ABSTRACT

In this novel study, a gender audit was conducted to assess how the Seoul (Metro) and Jakarta (MRT) subway systems respond to women’s needs. The audit revealed that both Seoul Metro and MRT Jakarta have made significant efforts to accommodate the needs of all passengers, including women. This is commendable because a public transit system that works well for women works better for everyone. With some improvements, both subways could achieve Universal Design standards. The audit protocol developed can be employed to periodically monitor other subway systems in Asia and measure progress towards gender mainstreaming.

Introduction

There is little doubt that transport use is gendered. Women have markedly different travel patterns and needs than men (Delbosc Citation2012; Loukaitou-Sideris Citation2020; Hanson Citation2010; Pojani Citation2014; see also Pojani, Sagaris, and Papa Citation2021). They also face many cultural, economic, physical, and physiological barriers when navigating the city (Moser Citation2005). A comprehensive summary of these barriers, both explicit and implicit, has been provided by Loukaitou-Sideris (Citation2020) (see ). Some barriers are longstanding, whereas others have resulted from evolving gender roles and the inclusion of women in the workforce (Chowdhury and Ceder Citation2016; Gardner, Cui, and Coiacetto Citation2017). Either way, they harm individual women and hamper global efforts to achieve urban sustainability.

Table 1. Barriers affecting women’s travel.

Studies focused on public transport have found that many systems fail to cater to all genders. Many women are hesitant to use buses and trains, which are, or are perceived to be, unsafe (Gardner, Cui, and Coiacetto Citation2017). Fear of crime and sexual harassment leads women to modify their travel behaviour, e.g., by travelling with a companion, not travelling at night, or avoiding public transport services altogether. Stress, a lack of access, and overcrowding are other factors that deter women from using public transport (Chowdhury and Ceder Citation2016; Gardner, Cui, and Coiacetto Citation2017). Nonetheless, many women depend on public transport, having limited physical or financial access to other modes such as private cars, taxis, motorcycles, or bicycles.

Planning systems in both the Global North and South – as well as supranational organizations – are beginning to recognize gender issues in the city. Accordingly, several guidelines, policies, and programmes have been designed to address gender equity in transport (Asian Development Bank Citation2013; Sida Citation2017; TRANSGEN Citation2007). But, before any intervention can occur, cities must conduct gender audits of their transport systems. The purpose of a gender audit is to elucidate the factors that undermine women’s mobility and perpetuate disparities (Conteh Citation2016; Hamilton and Jenkins Citation2000). In the case of public transit, a gender audit involves the assessment of the performance of a system against contemporary best-practice examples (Hamilton and Jenkins Citation2000). While gender-focused audits may have been conducted in the past, no results have been published to date. Therefore, very little information is available on the gender performance of the various transport systems.

In this novel study, a gender audit was conducted to assess how the Seoul and Jakarta subway systems respond to women’s needs. The authors chose to audit rail transit – as opposed to buses or BRTs – because rail has the highest performance, capacity, speed, and reliability of all public transport modes. It is also the costliest to build and, given the public investment, it is expected to benefit society at large. The two case studies were selected to represent a balance of similarities and differences. Seoul and Jakarta are national capitals and megacities of more than 10 million inhabitants each. The respective nations, South Korea and Indonesia share a similar East Asian culture, with gender values, traditions, and hierarchies broadly aligned. And in the past 30 years, both Seoul and Jakarta have faced enormous urbanization pressures which have strained their planning systems (Pojani Citation2020). As for contrasts, prevailing religious practices – Buddhism and Confucianism in South Korea and Islam in Indonesia – pose differing barriers to women’s mobility in each city. Seoul’s subway system is older and denser, while Jakarta’s system is new and considerably smaller. Finally, private incomes and public revenues are significantly higher in Seoul than in Jakarta.

A gender audit of subway systems has never been conducted in large Asian cities before, despite a suite of gender mainstreaming guidelines that organizations such as the World Bank, the ADB, and GIZ/GTZ have produced over recent years (Allen Citation2018; Asian Development Bank Citation2013; World Bank Citation2010). At most, surveys to measure operational performance and commuter satisfaction rates have been conducted (Dahlan and Fraszczyk Citation2019; Kim et al. Citation2014; Shin et al. Citation2021; Putranto and Tajudin Citation2020). A qualitative assessment of the physical design of transit systems has been missing until now.

This study aims to help Seoul and Jakarta improve the travel experience of local women and other vulnerable groups (Hanson Citation2010; Hamilton and Jenkins Citation2000). The audit itself is one of the core contributions of the study. Beyond the case studies, the audit protocol developed is another original contribution. After some adaptation to suit local contexts, it can be employed to monitor other subway systems in Asia periodically and measure progress towards gender mainstreaming.

Methodology

Case studies

A succinct overview of Seoul Metro and MRT Jakarta is provided below.

