ABSTRACT

Language has often been associated with the political culture of citizens and certain core values and expectations in multilingual federations. In times of crisis, the existence and extent of cultural characteristics are particularly relevant for multilingual societies, where cultural differences can fuel political conflict as much as similarities can bring people together. To answer whether and how language is associated with different political attitudes, this article analyses a cross-sectional survey of 7600 citizens in Australia, Belgium, Canada, France, Switzerland, and the United States. We find that some attitudes toward governance are indeed correlated with language, despite different nation-state contexts. In particular, French-speakers have different preferences for territorial centralization, while the governance attitudes of English-speakers are almost indistinguishable across countries. These findings allow us to refine and reconcile two common assumptions in the literature: that linguistic diversity leads to heterogeneous policy preferences, and that national integration masks cultural differences.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic confronted decision makers worldwide with some hard choices: safeguarding public health without unduly restricting personal freedoms and overall economic activity (e.g. Engler et al. Citation2021). In federations, an additional challenge consisted of vertically and horizontally coordinating governmental decisions (Chattopadhyay et al. Citation2021; Lecours et al. Citation2021; Steytler Citation2022). That task would seem even more demanding in multilingual federations such as Belgium or Canada with a history of intergroup conflict as well as in otherwise deeply polarized countries such as the USA, where suddenly everything is political (e.g. Birkland et al. Citation2021; Goelzhauser and Konisky Citation2020; Mason Citation2018; Mullin Citation2021). Dealing with the pandemic thus not only became a hard test for state capacity but also for societal cohesion (Casula and Pazos-Vidal Citation2021; Jedwab and Kincaid Citation2019).

Ironically, more polarization need not necessarily be bad for cohesion if it maps onto a different dimension than the one that is currently salient. Just as linguistic and religious cleavages can cut across and thereby weaken each other (Rae and Taylor Citation1970; Selway Citation2011), so could similar preferences on how to govern during the COVID-19 pandemic bring together otherwise divided groups – francophone and anglophone Canadians, for instance. This is precisely what seems to have occurred in Australia (Murphy and Arban Citation2021): despite its dual and bipartisan nature largely reflecting the US system, federal and state leaders generally cooperated well across the aisle.Footnote1 But in which direction societal reality developed, i.e. how much more or less internally divided federations have become, remains as yet unexplored.

A second reason for studying attitudes towards governance in times of crisis is that it matters for effectiveness (Mizrahi, Vigoda-Gadot, and Cohen Citation2021). While all democratic decision-making requires public acceptance, the COVID-19 crisis distinguished itself in two important aspects from previous crises: speed and degree of intervention. Decision makers had to act very quickly, and the effectiveness of their policies depended heavily on popular compliance as it targeted citizens directly and intimately (Wu Citation2021). Others have already shown that public opinion is less important in times of crisis, as decision makers privilege output over input legitimacy (Toshkov Citation2011; Weiler Citation2012), which explains how even unpopular measures are adopted. Moreover, time pressure means that the electorate is less able to influence decisions through habitual channels such as elections or referendums. For instance, political reforms in the aftermath of the 2008 economic crisis were quite effective albeit entailing substantial compliance and coordination costs (Zahariadis Citation2012). By contrast, if large parts of the citizenry had decided to ignore public health measures such as mask wearing, the SARS-CoV-2 virus could have continued to spread without restrictions. Hence, citizen attitudes matter for comprehending behavioural compliance and, through this, also state capacity.

Third and finally, if territorially entrenched cultural groups or ‘communities’, as they are constitutionalized in Belgium (Art. 2), really possess their own social norms, collective identity, and public values because of their distinct language, then similarities across states should translate into similarities in governance attitudes, too. Indeed, much of the social science literature assumes the heterogeneity of political preferences to map onto linguistic, religious, or ethnic differences (e.g. Laitin Citation2000). Literature on information technology (social media, e-government) also shows that language plays an important role in how preferences are translated into political decisions (e.g. Androutsopoulou et al. Citation2019; Jaeger and Thompson Citation2003; Zheng Citation2013). Yet states are still the preferred unit of analysis in cross-sectional analyses, departing from the assumption that political boundaries neatly demarcate cultural communities. Shedding light on systematic intergroup differences and especially similarities across states in terms of governance attitudes thus also contributes to our overall understanding of the connection between language, culture, and politics (see Choi, Poertner, and Sambanis Citation2021; Porcher Citation2021).

In this article, we accordingly compare governance preferences during and regarding the pandemic along two axes: between different linguistic groups of the same country (French vs. non-French speakers in Canada, Belgium, and Switzerland) and within the same linguistic sphere but across different countries (French speakers across Canada, Belgium, Switzerland, and France; English speakers across Canada, Australia, and the USA). By ‘governance’ we mean the overall political-administrative structure in which collectively binding decisions are taken (e.g. Hooghe and Marks Citation2003, 236–237). To better account for the complexity of real-world settings, where multiple aspects such as the level of decision-making (central, regional, or both together) or the involvement of scientific experts are simultaneously present, we ran the same conjoint experiment among all the ca. 8000 respondents in all six countries (see Bansak et al. Citation2021 for a summary of that technique). We then engage in subgroup comparisons along the mentioned national and linguistic characteristics of respondents (Leeper, Hobolt, and Tilley Citation2020).

We find that some governance attitudes indeed differ along language. Yet while French speakers profess similar attitudes towards the involvement of stakeholders, they vary cross-nationally in their preferences for the relevant level of decision-making. Anglophones, in turn, are almost indistinguishable in their governance preferences across countries, which could, however, also be due to their state-wide majority position throughout. In doing so, our findings relate to the literature on social sorting, which argues that the convergence of social characteristics is a driver of affective polarization (Mason Citation2015; Citation2016; Citation2018). However, our study also suggests that government preferences in the context of COVID-19 largely cut across existing differences in language groups, thereby attenuating polarization between them. Moreover, the study contributes to the literature on federalism and Covid-19 management (Chattopadhyay et al. Citation2021; Hegele and Schnabel Citation2021; Schnabel and Hegele Citation2021; Steytler Citation2022) by revealing the preferred resolution method throughout to be federal-regional cooperation.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. The second section briefly rehearses existing scholarship on language, cultural diversity, and governance attitudes. The third section presents and justifies our cases and lists the hypotheses. The fourth section details the research design and data collection; the fifth section discusses our findings. The final section summarizes and addresses this study’s limitations and ways forward.

Language, cultural diversity, and governance attitudes

Harry Eckstein’s (Citation1988) by now famous ‘congruence’ theory held that state structures, to be stable, needed to reflect societal expectations and preferences. More recently, Erk (Citation2007) explored the way in which linguistic differences in federal states influence their institutional structure. There is, of course, more to cultural identity than just language (see, for instance, Hooghe and Mark’s (Citation2020) post-functionalist theory). But when it comes to public affairs, unlike religion, history, race, or other cultural markers that have served as a specific group’s boundary demarcations and which can remain more or less in the background, every polity must decide in which language(s) it conducts its affairs and communicates with its citizens (Brubaker Citation2013). Moreover, with secularization having attenuated many of the erstwhile hotly debated or even fought-out religious divides, language has played an important role in secessionists conflicts from Quebec via Flanders and Catalonia to Corsica.

There are two main mechanisms through which the language we (mainly) speak or which is our mother tongue can influence our political preferences.Footnote2 A first operates through communication and socialization. Accordingly, each language community forms its own cultural socialization space where ideas are exchanged in shared media outlets, literature, the arts, and through personal contact with friends and family. Standardization and literacy also ensure vertical transmission, i.e. from one generation to the next (Brubaker Citation2013). Several studies have documented how language strongly influences individual attitudes (Darr et al. Citation2020; Hopkins Citation2015; Lee and Pérez Citation2014; Pérez Citation2016; Pérez and Tavits Citation2019). Especially if tied to a specific territory and distinct political history, language greatly influences citizens’ political attitudes in providing certain baseline values and expectations (Brubaker Citation2013; Shair-Rosenfield et al. Citation2021; Almond and Verba [Citation1963] Citation2015).

Yet language is never just a means, but also always a greater or lesser symbol of identity, intergroup diversity, and intra-group unity. A second mechanism thus operates through status and power (e.g. Popelier Citation2021; Shair-Rosenfield et al. Citation2021). Culture-marker theory identifies language, the ‘human and non-instinctive method of communicating ideas, emotions, and desires’, as an important cultural construct that indirectly affects people’s attitudes (e.g. Wright Citation2016). Most (sub-)cultural identities have developed their own linguistic system to demarcate their members. As a result, people tend to hold more positive attitudes towards those who share the same cultural background (Schildkraut Citation2005), trusting them more (Hechter Citation2013; Hu Citation2020). Speaking a language that is distinct from that of the political majority can also give rise to a specific collective identity ‘under siege’, and it is that socio-political situation – rather than language as such – which could cause specific preferences. It is hardly surprising then that the existence of more than one language group often translates into a specific set of political institutions such as, precisely, federal governance (Gagnon Citation2022; Rothstein Citation1996; Swenden, Brans, and De Winter Citation2006).

