ABSTRACT

The implementation of city lockdowns in response to the COVID-19 pandemic exposed some social inequalities in Mexico. The paper evaluates the effects of the closure of the Alameda Central, a public park in the Historic Centre of Mexico City. It examines how its closure affected some vulnerable populations, including homeless people, beggars, street vendors, buskers, and male sex workers, to the extent that they resisted leaving or found ways to return to public space. The research shows how Mexican COVID-19 policies tended to overlook the diversity of populations making use of public space, and their various necessities.

Introduction

I will stay here [in the Alameda], let’s see if I get some [Mexican] pesos.Footnote1

Finally, they [city authorities] have taken it [the Alameda Central] from us [rough sleepers in the park].Footnote2

[The Alameda] is one of the only places where I don’t feel excluded or disturbed from meeting other people like me.Footnote3

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, on 6 April 2020, Mexico City’s authorities closed the Alameda Central.Footnote4 Many visitors resisted complying with the official advice despite the presence of police officers, who usually patrol the Alameda and other public spaces in the Centro Histórico [‘Historic Centre’]. The city authorities had implemented partial physical restrictions in the Alameda and other public spaces since mid-March 2020, intending to reduce gatherings. Those people refusing to leave the Alameda seemed to have stronger motivations to stay in the park than following official advice. Closing historic public spaces in Mexico City was aligned with the social distancing and lockdown policies worldwide.Footnote5

The pandemic seemed to change how people used to live in cities and interact with others. Some official advice included various hygienic measures, social distancing, restrictions of movement and city lockdowns (World Health Organization Citation2020). Lockdowns and social distancing in public spaces, in some cases, included their total or partial closure. In response to lockdowns worldwide, urbanists immediately reacted to the impact of COVID-19 on cities (Du, King, and Chanchani Citation2020; Florida Citation2020; Melis et al. Citation2020). Some scholars claimed that the COVID-19 pandemic was also an opportunity to rethink urban design practices and policies, promoting ‘global health’ in cities (Honey-Rosés et al. Citation2020, 3, 12). Others even referred to the pandemic as a way to ‘create opportunities to reshape cities in more equitable ways’ (Florida Citation2020). A large body of urban literature has more recently examined the medium- and long-term lessons from the pandemic and the ‘post-COVID city’ (Batty et al. Citation2022; Florida, Rodríguez-Pose, and Storper Citation2021).

COVID-19 exposed deeply rooted inequalities in some cities. The pandemic severely affected some poorer populations, who often have less access to health care and faced greater difficulties in safe self-confinement (Du, King, and Chanchani Citation2020). For some disadvantaged populations, in Latin America and the global South, public spaces are often ‘the only recreational outdoor spaces […] and can provide relief from cramped living conditions’ (Honey-Rosés et al. Citation2020, 10). The effects of the pandemic thus differentiated those who could ‘stay at home’, and those for whom staying in public space was indispensable, revealing some of the systemic inequalities. Some disadvantaged groups tend to make use of public space to cover indispensable necessities, such as shelter, livelihood, or essential companionship, as this paper examines.

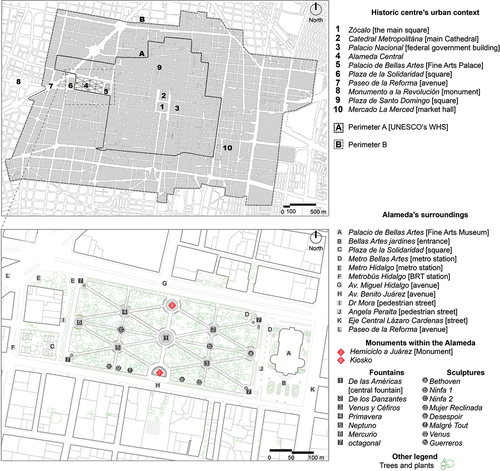

The article portrays the case of the lockdown of the Alameda Central (). It seeks to [1] identify the urban policies and spatial restrictions implemented during the pandemic, [2] analyse the social and physical effects of COVID-19 policies in historic public spaces, [3] examine how such restrictions affected directly vulnerable populations, and [4] evaluate how these populations responded to the effects of policies. The article demonstrates that the Alameda helps to support some essential needs of vulnerable populations. Its closure was challenged by those groups who benefit directly or indirectly from the park. The paper is not intended to provide urban policy or urban design recommendations during or after the pandemic. It is neither intended to suggest that disadvantaged populations were the sole group affected during the COVID-19 crisis in Mexico City nor to argue that they were the unique populations making use of the Alameda at the time of its closure. By portraying Alameda’s lockdown, this article seeks to examine the relationship between public space and the essential needs of some disadvantaged populations, to understand how such relationships exposed some inequalities and to analyse how Mexican COVID-19 policies overlooked such differences in public spaces.

Public space during the COVID-19 pandemic and social inequalities

Lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic reminded us that public spaces are essential for cities and societies. Within the urban literature, a range of attributes characterizes public spaces (see, for example, Carmona Citation2010; Gehl Citation2001; Low Citation2000; Madanipour Citation2019; Whyte Citation1980). The idea that public space is crucial for urban culture, conviviality and social life has become almost common sense, almost banal. The pandemic also reminded us of the importance of discussing public spaces beyond the dominant Western conception, looking at class, race and gender differences, and exploring reconfigurations of the public sphere and the importance of physical space.

