ABSTRACT

This paper expands debates on disability and education by focusing on issues of prevalence and examining loss of formal learning when schools were closed for extended periods in Ethiopia as a result of COVID-19. Using data collected during two academic years, before the pandemic in 2018–2019 and after the schools reopened in 2020–2021, results show an increased prevalence of disability among children in grades 1 and 4, as identified through the Washington Group Child Functioning Module. In addition, we found some evidence of loss in foundational numeracy for children with disabilities in these grades, but the extent of this loss depends on whether children were reported as having mild or moderate to severe disabilities. Taken together, results show that COVID-19 and the accompanying school closures were likely to have affected both the prevalence of disability and learning for children with disabilities, highlighting the need for a careful exploration of changing student needs as a result of the pandemic.

Introduction

As COVID-19 spread across the globe, the United Nations released in May 2020 a policy brief titled, ‘A Disability-Inclusive Response to COVID-19’ to ensure that disability was central in the response of government and other actors to the impacts of the pandemic. It noted how the pandemic was ‘deepening pre-existing inequalities, exposing the extent of exclusion and highlighting that work on disability inclusion is imperative’ (United Nations Citation2020, 2). Similar concerns were raised by the Pivoting to Inclusion: Leveraging Lessons from the COVID-19 Crisis for Learners with Disabilities, an Issues Paper released by the World Bank (Mcclain-Nhlapo et al. Citation2020), which stated that, ‘children with disabilities are among the most vulnerable – facing multiple forms of exclusion linked to education, health, gender equity, and social inclusion. Those living in poverty are at risk of further marginalization’.

COVID-19 and education of children with disabilities

Focusing on the experiences of Ethiopian youth (aged 15–24 years) with physical and visual disabilities, Emirie et al. (Citation2020) highlighted the multidimensional vulnerabilities experienced by these youth during the pandemic Their findings underscore that many young people with disabilities remained excluded from any kind of social safety net, especially when school-related social protection was suspended during closures. Mbazzi et al. (Citation2021) in the context of Central Uganda, highlighted the significant impact of lockdown measures on children with disabilities and their families resulting in negative effect on their mental and physical health, social life, finances, education and food security. Similarly, in a research project where data were collected with parents of children with disabilities across, Ethiopia, Nepal and Qatar (Singal, Taneja-Johansson et al. Citation2021), parents noted significant loss of structure in their child’s day and loneliness arising from lack of contact with their friends, significantly reduced opportunities for learning, all of which had an impact on the child’s well-being and also that of the wider family.

Although many countries implemented distance learning solutions during the COVID-19 school closures, students with disabilities are least likely to benefit from those learning modalities (United Nations Citation2020). Issues to do with lack of support to engage in learning, access to the internet, accessible software and learning materials further deepen the gap for students with disabilities, as identified in Sri Lanka (Wijesinghe Citation2020), Malawi (Singal, Mbukwa-Ngwira et al. Citation2021) and Nepal (Singal, Taneja-Johansson, and Poudyal et al. Citation2021).

Mcclain-Nhlapo et al. (Citation2020) extend this argument further by noting how prolonged school closures not only impact learning, but also result in the loss of essential services for many children with disabilities, such as physiotherapy, medical check-ups, nutritional supplements which in many countries are delivered through schools. Such concerns about the magnified impact of the negative consequences of COVID-19 were documented in the research literature. Most of these studies drew primarily on surveys and interviews with families, teachers, adults with disabilities, and sometimes, children with disabilities, about their experiences during the pandemic. The focus on the impact of the pandemic as schools re-opened is starting to emerge and is the topic of this paper.

While the focus of these papers is on the experiences of children with disabilities during the pandemic, they do not consider whether the pandemic itself may have impacted everyday functioning domains in children, and neither do they quantify learning outcomes and the potential impact of the disability on academic attainment. The two main aims of this paper are: (1) to examine changes in the incidence of reported disabilities among children attending school both before and after the pandemic using the Washington Group (WG) Child Functioning Module (CFM); and (2) to compare the performance of children identified as having disabilities with their peers without disabilities on numeracy test scores before and after the pandemic.

Persons with disabilities in Ethiopia

Persons with disabilities constitute 15% of the global population (about one billion people) (WHO and World Bank Citation2011). UNICEF (Citation2019), in their analysis using survey data from 2015/2016, noted that nearly 7.8 million people in Ethiopia live with some form of disability, or 9.3% of the country’s total population. In the 2007 Population and Housing Census, Ethiopian Central Statistical Authority (Citation2012) reported that there were less than 1 million Ethiopians with disability, i.e. 1.2%. These figures are indicative of the ‘highly fragmented or sometimes misleading and contradictory data on persons with disabilities in Ethiopia’ (Abebe et al. Citation2021, 3). The difficulties in measurement, both globally and in Ethiopia, can be attributed to definitions used, question design, reporting sources, data collection methods, expectations of functioning and training of enumerators (WHO and World Bank Citation2011) and indeed are also influenced by socio-cultural determinants in reporting patterns (Teferra Citation2001).

People with disabilities continue to be among the most marginalised groups in Ethiopia. Working with data collected through the Health and Demographic Surveillance System (HDSS) in northwest Ethiopia, Chala et al. (Citation2017) conclude that there is a significant association of disability with age, wealth status, food security status, marital and occupational status. The association between poverty and disability is well documented in many other parts of the world (Mirta, Posarac, and Vick Citation2011). For this reason, persons with disabilities have been acknowledged as a significant group needing attention in Ethiopian policy. Ethiopia ratified the UNCRPD in 2010 and is on track with its treaty-reporting obligations to the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. The Growth and Transformation Plan for 2010–2015 was the first to identify disability as a cross-cutting issue, while the National Plan of Action for the Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities adopted in 2012 provides an ambitious policy framework that aims to mainstream disability issues in all fields of society by 2021. The National Social Protection Policy (Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs Citation2012) also calls for the expansion of services for persons with disabilities.

