ABSTRACT

Theories of populism have been troubled by the problem of essentially contested definitions of its basic properties. It is difficult to distinguish populism from conventional political behavior. This produces the problem of ‘degreeism’, while other features of populism are expressed in relationships rather than as specific categories of attitudes and behaviors. These problems cannot be eliminated by redefining or excluding aspects of populism in favor of a more restrictive definition. We argue that, given that conceptual indeterminacy is inherent in populism, it is better conceptualized as a relational concept. The article articulates a new, relational conception of populist ideology, discourse/rhetoric, and leadership style in terms of relative distance from an implicit ‘center ground’. Populism is marked by position-taking of distance away from the center in policy (distal), a wide distance between people and elites and/or outsiders (distal), and close distance between leaders and followers (proximal). A general, relational model of populism is deduced in this form: distal – distal – proximal. Far from being an abstract claim, we illustrate how the relative distance framework offers descriptive and analytical tools for social scientists focused on populism.

1. Introduction

Political scientists have been unable to agree upon a definition of populism. As with other territory in political science, conceptual disputes are common in populism research. Such disputes add vitality to a subject area as well as playing a central role in generating new research agendas. While a consensus has developed around the notion that populism is characterized by respect for popular sovereignty and based on opposition between ‘the people’ and an elite, its genus remains in dispute.Footnote1 Broadly, scholars have defined populism as an ideology, a leadership style, or a political discourse.Footnote2 For Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, these differences are ‘minor, and irrelevant to many research questions’.Footnote3 Indeed, the three conceptions can be brought together as ‘the ideational approach’. However, this simplification comes at the cost of nuance. These different ideational perspectives can in fact be situated within a common framework, via a meta-theoretical analysis. Our aim here is not to fully reconcile different theories, but to respond to criticisms of them and strengthen engagement between them. In turn, we argue that the relational framework constitutes a new perspective on populism, contributing to future research.

The difficulty of identifying precise dimensions to populism stems from efforts to ontologically objectify it as possessing unique properties. In other words, it is an essentially contested concept.Footnote4 Definitions focused on a single property of populist politics – for instance, those that limit populism to populist leadership styles – are too restrictive. Moreover, they are unable to exclude rival interpretations based on other concepts, such as ideology. Conversely, less restrictive definitions become too broad to delineate populism from other political behavior.Footnote5 Moreover, aspects of even restrictive definitions might apply to instances of political action not conventionally termed populist, such as the immigration policies of mainstream parties. One such conceptual problem is found in the difficulty of delineating populists and their actions from those of conventional politicians. This has been formulated in critical accounts of the ‘degreeism’ problem inherent in some theories, including accounts of populism.Footnote6 Progress has already been made in dealing with the fuzziness of populism by introducing a relational dimension to definitions. Relationalism is a different underpinning logic of inquiry which inherently resists the problem of degreeism by articulating relations and inter-relations as overlapping elements of social action. This is conceptually different from categorical approaches which ontologically separate actors and actions.

At root, then, is that both narrow and less restrictive definitions fail to recognize that populism shares similar territory and elements with conventional politics. Relationalism has been introduced to populism theory already in response to this conceptual difficulty, with Ostiguy presenting populism as an ‘ordinal category’Footnote7 and Ostiguy and Moffitt elevating the relational to a central conceptual role.Footnote8 Weyland also acknowledges relational variance in the ‘closeness’ of populists to followers but prefers handling conceptual vagueness by advocating ‘fuzzy set’ methods.Footnote9 This article addresses the problem of conceptual delineation in populism by following such an approach: we reframe existing theories within a relational framework based in rhetoric and argumentation theory. This approach allows us to take one further step. By making sense of degreeism within a relational framework, we identify those common properties in existing ideational theories of populism that help forge new avenues for populism research. We conclude that the relational dimension is so central to contrasting theories that it should be understood as a defining feature of populism itself. Far from an exclusively technical claim, we illustrate how a focus on ‘relative distance’ encourages new methods and lines of social inquiry into populist politics. To overcome the obstacle to theory development, and so break impasses in the literature, we propose a three-dimensional model which conceives of populism as a relational concept by introducing a relational element to the three ideational approaches described above. Thus, it builds on other trends in the literature but is unique in generalizing the relational dynamicFootnote10 across all the elements of populist theory, situated within a framework that declines the post-structuralist approach in favor of an interpretivist one compatible with critical realism.

Section One discusses the populism literature, investigating theoretical conflicts and highlighting relational patterns inherent in existing analyses. Section Two develops our framework grounded in the philosophical perspectives provided by the philosophy of questioning and rhetoric. After categorizing the three dimensions of populism, it explains their relational transformation and presents them in three figures that express their relational distance from non-populism. Section Three discusses the implications of the framework as a promising basis for future social research.

2. Theories of populism

Although populism is regarded as a contested concept, the prevailing view among scholars is that it is a form of ideology.Footnote11 The leading proponent of this position is Cas Mudde who defines populism as:

An ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite’, and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people. [original emphasis]Footnote12

Drawing on Freeden,Footnote13 Mudde describes populism as a ‘thin-centered’ ideology.Footnote14 Accordingly, it contains few core concepts, acquiring substance when combined with other ideologies like socialism or nationalism. For Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, the conceptual core of populism comprises ‘the pure people’, ‘the corrupt elite’, and the general will.Footnote15 There is a moral distinction between ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’, with the former designated as virtuous, and the latter, pathological. Meanwhile, the general will assumes that popular sovereignty is ‘the only legitimate source of political power’. Taken together, Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser argue, these three concepts are the necessary and sufficient conditions for phenomena to be ‘populist’.Footnote16

Once again following Freeden, Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser recognize that political concepts acquire meaning from their contexts.Footnote17 Consequently, ‘the people’ can be defined in a variety of ways (‘the silent majority’ or ‘the American people’), while ‘the elite’ can be cast as ‘unelected Eurocrats’ or inhabitants of the ‘Westminster bubble’. The ideational view presents populism as ‘a rhetorical style or political frame’ that expresses this broad conflict, present to varying degrees and changing over time.Footnote18 The contestability of the nature of conflicts between people and elites, the variety of political rhetoric employed along with the ideological ‘thinness’ of the concepts, has led scholars to describe populism as ‘chameleonic’.Footnote19 Indeed, as Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser observe, populism may be ‘left-wing or right-wing, organized in top-down or bottom-up fashion, rely on strong leaders or be even leaderless’.Footnote20 This point highlights two strengths of the ideological definition. The first strength is that populism is not the sole preserve of the political right and can take different forms. The populism-as-ideology perspective has been adapted in research that reveals the importance of ‘centrist’ populism, for instance in Central and Eastern Europe,Footnote21 while other European scholarship has had to weaken assumptions about the positional extremism of populist parties on the left-right ideological scale.Footnote22 The second strength is that populism-as-ideology acknowledges the importance of context, grounding populist phenomena in the ‘real world’, in which rhetoric is used to frame political issues and direct blame onto the actions of elites, argued to be acting intentionally.Footnote23 We now consider the methodological implications of applying this definition.

The study of populism qua ideology sometimes involves a quantitative analysis of speeches and texts, in which references to ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’ are counted and coded (Aslanidis 2016, 93). This is because scholars regard the shift to the discursive realm as the only means of operationalizing ideology ‘without having to add another theoretical element to the definition’.Footnote24 The textual approach leads to ‘degreeism’ which, for Dean and Maiguashca, poses a serious challenge to the ideology definition. They argue that the problem of ‘degrees’ raises the irresolvable question of where and how to draw the boundary between merely populist language and full-blown populist politics.Footnote25 Other ideational scholars do not see degreeism as a problem. Indeed, they conclude that, given the interpretative scope surrounding the use of rhetoric, ’Populism in the ideational sense is better conceived as a continuous variable’,Footnote26 even while many authors do, in practice, use concrete terms in specifically referring to populist parties and politicians. We support the graduated conception of populism, but for degreeism to be dealt with effectively, a relational account is required to express this continuity.

