ABSTRACT

This article analyzes how autocratic parties sustain and adjust electoral manipulative tactics to maintain electoral dominance in multi-level elections. It examines continuities and changes in electoral authoritarianism in Ethiopia by comparing elections held under the EPRDF and Prosperity Party (PP). The 2021 elections, marred by the detention of main opposition leaders, war and opposition boycotts, resulted in a dominant victory for the incumbent (PP), showing continuity of electoral dominance. Analysis of election data since 1995 shows that elections under PP were more competitive than the last two elections under the EPRDF in terms of opposition votes and seat share. Further, the analysis indicates regional asymmetry in electoral competition and opposition success, which is explained by asymmetric authoritarianism, ethnonationalism, and regional political dynamics. Despite this, the incumbent garnered public support through targeted rhetoric, addressing regional demands, and reframing historical narratives. These dynamics have implications for Ethiopia’s future and state-society relations. Insights from Ethiopia have implications for multi-ethnic federations facing challenges of democratization while highlighting the empirical need for a nuanced understanding of region-specific contexts to understand democratization challenges in ethnically diverse states.

Introduction

In a democracy, elections are the fundamental means of obtaining legitimacy and consent to govern. Nevertheless, the occurrence of elections within authoritarian regimes, coupled with the potential for manipulative practices, prompts scrutiny regarding the appropriateness of employing elections as the exclusive criterion for classifying regimes as democratic. Scholars suggested that assessing the quality of elections is more appropriate for classifying regimes (Bogaards Citation2009; Diamond Citation2002; Levitsky and Way Citation2002; Levitsky and Way Citation2010; Miller Citation2012). Studies have compared regimes’ durability and likelihood of democratization (Brownlee Citation2009; Bunce and Wolchik Citation2009; Gandhi and Przeworski Citation2007). Yet, a notable gap in our understanding is how distinct dominant parties within the same state sustain or modify subnational authoritarianism. This knowledge gap gains significance considering political transitions in various countries that removed long-serving authoritarian leaders through revolution and protest. While some nations successfully transitioned to democracy, others lingered in electoral autocracy. Notably, post-2011 Arab Spring, African countries, including Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Sudan, and Tunisia, experienced political changes. However, only Tunisia managed to establish a viable democratic system, although its fragility persists due to challenges in the economic sphere (Dunne Citation2020, 183). Ethiopia also experienced leadership change in 2018 following pro-democracy protests, making it a critical case for examining whether and how successor parties preserve and modify subnational authoritarianism using multi-level elections.

Research on Ethiopia highlights the absence of free and fair elections under the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), except the 2005 competitive elections that culminated in post-election violence (Arriola and Lyons Citation2016; Ayele Citation2018; Lyons Citation1996; Pausewang and Tronvoll Citation2000; Tronvoll Citation2009). In 2018, the new leadership conducted reforms, dissolved the EPRDF and established a new party, Prosperity Party (PP) in 2019. Subsequently, Ethiopia conducted elections in 2021 under the umbrella of PP. Notably, there is a research gap in comparing multi-level polls conducted under the auspices of these two dominant parties. While Lyons and Verjee’s (Citation2022) early research on three regions takes a step in this direction, its limited scope constrains the ability to make generalizations and offer comprehensive insights into temporal changes. To gain a thorough understanding of the dynamics of authoritarianism in multi-level elections, a broader research approach is necessary. This expanded research can facilitate a more robust analysis of how dominant parties sustain and/or alter subnational authoritarianism through multi-level elections.

This article fills this vital gap by providing a thorough comparative analysis of the dynamics of electoral authoritarianism under the EPRDF and PP. The article encompasses all regions, both federal and regional elections and data since 1995. The analysis explores the electoral dominance tactics employed by successive incumbents, aiming to understand how authoritarian practices persist, evolve, and influence electoral outcomes. The article makes two primary contributions. (1) it analyzes how autocratic parties sustain and adjust electoral manipulative tactics to maintain electoral dominance in multi-level elections in a multi-ethnic federation. (2) it explains the primary factors generating asymmetric subnational authoritarianism in multi-level elections in an ethnically diverse federation. Generally, the article seeks to enhance our understanding of authoritarian dynamics within multi-level elections, filling a crucial void in scholarly discourse.

The Ethiopian political landscape has undergone significant transformation over the past few years. Previously, the country was governed by the EPRDF, a coalition of regional parties, for nearly three decades until the party was dissolved and replaced by the PP in 2019. While the EPRDF came to power through insurgency, PP emerged as a civilian party following years of protests. During the EPRDF era, Ethiopia operated under a system where each region had its own ruling party. In contrast, under PP, regional incumbent parties, except the Tigray Peoples Liberation Front (TPLF), were amalgamated to form a nationalized Prosperity Party. Noteworthy differences also existed in the representation within the government. During the EPRDF era, key federal posts were dominated by the TPLF officials, representing a constituency that comprised about 6% of Ethiopia’s population. Conversely, PP reflects influence from larger ethnic groups, such as the Oromo (38%) and Amhara (27%), collectively comprising the majority. After the 2018 political shift in Ethiopia, power has been consolidated under Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, an Oromo, the largest ethnic group in the country. This shift highlights substantial changes in Ethiopia’s political landscape and power structure.

The formation of PP marked a departure from the EPRDF through several distinctive features. The main changes are the inclusion of former affiliate parties, the establishment of a national party structure replacing the EPRDF’s regionalized approach, the adoption of the ‘medemer’ ideology instead of the EPRDF’s ‘revolutionary democracy’, and the formal registration of PP as a new political entity. Despite these changes, a significant continuity in personnel, with all members and most leaders of the EPRDF, including the Prime Minister, transitioning to PP, defines the party as an evolutionary rather than a revolutionary shift.

The article argues that this continuity in personnel has contributed to the persistence of similar manipulative strategies and election outcomes. Historical legacies and inherited institutions further play pivotal roles in sustaining these tactics. While PP has retained the EPRDF’s tactics of harassing, detaining and eliminating political adversaries, it has also introduced innovative approaches of addressing regionalized demands, utilizing segmented political rhetoric, and reframing historical narratives to expand its support base. However, the shift in power locus, changes in regional politics, and ethnonationalism have resulted in asymmetric subnational electoral authoritarianism and varying degrees of opposition success. The regional asymmetry in electoral authoritarianism reveals the unequal treatment of opposition in different regions, with significant implications for the legitimacy of Ethiopia’s democratic process, the country’s future trajectory, and the dynamics of state-society relations.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows: It begins with theoretical discussions on electoral authoritarianism in multi-level states. It then presents methods and an analytical framework. After that, the article critically analyzes the elections under the EPRDF and PP, focusing on manipulation tactics and electoral outcomes. This is followed by analyses of continuities and changes in electoral manipulation tactics under the two parties. Subsequently, the article explores asymmetric electoral authoritarianism in Ethiopia. Finally, the article concludes with a summary of key findings and their implications.

Theoretical overview of multi-level elections under authoritarian regimes

This article leverages the electoral authoritarianism literature to construct an analytical framework for systematically analyzing data and uncovering changes, patterns, and trends in Ethiopia’s electoral environment. It starts by identifying the characteristics of electoral authoritarian regimes. Electoral authoritarian regimes employ manipulative tactics to maintain their grip on power despite formal democratic institutions (Levitsky and Way Citation2002, 52; Miller Citation2012, 153). Media censorship, harassment of the opposition, gerrymandering, vote-buying, and fraud are among the strategies they use to reduce competition and eliminate opposition (Donno Citation2013, 704; Levitsky and Way Citation2002, 56; Schakel and Romanova Citation2022; Schedler Citation2010b). These manipulation techniques are used by both national and subnational governments that want to demonstrate loyalty to the central authority (Schedler Citation2010a, 70). Since Ethiopia is a federal state with a multi-level government, it is vital to accurately assess the national and subnational-level political context to analyze electoral authoritarianism in the country.

