ABSTRACT

Privacy by Design (PbD) is crucial for fundamental privacy protection. However, PbD remains a voluntary initiative without any means to ensure its effective implementation. Article 25 GDPR codifies PbD as a legal obligation requiring technologies processing personal data to follow Data Protection by Design and by Default (DPbDD). However, Article 25 is only binding on controllers which limits its scope. For instance, the design of technologies may not coincide with the entry of the controller into the digital value chain. This implies that the burden of implementing DPbDD lies on the users of technology and not on its designers, questioning the true extent of protection by design if stages like product development and innovation are excluded. This paper explores the legislative motivation behind the personal scope of Article 25. A holistic interpretation of Article 25 in light of other provisions of the GDPR shows a possibility, albeit not direct, to influence the design phase of technologies. However, it remains unclear whether this possibility ensures a co-division of responsibility. To address this, we propose examining corporate supply chain due diligence, specifically the due diligence obligations of mother companies for actions of their subsidiaries and business relationships.

1. Introduction

Since its introduction in 1995, Privacy by Design (PbD) is widely recognised as an essential component of fundamental privacy protection (Cavoukian, Taylor, and Abrams Citation2010). PbD is a broad and multifaceted concept. In the legal and policy discourse, it is framed as an overarching and general principle, whereas in the scientific discourse, it is conflated with the use of privacy-enhancing techniques. But PbD, as conceived by Cavoukian (Citation2009), is more holistic and targets software and hardware design, business strategies and organisational practices. This allows PbD to distinguish itself from prior approaches of privacy enhancing techniques and privacy engineering. Accordingly, it has managed to receive recognition in the policy discourse. The holistic nature of PbD is complemented by its broad personal scope as PbD targets not only the design of technology but also the management of technological organisations, etc. Theoretically, PbD works because for the different development stages of information systems targeted by PbD, it also targets the different relevant actors responsible for implementing PbD measures. However, PbD remains a voluntary compliance initiative without any means to ensure its effective implementation.

Article 25 of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) codifies a similar approach as a legal obligation under which all technologies processing personal data are required to follow Data Protection by Design and by Default (DPbDD). Article 25 combines two separate obligations. On the one hand, pursuant to data protection by design (DPbDes), controllers must take all measures, either technical or organisational by nature. This allows the processing to be compliant throughout its lifecycle with the requirements of the GDPR, including the data protection principles and data subjects’ rights (Article 25(1) GDPR). On the other hand, data protection by default (DPbDef) requires controllers to ensure that processing operations are designed in such a way that personal data which is strictly necessary for each specific purpose of processing is processed (Article 25(2) GDPR). However, legal obligations resulting under this Article are restricted to data controllers, thereby considerably limiting the material scope of these obligations. For instance, the technological design and manufacturing stage may not coincide with the stage when the data controllers get involved in the data value chain. This implies that the burden of implementing DPbDD is essentially on the users of technology,Footnote1 and not on its designers.

Both PbD and DPbDD can be classified as protection by design and yet, the meaning of design in PbD is much broader and all-encompassing than in DPbDD. Design is a vague term. Scholars have described it as ‘elusive’ (Hartzog Citation2018, 11), ‘a vague concept’ (Latour Citation2010, 3), ‘fuzzy term' (Bygrave Citation2022, 37), etc. The elasticity and the different modulations of the concept of ‘design’ make it an attractive tool, especially in the design-focused discourse. However, the limits of this elasticity must be established to understand if it is reasonable to talk about protection by design in the case of DPbDD if stages like product development and innovation are excluded.

The limited personal scope of Article 25 has received criticism in legal scholarship. It has been pointed out that neither controllers nor processors necessarily take part in 'basic design decisions in information systems development' which could include steps such as the creation of models, algorithms, and other components of such systems (Bygrave Citation2017, 118). This prevents DPbDD to ensure the embedding of data protection requirements and privacy interests into information systems architecture (Bygrave Citation2020, 578). Furthermore, Article 25 targets only the controllers with an assumption and an implicit acknowledgement that for the controller to fulfil its obligations under Article 25, other actors, either involved in the processing or in the actual process of designing and developing systems used to process personal data, must comply with the requirements of Article 25.Footnote2 This implies that controllers possess the requisite influence to drive market and innovation towards privacy friendly products and services (Klitou Citation2011, 328; Bygrave Citation2022, 8). Other scholars have noted that the controller-processor-data subject framework in the GDPR, which categorically excludes producers and manufacturers, falls short in light of the key objective of GDPR, i.e. assigning ‘effective and complete protection of the persons concerned’ (Dahi and Compagnucci Citation2022). The limited personal scope of Article 25, together with other criticisms has led this Article to be considered as merely ‘a catch-all provision with no specific requirements on its own’ (Waldman Citation2018, 1256). Therefore, the extent to which the current DPbDD framework envisioned in Article 25 GDPR can provide meaningful protection of personal data by embedding data protection requirements into the design of technologies is not clear.

This paper argues that while Article 25 GDPR only targets controllers, other provisions of the GDPR can create the possibility, albeit not direct, to influence the design phase of technologies. However, the scope of this influence is not well-defined. In this regard, this paper sets out to do three things. First, the personal scope of Article 25 GDPR is explained. Second, the boundaries of the indirect influence on the design phase of technologies are drawn, based on a holistic interpretation of Article 25 in light of other GDPR provisions and its legislative history. Third, the approach of DPbDD is compared with the approach followed by Human Rights Due Diligence instruments (HRDD); HRDD is an approach which addresses corporate responsibility for human rights violations through their actions and those of their business partners.Footnote3 In this sense, this paper explores the concept of corporate leverage over actors in its supply chains and operationalisation of this leverage through different self-regulation tools.

In light of the above, this article is structured as follows. The next section, Section 2, explains the personal scope of Article 25. Section 3 shows that the provisions of the GDPR leave scope for indirect influence over the design phase of technologies. Section 4 identifies the intentions of the GDPR legislator with regards to the personal scope of Article 25. Based on a comparison between DPbDD and HRDD, Section 5 introduces the concept of leverage as a solution to address the gaps left by the limited personal scope of Article 25. Section 6 explores the tools that can allow the transposition of the concept of leverage in PDPS supply chains and its operationalisation through different self-regulation tools. The last section concludes by acknowledging that the field of HRDD can provide important lessons for a meaningful implementation of DPbDD.

2. Delimiting the personal scope of Article 25

Article 25 GDPR assigns the responsibility to implement DPbDes and DPbDef on the data controllers by requiring them to ‘implement appropriate technical and organizational measures’ (Article 25(1) and 25(2) GDPR). Data controller is defined in Article 4(7) GDPR as ‘the natural or legal person, public authority, agency or other body which, alone or jointly with others, determines the purposes and means of the processing of personal data’. The crux of this definition lies in the phrasing ‘determines the means and purposes of processing’. According to the European Data Protection Board, the word ‘determines’ signifies the influence exercised by a controller over the processing ‘by virtue of an exercise of decision-making power’ (EDPB Citation2020b, §20). ‘Purposes and means’ refer to the ‘why’ and the ‘how’ of the processing of personal data (EDPB Citation2020b, §35). Data controller is, therefore, the entity that conceptualises and designs the processing operation by determining its means and purposes. This key phrasing is mirrored in Article 25(1) which formulates the design stage in similar terms of ‘determination of means of processing’. As noted by Bygrave, the design stage is formulated in reference to when a controller ‘assumes controller status’ (Bygrave Citation2017).

