ABSTRACT

The compact city concept remains a key policy response to multiple societal challenges. Based on theoretical and empirical research, this article seeks to a) develop a systemic understanding of compact city qualities; b) map alleged compact city qualities from the literature onto this framework; c) map qualities mentioned by stakeholders in two European cities onto the same framework; and d) apply the developed framework to analyse how compounded compact city qualities relate to policy challenges, such as carbon neutrality, poverty alleviation, neighbourhood revitalization, or community engagement. It is based on literature reviews and interviews with stakeholders in Barcelona and Rotterdam.

Introduction

The notion of the compact city has been recurring in urban policy since the 1960s (see, e.g., Jacobs Citation1965; De Roo Citation1998; The Urban Task Force Citation1999). Today, the compact city concept remains a key response in global and national policy for tackling the multiple societal challenges that cities currently are facing, such as climate change, environmental degradation, economic development and social cohesion (Adelfio, Hamiduddin, and Miedema Citation2020). In 2011, the European Commission argued that compact urban structures are ‘an important basis for efficient and sustainable use of resources’ (European Commission Citation2011, 42). One year later, the OECD bestowed the compact city with the potential of meeting green growth objectives since ‘it can enhance both the environmental and the economic sustainability of cities’ (Citation2012, 19) and UN-Habitat claimed that ‘housing, employment, accessibility and safety (…) are strongly correlated to urban form’ (Citation2012, 13) and that policies on urban density will bring prosperity and social cohesion, and minimize negative environmental impacts; they will deliver ‘good quality of life at the right price’ (Citation2012, 13). The UNEP affirmed that ‘compact, relatively densely populated cities, with mixed-use urban form, are the most resource-efficient settlement pattern’ (UNEP Citation2013, 6) and, in 2016, the European Environment Agency (EEA) highlighted ‘compact city planning’ to ‘minimize land consumption, prevent unnecessary conversion of greenfields and natural areas to urban land, and to limit urban sprawl’ (EEA Citation2016, 18–9). Last but not least, the more recent New Urban Agenda confirmed the global policy concord on promoting urban density and mixed use (United Nations Citation2017).

Such international policies exert strong influence on how cities and neighbourhoods are planned locally, since the promotion of ideal urban models or ‘referencescapes’ (McCann Citation2017, 186) tends to ‘shape the global imaginary of urban practitioners and thus have very real effects’ (Rosol, Béal, and Samuel Citation2017, 1713). In many European cities, the compact city ideal has trickled down into local policy. The City of Barcelona, for example, pursues its Mediterranean version of the compact city (Rueda Citation2007), ‘improving the quality of life of the neighbourhoods through the adaptation of the housing stock to conditions appropriate for a socially advanced city’ (Ajuntament de Barcelona Citation2012, 15, translation from Catalan). The City of Rotterdam seeks to densify the housing stock in the inner city to offer ‘a strong and attractive downtown urban residential environment’ (Gemeente Rotterdam Citation2007, 34, translation from Dutch) with a balance between living and working.

The wide approval of compact cities as a major policy objective is problematic since there is no universal definition of what actually constitutes a compact city (Neuman Citation2005). In contrast to the relative consensus in global policy, the academic debate on compact cities is a multi-faceted mix of positive, negative and inconclusive accounts where the evidence supporting the policy claims is inconclusive and often contradictory (Breheny Citation1996; Burton Citation2001; Cheshire Citation2006; Arbaci and Rae Citation2013). Already in 1999, Frey brought together arguments for and against the compact city (Frey Citation1999). More recently, Boyko and Cooper’s (Citation2011) review of 75 studies presents a comprehensive list of assumed advantages and disadvantages of different types of high urban densities and Ahlfeldt and Pietrostefani (Citation2017) summarize a comprehensive list of primary compact city outcomes drawing on 189 studies.

Compared to urban policy, it is obvious that the research debate is far more divided where Holman et al. (Citation2015) distinguish two opposite mindsets. On the one hand, the discourse of conviction emphasizes the role of planning and compact cities are seen as a certain remedy for any urban illness, and especially for economic decay, tracing its origins back to Jane Jacobs’ (Citation1965) work on life and liveability in American cities. On the other hand, the discourse of suspicion downplays the importance of built form for urban sustainability. Here, it is argued that a city cannot be reduced into its physical structures and the emphasis is, instead, placed on behaviour, choice and the free market as the real and appropriate drivers of urban development.

Holman et al. (Citation2015) see both these discourses as rather dogmatic, where proponents may have little interest in contradictory evidence. The focus is often on using ‘leading paradigms’ (Rosol, Béal, and Samuel Citation2017, 1710) for marketing urban development solutions rather than providing evidence of their merit. As an example, UN-Habitat delivers normative recipes for sustainable neighbourhood planning – with precise figures for desired population density and mix of land use and tenure types – but based on weak empirical evidence considering the potential impact on local realities (UN-Habitat Citation2014, Citationn.d). Such policy advice is highly problematic since there is a serious lack of evidence regarding how compact cities actually perform across different urban forms, scales and societies in relation to, e.g., improved health, access to urban green space and mitigation of disasters, and especially how both impacts and interventions unfold on the neighbourhood level (Dempsey and Jenks Citation2010; Ahlfeldt and Pietrostefani Citation2017).

At present, the nexus of the compact city discourses of conviction and suspicion has increasingly been focusing on climate change mitigation (e.g., O’Brien and Selboe Citation2015; Fujii, Iwata, and Managi Citation2017; Angel et al. Citation2020), where cities are seen to play a key role in achieving a zero-carbon society (Arabzadeh et al. Citation2020; The Global Commission on the Economy and Climate Citation2014; Dale et al. Citation2020; Covenant of Mayors for Climate & Energy Citation2020). Still, the obligation to attain zero-carbon cities is just one out of a plethora of interlinked environmental, social and economic predicaments, forming an entwined global emergency (Asara et al. Citation2015). Although zero-carbon measures based on urban densification can bring a wide range of important co-benefits linked to, e.g., health, biodiversity and economy (Karlsson, Alfredsson, and Westling Citation2020), climate change mitigation policies may also lead to serious adverse effects on liveability and well-being (Lehmann Citation2019). Also, linking, e.g., climate change mitigation too closely to the spatial dimensions of urban compactness disregards the relational nature of the compact city as a constantly reproduced ‘assemblage’ of ‘co-functioning […] elements’ (Kjærås Citation2020, 8). All in all, there is a need for an improved understanding of these complexities to provide better support for urban policymaking and planning in the context of urban compaction.