Given the thinness of ideology in populist politics, a skeptical view contests the utility of the ideological definition, and of populism along with it.Footnote27 One empirical study by Bonikowski and Gidron similarly rejected the idea of populism as an ideology in favor of a relational definition, pointing toward its strategic use.Footnote28 They find that populism is a property of strategic claims by outsider US presidential candidates, one which is proportional to their distance from the center of power. Against the ideological view, Aslanidis concludes that, despite the ‘convincing body of research that illustrates the merits of investigating gradations’,Footnote29 the populism-as-ideology school precludes degreeism because it is fundamentally essentialist. He explains that, in the same way as adherence to an ideology is of a ‘take it or leave it’ nature, a ‘political party or leader can or cannot be populist; there is no grey zone’.Footnote30 Thus, the ideology perspective cannot explain the use of populist language by politicians who are not otherwise categorized as such. This debate perhaps stems from a disagreement over whether the core concepts of populism are dichotomous or continuous. Either way, the empirical evidence from Bonikowksi and Gidron,Footnote31 and populism’s contextual contingency, lend weight to Aslanidis’s claim that ‘since the necessary dimensions of [a] concept can exhibit variation, surely the concept itself can vary accordingly’.Footnote32

Turning to the leadership definition, Weyland defines populism as ‘a political strategy through which a personalistic leader seeks or exercises government power based on direct, unmediated, uninstitutionalized support from large numbers of mostly unorganized followers’.Footnote33 Such a leader will offer themselves as the representative – or even savior – of ‘the people’ to whom they appeal in a struggle against ‘the corrupt elite’. The leader will seek to bypass party politics and complex organizations, communicating directly with supporters through social media or a personal blog.Footnote34 The populism-as-leadership definition draws on the notion of charisma which, as van der Brug and Mughan point out, is not ‘an attribute of leaders themselves, but is a quality that inheres in the relationship between a leader and his followers’.Footnote35 In short, the populist leader builds a following through promises of redemption and maintains it by inspiring faith among the support base.Footnote36 Thus, ‘the follower “gives way” to the charisma of the prophet, the warrior, the demagogue, on account of their personal, exceptional merits’.Footnote37

The leadership perspective on populism raises several methodological questions, including: How is charisma defined? Can it be measured? And, if charisma is quantifiable, how can it be isolated from other factors contributing to the success of populist leaders? And the degreeism problem arises once more, given that conventional politicians also, often, exhibit charismatic authority. To complicate matters, write van der Brug and Mughan, ‘charisma is often attributed to populist party leaders after the fact, i.e. after their parties have registered electoral success in the polls’.Footnote38 Indeed, they continue, even if a populist leader is found to benefit a party’s electoral performance, this cannot definitively be attributed to any charismatic relationship.Footnote39 The problem here is that voters may support a politician for a variety of reasons,Footnote40 such as their ability to mobilize their activist base,Footnote41 their policy proposals, or disillusionment with mainstream parties that stimulates a concomitant desire for change. In short, ‘charismatic personalities [may] have a natural advantage in generating support, but it is not a defining characteristic.Footnote42

A solution presents itself in the form of a relational conception of leadership as performance. Moffitt and Tormey argue that populism is a political style that employs various types of performance to generate particular dynamics with an audience, constructing its subjectivity in a feedback loop which in turn enhances the performance.Footnote43 Populist style has been classified along a high-low axis.Footnote44 Hence, populism is a style unconfined to any position along the left-right axis, is available as a tool for use by mainstream politicians not otherwise considered populist, is able to show that ‘the people’ need not preexist but can be constituted actively by a populist leader, and is distinguishable from other political styles.Footnote45 The relational and performative dimension of the theory is central: leaders’ styles are tailored to their target audiences’ expectations, which media technologies make even more targeted and persuasive.

Others argue that charisma, or style, is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for a leader to be classed as ‘populist’. As Mudde explains, unmediated communication with ‘the people’ and charismatic leadership merely facilitate populism, and so is best understood as a ‘special type of organization’.Footnote46 After all, a populist figure may not form a charismatic relationship with followers and may even lead an established political party.Footnote47 Equally, the language of mainstream politicians might be highly demotic but, in the absence of anti-elitism, it cannot be classed as ‘populist’.Footnote48 One further difficulty is that, by conceiving of populism as strategy, the ‘style’ definition places undue emphasis on leaders. That overlooks the contribution of a ‘populist ideology that is flexible enough to include the perceptions and needs of different constituencies’.Footnote49 Post-Laclauian theory has adapted to the problem of a fixed identity of the leader by acknowledging that multiple interpretations of leaders can co-exist.Footnote50 However, such an adaptation raises the possibility of utilizing a more conventional interpretive epistemology to handle the empirical analysis of populist discourse and its performance. The post-Laclauian branch of scholarship has also introduced the notion of populist ‘appeals’ to ‘woo’ supporters,Footnote51 including the performance of rhetoric in a ‘low’ register, which we argue is another name for rhetoric in the service of persuasion. Combined, an interpretive – relational framework seems appropriate to factor in these concepts while retaining insights from ideational theory.

The importance of creating broad support and offering an ideologically-informed vision suggest that the leadership perspective alone cannot account for populist phenomena. Yet it is evident from the work of Moffitt and Tormey that populism is found in particular performative styles of leadership, which are relational in regard to a core audience.Footnote52 Hence, there can be gradations of populism employed by different types of political leaders. Degreeism appears once again in demarcating populist from conventional performance. But Moffitt and Tormey limit rhetoric to a phenomenon of populist communications that does not incorporate a performative element,Footnote53 although subsequent innovations give performativity a leading role.Footnote54 However, we diverge from these authors about the place of rhetoric. We support the claim about performativity, but instead of the limited place for relationalism in post-Laclauian theory, we argue not only that a performative and relational theory of rhetoric is already available but that it suffices for theory development because: 1) it equally articulates the relational element of leadership style and thus handles the degreeism question; and 2) it additionally supports a synthesis on relational grounds with the other ideational elements of populism.

This brings us to a more specific reflection on the theory of populism from Laclau and the ‘Essex School’ of discourse theory.Footnote55 For Laclau, ‘populism starts at the point where popular democratic elements are presented as an antagonistic option against the ideology of the dominant bloc’Footnote56; in other words, it is a counter-hegemonic formation in which ‘the people’ are united in opposition to ‘the corrupt elite’.Footnote57 Here, ‘the people’ is a privileged – or ‘empty’ – signifier that represents diverse interests, demands, and identities brought together in an ‘equivalential chain’Footnote58 by their hostility to a common ‘other’, which itself is constructed through the logic of equivalence. Illustrating this point, the UK anti-austerity movement created chains of equivalence among the demands of such disparate groups as public sector workers, students, and benefits claimants, highlighting their antipathy to shared enemies that are government, banks, and big business.Footnote59 The social realm was thus divided into two camps, with ‘the one percent’ (‘the corrupt elite’) positioned against ‘the 99%’ (‘the people’).

Laclau’s theory also permits degrees of populism, dependent on ‘the depth of the chasm separating political alternatives’.Footnote60 However, Aslanidis observes that this account poses methodological difficulties, failing to provide ‘concrete means of operationalizing indicators to reveal variation in some detail’.Footnote61 Consequently, it precludes the quantitative textual analyses associated with the populism-as-ideology school, and instead relies on subjective interpretation. Dean and Maiguashca highlight a similar issue, namely that Laclau’s definition of populism as a counter-hegemonic formation implies that ‘all oppositional or radical politics must be conceived as populist in nature’.Footnote62 This is clearly not the case, so the challenge for Laclau’s followers is to handle the degreeism problem, specifying where to draw the line between populism and other forms of resistance to the dominant bloc. Otherwise, Dean and Maiguashca continue, ‘populism loses any specificity of its own and becomes just another way of characterizing radical politics of all persuasions’.Footnote63

Post-structuralist analysis has adapted to these criticisms. The postmodern aspects have been softened in favor of a ‘post-Laclauian’ approach, eschewing the previous rejection of sociological theory via a type of realist adaptation (without going so far as accepting critical realism), for instance in accepting material bases to social cleavages.Footnote64 And as noted above, an additional element is the introduction of a relational and performative account of public appeals, insofar as the pragmatic level of discursive interaction is recognized, against the formal abstractions of the ‘empty signifier.Footnote65 We support this move, but argue that our approach makes further advances on their relational account because: 1) it requires no post-structuralist assumptions and utilizes a more parsimonious terminology; 2) it is compatible with critical realism in allowing for materially-generated social distinctions, is operationalizable in quantitative or qualitative methods via the parameter of distance, while also centering performativity via rhetoric and acts of social positioning; and 3) it entrenches the relational element across all three ideational perspectives, while at the same time handling the degreeism problem by making relational distance fundamental to the concept. Thus, it offers an encompassing relational conception of populism from which to build political and sociological analyses.

