Abstract

To tackle the high rates of textile waste in the fashion industry through design, it is imperative to understand what makes people keep and wear their clothes for longer. In this paper, we present an analysis of a survey which prompted female participants to write about one of their oldest garments still in use. Following Chapman’s notion that waste is symptomatic of failed relationships, we looked into theory on interpersonal love relationships—in particular, Gottman and Gottman’s Sound Relationship House Theory—to explore if interpersonal relationship traits can be identified in satisfactory long wearer-clothing relationships. Our study shows that principles of happy, lasting interpersonal relationships can be found in wearer-clothing relationships. Moreover, the study shows how friendship principles contribute to wearers’ willingness to overcome conflict in their relationship with clothes, as well as to the creation of meaning. Our findings suggest that designing for emotional attachment should focus on supporting the friendship system, which is foundational for emotional attachment to develop. We illustrate our findings with empirical data and discuss them with relevant literature, while also providing examples on how design can contribute to strengthening the friendship system of wearer-clothing relationships, beyond designed attributes in clothes.

Introduction

Take a look at the oldest items in your wardrobe. What makes them last in your life? Is it the color, the cut, the materials?

The staggering rates of post-consumer textile waste (Niinimäki et al. Citation2020) bear witness to the many clothes which did not do justice to the human and natural resources needed to produce them in the first place. As Chapman (Citation2015) notes, “waste is symptomatic of failed relationships” (24) between users and objects. Hence, research focused on relationships between people and clothes is fundamental to understand their complexity and what kinds of design interventions can favor clothing retention and use, rather than accumulation of unused items or short-term stays in people’s wardrobes.

Our study sets out from a qualitative online survey in which we asked participants to write about one of the garments they had had for longest and still used. Our first findings made us question existing research on garment longevity: more than garment attributes, the longevity of a garment in their wearer’s life is influenced by how the wearer deals with (and overcomes) the hurdles in their relationship with each item (Neto and Ferreira Citation2021b). After all, our lives—ours and our clothes’—are interconnected and influenced by that relationship. Focusing on product attributes to tackle textile waste would be limiting our action to one side of the relationship. Thus, in this paper we explore what influences the successful management of these hurdles: building on the work of Fletcher (Citation2016), Burcikova (Citation2019) and Valle-Noronha (Citation2019), we focus on how wearers relate with their clothes to find out what makes these relationships not fail. While doing so from a design perspective, we expand on the insightful research approach of Beatriz Russo (Citation2010)—who drew from love theory to understand the experience of love for objects—and draw from psychology as well as sociology to analogize these relationships to interpersonal ones. In particular, we will look at wearer-clothing relationships through the Sound Relationship House Theory, in which prominent psychologists John Gottman and Julia Gottman (Citation2017) explain the foundational principles of strong healthy couples.

The article is structured in two parts: the first part discusses existing research on clothing longevity to note how focusing on garment attributes limits designers in their understanding of the issue and, consequently, their course of action; we also present clues from research on interpersonal relationships showing that to look at people’s attitude and behavior toward the significant other helps to understand how uniquely each relationship itself develops through time, which makes it a fertile territory for intervention; the second part of this article presents the analysis of wearer-clothing relationships theoretically framed by the Sound Relationship House Theory (Gottman and Gottman, Citation2017), in dialogue with relevant scholarly discourse on design and clothing longevity.

However, before doing so, it is important to address the obvious contrast in such a comparison: in interpersonal relationships, the principles described in Gottman and Gottman’s theory need to be performed by both partners, as both can feel relationship dissatisfaction and prompt breakup. Yet in wearer-clothing relationships we recognize feelings in the wearer alone; breakups are mostly decided by the individual, who can alternatively engage in active efforts to maintain the relationship with their clothes. This lack of reciprocal feelings or emotional intent between wearers and their clothes does not hinder the parallel we propose to establish with interpersonal relationships, as the wearers’ attitude alone is enough to nurture or undermine the longevity of their relationship with a garment. Notwithstanding the importance of research on product features for extended use, in this article we reframe existing research on garment longevity by broadening its focus, to encompass the relationship between garment and wearer. The perspective on wearer-clothing relationships we present in this paper steps away from the view of clothing merely as part of material culture, to understand it as a non-human loved one; it contributes to understand the complexity and uniqueness of our love for clothes, and how consequently design can spread its scope of action beyond product development and claim an active role in nurturing wearer-clothing relationships.

Exploring longevity: from garment to relationship

In previous research on people’s oldest garment, Niinimäki and Koskinen (Citation2011) identified several design attributes that contribute to clothing retention by supporting the emotional bond between wearers and their garments: these include quality, functionality, design/style, and material. In a previous stage of our study (Neto and Ferreira Citation2021a), limited to garments still in use, we found that participants revealed a similar tendency to identify several design features (including color, material quality and properties, adaptability) as determinants for keeping their garments in use for longer. However, these reasons are personal and should not be interpreted as design guidelines. For example, color was an important feature for several of our participants, and yet, both neutral (e.g., black, white, nude) and vivid colors (e.g., red, purple, neon) were pointed as contributing to longevity—something which was also noted in previous research (Niinimäki and Koskinen, Citation2011). Similarly, material quality (composition) was mentioned to justify the relationship longevity with items made of cotton, leather, wool, linen, acrylic, polyester, nylon, and blends; and differing material properties (such as being light or heavy, warm, or fresh—even “warm, but not too warm”) were mentioned as contributing to garment continuation in wearers’ lives. This shows that a wide range of materials and colors can contribute to long and satisfying use of clothes, and no single solution suits all tastes and needs. Then there is also beauty, which for some people justify their garment’s longevity: Niinimäki and Koskinen (Citation2011) explain that attachment to garments comes not simply from its esthetic beauty but also through beauty experiences that may develop with use. But, again, this is dependent on the user, as some people are more open to beauty and esthetic experiences than others (Harper Citation2018a). On its own, this array of perceived reasons for longevity tells us little on how to tackle fleeting wearer-clothing relationships: a trip to secondhand clothes shops shows that, for many garments, these design features were not enough to prevent disposal by previous owners. Alas, the design of garments is important for the wearer’s enjoyment during and early after purchase, but its importance changes in the long term (Valle-Noronha, Niinimäki, and Kujala Citation2018).

Then what makes our relationships with clothes last? Is it because we wear them so much that they become part of our lives? Or is it because we wear them so little that only moths and mold can defy their endurance?

Our attachment to clothes

In her study on frequently used clothes, Gwilt notes that “clothing users do not necessarily recognize that they have—or feel they have—an emotional attachment with their frequently worn garment” (Citation2021, 9–10). Likewise, in our survey, few participants mentioned emotional values as reasons for their garment’s longevity. Nevertheless, as Gwilt points out, this does not mean that there is no emotional attachment, only that wearers may tend to focus on other tangible (design-wise) and practical reasons to justify garment longevity and use. In their research on strategies to enhance long-term relationships with clothes, Niinimäki and Koskinen (Citation2011) identified emotional values, personal values, effort/achievement, and present/future experiences as essential attributes of the emotional bond between wearers and their clothes, and highlight the importance of creating meaning between wearers and their clothes.