Here, Holman et al. (Citation2015) bring forward a third and more pragmatist discourse, arguing for the empirical study of actual benefits or detriments of compact city policies. Instead of being either convinced or suspicious, pragmatists aim to better understand the many complexities inherent in the development of any city, and how these relate to urban compactness when implemented on the ground. In this research context, different types of analytical frameworks have been proposed to better understand the mechanisms and potential benefits of compact cities (e.g., Frey Citation1999; Boyko and Cooper Citation2011; Cho, Trivic, and Nasution Citation2015; Larco Citation2016; Ahlfeldt and Pietrostefani Citation2017; Zhang Citation2017). Although these are very helpful, each one only covers parts of the wide compact city debate and thus only fragments of the abovementioned intricacies of intertwined synergies and trade-offs. Based on a mix of theoretical and empirical research, the aim of the present study is, therefore, to contribute to the pragmatist discourse by meeting the following objectives:

to develop an analytical framework facilitating a systemic understanding of what urban qualities (both positive and negative) a compact city can (or should) deliver;

to map alleged compact city qualities (both positive and negative) found in the literature onto such a systemic framework to assess its usefulness for grasping contemporary urban complexity and challenges;

to map compact city qualities mentioned by urban stakeholders in two European cities onto the same systemic framework to further study its usefulness; and

to tentatively apply the developed framework to analyse how compounded and interdependent ‘states’ and ‘impacts’ of compact city qualities may act on various contemporary policy challenges, such as carbon neutrality, poverty alleviation, neighbourhood revitalization, or community engagement.

Below, Section 2 presents the methods used to collect data and Section 3 introduces the analytical framework that will support the study in response to the first objective. Section 4 presents the results, subdivided into three parts corresponding to the last three objectives. In Section 5, the results are discussed and some conclusions are drawn.

Methods

The first objective of the paper – to develop a systemic analytical framework – was addressed through a scoping review of the state of the art, focusing on identifying main characteristics of the compact city debate. A complementary and more systematic review was carried out, focusing on literature with a publication period just before the data collection in the two cities took place (see below), i.e., 2014–2015. The data was collected based on a search in the Scopus database, using the search term ‘compact city’ and 84 articles were identified. The plethora of compact city qualities (both positive and negative) mentioned in the literature were arranged based on systems thinking, specifically by applying the DPSIR (Drivers, Pressures, States, Impacts and Responses) approach promoted by the EEA (Citation1999) onto the urban development context, providing ‘a heuristic framework for the analysis of cause–effect relationships in complex systems’ (Haase and Nuissl Citation2007, 3). The framework was verified further through iterations based on the results from the stakeholder interviews (see below).

Meeting the second objective – to map alleged compact city qualities (both positive and negative) found in the literature onto the systemic framework – was also based on the results from the systematic review of the 84 articles from which terms used to label alleged or contested qualities of compact cities were sifted out and counted. This made it possible to calculate aggregated results based on the number of occurrences of these terms for each one of the fields of the analytical framework. For example, articles were mentioning qualities, such as ‘promote walking’, ‘pedestrian friendliness’, ‘sidewalk attributes’ and ‘design for walking’, and each one of these would tick off one occurrence of the compact city quality ‘walkability’, in turn belonging to the sub-category ‘Built structures/Access’. Note, however, that each occurrence can represent a compact city quality term mentioned briefly as well as more extensive and/or empirically grounded discussions on compact city qualities. Such work is used as a basis to expand on and subsequently gear this work more specifically towards contemporary urban challenges through the fourth objective.

The third objective – to map compact city qualities mentioned by urban stakeholders onto the systemic framework – was addressed by carrying out interviews with a broad range of urban stakeholders in two European cities, 44 in Barcelona (in 2014–2015) and 38 in Rotterdam (in 2015–2016) (see ). Also interviewed researchers, typically engaged in bridging the local science–policy gap, were considered as stakeholders (Hirsch Hadorn et al. Citation2006; Jacobi et al. Citation2020). The interviews followed an in-depth, semi-structured interview format (Kvale Citation1996), where the interviewees were encouraged to approach the topic from their own professional and personal experiences. The interviews were audio recorded and the data was analysed and coded directly from the recordings, thus only partially transcribed. Similar to the data from the literature review, the occurrence for different terms used to describe compact city qualities was registered to facilitate aggregated results. Note that also here each occurrence may represent a compact city quality mentioned briefly as well as in more extensive and/or empirically grounded discussions.

Table 1. Number and categorization of interviewees in Barcelona and Rotterdam

The fourth objective – to tentatively apply the framework to identify and appraise interdependencies, synergies and trade-offs emerging from compact city policies – builds on previous research developed by e.g., Haase et al. (Citation2012), Fertner and Grosse (Citation2016) and Adelfio et al. (Citation2020). This objective was tackled through a qualitative analysis of causal loops as applied in System Dynamics (e.g., Kirkwood Citation1998) as a way of ‘dancing’ (Meadows Citation2009, 165) with the systems of compact city qualities. Reinforcing and counteracting links were identified, and subsystems linked to current policy challenges were pinpointed.

Analytical framework

The analytical framework is based on two components: a) main categories of compact city qualities and b) compact city qualities as states and impacts.

Main categories of compact city qualities

The research literature on compact cities is abundant, representing many different perspectives and objectives depending on the individual research endeavours. Drawing on the literature (where many of the cited references, in turn, draw on multiple sources), compact city qualities can be grouped into main categories.