Another theoretical perspective guiding this article’s analysis pertains to the literature about variations among authoritarian regimes. For example, Howard and Roessler (Citation2006, 366–369) distinguish authoritarian regimes into closed authoritarian, hegemonic authoritarian, and competitive authoritarian. Under closed authoritarian regimes, elections are irrelevant to seize power as oppositions, free media, and civil society are not allowed, and political management is sustained through subjugation. Under hegemonic authoritarian regimes, the incumbent is the sole competitor, while the opposition is denied access to state media and restricted from holding political gatherings. Rights are violated, and incumbents typically secure victory by large margins (more than 70 percent of votes or seats), resulting in a de facto one-party system (Donno Citation2013; Howard and Roessler Citation2006). In contrast, competitive authoritarian regimes hold regular and seemingly competitive elections. However, incumbents manipulate the electoral process to favor themselves and discourage opposition support (Levitsky and Way Citation2002, 53). As opposition parties pose electoral challenges to the incumbent, a competitive authoritarian regime wants overwhelming victory to project invincibility and discourage defections and opposition support (Donno Citation2013; Simpser Citation2013).

This article employs Howard and Roessler’s (Citation2006, 366–369) authoritarianism classification to create a typology of elections under the EPRDF and PP. Closed authoritarianism does not characterize Ethiopia because the country regularly holds elections and political parties operate. The country conducted six elections since 1995. However, whether elections under PP are more competitive than elections under the EPRDF remains unclear. Further, there is a knowledge gap regarding whether these two parties can be categorized into distinct types of authoritarianism. This is because different ruling parties can use different manipulation tactics depending on the conditions either encourage or limit the utilization of specific electoral domination mechanisms (Magaloni Citation2006, 15–24; Greene Citation2011). This means some elections under authoritarian regimes can yield relatively less authoritarian governments than their predecessors, as witnessed in countries such as Indonesia, Peru, and Romania (Howard and Roessler Citation2006). The ruling PP comprises the EPRDF’s reformist officials who ascended to power with the support of pro-democracy social movements.

Hence:

H1a: Other things being equal, as PP leaders are reformists who came to power following pro-democracy protests, elections under the PP will have to be more competitive than elections under the EPRDF.

H1b: Nevertheless, as the PP inherited the EPRDF’s party members, leaders, and decision-making norms, the PP will also have sustained the EPRDF’s authoritarian style.

Therefore, with its ethnic diversity, Ethiopia will likely exhibit asymmetric subnational authoritarianism. Additionally, given Oromia’s political importance as the PM’s constituency and its significant representation in the federal parliament (32.5%), the incumbent is expected to be more repressive than other regions. Regions with diverse territorial ethnic groups, like SNNP (55 ethnic groups), will likely see opposition success as ethnic parties can mobilize support based on ethnic affiliations, especially when competing against the nationalized PP.

Hence:

H2a: Given its ethnic diversity, Ethiopia will have experienced subnational regime variation.

H2b: Other things being equal, core regions (such as Oromia) and regions with strong opposition (such as Oromia and Somali) will have experienced authoritarian subnational elections.

H2c: Other things being equal, ethnically diverse regions will have experienced relatively competitive elections.

Methods and analytical framework

The article used qualitative and quantitative comparative methods to examine the strategies of electoral dominance employed by the EPRDF and PP and identify patterns of change and continuity. Academic sources, news articles, and reports from different organizations were the main qualitative data sources. Quantitative indicators were computed from official election data from 1995 to 2021. Quantitative data includes voter turnout, incumbent and opposition vote shares, parties’ seat shares, the number of contested parties, the proportion of contested seats, and the party-seat ratio. The official election data were mostly computed from the National Electoral Board of Ethiopia (NEBE) reports. Additionally, I gathered data on voter turnout from the International IDEA (Citation2024) database. This step was considered essential due to the potential unreliability of official data, given the authoritarian regimes’ propensity to inflate turnout figures for legitimacy. Nevertheless, there were few cases of minor discrepancies between official data and hardly found data from other sources. While some of the data are available on NEBE’s website (https://nebe.org.et/en), others were generated from NEBE (Citation1995, Citation2000, Citation2005, Citation2010 and Citation2015) reports. These data are synthesized and presented in tables and charts to facilitate comparison.

The data served as the basis for comparative analyses of elections under the two parties, focusing on key variables such as levels of electoral contestation, voter turnout, incumbents’ votes and seat share, contested seats, the number of contested parties, and party-seat ratio. Furthermore, a correlation test was conducted to analyze the association between variables such as regional ethnic diversity and opposition success, regional ethnic diversity and incumbent vote share, and ethnic diversity and the number of contested parties. This analysis examines the nexus between regional ethnic diversity and subnational authoritarianism or opposition success. Furthermore, quantitative analyses were conducted to identify asymmetric subnational authoritarianism and elucidate the underlying causal factors. The integration of qualitative and quantitative analyses facilitated a comparative evaluation of the electoral dominance strategies utilized by the two parties. It also allowed an examination of whether and how these strategies were sustained and/or modified.

To address H1a and H1b, the article critically examines elections conducted under the EPRDF and PP. This involves a detailed analysis of manipulation tactics and electoral outcomes. I used quantitative data to compare elections under the two parties and categorize them according to Howard and Roessler's (Citation2006, 366–369) regime classification. According to Howard and Roessler (Citation2006), the key criteria for classifying elections into hegemonic and competitive categories include (1) the presence of elections, (2) the competitiveness of the elections, (3) the fairness of the elections, and (4) whether the incumbents received above 70 percent of the vote. Moreover, I employed election data to make comparisons across variables such as voter turnout, incumbents’ seat share, and the number of contested parties. Combining both qualitative analyses of manipulation tactics and quantitive assessments of election outcomes under the two parties helped me analyze whether and how authoritarian tactics are sustained or modified by two different parties.

H2a is examined using quantitative indicators, including opposition-won seats and a V-Dem (Citation2023) dataset that measures subnational election unevenness. Additionally, qualitative analyses are employed to assess the extent of opposition repression across regions. H2b is addressed through qualitative analysis of secondary data to examine the extent to which main oppositions, particularly formerly banned parties, were allowed to participate freely in elections. Quantitative data, encompassing the percentage of contested seats, the incumbent's seat and vote share, and the party-seat ratio, are also analyzed. Finally, H2c is explored by examining whether opposition success is higher in regions characterized by diverse territorial groups compared to other regions. I computed the percentage of contested seats, the party-seat ratio, and the incumbent’s seat and vote share to analyze regional variation in electoral competitiveness. A greater percentage of contested seats indicates a more competitive election in the region, while a higher party-seat ratio suggests a lower level of competition. A higher incumbent's vote and seat share corresponds to increased electoral dominance. Moreover, a qualitative analysis of secondary sources was undertaken to elucidate the factors contributing to the variation in subnational authoritarianism or opposition success.

Elections under EPRDF and PP: manipulation tactics and electoral outcomes

The post-Derg era in Ethiopia witnessed a significant political transformation. In 1991, the EPRDF assumed power and implemented federalism through the 1991 Transitional Period Charter (TGE Citation1991). During the transition period (1991-1994), the EPRDF pursued a two-fold agenda. While publicly endorsing democratization and decentralization, it retained a firm hold on power and suppressed opposition parties, often pushing main oppositions, including the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF), to boycott the election (Gudina Citation2011, 668; Lyons Citation1996, 125–126). This early sign raised doubts about the EPRDF’s dedication to Ethiopia’s democratic transition, power-sharing, and inclusive governance. The inaugural federal election held in 1995 was envisioned as a pivotal moment marking the democratic culmination of the transitional period. However, a critical examination of the election results reveal that the EPRDF limited the political space by forcing the major opposition to boycotts (Lyons Citation1996; Samatar Citation2004, 1134). The tightening of political space had significant ramifications in creating a foundation for authoritarianism in Ethiopia. Viewed through the lens of Howard and Roessler (Citation2006, 366–369), the presence of 47 parties suggests that the 1995 elections do not conform to the characteristics of closed authoritarianism. However, the fact that the incumbent secured 82.87% of votes and 99.5% of seats () means the 1995 election aligns with Howard and Roessler's (Citation2006, 366–369) classification of hegemonic authoritarianism.

Table 2. Typology of elections.

