation2021; Prentky & Righthand, Citation2021).

In their meta-analysis of the predictive accuracy of these popular risk assessment tools, Viljoen et al. (Citation2012) found that the average area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) was approximately 0.66. Therefore, it is only 66% of the time, on average, that a randomly selected recidivist would have a higher score on these tools when compared to the score for a randomly selected nonrecidivist. This also means that, on average, approximately one third of the time, it is actually a randomly selected nonrecidivist who has the higher score. Not surprisingly, Viljoen et al. (Citation2012) concluded that, although these measures provide estimates of future offending that are above chance levels, the predictive validity is insufficient for predictions that require a high degree of precision. There are a number of additional tools that have been designed to predict adolescent sexual recidivism, and moderate effect sizes regarding their predictive accuracy are also commonly reported (e.g. Kim et al., Citation2019; Rasmussen, Citation2018; Rojas & Olver, Citation2019).

It is important to stress here, however, that moderate effect sizes are not unique to predictions of future sexual offending behaviour by adolescents. Moderate levels of predictive accuracy are also typically reported in meta-analytic investigations regarding predictions of adult sexual recidivism (e.g. Hanson & Morton-Bourgon, Citation2009; Helmus et al., Citation2022; van den Berg et al., Citation2018). Moderate predictive validity is also typically found for tools designed to predict other forms of antisocial behaviour, such as intimate partner violence (e.g. van der Put et al., Citation2019), youth and adult interpersonal violence (e.g. Fazel et al., Citation2012), youth criminal behaviour (e.g. Olver et al., Citation2009; Schwalbe, Citation2007), and child maltreatment by parents/caregivers (e.g. van der Put et al., Citation2017), for example. Furthermore, it is not just antisocial or violent (including sexual) behaviour that is difficult to predict, as similarly poor predictive accuracy has been found in meta-analyses regarding other human behaviours, such as suicidal behaviour (e.g. Carter et al., Citation2017), agricultural accidents (e.g. Jadhav et al., Citation2015), traffic accidents (e.g. Barraclough et al., Citation2016), hospital readmissions (e.g. Kansagara et al., Citation2011), and adherence to treatment for chronic illnesses (e.g. Rich et al., Citation2015), for example.

When attempting to predict future sexual recidivism, it is also critical to be mindful of the base rate of sexual reoffending for adolescents, as this impacts the utility of any risk-prediction measure. In a meta-analysis of 106 samples of adolescents who had offended sexually, Caldwell (Citation2016) reported an average sexual recidivism rate of approximately 5% over 5 years. With such a low base rate, accurate predictions of “low” risk (negative predictive power) will consistently be much more likely than accurate predictions of “high risk” (positive predictive power). Indeed, with an estimated base rate of 5%, if one were to predict that every adolescent who had offended sexually was at “low risk” to reoffend sexually over the next five years, then one would be correct approximately 95% of the time, on average. Current best-practice guidelines caution practitioners that existing risk prediction tools for adolescent sexual recidivism can result in erroneous conclusions regarding future sexual offending behaviour; particularly for longer-term predictions (ATSA, Citation2017).

Another significant limitation of the popular risk assessment tools noted above is that, depending on the measure, between one third and 100% of the risk factors are static (i.e. historical factors that cannot change). This is particularly problematic for follow-up assessments, as static risk factors will always be present, regardless of any intervention, maturation, and/or the passage of time. For example, if an adolescent has ever offended sexually against a stranger, this will always be present—regardless of any changes that the individual makes through intervention. Furthermore, how does it inform treatment to know that someone has offended sexually against a stranger in the past? For some adolescents, the number of risk factors on these risk assessment measures may actually increase as a result of intervention, as it is not uncommon for adolescents to disclose additional, historical offenses through the course of treatment (Baker et al., Citation2001), and this can impact the coding of static, or historical, risk factors.

An additional limitation with most risk assessment tools designed for youth who have offended sexually is that they can only be used with a narrow age range (typically a span from age 12–18). This makes it difficult to follow up older adolescents over time using a consistent tool. For example, if a 17-year-old client begins an intervention, what risk assessment tool should be used when the client turns 19? Additionally, given that there is often a lengthy delay if sexual victimisation is eventually disclosed (e.g. Ahrens et al., Citation2010), what tools would practitioners use with emerging adults (Arnett, Citation2000) aged 18–25 who offended sexually when they were young teens? Also, one may reasonably question how well emerging adults are represented in the normative samples for tools designed for adults who have sexually offended. For example, the Static-99R (Helmus et al., Citation2012) is a popular risk prediction tool for adult sexual recidivism, and, according to the Static-99R website (www.static99r.org), the mean age for samples utilised for the norms for that tool was 40 (SD = 12). Users of the Static-99R are also cautioned not to use the tool with adolescents who offended sexually unless the adolescents offended at age 17, were released at age 18 or over, and the offending behaviour “appears similar in nature to typical sex offences committed by adult offenders” (Phenix et al., Citation2016, p. 18).

There are also limitations to the use of these popular risk assessment tools for adolescents with respect to the nature of the sexual offending behaviour. For example, none of the popular tools for adolescent sexual recidivism mentioned above are designed to be used when the illegal sexual behaviour is related to the sexual abuse of an animal or to the possession of, and/or distribution of, child sexual exploitation materials, as information regarding the person(s) who was directly victimised is typically required for coding purposes (e.g. age and gender of the victimised person). Given the increasing number of youth being charged with possession and/or distribution of child sexual exploitation materials (King & Rings, Citation2022), it is important to have assessment tools that can be utilised with this subgroup.