In contexts where different tongues have historically been spoken and remained territorially entrenched, language should therefore amount to a good proxy for cultural diversity (e.g. Laitin Citation2000, 142). The case for the congruence of linguistic, cultural, and political heterogeneity would be significantly strengthened if two or more groups speaking the same language but inhabiting different states were to possess identical attitudes. In turn, if members of different linguistic communities inhabiting the same state had identical political attitudes, that case would be weakened. At the very least, we would then have grounds to investigate the conditions under which linguistic differences sometimes vanish for the purposes of political behaviour and do not inspire separate political parties, e.g. in Switzerland (see Mueller and Bernauer Citation2018), whereas elsewhere they do, e.g. in Belgium (e.g. Popelier Citation2021), and how this connects to crises.

Our focus on attitudes towards governance as the dependent variable has two reasons. First, linguistic minorities and majorities are deeply affected by political structures, being provided either veto power over national, regional autonomy over own decisions, or both (e.g. Hooghe et al. Citation2016; Juon Citation2020; Mueller Citation2024). Yet there is little systematic evidence on how different – or similar, across states – language groups perceive their governance structures (Arikan and Ben-Nun Bloom Citation2015; Heinisch, Massetti, and Mazzoleni Citation2018). Some evidence on public attitudes towards governance has emerged from European studies, but rarely focusing on language (Anderson Citation1998; Kuhn Citation2019; McLaren Citation2005; Vasilopoulou and Wagner Citation2017).

Second, regardless of linguistic patterns, states are increasingly confronted by questions about the accountability of their institutions and decisions, driven in turn by the emergence of social media (Stamati, Papadopoulos, and Anagnostopoulos Citation2015). Consequently, various democratic alternatives have emerged, from instituting mini-publics to outsourcing to scientific experts (Gerber et al. Citation2018; Michels Citation2011). Although potentially of great import to political minorities, we know little of their attitudes towards such new (or ancient, in the case of citizen assemblies) forms of governance. Minorities could be more sympathetic towards democratic innovations as they promise to introduce deliberative elements into otherwise majoritarian structures. Or they could suspect them to amount to yet another channel for majority dominance. Different cultures might also have different preferences regarding direct democracy, trade unions, or transparency.

Note that in all these discussions, our scope conditions are set by (a) the existence of liberal-democratic states; (b) at least two official language groups within such a state; and (c) a high degree of territorial boundedness of these groups. The rationale for these parameters is that without freedom of speech, of assembly, and competitive elections, group members cannot freely form and act upon their beliefs. The territorial boundedness of linguistic groups reifies majority-minority relations defined by language, providing them with added salience (e.g. Erk Citation2007). Our analyses thus shed light on the connection between language, culture, and democratic governance attitudes.

Despite their apparent relatedness, the two mechanisms – communication and identification – have slightly different implications. Relying on language as communication, we would expect even French- or English-speakers living in different countries to possess identical preferences, on the one hand, and for differences between language groups of the same country to always emerge, on the other:

Hypothesis 1a: Speakers of the same language have, on average, identical governance preferences regardless of their country of residence.

Hypothesis 1b: Speakers of a different language have, on average, different governance preferences despite living in the same country.

Hypothesis 2: Speakers of the same language differ in their governance preferences to the extent that they form a demographic or political majority or minority in their country.

Data and methodsFootnote3

Our data come from an online survey conducted in winter 2020/2021 across six Western democracies: Australia, Belgium, Canada, France, Switzerland, and the United States. The dependent variable was assessed using a conjoint experiment on how public responses to the pandemic should be taken, with response options varying along five dimensions: the extent of territorial de/centralization; (not) involving health experts, corporate stakeholders, and ordinary citizens; and with what degree of transparency. Prior research shows that the decision per se is not always the central criterion for its social acceptance, but that it matters rather how it was taken (Dermont et al. Citation2017; Terwel et al. Citation2010). At the time of the survey, all six countries were in the middle of the second wave, increasing our confidence that respondents understood both the questions and reply options.

Few other contexts are as fruitful for the exploration of differences in political culture across linguistic communities as federations. Some authors even regard federalism as the result only of intergroup differences and the need to both protect cultural diversity and create political unity (Erk Citation2007; Livingston Citation1952). Linguistics, religious, and ethnic ascriptives top the list in cultural markers, it being understood that the various communities have different needs and pursue different political priorities (Brown Citation2004; Citation2013; Cole, Kincaid, and Rodriguez Citation2004; Fafard, Rocher, and Côté Citation2010; Kincaid and Cole Citation2011; Reuchamps, Dodeigne, and Perrez Citation2018). However, to our knowledge none of these studies – not even those focusing on Belgium and Canada – explicitly or exhaustively compare the attitudes of French-speaking citizens with those held by members of non-French-speaking majorities. In Switzerland, studying the political attitudes of linguistic groups can look back on a long history, facilitated by the frequent use of referendums to decide collectively binding questions and, since the 1970s, representative post-referendum surveys. Classic approaches such as those by Seitz (Citation2014) and Bolliger, Zürcher, and Linder (Citation2008) use local, district and cantonal results to calculate the extent of differences in voting behaviour between linguistic regions as well as their internal homogeneity.Footnote4 In addition, there have been a few studies that analyse public attitudes of English speakers vs. linguistic minorities (Kincaid and Cole Citation2011; Raney Citation2010).

Comparing linguistic groups across and within our six countries provides three analytical advantages. First, we can compare francophones with their non-francophone (Dutch, English, and German speaking) co-citizens to detect intrastate variation. Second, we can compare francophones and anglophones across countries, and even three different francophone minorities with each other to detect intra-linguistic similarity. Belgium, Canada, and Switzerland are all federations with officially recognized and territorially entrenched francophone communities amounting to some 41%, 23% and 23% of the total population, respectively.Footnote5 French is, of course, the only official language of France (e.g. Art. 2 of the French Constitution of 1958, last revised in 2008).

Third, we can compare these three francophone minorities with the French ‘kin state’ (Brubaker Citation1995; Sabanadze Citation2006). This is a particularly lucky circumstance since from the point of view of intra-linguistic similarities, we could expect that French speakers outside of France emulate what they see in this ‘lead country’ (e.g. Kriesi et al. Citation1996; Mueller and Dardanelli Citation2014). In the main, France is not only (still) very centralized, but is also rather dominated by Paris and its ENA-formed elite and experts, with little involvement of ordinary citizens (hence, among others, the Gilet Jaunes movement and Le Grand Débat National) but powerful stakeholders such as trade unions. If there is indeed a peculiar francophone political culture, similar governance attitudes should thus be observed among French speakers regardless of their majority/minority status or country. Their position as minorities should by contrast pull them in the direction of preferring more decentralization.

Analytically, we rely on the conjoint analysis as ‘a tool to identify the causal effects of various components of a treatment in a survey experiment’ (Hainmueller, Hopkins, and Yamamoto Citation2014). In contrast to traditional experiments that focus on one specific characteristic ( = treatment), a conjoint experiment considers the more realistic multidimensionality of an object. Here, the conjoint experiment is used to determine which attributes of the decision-making process play a particularly important role in respondents’ assessment. Such an assessment better approximates reality than a conventional survey on individual characteristics, since any decision-making framework can always be described and assessed based on several characteristics, not just one. The conjoint experiment also reduces the risk of socially desirable responses, which a direct query of individual characteristics might entail. However, this method only allows us to identify the importance of some attributes over others that belong to the same dimension, and we can only show their association (but not causal relation) with language groups.

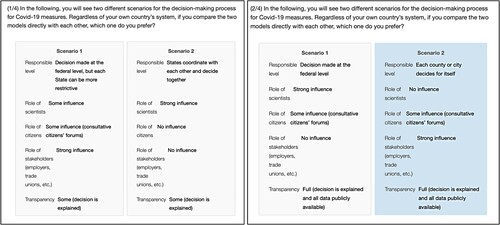

Our experiment uses the COVID-19 responses that have been introduced in most countries of the world beginning in 2020. This provides us with the unique opportunity to ask citizens from different states about their preferences in a largely identical situation. Our respondents were confronted with a variety of decision-making processes on policies to control the spread of the pandemic – without, however, defining these policies themselves. Each respondent was presented four times with two scenarios of how COVID-19 responses should be taken. Each choice between two scenarios combined different aspects of multilevel governance; the inclusion of experts, citizens, and stakeholders; and the desired level of transparency (see ). For each comparison, respondents had to indicate which of the two scenarios they preferred. Each decision-making scenario consisted of a random combination of characteristics; the order of the five dimensions remained constant throughout (see Figure A1 for screenshots).