Intensity (density)

The self-evident factor of compact cities is their density – or intensity – measured as the quantity of a specified feature within a certain area, usually km2 or hectare but can also refer to a lot, parcel, block, neighbourhood, city or metropolitan region (Boyko and Cooper Citation2011). Intensity can be about e.g., residential population (Dantzig and Saaty Citation1973; Churchman Citation1999; Burton Citation2002), employment opportunities (Neuman Citation2005), impervious surfaces (Neuman Citation2005; Boyko and Cooper Citation2011), green space (Rueda Citation2014), building coverage (Berghauser Pont and Haupt Citation2009), floor area (Berghauser Pont and Haupt Citation2009), dwellings or units (Churchman Citation1999; Burton Citation2002), and building heights (Berghauser Pont and Haupt Citation2009) or building volume (Koomen, Rietveld, and Bacao Citation2009). However, intensity can also refer to qualitative understandings of how intensely urban space is used (Westerink et al. Citation2013).

Diversity (mixed use, mixed functions, complexity)

Mixed land use leading to diversity is another key aspect of compact cities (Dantzig and Saaty Citation1973; Neuman Citation2005). A ‘varied and plentiful supply of facilities and services’ (Burton Citation2002, 224) is seen to lead to local self-sufficiency (Dantzig and Saaty Citation1973; Rueda Citation2014). Diversity can also be seen as the complexity arising from the interactions between ‘economic activities, associations, facilities and institutions’ (Rueda Citation2014, 14). The mix of uses can be both horizontal and vertical (layering), and also involve interweaving (combining functions in the same space) or timing (using the same space for different functions over time) (Burton Citation2002; Haccou et al. Citation2007). Arguments for increased diversity in already dense urban environments implicitly also tend to argue for a densification of functions other than just housing, such as shops, businesses, offices, services, leisure, open space, and green space. A particular aspect of diversity is that ‘the same density can be obtained with radically different building types’ (Lozano Citation1990, here from Berghauser Pont and Haupt Citation2009, 17).

Access (proximity, distance, accessibility, mobility, efficiency, infrastructural connectivity)

Short distances represent the most significant element of a compact city (Boyko and Cooper Citation2011; OECD Citation2012; Kasraian, Maat, and Van Wee. Citation2017; Hamiduddin Citation2018). Diversity in combination with fine-grain land use patterns provide a potential for proximity to functions, services and jobs (Burton Citation2002; Neuman Citation2005; Rueda Citation2014), which in turn encourages walking and biking (Næss and Vogel Citation2012; Boussauw, Neutens, and Witlox Citation2012). People living close to each other will presumably interact more (Burton Citation2002), but effective infrastructural/IT connectivity supports intense interaction decoupled from urban density (Porqueddu Citation2015). In parallel to proximity, improved mobility (e.g., transit-oriented development, Calthorpe Citation1993), accessibility (Neuman Citation2005; Ewing and Cervero Citation2010), and infrastructural connectivity (Zonneveld Citation2005) are emphasized as key compact city features, also including the infrastructure supporting an efficient urban metabolism (Neuman Citation2005; Rueda Citation2014). Short distances to public transport are crucial for multi-modal mobility through local and regional networks (Neuman Citation2005; Næss and Vogel Citation2012). Opening hours, income, gender, educational level and vehicle ownership also affect accessibility (Geurs and Van Wee. Citation2004). All in all, access is a matter of complex relationships with the other main categories of compact city qualities (Boussauw, Neutens, and Witlox Citation2012).

Form (morphology, network connectivity)

A compact city is clearly contained from its surroundings (Neuman Citation2005), originally as a monocentric city (Dantzig and Saaty Citation1973). Today, clustered deconcentration (Westerink et al. Citation2013) or polycentric configurations (Breheny Citation1996) are seen as more beneficial, with a multitude of variants, such as the Finger, Star, Linear and Satellite city (Frey Citation1999). Polycentrism is also reflected in green structure planning, with urban nature shaped as interconnected corridors between built-up areas (Greensurge Citation2015). Zooming out to the city or metropolitan scale, polycentrism brings a heterogeneity of densities due to the presence of less dense urban functions (Churchman Citation1999; Berghauser Pont and Haupt Citation2009). Urban form also links to network connectivity, i.e., the coverage, densities and integration of different types of urban networks (sidewalks, biking lanes, streets, roads, rail, etc.) (Hillier Citation1996; Berghauser Pont and Haupt Citation2009), where networks for walking and biking are of particular interest (Dill Citation2004).

Size

The above-mentioned proximity is relative to scale, but ‘in the literature on the compact city, often no distinction is made between small towns and metropolises’ (Boussauw, Neutens, and Witlox Citation2012, 690). Still, to be meaningful, a compact city ‘must be large enough to support the whole range of services and facilities’ (Burton Citation2002, 220), with an economy large enough to finance its amenities and infrastructure (Neuman Citation2005). Furthermore, some compact city properties, such as more choice, opportunities and innovations, health issues, and criminality, seem to depend more on size than on compactness (Neuman Citation2005; Bettencourt et al. Citation2007).

Compact city qualities as states and impacts

From an urban economics perspective, Ahlfeldt and Pietrostefani (Citation2017) suggest that compact city qualities can be divided into characteristics (causes) and outcomes (effects), where the characteristics are defined as ‘economic density’, ‘morphological density’, and ‘mixed land use’. Although helpful, a wider categorization of compact city qualities seems useful since Ahlfeldt and Pietrostefani’s framework, for example, largely overlooks the importance of urban nature and all its ecosystem functions and services (TEEB Citation2011).

Also, since the compact city concept is both contested and poorly defined (Neuman Citation2005; Boyko and Cooper Citation2011; Holman et al. Citation2015), compact city qualities (such as having a socially mixed neighbourhood) need to be disentangled from urban driving forces (Adelfio et al. Citation2018) (such as gentrification) and urban strategizing (such as promotion of mixed-tenure neighbourhoods). The DPSIR framework (EEA, Citation1999) is a causal chain model distinguishing between Drivers, Pressures, States, Impacts and Responses that has been widely used in environmental assessment. DPSIR has also proven useful in understanding change in relation to a wider set of urban functions and types of land use (Tscherning et al. Citation2012; EEA, Citation2016; Manitiua et al. Citation2016) and for sustainability assessment of urban neighbourhoods (Zhao and Bottero Citation2010). It is a straightforward tool, adaptable to new analytical contexts (Spanò et al. Citation2017). Still, it is important to understand how impacts, in turn, may induce secondary and even tertiary impacts (McDonnell and Zellner Citation2011; Brown, Moodie, and Carter Citation2015; see also the literature on evaluation of public policy, e.g., Vedung Citation2006), for example how a decrease in car use, first leads to less air pollution and then to improved pulmonary health (Cooper Citation2004).