In the 2000 election, there was a limited resurgence of opposition participation. However, their presence failed to present a substantive challenge to the EPRDF, except for one district in the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ (SNNP) region (Tronvoll Citation2001). While there were relatively favorable campaigning conditions in Addis Ababa, opposition in rural areas faced a restricted political environment and targeted intimidation, often perpetuated by local cadres. Further, region-specific manipulation tactics were deployed. According to Pausewang and Tronvoll (Citation2000), the EPRDF strategically used the distribution of relief aid in the SNNP region to influence voters to support the ruling party. Such incidents reveal the continuity of election manipulations to favor the incumbent. In this context, the EPRDF and its affiliated parties secured 95.1% of votes and 95% of seats in the HPR (see and online supplemental data A), sustaining the party’s hegemonic authoritarianims.

The 2005 parliamentary elections were highly contested. Campaigns and polling were relatively fair and free, generating widespread hope for democratization (Arriola and Lyons Citation2016, 77). Remarkably, opposition parties demonstrated substantial strength, nearly securing one-third of the seats in the federal parliament. In this context, the ruling EPRDF and its affiliated parties secured 373 out of 547 seats in the HPR, while the opposition parties secured 172 seats (Tronvoll Citation2009). The opposition won significant seats in the Addis Ababa council and regional councils, including 107 out of 294 in the Amhara region and 148 out of 537 in Oromia. Overall, the opposition mobilized strong support in Amhara, Oromia, SNNP regions, and Addis Ababa, sweeping all 23 HPR seats (Lyons Citation2010), indicating strong opposition support in those constituencies. Analyzing the 2005 election through Howard and Roessler's (Citation2006) authoritarianism typology, the competitiveness of the election and the EPRDF's winning only 62.65% of votes and 68% of seats () indicate the party's shift from hegemonic to competitive authoritarianism.

The opposition claimed they won the majority, while the incumbent denied it, plunging the country into political deadlock and instability. As Abbink (Citation2006) noted, faced with peaceful protests, the government responded violently. This brutal crackdown on protestors was followed by the arrest of opposition leaders and the persistent emergence of social unrest. The 2005 Ethiopian elections marked a critical moment when the opposition successfully harnessed the opportunities afforded to them, resulting in a notable expansion of their political presence across multiple regions. The high level of support they garnered in Amhara, Oromia, SNNP, and Addis Ababa reflected regionally asymmetrical opposition success. This election showed potential for a more pluralistic political landscape. It served as a warning to the incumbent of the oppositions’ capabilities when elections are conducted freely.

The ruling EPRDF party was caught off guard by the opposition’s ability to mobilize voters during the 2005 national polls. As Aalen and Tronvoll (Citation2009, 194) note, the party employed a ‘carrot-and-stick’ approach to prevent this from happening again. It used microcredit programs to attract young members and pressure government employees to join the party’s ranks, increasing its members from less than a million in 2005 to a staggering 4 million by 2008. It also implemented repressive measures and tightened its control structure from the top. As Abbink (Citation2009, 11) underscored, the aftermath of the 2005 election ‘‘was a turning point, away from the path of democracy, and full-blown monopolistic power was reinstated by the ruling party’’. Post-2005, the EPRDF strategically employed patronage to expand its support base while simultaneously cracking down on opposition, thus influencing the trajectory of Ethiopian politics in the following years.

The 2010 Ethiopian elections reaffirmed the EPRDF’s pre-2005 hegemonic status. It secured an overwhelming 94.6% of votes and 99.6 percent of the seats in the federal parliament (). Regional results mirrored this pattern, as the EPRDF controlled all regional seats (1903) except one in Benishangul-Gumuz (Tronvoll Citation2010, 130). Despite a peaceful polling process, opposition candidates experienced arrests, and incidents of violence disrupted the campaign period, creating a sense of fear and insecurity among the population. The European Union observer mission concluded that insufficient measures were taken to ensure a campaign environment free from threats and intimidation (EU Citation2010). In the subsequent 2015 elections, the EPRDF further solidified its hegemony by securing all federal and regional seats and 94.9% of the popular vote. This result turned Ethiopia into a de facto one-party state. The consolidation of power by the EPRDF has led to Ethiopia being categorized as an authoritarian regime, as reflected in The Economist’s 2017 Democracy Index (Freedom House Citation2018).

The early elections under the EPRDF demonstrated a trend of shrinking political space and marginalization of opposition, with the ruling EPRDF building hegemonic authoritarianism. The 2005 election, marked by robust opposition and competitive polling, represented a missed opportunity for transforming the regime into a competitive authoritarian system. The subsequent elections in 2010 and 2015 reaffirmed the ruling party’s hegemonic authoritarianism. The ruling party’s strategic adjustments, employing both incentives and coercive measures, enabled it to mitigate opposition mobilization and monopolize power. The elections under the EPRDF show a recurring pattern. When occasional moments of opposition strength and public mobilization emerged, they were met with resistance, repression, and a consolidation of power by the ruling party.

The EPRDF monopoly of federal and regional seats in the 2015 elections was followed by years of protests in Oromia and Amhara. Subsequently, PM Hailemariam Dessalegn resigned, and Abiy Ahmed came to power in 2018. Abiy conducted reforms, including repealing repressive laws and opening up political spaces, which brought hopes of a democratic transition. Despite these initial positive developments, the decision of the House of Federation (HoF) to postpone the 2020 election due to COVID-19 became controversial and consequential. Main opposition parties rejected this decision, accusing the government of attempting to extend its term in office. Consequently, a crackdown on opposition parties ensued (DW Citation2020). Adding to the complexity, the Tigray region defied the HoF’s decision and conducted a regional election in September 2020 (The Reporter Citation2020). While the federal government declared the Tigray election invalid, the Tigray region claimed that the federal government was illegitimate as its terms had expired (France24 Citation2020). Disagreement between Tigray and the federal government had already started in 2019 when due to the dissolution of the EPRDF against the TPLF’s interest in 2019 (Yimenu Citation2022b, 11). Tigray’s regional elections sparked tensions and retaliations, leading to the Tigray war (BBC Citation2020). The complexities of the Tigray conflict and election are beyond this article’s scope.

Under such instability and fragile situation, the polls were held after one year of delay in 2021. Main oppositions, such as the OLF, Oromo Federalist Congress (OFC), and Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF), boycotted (BBC Citation2021). The elections were held at different times due to security and logistic issues, making a one-day election impossible. The election’s first round was conducted on 21 June 2021 in 436 of the 547 HPR constituencies. Polls did not open in 102 constituencies in Tigray, Somali, Harari, Afar, SNNP, and Benishangul-Gumuz regions, representing about 18 percent of the 547 parliamentary seats (HRW Citation2022). The second round of votes was conducted in September 2021 for 47 federal and 375 regional seats in the Somali region, where registration carelessness deferred voting; in Harari, where registration issues and a legal dispute triggered delays; and in 12 constituencies in the SNNP, where ballot and security issues delayed polls (Reuters Citation2021a). Due to insecurity, voting did not occur in all 38 parliamentary constituencies in Tigray, parts of the Oromia, Amhara, Afar, and Benishangul-Gumuz regions (HRW Citation2022). The inability to conduct elections in some constituencies has repercussions on democratic participation and representation, while key opposition boycotts undermine the incumbent’s legitimacy.

In the 2021 elections, national voter turnout was 93.64, the highest after the 1995 founding elections. In contrast, the voting age population (VAP) turnout was 63.37, the lowest since 2000 (online supplemental data A). Regionally, voter turnout was 88%. Benishangul-Gumuz had the lowest participation, mainly due to security concerns, while turnout was relatively higher in Afar and Oromia. Notwithstanding scattered opposition victories in some regions, the PP lost only 15 federal seats. EZEMA, GPDO, and KPDP secured 7 seats in the SNNP region. Similarly, NAMA secured 5 seats in the Amhara region, while independents took 3 federal seats in Oromia. In the regional assemblies, 6 opposition parties secured 40 seats in Amhara, SNNP, Gambella, and Afar (). Despite pockets of opposition strength, the ruling PP maintained a firm grip on all regional parliament seats in other areas. Overall, the party won 96.8% of federal and 98% of regional parliament seats (Supplemental Data C). This result indicates that, like the EPRDF, PP also exhibits the characteristics of a hegemonic authoritarian party according to Howard and Roessler's (Citation2006) categorization. The analysis partially supports hypothesis H1a, which suggests that elections under the PP will have to be more competitive than those under the EPRDF. While elections under PP were more competitive than the last two elections under the EPRDF, they were significantly less competitive than the 2005 election.

