ABSTRACT

The present article analyses the strategy used by the sultans of Sulu over two centuries (19th-21st) to affirm their status and authority, from their costumes to the symbols used. By doing so, it highlights how tradition makes use of old materials, symbols and rites from the southern Philippines, while it incorporates others which belong to the European heraldic language to extend the symbolic vocabulary of authority and power. The article uses written and visual sources to demonstrate how the royal house adapts to the changing local and international political situations. The comparison cases from the 19th and the 21st centuries shed light on the evolving diplomatic usage and contribute to a better understanding of the political culture of the Sultanate of Sulu.

ABSTRAK

Makalah ini menganalisis strategi yang digunakan oleh para sultan Sulu selama dua abad (abad ke-19 dan ke-21) untuk menegaskan status dan kekuasaan mereka, mulai dari pakaian hingga simbol-simbol yang digunakan. Dengan demikian, makalah ini menyoroti bagaimana tradisi menggunakan bahan-bahan, simbol-simbol, dan ritus-ritus lama dari Filipina Selatan, selain juga menggabungkan beberapa hal yang berasal dari bahasa heraldik Eropa untuk memperluas kosakata simbolis otoritas dan kekuasaan. Makalah ini menggunakan sumber-sumber tertulis dan visual untuk menunjukkan bagaimana istana kerajaan beradaptasi dengan situasi politik lokal dan internasional yang terus berubah. Perbandingan kasus dari abad ke-19 dan ke-21 menjelaskan penggunaan diplomatik yang terus berkembang dan berkontribusi pada pemahaman yang lebih baik tentang budaya politik Kesultanan Sulu.

Introduction

On 16 September 2012, a small ceremony took place in Maimbung, Sulu in southern Philippines. At a site named Darul Jambangan, where the astana (palace) used to stand, Muedzul-Lail Tan Kiram was proclaimed the 35th sultan of the Sulu sultanate, asserting authority over the archipelago of Sulu and North Borneo. This event of modest scale, celebrated only in the presence of the extended family and a few local officials, received almost no press attention. Moreover, as the Republic of the Philippines did not recognise the succession as it considers the sultanate abolished – it had no political repercussion.

This article proposes to start from this apparently insignificant event, to analyse the visual language used by the sultans of Sulu over the past two centuries, in order to assert their status and related authority. Considering the entire set of actions carried by heirs and rulers to present themselves in public since the 19th century, this article intends to highlight the role of certain symbols and visual elements in the performance of political authority, as well the meanings that lie behind different ‘traditions’.

The article starts with a conceptual overview defining authority and placing it within the cultural environment of the Sulu sultanate. It continues with a presentation of 19th-century Sulu when a sultan had to show his authority in a context of political competition, including when he was losing power after the Philippines was ceded to the United States in the Treaty of Paris 1898 for US$20 million following the Spanish-American War. Finally, it presents the visual and symbolic language used by Muedzul-Lail Tan Kiram to affirm his position and support his claim to the throne in the 21st century, and propose an explanation for the use of different repertoires.

Defining authority in 19th-century Sulu

Authority is often discussed by political theorists in relation to the state. However, it is also, and primarily, part of any social relation. Authority defines the implicit substratum of relationships and partly explains hierarchy. In simple theoretical terms, it is the faculty of gaining another person’s assent without the use of coercive means (de Jouvenel Citation1957: 37). However, while the absence of initial coercion defines authority, it does not exclude the use of force, which is defined as being legitimate when coming from a source of authority (Kojève Citation2004: 137).Footnote1

In the context of the Sulu sultanate, and the Philippines Muslim south in general, the issue of violence has periodically been brought up to explain the unstable political context. According to European powers which occupied the archipelago, it was the incapacity of the sultan to impose order – in other words to control local rulers (datu, panglima) – that rendered agreements impossible to implement. Force was indeed the privilege of many and state affairs were often decided collectively, but not without hierarchy. Treaties signed by the sultan along with other rulers demonstrate the existence of periodic consensus. Decision making, the implementation of rules and law, were neither centralised nor followed a strict hierarchical order. The socio-political system was multipolar and when consensus could not be reached, each party chose the way that accommodated them best.

In this system, the sultan’s authority was legitimated by ‘an established belief in the sanctity of immemorial traditions’ (Weber Citation1980: 124).Footnote2 No matter how strong and powerful a datu or a panglima was, he could use force to gain power though could seldom compete with traditional authority. In his foundational work, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft, Max Weber explains the subtle distinction between this concept, also known as legitimate domination (Herrschaft), and power (Macht). In Weberian terms, authority is:

… the chance to find obedience for specific (or for all) commands in a specifiable group of people. Therefore, not every kind of chance to exercise ‘power’ and ‘influence’ on other people. Domination (‘authority’) in this sense can, in individual cases, be based on the most varied motives of obedience: from dull habit to purely rational considerations. A certain minimum of wanting to obey, that is: interest (external or internal) in obeying is part of every real relationship of domination.

Starting at least in the 18th century, to be recognised as sultan in Sulu, a man needed three conditions: to be a relative of a previous ruler, to possess wealth, and to obtain the official recognition of a council, the ruma bichara (Majul Citation1965: 34).Footnote3 It was not uncommon to have several pretenders to the throne who were all considered as legitimate. Ultimately, other elements played a role in deciding the rightful ruler, and while there was no ready-made formula to win in such a competition, one deciding element was the number of people who believed in the inherited right of the ruler to guide them. The two lines of descent played therefore a major role in gathering followers and strengthening the claim.

An example that illustrates this case is the succession feud following the death of Sultan Shakirullah (r.1821–1823), where four contenders claimed their rights as head of the sultanate: Sultan Shakirullah’s son, namely Israil II, and three descendants of previous sultans, Jamalul Kiram I,Footnote4 Aliyud Din II,Footnote5 and Alimud Din IV.Footnote6 Israil II was the direct heir to the throne and he had been chosen by his father to succeed him. However, it was Jamalul Kiram I who received the support of the ruma bichara. Both claimants benefited from a strong traditional authority recognised by different groups; Israil II was attached to the region of Patikul, in the north, and Jamalul Kiram I to Maimbung, in the south. This condition brought the sultanate to a situation where both claimants ruled, as sultans, from their respective places, whilst Aliyud Din II and Alimud Din IV maintained their power respectively in the localities of Buansa (Sulu) and Dungun (Tawi-Tawi) (Tuban Citation1994: 26).Footnote7

European competition and the question of sovereignty in the Sulu zone

While succession feuds were a constant feature of Sulu politics, the conditions in which they developed changed in the second half of the 19th century, when several foreign powers established themselves in the Sulu zone.Footnote8 The French and the Germans tried, without much success, to establish trading settlements in the Sulu archipelago (Irwin 1955: 109), and the British gained ground in North Borneo through the acquisition of the island of Labuan, acquired by Captain Mundy for the Crown in 1846 from the sultan of Brunei. This island, off the north coast of Borneo, formed a strong base from which to conduct the East India Company trading activities between the Strait Settlements and China. By extension, it was a competing trading centre for the Sulu sultanate, which had to contend with the Chinese traders of Labuan to share control of local trade and resources. When, in 1878, Sultan of Sulu Jamalul Azam (r.1862–1881) leased territories in the northern part of Borneo to Baron de Overbeck and Alfred Dent, who both represented a British company, it eased the extension of those competing trading networks from the Straits (Irwin 1955). In parallel, James Brooke had been working to promote British commercial and strategic interest in another part of Northern Borneo (Sarawak), which became an addition to the Straits Settlements in 1907 (Irwin 1955).