The concept of data controller has been interpreted following pragmatic approach based on the factual realities and not solely on a formal legal analysis (A29WP Citation2010, 9; EDPB Citation2020b, §35; Van Alsenoy Citation2017). In this sense, A29WP states that ‘(t)the concept of controller is a functional concept, intended to allocate responsibilities where the factual influence is, and thus based on a factual rather than a formal analysis’ (A29WP Citation2010; EDPB Citation2020b). This also explains the reasoning followed by the A29WP while including in this category, entities involved in developing or supplying devices and platforms for the ‘Internet of Things’, including device manufacturers, third-party app developers, etc. (A29WP Citation2014) In a similar vein, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) has taken a broad view of the concept in order to achieve ‘effective and complete protection of data subjects’ (Google Spain, §4; Wirtshaftsakademie, §28). The qualification of controller relies on the establishment of ‘effective control on the determination of the means’ which is the decisive factor (Jehovan todistajat, §21). Therefore, the concept of controller is to be interpreted and understood following the aim of the legislator to ‘(p)lace primary responsibility for protecting personal data on the entity that actually exercises control over the data processing’ (Bygrave and Tosoni Citation2020). Nevertheless, the case law of the CJEU demonstrates that multiple entities/operators are susceptible to be qualified as controllers, either for a part or the entirety of the processing depending on control exercised (Wirtschaftsakademie, §29; Jehovan todistajat, §65).

However, even with an expansive interpretation of the concept of controller, it is highly unlikely that the concept could be extended to include actors which are indirectly involved in the data processing, such as designers and manufacturers of technologies that are used by the data controllers. A literal interpretation of these provisions, therefore, leads to the understanding that controllers are alone responsible for implementing DPbDD. The wording of both Articles 25(1) and 25(2) are framed with the controller in mind. The beginning of DPbDD obligations coincides with the moment the controller ‘assumes controller status’ by defining the different key elements of the processing activity. It is quite clear that the temporal point of reference that triggers the legal obligations under the two provisions is the intended processing operation and the word ‘design’ in DPbDD refers to the design of the processing operation. This signifies two points, first DPbDD is a legal obligation for all data controllers and not only those who employ within their organisation designers and manufacturers of technology,Footnote4 and second, the obligation of DPbDD does not apply directly to designers and manufacturers of technology, at least based on a strict literal interpretation of the relevant provisions.

The restricted meaning of the design in Article 25 as the design of the processing operation and the resulting limited personal scope prevent data protection requirements to amount to the level of functional requirements of the technology used in the processing, unless there is a possibility to influence the design phase of technologies.

3. Scope for an indirect influence on the design phase of technologies

Article 25, when interpreted in light of other provisions of the GDPR, provides a possibility for the legal obligations to diffuse upstream and downstream in the supply chains and accordingly have an influence on the design phase of the technologies.

3.1 Diffusion of DPbDD obligations to processors

With regards to the processors, Article 25 must be interpreted in light of Article 28(1) which stipulates that in the event the processing is carried out by a processor on behalf of the controller ‘the controller shall use only processors providing sufficient guarantees to implement appropriate technical and organisational measures in such a manner that processing will meet the requirements of this Regulation and ensure the protection of the rights of the data subject’ (Article 28(1) GDPR). Processor, as defined by Article 4(8) GDPR, refers to ‘a natural or legal person, public authority, agency or other body which processes personal data on behalf of the controller’.

Article 28(1) does not explicitly refer to requirements of data protection by design and by default, and the formulation of Article 28(1) could refer just as much to the requirements of Article 25(1) and 25(2) as to those of Article 32 pertaining to the security of processing due to similarly formulated legal obligations.Footnote5 Nonetheless, based on the textual formulations of the different provisions, the aim of implementing technical and organisational measures under Article 28(1) aligns with the aim of technical and organisational measures pursued under Article 25. In essence, according to Article 25(1), technical and organisational measures need to be implemented to (i) implement data protection principles and (ii) integrate necessary safeguards into the processing to meet the requirements of GDPR and protect the rights of data subjects. Article 25(2) is aimed at ‘ensuring that, by default, only personal data which are necessary for each specific purpose of the processing are processed’. Whereas Article 32(1) requires both controllers and processors to ‘implement appropriate technical and organisational measures to ensure a level of security appropriate to the risk’. Controllers are therefore required to use processors providing guarantees of implementation of appropriate measures pursuant to, inter alia, the requirements of Article 25 of the GDPR.

This interpretation aligns with the observation of the EDPS in its opinion of 7 March 2012 which states that Article 23 (current Article 25 GDPR) does not address the way a processor can be bound by the principle of DPbDD but there is a link between this provision and Article 26 (current Article 28 GDPR) on processors (EDPS Citation2012). According to Article 26(1) (current Article 28(1)), the controller must choose a processor ‘providing sufficient guarantees’ of implementation of appropriate technical and organisational measures and procedures in a way that the processing is compliant with the Regulation’ (EDPS Citation2012, §179).Footnote6

3.2 Diffusion of DPbDD obligations to designers and manufacturers of technologies

Recital 78 GDPR extends the implementation of DPbDD on other parties involved in technological value chains by stating that producers of the products, services and applications ‘should be encouraged to take into account the right to data protection when developing and designing applications, services and products that are based on the processing of personal data or process personal data to fulfil their task with due regard to the state of the art, to make sure that controllers and processors are able to fulfil their data protection obligations’. It is important to note that the recitals of the GDPR are not legally binding but can provide interpretative guidance as long as they are not used to derogate from the actual provision or reach a contradictory interpretation (Deutsches Milch-Kontor §32; Hauptzollamt Bremen §16).Footnote7

In any case, the formulation of Recital 78 does not amount to a requirement for the developers, manufacturers, designers, etc. but express only that they should be ‘encouraged to take into account data protection’ to help controllers and processors fulfil their obligations under the GDPR. It is, therefore, clear that the legal requirements of DPbDD do not directly extend to developers, manufacturers, designers, etc. The EDPS in its opinion of 7 March 2012 stated that while the principles of data protection by design and by default are not addressed to advisers, developers and producers of hardware or software, they will be relevant for them from the start, as controllers are bound by them and accountable for compliance. In other words, DPbDD obligations for controllers (and for processors, as mentioned above) are likely to create incentives for the market of relevant goods and services (EDPS Citation2012, §182). Controllers will need to rely on products and services developed in a DPbDD compliant manner in order to fulfil their legal obligations under Article 25 GDPR (Klitou Citation2011).Footnote8 Thus, the influence that controllers and processors may ultimately be able to exercise on their business partners might not be negligeable as controllers would likely seek products and services that allow them to fulfil their legal obligations under Article 25 (Jasserand-Breeman Citation2019). Consequently, Article 25 GDPR is susceptible to diffuse the legal requirements towards the designers and manufacturers of technologies used in processing of personal data.

3.3 Diffusion of obligations, not responsibility

While the legal requirements of Article 25 can cascade towards processors and designers/manufacturers, the controller remains responsible for compliance with Article 25. The controller is required to comply with DPbDD while determining the means of the processing, i.e. the ‘how’ of the processing. Decisions pertaining to the choice of processors, on the one hand, and technology to be used in the processing operation, on the other, can qualify as the means of processing. Accordingly, both decisions require the controller to comply with the requirements of Article 25. The controller must choose processors and technologies (and therefore technology producers and designers) which provide guarantees of compliance with DPbDD.

This means that in case of non-compliance, the controller engages its own responsibility. This also means that the relationship between the controller and other entities in the value chains is under ‘enhanced scrutiny’ as the actions of these entities are consequential to establish the responsibility of controllers (Michelakaki and Vale Citation2023). In this sense, this relationship can be analysed through the contracts concluded between the controller and other actors. For instance, controllers are required to outline the role of its processors, scope of the processing operation, the duties of the processors, etc. in the contracts (GPDP Citation2021).

In summary, DPbDD requirements can extend towards other actors in controllers supply chain because the controller is required to comply with DPbDD in determining the means of processing. As such, the controllers bear the primary responsibility of ensuring that the means of the processing allow compliance with Article 25.

This approach is logical as a controller has decisive power over these choices pertaining to the processing operation, but this approach is limited by the extent to which the controller has influential power over the producers of technology. Nevertheless, this approach seems to be in line with the intentions of the legislator, as seen in the following section.

