ABSTRACT

This article explores some of the impacts of Brexit on governance in Northern Ireland. A devolved region administered by a fragile and often fractious consociational system, Brexit, and, in particular, the fundamental legislative mechanism through which Brexit is implemented, the December 2020 Northern Ireland Protocol, have worked to increase division across several levels - the inter-governmental, that of regional party politics, and that of grassroots, inter and intra-communal relations. To complicate matters further, that distrust has also markedly manifested itself in the growth of non-aligned political dynamics. Drawing on the work of Pierre Rosanvallon, I suggest that these developments can be conceptualized with reference to ideas about counter-politics and distrust.

The Belfast/Good Friday Agreement (B/GFA) of April 1998 was an attempt to cultivate peace by establishing a functional government in Northern Ireland.Footnote1 It did this by providing a political structure in which the main political representatives of the two ethno-religious blocs could administer the province while not being required to attenuate their fundamental ideological distinctions (unionists wishing the maintenance of the constitutional links with the rest of the United Kingdom and nationalists wishing to end partition on the island of Ireland). As such, it represented what Pierre Rosanvallon would refer to as an exercise in the ‘organization of distrust’ (Rosanvallon, Citation2008, p. 5). As one of the most-cited theorists of the consociational theory that seemed to reflect the new arrangements explained, the devolved aspects of the 1998 settlement involved the recognition that ‘ideologically barricaded organisations may be best induced to withdraw from violence if an internally principled path can be found for their members to abandon their use of violence’ (O’Leary, Citation2005, p. 224). In other words, the B/GFA demonstrated how ethnic fears and suspicions, principles and prejudices can be filtered away from violence and conflict into functioning democracy through careful institutional design.

Just as it is ‘wishful thinking’ to hope that deep-rooted ethnic antagonisms can be easily set aside for antagonists to integrate in the cause of peace (McGarry & O’Leary, Citation1993, p. 20), likewise it was fanciful to hope that those feelings of mistrust could be contained in governance structures. Although mistrust and distrust are synonymous, in verb form, mistrust connotes attitudes, beliefs, intuitions of unease and uncertainty. This is much harder to quantify and massage by institution-building than the verb distrust, which tends to connote specific experience and certain knowledge that substantiates doubt. The mistrust endemic to the ethnic divide in Northern Ireland, then, represents the excess to the organisation of distrust in the B/GFA institutions. The Northern Ireland Protocol sets the terms of Brexit for Northern Ireland by effectively drawing a customs and regulations border between Northern Ireland and Great Britain, it keeps the North in the European Union Single Market with the Republic. This paper argues that it has not only come to emblematise that mistrust – certainly for Ulster unionists and loyalists who see it as a fundamental breach of the UnionFootnote2 – but it is, fundamentally, constitutive of it given that it reverses the fudges and choreographies of the peace process (colloquially known as ‘creative ambiguities’ (Dixon, Citation2002)) with a zero-sum inflection point where there can, seemingly, only be a border in one of two places – between the Republic and the North or between Northern Ireland and Great Britain.

The distinction might be a fine one but the implications of the substituting of a politics of (managed, consociational) distrust for one of mistrust might well mean an overturning of the existing dispensation in Northern Ireland. Disputes over the Protocol have left Northern Ireland without a government since the start of 2022 and unless some kind of workable solution can be found, then, as The Economist (Citation2022, November 5) opined, there seems to be ‘no discernible path to devolved government for a very protracted period, perhaps a decade or more’ (p.5). Given that devolution represented the key plank of the B/GFA (see below), were it to be jettisoned, it would seem that (at the time of writing) the historic accord will not progress much beyond its twenty-fifth birthday.

Interpreting the Northern Ireland protocol

When Doug Beattie, the leader of the longest surviving and second largest unionist party, the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP), pulled out of rallies protesting the Northern Ireland Protocol his constituency office was targeted.Footnote3 He stated that the ‘cowardly attack’ was an ‘inevitable consequence’ of his condemnation of the rallies, which he felt were ‘raising tensions’ (BBC, Citation2022, March 28). The Protocol has not only revealed the profound gaps of trust between the main ethno-religious blocs (and between Northern Irish politics and Dublin and Westminster) but also, emphasised the limitations of democratic practice. These limitations were recently described by Robert Shrimsley (Citation2022, april 28, p. 21), writing in the Financial Times:

The deal [the Protocol] placed Northern Ireland within the EU single market for goods, creating a trade barrier in the Irish Sea. This has led to often onerous customs checks on British goods [coming from Great Britain to Northern Ireland]. Some mainland retailers have decided it is no longer worth the trouble selling to the province. The problems were foreseen when the UK signed the Protocol, but the EU’s implementation has been inflexible, focused on theoretical rather than real threats to the single market. All parties in Northern Ireland agree the Protocol’s implementation needs reform, not least because it is still not fully in force.