Table 1. Dimensions and characteristics of the conjoint analysis.

The first dimension refers to different levels of government. Maggetti and Trein (Citation2019) point out that the social problems a country faces are strongly linked to the governance mode. Originally used in the European integration literature (Marks Citation1993), the concept of multilevel governance (MLG) has emerged to study processes and institutions that shape policies through the interaction of public (and private) authorities at different levels. In doing so, levels refer not only to vertical interaction – top-down and bottom-up – but also to the collaboration of sub-, supra-, and international institutions (Börzel and Hosli Citation2003; Hooghe and Marks Citation2003). Within that dimension, we distinguish five different levels, in particular since COVID-19 responses have been observed to be located at different scales, too (Capano et al. Citation2020). To begin with, a decision could be directly made at federal or central level, either binding for everybody (1) or in such a way that regions can be more restrictive (2). Regions could also be the main locus of decision-making, as seen in Canada, the US, and Mexico (Béland et al. Citation2021). In this case, regions will either coordinate with each other (3), for instance through interregional conferences (see Broschek Citation2015), or decide in isolation from each other (4). Finally, a municipal solution is also conceivable (5), as particular urban centres were strongly and differently affected by the pandemic, so that targeted policy responses were or should have been found for and by them.

Our second dimension captures the desired level of expert involvement or technocracy (e.g. Caramani Citation2017). Many governments have constituted scientific boards to help them understand the virus and advise political leaders on measures combating the pandemic (Cairney Citation2021). These boards channel information between scientist and policymakers, but it is highly debated how much influence they should have. The third dimension concerns the involvement of citizens, or participatory governance (Fischer Citation2012, 457). This approach empowers citizens and other non-state actors to directly influence collective decisions. Often, these actors do not have access to full information, which is why participatory governance seeks to address ‘democratic deficits’ by promoting citizens’ information, awareness of their rights, participation, and influence. Even though the COVID-19 pandemic came fast and fierce, the involvement of citizens is not implausible, as rarely policy measures have affected such a substantial part of the population. Yet we distinguish only between no influence (1) and some influence (2), e.g. advisory citizen forums, as we believe strong (and binding) involvement to be too unrealistic.

The fourth dimension represents the involvement of stakeholders such as employers, trade unions, or professional associations. While decision makers are authorities whose involvement (timing and deployment of resources) in a public policy is usually very formalized, stakeholders include all actors or interest groups who hold an interest in a public measure; their participation is, however, mostly informal and voluntary. Social actors include business groups, associations, social movements, and the media. Often, these stakeholders use their own resources, be it their network, skills, or human resources, to influence public measures. Our fifth and final dimension covers the transparency of decision-making – an important criterion for throughput legitimacy (Héritier Citation2003; Strebel, Kübler, and Marcinkowski Citation2019). Decision makers often justify their decision based on reasons to gain greater legitimacy. During the COVID-19 pandemic, however, there have also been many calls to make the (collected) data on infected and deceased individuals publicly available. Thus, we distinguish between no (1), some, (2) and full transparency (3), i.e. a situation in which all data is openly and easily accessible. We refrained from randomizing the order of dimensions to avoid confusion.Footnote6

In total, some 7600 individuals completed the survey (). We oversampled minority languages to receive a substantial number of respondents for every main official language group in our countries (Chen, Stubblefield, and Stoner Citation2020). All samples were purchased from and surveyed via Qualtrics, with age, gender, residence, and education quotas specified beforehand. Citizens of officially multilingual countries could choose and change the language of their survey anytime. Nevertheless, one of the first questions asked respondents to indicate their mother tongue, and for our purposes here, we only assess and compare French and English speakers in Canada, French and Dutch speakers in Belgium, French and German speakers in Switzerland, French speakers in France, and English speakers in Australia and the USA. in the Appendix provides a breakdown of socio-demographic attributes, boosting our confidence in the validity of cross-group comparisons. does the same for personal affectedness by the pandemic.

Table 2. Sample size(s) and distribution of languages by country.

Statistical modelling is based on Hainmueller, Hopkins, and Yamamoto (Citation2014, 11f.), who also suggest reporting average marginal component effects (AMCEs). These are defined as ‘the average difference in the probability of being preferred […] when comparing two different attribute values’ (Hainmueller and Hopkins Citation2015, 537). AMCEs result from an OLS regression with the binary decision variable as the dependent and the attribute values as the independent variables. However, since we are interested in comparing differences in preferences across multiple groups, even conditional AMCEs are unsuitable for they represent ‘relative, not absolute, statements about preferences’ (Leeper, Hobolt, and Tilley Citation2020, 213). Our main estimators of interest will therefore be conditional marginal means (on which conditional ACMEs build), differences therein, and the coefficients on the interaction terms between grouping variables (language and country) and feature levels (Leeper, Hobolt, and Tilley Citation2020, 220). We use the R-package ‘cregg’ for our empirical analyses (Leeper Citation2020). Standard errors are clustered at the individual, respondent level.

Findings

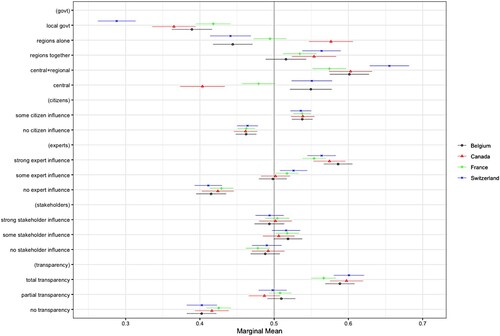

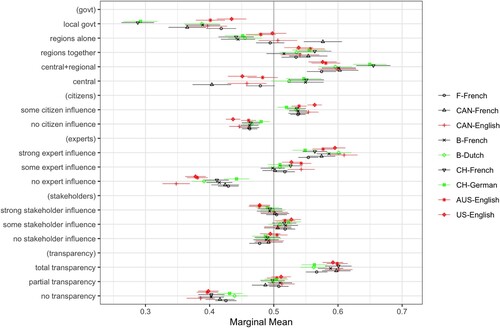

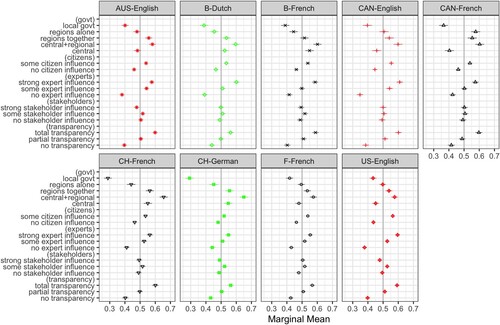

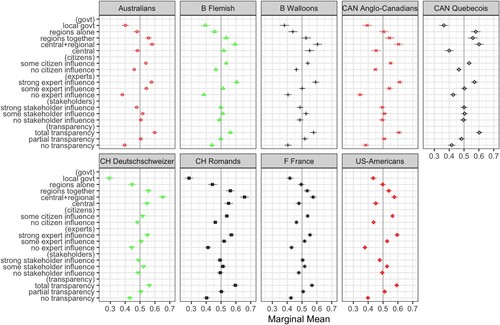

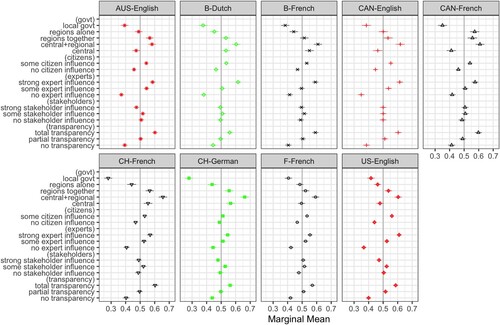

and show the results of our conjoint experiment for French and English speakers only by country of residence, respectively. Shown are conditional marginal means, i.e. estimators of the absolute ‘level of favorability toward profiles that have a particular feature level, ignoring all other features’ (Leeper, Hobolt, and Tilley Citation2020, 110) and conditional upon speaking French/English and residing in one of the mentioned countries. Figures A2 and A3 in the Appendix show conditional marginal means for all nine language-country groups studied here.

reveals virtually identical levels of favourability among francophones regarding citizen influence (some rather than none), expert influence (strong rather than none), stakeholder involvement (indifferent), and transparency (total rather than none). Only the French prefer some over no stakeholder input, albeit only just. Where francophones differ greatly among each other is on the preferred territorial scale of governance, although even here the order of preferences is largely identical: Swiss-French are most in favour of one step short of full centralization, that is the federal government decides but cantons can enact more restrictive rules. Regional collaboration and outright centralization come joint second. However, centralization is clearly not the preferred option of Canadian francophones, and it negatively affects favourability even among the French. Seeing local governments in charge is unappealing to all groups, as is regional autonomy for Swiss and Belgian francophones, but for Canadian francophones such freedom is the second most favoured option. Belgian francophones are the most pro-centralization, either in pure or attenuated form.