4. Alignment with the legislative history

Approaching the question pertaining to the personal scope of the GDPR from the perspective of its legislative history helps in understanding the intentions of the legislator. In other words, the legislative history helps shine a light on whether the legislator truly tried to limit the scope of the legal obligations to the controllers and whether the legislative choices imply an extension of responsibility towards other actors involved.

Endorsements for a binding legal provision on PbD were widely present in the different preparatory documents of the data protection reform (EDPS Citation2011, 23; European Commission Citation2010; European Parliament Citation2011, §35). The idea put forward by different stakeholders was to codify a legal obligation that would oblige designers of products and services, and data controllers to consider data protection ‘at the planning stage of information-technological procedures and systems’ (A29WP & WPPJ Citation2009, 13). The different preparatory documents shared a common understanding of the rationale behind the codification of PbD, i.e. enhancing accountability of those processing personal data (EDPS Citation2011),Footnote9 and ensuring ex-ante and lifecycle implementation of data protection measures and safeguards.Footnote10 Furthermore, a legal obligation requiring the implementation of PbD would serve as an incentive for data controllers to proactively address data protection concerns and implement measures in their processing activities as is highlighted by the frequent linkages of PbD with the principle of accountability (European Commission Citation2012). The Impact Assessment accompanying the data protection reform stated that introducing such a principle would require the organisational structure, technology and procedures to be designed in a manner that meets the requirements of data protection (European Commission Citation2012, 52). The idea was to introduce an approach which allows for a holistic protection of personal data by making such protection an inherent part of the organisational, technological and technical structure and processes of those who play a part in personal data value chains. Nonetheless, there were divergences among the different endorsements as to how the resulting legal obligations would apply to the different parties involved in the lifecycle of data processing systems. On the one hand, there were calls that DPbDD should ‘not only be binding for data controllers, but also for technology designers and producers’ (A29WP & WPPJ Citation2009, §46). On the other hand, there was speculation that codification of privacy by design as a legal obligation even if only applicable to data controllers would create ‘a stronger demand for privacy by design products and services’ in the market (EDPS Citation2011). In this sense if PbD were to be codified as a legal obligation, there would be an increased demand for products and services designed following a PbD approach creating incentives for industry actors to meet such demand (EDPS Citation2011). Several legal scholars saw in the limited personal scope of DPbDD provision, the possibility for data controllers to demand from and incentivize engineers and designers to develop products and services compliant with the legal requirements of DPbDD (Bygrave Citation2017; Hildebrandt and Tielemans Citation2013).

As evidenced by current Article 25 GDPR, the call for codification of PbD into a legal obligation was taken into account by the European Commission which introduced the principles of DPbDD in its legislative proposal, but the resulting legal requirements were only binding on the data controllers. Despite a proposal from the European Parliament to extend the scope of the legal obligations to processors, the final text pertaining to DPbDD limited its personal scope to data controllers only.Footnote11 In summary, a historical analysis shows that there was willingness to extend the requirements to actors beyond the controllers and different avenues were also considered but ultimately, a binding legal provision in the framework of the GDPR could only expand so much as to its personal scope. Nevertheless, this does not preclude an indirect influence on the actors involved in the design phase. In summary, the legislator anticipated controllers to exercise some sort of influence over the design phase of technologies if they were legally bound to follow DPbDD.

It is regrettable that this is only reflected through the mild wording of Recital 78 which states that producers of technology shall be encouraged to follow DPbDD. While it is implied that controllers will need to exert influence over the designers/producers of technology in order to comply with their own legal obligations, it is not explicitly stated in the provisions of the GDPR. This leads to a partial understanding of the personal scope of Article 25. In the subsequent sections, this paper argues that the missing piece of DPbDD’s personal scope is the concept of leverage.

5. Using the concept of leverage to broaden the personal scope of Article 25 GDPR

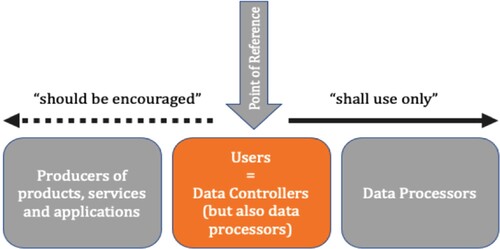

The personal scope of Article 25, as seen previously, is to be understood as a diffusion of DPbDD requirements through the controller towards the processors, on the one hand, and towards the designers/producers, on the other. Yet, the point of reference of the legal obligations remains the controller who remains responsible for implementing DPbDD, and it is only through the controller that requirements are transferred, in varying intensity, towards other actors (see below).

Figure 1. Diffusion of requirements (of Article 25 GDPR) from the controller towards other actors involved in the data value chain.

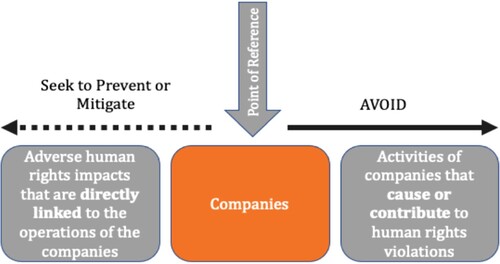

Similar mechanism based on diffusion of obligations from one entity towards others in a supply chain is also heavily relied upon in different instruments addressing corporate supply chain responsibility for human and environmental rights. For instance, the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights 2011 (UNGP or Guiding Principles) incorporating the concept of human rights due diligence (HRDD) for multinational enterprises follow a similar approach (UNGP Citation2011).Footnote12 The UNGPs introduce a three-pillared framework called the ‘Protect, Respect and Remedy’ Framework based on (i) the duty of a State to protect human rights, (ii) the responsibility of business enterprises to respect human rights, and (iii) access to a remedy for those affected (UNGP Citation2011). The second pillar of this framework, i.e. the responsibility of business enterprises to respect human rights, requires businesses to follow human rights due diligence (HRDD). HRDD is a process that requires companies ‘to identify, prevent, mitigate, and account for their involvement, both through their own activities and in their business relationships, in human rights harms to vulnerable people in their own activities and in their business relationships’ (Sherman Citation2021, 4). This means that companies are required, on the one hand, ‘(a)void causing or contributing to adverse human rights impacts through their own activities, and address such impacts when they occur’, ((UNGP Citation2011), 13(a)) and, on the other hand, ‘(s)eek to prevent or mitigate adverse human rights impacts that are directly linked to their operations, products or services by their business relationships, even if they have not contributed to those impacts’ (see below) (UNGP Citation2011, 13(b)). In other words, the point of reference is the parent company which must act depending on the actor involved. Very similar to the structure of Article 25 GDPR, HRDD focuses on the parent company to apprehend the actions of other entities operating in its supply chains.Footnote13

Figure 2. Modulation of due-diligence requirements of companies towards different actors in their supply chains.

Based on the comparison above, this paper argues that both techniques, DPbDD and HRDD, rely on a similar approach of diffusion of requirements from one actor towards others in the value chains. Nevertheless, the mechanism of HRDD (of the UNGPs) is more sophisticated when it comes to taking into account the relation between the parent company and other actors in its value chains. This is illustrated by the introduction of the concept of leverage, i.e. the influence a business enterprise can exercise on other entities in its supply chain to influence their practices and to prevent adverse human right impacts in their supply chains.Footnote14 The notion of leverage is key to the effectiveness of HRDD. Companies can exercise HRDD in their supply chains to identify human rights risks but the idea of exercising leverage to prevent those risks is key to avoid such risks from materialising.

The provisions of the UNGPs explain in great detail the situations in which such leverage exist, the factors to consider in determining appropriate action, how companies can increase leverage, what steps a company must take in situations where there is a lack of leverage and no possibility to increase it and finally, what happens if there is no leverage, and it concerns a crucial relationship to the enterprise (Guiding Principle 19).