While the British presence was solidly established in the Sulu zone in the second half of the 19th century, the Spanish only settled there following several hundreds of years of failed occupation. Based on the Spanish version of the signed treaties, the Sultanate of Sulu – namely the island of Jolo and its dependencies – accepted in 1851 its incorporation to the Spanish crown (Escosura Citation1881: 377–384) and, in 1878, agreed to abandon its sovereignty (Saleeby Citation1908: 227). The Tausug version of the 1878 treaty presents, however, a different wording. It does not mention the sovereignty of Spain over Sulu but the exclusive obedience of its people to the king of Spain (Saleeby Citation1908: 228). Judging from other articles of the same treaty, which list several rights attributed to the sultan, the idea of a complete loss of sovereignty for the Tausug appeared contradictory to the content of the whole agreement.

A similar conclusion was reached by the Americans when the United States bought the Philippines from Spain in 1898. In his Senate speech, Senator Richard Pettigrew underlined that while Spain had sold the entire archipelago of the Philippines, in reality it only had effective domination over a part of it (Pettigrew Citation1900). The area to the south, encompassing much of the island of Mindanao and all of the Sulu archipelago, was only under partial Spanish military control because of protracted military campaigns, and the presence of a series of forts. In this context, the United States entered in a new agreement with the sultanate in 1899 through the Bates Treaty, which laid down the prerogatives of the sultanate and those of the United States.

The period from the 1880s to the 1910s was a time of intense political competition in the Sulu zone with intertwined trading and political interests of long term actors being challenged by the arrival of new powers. The following part shows that, over this period, the Sulu sovereigns display their image with a great awareness of the political situation. Costumes and self-representation were carefully chosen, depending on the moments and the powers to which Sulu wanted to ally.

The first photographs of the Sulu sovereigns in the 19th century: Malay and European models of authority

The first description of an audience given by a Sulu sultan is provided by the French doctor Joseph Montano while he was on a scientific mission in 1879. Montano, who was apparently well aware of the local customs, wrote a letter in Malay requesting an audience with Sultan Jamalul Azam (r.1862–1881). After a certain time without an answer, the German planter Herman Leopold Schück,Footnote9 who lived on the island, proposed to act as a facilitator and accompanied him to the palace. At their arrival, the sultan and part of his court were found doing shooting exercises. Montano gives the following account of his first impression:

The sultan, surrounded by his courtiers, is seated in a rich armchair under a rather poor nipa kiosk. Beside him stands his son Brahamuddin, looking intelligent and alert. Father and son are magnificently dressed in the richest satins from China; their kris and their rings are adorned with beautiful stones; their surroundings show much less luxury, except perhaps for the kris with finely chiselled handles are encrusted with pearls, diamonds and rubies; this entourage has a free but respectful attitude, and gives us uninviting looks. The sultan is grave and dignified, with easy manners; we greet each other, he sends for seats and the shooting continues.

The account of that visit is accompanied, in Montano’s book, by a drawing of the audience and the reproduction of a photograph of Jamalul Azam, the first one of a Sulu sultan (). We learn in the account that the sultan had been reluctant to have his photograph taken after several advisers objected to this portrait. However, when Jamalul Azam saw the photo of his son, which served as a test, appearing on a blank surface, he accepted with great enthusiasm (Montano Citation1886: 169–172). The image was not supposed to leave the island, or circulate among foreigners, for fear of magical use of it (Montano Citation1886: 172). It is therefore unclear if the photo was supposed to be shown only to the sultan’s followers, or also to visitors.

Figure 1. Sultan Jamalul Azam by M.M. J. Montano and P. Rey, 1879 (Montano Citation1886: 173).

Jamalul Azam appears posing, his two hands slightly on his hips, showing his rings and a sceptre in the right hand. He is wearing a dress similar in style to the ones of Malay rulers:Footnote11 a tied headgear on his head, a jacket of embroidered silk with flowery motifs, a straight collar with knot buttons inspired by Chinese design, and a large belt over it. As the photo is a half-length portrait, we may only infer that the ruler was wearing trousers under the visible sarong, as was the fashion at that time in other neighbouring sultanates.Footnote12 Indeed, the garments he was wearing reflect not only his access to international trading networks, and his related wealth and status, but also that he was part of the Malay cultural world, which shared a similar taste for textiles and ways to wear them.

A second account of an audience with Sultan Azam was narrated by the British John Foreman who joined a Spanish expedition sent to Maimbung, in 1881, to carry despatches from the Governor-General. The sultan is dressed:

in very tight silk trousers, fastened partly up with showy chased gold and gilt buttons, a short Eton-cut olive-green jacket with an infinity of buttons, white socks, ornamented slippers, a red sash around his waist, a kind of turban, and a kris at his side.

Shortly after, in the same year, Jamalul Azam passed away, leaving the sultanate in a succession feud during which Harun ar-Rashid (c.1886–1894), who was far from being the favourite contender, was officially installed sultan by the Spanish in 1886 at a ceremony in Manila. At that occasion:

… the Sultan-elect was dressed in European costume, and wore a Turkish fez with a heavy tassel of black silk. His Secretary and Chaplain appeared in long black tunics, white trousers, light shoes, and turbans. Two of the remainder of his suite adopted the European fashion, but the others wore rich typical Moorish vestments.

Figure 2. Sultan Harun Ar-Rashid in 1886 (Foreman Citation1899: 155).

