ABSTRACT

This paper explores the crisis in our traditional shopping streets driven by the rapid move to shopping online. The paper examines the nature of traditional shopping streets; why physical and local shopping is important; conceptualizes the distinguishing characteristics of traditional forms of retail and online shopping alongside the factors that determine shopping choices; and explores different approaches to shaping the future of traditional shopping streets. Ultimately, it asks, what are the key place-based intervention factors that can help to guarantee a future for traditional shopping streets?

A story to start

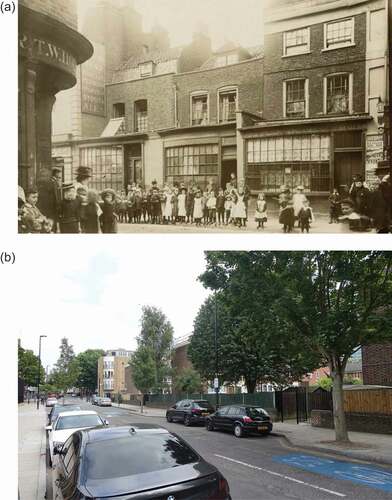

In east London, Poplar High Street stands as a testimony to what happens when a traditional mixed street loses its function. Historic photos show a busy and diverse street, dominated by retail uses on the ground floor and accommodation (probably of very poor quality) above ()). Maps from 1910 show over its 1-km stretch 10 pubs (down from 16 in the 1870s), a bowling green, music hall, public library, vicarage (with church behind), two schools, a council office and a mortuary, all this embedded in a tight-knit urban grain that supported a diverse ecology of retail, small-scale manufacturing, and service businesses.

Later, destruction wrought by the Luftwaffe followed by rapid industrial decline in the neighbouring docks, meant that much of this rich socio-economic and physical ecology never returned ()). Instead, social housing was built, often turning its back on the street, and apart from a few public functions hanging on as civic remnants of its past – the mortuary and bowling green – and a few shops and fast-food takeaways scattered along its length, little gives away its former role as the central social and civic artery of a community. Even the major new ‘public’ function that has been built on the street – a further education college – like the housing, is inward facing and fails to animate the street. Poplar High Street is a ‘high street’ (a main commercial shopping and business street) in name only. It has followed what has been called a ‘canal future’ (Carmona Citation2015, 77); the British canal network having largely lost its original purpose as mechanized transport made rail and then road traffic both quicker and cheaper in the 20th century.

Whilst what happened to Poplar High Street was a consequence of a particular set of circumstances, today, globally, our traditional shopping streets face a similar existential crisis. Their future, when so many of our transactions are no longer place dependent, is clearly in doubt. Will they face a canal future, perhaps eventually to be reinvented as something different (English canals, for example, now support a leisure boating market), or can they adapt and change more rapidly and continue to meet a valued set of human needs?

This paper is a conceptual and speculative piece, based on the heuristic investigation of professional, policy and industry discourse and analysis and of empirical evidence. This analysis informs the first half of the paper in which a ‘sun model’ of shopping choices is conceptualized. The discussion is international in scope, although much of the evidence draws from sources within and reflects on the situation in the UK with approaches taken in England used as a case study in the second half of the paper where three proactive intervention factors are illustrated and discussed. The UK is particularly advanced on its journey away from traditional retail and so the data and policy approaches being explored in the country reveal much about the challenges and opportunities that we might expect as the existential crisis facing traditional shopping streets plays out around the world. By these means, the paper asks, what are the key place-based intervention factors that will help to guarantee a future for traditional shopping streets?

Leaving a movement economy and centrality paradigm behind

Globally, traditional shopping streets often go back centuries, fed by what Hillier (Citation1996) christened the movement economy. As people moved along natural movement corridors, the optimum position of some land parcels in an emerging urban street network allowed the establishment of functions that relied on passers-by and the business opportunities they presented. Over time, these functions were reinforced and commercial streets emerged with some becoming destinations in their own right as the degree of specialization they encompassed encouraged people to travel from further distances to avail themselves of the concentration of services they offered. Others were reinforced by the increasing concentration of service-based industries in central locations (town and city centres), often in and around commercial areas where fairs and markets were held (Harrison Citation2020).

Whilst the growth of car-based urbanization in the second half of the 20th century and of the internet in the 21st has progressively challenged this place-based movement economy, it was the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 that broke it (at least temporarily) in large parts of the world. The year or more of intermittent lockdowns that many countries have endured offered the perfect environment for super-charging the technology-based takeover of many lives. Society quickly found that technology can be used to sustain people in their homes, allowing many to work, shop, eat out (at home), entertain themselves, and even access most public services (including many medical ones) without ever venturing out of their front doors. For many, the weekly physical shop, the commute to work, and the benefits of agglomeration (e.g., being able to do several things together because, for example, the bank was located next to the grocers and over the road from the shoe shop and that nice cake shop), became things of the past.

Figures from the UK’s ONS (Citation2021) show, for example, that e-commerce grew in a single year from around a fifth of total sales to over a third (ONS Citation2021), with Amazon alone adding 10,000 to its workforce as a result of the pandemic-boom, taking its employees to 55,000 across the UK, whilst in the USA and Canada 75,000 are being hired (BBC News Citation2021a). A wide range of services are no longer place dependent leading to an increasing number of families whose incomes are much less tied geographically. In the UK, almost half of UK workers worked from home during the first coronavirus lockdown (ONS Citation2020), rising to almost 60% in London where, at some points in 2020, ridership on the tube fell by 95% (TfL Citation2020).

The trend is global, with a long line of the largest companies (and many more smaller ones) considering their working arrangements, with many coming down on the side of allowing greater flexibility for their office workers (Read Citation2021) who are both demanding more freedom, but also, very often, being more productive for those same businesses during the hours that they work (at home) (Birkinshaw, Cohen, and Stach Citation2020). These trends have the potential to significantly undermine the urban paradigm that has driven growth for centuries, where centrality has often been prized, leading to central business districts with the presence of workers that in turn support the diverse retail, entertainment and eating offerings of many town and city centres.

This fundamental disruption of the previous dependency between place, people and the services on which they reply has been creeping up on cities for decades and some traditional shopping streets had already largely succumbed because of the earlier disruptive technology: the car and car-based urbanism (). Only time will tell if the rapid technology-based acceleration witnessed in 2020/21 marks a permanent shift from the movement economy and centrality paradigm to one in which other factors dictate where once physically situated and now footloose functions such as retail occur. If that is the case, then what are those factors? First, however, it is important to address another critical question …

Why should we care?

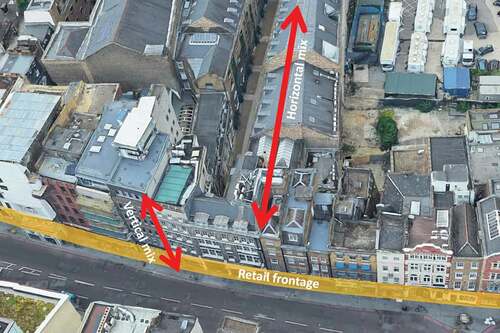

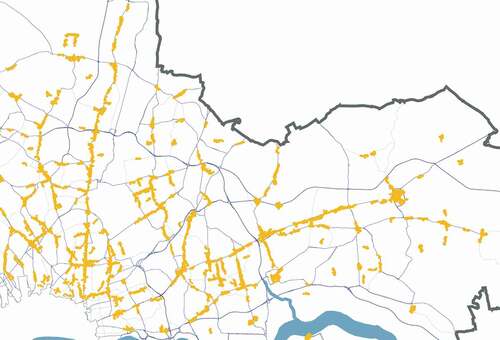

We often perceive high streets (main streets) as places that are all about the shopping. In the UK, the term high street is even used as an adjective for the sorts of shops that one finds in town and city centres. Yet a characteristic that is even more present in many traditional high streets is that they have evolved to become super-diverse places (). In London, for example, small-scale industrial, community and office uses equal the amount of retail within a block depth of the city’s high streets, with residential adding further richness to the mix. Moreover, this rich crust of mixed-use development can stretch for many miles through the city along traditional commercial streets that together accommodate more jobs than London’s Central Activities Zone (Carmona Citation2015; ). Looking across the country as a whole, in 2017 16% of the British population lived within 200 m (one block) of a high street, while retail jobs amounted to only around a quarter of high street employment (ONS Citation2019).