This technique of targeting one entity and diffusing requirements through it towards other entities in complex value chains is innovative without which, the actions of the other entities would be difficult to apprehend. While the exercise of due diligence is necessary to identify risks and potential impacts, the exercise of leverage is crucial to prevent those impacts of risks from materialising.

6. Transposing the concept of leverage to data value chains

6.1 Concept of leverage and its framework

Traditionally, States are responsible for the protection and promotion of human rights. While the idea of shifting this responsibility on corporations is controversial, recognising that they have opportunities to ensure the protection and promotion of human rights is not far-fetched (Sorell Citation2005). This recognition draws from the fact that multinational corporations exert huge influence on the enjoyment of human rights whether they are directly or indirectly affected by their activities (Guiding Principle 19). Several authors have recognised the leverage of multinational corporations on their business relations but also on the governments of countries they operate (Bomann-Larsen Citation2014). Corporate influence can mean two different things – one is impact, where the activities and relationships are causing human rights violations and the other is leverage that a business can exert over the actors responsible for causing the human rights impacts (UNHRC Citation2008, §13).

Apprehending corporate violations of human rights has always proven to be difficult mainly due to the governance gaps created by increasing globalisation and complexifying corporate supply chains (UNHRC Citation2007). As a result, human rights impacts linked to corporate activities are not always direct and within the strict sphere of their direct business activity. To extend the scope of corporate responsibility to respect human rights beyond their workplaces and draw the outer boundaries of corporate influence, different solutions have been proposed. For instance, the notion of ‘sphere of influence’ (SOI) which refers to ‘the boundaries of an organization's responsibility when other actors with whom it is connected engage in human rights abuses’ (Wood Citation2012). The concept was first introduced in the corporate social responsibility discourse in 2000 by the United Nations Global Compact.Footnote15 However, the concept of SOI was criticised for its simplicityFootnote16 and its conflation of ‘influence’ as ‘impact’ and ‘influence’ as ‘leverage’. Other concepts such as ‘control’, ‘causation’ and ‘complicity’Footnote17 were also explored in the quest of finding the best conceptual tools to apprehend human rights impacts caused by the actions of third parties but were dismissed for their lack of sufficient rigour in allowing companies to identify specific actions. The UNGPs use the notion of business relationships as an alternative. The idea being that companies may be involved with adverse human rights impacts either through their own activities or as a result of their business relationships. Business Relationships is a broader and flexible term that includes relationships with the different entities in a company’s value chain (Shift Citation2012).

Accordingly, the UNGPs are based on the idea that a company can exercise due diligence over its business relationships as an alternative. In this sense, due diligence is used as the standard of conduct that qualifies a business’s responsibility for third-party impacts (UNHRC Citation2008). Accordingly, the concept of leverage defines the extent of a business enterprise’s responsibility for human rights impacts of third parties and is defined as a business’s ability to exercise influence over the third party in practice (Bonnitcha and McCorquodale Citation2017). The commentary on the Guiding Principles explains that the exercise of leverage must be based on a contextual judgement of what is reasonable in the circumstances and should take into account different factors, including how crucial the relationship is to the enterprise, the severity of the abuse, whether terminating the relationship in itself would have adverse human rights impacts and whether capacity building or other incentives may increase leverage (UNGP Citation2011, 19 (commentary)).

While the business enterprise required to exercise leverage will not be responsible for the third party’s adverse human rights impact, it is required to take diligent steps in exercising leverage. These steps are not listed in the UNGP framework but can be found in the subsequent adaptations of the HRDD concept in other legal instruments.

6.2 Operationalisation of the notion of leverage through practical tools

Leverage, as seen previously, is a core concept of HRDD. The way it has been framed in the UNGP is abstract and difficult to operationalise. However, upcoming legal instruments, including in the European Union (EU), incorporating the concept of HRDD are more explicit in listing specific tools that companies could use to operationalise the concept of leverage in their value chains. For instance, the proposal for the EU directive on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence (CSDD) requires Member States to ensure that companies integrate due diligence into all corporate policies and have in place a due diligence policy that is updated annually (Proposed CSDD Directive Citation2022). Part of the due diligence policy should be a code of conduct (CoC) to be followed by the company’s employees and subsidiaries. Compliance with the CoC should be ensured through contractual assurances accompanied by appropriate measures to verify compliance (Recital 34 of the Proposed CSDD Directive Citation2022). The CoC should apply in all relevant corporate functions and operations, including procurement and purchasing decisions. The contractual assurances or the contract shall be accompanied by the appropriate measures to verify compliance. For the purposes of verifying compliance, the company may refer to suitable industry initiatives or independent third-party verification (Article 7(4) Proposed CSDD Directive Citation2022).

In this sense, these instruments rely on different tools, such as codes of conduct, third-party verification tools and contractual assurances, for the exercise of leverage in corporate supply chains. The provisions of the GDPR do not explicitly address the concept of leverage or the use of above-mentioned tools in the framework of DPbDD. Nevertheless, an analysis of DPA decisions, in the subsequent section, shows such tools are an important indication of the nature of the relationship between different entities involved in data value chains.

6.3 Exploring transposition of leverage in data value chains

An analysis of the decisions of different DPAs pertaining to Article 25 GDPR demonstrates that the tools used to operationalise leverage in corporate supply chains are also inherently and organically used in data value chains. In the previous section, this paper identified three tools that can help operationalise leverage in corporate supply chains – (i) the use of third-party verification tools, such as audits and inspections, (ii) the conclusion of contracts and (iii) the use of codes of conducts. The paper does not claim that these tools are foreign to the GDPR framework and must be adopted from the field of CSCDD, but that these tools which are already present in the different provisions of the GDPR should be used in the context of Article 25, with regards to the relationship between controllers and other entities in the data value chain.Footnote18

There is considerable evidence in decisions of the DPAs, as seen in the following paragraphs, which reflects that the controller retains complete responsibility for compliance with Article 25. However, the assessment of compliance with Article 25 takes into account the relationship between a controller and its processors. In this sense, the Italian DPA fined a telephone operator Wind Tre SPA for unlawful processing of personal data, for mainly unauthorised marketing. It was found that there was a lack of control of the controller over its supply chain as the subcontractors were conducting promotional campaigns in the interest of Wind Tre SPA, while the latter disowned such activities. Furthermore, despite discrepancies concerning the source of contact data, the controller did not acknowledge or take action against the illicit practices of its processor. As such, Wind Tre SPA as a controller failed to adopt adequate technical and organisational measures with regard to the inability to effectively control its chain of partners who carry out promotional activities for its benefit (Garante Citation2020). Similar logic was retained by the Spanish DPA when it fined Vodafone for failure to ensure that their processor had and continued to implement appropriate technical and organisational measures to ensure compliance with the GDPR (AEPD Citation2021). Consequently, DPAs have noted that the controller must have absolute control over the processing carried out by the processor.

Controllers are, therefore, responsible for ensuring that their processors have taken adequate technical and organisational measures in the beginning and over the course of the processing by conducting subsequent audits. In this sense, the Polish DPA found that controllers are required to conduct periodic and systematic audits or inspections to assess the services provided by their processors, in accordance with Article 28(1) GDPR. In this sense, Article 28(1) requires controllers to only use processors providing sufficient guarantees to implement appropriate technical and organisational measures so that the processing fulfils the requirements of GDPR and protects the rights of the data subjects. Data controllers are therefore required to verify compliance of data processors before contracting them and to monitor compliance through periodic audits (UODO Citation2022).

In another case, the Polish DPA fined a controller who failed to verify the methods used by its processor to detect security vulnerabilities. The DPA noted the scope of technical and organisational measures under Article 25 includes the data controller to detect, remedy and report security violations, including obliging the processor to deal with any potential or actual security threats (UODO Citation2020).

DPA decisions have also consistently noted that the relationship between controllers and processors must be framed in a written agreement in accordance with the requirements of Article 28 and 29 GDPR (Garante Citation2020). For instance, the Italian DPA found that the Municipality of Rome had violated Article 25 GDPR as it did not define, in a written agreement, the role of its processor and the modalities of the processing, including the retention periods, the purposes of processing, types of personal data, categories of data subjects, etc. (UODO Citation2020).