Nationalist-oriented commentators have, on the other hand, been largely welcoming of the Protocol. Northern Ireland had voted 44–56 per cent in favour of remain in 2016 and nationalist parties had come to look favourably on the Europe after 1998 as a way of transcending the nation-state boundaries of the UK. Following this logic, the effective prolongation of Northern Ireland within the EU (that is, the Single Market) is evidence of the inevitability of partition. For example, as Kevin Meagher (a former Labour adviser and author of a 2016 book entitled A United Ireland: Why Unification is Inevitable and How it Will Come About) argued in the pages of the Belfast papers published by Maírtín Ó Muilleor, the former Sinn Féin politician, that the Protocol has rearranged the political dynamics:

In chess, they call it ‘zugzwang.’ It is not quite checkmate, but it’s the point where the game starts to become irretrievable. Every move, (and, for here read every issue), weakens the overall position. There is no prospect of rallying to recover it. So, yes, ‘inevitable’ is a word that leaves little room for chance. (Meagher, Citation2022)

If the Protocol is being interpreted as having radically changed the political context by both unionist and nationalist commentators, then Beattie’s strategy might itself be considered wishful thinking: He may have been calculating that as unionist politics pulled towards extremes there was space to be won in the centre ground (see next section below). Yet his vision has a certain Panglossian character when read against the thesis that a movement from distrust to mistrust has occurred and that the latter sentiment is structured by the zero-sum nature of the Protocol wherein a unionist loss (a sea border) is an Irish nationalist gain (no land-border).

Distrust in Northern Ireland

A deeply divided society and (despite a peace process stretching back to at least the paramilitary ceasefires of September 1994) a site of continuing, everyday ethno-religious distinctions, Northern Ireland sheds light on some of these overlaps. The fundamental aim in establishing a devolved assembly in Northern Ireland was to bring to an end the three-and-half-decades of violence, euphemistically known as ‘The Troubles’, that had resulted in 3,636 deaths (McKittrick et al., Citation1999). This violence percolated through all levels of Northern Irish society and had profound affects throughout the UK and Ireland. The key protagonists were as follows: Irish Republican paramilitaries, who held that physical force was the only appropriate response to what they perceived as illegal British occupation of the north of Ireland, were responsible for just under 60 per cent of the deaths; Loyalist paramilitaries, who held that they were defending their communities from Republican violence, were responsible for just under 30 per cent of the deaths; British state security forces, including the army and the local police force, the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) were responsible for just under 10 per cent (the outstanding percentages relate to killings where attribution remains uncertain). In proportional terms, the killings would translate as around 100,000 deaths in the UK or 500,000 in the United States. Around 40,000 other individuals were injured as a result of the hostilities and perhaps around one out of every three families in Northern Ireland were affected by the violence in some way (Edwards & McGrattan, Citation2012).

The 1998 Agreement was structured around three strands. Strand One covered matters internal to Northern Ireland and provided for the establishment of a devolved Assembly, elected on a proportional basis and administered through power-sharing. It also provided for the establishment of what proved to be a short-lived consultative body, a Civic Forum, and for the Assembly to have responsibility for administrative matters transferred from Westminster. Strand Two provided for a North/South Ministerial Council, to ‘develop consultation, co-operation and action within the island of Ireland’ (NIO, Citation1998). Strand Three, meanwhile, focussed on the ‘totality of relationships’ between Ireland and Britain and provided for a British–Irish Council consisting of representatives from the British and Irish governments along with devolved bodies throughout the UK, and a British–Irish Intergovernmental Conference, comprising of representatives from Dublin and London.

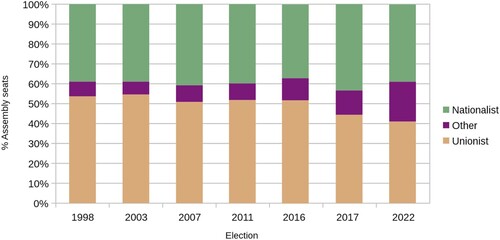

Elections since 1998 have seen no real movement in the aggregate vote for the two main nationalist and republican parties, the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) and Sinn Féin (see ). The latter has been the main representatives of the Catholic community, which tends to favour reunification with the Irish Republic and has a cultural outlook that is Irish in orientation. That aggregate has hovered around 40 per cent. The majority Protestant and Ulster unionist community favour retention of the Union and hold a broad British cultural outlook. The aggregate vote for the two main unionist parties, the more religiously conservative and larger Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) and the more liberal Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) has declined from just over 50 per cent in 1998 to just over 40 per cent in the May 2022 Assembly election. The middle-ground Alliance Party has seemingly assumed some of those votes, enjoying an upward tick (mainly since 2017) from about 10 per cent of voters to 20 per cent. Alliance tends to be liberal and bourgeois in orientation (it is affiliated with the Liberal Democrats in Great Britain) and is constitutionally neutral in that it foregrounds the principle of consent.Footnote4