Drawing together these critical reflections, we identify why (and how) relational themes should be incorporated into theory. This schema is based on the insight that populism is relationally – but not ontologically – distinctive, evident in several facets, namely: 1) a clear distinction between populism and conventional politics is difficult to sustain (the degreeism problem); 2) the need for nuanced, continuous variables rather than essentialist distinctions, particularly when it comes to the subtleties of political language; 3) the relational quality of charismatic leadership, which lies between a populist leader and ‘the people’; and 4) the distinction between ‘the elite’ and ‘the people’ where, in a process of identity formation closely related to Abdelal et al.’s concept of ‘relational comparisons’, admittance to – and membership of – the group is conditional on the possession of predetermined qualities.Footnote66 These factors lead to conceptual instability, as Aslanidis has noted. But rather than pursuing the ontological coherence of populism as a concept by endeavoring to restrict the definition in some way, we argue that theoretically unexplicated relational dimensions are the source of instability such that, if rationalized in a relational framework across the three ideational elements of populism, they can be stabilized through coherent new parameters.

3. A relational meta-theoretical framework of populism

Existing scholarship identifies three key properties that constitute a theory of populism – ideology, leadership style, and discourse – without conclusively settling on one over the others. To relate these properties to a common denominator, we reframe each one in relational terms via two stages. First, we shift up one level of abstraction and utilize a framework of rhetoric and argumentation grounded in questioning, one that uses the concepts ethos, logos, and pathos. By situating these concepts at the meta-level, we locate the three properties of populism within a common framework.Footnote67 Second, we adopt a relational definition of argumentation as the performative negotiation of politics vis-à-vis an audience. This philosophy of rhetoric and argumentation has two main parts. The first reconceptualizes traditional Aristotelian modes of persuasion – ethos, logos, and pathos – by explaining how ideology, leadership style, and discourse/rhetoric, respectively, can be expressed through these categories. Consequently, it supports the application of these concepts as a heuristic framework, which can then be operationalized across a range of theories. The second part applies the relational dimension by conceptualizing the three modes of persuasion on equal terms in a performative-relational account of rhetoric in practice.Footnote68 Accordingly, we show how to reclaim each theory of populism in a relational mode.

3.1. A two-level framework to synthesize theories of populism

First, the three properties of populist theory can be represented as modes of the three analytical categories in a theory of rhetoric and argumentation. Common to most tripartite theoretical frameworks are underlying metaphysical questions of Self, World, and Other.Footnote69 These are usefully expressed through rhetoric and argumentation theory as ethos, logos and pathos. While Aristotle refers to these as the available means of persuasion, Meyer shows that they derive from the questions of Self, World and Other and thus encapsulate general properties; ethos refers to values and ideas, logos refers to discourse and material reality, while pathos refers to the emotions.Footnote70 We use them here in order to situate theories of populism within a common meta-theoretical framework at the categorical level – where the three concepts correspond to approaches to populism – and to maintain consistency when transposed into a relational logic of practice (see below). In the case of populism theories, ethos is expressed as ideology – the ideas and values that inform one’s political position and enable others to position themselves in relation to those values. This positioning is the dynamic territory of party politics. The question of logos concerns the world that is constructed through discourse in populist political communication, specifically utilizing rhetoric. Scholars have proposed that populists use distinct types of rhetoric/discourse and symbolic actions, primarily directed against elites or others outside the favored group. This includes constructed distinctions mapping on to material social inequality. Finally, the question of pathos pertains to emotions and identity, which for populism is emotional attachment to a leader generated by his/her leadership style (charismatic legitimacy, in Weber’s terms). Together, they constitute a tripartite heuristic.

At the second, performative level of political language, rhetoric and argumentation are relational phenomena: they address problems in situated contexts, between a speaker and the audience.Footnote71 Speech acts are performances that involve the expression of common values and preferences, but they also encompass strategic goals in the context of negotiating relationships – especially in political deliberation.Footnote72 For our purposes, the relational and contextual dimension is central: speech and dialogue are performed with the aim of maintaining or changing social distances. A performative definition of rhetoric and argumentation is couched in relational terms as the ‘negotiation of distance between individuals, the speaker (ethos) and the audience (pathos), on a given question (logos)’.Footnote73 While rhetoric has always concerned the relationship between speaker and audience, the introduction of distance as a continuum to characterize social position is new. AristotleFootnote74 had already written of distance in referring to the spatial and temporal basis of fear felt by an audience targeted for persuasion. Meyer’s contemporary theory generalizes distance to all communicative exchanges, integrating it into a discursive understanding of the construction and mobilization of social positions along a continuum. Thus, for theories of populism, it can serve as a basis to operationalize gradations, as suggested by Aslanidis (above). Moreover, the performative element is also important in understanding how populist discourse – including speech, gesture and other modes of style pertaining to cultural distinctions – creates meaning and reconstructs modes of political interaction. Research integrating discourse analysis with rhetoric emphasizes how discourse cogenerates self-legitimating scenes of interaction through the act of enunciation,Footnote75 such that the rhetorical speech act constructs a vision of the audience. Hence, rhetorical discourse generates the common identity of the audience and perceptions of its relative social position.

The two levels of analysis are interrelated. At the meta-level, ethos, logos and pathos correspond to modes of questioning. At the performative level of practice, in relational transformation, they indicate how populists and their audiences engage through the expression of values, choice of language and symbols, and leadership style to generate emotional reactions. Actors and audiences negotiate their distance from one another along a continuum from consensus to radical opposition, from affinitive identity in empathetic emotions to highly distanced resentment. This characterization is more in line with Mouffe’s essentially ‘agonistic’ – and sometimes antagonistic – public sphere shaped fundamentally by power relations,Footnote76 rather than one in which Habermasian rational consensus serves as the yardstick for public discourse. The object of inquiry here, however, is not rhetoric itself but theories of populism. At the performative level, theories of populism are arguments about what populism is, and each can be understood as proposing that populism is distanced from mainstream or conventional politics in terms of ideology, leadership style, or discourse. Thus, we should not think of a theory of populism as substantially distinctive in ontological terms—i.e. as a concrete form of political activity – but as relationally marking distance from conventional politics along three dimensions.

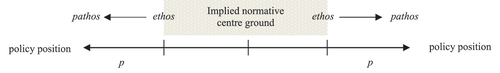

This relational account of populism aims at comprehensive reach: it renovates the basis of theory in general, identifies what is distinctive about theories of populism, and supports a synthesis of the three properties in relational terms, such that they can be considered together without exclusion or analytical priority. Concretely, a political actor or party might be positioned ideologically more or less to the left or right, employ rhetoric to increase or decrease their distance from elites and outsiders, and effect a political leadership style to create more or less proximity to their followers and against conventional politicians. The same actor may employ populist tactics on one dimension, but not others. sets out this synthesis.