It seems undoubtable that the fez was a way to add an Islamic note to the European dress. It may have been chosen because it was easily identifiable by European nations, as a Muslim attire but also because it was a visual symbol which emphasised Harun’s religious status and authority. The context of its realisation, carefully posed in a studio and with background decor, suggests that it was a well orchestrated self-representation which aimed to show the image of a charismatic ruler, one who could embrace European etiquette and who could therefore be entrusted by the Spanish colonial power. In the Malay peninsula, the incorporation of European elements in the sultan’s self-presentation was usually considered as a sign of political subordination by the British (Amoroso Citation2014: 11) and this may have been the Spanish perception as well. However, from a Tausug perspective, by presenting himself in foreign clothes, with a clear military accent, the sultan showcased his potential force, while the wearing of a fez enhanced his religious legitimacy, and implied his capacity to connect to a wider Muslim world.

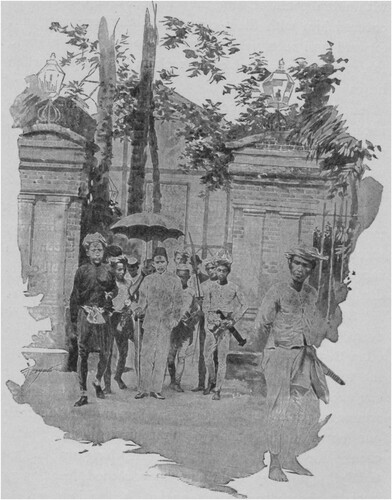

Another drawing, based on a photo, suggests that the fez had been adopted by Sultan Harun as part of his costume in Sulu too (). The scene shows him in European dress of simple style and clear colour, wearing a fez, as he was leaving the house of the General Arolas in Jolo. He is surrounded by young men heavily armed with barong (swords) and wearing native clothes, and one is holding an umbrella over the sultan, a symbol of royalty (Worcester Citation1899: 187). Sultan Harun, whose right to rule was contested, had adopted European fashion and a symbol of Islam attached to the Ottoman empire, as symbols of authority. Locally, he also used, a Malay and Tausug symbol of royal status: the umbrella.

Figure 3. Sultan Harun Ar-Rashid in Sulu (Worcester Citation1899: 187).

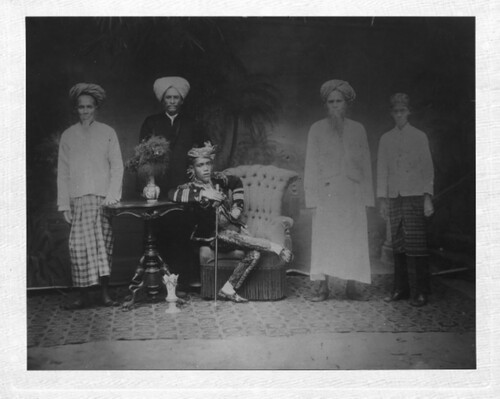

Sultan Harun was not the first to use non-local Muslim headgear. While the circulation of textiles and garments as trading product for the elite can be seen as a satisfying explanation for the changing appearance of the sultans, the combination of different pieces, and the political context in which they appear, point towards more complex calculation, reflecting the Tausug rulers’ political awareness and culture. For example, when the previous Sultan Badaruddin II (r.1881–1884) engaged in a long journey to perform the hajj (Majul Citation1973: 302), besides fulfilling a religious obligation, he was without doubt in search for religious legitimacy. He was only 20 years old, and such a journey was unusual enough for rulers in Sulu to be interpreted as a way to increase his charisma. One photo, which was widely circulated outside of Sulu,Footnote15 shows him surrounded by three haji wearing non-local turbans, and a young boyFootnote16 (). While the suite stands as supporting his religious authority, the sultan performs his authority along another repertoire. He is wearing embroidered silk pants and shoes, a black jacket of European inspiration and headgear. He appears very comfortable in a decor blending European elements, the table, chair and vase being typical of such photography studios. In the background, the depiction of coconut trees indicates that there has been no intention to project the sultan somewhere else than Sulu. Sat in a self-affirming position, Badaruddin II is installed in a large armchair, leaning his right arm on a table, his right leg posed horizontally on his left knee, and holding a cane straight in front of him. The composition and the staging use references to European, Malay, Arabic and Tausug cultures, the sultan being portrayed as central and familiar with those different worlds from where his authority derives.

Sultan Jamalul Kiram II and the constant reinvention of the sultan’s figure

The use of several registers of authority is characteristic of Sultan Jamalul Kiram II (r.1884–1936), whose reign saw the arrival of the Americans and a shift in power relation in the region. Jamalul Kiram II became sultan in Sulu a few years before his uncle Harun, mentioned previously, but he was only recognised by the Spanish in 1894. While the succession feud lasted for about a decade, Jamalul Kiram II was seen by external observers as the ‘true sultan’ (Worcester Citation1899: 172, 177) even before his official recognition because he benefited from a strong legitimacy through the Maimbung house and his father, the late Sultan Jamalul Azam (r. 1862–1881) (Saleeby Citation1908: 134, 137). While Harun was backed by Spanish military force, he could only count on a small number of supporters in Sulu, whereas Jamalul Kiram had, according to Spanish estimation, about 10,000 men (Worcester Citation1899: 173).

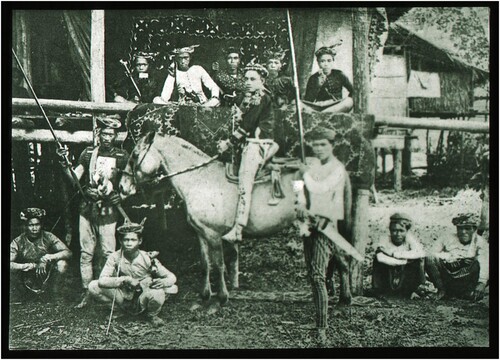

The first official photo of Jamalul Kiram II is undated but was taken during the concurring reign of Harun, and must therefore date from the period 1886–1894. The young Kiram is on a horse, in front of an elevated wooden terrace where several datu are seated and surrounded by servants, two of whom hold royal umbrellas ().Footnote17 He appears wearing a headgear, silk trousers, and a dark jacket which may have been of European inspiration as it seems embroidered on the shoulders, an uncommon feature for Tausug jackets (Worcester Citation1899: 177). The symbols of authority remain mainly local – either Tausug or Malay – which is the origin of the sultan’s traditional legitimate power.