Figure 1. Aggregate votes by ethnic bloc, 1998–2022.Footnote9

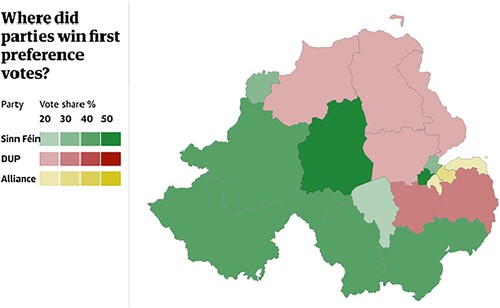

The principal outcome from the May 2022 election was inarguably Sinn Féin topping the poll (66,000 first preferences ahead of the DUP) and also winning the most seats, meaning that for the first time in Northern Ireland’s 101-year history a nationalist party, rather than a unionist one, was in the majority. However, as the political commentator Malachi O’Doherty (Citation2022) pointed out, given the stasis in the overall nationalist vote, the real change had occurred in the development of a local third-way – in the Alliance ‘more than doubling its seat count and becoming the most credible expression of a non-sectarian middle ground that we have ever had’. Even so, Northern Ireland remains starkly divided: split more or less in two geographically, with unionist votes predominant in the east and nationalists in the west of the province (see ).

Figure 2. Northern Ireland Assembly Election, 2022. Map of first preference votes.Footnote10

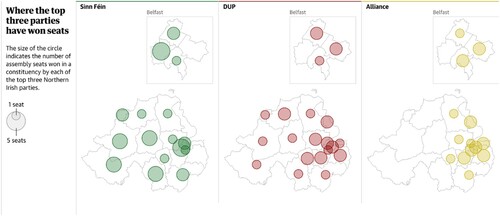

The Protocol has escalated these divisions: On the one hand, the EU referendum vote was more or less replicated in terms of party seat victories (60 per cent of Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs) support the Protocol versus the 40 per cent of unionist MLAs who are opposed).Footnote5 On the other, unionism has found itself fragmenting and confused: The hard-line anti-Protocol Traditional Unionist Voice party won 7.6 per cent of the vote (though that translated into only one Assembly seat) – the DUP were down 7 per cent from 2017 (though only a loss of 2 seats). This seems to be compounded by the fact that the Alliance seems to have drawn the sum of its seats from what might be described as the ‘unionist-east’ (see ).

Figure 3. Northern Ireland Assembly Election 2022, Location of Assembly Seats won.Footnote11

The protocol and mistrust

The centrality of mistrust in shaping outcomes is clear in Rosanvallon’s more recent texts on democratic (see Rosanvallon, Citation2006, Citation2008, Citation2011, Citation2018). For Rosanvallon, mistrust can take two forms: the first relates to the liberal distrust of power, institutionalised and routinised politics foster relations of exclusion and exclusivity that become reproduced across time; factionalism is a logical response to those self-reinforcing dynamics, but that simply gives rise to other forms of elitism (Rosanvallon, Citation2008, pp. 6–8). As Rosanvallon points out, this critique has engaged thinkers from Hobbes and Montesquieu to Madison and Tocqueville. The second type focuses on ideas about the common good, which he describes as democratic mistrust. This, he states, operates within representative democracy – although it can take the form of the anti-politics of apathy and cynicism, it can also be their mirror image, promoting vigilance and engagement (Citation2008, p. 24). Mistrust, is therefore, he argues not the opposite of democracy but a different way of doing it as it is ‘a constitutive rather than a recent feature of democratic life’ (Rosanvallon, Citation2006, p. 237). Counter-democracy, as he terms the set of practices and modes of behaviour based around a politics of mistrust, is ‘a form of democracy that reinforces the usual electoral democracy as a kind of buttress, a democracy of indirect powers disseminated throughout society – in other words, a durable democracy of distrust, which complements the episodic democracy of the usual electoral-representative system’(Rosanvallon, Citation2008, p. 8).

Whereas Rosanvallon’s notion of counter-democracy entails elements of checks and accountability – by which government is restricted by popular distrust and suspicion regardless the electoral process – Brexit and the Northern Ireland Protocol, in particular, sits outwith the possibility of popular intervention through routinised political avenues. Although Rosanvallon writes of the countervailing power of civil society that can act to prevent or restrict government, the Protocol itself demotes electoral representation and denotes party differentiation.Footnote6 In other words, the post-Brexit dispensation has reinforced the devolved aspects of devolution by rendering much less clear and much more ambiguous the relationships between centre and periphery. In the process, the ever-present politics of alienation, fear and mistrust become exacerbated.

The lack of clear authority or capacity is much in evidence in the uncertainty surrounding the ability of local politicians to project any kind of authority in and about that dispensation. This is why it is a rather partial view of the B/GFA to reduce it merely to the politics of recognition – an example being the revealing intervention (2022) by a recently retired official, Andrew McCormick, who had been Director General for the Northern Ireland Executive Office. McCormick’s briefing suggested that:

unionists cannot legitimately claim that the consequences of Brexit have to be addressed only on their terms, because the whole basis of the 1998 Agreement was recognition of the legitimacy and relevance of different viewpoints on the issues of identity in Northern Ireland (Citation2022, pp. 5–6).