Figure 3. The desirable (often invisible) high street mix (The Geoinformation Group, Map data @2020).

Figure 4. North east London showing the streets with greatest mix – the local high streets – with particular concentrations following the line of Roman roads out of the city to the north and east.

This super-diversity and the rich micro economies supported have been recognized around the world. Examining local shopping streets in New York, Shanghai, Toronto, Amsterdam, Berlin and Tokyo, Zukin, Kasinitz, and Chen (Citation2016, 4) comment ‘If an ecosystem is a complex network with many interrelated parts, all interacting with the surrounding environment, the ecosystem of a local shopping street brings together in one compact physical space the networks of social, economic and cultural exchange, created everyday by store owners, their employees, shoppers and local residents’.

This is nothing new. Long before e-commerce or even out-of-town shopping took off seriously, critiques of postwar planning began to emerge that criticized the forced separation of uses through zoning and other means that actively undermined the rich exuberance of the traditional city and its streets. Jacobs (Citation1961, 155; 162–3), famously, argued that the vitality of city neighbourhoods depends on the overlapping and interweaving of activities, and that understanding cities requires dealing with mixtures of uses as the ‘essential phenomena’. Today, empirical evidence has caught up with Jacob’s informed intuition and a wide range of international research studies demonstrate a ‘very strong’ positive association between place derived value of all types (health, social, economic and environmental) and the mixing of uses, for example leading to lower energy consumption and dramatically reduced CO2 emissions; healthier (more active) lifestyles; and to higher levels of social capital and well-being (Carmona Citation2019). Moreover, access to good quality local shops seems to be particularly important in this, and notably to people’s sense of pride and community, in the UK coming first among the issues that boosts subjective well-being, but also first among those local place factors most in need of improvement (Ussher, Rotik, and Jeyabraba Citation2021).

As the epitome of this mix, where it is arguably the most diverse, longest lasting with the greatest number of interdependencies, traditional commercial shopping streets matter profoundly. They are also where we are most likely to experience another form of mix, the mix of humanity. As Zukin, Kasinitz, and Chen (Citation2016, 1) has suggested, whether we are walking, shopping, taking our clothes to the dry-cleaner, or getting a bite to eat, these are the spaces where we experience everyday diversity”. This diversity comes in the form of the other people around us shopping or otherwise conducting their business, and also in the make-up of the owners of businesses on these streets that frequently reflect the diverse global flows of immigrants to whom urban areas are a magnet and who see opportunity in setting up a shop, restaurant or service, often reflective of their own roots and culture. Exposing citizens to the diversity around them (ethnic, cultural, sexual, religious, etc.) is a key job of the public realm, perpetuating mutual understanding and acceptance. This happens most profoundly precisely where environments are most mixed (Donovan Citation2018).

As the UK data demonstrate, retail uses are only a part of the total mix, which is spread both vertically up the buildings that front onto high streets (e.g., in with offices and residential above the shops), and horizontally into the hinterland of the urban blocks lining high streets (e.g., in with small-scale manufacturing, meeting, office, kitchen and storage uses behind the shops). Retail, nevertheless, remains the ‘public face’ of high streets, often in the form of an active and continuous frontage, and a move away from physical retail will significantly change the experience of these streets, removing and in a sense privatizing previously active frontages.

A case-in-point that pre-dates the current technological challenges is Japan’s ‘shutter streets’, a consequence of the country’s ageing society, inflexible housing practices and the preferences of many for shopping centres over traditional shopping streets (). As the owners of shops age, instead of selling their businesses and moving on, they simply shut up shop, close the shutters downstairs, and retreat upstairs to live out their days. Today the phenomenon is leading to a general lack of investment in many areas, particularly in declining areas with fragmented and complex land ownership structures. The resulting streets feel unfriendly, unloved and undesirable for shopping, living or indeed any other activities (Carmona and Sakai Citation2014).

If the reasons for such a decline are increasingly technological rather than demographic, Reades and Crookston (Citation2021, 217) argue that it is easy to overstate their impact. For them, face-to-face matters and always will: ‘In the end, it’s about the human touch: making time and making contact, even when it might well seem like it’s gone for good. In this context, ICT is the great enabler – we can “reach out” across cities and continents as never before – but it is not the great substitute – Face to face is still integral to maintaining relationships, confidence, and commitment. … Consequently, central places, where contact is easier and quicker, retain a crucial advantage’. Zukin, Kasinitz, and Chen (Citation2016, 6) agree that technology is a two-sided coin. While ‘new technology has shifted many kinds of consumption away from human interaction in brick-and-mortar stores. … good reviews on social media bring new customers to local shops and restaurants. Other apps help small store owners to manage inventory, process credit card payments and create video advertisements’ and, of course, many shops have websites of their own.

At the same time, the penetration of e-commerce technologies reach ever further into the retail market. Beginning with products that had the potential to be digitized (books, music, films), moving to physical but impersonal products such as groceries, and now encompassing highly individualized products, notably, fashion, there are few corners of the retail landscape that remain untouched. It is notable, for example, that one of the largest online players, fashion brand ASOS, saw its sales rise by 25% in just 6 months covering the second period of lockdown in the UK even though its predominantly young market was unable to go out and show off their new clothes (BBC News Citation2021b).

Whilst it has yet to be seen if ‘seeing the whites of their eyes’ in the Zoom window will be an adequate substitute in the post-pandemic world for face-to-face meetings and exactly how workers and companies will choose to divide time between work and home, in the retail world, seeing the product online has increasingly proven to be more than enough for many consumers, leaving the critical question, what are the reasons to visit a shop in person? What seems clear is that if the outlook for traditional shopping streets is not to be a ‘canal future’ akin to Japan’s shutter streets; then, a new basis for support may be required that is not dependent (at least not to the same degree) on movement and centrality

The sun model of shopping choices

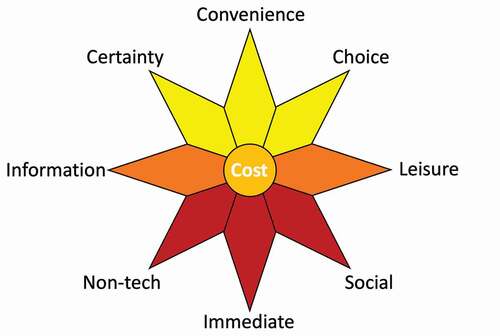

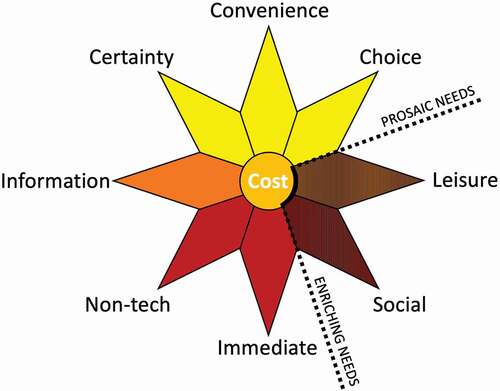

To understand this, it is first necessary to understand the different reasons people choose to make the shopping choices they make. Reviewing professional, policy and industry discourse and analysis from a wide range of international blogs, fora, popular news reports and industry news sites, factors influencing the choices associated with physical and online shopping were explored. Following a heuristic process of distillation, refinement and speculation, nine critical factors emerged which represents in a sun model.

Factors coloured red (on the bottom) strongly inform the choices of physical shoppers and yellow (on top) those who shop online. Shades of orange (in the middle) inform the decisions of both groups, although darker orange is likely to be more important to physical and lighter orange to online shoppers. In this respect factors can be seen as generally advantageous to one or other mode of shopping.