Education of children with disabilities in Ethiopia

The Constitution, in Article 41(3, 5) stipulates ‘the right of citizens to equal access to publicly funded services, and the government shall within available means, allocate resources to provide rehabilitation and assistance to the physically and mentally disabled’. The current Special Needs/Inclusive Education StrategyFootnote1 (Ministry of Education Citation2012) and the Fifth Education Sector Development Programme (ESDP V/2015/16 to 2019/20) highlight a significant focus on persons with disabilities. The 10-year Master Plan for Special Needs/Inclusive Education in Ethiopia, 2016–2025 (Ministry of Education Citation2016), and the Ethiopian Education and Training Road Map 2018–2030 (Teferra et al. Citation2018) are also aligned with the UN Sustainable Development Goals, particularly Goal 4, 2015–2030.

Despite the centrality of people with disability in Ethiopian policy, children with disabilities are still lagging with respect to many educational indicators. Less than 1% of children with disabilities have access to pre-primary education (Ministry of Education Citation2018), only 11.1% of the estimated population of children with disabilities are enrolled in primary school and 2.8% in secondary education (Ministry of Education 2019). As we progress through the education system, the rates of enrolment for children with disabilities decreases dramatically (AUTHORS). According to figures available on the Disability Data Portal developed in 2021 and hosted by Leonard Cheshire, primary school completion rates for persons with disabilities is 14% (in comparison to 27% for those without disabilities), and this comes down to 3.5% in relation to secondary school completion rates (in comparison to 8.1% in comparison to those without disabilities). While school completion and quality of education remain of considerable concern for all children in Ethiopia (Iyer et al. Citation2020; Woldehanna, Araya, and Gebremedhin Citation2016), it is further magnified for children with disabilities.

Educational exclusion of children with disabilities from and within the system results largely from the lack of adaptable study materials, limited pedagogical approaches adopted in classrooms, inadequate financing mechanisms; poor infrastructure, and the absence of a clear structure for coordination and administration of special and inclusive education (Buchner and Thompson Citation2021; Ginja and Chen Citation2023). Furthermore, many teachers regard teaching children with disabilities as burdensome and unrewarding (Beyene and Tizazu Citation2010). This has resulted in some researchers regarding children with disabilities as facing ‘disguised exclusion’ in teaching and learning processes (Teferra Citation2001).

Research questions

This paper draws on findings from analysis of two large-scale cross-sectional data collected for different cohorts of children attending grades 1 and 4 in the same schools but in two different academic years. The questions we aim to address are:

What are the changes in the incidence of mild, and moderate to severe disabilities for children attending grades 1 and 4 between the academic years 2018–2019 and 2020–2021?

What is the difference in formal numeracy achievement in grades 1 and 4, for children with and without disabilities, between the academic years 2018–2019 and 2020–2021 (both absolute and relative differences)?

The analysis is specifically focused on children who were attending mainstream government schools in both time periods and does not include those in special schools, special units in the mainstream schools, or those out of school. We use results from numeracy assessments given to children in these schools to establish changes over time. We hypothesise that changes in disability prevalence could be attributed to the increased difficulties in accessing health care, lack of nutrition and other services during the pandemic. Similarly, we argue that changes in numeracy scores are likely to result from suspension of formal learning due to unplanned school closures lasting for seven months.

Methodology

We use two sources of data: one collected during the academic year 2018–2019 and the other during 2020–2021.

First set of data: In 2018–2019, over 8000 children from grades 1 and 4 attending 168 schools in 7 regions of Ethiopia were selected to support the Research for Improving Systems of Education (RISE) Ethiopia project. Through a household survey, the main caregiver of each of these children completed the CFM developed by the WG on Disability Statistics. This enabled us to capture information about the prevalence of reported disabilities among grade 1 and grade 4 children, and link this to achievement in numeracy, which was collected by using a numeracy test given to children during their school day.

Second set of data: In 2020–2021, using the same schoolsFootnote2 as above, information was collected on two new cohorts of children in grade 1 and grade 4. Data were collected from over 7500 children who returned to school in December. During school, these children were given the same formal numeracy test previously used in 2018–2019. In addition, their caregivers were asked to complete the WG CFM.

These two sources of data enable us to capture the prevalence of disabilities among grade 1 and grade 4 children in 2018–2019 and in 2020–2021. We can also estimate changes in formal numeracy achievement between 2018–2019 (prior to the pandemic) and in 2020–2021 (after children return to school). It is important to note that we were allowed by the Ministry of Education to collect data only after children had completed the 45-days catch-up classes, which aimed to cover aspects of the curriculum that had been missed during school closures. Hence our results are likely to be influenced by this period of learning and it should be considered when interpreting the findings.

Using the child functioning module for the identification of children with disabilities

As noted earlier, gathering data on disability prevalence is rather problematic due to issues of definition and sensitivity of disclosure in many settings (Madans, Mont, and Loeb Citation2015). Questions on disability developed by the WG on Disability, a United Nations sponsored City Group commissioned in 2001, represent the most recent thinking around disability and draw support from the UNCRPD. Persons with disabilities are defined to ‘include those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others’ (UNCRPD Citation2010, 4). The CFM developed in 2009 in partnership with UNICEF specifically focuses on children between the ages of 5 and 17 years, ‘aims at capturing activity limitations that, in an unaccommodating environment, would place a child at higher risk of participation restrictions than children without similar limitations’ (Cappa et al. Citation2018).

We use the terms ‘mild disability’ and ‘moderate/severe disabilities’ to emphasise the differences in reported functioning among the two groupings. It is also important to reiterate here that while we use the term ‘disability’ this is no way a medical diagnosis. As the WG acknowledges depending on the purpose of the survey, medical identification should be followed if giving a diagnosis is the main aim.

