ABSTRACT

Regional and Federal Studies’ 30th anniversary offers an opportunity to take stock of the state of the discipline and of the journal. We make four claims. First, the multi-level nature of the political world has intensified in the last 30 years. Second, the approaches to studying this changing world have evolved through a quantitative and comparative turn. Regional and Federal Studies has embraced these developments whilst remaining faithful to its tradition of rich conceptual and case-study work. Third, the journal has contributed to the ‘territorialization’ of mainstream political science as many fields of study have gradually recognized the limitations of national- or single-level analyses. Finally, the journal itself has diversified in terms of approaches, methods, geographical coverage, and gender balance of author profiles, although we recognize there is more to do. We view further comparative research on the Global South as a particularly important research avenue.

When Regional and Federal Studies was founded in 1991, processes of globalization and the spread of market-oriented reforms after the end of the Cold War were ushering in far-reaching changes to territorial politics and state structures across much of the world. Globalization brought with it changes to economic and political geography. Cross-border flows of capital and people empowered some subnational regions, even as they breathed further life into supranational efforts of coordinating markets and national policy regimes such as the European project.

When the journal was first created, as Regional Politics and Policy: An International Journal, its primary focus was on regionalism in Western Europe as outlined by its founding editor, John Loughlin (Citation2021), in his contribution to this anniversary issue. By 1995, the editorial team relaunched the journal under the name Regional and Federal Studies (RFS) in order to draw more systematic attention to federalism as well as regionalism due to the ‘increasing salience of the federal model of politics in Europe and elsewhere’ (Editorial statement Citation1995). Today, the journal’s ‘aims and scope’ highlight its global ambition and broad focus. They signal the journal’s intention to cut across existing substantive, thematic, geographical, theoretical, and methodological boundaries.Footnote1

On the occasion of RFS’ 30th anniversary, this article looks back on thirty years of research on regionalism, federalism and multi-level governance within and beyond the journal. The first section traces the real-world developments that have raised the importance of the subnational and supranational levels of government across the world. The second part assesses how the field of territorial politics itself has changed during the past thirty years, as its substantive and methodological insights about the importance of space and scale have penetrated mainstream political science. This is followed by an investigation into how the journal itself has developed during its thirty years of existence, in terms of the main topics and cases covered, methods used, and perspectives adopted. We close this introduction with an overview of the eight contributions included in the issue. The issue covers substantively important topics concerning the origins of territorial autonomy, the past and future of multinational federalism, the quality of government divided across territorial levels and the continued dilemmas presented in multi-level systems for the strengthening of welfare states and the governance of cities. The issue as a whole studies these questions in cases from different world regions and it does so with a keen awareness of both the opportunities and limits of generalization. We believe this anniversary issue demonstrates where RFS is heading at the beginning of its fourth decade.

Regionalism, federalism and the shifting scales of multi-level governance

When the journal was established, the federal idea was entering centre-stage in Europe as a result of closer European integration from the mid-1980s. This process initiated divides between those who sought closer integration in a federal Europe and those who sought to preserve the autonomy of nation-states within the European Union (EU). Similar debates took place within the EU’s member states. Largely in response to pressures from below, Italy, Spain and the UK introduced novel institutions of regional self-government during the 1970s whilst the conflict around Flemish identity and language led to the federalization of Belgium in 1993. As the journal reaches its thirtieth anniversary, the resilience of Euro-scepticism exemplified by the Brexit process, and lively separatist agendas in Catalonia and Scotland demonstrate the continued significance of these tensions at the heart of the EU and its member states (Keating Citation2021).

Beyond Western Europe, the collapse of the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia – as articles in early issues of RFS explored – raised questions about the sustainability of federalism as a mode of governance in multi-ethnic settings (Hill Citation1993; Kirschbaum Citation1993). Yet while pessimistic arguments about federalism in multi-ethnic settings drawing on these cases of failed federalism took shape (Bunce Citation2004; Roeder Citation2009), new experiments with federalism emerged as part of post-conflict settlements and transitions to democracy in countries ranging from Bosnia and Herzegovina to Iraq in the 1990s and 2000s. As many as seven new federal systems have been created since the 1990s in which accommodation of diversity/conflict management has been a goal (Belgium (1993); Russia (1993); Bosnia and Herzegovina (1995); Ethiopia (1995); South Africa (1996); Iraq (2005); Nepal (2015)). In other post-conflict settlements, new experiments with decentralization and autonomy arrangements generated a wide literature on power-sharing in multi-ethnic societies.

These newer experiments with federalism also pushed political scientists to revisit established theories and concepts grounded in the experience of Europe and North America. Stepan (Citation1999) coined the phrase ‘holding together’ to describe many of the world’s newer federal systems which were created by the devolution of power in settings of territorialized ethnic diversity, rather than the pooling of sovereignty. The resulting forms of federalism often looked very different too. The forms of federalism adopted in parts of Africa (Ethiopia, Nigeria, and South Africa, see Dickovick Citation2014) and India (Khosla Citation2020; Tillin Citation2021) were heavily centralized. They often had weaker second chambers than ‘coming together’ federal systems (Stepan Citation1999) and party system dynamics played a larger role in determining intergovernmental relations than formal institutions of intergovernmental relations (Fiseha Citation2012; Rohrbach Citation2020). These dynamics have also been observed in Western Europe, as instances of holding together federalism have also developed in Spain, Belgium, or the UK.

In Latin America, democratization reinvigorated federal institutions in large countries such as Argentina, Brazil and Mexico. Moreover, decentralization created and strengthened regional tiers in countries that had previously been characterized by a commitment to centralism (Niedzwiecki et al. Citation2021; Slater Citation1991). While decentralization created new institutions at the subnational level, it also rendered subnational variation in the functioning and performance of supposedly nationwide institutions more visible. Scholars of Latin America quickly identified subnational variation in democracy, and the persistence of subnational authoritarian regimes as an important concern and put this topic on the research agenda of those interested in territorial politics (Gibson Citation2005; Giraudy Citation2013).

Simultaneously two other processes helped to shift the scales and complexity of multi-level governance. Firstly, exercises in decentralization to subnational governments took shape in ways which altered territorial politics in large parts of the world. Secondly, supranational governance structures were strengthened and expanded in some places, such as Europe.