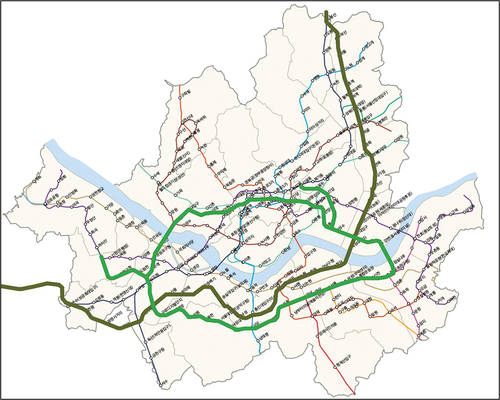

Seoul is a primate city: it concentrates one-fifth of the South Korean population. At nearly 17,000 people/km2 it is a hyperdense city (Kim and Han Citation2012). Its public transport system is extensive, comprising one of the largest metros in the world. It is also heavily used: about three-fourths of Seoul’s residents are public transport users, and of those, about two-thirds ride the metro (Kim et al. Citation2017b).This context differs from other Asian megacities, in which public transit is seen as a low status mode (Ashmore et al. Citation2019). The Seoul metro has 18 lines, 663 stations, over 1000 km of tracks, and is served by a myriad feeder buses (Kim et al. Citation2017a). Lines 1–8 are overseen by Seoul Metro, whereas the others are under the purview of Seoul Metropolitan Rapid Transit (SMRT), Korail (Korea National Railroad), and Metro 9. Overall, 39% of travel in Seoul takes place by metro in 2015 (SMG Citation2019). Rail operations began in 1974, and since then, the metro has undergone continuous improvement and expansion. The scale of the system does not allow for an audit of all 18 lines; therefore, Lines 2 and 7 were selected for field observations. Out of the eight urban lines, these are the most heavily used, carrying 41% of daily subway commuters (). Line 2 operates in a loop and connects 51 stations, whereas Line 7 runs northeast to the southwest, connecting 42 stations (). Trains run from approximately 5.30 am until midnight. Starting in June 2022, the operation hours will be extended to 1 am.

Figure 1. Seoul Metro subway, Lines 2 (light green) and 7 (dark green).

Table 2. Seoul Metro ridership by line.

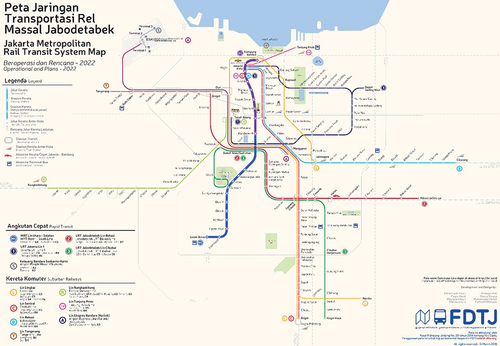

Seoul Metro has been a model for many other subway projects in Asia, including MRT Jakarta. In 2019, MRT Jakarta signed a partnership with Seoul Metro to improve its operations. It is hoped that this technical assistance and knowledge exchange will lead to further congruence between the systems, which in turn might influence the travel behaviour and the design decisions. Unlike Seoul, Jakarta accounts for less than 4% of the Indonesian population. However, the density is nearly as high, at 14,500 people/km2 (Central Bureau of Statistics Citation2021). Jakarta is a motorcycle-oriented city, with public transport accounting for less than 2% of trips (Central Bureau of Statistics Citation2018). But in a populous city, the absolute number of train trips is high at around 1 million per day (Susilo and Joewono Citation2017). Congestion is a major problem (Morris and Hirsch Citation2016). The MRT Jakarta was opened to the public in 2019 after more than 30 years of planning and six years of construction activity. So far, the system has a single, 16 km line that connects 13 stations and serves the central and southern portions of the city (). It carries 73–93,000 commuters daily (). In its second stage, the system will be expanded 8 km northward. MRT Jakarta is the first underground rail system in Indonesia. Trains run between 5 am to about 10 pm.

Figure 2. Jakarta Integrated Rail Transit Map. MRT Jakarta Phase 1 (blue) and Phase 2 (purple).

Table 3. MRT Jakarta ridership.

Epistemological approach

This study assessed the physical performance of the rail transport systems in Seoul and Jakarta from the perspective of women. A gender audit protocol, based on direct observations, was developed and followed in both Seoul and Jakarta.

Why conduct a labour intensive and time-consuming audit when new technologies – ranging from satellite imagery to wearable cameras – are available? However, to assess the characteristics of the built environment, direct observations remain vital in providing fine-grained detail. A long-accepted method in urban design, audits involve more than simply looking at places. Researchers are expected to make a comprehensive and systematic assessment of the specific attributes of a space (Byrne Citation2021).

For example, to evaluate the design quality of an area, audit protocols such as the Urban Design Score Sheet are available (Ewing and Clemente Citation2013) and have been tested in real-world contexts (Hooi and Pojani Citation2020; Leclercq, Pojani, and Van Bueren Citation2020). Other protocols on the attractiveness of walking environments have been compiled and used to evaluate the walkability of streets (Day, Boarnet, and Alfonzo Citation2005; Adkins et al. Citation2012). Protocols also exist to assess the quality of transit-oriented precincts (Jacobson and Forsyth Citation2008; Kong and Pojani Citation2017). However, a protocol on the gendered aspects of transit environments had been missing until now.

Importantly, during audits all researchers conducting fieldwork musts be trained to understand the emic perspectives (native point of view) of local women (Hammersley and Atkinson Citation2007). Ideally, an audit should be completed by more than one researcher per site, and the results compared and moderated. In this case, the audits were conducted by local researchers, originally from the case study cities. The riders’ experience was also evaluated using a participant-observation method. This, as well as the audit protocol, is described below.

Data collection

The protocol developed and followed in this study is presented in . Its elements respond to the barriers affecting women’s travel, as identified in . Three categories of issues are considered (1): safety and security (2), accessibility, and (3) facilities and services. In the literature, these issues emerge as women’s most common concerns when deciding whether to use public transport (Gardner, Cui, and Coiacetto; Chowdhury and Ceder Citation2016).

Table 4. Gender audit protocol.

‘Safety’ refers to accidents (such as slipping on the floor or falling on the tracks), whereas ‘security’ relates to crime, violence, and sexual harassment (Pojani Citation2014). ‘Accessibility’ is a commuter’s ability to easily access and navigate a station (Kaplan et al. Citation2014). ‘Facilities and services’ refer to the information, equipment, and resources available in a subway station area to make subway trips more comfortable and convenient (Olesen and Lassen Citation2012). To develop the individual items within each category, this study was also guided by the Crime Prevention Through Environment Design strategy (CPTED) (Cozens and van der Linde Citation2015).