While there are no specific decisions (to the best of the author’s knowledge) that require controllers to use codes of conducts to comply with their obligations under Article 25, Article 40 GDPR lists in great detail the use of codes of conduct, including the mandatory monitoring of compliance, in a similar logic to that followed in CSCDD. In this sense, the EDPB guidelines state that codes of conduct recognised by associations representing categories of controllers can help in the determination of appropriate measures, but the controllers must ensure the appropriateness depending on the particular circumstances of each processing (EDPB Citation2020a, 6).

Decisions of DPAs show the versatility of tools, such as audits and contracts, as tools of accountability and compliance under the GDPR. Their use as means of exercising leverage and due diligence by controllers over their partners cannot be undermined.

6.4 Enhanced role of audits, CoC and contracts

The concept of leverage plays a fundamental role in allowing companies to meet their corporate responsibility to respect human rights. This is even more true in the case of DPbDD and the diffusion of its requirements towards other actors which are not directly targeted by the text of Article 25 GDPR. A data controller cannot successfully comply with the requirements of Article 25 if other actors in its supply chain are not compliant. Second, without the compliance of processors and manufacturers, the GDPR's objective of assigning ‘effective and complete protection of the persons concerned’ falls considerably short (Dahi and Compagnucci Citation2022).

Leverage is not a one-shot mechanism but a continuous process. As such the tools that operationalise the concept of leverage need to consider this. Previous sections have argued two important points, (i) the concept of leverage is implicitly a part of the DPbDD framework as introduced in Article 25, and (ii) different elements of leverage tools are already being used in the context of Article 25. In this sense, this section highlights the role that the three leverage tools (i) codes of conduct, (ii) audits and (iii) contracts can adopt in allowing controllers to exercise leverage over their partners in the context of ensuring compliance with Article 25.

6.4.1 Codes of conductFootnote19

In regulating Corporate Social Responsibility (Commission of the European Communities Citation2001, §20),Footnote20 Codes of Conduct (COC) have evolved from purely voluntary self-regulation tools to tools of co-governance as they are increasingly mandated by international and national hard law instruments (Blecher Citation2017). COC are highly flexible and versatile corporate instruments. They are flexible because they contain values and norms that are specific to each company (Eijsbouts Citation2017) and versatile because they could apply equally to internal and external stakeholders. As such, scholars claim that COC contain the identity of a company and is a prerequisite of responsible management (Eijsbouts Citation2017). The scope of COC is increasingly encompassing corporate supply chains as companies use these instruments to introduce their sourcing policies and practices (Cafaggi Citation2013).

In this sense, CoC can be extremely useful instruments in ensuring compliance with the requirements of DPbDD by other actors operating in data controllers’ supply chains. In this sense, Article 25 mandates the adoption of both technical and organisational measures. Organisational measures refer to procedures and policies adopted to manage data processing (Jasserand-Breeman Citation2019). In this regard, the adoption of a COC highlighting the values, commitments, and policies of the controller organisation in relation to personal data processing can be a valuable organisational measure as required by Article 25(1) and 25(2). In more practical terms, compliance with such a code can be strengthened with stakeholder engagements and ensuring that the COC has the buy-in from relevant partners (Friedman, Hendry, and Borning Citation2017). Furthermore, subsequent monitoring of the code can be ensured by allocating managerial responsibilities for report of breaches and adoption of adequate remedial measures. Finally, adherence to the controllers COC must be made a part of their contracts with relevant actors (Smit et al. Citation2021).

6.4.2 Audits

As HRDD started to crystallize as a prevalent norm of soft law and hard law, companies started to come under pressure for the possible human rights related impacts of their suppliers and subsidiaries operating in different countries. Audits and certifications became, as a result, important tools of ensuring that corporate supply chains were respectful of human rights and environmental norms (Rogge Citation2020).

DPbDD requires organisations to implement technical and organisational measures from the conception of systems, processes or products that are used to process personal data in order to address their data protection and privacy risks (Article 25(1) and 25(2) GDPR). Conducting a data protection audit can help assess an organisation’s compliance to DPbDD and verify the resilience of the measures adopted. Article 24(1) GDPR mandates the measures adopted by controllers (including measures adopted under Articles 25(1) and 25(2) GDPR) to by reviewed and updated regularly under the accountability principle. In this sense, one of the core elements of controllers’ accountability are ‘systems for internal and ongoing oversight, review and updating and for external verification’ of which third-party audits form an important means (Docksey Citation2020).Footnote21

When it comes to controllers’ value chains and the role of audits, there are two areas of interest. First, audits can help identify compliance gaps. Audits involve a comprehensive review of an organisations’ data processing operations and as such are a crucial tool of mapping gaps and weaknesses (A29WP Citation2016).Footnote22 This can help a controller understand if the principles of DPbDD are adequately incorporated in controllers’ operations. Second, audits can assess the relevance and resilience of technical and organisational measures in place, for instance, regarding the data handling policies, consent mechanisms and data retention and deletion policies.

Overall, audits can contribute to ensuring that the technical and organisational measures to be adopted under Article 25 are meaningfully implementing the different data protection principles and data subject rights. In this sense, audits can assess how personal data is handled throughout the lifecycle of technology products and services, from design and development phase to manufacturing, distribution and use. They can assess whether DPbDD principles have been integrated into the development of technology products. They can also evaluate how personal data is collected, processed, and used by technology products or services, the security measures in place, exercise of data subject rights of access, rectification, erasure and portability, mechanisms for deletion, etc.

Furthermore, audits can help provide a systematic and objective evaluation of a controller’s data protection practices, making them an effective tool for assessing and enhancing compliance with DPbDD. They also help controllers identify areas for improvement and take necessary corrective actions to meet the requirements of data protection regulations effectively. This makes audit an indispensable tool for the reiterations of DPbDD measures.

All in all, as DPbDD is a reiterative and cyclic process, audits can be highly versatile tools useful in evaluating the different aspects of a processing operation, in addition to the compliance of different actors with DPbDD.

6.4.3 Contracts

GDPR provisions rely on different contractual tools which play a crucial role in ensuring compliance with data protection rules in controllers’ value chains by establishing the legal framework and obligations for data processing activities, ensuring that all parties involved adhere to data protection requirements throughout the value chain. Some of these contractual tools are data processing agreements (Article 28(3) and Recital 81 GDPR), standard contractual clauses, binding corporate rules, data sharing agreements, sub processing agreements (Article 28(4) GDPR), etc. Apart from data processing agreements (establishing the relationship and responsibilities between controllers and processors) and sub processing agreements (establishing the relationship between processors and their sub processors), other GDPR contractual tools are more oriented towards data transfers and data sharing. Nevertheless, even if the GDPR does not explicitly state their role in ensuring compliance with the requirements of DPbDD, such tools can play an important role when it comes to exercising leverage in controllers value chains.

The recent proposal of the EU directive on CSDD goes beyond model contracts and introduces the technique of contractual cascading (Articles 7(2)(b) and 8(3)(c) of the Proposed CSDDD Directive Citation2022), whereby a company is obligated to ensure compliance of only its direct business partners but impose on these direct business partners an obligation to regulate and monitor the activities of indirect business partners. This technique is supposed to remedy the situation where the contractual obligation of the indirect partner is owed to the direct partner, but its compliance is monitored by the parent company. The parent company is still obligated to take action if a breach by its indirect partner comes to light, but it is not required to investigate (Proposed CSDD Directive Citation2022, 17). This technique could very well fit in the responsibilities of the controller to ensure compliance with DPbDD. For instance, a controller could be in a direct business relationship with its processors, on the one hand, and the providers of technology on the other. With the technique of contractual cascading the requirements of DPbDD can be transferred more easily towards other actors without unnecessarily increasing the burden on controllers.