DPSIR has not been free of criticism (e.g., Carr et al. Citation2007) and caution is in place. By applying the DPSIR framework to the analysis of urban transformation it is assumed that different configurations of, e.g., demography, buildings and urban nature are States that subsequently generate diverse types of Impacts. First, it is highly questionable whether it is possible, or even desirable, for planning (i.e., of physical urban space) alone to deliver such States that subsequently have Impacts on the complexities of human societies (Gleeson Citation2012, see also the discourse of suspicion above). Second, the idea of linear causalities is not easily reconciled with current notions of urban complexity, where we rather should look for multiple and multi-directional correlations (Niemeijer and De Groot Citation2008; Tscherning et al. Citation2012). Simplified and naïve application of the DPSIR model may lead to policies with undesirable societal impacts (Rekolainen et al. Citation2003). Keeping these limitations in mind, an analytical framework dividing compact city qualities into states and primary and secondary impacts is still valid as a starting point for a systemic understanding of compact city qualities.

A systemic analytical framework

Based on the above, our search for a systemic understanding of compact city qualities is based on an analytical framework intersecting states and impacts with the four main categories of compact city qualities: Intensity, Diversity, Access and Form (see ). City size is omitted from this framework since it does not appear to be an essential category of compact cities (as mentioned in Section 3.1). The states and impacts are then broken down into specific themes, further elaborated below (see ).

Table 2. A systemic analytical framework for compact city qualities

Table 3. The analytical framework for compact city qualities, with the identified main themes and displaying the number of occurrences of different compact city qualities in the 84 articles

Results and analysis

The academic discourse on compact city qualities

The review of the 84 articles linked to the notion of compact cities inductively identified ten main themes of compact city qualities (both positive and negative), labelled as People, Built structures, Nature, Socioculture, Environment, Economy, Health, Quality of life, Justice, and Adaptability. Building on the DPSIR framework, these ten themes were then subdivided into states and (primary and secondary) impacts of compact city development (see ). The analysis also counted the occurrences of the main themes in the reviewed articles, providing an indication of how the literature placed its emphasis within the compact city discourse.

Local discourses on compact city qualities: Barcelona and Rotterdam

The analysis of the abundant material from interviews with stakeholders in Barcelona and Rotterdam did not identify any new main themes. Still, the distribution across the analytical framework of the occurrences of compact city qualities showed how urban stakeholder place a different emphasis on which compact city qualities are the most relevant to discuss and address (see ).

Table 4. Interview data regarding the number of compact city qualities occurrences from a) Barcelona (BCN) and b) Rotterdam (ROT) inserted into the analytical framework for compact city qualities

Compared to the literature review, the analysis of the interview material provided a richer understanding of what compact city qualities are seen to entail by urban stakeholders (see examples in ). We could also see that new types of qualities – and new dimensions of qualities – emerged that were not represented in the reviewed scientific articles.

Table 5. Examples from the literature (with number of hits within brackets) and from the interviews (with city indicated: Barcelona = BCN; Rotterdam = ROT)

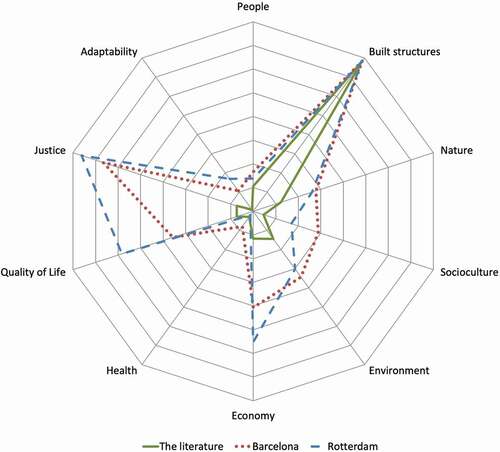

The two-tier analysis also made it possible to compare academic and stakeholder discourses on compact city qualities (see ). A first observation is that neither the literature nor the stakeholders discuss ‘People’ much as an important theme of compact cities, but presumably an increased density, diversity and proximity of people is seen as a self-evident outcome of a higher intensity of ‘Built structures’, such as housing and workplaces. Also, compared to the literature, the stakeholders seem to emphasize ‘Nature’ much more.

Figure 1. A comparison between number of occurrences of compact city qualities in the literature and stakeholder interviews in Barcelona and Rotterdam. The theme ‘Built structures’ is set as a common scale reference to facilitate comparison.

Furthermore, urban stakeholders seem to be much more interested in the impacts of compact city development, where the primary impacts ‘Socioculture’, ‘Environment’ and ‘Economy’ stand out in particular; Barcelona with an emphasis on socioculture and Rotterdam on economy. Interestingly, ‘Health’ is not mentioned much in neither the literature nor the interviews, but is slightly more discussed in Barcelona, compared to both the literature and Rotterdam stakeholders. Another interesting observation is that the two secondary impact qualities ‘Quality of life’ and ‘Justice’ are significantly more mentioned by the interviewees than in the literature, where Rotterdam is almost placing as much focus on justice as on built structures. When it comes to ‘Adaptability’, hardly mentioned at all in the literature, urban stakeholders place somewhat more weight on this aspect.