The raison d’être of online shopping, and why it has become such a powerful disruptor of traditional shopping habits focuses on four fundamental ‘C’s.

Convenience, is perhaps the most powerful ‘C’, reflecting the fact that for those with access to reliable digital resources, shopping online has become so convenient (Davy Citation2020) that tasks that previously would have taken hours (e.g., the weekly food shop) are now just a few clicks away and are sometimes instant (e.g., online banking) saving time, cost (e.g., for parking) and hassle (e.g., with mobile payment). This factor is particularly significant for those tasks which can be viewed as necessities – we do them because we have to – rather than optional tasks – which we choose to do because we want to (Beauchamp and Ponder Citation2010). Convenience is perceived at every stage of online shopping – access, search, evaluation, transaction and post-purchase possession (Jiang, Yang, and Jun Citation2013).

Choice, is a double-edged sword. The famous department store Harrods of London has historically marketed itself on the basis that ‘you could buy anything there’ (A-broad in London Citation2019), a claim made possible, at least in part, because of the huge depository it built on the banks of the Thames in Hammersmith to house bulkier stock that could not be stored at its Knightsbridge store. But the reality of any shop, even the largest department store or shopping centre, will be constrained by its physical limits (Bennett Citation2020). That is not a constraint faced by the internet where choice is almost limitless, although at the potential price of indecision among shoppers.

Certainty, is never guaranteed (things go wrong) but while a trip to physical stores will often carry the risk and uncertainty that the product(s) being sought will be unavailable or out-of-stock, on the internet once something is purchased and delivery arranged, shoppers can be pretty certain that they have secured it (Howland Citation2020; Webster Citation2019). Exceptions can be found by using hybrid approaches, notably ‘click and collect’ and new technologies are emerging (e.g., NearSt – Clawson Citation2019) that can bring online stock searching to even the smallest shops, but arguably, once online the battle to encourage physical shoppers into stores may already be lost.

Cost, gives online an immediate advantage because whether online is or is not cheaper than physical shopping, perceptions are typically that it is (Vaast Citation2017). The reality may be more complex, with one of the only systematic international studies on the subject suggesting that price levels are identical nearly three-quarters of the time (Cavallo Citation2017). Whilst online retailers benefit from reduced fixed physical costs – rent, utilities, and so on, human payroll costs, and often from advantageous tax regimes, e.g.,, reduced local taxation, registration in tax havens, etc (Montaldo Citation2021), they have to bear the cost of individualized shipping which, contrary to much consumer messaging, ‘isn’t really free’ (Sumrak Citation2018). Such costs also rise the faster we expect delivery (see below).

The final ‘C’, of course, is always a factor in any purchase decision, and most consumers in both online and physical spaces will need to shop carefully and to a budget. However, in allowing extensive ‘shopping around’ with ease, cost is a more powerful factor driving consumers to shop online than it is in keeping them in bricks-and-mortar stores. Cost is consequently included in this first group of factors.

Turning to the traditional physical shopping environment, three factors remain uniquely influential in helping to retain a physical customer-base, although only the first two are what might be seen as ‘positive’ factors:

Immediate access to goods is only possible when shoppers are able to touch and directly purchase products from physical stores. Whilst delivery times have been dramatically shrinking (1 day as standard for Amazon Prime customers and less than that with a range of same-day shipping apps), even with the most efficient delivery systems, access to products cannot be immediate and deliveries typically take anything from 24 hours to a week or more (if coming from overseas). Moreover, because to squeeze those times further requires a move from massive more distant distribution hubs to smaller, more local ones, faster delivery carries a significant cost (Subramanian Citation2019) at a time when the cost of shipping is the number one reason for shoppers to abandon online carts (Estay Citation2021). As some products (e.g., milk for breakfast) will often be required instantly and some consumers are impatient, in this area physical retail still has an advantage over online, albeit an advantage that is shrinking.

Social, face-to-face interaction represents a major advantage for physical retail over online. Going to the shops has always represented an important social opportunity. From meeting friends, to keeping in touch and sharing gossip, to incidental contact with retail workers and other shoppers, such contact supports personal well-being (particularly for those unable to work), as well as learning and tolerance of others (Dines and Cattell Citation2006). As it makes us feel better about ourselves and others it creates a reason to go out and shop, rather than stay in to do so. From planned meetings – shopping with friends – to accidental encounters, the importance of accessible physical retail became particularly evident during the COVID-19 lockdowns when going to food and convenience shops have been among a minority of sanctioned activities (Carmona et al. Citation2020). The equivalent online – social network driven commerce – while driving huge sales volumes (Statistica Citation2019) has none of the in-person social benefits of contact in the physical world and has been associated with distinct harms (Throuvala et al. Citation2021).

Non-technological, does not strictly apply to any retail formats today when even a humble market stall can be connected via modern technology to international payment systems, social media, online ordering and stock from around the globe. At the same time, physical shops still offer those without technological skills and resources the means to access goods and services traditionally – physically and with cash. There remains a digital divide whereby less well-off, less-connected (e.g., rural) and less tech-savvy (particularly older) groups will have less opportunity to shop online simply because they have less access, or capability, to do so (Gralnick Citation2017; Zhu and Chen Citation2013). While this represents an opportunity for bricks-and-mortar in the short term, it is a negative one in that it stems from necessity rather than necessarily from choice. This will also be a shrinking demographic and therefore not a sustainable basis on which to plan future trade.

Two final factors are, arguably, still more important (better satisfied) in the offline than the online world, but in a less equivocal way:

Information, is a fundamental commodity in retailing, and flows in two directions: from retail to consumer and back again. Even with the most sophisticated product descriptions and viewing systems, some products are still best seen in person and physically rather than via a screen. This might include purchases in connection with which customers need tailored advice or assistance (e.g., technical or fashion advice), are unique or expensive relative to consumers’ spending power (e.g., jewellery), which need to be customized (e.g., a wedding dress), or which in some ways are restricted (e.g., pharmaceuticals). At the same time, online stores will often contain detailed product descriptions and the facilities to directly compare (onscreen) the specifications of products. For physical stores, the ability for customers to see and touch directly is now a critical differentiator (although they still need to capture that sale) along with the personal customer service and assistance that an informed sales assistant can give (Clark Citation2020), and which is rarely available online. This, however, needs to be set against the ability of online to personalize the retail experience by collecting data (over time) on consumers and ensuring that they see products most suited to their needs, purchasing power and tastes (Holloway Citation2017), something almost impossible in the physical world, short of employing the most high-end services of personal shoppers.

Leisure, is related to information as it begins with the way that customers are treated both in-store and online. In an age of infinite options, if shops find it increasingly difficult to compete on price and convenience, they can still score on service. More broadly, as everyday necessity purchases (e.g., the weekly food shop) become increasingly easy to purchase online, freeing up time for other things, the major reason to venture out to the shops is increasingly a leisure one. This may range from simply something to do, to an enjoyable diversion, with shopping linked to allied consumer, cultural or entertainment opportunities with a physical dimension such as eating out or visiting a theatre. For many, including Mary Portas (Citation2011) who was commissioned to advise the British Government, this leisure dimension represents the key selling point for the best traditional shopping streets, and their best chance to survive. It depends, ultimately, on the experience of getting there (accessibility), the quality of the environment once there (amenity) and on the draw of the things to do once there (attractions). It relies on creating the sort of social buzz (animation) that successful places often have (Carmona Citation2021a, 392) and that shopping centres will often attempt to create.