Given its inherent degreeism, relational logic does not specify cutoff points for distinguishing populism from non-populism. Thus, a theory of populism is a judgment upon the distances found across one or more of the three dimensions. Such judgments express relational distance; that is, a theory positions populism (p) along a spectrum in relation to a mainstream or non-populist position (non-p). This mainstream position may be either explicitly stated or merely implicit in the categorization. No theory of populism fails at least to imply such a positioning exercise. So, while in this article we refer to research that assumes populism does have ontological status, we argue that, as a judgment upon distance relative to an explicit or implicit norm, all theories of populism have a normative basis. And because of this normative component, there is no ultimate way to ascertain which theory of populism is objectively correct. At the same time, as we argue in the Discussion below, it allows the positing of testable hypotheses vis-à-vis a number of populism research questions because distance serves as a general parameter by which firmer distinctions might be drawn. The criterion of a judgment upon distance applies equally to the real-world rhetoric of those who deploy the term ‘populism’ to characterize other political actors, where distancing has a pragmatic, strategic aim. Accordingly, this approach can account for often-inconsistent vernacular uses of the term ‘populism’ in the public sphere.Footnote77

3.2. A relational framework for populism

The heuristic can be elaborated in its individual components and represented diagrammatically for each of the three questions, as per the performative level. sets out the relational logic of the theory of populism as ideology. However, given that populism is a ‘thin’ ideology, without any specific program, the figure represents the policy positions of populists marked by their difference from mainstream actors. The figure depicts the relational positioning of populism as distant from a mainstream or center (ethos). Populist actors or parties (p) are positioned against this in a space of otherness (pathos); that is, they are external to the implied normative center ground. The normative element of a theory of populism is evident in that the affective positioning in pathos usually carries a pejorative connotation, with the broad center or mainstream policy position the starting point from which deviations are labeled ‘populist’, even if contested norms about any given policy problem are not explicitly specified. The implied normative center () captures those rhetorical and policy elements of centrism that politicians use to define what Ostrowski calls the ‘mainstream’, but we take further his reference to the center as ‘a middle path’ or a ‘counter-pole’Footnote78 to extremes by suggesting the center is fought-over territory for those actors framing their appeals to public acceptability as a means of protecting (their) political power from populist competitors. That center ground can be occupied by political elites as well as by non-populist players adhering to cautious, deliberative policy processes consistent with convention. This approach is explicitly relational, variously accounting for differentiations within conventional scholarship on left-right differences, attitudes toward power and authority,Footnote79 as well as on other policy matters such as immigration, morality, or even COVID-19 vaccine-sourcing policy. The latter example highlights that populist differentiation also occurs with respect to policy as well as ideology.Footnote80

To reiterate: reflects how populist parties and actors are typically described in distal terms, as ‘far left’ or ‘far right’ on a continuum. Earlier research argued that only right-wing positions are populist, but it is now accepted that populists can be located at either end of the spectrum.Footnote81 This positioning necessarily implies that there is a non-populist position, which is not ‘far’, or distal, but somewhere in the center of the scale. This zone is not always specified by theorists; it is an implicit normative center ground occupying the space of mainstream, non-populist or even ‘anti-populist’ values. The center might be territory defined and defended by self-interested political insiders, as we implied above; but equally, it could also be conceived as the site for deliberation integral to both liberal and social democratic governance styles, ones that are undervalued in the rhetoric and styles of both right-wing and left-wing populism.Footnote82 Either way, in a relational framework, such positioning need not be at a fixed point. The normative center shifts continuously because of deliberative processes. And, as we illustrate further below, non-populist occupiers of political power have incentives to shift this point to maximize advantage over populist challengers, just as populists portray the political center as the zone of elite ‘betrayal’ or the heart of ‘secretive’ and ‘out of touch’ power or as a place where excessive compromise and deliberation frustrates the popular will becoming policy.

Populists can also be considered to exemplify the extreme end of a systematic shift by governing actors toward proximity to citizens.Footnote83 Proximal modes of engagement and connection with citizens’ emotional experiences are becoming a new norm in policy and governance, such that populists can be understood as moving ahead of or in tune with this general shift to get nearer to voters. In conditions of weak legitimacy, in which trust has become conditional, populists are able to project the ethos necessary to discursively re-generate authority.Footnote84 When combined with the increasing importance of victimhood in public life, understood as the experience of lack of recognition,Footnote85 this scenario helps explain populist success and how populists must rhetorically construct rivals as distant elites to maintain their own closeness to voters. Media may play a ‘mediating’ role here in highlighting and defining distance, one that populists learn to either court or exploit. Research, mostly focused on European countries, has variously shown that a wide cross-section of media has adapted to the rise of populist politics and themes.Footnote86 This mediating role reflects the media’s responsiveness to the populist style (which simultaneously maximizes audience attention) as well as its role in ‘gatekeeping’ and agenda-setting functions that determine the level of populists’ access to the public. Perhaps best illustrating the latter is the need for populists to prevent their distance from the political center becoming unacceptably extreme; they court political acceptability as well as distance – and media access and coverage matters. Bos, van der Brug, and De Vreese see the media giving populists access to ‘authoritativeness’ and capture the distance-proximity ‘balance’ in their concluding remarks: ‘in order to be successful, a right-wing populist leader must reach a delicate balance between appearing unusual and populist or anti-establishment in order to gain news value, on the one hand, and still appearing authoritative, or part of the establishment, on the other’.Footnote87

Theories of populism propose populist distanciation occurs through a variety of methods. Some specify types of ideological divergence as populist based on empirical data pertaining to policy positions and ideological beliefs.Footnote88 By contrast, Hofstadter established relative distance through psychological metaphor: via the ‘paranoid’ stance or style of the populist emphasizing hidden motives or the unknown ‘true’ character of elites.Footnote89 Regardless of how precisely or metaphorically these distinctions might be assessed, the common property is relative distance. In political practice, establishing distance depends on the position of the object party in relation to mainstream parties, which in turn allows critics to respond, deriding the former as ‘populist’. When former British Labour Party leader, Ed Miliband, proposed regulating electricity prices in 2013, this interventionism was decried as ideologically populist by opponents and the media.Footnote90 However, when Theresa May’s government adopted the same policy four years laterFootnote91 it could no longer be described as ‘far left’ because it had shifted the agreed space in the center of politics. A relational account thus shows the dynamism of populism in practice as the moving of distances and claiming of territory, such that all populists employ strategy in seeking powerFootnote92 against ‘anti-populist’ forces.Footnote93 This is also why politicians or parties branded ‘populist’ sometimes resist that label; for them, it is only their convictions that are important. In other cases, they may embrace it to explicate their positional distance from the mainstream.

The second dimension () concerns the populist use of discourse or rhetoric. As already implied, there are two distances at work in theories of populist strategy-one vertical and the other horizontal – and both surface in rhetoric. Scholars identify two main features, namely: 1) anti-elite rhetoric, marked by the pathos of anger and resentment, and 2) anti-Other rhetoric, marked by fear and resentment.Footnote94 The first is central to all forms of populism, while the second appears only in its right-wing variants.Footnote95 These identities of outsiders – whether foreigners or domestic subversives – are characterized as starkly different from the populist’s audience, which is represented as the ‘true’ norm, but which has lost status and been treated unfairly or disrespectfully.Footnote96 Rhetoric both explicates this distance and exaggerates it, involving repetitive derogation and even mockery of the identity of the Others, fostering resentments against them. More generally, populist rhetoric responds to distanciation produced by modernization. Growing wealth inequality, supra-national governance, and super-diversity all prompt the public to seek explanations for greater social distance, a search to which populists provide an answer.

Figure 3. Populism as discourse: rhetorical positioning of elites and others in regard to the people.

Rhetoric about elites explicitly emphasizes a distal relationship via spatial metaphors – references to ‘the Westminster bubble’, ‘inside the Beltway’, and ‘down there in Canberra’ – which use geographical references to distance ordinary people from elites. Other populist rhetoric uses another tactic – insult – to differentiate elites. Former UK Member of the European Parliament, Nigel Farage, derided then President of the European Council, Herman van Rompuy, for having ‘the appearance of a low-grade bank clerk and the charisma of a damp rag’.Footnote97 The aim was to use ‘personal attack’Footnote98 to infuse the distance between elites and people with strong emotions of anger and resentment. In Farage’s case, this distancing was perfected through the insulting depersonalization of his target, as well as through the question ‘Who are you?’. Rhetorically, elites must by definition remain at a distance – they are constructed as aloof, unknown, and even unknowable. Similarly, ‘enemies’ are put out of reach, with populist rhetoric continuously reinforcing the impossibility of forging common identity or dialogue.