Another crucial limitation of the popular risk assessment tools for adolescent sexual recidivism reviewed by Viljoen et al. (Citation2012) is that they are made up exclusively of risk factors—i.e. they contain no protective factors (i.e. factors that protect against recidivism). It is now widely held that assessment and intervention for individuals who have offended sexually should be focused on both risk and protective factors (e.g. ATSA, Citation2017; Langton & Worling, Citation2015; Thornton, Citation2013). The Assessment, Intervention, and Moving On approach (AIM; Print et al., Citation2001) was one of first risk assessments for adolescent sexual offending behaviour to incorporate both risks and strengths. The revised AIM2 checklist was widely used in the U.K. (Griffin et al., Citation2008), and it is now in its third revision (AIM3; Leonard & Hackett, Citation2019). Currently, data regarding the psychometric properties of the most recent iteration of the AIM are limited to a study of the interrater agreement based on a Norwegian translation of the AIM3 (Jensen et al., Citation2022).

Design of the PROFESOR

To address some of the limitations of exiting risk assessment tools, the Protective + Risk Observations For Eliminating Sexual Offense Recidivism (PROFESOR; Worling, Citation2017) was developed as an alternative tool for mental health and criminal justice professionals to assess youth and emerging adults (i.e. those aged 12–25) who have engaged in sexually abusive behaviour and/or otherwise illegal sexual behaviour. Rather than an attempt to predict the future, the PROFESOR was designed to identify both risk and protective factors that would inform interventions (i.e. treatment, supervision, support) to facilitate healthy sexual and interpersonal relationships. In the same spirit as Youth Level of Service/Case Management Inventory (YLS/CMI; Hoge & Andrews, Citation2011), a risk/need assessment tool for youth who have engaged in illegal behaviour, the PROFESOR was designed to identify specific intervention targets—in addition to providing an overall rating of the recommended intensity of intervention.

The PROFESOR is an adaptation and extension of the Desistance for Adolescents who Sexually Harm-13 (DASH-13; Worling, Citation2013), a measure of protective factors for youth who have engaged in sexually abusive behaviour. Preliminary research has yielded some supportive evidence of the reliability and validity of the DASH-13 (Langton, Awrey, et al., Citation2023; Vivar et al., Citation2021; Zeng et al., Citation2015); however, there are several limitations with the DASH-13. First, the DASH-13 contains only 13 items, and there are important protective factors that are missing on that tool (e.g. prosocial values and attitudes, healthy self-esteem, and positive parent/caregiver practices). Second, the coding instructions for each item are very brief, thus increasing the subjectivity in ratings. Third, the DASH-13 contains only protective factors, and it is not clear how one would combine the results of the DASH-13 with the results from a risk-prediction tool. For example, if an individual is rated as “high risk” using the ERASOR, does this somehow change to “moderate risk” if there are a certain number of protective factors identified with the DASH-13?

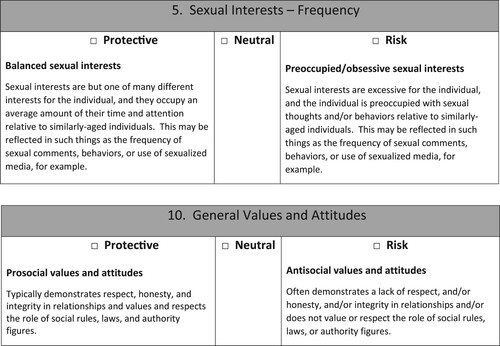

The PROFESOR contains 20 factors (see ), each with a risk and a protective pole, and 11 of the 13 protective factors from the DASH-13 were included as protective poles for 11 of the 20 factors on the PROFESOR. Coding guidelines were developed for each of the 20 factors (available at www.profesor.ca) so that users can rate each factor as Protective, Risk, or Neutral (i.e. neither clearly Protective nor Risk). Example coding guidelines are displayed in .

Table 1. PROFESOR Factors with Protective and Risk Poles.

Factors for the PROFESOR were chosen by the first author based on the extant literature regarding risk factors (e.g. Beech & Ward, Citation2004; Mann et al., Citation2010; McCann & Lussier, Citation2008; Worling & Långström, Citation2003) and protective factors (e.g. Carpentier et al., Citation2011; de Vries Robbé et al., Citation2015; Thornton, Citation2013; van der Put & Asscher, Citation2015) for sexual recidivism. Although some factors identified in the literature are applicable almost exclusively to adults (e.g. marital status and employment engagement), and others are more specific to adolescents (e.g. school engagement, parent–child relationships), most factors related to sexual recidivism and desistance identified in the literature (e.g. sexual interests, sexual attitudes, self-regulation, relationships with others, engagement in leisure activities) are applicable to both age groups (Worling & Langton, Citation2022), although the factors will necessarily be operationalised differently depending on the client’s age. For example, indicators for the presence of an emotionally intimate friendship (protective factor) or sexual preoccupation (risk factor) will look quite different for a 14-year-old versus a 24-year-old individual. Coding the PROFESOR therefore requires sensitivity to developmental considerations.

