ABSTRACT

While the meaningful physical education approach serves as a unifying and focused framework for both physical education teachers and teacher educators, it is focused on teaching physical education and not how teacher educators can teach pre-service teachers (PSTs) how to teach using meaningful physical education. Consequently, Learning about Meaningful Physical Education (LAMPE) has emerged as a comprehensive pedagogical approach designed to support teacher educators in their decision making to educate PSTs about meaningful physical education. However more work is needed to exemplify PETE practices when enacting the LAMPE pedagogical principles and explain their effectiveness in preparing PSTs to learn about meaningful physical education. This research aims to address the knowledge gap in answering: What are the realities of enacting principle four of the LAMPE principles (i.e. Teacher educators should frame learning activities using features of meaningful participation) in PETE? Rather than providing the already agreed critical features of meaningful physical education (i.e. social interaction, challenge, motor competence, fun, and personally relevant learning), and reproducing what is already known, Dylan engaged in a self-study of teacher education practices (S-STEP) methodology to inductively co-construct a shared language with his PSTs. Data was collected through different sources: (i) Four community of learners meetings; (ii) 11 reflective journal entries; (iii) Critical friends interrogation on such reflections; and (iv) the teaching artefacts. Through data analysis, three categories were constructed: (1) Inductive disruption encouraging co-construction of meaningful physical education features; (2) Tensions in developing a shared language through identification, exploration, experience, and reflection; (3) An uncomfortable space of ‘knowing’ and ‘not knowing’. The inductive analysis led us to make connections to Biesta, G.’s [2014. The Beautiful Risk of Education. Paradigm Publishers] notion of ‘weak education’. Informed by this, this research advocates for ‘weak practice’, the development of a pedagogy of teacher education, and a principle zero.

Introduction

Physical education teachers and teacher educators have long sought how to make the subject more meaningful, leading to the emergence of different conceptions of meaning and meaningfulness within physical education over time (e.g. Arnold, Citation1979; Kretchmar, Citation2006). However, due to the complex nature of these concepts, it has been a challenge for the field to translate meaningfulness into practice in both the school context and teacher education (Beni et al., Citation2017). Increased interest in meaningfulness within the subject has given rise to the pedagogical approach ‘meaningful physical education’. Meaningful physical education (Beni et al., Citation2017) serves as a framework for intentional pedagogical decision making within physical education that prioritises pupils’ experiences of meaningfulness (Fletcher et al., Citation2021).

It is in this space of meaningful physical education where this research lies, particularly in the teaching of such to pre-service teachers (PSTs) in physical education teacher education (PETE). Granted this is an area of growing interest in the field, a large international community of learners was constructed to explore how we – as teacher educators – can teach about the teaching and learning of meaningful physical education in PETE. Within that larger community of learners, micro communities of four teacher educators existed. We (the authorship team) are one micro community, and we explored this matter through Dylan’s teaching practice guided by the broad purpose of exploring the realities of teaching PSTs about the teaching and learning of meaningful physical education in PETE.

Meaningful physical education

Meaningful physical education is informed by Kretchmar’s (Citation2007) definition that meaningful experiences are those which are personally significant to the individual. There are four essential components which underpinned the meaningful physical education framework: vision (Ní Chróinín et al., Citation2019), shared language (Fletcher et al., Citation2020), democratic practices, and reflective practices (Fletcher & Ní Chróinín, Citation2022). Guided by Kretchmar’s (Citation2006) criteria for meaningfulness, Beni et al.’s (Citation2017) review of the academic literature found evidence for the following critical features of meaningful physical education and youth sport: (i) positive social interaction; (ii) optimal level of challenge; (iii) motor competence; (iv) fun; and (v) personally relevant learning. It is these that form an initial basis of a shared language to develop and inform ongoing reflection within meaningful physical education (Fletcher et al., Citation2020). The meaningful physical education framework allows teachers to select and apply a range of teaching approaches to enhance meaningfulness within the subject but prioritises reflective and democratic practices (Fletcher & Ní Chróinín, Citation2022). In that, democratic practices provide a sense of ownership for the learners, whilst reflection allows them to evaluate their experiences. Democratic practices range from simply as allowing pupils choice in who they play with (Cardiff et al., Citation2023) to more complex actions such as negotiating the implementation of the physical education curriculum with pupils (Howley & Tannehill, Citation2014). By having pupils contribute to individual and collective decision making within the subject, it can foster inclusivity and meaningfulness (Fletcher & Ní Chróinín, Citation2022; Ní Chróinín, Fletcher & Griffin, Citation2018). Reflective activities are a core part of meaningful physical education as they assist pupils to ‘become aware of, evaluate, and attach personal significance to physical education experiences’ (Fletcher & Ní Chróinín, Citation2022, p. 7). These activities include goal setting, reflection on likes and dislikes, and progress and making sense of the experiences in physical education within the context of children’s own lives (Ní Chróinín et al., Citation2023; Smith et al., Citation2023). The shared language, democratic, and reflective practices collectively form the basis for teachers and teacher educators to develop an individual and collective vision for meaningful physical education and teacher education.