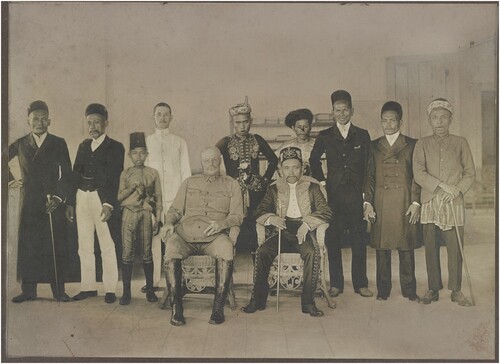

The American arrival, and the establishment of the special administration for the Muslim South and Sulu gave ample occasions for the sultan to appear in public. Numerous official visits were photographed in what may have been an effort, from the American side, to document the advancing cooperation, and ensuing integration, with the Sulu sultanate. In a picture taken during a visit to Governor-General Luke Edward Wright in 1905, Jamalul Kiram II appears in a costume of similar fashion, mixing European and local aesthetics. The black silk jacket introduced by Harun is adopted but worn open on a white shirt, and with large embroidering in front and on the sleeves (). The trousers are also black but with motifs on each sides which are of larger cut than what is traditionally worn in Sulu for men. Finally, the head cover chosen by the sultan is of local style, similar to the Malay songkok with intricate embroidered motifs, symmetrically placed with the crescent and the star, as symbols of Islam, in the central part. The sultan is photographed next to the military Governor of Sulu, Major Hugh Scott, on an equal stand, surrounded by a few Tausug officials and his interpreter Charles Schück, in European dress, while his guards, the only ones armed, are in traditional Tausug clothes. In this photo, the costume of Jamalul Kiram II shows an elaborate combination of European and local features merged into the new Sulu royal attire.

Figure 6. Sultan Jamalul Kiram II with Major Hugh Scott, Philippines, 1905. Library of Congress, LOT 7594 (4).

A totally different image appears in John Foreman’s account when he related his visit to Sulu in 1906, to meet Jamalul Kiram II, whose father he had met several years before. He reports the short meeting in these terms:

His Highness, the Majasari Hadji Mohammad Jamalul Kiram, reclining on a cane-bottomed sofa, graciously smiled, and extending his hands towards me, motioned to me to take the chair in front of him, whilst Mr. Schück sat on the sofa beside the Sultan. His Highness is about thirty-six years of age, short, thick set, wearing a slight moustache and his hair cropped very close. With a cotton sarong around his loins, the nakedness of his body down to the waist was only covered by a jábul thrown loosely over him. Having explained that I was desirous of paying my respects to the son of the great Sultan whose hospitality I had enjoyed years ago at Maybun, I was offered a cigar and the conversation commences. … From time to time a dependent would come, bend the knee on the royal footstool and present the buyo box, or a message, or whatever His Highness called for.

This account contrasts with what we know from Jamalul Kiram II’s public representation. He is the Sulu sultan that has been the most photographed. Pictures of him on official visits or being photographed in studio at a period around 1910s, all show a man exercising a great control of his image. While visiting the United States, the sultan was wearing black or white costumes, a simple songkok, and holding a cane on almost every occasion. The sobriety of his civil appearance was in accordance with the customs of the host country, which did not particularly value monarchy. A charismatic man, the photographs seem to reflect his understanding of the need to use and adapt his appearance to the different conditions in which he was. Another image of the sultan, taken in a studio, is of particular interest. The official costume chosen by Jamalul Kiram to be photographed reveals a changing strategy in his self-presentation. It shows him standing alone in front of a wooden chair and a table, which form the standard studio decor of that period, in a dignified attitude. He wears a European costume inspired from military uniforms with gold fringed shoulder epaulettes, a sash across his body and a sword. The only element of local colour is the embroidered songkok which is similar to the one worn in 1905 () with one notable difference. An important ornamental element has been added in the middle: a jigha, a feather plume encrusted in a piece of jewellery known to have been first used at the Mughal court.Footnote19 The exact source of inspiration is difficult to know as it may have been borrowed directly from a Mughal model or, more likely, be transmitted by rulers of the Malay peninsula who were wearing similar headdress. The Sultan of Kedah, Abdul Hamid Halim Shah (r.1881–1943) used to wear a jigha, and so did Sultan Abu Bakar of Johor (1886–1895), who was himself closely following and adapting the protocol used between Indian rulers and the British (Smith Citation2008: 347). During his visit to Turkey in 1893, he wore a feather plume on his head cover, although of different style. A photo and a drawing of him circulated since at least 1896 (Na Citation1896).

This renewed self-presentation has a deeper significance than simply wearing a richly adorned headcover as a sign of prestige. Sultan Abu Bakar managed to keep his sultanate relatively independent in encouraging economic development and engaging in successful diplomatic relations with foreign powers. His travels to Europe and his demand to use the prestigious title of maharaja, granted in 1868 by the British, can only be read as the acts of a fine strategist (Kwa Citation2006: 19–20). Whether Sultan Jamalul Kiram II meant to present himself to the British as the equal of a successful Malay sultan is a matter of speculation. However, it remains that Jamalul Kiram II presented himself using the same repertoire as Malay rulers of the peninsula, which is significant. In a photo that was destined to be circulated, it was the norm to carefully choose the costume and the pose in order to communicate an appropriate message. And in a period of colonial transition, it was important to project the image of a ruler perceived as modern, according to European criteria, while maintaining, if not enhancing, prestigious local status.

This was all the more important after 1915, when the Sulu sultan relinquished his temporal power through the signing of the Carpenter Agreement. While he kept sovereignty over North Borneo and full religious authority in Sulu and part of Mindanao, the agreement has been used as an argument to consider the sultanate abolished. The institution has, however, not been abandoned, as shown by the continuous succession and periodic claims over land rights on North Borneo (Beyer Citation1946). The most recent manifestation of the institution’s existence is the coronation of Muedzul-Lail Tan Kiram, one of the claimants to the throne.

Muedzul-Lail Tan Kiram and the recreation of a tradition

Muedzul-Lail Tan Kiram is one of the descendants of Mawallil Wasit, the brother of the last officially recognised sultan, Jamalul Kiram II.Footnote20 As very often in the history of the sultanate, the succession of Jamalul Kiram II did not take place without problems, which created the ground for several claims afterwards. Besides the fact that the Philippine Commonwealth (1935–1946) did not recognised the possibility of succession – the sultanate being considered abolished – the sultan did not leave direct male descendants. His brother, Mawallil Wasit, was therefore supposed to be proclaimed sultan but he died shortly before. Two of Sultan Jamalul Kiram’s three daughters proposed their respective husbands as sultan: Dayang-Dayang Hadji Piandao Kiram suggested her husband, Datu Ombra Amilbangsa, and Putli Tarhata Kiram, her husband, Datu Buyungan. Concurrently, the descendant of Mawallil Wasit, Esmail Kiram I, claimed his rights to succession.

Despite the absence of effective political roles, several descendants from these three branches, and others based on older claims, continue to ask for their rights to head the sultanate.Footnote21 The matter goes far beyond a family affair or quarrel over an old and defunct form of governance, as the Sulu sultanate had legal, albeit controversial, grounds to claim rights over Sabah.Footnote22 Because of that, Manila has shown signs of supporting the recognition of the sultanate, first in 1962 under President Macapagal, then in 1974, when Ferdinand Marcos officially recognised Sultan Mahakuttah KiramFootnote23 (r.1974–1986) as the rightful ruler of the sultanate during a coronation ceremony that was widely reported at the time.