6.4.4 Use of leverage by data controllers as part of the legal requirements under Article 25

In section 3.3, this paper argued that the decisions regarding the choice of a data processor and regarding the choice of the technology to be used in the processing operation qualify as the means of processing over which the controller exerts determinative influence. This is based on the assessment of the CJEU according to which the qualification of controller is based on factual realities more than formal designation and take into account the influence that an entity might exercise over the purposes and the means of a processing operation even if the entity in question de not have access to the personal data (Jehovan todistajat, §21; EDPB Citation2020b; Van Mil and Quintais Citation2022).

Article 25(1) and (2) require controllers to implement DPbDD both at the time of determination of means of processing and at the time of processing itself. This means that controllers are required to implement technical and organisational measures in line with DPbDD also at the time of the determination of means of processing. Consequently, technical, and organisational measures ensuring compliance with Article 25 GDPR are required pertaining to the choice of the processors and technology to be used. Bygrave defines technical measures as measures that ‘directly concern, and are often executed in, the mechanics or workings of devices, objects, systems or processes’, whereas organisational measures are defined as measures involving ‘the assignment and management of roles, duties or tasks in connection with such development or deployment, typically within the aegis of a collective entity' (Bygrave Citation2022). The tools mentioned previously in this section could fit within the scope of the organisational measures that the controller is under a positive obligation to adopt pursuant to the different requirements of Article 25.

All in all, the tools discussed above (CoC, audits and contracts) could qualify as both appropriate and effective organisational measures regulating the relationship between controllers and other actors involved in the data value chain. CoC can outline the values of a controller organisation, contracts can make those values legally binding, and audits can constitute the tools to ensure that the values are being adequately respected over the lifecycle of the processing. The adoption of these tools as organisational measures by the controller can allow them to exercise leverage on their partners. Finally, the controller is required to implement the legal obligations resulting under Article 25 at the time of the determination of the means of processing. Both the choice of a processor and of the technology to be used to process personal data qualify as means of processing. Effective organisational measures would be choosing partners with sufficient guarantees and alternatively, exercising leverage to increase the guarantees offered by their partners.

7. Conclusion

This paper argues that the design in DPbDD refers to the design of the processing operation. Yet, DPbDD can have an indirect influence over the design phase of technologies. This indirect influence that controllers can exert over the designers/producers need to be operationalised through the concept of leverage as developed in the field of HRDD and CSCDD.

In this sense, this paper introduces the concept of leverage as the missing step to extend the requirements of Article 25 to other actors in data value chains. In this sense, the article recommends COC, Audits and Contracts as tools to operationalise this leverage. However, these mechanisms that are crucial for Article 25 to work in practice are either not explicitly mentioned in the text of the Article or did not make through the legislative process to the final version of Article 25. For instance, reference to delegating and implementing acts, codes of conduct, and certification of IT products or services, was removed from the final text of the Regulation (EDPS Citation2015, 136).

Moreover, the concept of leverage is not a homogenous concept. This paper focuses on the so-called traditional commercial leverage, i.e. leverage through routine commercial relationships and exercised through contracts, audits, bidding criteria and incentives. Nevertheless, there are other types of leverage, such as broader business leverage (capacity building, use of international and industry standards), leverage exercised together with business partners (driving shared requirements of suppliers and bilateral engagement with peer companies), leverage through bilateral engagement (engaging multiple actors holding different parts of a solution), and leverage through multistakeholder collaborations (using convening power to address systemic issues). The focus on traditional commercial leverage seemed the most relevant for data value chains.

In conclusion, for DPbDD to provide meaningful protection and the embedding of data protection into the technological infrastructures, the concept of controllers leverage needs to be further developed with help of practical and functional tools. Only then, DPbDD can successfully target the design of technologies and offer a more holistic protection of personal data.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank for their thoughtful insights and comments the participants of the BILETA 2023 Conference and the Privacy Law Scholars Conference 2023 (Lausanne) where earlier iterations of this idea and paper were presented. The author is thankful to her supervisors Jeanne Mifsud Bonnici and Evgeni Moyakine for their invaluable guidance. Additionally, sincere appreciation goes to the anonymous reviewers for their insightful input and to her colleague, Ida Varosanec, for her collaborative spirit.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 As the legal obligation under Article 25 is imposed only on data controllers who are not always the designers of the technologies used to process personal data but users.

2 See, for instance, Article 28(1) extending DPbDD requirements to processors and Recital 78 to producers of the products, services, and applications. Recital 78 is more explicit in stating that producers should be encouraged to follow data protection requirements as this would help controllers and processors to comply with the GDPR.

3 The concept of HRDD was introduced in the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, endorsed by the UN Human Rights Council in 2011 as a comprehensive and proactive approach to address and mitigate risks linked to the activity of multinational corporations.

4 It should be noted that in the event a controller designs and develops the technology to be used in the processing of personal data, they are required under Article 25 to follow a DPbDD approach in the development of that technology, whereas, if a controller procures the technology from a third-party, the obligation to comply with DPbDD only requires the controller to ensure that the product is compliant. This lack of homogeneity on the application of DPbDD obligations is likely to create legal uncertainty and could become a possible means to circumvent the requirements of Article 25.

5 Article 32(1) GDPR relates to the security of the processing and requires controllers and processors ‘(…) to implement technical and organisational measures to ensure a level of protection appropriate to the risk (…)’.

6 The EDPS recommended still that the legislator must, in addition to the Article 26(1) (current Article 28(1) GDPR) underline the obligation of the processor (independent of the controller’s obligations) to take account the principle of data protection by design while processing personal data on behalf of the controller. Suggestion was made to add this obligation to the list of specifications contained in Article 26(2).’.

7 Based on the principle of legal certainty, ‘(t)he preamble to a Community act has no binding legal force and cannot be validly relied on either as a ground for derogating from the actual provisions of the act in question or for interpreting those provisions in a manner clearly contrary to their wording.’

8 Klitou wrote (with regards to Article 17 of Directive 95/46/EC, which similarly to Article 25 GDPR, does not apply to the developers/manufacturers) that data controllers can put pressure on ICT manufacturers to develop privacy-friendly technologies, but this has proven to be insufficient.

9 According to the EDPS, PbD is an element of accountability which requires data controllers to also demonstrate compliance where appropriate.

10 The legal obligations resulting under Article 25 are a crucial element of the principle of accountability found in Article 5(2) and Article 24 GDPR.

11 The proposals of the Commission and Council respectively limited the scope for the obligations to controllers only.

12 The concept of HRDD was then incorporated into the OECD Guidelines for multinational enterprises (2011), with set of recommendations on responsible business conduct, as well as specific OECD due diligence guidance for responsible business conduct (2018) and OECD sectoral guidance.

13 Both DPbDD and CSDD require the adoption of appropriate measures that are commensurate with the degree of severity and the likelihood of the risk or adverse impact, respectively. In CSDD, the measures depend on what is reasonably available to the company considering specific circumstances, including characteristics of the economic sector, nature of the specific business relationship and the company’s influence, and the need to ensure prioritisation of action. In DPbDD, the measures must be adopted by taking into account the list of contextual factors listed in Article 25(1) ‘the state of the art, the costs of implementation and the nature, scope, context and purposes of processing as well as the risk of varying likelihood and severity for the rights and freedoms of natural persons.

14 Guiding Principle 19(b)(ii) provides that the determination of appropriate action by a business enterprise will depend on the extent of leverage that the enterprise can exercise in addressing the adverse impact.

15 The Global Compact developed a model to visualise SOI with the help of five concentric circles mapping different stakeholders in a company’s value chain with employees in the innermost circle, followed by suppliers in the next circle, and then the marketplace, the community, and governments in the following circles. This model is based on the idea that a business enterprise can influence actions outside of their organisational boundaries through their relationships with other actors, but the influence diminishes as one moves outward from the centre.

16 The notion was based on the assumption that every organisation has a zone within which it has significant influence over social or environmental conditions, and outside of which it does not.