Once the protocol was fully developed, fieldwork was undertaken in Seoul (December 2018-January 2019) and Jakarta (October-November 2019). In Seoul, 91 stations were assessed across two lines, and in Jakarta, 13 stations were evaluated along the system’s single line. Observations were conducted three times per week on weekdays and once per week on weekends (e.g., Monday, Thursday, Friday, and Sunday), to account for differences in travel patterns, as well as peak and off-peak periods. Three distinct time intervals were observed (1): morning period from between 6:00am and 9:00am (2); midday period from 11:00am to 14:00pm, and (3) evening period from 5:00pm to 8:00pm. A combined total of 168 travel observations were recorded from both subway systems.

The fieldwork was carried out by four researchers, three women and one man. The team was divided into two groups of two persons each. One group, led by a researcher from South Korea, audited the Metro Seoul, and the other group, led by a researcher from Indonesia, conducted the audit of MRT Jakarta. To avoid bias, the researchers shared their observations and collaboratively reflected on the data collection experience.

The geographical scope encompassed the whole station and end-to-end journeys, including the outside area, entrance, concourse, sidewalks, platform, train compartment, and exit. The researchers focused on specifically on how female riders manoeuvred the spaces. The items were rated on a three-point scale (1): poor, insufficient, broken, overwhelming, difficult (2); adequate, sufficient, functional, available; and (3) good, state-of-the-art; above expectations.

While in the field, the researchers took photographs, videos, and written notes. In addition, they rode the subway, circled the stations, and used the facilities within (on-peak and off-peak, during weekends and weekdays) alongside the other riders. The bus stops, crosswalks, and crossing bridges nearest to the stations were also monitored. In Jakarta, one of the researchers took her children and groceries on several trips in order to gain a better understand of the complicated mobility circumstances facing women.

Study limitations

Before proceeding to the findings, a note on methodological limitations. In future gender audits, it would be desirable to complement direct observations with other methods such as surveys or interviews of public transit users (of all genders). These types of qualitative data would help elucidate the range of differences in women’s experiences depending, for example, on trip purpose, age, sexuality, and economic status. Both Seoul and Jakarta are socially conservative places, in which sexual minorities, including transgender and non-binary persons, may find it difficult to express themselves in public space. Therefore, it is impossible to determine the experience of these groups (e.g., regarding toilet use) through observations alone. Future analyses should be guided more explicitly by intersectional theory, to demonstrate how different axes of experience and power cross to shape experience.

Findings

The following discussion is structured according to the three main categories of the audit protocol (1): safety and security (2), accessibility, and (3) facilities and services. A summary of the findings is provided in .

Table 5. Audit results.

Safety and security

CCTV surveillance

In both subway systems, blind spots exist at some stations; these include shadowy areas and corners or walls that perpetrators could use to hide from surveillance cameras or other commuters. Seoul Metro stations have many such spots, especially older, unrenovated ones. Regarding sight obstructions, most stations on the Seoul Metro have circular pillars along the platforms and concourses. While essential structural features, these pillars present a security risk as they are wide enough for a person to hide behind (). The risk is lessened when adequate artificial lighting is provided at the station and pillars are covered in light colour tiles instead of grey-toned ones. In 2015–2016, circular pillars were replaced with square pillars in stations on Line 2 to improve the illumination of the sites and accommodate advertisements on all sides. This intervention has been effective in terms of lighting and visibility. In MRT Jakarta, blind spots are more frequent in stations that are elevated above ground- or street-level (e.g., Lebak Bulus and ASEAN), as these depend on natural lighting during the day. Here, large pillars are installed – some adjacent to glass fences behind which perpetrators could hide. Tall buildings adjacent to stations also cause darkness and block views.

All station entries, concourses, platforms, and train cars are equipped with multiple surveillance cameras (CCTVs) that operate 24/7. In all stations, the position of the customer service and ticketing desks in the centre of the concourse makes it easier for staff to monitor the inflow and outflow of passengers. Seoul Metro has also established intensive surveillance zones at platforms, known as ‘safety zones’ (). These are designated areas with improved lighting, emergency phones, surveillance cameras, and security patrol. Two stations on Line 2 (Sangwangsimni and Jamsillaru) and six on Line 7 (Gongneung, Konkuk University, Banpo, Express Bus Terminal, Daerim, and Cheolsan) have safe zones. However, not all of these are well-marked with signage, making them difficult to locate. MRT Jakarta stations lack ‘safety zones’, but the system provides a special train for women during certain hours.

Security guards

Both Seoul Metro and MRT Jakarta employ security guards (both male and female) to patrol their stations. However, during observations at Seoul Metro, guards were rarely seen (either on foot or at information desks). In contrast, their presence was more visible at MRT Jakarta, particularly near the gates and turnstiles. At the MRT Jakarta entry points, incoming passengers must pass through a security gate, and officers scan each with a metal detector wand (). It is important to note that security for some people can create more hostile environments for others. Observations suggest that some passengers feel uncomfortable with the body scanning. However, the guards tend to be friendly and responsive, and even assist lost passengers by giving directions. On MRT Jakarta platforms, train lines and passenger queues are monitored by at least one security guard; at least two guards are present on each of the 14 trains in daily operation, who also help commuters enter and exit the train cars.

Such high personnel numbers are possible due to relatively low salary levels in Jakarta. In Seoul, where salaries are higher, guards are less numerous. During observations, guards were present in nine stations on Line 2 and five stations on Line 7, with a single person covering the entire station and surrounding areas. Limited information is offered to the public regarding the role of guards at subway stations, and many stations do not have any guards on duty. Station staff, including guards, work in four groups with double shifts, each working 9 hours to cover all subway operations. This means that three persons work each shift who are responsible for: running the station, providing customer service, curbing fare evasion, managing revenue, inspecting and maintaining the station’s facilities, and ensuring the safety of commuters. Given the heavy workload among station staff, one can presume that Seoul Metro relies mainly on CCTV surveillance to ensure passengers’ safety and security.