Appraising interdependencies of compact city qualities in relation to contemporary policy challenges

In the following, Barcelona is used as an example to explore how compounded states and impacts of compact city qualities can be analysed in relation to a certain policy objective, in this case Barcelona as a zero-carbon city (Ajuntament de Barcelona Citation2018). Out of the full set of compact city qualities identified from the stakeholder interviews, a selection was placed in the analytical framework, displaying synergies and trade-offs of Barcelona compact city qualities with relevance to ambitions for a zero-carbon city.Footnote1 These qualities were then analysed with regard to potential causal interdependencies.

Although representing a simplification, the many identified interdependencies immediately reveal the high degree of complexity and ‘wickedness’ (Churchman Citation1967; Rittel and Webber Citation1973) linked to carbon neutrality as a policy objective. To increase the legibility of the analysis, some subsystems were outlined and colour-coded: Mixed use and complexity; Quality of life; Tourism economy; and Inclusive planning and governance1. For instance, the branding of Barcelona as a ‘global city’ has significantly boosted the number of tourists, which has benefits for employment and the local economy, but directly increases the carbon footprint from air travel and cruise ships. Extensive tourism also puts pressure on the housing market, where tourist flats and escalating real estate values push low-income households out from several parts of the city. This leads to gentrification, a migration of less affluent households to satellite municipalities in the metropolitan region poorly serviced by public transport, and thus to increased commuting by car or motorbike. Tourist crowds also tend to exclude inhabitants from the local urban spaces vital for quality of life and strong local engagement. A key element of Barcelona’s zero-carbon policy is the ‘proximity of everything’ in a walkable city but this objective is seriously threatened by all these compounded impacts leading to less demographic, social, cultural, political and economic diversity, which affect the offer of local services and amenities and impoverish local life and identity. These are just a few examples. A full account subsystem interdependencies would require a more detailed examination of a wider set of urban qualities and their interdependencies.

Discussion and conclusions

The analysis of the combined empirical material – academic literature and stakeholder interviews – seems to confirm the relevance and usefulness of a systemic analytical approach. The systemic approach provided a more wide-ranging as well as a more detailed understanding of compact city qualities. Such a systemic understanding is essential for an effective and transparent approach to sustainable urban transformation (Coral and Bokelmann Citation2017) and can function as a platform for identifying, understanding, discussing and negotiating what compact city qualities should be prioritized in specific urban contexts. The presented analysis of qualities focuses more on qualitative concepts rather than on the quantitative measurement of compact city qualities through metrics. By doing so, this paper takes the distance from the ‘institutionalized concept of the compact city – focused on establishing minimum thresholds of residential density’ (Górgolas Citation2018, 58) and also embraces the relativeness of the compactness and density concepts as described by Lehmann (Citation2016).

There are many ways to cut a cake, and the elements of our main compact city quality categories (Intensity, Diversity, Access, Form) can obviously be arranged differently, with slightly different boundaries between the categories. For example, there are arguments for dividing the category access in two: e.g., labelled as Proximity (Boussauw, Neutens, and Witlox Citation2012) and Accessibility (Rode et al. Citation2014) where the first deals with distance (Hamiduddin Citation2018) and the second to connectivity (Peponis, Bafna, and Zhang Citation2008). Also, there is a certain overlap between infrastructural connectivity (now part of Access) and connectivity resulting from urban Form, e.g., when it comes to network density and integration. There may also be strong arguments for bringing city size back into a compact city quality framework (Echenique et al. Citation2012).

Also, even if the content of most of the boxes in the compact city quality framework was straightforward to fit into the systemic format, there were some glitches that suggest that the systemic approach needs further work. Fitting the empirical data into the framework was at times a bit forced. For example, the content of the intersections of People/Access and Adaptability/Form did not come out as self-evident and may well be debated further, and for one intersection neither the literature nor the interviews provided any content and it remained empty, i.e., Adaptability/Access.

At times, the notion of cause-and-effect dependencies – from state to primary and then to secondary impacts – proved difficult to pinpoint. For example, attractive public space (Quality of life/Diversity) is categorized as a secondary impact, e.g., from social and cultural diversity (Socioculture/Diversity) but one may as well argue that rich outdoor social life depends on high quality outdoor space. This confirms the arguments by several authors already highlighted in Section 3.2 that there are seldom any linear linkages but instead multidirectional and complex interdependencies (Rekolainen et al. Citation2003; Boussauw, Neutens, and Witlox Citation2012; Gleeson Citation2012; Tscherning et al. Citation2012). Moreover, ‘the interconnectedness of urban features, urban systems and related flows (…) may create a cascade (or “domino” effect) of impacts’ (Wamsler and Brink Citation2015, 5).

To conclude, the proposed systemic framework has proven useful for meeting the four objectives of this article. Complementary to the earlier compact city frameworks mentioned above, it has been helpful for structuring the diversity of compact city qualities brought forward in the literature, as well as discussed among urban professionals and stakeholders. The systemic framework has also facilitated a more nuanced understanding of how different aspects associated with the diverse states of compact cities correlate to – and potentially cause (or are caused by) – different types of impacts, where positive impacts are to be strengthened and negative impacts tackled.

Our findings suggest that any policy measure or analytical effort linked to urban compactness needs to respect the prevailing complexity and bear in mind the iterative movement between different types of states and impacts as highlighted above. The proposed framework provides an improved understanding of the multiple factors that need to be taken into account by urban planners and decision makers who advocate for compact city development as a response to multiple urban policy challenges, such as carbon neutrality, poverty alleviation, neighbourhood revitalization, or community engagement. Furthermore, previous research (Adelfio et al. Citation2018; Adelfio, Hamiduddin, and Miedema Citation2020) has shown the significant influence of local specificities and complexities on the implementation of compact city policies. Here, the qualitative focus of the proposed framework, rather than providing metrics or thresholds, allows for a much-needed flexibility and adaptability to local contexts in urban analysis and policy making.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

References

- Adelfio, M., I. Hamiduddin, and E. Miedema. 2020. “London’s King’s Cross Redevelopment: A Compact, Resource Efficient and ‘Liveable’ Global City Model for an Era of Climate Emergency?” Urban Research & Practice 1–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17535069.2019.1710860.