Table 1. The 2021 federal and regional election results.

summarizes elections under the two parties and categorizes them according to Howard and Roessler's (Citation2006, 366–369) regime classification criteria (see methods section). All elections under the EPRDF, except the 2005, are characterized as hegemonic. Similarly, the sole polls held under PP are classified as hegemonic. Notwithstanding, there is a notable decline in both the incumbent's seat and vote share under PP (). Considering factors such as the 2021 elections occurring under an incomplete transition from an authoritarian party, the prevailing political and security dynamics, and the transfer of the EPRDF officials into PP, it is early to conclude that the party has firmly established hegemonic control. The subsequent two figures depict the regional breakdown of election data under the two parties for the years 2015 and 2021. The data help us classify the subnational elections as hegemonic or competitive using the same criteria used above.

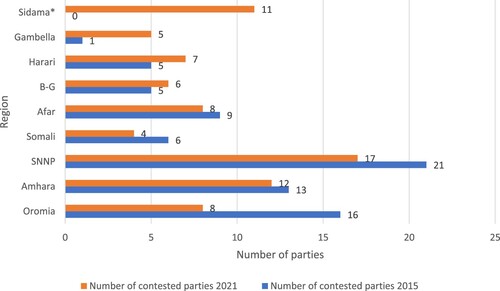

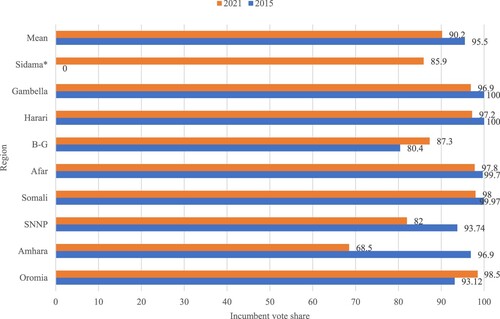

Compared to the 2015 elections, the number of parties contested significantly declined in Oromia and SNNP (). However, the 2021 electoral outcomes illustrate better opposition performance than the last elections under the EPRDF, both in opposition votes and seat share. Elections under PP were more competitive, with opposition members and independent candidates securing 15 federal and 40 regional seats (). Further, the decline in the incumbents’ vote share highlights the relatively competitive nature of the elections under PP (). The incumbent’s vote share varies among regions. In Amhara, the incumbent could get only 68.5% of votes, enabling the region to be categorized as competitive hegemonic according to Howard and Roessler's (Citation2006, 366–369) typology. This emerging opposition presence in a few regions indicates a potential shift in Ethiopia’s political landscape. Later in this article, a detailed analysis of such regionally asymmetric outcomes and explanatory factors is made.

Continuities and changes of electoral manipulation tactics under two parties

Continuities of the EPRDF’s tactics

The transition from the EPRDF to PP demonstrated the continuity of repressive tactics against opposition parties. Despite initial optimism when Abiy came to leadership, the NEBE’s initial postponement of elections from May 2020 to August due to lack of preparedness and later, indefinite postponement of the election, arguably due to the Covid pandemic was criticized by opposition parties such as OLF, ONLF, and OFC, who raised concerns about transparency and the potential for indefinite postponement (Addis Standard Citation2020). The ruling party accused the opposition of a power grab, while the opposition called for a coalition government (Quartz Citation2020).

Such rhetoric hostilities led to an intimidating campaign against the opposition. Following the assassination of iconic Oromo artist Hachalu Hundessa in June 2020, several opposition leaders were arrested, prompting human rights groups to express concerns that Ethiopian authorities had ‘not moved on from past practices of arresting first and investigating later’ (HRW Citation2020). Tiruneh Gamta, the OFC’s chief of office, explained that the ruling party had severed communication with its members, supporters, and the public and prevented opposition candidates from campaigning (DW Citation2021). Opposition candidates could not register for the election or campaign because their leaders were jailed, candidates were beleaguered, and their offices were raided (BBC Citation2021). Consequently, OLF and OFC withdrew from the election, replicating a similar scenario during the early period when the EPRDF came to power in the 1990s. This left the incumbent as the sole candidate on the ballot in the Oromia region, the country’s largest constituency (HRW Citation2021).

The transition from the EPRDF to PP demonstrated continuity in pursuing political dominance. Like the EPRDF, PP took advantage of the transitional period to consolidate its power and neutralize major opposition. Prosperity Party aimed to ensure its control and eliminate potential challengers by controlling electoral processes and suppressing dissent. This highlights the consistent pattern of leveraging transitional periods to strengthen political dominance in Ethiopian politics.

The government cited charges against the detained opposition leaders, reminiscent of the EPRDF era, where opposition figures were imprisoned under draconian and repressive laws. This suggests the continuity of employing accusations as a pretext to exclude the opposition from elections. The subsequent release of the detained leaders months after the election further substantiates the politically motivated nature of their detention (DW Citation2021). Like the EPRDF era, harassing opposition was widespread. Aljazeera’s (Citation2021) election coverage reported that over 200 instances of harassment, including observers being expelled or denied access, were reported by just one party. The perpetuation of EPRDF’s authoritarian style casts a shadow on the fairness of the election process. Notably, credible observers were absent, as major groups like the European Union chose not to send observer teams as they doubted the possibility of conducting free and fair elections (Reuters Citation2021b), similar to the situation observed during the EPRDF era. The retention of many former EPRDF officials within the ranks of the PP, coupled with factors such as historical legacies and inherited institutions, has led to a continuity in personnel, which in turn has contributed to the persistence of similar manipulative strategies and election outcomes. This analysis supports the H1b hypothesis, which anticipated the continuation of the authoritarian style established by the EPRDF to PP due to the retention of the EPRDF party members, leaders, and decision-making norms.

PP’s innovative electoral dominance strategies

The ruling PP not only continued EPRDF’s legacy but also adopted the following new strategies to garner genuine public support and ensure electoral dominance.

Segmented political tactics and reframing historical narratives

Abiy’s popularity played a significant role in the success of his party. As Dube (Citation2020) underscores, his rhetoric of rejecting ethnic oppression and promoting national unity resonated with pan-Ethiopian and Amhara communities. While this rhetoric of Ethiopian unity attracted substantial support, PP also adopted segmented electoral campaigning and political tactics, which differed from EPRDF’s approach of a uniform ‘Revolutionary Democracy’ ideology across the country. PP gained support from nationalist Amharas by acknowledging their claim over contested territory in Western Tigray and promising to address the issue constitutionally (John Citation2021, 1017–1018). While presenting itself rhetorically as unitarist, PP actively promoted federalism by addressing the demands for autonomy from diverse ethnic groups (as discussed later in detail). While this approach of ‘talking unitarist and walking federalist’ may indicate pragmatism in appealing to different constituencies, it may also suggest a lack of a well-defined and robust ideological foundation.

In Oromia, PP adopted a tactic of reframing historical narratives regarding Oromos’ marginalization and their role in the Ethiopian political economy. This reframing asserts that the Oromo has been a key player in Ethiopian state-building and that the country’s fate is in its hands. To fulfil this crucial responsibility, the party touted that the Oromo must support PP, which is founded on the principle of unity rooted in the Gada system – an indigenous governance system of the Oromo nation. The party dropped EPRDF’s ‘revolutionary democracy’ ideology by adopting Medemer, meaning joining or synergy, written by Abiy Ahmed himself. Abiy’s Oromo identity has also generated a sense of victory among his people. As Lyons and Verjee (Citation2022, 344) note, a PP official in Oromia has stated that Medemer is derived from the Oromo Gada system’s unity and that Abiy, who grew up under the Gada system, is the right leader. Given the sacrifices made by the Oromo people to bring Abiy to power (Forsén and Tronvoll Citation2021; Kelecha Citation2021), it is understandable that Oromo has a strong reason to support PP.