The few visual archives, and the organisational details about the event are helpful in understanding the form of the protocol, and its origins. The ceremony was not only attended by the Philippines president but also coordinated by Malacañang with local committees in Zamboanga and Jolo, among whom representatives of the Bank of the Philippines were in charge of the preparation, which suggests that the expenses were covered by Manila, allowing for a celebration of the expected standard.Footnote24 The photos which circulated were of two types. The first ones showed Sultan Mahakuttah Kiram in the presence of President Marcos and government officials in an office which illustrated the legal authority gained through the unexpected presidential support. Another showed Mahakuttah Kiram wearing the same attire, this time seated on a throne, in a room decorated with local tapestries and a royal umbrella over him. The sultan wore a white shirt and black European costume with simple embroidery of very marked Western touch, with only a local twist. For the sultanate, the presidential order meant the possibility of existence for the institution within the Republic of the Philippines, although a fragile one due to the martial law context.

As mentioned, Muedzul-Lail Tan Kiram (r. 2012–) is one of Sultan Mahakuttah’s sons and his designated heir (raja muda). He can therefore claim legal authority over the sultanate. However, as the political conditions were unfavorable when his father passed away, Muedzul-Lail Tan Kiram waited 26 years before declaring himself sultan, which weakened his legitimacy. After such a long hiatus in the succession, there was a need to work at regaining authority, particularly as other contenders had asserted competing rights.Footnote25 The new self-proclaimed sultan set up an impressive strategy to establish his image internationally, and support his claim locally.

The institution – renamed Royal and Hashemite Order of the Pearl – claims that it ‘continues the traditional customs and magnificence of the Royal Sultanate of Sulu and the Sultan’s Royal Court’. However, as it has been shown, such customs were far from being a fixed set of elements. The Royal and Hashemite Order of the Pearl did invent the existence of a tradition, and remodelled it following dynastic chivalric orders founded in medieval Europe (Riol Citation2013: 1). By using them as a model, the sultanate found a way to avoid the problematic question of the existence of a Muslim state within the Republic of the Philippines. Indeed, dynastic orders are under the exclusive control of a monarch and independent from a political order. This strategic choice opened the way to two new usages: the participation in a global network of royalties loosely connected through events and mutual recognition, and the creation of a new heraldic language which serves to achieve international recognition.

The informal network of royalties is formed by families in a similar position as that of the Sulu sultanate, that is, they have been diluted in modern states, which have often rendered them inactive such as in Ethiopia, Ghana, Hawaii, Turkey, or Austria.Footnote26 Besides mutual recognition with other royalties through the issuance of certificates, the sultanate of Sulu has set up a system of membership open to anyone having rendered a substantial service to the sultanate, regardless of place of origin or residence. By doing so, the sultan gains strategic supporters in addition to the ones who recognise, in Sulu, his traditional authority. However, contrary to traditional hierarchy in the sultanate administration, the six grades of the Order have mostly a representation role.Footnote27

As for the heraldic vocabulary, it uses symbols belonging to European heritage as well as those associated with the Sulu sultanate. The coat of arms of the Order has, for example, a crown-topped shield, which is a widespread insignia in European heraldry (Gallop Citation2018: 135). It is represented by a green gonfanonFootnote28 which is wrapped and twisted in the form of a shield. Within it are inserted several elements belonging to different heraldic traditions. It combines pictorial devices associated with Islam such as the star and the crescent, or the bifurcated sword (zulfikar) – with others related to the sultanate of Sulu. The latter include a Bornean roofed boat topped with a royal umbrella, a gateway represented as two pillars on a doorstep (the door to Mecca), a songkok and the pearl (inserted into the bifurcated sword and the songkok), traditionally associated with the sultanate known for pearl culture. Both the door to Mecca and the pearl have been part of the royal insignia in previous periods. Pre-19th century flags of the sultanate show a pearl at the centre of a stylised square motif with ornamental volutes on its four corners probably representing the Mecca door. As for the vinta boat (traditional outrigger), it can be found in previously known coat of arms during the American administration (Heisser Citation1997). A reference to the Malay sultanates is also found in the two creatures with a tiger head and fish body (), probably inspired by the tigers present in both the coat of arms of Johor state (Malaysia) and that of Malaysia.

Figure 7. The official coat of arms of the Royal Sultanate of Sulu and North Borneo. Courtesy of the Sultan of Sulu, <www.sultanateofsulu.org>

Those carefully chosen symbols, which refer to different centres of authority, have been designed by the Russian heraldic artist Michael Medvedev, who is also the chairperson and the founding member of the Russian-based guild of heraldic artists. Medvedev is one of the foreigners working for the sultanate, along with Aleksandar Bačko (Citation2015), a writer, journalist and genealogist from Belgrade, who wrote about the Sulu blazons and armorial insignia. It may be inferred that the sultan came to know them through his effort to connect to royal houses around the world, as well as different organisations safeguarding those traditions. Indeed, since 2010 Muedzul-Lail Tan Kiram has been reaching out to princes and heraldic societies all over the world in search of international recognition. The Order has been officially acknowledged by organisations such as the Augustan SocietyFootnote29 and the Associazione Insigniti Onorificenze Cavalleresche. It has also received distinctions such as the Grand Collar of the Order of the Ethiopian Lion, and the one of the Order of Ibrahim Pascha granted by Prince Osman Rifat Ibrahim of Egypt and Turkey.Footnote30

Locally, Muedzul-Lail Tan Kiram has concentrated his efforts on two symbolic events: his coronation and the coming renovation of the royal palace in Maimbung. For his coronation, the sultan adopted an interesting piece of clothing, a black jacket of Chinese design bearing two large symmetrical golden dragons on it.Footnote31 China appears as another centre of authority, one which may be tentatively reactivated, centuries after the end of diplomatic contacts and at a time when China is an important player in the South China Sea. However, the reference to China was short-lived and abandoned after the coronation. Indeed in the majority of the official photos, the sultan appears in Malay and Tausug attire, comprising trousers, an embroidered open jacket, a kris slipped in a belt, and a turban with an ornamental pin in the shape of a crescent and a moon. In addition, the honorific title ampun is included before the sultan’s name, a direct reference to the Malay usage. It is moreover preceded by HM (His Majesty). While both usages were unknown in Sulu previously,Footnote32 it is interesting to note that symbols of authority deriving from the Malay neighbours are not new. However, this periodic usage of Malay fashion is here analysed as being less a development of an immemorial tradition than a controlled usage of a political language referring to a neighbouring state, Malaysia, where the system of sultanate has not been abolished.