Emergency services

Both Seoul Metro and MRT Jakarta stations provide emergency facilities and equipment. Features such as emergency buttons, fire hydrants, and fire extinguishers are available on the concourse and platform areas and in all other station zones. Newly designed emergency phones and buttons are provided in the Seoul Metro, particularly in stations on Line 2, with at least three of each located on the platforms. In MRT Jakarta, one emergency stop button is installed on each platform near the office. Emergency exit signs are also highly visible throughout the stations, and fire extinguishers are provided approximately every 10 metres along main walkways. Some power sockets are covered to prevent accidental electric shocks. However, covers are not available in all stations, and some uncovered power sockets are placed in locations that children can reach. Platforms are equipped with sliding doors that prevent passengers from accidentally falling (or being pushed) on the rail tracks while waiting for the train. MRT Jakarta uses two types of sliding doors: 1) full height, which separate the platform and the tracks from floor to ceiling; and 2) platform safety gates, which reach up to an average adult’s chest. The former is generally used at underground stations, whereas the latter is used at elevated stations. In the past, Seoul Metro did not have sliding doors; Line 2 stations have recently been upgraded to instal those. Remodelling and repairs are often spearheaded on Line 2 because this is the most heavily used in the city.

At the time of observations, Line 7 still retained the old emergency system, but upgrades were in progress. All MRT Jakarta stations are equipped with first-aid rooms, but those tend to be hidden away from direct foot traffic and may be difficult to locate in an emergency. MRT Jakarta also provides one ambulance (parked in the Lebak Bulus Depot). Meanwhile, Seoul Metro provides Goodoc (free medical emergency kits and sanitary products) on lines 1 to 8. Passengers can access these through a publicly disclosed password.

Lighting

Lighting in most stations along Seoul Metro and MRT Jakarta is adequate. However, Jakarta’s elevated stations can be dark as they rely on natural lighting during the daytime. On cloudy days and around sunrise and sunset, the platforms can be dim before the artificial lights are manually turned on. The architecture of the elevated stations (13 of those were observed in Seoul and 7 in Jakarta) is such that long shadows are always cast in the station surroundings (). Also, lighting outside stations is poor at night, mainly from streetlights and surrounding retail activities (). Most elevated stations of MRT Jakarta have dark areas, particularly on the platforms, because support pillars stand in the way of artificial lighting. In underground stations, lighting has been designed with pillars and other structures in mind, and the position of lights has been coordinated to minimize shadows and blind spots.

Crowd density

Crowd densities in Seoul Metro and MRT Jakarta depend on each station’s land uses. Stations in zones with active commercial and retail activities have more crowded platforms and concourses, with a continuous inflow of passengers. So do transfer stations or stations located on main streets and avenues. Peak hours (6:50 am to 9:00 am and 5:00 pm to 6:30 pm) are particularly busy – and thus challenging for women. In Jakarta, long queues sometimes form in front of the turnstiles or the sliding doors on the platform – although the overall commuter traffic is not as dense as on the Seoul Metro. In Seoul, Line 2 becomes very crowded during peak hours on weekdays as the stations link major entertainment districts (Yeongdeungpo and Gangnam) and university campuses. Overcrowding in subway cars has been a concern in Seoul as it enables sex offences. During observations, commuters were sometimes seen trying to push through exiting crowds. Directional and information signs were obscured in those cases, preventing people from finding their way out of stations. Generally, the concourse of any station is the most crowded area because this is where passengers can access services such as toilets, lactation rooms, and retail shops. Also, the concourse is used as a passageway linking exits, meeting points, and rest spaces. Stations in residential areas (which are typically smaller) experience thinner crowds and lighter passenger flows.

Accessibility

Entrances and exits

Both Seoul Metro and MRT Jakarta have several entrances and exits at each station, leading passengers to connecting modes. In addition to stairs, most Seoul Metro and all MRT Jakarta stations are equipped with escalators and elevators. In Seoul, elevators are missing at Namguro on Line 7 and Kkachisan on Line 2; at Yongdap and Sinseol-dong on Line 2 and Gwangmyeongsageori on Line 7, elevators only connect to one side of the split platforms. However, Seoul Metro has installed wheelchair lifts attached to stairways as a temporary solution to the broken connectivity at these stations. Using these wheelchair lifts is complicated as the passenger needs to call a station staff member over an intercom to activate the devices. This is a significant hindrance for mobility-impaired commuters as the stations on Line 7 reach three or more levels underground, resulting in steep stairs () and multiple escalators. Rides on wheelchair lifts are slow, inefficient, and tedious. Also, elevators and escalators are not available at all station entry points. This is of particular concern for older adults, pregnant women, and those with impaired mobility, as it increases travel time. In Jakarta, exiting the subway is problematic in some stations, especially for passengers who need to use an elevator. For example, at Setiabudi, there are two exits from the platform: one door leads to the concourse via stairs and escalators, whereas the other exit is only via an elevator, and a fence separates the concourse’s floor. The absence of clear signage on the platform means commuters who take the elevator (e.g., parents with prams) may end up exiting on the wrong end of the station.

Navigation within stations

The issue of navigation is linked to the location of entrances and exits. Using elevators in some Seoul Metro stations requires excessive detouring from the main thoroughfares, resulting in inconvenience for passengers. Over the 91 stations on the Seoul Metro, eight had limited connectivity with significantly time-consuming routes for elevator users. A similar issue was observed in MRT Jakarta, where some stations provided an insufficient number of elevators. For instance, Fatmawati has only one elevator connecting the outside of the station to the concourse. Passengers must approach the station from the correct right side to access the elevator. If approaching from the wrong side, they are forced to walk a long distance to reach the elevator resulting in time lost in transit. However, MRT Jakarta is still ‘under construction’ and more elevators have been planned for existing stations. In 2018, Seoul Metro announced that elevators would be installed at all stations on Lines 1 through 8 by 2022 to achieve the ‘1 station, 1 flow’ objective for passengers with prams and mobility devices. As of 2019, when the fieldwork was conducted, 27 out of 91 stations had yet to be equipped with an elevator. A further 16 stations have been excluded from the project due to structural problems preventing the installation of elevators. MRT Jakarta staff are trained to assist people with disabilities and provide directions. Some stations on Seoul Metro are equipped with video phones to support people with hearing and speech impairments.