Opening up central politics to formerly marginalized regions

The Prosperity Party took a new approach towards the lowland regions. Unlike the EPRDF era, where lowland region parties were confined to peripheral partners with limited influence on the national stage (Yimenu Citation2022b), PP opened up central power to previously marginalized ruling parties of the lowland regions of Afar, Benishangul-Gumuz, Gambella, and Somali to join the federal ruling party. PP has addressed historical grievances and demands for greater inclusion by doing so. This strategic maneuver serves two purposes. Firstly, it allows officials from these regions to assume important positions and actively participate in federal decision-making. For instance, Aden Farah, an official from the Somali region, became PP’s deputy president, exemplifying the tangible impact of this approach. After Aden was elected as deputy president, the Somali region president, Mustafa Omer stated:

‘The Somali people in Ethiopia have today lived to see their son elected as the deputy president of the ruling Prosperity Party. Unthinkable just years back when Somalis were branded unfit to comprehend “revolutionary democracy”! Congratulations brother Adan Farah. We are at the center!’. (SD News Citation2022)

Addressing autonomy demands

The PP’s departure from the EPRDF’s approach is evident in its willingness to allow referendums to create new regions in contrast to the EPRDF, which violently suppressed ethnic demands for separate regions (Yimenu Citation2022b). Though PP initially attempted to suppress and delay (Tronvoll Citation2021), by eventually permitting a referendum for the Sidama zone to become an independent region, PP garnered significant support (Lyons and Verjee Citation2022). Further, incorporating the Sidama Liberation Movement (SLM), a party synonymous with Sidama nationalism, into PP has helped the incumbent secure a 100% victory in Sidama. PP’s commitment to considering the formation of additional regions from the SNNP region and offering a referendum for the South West Ethiopia Peoples region has likely garnered support from ethnic groups like Kambata, Wolaita, Hadiya, and Gamo. Granting regional status to these groups, which have decades-long aspirations for autonomy, has contributed to PP’s increased support from diverse communities. This approach has led to the creation of three new regions within four years, a notable departure from the EPRDF’s 27-year rule without any increase in regional divisions. This transformative shift underscores PP’s efforts to address ethnic aspirations for self-governance and consolidate its political base. Nevertheless, the process of addressing demands for regional status has faced contention. For instance, ethnic zones like Gurage expressed dissatisfaction over the suppression and manipulation of their referendum requests.

Coopting less-threatening opposition

Another invention of the PP is coopting less-threatening opposition parties. Following the power-sharing promise Abiy made during his public speeches, some opposition parties’ election campaigns and discourse tone changed from ‘we should win and take power’ to ‘priority to our country’. For example, while key oppositions such as OLF, OFC, and ONLF opposed delaying elections and demanded a transitional government if elections were postponed (Addis Standard Citation2020), EZEMA and NAMA supported election delay. EZEMA stated, ‘We are strongly against the proposition of forming a transitional government as a way out to the standstill’ (EZEMA Citation2020). Following the elections, PP appointed three coopted opposition leaders to its federal cabinet, emphasizing its commitment to inclusivity (AllAfrica Citation2021). The incumbent followed a similar tactic at the regional level. PP’s shift towards inclusivity by appointing opposition leaders is a positive move that encourages positive electoral behavior and reduces tension. Despite its unclear impact on government stability and political dynamics, it neutralizes the opposition, giving additional leverage to the incumbent.

Asymmetric electoral authoritarianism

The PP’s electoral dominance differed by region. In regions such as SNNP, Amhara, Gambella, and Afar, the opposition succeeded by winning seats (). Recountings and reelections occurred in all opposition-won regions (NEBE Citation2021), indicating contentious races. However, the continued stronghold of the incumbent in politically significant regions such as Oromia, Sidama, and Somali cannot be ignored because they hold a substantial portion of the federal parliament.

In key regions like Oromia and Somali, limited voter choice compromised the competitiveness of the election as the ruling party was the sole candidate in most constituencies (). In both regions, the party-seat ratio is significantly high, which implies a lower level of competition. While the average party-seat ratio is 33.2, the ratios in Oromia and Somali were 64.1 and 131.1, respectively. Another important variable used to measure the variation in electoral dominance is the incumbent’s vote share in each region. In Amhara and SNNP, the incumbent’s vote share was much lower than the mean (90.2%), while in Oromia and Somali the incumbent’s vote share was 98 and 98.5, respectively (see supplemental online data D). According to Lyons and Verjee (Citation2022, 348), the HPR average candidate won with 98% of the vote in Oromia. Even in contested Oromia constituencies, the second-place candidates were far behind, receiving an average of only 2.8% of the vote. In SNNP and Amhara, the average candidate won with 79% and less than 70% of the vote, respectively. The second-place candidates in Amhara secured an average of 16% votes, while in 32 constituencies, the second-place candidate managed to collect at least 20% of the vote. Interestingly, in 17 constituencies, the winner received less than a majority of the vote, indicating high competition. The result proves the H2a hypothesis, which predicts the occurrence of subnational regime variation within Ethiopia.

Table 3. Regional elections typology.

A comparative analysis of the 2021 and 2015 elections reveals shifts in voting patterns across regions. In Amhara and SNNP, the ruling party’s vote share has decreased significantly compared to 2015. The PP received 68.5% (Amhara) and 82% (SNNP) of the votes, compared to the EPRDF’s 93% and 93.4% vote share in 2015. In contrast, in Oromia, the incumbents’ vote share increased from 93% to 98.5% (). Like Oromia, the Somali region witnessed a lack of viable opposition due to subnational authoritarianism, forcing the main opposition, ONLF, to boycott.

The regionally asymmetrical authoritarianism this article uncovered is substantiated by the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) indicator of ‘subnational election unevenness’, a metric that gauges the disparities in the fairness and openness of subnational elections across regions. The metric uses a scale ranging from 0 to 2. The closer the score is to 0, the more uneven the election is. Ethiopia’s scores on this indicator were 0.629 for 1995–2005 and 0.65 for 2010 and 2015. With a score of 0.458 in 2021, Ethiopia reached its lowest, underscoring regionally symmetrical authoritarian practices throughout different regions (supplemental data E). This finding accentuates the disparities in political rights and freedoms experienced by Ethiopian citizens in different parts of the country.

In contrast to the 2021 election, the 2015 electoral landscape in Ethiopia did not exhibit such a regional divide. However, there was an urban-rural asymmetry in the 2005 elections, wherein opposition parties enjoyed greater support in urban centers while the incumbent party maintained a stronghold in rural areas (Lyons Citation2010). In the 2021 election, although Balderas and Ezema received 32% of the total votes in Addis Ababa, they failed to secure any seats (Lyons and Verjee Citation2022, 348). This underscores the impact of the fragmentation of opposition parties in 2021 compared to 2005, where they formed a coalition that enabled them to win all seats in Addis Ababa. The distribution of vote shares in Addis Ababa, Amhara, and SNNP implies that opposition parties would get more seats under a proportional electoral system, indicating the relevance of reforming Ethiopia’s electoral system to promote a more equitable and inclusive political landscape.

Explaining asymmetric electoral dominance

Asymmetrical repression

The variation in the repression faced by opposition parties during Ethiopia’s 2021 elections significantly contributed to regionally asymmetrical electoral outcomes. While Amhara and SNNP allowed relatively more space for opposition activities, oppositions in Oromia and Somali regions faced repression, harassment, and violence (Lyons and Verjee Citation2022). Further, the main opposition parties in Oromia, OLF and OFC, withdrew from the election as their candidates were detained and their offices were raided (DW Citation2021).

Likewise, three of the five registered parties, including the main opposition ONLF, withdrew from the contest in the Somali region. Abdi Mahdi, the ONLF’s chairman, stated that ‘there is no sense in pursuing an election that has already been decided’. In their joint statement made days before the poll, the Freedom and Equality Party (FEP) and EZEMA parties stated, ‘with the absence of a possibility for a free and fair elections, we withdraw from the elections’ (Addis Standard Citation2021). The differential treatment of EZEMA, with its free contestation in Amhara, SNNP, and Addis Ababa but forced withdrawal in Somali, indicates the regional nature of authoritarianism rather than top-down strategies. demonstrates that the level of contestation in Oromia and Somali was notably lower compared to other regions, where all seats were contested. Even the contested parties in these regions lacked popular support, resulting in the ruling party’s complete control over all seats.