- Adelfio, M., J.-H. Kain, L. Thuvander, and J. Stenberg. 2018. “Disentangling the Compact City Drivers and Pressures: Barcelona as a Case Study.” Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift - Norwegian Journal of Geography 72 (5): 287–304. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00291951.2018.1547788.

- Ahlfeldt, G. M., and E. Pietrostefani. 2017. The Compact City in Empirical Research: A Quantitative Literature Review. Swindon, UK: Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC).

- Ajuntament de Barcelona. 2012. Marc Estratègic De l’Ajuntament De Barcelona: Programa d’Actuació Municipal 2012–2015. Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona.

- Ajuntament de Barcelona. 2018. Barcelona Climate Plan 2018–2030. Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona.

- Angel, S., S. A. Franco, Y. Liu, and A. M. Blei. 2020. “The Shape Compactness of Urban Footprints.” Progress in Planning 139: 100429. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2018.12.001.

- Arabzadeh, V., J. Mikkola, J. Jasiūnas, and P. D. Lund. 2020. “Deep Decarbonization of Urban Energy Systems through Renewable Energy and Sector-coupling Flexibility Strategies.” Journal of Environmental Management 260 (110090): 110090. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110090.

- Arbaci, S., and I. Rae. 2013. “Mixed-Tenure Neighbourhoods in London: Policy Myth or Effective Device to Alleviate Deprivation?” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37 (2): 451–479. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2012.01145.x.

- Asara, V., I. Otero, F. Demaria, and E. Corbera. 2015. “Socially Sustainable Degrowth as a Social–ecological Transformation: Repoliticizing Sustainability.” Sustainability Science 10 (3): 375–384. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-015-0321-9.

- Berghauser Pont, M., and P. Haupt. 2009. Space, Density and Urban Form. Delft: Technische Universiteit Delft.

- Bettencourt, L. M. A., J. Lobo, D. Helbing, C. Kühnert, and G. B. West. 2007. “Growth, Innovation, Scaling, and the Pace of Life in Cities.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104 (17): 7301–7306. doi:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0610172104.

- Boussauw, K., T. Neutens, and F. Witlox. 2012. “Relationship between Spatial Proximity and Travel-to-Work Distance: The Effect of the Compact City.” Regional Studies 46 (6): 687–706. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2010.522986.

- Boyko, C. T., and R. Cooper. 2011. “Clarifying and Re-conceptualising Density.” Progress in Planning 76 (1): 1–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2011.07.001.

- Breheny, M. 1996. “Centrists, Decentrists and Compromisers: Views on the Future of Urban Form.” In The Compact City: A Sustainable Urban Form? edited by M. Jenks, E. Burton, and K. Williams, 13–35. London: E & FN Spon.

- Brown, V., M. Moodie, and R. Carter. 2015. “Congestion Pricing and Active Transport – Evidence from Five Opportunities for Natural Experiment.” Journal of Transport & Health 2 (4): 568–579. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2015.08.002.

- Burton, E. 2001. “The Compact City and Social Justice.” Paper presented at the The Housing Studies Association Spring Conference: Housing, Environment and Sustainability, York, 18-19 April 2001.

- Burton, E. 2002. “Measuring Urban Compactness in UK Towns and Cities.” Environment and Planning. B, Planning & Design 29: 219–250. doi:https://doi.org/10.1068/b2713.

- Calthorpe, P. 1993. The Next American Metropolis: Ecology, Community, and the American Dream. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

- Carr, E. R., P. M. Wingard, S. C. Yorty, M. C. Thompson, N. K. Jensen, and J. Roberson. 2007. “Applying DPSIR to Sustainable Development.” International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology 14 (6): 543–555. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504500709469753.

- Cheshire, P. C. 2006. “Resurgent Cities, Urban Myths and Policy Hubris: What We Need to Know.” Urban Studies 43 (8): 1231–1246. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980600775600.

- Cho, I. S., Z. Trivic, and I. Nasution. 2015. “Towards an Integrated Urban Space Framework for Emerging Urban Conditions in a High-density Context.” Journal of Urban Design 20 (2): 147–168. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2015.1009009.

- Churchman, A. 1999. “Disentangling the Concept of Density.” Journal of Planning Literature 13 (4): 389–411. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/08854129922092478.

- Churchman, C. West. 1967. “Wicked Problems.” Management Science 14 (4): B141–142.

- Cooper, L. M. 2004. Guidelines for Cumulative Effects Assessment in SEA of Plans. London: Imperial College.

- Coral, C., and W. Bokelmann. 2017. “The Role of Analytical Frameworks for Systemic Research Design, Explained in the Analysis of Drivers and Dynamics of Historic Land-Use Changes.” Systems 5 (20): 1–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/systems5010020.

- Covenant of Mayors for Climate & Energy. https://www.covenantofmayors.eu/en/ [Accessed 16 December 2020].

- Dale, A., J. Robinson, L. King, S. Burch, R. Newell, A. Shaw, and F. Jost. 2020. “Meeting the Climate Change Challenge: Local Government Climate Action in British Columbia, Canada.” Climate Policy 20 (7): 866–880. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2019.1651244.

- Dantzig, G. B., and T. L. Saaty. 1973. Compact City: Plan for a Liveable Urban Environment. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman.

- De Roo, G. 1998. “Environmental Planning and the Compact City a Dutch Perspective.” In Studies in Environmental Science, edited by T. Schneider, 1027–1042, Elsevier.

- Dempsey, N., and M. Jenks. 2010. “The Future of the Compact City.” Built Environment 36 (1): 116–121. doi:https://doi.org/10.2148/benv.36.1.116.

- Dill, J. 2004. “Measuring Network Connectivity for Bicycling and Walking.” 83rd Annual Meeting of the Transportation Research Board: Washington, D.C.

- Echenique, M. H., A. J. Hargreaves, G. Mitchell, and A. Namdeo. 2012. “Growing Cities Sustainably: Does Urban Form Really Matter?” Journal of the American Planning Association 78 (2): 121–137. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2012.666731.

- EEA. 1999. Environmental Indicators: Typology and Overview. Copenhagen: European Environment Agency.