The creation of meaning in our relationship with objects has been studied (notably by Csikszentmihalyi and Rochberg-Halton Citation[1981] 2002), and we know its importance to product attachment, as it may result in long-term use and a postponed replacement (Mugge Citation2007). For this reason, there is a growing interest in design strategies that can elicit the creation of meaning in objects (e.g., Mugge, Schoormans, and Schifferstein Citation2008; Haines-Gadd et al. Citation2018; Casais, Mugge, and Desmet Citation2018). The notion that meaning can be embedded in objects drives current production practices—as designers strive to be “meaning-makers” (Verganti Citation2009; Walker Citation2017)—but also influences consumption practices, as users acquire products in search for meaning, only to remain unsatisfied and skip to the next purchase in an endless search for emotional fulfillment (Chapman Citation2015). This is because “deeper dimensions in product relationships—such as emotional values and the promise of future experiences—are a more problematic task to tackle” (Niinimäki and Koskinen Citation2011, 167). To design something to be meaningful is challenging because meaning, together with memory, emerges from shared experience, from enjoyable use, from the cultivation of the person-product relationship through time (Niinimäki and Armstrong Citation2013, Casais Citation2020). Simply put, the emotionally fulfilling kind of meaning is not automatically gifted at the beginning of a relationship; rather it grows on both partners and flourishes in their shared life.

The ups and downs of life with our clothes

Couple therapists Vagdevi Meunier and Wayne Baker (Citation2012) note many couples believe that, after finding their soulmate, love will solve any challenges that come their way. However, psychologists Hanna Zagefka and Krisztina Bahul (Citation2021) argue that, like other assumptions surrounding relationships, this belief may shape unrealistic expectations and result in relationship dissatisfaction. After all, love is not an end goal; it has to be nurtured through time (Gottman and Gottman Citation2017). This resonates with design research that tells us that the feelings of attachment between user and object can only last if actively sustained (Mugge Citation2007).

In her thesis, Burcikova (Citation2019) identifies everyday aspects (labelled in her model as sensory experiences, enablers, longing and belonging, and layering) that should be addressed for emotionally durable clothing. Nonetheless, the author warns that “relationships with clothes are not static and they evolve and change over time” (Burcikova, Citation2019, 231). In loving relationships, couples inevitably go through ups and downs in their shared life, and not even healthy and flourishing relationships are free from negative events or conflict situations (Meunier and Baker Citation2012). Similarly, wearer-clothing relationships are likely to go through conflict at some point in time (Neto and Ferreira Citation2021b). Valle-Noronha (Citation2019) notes how disruption in these relationships can support active engagements or result in frustrations. In the face of conflict, some people discard their garments, and others do not. We know, for instance, that physical changes in the garments—such as abrasion, rips, stains, or color-fading—and size and fit issues are perceived by several wearers as reasons for clothing disposal (Laitala, Boks, and Klepp Citation2015). However, for other wearers, these are not reasons to let go of their clothes: they may be forgiving of their shirt’s fading colors, the occasional hole in their jumper, the rip on their everyday jeans, and continue to wear them. Others invest time and effort to prolong the life of their garments (Gwilt Citation2021): they learn ways to patch up holes, embroider on top of stubborn stains, and re-dye at home. Changes made to garments to extend their functional life, and acceptance of their appearance—either new or old and worn—are examples of how wearers overcome difficulties and enjoy fashion at a slower pace, beyond the buying experience (Fletcher Citation2016; Clark Citation2019). What distinguishes these outcomes is the will and ability of wearers to deal with conflict (Neto and Ferreira Citation2021b). But what makes wearers more willing and able to deal with conflict with their clothes?

Early in his career as a marital therapist, John Gottman believed, like many of his peers, that building communication and conflict resolution skills was the secret to an enduring, happy marriage; however, throughout his professional and research career, he came to disagree with this assumption: focusing marital intervention in moments of intense emotion (such as conflicts) could be useful to improve those moments, but were not enough to save a marriage (Gottman and Silver Citation2015). Similarly, we can see how, for example, mending skills can be helpful for wearers when facing damage in their clothing, but not enough to overcome the issue if they do not feel their garment is worth mending. Instead, Driver and Gottman (Citation2004) understood that the way couples respond in their daily interactions, however mundane or small, had a cumulative effect on bigger and more emotionally intense interactions (in contexts of romance and conflict) and therefore, marital intervention to improve those small interactions would in turn improve the major interactions and strengthen a marriage in the long run. After decades of research, Gottman and Gottman (Citation2017) developed the Sound Relationship House Theory to explain how certain behaviors are bound to make loving relationships happier, more satisfying, and long-lasting. Can similar behaviors be found in wearer-clothing relationships? A deeper analysis of our qualitative data suggests so.

Methodology

This paper presents an exploratory study focused on people’s long-term active relationships with clothes. To understand why people wear certain clothes for extended periods, we developed a qualitative questionnaire that prompted participants to write about a garment they had owned for a long time and still used. There was no minimum longevity required—only that the participants considered it one of the garments owned for the longest still in use. This was key, as we wanted to exclude the garments people keep for long but no longer wear. Our mostly open-ended questions meant answers could be longer or shorter, according to what each participant was willing to share.

The survey focuses on the perception, thoughts and feelings wearers have toward their chosen garment for the study: whether the descriptions of the items and memories of events are accurate and verifiable is not an issue. Instead, what matters is how wearers perceive their clothes and their relationships with them.

The questionnaire (see Appendix A) was open to all adults and distributed online to potential participants through convenience sampling in Spring 2020. Participation was anonymous, voluntary and did not involve any monetary reward.

Sample

As female participants constituted more than 85% of submissions, the study we present in this paper analyses their responses alone, in a total of 170 valid anonymous responses. Nearly all submissions came from western residents (112 in Europe, 48 in the US). Participating women were 19–80 years old: 9–24 (11%), 25–34 (31%), 35–44 (28%), 45–54 (21%), and ≥55 (9%), the majority of whom had completed a college degree or higher (92%).

Garments chosen by our participants were varied, which we clustered into the following categories: coats, jackets, blazers and parkas (24.7%), sweaters, jumpers and cardigans (18.3%), jeans, pants, leggings and skirts (14.1%), dresses, jumpsuits and rompers (14.1%), Blouses, Shirts and Tunics (10.6%), T-shirts (7.6%), hoodies and sweatshirts (5.9%), and sleepwear and underwear (4.7%). Most of the reported items were bought by the wearer (73%), whereas others were received, mostly from family members, partners, or friends (24%), with a small number of participants not being able to recollect the origin of their garment (3%). The longevity of relationships reported also varied greatly, from participants writing about items they had had for two years, to others referring to garments they had owned for over 30 years.Footnote1

Analysis

Our analysis adopted the grounded theory method as defined by Glaser and Strauss (Citation[1967] 2006) and integrated into design research by Muratovski (Citation2016); in short, the analysis proceeded iteratively through three stages: coding, where we applied open and descriptive labels to the data; categorizing, which entailed the identification of emerging clusters, patterns, or insights; and finally conceptualizing where the emerging patterns were compared with previous findings to establish theoretical connections with interpersonal relationship theory—in particular, the Sound Relationship House Theory (Gottman and Gottman Citation2017)—to understand if features of positive couple relationships can be found in wearer-clothing relationships.

In the next section, we present our findings, illustrate them with qualitative data,Footnote2 and discuss them with relevant literature. Due to the nature of the analysis, the results and discussion are presented together; this is the case because the results of our study are highly qualitative descriptions of personal experiences and feelings that require a connection to prior studies and the theoretical framework to be meaningful.