The second local event in which the sultan has invested considerable effort and in which the symbolic dimension is evident is the reconstruction of the royal palace. Places of residence have been numerous in the history of the sultanate and the palace of Maimbung was the one inhabited by Jamalul Azam and described in the traveller’s accounts mentioned earlier. The rebuilt astana, named Darul Jambangan, is an elevated wooden structure on pillars with two storeys. The imposing building is designated as a symbol of authority, power and state governance in the video made by the sultanate in 2016 to promote it.Footnote33 It is also a tangible trace to the past, and a visible mark that the sultanate tradition is being revived. However, as of 2023, the project has remained in the state of an idea and does not seem to have found the necessary competences and finance to be realised.

Concluding remarks: reinvention and continuation of tradition in the Sulu sultanate

While not yet realised, the palace continues to be used as a symbol. Old images of the astana are presented together with the new architectural project, in the same way as those of the previous sultans are periodically published, but now in social media, with the one of Sultan Muedzul-Lail Tan Kiram. By doing so, the Royal House of Kiram presents a tradition of preserving a heritage – as a guarantee that the present is not severed from the past. Their echoes of past splendour render them authoritative, and, such an authority is what is looked for by Muedzul-Lail Tan Kiram.

However, this presented continuity is less linear that it seems, as shown by the different coronation ceremonies discussed previously. Traditions were never a constant set of stable elements, but were periodically reinvented based on old and reinterpreted materials, or simply created out of different traditions. This combination of signifiers was meaningful at the moment of their formulation, and to remain so, it needed to be periodically updated.

In Sulu, the royal tradition was in large part a conscious choice of elements which serve the grammar of political legitimacy and its revival can be understood along the same lines. Tradition is the ally of authority, it participates in its recognition and may as well feed power. In the case of a deficit of authority, or to simply maintain it, its use creates legitimacy. This is the case of the coronation ceremony, in which a carefully prepared representation creates the condition for the recognition of traditional and charismatic authority. In Sulu, tradition is always re-enacted, and does not follow old and immemorial rituals. However, it also always relies on a set of elements that are recognisable and meaningful for the people of the sultanate. This is true for other royal traditions in Europe or in Southeast Asia, which are de facto always reinvented over time (Cannadine Citation2012 :101–164).

The way tradition is used opens a window on the political culture of the sultanate. Symbols and practices form a language that answers the political context in which it is deployed. The traditional attire of the sultans is significant because it is a public display that claims, through appearance, which powers the sultan wished to identify with. Considered in that way, traditional costumes, reinvented or not, form a rich source of information about the political climate at key periods of the succession to the throne. In Sulu, the design of clothes and the ornamental features, far from being random aesthetical features, form a semiotic that needs to be understood in the context of competition between claimants, the non-recognition by the state, and the periodically changing geopolitical context of the Sulu zone.

One could ask how far new tradition can use old materials and in which proportion its renewal is possible. In other words, how far can a tradition be reinvented, at which pace, and is there any risk of losing part of the cultural heritage? The new heraldic vocabulary introduced by Sultan Muedzul-Lail Tan Kiram represents a far greater innovation than what had been done by previous sultans. It is predominantly new, and despite the use of the insignia which belongs to Sulu and the Malay world, the creation of the Royal Order of the Pearl and its rules are foreign to the region. The membership and heraldic privileges, which aim at enhancing the prestige of the Royal House of Kiram, change the form of the political institution by creating a new hierarchy.

To know whether the changes introduced over the past 10 years form a break with the past, one must consider a letter from the 19th century, in which the sultan Jamalul Kiram II is said to be ‘free to give honor to anyone, even the small person [and] interpret as he likes the customary law pa-alun limayasa in the community he rule[d]’ (Tan Citation2005: 51). This letter indicates that, as important as the changes have been over the past 10 years, they arise from a pre-existing framework which allowed such flexibility since at least the 19th century. When considered over a long time period, the reinvention of tradition initiated by Sultan Muedzul-Lail Tan Kiram follows changes in the protocol, such as incorporation or inspiration from European elements, and contribution of foreigners to the chancellery, which were common in Sulu and in other Southeast Asian sultanates. As shown through the few examples related to the sultans’ attire, the evolution of royal tradition is a historical fact, and modifications do not appear to have radically or permanently changed pre-existing practices and aesthetic models, which are being transformed in order to be maintained.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Elsa Clavé

Elsa Clavé is assistant professor for Austronesian Studies (Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines) at the Department for Southeast Asian Languages and Cultures, University of Hamburg, and member of the Centre for the Study of Manuscript Cultures (CSMC) at the same university. She specialises in the cultural history of the Malay world and has worked extensively on the southern Philippines. Her most recent publication, Les sultanats du Sud philippin: une histoire sociale et culturelle de l’islamisation (XV e–XX e siècles) [The sultanates of the southern Philippines: a social and cultural history of Islamisation (15th to 20th century)] was published by EFEO, 2022. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 Notions and practice of authority, power, and force, although closely interrelated, remain distinct from each other.

2 For this occurrence and the others, original in German, translation by the author.

3 Ruma bichara designates a council in Sulu but is a title in Sumbawa (Indonesia). The common origin of both terms may be in Makassar (Henri Chambert-Loir, pers. comm., 2012).

4 Jamalul Kiram I was the son of Sultan Alimud Din III (r.1778–1791) and the grandson of Dayang-Dayang Piandao (daughter of Sultan Sharifud Din). As the system of descent is bilateral in Sulu, both the maternal and paternal lines are of importance, thus Jamalul Kiram I had a strong claim although his father, Alimud Din III, had been named sultan by his mother Dayang-Dayang Piandao, but not being recognised by the ruma bichara, his power was limited to Maimbung (Tuban Citation1994).

5 Aliyud Din II was the son of Sultan Aliyud Din I (r.1808–1821).

6 Alimud Din IV is the grandson of Sultan Israil I (r.1774–1778). The Dungun branch began with Badarud Din, his great-great-grandfather.

7 Those centres of power are periodically activated as shown by the following succession crisis in 1881. For a detailed account see Suva (Citation2020).

8 The expression, coined by James Warren (Citation2007: xiii, xxvii–xviii), designates an area which extension varied, in time, with the influence of global economy. It encompasses the Sulu archipelago, the southern coast of Mindanao, North Borneo, North Sulawesi, and the maritime space of the southern Philippines.

9 Herman Leopold Schück arrived in the Philippines from Germany as a merchant mariner. He then settled in Jolo, Sulu, where he became a coffee planter, and a close acquaintance of the sultan (Montemayor Citation2005).