From the late 1970s through to the early 2000s, waves of decentralization reforms took place across parts of Asia, Africa, Latin America, and Central and Eastern Europe (Erk Citation2014; Hooghe et al. Citation2016; Saarts Citation2020). These reforms which saw the transfer of power, resources or responsibilities from central authorities to local governments were adopted in federal and unitary systems alike, driven by narratives of good governance, accountability, and development. In practice, the magnitude of shifts in power and resources varied considerably (Falleti Citation2005; Niedzwiecki et al. Citation2021). The outcomes of decentralization also differed. In some places, such as Brazil, political and fiscal decentralization to a third tier strengthened the authority of central governments by enabling them to divert resources from the meso level to the local level, ‘bypassing’ governors (Dickovick Citation2006; Fenwick Citation2016). In other places, decentralization involved the transfer of new responsibilities to local governments without authority or resources (Gomes Citation2012).

Just as decentralization swept parts of the globe in the past decades, a comparable process has been at play at the supranational level. Undoubtedly, the European integration process has been uneven and contested. Nevertheless, it is unparalleled. A supranational political system with its own enforceable legal order has emerged, taking precedence over existing national and subnational scales. EU norms and laws have primacy and direct effect over the legal orders beneath them. The EU certainly has ‘soft power’, but it is not short of ‘hard power’ either. Similar phenomena have taken place outside of the European continent though without reaching the level of integration achieved by the EU. Examples include the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the African Union (OAU/AU), the Common Market of the South (MERCOSUR), or the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), among others. These processes have been fragmented and narrower. Nonetheless, the main international organizations populating the globe have consolidated and expanded over time. Indeed, looking at the world’s 76 main international organizations, the past decades reveal clear increases in the extent to which states both pool and delegate their authority supranationally (Hooghe et al. Citation2017, 119).

These changes in the scale of territorial politics, the distribution of regional and supranational authority, and experiments in new political institutions – many of which were centred in the Global South away from the traditional heartlands of federalism scholarship – pushed the discipline of political science to shift its gaze anew towards the subnational level. As central governments began to open up and disperse their powers, Snyder (Citation2001) captured the spirit of the age in an article entitled ‘Scaling Down: The Subnational Comparative Method’. This in turn encouraged the analysis of subnational variation in phenomena such as the quality of democracy, strength of welfare provision, or levels of clientelism. These triggered new questions that challenged the national level bias implicit in the coding of democracies, public authority, service provision and delivery, and more generally the territorialization of policies and politics (Giraudy, Moncada, and Snyder Citation2019; Giraudy and Pribble Citation2019). As mainstream political science went through a quantitative and comparative turn, territorial politics scholars utilized a plurality of approaches to bring novel insights into existing discussions, and to challenge mono-scale, state-centric paradigms.

The comparative and quantitative turn

Over the 30 years of RFS’ existence, the sub-field has witnessed a comparative and quantitative turn, albeit one that has taken shape later than in the wider discipline of political science (Box-Steffensmeier, Brady, and Collier Citation2008, 4, 7). There are two reasons that scholars working on questions related to territorial politics have been slower to adopt comparative and/or quantitative approaches. The first has to do with the inherent tension between the essence of territorial politics (that context and territory matter) and the 1960s expression of behaviouralism in political science (which sought to emancipate itself from territorial contexts). The second has to do with the dearth of available and reliable data at the subnational level (and the accompanying hegemony of methodological nationalism).

Context and territory vs. the 1960s behavioural revolution

The behavioural revolution played a key role in mainstreaming quantitative analysis in political science research. However the advance of statistical methods was a mixed blessing. As King highlights, ‘while the behavioralists played an important role expanding the scope of quantitative analysis, they also contributed to the view that quantitative methods gave short shrift to political context’ (King Citation1990, 4). Specifically, the behaviouralist revolution sought universal explanations disenfranchized from territorial contexts. It led to research agendas which famously claimed that

explanation in comparative research is possible if and only if particular social systems observed in time and space are not viewed as finite conjunctions of constituent elements, but rather as residual of theoretical variables. (…) Only if the classes of social events are viewed as generalizable beyond the limits of any particular historical social system can general law-like sentences be used for explanation. Therefore the role of comparative research in the process of theory-building and theory-testing consists of replacing proper names of social systems by the relevant variables (Przeworski and Teune Citation1970, 30, emphasis added).

This idea has since been fully embraced by quantitative political methodologists triggering a flourish of insights on different tools and strategies available to model heterogeneity and dependencies. This is, for example, illustrated by the now common use of random-slope models (the idea that a given variable may have contrasting effects according to context), of two- or three-way interaction effects (the idea that the effect of X on Y may be conditional on values of Z and W), or of spatial models (the idea that there might be common exposure or diffusion and interaction across spatial units). Many of the more exciting developments in political methodology of the last 30 years are explicitly addressing issues of context dependencies and effect heterogeneities. They take to heart the idea ‘that the latent heterogeneity of covariate effects within each context (…) can vary from context to context (…) due to context-level features’ themselves (Ferrari Citation2020, 21, 40). In this sense, today’s political methodology is not only compatible with the core of territorial politics, but actually driving to better investigate and understand the essence of territorial politics itself: that territory and context matter in different yet meaningful ways and that these may interact in multi-scale processes which are both spatial and temporal.

The streetlight effect – Methodological nationalism

The second reason why the field of territorial politics was rather late in its embrace of the quantitative and comparative turn can be summarized under the label of ‘methodological nationalism’ (Jeffery and Wincott Citation2010). This is the idea that the nation-state is the natural or default unit of analysis. This led to two shortcomings. First, it meant that theories rarely escaped the normative hegemony of the nation-state as a theoretical reference and empirical starting point for analysis. Second, it meant that data was frequently unavailable beyond or below the nation-state level. In this way, territorial politics remained below the theoretical and empirical radar of many mainstream political scientists. And with little comparative or quantitative data readily or reliably available, territorial politics scholars in turn had few incentives to engage in the onerous process of collecting data themselves at a scale where systematized information was difficult to come by.

This methodological nationalism resulted in a ‘streetlight effect’ or ‘drunkard’s search bias’. Just as the midnight drunkard is looking for his lost keys under the streetlight because that is the only place where he can see, scholars have focused their investigations on questions where data is available. Naturally, territorial politics scholars, working on issues where data is scarce, unreliable, or invalid, had few incentives to embrace a quantitative or comparative turn which was ill-suited to their research field.

Better methods and better data – Embracing the turn and moving beyond it

As quantitative methodologies improved and as political scientists increasingly engaged in the collection of original data (King Citation1990, 5), territorial politics embraced the quantitative and comparative turn too. Clearly, the task was rather herculean on both fronts. The collection of reliable and valid comparative data is always challenging. But it is more so at the subnational level where sources are often more difficult to track down and where there can be a general dearth of information in the public domain to build upon. Similarly, quantitative analysis can be additionally tricky at the subnational level due to heterogeneities and interdependencies (both horizontal and vertical) which need to be explicitly modelled.