Given that the focus of the PROFESOR is to inform intervention goals, all 20 factors are dynamic and are coded based on how the individual has functioned throughout the most recent 2 month period. Factors on the PROFESOR are related to aspects of both sexual (e.g. sexual interests, sexual attitudes) and general (e.g. compassion for others, self-control) functioning. Furthermore, factors on the PROFESOR reflect characteristics at the individual (e.g. self-esteem, problem solving), relational (e.g. emotional intimacy/friendship, parent/caregiver relationship), and environmental (sexualised environment, living arrangement) level. Evaluators are encouraged to complete the PROFESOR using multiple sources of information, such as interviews with the individual, interviews with collateral sources (e.g. parents/caregivers, partners, support persons), document review, and psychological testing (when available and appropriate). After coding the 20 PROFESOR factors, evaluators can then calculate (based on the relative distribution of Protective, Risk, and Neutral ratings; see for relevant formulae) which of the five categories the individual would be placed in with respect to the suggested intensity of intervention. Given the dynamic nature of the PROFESOR, the tool can be used to inform intervention goals at any point during the therapeutic process. Even when treatment has ended, for example, it would be informative to know what factors remain rated as either Risk or Neutral and, therefore, in need of some level of intervention. It would also be important to speak to the components that need to be put into place to maintain those factors rated as Protective.

Table 2. PROFESOR Category Assignment and Interpretation.

Investigation of the reliability of the PROFESOR

This study represents the initial phase of a larger, prospective investigation of the reliability and validity of the PROFESOR. The primary goal for this phase of the investigation was to examine the interrater reliability of the PROFESOR in an applied context. Rather than the more typical study of interrater agreement where two trained raters code an instrument using the identical file material, the aim of this investigation was to examine the interrater reliability of the PROFESOR under more naturalistic conditions (i.e. multiple professionals completing the tool based on their current, working knowledge of the client). In addition to overall interrater agreement, we also wanted to determine whether the quality of the information utilised by the raters impacted reliability. The second goal of this investigation was to examine two additional forms of reliability of the PROFESOR: namely item-total correlations and an estimate of internal consistency.

Method

Participants

All therapists and supervisors involved in the provision of specialised treatment for youth who had engaged in sexually abusive behaviour agreed to participate in this investigation. This resulted in the collection of PROFESOR ratings from ten therapists and their five direct supervisors. Prior to data collection, all raters participated in a full-day training with the first author. Training was focused on the application of the PROFESOR coding rules—including practice with numerous examples. The training also included a discussion of the importance of assessment and an outline of techniques for assisting clients to talk about potentially embarrassing topics (e.g. sexual interests and masturbatory behaviour). Following the training, and prior to data collection, therapist and supervisor pairs met with the first author for approximately one hour to review a practice case and to clarify any questions or issues regarding the PROFESOR coding rules.

With respect to previous experience in the field, two of the therapists had up to two years’ experience working with youth who had engaged in sexually harming behaviour, whereas the remaining eight therapists had three or more years experience. All of the supervisors had worked in the field for over three years. Prior to data collection regarding interrater reliability, five of the therapists had completed ten or fewer PROFESORs; the remaining five therapists had previously completed 11 or more PROFESORs. All of the supervisors completed over 10 PROFESORs prior to providing ratings for this study.

Procedures

As noted earlier, unlike most evaluations of interrater agreement, where a pair of raters utilise the identical file information, therapists and supervisors were asked to complete the PROFESOR based on their current working knowledge of the youth. In their roles at the treatment facility, therapists had regular, individual therapy sessions with the youth, whereas the supervisor’s knowledge of the youth was based on a combination of a review of referral documentation, supervisory meetings with the therapist, and observations of, and conversations with, the youth in their treatment centre. Therapists and supervisors completed their ratings independently and blind to each others’ ratings.

To address the question of whether the quality of information impacts interrater reliability, therapists and supervisors independently rated their level of knowledge of the clients’ current (i.e. throughout the past 2 months) functioning on a scale from 1 (poor) to 10 (excellent). They also provided a rating for how much they agreed (1 = strongly disagree and 10 = strongly agree) that their knowledge of the client was based on comprehensive information (e.g. therapy sessions, milieu interactions, assessments, family meetings, school engagement, etc.).

Therapist and supervisor pairs completed the PROFESOR for 58 individuals aged 12–20 years (M = 16.3; SD = 1.63). All 58 individuals were in a residential treatment programme in the U.S. designed for male youth who had engaged in harming sexual behaviour, and all of the adolescents were referred to specialised residential treatment as a result of sexually abusive behaviour that had been documented by child welfare and/or youth justice authorities. With respect to the racial background of the clients, 36 (62%) identified as White, 13 (22%) as Black, 3 (5%) as Hispanic, 3 (5%) as mixed heritage, and 3 (5%) as other/not specified. The intellectual functioning of the clients was identified as Average (85%; n = 49 including Low-Average, Average, and High-Average), Above Average (5%; n = 3), and Intellectually Disabled (10%; n = 6).

Given that the PROFESOR is designed to be utilised at any point during an individual’s intervention, we did not want to limit data collection to a single phase of the treatment process (e.g. just at intake or only at discharge). As such, data were collected by all staff during a brief time period, with PROFESOR ratings made at the point of intake (when youth had only been at the treatment centre for up to 30 days—31%; n = 18), part-way through individuals’ residency (52%; n = 30), or at the point of discharge from the programme (17%; n = 10).