Transfers and connectivity

This study distinguishes between transfers between subway lines and other modes of transport. While entering and exiting stations is satisfactory at most stations in Seoul Metro, transferring to adjoining subway lines is not straightforward. Transfers on Line 2 complement most commuters’ flow with shortcuts that directly connect platforms dedicated for transfers without needing to travel up to the station concourse. However, these shortcuts are not accessible to everyone due to limited connectivity for those with prams or mobility aids. For these passengers, transferring between lines means taking a detour from the provided transfer passages, up to the station concourse, and back down to the required platform. At some stations, due to a lack of escalators, these passengers may even need to exit the station, cross a road, and re-enter the station, even though a shortcut transfer passage might be available to others. This is the case for passengers transferring between Lines 4 and 7 at Nowon. MRT Jakarta has only has one bi-directional train line (running between Lebak Bulus and Bundaran HI on a double-track railway, but platform commuters must make their way up to the concourse to get to the opposite platform at elevated stations.

Regarding connectivity to other transport modes, Seoul Metro has bus stops near stations and offers transfer parking (park ‘n’ ride) at 27 stations. On Line 2, four stations provide this. All the park ‘n’ ride lots are near stations (a three-minute walk on average). In Jakarta, only one MRT station (Lebak Bulus) has similar park ‘n’ ride lots, although the plan is to expand those facilities to more stations. Pick-up/drop-off services are unavailable at all MRT Jakarta stations. This increases curb congestion near stations. Commuters who need to reach other stations by car have no choice but to be dropped off outside on the side of the road near the main entrances.

Since the kerbs are often crowded, commuters generally use a motorcycle taxi rather than a vehicle for their trip’s first/last mile portion. Only one MRT Jakarta station features dedicated parking spaces for people with disabilities (). Seoul Metro does not have car parking reserved for disabled people. However, it has upgraded its mobile app ‘Subway Safety Keeper’ to become more disability friendly and provide free wi-fi. The app alerts of train arrivals and leads users to the nearest exit. Subway riders can also report problems such as broken air conditioning and heating systems, as well as emergency situations, including sexual harassment incidents. Subway patrols and police officers can easily pinpoint the location in response to such reports, allowing them to respond quickly.

Figure 9. Parking area for people with disabilities (only available at Lebak Bulus MRT Jakarta station).

Connections to buses are well-structured at every station. Busy and centrally located stations such as Gangnam on Line 2 are linked to up to 115 bus routes servicing all areas of Seoul. In residential areas, stations are mainly serviced with feeder buses which run relatively short distances to connect the backstreets of residential areas to the main roads. In Jakarta, all the MRT stations are next to TransJakarta (Bus Rapid Transit) stops, but the two modes are not physically connected, and in some cases, passengers must climb the stairway of pedestrian bridges that often have steep sloped ramps to transfer between them. Bundaran HI Station is an exception: the TransJakarta stop, and the subway station are next to one another ().

Figure 10. Physical integration between MRT Jakarta and TransJakarta BRT at Bundaran HI. Elevators are available.

Similarly, Blok M benefits from its proximity to the Jakarta bus terminal and multiple TransJakarta stops. Hence, passengers have many choices of destination and transport mode once they exit MRT Jakarta. Another station, Dukuh Atas, is surrounded by other public transport options, including TransJakarta, rail commuter lines, and the airport train, but these are not physically integrated with MRT Jakarta. Transferring passengers must walk a short distance to reach those other modes. Other stations, such as H Nawi, Cipete, and Blok A, are quite close to TransJakarta stops, but access is difficult due to narrow sidewalks and steep pedestrian bridges. At some elevated stations, passengers can access TransJakarta from inside the MRT Jakarta system without crossing any roads or bridges.

Station surroundings

Crosswalks are available outside all stations on Seoul Metro (Lines 2 and 7) and MRT Jakarta. However, convenient connectivity with the surrounding roads is not always guaranteed. For example, on Seoul Metro at Nonhyeon on Line 7, there is a four-way intersection above the station with only two crosswalks running parallel to each other, which results in broken connectivity between the roads (). Similarly, Bongcheon and Guui on Line 2 have crosswalks on their main roads, but these are at least a five-minute walk away from the station exits. Meanwhile, most crosswalks near MRT Jakarta stations consist of a pedestrian bridge built over the street below. Typically, this is designed as a long stretch with steep stairs or steep-sloped ramps, discouraging use. Bundaran HI is the only station with a zebra and pelican crossing (safer and more accessible than pedestrian bridges). All the sidewalks surrounding both subways systems are clean, wide, and equipped with kerb cuts.

Figure 11. Broken or uneven yellow tactiles hamper the mobility of people with disability at Seoul Metro.

Indonesians are notoriously averse to walking due to the hot climate and an unsupportive road infrastructure. However, MRT Jakarta has encouraged some walking (i.e., to reach the stations). Unfortunately, kerbs outside MRT Jakarta are high and can be hard to climb for some pedestrians. At some older Seoul Metro stations, sidewalk quality is uneven. Also, earlier standards permitted narrower sidewalks, which are inadequate for current passenger flows. In Jakarta, some sidewalks and pedestrian bridges surrounding MRT stations are not safe or convenient to use. Coordination is required to address these issues as the transport infrastructure outside MRT Jakarta is controlled by a variety of agencies.

Facilities and services

Public toilets

Public toilets are available at all stations on Seoul Metro and MRT Jakarta. MRT Jakarta’s toilets are pram-friendly and cater to the needs of people of different genders, older adults, parents with children, and people with disabilities. However, this is not the case on Seoul Metro: on Line 2, a passenger with a baby on a pram must detour to the adjoining concourse of Line 5 to access a toilet equipped with baby change facilities. The provision of baby changing facilities is adequate across all Seoul Metro stations, but access is often restricted. For example, the public toilets at Yeongdeungpo-gu Office Station on Line 2 are only accessible by stairs.