Unpacking sound wearer-clothing relationships

Sociologist Finnegan Alford-Cooper (Citation1998) conducted a Long-Term Marriage Survey in Long Island in the mid-nineties on couples who had been married for fifty or more years to find what factors contribute to long-lasting marriages. Similar to previous research, Alford-Cooper (Citation1998) found that the happiest long-term married couples in her study “have a ‘give-and-take’ attitude, a willingness to sacrifice for each other. They define their marriage as a creation that has taken hard work, dedication, and commitment” (17). Work and commitment to maintain a relationship can also be recognized in wearer-clothing relationships, as both in our study and previous design research (Niinimäki and Koskinen Citation2011) several wearers recognized good caring practicesFootnote3 as reasons why their item lasted for so long in their lives:

It is well made and I have looked after it. – Grace (50), black tunic with white/gold embroidery (11)

I only wash it by hand, the material is very sensitive. I am always careful with how I wash my clothing to be honest. – Betty (26), black jacket with snake pattern (7)

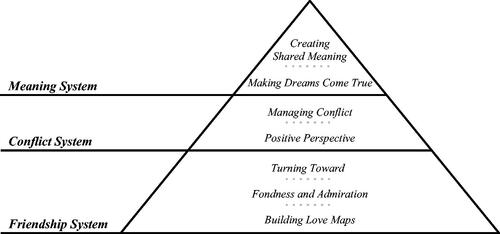

Figure 1 Framework to explore wearer-clothing relationships, adapted from Gottman and Gottman’s (Citation2017) Sound Relationship House Theory.

In this section we will present this theory as a framework to explore wearer-clothing relationships and, in particular, how the participants in our study relate with their clothes.

The friendship system

The foundation of the Sound Relationship House is the Friendship System, which is composed of three principles—Building Love Maps, Sharing Fondness and Admiration, and Turning Toward (instead of Away)—that enhance positivity through nurtured friendship. In what follows, we will analyze these principles and illustrate (with examples from our study) how each applies to wearer-clothing relationships.

Building Love maps

Gottman and Silver (Citation2015) define “love maps” as the part of the mind where a person stores relevant information about their partner’s world, such as facts, tastes and dislikes, feelings, fears, and aspirations. A “love map” (that is, knowledge about the significant other) is quickly built at the beginning of a relationship when a person is most curious about their object of passion. However, the will to map the partners’ world requires constant updates as people and life grow and change. Gottman and Silver (Citation2015) discovered that detailed love maps made partners “far better prepared to cope with stressful events and conflict” (125). When it comes to clothes, Orsola de Castro (Citation2021) notes the opposite scenario: how “the less we know about the clothes we buy, the less we make an emotional connection and the easier it is to get rid of them” (1). In this sense, in wearer-clothing relationships, a “love map” concerns how much the wearer knows about the garment; of course, a garment does not have emotions, fears, or ambitions, but it has particular characteristics that require attention, concerning wear and care. Therefore, in the Friendship System of wearer-clothing relationships, the principle of building and maintaining love maps is noticeable when the wearer knows (and is willing to update their knowledge) about how to use and care for their garment, it is seeking and situating knowledge within that relationship.

It may be reasonably easy to build a love map when the relationship starts. After purchase, wearers may spend some time in front of the mirror to become familiar with how the item interacts with their body and other clothes and accessories. Soon they understand which specific garments from their wardrobe best match the new item. Next, they develop a mental record of the handful of outfits created with that garment, cutting their work short every time they want to wear it. If the person commits to continue enjoying the garment, then, with time, their love map is updated naturally. This ongoing update depends on situations such as: finding a new outfit combination on a day the usual matching items are in the wash; or an entirely different set of outfits when a new job environment requires so; and even learning how to effectively remove a stain in a determined refusal to lose their garment to pasta sauce. Like Fletcher (Citation2016) suggests, to keep clothes in active use “(…) can involve something as simple as approaching a piece with attention and imagination” (18).

Signs of Built Love Maps in our study emerged when wearers revealed they knew what their garment was made of (fabric composition), and shared in-depth knowledge about the item and its needs:

It is stored hanging in my wardrobe. When worn, it is aired frequently as it is outerwear, washed gently if it begins to smell. I use a debobbler if the surface begins to bobble. – Sally (34) wool open cardigan (7)

They’re made of cotton and the seams are well made and sturdy. (…) When not in use, I store them together with similar pants, and occasionally air them outside (my house is humid). – Deborah (22) Blue Sweatpants (8)

The jacket is made of relatively good material (polyester, wool, polietilene and nylon blend) which, despite some pilling, has kept it close to its original shape and looks. I have been very careful with it, debobbling as I can and cleaning the outside with a slightly damp cloth (as it cannot be washed) or dry cleaning when needed. (…) I also hang the jacket outside to be aired. – Isabella (31), Black Winter Jacket (7)

In their study on wearer-clothing attachments, Valle-Noronha, Niinimäki, and Kujala (Citation2018) identified how efforts of engagement can contribute to relationship development, such as “developing or finding new forms of use or combinations (…) where experience over time is able to alter how individuals and garments relate” (237). Therefore, besides knowledge about the garment and how to take care of it, love maps can be identified in participants who justified the longevity of garments with subjective attributes such as versatility or adaptability:

It is practical (good for travelling) and can be both relaxed and more well-dressed. – Bridget (60), Jacket of silk-like cloth, with paillets (17)

It is versatile because it can be worn as a shirt or an open light jacket. – Phoebe (36), Polka-dot Shirt (10)

I can dress it up or down and I can wear it most of the year because it pairs well with jackets, sweaters, or ponchos. (…) It is not form fitting so my weight can fluctuate and I can still wear it. The gray color means it pairs well with many other items in my closet. – Lucy (46), Grey romper (4)

The vest can be worn in the summer on its own or underneath other tops to provide another layer of warmth. It’s seen me through two pregnancies (the start of anyway!) as it’s a bit stretchy, and it’s long so it covers the gap between some tops and trousers. – Jenny (35), Dark grey vest top (8)

It’s a large fit, I wear it in the summer as it is fresh and in the winter with a slim high neck—it’s versatile, also it’s polyester - even if not the best fiber for the environment it doesn’t wear off as some of my older cotton ones. And it’s a floral print, it’s never out of fashion, even if I don’t really care about trends anyway. – Joan (25) Button down shirt with floral print (8)

Designers may try to develop “versatile” items as if versatility was something we could add to clothing, like color. However, we argue that versatility, or adaptability in clothing, is closer to Don Norman’s influential notion of “affordance” (Citation[1988] 2013), which refers to the relationship between object and person. Norman explains that “the presence of an affordance is jointly determined by the qualities of the object and the abilities of the agent that is interacting” (11). We can recognize that the fundamental affordance in clothing is wearability: notice how a shirt can only be correctly worn and buttoned up if the wearer understands the cues from the shape of the armholes and sleeves (to slide the arms in), the shape of the collar (to know which way of dressing makes the collar sit around the neck); and the cues from buttons and buttonholes, which can be matched to close the shirt. The shirt may have features—cues or Norman’s “signifiers”—to help the wearer understand how to use it, but it is, in fact, only wearable when the person understands how to wear it. Take the saree, for example, which can be used in more than 100 different ways (Kaur and Agrawal Citation2019), and yet, without instructions, most people would not be able to wear it in any way at all. In sum, the perceived versatility of a garment decisively depends on the wearer’s ability to use it in different ways, combined with other items in the wardrobe, or in disparate contexts. Therefore, designers may create clothes to be used in varied ways, but that information remains in their minds. For wearers who can do it, it is versatile; and for wearers who cannot, it is not.

Multifunctional garments are an example of a somewhat fragile design strategy for garment longevity: brands may present an item with pictures illustrating the different ways in which it can be used and nonetheless fail to afford versatility, as wearers may stick to one way of using it and overlook other possibilities. Note Kate Fletcher’s (Citation2016) Local Wisdom project, which featured an account exemplifying how “multiple functions take time” (214) to emerge in the wearer’s imagination and ability; moreover, it shows that when a person becomes aware of a different way to use a garment, it does not necessarily mean that they will from then on frequently alternate between different ways of use, and can instead stick to the newly discovered option for a new period of use.