It is that very lack of a conduit to accountability or transparency that perhaps explains why the strategic options of the two main unionist parties seem so threadbare. For instance, the DUP’s main position seems to be to boycott the devolved executive unless the Protocol is abandoned. As Shrimsley (Citation2022, April 28) points out:

Intransigence is almost its last electoral gambit after a litany of political errors which included supporting Brexit (while opposing every model of how it might work) and siding with Boris Johnson only to see him do a deal which sacrificed the union’s integrity for the purity of Brexit on the mainland.

The UUP’s, Citation2022 manifesto devotes more detail to the Protocol – and is even slightly larger than the DUP’s in proportionate terms (one and a half pages out of forty) (UUP, Citation2022). Although the manifesto rejects the notion that there can be a border in the Irish Sea, it frames its proposals within the ‘desire to have no added friction either North/South or East/West’. Again, an ideational genealogy might be mapped – the third ‘strand’ of the B/GFA, East/West relations, taking into account the entirety of the British archipelago, was closely associated with the UUP’s leader at the time of the negotiations, David Trimble. Among the party’s proposals is the idea contained in the UK Command Paper, ‘Northern Ireland Protocol: The way forward’ of July 2021 (HMG, Citation2021) to make it a criminal office to ‘knowingly export goods designed for the UK Internal Market into the EU Single Market’ (UUP, Citation2022, p. 12). This would seem to refer to smuggling – though the crime would only apply to individuals apparently: ‘The UK could undertake to indemnify the EU if it was found that Northern Ireland had been used to export non – compliant goods via the land border on the island of Ireland into the EU single market’ (UUP, Citation2022). Evidently cognizant of the types of pressures alluded to by Shrimsley whereby major companies such as Sainsbury’s, Tesco’s or Amazon have struggled to keep shelves stocked and orders fulfilled, the UUP proposes that there should be ‘UK legislation to ensure companies have a duty to ensure equality of provision to all regions of the UK’ (UUP, Citation2022). As with the DUP, the B/GFA seems to be the key negotiating point: ‘As it stands the Protocol does not protect the Belfast Agreement but instead damages its fine balance creating divisions and frictions’.

Concern with and promotion of instability and distrust are the building blocks of Sinn Féin’s Protocol strategy. Thus, the party’s 2022 manifesto complains that ‘[a]fter more than a decade of the DUP in the Economy Department, the North continues to have the lowest wages, lowest economic growth, lowest productivity, and highest economic inactivity on these islands’ (Sinn Féin, Citation2022, p. 10). The Protocol itself is presented as an ‘opportunity for attracting high-end Foreign Direct Investment; developing new – and expanding existing – local businesses creating [sic] good quality jobs and modernising the economy’ (Sinn Féin, Citation2022). The Protocol is, therefore, a positive outcome of Brexit and is represented as strengthening the case for an all-Ireland economy – though the party’s proposal to extend the Wild Atlantic Way, Ireland’s Ancient East and Ireland’s Hidden Heartlands tourism models to Northern Ireland seems to be a deliberately cynical reading of the opportunities opened by Brexit. For Sinn Féin, the Protocol forms part of the banking strategy: it is a concession that can be deposited and from which withdrawals can be made until its utility runs out. The partitionist implications of the Protocol – namely, that it could in theory and practice result in the type of exercising of unilateral decision-making by the British executive that some unionists and Brexit hardliners might hope for – are deferred in favour of framing it within that opportunistic vision. This is perhaps why discussion of the Protocol sits under the headline ‘Economy’ and forms one page of the 20-page document.

The SDLP’s framing of the Protocol is of a piece with Sinn Féin: for instance, it provides ‘the opportunity to overhaul our unacceptable underperformance’ (SDLP, Citation2022, p. 28). Again, the vision is firmly island of Ireland in focus: thus, the Protocol is represented as the inevitable result of ‘hard Brexit’, but is necessary to offer ‘essential protections’ to Ireland as a whole. Although the SDLP and the Irish government were instrumental in establishing a series of civil society initiatives to discuss Brexit, dating from 2016 (see McGrattan, Citation2023), the party’s manifesto desires to do more: ‘We want to maximise the potential from NI’s position and create structures to ensure that as many stakeholders as possible are having their voices heard’ (SDLP, Citation2022, p. 31). What these structures might look like, how they might sit within the framework of institutions established by the B/GFA, and how they might ameliorate or exacerbate tensions within unionism are not clarified. However, as with Sinn Féin, the SDLP does envisage a renewed economic and tourism potential under the Protocol. For instance, the SDLP manifesto calls for a ‘fundamentally reformed Invest NI, with a new mandate to improve regional imbalances and maximise the economic potential of NI’s dual market access under the Protocol’ (SDLP, Citation2022, p. 29). Arguably, the SDLP takes a step closer to accommodating unionist sympathies: whereas Sinn Féin use ‘the North’ as a proxy for Northern Ireland, implying that the state is essentially part of the island of Ireland, the SDLP evidently use the abbreviation – although a pedant might point out that since the development agency is actually called Invest Northern Ireland, the SDLP’s language choice leave it rather perched uneasily on the fence between nationalist and unionist grammar.