17 See, for instance, Principle 2 of the United Nations Global Compact, which states that ‘Businesses should make sure that they are not complicit in human rights abuses’ and explains complicity as ‘(…) being implicated in a human rights abuse that another company, government, individual or other group is causing.’

18 Article 28(3)(h) GDPR requires processors to comply with audits and inspections conducted by the controller or on their behalf, Article 28(3) GDPR states that processors must be bound by a written agreement stipulating different elements pertaining to the processing operation, and Article 40 GDPR encourages the drawing up of codes of conduct by member states, supervisory authorities, the Board and the Commission.

19 In the context of responsible business conduct and business ethics, CoC could be either sector specific or limited to a single business entity. In the latter case, they constitute tools for outlining and promoting the values and principles an organisation adheres to, to their internal and external partners. These codes are not subject to special rules on their elaboration or adherence. This is different from the CoC in the GDPR (Article 40(1) GDPR) which could be sector specific or for specific processing activities and follow an elaborate regime pertaining to their drawing up and approval. This section draws from best practices in the field of responsible business conduct and proposes to transpose them in the field of data protection. In this sense, the meaning of CoC encompasses the possibility for a controller to adhere to a CoC or to adopt an instrument specific to their organisation highlighting their values, commitments and policies with regards to responsible processing of personal data.

20 CSR is defined as ‘a concept whereby companies integrate social and environmental concerns in their business operations and in their interaction with their stakeholders on a voluntary basis’.

21 This is also confirmed in A29WP guidelines on data protection officers which state that the compliance with the GDPR can be facilitated (by the DPOs) through the implementation of accountability tools, such as audits.

22 According to Article 28(3)(h), as part of the contractual provisions of the processing agreement, a processor can be required to provide to the controller all information which is necessary in demonstrating compliance and in carrying out audits and inspections by the controllers or third-party auditors mandated by the controllers.

References

- A29WP (Article 29 Data Protection Working Party). 2010. “Opinion 1/2010 on the Concepts of ‘Controller’ and ‘Processor’”. https://ec.europa.eu/justice/article-29/documentation/opinion-recommendation/files/2010/wp169_en.pdf

- A29WP (Article 29 Data Protection Working Party). 2014. “Opinion 8/2014 on Recent Developments on the Internet of Things”. https://ec.europa.eu/justice/article-29/documentation/opinion-recommendation/files/2014/wp223_en.pdf

- A29WP (Article 29 Data Protection Working Party). 2016. (Article 29 Data Protection Working Party) “Guidelines on Data Protection Officers”. https://ec.europa.eu/information_society/newsroom/image/document/2016-51/wp243_en_40855.pdf?wb48617274 = CD63BD9A

- A29WP (Article 29 Data Protection Working Party) and WPPJ (Working Party on Police and Justice). 2009. “The Future of Privacy. Joint contribution to the Consultation of the European Commission on the legal framework for the fundamental right to protection of personal data”. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/justice/article-29/documentation/opinion-recommendation/files/2009/wp168_en.pdf

- AEPD (Agencia española proteccion datos) (DPA Spain). 2021. Procedure no.: PS/00059/2020 18 May 2021. https://www.aepd.es/informes-y-resoluciones/resoluciones?search_api_fulltext = PS%2F00059%2F2020&sort_bef_combine = fecha_firma_DESC

- Blecher, L. 2017. “Codes of Conduct: The Trojan Horse of International Human Rights law.” Comparative Labor Law & Policy Journal 38 (3): 462–464.

- Bomann-Larsen, L. 2014. Responsibility in World Business: Managing Harmful Side-Effects of Corporate Activity. Tokyo: UN University Press.

- Bonnitcha, J., and Robert McCorquodale. 2017. “The Concept of ‘Due Diligence’ in the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.” European Journal of International Law 28 (3): 899–919. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejil/chx042.

- Bygrave, L. A. 2017. “Data Protection by Design and by Default: Deciphering the EU’s Legislative Requirements.” Oslo Law Review 4 (2): 105–120. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.2387-3299-2017-02-03

- Bygrave, L. A. 2020. “Article 25 Data Protection by Design and by Default.” In The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR): A Commentary, edited by C. Kuner et al., 571–581. UK: Oxford University Press.

- Bygrave, L. A. 2022. Security by Design: Aspirations and Realities in a Regulatory Context.” Accepted for publication in Oslo Law Review 8 (3): Research Paper No. 2022-44.

- Bygrave, L. A., Luca Tosoni, et al. 2020. “Article 4(7) Controller.” In The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR): A Commentary, edited by C. Kuner, 145–156. UK: Oxford University Press.

- Cafaggi, F. 2013. “The Regulatory Functions of Transnational Commercial Contracts: New Architectures.” Fordham Int'l LJ 36: 1557.

- Cavoukian, A. 2009. “Privacy by Design: The 7 Foundational Principles: Implementation and Mapping of Fair Information Practices.” https://iab.org/wp-content/IAB-uploads/2011/03/fred_carter.pdf

- Cavoukian, A., S. Taylor, and M. E. Abrams. 2010. “Privacy by Design: Essential for Organizational Accountability and Strong Business Practices.” Identity in the Information Society 3 (2): 405–413. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12394-010-0053-z

- Commission of the European Communities. 2001. “Green Paper: Promoting a European Framework for Corporate Social Responsibility” COM (2001) 366 final (July 18, 2001). https://www.europarl.europa.eu/meetdocs/committees/deve/20020122/com(2001)366_en.pdf

- Dahi, A., and Marcelo Corrales Compagnucci 2022. “Device Manufacturers as Controllers – Expanding the Concept of ‘Controllership’ in the GDPR.” Computer Law & Security Review 47: 105762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clsr.2022.105762.

- Docksey, C. 2020. “Article 24 Responsibility of the controller”. In The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR): A Commentary, edited by C. Kuner et al., 550–570. UK: Oxford University Press.

- EDPB (European Data Protection Board). 2020a. “Guidelines 4/2019 on Article 25 Data Protection by Design and by Design” (version 2.0 adopted on 20 October 2020). https://edpb.europa.eu/sites/default/files/files/file1/edpb_guidelines_201904_dataprotection_by_design_and_by_default_v2.0_en.pdf.

- EDPB (European Data Protection Board). 2020b. “Guidelines 07/2020 on the Concepts of Controller and Processor in the GDPR” (version 2.1. adopted on 7 July 2021). https://edpb.europa.eu/system/files/2023-10/EDPB_guidelines_202007_controllerprocessor_final_en.pdf.

- EDPS (European Data Protection Supervisor). 2012. “Opinion on the Data Protection Reform Package”. https://edps.europa.eu/sites/edp/files/publication/12-03-07_edps_reform_package_en.pdf.

- EDPS (European Data Protection Supervisor). 2015. “Annex to Opinion 3/2015: Comparative table of GDPR texts with EDPS recommendations.” https://edps.europa.eu/sites/edp/files/publication/15-07-27_gdpr_recommendations_annex_en_1.pdf.

- Eijsbouts, J. 2017. “Corporate Codes as Private Co-Regulatory Instruments in Corporate Governance and Responsibility and their Enforcement.” Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies 24 (1): 181–205. https://doi.org/10.2979/indjglolegstu.24.1.0181

- European Commission. 2010. “A Comprehensive Approach on Personal Data Protection in the European Union” (COM(2010) 609 final), 4.11.2010. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri = COM:2010:0609:FIN:EN:PDF

- European Commission. 2012. “Impact Assessment Accompanying the document Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data (General Data Protection Regulation) and Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data by competent authorities for the purposes of prevention, investigation, detection or prosecution of criminal offences or the execution of criminal penalties, and the free movement of such data” (SEC(2012) 72 final) 25.1.2012. https://europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/59702/att_20130508ATT65856-1873079025799224642.pdf.