The importance of versatility for the participants in our study is consistent with past research in which this asset is identified as key for garment longevity (e.g., Niinimäki and Armstrong Citation2013; Burcikova Citation2019; Gwilt Citation2021). However, we contend versatility lies in the wearer’s ability to build and update their garments’ love maps; we see it as a strategy that takes shape not as clothing features—which can be, at best, signifiers—but as ways to nurture wearer capabilities (as also signaled by Fletcher Citation2016, and Burcikova Citation2019).

Both designers and brands can contribute to this. Laura Terkildsen, for example, is a wardrobe expert whose work focuses on how to guide women in making the most of what they already have in their wardrobes, providing them with skills to know their clothes and enhance dressing practices (Raebild and Riisberg Citation2021). At the brand level, we can find examples such as Wooland (https://wooland.com), a womenswear label that supports an online community of customers who share their pictures so that other members see how the items fit on people with different shapes and sizes. The initiative highlights how the items can be matched in different outfits and how they can be cared for to last longer, in a lively platform where participants share knowledge and skills that help each other build and maintain their garments’ love maps.

In sum, recognizing the material qualities, knowing how to take good care of the garment, and knowing how to wear it (making it work for different contexts by creating different outfit combinations) will increase the possibility of the wearer-clothing relationship to endure through several types of conflict that may come their way.

Sharing fondness and admiration

Gottman and Silver (Citation2015) identify fondness and admiration as fundamental for a long-lasting marriage. This principle describes the ability of partners to appreciate, cherish, and recognize each other’s worth. As the authors explain, “having a fundamentally positive view of your spouse and your marriage is a powerful buffer when bad times hit. Because they have this reserve of good feeling” (156).

In wearer-clothing relationships, fondness and admiration relate to the ability of the wearer to recognize the qualities of the garment—not just the material aspects, but any qualities that contribute to the relationship. Furthermore, it is important to recognize new qualities over time. Like we observed in love maps, having an overall good feeling about an item and the relationship can be “a powerful buffer” when facing the downs of life.

Fondness and admiration toward a clothing item could be frequently recognized among our survey participants when they were asked to describe the qualities of the garment that have made it last for so long in their lives:

Perfect fit! I am tall, and great fitting pants are hard to find. – Ruth (37) Black dress pants (3)

It is a very beautiful coat that never gets outdated. – Elisabeth (36), suede parka (12)

I am now 51 and still wear my beautiful sweater. – Judith (51), Dark Green Sweater with lace collar (33)

Similarly, Monika Holgar (Citation2019) noticed how garment storytelling instigated “wardrobe noticing” and strengthened wearer’s cognitive relationships with garments: storytelling supported reflection on the actions and experiences that “can enhance the meaning and enjoyment of wearers’ clothing practices and foster the durability of existing and future garments within their wardrobes” (Holgar Citation2019, 199). These examples show how conversations about clothes and wardrobe are an opportunity for participants to “arrive at new levels of awareness about their own lives and experiences” (Pink Citation2009, 87). Further to this point, Holgar (Citation2019) argues that garment storytelling can and should be used “beyond a method for understanding use, to a method for transforming use” (199). Together, the habit of garment appreciation and storytelling can nurture the notion that clothes are worthy objects and fuel the willingness to make them last.

The power of storytelling to influence behavior in a positive way is a potentially rich field for design; in a recent study, Angus Fletcher (Citation2021) combined contemporary findings of modern psychology and neuroscience to argue that narrative (both telling and listening to stories) addresses problems people cannot solve on their own. In short, the author convincingly argues that storytelling has a concrete effect on our minds, explaining why and how people not only create stories but use them to navigate their personal lives. This makes initiatives like “Love Story”, promoted by the Fashion Revolution Movement, all the more meaningful; the initiative prompts sharing fondness and admiration for clothes by challenging people around the world to write a love story about (or love letter to) their favorite garment and share it on social media, while urging wearers to commit to a long-term relationship with their clothes (Fashion Revolution Citation2016). This suggests that designers and brands can, indeed, promote fondness and admiration by helping people tell a story about the contents of their wardrobe.

Turning toward (instead of away)

Gottman and Silver (Citation2015) explain the “bid and turn system” as the daily opportunity for connection in couples. Bids are invitations (often small and subtle, verbal or non-verbal) that each partner makes to connect with the other. In response, the other partner can turn toward (create a positive connection), turn away (ignore the invitation for connection) or turn against (create a negative connection). It is equally vital to bid to connect with the partner and turn toward the partners’ invitations to connect. The positive outcomes of this bid and turn system contribute to the couple’s intimacy. Moreover, couples who engage in these connections are less likely to teeter when hard times hit (Gottman and Silver Citation2015).

In wearer-clothing relationships, turning toward a garment and using it often builds trust in the relationship, even if the item is not worn for memorable occasions. In fact, on special occasions, women often choose to wear items that have already proven to be reliable and are trusted to fit the context of use (Burcikova Citation2019). Moreover, as Fletcher (Citation2016) notes, the practices of use lead to new ways of wearing and thinking about clothes, which builds a greater appreciation for what one has. Turning toward a garment develops intimacy and trust, improves love-maps, and nurtures fondness and admiration. No wonder other wardrobe studies discovered that long-owned, favorite, or attached items, are everyday items (e.g., Guy and Banim Citation2000; Niinimäki and Armstrong Citation2013). As philosopher Soetsu Yanagi (Citation2018) notes, use is a driver for beauty in everyday objects such as clothes, for “the more an object is used the more beautiful it will become, and the more the user uses an object, the more that object will be loved” (41).

While interpersonal relationships demand a dual behavior of bidding and turning toward the partner’s bids, in wearer-clothing relationships, these interactions are less noticeable. Can we assume a clothing item “bids” us for a connection whenever we open the wardrobe to choose what to wear? As Woodward (Citation2015) points out, choosing an item means not choosing others, so when we turn toward a garment, we turn away from others. However, we can look at this bid system from another standpoint: when we choose an item out of our closet only to find it full of creases, is the item turning away from our bid? While the garment does not have intention, it matters that wearers may unconsciously feel it does. The moment a bid is turned away from (in the form of creases), the wearer can either insist on the bid (ironing the creases) or give up and bid a different item, with the feeling that the first choice was not there when needed.

Evidence of Turning Toward in our sample can be identified through signs of frequent wear, signs that the discussed garment is a go-to item, and trusted for specific use contexts:

I wear them so often that they are just part of my life. – Rachel (33), University Sweat Pants (14)

I just think of them as something that is always present with me. Fatter or slimmer, they always fit and they always look good and fashionable. – Hannah (26), Cotton pants (5)

As we present the three foundational principles of the Friendship System between wearer and garment, the interdependence of each principle is evident. Frequently turning toward a garment results from solid love maps, while it is also what allows for love maps to develop.

Similarly, the feelings of fondness and admiration grow from building love maps and the will to turn toward, while also feeding the willingness to maintain those love maps and to continue turning toward.

This also means that nurturing each of these principles will likely affect the others. An example of this is the mobile application “Save your wardrobe” (https://www.saveyourwardrobe.com), which allows users to digitize their wardrobes. The app offers assistance in managing one’s wardrobe by providing recommendations for outfits and promoting an ecosystem of clothing-related services (e.g., repairing, selling, donating, recycling). Essentially, this app promotes the strengthening of the friendship system in wearer-clothing relationships by assisting users in updating love maps of the clothes they own (how to wear and care for them) and by focusing the wearer’s attention on turning toward what they own.

The remaining principles described by Gottman and Gottman (Citation2017) in the Sound Relationship House Theory are the Conflict System and the Meaning System, both of which build upon the Friendship System.