The primary purpose of the questions in the module is to identify the extent to which children face difficulties in the following 13 domains: seeing, hearing, walking, self-care, understanding of child’s speech (within and outside the household), learning, remembering, controlling behaviour, focusing, routine (accepting changes), making friends and being worried or sad. Doing so is important as these functional difficulties may place children at risk of experiencing limited participation in an unaccommodating environment, when compared to other children without these functional difficulties. The experience of the pandemic, changes in routines, social relations, being at home, could increase the prevalence of some of these difficulties among children.

All child questions in the WG module are meant to be asked of parents or primary care givers. In order to reference and focus the respondents on the functioning of their own child in reference to that child’s cohort, where appropriate, the questions are phrased with the clause: ‘compared with children of the same age … ’ (The Washington Group/UNICEF CFM Citation2020). Moreover, given that disability is conceptualised on a continuum from minor difficulties in functioning to major impacts on a person’s life, the answer categories are designed to reflect this continuum. The response categories for the majority of the domains are:

No difficulty

Some difficulty

A lot of difficulty

Cannot do at all

The cut off for analysis can vary according to the purpose of the survey (Madans, Mont, and Loeb Citation2015). The questions developed by the WG both are intended to be simple to administer and do not raise concerns of stigmatisation as they do not require respondents to label themselves or others as disabled (Groce and Mont Citation2017). Furthermore, the questions provide the opportunity for international comparability, and have been developed using a rigorous methodology. The WG questions are gaining a lot of international currency for their ease of use. In 2016 the adult questions were incorporated in panel data for the Living Standards and Measurement Surveys (LSMS) in Ethiopia (The Washington Group Citation2016).

Numeracy tests: what was assessed?

Grade 1 numeracy test was adapted from the Measuring Early Learning Quality and Outcomes (MELQO) direct assessment tests. The MELQO test is designed to promote feasible, accurate and useful measurement of pupils’ development and learning at the start of primary school (for detailed information about the MELQO test, see UNESCO, UNICEF, Brookings Institution & World Bank Citation2017). For the RISE Ethiopia project, the MELQO test was piloted with a total of 1144 students (571 in O-class, 573 in grade 1) in 2018 across six regions (Amhara, Benishangul-Gumuz, Oromia, SNNPR, Somali and Tigray). Based on an item-level analysis, seven out of eight direct assessment numeracy exercises were selected for use for grade 1 pupils for the RISE Ethiopia project in the academic year 2018–2019. The same MELQO test was administered for grade 1 pupils during the academic year 2020–2021 survey.

The grade 4 numeracy test for RISE Ethiopia was adapted from the grade 4 maths test from the Young Lives Ethiopia School Survey conducted in 2012–2013 (for detailed information on the test, see James Citation2014). The test for numeracy was revised and updated in February 2018, following guidance by test developers from the Ministry of Education and the National Educational Assessment and Examinations Agency (NEAEA). The final test included 25 items which were administered at the beginning of the 2018–2019 academic year. The exact same test was also administered for grade 4 pupils at the beginning of the 2020–2021 academic year.

There were no particular adaptations made on the test items for children with disabilities as these were unknown to the enumerators at the time of data collection. Because there is direct comparison between these two tests within grade, we present the percent of correct responses achieved by children as a measure of formal numeracy attainment and we obtain this depending on whether children were reported with mild or moderate to severe disabilities.

Other confounding factors

In addition to estimating the changes over time in the incidence of disability as well as changes in formal numeracy for children with and without disabilities, we also include several important indicators which are related to these factors (Mizunoya, Mitra, and Yamasaki Citation2018; Takeda and Lamichhane Citation2018). These are sex of the child, as well as age, which capture both binary gender aspects and developmental stages of children. We also included a report by the main caregiver in terms of the health status of the child. The question given to the main caregiver was In general, how would you describe the child’s health. These responses were classified into poor, average, good and very good. We also include two indicators related to the child’s schooling. The first captures whether the child had attended pre-school, which again is important in terms of measuring numeracy and it is related to the likelihood (or rather unlikelihood) of children with disabilities accessing pre-school opportunities. The second is whether the child received meals at school, which is an important indicator of disadvantage as well as social protection in Ethiopia, both of which are related to disability status as well as numeracy achievement.

In addition to child-level factors, we also include indicators which are measured at the level of the household. These indicators are related to resources, human capital, wealth and services, as well as the distribution of resources. These indicators are important as they help to account for factors related to numeracy achievement and disability status which are beyond the child. Among the household level indicators, we include household size and a wealth index made of a combination of durable goods, housing quality and access to services such as water and electricity in the household. The wealth index ranges from 0 to 1, and it is a measure of the proportion of durable goods owned by the household, the quality of the housing measured by 4 items and access to services measured by water, sanitation, electricity and cooking fuel. For the education of the main caregiver, we include a measure of the ability of the caregiver to read a sentence. During data collection, a short sentence, in the local language, was given to the main caregiver. Based on their ability to read, caregivers were classified as unable to read, able to read part of a sentence or able to read a whole sentence. Finally, we include regional controls (across the 6 regions where our sample schools were located) to partially condition out for the diverse sociocultural contexts within Ethiopia. shows descriptive statistics for all these factors by academic year and prevalence of disability identified in children.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics iIncidence of disabilities, numeracy and confounding factors.

Analytical approach

In order to estimate changes in the incidence of disability over the two time periods, we employed multinomial logistic regression. Specifically, we estimate the probability that a child has a mild or a moderate to severe disability relative to no disability conditional on the set of covariates outlined above for each academic year. Then, we compare whether the relative probability between academic years has changed. It is the comparison over time which provides us with an estimate of the changes in the incidence which we can infer were partially driven by the pandemic and school closures.