10 Original in French, translation by the author.

11 While fashion varied from one sultanate to another, traditional Malay dress was composed of a jacket, trousers and a sarong (Milner Citation1982: 2–3).

12 Those do not appear in the portrait but in a drawing, probably based on a photo, of the audience.

13 Named kandit or kambut, Sulu sashes were used as protective girdles by Sulu men (Sakili Citation2003: 162).

14 In the Philippine archipelago, the use of a stick or form of a sceptre as a symbol of authority was not always in relation to Spanish influence.

15 PP MS 26/3/1/1 (SOAS archive).

16 I thank Cristina Juan for the metadata provided (pers. comm., 20 January 2022). The names are known thanks to a letter from Haji Butu, minister of Sulu, to Ifor Ball Powell, who was enquiring about the people on the image. They are (left to right): Hadji Bandahali, Hadji Omar, the Sultan of Sulu Badaruddin II, Hadji Samla, and Samania, the son of Hajdi Omar.

17 The photo is also reproduced in Worcester (Citation1899: 177).

18 Similar to the Malay sarong.

19 Known as jigha or kalgi in the Indian subcontinent, this bejewelled plume fixed to the turban was brought to India by the Mughals. Before that Hindu and Muslim kings were wearing turban ornament of a different style.

20 Line of Succession of the Sultans of Sulu of the Modern Era, Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines, 26 February 2013. <https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/2013/02/26/line-of-succession-of-the-sultans-of-sulu-of-the-modern-era/> Accessed 4 February 2024.

21 The present situation results from several divisions of the initial line of descents. Five of the contenders to the throne with the strongest claim formed, in 2016, the Royal Council of the Sulu Sultanate in order to speak with one voice regarding political issues concerning the sultanate, especially in the frame of a new autonomy planned for the Southern Philippines. It is formed by Sultan Ibrahim Q. Bahjin, Sultan Muedzul-Lail Tan Kiram, Sultan Mohammad Venizar Julkarnain Jainal Abirin, Sultan Muizuddin Jainal Abirin Bahjin, and Sultan Phugdalun Kiram II. Mindanews, 30 May 2016. It is unclear whether the council have a hold in time.

22 In 2021, the heirs of the Sulu sultanate, who appear to be represented only by the descendants of Jamalul Kiram II won an arbitration case over the lease of Northern Borneo to Malaysia. The case, ruled by a court in Paris, ordered Malaysia to pay 62.59 billion ringgit to the Sulu descendants. It was dismissed in 2023 by the Paris Court of Appeal.

23 Son of Sultan Mohammed Esmail whose reign was marked by effort regarding the question of Sabah.

24 Memorandum Order no. 487. <https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/downloads/1974/05may/19740510-MO-0427-FEM.pdf> Accessed 4 February 2024.

25 The most known is Jamalul Kiram III, who also proclaimed himself sultan and had enough supporters to briefly take over a village in Sabah (Malaysia) which caused a tense armed confrontation in February 2013.

26 <https://sultanateofsulu.ecseachamber.org/honours-and-awards/index-1.htm> Accessed 4 February 2024.

27 The Order has six grades with respective specific rights regarding the use, display and organisation of the insignia.

28 Although difficult to recognise at first sight on the coat of arms, the gonfanon stands for a sambulayan, a traditional sail flag in Sulu. For a description of the heraldic symbols, see Royal House of Kiram <https://sultanateofsulu.ecseachamber.org/royal-house-of-kiram/index-1.htm> Accessed 4 February 2024.

29 Composed of scholars in chivalry, heraldry, nobility, and royalty.

30 The list of the bestowed titles is long and includes honorific titles and certificates of appreciation from Rwanda (2011), Hawaii (2016) and Belgium (2017). <https://sultanateofsulu.ecseachamber.org/honours-and-awards/index-1.htm> Accessed 4 February 2024.

31 The royal house of Sulu, Facebook account. <https://www.facebook.com/sulusultanate/photos/his-majesty-muedzul-lail-tan-kiram-the-35th-sultan-of-sulu-and-north-borneo-his-/1724989377519317/> Accessed 4 February 2024. Images of the coronation consulted in 2021 are no longer available.

32 In official letters from the 19th century, Sulu sultans traditionally refer to themselves as Paduka Mahasari Maulana Sultan Hadji. For letters by Sultan Badaruddin see Undescribed letters from Sulu, PP MS 26/04/03, transcribed by the Jawi Transcription Project. For letters by Jamalul Kiram II, see Tan (Citation2005).

33 The Royal Astana (Royal Palace) Replica Project of Sulu Sultanate (Ron Seyer) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XZwppSzu4Jg&t=2s> Accessed 4 February 2024.

References

- PP MS 26/3/1/1 Papers of Ifor Ball Powell, Miscellaneous Materials, Photographs. <https://digital.soas.ac.uk/IBP0000006/00001/> Accessed 4 February 2024.

- PP MS 26/04/03 Undescribed letters from Sulu.

- LOT 7594 (4) Major Hugh Scott, Military Governor of the Sulu Archipelago, Philippines, Sultan Jamalul Kiram II, interpreter Charles Chuck, and local government officials and hadjis, dressed to call on Governor General Luke Edward Wright. <https://www.loc.gov/item/2016650207/> Accessed 4 February 2024

- Amoroso, Donna J. 2014. Traditionalism and the ascendancy of the Malay ruling class in colonial Malaya. Singapore: SIRD & NUS Press.

- Bačko, Alexandar. 2015. Sultanate of Sulu. Notes from the past and present times. Belgrade: author. <https://porodicnoporeklo.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/aleksandar-backo-sultanate-of-sulu.pdf> Accessed 4 February 2024.

- Beyer, Otley. 1946. Brief memorandum on the Government of the Sultanate of Sulu and Powers of the Sultan during the 19th Century, Borneo Records, Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Manila: Department of Foreign Affairs. <https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/1946/12/08/brief-memorandum-on-the-government-of-the-sultanate-of-sulu-and-powers-of-the-sultan-during-the-19th-century/?__cf_chl_tk=SNkO3n8vjhYLtPaNFpXDEw1_5v9wdS_TxXyTsTar9A0-1707311690-0-zQ7Q#> Accessed 4 February 2024.

- Cannadine, David. 2012. The context, performance and meaning of ritual: the British monarchy and the ‘invention of tradition’, c. 1820–1977. In Eric Hobsbawn and Terence Ranger (eds), The invention of tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 101–164.

- Escosura, Patricio de la. 1881. Memoria sobre Filipinas y Jolo [Memory on the Philippines and Jolo]. Madrid : Imprenta de Manuel G. Hernandez.