However, territorial politics has risen to the challenge in finding ways to respond to difficult data and methods questions. Its answers have been original and creative, triggering theoretical, conceptual, measurement, and methodological advances. In a way, territorial politics scholars are injecting freshness and novelty to existing discussions in several traditional fields of study. For example, in voting behaviour and election studies, scholars increasingly realize that electoral arenas at the local, regional, national, and supranational levels cannot be considered as independent and analysed separately, but instead interact through various spill-over and feedback effects. There is no such thing as independent electoral arenas (Dinas and Foos Citation2017; Schakel Citation2018; Spoon and Jones West Citation2015). The same goes for questions of representation and responsiveness, where scholars now observe how federal and multi-level dynamics alter flows of accountability. Responsiveness at one territorial scale is meaningfully affected by dynamics and arrangements at scales beneath it. Responsiveness too has become a multi-level affair with territorialized ingredients (Peters, Citationforthcoming; Wratil Citation2019). Similarly, decentralization is not only the fruit of domestic politics, but is significantly affected by developments at the supranational level such as European integration or globalization itself (Chacha Citation2020; Jurado and León Citation2020). At the same time, subnational politics feeds back into international politics, with tangible impacts on supranationalization and globalization processes themselves, as illustrated by the influence of subnational regions on European integration or on international trade deals (Broschek and Goff Citation2020; Tatham Citation2018). Having been part of traditional explanations of state building and state formation, and of how incomplete or contested these processes were (Lipset and Rokkan Citation1967; Rokkan and Urwin Citation1983), it is no exaggeration to argue that territory is making a comeback, territorializing mainstream political science in the process.

These examples highlight how territorial politics has added new dimensions and meaningful insights to traditional fields of research such as those focusing on electoral dynamics, policy responsiveness, institutional reform processes, or transnational and international politics. In this way, territorial politics has not only embraced the quantitative and comparative turn, it has also brought new insights into older discussions, whilst relying on the full palette of social science approaches and methods, from the more qualitative to the more quantitative, from the more case-centric to the more comparative.

Territorializing mainstream political science

Advances in conceptualization and measurement have been at the root of the territorialization of political science. Without appropriate concepts and valid measures, scholars were incapable of including the relevant territorial ingredients in their analyses. For example, the conceptualization and measurement of federalism and decentralization stagnated for decades around crude and invalid indicators. Federalism was often defined as a dummy variable (federal states = 1, the rest = 0) following literal readings of national constitutions. Meanwhile, decentralization was measured through cash flows, operationalized as subnational expenditures or revenues. Both approaches had problems of their own. The federal dummy was too crude. It clustered centralized unitary countries together with their decentralized peers as if these were alike, whilst overlooking temporal variation introduced by institutional changes falling short of full federalism. The revenue and expenditure measures were reliable, but invalid, as they measured cashflows but said little about authority. As scholars moved away from federal dummies and cashflow measures, they encountered other challenges, such as the theoretical and empirical validity of their constructs or the fact that their measures were still too crude to capture more incremental changes among both unitary and federal states (Hooghe and Marks Citation2013). Meanwhile, most of these measures overlooked significant variation in asymmetrical systems (such as the UK, Finland, Portugal, Spain, or Italy) for which country-level measures provide an inaccurate indicator (Marks, Hooghe, and Schakel Citation2008a).

The Regional Authority Index (RAI) (Marks, Hooghe, and Schakel Citation2008a, Citation2008b) represented a major advance in measurement. This index provided a multi-dimensional quantification of regional authority, measured directly at the regional level (i.e. using regions at the unit of analysis) and highlighting differences of degrees between systems in the form of ordinal, quasi-continuous scales. The RAI was not created overnight. One of its first published expressions can already be found in a 1996 article (Marks et al. Citation1996). After its launch in RFS in 2008 (Marks, Hooghe, and Schakel Citation2008a, Citation2008b), the RAI was updated in 2010. It was developed further in a 2016 publication, with significant spatial and territorial expansions (i.e. more region-country-years) as well as some theoretical and empirical adjustments (e.g. the addition of ‘borrowing autonomy’ and ‘borrowing control’) (Hooghe et al. Citation2016). The index is currently being updated and expanded again to include a wider range of countries.Footnote2 It has played a critical role in reinvigorating studies of multi-level governance and has contributed to the territorialization of mainstream political science.

Although prominent and distinctive, the RAI is not alone. It is part of a wider movement which has sought to better conceptualize and measure critical aspects of territorial politics. Inspired by the RAI or simply coincidental to it, a host of other indicators have sought to capture territorial institutions. These include measurements of territorial self-governance (Trinn and Schulte Citation2020) and state structures (Dardanelli Citation2018). But they also include broader questions of subnational democracy (Giraudy Citation2015; Harbers, Bartman, and van Wingerden Citation2019; Harbers and Ingram Citation2014), of regional quality of government (Charron and Lapuente Citation2013), or of local/municipal authority (Ladner, Keuffer, and Baldersheim Citation2016). Researchers are also developing subnational datasets and indicators within specific policy domains such as climate competence (Bromley-Trujillo and Holman Citation2020), EU affairs (Tatham Citation2011), welfare (Giraudy and Pribble Citation2019) or immigration (Zuber Citation2020). In the same vein, a comparable effort is observed when it comes to coding or quantifying different aspects of territorial actors, such as various types of parties (Zuber and Szöcsik Citation2019) or of interest groups (López and Tatham Citation2018). In sum, scholars are getting a better understanding of institutions and actors evolving at the territorial level and are feeding these insights back into mainstream political science enquiries.

The development of regional and federal studies: Topics, cases and authors

To what extent has the content of RFS reflected these broader substantive and methodological trends? To answer this question, we took the 30th anniversary as an occasion to take a step back and assess how the journal has developed over the past three decades in terms of substantive topics, geographical coverage of cases, methods used, and in terms of the diversity of perspectives RFS authors have brought to bear on questions of regional and federal studies.

To this aim, we compiled a database of all articles published in the journal from its inception until the present day (1991–2020).Footnote3 Substantive topics were coded according to key words, except for early volumes that did not yet have key words and where we derived key words from the article heading and introduction instead. To assess geographical coverage, we coded cases analysed in each article based on seven world regions: Western Europe, Eastern Europe, North America, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, Middle East / North Africa and Sub Saharan Africa, and Australia. For methods, we differentiated conceptual articles, qualitative single case studies, qualitative comparative case studies and articles employing quantitative methods. Finally, we coded authors’ gender and in which world region they had their institutional affiliation at the time an article was published. The complete database contains entries for a total of 789 research articles and regional election reports, while excluding the category of book reviews.