Turning to anglophones, highlights further cross-country similarities. Again, almost everywhere the average English-speaker prefers some rather than no citizen influence, strong or some expert influence rather than none, and total rather than no transparency. But now there are also differences regarding stakeholder involvement, with US and Australian residents preferring some over strong input, whereas Canadians are – like the francophones – indifferent. In turn, the distribution of preferences for the level of governance is more similar among anglophones than francophones. Central regulation with the possibility for regional deviation upwards is again the most preferred option but overlaps with inter-regional cooperation everywhere. Apart from centralization tout court negatively affecting scenario attractiveness for US and Canadian anglophones but not Australians, there is no further difference in that dimension of governance.

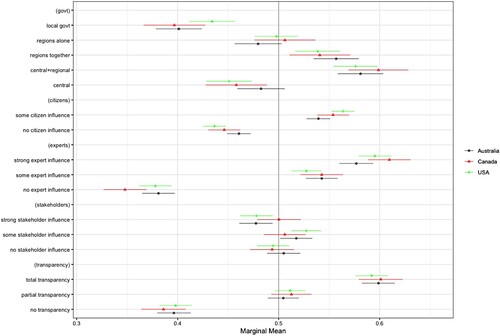

That French and English speakers exhibit largely identical governance preferences despite inhabiting different democracies (as per H1a) is of course no proof that this is so because of language. In fact, subtle central regulation is the preferred option by all nine groups, as is some citizen and strong expert influence as well as total transparency. Still, precisely by looking at absolute levels of favourability are we able to say not only something about the order of preferences but also their level. This is why we now calculate differences between conditional marginal means for each country-pair within a given language group. For next to language and country of residence also a group’s majority/minority status could be important.

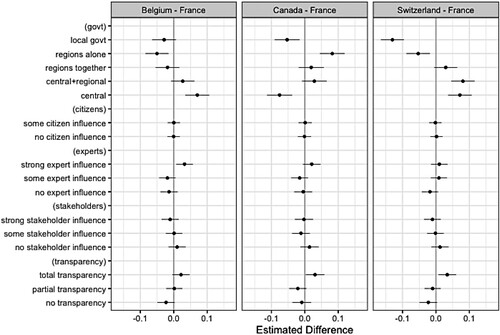

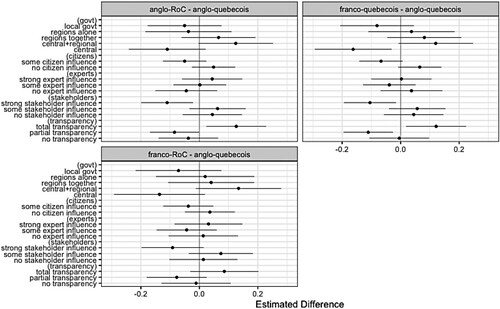

falsifies H2 for governance levels: Belgian and especially Swiss francophones (two minorities) are more favourably disposed towards centralization than even the French (the titular nation), but the Canadian francophone minority much less. To assess anglophones in different majority/minority constellations, we separated those living in Quebec (where they are a minority) from those living in the rest of Canada (RoC), where they are the majority. (top left) shows no differences in terms of centralization preferences for Canadian anglophones depending on provincial residence, and only one other difference (regarding transparency). Again, hardly evidence to bolster H2. This does not mean that linguistic majority/minority status never plays a role, only that during the peak of the pandemic differences regarding governance attributes cut across the language divide.

Figure 3. Differences between French speakers by country. Reading example: Belgian francophones are more favourably inclined towards centralization than the French.

Figure 4. Differences between English and French speakers by residence in Canada. Note: ‘anglo-RoC’ = English speakers living in rest of Canada; ‘anglo-quebecois’ = English speakers living in Quebec; ‘franco-quebecois’ = French speakers living in Quebec; ‘franco-RoC’ = French speakers living in rest of Canada.

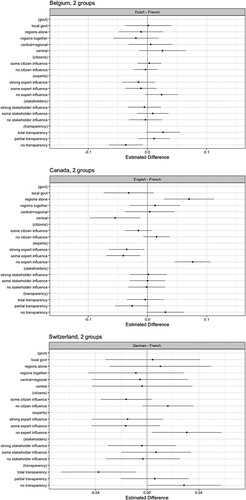

Turning, finally, to differences within multilingual federations, shows their almost complete absence in Belgium and Switzerland, contrary to H1b. Belgians profess basically identical governance preferences, ethno-political (and especially partisan) appearances to the contrary. In Switzerland, too, francophones desire less expert influence and more transparency than German-speakers but have otherwise similar preferences. Only in Canada do we observe both greater centralization preferences among francophones vis-à-vis anglophones and a greater embrace of experts. On balance, then, we lean towards rejecting H1b: at least in the countries and crisis surveyed here, there were more similarities than differences between different language groups of the same country.

As a robustness check, we restricted our sample to (a) only those who indicated as their mother tongue the official language of the region, province, or canton they inhabited; and (b) those who correctly indicated that to contain the Covid-19 virus, one should avoid crowded places. Results are virtually identical (Figures A4 and A5). We additionally computed F-statistics as per Leeper, Hobolt, and Tilley (Citation2020, 218–219), for each feature and for all features as a whole. The results are shown in and again confirm the above discussion.

Table 3. ANOVA test results for between-group differences.

In general, it thus seems that citizens give preference to output legitimacy, i.e. dealing effectively with the spread of the virus and adequately managing the economic, social, and political repercussion. The central government is best placed to harness economies of scale: pooling expert knowledge, managing the distribution of key material, providing hardship relief, establishing clarity regarding business openings and closures, etc. Centralization might thus also be the preferred outcome of groups that in normal times demand regional empowerment – especially if centralization also means compensating individuals for financial losses (i.e. central responsibility). However, the acceptance of central regulation is tempered not only by at least some regional autonomy (for upwards deviation in terms of strictness), but also conditional upon citizen, expert, and sometimes even stakeholder influence as well as full transparency of decision-making. Despite variations in size, status, and state structure, that ideal governance arrangement is pretty much identical across the countries and groups surveyed here.

Why would a transnational French political culture as per H1a fail to materialize regarding multilevel governance preferences? Federalism is an appealing solution to cultural minorities because by carving up a state’s territory into more or less autonomous provinces, chances are that overall minorities become regional majorities. What is more, next to gaining self-rule, through shared rule cultural minorities typically end up with more weight at the national level than their demographics would entitle them to if simple ‘one person, one vote’ rules applied (Mueller Citation2024). Regarding governance preferences, the French-speaking minorities surveyed might know exactly – in particular during a pandemic – that the federal state will not take measures against their will as they are a critical veto power, either formally (as in Belgium) or informally (as in Switzerland). Notably, the principle of inter-regional equality, which is almost a sine qua non for federal design, will in certain constellations boost minority influence, act in a counter-majoritarian fashion, and thus ‘artificially’ enhance the status of language groups. Only where there are no such federal safeguards, as in Canada, do we see the francophone minority desiring greater regional autonomy even in crisis periods. To this must be added the significantly greater state capacity of the historic home nation of French speaking Canadians, i.e. the Province of Quebec, with basically as many inhabitants as the whole of Switzerland or Belgium. Canada also exhibited the greatest within-country differences mapping onto language, Belgium the smallest.

By contrast, on the question of how experts, ordinary citizens, and trade unions should co-govern, there is indeed a shared understanding among French speakers as per H1a, as there is also (albeit less clearly) among Anglophones. This would mean that a language that has developed hundreds of years ago and sailed over entire oceans still (partly) determines our political attitudes. That finding further provides strong evidence that French-speaking citizens have a systematically different understating of l’Etat, which goes beyond the actual administration and even regulates the relationships between public and political actors, because they speak the same language and thus perpetuate shared cultural traits. However, to test for actual causal effects would have necessitated manipulating that aspect at individual level. All that a conjoint experiment shows is that this or that aspect increases scenario favourability within a group, but not why.

Discussion and implications

Our results suggest a general preference for centralization, increased consultation, and expanded participation in times of crisis shared across language groups and countries. This finding is consistent with Hegele and Schnabel (Citation2021), who study the Covid-19 management in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland. Although management styles differ, the authors argue that Austria and Germany relied on strong coordination between the federal and regional levels, while Switzerland took a more unilateral approach. Furthermore, Schnabel and Hegele (Citation2021) show that governments coordinated more intensively during the first wave of the Covid-19 crisis when jurisdiction was shared, problem pressure was high, and measures were (re)distributive in nature. This study builds on that literature by showing that public preferences during Covid-19 were similarly distributed.