For estimates on the change in formal numeracy attainment over time, we are interested not just in the absolute change for children with disabilities but also relative to children without disabilities. In order to estimate the former, we estimate the conditional formal numeracy attainment before and after the pandemic separately for children with and without disabilities. The focus here is on whether the conditional average formal numeracy attainment has changed over the two time periods. These models are estimated using ordinary least squares regression.

To estimate the latter, i.e. relative changes over time, we estimate a system of two equations for each grade: one for children in the academic year 2018–2019 and one for 2020–2021. Each set of equations includes the covariates outlined previously and are estimated using generalised least squares (see Greene Citation1997). To estimate the relative difference in numeracy attainment within cohorts we use the Wald test to see if these differences have changed over time. As with incidence, it is the absolute and relative changes over time which provides evidence as to whether these changes may be due to the pandemic and school closures.

Results

Increased prevalence of disability among children in grades 1 and 4

Conditional changes in the prevalence of disability over the two time periods are reported in . The focus here is on measuring the difference in the prevalence of children with mild, and moderate to severe disabilities over time relative to other children, conditional on the set of covariates indicated above. Results show that children had 1.53 odds of mild disabilities relative to no disabilities during 2020–2021 relative to 2018–2019. In other words, children were 1.53 times more likely to be reported as having mild disabilities relative to no disability in 2020–2021 than in 2018–2019. For children with moderate to severe disabilities the relative odds are 1.66. Again, like children with mild disabilities, there were higher odds of reporting children as experiencing moderate to severe disabilities over time.

Table 2. Relative risk ratio estimates [standard error] for incidence of disability.

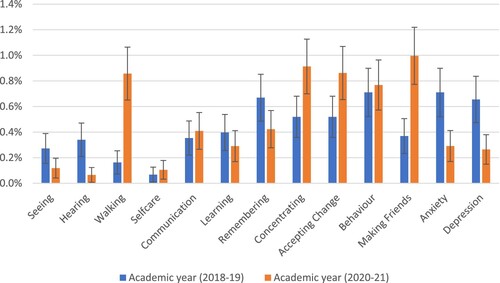

Variations according to different types of disabilities

Focusing on the 13 areas of functioning, and particularly on the incidence of moderate to severe disabilities, we found that caregivers reported a higher incidence of moderate to severe disabilities during the academic year 2020–2021 (after the schools were reopened) for concentrating, accepting change, making friends and walking (see ). There was lower incidence for hearing, anxiety and depression, with no change for other areas. While no clear patterns emerge, what is noteworthy is the increase in reporting of higher difficulties in socio-emotional aspects, such as accepting change and making friends, which could be linked with disruption in routines and the prolonged isolation from peer groups. Additionally, increased reported difficulties in concentration could be made sense of as children with disabilities were less likely to be exposed to high degree of cognitively stimulating tasks at home, due to lack of accessible materials.

Regional variations in reporting patterns

The prevalence of mild and moderate to severe disabilities by region shows large variations, as indicated in . To understand the changes better, we present the incidence of disability by region over the two time periods in . In Addis Ababa, for instance, a lower proportion of children were reported with mild as well as moderate to severe disabilities after schools reopened, compared with the situation in 2018. On the other hand, the increment in the incidence of moderate to severe disabilities in Amhara and Somali regions was substantial. The change in the reported rate of moderate to severe disabilities in Amhara was 3.77 percentage points higher in 2021 after schools reopened, compared with the situation in 2018 (difference between 7.6% in 2020–2021 compared with 3.9% in 2018–2019 – as shown in ). In Oromia, there was a slight change in the proportion of children with moderate to severe disabilities over time, but a relatively large increase in the proportion of children reported as having mild disabilities. Overall, except for children in Addis Ababa (and for mild disabilities in Somali), all other regions presented an increase in the reported incidence of disability, whether mild or moderate to severe.

Table 3. Proportion of children with disabilities in 2018–2019 and 2020–2021, by region.

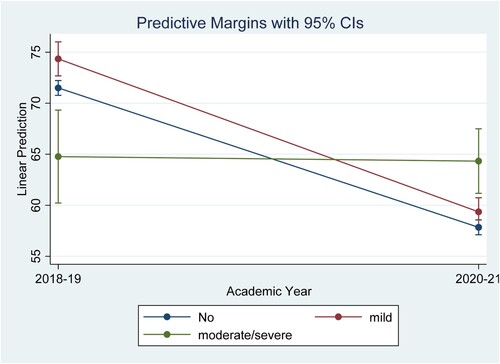

Changes in formal numeracy for children with disabilities in grade 1

In 2018–2019, as indicated in , children without disabilities achieved 70% in the numeracy test, children with mild disabilities achieved 76%, and children with moderate to severe disabilities achieved 67%. In 2020–2021, children without disabilities achieved 59%, those with mild disabilities achieved also 59% and children with moderate to severe disabilities achieved 64%. The differences in percentage points are 11.8 for children without disabilities, 16.4 for children with mild disabilities and 4.6 for children with moderate to severe disabilities. Some deeper insights emerge as we employ multivariate analysis. First, there is a clear reduction in the percentage of correct responses for all children in the 2020–2021 cohort. For children with no disabilities and using a model conditional on confounding factors and regional controls, we estimate a conditional reduction of 13.7 points (standard error = 0.55; p-value< = 0.01). For children with mild disabilities, we estimate a conditional reduction of 15 points (standard error = 1.34; p-value< = 0.01), whereas for children with moderate to severe disabilities we estimate a conditional reduction of 6.4 points (standard error = 3.55; p-value < = 0.07). This means that children in grade 1 during 2020–2021 academic year are achieving lower scores in numeracy compared with similar children in 2018–2019.