Meaningful physical education in PETE

While the meaningful physical education approach serves as a unifying and focused framework for both physical education teachers and teacher educators (Fletcher et al., Citation2021), it is focused on teaching physical education and not how teacher educators can teach PSTs how to teach using meaningful physical education. Consequently, Learning about Meaningful Physical Education (LAMPE) has emerged as a comprehensive pedagogical approach designed to support teacher educators in their decision making to educate PSTs about meaningful physical education (Ní Chróinín, Fletcher & O’Sullivan, Citation2018). Data collection over five years from teacher educator programmes in Ireland and Canada focused on understanding PSTs’ comprehension of teaching physical education through the lens of meaningful physical education. This analysis led to the identification of five pedagogical principles for teacher educators to support PSTs in facilitating meaningful physical education experiences (Ní Chróinín, Fletcher & O’Sullivan, Citation2018). These principles are outlined in . To note, the numbering here is not indicative of priority.

Table 1. LAMPE pedagogical principles adapted Fletcher et al. (Citation2021).

The LAMPE principles function as a versatile tool that can be applied to enhance specific components of a PETE programme, including individual learning activities, the content of sessions or whole modules. Alternatively, it can serve as the foundational cornerstone upon which the entirety of the programme’s curriculum design is constructed (Ní Chróinín et al., Citation2019). Distinctively, the LAMPE approach within PETE explicitly underscores the promotion of meaningful experiences within the context of school-based physical education. Unlike other approaches, LAMPE articulates, models, and explicitly emphasises the significance of meaningful physical education experiences, serving as the paramount criterion for guiding decision-making processes in support of PST learning. LAMPE’s priority is about equipping PSTs with the skills and knowledge required to effectively teach and facilitate physical education lessons that bear personal significance for the children in their respective classes (e.g. Beni et al., Citation2017; Coulter et al., Citation2021; Fletcher et al., Citation2021; Gleddie & Harding-Kuriger, Citation2021). However, as Ní Chróinín, Fletcher & O’Sullivan (Citation2018) suggest, more work is needed to exemplify PETE practices when enacting the LAMPE pedagogical principles and provide evidence of their effectiveness in preparing PST to learn about meaningful physical education. To emphasise the (interconnected) distinction here, meaningful physical education is an approach to the teaching of physical education while LAMPE is an approach to teaching PSTs in PETE about the teaching and learning of meaningful physical education.

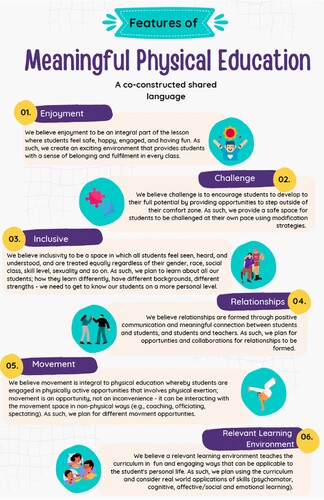

This research aims to address the knowledge gap suggested by Ní Chróinín et al. (Citation2018). Dylan, as the teacher educator delving into the LAMPE principles, chose principle four (i.e. Teacher educators should frame learning activities using features of meaningful participation) as a starting point. He believed that constructing a shared language around the features of meaningful physical education could serve as a catalyst for understanding the other features. Rather than providing PSTs with a list of the already agreed upon critical features of meaningful physical education (i.e. social interaction, challenge, motor competence, fun, and personally relevant learning), and reproducing what is already known, Dylan opted to embrace the challenge from Ní Chróinín et al. (Citation2018). In doing so, he opted to experiment with the principles of LAMPE within his own context as a teacher educator. This approach was chosen as it was felt the established features may constrain the possibilities of alternative features – we further discuss this rationale in findings. The following research question was constructed: What are the realities of enacting the principle four of LAMPE principles in PETE?

Theoretical framework

The question of education, as Biesta puts it, is whether we are prepared to take the risk of life, with all its uncertainty, unpredictability and frustration or whether we prefer to see a certainty beyond or subtending life, on the level of metaphysics. The choice between what he calls a strong and a weak way of education. The strong way offers security, predictability, and freedom from risk. The weak way, by contrast, is slow, difficult, and by no means certain in its results, if indeed we can speak of ‘results’ at all. We live in an age when politicians, policy makers and the public are vociferous in their demands that education should be strong. Weakness is perceived as a problem. Biesta’s contention, to the contrary, is that if we take the weakness out of education, we are in danger of taking out education altogether. (Ingold, Citation2017, p. 32–33)

The theoretical approach is based on Dutch education philosopher Gert Biesta’s concepts of ‘weak education’ and ‘risk’. With regards to education, Biesta (Citation2014) states we have two choices, the strong way, or the weak way. The strong way of education is about reducing risk in what is being taught and how it is being taught. This provides the teacher the predictability of a starting point and an end point, with certainty of obtaining the desired outcomes. The weak way is a dialogical approach through ‘communication and interpretation, of interruption and response [which is] … informed by concern for those we educate to be subjects of their own actions’ (Biesta, Citation2014, p. 4). The weak way is slower and more difficult as there is no certainty of pre-planned outcomes, which is considered a problem in our risk averse society and education system.