It is important to ask why the incumbent wanted to restrict opposition in these regions. Considering their popularity and the large constituencies in these regions, unrestricted participation of strong opposition in Oromia and Somali would have significant implications for regional leadership and the national parliament. Notably, the formation of a coalition among the three major Oromo opposition parties (OFC, OLF, and Oromo National Party – ONP) posed a real threat to the incumbent regional leaders (Oxford Analytica Citation2020). Pre-election opposition rallies demonstrated that these parties posed a valid risk of capturing regional power through the electoral process. This appears to have led regional incumbents to resort to heavy-handed tactics, as merely relying on their incumbency status was inadequate to secure dominance. The surprising outcome of the 2005 elections, which caught the EPRDF off guard, appears to have served as a reminder of this risk. To prevent a similar result, the PP seems to have chosen to eliminate critical opposition from freely contesting in crucial regions. The analysis supports H2b, which anticipated opposition suppression in core regions (such as Oromia) and regions with strong opposition (such as Oromia and Somali). This striking disparity underscores the impact of asymmetric electoral authoritarianism on election outcomes. The restriction of opposition parties skewed the playing field more visibly in some regions than others.

Ethnonationalism

The registration of 53 political parties for the 2021 elections indicates the regionalized and ethnicized nature of Ethiopia’s political and electoral landscape. Notably, 31 parties proudly bear the names of the specific ethnic group they purportedly represent. Ethnonationalism, a significant force in Ethiopian politics (Yimenu Citation2022a; Citation2022b), is crucial in explaining the asymmetrical electoral outcomes. The hyphothesis that regions with diverse territorial-ethnic groups will have more competitive regional elections than others has been confirmed in the four regions where opposition parties emerged victorious. These regions are home to diverse territorial ethnic groups. In these regions, ethnic-based parties such as NAMA (Amhara), GPLM (Anuak), GPDO (Gedeo), KPDP (Kucha) in SNNP, and APDO (Argoba) in Afar won seats. It is crucial to highlight that NAMA’s electoral success in the Amhara region is primarily due to its portrayal as a genuine advocate and protector of Amhara interests rather than catering to a minority. Though they did not win seats, minority parties such as Agaw National Shengo (Agaw), APDP (Argoba), Raya Rayuma Democratic Party (Raya), and Kimant Democratic Party (Kimant) have contributed to a competitive electoral landscape in the Amhara region. On the other hand, EZEMA, a party not officially affiliated with any specific ethnic group, secured seats in SNNP by mobilizing candidates from indigenous ethnic groups, particularly the Gurage. Six of the ten regional seats and two of the four federal seats EZEMA won are constituencies (Ezha 1 and 2) inhabited by the Gurage ethnic group (NEBE Citation2021). The success of EZEMA, led by Birhanu Nega, who has a Gurage identity, underscores the significance of ethnic affiliations in electoral outcomes in Ethiopia.

While rigorous statistical tests with limited observations and numerous variables are challenging, three correlation tests are conducted. (1) the relationship between regional ethnic diversity and the success of opposition parties reveals a correlation coefficient of +0.86. The findings indicate that an increase in regional ethnic diversity corresponds to a higher likelihood of success for opposition parties. (2) the relationship between diversity and the incumbent’s vote share shows a correlation of coefficient −0.37, which indicates that as regional ethnic diversity increases, the incumbent’s vote share tends to decline. (3) a +0.74 correlation coefficient between regional ethnic diversity and the number of regional parties suggests a strong positive relationship between the two variables, substantiating the earlier discussion on the importance of ethnicity in Ethiopian electoral politics (Supplemental Data D). The results support hypothesis H2c, which suggests that ethnically diverse regions will have experienced relatively competitive elections. However, as these results do not indicate causality, and the number of observations is limited, further analysis is required to understand the underlying dynamics.

The competition in regions with diverse ethnic groups and ethnic parties is driven by practical and tactical considerations. Firstly, voters tend to support small ethnic parties representing their ethnonationality rather than the ruling party because ethnic parties utilize ethnic sentiment and victimhood rhetorics to garner support. The large number of parties in SNNP, which boasts 55 territorial ethnic groups, and the fact that 50% of regional seats won by the opposition are in SNNP indicates strong voter support for ethnic parties. This preference reflects a desire for ethnic representation and inclusion within the political system. Secondly, the election of small ethnic parties contributes to ethnic representation and power-sharing, which helps mitigate the influence of ethnonationalism and fosters inclusivity. As a result, federal leaders and regional incumbents tend to allow these ethnic parties to compete freely, as their presence contributes to a more diverse and representative political setting. In such regions, federal party elites tend to informally devolve an increased authority to manage oppositions considering the regional context (see supplemental data D). Given the ongoing importance of ethnic politics in Ethiopia, regional elections will likely remain influenced by ethnic affiliations and the mobilization of ethnic groups.

Ethnic mobilization is relatively easy for ethnic parties in a region dominated by one nation, such as Oromia, Somali and Sidama, unlike the nationalized incumbent party. For instance, Oromos exhibit a stronger preference for their ethnic identity over Ethiopian identity than other groups (Ishiyama Citation2022, 96). Hence, Allowing strong ethnic parties such as OLF, OFC, and ONLF to freely compete in politically and electorally important, ethnically homogenous regions like Oromia, Somali, and Sidama carries risks for a regime seeking dominance as strong ethnic parties could easily mobilize support. The regime confronts a dilemma, balancing potential gains in legitimacy and inclusivity by allowing popular ethnic parties to compete with the risks of power fragmentation and challenges to its authority. Balancing control and managing ethnonationalism sentiments presents a complex challenge for the regime.

Regional partisan enclave and political relevance

The incumbent’s strong approach in Oromia can be attributed to the region’s significance as the incumbent’s core constituency, requiring tactics for electoral dominance to secure constituencies and retain a majority in the federal parliament. This mirrors the pattern observed during the rule of the TPLF-led EPRDF, where opposition was eliminated in Tigray (Mezgebe Citation2015; Rohrbach Citation2021), the TPLF’s core region. Following a similar path, PP eliminated opposition in Oromia, the PM’s constituency. The logic behind this is that ‘you cannot manage others’ homes without effectively controlling your own’. Although PP is a new party, it inherited EPRDF’s personnel and norms, which made it easy for the party to ensure dominance and portray invincibility in the core regime region. Compared to the EPRDF era, the Oromia region leaders have every reason to ensure dominance as they are now in charge of both the centre and the region.

Oromia, Somali, and Sidama regions can be characterized as partisan enclaves where the incumbent has a stronghold. While some of the Oromo nation may oppose PM Abiy, his Oromo heritage has been crucial in bolstering PP’s support in Oromia. Similarly, the increased involvement of Somali region officials in PP has increased the party’s influence and support. Furthermore, the creation of the Sidama region under PP’s leadership has transformed it from a restive constituency to a stronghold for the incumbent. These regional enclaves played a significant role in shaping electoral outcomes and highlighting the strong alignment of certain regions with specific parties or leaders.

Conclusions

This article comprehensively analyzed elections under two dominant parties in Ethiopia to assess changes and continuities of electoral dominance tactics and their impact on electoral outcomes. The article used quantitative data to compute various indicators to compare electoral outcomes under the two parties. Further, qualitative analyses of secondary sources were conducted to examine whether and how two different parties sustain and/or modify authoritarian tactics. The analyses show that the electoral manipulation and dominance pattern during the EPRDF era was sustained under PP, ultimately contributing to similar electoral outcomes, enabling PP to emerge victorious with a substantial margin as the EPRDF. However, elections under PP were more competitive regarding opposition votes and seat shares than the previous two elections under the EPRDF.

The Ethiopian experience underscores the persistent patterns of opposition repression and electoral manipulation by new ruling parties arising post-protest. Even as change agents emerge from within authoritarian parties, their endeavors to transcend entrenched authoritarian practices face impediments due to the transfer of officials and the perpetuation of authoritarian norms. Ethiopia also underscores that beyond maintaining manipulation tactics, successive dominant parties also address historical grievances, including autonomy demands and marginalization, as a strategic means to broaden their support base and bolster their legitimacy, provided that addressing these demands does not threaten their power.

Further, insights from Ethiopia contribute to the literature on subnational authoritarianism. Ethiopia showcased that subnational incumbents may allow certain opposition parties to operate freely while suppressing others. The analysis suggests that dominant parties tend to tolerate opposition parties only in circumstances where they pose no significant threat to seize power and when their constituencies do not hold pivotal importance in forming a parliamentary majority. Besides, in ethnicized political environments, popular oppositions in core regions face more repression than others as central party leaders align with particular ethnic regions considered to be the core. Moreover, the article underscores the importance of regionalization in multi-level elections within multi-ethnic states, where diverse regions exhibit asymmetric competition and opposition success. The findings suggest that elections in ethnically diverse regions tend to be more contested than those in ethnically homogeneous regions within the same federation. This higher competition arises as the dominant incumbent allows small ethnic parties to participate freely, recognizing that their inclusion in parliament facilitates minority representation, mitigates feelings of exclusion, and enhances the regime's legitimacy. Furthermore, the substantial voter support for ethnic parties contributes to this dynamic. Future research should prioritize generating more rigorous quantitative data to thoroughly assess and validate the statistical significance of this argument on a broader scale.