To explore the topics covered on the journal’s pages, we created a word cloud in which the size of a word indicates how many times the term appears in the keywords. shows that RFS content clearly reflects the journal’s original vision of covering regionalism, as well as the expansion of its scope during the 1996 re-launch to federalism (cf. Loughlin Citation2021). Both ‘regional’ and ‘federalism’ appear prominently at the centre of the word cloud. The fact that concepts such as multi-level governance, Europeanisation and intergovernmental cooperation and conflict also figure prominently among the key words shows RFS content is not limited to what happens inside subnational and supranational institutions, but also covers how political actors interact across territorial scales. The recognition that multiple levels of analysis are crucial for understanding outcomes of interest has played an important role in the scholarship RFS has published over the years. The prominence of identity and nationalism among the keywords shows that such interactions are not limited to questions of efficient governance, but often concern questions of community and the perennial challenge of how to guarantee unity while accommodating diversity.

In terms of geographic scope, the cloud includes traditional federal countries like Canada and Germany and the federal newcomer of Belgium. It also illustrates the journal’s commitment to documenting and analysing territorial reforms in countries like Spain, Italy and the UK that introduced regional self-rule but stopped short of full-fledged federalization. Further, the journal devoted considerable attention to the strengthening of regional tiers in unitary countries, such as France and Ireland, in which such tiers gained importance but remained comparatively weak. The supranational European dimension in all of these processes is very prominent across time.

The frequent use of the keyword ‘elections’ reflects the fact that RFS has always published regional election reports, even at a time when such elections were still regarded as ‘second order’ events (Schakel and Romanova Citation2018, 239). The first of these reports already appeared in the journal’s very first volume in 1991 (Moxon-Browne Citation1991). At a time when systematic data about subnational political phenomena was scarce, these reports provided an important resource for scholars of elections and party politics. The documentation and analysis of regional electoral processes continues to be a core component of the journal’s mission (Schakel and Romanova Citation2018). This was institutionalized further in 2018 when these reports were given a regular home in the Annual Review of Regional Elections (ARoRE), edited by Valentyna Romanova and Arjan Schakel. The ARoRE also illustrates the journal’s increasingly global scope. The most recent edition of the annual review includes research articles on Southeastern Europe (Bosnia and Herzegovina), Africa (Kenya, Nigeria), Latin America (Brazil) and North America (USA), as well as reports on elections in Western Europe (Denmark, Sweden), Eastern Europe (Poland), and Asia (South Korea). This is particularly important since these reports provide accessible data on regional elections and have allowed scholars of elections to pursue comparisons across world regions.

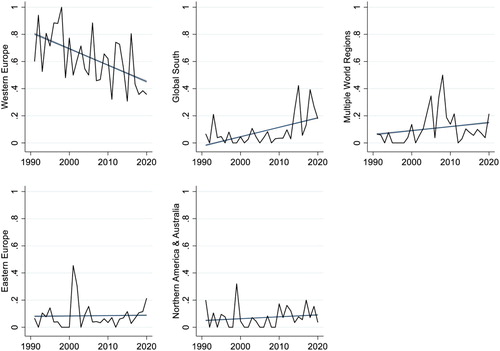

The shift from a strong focus on European cases to a broader territorial scope is also evident in regular issues. During its first decade, RFS’ core business was clearly to bring research on federations in Europe, North America and Australia into dialogue with novel phenomena of regionalization that resulted from territorial reforms within European nation states and the deepening of European supranational governance. While European and North American cases continue to feature prominently on the journal’s pages, coverage has broadened substantially in recent years. During the 1990s seventy-nine percent of regular articles covered cases from Western Europe. Coverage of classical federations in North America and Australia accounted for a further nine percent of empirical articles.Footnote4 Since the 2000s, and in line with improved concepts and data in the field of territorial politics and multi-level governance, RFS authors have begun to broaden their geographical scope. Articles covering cases beyond the traditional focus on Western Europe, North America and Australia make up a quarter of all articles (24%) after 2000. The increase in comparative articles covering multiple world regions from three percent during RFS’ first decade to sixteen percent in the last two decades is also noteworthy. Some of these patterns are illustrated in .

Figure 2. Geographical coverage of cases in RFS articles, 1990–2020.

Notes: y-axis = proportion of articles per volume. Global South = Asia, Latin America, the Caribbean, the Middle East, and Africa.

The journal’s commitment to stimulating exchange between scholars focusing on different world regions is particularly evident with regard to special issues, which have played a vanguard role in broadening RFS’ geographical scope. From the very beginning, guest editors of special issues have often made deliberate efforts to cover a substantive topic across a diverse set of cases. An early example of this is a special issue on the territorial accommodation of ethnic conflict published in 1993 (Coakley Citation1993). Non-European cases were included with the specific goal of informing the debate on how to craft solutions for territorial conflicts associated with the rise of ethno-regionalist parties in many European countries. The emergence (or rather re-emergence) of centre-periphery conflicts in Western Europe inspired scholars to look beyond their usual frame of comparison.

During the last ten years, RFS has published special issues dedicated entirely to comparisons of countries from the Global South, and also to comparisons across world regions. Fostering and stimulating submissions on world regions that are underrepresented on the journal’s pages is now part of a conscious editorial strategy to increase the journal’s global profile. This has led to special issues covering Sub-Saharan Africa (Volume 24, Issue 5; Volume 25, Issue 5) as well as India and Latin America (Volume 29, Issue 2). A thematic special issue dedicated to cross-border cooperation (Volume 27, Issue 3) covered the case of Kashmir (Mahapatra Citation2017), while a special issue on multi-level political careers (Volume 21, Issue 2) included Brazil (Santos and Pegurier Citation2011). Within Europe, special issues have expanded the range of cases beyond the ‘usual suspects’ in debates on territorial reforms, for instance by focusing on small unitary countries (Volume 30, Issue 2).

Over time, RFS authors have also become increasingly ready to engage in comparisons of territorial politics across different world regions. As indicated above, articles including empirical material from multiple world regions make up about sixteen percent of the articles during the last two decades. Two excellent examples of this approach are André Lecours’ and Erika Arban’s (Citation2015) analysis of how politicians’ fears of further disintegration hampered federalization in Italy and Nepal, as well as Daniel Cetrà’s and Wilfried Swenden’s (Citation2021) comparison of the influence of mainstream party ideology on territorial models in India and Spain. RFS hopes to continue publishing this type of innovative comparative research in the future.