Although the countries selected here all possess some particularities, French and English stand for broader linguistic variation. Many countries either possess a multilingual population or are confronted with immigrants unable to understand the sole official language. More recently, several studies have discussed multilingualism as a challenge for political decision makers and public administration (Benavides et al. Citation2021; Ott and Boonyarak Citation2020; Shen and Gao Citation2019; Zwicky and Kübler Citation2019). Although this does not mean that the findings of our analyses can simply be generalized, our results point out that the language best spoken partly maps onto citizens’ political attitudes, providing valuable implications for policy-makers in crisis times.

Knowledge about the preferences of citizens is undoubtedly valuable for public administrations (e.g. Ahn and Campbell Citation2022). If citizens form their attitudes (also) along language group lines, this has implications for both crisis management and policy decisions. In terms of crisis management, taking seriously language affiliations could help in more effectively communicating with and mobilizing different groups during a crisis. For example, if policy makers know that a particular language group is particularly affected by a crisis, they could ensure that information and resources are provided in their language to help them better understand and respond to the situation. Maldonado et al. (Citation2020) show that no government provided risk communications on disease prevention targeting people in refugee camps or informal settlements during the Covid-19 pandemic, which might have helped fight the dissemination of the virus. Moreover, ‘community navigators’ were hired during the global pandemic in some municipalities in the United Sates to address cultural and language issues. In doing so, they translated all communication forms and formats to specific language and ethnic communities (Dzigbede, Gehl, and Willoughby Citation2020). Policy makers may not only translate policy responses to different languages, but also adapt their content depending on the language group. I.e. the communication could be more explicit and focused for language communities that are more critical towards certain policy measures.

In terms of the substance of political decisions, understanding that language group affiliations of citizens matter could help to more effectively design and implement policies that address the needs and concerns of different groups. For instance, Borrelli (Citation2018) shows that language barriers can hinder policy implementation: some street-level bureaucrats struggle with the abstract legal corpus handed down to them. Moreover, this knowledge can help policy makers to identify potential areas of disagreement or misunderstanding between different language groups, and to develop policies that are more inclusive and responsive to the needs of these groups. This could involve creating policies that specifically address the concerns of different language groups or implementing measures to ensure that all language groups have access to information and services (Cairns Citation1988; Ingram, Schneider, and DeLeon Citation2019). Additionally, this knowledge could help to anticipate potential conflicts or challenges that may arise between language groups, and to develop strategies for addressing these issues in a way that promotes understanding and cooperation. Overall, understanding the role of language in shaping citizens’ attitudes can be a valuable tool for developing effective and inclusive policies (see Vinopal Citation2020).

Scholarship on multinational federalism has perhaps taken this conclusion furthest in arguing that certain governance arrangements better protect the cultural identity and by implication governance preferences of demographic and political minority groups than others (e.g. Gagnon Citation2022). The famous challenge is of course to create and maintain ‘a national government that would be at one and the same time energetic and limited’, in Elazar’s (Citation1987, 136) words. A majority across groups and states surveyed here would seem to have found the realization of that goal in a form of centralization that allows regions to deviate upwards. This particular arrangement contains a sufficiently ‘energetic’ element in the form of state-wide solidarity, uniformity to keep the country together, and ensure an effective crisis response (especially vis-à-vis a virus does not recognize territorial borders) whilst also being ‘limited’ enough to protect regional diversity and autonomy.

Finally, our findings also relate to the literature on social sorting. According to Levendusky (Citation2009), social sorting occurs when social characteristics such as religion, race, and ideology manifest themselves in certain parties. This sorting can result in parties becoming increasingly socially homogeneous, leading to affective polarization (Mason Citation2016). While previous studies have focused on the U.S. context (Lane, Moxley, and McLeod Citation2023; Mason Citation2015; Citation2016; Citation2018), the issue of social sorting has only recently been examined for other cultural contexts (see Harteveld Citation2021). This comparative study has also shown that governance preferences tend to be very similar for different linguistic groups within the same country, and for the same linguistic group in different countries. However, our findings suggest that crises – such as the Covid-19 pandemic – may cut across existing differences between language groups and thus reduce the space that social sorting has created between political parties. Indeed, previous studies have shown that crises can lead to a scrutinization of governance preferences in the hope for more effective policy solutions (Casula and Pazos-Vidal Citation2021; Dunlop, Ongaro, and Baker Citation2020; Liu et al. Citation2021).

Conclusion

Scholars of multilevel governance and federalism have long discussed whether and how language influences political attitudes. The consistently observed pattern that at least some differences occur between language groups of the same state has served as the origin for two explanations: first, languages influence group members’ beliefs and attitudes through communication and a resulting shared public sphere (Miller and Banaszak-Holl Citation2005) that can even transcend centuries-old nation-state borders; second, language could serve as a symbol for different groups within a country that seek to maximize their autonomy (Gagnon Citation2022).

We investigated these explanations through a unique cross-national survey conducted online in six countries: Australia, Belgium, Canada, France, Switzerland, and the United States. In our study design, different attributes of a decision were randomly assigned to simulate a governance process during the COVID-19 pandemic. We covered degrees and types of territorial de/centralization, the influence of experts, citizens, and stakeholders, and the degree of transparency. Specifically, our study makes four key points: First, both among French and English speakers some remarkably similar governance preferences existed during the COVID-19 pandemic even when living in different countries. These similarities pertained to degrees of citizen influence, strong expert involvement, and full transparency. This suggests that, at least in times of crisis, common values and concerns are shared within language spheres, challenging preconceived notions about the traditional influence of national characteristics on political attitudes. Second, an overarching preference for centralization – either directly or through shared rule – emerged as a significant theme across both language groups and countries. Citizens, regardless of language, appear to favour a central government that can effectively coordinate crisis management efforts. However, this preference is nuanced, with a simultaneous desire for some regional autonomy. Centralization becomes more acceptable if regions can deviate upward, demonstrating a delicate balance between centralized crisis response and the preservation of regional diversity.

Third, we examined the impact of linguistic majority/minority status on governance preferences. Surprisingly, French-speaking minorities in Belgium and Switzerland expressed a greater inclination towards centralization than even the French. In Canada, linguistic majority/minority status does not significantly affect the governance preferences of anglophones in Quebec and the rest of Canada. These findings challenge the idea that linguistic majority/minority status plays a decisive role in shaping governance preferences. Finally, while the study recognizes a common understanding among francophones and, to a lesser extent, anglophones, it underscores the complexity of attributing political attitudes solely to language. Our results suggest that language plays a role in shaping some shared cultural characteristics that influence attitudes towards the state. However, establishing causal effects would require manipulation at the individual level, highlighting a limitations of the study design.

Although we do not find a homogenous picture across our four francophone countries, the idea that language is related to political attitudes still appears to be appealing, if also controversial. When citizens’ attitudes are based on cultural aspects independent of specific political institutions, can they be influenced by factors such as the behaviour of political actors? How much in our evidence reflects the specific crisis mode of state responses to the pandemic, how much corresponds to ‘normal’ attitudes? These and others are questions we cannot answer here. Future studies should also examine which citizens are more likely be influenced by language vis-à-vis other cultural (e.g. religious), class, or personality factors (see Ricks Citation2020). The detected patterns will also most certainly differ for other policy issues, even if the COVID-19 pandemic provided an ideal example to compare cross-nationally. Likewise, media systems may vary across languages and interact with the observed effects (Erk Citation2007). Finally, the peculiarities of French and English could also be tested via studies of other transnational language groups and their kinstates, e.g. Spanish or Portuguese, and/or additional francophone and anglophone countries. Exploring the role of language in shaping citizens’ attitudes should also include experiments to tease out other factors that influence attitudes, such as culture or social norms (see John, Sanders, and Wang Citation2019). Overall, this research agenda would aim to provide a deeper understanding of how language impacts our understanding and opinion of political decisions and measures, and to inform policy makers and practitioners related to language and attitudes.

Our study also highlights the value of looking at language groups to understand political attitudes. First, even if our sample does not fully represent the population, there are still remarkable differences between language groups. Second, language, which has previously been used as a control variable to account for possible translation bias or some vague cultural dimensions, tends not to receive much public attention. In fact, Ward et al. (Citation2020) show that public attitudes do not always conform to traditional explanations such as the left-right dimension. Third, in our survey, citizens were able to indicate their preferences for governments while taking into account other characteristics of the decision-making process. Conjoint analysis may provide a more comprehensive assessment of personal governance priorities.