- EEA. 2016. Soil Resource Efficiency in Urbanised Areas: Analytical Framework and Implications for Governance. Luxembourg: European Environment Agency.

- EEA-FOEN. 2016. “Urban Sprawl in Europe (Joint EEA-FOEN Report).” European Environment Agency and the Swiss Federal Office for the Environment.

- European Commission. 2011. Cities of Tomorrow – Challenges, Visions, Ways Forward. Brussels: European Commission, Directorate General for Regional Policy.

- Ewing, R., and R. Cervero. 2010. “Travel and the Built Environment.” Journal of the American Planning Association 76 (3): 265–294. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01944361003766766.

- Fertner, C., and G. Juliane. 2016. “Compact and Resource Efficient Cities? Synergies and Trade-offs in European Cities.” European Spatial Research and Policy 23 (1): 65–79. doi:https://doi.org/10.1515/esrp-2016-0004.

- Frey, H. 1999. “Compact, Decentralised or What? the Sustainable City Debate.” In Designing the City. Towards a More Sustainable Urban Form, edited by H. Frey, 23–35. London: E & FN Spoon.

- Fujii, H., K. Iwata, and S. Managi. 2017. “How Do Urban Characteristics Affect Climate Change Mitigation Policies?” Journal of Cleaner Production 168: 271–278. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.08.221.

- Geurs, K. T., and B. Van Wee. 2004. “Accessibility Evaluation of Land-use and Transport Strategies: Review and Research Directions.” Journal of Transport Geography 12 (2): 127–140. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2003.10.005.

- Gleeson, B. 2012. ““Make No Little Plans’: Anatomy of Planning Ambition and Prospect.’.” Geographical Research 50 (3): 242–255. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-5871.2011.00728.x.

- Górgolas, P. 2018. “El reto de compactar la periferia residencial contemporánea: Densificación eficaz, centralidades selectivas y diversidad funcional.” ACE: Architecture, City and Environment = Arquitectura, Ciudad Y Entorno 13 (38): 57–80. doi:https://doi.org/10.5821/ace.13.38.5211.

- Greensurge. 2015. “A Typology of Urban Green Spaces, Eco-system Provisioning Services and Demands.”

- Haase, D., and H. Nuissl. 2007. “‘Does Urban Sprawl Drive Changes in the Water Balance and Policy?: The Case of Leipzig (Germany) 1870–2003.” Landscape and Urban Planning 80 (1): 1–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2006.03.011.

- Haase, D., N. Schwarz, M. Strohbach, F. Kroll, and R. Seppelt. 2012. “Synergies, Trade-offs, and Losses of Ecosystem Services in Urban Regions: An Integrated Multiscale Framework Applied to the Leipzig-Halle Region, Germany.” Ecology and Society 17 (3):22 17 (3): 22.

- Haccou, H. A., T. Deelstra, A. Jain, V. Pamer, K. Krosnicka, and R. De Waard. 2007. MILU: Multifunctional and Intensive Land Use – Principles, Practices, Projects and Policies. Gouda: Habiforum Foundation.

- Hadorn, H., D. B. Gertrude, C. Pohl, S. Rist, and U. Wiesmann. 2006. “‘Implications of Transdisciplinarity for Sustainability Research.” Ecological Economics 60 (1): 119–128. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2005.12.002.

- Hamiduddin, I. 2018. “Journey to Work Travel Outcomes from ‘City of Short Distances’ Compact City Planning in Tübingen, Germany.” Planning Practice & Research 33 (4): 372–391. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2017.1378980.

- Hillier, B. 1996. Space Is the Machine: A Configurational Theory of Architecture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Holman, N., A. Mace, A. Paccoud, and J. Sundaresan. 2015. “Coordinating Density; Working through Conviction, Suspicion and Pragmatism.” Progress in Planning 101: 1–38. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2014.05.001. October 2015.

- Jacobi, J., A. Llanque, S. Bieri, E. Birachi, R. Cochard, N. Depetris Chauvin, C. Diebold, et al. 2020. “Utilization of Research Knowledge in Sustainable Development Pathways: Insights from a Transdisciplinary Research-for-development Programme.” Environmental Science & Policy 103 (21): 21–29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2019.10.003.

- Jacobs, J. 1965. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. 2 ed. London: Penguin Books.

- Karlsson, M., E. Alfredsson, and N. Westling. 2020. “Climate Policy Co-benefits: A Review.” Climate Policy 20 (3): 292–316. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2020.1724070.

- Kasraian, D., K. Maat, and B. Van Wee. 2017. “The Impact of Urban Proximity, Transport Accessibility and Policy on Urban Growth: A Longitudinal Analysis over Five Decades.” Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science 46 (6): 1000–1017. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2399808317740355.

- Kirkwood, C. W. 1998. System Dynamics Methods: A Quick Introduction. Tempe, AZ: Arizona State University.

- Kjærås, K. 2020. “Towards a Relational Conception of the Compact City.” Urban Studies published online: 1–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098020907281.

- Koomen, E., P. Rietveld, and F. Bacao. 2009. “The Third Dimension in Urban Geography: The Urban-volume Approach.” Environment and Planning. B, Planning & Design 36 (6): 1008–1025. doi:https://doi.org/10.1068/b34100.

- Kvale, S. 1996. Interviews: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Larco, N. 2016. “Sustainable Urban Design – A (Draft) Framework.” Journal of Urban Design 21 (1): 1–29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2015.1071649.

- Lehmann, S. 2016. “Sustainable Urbanism: Towards a Framework for Quality and Optimal Density?” Future Cities and Environment 2 (1): 8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40984-016-0021-3.

- Lehmann, S. 2019. “Understanding and Quantifying Urban Density toward More Sustainable City Form.” In The Mathematics of Urban Morphology. Modeling and Simulation in Science, Engineering and Technology, edited by L. D'Acci, 547–556. Cham: Birkhäuser.

- Lozano, E. 1990. “Density in Communities, or the Most Important Factor in Building Urbanity.” In The Urban Design Reader., edited by M. Larice and E. Macdonald, 312–327. London, New York: Routledge.