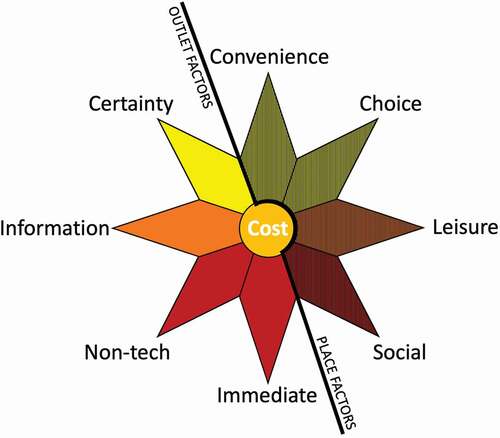

Outlet vs. place factors

Examining the model, it is clear that no single outlet (as opposed to retailer) – whether online or off – can offer everything, and indeed no mode has a monopoly on any of the factors represented in the sun model. Instead, they offer combinations of qualities. At the same time, the areas of greatest strength for online outlets – the four ‘C’s – tend to be very direct and tangible, and against which traditional offline retailers struggle to compete. In this respect, it is no accident that physical retail advantages are reminiscent of a setting sun in the figure, although for the traditional street-based forms of retail, these sorts of challenges are nothing new.

For decades before e-retailing took off, discussions focused around the perceived negative impact of out-of-town retailing on traditional town centres (URBED Citation1994). As an integral component of what Leinberger (Citation2008) christens ‘drivable suburbanism’ the structure and impact of these forms of development have been extensively discussed in the literature. Looking at them physically it is easy to see them as part of a continuum or journey from mixed, integrated and place-dependent urbanism to separated, disintegrated and non-place urbanism () in which the retail boxes set in among their extensive free car parking on the edge of cities offered a stepping-off point towards the same four ‘C’s that define the online retail experience – convenience (for those with cars), greater choice (given the size of many of these units), greater certainty (given the stock on offer) and reduced cost (given their economies of scale, lower rents, and lower overheads) (Furmanik Citation2020).

Figure 7. The journey from mixed, integrated and place-dependent to separated, disintegrated and non-place urbanism.

Arguably all these advantages have been given rocket-boosters in the online world whose sun has been relentlessly rising. So whilst most traditional high streets survived the move out-of-town, that inherent resilience (see below) is no guarantee that they will survive the move online. Whilst early evidence from shoppers in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated a preference for the car parks and larger more spacious footplate formats of out-of-town retail over the more crowded spaces of town centres (Partridge Citation2020), in the long-term it may be exactly their place-based differentiation from the online model that will allow traditional shopping streets to again adapt and survive. By contrast, out-of-town, which is much closer in type to online, could suffer more severely in the ongoing cull of retail. In the UK, pre-pandemic evidence was showing that out-of-town retail was already in a steeper decline than traditional high streets (Grimsey Citation2013, 9), with supermarkets, in particular, having over-extended themselves in their rush for market share and over-building floor space at the same time that online was taking off for food as well as electrical and household goods (Simpson Citation2013; Felsted and Allen Citation2015).

In the US, the decline of suburban shopping malls in the face of the move online over the last decade has been particularly intense (Rosenthal et al. Citation2019). Whilst many have become ‘zombie malls’, others, in order to survive, are having to reinvent themselves in order to differentiate their offer, often by becoming more like traditional town centres. As Bhattarai (Citation2019) reports: ‘Those that are thriving are spending millions reinventing themselves as integrated lifestyle hubs – adding yoga studios, medical clinics and microbreweries – populated with more upscale shops’. She identifies the case of Tysons Corner Centre, the mall at the centre of Garreau’s (Citation1991) famous ‘edge city’ architype – Tysons Corner (now just Tysons). Over half a century this once standard ‘cookie cutter’ mall has re-invented itself many times and now sits at the centre of a neighbouring community of high-rise offices and condominiums, all helping it to move closer to the mixed, integrated and place-dependent model of the traditional high street (albeit still car-dependent). Bhattarai (Citation2019) recounts that it is this that has enabled its survival in stark contrast to neighbouring malls such as Lake Forest in Montgomery County.

This case reveals a further key conceptual distinction when considering the future of physical retailing, relating to the scale at which the factors and associated challenges need to be addressed. shows a distinction between those (on the left) that are predominantly factors determined within individual retail outlets (singular or chains) and those on the right that relate to a particular marketplace – be that the internet at large, or the particular town or city centre that a shopper visits. These can be described as outlet and place factors.

Setting fiscal issues aside such as local and national taxes and incentives that can impact decisively on cost factors, it is within the place realm that the public sector (and large private retail investors e.g., owners of large shopping malls) can hope to influence the future of their particular marketplace and whether, ultimately, they will survive and thrive or decline and die. Outlet factors, by contrast, reflect either the simple realities of the channel used to shop (e.g., you can’t touch things on the internet but you can be certain to purchase most products with a few clicks of a mouse), or are factors determined by the particular retail model pursued by individual operators (e.g., the employment of polite, helpful assistants versus the availability of good technical descriptors online).

Inevitably, as this is a conceptual discussion, there is a degree of simplification in the analysis in order to isolate and understand the key components at play. In reality, factors are not exclusively outlet or place related and increasingly retailers are anyway adopting what might be called hybrid strategies, notably the growth of omnichannel retailers that combine an offer across both on- and off-line worlds. Typically, this has involved traditional bricks-and-mortar stores developing sophisticated websites that allow shoppers to search online and buy or collect in-store. Less frequently, online retailers have opened up physical outlets, with the move of Amazon into physical retail care of its Amazon Go (in the US) and Amazon Fresh (in the UK) stores representing a case-in-point. Elsewhere – particularly post-covid – online retailers have been buying up former bricks-and-mortar brands and offering them exclusively online (Frei and Jack Citation2021). But, just as large traditional retailers are going online in order to survive, they are finding that their need for physical space is reducing, with a rationalization to fewer larger units that are spatially more widely distributed (Khan Citation2021). This means that while huge centres may survive along with smaller local ones, centres in the middle will increasingly find the traditional retail model harder to sustain.

Intervening in place-based factors

Despite the conceptual complexities, the remainder of this paper predominantly focuses on place-based factors as it is these that are most dependent on the manner in which the built environment is shaped as opposed to how individual stores (or websites) are managed. Across the world, public authorities have been considering what will be the long-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the shopping and related work habits of their citizens and what will be the consequences for the way in which urban areas are structured. As has already been suggested, a simple return to the way things were pre-pandemic is unlikely as the disruption of new technology has been embraced by individuals and companies and cannot now be forgotten.

Faced with this, governments (national and local) might adopt one of three strategies:

The Darwinian strategy of letting the fittest survive and natural evolution (and sometimes extinctions) occur through de-regulating and allowing the market freedom to adjust provision in line with consumer choices

An interventionalist strategy in which fiscal incentives, active planning, public investment and collaborative engagement with private interests are used to proactively support physical retail against online competition

A mixed model in which intervention is more limited and focuses largely on smoothing undesirable social and environmental impacts that the market, left to its own devises, fails to address.

Historical evidence from Vaughan et al. (Citation2015, 18) reveals how, London’s suburban high streets have, since the 1880s onwards, been able to adapt and change over time in a more or less natural way. Likening this process to the ecology of a suburban hedgerow, they argue that ‘These historic centres displayed a rich and diverse mix of uses that seem to follow a spatial logic. The diversity has evidently contributed to the long-term social and economic vitality of these places’. This resilience is a feature of many historic shopping streets, and it is hard to escape the observation that for most of their existence, such streets have been largely left to fend for themselves in a manner akin to the first of the strategies above.

At the same time, not all citizens are equally fit, wealthy and technologically savvy and therefore equally able to adapt to whatever the market throws up, particularly if – in the future – that is a world in which the rich ecology of high streets has largely gone online. Indeed, one recent study for the Greater London Authority (GLA) examining the use and social value of high streets in London concluded that high streets are important gathering spaces for marginalized and under-represented groups – job-seekers, elderly people, young people and recent immigrants – and that these streets ‘provide crucial social infrastructure and social services for Londoners’, with almost 40% of small businesses providing some kind of social support that went beyond their core function (We made That & LSE Cities Citation2017). Such a reality supports the second of the strategies above, or what the GLA report describes as ‘The strategic case for intervention’.