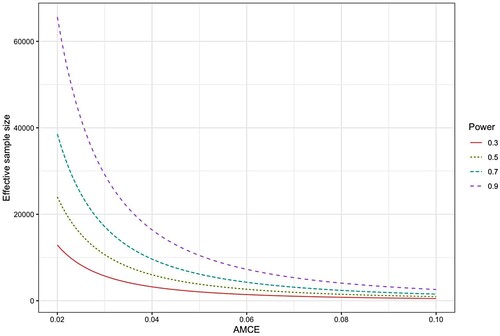

However, we cannot rule out the possibility that our findings derive not from actual language group differences or similarities, but are due to alternative explanations of governance preferences or even lack of statistical power (see and Figure A6). On the one hand, when we point to similarities in opinion between language groups in different countries as evidence, we are not implying that language is the sole determinant of political attitudes. Rather, we are suggesting that language may be one contributing factor among others. Our intention is to emphasize that linguistic commonalities may be associated with certain shared political perspectives, but this does not exclude the influence of other contextual factors. On the other hand, we must also be cautious in interpreting the results. We emphasize the need for additional research to delve more deeply into the complexities of this relationship. In sum, we recognize the need for further exploration and refinement in the study of multilingual federalism.

Thus, our study emphasizes the relevance of language for social science. It is likely that different trains of thoughts develop in a society that are influenced by cultural factors such as, above all but not only, language. However, this does not imply that attitudes are frozen in time and cannot be changed. The evidence from unitary France shows that even there, citizens prefer rather more regional authority when it comes to political decision-making on COVID-19. Indeed, citizens profess surprisingly similar attitudes independently of their political system: all favour coordinated, flexible centralization. This also opens the door for institutional reforms, particularly in times of crisis which strain the institutional (and mental and financial) capacity of most countries and their citizens. After all, the right or wrong response to the same crisis can bring otherwise divided people together, as in Australia and Belgium – or drive them even further apart, as in the USA.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Among the nine members of the newly created National Cabinet that comprises the Prime Minister and his eight subnational equivalents, five were from Labour and four (incl. the PM) from the Liberal Party, as per https://federation.gov.au/national-cabinet/members [January 2023].

2 Note that our research design does not allow us to directly test which of these two mechanisms has more traction.

3 See Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/2QS1TA for replication data.

4 The advantage of this approach is its full coverage and lessons learned from actual decisions, e.g. on Swiss accession to the European Economic Area in 1992. This and similar results with strong differences between the preferences of German- and French-speaking regions have led to the notion of Röschtigraben, named after a traditional potato dish prepared differently across groups (Büchi Citation2000; Von der Weid, Bernhard, and Jeannaret Citation2002).

5 As these figures are calculated differently, they must be compared with caution: In Canada, French was the ‘first official language’ spoken by 7.7 million Canadians, or 23.2% of the population, in 2011 (StatCan Citation2021). In Switzerland, 22.8% of residents indicated French as or one of their ‘main languages’ in 2019, but respondents could indicate more than one (BFS Citation2021). For Belgium, which lacks official language data, the share of French-speakers is inferred from parliamentary quotas: 62 French-speaking and 88 Dutch-speaking members compose the Chamber of Representatives (Belgium Citation2021). Mother tongue is not asked in national censuses, just like in France.

6 Thus, we are unable to exclude ordering effects. Future studies should at the very least randomize the order of attributes at the respondent level, as recommended by Bansak et al. (Citation2021, 26). Nor did we provide respondents with the option to rate the favourability of the presented scenarios.

References

- Ahn, Y., and J. W. Campbell. 2022. “Who Loves Lockdowns? Public Service Motivation, Bureaucratic Personality, and Support for COVID-19 Containment Policy.” Public Performance & Management Review 46 (1): 1–27.

- Almond, G. A., and S. Verba. (1963) 2015. The Civic Culture: Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Anderson, C. J. 1998. “When in Doubt, use Proxies: Attitudes Toward Domestic Politics and Support for European Integration.” Comparative Political Studies 31 (5): 569–601. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414098031005002

- Androutsopoulou, A., N. Karacapilidis, E. Loukis, and Y. Charalabidis. 2019. “Transforming the Communication Between Citizens and Government Through AI-Guided Chatbots.” Government Information Quarterly 36 (2): 358–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2018.10.001

- Arikan, G., and P. Ben-Nun Bloom. 2015. “Social Values and Cross-National Differences in Attitudes Towards Welfare.” Political Studies 63 (2): 431–448. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12100

- Bansak, K., J. Hainmueller, D. J. Hopkins, and T. Yamamoto.2021. “Conjoint Survey Experiments.” In Advances in Experimental Political Science, edited by James N. Druckman and Donald P. Green, 19–41. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Béland, D., G. P. Marchildon, A. Medrano, and P. Rocco. 2021. “COVID-19, Federalism, and Health Care Financing in Canada, the United States, and Mexico.” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 23 (2): 1–14.

- Belgium. 2021. The Federal Parliament. 29 December 2021. https://www.belgium.be/en/about_belgium/-government/federal_authorities/federal_parliament.

- Benavides, A. D., J. Nukpezah, L. M. Keyes, and I. Soujaa. 2021. “Adoption of Multilingual State Emergency Management Websites: Responsiveness to the Risk Communication Needs of a Multilingual Society.” International Journal of Public Administration 44 (5): 409–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2020.1728549

- BFS. 2021. Swiss Federal Statistical Office. 29 December 2021. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/en/home.html.

- Birkland, T. A., K. Taylor, D. A. Crow, and R. DeLeo. 2021. “Governing in a Polarized Era: Federalism and the Response of US State and Federal Governments to the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 51 (4): 650–672. https://doi.org/10.1093/publius/pjab024

- Bolliger, C., R. Zürcher, and W. Linder. 2008. Gespaltene Schweiz-geeinte Schweiz. Gesellschaftliche Spaltungen und Konkordanz bei den Volksabstimmungen Seit 1874. Baden: hier+jetzt.

- Borrelli, L. M. 2018. “Using ignorance as (un) conscious bureaucratic strategy: Street-level practices and structural influences in the field of migration enforcement.” Qualitative Studies 5 (2): 95–109.

- Börzel, T. A., and M. O. Hosli. 2003. “Brussels Between Bern and Berlin: Comparative Federalism Meets the European Union.” Governance 16 (2): 179–202. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0491.00213

- Broschek, J. 2015. “Pathways of Federal Reform: Australia, Canada, Germany, and Switzerland.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 45 (1): 51–76. https://doi.org/10.1093/publius/pju030

- Brown, A. J. 2004. “One Continent, two Federalisms: Rediscovering the Original Meanings of Australian Federal Ideas.” Australian Journal of Political Science 39 (3): 485–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/103614042000295093

- Brown, A. J. 2013. “From Intuition to Reality: Measuring Federal Political Culture in Australia.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 43 (2): 297–314. https://doi.org/10.1093/publius/pjs026

- Brubaker, R. 1995. “National Minorities, Nationalizing States, and External National Homelands in the New Europe.” Daedalus 124 (2): 107–132.

- Brubaker, R. 2013. “Language, Religion and the Politics of Difference.” Nations and Nationalism 19 (1): 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8129.2012.00562.x

- Büchi, C. 2000. «Röschtigraben»: Das Verhältnis zwischen deutscher und französischer Schweiz. Zürich: NZZ Verlag.

- Cairney, P. 2021. “The UK Government’s COVID-19 Policy: Assessing Evidence-Informed Policy Analysis in Real Time.” British Politics 16 (1): 90–116. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41293-020-00150-8

- Cairns, A. C. 1988. “Citizens (Outsiders) and Governments (Insiders) in Constitution-Making: The Case of Meech Lake.” Canadian Public Policy/Analyse de Politiques 14: 121–145. https://doi.org/10.2307/3551222

- Capano, G., M. Howlett, D. S. Jarvis, M. Ramesh, and N. Goyal. 2020. “Mobilizing Policy (in) Capacity to Fight COVID-19: Understanding Variations in State Responses.” Policy and Society 39 (3): 285–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2020.1787628

- Caramani, D. 2017. “Will vs. Reason: The Populist and Technocratic Forms of Political Representation and Their Critique to Party Government.” American Political Science Review 111 (1): 54–67. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055416000538

- Casula, M., and S. Pazos-Vidal. 2021. “Assessing the Multi-Level Government Response to the COVID-19 Crisis: Italy and Spain Compared.” International Journal of Public Administration 44 (11-12): 1–12.

- Chattopadhyay, Rupak, Felix Knüpling, Diana Chebenova, Liam Whittington, and Phillip Gonzalez. 2021. Federalism and the Response to COVID-19: A Comparative Analysis. London: Routledge.