Biesta’s (Citation2014) concept of risk is fundamental if both teachers and teacher educators are to embrace and enact contemporary pedagogical practices. As Mattsson and Larsson (Citation2021) state in their study of how physical education teachers approached the issue of teaching expressive dance, risk is not about a teacher failing to help a student to learn but is about letting go of prescribed outcomes to be more open and responsive to what emerges within their interaction with students. This is echoed by Lindberg and Mattsson (Citation2022) who highlight the risk involved in seeking out and merging students’ own ideas and concepts into the classroom. It is not for the teacher to make the learning situation easy to make both themselves and the student’s content, instead it is to welcome challenging conversations and difficult questions which may lead the direction of travel to inconvenient places (Lindberg & Mattsson, Citation2022). Whilst Biesta’s (Citation2014) writing is focused on teaching and learning within a school setting, the same argument about weak education and risk can be made for teacher education and the preparation of PSTs. This paper delves into the role and practices of Dylan in expanding PSTs’ language of and understanding about meaningfulness. Biesta’s (Citation2014) concept of risk is central to this self-study which focuses on the the enactment of the fourth LAMPE principle – ‘Teacher educators should frame learning activities using features of meaningful participation’ – co-creating a shared language through an inductive approach.

Methodology

Self-study, participants, and context

This research adopted a self-study of teacher education practices (S-STEP) methodology which aims to explore and understand the ‘self’ in ‘practice’ for personal and professional growth (Ovens & Fletcher, Citation2014). In addition to a desire to improve understanding of the ‘self’ in and alongside ‘practice’, SSTEP was chosen as a methodology to provide guidance and pedagogical considerations to other teacher educators who wish to enhance their practice (Casey & Fletcher, Citation2012). Guided by LaBoskey’s (Citation2004) quality criteria, this research adhered to the five key characteristics of S-STEP research. First, the research was self-initiated and focused within a large international S-STEP community of learners. Our decision was to engage with the LAMPE principles, with a specific emphasis on Dylan’s inductive approach to teaching PSTs about the features of meaningful physical education. We emphasise the S-STEP nature of this research as we explored the self in practice as the self was fore fronted – while this is threaded throughout the findings (in balance in practice), it is emphasised in category 3. Second, the research was improvement-orientated, aiming to enhance Dylan’s teaching practice and deepen our collective understanding regarding the teaching of PSTs about meaningful physical education. Third, we adopted an interactive approach, involving both written and oral communication formats within a community of learners, aligning with recommendations from scholars such as Carse et al. (Citation2022). Fourth, we employed multiple qualitative methods, ensuring a rich exploration of our experiences and practices, with a specific focus on Dylan’s self-in-practice. Finally, the research employed an exemplar-based validation approach, grounded in trustworthiness (Bowles et al., Citation2023). By offering insights into the research and teaching processes, readers are allowed access to the quality of these processes and contemplate how they might adapt the practices and understandings to their specific contexts.

The four teacher educators – we – teach four different PETE programmes in three countries (Australia, Norway, and England). We range in teaching experience, and all have an interest in meaningful physical education. For this research, Dylan was the teacher educator whose teaching practice was explored while Alex, Mats, and Jordan acted as critical friends. The critical friends role was to: (i) meet Dylan as a group at each macro meeting to question and interrogate practice; (ii) read, comment, and clarify practice on the weekly written reflections; (iii) be available to meet Dylan at any stage if they needed to. A reminder to the reader, that this micro community – i.e. four teacher educators – was one of many in a larger international community of learners.

Dylan taught a first-year module (i.e. Health and Physical Education Studies) in a four-year undergraduate degree (i.e. Bachelor in Health and Physical Education). This module is foundational whereby the PSTs are introduced to pedagogy, assessment, and curriculum. The Unit Learning Outcomes for this unit/module are as follows: (i) Describe past and present notions of effective teaching in health and physical education and critically consider the merits and limitations of an instruction model approach; (ii) Analyse research on how students learn to discuss implications for teaching; (iii) Critically reflect on their mentoring experience as professional learning for implications for improved student learning; (iv) Use effective student focussed teaching/assessment strategies to effectively sequence learning experiences for student learning in a health and/or physical education context; (v) Apply knowledge of curriculum, assessment, a range of resources that enhance engagement in student learning (including ICT and digital technologies) in HPE, and knowledge of instructional approaches to plan an instructionally aligned learning sequence; and (vi) Articulate the rationale for continued professional learning for teachers and the implications for improved student learning. Dylan taught the lectures (consisting of 75 PSTs) and the practical classes (two classes divided the 75 PSTs) over an 11-week period (more detail is reported in the first category of the findings). It was this teaching that Dylan reflected on for this S-STEP research. More detail on how Dylan went about engaging PSTs in this work is outlined in category 1 of the findings.