A pragmatic argument might be made for the third position, one in which natural evolutionary processes continue to occur, but in which the public sector seeks to protect matters of recognized public importance. A key question is whether, in the light of the relentless (and recently exponential) growth in ecommerce, governments that have been content to adopt a laisse faire approach will now need to re-evaluate. The situation in England is instructive. It is estimated that the country possesses 25% too much physical retail space nationally (Chapman-Cavanagh Citation2021, 62); a legacy from the rapid expansion of the sector from the 1980s onwards that came to an abrupt halt in the 2010s, and a consequence of the country’s leading position in many league tables of ecommerce spend per capita (Frisby Citation2018). The aftermath of the pandemic threatens to move the country permanently from what Napoleon is said to have described as ‘a nation of shopkeepers’ to what is fast becoming ‘a nation of white van drivers’ – delivering packages from the huge warehouses located regionally across the country.

All this means that England reflects a case further ahead than most countries on the journey away from traditional retail, with all the threats and opportunities that this implies for traditional shopping streets. The policy approaches to address this can best be described as confused with competing initiatives seeming to support both the first and second approaches above, although not in a manner that amounts to a coherent attempt at the third.

De-regulation versus coordinated intervention, the English case

The concern for the fate of high streets is nothing new in England, where famous national brands have been collapsing for over a decade with 10 successive years of footfall decline prior to the pandemic (Millington et al. Citation2018). The response from successive governments, and a wide range of other parties, has been the commissioning of numerous reports in order to understand the problem.

The highest profile of these was commissioned from retail guru Mary Portas in 2011 in which she argued for a vision for each street that recognized and celebrated its unique qualities and drove that vision home as if each high street was a business: ‘If the high street was in single ownership, like a department store, it would have a vision, a high-level strategy and direction, it would choose what it wanted in a particular space to fit with a vision and proactively target the businesses and services that were missing’ (Portas Citation2011, 18). Driving this change, she argued, should be Town Teams as a ‘visionary, strategic and strong operational management team for high streets’ bringing together private and public interests to more proactively guide change in a manner similar to a private shopping mall.

At the same time, Portas called for government to ‘include high street deregulation as part of their ongoing work on freeing up red tape’, including of the ‘Use classes’ system that determines when planning permission is required for changes in use between different land use classes, e.g., retail to leisure or offices to industrial uses. However, she noted, ‘I do think there need to be limits. What I really want to see is diversity on our high streets. When a high street has too many of one thing it tips the balance of the location and inevitably puts off potential retailers and investors. Too many charity shops on one high street are an obvious example of this. Funnily enough, too many fried chicken shops have the same effect’ (Portas Citation2011, 29). The tension between deregulation and intervention has become particularly acute in the pandemic and post-pandemic era.

De-regulation – Ad-hoc renewal

More politically potent than the high street crisis has been the housing crisis in England, with the ambitions of successive governments to deliver significantly more new housing consistently coming up against a housing development market unable to deliver the numbers required (Stratton Citation2019). The causes and consequences of this are beyond the scope of this paper, but part of the solution in recent years has been a sequence of liberalizations to the Use classes system through the granting of increased permitted development rights (PDR). Among other things, these extended rights now allow the conversion of redundant retail and offices to residential without the need for planning permission, reforms that have brought forward 72,687 homes over the 5 years to March 2020 (MHCLG Citation2021), albeit too often at a quality that has been assessed to be substandard (Clifford et al. Citation2020).

Undaunted, further liberalizations in March 2021 gave PDR rights to all properties in Class E of the Use Classes Order allowing conversion to residential use. Class E is a new mega-class introduced in September 2020 that contains all commercial, business and service uses, from creches, to high street shops, to offices, to financial services, to gyms, to restaurants, to retail sheds. In other words, the majority of the city that is not already residential and the majority of high street uses. By allowing (almost) unregulated change of all these uses to residential, the reform, in effect, returns high street land uses to their pre-planning system unregulated state, as long as the change is within the curtilage of the existing buildings. The move has raised questions about whether this is a sensible liberation bringing long-needed flexibility to urban areas or a misguided attempt to overcome failures in the housing market via the back door.

The UK Government’s justification for the proposals was based almost entirely on the need to tackle the crisis on England’s high streets rather than on its housing stock (MHCLG Citation2021). In a context where the pandemic and the move online has cut large swathes through the UK’s physical retail industry (Clark Citation2021), with some predicting 25% vacancy across the country by the end of the decade (Clapson Citation2021), the Government argued that allowing more housing in such locations will diversify uses and help to support retail through having larger populations within walking distance. A side effect, however, is the removal of almost the only (albeit crude) mechanism (short of public sector ownership) for local authorities to ‘direct’ an appropriate mix of uses in town centres and high streets – the diversity called for by Mary Portas.

The change reflects a political belief that allowing the flexible adaptation of buildings is always a good thing, and the market should be given the freedom to deliver. As Clapson (Citation2021) agues, ‘While it may sound counter-intuitive, the secret to achieving this revitalization of commerce, is to make town centres more residential. … Historically, this residential development has been difficult due to strict planning regulations. To turn a derelict department store into apartments, for example, would require planning permission from the local planning authority, which are usually notoriously underfunded, overloaded and often bureaucratic’. While more housing (and therefore customers) in retail areas sounds attractive, Carmona (Citation2021b) suggests that the reality is more complex:

Contemporary market processes don’t, by themselves, deliver mixed-use as they once did. Instead, most developers specialize in single forms of development whilst many property investors will favour what is in their short-term – most profitable – interests. In England, for the foreseeable future, both tendencies are likely to favour the production of housing rather than other uses.

Real flexibility should be a two-way street, but not all uses are equally flexible. Once units and buildings have been converted into housing, particularly if in multiple ownerships as would typically be the case for larger high street buildings, it becomes very difficult to flex them back to something else or to redevelop them. In this case, the proposed new PDR rights are also one-way, everything to residential, but not back the other way; arguably the antithesis of flexibility.

A first danger, therefore, is that, crudely done (aka without forethought or planning), deregulation might reduce the very diversity that it seeks to inject. That is because, given the choice between the uncertainties of a retail industry in crisis, an office market also in transition (as more white-collar workers work – either part-time or full-time – from home in the future), and the low values associated with small-scale manufacturing and community functions, the logical approach for investors will be to run to residential as soon as they are able. Housing is simply much more profitable than anything else, both now and for the foreseeable future. The situation could all too easily become reminiscent of many rural villages in commuter areas that have gradually become stripped of all functions apart from housing (Philby Citation2011) – a particular form of ‘canal future’.

Chapman-Cavanagh (Citation2021, 63) note that ‘Converting retail to residential is not the sole solution, and it is vital that such developments seek to work collaboratively with existing retail spaces, as well as bringing in new vibrant spaces to animate ground floors and shopfronts. A mixed economy, with the right balance of residential and high performing retail, is key’. Intervention, as the alternative to deregulation, however, is far more complex, cutting across the realms of planning, design and curation.

Intervention – shaping through proactive planning

Beyond its deregulation instincts, the UK government has, half-heartedly, at first, but with increasing urgency encouraged a more active and interventionist approach to the nation’s high streets. Following the Portas review, small grants from a £1.2 million fund were made available to 12 local authorities (from over 400 who applied) to set up and run ‘Portas Pilots’ to ‘enable town teams to develop a self-sustaining local vision for their area to meet their long-term outcomes’ (DCLG Citation2012a). Later, the fund was increased to £5.5 million (DCLG Citation2012b) with a promise that ‘No high street should be left behind’. Eighteen months later, just 27 local authorities had received grants of up to £100,000 as Portas Pilots, while a further 333 received smaller grants of up to £10,000 to help launch a town team. While other small funds were also made available – a £10 million High Street Innovation Fund (across 100 councils) and a £1 million High Street Renewal package (benefitting 7 towns), an evaluation of the initiative concluded that the results were limited and half-hearted given the challenges needing to be addressed (Neky Citation2013).

An alternative review led by retail industry heavyweight, Grimsey (Citation2013), concluded that when set against an industry that, at the time, comprised some 95,000 companies, employing £326bn of gross assets, with a total net worth of £135bn Government efforts were little short of ‘window dressing’. Instead, Grimsey argued for a radical re-structuring of high streets away from shopping, and towards becoming community hubs, incorporating health, housing, education, arts, entertainment, business/office space, manufacturing, leisure, and some shopping, all networked together with real-time information flows between businesses and users allowing traditional bricks-and-mortar businesses (like online ones) to benefit from the opportunities provided by 4G (and now 5G) technology.