Distance is also invoked about the ideology of elites, which is deemed ‘out of touch’ with the opinions of the average citizen. Indeed, elites and insiders are described as having an attitude related to the desirability of hierarchical distance, as they ‘look down their noses’ at ordinary citizens.Footnote99 These attributions imply that leaders should be like, or at least liked by, the people whom they govern. Hence, populist discourse targets a nativist working class constructed as ‘outsiders in their own country’, who feel that they live very different lives from the professional political class, or a conservative middle class disenfranchised by ascendant liberal values.Footnote100

The difficulty of a discursive definition of populism is that it includes use of such rhetoric by non-populists. Media actors regularly delight in mocking politicians, such as when President Gerald Ford fell down the stairway of Air Force One.Footnote101 People like seeing elites ‘reduced’, as evidenced in the popularity of political satire, and therefore such rhetoric is insufficient to account for populism per se. Ad hominem arguments in political discourse are also common, and not just deployed by populists.Footnote102 Populist politicians do play on emotions by resorting to anti-elite and anti-outsider rhetoric, but it is not exclusive to them. We argue that only strong rhetoric that produces a large increase in distance between elites and ‘the people’, with a consequent strong emotional rejection of the former, is populist. While ad hominem arguments are common in politics, populists make use of more insulting, impertinent derogations of rivals – e.g. ‘Crooked Hillary’ – frequently and in ways in which the ad rem (pertinent) content is almost entirely removed.Footnote103 This is so much the case that relinquishing ad rem substance becomes part of the populist trope in its very performance, evident, for instance, not only in its low styleFootnote104 but in its boorishness.Footnote105

Rhetoric is a relational concept that admits great variation in how orators position their targets. Structuralist discourse theories, by contrast, characterize populist language as making the starkest possible differentiations between people and others. It can, of course, be the case that Others are radically distanced, but it is always a matter of degree (argumentation permits adjustments to degree by allowing speakers to row back from or attenuate previous extreme statements; Nigel Farage has done this effectively). This logic permits a range of rhetorical devices to generate variable distance between ‘the people’ and elites or outsiders. Some propose that fear is definitive of populist rhetoric.Footnote106 But this seems both too restrictive and insufficiently exclusive. While hatred for target groups is certainly promoted by arousing fear in an audience (e.g. Nazi rhetoric about Jews), this is not a nuanced picture. Anger, as much as fear, has been found to be significant in promoting political tolerance and participation following terrorist attacks,Footnote107 with fear even promoting tolerance via collective value affirmation.Footnote108 And it is resentment of, and anger at, elites that is central to populist rhetoric. This rhetoric is often accompanied by rousing, positive appeals to unite ‘the people’ in support of a populist figure. One example is former president Donald Trump’s slogan, ‘Make America Great Again’ that added uplifting appeals to complement negative depictions of liberal elites and immigrants.Footnote109 Strong emotions – positive and negative – create a distal relationship to elites, uniting supporters against them.

The problem of exclusivity reemerges if we step outside relational theory. Fear, for instance, is neither a necessarily negative emotion nor is it exclusive to populism. It is rational and sensible to be fearful in certain circumstances. Central bankers generate fear of recession to persuade governments to stimulate investment and consumption.Footnote110 And, while fear of crime is used by populists to stir up resentment of Others, promoting ‘fear’ might be sensible when used by police to encourage vigilance in areas of high crime. In the same way, some approachesFootnote111 emphasize the creation of a ‘chosen people’ in populist rhetoric, which exacerbates difference from outsiders. Again, this is also insufficiently exclusive: all nationalist rhetoric creates emotions about ‘unique’ national character.

Theories of populism are therefore distinguishable based on the judgments they make about the distance at which the discursive characterization of elites and outsiders is great enough and sustained enough to be classed as populist. In , the diagonal line between elites and Others indicates the link made in populist rhetoric between resentment of distant elites and their contrasting, proximal relation to resented Others, evident in the prioritization and protection given to outsiders, rather than to the legitimate ‘people’. Pim Fortuyn, for example, strongly linked Dutch party elites to the protection of immigrants – especially Muslims – who were portrayed as receiving undue favoritism at the expense of ordinary citizens.Footnote112 Equally, Trump’s ‘birther’ rhetoric about Obama joined the former president’s elite status to his ‘outsider’ status in relation to the American citizenry.

The third dimension of ideational theories of populism concerns leadership style. Closely related questions of demagoguery hark back to Plato’s (Gorgias) denigration of rhetoricians for ruling by pandering to the desires of Athenian people. Of more recent heritage is Weber’sFootnote113 concern for the emotional release offered by charismatic leaders and how that might transform the political order, a quality found by PappasFootnote114 to be important in successful populism. Leadership style in populism is represented in . Differing from the distal relationships above, a populist leader promotes a proximal relationship with followers, who are united in admiration for him or her. As this distance shrinks, this relationship becomes more impassioned, marked by stronger pathos. Conventional politicians, by contrast, are responsive to norms of impartiality and fairness, constructing a virtue out of their distance from constituents and their conformity to formal interaction. All politicians have recourse to populist styles, but only populists constantly cultivate proximity between themselves and their followers.

Theories of populism highlight the close relationship between a populist leader and ‘the people’, one marked by strongly felt emotions of admiration, respect, and identification. Populism scholars argue that this has powerful effects.Footnote115 The leader’s character – inferred from background, persona, dress, and symbolic gestures – generates reverence and loyalty. This character (ethos) is persuasive in and of itself, such that populists can persuade people to hold ever more extreme ideological positions and views against outsiders that go beyond the reach of accepted norms. Hence, populist leaders are considered dangerous because they inspire strong emotions that move citizens to challenge the established order. Populist leaders appear to be ‘just like us’, or at least able to communicate ‘in a language we understand’, or to exhibit a style that draws attachment and admiration.Footnote116 This might include dressing, performing, or speaking like their followers, in contrast to conventional politicians who maintain formal attire and business-like distance.

In conventional politics, there is an implied mainstream norm of greater distance related to the capacity to govern ‘responsibly’, whereby the lack of an emotional connection between state and society enables public officials to act in the public interest without undue concern for the feelings of individual citizens or groups. Thus, conventional leaders are implicitly assumed to be more rational because they can weigh evidence and decide on the best course of action without being directly influenced – and ultimately held to account – by those who lose out from their decisions. The bureaucracy attains its autonomy by operating at an even further remove from direct relationships with citizens, so it must always rationalize its decisions and not prioritize public sentiment.Footnote117 The exemplar of this problem is the European Union. Designed as a rational, coordinating bureaucracy rather than a responsive political entity, its unelected officials are easy to portray as distant from citizens. But while populists proclaim that bureaucratic states are too remote, their defenders understand this distance supports civil society as a realm of freedom and government as able to operate in the former’s best interests, because it is less subject to the whim of the public mood. Populists are, therefore, decried for being too responsive (i.e. close) to unstable public sentiment rather than making the sober calculations in the public interest enabled by distance.

Emotions are, however, central to voter engagement in election campaigns.Footnote118 Here again, we note the point that, whereas the basis of legitimate government previously implied a distant state, the norms of governance are shifting to more proximal governing institutions and candidates who pay attention to the particularities of citizens’ experiences.Footnote119 Hence, populists have an advantage in contemporary conditions which they have helped create – and these are reinforced by digital communications technologies that connect political actors directly to their publics. ‘Remote’ government generates impressions of elite rule. Populist ‘anti-politics’ responds, generating pressure for ‘disintermediation’ – the overcoming of existing intermediate organizations in favor of strong, direct links via identity.Footnote120 Mediating organizations – houses of democratic deliberation, or dispassionate, technical policy advice, neutral systems of justice, and a public sphere organized around professional journalism – deliberately engineer distance between decision-making and popular interests. That makes these organizations (courts, supra-national bodies, mainstream media, etc.) targets for populists who portray deliberative distance as a source of social ills, seeking to replace this organizational layer with popular rule or at least the ‘threat of it’ as a disciplinary tactic. And occasionally these threats of organizational retrenchment are realized – the example from 2023 is Argentinian President Javier Milei’s intention to abolish the Argentinian Central Bank. Our point: these competing strategies show how populist efforts at dynamic configuration follow the ‘distal-proximal’ type presented above.