Many of these 58 clients had previous out-of-home placements prior to their arrival at the residential treatment facility. In particular, 62% (n = 36) had previously been in another residential treatment centre, 53% (n = 31) had one or more psychiatric hospitalisations, 50% (n = 29) had been placed in one of more detention facilities, and 33% (n = 19) had one or more foster home placements. Totals do not equal 100%, as youth often had multiple, prior out-of-home placements. Six (10%) of the adolescents identified as transgender females, and this prevalence rate is likely reflective of the finding that transgender youth are overrepresented in out-of-home care placements (Fish et al., Citation2019).

With respect to their concerning sexual behaviours, 62% (n = 36) of the clients had sexually harmed at least one child (defined as an individual 4 or more years younger than the client and under 12 years of age), 47% (n = 27) sexually harmed one or more peers (defined as individuals up to 3 years younger or older than the client), and 7% sexually harmed an adult (defined as individuals 4 or more years older than the client and aged 18 or older). Totals do not equal 100%, as some youth harmed individuals in multiple age categories. In terms of the relationships between the youth and the people whom they had harmed, 67% (n = 39) had sexually harmed one or more family members, 33% (n = 19) harmed nonfamily members, and 10% (n = 6) harmed both familial and nonfamilial individuals. Only 9% (n = 5) of the youth in care sexually harmed one or more strangers.

The specialised treatment for all youth involved weekly individual therapy; group therapy 3 times a week focused on issues related to sexually abusive behaviour and future sexual health; psychoeducational groups 3–4 days a week focused on issues related to intra- and interpersonal health (such as self-esteem, independent living, substance use, and social skills); and family therapy every other week, on average. The overall average length of treatment was approximately 9 months. All procedures for this investigation were approved by the second author’s institutional board.

Results

Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS version 28. For computational purposes, numeric values were assigned to the PROFESOR ratings as follows: Protective = 1, Neutral = 0, and Risk = −1, and values were summed to create a Total score (ranging from 20 to −20). The resultant Total scores ranged from −14 to 16 (M = 1.72; SD = 8.14) for therapists’ ratings and from −12 to 14 (M = 2.55; SD = 7.16) for supervisors’ ratings. Mean Total scores were not significantly different between the two groups of raters, t(57) = −1.43, p (two-tailed) = .157.

Given that the 58 residents were rated by different pairs of therapists and supervisors, intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) were calculated based on the one-way random effects model (McGraw & Wong, Citation1996). The resultant single-measure ICC was 0.83 (95% CI .73, .90), F(57,58) = 10.98, p < .001, and the average-measure ICC was 0.91 (95% CI .85, .95), F(57,58) = 10.98, p < .001. Based on Cicchetti’s (Citation1994) guidelines (i.e. ICCs of < .40 are considered poor, .40 to .59 are fair, .60 to .74 are good, and ≥ .75 are excellent), the overall interrater agreement for the PROFESOR was found to be in the excellent range. Average-measure values are important to consider here, as it is recommended in the User’s Guide for the PROFESOR (available at www.profesor.ca) that, wherever possible, two professionals complete the scale independently and then discuss final ratings.

To determine whether overall interrater agreement was impacted by the quality of the information available to generate the ratings, the two, ten-point items pertaining to this issue (i.e. level of knowledge of the client’s current functioning and the comprehensiveness of that information) were combined to create an overall score representing the degree to which the raters believed that they had complete and comprehensive information. The internal consistency (α) for this two-item scale was 0.92 for the 10 therapists and 0.97 for the 5 supervisors, indicating a high level of interrelatedness between the two items. Scores for this combined knowledge scale ranged from 8 to 20 for the therapists and from 12 to 20 for the supervisors, and the mean scores for the therapists (M = 16.47; SD = 3.47) and supervisors (M = 16.79; SD = 2.59) were similar, t(57) = -.91, p (two-tailed) = 0.37. There were 22 clients where both the therapist and the supervisor had a combined knowledge score above the mean of 16. For these 22 clients where both raters independently indicated that they had complete and comprehensive information, the resultant ICC was in the excellent range, at .87 (95% CI .71, .94), F(21,22) = 13.98, p < .001. For the 21 youth where both the therapist and the supervisor believed that they had below-average knowledge of the client (i.e. a score of ≤16), the ICC was in the good range, or .71 (95% CI .42, .87), F(20,21) = 5.95, p < .001. Based on calculations from Feldt et al. (Citation1987), interrater agreement with the PROFESOR was significantly higher when both raters believed that they had more complete information regarding the client, F(21,20) = 2.15, p = 0.05.

The second aim of this investigation was to examine additional measures of the reliability of the PROFESOR: namely item-total correlations and internal consistency. displays the item-total correlations based on the therapists’ ratings, and it can be seen that all 20 items on the PROFESOR significantly contributed to the Total score. The internal consistency estimate (α) for the PROFESOR was found to be .87 using therapist ratings (and .86 using supervisor ratings) indicating that there is a high degree of interrelatedness amongst the 20 items. also displays the distribution of Protective, Neutral, and Risk ratings made by therapists for the 58 youth in care.

Table 3. Item-Total Correlations and Distribution of Factors (based on therapist ratings).