Furthermore, results show that there are no relative differences in formal numeracy reductions between children with mild disabilities and those with no disabilities. In other words, the difference between the conditional reduction of 15 points for children with mild disabilities is equivalent in statistical terms to the difference of 13.7 points for children without disabilities (Chi2 = 0.03; p-value< = 0.86). For children with moderate to severe disabilities, we found that the conditional reduction in formal numeracy achievement is less than for children without disabilities (difference between 6.4 and 13.7 points is statistically significant, Chi2 = 16.89; p-value< = 0.01). These results are presented in using the marginal change in the predicted numeracy score for grade 1 pupils over the two academic years by disability status. This means that the estimated numeracy loss for children with mild disabilities is equivalent to the one for children without disabilities. But the estimated numeracy loss for children with moderate to severe disabilities, who were attending school prior to the pandemic and returned to school, is less than for children without disabilities.

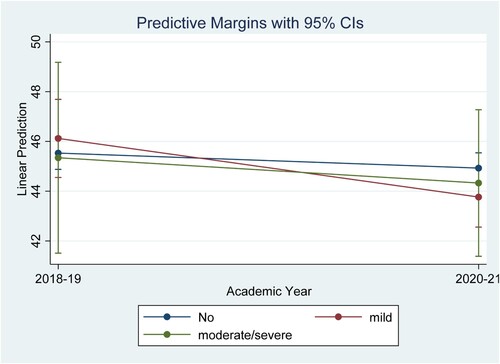

Changes in formal numeracy for children with disabilities in grade 4

Children without disabilities in grade 4 (as indicated in ) achieved 45% during the academic year 2018–2019 and the same during 2020–2021. Children with mild disabilities achieved 50% during 2018–2019 and 45% during 2020–2021, while those with moderate to severe disabilities achieved 49% during 2018–2019 and 45% during 2020–2021. For children in grade 4 we found that those with disabilities achieved lower scores after school closures compared with similar children in 2018–2019, whereas this was not the case for children without disabilities.

Using multivariate analyses, we found that the conditional reduction in numeracy scores for children with mild disabilities is 2.1 points (standard error = 1.13; p-value< = 0.6). For children with moderate to severe disabilities, the conditional numeracy change was estimated to be 1.8 points and was not statistically significant (standard error = 3.0; p-value< = 0.55). For children without disabilities, the estimated change in formal numeracy attainment of 0.75 points was not statistically significant (standard error = 0.47; p-value< = 0.11). Therefore, for grade 4 we only find numeracy loss for children with disabilities.

Our results indicate significant differences in performance on numeracy tests between children with mild disabilities compared to children without disabilities over time. The difference between the conditional reduction of 2.1 points for children with mild disabilities is larger than the difference of 0.75 point for children without disabilities (Chi2 = 4.18; p-value< = 0.04). For children with moderate to severe disabilities, we do not find the decline in numeracy scores to be statistically different from their peers who are reported as not having a disability (difference between 1.8 point and 0.75 of a point is not statistically significant, Chi2 = 0.37; p-value< = 0.54). These results are presented in using the marginal change in the predicted numeracy score for grade 4 pupils over the two academic years by disability status. Contrary to the results for grade 1, we found that children with mild disabilities show larger numeracy losses than children without disabilities over time.

Discussion and contribution

Over the last few decades, there has been a significant expansion in access to primary education in Ethiopia, however children with disabilities continue to remain excluded from and within education. Since 2018, under the GEQIP-E reform efforts, increased attention has been given to support the enrolment and learning of children with disabilities, especially in mainstream school settings. Nonetheless, the pandemic has given rise to greater urgency for more concentrated efforts to ensure that children with disabilities are not left behind in educational reform efforts.

Our findings indicate that, after schools were reopened from the COVID-19 closures, there has been an increase in the reported prevalence of disabilities among children in grades 1 and 4, among those sampled for this research. Caregivers were more likely to report their child as having ‘a lot of difficulty or cannot do at all’ on the following functional domains: concentrating, accepting change, making friends and walking. Indeed, it is difficult to establish any clear patterns from these results, however, keeping in mind that the CFM questions ‘are designed to identify a population which, due to functioning in core domains, is at risk of restricted participation in a non-accommodating environment’ (Madans, Mont, and Loeb Citation2015, 65), these findings become significant, In other words, these children were reported by their parents at being at a higher risk of participation restrictions than children without similar limitations, and in an unaccommodating school (and wider) environment were more likely to not achieve their potential.

Using the same RISE data from students enrolled in grade 4 in 2018–2019 academic, but who were followed longitudinally over the period of the pandemic, Bayley et al. (Citation2021) found that the social skills of these students declined significantly over the period of the COVID-related school closures. In particular, students who expressed agreement with statements like I feel confident talking to others and I make friends easily in 2019 did not necessarily agree with them in 2021, which is consistent with the increased severity of incidence in the following two functioning domains ‘accepting change’ and ‘making friends’ shown in . We postulate that this increase in reporting of higher difficulties in socio-emotional aspects, such as accepting change and making friends, can be linked with disruption in routines and the prolonged isolation from peer groups, given that school closures were unplanned and abrupt and lasted for seven months.

Additionally, increased reported difficulties in concentration could be made sense of as children with disabilities were less likely to be exposed to high degree of cognitively stimulating tasks at home, due to lack of accessible materials. This issue of lack of accessible and adaptable teaching and learning materials was highlighted by parents and teachers of children with disabilities (AUTHORS). Both these issues raise important concerns as schools reopen and highlight the importance of nurturing children’s socio-emotional wellbeing (Bayley et al. Citation2021). The negative impact of COVID-19 and of quarantining on the mental health and well-being of children and young people (aged 12–25 years) with disabilities has also been noted in a cross cultural study in Zambia and Sierra Leone (Sharpe et al. Citation2021)

Additionally, our results indicate that there is formal numeracy loss experienced by those children identified as having mild and moderate to severe difficulties in both grades 1 and 4. The average numeracy achievement of grades 1 and 4 children with disabilities was significantly lower compared to children from the same grade levels prior to the pandemic. This issue is of particular concern if we acknowledge that these declines in numeracy achievement levels are for children who were enrolled in mainstream schools both in 2018–2019 and 2020–2021. Thus, this raises broader concerns around the quality of teaching and learning in these schools.