4. Discussion and conclusion

The final section summarizes novel features of this framework, illustrating its value to the social science of populism. By transposing three main properties of populism into a relational framework, grounded in rhetoric and distance, we establish a common basis for theories of populism, which confronts the degreeism problem. Populism theory involves a judgment on relational distance across a coherent totality of three dimensions: ideology, discourse/rhetoric, and leadership style. While theories emphasize one dimension more than the others, they nonetheless share these dimensions. In turn, the three dimensions can be rendered in common with one another by the discovery of an underlying conceptual basis, namely relational distance.

With regard to distance on the three relational properties in question, our account of populism arrives at this general, conceptual framework: distal–distal–proximal. Populist policy positions are departures from the center of the policy spectrum (distal), populist rhetoric explicates and increases distance from elites and/or outsiders (distal), while populist leaders draw close to their followers (proximal). Making judgments about the above carry within them an implied or explicit normative dimension, as a verdict on the extent of distance. Most often this is critical, insofar as populist distance is deemed to be negative, as being too far or too close. However, it can involve a positive characterization when left-wing populists are praised for challenging distant neoliberal elites or when mavericks are praised for standing apart from a corrupted mainstream. Even so, the normative dimension of populist theory implies a conventional, acceptable ground for political action, i.e. what populism is not.

Thus far, scholars have been divided about whether populism is primarily an ideology, a type of discourse/rhetoric, or a style of leadership. Our theory accommodates all three alternatives, synthesizing them as overlapping dimensions of distanciation. Populist leaders promote policies based on distinctive ideas (ethos) beyond the mainstream, such as curbs on immigration of particular races; they do so through rhetoric (logos) that exaggerates racial and religious differences between ‘the people’ and distant outsiders, in turn linking these to the protection and favoring of outsiders by elites who look down on ordinary citizens and neglect their interests; and they do it with a distinctive leadership style (pathos) by which they present, and perform, themselves as just like, or close to, ‘the people’, with the intention of generating passionate attachments. Populism, therefore, can operate along all three dimensions simultaneously, with each dimension feeding into the others. However, we can distinguish strongly populist figures from politicians who merely use populist tactics in certain circumstances, utilizing only one dimension or using the three dimensions inconsistently.

4.1. Relational distance and the social science of populism

The utility of this framework is ultimately established by the quality of insights it can generate when applied to the reality of populist politics. In particular, it generates a clear agenda for populism research by obliging researchers to describe and catalog, in social scientific terms, the distal–distal–proximal relations that we argue are inherent to populism. At the same time, the theory enables testable hypotheses for further research. It can underpin novel propositions for the success or failure of populists in government or the disappearance of populists from the political scene. For example – it has been argued previously that incompetence was the prime reason for the failure of populist governing parties.Footnote121 Our theory raises an alternative explanation: that reductions in distances resulting from participation in governing eventually undermine support for populists by violating the general model. Prolonged periods in office force populist governments to compromise with bureaucracies, deliberative processes, or deal with conventional policy belonging to the center ground, such as health and education. Forced to moderate ideological stances (i.e. less distal), populists succumb to the machinations of pluralist democracies, not to mention international pressure. Pressures to compromise also produce more conventional language (again, less distal), given that radically oppositional rhetoric can be difficult to sustain over long periods. Equally, populists in government appear in parliaments and government buildings, at official occasions, and on television dining with world leaders. They come to resemble elite figures, undermining former similarities to their supporters (i.e. less proximal). Relational features in our approach also allow for a dynamic exploration of practice, for instance via retaliation of the ‘mainstream’, claiming back populist territory by redefining it as within the center ground and forcing populists to extremes beyond acceptability. Indeed, one further advantage of the relational approach is to frame populist politics as part of a shifting ‘combat zone’ with non-populist rivals where the positioning of the latter is just as illuminating about the politics of the former.

A contrasting example of sustained populist success illustrates the same dynamics. Former US President Trump defied the pressures described above, sustaining tactics of proximity and distanciation. Trump kept close to core supporters by continuing mass rallies, even in non-election periods, and using Twitter to project rhetorical authenticity.Footnote122 His radical rhetoric continued attacks on immigrants and foreign interests, on former Democratic candidates and ex-President Obama, and pursued a ‘culture war’ against liberal elites. At the same time, US executive – legislative relations meant that Trump could sustain an oppositional stance (i.e. distal) toward elites in Congress. It is unsurprising that the January 2021 rebellion against President Biden’s victory took place at the Capitol Building – the seat of government that Trump loyalists sought to recapture by physically collapsing distance from governing elites. Trump’s encouragement of and reliance on right-wing social media activism highlights the value of research that explains how social forces generate opportunities for relational distance in the first place. Clearly, conspiracy-based movements that overlap with right-wing extremism provide the ‘energy’ behind ideas that government is run by distant (‘hidden’) elites with dangerous agendas – much as HofstadterFootnote123 characterized in the 1960s.

These illustrations highlight a further potential of the framework: to bring diverse social science perspectives together to explain the emergence and maintenance of relative distance in populist political terrain.Footnote124 The role of political science in both description and analysis has been explored extensively but there is more to do in the discipline in generalizing the value of relational approaches. Sociologists have gone further down this path when they highlight the limits of unit or ‘variable-based analysis’ and focus instead on ‘transactional’ or relational dimensions in their analyses.Footnote125 Studies of power (Foucault) and inequality (Tilly) are seen as standout illustrations of this potential.Footnote126 Sociologists studying populism contribute to relational analysis where they identify the social forces driving distances between classes and groups as well as the generation of ‘us and them’ cultural distinctions that animate fears of immigration or of freedom-limiting central government. Important events – rising immigration, generational conflict, industrial decline, and new media – become cornerstones of analysis because they hold high potential for populists to frame social change as polarizing societal distances. Even more can be envisaged on the relational front once the political-organizational dimension is admitted. As we highlight via the role of the media in ‘mediating’ the zone between populist insurgency and the normative political center, accounting for the role of mediating organizations of other kinds in generating, managing, and closing off opportunities for populist distanciation adds empirical richness to explanation without compromising the underlying framework. At another level, psychologists account for and explain the processes of cognitive and emotional dissonance that fuel populist rhetorical efforts to ‘fuse’ individual and group identitiesFootnote127 or even group ‘destinies’ with the populist cause. Beyond the social sciences, neuroscience is investigating the evidence for common mechanisms of spatial perception and social cognition, including perceptions of social and hierarchical distance to understand the embodied reaction involved in the experience of distanciation.Footnote128

Turning to the methodological potential of our framework, we highlight its compatibility with mixed methods approaches. Our framework emphasizes synthesis across the three dimensions to discover how distances are established; in turn, this approach invites researchers to combine methods (used in separate dimensions) and compare results. For example, quantitative work already exists that ranks ideologies in relation to conventional positions across a range of policy areas.Footnote129 And similarly, the study of distanciation through rhetoric can be operationalized by qualitative, ordinal measures and changes in direction (closer, stable, farther).Footnote130 Distances measured in policy or ideological terms can then be mapped to rhetorical shifts and vice-versa, or efforts of populists to align closely with aggrieved groups.

Finally, this approach helps explain how and why the term ‘populism’ itself is used in political practice. To date, such an explanation has eluded scholars who widely accept the need for greater consistency in how the term is used in analysis and in the media. For instance, Bale, van Kessel, and TaggartFootnote131 report that the UK print media describe both support for, and opposition to, the public funding of political parties as ‘populist’. In the terms of our approach, the description of these respective positions as left-wing and right-wing highlights their perceived distance from the implied normative center ground, as judged from the perspective of journalists. But Bale et al.Footnote132also note common pejorative usage of the term, aiming to denigrate ‘political enemies and stances and policies’. In our framework, this category of populist usage is relationally coherent, insofar as the utterance of the term ‘populist’ is explicable as rhetoric designed to distance rivals from norms acceptable to an audience, whether the target is a rival party or opponents within one’s own party. The term ‘stance’ is indicative here: the significance of the populist epithet is found not in ontological definition, but in its use as rhetorical positioning.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. C. Mudde and C. Rovira Kaltwasser, ‘Studying Populism in Comparative Perspective: Reflections on the Contemporary and Future Research Agenda’, Comparative Political Studies, 51(13) (2018), p. 1669.