Data collection and analysis

Data was collected through different sources: (i) The community of learners met four times over zoom (pre-, during [twice], post- teaching) and these meetings were recorded and acted as data (these are labelled as macro meetings in the findings – a macro critical friend meeting was when all four teacher educators (authorship team) were in a meeting whereby Dylan discussed their teaching and Alex, Jordan, and Mats questioned, critiqued, and supported Dylan’s practice); (ii) Dylan also reflected weekly through google docs resulting in 11 journal entries; (iii) The critical friends interrogated such reflections through commenting on the reflections which further questioned aspects of the reflection and created more dialogue; and (iv) teaching artefacts (e.g. planning documents, teaching slides, exit tickets, and entry tickets which are questions/prompts given to students which they complete before class as seen in ). All data was analysed using Charmaz’s (Citation2014) approach to data analysis which involves three phases: initial; focused; and theoretical. The written reflections and the critical friends comments were analysed by hand through a traditional coding approach. The recorded critical friend meetings were also analysed in this manner with an added layer of ‘live’ coding (Parameswaran et al., Citation2020). Studies using this approach (e.g. Scanlon, Coulter, Baker, & Tannehill, Citation2024) show how using a ‘live’ coding approach allows ‘for coding of non-verbal content including non-verbal participant agreement, the visual of the participant (and their visible identities), emotion, the emphasis of certain phrases, and other paralinguistic behaviour which offered depth and preserved the voice of the participant’ (Parameswaran et al., Citation2020, pp. 640–641).

Table 2. Week learning experiences in the co-construction of the meaningful physical education features.

All coding was conducted by Dylan, but regular meetings were held to agree, disagree, and come to a consensus before moving to the next coding phases. The first phase of coding was initial coding. Initial codes included, for example, ‘not knowing the features’, ‘trying to be quiet in not sharing the established features’, ‘challenge in starting with a blank slate’, ‘tension in not using established language’, ‘felt uncomfortable’. Once this was done, the initial coding document was shared with Alex, Jordan, and Mats and we met to discuss. The next phase was focused coding whereby the most ‘fruitful’ codes were chosen in a more selective and conceptual manner (Mordal-Moen & Green, Citation2014). This led to the construction of categories and subcategories. For example, and continuing with the above example initial codes, these (and others) were grouped to the focused sub-category: ‘Uncomfortable space as a teacher educator’. Another meeting was held with critical friends whereby we discussed the construction of the categories and subcategories and the processes which lead to such construction. The final phase of coding was theoretical coding whereby, as a group, we discussed and identified theoretical frameworks which best explain the constructed data. This occurred through dialogical processes whereby we met as a group and discussed different theoretical frameworks and how they may best explain the data. Biesta’s work was discussed, and this seemed to best align. We then read their work and the constructed data and came back to another meeting to discuss our thoughts. We came to a consensus on the usefulness of Biesta’s work in explaining the processes of this teaching and learning journey. Continuing with the example shared in this section, Biesta’s work on weak education was chosen as there was a strong theoretical connection between this theory and the constructed findings, e.g. the constructed category three: ‘An uncomfortable space of “knowing” and “not knowing”’. We now share the findings of this data analysis process.

Findings

The following findings are presented in three interrelated categories. To note, in this section, ‘I’ refers to Dylan’s experiences (given he was at the centre of the S-STEP) and ‘we’ refers to whole group statements and understandings. To remind the reader about the used terminology, ‘meaningful physical education’ (which consists of ‘features’) is an approach to the teaching of physical education while LAMPE (which consists of ‘principles’) is an approach to teaching PSTs in PETE about the teaching and learning of meaningful physical education.

| 1. | Inductive disruption encouraging co-construction of meaningful physical education features | ||||

In following an inductive approach, I did not share the established features of meaningful physical education (i.e. social interaction, challenge, personally relevant learning, delight, fun, and motor competence) with the PSTs. Rather, we started with the PSTs’ meaningful experiences of movement outside and within the physical education setting:

I didn’t want to give them the features of meaningful PE, but rather them to come up with what the features of meaningful physical education could be (Dylan – Macro CF Meeting 1)

provides an overview of the weekly tasks related to the co-construction of the meaningful physical education features. The intention of week 1 and 2 was to: ‘start the inductive process of thinking and verbalising features of meaningful movement to lead into meaningful physical education’ (Dylan – Reflective journal on planning). Alex commented on approach:

One of the areas of future research that has been highlighted is that there are potentially other features of meaningful physical education that have not been recognised. Perhaps we provide the ones already in the framework we cut down the chance to be curious about that. Secondly, you are trying to uphold some of the pedagogical principles of meaningful physical education (democratic and reflective) in doing this (Alex – Reflective journal on planning)

I was trying to use some of their words to guide them into what a feature could be so a lot of them were saying learning is definitely a feature and I was saying okay but what about the learning? or … memory is a feature, ‘it was a really good memory’, ‘it brought back happy memories’ that was the feature, [and I would say] ‘well what about the memory, what happened in the memory that made it meaningful to you, what was the significance of the memory?’ and we got down to friends and relationships. So those conversations were difficult to manage because it was so inductive (Dylan – Macro CF Meeting 1)

Alex gave a great idea of moving from ‘purpose statements’ into ‘beliefs into actions’ with two questions: (i) what do you believe the feature to be?; (ii) How might it guide your action? (Reflection on Week 8)

Reflecting on the process, Alex prompted:

You have taught meaningful physical education before … What have been the strengths of doing it this way? And what have been the challenges? (Alex – Macro meeting 3)