The practical implications of the article's insights are noteworthy. The Ethiopian case is an illuminating example of the difficulties in achieving democratic transition in multi-ethnic federation, highlighting the formidable obstacles encountered as successive dominant parties uphold and refine authoritarian tactics. Within this context, the study emphasizes the pivotal role of fair electoral practices in facilitating active participation by main opposition parties, thereby contributing to the establishment of democracy. The article suggests that democratic transition in states like Ethiopia could be facilitated by the opposition forging a coalition to counter the dominant incumbent, adopting a proportional electoral system to ensure diverse party representation, and incumbents’ commitment to free elections. Lessons from Ethiopia's electoral experiences under two parties can inform strategies to improve electoral processes and address the challenges of democratization in multi-ethnic federations.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (50.5 KB)Acknowledgements

I am grateful to two anonymous reviewers and ARoRE editors, Arjan Schakel and Valentyna Romanova, for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aalen, Lovise. 2002. Ethnic Federalism in a Dominant Party State: The Ethiopian Experience 1991–2000. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute.

- Aalen, Lovise, and Kjetil Tronvoll. 2009. “The End of Democracy? Curtailing Political and Civil Rights in Ethiopia.” Review of African Political Economy 36 (120): 193–207.

- Abbink, Jon. 2006. “Discomfiture of Democracy? The 2005 Election Crisis in Ethiopia and Its Aftermath.” African Affairs 105 (419): 173–199. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adi122.

- Abbink, Jon. 2009. “The Ethiopian Second Republic and the Fragile ‘Social Contract’.” Africa Spectrum 44 (2): 3–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/000203970904400201.

- Addis Standard. 2020. “News: OLF, OFC and ONLF Oppose HoF’s “Unilateral Decision” to Extend Incumbent’s Term Limit, Call for Inclusive Dialogue.” https://addisstandard.com/news-olf-ofc-and-onlf-oppose-hofs-unilateral-decision-to-extend-incumbents-term-limit-call-for-inclusive-dialogue/.

- Addis Standard. 2021. “Breaking: More Opposition Parties Pull out of Upcoming Elections in Somali Region.” Addis Standard (blog). September 21, 2021. https://addisstandard.com/breaking-more-opposition-parties-pull-out-of-upcoming-elections-in-somali-region/.

- Aljazeera. 2021. “Ethiopians Vote in Elections Seen as Test for PM Abiy Ahmed.” https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/6/21/ethiopia-votes-in-a-delayed-poll.

- AllAfrica. 2021. “Ethiopia: Abiy Appoints Opposition Leaders to New Cabinet.” The East African, October 7, 2021, sec. News. https://allafrica.com/stories/202110070693.html.

- Arriola, Leonardo R., and Terrence Lyons. 2016. “Ethiopia: The 100% Election.” Journal of Democracy 27 (1): 76–88. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2016.0011.

- Ayele, Zemelak A. 2018. “EPRDF’s ‘Menu of Institutional Manipulations’ and the 2015 Regional Elections.” Regional & Federal Studies 28 (3): 275–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2017.1398147.

- Bader, Max, and Carolien Van Ham. 2015. “What Explains Regional Variation in Election Fraud? Evidence from Russia: A Research Note.” Post-Soviet Affairs 31 (6): 514–528. https://doi.org/10.1080/1060586X.2014.969023

- BBC. 2020. “Tigray Crisis: Ethiopia Orders Military Response after Army Base Seized.” November 4, 2020. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-54805088.

- BBC. 2021. “Ethiopia’s Election 2021: A Quick Guide.” BBC News, June 14, 2021, sec. Africa. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-57102189.

- Benton, Allyson. 2013. “How Does the Decentralization of Political Manipulation Strengthen National Electoral Authoritarian Regimes? Evidence from the Case of Mexico.” SSRN Scholarly Paper. Rochester, NY.

- Benton, Allyson. 2017. “Configuring Authority Over Electoral Manipulation in Electoral Authoritarian Regimes: Evidence from Mexico.” Democratization 24 (3): 521–543.

- Birch, Sarah. 2011. Electoral Malpractice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bogaards, Matthijs. 2009. “How to Classify Hybrid Regimes? Defective Democracy and Electoral Authoritarianism.” Democratization 16 (2): 399–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510340902777800.

- Brownlee, Jason. 2009. “Portents of Pluralism: How Hybrid Regimes Affect Democratic Transitions.” American Journal of Political Science 53 (3): 515–532. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00384.x.

- Bunce, V. J., and S. Wolchik. 2009. “Democratization by Elections? Postcommunist Ambiguities.” Journal of Democracy 20 (3): 93–107. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.0.0093.

- Cantú, Francisco. 2017. The Geographical Menu of Manipulation: Bolivia’s 2008 Recall Referendum. Houston: University of Houston.

- Diamond, Larry. 2002. “Elections Without Democracy: Thinking About Hybrid Regimes.” Journal of Democracy 13 (2): 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2002.0025.

- Donno, Daniela. 2013. “Elections and Democratization in Authoritarian Regimes.” American Journal of Political Science 57 (3): 703–716. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12013.

- Dube, Nagessa. 2020. “Oromo Nationalism in the Era of Prosperity Party.” Ethiopia Insight (blog). February 23, 2020. https://www.ethiopia-insight.com/2020/02/23/oromo-nationalism-in-the-era-of-prosperity-party/.

- Dunne, Michele. 2020. “Fear and Learning in the Arab Uprisings.” Journal of Democracy 31 (1): 182–192. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2020.0015.

- DW. 2020. “Crisis Looms in Ethiopia as Elections Are Postponed-Deutsche Welle – 06/16/2020.” Dw.Com. https://www.dw.com/en/crisis-looms-in-ethiopia-as-elections-are-postponed/a-53829389.

- DW. 2021. “Oromia Region is Volatile Ahead of Elections.” https://www.dw.com/en/ethiopias-oromia-region-is-volatile-ahead-of-elections/a-57928295.

- EU. 2010. EU election observation mission to Ethiopia in 2010. Addis Ababa: European Union. https://www.eeas.europa.eu/node/24414_en

- EZEMA. 2020. “Full Text of a Position Statement Issued by the Ethiopian Citizens for Social Justice (Ezema).” https://ethiopiainformer.com/2020/05/10/full-text-of-a-position-statement-issued-by-the-ethiopian-citizens-for-social-justice-ezema/.

- Forsén, Thea, and Kjetil Tronvoll. 2021. “Protest and Political Change in Ethiopia: The Initial Success of the Oromo Qeerroo Youth Movement.” Nordic Journal of African Studies 30 (4): 19–19.

- France24. 2020. “Ethiopia’s Tigray Region Defies PM Abiy with “Illegal” Election.” https://www.france24.com/en/20200909-ethiopia-s-tigray-region-defies-pm-abiy-with-illegal-election-1.

- Freedom House. 2018. “Freedom in the World 2018 - Ethiopia.” 1442381. Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2018/ethiopia.

- Gandhi, Jennifer, and Adam Przeworski. 2007. “Authoritarian Institutions and the Survival of Autocrats.” Comparative Political Studies 40 (11): 1279–1301. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414007305817.

- Gibson, Edward L., and Julieta Suarez-Cao. 2010. “Federalized Party Systems and Subnational Party Competition: Theory and an Empirical Application to Argentina.” Comparative Politics 43 (1): 21–39. https://doi.org/10.5129/001041510X12911363510312.

- Greene, Kenneth. 2011. Why Dominant Parties Lose: Mexico's Democratization in Comparative Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gudina, Merera. 2011. “Elections and Democratization in Ethiopia, 1991–2010.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 5 (4): 664–680. https://doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2011.642524.