Moreover, most multipurpose restrooms on Line 7 are situated within regular toilets, some of which have entrances that are too narrow for prams or wheelchairs. Toilets on MRT Jakarta have wider doorways accessible to people with mobility aids or prams. Accessible toilets feature emergency alarm buttons to ensure the safety of users (). Some stations, such as Bundaran HI, provide ample accessible toilets with stalls and urinals. Other stations, such as Setiabudi, only provide stalls and their toilets are too small to manoeuvre wheelchairs or prams. The accessible toilets are unisex and therefore could be used by transgender or non-binary persons. No stations have small toilets for children, and baby changing facilities are usually placed inside lactation rooms (rather than inside toilets as in Seoul).

Long queues for public toilets, especially for women and during rush hours, were observed both in Seoul Metro and MRT Jakarta. This depends on the number of available stalls. The lighting of the entrances and the insides of toilets is adequate in all stations on both the Seoul Metro and MRT Jakarta. Toilets at most stations have automatic lights which go on when the room’s door is opened and remain lit while the space is occupied. CCTV surveillance devices and security guards were observed near toilet entrances. In Seoul Metro stations on Line 2, toilets have clear, visible entries that can be seen from the centre of the concourse (). The toilets on Line 7 are less well designed. Because Line 7 stations are multi-storeyed, toilets are often located in corners far away from the primary foot traffic, which undermines safety and convenience. Lighting tends to be inadequate outside toilets even though the insides are well-lit. Toilets with entrances covered by objects such as escalators or circular pillars appear dimmed. All restrooms at stations on Line 7 share entrances, meaning that men and women enter toilet areas together before branching off to female or male sides within a corridor. Gender-neutral toilets are not provided in either system.

Lactation/nursing rooms

All MRT Jakarta stations have lactation rooms that are adequately furnished with breastfeeding and nursing facilities (). Seoul Metro provides 101 nursing rooms over Lines 1 to 8, with 34 nursing rooms available across stations on Lines 2 and 7 (). Most of these rooms are near station offices, customer service centres, or nearby offices, allowing parents to find them quickly and easily. However, some nursing rooms in Seoul Metro stations are difficult to access. For example, at Express Bus Terminal on Line 7, the room cannot fit prams or mobility aids. At Gasan Digital Complex Station on Line 7, the nursing rooms are in areas far away from the main foot traffic flow. Both mothers and fathers can access all nursing rooms operated by Seoul Metro. Parents must talk to a station staff member over an intercom to unlock the door. This way, station staff can keep track of the usage of these facilities and ensure the safety of the users within. In MRT Jakarta stations, nursing rooms can be entered without asking station staff to open the door, and several persons can share the room at once. This makes the rooms more accessible, but it also makes it difficult to keep away intruders unless users lock the door from the inside.

Information and wayfinding

Both Seoul Metro and MRT Jakarta stations provide directional signs attached to walls, ceilings, pillars, and the ground to direct commuters towards platforms/exits/facilities. But in Seoul Metro stations at peak hours, this information becomes difficult to find when signs are covered or hidden behind crowds. At Gangnam Station on Line 2, the size and number of access points (and related signage) can be overwhelming. In most MRT Jakarta underground stations, direction signs from the platform to toilets, lactation rooms, and prayer rooms are not provided. Commuters who choose the wrong route to the concourse area must go back down to the platform level and take the correct way to reach those services. In addition, stations lack a map with information about the surrounding areas, which accurately portrays travellers’ position relative to exits. This would help passengers to access nearby facilities easily or transfer to other transport modes. Many displays are found across Seoul Metro and MRT Jakarta stations, as well as inside train cars. Public service announcements and commercial advertisements in the form of digital media, posters, stickers, prints on screen doors, and large-sized boards are displayed for commuters to see during their journeys. Overuse of commercial advertisements is evident on Lines 2, and 7 of Seoul Metro, which obscure or detract attention from important signage. At the Social Problem-Solving Design International Forum held in Seoul in 2018, it was proposed that some commercial advertisements be removed from subway stations. Still, this proposal has been controversial as it would reduce station revenue.

Shopping outlets

Both systems include some retail outlets, albeit not at every station. These are usually convenience stores, cafés, food stalls, cosmetics shops, and clothing stores. Where available, retail helps female commuters complete shopping tasks more conveniently and creates a vibrant and dynamic atmosphere in stations. In MRT Jakarta stations, retail shops are generally located on the concourse (before ticket scanning) so that non-passengers can access them too. In contrast, the size and shape of Seoul Metro stations (especially on Line 7) are such that some stores are tucked away from the centre of the concourse, making them less convenient to reach.

Other items

Since the fieldwork for this study was completed, the two systems have launched a few other women-friendly initiatives. In Seoul Metro, pink seats have been installed which prioritize pregnant women. MRT Jakarta now provides special, women-only train cars during peak hours (7:00 a.m. to 9:00a.m. and 5:00 p.m. to 7:00 p.m.) on weekdays. Those cars are placed next to the locomotive. Signage is visible on the platform floor to direct female passengers (). All stations on MRT Jakarta are equipped with first-aid rooms and prayer rooms separating men and women; the latter meet the needs of Muslim travellers.

Conclusion

Both Seoul Metro and MRT Jakarta have made significant efforts to accommodate all passengers, including women. As a new generation metro, MRT Jakarta has been more responsive to women’s travel needs by incorporating female-friendly features in its physical design from the outset. A lag in adopting rail transport technology may have provided an opportunity for Indonesian planners to learn from the mistakes of others (Pojani Citation2020). However, Seoul Metro also responds to calls for gender mainstreaming during the periodic upgrades to its facilities and rolling stock. This is commendable because a public transit system that works well for women works better for everyone. With some improvements, both subways could achieve universal design standards.