If Grimsey’s central argument was correct that Portas had failed to get over to the UK government both the scale and likely impact of the changes to the retail industry; then, over the decade that followed with retail collapses piling up, the message increasingly got through. In 2018, interim recommendations from a High Street Expert Panel (Citation2018) established by the Government and led, this time, by retail entrepreneur Sir John Timpson recommended the provision of funding for resource-strapped local authorities who had a viable vision in place for their high streets and town centres but lacked the means to implement it. The Future High Streets Fund was set up with £675 million to renew and reshape town centres and high streets (UK Government Citation2019). In July 2019 this was increased to £1 billion, of which £830 million had been allocated by the end of 2020 across 72 areas and £107 million allocated to support the regeneration of specific heritage high streets. Following the COVID-19 lockdowns of 2020 and 2021, an additional £106 million was added to assist streets in re-opening in a safe manner while local business rates were reduced to zero for a year to help stem what Grimsey had characterized as the carnage on the high street.

Together the step-change in resourcing (from 1s to 100s of millions of pounds) demonstrates the urgency with which the issue rose up the national agenda, although with little steer about what that might mean locally, with funding tending to focus on limited one-off capital projects such as improvements to rail stations, public realm improvements, cultural venues, etc., rather than for the complete re-evaluation and perhaps even the repurposing of high streets as recommended by Grimsey. One of the more comprehensive was Nuneaton, in the West Midlands, a medium-sized town centre that had experienced a drop in footfall of approaching a third between 2009 and 2018 (pre-pandemic). Responding to the crisis, a Board made up of public and private stakeholders put together a prospectus of 12 projects ranging from upgrading digital infrastructure, enhancing visitor and cultural attractions, upgrading links, gateways and green spaces, installing e-charging for vehicles and opening up sites for residential use (Nuneaton & Bedworth Borough Council Citation2020).

In 2018, a second Grimsey report argued that every town centre should have a dedicated plan. In this the core retail area should be defined and protected whilst retail in secondary areas should be allowed to shrink, primarily through allowing conversion or redevelopment to residential uses but also through active relocation when requiredfor example, moving valued local retailers from secondary to primary streets (Grimsey Citation2018, 27). As well as avoiding making the holes in the retail frontage permanent – for example, through ad hoc conversion to residential uses – Maccreanor Lavington et al., (Citation2014) note that planned shrinkage can encourage an associated intensification in the use of the frontage that remains, including by building residential over and behind retail ().

Rather than deregulation, such a strategy would rely on regulatory tools such as the Use Classes Order in England, alongside more proactive planning, public/private partnership and potentially land and property assembly and development. It would benefit from the well-established trend of a growing population living within walking distance of high streets across England, where between 2012 and 2017 this population increased at double the rate of other locations (ONS Citation2019). In other words, the opportunity of increasing the residential population already exists and is not dependent on deregulation.

The strategy also reflects basic retail planning shibboleths focused on the agglomeration of allied uses and passers-by (BDP Citation2002). A cake shop on a traditional high street will rely on customers popping in on a whim as they pass by to get to the fashion retailers and the bank. If banking and fashion retailing withdraws to be replaced by residential uses; then, despite the new apartments containing a fair share of cake eaters, the loss of passing trade will be unlikely to support the cake shop. Rather than a gap-toothed look to once traditional shopping streets a planned approach would seek to fill the gaps by concentrating uses in a coherent manner (Hopkirk Citation2020). At the same time, some streets may already have declined too far. In such cases, the reasonable and proactive thing to do may be to abandon any restrictive use class designations and instead to allow, even encourage, all appropriate conversions, whilst seeking to protect a basic range of essential local services (see ).

Intervention – shaping through proactive design

Beyond a proactive strategic vision for declining high streets, international evidence suggests that the more appealing streets are physically, the more conducive they are likely to be as locations where the social, economic and even cultural life of the city will flourish and where populations will be healthier and perhaps even happier and more engaged with their local community too (Dumbaugh and Gattis Citation2005; Engwicht Citation1999; Frank et al. Citation2019; Hart and Parkhurst Citation2011; Carmona Citation2019). The danger is that as societies move to a post-covid world, consumers will be tempted to move permanently back into their cars in order to avoid mixing with others. Despite huge drops in carbon emissions in 2020 (Le Quéré, Jackson, and Jones Citation2020) evidence in the UK suggests that this has happened with huge dips in public transport ridership (Bird, Kriticos, and Tsivanidis Citation2020), with housing markets suggesting a favouring of suburban over urban forms (Hammond Citation2020) and the car industry reporting steady growth in sales (Paul Citation2020). Not only would this exacerbate another longer-standing health crisis – the obesity one (Booth, Pinkston, and Carlos Poston Citation2005; Ewing et al. Citation2008) – but would put a further nail in the coffin of many traditional shopping streets if out-of-town rather than town centre shopping is once again favoured by consumers.

Only time will tell how populations will behave over the long term, although evidence from earlier pandemics shows that social distancing is quickly abandoned as illness fades and normal social life resumes (sometimes too soon – Strochlic and Champine Citation2020). More significant than fears over social distancing is likely to be the move to working (at least part-time) online, potentially offering a lifeline to many local shopping streets in predominantly residential areas whilst complicating the recovery of larger towns and city centres. Early evidence from how different locations faired during and in the early aftermath of covid-related lockdowns in the UK shows that smaller multi-functional centres did much better than larger ones: ‘These district or neighbourhood centres have been rediscovered through COVID-19. Essential retail and greenspace have been the nation’s lifelines during lockdown and these humble high streets would benefit from more recognition and support through national, regional and local policy’ (High Streets Task Force Citation2020).

Whether competing against online or out-of-town, and whether large or small, perhaps the key advantage that traditional streets have over their rivals is in the social and leisure experience they offer to users beyond the act of actually shopping. Gehl (Citation1996) famously distinguishes between necessary, optional and social activities in the use of public space which reflects the idea that for people to really engage in places beyond just passing through because they have to, they need to want to do so because the place is conducive to lingering. The sun model () can be interpreted similarly, with more prosaic factors associated with purchasing what we require: cost, convenience, certainty, choice, information, immediate and non-tech set against the higher order enriching factors: social and leisure, related to the very human desire to be together (). Of particular importance in these areas is the quality of the experience as dictated by the quality of the environment within which shopping occurs.

Pre-pandemic research for Transport for London strongly confirmed this association (Carmona et al. Citation2018a, Citation2018b). By comparing high streets that had been subject to significant public realm redesign and improvement to those that had not, the work identified that improvements to the quality of the publicly owned and managed street fabric returned substantial benefits to the everyday users of streets, and to the occupiers of space and investors in surrounding property in multiple ways, not least in almost doubling active (e.g., walking) street behaviours and tripling leisure based static activities (e.g., stopping at a café or sitting at a bench), leading to stronger rental demand in retail and office rental markets and to 216% hike in the sorts of leisure based static activities (e.g., stopping at a café or sitting at a bench) 216% hike in the sorts of leisure based static activities (e.g., stopping at a café or sitting at a bench) and to reduced vacancy.

Collectively, the findings suggested that to have the most impact, viewing potential projects in terms of a hierarchy of interventions would be beneficial. The most important level of intervention, and the foundation for everything else, should involve improving the pedestrian experience by making adequate space for pedestrian movement and activity. Next, came the enhancement of social space, notably the creation of attractive and comfortable space for sitting, people-watching, socializing and so forth. Finally, came interventions relating to the creation of environmentally unpolluted (sound and air) and more adaptable spaces that can be used in multiple ways with a good interplay between the street and ground floor frontages. Repeated in the world of the 2020/21 COVID-19 pandemic, the final factor – adaptability – would, no doubt, have gained even greater significance, reflecting the need for shopping streets to flex and reallocate space in order to facilitate social distancing.