- Howard, Marc Morjé, and Philip G. Roessler. 2006. “Liberalizing Electoral Outcomes in Competitive Authoritarian Regimes.” American Journal of Political Science 50 (2): 365–381. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00189.x.

- HRW. 2020. “Ethiopia: Opposition Figures Held Without Charge.” Human Rights Watch (bblog). August 15, 2020. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/08/15/ethiopia-opposition-figures-held-without-charge.

- HRW. 2021. “Ethiopia: Events of 2021.” Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2022/country-chapters/ethiopia.

- HRW. 2022. “Ethiopia: Events of 2021.” In World Report 2022. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2022/country-chapters/ethiopia.

- International IDEA. 2024. “Voter Turnout Database: Ethiopia.” https://www.idea.int/data-tools/data/country?country=71&database_theme=293.

- Ishiyama, John. 2022. “Does Ethnic Federalism Lead to Greater Ethnic Identity? The Case of Ethiopia.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 53 (1): 82–105. https://doi.org/10.1093/publius/pjac023.

- John, Sonja. 2021. “The Potential of Democratization in Ethiopia: The Welkait Question as a Litmus Test.” Journal of Asian and African Studies 56 (5): 1007–1023. https://doi.org/10.1177/00219096211007657.

- Kelecha, Mebratu. 2021. “Oromo Protests, Repression, and Political Change in Ethiopia, 2014–2020.” Northeast African Studies 21 (2): 183–226. https://doi.org/10.14321/nortafristud.21.2.183v.

- Levitsky, Steven, and Lucan A. Way. 2002. “Elections Without Democracy: The Rise of Competitive Authoritarianism.” Journal of Democracy 13 (2): 51–65. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2002.0026.

- Levitsky, Steven, and Lucan A. Way. 2010. Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes After the Cold War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lyons, Terrence. 1996. “Closing the Transition: The May 1995 Elections in Ethiopia.” The Journal of Modern African Studies. 34 (1): 121–142. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X00055233.

- Lyons, Terrence. 2010. “Ethiopian Elections: Past and Future.” International Journal of Ethiopian Studies 5 (1): 107–121.

- Lyons, Terrence, and Aly Verjee. 2022. “Asymmetric Electoral Authoritarianism? The Case of the 2021 Elections in Ethiopia.” Review of African Political Economy 49 (172): 339–354.

- Magaloni, Beatriz. 2006. Voting for Autocracy: Hegemonic Party Survival and Its Demise in Mexico. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- McMann, Kelly M, Matthew Maguire, John Gerring, Michael Coppedge, and Staffan I. Lindberg. 2021. “Explaining Subnational Regime Variation: Country-Level Factors.” Comparative Politics 53 (4): 637–685. https://doi.org/10.5129/001041521X16007785801364.

- Mezgebe, Dejen. 2015. “Decentralized Governance Under Centralized Party Rule in Ethiopia: The Tigray Experience.” Regional & Federal Studies 25 (5): 473–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2015.1114924.

- Miller, Michael K. 2012. “Electoral Authoritarianism and Democracy: A Formal Model of Regime Transitions.” Journal of Theoretical Politics 25 (2): 153–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/0951629812460122.

- NEBE. 1995 The 1st National Election Result. Addis Ababa: National Electoral Board of Ethiopia.

- NEBE. 2000. The 2nd National Election Result. Addis Ababa: National Electoral Board of Ethiopia.

- NEBE. 2005. The 3rd National Election Result. Abbis Ababa: National Electoral Board of Ethiopia.

- NEBE. 2010. The 4th National Election Result. Addis Ababa: National Electoral Board of Ethiopia.

- NEBE. 2015. The 5th National Election Result. Addis Ababa: National Electoral Board of Ethiopia.

- NEBE. 2021. “The 6th National Election Result.” National Electoral Electoral Board of Ethiopia. https://nebe.org.et/en.

- Oxford Analytica. 2020. “Oromo Coalition Will Trouble Ethiopia’s Ruling Party.” Emerald Expert Briefings. https://doi.org/10.1108/OXAN-DB249976.

- Pausewang, Siegfried, and Kjetil Tronvoll. 2000. The Ethiopian 2000 Elections: Democracy Advanced or Restricted?. Oslo: Norwegian Institute of Human Rights.

- Quartz. 2020. “Ethiopia’s Decision to Delay Its Election for Covid Will Have Consequences for Its Democratic Goals.” https://qz.com/africa/1870457/ethiopias-abiy-election-delay-infuriates-opposition-on-democracy.

- The Reporter. 2020. “Tigray Establishes Regional Electoral Commission.” The Reporter, 2020. https://www.thereporterethiopia.com/9914/.

- Reuters. 2021a. “Ethiopians in Three Regions Vote in Delayed Election.” https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/ethiopians-three-regions-vote-delayed-election-2021-09-30/.

- Reuters. 2021b. “EU Scraps Plan to Observe Ethiopia Election.” https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/eu-scraps-plan-observe-ethiopia-election-2021-05-04/.

- Rohrbach, Livia. 2021. “Intra-Party Dynamics and the Success of Federal Arrangements: Ethiopia in Comparative Perspective.” Regional & Federal Studies 31 (4): 475–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2020.1736569.

- Ross, Cameron, and Petr Panov. 2019. “The Range and Limitation of Sub-National Regime Variations Under Electoral Authoritarianism: The Case of Russia.” Regional & Federal Studies 29 (3): 355–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2018.1530221.

- Saikkonen, Inga A.-L. 2021. “Coordinating the Machine: Subnational Political Context and the Effectiveness of Machine Politics.” Acta Politica 56 (4): 658–676. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-020-00187-z.

- Samatar, Abdi Ismail. 2004. “Ethiopian Federalism: Autonomy Versus Control in the Somali Region.” Third World Quarterly 25 (6): 1131–1154. https://doi.org/10.1080/0143659042000256931.

- Schakel, Arjan H., and Valentyna Romanova. 2022. “Regional Assemblies and Executives, Regional Authority, and the Strategic Manipulation of Regional Elections in Electoral Autocracies.” Regional & Federal Studies 32 (4): 413–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2022.2103546.

- Schedler, Andreas. 2010a. “Authoritarianism’s Last Line of Defense.” Journal of Democracy 21: 71–76.

- Schedler, Andreas. 2010b. “Democracy’s Past and Future: Authoritarianism’s Last Line of Defense.” Journal of Democracy 21 (1): 69–80. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.0.0137

- SD News. 2022. “Ethiopia’s Prosperity Party Elects a Somali as Vice President – Somali Dispatch.” March 13, 2022. https://www.somalidispatch.com/latest-news/ethiopias-prosperity-party-elects-a-somali-as-vice-president/.

- Simpser, Alberto. 2013. Why Governments and Parties Manipulate Elections: Theory, Practice, and Implications. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- TGE. 1991. Transitional Period Charter of Ethiopia.

- Tronvoll, Kjetil. 2001. “Voting, Violence and Violations: Peasant Voices on the Flawed Elections in Hadiya, Southern Ethiopia.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 39 (4): 697–716. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X01003743.

- Tronvoll, Kjetil. 2009. “Ambiguous Elections: The Influence of Non-Electoral Politics in Ethiopian Democratisation.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 47 (3): 449–474. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X09004005.

- Tronvoll, Kjetil. 2010. “The Ethiopian 2010 Federal and Regional Elections: Re-Establishing the One-Party State.” African Affairs 110 (438): 121–136. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adq076

- Tronvoll, Kjetil. 2021. “The Sidama Quest for Self-Rule: The Referendum on Regional Statehood Under the Ethiopian Federation.” International Journal on Minority and Group Rights 29 (2): 230–251. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718115-bja10055.

- V-Dem. 2023 Varieties of Democracy Datasets. Varieties of Democracy. https://v-dem.net/data_analysis/VariableGraph/

- Yimenu, Bizuneh. 2022a. “Measuring and Explaining de Facto Regional Policy Autonomy Variation in a Constitutionally Symmetrical Federation: The Case of Ethiopia, 1995–2020.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 53 (2): 251–277. https://doi.org/10.1093/publius/pjac039.

- Yimenu, Bizuneh. 2022b. “The Politics of Ethnonational Accommodation Under a Dominant Party Regime: Ethiopias Three Decades Experience.” Journal of Asian and African Studies 58 (8): 1622–1638. https://doi.org/10.1177/00219096221097663.