Discussion

The PROFESOR was designed as an alternative risk (and protective factors) assessment tool for adolescents and emerging adults (i.e. individuals aged 12–25) who have engaged in (or have been accused of engaging in) sexually harming behaviour, with the aim of identifying dynamic risk and protective factors that could inform intervention rather than predicting the future. The 20 factors on the PROFESOR have both a protective and a risk pole (and a rating of Neutral when a rating of either Risk or Protective would not apply), and they are coded based on the individual’s functioning throughout the most recent two month period. In this preliminary investigation of the reliability of the PROFESOR, the results indicate that excellent interrater agreement can be achieved. Importantly, this was demonstrated when raters based their judgments on their working knowledge of the individuals in their care rather than through the more typical process where ratings are completed by two or more individuals reading the identical file material. Furthermore, it was demonstrated that this level of interrater agreement can be achieved with a modest degree of training regarding the coding rules for the PROFESOR.

The results also show, not surprisingly, that the level of agreement between raters is significantly higher when both raters believe that they have more complete and comprehensive information about the individual being rated (although interrater agreement was still good when this was not the case). Current best-practice guidelines regarding interventions with adolescents who have sexually offended recommend that, not only should assessors consider both risk and protective factors, but that interventions be based on a comprehensive assessment of the individual (ATSA, Citation2017). In future studies, it would be instructive to determine how differential reliance on information from various sources (e.g. client interview, parent/caregiver interview, formal testing, therapist case notes) impacts the reliability of PROFESOR ratings. Also, most individuals who provided ratings for this investigation had at least 3 years of experience providing specialised clinical services to adolescents who have engaged in sexually abusive behaviour, so it will be important to determine whether similarly high levels of interrater agreement can be achieved with clinicians with less experience.

Two additional aspects of reliability were examined in this investigation. First, item-total correlations indicate that each of the 20 factors on the PROFESOR contributes significantly to the Total score. This level of analysis is not commonly reported in research with risk assessment tools, as researchers most typically report data regarding total scores only; potentially obfuscating items that contribute little to the overall score. Second, the internal consistency estimate (α) was high, indicating that there is a high degree of interrelatedness amongst the items. Research with larger samples may further reveal that there are underlying factors on the PROFESOR. For example, it may be that those items more specifically related to an individual’s current sexual functioning (i.e. items 1 through 8) comprise one factor whereas items related to more general functioning (i.e. items 9 through 20) make up a second factor. Alternatively, it could be that those items that are focused more on individual functioning (e.g. self-esteem, knowledge of impact of sexually abusive behaviour, sexual interests) are differentiated statistically from items that reflect more relational (e.g. interpersonal intimacy, compassion, relationship with parent/caregiver) and environmental functioning (i.e. sexual environment, current living arrangement). The identification of such factors could further inform intervention decisions. For example, treatment recommendations could look quite different for those youth with a high number of risk factors clustered in the sexual functioning factor vs. the more general functioning factor. Of course, treatment goals within the sexual-functioning domain should still be tailored to meet the individual’s needs, and the results from the PROFESOR can assist in this regard. For example, one individual may need to address their sexual interest in prepubescent children, their poor understanding of the impact of sexually abusive behaviour, and their lack of strategies for developing healthy sexual relationships, whereas another individual may need interventions to focus on their abuse-supportive sexual attitudes, their sexual preoccupation, and their lack of strategies to prevent sexually abusive behaviour.

As all items on the PROFESOR are dynamic, the tool can also be used to track intervention progress. For example, PROFESOR ratings completed midway through the treatment process could highlight which factors have shown improvement over time (i.e. moved from Risk to Neutral or Protective or from Neutral to Protective). PROFESOR ratings completed at the termination of the intervention process could also highlight any outstanding goals (i.e. those factors rated as either Neutral or Risk). As noted earlier, it would also be helpful at the conclusion of treatment to recommend steps for ensuring that factors rated as Protective remain so in the future. For example, a young adolescent may now be demonstrating a high level of commitment to and engagement in school (item # 18), and it would be ideal to provide some guidance on how best to maintain this treatment gain moving forward (e.g. through suggestions for specific instructional approaches and/or curriculum content).

It will also be essential for researchers to collect data regarding the validity of the PROFESOR. With respect to construct validity, for example, it will be important to demonstrate that items on the PROFESOR are measuring what they are intended to measure. Estimates of concurrent validity utilising tools that are designed to assess similar factors will be particularly informative in this respect. For example, one could compare ratings from the PROFESOR to ratings from the Child and Adolescent Needs and Strengths (CANS; Lyons, Citation2009), as there are a number of overlapping factors on the two tools, and both tools are designed to measure both positive and negative characteristics.

Given that a central goal of the PROFESOR is to inform intervention targets that will eliminate sexual recidivism, another area of research will be to investigate how risk and protective factors are related to future behaviour. Although the PROFESOR is not intended to forecast the future, it should still function such that a preponderance of risk factors is correlated with sexual recidivism and other negative outcomes, such as additional out-of-home placements, for example. Similarly, a large number of protective factors should be correlated with desistance from sexually harming behaviours and other positive outcomes, such as the establishment of healthy sexual relationships.