If the pandemic has marked a one in one hundred-year health emergency; then, it also has the potential to mark a sea-change in how streets are designed and used. In a letter to London’s 33 Boroughs in the summer of 2020, for example, the UK Government offered funding to make emergency (temporary) interventions in the city’s high streets, but supplemented this with the following advice: ‘We have a window of opportunity to act now to embed walking and cycling as part of new long-term commuting habits and reap the associated health, air quality and congestion benefits’ (Furness Citation2020). The changes that followed have sometimes been short-term and temporary, designed primarily to deal with social distancing in traditional streets unsuited to such requirements (). Others have been longer-term and permanent, amounting to an investment of significant new funds in walking and cycle infrastructure for what is described as the creation of a ‘new era of walking and cycling’ (DfT Citation2020) (), both activities proven to boost spend in shops (Living Streets Citation2014).

Intervention – shaping through proactive curation

Whilst the quality of the built environment can help to retain users – enabling them to linger longer – ultimately it is the mix of functions (retail and otherwise) that attracts them. In this respect, Zukin, Kasinitz, and Chen (Citation2016, 1) argue that ‘local shopping streets are the most taken-for-granted spaces on the planet’. Carmona (Citation2015, 5; 9) notes that ‘neglect of such complex spaces among local policy-makers, businesses, and development and management professionals are universal’, implicit in which is the fact that mixed commercial streets are ‘the most complex of street types, with responsibility for their management widely dispersed among a complex web of public and private stakeholders’. Typically, no one has the responsibility (or at least the necessary control and authority) for shaping such streets as coherent multi-functional places.

This represents a major challenge for traditional shopping streets when, their competition – internet platforms, shopping malls and even out-of-town retail parks are highly curated in order to optimize the experience of shopping, from its convenience, to the choice on offer, to the experience of navigating those choices. To complete, Chapman-Cavanagh (Citation2021, 63) argues that ‘The future high streets will need not only to be places people want to live, but also places people want to visit … Socially dynamic places where people can convene and form communities will be of utmost value, as we move away from full-time office environments and traditional physical shopping declines’. Likewise, Abrahams (Citation2021) comments that, in order to survive, ‘the high street will need to find new purpose in becoming the latest arena for customer experience innovation. There are things people do not want to sit at home and wait for, and experiences they do not have the skill or time to create themselves – a quick round of indoor golf, or some axe throwing to alleviate the tedium of a wet week day! Retail owners of prime real estate need to make their business models capitalize on this. Give people a reason to go to the shops and they will do so’.

This notion of experience retail is not new and links to the wider progression in advanced economies from commodities, to goods, to services to experiences (Pine and Gilmore Citation2011). Relating to enriching social and leisure needs (see ), for Saunders (Citation2019) this is why brands continue to need physical space. Thus, while in the early days of ecommerce bricks-and-mortar stores ‘were seen as “showrooms”, victims of a new “ROPO” (research offline, purchase online)’, the most forward thinking retail companies have shifted from being spaces to house products for sale, to spaces for transacting experiences which, when executed well, can drive higher sales. Extrapolating to the scale of the street as a whole, the street now also needs to be part of that positive experience.

This is a lesson that many of the corporate owners of large shopping malls have long understood where the total experience is carefully curated to ensure a mix of retail, entertainment, event spaces, and restaurants in order to keep users coming back and to encourage movement around the mall in a manner that optimizes spending (Carmona Citation2021a, 386). The thought of giving up control on the mix and incorporating non-active uses into it as suggested by the de-regulatory (PDR) changes impacting on English high streets would be an anathema. Whilst Town Centre Management, in various guises, and Business Improvement Districts (BIDs) have developed in an attempt to transfer the private sector methods to publicly managed streets, the reality of fragmented ownerships, limited powers and resources and a lack of focus in the public sector on the growing threats to traditional high streets have combined to limit their impact (Otsuka and Reeve Citation2007). In the rare circumstances that streets are maintained in a single ownership, a far greater degree of control is possible. Marylebone High Street, in the heart of London, offers a case-in-point where ownership of the real estate largely in the hands of the Howard de Walden Estate has allowed it to be minutely curated to become the centre of the self-styled Marylebone urban village, featuring a diverse offer of boutique-independent stores mixed with upmarket chains.

For streets without the same advantages as Marylebone High Street, the future ‘experience’ will need to look beyond retail to facilitate the enriching leisure and social. Chapman-Cavanagh (Citation2021) notes for example, that London’s ‘next generation high street needs to consider three challenges: reconnect people in communities, drive footfall and enhance business for remaining retail, and fix wider issues connected with the housing shortage and environmental crisis’. In other words, a vision of a high street not as a separate place but instead as part of a larger community with a ready-made catchment of users both around and connected to it, and on it. He went on to observe that ‘Aside from residences, repurposing empty shops for wider leisure use will be key. Restaurants, community spaces, pop up markets, gyms and entertainment and art spaces can all provide an economic boost while being a great social cohesive. Co-working spaces, such as those within our co-living developments, are also expected to thrive post-pandemic’.

A decade ago, Portas (Citation2011, 14) concluded that ‘High streets must be ready to experiment, try new things, take risks and become destinations again’. In most traditional shopping streets, the responsibility for this will fall on the public sector and associated public/private vehicles for managing these streets. Although regulatory powers are limited in the UK, the public sector remains a significant provider of social and health services, as well as of sports, fitness, education, cultural, governmental and leisure services, all of which spent the 1980s and 1990s moving to larger consolidated out-of-town locations, but which can be moved back onto the high street (Carmona Citation2015, 76). Others argue that now is the time to encourage manufacture or ‘making’ back onto high streets using both advanced technologies such as 3D printing (University of Exeter Citation2021), but also old technologies such as crafts and those that can support a circular economy, such as shops that specialize in mending and repurposing (Urquhart Citation2017).

In reality, making never went away as the all-important urban block hinterland behind retail frontages has continued to support a diverse range of light industrial activities from car repairs to food manufacture and preparation (Carmona Citation2015, 52). Whilst this hinterland is often poorly understood and ignored by local authorities, its role adding to and supporting the mix should not be forgotten in attempts to facilitate a sustainable mix. Indeed, a key characteristic of this hinterland is its messy, unordered and very mixed nature. Research examining the nature of high streets in London noted ‘Buildings typically relate well to the high street, but only casually to adjacent buildings, and rarely across the street. The blocks show a strong ability to accommodate change, with mixes of uses (and even the built fabric) that are dynamic and constantly changing. In being adaptable, the buildings on the street frontage are generally more robust and longer lasting, while buildings behind are more transient and often temporary in nature; the combination of which allows for both continuity and change’ (Carmona Citation2015, 49) (see ). Both the adaptability of spaces on the street and the messiness of spaces behind can be exploited if properly understood and factored into curatorial strategies. This potential has been recognized in wide-ranging guidance commissioned by the Mayor of London (Citation2019) and designed to encourage local authorities and others across the city to develop mission oriented ‘Adaptive strategies’ focused on the place-specific challenges of particular streets.

Whilst the public sector, typically, has direct control of only a limited stock of buildings in most town centres, it does have control over the public realm, and alongside designing and managing it to ensure it remains a pleasant place to visit, local authorities can (along with private partners) deploy temporary uses in the public realm in order to curate the experience, ranging from fun activities (e.g., events, fairs and demonstrations) to retail opportunities (e.g., farmers markets), to works of art and performance. More proactive English local authorities have, in the past, invested in the retail stock in their town centres in order to give them a stake in how it is managed, and increasingly councils are stepping in to pick up retail assets from investors wishing to divest their investments as the retail market declines. Sometimes this occurs on a relatively small scale, the London Borough of Hackney, for example, buying into mixed use developments in order to repurpose retail space to better serve local needs (e.g., as affordable workspace) or otherwise to ensure a better balance of retail and other outlets across the Borough (Mayor of London Citation2019, 140). Elsewhere, councils are taking on whole shopping centres such as in Blackpool or Bolton as part of larger regeneration plans designed to safeguard their town centres (Clark Citation2019).