2. For example, P. Taggart, Populism (Buckingham: Open University Press, 2000); K. Weyland, ‘Clarifying a Contested Concept: Populism in the Study of Latin American Politics’, Comparative Politics, 34(1) (2001), pp. 1–22; C. Mudde, ‘The Populist Zeitgeist’, Government and Opposition, 39(4) (2004), pp. 541–563; E. Laclau, ‘Populism: What’s in a Name?’, in Francisco Panizza (Ed.), Populism and the Mirror of Democracy (London: Verso, 2005), pp. 32–49; J. Jagers and S. Walgrave, ‘Populism as political communication style: An empirical study of political parties’ discourse in Belgium’, European Journal of Political Research, 46(3) (2007), pp. 319–345; Y. Stavrakakis and G. Katsambekis, ‘Left-wing populism in the European periphery: the case of SYRIZA’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 19(2) (2014), pp. 119–142; Aslanidis, ‘Is populism an ideology? A refutation and a new perspective’, op. cit., Ref. 1; B. Moffitt, The Global Rise of Populism (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2016); B. Moffitt and S. Tormey, ‘Rethinking Populism: Politics, mediatisation and political style’, Political Studies, 62(2) (2014), pp. 381–397; J.-W. Müller, What is Populism? (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016).

3. Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, ‘Studying Populism in Comparative Perspective’, op. cit., Ref. 2, p. 1669.

4. C. Mudde, ‘Populism: An Ideational Approach’, in C. Rovira Kaltwasser et al. (Eds) The Oxford Handbook of Populism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017a), pp. 27–47.

5. S. van Kessel, ‘The populist cat-dog: applying the concept of populism to contemporary European party systems’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 19(1) (2014), p. 105.

6. See P. Aslanidis, ‘Is populism an ideology? A refutation and a new perspective’, Political Studies, 64(1S) (2016), pp. 88–104.

7. P. Ostiguy, ‘Populism: A socio-cultural approach’, in C. Rovira Kaltwasser et al. (Eds) The Oxford Handbook of Populism, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), pp. 73–101.

8. P. Ostiguy et al. ‘Introduction’, in P. Ostiguy et al. (Eds), Populism in Global Perspective: A performative and discursive approach (Abingdon: Routledge, 2020), pp. 1–18.

9. K. Weyland, ‘Populism: A political-strategic approach’, in C. Rovira Kaltwasser et al. (Eds) The Oxford Handbook of Populism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), pp. 48–72.

10. See M. Emirbayer, ‘Manifesto for a relational sociology’, American Journal of Sociology 103 (2) (1997), pp. 281–317 and P. Donati, Relational Sociology: A new paradigm for the social sciences (Abingdon: Routledge, 2011).

11. See inter alia M. Canovan, ‘Taking Politics to the People: Populism as the Ideology of Democracy’, in Y. Mény and Y. Surel (Eds) Democracies and the Populist Challenge (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002), pp. 25–44; Mudde, ‘Populist Zeitgeist’, op. cit., Ref. 3, p. 544; C. Mudde and C. Rovira Kaltwasser, Populism in Europe and the Americas: Threat or Corrective for Democracy? (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012); C. Mudde and C. Rovira Kaltwasser, ‘Exclusionary vs. inclusionary populism: comparing contemporary Europe and Latin America’, Government and Opposition, 48(2) (2013), pp. 147–174; R. Gerodimos, ‘The ideology of far left populism in Greece: Blame, victimhood and revenge in the discourse of Greek anarchists’, Political Studies, 63(3) (2015), pp. 608–25.

12. Mudde, ‘Populist Zeitgeist’, op. cit., Ref. 3, p. 543.

13. M. Freeden, Ideologies and Political Theory: A Conceptual Approach (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998).

14. Mudde, ‘Populist Zeitgeist’, op. cit., Ref. 3, p. 544.

15. Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, ‘Exclusionary vs. inclusionary populism’, op. cit., Ref. 11, p. 151.

16. Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, ibid.

17. Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, ibid.

18. K. A. Hawkins and C. Rovira Kaltwasser, ‘Introduction: The ideational approach’ in K. A. Hawkins, R. E. Carlin, L. Littvay and C. Rovira Kaltwasser (eds), The Ideational Approach to Populism: Concept, Theory and Analysis (London: Routledge, 2018), p. 4.

19. P. Taggart, ‘Populism and representative politics in contemporary Europe’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 9(3) (2004), p. 275.

20. Mudde and Kaltwasser, ‘Exclusionary vs. inclusionary populism’, op. cit., Ref. 11, p. 153.

21. B. Stanley, ‘Populism in Central and Eastern Europe’, in C. Rovira Kaltwasser et al. (Eds) The Oxford Handbook of Populism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), pp. 140–158.

22. M. Zullianello, ‘Varieties of Populist Parties and Party Systems in Europe: From state-of-the-art to the application of a novel classification scheme to 66 parties in 33 countries’, Government & Opposition, 55(2) (2019), pp. 327–347.

23. Hawkins and Rovira Kaltwasser, ibid., p. 9.

24. J. Dean and B. Maiguashca, ‘Did somebody say populism? Towards a renewal and reorientation of populism studies’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 25(1) (2020), p. 14.

25. Dean and Maiguashca, ibid.

26. Hawkins and Rovira Kaltwasser, ibid. p. 9.

27. D. Art, ‘The myth of global populism’, Perspectives on Politics (2020), pp. 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592720003552.

28. B. Bonikowski and N. Gidron, ‘The populist style in American politics: Presidential campaign discourse, 1952–1996’, Social Forces, 94(4) (2016), pp. 1593–1621; see also Weyland, ‘Populism: A political-strategic approach’, op. cit., Ref. 9.

29. Aslanidis, ‘Is populism an ideology?’, op. cit., Ref. 1, p. 93.

30. Aslanidis, ibid., p. 92.

31. Bonikowski and Gidron, ‘The populist style’, op. cit., Ref. 25.

32. Aslanidis, ‘Is populism an ideology?’, op. cit., Ref. 1.

33. Weyland, ‘Clarifying a Contested Concept’, op. cit., Ref. 3, p. 14; also K. M. Roberts, ‘Populism, Political Conflict, and Grass-Roots Organization in Latin America’, Comparative Politics, 38(2) (2006), pp. 127–148; R. R. Barr, ‘Populists, outsiders and anti-establishment politics’, Party Politics, 15(1) (2009), pp. 29–48; C. de la Torre, Populist Seduction in Latin America, (2nd edn. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2010).

34. J.W. Müller, What is Populism? (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016), p. 35.

35. W. van der Brug and A. Mughan, ‘Charisma, leader effects and support for right-wing populist parties’, Party Politics, 13(1) (2007), p. 31.

36. Weyland, ‘Clarifying a Contested Concept’, op. cit., Ref. 3, p. 14; also van der Brug and Mughan, ‘Charisma, leader effects’, op. cit., Ref. 32.

37. J. Charlot, The Gaullist Phenomenon (London: Allen & Unwin, 1971), p. 43.

38. van der Brug and Mughan, ‘Charisma, leader effects’, op. cit., Ref. 32.

39. van der Brug and Mughan, ibid., p. 32.

40. Barr, ‘Populists, outsiders’, op. cit., Ref. 30, p. 41.

41. van der Brug and Mughan, ‘Charisma, leader effects’, op. cit., Ref. 32., p. 32.

42. Barr, ‘Populists, outsiders’, op. cit., Ref. 30, p. 41.

43. Moffitt and Tormey, ‘Rethinking Populism’, op. cit., Ref. 3.

44. Ostiguy, ‘Populism: A socio-cultural approach’, op. cit., Ref. 7, p. 6.

45. Moffitt and Tormey, ‘Rethinking Populism’, op. cit., Ref. 3., pp. 392–393.

46. Mudde, ‘The Populist Zeitgeist’, op. cit., Ref. 3, p. 544.

47. Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, ‘Exclusionary vs. inclusionary populism’, op. cit., Ref. 11, p. 154.