- Manitiua, D. N., G. Pedrini, R. A. Grant, T. A. Baker, and R. T. Sauer. 2016. “‘Urban Smartness and Sustainability in Europe. An Ex Ante Assessment of Environmental, Social and Cultural Domains.” European Planning Studies 24 (10): 1766–1787. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2016.1193127.

- McCann, E. 2017. “Mobilities, Politics, and the Future: Critical Geographies of Green Urbanism.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 49 (8): 1816–1823. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X17708876.

- McDonnell, S., and M. Zellner. 2011. “Exploring the Effectiveness of Bus Rapid Transit a Prototype Agent-based Model of Commuting Behavior.” Transport Policy 18 (6): 825–835. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2011.05.003.

- Meadows, D. 2009. Thinking in Systems: A Primer. London: Earthscan.

- Næss, P., and N. Vogel. 2012. “Sustainable Urban Development and the Multi-level Transition Perspective.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 4: 36–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2012.07.001.

- Nations, U. 2017. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 23 December 2016: 71/256. New Urban Agenda. New York: United Nations.

- Neuman, M. 2005. “The Compact City Fallacy.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 25 (1): 11–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X04270466.

- Niemeijer, D., and R. De Groot. 2008. “Framing Environmental Indicators: Moving from Causal Chains to Causal Networks.” Environ Dev Sustain 10 (1): 89–106. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-006-9040-9.

- O'Brien, K., and E. Selboe, E. eds. 2015. The Adaptive Challenge of Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- OECD. 2012. Compact City Policies: A Comparative Assessment. OECD Green Growth Studies. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Peponis, J., S. Bafna, and Z. Zhang. 2008. “The Connectivity of Streets: Reach and Directional Distance.” Environment and Planning. B, Planning & Design 35 (5): 881–901. doi:https://doi.org/10.1068/b33088.

- Porqueddu, E. 2015. “Intensity without Density.” Journal of Urban Design 20 (2): 169–192. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2015.1009008.

- Rekolainen, S., J. Kämäri, M. Hiltunen, and T. M. Saloranta. 2003. “A Conceptual Framework for Identifying the Need and Role of Models in the Implementation of the Water Framework Directive.” International Journal of River Basin Management 1 (4): 347–352. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15715124.2003.9635217.

- Rittel, H. W. J. :., and M. M. Webber. 1973. “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning.” Policy Sciences 4: 155–169. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01405730.

- Rode, P., G. Floater, N. Thomopoulos, J. Docherty, P. Schwinger, A. Mahendra, and W. Fang. 2014. “Accessibility in Cities: Transport and Urban Form.” NCE Cities Paper 03. LSE Cities. London: London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Rosol, M., V. Béal, and M. Samuel. 2017. “Greenest Cities? The (Post-)politics of New Urban Environmental Regimes.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 49 (8): 1710–1718. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X17714843.

- Rotterdam, G. 2007. “Stadsvisie Rotterdam: Ruimtelijke Ontwikkelingsstrategie 2030 (Rotterdam Urban Vision: Spatial Development Strategy 2030).”

- Rueda, S. 2007. “Barcelona, ciudad mediterránea, compacta y compleja: Una visión de futuro más sostenible.” Barcelona: Ayuntamiento de Barcelona/Agencia de Ecología Urbana.

- Rueda, S. 2014. Ecological Urbanism. Barcelona: Urban Ecology Agency of Barcelona.

- Spanò, M., F. Gentile, C. Davies, and R. Lafortezza. 2017. “‘The DPSIR Framework in Support of Green Infrastructure Planning: A Case Study in Southern Italy.” Land Use Policy 61 (242): 242–250. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.10.051.

- TEEB, (The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity). 2011. TEEB Manual for Cities: Ecosystem Services in Urban Management. Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme.

- The Global Commission on the Economy and Climate. 2014. Better Growth, Better Climate: The New Climate Economy Report. Washington, DC.: World Resources Institute.

- The Urban Task Force. 1999. Towards an Urban Renaissance. London: Routledge.

- Tscherning, K., K. Helming, B. Krippner, S. Sieber, and S. G. Y. Paloma. 2012. “Does Research Applying the DPSIR Framework Support Decision Making?” Land Use Policy 29: 102–110. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2011.05.009.

- UNEP. 2013. ‘Integrating The Environment In Urban Planning And Management: Key Principles And Approaches For Cities In The 21st Century ‘. Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme.

- UN-Habitat. 2012. Urban Planning for City Leaders. Nairobi: UN HABITAT.

- UN-Habitat. 2014. A New Strategy of Sustainable Neighbourhood Planning: Five Principles. Nairobi: UN Habitat.

- UN-Habitat. n.d. A New Strategy of Sustainable Neighbourhood Planning: Five Principles (Draft with References). Nairobi: Urban Planning and Design Branch, UN Habitat.

- Vedung, E. 2006. “Evaluation Research.” In Handbook of Public Policy, edited by B. Guy Peters and J. Pierre, 397–416. London: Sage.

- Wamsler, C., and E. Brink. 2015. “The Urban Domino Effect: A Conceptualization of Cities’ Interconnectedness of Risk, Input Paper.” In Global assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction. United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction.

- Westerink, J., D. Haase, A. Bauer, J. Ravetz, F. Jarrige, and B. E. M. A. Carmen. 2013. “Dealing with Sustainability Trade-Offs of the Compact City in Peri-Urban Planning across European City Regions.” European Planning Studies 21 (3): 473–497. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2012.722927.

- Zhang, Y. 2017. “CityMatrix – An Urban Decision Support System Augmented by Artificial Intelligence.” Masters thesis, MIT.

- Zhao, X., and M. Bottero. 2010. “Application of System Dynamics and DPSIR Framework for Sustainability Assessment of Urban Residential Areas.” Paper presented at the SB10 Espoo: Sustainable Community - buildingSMART, 2010, Espoo, Finland, September 22-24, 2010.

- Zonneveld, W. 2005. “In Search of Conceptual Modernization: The New Dutch ‘National Spatial Strategy’.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 20 (4): 425–443. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-005-9024-3.