- Chen, S., A. Stubblefield, and J. A. Stoner. 2020. “Oversampling of Minority Populations Through Dual-Frame Surveys.” Journal of Survey Statistics and Methodology 9 (3).

- Choi, D. D., M. Poertner, and N. Sambanis. 2021. “Linguistic Assimilation Does not Reduce Discrimination Against Immigrants: Evidence from Germany.” Journal of Experimental Political Science 8 (3): 235–246. https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2020.20

- Cole, R. L., J. Kincaid, and A. Rodriguez. 2004. “Public Opinion on Federalism and Federal Political Culture in Canada, Mexico, and the United States, 2004.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 34 (3): 201–221. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubjof.a005037

- Darr, J. P., B. N. Perry, J. L. Dunaway, and M. Sui. 2020. “Seeing Spanish: The Effects of Language-Based Media Choices on Resentment and Belonging.” Political Communication 37 (4): 488–511. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2020.1713268

- Dermont, C., K. Ingold, L. Kammermann, and I. Stadelmann-Steffen. 2017. “Bringing the Policy Making Perspective in: A Political Science Approach to Social Acceptance.” Energy Policy 108: 359–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2017.05.062

- Dunlop, C. A., E. Ongaro, and K. Baker. 2020. “Researching COVID-19: A Research Agenda for Public Policy and Administration Scholars.” Public Policy and Administration 35 (4): 365–383. https://doi.org/10.1177/0952076720939631

- Dzigbede, K. D., S. B. Gehl, and K. Willoughby. 2020. “Disaster Resiliency of US Local Governments: Insights to Strengthen Local Response and Recovery from the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Public Administration Review 80 (4): 634–643. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13249

- Eckstein, H. H. 1988. “A Culturalist Theory of Political Change.” American Political Science Review 82 (3): 789–804. https://doi.org/10.2307/1962491

- Elazar, D. J. 1987. Exploring federalism. Tuscaloosa and London: University of Alabama Press.

- Engler, S., P. Brunner, R. Loviat, T. Abou-Chadi, L. Leemann, A. Glaser, and D. Kübler. 2021. “Democracy in Times of the Pandemic: Explaining the Variation of COVID-19 Policies Across European Democracies.” West European Politics 44 (5-6): 1077–1102. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.1900669.

- Erk, J. 2007. Explaining Federalism: State, Society and Congruence in Austria, Belgium, Canada, Germany and Switzerland. London and New York: Routledge.

- Fafard, P., F. Rocher, and C. Côté. 2010. “The Presence (or Lack Thereof) of a Federal Culture in Canada: The Views of Canadians.” Regional & Federal Studies 20 (1): 19–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597560903174873

- Fischer, F. 2012. “Participatory Governance: From Theory to Practice.” In The Oxford Handbook of Governance, edited by D. Levi-Faur, 457–471. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gagnon, Alain-G. 2022. Legitimität und Diversität im Föderalismus: Eine Fallstudie am Beispiel Kanadas. Wien: New Academic Press.

- Gerber, M., A. Bächtiger, S. Shikano, S. Reber, and S. Rohr. 2018. “Deliberative Abilities and Influence in a Transnational Deliberative Poll (EuroPolis).” British Journal of Political Science 48 (4): 1093–1118. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123416000144

- Goelzhauser, G., and D. M. Konisky. 2020. “The State of American Federalism 2019–2020: Polarized and Punitive Intergovernmental Relations.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 50 (3): 311–343. https://doi.org/10.1093/publius/pjaa021

- Hainmueller, J., and D. J. Hopkins. 2015. “The Hidden American Immigration Consensus: A Conjoint Analysis of Attitudes Toward Immigrants.” American Journal of Political Science 59 (3): 529–548. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12138

- Hainmueller, J., D. J. Hopkins, and T. Yamamoto. 2014. “Causal Inference in Conjoint Analysis: Understanding Multidimensional Choices via Stated Preference Experiments.” Political Analysis 22 (1): 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpt024

- Harteveld, E. 2021. “Ticking all the Boxes? A Comparative Study of Social Sorting and Affective Polarization.” Electoral Studies 72: 102337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102337

- Hechter, M. 2013. Alien Rule. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hegele, Y., and J. Schnabel. 2021. “Federalism and the Management of the COVID-19 Crisis: Centralisation, Decentralisation and (non-) Coordination.” West European Politics 44 (5-6): 1052–1076. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.1873529

- Heinisch, R., E. Massetti, and O. Mazzoleni. 2018. “Populism and Ethno-Territorial Politics in European Multilevel Systems.” Comparative European Politics 16 (6): 923–936. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-018-0142-1

- Héritier, A. 2003. “Composite Democracy in Europe: The Role of Transparency and Access to Information.” Journal of European Public Policy 10 (5): 814–833. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350176032000124104

- Hooghe, L., and G. Marks. 2003. “Unraveling the Central State, but how? Types of Multilevel Governance.” American Political Science Review 97 (1): 233–243.

- Hooghe, L., and G. Marks. 2020. “A Postfunctionalist Theory of Multilevel Governance.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 22 (4): 820–826. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148120935303

- Hooghe, L., G. Marks, A. H. Schakel, S. C. Osterkatz, S. Niedzwiecki, and S. Shair-Rosenfield. 2016. Measuring Regional Authority: A Postfunctionalist Theory of Governance. Volume I. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

- Hopkins, D. J. 2015. “The Upside of Accents: Language, Intergroup Difference, and Attitudes Toward Immigration.” British Journal of Political Science 45 (3): 531–557. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123413000483

- Hu, Y. 2020. “Culture Marker Versus Authority Marker: How Do Language Attitudes Affect Political Trust?” Political Psychology 41 (4): 699–716. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12646

- Ingram, H., A. L. Schneider, and P. DeLeon. 2019. “Social Construction and Policy Design.” In Theories of the Policy Process, edited by Paul Sabatier, 93–126. New York: Routledge.

- Jaeger, P. T., and K. M. Thompson. 2003. “E-government Around the World: Lessons, Challenges, and Future Directions.” Government Information Quarterly 20 (4): 389–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2003.08.001

- Jedwab, J., and J. Kincaid, eds. 2019. Identities, Trust, and Cohesion in Federal Systems: Public Perspectives. Kingston ON: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- John, P., M. Sanders, and J. Wang. 2019. “A Panacea for Improving Citizen Behaviors? Introduction to the Symposium on the use of Social Norms in Public Administration.” Journal of Behavioral Public Administration 2 (2): 1–8. https://doi.org/10.30636/jbpa.22.119

- Juon, A. 2020. “Minorities Overlooked: Group-Based Power-Sharing and the Exclusion-Amid-Inclusion Dilemma.” International Political Science Review 41 (1): 89–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512119859206

- Kincaid, J., and R. L. Cole. 2011. “Citizen Attitudes Toward Issues of Federalism in Canada.” Mexico, and the United States. Publius: The Journal of Federalism 41 (1): 53–75. https://doi.org/10.1093/publius/pjq035

- Kriesi, H., B. Wernli, P. Sciarini, and G. Matteo. 1996. Le clivage linguistique: Problèmes de compréhension entre les communautés linguistiques en Suisse. Berne: Office fédéral de la statistique.

- Kuhn, T. 2019. “Grand Theories of European Integration Revisited: Does Identity Politics Shape the Course of European Integration?” Journal of European Public Policy 26 (8): 1213–1230. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1622588

- Laitin, D. D. 2000. “What Is a Language Community?” American Journal of Political Science 44 (1): 142–155. https://doi.org/10.2307/2669300

- Lane, D. S., C. M. Moxley, and C. McLeod. 2023. “The Group Roots of Social Media Politics: Social Sorting Predicts Perceptions of and Engagement in Politics on Social Media.” Communication Research 50 (7): 904–932.

- Lecours, André Daniel Béland, Alan Fenna, Tracy Beck Fenwick, Mireille Paquet, Philip Rocco, and Alex Waddan. 2021. Explaining Intergovernmental Conflict in the COVID-19 Crisis: The United States, Canada, and Australia.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 51 (4): 513–36. https://doi.org/10.1093/publius/pjab010

- Lee, T., and E. O. Pérez. 2014. “The Persistent Connection Between Language-of-Interview and Latino Political Opinion.” Political Behavior 36 (2): 401–425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-013-9229-1

- Leeper, T. J. 2020. cregg: Simple Conjoint Analyses and Visualization. R package version 0.3.6.