48. L. March, ‘Left and right populism compared: The British case’, British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 19(2) (2017), p. 300.

49. Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, ‘Exclusionary vs. inclusionary populism’, op. cit., Ref. 11, p. 154.

50. P. Ostiguy and B. Moffitt, ‘Who would identify with an “empty signifier”?’, in P. Ostiguy et al. (Eds) Populism in Global Perspective: A performative and discursive approach (Abingdon: Routledge, 2020), p. 65.

51. Ostiguy, ‘Populism: A socio-cultural approach’, op. cit., Ref. 7, p. 6.

52. Moffitt and Tormey, ‘Rethinking Populism’, op. cit., Ref. 3., pp. 392–393.

53. Moffitt and Tormey, ibid., p. 387.

54. Ostiguy and Moffitt, ‘Who would identify’, op. cit., Ref. 47, p. 65.

55. Laclau, ‘Populism: What’s in a Name?’, op. cit., Ref. 3; E. Laclau, ‘Towards a Theory of Populism’, in E. Laclau (Ed.) Politics and Ideology in Marxist Theory: Capitalism, Fascism, Populism (London: Verso, 2011), pp. 143–199; E. Laclau, On Populist Reason (London: Verso, 2018); Y. Stavrakakis, ‘Antinomies of formalism: Laclau’s theory of populism and the lessons from religious populism in Greece’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 9 (3) (2004), pp. 253–267; F. Panizza (Ed.) Populism and the Mirror of Democracy (London: Verso, 2005); Stavrakakis and Katsambekis, ‘Left-wing populism’, op. cit., Ref. 3.

56. Laclau, ‘Towards a Theory of Populism’, op. cit., Ref. 52, p. 173.

57. Stavrakakis, ‘Antinomies’, op. cit., Ref. 52, p. 259.

58. Laclau, On Populist Reason, op. cit., Ref. 52, p. 96.

59. See Stavrakakis and Katsambekis, ‘Left-wing populism’, op. cit., Ref. 3; S. Hatzisavvidou, ‘Demanding the Alternative: The Rhetoric of the UK Anti-austerity Movement’, in J. Atkins and J. Gaffney (Eds), Voices of the UK Left: Rhetoric, Ideology and the Performance of Politics (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), pp. 211–230.

60. Laclau, ‘Populism: What’s in a Name?’, op. cit., Ref. 3, p. 47.

61. Aslanidis, ‘Is populism an ideology?’, op. cit., Ref. 1, p. 97.

62. Dean and Maiguashca, ‘Did somebody say populism?’, op. cit., Ref. 22, p. 18 (emphasis in original).

63. Dean and Maiguashca, ibid.

64. Ostiguy et al., ‘Introduction’, op. cit., Ref. 8, p. 7.

65. Ostiguy and Moffitt, ‘Who would identify’, op. cit., Ref. 47.

66. R. A. Y. M. Herrera et al., ‘Identity as a Variable’, Perspectives on Politics, 4(4) (2006), pp. 695–711.

67. M. Meyer, Of Problematology: Philosophy, Science and Language, trans. D. Jamison, with A. Hart (Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press, 1995); M. Meyer, What is Rhetoric? (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017).

68. Meyer, ibid.

69. Meyer, Problematology, op. cit., Ref. 64.

70. Aristotle (Rhetoric, I.2, 1355b35-1356a35); reframed by Meyer, Rhetoric, op. cit., Ref. 64.

71. Perelman, Chaïm and Lucie Olbrechts-Tyteca, The New Rhetoric: A treatise on argumentation, trans. J. Wilkinson and R. Weaver (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1969); L. F. Bitzer, ‘The Rhetorical Situation’, Philosophy & Rhetoric, 1(1) (1968), pp. 1–14.

72. J. Martin, ‘Situating Speech: A Rhetorical Approach to Political Strategy’, Political Studies, 63(1) (2015), pp. 25–42.

73. Meyer, Rhetoric, op. cit., Ref. 64, p. 9 (emphasis in original).

74. Aristotle (Rhetoric, II.5, 1382b20–25).

75. D. Maingueneau, ‘The Scene of Enunciation’, in J. Angermuller, D. Maingueneau and R. Wodak (eds) Discourse Studies Reader: main currents in theory and analysis (Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 2014), pp. 145–154; see also Martin, ibid.

76. C. Mouffe, ‘Which public sphere for a democratic society?’, Theoria: A Journal of Social and Political Theory, 99 (2002), pp. 55–65.

77. T. Bale et al., ‘Thrown around with abandon? Popular understandings of populism as conveyed by the print media: A UK case study’, Acta Politica, 46(2) (2011), pp. 111–131.

78. M.S. Ostrowski, ‘The ideological morphology of left-centre-right’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 28(1) (2023), pp. 9–10.

79. Ostiguy, ‘Populism: A socio-cultural approach’, op. cit., Ref. 7, p. 6.

80. M. van Ostaijen and P. Scholten, ‘Policy populism? Political populism and migrant integration policies in Rotterdam and Amsterdam’, Comparative European Politics, 12(6) (2014), pp. 680–699.

81. Jagers and Walgrave, ‘Populism as political communication’, op. cit., Ref. 3; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, ‘Exclusionary vs. inclusionary populism’, op. cit., Ref. 11; March, ‘Left and right populism compared’, op. cit., Ref. 45.

82. P. Johnson ‘In search of a leftist democratic imaginary: what can theories of populism tell us?’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 22(1) (2017), pp. 74–91.

83. P. Rosanvallon, Democratic Legitimacy: impartiality, reflexivity, proximity (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011), p. 171ff; C. Le Bart and R. Lefebvre, La proximité en politique: usage, rhétorique, pratiques (Rennes: Rennes University Press, 2005).

84. Amossy, Ruth, ‘Constructing political legitimacy and authority in discourse’, Argumentation and Discourse Analysis 28; https://doi.org/10.1000/aad.6398.

85. Rosanvallon, ibid, p. 190.

86. L. Bos, W. van der Brug, and C. de Vreese, ‘Media coverage of right-wing populist leaders’, Communications, 35(2) (2010), pp. 141–163; M. Hameleers and R. Vliegenthart, ‘The rise of a populist zeitgeist? A content analysis of populist media coverage in newspapers published between 1990 and 2017’, Journalism Studies, 21(1) (2020), pp. 19–36. M. Wettstein, F. Esser, A. Schulz, D.S. Wirz, and W. Wirth, ‘News media as gatekeepers, critics, and initiators of populist communication: How journalists in ten countries deal with the populist challenge’, International Journal of Press/Politics, 23(4) (2018), pp. 476–495.

87. Bos, van der Brug, and de Vreese, ibid., p. 159.

88. See inter alia E. Reungoat, ‘Anti-EU Parties and the People: An Analysis of Populism in French Euromanifestos’, Perspectives on European Politics and Society, 11(3) (2010), pp. 292–312; M. Rooduijn and T. Pawels, ‘Measuring Populism: Comparing Two Methods of Content Analysis’, West European Politics, 34(6) (2011), pp. 1272–1283; M. Rooduijn et al., ‘A populist Zeitgeist? Programmatic contagion by populist parties in Western Europe’, Party Politics, 20(4) (2014), pp. 563–575.

89. R. Hofstadter, ‘The paranoid style in American politics’, Harper’s Magazine, November 1964.

90. J. Norman, ‘Ed Miliband has given us a masterclass in dishonest populism’, The Telegraph, 25 September 2013, Retrieved May 30, 2022. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/politics/labour/10333499/Ed-Miliband-has-given-us-a-masterclass-in-dishonest-populism.html; Telegraph Staff, ‘Ed Miliband’s flagship policy is populist but crazy’, The Telegraph, 24 September 2013. Retrieved May 30, 2022. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/newsbysector/energy/10332110/Ed-Milibands-flagship-policy-is-populist-but-crazy.html.