Important to emphasise here is an additional point. Our analysis of numeracy results for children in grade 1, noted that there is a learning loss for all children, those reported as having disabilities and those without disabilities. But importantly, we found that the loss for children with moderate to severe disabilities is less than for children without disabilities. For children in grade 4, learning loss was indicated only for children with disabilities only, and not for children without disabilities. Within this group, learning loss was significantly higher for children reported as having mild disabilities than for those reported without disabilities. Thus, even though learning loss was reported across all children, which is not surprising and is in line with other studies in the region (Azevedo et al. Citation2021; Cummiskey, Stern, and DeStefano Citation2021; Parsitau and Jepkemei Citation2020; Sabates, Carter, and Stern Citation2021), what is important to note here is that at a younger age (in grade 1), this loss is not as marked among both children with and without disabilities. But for the case of higher numeracy skills (as those required in grade 4), the learning loss is more evident among children with disabilities. This may indicate the lack of effective teaching and learning where children with disabilities were already behind, and the school closures merely amplified the discrepancies in numeracy scores between those with and without disabilities.

We draw some support for this argument based on the school-level data collected from the 138 schools attended by the children in our sample groups prior to the pandemic, which indicated wide regional and school-based variations in terms of provisions available for children with disabilities. Only a small percentage of these sampled schools provide teaching and learning materials that are specifically designed for students with disabilities. For instance, only about 55% of schools in Addis Ababa teaching and learning materials specifically designed to include students with disabilities in classroom activities was available. This percentage was far smaller (7%) for schools in Benishangul-Gumuz and Oromia regions. Lack of financial resources was mentioned by one-third of the school principals for this lack of provision. Additionally, for more than half of the schools in the regions (except for schools in Addis Ababa), school principals reported that teachers did not get trainings which were relevant to address the needs of children with disabilities. This broad overview provides important insights into the factors which are shaping teaching and learning processes for children with disabilities in Ethiopian classrooms. This raises further concerns about the lack of provision for educational support and engagement for children with disabilities during the pandemic.

Finally, differences in learning loss in grade 4 could also be influenced by the support available at home. For instance, it might be easier for parents to engage with foundational skills, particularly as many of these children are first-generation learners, and hence those in grade 1 received some stimulation on similar tasks at home, during the closures. This might not have been the case for grade 4 children, where parents/carers might be required to support more complex numeracy challenges, which they were unable to do so.

Contribution

Based on the analysis above, we postulate that the three main contributions of this paper are as follows:

This is among the first study that has incorporated the CFM questions in a larger survey in Ethiopia. This was done to establish the prevalence of disability for children who are currently enrolled in mainstream schools. Doing so has enabled us to contribute to international debates on the prevalence of childhood disability and also begin to provide more robust data for analysis within Ethiopia. Asking questions on disability, as noted previously, has been extremely difficult and using the CFM enabled us to seek out a common way of framing disability across different regions in Ethiopia, with distinct local languages. The findings in this study could serve as a basis to conduct further study to understand regional variations.

This is among the first empirical studies that provide an indication of change in reported disability rates before and during COVID-19. As our analysis shows, changes in the incidence of disabilities were substantial, particularly for children with moderate to severe difficulties and in some areas of Ethiopia. While our study is not nationally representative, it provides a good indication of the changing pattern of needs among children as they get older during a global pandemic.

Based on our analysis of numeracy scores before and after school closures, our paper clearly highlights that as schools reopen, there will need to be cognizant of the greater loss of learning experienced by certain groups of children, such as those with disabilities. The Ethiopian government is committed to inclusive education and hence increased efforts need to be directed at ensuring that the quality of education received is equally important, as is access to schooling. Additionally, there is a need to focus on recognising that disability is not a homogeneous category and addressing the multiplicity of exclusionary factors is essential in developing inclusive systems.

As children continue to engage in education in these uncertain times, and as schools continue to address the challenges raised by closures as a result of COVID-19, there is a need to acknowledge that children with disabilities, like all children, need targeted support in engaging with learning inside and outside of schools. Therefore, there is a pressing need to reconfigure the important role of schooling, which centrally values both academic learning and student wellbeing, and the support that children with disabilities receive both in schools and at home.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ricardo Sabates

Ricardo Sabates is a Professor of Education and International Development in the Faculty of Education at the University of Cambridge. Ricardo is also a member of the Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre and the Cambridge Network for Disability and Education Research (CaNDER). His research focuses on educational inequalities in access and learning, primarily in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia. His work has been influential in understanding global inequality patterns in educational access, second chance opportunities in education for marginalised children, cost effectiveness and equity in education, and accountability for learning.

Nidhi Singal

Nidhi Singal is a Professor of Disability and Inclusive Education at the University of Cambridge. She has extensive experience of working with issues of educational equity and social justice in Southern countries, with a particular focus on persons with disabilities.

Tirussew Teferra

Tirussew Teferra is a Professor of Special Needs and Inclusive Education in the College of Education and Behavioural Studies at Addis Ababa University. He is the author and co-author of several articles, book chapters, books, technical reports, monographs and commissioned research in a range of topics including disability, early intervention and education, inclusive and special needs education. He is a member of several national and international professional associations, and a founding member of the Ethiopian Psychologist Association, and the Ethiopian Special Needs Education Professional Association.

Dawit T. Tiruneh

Dawit T. Tiruneh is a Senior Research Associate at the REAL Centre in the Faculty of Education, and a College Research Associate at Homerton College, University of Cambridge. He collaborates with an interdisciplinary and international team of researchers to examine the impacts of large-scale education reforms in improving learning outcomes of primary and secondary school students in low-income countries. Dawit's main research interests include education access and equity, school effectiveness, and instructional design.