The Alliance Party’s 2022 manifesto is something of a masterclass in fence-sitting. Having voted against the Protocol in the House of Commons, the manifesto stresses that the Protocol is ‘not perfect’ (Alliance, Citation2022, p. 86). It continues, ‘while the Protocol is imperfect, in the absence of any viable alternative, the only course of action is to try and make it work’ (Alliance, Citation2022). Despite, or perhaps because of this, the Alliance manifesto is slightly more detailed in terms of how it would like to see the Protocol working than the others (the document itself runs to 94 pages). The party bemoans the lack of local democratic input and suggests that EU proposals to develop a ‘super-consultation exercise’ on that do not ‘go far enough’ (Alliance, Citation2022, p. 86). Instead, it ‘advocates a structure to give Northern Ireland elected representatives a direct consultative input at the initiation stage of policy development’ (Alliance, Citation2022). This idea is not explained and, given that, unionist elected representatives are currently opposed to the Protocol itself, it is difficult to see it becoming a reality at this point.

From distrust to mistrust

For Rosanvallon, a lack of trust in politicians is a prerequisite of modern democracy – it is the negative image of the decision-making, routinised politics that is typically the stuff of political science. As alluded to above, Rosanvallon (Citation2008) points out that in liberal democratic theory, a suspicion of elites tends to be articulated by a concern with checks and balances; but it is also present in civil society organisations and social movements exerting pressure on leaders to keep their promises. ‘Distrust’, he argues, ‘is a constitutive rather than a recent feature of democratic life’ (Rosanvallon, Citation2006, p. 237). He does not distinguish in the idiomatic differences between mistrust and distrust and he uses the terms interchangeably. This is, arguably, due to his underlying definition of trust: it ‘is what allows us to count on someone’, he writes, it ‘depends on having sufficient knowledge of another person to be able to take for granted his [sic] ability to pursue an objective, his sincerity, and his devotion to the common good’ (Rosanvallon, Citation2018, p. 222).

He suggests that the focus on the decline of electoral politics as a key measure of legitimacy is a by-product of what he terms the ‘decentering of democracy’ (Rosanvallon, Citation2011, p. 7). The response to mistrust, then, involves a repoliticization of democracy that takes seriously the shift in the popular perception of what constitutes the state. In practice, this would seem to require, in the first instance, a focus on how mistrust means different things for different groups, at different times and in different levels of intensity. As Mark Bevir explains, an emphasis on decentred theory ‘draws attention to the fact that in order to explain how external factors can influence changes in networks and governance, social scientists have to understand the ways in which the relevant actors themselves understand those factors’ (Bevir, Citation2013, p. 30). Yet, arguably, Rosanvallon’s critique stops at this point – namely, the role of the state as the key repository of power and resources in being able to influence the articulation of mistrust. His lens remains focused on liberal democratic states and does not quite speak to the problems of deeply divided societies where the state itself is the primary point of contention.

That remains the fundamental issue in an ethnically segregated society such as Northern Ireland, where the ethno-national conflict revolves around the dis/articulation of the Northern Irish polity. That polity has been subject to an analysis through the lens of a relational state – primarily drawing on Poulantzas’s conception of the state being a condensation of class relations, filtered through the dynamics of ethno-religious calculations (Bew et al., Citation2002; McGrattan, Citation2012). The author of one of those analyses, the historian Paul Bew (Citation1998) suggested at the time it was signed that the B/GFA was basically a partitionist document – the PIRA’s campaign had not overthrown the British army or even brought the polity close to economic or financial collapse; nationalists had seen their preferred option of Britain becoming a ‘persuader’ for Irish unity decisively substituted in favour of the aforementioned principle of consent; and, in the Irish Republic, a vast majority had, through a referendum, voted to amend the irredentist constitution and thus give de jure recognition to the border. Yet the headline of ‘The Unionists have won, they just don’t know it’ seemingly implied the coda: ‘The nationalists have lost, they just can’t admit it’. While Bew’s intention was perhaps to focus on the pro-Agreement unionist gains, even at the time nationalists were framing the accord in transitional terms. Martin McGuinness of Sinn Féin, for example, evoked the words of the 1920s republican leader Michael Collins, by describing the Agreement as a ‘stepping stone’. Thus, although the Union was legitimised in the legal agreement between the two sovereign governments, nationalists came to terms with their historic defeat by transcending the Northern Irish state through the historically embedded recourse to on the one hand, the belief in the inevitability of Irish unity, and, on the other, the cultural hollowing out of Britishness and unionist identity (McGrattan, Citation2010).