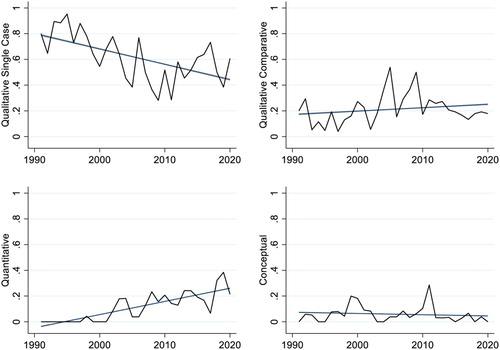

In terms of methodology, works published in RFS have been following the general development of the sub-field described in the previous section. During the 1990s issues were filled almost exclusively with single case studies that offered thick descriptions of processes of territorial reform, policy-making across levels of government, supranational integration or intergovernmental relations. These articles often described new phenomena that had not yet been fully theorized or systematized. For example, we see early descriptions of sub-state regions engaging in foreign policy (Morrow Citation1992), without yet disposing of the concept of ‘paradiplomacy’ – while by 1999 paradiplomacy was already the main theme of a comparative RFS special issue (1999, Volume 9, Issue 1).

The 2000s increased the share of comparative and quantitative contributions considerably. The share of qualitative comparative case studies rose from 14% in the 1990s to 24.5% after the year 2000. The share of articles using quantitative methods has risen from being barely existent during the 1990s (0.46%) to an average share of 16.7% of articles for the twenty years after 2000. The last decade in particular shows that this trend is still on the rise, with a share of 20.7% of articles published between 2011 and 2020 applying quantitative methods. Given the lack of standardized meso and macro data (see sections above), many of these quantitative articles work with survey data to assess regional variance in citizens’ political preferences, territorial identities, or support for territorial reform (e.g. Bond and Rosie Citation2010). Authors have also moved towards a more systematic and explicit justification of their chosen methods in single and comparative case studies over time, which reflects the increasing standardization of qualitative methods in the discipline (Rohlfing Citation2012). Some of these patterns are illustrated in .

Figure 3. Methods used in RFS articles, 1990–2020.

Notes: y-axis = proportion of articles per volume.

Despite the rise of comparative and quantitative work, the typical RFS contribution is still one that provides in-depth case knowledge. However, many of the studies categorized as ‘single case’, cover complex dynamics of multi-level governance that, though taking place within the boundaries of a single political system, involve interactions between multiple actors at multiple levels of government (e.g. Colino, Molina, and Hombrado Citation2014). The continued focus on in-depth case knowledge is also in line with another constant over time: the publication of conceptual and theoretical articles. These articles pick up on new phenomena at the sub- and supranational level and engage in the conceptual and classificatory groundwork that lays the basis for future comparative and quantitative studies that require clear-cut concept specification (e.g. Hepburn Citation2009; Marks Citation1996). A stable share of 15–16% of articles in all three decades is of a conceptual/theoretical nature. As RFS increasingly covers empirical ground across different world regions, authors are often working on phenomena that do not fit comfortably under concepts developed on European and North American cases (Erk Citation2021). A healthy share of conceptual pieces will thus be needed also in the future.

In a final step, we also analysed the characteristics of authors who published their work in the journal. Particularly in the early years, RFS mirrors a broader trend of predominantly male authorship in political science journals. During the 1990s, 82% of articles were exclusively written by male authors (counting both single and co-authored pieces). Further, RFS’ first team of editors as well as its first editorial advisory board were exclusively male. Authors also tended to be based at a limited number of European and North American institutions with research programmes focused on regionalism and federalism. The contribution by John Loughlin (Citation2021), the journal’s founding editor, to this anniversary issue highlights how important personal networks were in the journal’s early years for soliciting submissions.

As the journal matured, it attracted submissions from a broader range of authors. The share of all-male articles, for instance, drops to 60% during the 2000s. While this still indicates a strong gender imbalance, we need to put these numbers into context by comparing them to authorship patterns in the field, and especially in prominent political science journals. Comparable data are available for the period from 2000 to 2015. RFS’ average share of women authors between 2000 and 2015 was 29.3%. This places RFS above the major American generalist journals (AJPS, 18.02%; APSR 23.43%) and slightly below the two major American comparative journals (Comparative Politics 31.46%; Comparative Political Studies 32.17%, figures taken from Teele and Thelen Citation2017, 435).

One noteworthy finding of our review of RFS content is that special issues appear to have played an important role in broadening the pool of authors who submit their work to the journal. Starting in the first decade of the journal’s existence, special issues tended to be more gender balanced than regular issues, while also including authors from a broader range of institutions. One possible reason for this is that thematic special issues were often designed to offer empirical accounts of a novel phenomenon for a range of country cases. Guest editors then approached scholars based in countries of interest to invite them to participate in the special issue, and to share their empirical expertize.

The current team of editors is majority female and the current advisory board has a balanced gender distribution. Current members of the advisory board contribute diverse geographic and thematic expertize and come from almost all world regions. This diversity is unfortunately not reflected in the institutional affiliations of RFS’ authors who are still predominantly based in Europe and North America. This again is not specific to RFS but reflects a broader pattern in social science publishing. Given RFS’ commitment to publishing qualitative case studies on underrepresented regions that require in-depth contextual knowledge, attracting submissions from authors based in Africa, Asia and Latin America is of high importance for the further development of the journal.

Overview of the anniversary issue contributions

The contributors to this anniversary issue are among the people who have been defining the field of regional and federal studies during the past 30 years, many of whom have also contributed to the development of the journal. A total of eight articles provide compelling empirical insights from multi-level political systems across the world, while also engaging in important meta-theoretical reflections that help define the agenda of the field and the journal for the years to come.

The Anniversary Issue opens with two pieces that continue the discussion of the genealogy of the field and its core concepts. John Loughlin (Citation2021) reflects on the origins of the journal and its specific goal of covering issues of regionalism beyond minority nationalism and ethnic conflict that were more topical during the early 1990s. Michael Keating (Citation2021) adds a meta-theoretical discussion about the meaning of the field’s core concepts. His contribution acts as a warning against teleological temptations and the pitfall of overlooking the changing co-dependencies of concepts such as territory, functionality, and identity. Just as these concepts should not be reified, their constructed nature and their instrumentalization as mobilizing and legitimizing frames should also not be overlooked. Although functionality and identity matter, the arbitration between them ends up being a political affair and thereby both contested and evolving.

The third contribution by Jan Erk (Citation2021) continues this methodological discussion. To avoid insensitivity to context but also an overly narrow focus on individual cases, he suggests a holistic approach to the study of regionalism and federalism that is inspired by scientific realism. This invites researchers to approach their research questions from a broader historical, geographical and more multi-disciplinary perspective than is most often the case. Illustrating this approach with a study of constitution-making in historical and contemporary Sub-Saharan African cases, he shows how an iterative analysis can combine awareness to broader comparative patterns and globally entangled politics with context-sensitive case evidence to find an answer to the question of how to design robust federal constitutions.