The strengths this way are there is definitely more buy-in because when I did it at [previous university] … they understood it but it was kind of ‘obviously that should be the way’ but there was no buy-in to it – it made sense but ‘let’s move on’. I struggled with it because … I always found it [the features] constraining. Now I know [authors of meaningful physical education paper] etc said these are starting points but I think if there is something there, it is very hard to treat it as a starting point because it is already established … so when I was teaching it at [previous university], I found it as this prescribed notion of ‘these are the features that make physical education meaningful’ but there was no buy-in and none from myself as well … [this time] They got to reflect on past experiences which brought them to one point, they got to construct the features which was another point, they got to experience the features, reflect and change – [a process of] experience, reflect, change – and do that process for a couple of weeks and refine them, and then we built the ‘we believe, as such’ statements. So there was huge ownership over what these features are and that really came through (Dylan – Macro meeting 3)

I ended on asking them if they would have preferred if I had given them the established features or we went through the process that we did. From whom answered, they preferred the process we did. Answers included:

- Preferred putting together their own features as the co-constructed features were more relevant, meaningful, accessible, and more implementable

- Some of the established features are vague; ‘fun’ is ‘muddy’: they believed ‘fun’ (established) was captured in ‘enjoyment’ (co-constructed), but ‘enjoyment’ was a much deeper feature than fun

- They spoke to how ‘inclusive’ (co-constructed) was not captured in the established features.

- The established features are broader and the co-constructed are more specific (Reflective journal week 10)

Overall, this inductive approach to co-construction was challenging (this is further discussed in category 3) but did allow for potentialities and possibilities of what meaningful physical education can be. I commented on this,

[this inductive approach] challenged me a lot in my understanding, but now we have a basis to work on – a shared language – for the next 4 years of their degree … it disrupts their thinking of what physical education is; an inductive disruption (Dylan – Macro Meeting 3)

| 2. | Tensions in developing a shared language through identification, exploration, experience, and reflection (and repeat) | ||||

A cyclical approach was taken to the development of the shared language, i.e. the PSTs identified meaningful physical education features (as outlined above), explored these features through entry tickets and in-class tasks, experienced these features by embedding affordances in learning experiences in practical classes, and reflected on these experiences by refining the features. This cyclical approach was repeated over the 11-week teaching period. There were some challenges in this approach. These included: (i) Defining ‘meaningful’ and (ii) Viewing meaningful physical education from a PST lens versus/and a learner lens.

From the very start of the S-STEP, one challenge was: defining ‘meaningful’ to the PSTs. Alex and I reflect,

I actually found it difficult to describe what I meant by ‘meaningful’ in this context. I went with something like ‘think about WHY you like to do this movement, what are the things that contribute to the why’. I am not sure this was the right prompt. If I was doing this again, I would probably spend more time on conceptualising what ‘meaningful’ is and bring the PSTs along on this conceptualisation journey. (Dylan – Reflective journal week 1)

I think part of meaningful physical education is that we want to increase their [PST and students] vocabulary and get some granularity when they are talking about their experiences and that is what you are trying to do with the PSTs. You are not allowing them that first response but trying to dig deeper and get further and further … really rich responses to share (Alex – Macro Meeting 2)

PSTs decided to really interrogate the features and combine and remove based on how they experienced them – I think this is a good finding going forward for principle 4 of the LAMPE principles; the PSTs need to experience the features to see what works and doesn't work (Reflective journal week 5)

Another challenge in this process was: the lens in which the PSTs were viewing, designing, and experiencing the co-constructed meaningful physical education features, i.e. through a PST lens and/or a learner lens. To clarify, when I say ‘PST lens’, I am referring to the PSTs as prospective teachers learning about teaching and learning and when I say ‘learner lens’, I am referring to the PST as learners experiencing what their students in school would experience. This lens was difficult to balance and, interesting, it evolved over the course of the cyclical process. I reflect,

This activity worked pretty well – they took up the perspective of a learner in the first question, but then as a PST in the second question. This is interesting and shows the complexity of this because they are working with two hats as PSTs – learner and PST (i.e. prospective teacher). (Dylan – Reflective journal week 7)

[the established features] are generated from research on children and their perspective and these are adults who are looking to be teachers so maybe that is where the nuances, sophistication and terminology in the language comes from, and maybe that is more helpful for teachers (Alex)

Despite its challenges, the cyclical process of identification, exploration, experience, and reflection enhanced the co-constructed nature of the process as it allowed for deep critical reflection. We strongly advocate for the use of this cyclical process in future co-development of a shared language for meaningful physical education (principle 4 of LAMPE).

| 3. | An uncomfortable space of ‘knowing’ and ‘not knowing’ | ||||

This S-STEP shed light on the uncomfortable space I was in throughout the enactment of the LAMPE principle 4. The uncomfortable space was created by ‘knowing’ the established features and ‘not knowing’ what a feature could be. I reflect on this space,

What I liked about it [the inductive approach] is … my critique of meaningful physical education was that we are constraining ourselves to those features even though it is always explicitly acknowledged that these should be a starting point but I think it is always difficult to move away from something established and that is why I wanted to go with the inductive approach … but it has been super difficult for two reasons, first I always go back to those established features … and second of all, when PSTs saying to me … ’maybe safe is a meaningful feature?’ and I am thinking ‘wait could safe be … ’ and you are in that uncomfortable space where you don’t know the answer and … you have 140 eyes looking straight at me (Dylan – Macro Meeting 1)