Certainly, mistrust never went away in Northern Ireland – segregated housing, schooling, sporting and cultural activities remained characteristic features of the society – but the promise of the B/GFA was to try to work that mistrust into a distrust through the conduits of, in the first instance, power-sharing. The Assembly, for instance, was never held in high regard by the Protestant/Unionist community: for instance, in 2003, the fifth anniversary of the B/GFA, not even a third of Protestants (29 per cent) said they would be sorry to see it collapse (11 per cent said they would be pleased and 56 per cent were not bothered either way).Footnote8 Ten years later, in 2013, just under half of Protestants expressed dissatisfaction with the Assembly (49 per cent) while just under a third (30 per cent) were neutral on its performance. Interestingly, at that same point – a decade ago – 46 per cent of Catholics said that they were strong nationalists compared to 43 per cent who felt that they were not strong nationalists (68 per cent of Protestants said that they were strong unionists compared to 32 per cent who considered themselves to be not strong unionists). Another five years later – and a year and a half after the Brexit referendum, the intensity of ethnic attachment had declined for nationalists: 61 per cent said they were either fairly or very strong nationalists, compared with 38 per cent who said they were not very strong (unionist figures also slightly declined – 64 per cent were strong or fairly strong unionists and 33 per cent not very strong).

Elections and survey data demonstrate a high degree of consistency across the past quarter century. Although both nationalist and unionist voters abandoned the moderate parties very quickly after the B/GFA (the DUP and Sinn Féin becoming the dominant ethnic tribunes by 2003), the depth of sentiment remained relatively constant. Although survey data is open to debate – Northern Ireland has always experienced differing results based on whether questions are put face-to-face, by telephone or post, or via email – the Protocol has placed reunification firmly back on the political agenda. Even then, however, the most recent (at the time of writing) evidence (from December 2022) suggests that the Catholic/nationalist community is much less exercised than the Protestant/unionist one: Although 55 per cent of Catholics would vote for unification with the Republic (compared with 21 per cent preferring to stay in the UK), only 4 per cent of Protestants would vote to end partition and 79 per cent would opt to remain in the UK (Leahy, Citation2022). Importantly, although 77 per cent of Catholics would ‘happily accept’ a united Ireland, following a referendum, 52 per cent claim that they could ‘live with it’ if that referendum resulted in a remain outcome. Critically, perhaps, almost a third of Protestants say that a united Ireland result would be ‘[a]lmost impossible to accept’ (41 per cent could ‘live with it’, while 92 per cent would happily remain in the UK) – only 4 per cent of Catholics say that they would find staying in the UK impossible to accept. The survey found that, overall, 50 per cent of people would vote to remain in the UK and 27 per cent to unify with the Republic – swing voters (‘don’t knows’ (18 per cent) and the non-voters (only 5 per cent)) evidently holding sway in any potential referendum.

Conclusions

To extend the metaphor – the Protocol tilts the political discourse and the political dispensation from managed and relatively stable distrust towards unpredictable mistrust. It does so by working to bring questions of ethnic and constitutional interpretation more sharply into focus than they have been since 1998. This is occurring because it pushes party politics and ideological division away from the quotidian issues of peace-building and policy direction towards the question of the constitutional shape of the province.

As I have tried to survey, the responses of political leaders such as the UUP’s Doug Beattie, the parties themselves in their manifestos, and even former governmental officials, are all illustrative of the cul de sac of political thought that the Protocol represents or imposes upon Northern Irish politics. In this changed political context, the political parties’ manifestoes reveal a tendency to revert-to-type. This is unsurprising given that the Protocol has rationalised debate both in the sense of simplifying arguments and of reducing options. As such, the Protocol has helped to bring voters closer to the parties – admittedly, this is not a huge achievement in a polity where, until the failure of the SDLP to gain enough seats in May 2022, the governing parties are always returned to the Executive, but it does mean an institutionalisation of debate into political parties and the exclusion of alternative and non-aligned voices. However, the Protocol has also unmoored the consociational system of organised distrust that has existed for 25 years in that even when the Assembly was not sitting (which constituted around 40 per cent of its history) (Pivotal, Citation2022) it was still seen as the main forum for politics. The DUP leader, Jeffery Donaldson’s decamping from the Assembly to Westminster after the failure of the DUP to remain the largest party (and to be entitled to the First Minister post) is, perhaps, indicative of how party strategists value devolution.

Outwith those manoeuvrings, the Protocol has fundamentally reshaped the structuring of politics in that it has substituted the system that filtered uncertainty into organised distrust with a polarising debate based around an existential mistrust. The Maddisonian proceduralism and institutionalism has been substituted by a Hobbesian calculation where one community’s gain means the other’s loss. The implications of that displacement are still being worked out, but as they are, the problem might be that the fears and suspicions of the Hobbesian dispensation may be aggregative and the interpretation of the incommensurable variables might mean that the starting point of 1998 will prove beyond reach for a considerable period – if ever.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Cillian McGrattan

Cillian McGrattan lectures in Politics.

Notes

1 For the most recent and comprehensive analysis of the political history of contemporary Northern Ireland see O’Kane (Citation2021).

2 A recent poll of unionist voters indicated that 49% though devolution should not recommence until the Protocol is completely removed; a further 31% thought that it should only recommence following ‘significant changes’ to the Protocol; see Breen, Citation2022.