The conflict system

In her research, Burcikova (Citation2019) highlights that clothes do not have a linear lifespan; rather, they have ups and downs in different phases of women’s lives. As discussed previously (Neto and Ferreira Citation2021b), mishaps are bound to happen between wearers and clothes—as it happens in interpersonal relationships—and it is up to the wearer to fix what can be changed and be generous and forgiving toward what cannot change. Negotiating conflict is essential in maintaining a marriage over many years (Alford-Cooper Citation1998) and may play a similar role in the longevity of wearer-clothing relationships (Neto and Ferreira Citation2021b). In the Sound Relationship House Theory, Gottman and Gottman (Citation2017) present the Conflict System, which builds on (and not without) the Friendship System, and explains how partners in satisfying relationships deal with conflict. These principles seem to apply to wearers too.

Positive perspective

Previously, we have seen how the three fundamental principles of friendship can work as a buffer to the negative aspects of a relationship and therefore contribute directly to the first principle of the Conflict System, which is a Positive Perspective when facing conflict. They do so by providing a positive sentiment override (Gottman and Gottman Citation2017) through which the overall good feeling about the partner overrides negative situations, and “the meaning of potential faults is interpreted in the light of surrounding virtues” (Murray and Holmes Citation1994, 651). When facing conflict with a partner, the balance between past negative and positive interactions will largely influence how people deal with conflict. For example, when most past interactions are positive in a relationship with clothes, the positivity felt toward garments can override the negative feelings from conflict situations and motivate us to engage in the necessary efforts to overcome them.

In general I don’t really think about these pants, but they are my go-to work pants, so I think I feel positively about them. I look and feel good when I wear them. [There was a negative moment when] I had gained weight and couldn’t button the pants; I felt irritated and sad, and a little mad. My negative feelings were directed at myself and not the pants. I wore them unbuttoned with a tube top under my shirt to conceal that they were unbuttoned for several months until I could button them again and felt proud when that happened. – Esther (37), Wide-legged Gray Slacks (10)

Managing conflict

Many conflicts that couples undergo throughout their relationship are not solvable (Gottman and Gottman Citation2017). Therefore, directly connected to the Positive Perspective, the principle of Managing Conflict in sound relationships is about overcoming what can be solved and managing what cannot.

We recognize how some brands provide valuable support to wearers facing conflict related to damage in garments, be it through repair advice or mending services, which contribute to a change in wearers’ perception of and expectations toward their garment’s life (Gwilt Citation2021). However, this addresses only part of the issue. For example, in a previous phase of our study (Neto and Ferreira Citation2021b), we identified several origins and types of conflict and different approaches to deal with it, which did not result in disposal. Moreover, we found both an active engagement to overcome conflict and a willingness to maintain the relationship even in the face of unsolvable conflict:

[I wear it] at least 2x per week after washing. Or if it’s still clean I will put it on after I get home from work. I usually wear that shirt for fun outdoor activities with my family: hiking, exercise, going to the movies, over a swimsuit. [I feel] that it’s perfect. (…) The right elbow tore when I got stuck on a tree. I was upset that it tore because I cannot find another shirt of that material that is long sleeve and soft cotton. I decided to keep wearing it anyway. – Sarah (46), long sleeve t-shirt (13)

It is a sound conflict system that helps people continue to wear their clothes even in the face of conflict. Therefore, promoting the principles of the friendship system might make wearers willing and able to overcome conflict with their clothes. Furthermore, wearers are not necessarily aware of their attachment to clothes (Gwilt Citation2021); the lack of awareness of their relationship to clothes may result in thoughtless approaches to conflict with adverse outcomes, such as decreasing wear and even disposal. Therefore, supporting the friendship system raises awareness of these relationships and promotes an intentional approach to the wardrobe.

The meaning system

The Sound Relationship House Theory (Gottman and Gottman Citation2017) presents yet another system that builds on the Friendship Principles, which is related to meaning. As we saw earlier, meaning is often sought as a strategy to design for longevity; however, this is difficult to tackle, as it depends on each person’s personal experience.

The reframing of meaning by the Sound Relationship House Theory helps us understand how it emerges from our relationship with clothes: it relates to the principles of (1) making dreams come true and (2) creating shared meaning.

Making dreams come true

Making Dreams Come True has a direct connection to love maps. As we have seen, building maps is knowing what is important for the other half, including their dreams, hopes and aspirations, which give meaning and purpose to life. Gottman and Silver (Citation2015) explain that dreams can be mundane (e.g., making significant savings) or profound and intangible (e.g., feeling stability) and note that happy spouses know each other’s dreams and consider that helping each other achieve those dreams is integral to the marriage.

Previous wardrobe studies show that women’s chief concerns in their relationship with clothes are how these enable them “to lead the lives they live” (Burcikova Citation2019, 298). Within the principle of making dreams come true, wearers need to feel that each garment helps their daily purpose and supports their dreams and aspirations. Gottman and Silver (Citation2015) identified common intangible dreams, of which we highlight: a sense of freedom; feeling at peace; exploring one’s identity; adventure; healing; empowerment; dealing with growing older; exploring a creative side; exploring one’s physical side, and productivity. These resonate with existing wardrobe studies that connect clothes to constructing women’s past, present, and future identities, thus merging what they were, what they are and what they aspire to be (e.g., Guy and Banim Citation2000; Woodward Citation2007; Burcikova Citation2019). In our study, we can find signs that garments contribute to these intangible dreams by supporting specific feelings in their wearers, who were asked to recall a special moment with their chosen garment:

I wore it for a work event. I received several comments and I felt like a million bucks. – Agnes (42), Royal Blue Dress (2)

Had a fun night out in NYC. I felt young and vibrant. – Kitty (37), Neon Fit n Flare Dress (8)

I had my first kiss with my current husband. Felt confident and empowered. – Ellen (28), Red Polka Dot Dress (12)

[a negative moment was] Putting it on when I was pregnant and already feeling uncomfortable in my body. It made me feel very unattractive and drew attention to my belly so I put it in a cupboard where I store stuff I don’t use until recently, 10 [months] post partum, I raided that cupboard and put it back on. – Alicia (33), Oversize Jumper (6)

Creating shared meaning

In material culture, ‘shared meaning’ refers to the collective meaning attributed to particular objects, which is conditioned by culture (Casais Citation2020). In our analysis, ‘shared meaning’ with clothes is closer to the notion of symbolic meaning—what a product personally represents to the owner, as described by Casais (Citation2020)—but goes beyond it, referring to the meanings that garments and wearers create throughout their relationship. Gottman and Silver (Citation2015) define shared meaning as the micro-culture that develops between two partners as they share their life experiences, and build symbols, stories, and memories around them. This micro-culture develops through changes in life and each partner, and having it lessens the impact of conflict (Gottman and Silver Citation2015). Shared meaning exists in both minds between a couple, but it is naturally different in wearer-clothing relationships. The garment may show signs of that micro-culture—in wear and tear—but this micro-culture flourishes in the wearer’s mind: this phenomenon is referred to in garment longevity literature as the importance of memory for clothing attachment (e.g., Niinimäki and Armstrong Citation2013).

Gottman and Silver (Citation2015) identified four pillars for shared meaning, which we can recognize in people’s relationship with clothes:

Rituals of Connection refer to enjoyable routines or rituals that naturally develop in a relationship. In wearer-clothing relationships, it relates to Love maps, as clothing maintenance practices can be rituals of connection, but also to Turning Toward in the form of habits of wear.