[authors of meaningful physical education paper] looked for evidence within the physical education and [youth] sport literature – this was mainly from children and young people. When reflecting back as adults – we may have a broader range of experiences and language to draw upon. Also what we find meaningful as adults might be more sophisticated and richer than when we were children. This might be a factor when adults think about what is meaningful in movement, sport, and physical activity. (Alex – Reflective journal week 2)

Is inclusive a feature of MPE? I don't know, but then again, why can it not be? The established features were constructed in a certain context and maybe the lived experiences of these PSTs are different and are therefore coming up with different features. I am thinking for example, these PSTs have lived through Black Lives Matter and a greater focus on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander inclusion in society in Australia including in schools and physical education so this is possibly a connection to why they believe this should be prevalent? On the other hand, meaningfulness is individual and personally relevant so how does ‘inclusion’ play a role here? My head is sore from thinking!!!! It would be great to get your thoughts here. (Dylan – Reflective journal Week 2)

I certainly think this might play a role – as adults we have a wider understanding of the world, a clearer sense of values and a greater amount of experiences to draw upon, this then of course can influence what we find meaningful. (Alex – Reflective journal Week 2)

I am left wondering: (i) What constitutes a feature of MPE? Where are the boundaries of what can or cannot be a feature of MPE? (Dylan – Reflective journal week 2)

Probably not as clear as we think – and also they are highly interrelated. But the key thing is to provide a safe space to explore, elaborate and share – which you are doing. (Alex– Reflective journal week 2)

A challenge which was threaded throughout this uncomfortable space was the difficulty in not using the language of the established features and how to manage this tension as the ‘knowing’ teacher educator. Alex comments,

A real challenge to construct a shared language when a shared language already exists. Is this one of the reasons why we haven't either refined, challenged, or added to the existing critical features? (Alex – Reflective journal week 2)

Discussion and considerations

This S-STEP research explored one teacher educator’s journey in teaching about the teaching and learning of meaningful physical education in PETE through the enactment of principle four of LAMPE. We decided to start this by co-creating a shared language of meaningful physical education and have shared this process through the findings. In light of this and looking at these findings through our theoretical lens (Biesta, Citation2014), we now talk through three discussion points each followed by some considerations.

First, the notion of ‘weak practice’ and ‘risk’ in education. Biesta (Citation2014) compares education and teaching practice to lighting a fire whereby there is always risk; in ways, this risk is not knowing the outcome of the fire before lighting it. This lack of certainty and pre-planned outcomes in teaching can be considered ‘weak education’. This is in comparison to ‘strong education’ which reduces risk in what / how it is being taught. As captured in the findings, through his inductive approach to co-creating the language, Dylan took ‘risk’ and engaged in ‘weak education’ with the PSTs. The inductive approach to co-creation allowed for a creative process of learning, rather than a transferring of information from teacher educator to PST (Biesta, Citation2014). This ‘risk’ put Dylan in an uncomfortable space of not knowing (i.e. what a feature could be) which espoused a level of vulnerability. Engaging in ‘weak education’, Dylan had to face and negotiated multiple challenges and tensions that he might not have had to if he engaged in ‘strong education’. This process is captured when Dylan shares his experience of teaching meaningful physical education previously through a more teacher-led approach and sharing of information through designated meaningful physical education lectures. Aligning this with the components of ‘strong education’ (Biesta, Citation2014), there was a starting point and an end point which allowed Dylan to go at a certain speed to transfer the information needed on meaningful physical education to his PSTs. This is in comparison to Dylan’s approach in this research. Dylan embraced ‘weak education’ which is much slower and unpredictable. The (unbalanced) power ratios shift to the PSTs in the class and the teacher educator loses control (exemplified by Dylan’s quotes on not knowing). Dylan took ‘risk’ in taking a step back from certainty and gave the PSTs space to identify, explore, experience, and reflect. This cyclical process was a dialogical process between teacher educator and PSTs (Biesta, Citation2014). While Biesta’s (Citation2014) work refers to the school context, we have demonstrated here how it can also apply to the higher education / teacher education context. While Dylan also modelled weak education in ‘not knowing’, there were challenges and contradictions (alongside opportunities for development) in this approach. Dylan was a knowing expert of pedagogy and understood the complexity of such in practice (alongside meaningfulness), but at the same time, Dylan engaged in ‘not knowing’ the direction of learning (e.g. what a feature could be); leading to complex contradictions. Dylan shared some of these contradictions in week 10 () and we strongly suggest this sharing needs to occur. This teacher-student dialogue can provide insight into the why’s and why not’s of our teaching (Loughran, Citation2006) by discussing the pedagogical decision making processes. This is informed by Loughran and Menter’s (Citation2019, p. 218) advice, ‘a teacher educator needs to be able to teach about the practice in ways that highlight the complexity of teaching – not just deliver the declarative knowledge of teaching’. For Dylan, this transformed (and in some ways, cemented) his teaching philosophy on treating PSTs as partners in the teaching and learning process. By moving from teaching agreed declarative knowledge (i.e. the features of meaningful physical education) to a co-constructing knowledge (i.e. a ‘weak’ approach over a strong approach), Dylan developed their expertise as a teacher educator. We strongly encourage other teacher educators to adopt a ‘weak education’ approach to their teaching and embrace ‘risk’ to reap the benefits of the unknown. We also suggest that collecting PST data on their experience of weak education would enhance our understanding of such approach to doing education.