With respect to validity, one would also expect that the eight PROFESOR items focused specifically on an individual’s current sexual functioning would be more closely related to future sexual behaviour whereas the remaining twelve items that reflect more general functioning would be more closely related to variables reflecting future nonsexual functioning. In light of recent findings demonstrating that items labelled by test developers as “risk” or “protective” do not necessarily function as intended and, furthermore, that an item’s valence can change based on characteristics such as the dependent measure in question (e.g. general recidivism vs. violent recidivism) (Langton et al., Citation2024, Citation2023), it will be essential to determine whether the 20 bipolar factors on the PROFESOR function as designed. For example, it may be found that, although a rating of Risk on item #11, reflecting poor self-regulation, is significantly related to negative outcomes, a rating of Protective on the same item may not be related to positive outcomes. As such, this could render that item as a “risk-only” item with no corresponding protective pole. Alternatively, it may be that variability in self-regulation is more significantly related to future criminal charges but not to other dependent measures, such as number of subsequent out-of-home placements, for example. Additional studies of this nature with the PROFESOR (and, importantly, with established tools designed to assess risk and/or protective factors) are needed to better understand the operationalisation of purported risk and protective factors.

There are some limitations to the generalisability of the results from this study. First, the number of individuals rated by therapists and their supervisors was relatively small. Second, the individuals who were rated on the PROFESOR were all in a residential treatment programme designed for male youth, and most had offended against a younger child and against a family member. Furthermore, most of the individuals who were rated for this study had been in previous out-of-home settings, which is likely indicative of more significant treatment needs relative to other individuals who have engaged in sexually harming behaviour who may be residing in the community. It will be important to continue to investigate the reliability of the PROFESOR with different groups, including females who have engaged in harming sexual behaviour and adolescents and emerging adults who are not in residential settings, for example.

This is the first investigation of the psychometric properties of the PROFESOR. The results are encouraging, as they suggest that the PROFESOR yields reliable information regarding risk and protective factors related to future sexual and relationship health for individuals who have engaged in sexually abusive behaviour. Research is certainly required regarding the validity of the PROFESOR. At this juncture, however, the tool can aid in the identification and measurement of specific intervention goals.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ahrens, C. E., Stansell, J., & Jennings, A. (2010). To tell or not to tell: The impact of disclosure on sexual assault survivors’ recovery. Violence and Victims, 25(5), 631–648. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.25.5.631

- Andrews, D. A., Bonta, J., & Hoge, R. D. (1990). Classification for effective rehabilitation: Rediscovering psychology. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 17(1), 19–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854890017001004

- Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469

- Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers (ATSA). (2017). Practice guidelines for assessment, treatment, and intervention with adolescents who have engaged in sexually abusive behavior. Author.

- Baker, A. J. L., Tabacoff, R., Tornusciolo, G., & Eisenstadt, M. (2001). Calculating number of offenses and victims of juvenile sexual offending: The role of posttreatment disclosures. Sexual Abuse, 13(2), 79–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/107906320101300202

- Barraclough, P., af Wåhlberg, A., Freeman, J., Watson, B., & Watson, A. (2016). Predicting crashes using traffic offences. A meta-analysis that examines potential bias between self-report and archival data. PLoS One, 11(4), e0153390. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153390

- Beech, A. R., & Ward, T. (2004). The integration of etiology and risk in sexual offenders: A theoretical framework. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 10(1), 31–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2003.08.002

- Blasko, B. L., Jeglic, E. L., & Mercado, C. C. (2011). Are actuarial risk data used to make determinations of sex offender risk classification?: An examination of sex offenders selected for enhanced registration and notification. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 55(5), 676–692. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X10372784

- Caldwell, M. F. (2016). Quantifying the decline in juvenile sexual recidivism rates. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 22(4), 414. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000094

- Carpentier, J., Leclerc, B., & Proulx, J. (2011). Juvenile sexual offenders: Correlates of onset, variety, and desistance of criminal behavior. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 38(8), 854–873. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854811407730

- Carter, G., Milner, A., McGill, K., Pirkis, J., Kapur, N., & Spittal, M. J. (2017). Predicting suicidal behaviours using clinical instruments: Systematic review and meta-analysis of positive predictive values for risk scales. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 210(6), 387–395. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.116.182717

- Cicchetti, D. V. (1994). Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment, 6(4), 284–290. http://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.6.4.284

- Craig, L. A., & Rettenberger, M. (2016). A brief history of sexual offender risk assessment. In D. Laws & W. O'Donohue (Eds.), Treatment of sex offenders (pp. 19–44). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-25868-3_2.

- de Vries Robbé, M., Mann, R. E., Maruna, S., & Thornton, D. (2015). An exploration of protective factors supporting desistance from sexual offending. Sexual Abuse, 27(1), 16–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063214547582

- Fazel, S., Singh, J. P., Doll, H., & Grann, M. (2012). Use of risk assessment instruments to predict violence and antisocial behaviour in 73 samples involving 24,827 people: Systematic review and meta-analysis. British Medical Journal, 345(jul24 2), e4692. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e4692

- Feldt, L. S., Woodruff, D. J., & Salih, F. A. (1987). Statistical inference for coefficient alpha. Applied Psychological Measurement, 11(1), 93–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662168701100107

- Fish, J. N., Baams, L., Wojciak, A. S., & Russell, S. T. (2019). Are sexual minority youth overrepresented in foster care, child welfare, and out-of-home placement? Findings from nationally representative data. Child Abuse & Neglect, 89, 203–211. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.01.005