The remaining five contributions are empirical in nature. They address two perennial questions that lie at the heart of the field and of the journal: How good are multi-level political systems at being gentler (in terms of accommodating the needs of culturally distinct minority communities) and kinder (in terms of providing welfare for their citizens)?

Sarah Shair-Rosenfield and her co-authors (2021) trace the societal origins of regional authority, and even the origins of regional communities themselves. They argue that the interaction between languages affects the development of regional differences in language (i.e. regionally distinct minority communities) and that these regionally based linguistic differences subsequently translate into regional authority. This macro-structural argument harks back to a very early RFS article by Laponce (Citation1993) who analysed the geographical dimension of language preservation based on the case of Quebec. Thirty years later, Shair-Rosenfield et al. bring systematic global data to bear on a similar question.

Alain-G. Gagnon (Citation2021) provides a comprehensive review of democratic multinational federations across time and across the world. He reiterates the important role of multinational federalism in conflict management because of its capacity to institutionalize ‘a politics of recognition’. However, he identifies a trend of re-nationalization since the 1990s that works against the goal of decoupling state and nation inherent to the concept of multinational federalism. This re-nationalization is pushed as much by secessionist-minded minority nationalists as by majority nationalist parties who aspire to a mono-national definition of the state. He sees this as aggravated by a trend towards federal symmetry at odds with the special status demands of minority regions in multinational states.

Daniel Cetrà and Wilfried Swenden (Citation2021) zoom in on the role of state-wide parties of government in defining states as multi- versus mono-national. They attribute a crucial role to the type of state-nationalist ideology of parties in central government during critical junctures of constitution-making and territorial crises. In an innovative comparison of India and Spain, they show how party politics in both countries have transformed original constitutional compromises that worked in favour of a rather integrationist model towards dominant Hindu nationalism in India, and towards a polarization between different models in Spain ranging from plurinational to dominant Spanish nationalism. All three articles on questions of territorial autonomy and community are excellent examples of how insightful comparisons across world regions can be, whether they are qualitative as in Cetrà and Swenden (Citation2021) and Gagnon (Citation2021), or quantitative as in Shair-Rosenfield et al. (Citation2021).

The final two contributions move the perspective away from questions of community and identity towards questions of state capacity, welfare and political economy. Both Danielle Resnick (Citation2021) and Melissa Rogers (Citation2021) investigate how sharing authority across levels of government affects state performance. They emphasize the limits of classical theories of decentralization that promise efficiency gains through inter-regional competition. In studying cases from the Global South, they reiterate the point that context matters, since Western-based economic theories of federalism and decentralization do not travel well to Latin American and African contexts. In contrast the multi-level governance heuristic turns out to be more flexible.

Danielle Resnick (Citation2021) analyses the logic of metropolitan governance in Sub-Saharan Africa. She shows that traditional authorities and international donors need to be taken into account when analysing service delivery on the part of subnational governments. Her contribution also demonstrates that while regionalization may have played an important role in shifting the scales of governance in Western Europe during the 1990s, from a contemporary global perspective urbanization is now a much more important rescaling process in which ‘cities are becoming major sites of power and progress’. Her mapping of the competencies of cities in Sub-Saharan Africa also shows that we are dealing once again with a rather novel phenomenon that first requires classification to enable subsequent comparative research designs.

Last but not least, Melissa Rogers’ piece (2021) on federalism and the welfare state in Latin America provides an important note of caution against optimistic theories that see federalism as a motor for reducing inter-regional inequality. She shows how much to the contrary, federalism in Latin America has been deepening inequalities as it has impeded effective central government action aimed at reducing inequality and increasing welfare. Inter-regional redistribution in fact makes the poor worse off in both rich and poor states. This is the result of political bargaining and coalition building that politicizes inter-regional transfers.

The contributions on Africa, Latin America and South Asia in this anniversary issue highlight the commitment of RFS to encouraging further research on these regions. Understanding the dynamics of subnational governance outside Europe and North America requires sharpening the scope conditions of existing concepts and theories and building new theories to account for novel phenomena, such as the rise of urban governance in mega-cities. This will be an important goal for RFS during its next thirty years for which it comes well equipped. The journal’s strong tradition of publishing conceptual/theoretical contributions with in-depth case studies, alongside quantitative large-N studies based on ever improving datasets on territorial phenomena, signals its ongoing commitment to methodological pluralism in order to understand and explain changing patterns of territorial politics and multi-level governance. The four authors of this introduction and current editors of the journal are committed to working towards these goals for the next years to come.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 See https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?show=aimsScope&journalCode=frfs20 [last accessed 04.12.2020].

2 See http://garymarks.web.unc.edu/data/regional-authority/ [last accessed 15.12.2020].

3 We gratefully acknowledge research assistance by Stefan Kebekus.

4 The predominant coverage of North American and Western European cases falls in line with the general pattern in political science, as shown in Wilson and Knutsen’s (Citation2020) analysis of the major generalist, comparativist and IR journals between 1906 and 2019.

References

- Bond, R., and M. Rosie. 2010. “National Identities and Attitudes to Constitutional Change in Post-Devolution UK: A Four Territories Comparison.” Regional & Federal Studies 20 (1): 83–105.

- Box-Steffensmeier, J. M., H. E. Brady, and D. Collier. 2008. “Political Science Methodology.” In The Oxford Handbook of Political Methodology, edited by M. Box-Steffensmeier J, E. Brady H., and D. Collier, 3–34. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bromley-Trujillo, R., and M. R. Holman. 2020. “Climate Change Policymaking in the States: A View at 2020.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 50 (3): 446–472.

- Broschek, J., and P. Goff. 2020. The Multi-Level Politics of Trade. Toronto, CA: University of Toronto Press.

- Bunce, V. 2004. “Federalism, Nationalism and Secession: The Communist and Postcommunist Experience.” In Federalism and Territorial Cleavages, edited by U. M. Amoretti and N. G. Bermeo, 417–440. Baltimore: JHU Press.

- Cetrà, D., and W. Swenden. 2021. “State Nationalism and Territorial Accommodation in Spain and India.” Regional & Federal Studies 31 (1): 115–137. doi:10.1080/13597566.2020.1834387.

- Chacha, M. 2020. “European Union Membership Status and Decentralization: A top-Down Approach.” Regional & Federal Studies 30 (1): 1–23.

- Charron, N., and V. Lapuente. 2013. “Why do Some Regions in Europe Have Higher Quality of Government?” Journal of Politics 75 (03): 567–582.