Both bottom-up and top-down pressures have forced Seoul and Jakarta to better accommodate gender needs in their transit systems. At the grassroots level, expanding opportunities for women in school and the workforce have contributed to a growing awareness of the importance of gender equality in all aspects of life (including transport and public space). At the national level, Indonesia has issued a Presidential Instruction about gender mainstreaming in national development. In a similar vein, South Korea has passed a Framework Act on Gender Equality. And, both countries have ratified the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), which requires that female perspectives be considered in local policymaking and development processes.

Beyond physical design improvements, raising public awareness of gender issues in transport planning is essential as well. Gender should be systematically addressed in all stages of the process, including implementation and monitoring. Horizontal and vertical coordination between agencies is crucial. Planners at all levels should look at the bigger picture and attain common goals. Collaborative approaches have the potential to reduce power imbalances among institutions, as this is a known challenge to consistent gender mainstreaming. Importantly, provisions for women cannot be an afterthought or a ‘retrofit’ item. They need to be placed at the centre of transport and, more broadly, city making. To achieve this, political vision and leadership – pro-women and by women – is paramount.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adkins, A., J. Dill, G. Luhr, and M. Neal. 2012. “Unpacking Walkability: Testing the Influence of Urban Design Features on Perceptions of Walking Environment Attractiveness.” Journal of Urban Design 17 (4): 499–510. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2012.706365.

- Allen, H. 2018. Approaches for Gender Responsive Urban Mobility: A Sustainable Transport: A Sourcebook for Policy-Makers in Developing Cities Module 7a. 2nd ed. Bonn, Germany: GIZ-SUTP. https://womenmobilize.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/A_Sourcebook_Social-Issues-in-TransportGIZ_SUTP_SB7a_Gender_Responsive_Urban_Mobility_Nov18-min.pdf.

- Ashmore, D. P., D. Pojani, R. Thoreau, N. Christie, and N. A. Tyler. 2019. “Gauging Differences in Public Transport Symbolism across National Cultures: Implications for Policy Development and Transfer.” Journal of Transport Geography 77:26–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2019.04.008.

- Asian Development Bank. 2013. Gender Toolkit: Transport - Maximizing the Benefits of Improved Mobility for All. Mandaluyong City: Asian Development Bank. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/institutional-document/33901/files/gender-tool-kit-transport.pdf.

- Byrne, J. A. 2021. “Observation for Data Collection in Urban Studies and Urban Analysis.” In Methods in Urban Analysis. Cities Research Series, edited by S. Baum, 127–149. Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-1677-8_8.

- Central Bureau of Statistics. 2018. Transportation Statistics DKI Jakarta 2018. Jakarta: Badan Pusat Statistik Provinsi DKI Jakarta. https://jakarta.bps.go.id/publication/2018/10/03/cb1285d8dbe8be8754a5830d/statistik-transportasi-dki-jakarta-2018.html.

- Central Bureau of Statistics. 2021. DKI Jakarta Province in Figures 2021. Jakarta: Badan Pusat Statistik Provinsi DKI Jakarta. https://jakarta.bps.go.id/publication/2021/02/26/bb7fa6dd5e90b534e3fa6984/provinsi-dki-jakarta-dalam-angka-2021.html.

- Chowdhury, S., and A. Ceder. 2016. “Users’ Willingness to Ride an Integrated Public-Transport Service: A Literature Review.” Transport Policy 48:183–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2016.03.007.

- Conteh, J. A. 2016. “Gender Audit.” In The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Gender and Sexuality Studies, edited by N. A. Naples, 1–3. Singapore: John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118663219.wbegss547.

- Cozens, P., and T. van der Linde. 2015. “Perceptions of Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (CPTED) at Australian Railway Stations.” Journal of Public Transportation 18 (4): 73–92. https://doi.org/10.5038/2375-0901.18.4.5.

- Dahlan, A. F., and A. Fraszczyk. 2019. “Public Perceptions of A New MRT Service: A Pre-Launch Study in Jakarta.” Urban Rail Transit 5 (4): 278–288. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40864-019-00116-0.

- Day, K., M. Boarnet, and M. Alfonzo. 2005. “Irvine Minnesota Inventory for Observation of Physical Environment Features Linked to Physical Activity”. https://webfiles.uci.edu/kday/public/index.html.

- Delbosc, A. 2012. “The Role of Well-Being in Transport Policy.” Transport Policy 23:25–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2012.06.005.

- Ewing, R., and O. Clemente. 2013. Measuring Urban Design: Metrics for Livable Places. Washington, DC: Island Press. https://doi.org/10.5822/978-1-61091-209-9.

- Gardner, N., J. Cui, and E. Coiacetto. 2017. “Harassment on Public Transport and Its Impacts on Women’s Travel Behaviour.” Australian Planner 54 (1): 8–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/07293682.2017.1299189.

- Gil Solá, A., and B. Vilhelmson. 2022. “To Choose, or Not to Choose, a Nearby Activity Option: Understanding the Gendered Role of Proximity in Urban Settings.” Journal of Transport Geography 99:103301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2022.103301.

- Greed, C. 2019. “Join the Queue: Including Women’s Toilet Needs in Public Space.” The Sociological Review 67 (4): 908–926. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026119854274.

- Hamilton, K., and L. Jenkins. 2000. “A Gender Audit for Public Transport: A New Policy Tool in the Tackling of Social Exclusion.” Urban Studies 37 (10): 1793–1800. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980020080411.

- Hammersley, M., and P. Atkinson. 2007. Ethnography: Principles in Practice. 3rd ed. London and New York: Routledge.

- Hanson, S. 2010. “Gender and Mobility: New Approaches for Informing Sustainability.” Gender, Place and Culture 17 (1): 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09663690903498225.

- Hooi, E., and D. Pojani. 2020. “Urban Design Quality and Walkability: An Audit of Suburban High Streets in an Australian City.” Journal of Urban Design 25 (1): 155–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2018.1554996.