Public spaces in Mexico City, particularly in the historic centre, have long helped to support daily necessities, such as livelihood or shelter, becoming indispensable for the urban poor and their practices (Becker and Müller Citation2013; Crossa Citation2016; Giglia Citation2013; Jaramillo Puebla Citation2007; Ward Citation1990). These practices include street vending, begging, homelessness and prostitution, among others. The robust life of Mexican public spaces also includes practices considered ‘undesirable’, ‘informal’ or even ‘illegal’ by the existing status quo.

Studies of social inequalities in cities have long focused on different forms of socio-spatial segregation (e.g., gated communities, ghettoes, housing estates, and so forth), on the inequalities faced by particular social groups in specific places of the city, and/or socioeconomic dynamics on neighbourhoods and public spaces (Amin Citation2007). Urban policies have long perpetuated inequalities. Although urban policies could have ‘good intentions’ for social inclusion and equity, many policy schemes have merely reproduced structural class, gender or ethnic inequalities (Hall Citation1982). In some regions of the global South, the urban poor have, however, claimed and appropriated urban space, challenging the unequal terms of citizenship and livelihood that have been laid down in urban areas (Roy Citation2009). Social practices of disadvantaged populations have confronted the unequal dynamics of local labour, housing markets or local systems of provision, often revealing some forms of unequal economic distribution. Some of these practices have long occurred in public spaces, and city lockdowns during the pandemic made more visible some of these differences, as this article discusses.

City lockdowns exemplified radical strategies during the COVID-19 crisis. Social and urban policies in public spaces were crucial to reducing gatherings and crowds. The closure of public spaces portrayed how uses and social practices changed, how adaptations in urban policies and spatial restrictions were required, and how different populations were affected in various ways. The COVID-19 pandemic and city lockdowns gave rise to questions on the relationship between public space and social inequality. How did public spaces adapt during the pandemic? Which physical restrictions were implemented? What populations did react to the closure of public spaces? And how? How did restrictions in public spaces unfold when they met social inequalities? How did the physical qualities of space support some practices of certain disadvantaged populations?

Methods of research

The article presents evidence from the Alameda Central and the Historic Centre of Mexico City. The research opted for a single case study, which engages in-depth with multi-dimensional methods to understand different issues in the examined area. A mixed-methods approach was chosen for data collection and data analysis with an emphasis on qualitative methods (Yin Citation2014). Empirical data from the Alameda Central and the historic centre was compiled and analysed during long-term observations since 2013, and more systematically during extensive periods of fieldwork from 2018 to 2023, in three main stages.

The first stage sought to examine recent urban regeneration policies, particularly the 2011 Comprehensive Management Plan of the Historic Centre of Mexico City, updated in 2017, and the 2013 Management Plan and Conservation of the Alameda Central (Gobierno de la Ciudad de México Citation2011, Citation2013, Citation2017). This stage included the analysis of 35 semi-structured interviews with local authorities and visitors of the Alameda Central, conducted from November 2019 to February 2020.Footnote6 The interviews were transcribed verbatim and coded using the qualitative software NVivo 12. The codes and themes were established following the initial analysis of urban policies and revision of the literature. Some regular visitors of the Alameda were identified based on ethnography and long-term participant observation. Their practices and location within the park were recorded systematically on printed maps and research diaries (for systematic observation of public space, see Gutiérrez and Törmä Citation2017, Citation2020; Low Citation2000; Törmä and Gutiérrez Citation2021; Whyte Citation1980). Over 325 photographs and 35 short videos were recorded and triangulated with the analysis of interviews. The fieldwork also included ethnographic research, which was carried out with various groups in the park, such as a community of elderly gay men, male sex workers, homeless people, street vendors, street performers and artists, among other frequent visitors. This approach was crucial to understand experiences, practices and necessities of these groups.