- Coakley, J. 1993. “Introduction: The Territorial Management of Ethnic Conflict.” Regional Politics and Policy 3 (1): 1–22.

- Colino, C., I. Molina, and A. Hombrado. 2014. “Responding to the New Europe and the Crisis: The Adaptation of Sub-National Governments’ Strategies and its Effects on Inter-Governmental Relations in Spain.” Regional & Federal Studies 24 (3): 281–299.

- Dardanelli, P. 2018. “Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Mapping State Structures—with an Application to Western Europe, 1950–2015.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 49 (2): 271–298.

- Dickovick, J. T. 2006. “Municipalization as Central Government Strategy: Central-Regional–Local Politics in Peru, Brazil, and South Africa.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 37 (1): 1–25.

- Dickovick, J. T. 2014. “Federalism in Africa: Origins, Operation and (In)Significance.” Regional & Federal Studies 24 (5): 553–570.

- Dinas, E., and F. Foos. 2017. “The National Effects of Subnational Representation: Access to Regional Parliaments and National Electoral Performance.” Quarterly Journal of Political Science 12 (1): 1–35.

- Editorial statement. 1995. “Editorial Statement.” Regional & Federal Studies 5 (1): 7–9.

- Erk, J. 2014. “Federalism and Decentralization in Sub-Saharan Africa: Five Patterns of Evolution.” Regional & Federal Studies 24 (5): 535–552.

- Erk, J. 2021. “A Better Scholarly Future Rests on Reuniting the West with the Rest, the Present with the Past, the Theory with Practice.” Regional & Federal Studies 31 (1): 51–72. doi:10.1080/13597566.2020.1830376.

- Falleti, T. G. 2005. “A Sequential Theory of Decentralization: Latin American Cases in Comparative Perspective.” American Political Science Review 99 (3): 327–346.

- Fenwick, T. B. 2016. Avoiding Governors: Federalism, Democracy, and Poverty Alleviation in Brazil and Argentina. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

- Ferrari, D. 2020. “Modeling Context-Dependent Latent Effect Heterogeneity.” Political Analysis 28 (1): 20–46.

- Fiseha, A. 2012. “Ethiopia's Experiment in Accommodating Diversity: 20 Years’ Balance Sheet.” Regional & Federal Studies 22 (4): 435–473.

- Gagnon, A.-G. 2021. “Multinational Federalism: Challenges, Shortcomings and Promises.” Regional & Federal Studies 31 (1): 99–114. doi:10.1080/13597566.2020.1781097.

- Gibson, E. L. 2005. “Boundary Control: Subnational Authoritarianism in Democratic Countries.” World Politics 58 (1): 101–132.

- Giraudy, A. 2013. “Varieties of Subnational Undemocratic Regimes: Evidence from Argentina and Mexico.” Studies in Comparative International Development 48 (1): 51–80.

- Giraudy, A. 2015. Democrats and Autocrats. Pathways of Subnational Undemocratic Regime Continuity Within Democratic Countries. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Giraudy, A., E. Moncada, and R. Snyder. 2019. Inside Countries: Subnational Research in Comparative Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Giraudy, A., and J. Pribble. 2019. “Rethinking Measures of Democracy and Welfare State Universalism: Lessons from Subnational Research.” Regional & Federal Studies 29 (2): 135–163.

- Gomes, S. 2012. “Fiscal Powers to Subnational Governments: Reassessing the Concept of Fiscal Autonomy.” Regional & Federal Studies 22 (4): 387–406.

- Harbers, I., J. Bartman, and E. van Wingerden. 2019. “Conceptualizing and Measuring Subnational Democracy Across Indian States.” Democratization 26 (7): 1154–1175.

- Harbers, I., and M. C. Ingram. 2014. “Democratic Institutions Beyond the Nation State: Measuring Institutional Dissimilarity in Federal Countries.” Government and Opposition 49 (1): 24–46.

- Hepburn, E. 2009. “Introduction: Re-Conceptualizing Sub-State Mobilization.” Regional & Federal Studies 19 (4-5): 477–499.

- Hill, R. J. 1993. “The Soviet Union: From ‘Federation’ to ‘Commonwealth’.” Regional Politics and Policy 3 (1): 96–122.

- Hooghe, L., and G. Marks. 2013. “Beyond Federalism: Estimating and Explaining the Territorial Structure of Government.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 43 (2): 179–204.

- Hooghe, L., G. Marks, T. Lenz, J. Bezuijen, B. Ceka, and S. Derderyan. 2017. Measuring International Authority. A Postfunctionalist Theory of Governance, Volume III. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hooghe, L., G. Marks, A. H. Schakel, S. Chapman, S. Niedzwiecki, and S. Shair-Rosenfield. 2016. Measuring Regional Authority. A Postfunctionalist Theory of Governance, Volume I. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Jeffery, C., and D. Wincott. 2010. “The Challenge of Territorial Politics: Beyond Methodological Nationalism.” In New Directions in Political Science. Responding to the Challenges of an Interdependent World, edited by C. Hay, 167–188. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Jurado, I., and S. León. 2020. “Economic Globalization and Decentralization: A Centrifugal or Centripetal Relationship?” Governance. doi:10.1111/gove.12496.

- Keating, M. 1985. “The Rise and Decline of Micronationalism in Mainland France.” Political Studies 33 (1): 1–18.

- Keating, M. 2021. “Rescaling Europe, Rebounding Territory: A Political Approach.” Regional & Federal Studies 31: 1.

- Khosla, M. 2020. India’s Founding Moment: The Constitution of a Most Surprising Democracy. Cambridge, US: Harvard University Press.

- King, G. 1990. “On Political Methodology.” Political Analysis 2: 1–29.

- Kirschbaum, S. J. 1993. “Czechoslovakia: The Creation, Federalization and Dissolution of a Nation-State.” Regional Politics and Policy 3 (1): 69–95.

- Ladner, A., N. Keuffer, and H. Baldersheim. 2016. “Measuring Local Autonomy in 39 Countries (1990–2014).” Regional & Federal Studies 26 (3): 321–357.

- Laponce, J. A. 1993. “The Case for Ethnic Federalism in Multilingual Societies: Canada's Regional Imperative.” Regional Politics and Policy 3 (1): 23–43.

- Lecours, A., and E. Arban. 2015. “Why Federalism Does Not Always Take Shape: the Cases of Italy and Nepal.” Regional & Federal Studies 25 (2): 183–201.

- Lipset, S. M., and S. Rokkan. 1967. “Cleavage Structures, Party Systems and Voter Alignments.” In Party Systems and Voter Alignments, edited by M. Lipset S, and S. Rokkan, 1–64. New York: Free Press.