- Griffin, H. L., Beech, A., Print, B., Bradshaw, H., & Quayle, J. (2008). The development and initial testing of the AIM2 framework to assess risk and strengths in young people who sexually offend. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 14(3), 211–225. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13552600802366593

- Hanson, R. K., & Bussière, M. T. (1998). Predicting relapse: A meta-analysis of sexual offender recidivism studies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66(2), 348–362. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.66.2.348

- Hanson, R. K., & Morton-Bourgon, K. E. (2009). The accuracy of recidivism risk assessments for sexual offenders: A meta-analysis of 118 prediction studies. Psychological Assessment, 21(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014421

- Harris, A. J., Walfield, S. M., Shields, R. T., & Letourneau, E. J. (2016). Collateral consequences of juvenile sex offender registration and notification: Results from a survey of treatment providers. Sexual Abuse, 28(8), 770–790. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063215574004

- Helmus, L., Thornton, D., Hanson, R. K., & Babchishin, K. M. (2012). Improving the predictive accuracy of Static-99 and Static-2002 with older sex offenders: Revised age weights. Sexual Abuse, 24(1), 64–101. http://doi.org/10.1177/1079063211409951

- Helmus, L. M., Kelley, S. M., Frazier, A., Fernandez, Y. M., Lee, S. C., Rettenberger, M., & Boccaccini, M. T. (2022). Static-99R: Strengths, limitations, predictive accuracy meta-analysis, and legal admissibility review. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 28(3), 307–331. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000351

- Hoge, R. D., & Andrews, D. A. (2011). Youth level of service/case management inventory 2.0. Multihealth Systems.

- Jadhav, R., Achutan, C., Haynatzki, G., Rajaram, S., & Rautiainen, R. (2015). Risk factors for agricultural injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Agromedicine, 20(4), 434–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/1059924X.2015.1075450

- Jensen, M., Askeland, I. R., & Bjørknes, R. (2022). Interrater reliability and experiences of assessment, intervention, and moving-on 3 assessment model in a multidisciplinary Norwegian sample. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1019739. http://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1019739

- Kansagara, D., Englander, H., Salanitro, A., Kagen, D., Theobald, C., Freeman, M., & Kripalani, S. (2011). Risk prediction models for hospital readmission: A systematic review. JAMA, 306(15), 1688–1698. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1515

- Kim, K., Duwe, G., Tiry, E., Oglesby-Neal, A., Hu, C., Shields, R., Letourneau, E., & Caldwell, M. (2019). Development and validation of an actuarial risk assessment tool for juveniles with a history of sexual offending. National Criminal Justice Reference Service, Office of Justice Programs. https://www.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh241/files/media/document/253444.pdf.

- King, C. K., & Rings, J. A. (2022). Adolescent sexting: Ethical and legal implications for psychologists. Ethics & Behavior, 32(6), 469–479. http://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2021.1983818

- Krause, C., Roth, A., Landolt, M. A., Bessler, C., & Aebi, M. (2021). Validity of risk assessment instruments among juveniles who sexually offended: Victim age matters. Sexual Abuse, 33(4), 379–405. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1079063220910719

- Langton, C. M., Awrey, M. J., & Worling, J. R. (2023). Protective factors in the prediction of criminal outcomes for youth with sexual offenses using tools developed for adults and adolescents: Tests of direct effects and moderation of risk. Psychological Assessment, 35 (6), 497–509. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0001227

- Langton, C. M., Betteridge, M., & Worling, J. R. (2024). Promotive, mixed, and risk effects of individual items comprising the SAPROF assessment tool with justice-involved youth. Assessment, 31(2), 418–430. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/10731911231163617

- Langton, C. M., Ranjit, J. A., & Worling, J. R. (2023). A proof of concept study of promotive, mixed, and risk effects using the SAVRY assessment tool items with youth with sexual offenses. Psychological Assessment, 35(10), 856–867. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0001272

- Langton, C. M., & Worling, J. R. (2015). Introduction to the special issue on factors positively associated with desistance for adolescents and adults who have sexually offended. Sexual Abuse, 27(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063214568423

- Leonard, M., & Hackett, S. (2019). The AIM3 assessment model: Assessment of adolescents and harmful sexual behaviour. AIM Project.

- Lyons, J. S. (2009). Communimetrics: A theory of measurement for human service enterprises. Springer.

- Mann, R. E., Hanson, R. K., & Thornton, D. (2010). Assessing risk for sexual recidivism: Some proposals on the nature of psychologically meaningful risk factors. Sexual Abuse, 22(2), 191–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063210366039

- McCann, K., & Lussier, P. (2008). Antisociality, sexual deviance, and sexual reoffending in juvenile sex offenders: A meta-analytical investigation. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 6(4), 363–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541204008320260

- McGrath, R. J., Cumming, G. F., Burchard, B. L., Zeoli, S., & Ellerby, L. (2010). Current practices and emerging trends in sexual abuser management: The Safer Society 2009 North American Survey. Safer Society Press.