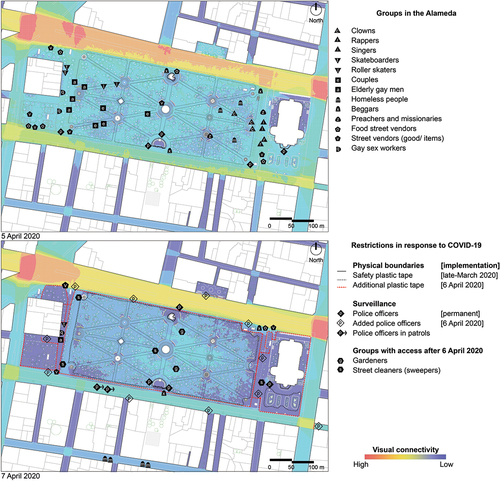

The second stage sought to examine the effects of COVID-19 urban policies and the closure of the Alameda. It analysed the 2020 General Guideline for the Mitigation and Prevention of COVID-19 in Open Public Spaces (Gobierno de México Citation2020b). This stage incorporated complementary site observation and 25 interviews with regular users of the Alameda, carried out from 1 to 10 April 2020, when the park was officially closed. The interviews were analysed following the same principles as in the first stage. During fieldwork, it was analysed how some identified groups in the former stage resisted Alameda’s lockdown (Gutiérrez Citation2021). This stage also involved additional observations of historic public spaces from online streaming closed-circuit television cameras (CCTV).Footnote7 Some observations were redrawn using computer-aided design (CAD) software. To analyse occupational patterns before and after the lockdown, the mapped observations were examined using a visibility graph analysis (VGA) in depthmapX software. This analysis belongs to a computational tool developed within space syntax theory, which combines a set of analytical, quantitative and descriptive tools for analysing the urban form (Hillier and Hanson Citation1984). VGA included the attributes of ‘visual connectivity’, which refers to a field of possible viewsheds determined by opaque boundaries like buildings, trees, statues or other visual obstacles. The settings of the area of analysis were established to cover parts of the immediately adjacent streets. In this case, the visual connectivity before and after the closure of the Alameda were compared. The latter included the boundaries and temporary physical restrictions erected during the lockdown. This quantitative analysis was intended to understand the recorded systematic observations together with Alameda’s morphology, identifying how and why some areas within the park are more suitable for practices of vulnerable populations and how they changed during COVID-19.

The last stage involved additional fieldwork in the Alameda from December 2022 to February 2023, when the COVID-19 restrictions were completely lifted. Complementary field observation and 25 interviews with users from the identified groups were conducted. This stage was intended to analyse any medium- or long-term change after the lockdown. The final combination of methods of research and stages was effective while triangulating findings and results as part of strengthening the overall research design.

The Alameda Central and the Historic Centre of Mexico City

The Alameda is located on the western edge of the historic centre (). It is one of the oldest parks in the continental Americas, planned at the edge of the Spanish colonial layout in 1592. It has been portrayed in different moments in Mexican history and remained a meaningful heritage public space, being acknowledged as one of the most emblematic parks in Mexico, and arguably in the Americas (Agostoni Citation2003). UNESCO designated the ‘Perimeter A’ or inner area of the historic centre, including the Alameda Central, as World Heritage Site in 1987 (see ). Since then, the historic centre has been subject to various regeneration and heritage conservation policies.

Figure 2. Mexico City’s historic centre (top) and the Alameda Central (bottom).

Different groups make use of the Alameda currently. For example, the Hemiciclo [hemicycle monument] to President Benito Juárez often gives place to different social protests, including recent feminist demonstrations. Some regular groups in the Alameda include commuters, families with kids, groups of elderly people, joggers, skateboarders, roller skaters, homeless people, beggars, street vendors, street performers (i.e., singers, musicians, clowns and dancers), Christian missionaries, elderly gay men and male sex workers, police officers, gardeners and street cleaners, among others (Gutiérrez Citation2017). Some of these groups live in or make their livelihoods in the park (Giglia Citation2013; Jaramillo Puebla Citation2007). Some have often been directly or indirectly excluded from regeneration policies or heritage conservation programmes, which have been accused of favouring private capital investment, displacement of low-income residents and demographic change (Crossa Citation2016; Delgadillo Citation2016; Hernández Cordero Citation2013). The struggle for the use of the Alameda and other historic public spaces in Mexico City became more evident during city lockdowns in response to COVID-19.

Urban policies responding to COVID-19 in Mexico

In March 2020, the Mexican national authorities advised the population to stay at home and avoid public gatherings. On 7 April 2020, the national government and the Secretary of Health enacted the General Guideline for the Mitigation and Prevention of COVID-19 in Open Public Spaces (Gobierno de México Citation2020b). The policy included regulations for parks, squares, open auditoriums, stadiums and beaches, among other open-air spaces and large-scale buildings. It advised that public gatherings must be suspended, but if not, people should keep a minimum social distance of 1.5 metres, places that allow visitors should be cleaned using water, soap and other chemicals one to three times a day or more; above all, people should stay at home and only go out when essential. The national authorities also launched the policy Quédate en casa [‘Stay at home’] and a special campaign named Su-Sana Distancia [‘Its Healthy Distance’], a Mexican cartoon of a female superhero that promoted social distance (Gobierno de México Citation2020a).

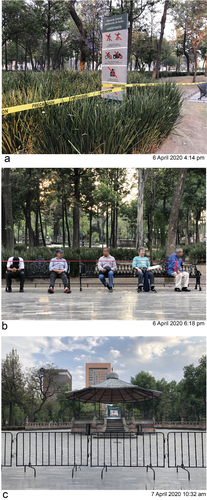

During lockdowns, restrictions were reinforced in public spaces located in Mexico City’s historic centre, which often receive thousands of visitors per day. Additional strategies to dissuade visitors from accessing such places were required. Special operativos [police force actions] were implemented. Police patrols circulated streets and historic public spaces, playing audio recordings that reminded visitors to avoid staying outdoors and return to their homes. Some public spaces, however, needed additional physical restrictions, such as plastic caution tape, temporary metal fencing, wood structures and metal hoardings at their perimeter during city lockdowns, as shown in .