Notes

1 In 2006 the Special Needs Education Program Strategy was adopted which promoted a vision of inclusive education (Ministry of Education Citation2006), this has subsequently been updated.

2 Schools in Tigray were not included in the 2020–2021 academic year due to security concerns. We also excluded 2 schools from Benishangul-Gumuz also for security reasons. In total, 138 schools were included in both rounds of data.

References

- Abebe, S. M., M. Abera, A. Nega, Z. Gizaw, M. Bayisa, S. Fasika, B. Molalign, A. Fekadu, and W. Wakene. 2021. “Severe Disability and its Prevalence and Causes in North Western Ethiopia: Evidence from Dabat District of Amhara National Regional State. A Community Based Cross-Sectional Study.” BMC Public Health. https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-18602/v5.

- Azevedo, J. P., A. Hasan, D. Goldemberg, K. Geven, and S. A. Iqbal. 2021. “Simulating the Potential Impacts of COVID-19 School Closures on Schooling and Learning Outcomes. A Set of Global Estimates.” The World Bank Research Observer 36 (1): 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkab003.

- Bayley, S., D. Wole, P. Ramchandani, P. Rose, T. Woldehanna, and L. Yorke. 2021. "Socio-Emotional and Academic Learning Before and After COVID-19 School Closures: Evidence from Ethiopia.” RISE Working Paper Series, 21/082. https://doi.org/10.35489/BSG-RISE-WP_2021/082.

- Beyene, G., and Y. Tizazu. 2010. “Attitudes of Teachers Towards Inclusive Education in Ethiopia.” Ethiopian Journal of Education and Science 6 (1): 89–96. https://doi.org/10.4314/ejesc.v6i1.65383.

- Buchner, T., and S. A. Thompson. 2021. “Issue Information.” Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities 18 (1): 1–3. https://doi -org.ezp.lib.cam.ac.uk/10 .1111jppi.12378.

- Cappa, C., D. Mont, M. Loeb, C. Misunas, J. Madans, T. Comic, and F. de Castro. 2018. “The Development and Testing of a Module on Child Functioning for Identifying Children with Disabilities on Surveys. III: Field Testing.” Disability and Health Journal 11 (4): 510–518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2018.06.004.

- Chala, M. B., S. Mekonnen, G. Andargie, Y. Kebede, M. Yitayal, K. Alemu, T. Awoke, M. Wubeshet, T. Azmeraw, M. Birku, et al. 2017. “Prevalence of Disability and Associated Factors in Dabat Health and Demographic Surveillance System Site Northwest Ethiopia.” BMC Public Health 17 (1): 762. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4763-0.

- Cummiskey, C., J. M. B. Stern, and J. DeStefano. 2021. “Calculating the Educational Impact of COVID-19 (part III): Where Will Students Be When Schools Reopen?.” UKFIET Blog. October 20, 2022. https://www.ukfiet.org/2021/calculating-the-educational-impact-of-covid-19-part-iii-where-will-students-be-when-schools-reopen/.

- Emirie, G., A. Iyasu, K. Gezahegne, N. Jones, E. Presler-Marshall, K. Tilahun, F. Workneh, and W. Yadete. 2020. “Experiences of Vulnerable Urban Youth Under Covid-19: The Case of Youth with Disabilities.” https://www.gage.odi.org/publication/experiences-of-vulnerable-urban-youth-under-covid-19-the-case-of-youth-with-disabilities/.

- Ethiopian Central Statistical Agency. 2012. Ethiopian Population and Housing Census 2007. Administrative Report. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Ethiopian Central Statistical Authority. April.

- Ginja, T. G., and X. Chen. 2023. “Conceptualising Inclusive Education: The Role of Teacher Training and Teacher's Attitudes Towards Inclusion of Children with Disabilities in Ethiopia.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 27 (9): 1042–1055. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2021.1879958.

- Greene, W. H. 1997. Econometric Analysis. New York: Prentice-Hall Inc.

- Groce, N. E., and D. Mont. 2017. “Counting Disability: Emerging Consensus on the Washington Group Questionnaire.” The Lancet Global Health 5 (7): e649–e650. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30207-3.

- Iyer, P., C. Rolleston, P. Rose, and T. Wodehanna. 2020. “A Rising Tide of Access: What Consequences for Equitable Learning in Ethiopia?” Oxford Review of Education 46 (5): 601–618. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2020.1741343.

- James, Z. 2014. “Young Lives School Survey. The Design of Achievement Tests in the Ethiopia School Survey Round 2 (2012-13). Young Lives.” An International Study of Childhood Poverty. Accessed 20 January, 2023. https://www.younglives.org.uk/sites/default/files/migrated/Ethiopia-School-Survey_R2-Design-of-achievement-tests.pdf.

- Madans, J., D. Mont, and M. Loeb. 2015. “Comments on Sabariego et al. Measuring Disability: Comparing the Impact of Two Data Collection Approaches on Disability Rates.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 12: 10329–10351. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120910329.

- Mbazzi, F. M., R. Nalugya, E. Kawesa, C. Nimusiima, R. King, G. van Hove, and J. Seeley. 2021. “The Impact of COVID-19 Measures on Children with Disabilities and their Families in Uganda.” Disability & Society 37 (7): 1173–1196. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2020.1867075.

- Mcclain-Nhlapo, C. V., R. Kulbir Singh, A. H. Martin, H. K. Alasuutari, N. Baboo, S. J. Cameron, et al. 2020. Pivoting to Inclusion: Leveraging Lessons from the COVID-19 Crisis for Learners with Disabilities (English). Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/777641595915675088/Pivoting-to-Inclusion-Leveraging-Lessons-from-the-COVID-19-Crisis-for-Learners-with-Disabilities.

- Ministry of Education. 2006. Strategy of Special Needs Education. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Ministry of Education.