I have worn at many parties and always bring on holiday. – Grace (50), black tunic with white/gold embroidery (11)

Support for each other’s roles is about how partners’ support contributes to shared purpose. In wearer-clothing relationships, it means expectations the wearer has for the garment regarding its abilities to support the wearer’s roles, such as the professional-self at a job interview or the personal-self in a family setting, such as Dorothy’s role as a mother:

[a special moment is] every moment I hug my kids and they like to feel the extra softness of my arms. – Dorothy (59), warm colored sweater (30)

Shared Goals relate to short and long-term aspirations: while people do not share goals with their clothes (as clothes will not actively support them), dressing is a moment when wearers choose allies for their daily adventures, such as a shirt for an important meeting or sweatpants to stay at home recovering from a cold. When these alliances have a positive effect, clothes are “labelled” according to their ability to pursue specific goals, and therefore deemed reliable:

I would wear it when studying in winter and being able to play with the [hem] was surprisingly calming. – Caroline (28), Yellow Hooded Jacket (10)

Shared Values and Symbols relates to the couple’s perspective on life. In wearer-clothing relationships, it takes shape in facts, feelings, and values embedded in clothes. As Woodward (Citation2007) notes, clothes develop their cultural biography as they are worn, while also being important elements of the wearer’s biography. For instance, a suit can become associated with an accomplished career move or a dress with a family trip. As clothes stand for specific events or achievements, those moments become part of the shared life between wearer and garment:

I wore it on a date with my husband who was my boyfriend at the time, we went to the movies and it was a lot of fun. It helped that I felt cute and comfortable. – Martha (26), Grey sweater with metallic stars (8)

Overall, shared meaning is developed with use, which in turn contributes to further appreciation of the item and the desire to continue wearing it.

While shared meaning favors the wearer-clothing relationships reported in our study, we recognize it can also be damaging. Niinimäki and Armstrong (Citation2013) noted how emotional attachment to garments could result in extended ownership but not necessarily in extended use. Think, for example, of a shirt signed by one’s favorite footballer: the wearer now shares with the shirt the unforgettable moment of meeting their idol. That shirt is bound never to be used again. In fact, previous research showed that some garments are kept for long periods despite not being used precisely because they become memory-holders (Bye and McKinney Citation2007; Niinimäki and Koskinen Citation2011).

I rarely wear it because I'm afraid of ruining it. (…) It is a memory of an event my brother and I enjoyed together. We are not very close, but this was something we had fun doing. – Alice (53), Joan Jett t-shirt (10)

Therefore, shared meaning connects to the way memories contribute to product attachment, but memories—even good ones—can also contribute to the end of active wearer-clothing relationships if they keep the wearer from further engaging with (i.e., wearing) the garment, in which case, the wearer becomes available to wear other garments. This phenomenon reinforces the notion that having durable clothes in the wardrobe does not necessarily contribute to sustainable consumption if these do not prevent wearers from acquiring more clothes (Maldini et al., Citation2019). So, more than keeping garments for longer, it is important to wear them. To this end, and from a design perspective, enhancing the friendship system of wearer-clothing relationships may be more important for active longevity than aiming directly to create meaning.

Conclusions

Alford-Cooper’s research (1998) suggests that the guidelines for successful lifelong marriages also apply to other relationships such as those with friends, family members, coworkers or business partners. We propose they might also apply to relationships between users and objects, particularly between wearers and their clothes. In this study, we build on the notion that the way wearer-clothing relationships work is very similar to how interpersonal relationships do. We aimed to understand if this lens could bring us new insights into what makes wearer-clothing relationships last.

Notice the following example from our survey—in Jane’s lengthy account, we recognize a sound wearer-clothing relationship through signs of a positive Friendship System (FS), Conflict System (CS), and Meaning System (MS):

It’s versatile for weather (rain or shine). It’s easy to care for (machine wash). Easy to pack. Doesn’t wrinkle easily. It’s comfortable. It’s lined, so it slips on and off easily no matter what I’m wearing (sweater, T-shirt, etc). It layers well. It’s figure-flattering but also adjusts easily with body changes because of the belted waist (I’ve worn it at 108lbs after illness and at 170lbs when I was pregnant). It has held its color well, though I don’t know how or why (FS). I feel good in it. When I put it on I feel “put together” because it’s stylish and always gets compliments (MS). Oh, it has great pockets!! They are deep and also lined:) Funny, I would have sworn it was Banana Republic, but I checked the tag and it’s actually H&M (FS).

I live in Texas, so I don’t wear jackets in the warmer months, but I return to it every year about September-April (FS) and I always take it on trips. I went to an important conference in DC that was a big deal for me professionally. I bought it for that trip and I felt really good in it. I felt like I looked professional, stylish, and polished. I felt cheerful; the bright red color makes me feel happy. I felt bold and confident because of the color too. I felt unique and identifiable. I feel comfortable and confident when I put it on (MS). It got a minor stain. I worked hard to get it out, but it’s still slightly there if you look. I was annoyed it had happened because I love the jacket, but I still wear it anyway (CS). – Jane (42), red trench coat (7)

This example, together with the findings presented throughout this paper, indicates that behaviors identified in interpersonal love theory as contributing to relationship longevity can also be recognized in long-term wearer-clothing relationships. Furthermore, these behaviors seem to influence the willingness of wearers to overcome frictions arising in the relationship with their clothes. For theory on clothing use, our findings strengthen the argument that more than attributes in clothing, the relationship develops when the user supports its longevity (Fletcher Citation2016). If the construction of meaningful relationships with clothes is critical to fostering clothing longevity, how can this be achieved?

This study offers a clearer picture of how meaning is developed and sustained in wearer-clothing relationships, contributing to theory on product attachment. While the results are consistent with previous research, our study is framed by interpersonal relationship theory, which helps understand why common design strategies that promote user attachment cannot foster longevity. Furthermore, we noticed that other strategies might contribute more deeply to support wearer-clothing relationships.

In particular, our paper sheds new light on emotional durability and how it can be addressed to promote longer product lifespans. Kristine Harper explains that “emotional durability concerns sentimental value and the emotional bond between an object and its owner, which might lead to sustainable behavior, such as mending, frequent usage and appreciation.” (Harper Citation2018b, n.p.). Considering wearer-clothing relationships from the perspective of the Sound Relationship House Theory, we notice that it is frequent usage (turning toward) and appreciation (fondness and admiration)—essential principles of the friendship system—that can unlock the willingness to deal with conflict (e.g., through mending) and contribute to the emotional durability of solid relationships.

From this perspective, design strategies for emotional attachment may be more effective when directed at enhancing the friendship system, which is foundational for emotional attachment and plays a significant role in conflict management. Conversely, attempts at designing for the conflict system (e.g., trying to eliminate conflict) or the meaning system (e.g., designing for emotional attachment) are less effective when wearer-clothing relationships still lack the foundational friendship system. But how can design focus on the friendship system? In this paper, we provided some examples which go beyond clothing design attributes and instead explore how to stimulate the principles of friendship, keeping in mind that the complexities of wearer-clothing relationships mean there is no “one size fits all” solution.