- Fernando-Amilbangsa, Ligaya. 2005. Ukkil: visual arts of the Sulu Archipelago. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

- Fiske, Amos Kidder. 1898. The story of the Philippines: a popular account of the islands from their discovery by Magellan to the capture by Dewey. New York: Mershon. <https://quod.lib.umich.edu/p/philamer/ADE3375.0001.001?rgn=main;view=fulltext#ADE3375.0001.001-00000013> Accessed 4 February 2024.

- Foreman, John, 1899. The Philippine islands: a political, geographical, ethnographic, social and commercial history of the Philippine archipelago, embracing the whole period of Spanish rule, with an account of the succeeding American insular government. London: Sampson Low, Marston & Co.

- Gallop, Annabel Teh. 2018. Power in images: European heraldry and Islamic seals from Southeast Asia. In John Cherry, Jessica Berenbeim and Lloyd de Beer (eds), Seals and status: the power of objects. London: British Museum, pp. 133–140.

- Heisser, David C.R. 1997. Crescent, kris and vinta: the arms and seals of Mindanao and Sulu. Flag Bulletin 36 (5): 196–212.

- Irwin, Graham. 1995. Nineteenth-century Borneo: a study in diplomatic rivalry. ‘s-Gravenhage: Martinus Nijhoff.

- Jawi Transcription Project < https://fromthepage.com/mulaika/jawi-transcription-project/> Accessed 4 February 2024.

- Jouvenel, Bertrand de. 1957. Sovereignty: an inquiry into the political good. Translated by J.F. Huntington. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Kojève, Alexandre. 2004. La notion de l’autorité [The concept of authority]. Paris: Gallimard.

- Kwa, Chong Guan. 2006. Why did Tengku Hussein sign the 1819 treaty with Stamford Raffles? In Khoo Kay Kim, Elinah Abdullah, and Wan Meng Hao (eds), Malay Muslims in Singapore: selected reading in history. Singapore: Pelanduk/RIMA, pp. 1–36.

- Majul, Cesar Adib. 1965. Political and historical notes on the old Sulu sultanate, Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 38 (1): 23–42.

- Majul, Cesar Adib. 1973. Muslims in the Philippines. Quezon City: University of the Philippines.

- Milner, Anthony. 1982. Kerajaan: Malay political culture on the eve of colonial rule. Tucson AZ: University of Arizona Press.

- Montano, Joseph. 1886. Voyage aux Philippines et en Malaisie [Journey to the Philippines and Malaysia]. Paris: Lib. Hachette et Cie.

- Montemayor, Michael Schuck. 2005. Captain Herman Leopold Schück : the saga of a German sea captain in 19th century Sulu-Sulawesi seas. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

- Na, Tien Piet. 1896. Shaer Almarhoem Beginda Sultan Abubakar di Negri Johor. Singapore: s.n.

- Paredes, Oona. 2013. Mountain of difference: the lumad in early colonial Mindanao. Ithaca NY: Cornell University, Southeast Asia Program Publications.

- Pettigrew, E.F. 1900. Treaty with the Sultan of Sulu. Information concerning the Philippines islands. Speeches of Hon. E.F. Pettigrew, of South Dakota, in the Senate of the United States (Washington, 17, 24, 10 January 1900). <https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/public/gdcmassbookdig/treatywithsultan00pett/treatywithsultan00pett.pdf> Accessed 4 February 2024.

- Riol, D.J. García. 2013. El sultanato de Sulú y la real y Hachemita Orden de la Perla [The Sultanate of Sulu and the royal and Hashemite Order of the Pearl]. Madrid: Sociedad Heráldica Española.

- Sakili, Abaraham P. 2003. Space and identity: expressions in the culture, arts, and society of the Muslims in the Philippines. Diliman: Asian Center, University of the Philippines.

- Saleeby, Najeeb M. 1908. History of Sulu. Manila: Bureau of Printing.

- Smith, Simon C. 2008. Conflict and collaboration: Britain and Sultan Ibrahim in Johore, Indonesia and the Malay World 36 (106): 345–358.

- Suva, Cesar Andres Miguel. 2020. In the shadow of 1881: the death of Sultan Jamalul Alam and its impact on colonial transition in Sulu, Philippines from 1881–1904, TRaNS: Trans -Regional and -National Studies of Southeast Asia 8: 85–92.

- Tan, Samuel K. 2005. Surat Sug. Letters of the Sultanate of Sulu. Kasultanan, Vol I. Manila: National Historical Institute.

- Tuban, Rita. 1994. A genealogy of the Sulu sultanate. Philippine Studies 42 (1): 20–38.

- Warren, James F. 2007. The Sulu Zone: the dynamics of external trade, slavery, and ethnicity in the transformation of a Southeast Asian maritime state 1768–1898. Singapore: NUS Press.

- Weber, Max. 1980. Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft: Grundriß der Verstehenden Soziologie, fünfte revidierte Auflage [Economy and society: outline of understanding society]. Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck).

- Worcester, Dean C. 1899. The Philippine islands and their people; a record of personal observation and experience, with a short summary of the more important facts in the history of the archipelago, New York/London: Macmillan Company. <https://digital.library.cornell.edu/catalog/sea211> Accessed 4 February 2024.

- MindaNews. 2016. Royal Council of the Sulu Sultanate to present stand on Sabah and Federalism soon, 30 May. <https://mindanews.com/top-stories/2016/05/royal-council-of-the-sulu-sultanate-to-present-stand-on-sabah-and-federalism-soon/> Accessed 4 February 2024.

- Office of the President of the Philippines. 1974. Memorandum Order no.487. <https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/downloads/1974/05may/19740510-MO-0427-FEM.pdf> Accessed 4 February 2024.

- Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Line of succession of the sultans of Sulu of the modern era. <https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/2013/02/26/line-of-succession-of-the-sultans-of-sulu-of-the-modern-era> Accessed 4 February 2024.

- Royal and Hashemite Order of the Pearl of the Sultanate of Sulu.

- Honours and Recognition. <https://sultanateofsulu.ecseachamber.org/honours-and-awards/index-1.htm> Accessed 4 February 2024.

- Royal House of Kiram. <https://sultanateofsulu.ecseachamber.org/royal-house-of-kiram/index-1.htm > Accessed 4 February 2024.

- Symbols of the Sultanate. <https://sultanateofsulu.ecseachamber.org/symbols-of-the-sulu-sultanate/index-1.htm > Accessed 4 February 2024.

- Royal House of Sulu. Facebook. <https://www.facebook.com/sulusultanate/photos/his-majesty-muedzul-lail-tan-kiram-the-35th-sultan-of-sulu-and-north-borneo-his-/1724989377519317/> Accessed 4 February 2024.