3 Beattie, who is an elected Member of the Northern Ireland Assembly (MLA), was also depicted on posters as a Lundy (a historically hated traitor for unionists) with a double-noose around his neck. Beattie, whose storied military career including guarding Rudolph Hess in Spandau Prison and tours serving in Kosovo, Bosnia and Iraq condemned the attacks by comparing his military colleagues with ‘A minority shout the loudest and make a lot of noise as they seek to raise temperatures and create instability in Northern Ireland’; see Newsletter (Citation2022).

4 For a more precise breakdown of these results see Garry et al. (Citation2022).

5 Precisely, this is 53 versus 37 MLAs out of 90. The June 2016 result was 44% leave and 56% remain.

6 The opinion poll work by David Phinnemore and Katy Hayward at Queen’s University, Belfast (QUB, Citation2022) indicates that the Protocol continues to be firmly within the Northern Irish Overton Window: Only a minority of people have no opinion and a strong majority (consistently over 70% have strong opinions) and it remains a key predictive variable regarding how people will vote.

7 McCormick’s assertion that the Protocol ‘does have the consent of a simple majority both of the electorate in Northern Ireland and the Assembly’ (Citation2022, p. 6) is accurate, but it ignores the problem that the principle of consent speaks to the idea that change must have the approval of each of the main ethno-religious blocs.

8 These and the following statistics are taken from the Northern Ireland Life and Times Survey, which is overseen by both universities in the North; see https://www.ark.ac.uk/ARK/nilt; accessed on 1 January 2023.

9 Wikipedia, ‘Politics of Northern Ireland’. Available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Politics_of_Northern_Ireland#/media/File:NI_Assembly_seat_share_by_designation.svg; accessed 12 May 2022.

10 This is taken from Anna Leach, Niels de Hoog, Seán Clarke and Lucy Swan, ‘Northern Ireland election 2022 live results: assembly seats and votes’, Guardian, 6 May 2022. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/ng-interactive/2022/may/06/northern-ireland-election-2022-live-results-assembly-seats-and-votes; accessed on 12 May 2022.

11 This is from Anna Leach, Niels de Hoog, Seán Clarke and Lucy Swan, ‘Northern Ireland election 2022 live results: assembly seats and votes’, Guardian, 6 May 2022. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/ng-interactive/2022/may/06/northern-ireland-election-2022-live-results-assembly-seats-and-votes; accessed on 12 May 2022.

References

- Alliance. (2022). Alliance party assembly manifesto 2022. Retrieved February 3, 2023, from https://assets.nationbuilder.com/allianceparty/pages/8261/attachments/original/1650982037/AllianceManifestoAE22.pdf?1650982037

- BBC. (2022, March 28). NI protocol: Doug Beattie’s office attack ‘inevitable consequence’. BBC Online. Retrieved April 25, 2022, from https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-60896330

- Bevir, M. (2013). A theory of governance. University of California Press.

- Bew, P. (1998, May 17). The Unionists have won, they just don’t know it. Sunday Times (london, England.

- Bew, P., Gibbon, P., & Patterson, H. (2002). Northern Ireland 1921 - 2001: Political power and social classes. Serif.

- Breen, S. (2022, November 4). LucidTalk poll: DUP claws back support but Sinn Fein still top party. Belfast Telegraph. Retrieved December 31, 2022, from https://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/news/politics/lucidtalk-poll-dup-claws-back-support-but-sinn-fein-still-top-party-42138038.html

- DUP. (2022). Democratic Unionist Party: Assembly Election Manifesto 2022. Retrieved April 29, 2022, from https://s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/my-dup/029311-DUP-Manifesto.pdf

- Edwards, A., & McGrattan, C. (2012). The Northern Ireland conflict. Oneworld.

- Feeney, B. (2022, March 9). Ukraine means it’s all over for the protocol. Irish News. Retrieved Janaury 2, 2023, from https://www.irishnews.com/paywall/tsb/irishnews/irishnews/irishnews/opinion/columnists/2022/03/09/news/brian-feeney-ukraine-war-means-it-s-all-over-for-the-protocol-protests-2608606/content.html

- Garry, J., O’Leary, B., & Pow, J. (2022, May 11). Much more than meh: The 2022 Northern Ireland Assembly elections. LSE Blogs. Retrieved May 12, 2022, from https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/2022-northern-ireland-assembly-elections/

- HMG. (2021). Northern Ireland protocol: The way forward, July 2021, Command Paper 502. Retrieved February 3, 223, from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1008451/CCS207_CCS0721914902-005_Northern_Ireland_Protocol_Web_Accessible__1_.pdf

- Leahy, P. (2022, December 3). North and South methodology: How we took the pulse of Ireland on unity. Irish Times. Retrieved January 1, 2023, from https://www.irishtimes.com/politics/2022/12/03/taking-the-pulse-of-ireland-north-and-south/

- Lowry, B. (2022, April 9). Even if Article 16 is not triggered London knows that the Northern Ireland Protocol is a huge problem. Newsletter. Retrieved February 3, 2023, from https://www.newsletter.co.uk/news/opinion/columnists/ben-lowry-even-if-article-16-is-not-triggered-london-knows-that-the-northern-ireland-Protocol-is-a-huge-problem-3647833