- Leeper, T. J., S. B. Hobolt, and J. Tilley. 2020. “Measuring Subgroup Preferences in Conjoint Experiments.” Political Analysis 28 (2): 207–221. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2019.30

- Levendusky, M. 2009. The Partisan Sort: How Liberals Became Democrats and Conservatives Became Republicans. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Liu, Z., J. Guo, W. Zhong, and T. Gui. 2021. “Multi-level Governance, Policy Coordination and Subnational Responses to COVID-19: Comparing China and the US.” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 23 (2): 204–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2021.1873703

- Livingston, W. A. 1952. “A Note on the Nature of Federalism.” Political Science Quarterly 67 (1): 81–95. https://doi.org/10.2307/2145299

- Maggetti, M., and P. Trein. 2019. “Multilevel Governance and Problem-Solving: Towards a Dynamic Theory of Multilevel Policy-Making?” Public Administration 97 (2): 355–369. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12573

- Maldonado, B. M. N., J. Collins, H. J. Blundell, and L. Singh. 2020. “Engaging the Vulnerable: A Rapid Review of Public Health Communication Aimed at Migrants During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Europe.” Journal of Migration and Health 1-2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmh.2020.100004

- Marks, G. 1993. “Structural Policy and Multilevel Governance in the EC.” In The State of the European Community. The Maastricht Debates and Beyond, edited by A. Cafruny, and G. Rosenthal, 391–410. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner and Harlow: Longman.

- Mason, L. 2015. “‘I Disrespectfully Agree’: The Differential Effects of Partisan Sorting on Social and Issue Polarization.” American Journal of Political Science 59 (1): 128–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12089.

- Mason, L. 2016. “A Cross-Cutting Calm: How Social Sorting Drives Affective Polarization.” Public Opinion Quarterly 80 (S1): 351–377. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfw001

- Mason, L. 2018. Uncivil Agreement: How Politics Became Our Identity. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- McLaren, L. 2005. Identity, Interests and Attitudes to European Integration. Houndsmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Michels, A. 2011. “Innovations in Democratic Governance: How Does Citizen Participation Contribute to a Better Democracy?” International Review of Administrative Sciences 77 (2): 275–293. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852311399851

- Miller, E. A., and J. Banaszak-Holl. 2005. “Cognitive and Normative Determinants of State Policymaking Behavior: Lessons from the Sociological Institutionalism.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 35 (2): 191–216. https://doi.org/10.1093/publius/pji008

- Mizrahi, S., E. Vigoda-Gadot, and N. Cohen. 2021. “How Well do They Manage a Crisis? The Government's Effectiveness During the Covid-19 Pandemic.” Public Administration Review 81 (6): 1120–1130. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13370

- Mueller, S. 2024. Shared Rule in Federal Theory and Practice: Concept, Causes, Consequences. Forthcoming with Oxford University Press.

- Mueller, S., and J. Bernauer. 2018. “Party Unity in Federal Disunity: Determinants of Decentralised Policy-Seeking in Switzerland.” West European Politics 41 (3): 565–593. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2017.1395254

- Mueller, S., and P. Dardanelli. 2014. “Langue, Culture Politique et Centralisation en Suisse.” Revue internationale de politique comparée 21 (4): 83–104. https://doi.org/10.3917/ripc.214.0083

- Mullin, M. 2021. “Learning from Local Government Research Partnerships in a Fragmented Political Setting.” Public Administration Review 81 (5): 978–982. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13395

- Murphy, J. R., and E. Arban. 2021. “Assessing the Performance of Australian Federalism in Responding to the Pandemic.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 51 (4): 627–649. https://doi.org/10.1093/publius/pjab026

- Ott, J. S., and P. Boonyarak. 2020. “Introduction to the Special Issue International Migration Policies, Practices, and Challenges Facing Governments.” International Journal of Public Administration 43 (2): 95–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2019.1672188

- Pérez, E. O. 2016. “Rolling off the Tongue Into the top-of-the-Head: Explaining Language Effects on Public Opinion.” Political Behavior 38 (3): 603–634. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-015-9329-1

- Pérez, E. O., and M. Tavits. 2019. “Language Influences Public Attitudes Toward Gender Equality.” Journal of Politics 81 (1): 81–93. https://doi.org/10.1086/700004

- Popelier, P. 2021. “Power-Sharing in Belgium: The Disintegrative Model.” In Power-Sharing in Europe: Past Practice, Present Cases, Future Directions, edited by Soeren Keil, and Allison McCulloch, 89–114. London: Palgrave.

- Porcher, S. 2021. “Culture and the Quality of Government.” Public Administration Review 81 (2): 333–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13106

- Rae, D. W., and M. Taylor. 1970. The Analysis of Political Cleavages. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Raney, T. 2010. “Quintessentially un-American? Comparing Public Opinion on National Identity in English Speaking Canada and the United States.” International Journal of Canadian Studies 42 (2): 105–123. https://doi.org/10.7202/1002174ar

- Reuchamps, M., J. Dodeigne, and J. Perrez. 2018. “Changing Your Political Mind: The Impact of a Metaphor on Citizens’ Representations and Preferences for Federalism.” Regional & Federal Studies 28 (2): 151–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2018.1433663

- Ricks, J. I. 2020. “The Effect of Language on Political Appeal: Results from a Survey Experiment in Thailand.” Political Behavior 42 (1): 83–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-018-9487-z

- Rothstein, B. 1996. “Political Institutions: An Overview.” In A New Handbook of Political Science, edited by R. E. Goodin, and H. D. Klingemann, 133–166. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

- Sabanadze, N. 2006. “Minorities and Kin States.” Helsinki Monitor 2006 (3): 244–56. https://doi.org/10.1163/157181406778141810

- Schildkraut, D. J. 2005. Press one for English: Language Policy, Public Opinion, and American Identity. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Schnabel, J., and Y. Hegele. 2021. “Explaining Intergovernmental Coordination During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Responses in Australia, Canada, Germany, and Switzerland.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 51 (4): 537–569. https://doi.org/10.1093/publius/pjab011

- Schuessler, J., and M. Freitag. 2020. Power Analysis for Conjoint Experiments. Working Paper. 1 September 2023. https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/9yuhp/.

- Seitz, W. 2014. Geschichte der politischen Gräben in der Schweiz. Zürich/Chur: Rüegger Verlag.

- Selway, J. S. 2011. “The Measurement of Cross-Cutting Cleavages and Other Multidimensional Cleavage Structures.” Political Analysis 19 (1): 48–65. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpq036

- Shair-Rosenfield, S., A. H. Schakel, S. Niedzwiecki, G. Marks, L. Hooghe, and S. Chapman-Osterkatz. 2021. “Language Difference and Regional Authority.” Regional & Federal Studies 31 (1): 73–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2020.1831476

- Shen, Q., and X. Gao. 2019. “Multilingualism and Policy Making in Greater China: Ideological and Implementational Spaces.” Language Policy 18 (1): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10993-018-9473-7

- Stamati, T., T. Papadopoulos, and D. Anagnostopoulos. 2015. “Social Media for Openness and Accountability in the Public Sector: Cases in the Greek Context.” Government Information Quarterly 32 (1): 12–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2014.11.004

- StatCan. 2021. Statistics Canada: Canada’s national statistical agency. 29 December 2021. https://www.statcan.gc.ca-/eng/start.

- Steytler, Nico, ed. 2022. Comparative Federalism and Covid-19: Combating the Pandemic. London: Routledge.

- Strebel, M. A., D. Kübler, and F. Marcinkowski. 2019. “The Importance of Input and Output Legitimacy in Democratic Governance: Evidence from a Population-Based Survey Experiment in Four West European Countries.” European Journal of Political Research 58 (2): 488–513. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12293

- Swenden, W., M. Brans, and L. De Winter. 2006. “The Politics of Belgium: Institutions and Policy Under Bipolar and Centrifugal Federalism.” West European Politics 29 (5): 863–873. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380600968729

- Terwel, B. W., F. Harinck, N. Ellemers, and D. D. Daamen. 2010. “Voice in Political Decision-Making: The Effect of Group Voice on Perceived Trustworthiness of Decision Makers and Subsequent Acceptance of Decisions.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied 16 (2): 173. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019977

- Toshkov, D. 2011. “Public Opinion and Policy Output in the European Union: A Lost Relationship.” European Union Politics 12 (2): 169–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116510395043

- Vasilopoulou, S., and M. Wagner. 2017. “Fear, Anger and Enthusiasm About the European Union: Effects of Emotional Reactions on Public Preferences Towards European Integration.” European Union Politics 18 (3): 382–405. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116517698048

- Vinopal, K. 2020. “Socioeconomic Representation: Expanding the Theory of Representative Bureaucracy.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 30 (2): 187–201. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muz024

- Von der Weid, N., R. Bernhard, and F. Jeannaret. 2002. Bausteine zum Brückenschlag zwischen Deutsch- und Welschschweiz / Eléments pour un trait d’union entre la Suisse alémanique et la Suisse romande. Biel/Bienne: Editions Libertas Suisse.