- Jacobson, J., and A. Forsyth. 2008. “Seven American TODs: Good Practices for Urban Design in Transit-Oriented Development Projects.” Journal of Transport and Land Use 1 (2): 51–88. https://doi.org/10.5198/jtlu.v1i2.67.

- Kaplan, S., D. Popoks, C. Giacomo Prato, and A. Ceder. 2014. “Using Connectivity for Measuring Equity in Transit Provision.” Journal of Transport Geography 37:82–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2014.04.016.

- Kim, H. M., and S. S. Han. 2012. “Seoul.” Cities 29 (2): 142–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2011.02.003.

- Kim, M.-K., S.-P. Kim, J. Heo, and H.-G. Sohn. 2017b. “Ridership Patterns at Subway Stations of Seoul Capital Area and Characteristics of Station Influence Area.” KSCE Journal of Civil Engineering 21 (3): 964–975. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12205-016-1099-8.

- Kim, H., S. Kwon, S. K. Wu, and K. Sohn. 2014. “Why Do Passengers Choose a Specific Car of a Metro Train during the Morning Peak Hours?” Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 61:249–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2014.02.015.

- Kim, C., S. Wook Kim, H. Jay Kang, and S.-M. Song. 2017a. “What Makes Urban Transportation Efficient? Evidence from Subway Transfer Stations in Korea.” Sustainability 9 (11): 2054. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9112054.

- Kong, W., and D. Pojani. 2017. “Transit-Oriented Street Design in Beijing.” Journal of Urban Design 22 (3): 388–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2016.1271700.

- Lawton, C. A., and J. Kallai. 2002. “Gender Differences in Wayfinding Strategies and Anxiety about Wayfinding: A Cross-Cultural Comparison.” Sex Roles 47 (9/10): 389–401. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021668724970.

- Leclercq, E., D. Pojani, and E. Van Bueren. 2020. “Is Public Space Privatization Always Bad for the Public? Mixed Evidence from the United Kingdom.” Cities 100:102649. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102649.

- Loukaitou-Sideris, A. 2014. “Fear and Safety in Transit Environments from the Women’s Perspective.” Security Journal 27 (2): 242–256. https://doi.org/10.1057/sj.2014.9.

- Loukaitou-Sideris, A. 2020. “A Gendered View of Mobility and Transport: Next Steps and Future Directions.” In Engendering Cities: Designing Sustainable Urban Spaces for All, edited by I. S. de Madariaga and M. Neuman, 1st ed, 19–37. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351200912.

- Morris, E. A., and J. A. Hirsch. 2016. “Does Rush Hour See a Rush of Emotions? Driver Mood in Conditions Likely to Exhibit Congestion.” Travel Behaviour and Society 5:5–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2015.07.002.

- Moser, C. 2005. “Has Gender Mainstreaming Failed?” International Feminist Journal of Politics 7 (4): 576–590. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616740500284573.

- Olesen, M., and C. Lassen. 2012. “Restricted Mobilities: Access To, and Activities In, Public and Private Spaces.” International Planning Studies 17 (3): 215–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563475.2012.704755.

- Pojani, D. 2014. “Women’s Issues/Gender Issues.” In Encyclopedia of Transportation: Social Science and Policy, edited by M. Garrett, 1st ed.,1731–1733. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483346526.n605.

- Pojani, D. 2020. The Urban Book Series: Planning for Sustainable Urban Transport in Southeast Asia Transfer, Diffusion, and Mobility. 1st ed., 1 vol. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-41975-2.

- Pojani, D., L. Sagaris, and E. Papa. 2021. “Editorial of Special Issue on ‘Transport, Gender, Culture’.” Transportation Research Part A Policy and Practice 144 (February): 34–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2020.12.002.

- Putranto, L. S., and A. N. Tajudin. 2020. “The Effectiveness of Special Carriages for Female in Protecting Female Train Passengers”. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. Vol. 1007. Jakarta: IOP Publishing . https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/1007/1/012020.

- Shin, H., D. Kyu Kim, S. Young Kho, and S. Hyung Cho. 2021. “Valuation of Metro Crowding considering Heterogeneity of Route Choice Behaviors.” Transportation Research Record 2675 (2): 162–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361198120948862.

- Sida. 2017. Handbook for Mainstreaming: A Gender Perspective in the Rural Transportation Sector. 1st ed. Stockholm: Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency. https://cdn.sida.se/publications/files/sida2206en-handbook-for-mainstreaming—a-gender-perspective-in-the-rural-transportation-sector.pdf.

- SMG. 2019. “Safe, Convenient, People-Centered Transportation in Seoul”. Seoul. www.seoul.go.kr.

- Susilo, Y. O., and T. B. Joewono. 2017. “Indonesia.” In The Urban Book Series: The Urban Transport Crisis in Emerging Economies, edited by D. Pojani and D. Stead, 1st ed., Vol. 1, 107–126. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-43851-1.

- TRANSGEN. 2007. Gender Mainstreaming European Transport Research and Policies: Building the Knowledge Base and Mapping Good Practices. Copenhagen: Co-ordination for Gender Studies, University of Copenhagen. https://cordis.europa.eu/docs/results/36/36774/123865391-6_en.pdf.

- World Bank. 2010. A Review of World Bank Infrastructure Projects (1995-2009): Making Infrastructure Work for Women and Men. Washington DC: World Bank. http://go.worldbank.org/UW1GDCX260.

- Yantzi, N. M., M. W. Rosenberg, and P. McKeever. 2007. “Getting Out of the House: The Challenges Mothers Face When Their Children Have Long-Term Care Needs.” Health and Social Care in the Community 15 (1): 45–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2006.00663.x.

- Zhou, Y., X. Cheng, L. Zhu, T. Qin, W. Dong, and J. Liu. 2020. “How Does Gender Affect Indoor Wayfinding under Time Pressure?”. Cartography and Geographic Information Science 47 (4): 367–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/15230406.2020.1760940.