Second, we acknowledge the complexity of teacher education pedagogy and suggest this may need to be further emphasised in the LAMPE conception. In the meaningful physical education framework, as previously stated, there are four essential components: vision, shared language, democratic, and reflective practices (Fletcher & Ní Chróinín, Citation2022; Ní Chróinín et al., Citation2019). In this research, Dylan used all four components to guide his teaching practice. He encouraged PSTs to co-create a vision for meaningful physical education through a process of developing a shared language (and understanding) of the meaningful physical education components through the use of democratic and reflective principles. Dylan explicitly modelled meaningful physical education teaching through this approach and encouraged his PSTs to reflect upon their learner experience as PSTs. In this way, the PSTs were learning about the content of meaningful physical education, learning about learning meaningful physical education, and learning about teaching meaningful physical education through the approach of identification, exploration, experience, and reflection. This aligns with Loughran’s (Citation2006) notion of developing a pedagogy of teacher education. While this research did not set out to develop a pedagogy of teacher education, evidence of developing this is here. Teacher educators, as teachers of teachers, prioritise teaching about teaching and learning about teaching (as both learners and future teachers) (Loughran, Citation2014). We advocate for an acknowledgement of the complexity of teacher education pedagogy in the conceptualisation and enactment of the LAMPE principles. As teachers of teachers, teacher educators have multiple layers to balance in their teaching (as do PSTs – as learners and prospective teachers). This complexity adds multiple dimensions to LAMPE which may not be fully captured in their original conceptualisation. Further to this, we believe Biesta’s (Citation2014) work on ‘weak education’ can contribute to the refinement of the LAMPE principles and the development of a pedagogy of teacher education for meaningful physical education. For example, Biesta’s (Citation2014) concepts of risk and weak education can challenge (and improve) the notion of modelling (i.e. principle 1). Modelling can often refer to a traditional mode of ‘effective’ teaching (with connections related to a level of fidelity), but this research highlighted how modelling weak practice can lead to deeper learning (e.g. PST ownership over learning).

Third, the interconnected nature of the LAMPE principles. While this research focused on the enactment of principle four, throughout the process it became evident that Dylan was drawing on all five principles implicitly and explicitly. As well as explicitly enacting principle four, we can see throughout the findings that Dylan operated in constructive alignment in his approach while also explicitly modelling meaningful physical education practice (principle one) by using, for example, democratic and reflective practices (principle two). Dylan engaged the PSTs in learning experiences that encouraged participation as a learner and prospective teacher (principle three) which required continuous reflection as a learner and a prospective teacher (principle five). For Dylan, focusing on principle four as a starting point encouraged the embedding of the other principles. In looking at the principles as they stand, and considering this research, we are suggesting that the LAMPE principles need to be revisited and refined to focus more explicitly on teacher educator practice, i.e. teaching PSTs about the learning and teaching of meaningful physical education. This needs to be at the forefront if we – teacher educators – are to consider developing a pedagogy of teacher education with regards to meaningful physical education. In addition to this, we believe a ‘principle zero’ needs to be added. A principle zero would be the starting point. Before embarking on this research, Dylan engaged in research which explored meaningful teacher educator practice and therefore gained a deeper insight into the process of making sense of meaningfulness. We believe this would be advantageous to all teacher educators and this is what a principle zero would entail – positionality work on meaningfulness; what does it mean to you? This would provide clarity and understanding around meaningfulness before engaging with the five LAMPE principles which centre around meaningfulness.

A final consideration for the reader is to engage in ‘weak education’ and take ‘risk’ with the support of a critical friend(s) (MacPhail et al., Citation2021). While this was not the main focus of this research, the findings highlight the important of communities of practice and critical friendship, in that, we encouraged and supported Dylan in the processes of risk taking and ‘weak education’. We encourage teacher educators to use Biesta to explore how critical friendship can support these processes. Overall, this research strongly advocates for ‘weak practice’ in teacher educator practice, the development of a pedagogy of teacher education, and an additional principle zero to the LAMPE principles.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Arnold, P. J. (1979). Meaning in movement, sport, and physical education. Heinemann.

- Beni, S., Fletcher, T., & Ní Chróinín, D. (2017). Meaningful experiences in physical education and youth sport: A review of the literature. Quest (Grand Rapids, Mich), 69(3), 291–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2016.1224192

- Biesta, G. (2014). The beautiful risk of education. Paradigm Publishers.

- Bowles, R., Sweeney, T., & Coulter, M. (2023). Using collaborative self-study to support professional learning in initial teacher education: Developing pedagogy through meaningful physical education. European Journal of Teacher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2023.2282369

- Cardiff, G., Ní Chróinín, D., Bowles, R., Fletcher, T., & Beni, S. (2023). ‘Just let them have a say!’ Students’ perspective of student voice pedagogies in primary physical education. Irish Educational Studies, 42(4), 659–676. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2023.2255987

- Carse, N., Jess, M., McMillan, P., & Fletcher, T. (2022). The 'we-me' dynamic in a collaborative self study. In B. M. Butler & S. M. Bullock (Eds.), Learning through collaboration in self-study: Critical friendships, collaborative self-study, and self-study communities of practice (pp. 127–141). Springer.

- Casey, A., & Fletcher, T. (2012). Trading places: From physical education teachers to teacher educators. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 31(4), 362–380.

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory. Sage.

- Coulter, M., Bowles, R., & Sweeney, T. (2021). Learning to teach generalist primary teachers how to prioritize meaningful experiences in physical education. In T. Fletcher, D. N. Chrónín, D. Gleddie, & S. Beni (Eds.), Meaningful physical education (pp. 75–86). Routledge.

- Fletcher, T., Chróinín, D. N., Gleddie, D., & Beni, S. (eds.). (2021). Meaningful physical education: An approach for teaching and learning. Routledge.

- Fletcher, T., Chróinín, D. N., O’Sullivan, M., & Beni, S. (2020). Pre-service teachers articulating their learning about meaningful physical education. European Physical Education Review, 26(4), 885–902. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X19899693

- Fletcher, T., & Ní Chróinín, D. (2022). Pedagogical principles that support the prioritisation of meaningful experiences in physical education: Conceptual and practical considerations. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 27(5), 455–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2021.1884672

- Gleddie, D., & Harding-Kuriger, J. (2021). Teaching teachers about meaningful physical education in a northern Canadian setting. In T. Fletcher, D. N. Chrónín, D. Gleddie, & S. Beni (Eds.), Meaningful physical education (pp. 87–100). Routledge.

- Howley, D., & Tannehill, D. (2014). “Crazy ideas”: Student involvement in negotiating and implementing the physical education curriculum in the Irish senior cycle. Physical Educator, 71, 391.

- Ingold, T. (2017). Anthropology and/as Education. Routledge.

- Kretchmar, R. S. (2007). What to do with meaning? A research conundrum for the 21st century. Quest (Grand Rapids, Mich), 59(4), 373–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2007.10483559

- Kretchmar, S. R. (2006). Ten more reasons for quality physical education. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 77(9), 6–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2006.10597932

- LaBoskey, V. K. (2004). The methodology of self-study and its theoretical underpinnings. In J. Loughran, M. L. Hamilton, V. K. LaBoskey, & T. Russell (Eds.), International handbook of self-study of teaching and teacher education practices (pp. 817–869). Springer Netherlands.

- Lindberg, M., & Mattsson, T. (2022). How much circus is allowed?–Challenges and hindrances when embracing risk in physical education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2022.2054971

- Loughran, J. (2006). Developing a pedagogy of teacher education: Understanding teaching & learning about teaching. Routledge.

- Loughran, J. (2014). Professionally developing as a teacher educator. Journal of Teacher Education, 65(4), 271–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487114533386

- Loughran, J., & Menter, I. (2019). The essence of being a teacher educator and why it matters. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 47(3), 216–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2019.1575946

- MacPhail, A., Tannehill, D., & Ataman, R. (2021). The role of the critical friend in supporting and enhancing professional learning and development. Professional Development in Education, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2021.1879235

- Mattsson, T., & Larsson, H. (2021). ‘There is no right or wrong way’: Exploring expressive dance assignments in physical education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 26(2), 123–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2020.1752649

- Mordal-Moen, K., & Green, K. (2014). Neither shaking nor stirring: A case study of reflexivity in Norwegian physical education teacher education. Sport, Education and Society, 19(4), 415–434.

- Ní Chróinín, D., Beni, S., Fletcher, T., Griffin, C., & Price, C. (2019). Using meaningful experiences as a vision for physical education teaching and teacher education practice. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 24(6), 598–614. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2019.1652805

- Ní Chróinín, D., Fletcher, T., Beni, S., Griffin, C., & Coulter, M. (2023). Children’s experiences of pedagogies that prioritise meaningfulness in primary physical education in Ireland. Education 3-13, 51(1), 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2021.1948584

- Ní Chróinín, D., Fletcher, T., & Griffin, C. A. (2018). Exploring pedagogies that promote meaningful participation in primary physical education. Physical Education Matters, 13, 70–73.

- Ní Chróinín, D., Fletcher, T., & O’Sullivan, M. (2018). Pedagogical principles of learning to teach meaningful physical education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 23(2), 117–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2017.1342789

- Ovens, A., & Fletcher, T. (2014). Doing self-study: The art of turning inquiry on yourself. In A. Ovens & T. Fletcher (Eds.), Self-study in physical education teacher education: Exploring the interplay of practice and scholarship (pp. 3–14). Springer International Publishing.

- Parameswaran, U. D., Ozawa-Kirk, J. L., & Latendresse, G. (2020). To live (code) or to not: A new method for coding in qualitative research. Qualitative Social Work, 19(4), 630–644. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325019840394

- Scanlon, D., Coulter, M., Baker, K., & Tannehill, D. (2024). The enactment of the socially-just teaching personal and social responsibility (SJ-TPSR) approach in physical education teacher education: Teacher educators' and pre-service teachers' perspectives. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2024.2319071

- Smith, Z., Carter, A., Fletcher, T., & Chróinín, D. N. (2023). What is important? How one early childhood teacher prioritised meaningful experiences for children in physical education. Journal of Early Childhood Education Research, 12, 126–149.