- Ministry of Education. 2012. Special Needs/ Inclusive Education Strategy. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Ministry of Education.

- Ministry of Education. 2016. A Master Plan for Special Needs /Inclusive Education in Ethiopia 2016-2025. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Ministry of Education.

- Ministry of Education. 2018. Education Statistics Annual Abstract. 2018-2019. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Ministry of Education.

- Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs. 2012. Social Protection Policy of Ethiopia. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs.

- Mirta, S., A. Posarac, and B. Vick. 2011. “Disability and Poverty in Developing Countries. A Snapshot from the World Health Survey.” SP Discussion Paper No. 1109. Accessed April 17, 2023. https://ecommons.cornell.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/aea9d45f-bf76-4bd9-a861-eede519ffcdb/content.

- Mizunoya, S., S. Mitra, and I. Yamasaki. 2018. “Disability and School Attendance in 15 Low- and Middle-Income Countries.” World Development 104: 388–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.12.001.

- Parsitau, D. S., and E. Jepkemei. 2020. “How School Closures During COVID-19 Further Marginalize Vulnerable Children in Kenya.” UKFIET Blog. October, 2022. https://www.ukfiet.org/2020/how-school-closures-during-covid-19-further-marginalize-vulnerable-children-in-kenya.

- Sabates, R., E. Carter, and J. M. B. Stern. 2021. “Using Educational Transitions to Estimate Learning Loss Due to COVID-19 School Closures: The Case of Complementary Basic Education in Ghana.” International Journal of Educational Development 82: 102377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2021.102377.

- Sharpe, D., M. Rajabi, C. Chileshe, S. M. Joseph, I. Sesay, J. Williams, and S. Sait. 2021. “Mental Health and Wellbeing Implications of the COVID-19 Quarantine for Disabled and Disadvantaged Children and Young People: Evidence from a Cross-Cultural Study in Zambia and Sierra Leone.” BMC Psychology 9 (1): 79. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-021-00583-w.

- Singal, N., J. Mbukwa-Ngwira, S. Taneja-Johansson, P. Lynch, G. Chatha, and E. Umar. 2021. “Impact of Covid-19 on the Education of Children with Disabilities in Malawi: Reshaping Parental Engagement for the Future.” International Journal of Inclusive Education, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2021.1965804.

- Singal, N., S. Taneja-Johansson, A. Al-Fadala, A. T. Mergia, N. Poudyal, O. Zaki, A. S. Side, D. Khadka, and S. Al-Sabbagh. 2021. “Revisiting Equity: COVID-19 and the Education of Children with Disabilities.” Qatar Foundation. Accessed April 17, 2023. https://www.wise-qatar.org/app/uploads/2021/12/2021wise-rr5-report-web-version.pdf.

- Singal, N., S. Taneja-Johansson, and N. Poudyal. 2021. “Reflections on the gendered impact of covid-19 on education of children with disabilities in Nepal. Blog post for United Nations Girls’ Education Initiative.” Accessed July 18, 2022. https://www.ungei.org/blog-post/reflections-gendered-impact-covid-19-education-children-disabilities-nepal.

- Takeda, T., and K. Lamichhane. 2018. “Determinants of Schooling and Academic Achievements: Comparison between Children with and without Disabilities in India.” International Journal of Educational Development 61: 184–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2018.01.003.

- Teferra, T. 2001. “Preventing Learning Difficulties and Early School Dropout.” In Seeds of Hope: Twelve Years of Early Intervention in Africa, edited by P.-S. Klein. Oslo: Unipub, Forlag. Norway.

- Teferra, T., A. Asgedom, J. Oumer, T. Woldehanna, A. Dalelo, and B. Assefa. 2018. Ethiopian Education Development Roadmap (2018-2030). Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Education Strategic Centre. Accessed April 2, 2023. https://planipolis.iiep.unesco.org/sites/default/files/ressources/ethiopia_education_development_roadmap_2018-2030.pdf.

- UNCRPD. 2010. “Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.” https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html.

- UNESCO, UNICEF, Brookings Institution, and World Bank. 2017. Overview MELQO. Measuring Early Learning Quality and Outcomes. Paris: UNESCO. Accessed from 18 November, 2019, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000248053.

- UNICEF. 2019. Situation and Access to Services of Persons with Disabilities in Addis Ababa. Briefing Note. UNICEF Ethiopia. Accessed April 18, 2023. https://www.unicef.org/ethiopia/media/3016/file/3.Situation%20and%20access%20to%20services%20of%20persons%20with%20disabilities%20in%20Addis%20Ababa%20Briefing%20Note.pdf.

- United Nations. 2020. “Policy Brief: A Disability-Inclusive Response to COVID-19”.

- The Washington Group. 2016. “Report of Ability of Countries to Disaggregate SDG Indicators by Disability”. https://www.washingtongroup-disability.com/fileadmin/uploads/wg/Documents/WG_Implementation_Document__10_-_SDG.pdf.

- The Washington Group/UNICEF CFM. 2020. “Washington Group of Disability Statistics. The Washington Group/UNICEF Child Functioning Module (CFM): Ages 5-17 Years.” Accessed April 17, 2023. https://www.washingtongroup-disability.com/question-sets/wg-unicef-child-functioning-module-cfm/.

- Wijesinghe, T. 2020. “Connect and Adapt to Learn and Live: Deaf Education in Sri Lanka”. https://www.ukfiet.org/2020/connect-and-adapt-to-learn-and-live-deaf-education-in-sri-lanka/.

- Woldehanna, T., M. Araya, and A. Gebremedhin. 2016. “Assessing Children’s Learning Outcomes: A Comparison of two Cohorts from Young Lives Ethiopia.” The Ethiopian Journal of Education XXXVI (1): 149–187.

- World Health Organization and World Bank. 2011. World Report on Disability 2011. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44575.