- López, F. A. S., and M. Tatham. 2018. “Regionalisation with Europeanisation? The Rescaling of Interest Groups in Multi-Level Systems.” Journal of European Public Policy 25 (5): 764–786.

- Loughlin, J. 2021. “Regions in Europe and Europe of the Regions. The Origins of Regional and Federal Studies.” Regional & Federal Studies 31 (1): 25–30. doi:10.1080/13597566.2019.1681405.

- Mahapatra, D. A. 2017. “States, Locals and Cross-Border Cooperation in Kashmir: Is Secondary Foreign Policy in Making in South Asia?” Regional & Federal Studies 27 (3): 341–358.

- Marks, G. 1996. “An Actor-Centred Approach to Multi-Level Governance.” Regional & Federal Studies 6 (2): 20–38.

- Marks, G., L. Hooghe, and A. Schakel. 2008a. “Measuring Regional Authority.” Regional & Federal Studies 18 (2): 111–121.

- Marks, G., L. Hooghe, and A. Schakel. 2008b. “Patterns of Regional Authority.” Regional & Federal Studies 18 (2): 167–181.

- Marks, G., F. Nielsen, L. Ray, and J. Salk. 1996. “Competencies, Cracks, and Conflicts: Regional Mobilization in the European Union.” Comparative Political Studies 29 (2): 164–192.

- Morrow, D. 1992. “Regional Policy as Foreign Policy: The Austrian Experience.” Regional Politics and Policy 2 (3): 27–44.

- Moxon-Browne, E. 1991. “Regionalism in Spain: The Basque Elections of 1990.” Regional Politics and Policy 1 (2): 191–196.

- Niedzwiecki, S., S. Chapman Osterkatz, L. Hooghe, and G. Marks. 2021. “The RAI Travels to Latin America: Measuring Regional Authority Under Regime Change.” Regional & Federal Studies. doi:10.1080/13597566.2018.1489248.

- Peters, Y. Forthcoming. “Social Policy Responsiveness in Multilevel Contexts: How Vertical Diffusion of Competences Affects the Opinion-Policy Link.” Governance.

- Przeworski, A., and H. Teune. 1970. The Logic of Comparative Social Inquiry. New York: University of Michigan: Wiley-Interscience.

- Resnick, D. 2021. “The Politics of Urban Governance in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Regional & Federal Studies 31 (1): 139–161. doi:10.1080/13597566.2020.1774371.

- Roeder, P. G. 2009. “Ethnofederalism and the Mismanagement of Conflicting Nationalisms.” Regional & Federal Studies 19 (2): 203–219.

- Rogers, M. 2021. “Federalism and the Welfare State in Latin America.” Regional & Federal Studies 31 (1): 163–184. doi:10.1080/13597566.2020.1749841.

- Rohlfing, I. 2012. Case Studies and Causal Inference: An Integrative Framework. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rohrbach, L. 2020. “Intra-party Dynamics and the Success of Federal Arrangements: Ethiopia in Comparative Perspective.” Regional & Federal Studies, 1–20. doi:10.1080/13597566.2020.1736569.

- Rokkan, S., and D. Urwin. 1983. Economy, Territory and Identity: Politics of West European Peripheries. London, UK: Sage.

- Saarts, T. 2020. “Introducing Regional Self-Governments in Central and Eastern Europe: Paths to Success and Failure.” Regional & Federal Studies 30 (5): 625–649.

- Santos, F. G. M., and F. J. H. Pegurier. 2011. “Political Careers in Brazil: Long-Term Trends and Cross-Sectional Variation.” Regional & Federal Studies 21 (2): 165–183.

- Schakel, A. H. 2018. “Rethinking European Elections: The Importance of Regional Spill-Over Into the European Electoral Arena.” Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (3): 687–705.

- Schakel, A. H., and V. Romanova. 2018. “Towards a Scholarship on Regional Elections.” Regional & Federal Studies 28 (3): 233–252.

- Shair-Rosenfield, S., A. H. Schakel, S. Niedzwiecki, G. Marks, L. Hooghe, and S. Chapman-Osterkatz. 2021. “Language Difference and Regional Authority.” Regional & Federal Studies 31 (1): 73–97. doi:10.1080/13597566.2020.1831476.

- Slater, D. 1991. “Towards the Regionalization of State Power: Peru, 1985–90.” Regional Politics and Policy 1 (3): 210–222.

- Snyder, R. 2001. “Scaling Down: The Subnational Comparative Method.” Studies in Comparative International Development 36 (1): 93–110.

- Spoon, J.-J., and K. Jones West. 2015. “Bottoms Up: How Subnational Elections Predict Parties’ Decisions to run in Presidential Elections in Europe and Latin America.” Research & Politics 2 (3): 1–8.

- Stepan, A. 1999. “Federalism and Democracy: Beyond the U.S. Model.” Journal of Democracy 10 (4): 19–34.

- Tatham, M. 2011. “Devolution and EU Policy-Shaping: Bridging the Gap Between Multi-Level Governance and Liberal Intergovernmentalism.” European Political Science Review 3 (1): 53–81.

- Tatham, M. 2018. “The Rise of Regional Influence in the EU – From Soft Policy Lobbying to Hard Vetoing.” Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (3): 672–686.

- Teele, D. L., and K. Thelen. 2017. “Gender in the Journals: Publication Patterns in Political Science.” PS: Political Science & Politics 50 (2): 433–447.

- Tillin, L. 2021. “ Building a National Economy: Origins of Centralized Federalism in India.” Publius, 1–25. doi:10.1093/publius/pjaa039.

- Trinn, C., and F. Schulte. 2020. “Untangling Territorial Self-Governance – New Typology and Data.” Regional & Federal Studies, 1–25. doi:10.1080/13597566.2020.1795837.

- Wilson, M. C., and C. H. Knutsen. 2020. “Geographical Coverage in Political Science Research.” Perspectives on Politics, 1–16. doi:10.1017/S1537592720002509.

- Wratil, C. 2019. “Territorial Representation and the Opinion–Policy Linkage: Evidence from the European Union.” American Journal of Political Science 63 (1): 197–211.

- Zuber, C. I. 2020. “Explaining the Immigrant Integration Laws of German, Italian and Spanish Regions: sub-State Nationalism and Multilevel Party Politics.” Regional Studies 54 (11): 1486–1497.

- Zuber, C. I., and E. Szöcsik. 2019. “The Second Edition of the EPAC Expert Survey on Ethnonationalism in Party Competition – Testing for Validity and Reliability.” Regional & Federal Studies 29 (1): 91–113.