The lockdown of the Alameda Central

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, in late March 2020, the city authorities closed Alameda’s kiosko [bandstand], which usually attracts many visitors (Gutiérrez Citation2021). On 3 April 2020, employees from the Department of Public Works and Services increased a cleaning strategy in the Alameda and other public spaces using water, soap and other chemicals (Gobierno de la Ciudad de México Citation2020). Street sweepers and gardeners usually clean and maintain the Alameda daily. They often meet at the Hemiciclo before dispersing around the park to start their cleaning duties, driving a water truck along the alleys, and washing benches and pavements. The COVID-19 emergency did not reduce the number of gardeners and street cleaners, their presence indeed increased. They used face masks and gloves to continue with their cleaning activities; as a street sweeper mentioned in an interview:

People have been very foolish, and they don’t stay at home. We [street cleaners, sweepers and gardeners] will continue working. We have to clean the park; many leaves fall from the trees, and we have to clean everything that people left dirty.Footnote8

On 6 April 2020 at about 1:30pm, the Alameda Central was officially closed. Around fifty people were sitting in the park at the time when twenty police officers asked them to leave. Police officers strung up a red or yellow safety plastic tape, with the warning Precaución [‘Caution’] between trees, benches and statues. Later, police officers stayed in the Hemiciclo a Juárez, as usual. Other officers stayed in fifteen different spots around the park. They patrolled the Alameda in three shifts during the day, seeking to dissuade visitors from using the park, including homeless people, beggars and street vendors. From 6 to 8pm, passers-by and visitors were surprised to find the Alameda enclosed by plastic tape. They asked police officers how long the park would be closed. Officers replied that in the first instance, as far as they had been told, it would be for two weeks although it could be as much as six or eight weeks. Nobody knew …

Later, around sixty people were resting on benches on each of the pedestrian streets alongside the park. Some visitors made use of the benches that were still available, on the western and eastern edges, and around the fountains in the corners. Others decided to duck under the safety tape to sit on the benches, just a few feet away. On 7 April 2020, the Alameda woke up to further physical restrictions. A movable metal fencing was erected about a metre in front of the safety plastic tape. The metal fencing also closed off Plaza de la Solidaridad, next to the Alameda, leaving a narrow corridor leading to the Hidalgo metro station and the entrance of the Palacio de Bellas Artes (see ). Being essential for some populations, they reacted immediately during and after the closure of the Alameda Central.

The Alameda as a shelter

Despite the presence of police officers, CCTV cameras and various strategies established after different urban regeneration policies, homeless people have used the Alameda as an open shelter. At times, police officers have displaced homeless populations from the park (Giglia Citation2013; Leal Martínez Citation2016; Makowski Citation2004). However, homeless people have continuously found ways to return.

On Sunday morning, 5 April 2020, only a few visitors were walking in the Alameda. Around ten homeless people got up at about 8am. They slept on stone benches or inside the gardens on the central and western edges. Some of them washed their face in the fountains after picking up their temporary shelters made of blankets and cardboard. Gerardo, a homeless person, said that they had lived in the park for the last seven months since they had not been able to find a place in any nearby shelter.Footnote9 Gerardo mentioned that homeless people have a respectful relationship with other groups in the park, including police officers, gardeners, and street cleaners.Footnote10 Homeless people have created a degree of community in the Alameda, sharing food and helping each other. This sense of community is difficult to achieve in a shelter, as Gerardo also mentioned.

The city authorities have recognized homelessness in the historic centre as an important social issue in Mexico City. The Authority of the Historic Centre in collaboration with the alcaldía [borough] Cuauhtémoc established specific policies for the social integration of rough sleepers in the historic centre, such as the Inter-institutional Protocol for Comprehensive Care of Street Populations, included in the 2017 Management Plan (Gobierno de la Ciudad de México Citation2017, 98–99). But the city authorities still consider homelessness a ‘threat’ in the Alameda, as a senior-level authority mentioned in an interview:

There are still places where homeless people sleep [in the Alameda]. There have been a couple of incidents when rough sleepers have assaulted passers-by, even causing severe injuries; for example, there was one person [passer-by] stabbed recently…Footnote11

During the COVID-19 lockdown, homeless people moved to nearby sidewalks in the historic centre. Dozens of them slept on Av. Independencia, a street behind the Alameda, in the area that is known as China Town. They benefited from some of the established shelters, which offered food and other support. However, as soon as the Alameda reopened, many rough sleepers returned to the park. Their experience in Mexico City demonstrates their long-term resistance and contestation to urban policies and social programmes.

The Alameda for livelihoods

Informal street trading is an essential part of the urban economy of many cities in Latin America and Mexico (Bromley and Mackie Citation2009; Donovan Citation2008; Jones and Varley Citation1994). Although various policies have been targeted against street vendors in the historic centre, vendors have found ways to challenge and [re]negotiate policies on a day-to-day basis (Crossa Citation2016; Giglia Citation2013; Jaramillo Puebla Citation2007).

Street trading still occurs in the Alameda every day. Vendors often carry movable trolleys, boxes, bags, backpacks or trays, circulating the fountains or moving from alley to alley. A group of disabled elderly vendors on wheelchairs offers small products such as snacks and cigarettes, which they carry on small trays or boxes on their laps. During special events, other vendors sell specific products: toys, stickers, t-shirts and costumes. Street vendors offer snacks and beverages. Some products are targeted at kids and children, such as bubble wands, helium balloons or candy floss. During rainy days, some sellers stand outside the metro entrances, offering umbrellas or plastic capes.

Artists and craft makers also sell their products in the Alameda. One of them said that the park is a hub where they can advertise their work by providing their business cards and social media profiles, hoping that visitors later request their services.Footnote12 The Alameda is also a stage for street performers, who get voluntary donations in return. Every day, from 5 to 8pm, a group of five to eight clowns arrive at the park. They sit and mingle on benches close to the statue of Beethoven, where they perform. As soon as the clowns start their show, dozens of kids and their parents move closer. Each performance lasts for 20 to 50 minutes. In the end, clowns circulate a hat or small bag asking for donations, and the second group of clowns prepare for their performance. Singers and musicians operate in similar ways. They perform a few metres away from the clowns on the eastern edge of the park.

During the COVID-19 closure of the Alameda, many street vendors and artists faced difficulties in earning their livelihoods. Some vendors moved to adjacent streets where they could still sell their products, but streets were empty.Footnote13 Others benefited from some social policies and cash transfer programmes that the national and city governments established in response to COVID-19.Footnote14 The displacement of vendors exemplified some forms of ‘old inequalities and new struggles’ of the urban poor in the Mexican context (Navarrete Citation2021, 124). As soon as the Alameda reopened, street vendors, performers and artists returned to the park, demonstrating a form of longstanding resistance to policies and social surveillance.

The Alameda for companionships

The Alameda has long received gay populations, who use the park as a ‘cruising’ place and belong to low-income populations (Hernández Cordero Citation2013; Makowski Citation2004; Meneses Reyes Citation2016). Some of these gay populations mentioned during interviews that they prefer gathering at the Alameda without having to consume or spend in gay bars.

On 5 April 2020 around 6pm, a dozen older adults, who identify themselves as gay, talk loudly on the benches close to the Fountain of Mercury, on the western edge, which they occupy every day from 5 to 8pm. They either work or live around the historic centre and meet at the park after working hours. The gay adults gather in the park to socialize, talk, joke, gossip or find sexual companions. For example, Miguel, a gay person in his 70s years of age, mentioned that those benches are one of the only places where they can meet gay friends freely and find some companions.Footnote15 Miguel also said that some of them are too old to use any mobile app to meet people or go to the Zona Rosa [‘Pink Zone’], an area famous for the LGBTQ+ community in Mexico City. Although LGBTQ+ populations have been more included in the Mexican context in recent decades, self-recognition has been a challenge for some elderly gay men, who have long tended to deny or hide their sexual preferences (Irwin Citation2000). Some older gay men associate the park with some sort of ‘safe’ place where they can be openly gay without being disturbed.

In front of the gay community in the Alameda, a group of younger male sex workers operates discreetly, although the authorities are aware of practices of prostitution, as a senior-level city authority mentioned in an interview:

There is also an important LGBT community [in the Alameda], who socialises in a normal, open, transparent, [and] very quotidian way. But there are groups also operating, and who are linked to trata de personas [human trafficking], mostly of teenagers [men under eighteen years of age]. They use the public toilets at the Plaza de la Solidaridad for sexual encounters.Footnote16

Prostitution takes place in the Alameda despite the presence of police officers and the fact that ‘offering services’, of course, including sexual services, is forbidden in public space.Footnote17 Male sex workers tend to sit alone or in pairs on small bollards on the western edge of the park (see ). The city authorities have reported some sexual interactions between gay adults and male sex workers in the nearby public toilets in the Plaza de la Solidaridad, about 100 metres from the benches where the gay adults tend to sit. These public toilets are rarely used by pedestrians or visitors of the Alameda because there are shopping centres or public buildings that offer more comfortable and hygienic restrooms. Young male sex workers prefer to use the public toilets for a ‘fast’ sexual encounter than going further with a client, as they find it ‘safer’.

The community of elderly gay men stopped gathering in the park during its closure. Some male sex workers continued operating outside nearby metro stations or offered their services through mobile apps.Footnote18 However, some older gay men said they had faced difficulties to use such apps to find sexual companions. As soon as the physical restrictions were lifted in the Alameda, the community of elderly gay men returned. They celebrated the reopening of the place where they can be ‘freely’ gay and see or find again some ‘gorgeous men’.Footnote19 The male sex workers also returned. Their interactions in the Alameda epitomize how practices of sexuality and gender also intertwine with everyday life and public space.

Social and spatial changes during the COVID-19 pandemic

Social practices of homelessness, street vending or male prostitution are continuously associated with the Alameda’s morphology. The places where these practices occur are also related to the position of benches, trees, fountains and monuments. shows a comparison of the observations on 5 April 2020, a day before the closure of the Alameda, and 7 April, a day after closure, and the visibility graph analysis.Footnote20 (top) shows that the predominant position of homelessness, street vending, street performances and prostitution corresponds to the level of ‘visual connectivity’ in the park, meaning that there are more- and less-visible areas in the Alameda. Some visitors, thus, benefit from a place where they can see others to a greater extent, being less seen by others.

Figure 3. Groups in the Alameda and visual connectivity on 5 April (top) and 7 April 2020(bottom).

The analysis demonstrates a significant correspondence and deviations between the degree of visibility and the ways these groups tend to use the park. Although the analysis shows that Av. Hidalgo, on the north, has the most visually connected areas, there are fewer visitors and passers-by there than on Av. Juárez, on the south, which is often more active. This might be because the south edge is located in the middle of the Monumento a la Revolución, Palacio de Bellas Artes and the Zócalo (see ). Some social uses, however, correspond with visual connectivity, particularly those informal practices of vendors, street performers, homeless people and male sex workers. Street vendors, for example, move across the most visible places in the park, including entrances to metro stations. Street performers use Angela Peralta pedestrian street, which is more visually connected and accessible. On the western edge, the community of elderly gay men occupy benches where they can see others, being less seen, whereas male sex workers benefit from the position of the public toilets on Plaza de la Solidaridad and the nearby presence of elderly gay men. Homeless people take the most hidden spots in the park, sleeping in the gardens between the centre of the park and Bellas Artes square.

The analysis supports the idea that physical qualities of space cannot be lost in political thoughts or social practices (De Certeau Citation1984). [Physical] space also encourages or supports practices, in this case, the activities of some disadvantaged populations. The physical qualities of the Alameda also changed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The implementation of an accumulation of physical restrictions changed the Alameda’s degree of visibility and accessibility, and thus, the practices that occur in the park, as shown in (bottom).

A medium- or long-term effect of COVID-19 urban policies?

The restrictions in the Alameda had changed since April 2020. The park reopened in early August 2020, but police officers continued as usual. By January 2021, a colourful placard of Susana Distancia continued blocking the access to the bandstand and the Hemiciclo. By December 2022, all the COVID-19 restrictions were lifted, including the colourful placards, but police officers remained.

The Alameda returned to ‘normal’, without any significant change after the COVID-19 policies. It continued offering a place for social diversity, which also reflects different forms of inequality. Social differences are hardly reflected in Mexican urban policies, which have long tended to see the historic centre as an accumulation of ‘empty’ heritage buildings, squares and streets. A lack of recognition of social diversity and inequalities have long remained in urban policies in Mexico City’s historic centre, such as the 2011 and 2017 Comprehensive Management Plans.

These limitations have continued in urban policies and protocols during and after the pandemic, as mentioned in the 2020 General Guideline for the Mitigation and Prevention of COVID-19 in Open Public Spaces. More recently, the city authorities have enacted new official protocols to be followed during protests in historic public spaces. Fluctuating ‘tolerance’ policies to street trading in the Alameda have also remained, as part of a permanent social surveillance strategy in the historic centre. The end of the pandemic did not make any major change in urban policies or urban design proposals in the ‘post-COVID’ Mexico City. A deeper understanding of the populations that use the Alameda, and public spaces, in general, would perhaps help to enact policies that respond more effectively to the social context of Mexico City. This implies urban policies that align both to the needs of residents and to global crisis, such as the pandemic.

Conclusions

While the COVID-19 pandemic has recently come to an ‘official’ end, cities and public spaces worldwide returned to a ‘new normality’. Urban scholars have debated the implications of a ‘post-COVID city’ (Batty et al. Citation2022; Florida, Rodríguez-Pose, and Storper Citation2021). In the Alameda and the historic centre, social practices, some of them informal or even illegal, returned to ‘normal’. The return of practices of homelessness, begging, street vending and/or prostitution demonstrates how expressions of inequalities have persisted in the Mexican context. These insights shed new light on ongoing debates on the ‘post-COVID city’ and the ‘new normality’, which in this case, was not so ‘new’ after all. The Alameda Central indeed returned to be as it was before its closure. In the Mexican context, the end of city lockdowns did not provide any significant lesson for promoting more ‘inclusive’ urban spaces, as urban scholars speculated in different contexts in the early stages of the pandemic (Florida Citation2020; Melis et al. Citation2020). Of course, it would be certainly naïve to suppose that the end of restrictions and policies to address the pandemic would create greater urban equity without major attention to deeply rooted inequalities.

Social practices in the Alameda show how disadvantaged groups claim and appropriate urban space. More generally, the closure of the Alameda exemplified some social effects of the pandemic on public space. The research also demonstrated that the physical features of the park support some practices of disadvantaged populations, which correlates to the degree of visibility. These attributes changed temporarily during COVID-19. In other words, physical space helps to support and maintain social practices of these disadvantaged groups.

The analysis of the lockdown of the Alameda confirmed that the meanings of public space are relative; they depend on their users. The study examined how COVID-19 policies unfold when they touch the ground of inequalities profoundly embedded in public spaces in Mexico City. The closure of the Alameda helped to prevent crowds from gatherings in the park, in an effort to decrease COVID-19 transmissions. A metal hoarding and fence, safety plastic tape and police officers finally dissuaded most people from using the park. But lockdown in the Alameda signified different things to different populations, depending on their practices and necessities, reminding us that experiences and meanings are created through the individual or collective interaction of people and space. For street vendors, the park is a place to trade. For street performers, the Alameda is their stage. For older gay men, it is a place to mingle or find sexual companions that they can hardly find elsewhere. For the homeless, the park means shelter, while for beggars, a source of charity income. For these groups, who resisted leaving the Alameda until the last moment, losing access to the park was a significant one. After all, the need for income, shelter and companionship did not disappear during the COVID-19 pandemic; and for these groups, the Alameda Central played a role in this respect that could not easily be replaced.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Ann Varley, Paulo Drinot, Michael Short, Pablo Sendra, Luz Frías and the UCL Urban Design Research Group (UDRG) for their comments and suggestions on different stages of this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Interview with a beggar in the Alameda, 06/04/2020.

2. Interview with a homeless person, 06/04/2020.

3. Interview with an old gay person, 07/04/2020.

4. The term Alameda derives from álamos [poplar trees]. The alamedas were originally planned across Spain and Latin America.

5. By late April 2023, Mexican official data reported 7.57 million positive cases of COVID-19, including 333,766 deaths in Mexico. In Mexico City, 1.88 million confirmed cases and 44,140 deaths were reported (Gobierno de México Citation2020a).

6. All interviews were conducted in Spanish and translated into English. All participants’ names were anonymized and/or changed to protect personal data.

7. CCTV cameras are streaming online 24 hours. However, the streaming is not recorded for later consultation. Available at https://www.webcamsdemexico.com/webcam-mexico-latinoamericana-oeste (last accessed 19/04/2023).

8. Interview with a street sweeper, 06/042020.

9. There are six shelters in alcaldía Cuauhtémoc. Available at www.proteccioncivil.cdmx.gob.mx/comunicacion/nota/listado-de-albergues-cdmx (accessed 21/01/2023).

10. Interview with a homeless person, 05/04/2020.

11. Interview with a senior-level city authority, 04/12/2019.

12. Interview with a young artist, 14/12/2019.

13. Interview with a street vendor, 08/01/2023.

14. Some street vendors benefited from cash transfer programmes that offered from $10,000 to 50,000 Mexican pesos (£445 to 2,225 approx.). Available at https://informedegobierno.cdmx.gob.mx/acciones/apoyos-economicos-a-la-poblacion/ (accessed 25/04/2023).

15. Interview with an elderly gay person, 05/01/2020.

16. Interview with a senior-level city authority, 04/12/2019.

17. Article 27 of the Ley de Cultura Cívica [Law of Civic Culture] in Section XII [last modification 07/06/2019] established that the authorities can proceed against prostitution only if the practice disturbs a third person who must report it to the authorities.

18. Interview with a male sex worker, 04/01/2023.

19. Interview with two gay men, 05/01/2023.

20. For the length of this article, the analysis of other observations was not included.

References

- Agostoni, C. 2003. Monuments of Progress: Modernization and Public Health in Mexico City, 1876–1910. Calgary, Alberta: University of Calgary Press.

- Amin, A. 2007. “Re-Thinking the Urban Social.” City 11 (1): 100–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604810701200961.

- Batty, M., J. Clifton, P. Tyler, and L. Wan. 2022. “The Post-Covid City.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 15 (3): 447–457. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsac041.

- Becker, A., and M. M. Müller. 2013. “The Securitization of Urban Space and the ‘Rescue’ of Downtown Mexico City: Vision and Practice.” Latin American Perspectives 40 (2): 77–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X12467762.

- Bromley, R. D. F., and P. K. Mackie. 2009. “Displacement and the New Spaces for Informal Trade in the Latin American City Centre.” Urban Studies 46 (7): 1485–1506. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098009104577.

- Carmona, M. 2010. “Contemporary Public Space: Critique and Classification, Part One: Critique.” Journal of Urban Design 15 (1): 123–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574800903435651.

- Crossa, V. 2016. “Reading for Difference on the Street: De-Homogenising Street Vending in Mexico City.” Urban Studies 53 (2): 287–301. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098014563471.

- De Certeau, M. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. Translated by S. Rendall. Berkeley, California: University of California Press.

- Delgadillo, V. 2016. “Selective Modernization of Mexico City and its Historic Center. Gentrification without Displacement?” Urban Geography 37 (8): 1154–1174. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2015.1096114.

- Donovan, M. G. 2008. “Informal Cities and the Contestation of Public Space: The Case of Bogotá’s Street Vendors, 1988–2003.” Urban Studies 45 (1): 29–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098007085100.

- Du, J., R. King, and R. Chanchani. 2020. Urban Inequalities during COVID-19. World Resources Institute, April 14. https://www.wri.org/blog/2020/04/coronavirus-inequality-cities.

- Florida, R. 2020, June 19. “This is Not the End of Cities.” Citylab. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2020-06-19/cities-will-survive-pandemics-and-protests.

- Florida, R., A. Rodríguez-Pose, and M. Storper. 2021. “Cities in a Post-COVID World.” Urban Studies 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980211018072.

- Gehl, J. 2001. Life between Buildings: Using Public Space. Edited by J. Koch. Copenhagen: Danish Architectural Press.

- Giglia, A. 2013. “Entre el bien común y la ciudad insular: La renovación urbana en la Ciudad de México.” Alteridades 23 (46): 27–38.

- Gobierno de la Ciudad de México. 2011. Plan Integral de Manejo del Centro Histórico de la Ciudad de México 2011–2016. Mexico City.

- Gobierno de la Ciudad de México. 2013. Plan de Manejo y Conservación del Parque Urbano Alameda Central. Mexico City.

- Gobierno de la Ciudad de México. 2017. Plan Integral de Manejo del Centro Histórico de la Ciudad de México 2017–2022. Mexico City. http://maya.puec.unam.mx/pdf/plan_de_manejo_del_centro_historico.pdf.

- Gobierno de la Ciudad de México. 2020. Sanitiza gobierno capitalino 496 espacios públicos para evitar propagación de COVID-19. Mexico City. https://www.jefaturadegobierno.cdmx.gob.mx/comunicacion/nota/sanitiza-gobierno-capitalino-496-espacios-publicos-para-evitar-propagacion-de-covid-19.

- Gobierno de México. 2020a. Coronavirus - Gob.Mx. Mexico City. https://coronavirus.gob.mx/.

- Gobierno de México. 2020b. Lineamiento general gara la Mitigación y Prevención de COVID-19 en Espacios Púbicos Abiertos. Mexico City. https://coronavirus.gob.mx/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Lineamiento_Espacios_Abiertos_07042020.pdf.

- Gutiérrez, F. 2017. “Alameda Central: El espacio público desde sus posibilidades y resistencias.” Política y Cultura 48:1A–16A. https://doi.org/10.24275/WQWC5867.

- Gutiérrez, F. 2021. “El espacio público durante la pandemia de COVID-19: El Cierre de la Alameda Central en la Ciudad de México.” In Participación Comunitaria en Proyectos de Espacio Público y Diseño Urbano durante la pandemia de la COVID-19: Experiencias y Reflexiones de Iberoamérica y el Caribe, edited by A. L. Carmona Hernández and D. Chong Lugon, 26–35. Mexico City: UN–Habitat Mexico. http://publicacionesonuhabitat.org/onuhabitatmexico/Participacion-comunitaria_COVID19_p.pdf.

- Gutiérrez, F., and I. Törmä. 2017. “Infra-Ordinario. Una descripción del espacio público en el tiempo.” Bitácora Arquitectura 35 (35): 4–15. https://doi.org/10.22201/fa.14058901p.2017.35.59677.

- Gutiérrez, F., and I. Törmä. 2020. “Urban Revitalisation with Music and Dance in the Port of Veracruz, Mexico.” Urban Design International 25 (4): 328–337. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41289-020-00116-8.

- Hall, P. 1982. Great Planning Disasters. California Series in Urban Development. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Hernández Cordero, A. 2013. “La reconquista de la ciudad: Gentrificación en la zona de la Alameda Central en la Ciudad de México.” Anuario de Espacios Urbanos, Historia, Cultura y Diseño 20:242–267. https://doi.org/10.24275/TIRV5607.

- Hillier, B., and J. Hanson. 1984. The Social Logic of Space. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Honey-Rosés, J., I. Anguelovski, J. Bohigas, V. Chireh, C. Daher, C. Konijnendijk, J. Litt, et al. 2020. “The Impact of COVID-19 on Public Space: A Review of the Emerging Questions.” Cities & Health (April): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/rf7xa.

- Irwin, R. M. 2000. “The Famous 41. The Scandalous Birth of Modern Mexican Homosexuality.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 6 (3): 353–376. https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-6-3-353.

- Jaramillo Puebla, N. A. 2007. “Comercio y espacio público. Una organización de ambulantes en la Alameda Central.” Alteridades 17 (34): 137–153.

- Jones, G. A., and A. Varley. 1994. “The Contest for the City Centre: Street Traders Versus Buildings.” Bulletin of Latin American research 13 (1): 27–44. https://doi.org/10.2307/3338699.

- Leal Martínez, A. 2016. “‘You Cannot Be Here’: The Urban Poor and the Specter of the Indian in Neoliberal Mexico City.” Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology 21 (3): 539–559. https://doi.org/10.1111/jlca.12196.

- Low, S. 2000. On the Plaza: The Politics of Public Space and Culture. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Madanipour, A. 2019. “Rethinking Public Space: Between Rhetoric and Reality.” Urban Design International 24 (1): 38–46. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41289-019-00087-5.

- Makowski, S. 2004. “La Alameda y la Plaza de la Solidaridad. Exploraciones desde el margen.” Antropología. Boletín Oficial Del Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia 75:65–69.

- Melis, B., J. Antonio Lara Hernandez, Y. Mohammed Khemri, and A. Melis. 2020. “Shifting the Threshold of Public Space in UK, Algeria and Mexico during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” The Journal of Public Space 5 (3): 159–172. https://doi.org/10.32891/jps.v5i3.1387.

- Meneses Reyes, M. 2016. “Jóvenes indígenas migrantes en la Alameda Central disputas pacíficas por el espacio público.” Revista de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades 80 (January): 39–68. https://doi.org/10.28928/revistaiztapalapa/802016/atc2/menesesreyesm.

- Navarrete, F. 2021. “Las dislocaciones de la Covid-19, viejas desigualdades y nuevas batallas.” Desacatos 65:124–139.

- Roy, A. 2009. “The 21st-Century Metropolis: New Geographies of Theory.” Regional Studies 43 (6): 819–830. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400701809665.

- Törmä, I., and F. Gutiérrez. 2021. “Observing Attachment: Understanding Everyday Life, Urban Heritage and Public Space in the Port of Veracruz, Mexico.” In People-Centred Methodologies for Heritage Conservation: Exploring Emotional Attachments to Historic Urban Places, edited by R. Madgin and L. James, 177–193. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Ward, P. M. 1990. Mexico City: The Production and Reproduction of an Urban Environment. Boston, MA: G.K. Hall.

- Whyte, W. H. 1980. The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces. Washington, DC: Conservation Foundation.

- World Health Organization. 2020. “Coronavirus (COVID-19) Events as They Happen.” WHO Global. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen.

- Yin, R. K. 2014. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. 5th ed. London: SAGE.