- McGraw, K. O., & Wong, S. P. (1996). Forming inferences about some intraclass correlation coefficients. Psychological Methods, 1(1), 30–46. http://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.1.1.30

- Olver, M. E., Stockdale, K. C., & Wormith, J. S. (2009). Risk assessment with young offenders: A meta-analysis of three assessment measures. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 36(4), 329–353. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854809331457

- Phenix, A., Fernandez, Y., Harris, A. J. R., Helmus, M., Hanson, R. K., & Thornton, D. (2016). Static-99R Coding Rules Revised-2016. static99.org.

- Prentky, R., & Righthand, S. (2003). Juvenile Sex Offender Assessment Protocol—II (J-SOAP-II): Manual. Unpublished document.

- Prentky, R. A., & Righthand, S.. (2021). The juvenile sex offender assessment protocol-II (JSOAP-II). In K. S. Douglas & R. K. Otto (Eds.), Handbook of violence risk assessment (2nd. ed., pp. 294–321). Routledge/Taylor Francis.

- Print, B., Morrison, T., & Henniker, J. (2001). An inter-agency assessment framework for young people who sexually abuse: Principles, processes and practicalities. In M. C. Calder (Ed.), Juveniles and children who sexually abuse: Frameworks for assessment (pp. 271–281). Russell House.

- Rasmussen, L. (2018). Comparing predictive validity of JSORRAT-II and MEGA♪ with sexually abusive youth in long-term residential custody. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 62(10), 2937–2953. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X17726550

- Rich, A., Brandes, K., Mullan, B., & Hagger, M. S. (2015). Theory of planned behavior and adherence in chronic illness: A meta-analysis. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 38(4), 673–688. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-015-9644-3

- Rojas, E. Y., & Olver, M. E. (2019). Validity and reliability of the violence risk scale–youth sexual offense version. Sexual Abuse, 32(7), 826–849. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063219858064

- Schwalbe, C. S. (2007). Risk assessment for juvenile justice: A meta-analysis. Law and Human Behavior, 31(5), 449–462. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10979-006-9071-7

- Thornton, D. (2013). Implications of our developing understanding of risk and protective factors in the treatment of adult male sexual offenders. International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy, 8(3–4), 62–65. http://doi.org/10.1037/h0100985

- van den Berg, J. W., Smid, W., Schepers, K., Wever, E., van Beek, D., Janssen, E., & Gijs, L. (2018). The predictive properties of dynamic sex offender risk assessment instruments: A meta-analysis. Psychological Assessment, 30(2), 179–191. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000454

- van der Put, C. E., & Asscher, J. J. (2015). Protective factors in male adolescents with a history of sexual and/or violent offending: A comparison between three subgroups. Sexual Abuse, 27(1), 109–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063214549259

- van der Put, C. E., Assink, M., & Boekhout van Solinge, N. F. (2017). Predicting child maltreatment: A meta-analysis of the predictive validity of risk assessment instruments. Child Abuse & Neglect, 73, 71–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.09.016

- van der Put, C. E., Gubbels, J., & Assink, M. (2019). Predicting domestic violence: A meta-analysis on the predictive validity of risk assessment tools. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 47, 100–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2019.03.008

- Viljoen, J. L., Mordell, S., & Beneteau, J. L. (2012). Prediction of adolescent sexual reoffending: A meta-analysis of the J-SOAP-II, ERASOR, J-SORRAT-II, and Static-99. Law and Human Behavior, 36(5), 423–438. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0093938

- Vivar, L. A., Muñoz, M. S., Cárcamo, Y. B., & Arenas, R. P.-L. (2021). Factores protectores en adolescentes que han desarrollado conductas sexuales abusivas: Propiedades psicométricas del DASH-13 en Chile [Protective factors in adolescents who have engaged in abusive sexual behaviors: Psychometric properties of DASH-13 in Chile]. Revista Señales, 04, 60–75. https://www.sename.cl/web/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/A4-Revista_Se%C3%B1ales_web_n%C2%BA25_25_01.pdf.

- Williams, D. J., Thomas, J. N., & Prior, E. E. (2015). Moving full-speed ahead in the wrong direction? A critical examination of US sex-offender policy from a positive sexuality model. Critical Criminology, 23(3), 277–294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10612-015-9270-y

- Worling, J. R. (2013). Desistance for Adolescents who Sexual Harm (DASH-13). Unpublished document. www.drjamesworling.com.

- Worling, J. R. (2017). Protective + Risk Observations For Eliminating Sexual Offense Recidivism (PROFESOR). Unpublished document. www.profesor.ca.

- Worling, J. R., & Curwen, T. (2001). Estimate of Risk of Adolescent Sexual Offense Recidivism (ERASOR; Version 2.0). In M. C. Calder (Ed.), Juveniles and children who sexually abuse: Frameworks for assessment (pp. 372–397). Russell House.

- Worling, J. R., & Långström, N. (2003). Assessment of criminal recidivism risk with adolescents who have offended sexually: A review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 4(4), 341–362. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838003256562

- Worling, J. R., & Langton, C. M. (2022). Factors related to desistance from sexual recidivism. In C. M. Langton & J. R. Worling (Eds.), Facilitating desistance from aggression and crime: Theory, research, and strength-based practices (pp. 211–229). John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119166504.ch8.

- Zeng, G., Chu, C. M., & Lee, Y. (2015). Assessing protective factors of youth who sexually offended in Singapore: Preliminary evidence on the utility of the DASH-13 and the SAPROF. Sexual Abuse, 27(1), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063214561684