- McClements, F. (2022, February 3). Paul Givan resigns as First Minister of Northern Ireland in DUP Protocol protest. Irish Times. Retrieved April 25, 2022, from https://www.irishtimes.com/news/politics/paul-givan-resigns-as-first-minister-of-northern-ireland-in-dup-Protocol-protest-1.4792735

- McCormick, A. (2022, April). The Belfast/Good Friday Agreement and Brexit: A Briefing Note’ (The Constitution Unit). Retrieved April 28, 2022, from https://consoc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/GFA-and-Brexit-Andrew-McCormick-.pdf

- McGarry, J., & O’Leary, B. (1993). Introduction: The macro-political regulation of ethnic conflict. In J. McGarry, & B. O’Leary (Eds.), The politics of ethnic conflict regulation: Case studies of protracted ethnic conflicts (pp. 1-40). Routledge.

- McGrattan, C. (2010). Northern Ireland, 1968-2008: The politics of entrenchment. Palgrave Macmillan.

- McGrattan, C. (2012). Memory, politics and identity: Haunted by history. Palgrave Macmillan.

- McGrattan, C. (2023). Alienation and destabilization: Northern Ireland in the age of Brexit. In M. Beech, & S. Lee (Eds.), Conservative governments in the age of Brexit (pp. 311-330). Palgrave Macmillan.

- McKittrick, D., Kelters, S., Feeney, B., & Thornton, C. (1999). Lost lives the stories of the men, women and children who died as a result of the Northern Ireland troubles. Mainstream.

- Meagher, K. (2022, April 11). Yes, Irish unity is inevitable. Retrieved January 2, 2023, from https://belfastmedia.com/kevin-meagher-yes-irish-unity-is-inevitable

- Newsletter. (2022, April 9). Those calling me a traitor are not the people I stood beside in battle, says Doug Beattie, Newsletter. Retrieved February 3, 2023, from https://www.newsletter.co.uk/news/politics/those-calling-me-a-traitor-to-my-country-are-not-the-people-i-stood-beside-in-battle-says-doug-beattie-3648049

- NIO. (1998). The Belfast agreement: An agreement reached at the multi-party talks on Northern Ireland, Northern Ireland Office. Retrieved February 8, 2023, from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1034123/The_Belfast_Agreement_An_Agreement_Reached_at_the_Multi-Party_Talks_on_Northern_Ireland.pdf

- O’Doherty, M. (2022, May 9). A non-sectarian future for Northern Ireland needs political middle grounds to assemble. Belfast Telegraph. Retrieved May 12, 2022, from https://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/opinion/columnists/malachi-odoherty/a-non-sectarian-future-for-northern-ireland-needs-political-middle-grounds-to-assemble-41632693.html

- O’Kane, E. (2021). The Northern Ireland peace process: From armed conflict to Brexit. Manchester University Press.

- O’Leary, B. (2005). Mission accomplished? Looking back at the IRA. Field Day Review, 1, 217–246.

- Paul Dixon, P. (2002). Political skills or lying and manipulation? The choreography of the Northern Ireland Peace Process. Political Studies, 50(4), 725–741. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.00004

- Pivotal. (2022, September). Pivotal briefing, ‘governing Northern Ireland without an executive’. Retrieved January 1, 2023, from https://www.pivotalppf.org/cmsfiles/Publications/20220901-Pivotal-briefing-Governing-Northern-Ireland-without-an-Executive.pdf

- QUB [Queen’s University, Belfast]. (2022). Post-Brexit Governance NI. Retrieved December 31, 2022, from https://www.qub.ac.uk/sites/post-brexit-governance-ni/

- Rosanvallon, P. (2006). Democracy past and future. Samuel Moyn (Ed.). Columbia University Press.

- Rosanvallon, P. (2008). Counter-democracy: Politics in an age of distrust (A. Goldhammer 2006, Trans.). Cambridge University Press.

- Rosanvallon, P. (2011). Democratic legitimacy: Impartiality, reflexivity, proximity. (A. Goldhammer :2008, Trans.). Princeton University Press.

- Rosanvallon, P. (2018). Good government: Democracy beyond elections. (M. DeBevoise 2015, Trans.). Harvard University Press.

- SDLP. (2022). Social Democratic and Labour Party: Manifesto 2022. Retrieved February 3, 2023, from https://www.sdlp.ie/manifesto

- Shrimsley, R. (2022, April 28). Self-serving leaders block N Ireland’s path. Financial Times, 21.

- Sinn Fein. (2022). Sinn Féin, Assembly Election 2022: Sinn Féin Manifesto. Retrieved February 3, 2023, from https://vote.sinnfein.ie/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/A4_MANIFESTOenglish.pdf

- The Economist. (2022, November 5). ‘Donaldson’s dilemma’, 30.

- UUP. (2022). Ulster Unionist Party: Northern Ireland Assembly Election 2022 Manifesto’. Retrieved April 29, 2022, from https://assets.nationbuilder.com/uup/pages/40/attachments/original/1649258439/UUP_Manifesto_2022-_web.pdf?1649258439