- European Commission. 2022. “Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence and amending Directive (EU) 2019/1937”, 2022/0051(COD) (Proposed CSDD Directive). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri = CELEX%3A52022PC0071.

- European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS). 2011. “Opinion on the Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions – ‘A comprehensive approach on personal data protection in the European Union.”

- European Parliament. 2011. “European Parliament resolution of 6 July 2011 on a comprehensive approach on personal data protection in the European Union” (2011/2025(INI)). https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-7-2011-0323_EN.pdf.

- Friedman, B., David G. Hendry, and Alan Borning. 2017. “A Survey of Value Sensitive Design Methods.” Foundations and Trends® in Human–Computer Interaction 11 (2): 63–125. https://doi.org/10.1561/1100000015

- Hartzog, W. 2018. Privacy’s Blueprint: The Battle to Control the Design of New Technologies. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Hildebrandt, M., and Laura Tielemans. 2013. “Data Protection by Design and Technology Neutral Law.” Computer Law & Security Review 29 (5): 509–521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clsr.2013.07.004

- Jasserand-Breeman, C. 2019. “Reprocessing of Biometric Data for Law Enforcement Purposes: Individuals’ Safeguards Caught at the Interface between the GDPR and the ‘Police’ Directive?.” Dissertation, University of Groningen.

- Klitou, D. 2011. “Privacy by Design and Privacy-Invading Technologies: Safeguarding Privacy, Liberty and Security in the 21st Century.” Legisprudence 5 (3): 297–330. https://doi.org/10.5235/175214611799248904

- Latour, B. 2010. “A Cautious Prometheus? A Few Steps Toward a Philosophy of Design (with Special Attention to Peter Sloterdijk).” In Networks of Design: Proceedings of the 2008 Annual International Conference of the Design History Society, edited by F. Hackney, J. Glynne, and V. Minto, 2–10. Universal Publishers.

- Michelakaki, C., and Barros Vale. 2023. Unlocking Data Protection by Design & By Default: Lessons from the Enforcement of Article 25 GDPR. Future of Privacy Forum. https://fpf.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/FPF-Article-25-GDPR-A4-FINAL-Digital.pdf.

- Rogge, A. 2020. “Audits and Reporting Schemes: A Business Case for Human Rights Due Diligence.” ANU College of Law, 13 November 2020. https://law.anu.edu.au/news-and-events/news/audits-and-reporting-schemes-business-case-human-rights-due-diligence.

- Sherman III, John F. 2021. “Irresponsible Exit: Exercising Force Majeure Provisions in Procurement Contracts” Business and Human Rights Journal 6 (1): 127–134. https://doi.org/10.1017/bhj.2020.27

- Shift. 2012. “Respecting Human Rights Through Global Supply Chains”, Shift Workshop Report No. 2. https://www.hks.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/centers/mrcbg/programs/cri/files/Shift-Workshop-Report-2_Respecting-Human-Rights-Through-Global-Supply-Chains.pdf.

- Smit, L., Gabrielle Holly, Robert McCorquodale, and Stuart Neely. 2021. “Human Rights Due Diligence in Global Supply Chains: Evidence of Corporate Practices to Inform a Legal Standard.” The International Journal of Human Rights 25 (6): 945–973. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642987.2020.1799196

- Sorell, T. 2005. “Business and Human Rights.” In Human Rights and the Moral Responsibilities of Corporate and Public Sector Organisations, edited by T. Campbell, and Seumas Miller, 129–143. Dordrecht: Springer.

- UN Human Rights Council. 2007. “Report of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on the issue of human rights and transnational corporations and other business enterprises, John Ruggie* Business and human rights: mapping international standards of responsibility and accountability for corporate acts” (19 February 2007), UN Doc. A/HRC/4/35. https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/g07/108/85/pdf/g0710885.pdf?token = tXcGGGTmr17rcP98Xa&fe = true.

- UN Human Rights Council. 2008. Clarifying the Concepts of ‘Sphere of Influence’ and ‘Complicity’, UN Doc. A/HRC/8/16. https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/g08/134/78/pdf/g0813478.pdf?token = XKZbtq0O3D3xrz8dtO&fe = true.

- UN Human Rights Council. 2011. Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights: Implementing the United Nations ‘Protect, Respect and Remedy’ Framework (UNGP 2011), UN Doc. A/HRC/17/31). https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/g11/121/90/pdf/g1112190.pdf?token = dE4bLLpZOHEOKLg8vF&fe = true.

- Van Alsenoy, B. 2017. “Liability under EU Data Protection Law: From Directive 95/46 to the General Data Protection Regulation.” Journal of Intellectual Property, Information Technology and E-Commerce Law 7 (3): 271–288.

- Van Mil, J., and J. P. Quintais. 2022. “A Matter of (Joint) Control? Virtual Assistants and the General Data Protection Regulation.” Computer Law & Security Review 45 (105689) . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clsr.2022.105689.

- Waldman, A. E. 2018. “Privacy’s Law of Design.” UC Irvine Law Review 9 (5): 1239–1288.

- Wood, S. 2012. “The Case for Leverage-Based Corporate Human Rights Responsibility.” Business Ethics Quarterly 22 (1): 63–98. https://doi.org/10.5840/beq20122215

- Legislation

- Regulation (EU). 2016/679. Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC: General Data Protection Regulation. Consolidated version. Data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/2016-05-04.

- Case law (in chronological order)

- European Court of Justice

- Judgment of 25 November 1998. Giuseppe Manfredi v Regione Puglia (Manfredi). Case C-308/97 ECLI:EU:C:1998:566.

- Judgment of 24 November 2005. Deutsches Milch-Kontor GmbH v Hauptzollamt Hamburg-Jonas (Deutsches Milch-Kontor), Case C-136/04, ECLI:EU:C:2005:716.

- Judgment of 2 April 2009. Hauptzollamt Bremen v. J. E. Tyson Parketthandel GmbH hanse j. (Hauptzollamt Bremen), C-134/08 ECLI:EU:C:2009:229.

- Judgment of 13 May 2014. Google Spain SL and Google Inc. v Agencia Española de Protección de Datos (AEPD) and Mario Costeja González (Google Spain), Case C-131/12, ECLI:EU:C:2014:317.

- Judgment of 5 June 2018. Unabhängiges Landeszentrum für Datenschutz Schleswig-Holstein v. Wirtschaftsakademie Schleswig-Holstein GmbH (Wirtschaftsakademie), C-210/16 EU:C:2018:388.

- Judgement of 10 July 2018. Tietosuojavaltuutettu v Jehovan todistajat — uskonnollinen yhdyskunta (Jehovan todistajat), C-25/17 ECLI:EU:C:2018:551

- Decisions of Data Protection Authorities

- UODO (Urzędu Ochrony Danych Osobowych) (DPA Poland), DKN.5130.1354.2020, 17 December 2020, (Available at https://uodo.gov.pl/decyzje/DKN.5130.1354.2020 )

- GPDP (Garante Per La Protezione Dei Dati Personali) (DPA Italy). 2020. “Injunction order against Wind Tre SpA”, 9 July 2020 [doc. web no. 9435753] https://www.gpdp.it/web/guest/home/docweb/-/docweb-display/docweb/9435753

- AEPD (Agencia española proteccion datos) (DPA Spain), 2021. Procedure no.: PS/00059/2020 18 May 2021. https://www.aepd.es/informes-y-resoluciones/resoluciones?search_api_fulltext = PS%2F00059%2F2020&sort_bef_combine = fecha_firma_DESC

- GPDP (Garante Per La Protezione Dei Dati Personali) (DPA Italy). 2021. “Injunction order against Atac spa” 22 July 2021 [doc. web no. 9698597], (Available at https://www.garanteprivacy.it/home/docweb/-/docweb-display/docweb/9698597).

- UODO (Urzędu Ochrony Danych Osobowych) (DPA Poland), DKN.5130.2215.2020, 22 January 2022, (Available at https://uodo.gov.pl/decyzje/DKN.5130.2215.2020).