It is worthy to note that, while we focused our analysis on the female respondents from our survey, the Sound Relationship House Theory applies to both men and women: this raises the hypothesis for future research that the traits found in relationships between the female wearers from this study and their clothing might be similarly recognized in those pertaining to male wearers. Further research is needed to understand whether there is a gender dimension to the love relations between wearers and their clothes. Finally, we recognize the method we used to explore long-term wearer-clothing relationships poses a particular limitation: a qualitative survey serves as a cross-sectional study, thus revealing a part of a whole relationship. The data was sufficient to identify the parallel with sound interpersonal relationships and support the reasons wearers keep their clothes for longer; nevertheless, future research such as longitudinal studies on wearer-clothing relationships is necessary to expand this theory.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Pedro Ramos for proofreading and language editing the manuscript, and the anonymous reviewers for their invaluable and constructive feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ana Neto

Ana Neto is a Doctoral Candidate in Design at CIAUD, Research Centre for Architecture, Urbanism and Design, Lisbon School of Architecture, Universidade de Lisboa, Portugal. Her professional background is in product development for the clothing industry, experienced across different environments and product categories. In 2021, Ana was awarded a PhD studentship by the Portuguese national funding agency for science, research, and technology (FCT). Her research is focused on how people engage with their clothes beyond the point of purchase and before disposal in order to understand how wearer-clothing relationships can last for longer. Ana gave vocational training on product development and is currently involved in projects on research and education in design. [email protected]

João Ferreira

João Batalheiro Ferreira is Assistant Professor and coordinator of the Undergraduate Degree in Design at Universidade Europeia, IADE–Faculdade de Design, Tecnologia e Comunicação,UNIDCOM/IADE, Portugal. He holds a PhD in Design from the Delft University of Technology, Netherlands (2018) his PhD research focused on the study of teacher-student communication during design studio classes. Between November 2017 and September 2020 he joined the group REDES– Research & Education in Design as a research fellow (group belonging to CIAUD–Center for Research in Architecture, Urbanism, and Design). João holds a Master’s degree in Communication Design by the Faculty of Architecture of the University of Lisbon (2010) and graduated in Product Design by the same institution; he taught design courses at the Delft University of Technology, the Faculty of Architecture of the University of Minho, and the Faculty of Architecture of the University of Lisbon. He worked as a professional communication designer (2007–2009) and continues to work occasionally as a freelancer in design projects. [email protected]

Notes

1 Additional information about our data with no particular relevance for this article can be found elsewhere (Neto and Ferreira Citation2021b).

2 We identify each testimony with the participants’ age, garment, and relationship longevity. Names used were randomly assigned to each submission.

3 This is not to say that care is love. As Puig de la Bellacasa (Citation2017) notes, not all care stems from love, and not all love involves care—however, “nothing holds together without relations of care” (67). Care, as a labour of love—the hard work, dedication and commitment involved in interpersonal love relationships—seems to be similarly at the heart of longevity between wearers and their clothes. So, though we could expect wearers’ demonstrations of love for garments to be consistently enthusiastic, passionate discourses, we noted elsewhere how passion is more intense in the beginning of the relationship, only to give space to intimacy and commitment to develop and support the relationship in the long run (Neto and Ferreira Citation2020, Citation2021b). Alas, it is by eliciting passion that fashion commerce aces at kick-starting wearer-clothing relationships, heedless of all the things long relationships are made of. After all, it is the ability and willingness of wearers to develop intimacy with and commitment to their garments that contribute to an enduring relationship. It is no wonder, then, that while participants in our survey may write about one of their oldest garments in use with affection, their accounts are more evocative of the aforementioned labours of love than of passionate honeymoon periods.

4 As Woodward (Citation2007) notes, the life of the wardrobe—the inflows and outflows of clothes, and the current stock of clothes at any given moment—allows women to construct their biography through clothing. These include both clothes in active use and those out of use. As we understand the importance of clothes out of use for the reflection on the wearer’s past, present and future identities, we acknowledge that clothing “use” applies to the actual wearing of items, but also that no longer worn but intentionally kept clothing falls under another form of use. Guy and Banim (Citation2000) noted precisely how clothes have a life beyond wear, as women in their study kept a relationship with clothes which had ceased to be worn. Even so, our study focuses on wearer-clothing relationships (that is, the relationships between people and their clothes in active wear), and how these impact clothing consumption.

References

- Ackermann, Laura, Ruth Mugge, and Jan Schoormans. 2018. “Consumers’ Perspective on Product Care: An Exploratory Study of Motivators, Ability Factors, and Triggers.” Journal of Cleaner Production 183: 380–391. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.099.

- Alford-Cooper, Finnegan. 1998. For Keeps: Marriages That Last a Lifetime. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

- Burcikova, Mila. 2019. “Mundane Fashion: Women, Clothes and Emotional Durability.” PhD diss., University of Huddersfield.

- Bye, Elizabeth, and Ellen McKinney. 2007. “Sizing up the Wardrobe – Why We Keep Clothes That Do Not Fit.” Fashion Theory 11 (4): 483–498. doi:10.2752/175174107X250262.

- Casais, Mafalda. 2020. “Design with Symbolic Meaning: Introducing Well-Being Related Symbolic Meaning in Design.” PhD diss., Delft University of Technology.

- Casais, Mafalda, Ruth Mugge, and Pieter Desmet. 2018. “Objects with Symbolic Meaning: 16 Directions to Inspire Design for Well-Being.” Journal of Design Research 16 (3/4): 247. doi:10.1504/JDR.2018.099538.

- Castro, Orsola de. 2021. Loved Clothes Last: The Joy of Repairing, Rewearing and Caring for Your Clothes. S.L.: Penguin Life.

- Chapman, Jonathan. 2015. Emotionally Durable Design: Objects, Experiences and Empathy. London; New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group.

- Clark, Hazel. 2019. “Slow + Fashion – Women’s Wisdom.” Fashion Practice 11 (3): 309–327. doi:10.1080/17569370.2019.1659538.

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly, and Eugene Rochberg-Halton. [1981] 2002. The Meaning of Things: Domestic Symbols and the Self. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Driver, Janice L., and John M. Gottman. 2004. “Daily Marital Interactions and Positive Affect during Marital Conflict among Newlywed Couples.” Family Process 43 (3): 301–314. doi:10.1111/j.1545-5300.2004.00024.x.

- Fashion Revolution. 2016. A Fashion Revolution Challenge: Love Story. Accessed from https://fashionrevolution.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/FashRev_LoveStory_18.pdf

- Fletcher, Angus. 2021. The 25 Most Powerful Inventions in the History of Literature. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Fletcher, Kate. 2016. Craft of Use: Post-Growth Fashion. Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge.

- Glaser, Barney G., and Anselm Strauss. [1967] 2006. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. London: Transaction Publishers.

- Gottman, John, and Julie Gottman. 2017. “The Natural Principles of Love.” Journal of Family Theory & Review 9 (1): 7–26. doi:10.1111/jftr.12182.

- Gottman, John Mordechai, and Nan Silver. 2015. The Seven Principles for Making Marriage Work: A Practical Guide from the Country’s Foremost Relationship Expert. New York: Harmony Books.

- Guy, Alison, and Maura Banim. 2000. “Personal Collections: Women’s Clothing Use and Identity.” Journal of Gender Studies 9 (3): 313–327. doi:10.1080/713678000.

- Gwilt, Alison. 2021. “Caring for Clothes: How and Why People Maintain Garments in Regular Use.” Continuum 35 (6): 870–882. doi:10.1080/10304312.2021.1993572.

- Haines-Gadd, Merryn, Jonathan Chapman, Peter Lloyd, Jon Mason, and Dzmitry Aliakseyeu. 2018. “Emotional Durability Design Nine – A Tool for Product Longevity.” Sustainability 10 (6): 1948. doi:10.3390/su10061948.

- Harper, K. 2018a. “Aesthetic Nourishment.” The Immaterialist (blog). November 1, 2018. https://immaterialist.blog/2018/11/01/aesthetic-nourishment/.

- Harper, K. 2018b. “Aesthetic Sustainability.” The Immaterialist (blog). June 27, 2018. https://immaterialist.blog/2018/06/27/aesthetic-sustainability/.

- Holgar, Monika. 2019. “The Wardrobe Impact of Worn Stories: Exploring Garment Storytelling for Sustainability.” PhD diss., Queensland University of Technology.

- Kaur, Koshalpreet, and Anjali Agrawal. 2019. “Indian Saree: A Paradigm of Global Fashion Influence.” International Journal of Home Science 5 (2): 299–306. https://www.homesciencejournal.com/archives/2019/vol5issue2/PartE/5-2-46-788.pdf.

- Laitala, Kirsi, Casper Boks, and Ingun Grimstad Klepp. 2015. “Making clothing Last: A Design Approach for Reducing the Environmental Impacts.” International Journal of Design 9 (2): 93–107. http://www.ijdesign.org/index.php/IJDesign/article/view/1613/696.

- Maldini, Irene, Pieter J. Stappers, Javier C. Gimeno-Martinez, and Hein A. M. Daanen. 2019. “Assessing the Impact of Design Strategies on Clothing Lifetimes, Usage and Volumes: The Case of Product Personalisation.” Journal of Cleaner Production 210: 1414–1424. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.11.056.

- Meunier, Vagdevi, and Wayne Baker. 2012. “Positive Couple Relationships: The Evidence for Long-Lasting Relationship Satisfaction and Happiness.” In Positive Relationships, edited by S. Roffey, 73–89. Dordrecht: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-2147-0_5.

- Mugge, Ruth. 2007. “Product Attachment.” PhD diss., Delft University of Technology.

- Mugge, Ruth, J. P. L. Schoormans, and H. N. J. Schifferstein. 2008. “Product Attachment: Design Strategies to Simulate the Emotional Bonding to Products.” In Product Experience, edited by H. N. J. Schifferstein and P. Hekkert, 425–440. New York: Elsevier.

- Muratovski, Gjoko. 2016. Research for Designers: A Guide to Methods and Practice. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Murray, Sandra L., and John G. Holmes. 1994. “Storytelling in Close Relationships: The Construction of Confidence.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 20 (6): 650–663. doi:10.1177/0146167294206004.

- Neto, A., and J. Ferreira. 2020. “From Wearing off to Wearing on: The Meanders of Wearer–Clothing Relationships.” Sustainability 12 (18): 7264. doi:10.3390/su12187264.

- Neto, Ana, and João Ferreira. 2021a. “Through Thick and Thin: Committing to a Long-Lasting Wearer-Clothing Relationship.” Paper presented at the 4th PLATE 2021 Virtual Conference, Limerick, Ireland, May 26–28. doi:10.31880/10344/10253.

- Neto, Ana, and João Ferreira. 2021b. “I Still Love Them and Wear Them” – Conflict Occurrence and Management in Wearer-Clothing Relationships.” Sustainability 13 (23): 13054. doi:10.3390/su132313054.

- Niinimäki, Kirsi, and Cosette Armstrong. 2013. “From Pleasure in Use to Preservation of Meaningful Memories: A Closer Look at the Sustainability of Clothing via Longevity and Attachment.” International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education 6 (3): 190–199. doi:10.1080/17543266.2013.825737.

- Niinimäki, Kirsi, Greg Peters, Helena Dahlbo, Patsy Perry, Timo Rissanen, and Alison Gwilt. 2020. “The Environmental Price of Fast Fashion.” Nature Reviews Earth & Environment 1 (4): 189–200. doi:10.1038/s43017-020-0039-9.

- Niinimäki, Kirsi, and Ilpo Koskinen. 2011. “I Love This Dress, It Makes Me Feel Beautiful! Empathic Knowledge in Sustainable Design.” The Design Journal 14 (2): 165–186. doi:10.2752/175630611X12984592779962.

- Norman, Donald A. [1988] 2013. The Design of Everyday Things. Massachusetts: Mit Press.

- Petersson McIntyre, Magdalena. 2021. “Shame, Blame, and Passion: Affects of (Un)Sustainable Wardrobes.” Fashion Theory 25 (6): 735–755. doi:10.1080/1362704X.2019.1676506.

- Pink, Sarah. 2009. Doing Sensory Ethnology. London: Sage Publications.

- Puig De La Bellacasa, María. 2017. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More than Human Worlds. Minneapolis (Minn.): University Of Minnesota Press.

- Raebild, Ulla, and Vibeke Riisberg. 2021. “How to Design out Obsolescence in Fashion? – Exploring Wardrobe Methods as a Strategy in Design Education.” Paper presented at the 4th PLATE 2021 Virtual Conference, Limerick, Ireland, May 26–28. doi:10.31880/10344/10260.

- Russo, Beatriz. 2010. “Shoes, Cars, and Other Love Stories: Investigating the Experience of Love for Products.” PhD diss., Delft University of Technology.

- Valle-Noronha, Julia. 2019. “Becoming with Clothes: Activating Wearer-Worn Engagements through Design.” PhD diss., Aalto University.

- Valle-Noronha, Julia, Kirsi Niinimäki, and Sari Kujala. 2018. “Notes on Wearer–Worn Attachments: Learning to Wear.” Clothing Cultures 5 (2): 225–246. doi:10.1386/cc.5.2.225_1.

- Verganti, Roberto. 2009. Design-Driven Innovation: Changing the Rules of Competition by Radically Innovating What Things Mean. Boston, Ma: Harvard Business Press.

- Walker, Stuart. 2017. Design for Life: Creating Meaning in a Distracted World. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Woodward, Sophie. 2007. Why Women Wear What They Wear. Oxford: Berg.

- Woodward, Sophie. 2015. “Accidentally Sustainable? Ethnographic Approaches to Clothing Practices.” In Routledge Handbook of Sustainability and Fashion, edited by Kate Fletcher and Mathilda Tham, 131–138. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Yanagi, Soetsu. 2018. The Beauty of Everyday Things. London: Penguin Books.

- Zagefka, Hanna, and Krisztina Bahul. 2021. “Beliefs That Contribute to Dissatisfaction in Romantic Relationships.” The Family Journal 29 (2): 153–160. 106648072095663 doi:10.1177/1066480720956638.

Websites

- https://wolk-antwerp.com/ accessed January 27, 2022.

- https://wooland.com accessed January 27, 2022.

- https://bemorewithless.com/project-333/ accessed January 27, 2022.

- https://fashiondetoxchallenge.com/ accessed January 27, 2022.

- https://www.saveyourwardrobe.com accessed January 27, 2022.

Appendix A.

Survey questions

Year of Birth:

Gender: □ M □ F □ Other

Nationality:

Country of Residence:

Studies:

□ Below Secondary Education □ Secondary Education (High School)

□ Higher Education (University) □ Postgraduate Education

Can you think about one of the garments you have owned the longest and still wear?

Please describe it.

Is it a favorite item? □ Yes □ No

Since when have you owned it? (can you tell the year and the season or the month?)

Can you describe the qualities (physical or not), that has made it last for so long in your life?

How did it enter your life?

□ Bought it

Where? (for example: brand online/physical shop; a market; secondhand)

What were the most important qualities you were looking for in that type of garment? Did that specific garment have those qualities?

□ Received it

From whom? Did you choose it? Was it a surprise? What did you think of it at first?

□ Can’t remember

Did you always use it with the same frequency?

□ Yes

How frequently (approximate times per month)?

□ No

What happened? Can you recall what made you wear it more and less frequently through time?

How do you usually take care of it (routine care; when it gets damaged; when out of season; or other)?

Can you recall a special moment you had with it? What happened? How did you feel?

What did you feel about the garment, if anything?

Can you recall a negative moment you had with it? What happened? How did you feel?

What did you feel about the garment, if anything?

Has the garment ever suffered any damage? (e.g., stubborn stain; ripped seam, hole, broken zipper or lost button; color change…)

□ No □ Can’t remember

□ Yes

What was it? How did you feel about it when it happened?

What did you do?

□ I repaired it

□ I asked or paid someone to repair it

□ I decided to keep wearing it anyway

Right now, what are the most important qualities you are looking for in that type of garment? Does that specific garment have those qualities?

How would you rate your relationship with that garment now?

(5-point scale, in which 1 = “very unhappy” and 5 = “very happy”)