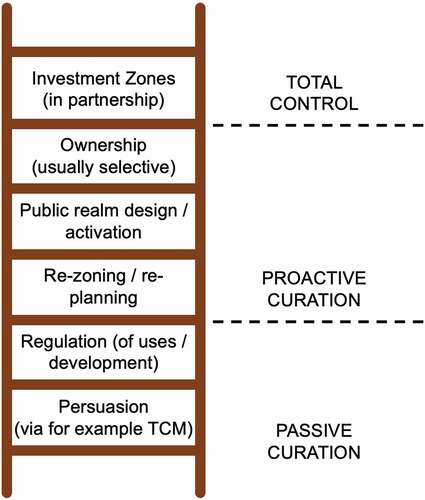

More dramatically, local authorities can seek to turn management arrangements on their head through models such as Town Centre Investment Zones (TCIZs) that have been mooted but so far not adopted. Under these arrangements, local government would partner with private investors within a town in order to pool ownerships and responsibility in a single investment vehicle so that a strategic vision can be developed and driven through that is in the interests of all parties. To make it work, the compulsory purchase powers of the public sector would be critical in order to deal with unwilling landowners (BPF Citation2016), allowing the planned reduction of retail footprint to be managed systematically and coherently with the resulting retail core curated in a manner that would never be possible in a world of fragmented ownerships and competing interests (Peace Citation2021).

Together, the range of different approaches can be represented on a ladder that moves from passive approaches to curating retail environments (the normal approach in England) to more active ones, to total control models (). This total control is something that online retailers can achieve as standard, at least in-so-far as they are able to totally design and guide shoppers through their online sites in a manner that suits them and engages customers; although those same customers have to surf the wider web to find individual sites, travelling through virtual spaces that are controlled by the world’s tech giants with their own agendas and means to waylay those with money to spend.

In the physical world, total control can only be achieved within individual outlets which can be expertly curated in order to guide and seduce customers. Clark (Citation2020) notes that physical retailers have an advantage in this respect because, through the process of guiding customers around stores, shoppers are able to discover unexpected items whereas online they tend to search directly for what they are interested in, although of course websites have many sophisticated means to bring you into contact with other items as you shop and, just like physical retailers, to up-sell. Beyond individual shops, typically only the privately owned and managed environments of larger shopping malls or out-of-town retail parks have the necessary control to achieve total curation of shopping environments, indeed Davy (Citation2020, 28) observes ‘the ability of shopping centres to bring together different elements of a shopping experience clearly trumped the Wild West of the high street and it may well do so again as we show our financial appetite to spend money on “experience over product”’.

What is clear is that the transformative move from conventional retail, which has often been criticized as a bland and cloned experience from street to street (New Economics Foundation Citation2005) is unlikely to attract shoppers in the future. Davy (Citation2020, 28) envisages that this retreat of retail ‘could be replaced by the advance of spaces for lifelong learning, for cultural experimentation, places for debate and knowledge exchange, for social services to re-engage with people, for cultural organizations to come out of their museums and galleries and into the high street. Schools, colleges and universities should have outposts as should larger businesses’. However, none of this will happen without collaboration, partnership and leadership to show the way.

Proactive planning, design and curation, an example

For high streets to survive and thrive in a post-covid world of burgeoning ecommerce will necessitate the public sector drawing on the combined tools of planning, design and curation. There are examples where this is occurring, sometimes through smart governance and sometimes with a big dose of luck thrown in. One such case is Eltham High Street in south-east London, a largely unremarkable street of local significance serving a mixed catchment and designated in the London Plan as a third tier ‘Major’ shopping street. As a town centre, it has no dedicated town centre management, BID or other management entity, and virtually no presence on the internet beyond the websites of constituent stores.

In common with many such streets, it has suffered from a wave of closures, including, since 2018, its TSB bank branch, Debenhams department store (the last of three department stores to close on the street), and chain stores (e.g., Game, Carphone Warehouse, 99p store, Bonmarche and Moss Bros). Numerous local names have also succumbed. At the same time the council has worked to bring new life to the high street by intervening in its mix of uses. On the site of an earlier closed Cooperative department store, it built a Vue cinema and small restaurant complex (), whilst a decade earlier it had built a new multi-purpose fitness centre with swimming pool and library on the high street, at a time when others were still being moved away. The move cleverly anticipated and supports the turn to leisure and away from everyday retail. At the same time, the public realm has been completely redesigned, including widening pavements, removing parking from much of the street, creating a new public space in the centre of the street (), installing new bike lanes and seating, better lighting and signage along its length.

Figure 15. A new public space at Passey place gives heart to the high street and provides a place for events and activities.

Both sets of changes have helped to attract (pre-pandemic) a series of new physical retailers, including national chains (e.g., TK Max and Poundland) that have been able to buck the national decline, and a range of new independent retail and entertainment operators, notably an escape rooms, soft play centre, a new pub, a butcher and monthly producers market. The street has also been bolstered by the development of higher density residential apartments at its western end () and new supported living apartments at its eastern end, both located in marginal secondary retail locations, with more planned in the hinterland behind the main retail frontages. Not everything was planned, and indeed the council originally opposed the western blocks, but that aside, proactive planning of secondary retail locations is continuing to attract new residents who, in turn, will support the retail and entertainment facilities.

So far, the proactive planning, design and curation has managed to keep the high street alive, although many of its remaining chain stores (Marks and Spencer, Argos, Prezzo and Peacocks) remain vulnerable given the consolidation of the businesses of which they are part. In this case, like so many others without any particular locational advantages, the best endeavours of an engaged and active local authority may not be enough.

A place attraction paradigm to conclude

According to MacCormac (Citation1996, 307), traditional shopping streets are: ‘rather like coral reefs that are re-inhabited over and over again’. In the right macro-environment, they are hugely diverse, self-regulating and resilient, but change the environment too quickly or to radically (the temperature of the water in the case of the coral, the move online in the case of a high street) and that resilience quickly breaks down. As the increasing number of ‘canal future’ high streets across the UK (as elsewhere) show, it seems that it is considerably easier to undermine that rich diversity than to build it.

Today, traditional shopping streets (alongside physical retail more generally) face an existential crisis, and how they react will determine whether they have a long-term future as retail destinations or whether, like the English canals, they will need to radically reinvent their future and become something else. This paper explores the nature of shopping streets historically and today and how that is changing in the face of the onslaught from online retail and, to a lesser degree, out-of-town physical alternatives. It has examined why physical and local shopping should remain important to us and has conceptualized the distinguishing characteristics of traditional and online forms of retail alongside the nine factors that determine shopping choices. Using the English case, which is particularly advanced on the road from traditional to online retail, it has explored different approaches to shaping the future of traditional shopping streets. At their simplest, these can be summarized as a choice between deregulation (let only the fittest survive) and coordinated intervention encompassing proactive planning (including investment), design and curation.

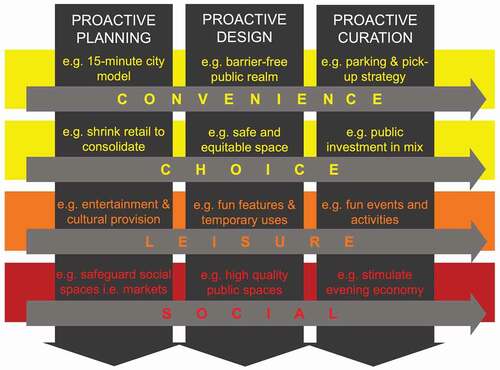

Drawing from the most recent policy, industry and practice discussions that have been used to evidence the analysis, it is possible to conclude that governments, local governments and those with management responsibilities for these streets need to systematically consider their response to the four critical place-based shopping choice factors contained in the sun model explored in the first half of this paper (). Setting these against the three proactive intervention factors discussed in the latter part () begins to answer the question posed at the start, what are the key place-based factors that will help to guarantee a future for traditional shopping streets? In essence, success will require: