ABSTRACT

The notion of an increased incidence of left handers among architects and visual artists has inspired both scientific theory building and popular discussion. However, a systematic exploration of the available publications provides, at best, modest evidence for this claim. The present preregistered observational study was designed to reinvestigate the postulated association by examining hand preference of visual artists who share their artistic activities as short video clips (“reels”) on the social media platform Instagram. Determining individual hand preference based on five reels for each of N = 468 artists, we identified 42 (8.97%) left handers, suggesting an incidence which is below but statistical comparable to the 10.6% expected for the general population (χ2 = 1.30; p = .25; Cohen’s w = 0.05). Also, we did not find any support for the notion that the art created by left-handed artists is of higher quality than art of right handers, as no difference in public endorsement or interest were observed (reflected by the number of likes per post or account followers). Taken together, we do not find any support for difference in artistic engagement or quality between left and right handers.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

The human brain is asymmetrically organized for various functions. Perceptive and productive language processing, for example, is typically conducted by the left hemisphere, while attention or spatial processing are considered right hemispheric functions (Ocklenburg & Güntürkün, Citation2018). Deviations from this prototypical pattern are, however, frequent (Gerrits et al., Citation2020; Karlsson et al., Citation2022; Vingerhoets, Citation2019). This is most saliently illustrated considering handedness, where roughly 10% of the population show the atypical left or mixed handedness rather than the prototypical right-hand preference (Papadatou-Pastou et al., Citation2020). The functional consequences of atypical lateralization for cognition are little understood, although detrimental effects for cognition are typically reported (e.g., Gerrits et al., Citation2020; Powell et al., Citation2012). However, the influential Geschwind-Behan-Galaburda (GBG) theory of brain development (Geschwind & Behan, Citation1982; Geschwind & Galaburda, Citation1985a, Citation1985b) predicts that atypically lateralized individuals are especially talented for skills which are thought to be controlled by the right hemisphere. In brief, the GBG theory postulates that the exposure to intrauterine testosterone leads to a maturation delay of the foetal brain, particularly affecting the left hemisphere, as well as an accentuated growth of the right hemisphere in compensation for the delayed growth of the left. A protracted length of exposure to testosterone is consequently predicted to ontogenetically modulate brain lateralization in favour of the right hemisphere, resulting in atypical lateralization (see also McManus & Bryden, Citation1991). Among the evidence provided, Geschwind and Galaburda (Citation1985a, Citation1985b) cite an elevated rate of left or non-right handedness in architects and visual artists (citing Peterson, Citation1979; Peterson & Lansky, Citation1974), assuming that the visual-spatial processing abilities relevant for these professions are indeed controlled by the right hemisphere (Heilman & Acosta, Citation2013).

While the underlying assumptions of the GBG theory have been challenged (e.g., Bryden et al., Citation1994; Richards et al., Citation2021), the cited increased proportion of left- or non-right handed individuals in professions relying on visual-spatial processing is somewhat supported by the literature, although differences in the definition of the professions or handedness grouping make a comparison between studies difficult. To provide a short overview, we here summarize the findings for relevant professions. Considering architects, the first study supporting the notion, by Peterson and Lansky (Citation1974), reported that 29.4% of the faculty members (5 out of 17) and 16.3% of the students (79 of 484) of an architect school were left handers. While these percentages range well above the expected 10%, the study did not report a formal comparison with a control group. Schachter and Ransil (Citation1996), comparing students from various subjects, showed that left handedness had the highest incidence in students of architecture (17.6%; or 26 of 148) which was increased compared to the 10.1% of the total sample. Götestam (Citation1990) finds an increased percentage of left-hand writers (13.3%; or 8 of 60) among students of architects as compared with a non-artistic controls. However, Wood and Aggleton (Citation1991) did not confirm these previous observation reporting 10.2% (24 of 236) left handers among qualified professional architects and 11.5% (9 of 78) left handers among architecture students, both reflecting the expected population-level incidence. Also, one smaller study did not find differences in incidence levels between permanent faculty members from architecture compared with law or psychology (Shettel-Neuber & O'Reilly, Citation1983). Extending beyond architecture, by including other visual arts (e.g., design, fine arts) in a combined analysis, Peterson (Citation1979) compared students with various majors as study subjects and found that about 12.2% (18 of 147) of the students majoring in “visual arts” were left handers as compared to 9.4% in the total sample. Also, Mebert and Michel (Citation1980) reported that 20% (21 of 104) of the students of fine art (i.e., training in creative artistic expression; including architecture, design, and painting) and 7% of the students of liberal arts (i.e., theoretical engagement with art) were left-handed. In contrast, Cosenza and Mingoti (Citation1993) found that 8% (46 of 577) of students applying for a course in architecture or fine arts were left handed, comparable to the 7.5% in the total sample across all university courses. Interestingly, only three studies selectively report handedness of artistic painters. Preti and Vellante (Citation2007) report that 20% (5 of 25) included painters were non-right handed, compared with 3% in a control sample, while Shettel-Neuber and O'Reilly (Citation1983) do not find differences between faculty members from art and other schools (Shettel-Neuber & O'Reilly, Citation1983). Finally, rather than studying contemporary professional training, Lanthony (Citation1995) retrospectively inferred the hand preference of painters from historical material and the style of painting. Although historical reference numbers for the incidence of left handers vary substantially (e.g., McManus, Citation2009), the number of 2.8% (14 of 500) identified left-handed artists by Lanthony (Citation1995) likely does indicate an under- rather than over-representation of left handers.

Taken together, despite the inconsistencies between studies, it appears that at least for architecture an increased incidence of left handedness cannot be excluded. However, for visual artists (e.g., artistic painters) the evidence is weak, as only two studies (Preti & Vellante, Citation2007; Shettel-Neuber & O'Reilly, Citation1983) provide contemporary data that clearly distinguish this group from other artistic activities (e.g., music or performance art; see e.g., Giotakos, Citation2004; van der Feen et al., Citation2020), together providing only a modest sample size. Thus, the present preregistered study (see Røsvoll & Westerhausen, Citation2022) was designed to examine whether the prevalence of left handedness is increased in individuals engaged in visual artistic activities, focussing on artists creating two-dimensional art (e.g., by painting or drawing activities; following Lanthony, Citation1995; Preti & Vellante, Citation2007). This investigation was operationalized as an observational study, designed to determine hand preference of artists who present their work as short video clips (so-called “reels”) on the social media platform Instagram (Laestadius, Citation2016). The visual nature of Instagram, primarily allowing users to share photos and “reels”, makes it naturally suited for visual artists to present, discuss, or market their work (Kang et al., Citation2019), making it a perfect forum to observe artists in large sample size. It was predicted that artists are more often left handers than the general population. However, the GBG theory also predicts a higher talent for right-hemispheric functions in atypically lateralized individuals (Geschwind & Galaburda, Citation1985a, Citation1985b). This is in line with previous observations of a superior performance in left-handed as compared with right-handed architects (Peterson & Lansky, Citation1977) and the higher perceived quality of left- as opposed to right-handed drawings (Magnus & Laeng, Citation2006). Thus, we here additionally predicted that left-handed artwork is considered superior. This hypothesis was explored by comparing the engagement by the public with the art product (considering “likes” and the number of followers on Instagram) between left- and right-handed artists. It has been shown previously that such social-media endorsement represents a positive evaluation of the content and good measure of aesthetic appeal (Hayes et al., Citation2016; Thömmes & Hübner, Citation2018).

Material and methods

Participants

Reels for a total of 575 unique accounts of artists (henceforth “research subjects”) were evaluated for hand preference. However, to allow for reliable classification, we only included research subjects for which five reels were evaluated, leaving an N = 468. Of these, 208 (44.4%) were from artists identified as “female” and 120 (25.6%) as “male”. For the remaining 140 (29.9%) the Instagram profile did not allow such identification. The country of origin of the research subjects was 41 (8.8%) from the USA, followed by India (n = 26; or 5.6%), the United Kingdom (23; 4.9%), Germany (17; 3.6%), and France (15; 3.2%). For most artists the country of origin could not be determined (173; 37%). A complete list is presented in Supplement Table S1.

Of note, the total number of observations was above the critical N determined by an a priori sample size estimation. That is, a recent meta-analysis estimates that 10.60% of the general population are left handers (Papadatou-Pastou et al., Citation2020), while the estimate is slightly lower for women (9.53%; with 95% confidence limits, CI, of [8.75%, 10.30%]) than men (11.62%, [10.66%, 12.60%]). Using the estimate for men as a reference, we set the minimal incidence of left handers that would be of theoretical relevance in the present study to 14.6% (i.e., 2% above the upper CI estimate). This percentage falls below the levels reported in previous studies on the topic (Mebert & Michel, Citation1980; Peterson & Lansky, Citation1974; Schachter & Ransil, Citation1996). The effect size of interest was consequently calculated as Cohen’s w = 0.13 (i.e., finding a proportion of 14.6% left handers as opposed to 10.6%). Using the R package “pwr” (version, 1.3-0; Champely et al., Citation2020), a power of .80 while testing at a significance level of .05 is reached utilizing critical N = 465 observations.

The study was approved by the local ethics review board of the Department of Psychology, University of Oslo (reference number: 23322325). Given the study conducts (anonymous) observation in public space, informed consent was not considered necessary by the review board.

Data collection

Using an Instagram account created for this purpose (“rater account”), relevant artist accounts were identified by searching for posts with search terms specifying visual artistic activities or techniques with focus on painting- or drawing-related activities. The terms were ad-hoc selected by the three raters, and the five most commonly used terms were “watercolour”, “sketching”, “landscapepainting”, “aquarelle”, and “inkdrawings” (for a complete list see Supplement Table S2). We decided for an ad-hoc generation of search terms as we had no a priori knowledge which terms would be useful to identify relevant reels. The results of each search were then systematically explored starting with the account of the top-most post and moving result-by-result downwards. Each such identified account was then evaluated following a digital checklist. Firstly, for each account, it was verified that it had not already been evaluated (i.e., that it was not “followed” by therater account), that video clips (so-called “reels”) were available, and that the account provides reels of only one artist’s work (e.g., by reading through the account description, or checking for consistency in artwork/person shown in the reels). If these criteria applied, the research subject was included in the study and information about the account (number of followers and, if available, country of origin) and subject (gender, if available) were collected. Subsequently, the most recent reels were judged by the respective rater, determining with which hand the shown manual activities were performed (categories: “left”, “right”, or “both”). The categories “left” and “right” were only selected if the respective hand was used across all activities performed in the reel. Two examples for how these reels looked can be seen in . Additionally, per reel, the “number of likes” and the “time since posting” (in days) was recorded as well as what instrument was used (e.g., brush, pencil, pen, charcoal, see Supplement Table S3). The evaluation stopped when five reels with manual activity were evaluated, or no further reels were available on the account. Finally, to ensure that each research subject’s account was only evaluated once, the “rater account” started “following” the evaluated account.

Figure 1. Screenshot of an example reel for a left- and right-handed artistic activity. Screenshot taken and used with permission by the artists (left: Naomi Vona, @mariko_koda; right: Ebtehal Salah; @ebtehal_drawing). Note: neither of the two artists is part of the present sample. [To view this figure in colour, please see the online version of this journal.]

![Figure 1. Screenshot of an example reel for a left- and right-handed artistic activity. Screenshot taken and used with permission by the artists (left: Naomi Vona, @mariko_koda; right: Ebtehal Salah; @ebtehal_drawing). Note: neither of the two artists is part of the present sample. [To view this figure in colour, please see the online version of this journal.]](/cms/asset/ccbf0fa1-38dd-47bb-afe5-c73460c316f1/plat_a_2315856_f0001_oc.jpg)

The data collection was conducted by three raters, each evaluating different accounts. However, the interrater reliability for the hand-preference classification examined was determined for 50 randomly selected reels that were independently evaluated by all three raters. Using the “irr” package in R (version 0.84.1; Gamer et al., Citation2021), Cohen’s Kappa for the three combinations of rater pairs were κ = 1, .898, and .898, respectively. The Fleiss’ Kappa for inter-rater agreement of all three raters was κ = .934, which indicates excellent agreement (Fleiss et al., Citation2013).

Considering the main data collection, 2650 reels of the 575 unique research subjects were evaluated. For 468, the evaluation of 5 reels was available. For additional 40 subjects the evaluation of four reels was available, for 25 of three reels, for 29 for two reels, and for 11 for one reel. However, in accordance with the preregistration, only the data of the N = 468 research subjects for which the evaluation of five reels was available were included in the main analyses.

Handedness classification

The included research subjects were classified into left- and right-handed based on the dominant hand preference demonstrated across the five reels. Following the preregistration, a research subject was classified as “left-handed” when at least 3 of the 5 reels indicated a left-hand preference, and all others were counted as “right-handed”. This criterion (as opposed to more strict definition) enabled us to determine the preferred hand by the research subject, while it also tolerates variance in our classification (i.e., between reels of the same subject) resulting from the complexity of the artistic activities. For example, artists might use their subdominant hand for secondary/supporting activities (e.g., soften the edges of a drawing with the left hand while the right does the drawing) which would be classified as activity of “both” hands. Of note, one participant had no clear hand preference across reels, which was classified as right-handed following our criterion. As one might argue that this participant should be excluded as not showing a preference, we reran all analyses without this data point, which did not substantially change the outcome and will not be reported here.

To check for non-randomness of the data collection, a Wald-Wolfowitz runs test was performed on the handedness classification variable considering the order in which the accounts were evaluated (using the “randtest” R package, version 1.0.1; Caeiro and Mateus, Citation2022). The sequences consisted of 79 runs of the same classification, and the Wald–Wolfowitz test yielded a Z = 0.44 with p = .66, suggesting the sequence of the data collection was random.

Likes per day (LPD) and number of followers (NOF)

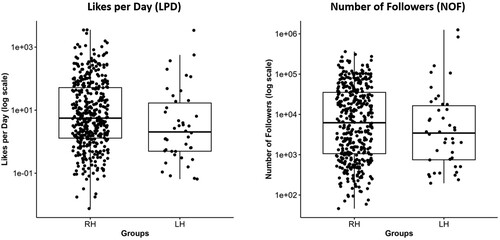

The total number of likes of the evaluated accounts ranged from 6 to 251,301 across the five reels with a mean M = 1414.5 (SD = 6495.8). The average time the reels were posted varied from 1.2–1864 days (M = 113.0, SD = 913.5 days). The variable Likes per Day (LPD) was calculated by dividing the sum of all likes across the reels by the time since the reels were posted (in days, as sum across reels). This approach was chosen as the number of likes increases with the time since posting. The LPD variable ranged from resulting 0 to 3535.5 and had a mean of M = 95.1 (SD = 348.0). The average Number of Followers (NOF) was M = 31,798.7 (SD = 82,864.0) and varied from 46 to 1,254,979 between the accounts. As can be seen in Supplement Figure S1, for both LPD and NOF the distribution followed an exponential decay from low to high values, with a few extreme values dominating the mean. Comparably to what was reported by Kang et al. (Citation2019), LPD and NOF were positively (Spearman’s rsp = .67, p < .001), although not perfectly, related warranting a separate analysis.

Statistical analysis

To test the first prediction, and following the procedure stated in the preregistration (Røsvoll & Westerhausen, Citation2022), the observed incidence of left handed individuals was compared against the expected proportion of 10.6% (taken from the meta-analysis by Papadatou-Pastou et al., Citation2020) using a “Goodness-of-fit” chi-squared test. To test the prediction of higher art quality, a t-test with the degrees of freedom adjusted for difference in the variance between the two groups was conducted for the dependent variable LPD. However, as the variable LPD was not normally distributed, we additionally conducted a Mann–Whitney U test (deviating from the registration). As a second (explorative) test of hypothesis 2, we repeated the analysis using NOF as a dependent variable (using a Mann–Whitney U test) and compared the proportion of left handers among Instagram accounts with high and low median NOF (chi-squared test of independence). In the latter analysis, a significantly increased proportion of left handers in the above median sample would support hypotheses 2. All analyses were conducted in R (version 4.2.3).

Data availability statement

The data and R scripts used in the analysis are available via the accompanying OSF folder (https://osf.io/3bzj7/).

Results

Forty-two (or 8.97%) of the 468 research subjects were classified as left handers and 426 (91.02%) as non-left handers. Thus, the incidence of left handers was below the expected 10.6%. Nevertheless, comparing the observed with the expected distribution yielded a χ2 = 1.30 (df = 1), which was not significant (p = .25; Cohen’s w = 0.05).

The mean LPD for left handers was M = 119.2 (SD = 531.2) and for the right handers M = 92.7 (SD = 325.2), with the mean difference pointing in the expected direction. The one-sided t-test was, however, not significant (t = 0.47, df = 466, p = .32; d = 0.08). Adjusting for unequal variance did not affect the outcome substantially (t = 0.32, dfadj = 40.8, p = .38; d = 0.05). Considering the non-normal distribution of the LPD variable (see , left panel), we found the median value of Md = 5.59 for right handers and Md = 2.04 for left handers, in contrast to the prediction. A two-sided U-test indicated that this difference was statistically significant (W = 10,894, p = .02, r = .11). As for LPD, the mean NOF of the research subject’s account was nominally larger in left (M = 64,689, SD = 229,029) than right handers (M = 28,556, SD = 48,655), while the median was larger in right handers (left handers: Md = 3450, right handers: Md = 6212; see , right panel). The U-Test did not indicate a significant difference between the two groups (W = 10,078, p = .176, r = .06).

Figure 2. Box plot of LPD (left) and NOF variables (right), showing the comparison between right-handed (RH) and left-handed (LH) research subjects. The median LPD was found to be significantly reduced in the LH compared to the RH group (effect size: r = .11), while the differences in NOF (r = .06) was not statistically significant. Note: the values on the y-axis are log-transformed for readability.

Comparing Instagram accounts above and below the median NOF, we found a proportion of 0.11 and 0.07 of the below and above median accounts to be left handers. The difference in proportion was not significant (χ2 = 1.67, df = 1, p = .20; w = 0.06).

Discussion

In contrast to our predictions, the present study did not find an increased incidence of left handers in the sample of visual artists presenting their work on Instagram, nor did the art presented by left handers attract more “likes” or followers than the work of right handers. In this, our study does not support the findings of previous studies (Mebert & Michel, Citation1980; Peterson & Lansky, Citation1974, Citation1977; Schachter & Ransil, Citation1996) and contradicts the predictions made by GBG theory (Geschwind & Behan, Citation1982; Geschwind & Galaburda, Citation1985a, Citation1985b; McManus & Bryden, Citation1991). However, the present study did differ in several aspects from previous studies which require consideration when interpreting the present findings.

As summarized in the introduction, previous studies that report an increase in left handers in professions relying on visual-spatial processing, mainly studied architects or students of architecture and not visual artists, like artistic painters. Nevertheless, like for architects, the skills required of visual artists (e.g., visual imagery, constructive spatial abilities) are dominantly controlled by the right hemisphere (e.g., Chamberlain et al., Citation2014; Corballis & Sergent, Citation1989; Heilman & Acosta, Citation2013) and predictions based on the GBG theory model should also apply to this group. The few studies which do focus on visual artists mostly show negative findings (Cosenza & Mingoti, Citation1993; Lanthony, Citation1995; Shettel-Neuber & O'Reilly, Citation1983), with two exceptions (Mebert & Michel, Citation1980; Preti & Vellante, Citation2007). A study by Mebert and Michel (Citation1980) finds an increased proportion of left handers among students of fine art. The authors do not, however, specify the specialization of the students within the fine arts, so it is not clear how many of the students were trained as visual artists, rather than in architecture or in other subfields. A second study, by Preti and Vellante (Citation2007), reports that of 25 included painters, 5 (20%) were non-right handers, which was increased compared to a control sample, but the small sample size limits the conclusions that can be drawn. Taken together, the arguably limited prior evidence does only provide modest support to the notion that left handers are overrepresented among visual artists. The findings of the present study—also by reporting the largest sample available to date—do additionally reject this notion with acceptable test power. We can only speculate why left handers should be more strongly represented among architects but not in other visual artists. The present sample consisted mainly of artists producing two-dimensional art (e.g., through painting and drawing) while architects aim for a three-dimensional product. Differences in the cognitive demands for the integration of the third dimension in the product (e.g., mental rotation) might require a stronger engagement of the right hemisphere (e.g., Corballis & Sergent, Citation1989; Heilman & Acosta, Citation2013), somehow benefiting left-handed architects. However, any such interpretation is highly speculative and requires more empirical evidence.

A second difference to previous studies can be found in the level of professionality of the research subjects. That is, almost all previous studies examined students in training or professional artists and architects, while our study was not able to distinguish professional from amateur or recreational artists, as this information cannot reliably be extracted from the Instagram accounts. Assuming left handedness increases the chance for a successful transition from amateur to professional engagement with the visual arts, the inclusion of amateurs in our sample could have masked a possible increase found in professionals. Support for this interpretation could be seen in the findings by Peterson and Lansky (Citation1977), showing that left-handed students were proportionally more likely than right handers to graduate in architecture, suggesting a selection bias towards left handers based on higher skills. Also, positive stereotypes in the society (Grimshaw & Wilson, Citation2013) might result in left handers seeing themselves as more creative (van der Feen et al., Citation2020) and lead to self-selection in favour of a professional artistic career. Thus, we cannot rule out that the inclusion of amateur artists affects the prevalence of left handers in our study in a systematic way. However, also for professional/historical painters the evidence for an increased incidence of left handers is, at best, weak (Lanthony, Citation1995; Preti & Vellante, Citation2007; Shettel-Neuber & O'Reilly, Citation1983) so that a more parsimonious interpretation might be that there is no effect, rather than attributing the present null findings to the mixture of amateur and professional artists in our sample.

Previous studies reporting an increased incidence of left handers, studied Western samples (mainly the USA, e.g., (Mebert & Michel, Citation1980; Peterson, Citation1979; Peterson & Lansky, Citation1974, Citation1977; Schachter & Ransil, Citation1996); as well as Italy, see Preti & Vellante, Citation2007, and Norway, Götestam, Citation1990) with background in higher education (e.g., university students and staff) and an overrepresentation of male participants (Peterson & Lansky, Citation1974, Citation1977; Schachter & Ransil, Citation1996). Compared with these samples, the present study—as far as we can infer from the available data—includes more research subjects from non-Western societies (see Supplement Table S1), more women (see Participants section), and likely a less restricted sample regarding educational attainment than previous samples (see Kang et al., Citation2019). Such deviations in the sample between studies may affect our results systematically, if the association of left-handedness and engaging in artistic activities is particularly strong in Western men with high education attainment. In this case, the inclusion of subsamples in which such association is not found would potentially conceal the effect. As for a significant amount of our research subjects information regarding sex or country of origin is not available, it is not possible to test this speculation in a meaningful way using the present data. Nevertheless, the GBG theory should apply independently of these variables, and our study does not support the predicted general association.

One limitation of the present study is that we did not assess hand preference in a non-artist control sample and rather compared the incidence with the proportions estimated by a recent large scale meta-analysis (Papadatou-Pastou et al., Citation2020). The main reason for not including a control sample, was the unavailability of a suitable comparison group. That is, a group characterized by drawing-like activities, which would not rely on supposed right-hemispheric functions and presents reels on Instagram. Nevertheless, it is our belief that the used incidence rates are well-suited as reference values, as the meta-analysis included a wide range of studies, integrating data from all over the globe and various educational backgrounds, as is the case for our study. A related concern might be the exact reference value we used, as the meta-analysis provides several estimates depending on the handedness classification strategy used by the original studies. The here used reference value of 10.6% of expected left handedness (referred to as "total" estimate by Papadatou-Pastou et al., Citation2020) included all data sets included in the meta-analysis. That is, it represents the integration of data from studies defining left handedness as opposed to right handedness, left- as opposed to mixed and right handedness, as well as “non-right” handedness. Alternative incidence number are provided for a “forced choice” classification (10.20%; i.e., when studies compared left with right handers), and a consistent classification (9.34%; i.e., left handedness in studies which included a mixed-handed group). Of note, however, both alternative estimates are above rather than below the empirical estimate of 8.97% of left handers in our sample, and a test against these values would have led to the same statistical conclusion. Another limitation is that our handedness classification was based on the (repeated) observation of (mostly) one type of manual activity (e.g., drawing with a pen or painting with a brush) while handedness is typically assessed with a multi-item self-report questionnaire (e.g., Papadatou-Pastou et al., Citation2013). Maybe most comparable to our approach are classifications based only on the hand preference for writing, as the hand preference for drawing and writing is highly concordant and correlated (Dragovic, Citation2004; Raaf & Westerhausen, Citation2023). Selectively summarizing studies using only writing hand for classification, Papadatou-Pastou et al. (Citation2020) provide an estimate of 9.32% of left handedness, which again is above rather than below our empirical value. Thus, taken together, irrespective of which reference value we use for comparison, the incidence of left handedness in visual artists does not seem to be increased compared to the general population.

Finally, the GBG theory also predicts higher skill or talent for right hemispheric functions in atypically lateralized individuals (Geschwind & Galaburda, Citation1985a, Citation1985b; McManus & Bryden, Citation1991; Mebert & Michel, Citation1980), which might not necessarily be reflected in the frequency of professional/recreational engagement with the activity. Thus, a higher quality of the art produced by left-handed individuals would be predicted also without a higher incidence of left handers in the artist population. We here tested this hypothesis by using virtual endorsement (i.e., LPD) and the amount of account followers (i.e., NOF) as proxies for the aesthetic quality of the artwork presented. Although the reasons for such endorsement on social media platforms are complex, one reason is the positive evaluation of the content (see e.g., Hayes et al., Citation2016) and “likes” are thought to be a good measure of aesthetic appeal of pictures presented on Instagram (Thömmes & Hübner, Citation2018). Nevertheless, our study did neither for LPD nor NOF find a group difference in favour of left-handed artists, thus not confirming the above prediction. Additionally, comparing accounts above and below the median NOF, we did not find a substantial difference in the proportion of left handers. Again, one might speculate why we did not find the predicted difference in artistic talent. Repeating the arguments from the discussion above, the difference might specifically show in professional artists or in artist producing three-dimensional art but not in the present “mixed” sample. Alternatively, one may simply conclude that the prediction of higher talent in left handers is wrong. Taken together, we do not find any indication that left handedness is associated with a higher artistic quality (at least when operationalized as public engagement with the artists’ accounts).

In summary, by selectively focussing on visual artists, the present observational study does not provide any indication that left handers are overrepresented among artists or produce artwork of higher quality. This is in line with the observation that left handers, although considering themselves more creative than right handers, do not engage in more artistic activities (van der Feen et al., Citation2020). Of note, however, considering the GBG theory, the association between atypical handedness and talent for visual-spatial processing are correlational and not functional, as a common cause (the compensatory right hemispheric development) is supposed to have determined both hand preference and talent (Geschwind & Galaburda, Citation1985a, Citation1985b). Alternatively, a causal relationship might be construed, namely that using the left hand as the dominant hand for artistic output, results in a direct expression of right-hemispheric visuo-spatial functions, as here both planning and output are controlled by the same hemisphere (Heilman & Acosta, Citation2013; Mebert & Michel, Citation1980). In line with this assumption, drawings done with the left hand are judged to be superior to drawings made with the right hand in artists trained (Magnus & Laeng, Citation2006) or forced (after stroke; see Sherwood, Citation2012) to use the subdominant left hand for drawing. From this, it can be argued that considering (left) handedness alone is a suboptimal approach for studying the relationship between artistic expression and right hemispheric visual-spatial functioning. For example, left-handed individuals are also more likely to be atypically (left-ward) lateralized for visuo-spatial functions (e.g., Gerrits et al., Citation2020), so that in these left-handed artists the right-hand art should be more expressive. Consequently, future studies might benefit from studying the directly relating hemispheric lateralization for visual-spatial abilities to artistical expression, rather than studying handedness alone.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (108.2 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Bryden, M. P., McManus, I., & Bulman-Fleming, M. B. (1994). Evaluating the empirical support for the geschwind-behan-galaburda model of cerebral lateralization. Brain and Cognition, 26(2), 103–167.

- Caeiro, F., & Mateus, A. (2022). randtests: Testing Randomness in R (version 1.0.1). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package = randtests.

- Chamberlain, R., McManus, I. C., Brunswick, N., Rankin, Q., Riley, H., & Kanai, R. (2014). Drawing on the right side of the brain: A voxel-based morphometry analysis of observational drawing. Neuroimage, 96, 167–173.

- Champely, S., Ekstrom, C., Dalgaard, P., Gill, J., Weibelzahl, S., Anandkumar, A., & De Rosario, H. S. (2020). pwr: Basic functions for power analysis (version 1.3). https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/pwr/.

- Corballis, M. C., & Sergent, J. (1989). Hemispheric specialization for mental rotation. Cortex, 25(1), 15–25.

- Cosenza, R. M., & Mingoti, S. A. (1993). Career choice and handedness: A survey among university applicants. Neuropsychologia, 31(5), 487–497.

- Dragovic, M. (2004). Towards an improved measure of the Edinburgh handedness inventory: A one-factor congeneric measurement model using confirmatory factor analysis. Laterality: Asymmetries of Body, Brain and Cognition, 9(4), 411–419.

- Fleiss, J. L., Levin, B., & Paik, M. C. (2013). Statistical methods for rates and proportions. john wiley & sons.

- Gamer, M., Lemon, J., Fellows, I., & Singh, P. (2021). irr: Various Coefficients of Interrater Reliability and Agreement (version 0.84). https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/irr/.

- Gerrits, R., Verhelst, H., & Vingerhoets, G. (2020). Mirrored brain organization: Statistical anomaly or reversal of hemispheric functional segregation bias? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(25), 14057–14065.

- Geschwind, N., & Behan, P. (1982). Left-handedness: Association with immune disease, migraine, and developmental learning disorder. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 79(16), 5097–5100.

- Geschwind, N., & Galaburda, A. M. (1985a). Cerebral lateralization: Biological mechanisms, associations, and pathology: I. A hypothesis and a program for research. Archives of Neurology, 42(5), 428–459.

- Geschwind, N., & Galaburda, A. M. (1985b). Cerebral lateralization: Biological mechanisms, associations, and pathology: II. A hypothesis and a program for research. Archives of Neurology, 42(6), 521–552.

- Giotakos, O. (2004). Handedness and hobby preference. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 98(3), 869–872.

- Götestam, K. O. (1990). Lefthandedness among students of architecture and music. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 70(3_suppl), 1323–1327.

- Grimshaw, G. M., & Wilson, M. S. (2013). A sinister plot? Facts, beliefs, and stereotypes about the left-handed personality. Laterality: Asymmetries of Body, Brain and Cognition, 18(2), 135–151.

- Hayes, R. A., Carr, C. T., & Wohn, D. Y. (2016). One click, many meanings: Interpreting paralinguistic digital affordances in social media. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 60(1), 171–187.

- Heilman, K. M., & Acosta, L. M. (2013). Visual artistic creativity and the brain. Progress in Brain Research, 204, 19–43.

- Kang, X., Chen, W., & Kang, J. (2019). Art in the age of social media: Interaction behavior analysis of Instagram art accounts. Informatics, 6(4), 52.

- Karlsson, E. M., Johnstone, L. T., & Carey, D. P. (2022). Reciprocal or independent hemispheric specializations: Evidence from cerebral dominance for fluency, faces, and bodies in right- and left-handers. Psychology & Neuroscience, 15(2), 89.

- Laestadius, L. (2016). Intagram. In L. Sloan, & A. Quan-Haase (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of social media research methods (pp. 573–592). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Lanthony, P. (1995). Left-handed painters. Revue Neurologique, 151(3), 165–170.

- Magnus, R., & Laeng, B. (2006). Drawing on either side of the brain. Laterality: Asymmetries of Body, Brain and Cognition, 11(1), 71–89.

- McManus, I. (2009). The history and geography of human handedness. In E. C. Sommer, & R. S. Kahn (Eds.), Language lateralization and psychosis (pp. 37–57). Cambridge University Press.

- McManus, I., & Bryden, M. (1991). Geschwind's theory of cerebral lateralization: Developing a formal, causal model. Psychological Bulletin, 110(2), 237–253.

- Mebert, C., & Michel, G. (1980). Handedness in artists. In J. Herron (Ed.), Neuropsychology of left-handedness (pp. 273–278). Academic Press.

- Ocklenburg, S., & Güntürkün, O. (2018). The lateralized brain: The neuroscience and evolution of hemispheric asymmetries. Academic Press.

- Papadatou-Pastou, M., Martin, M., & Munafò, M. R. (2013). Measuring hand preference: A comparison among different response formats using a selected sample. Laterality: Asymmetries of Body, Brain and Cognition, 18(1), 68–107.

- Papadatou-Pastou, M., Ntolka, E., Schmitz, J., Martin, M., Munafò, M. R., Ocklenburg, S., & Paracchini, S. (2020). Human handedness: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 146(6), 481–524.

- Peterson, J. M. (1979). Left-handedness: Differences between student artists and scientists. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 48(3), 961–962.

- Peterson, J. M., & Lansky, L. M. (1974). Left-handedness among architects: Some facts and speculation. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 38(2), 547–550.

- Peterson, J. M., & Lansky, L. M. (1977). Left-handedness among architects: Partial replication and some new data. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 45(3_suppl), 1216–1218.

- Powell, J. L., Kemp, G. J., & García-Finaña, M. (2012). Association between language and spatial laterality and cognitive ability: An fMRI study. Neuroimage, 59(2), 1818–1829.

- Preti, A., & Vellante, M. (2007). Creativity and psychopathology: Higher rates of psychosis proneness and nonright-handedness among creative artists compared to same age and gender peers. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 195(10), 837–845.

- Raaf, N., & Westerhausen, R. (2023). Hand preference and the corpus callosum: Is there really no association? Neuroimage: Reports, 3(1), 100160.

- Richards, G., Beking, T., Kreukels, B. P., Geuze, R. H., Beaton, A. A., & Groothuis, T. (2021). An examination of the influence of prenatal sex hormones on handedness: Literature review and amniotic fluid data. Hormones and Behavior, 129, 104929.

- Røsvoll, Å, & Westerhausen, R. (2022). Hand preference in artists (Registration).

- Schachter, S. C., & Ransil, B. J. (1996). Handedness distributions in nine professional groups. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 82(1), 51–63.

- Sherwood, K. (2012). How a cerebral hemorrhage altered my art. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 6, 55.

- Shettel-Neuber, J., & O'Reilly, J. (1983). Handedness and career choice: Another look at supposed left/right differences. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 57(2), 391–397.

- Thömmes, K., & Hübner, R. (2018). Instagram likes for architectural photos can be predicted by quantitative balance measures and curvature. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1050.

- van der Feen, F. E., Zickert, N., Groothuis, T. G., & Geuze, R. H. (2020). Does hand skill asymmetry relate to creativity, developmental and health issues and aggression as markers of fitness? Laterality, 25(1), 53–86.

- Vingerhoets, G. (2019). Phenotypes in hemispheric functional segregation? Perspectives and challenges. Physics of Life Reviews, 30, 1–18.

- Wood, C. J., & Aggleton, J. P. (1991). Occupation and handedness: An examination of architects and mail survey biases. Canadian Journal of Psychology / Revue Canadienne de Psychologie, 45(3), 395-404.