ABSTRACT

Countering the intuitive notion that family members contribute to the success of entrepreneurship in the tourism sector, we found that their involvement does not necessarily result in favourable outcomes from the angle of advice seeking. To uncover the effects of family members as advisors, we draw on the attention-based view of the firm to investigate the influence of advisor familiness on entrepreneurial orientation. We collected 447 valid responses from Chinese tourism entrepreneurs. Results from a hierarchical multiple regression analysis showed a significant and negative effect of advisor familiness on entrepreneurial orientation. Significant moderating effects were also detected from entrepreneurs’ gender, education level and age. Specifically, entrepreneurs’ age enhanced the negative effect whilst entrepreneurs’ gender and education level attenuated the negative effect.

1. Introduction

Tourism is a rapidly growing industry, offering ample opportunities for tourism entrepreneurship (Kallmuenzer & Peters, Citation2018). Examining the factors that contribute to entrepreneurial success, a key element is entrepreneurs’ attention to pursuing risk-taking, innovative and proactive strategies, i.e. entrepreneurial orientation (EO) (Fadda, Citation2018; Van Doorn et al., Citation2017). EO measures the degree to which a firm adopts risky, innovative and proactive strategies (Wales et al., Citation2020) and is considered to be one of the most valuable constructs to explain tourism firm performance (Fadda, Citation2018; Fadda & Sørensen, Citation2017; Peters & Kallmuenzer, Citation2018). Notwithstanding its importance, scholarly inquiry into EO within the tourism sector remains conspicuously limited (Fadda, Citation2018), although some tourism scholars indeed strived to probe into the antecedents of EO, elaborating on the effects of tourism core competence (Tang et al., Citation2020), social capital and knowledge management, and performance measurement and leadership (Liu & Lee, Citation2019).

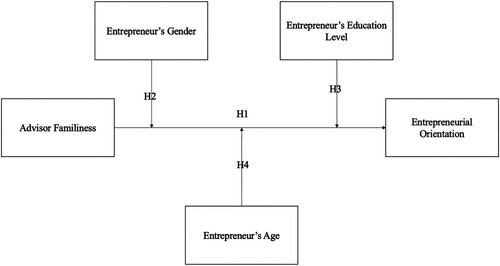

Despite the emerging array of research on the antecedents of EO in tourism, it is surprising to see that limited attention has been given to studying the effects of advice seeking with family members, and the effects of entrepreneurs’ characteristics in influencing entrepreneurs’ attention to prioritise EO (Ma et al., Citation2020), since from the attention-based view, advice seeking and entrepreneurs’ characteristics may influence their attention to prioritise certain strategies (Ocasio, Citation1997; Van Doorn et al., Citation2017). To complement this gap, this study introduces a conceptual framework focusing on how advisor familiness may shape entrepreneurs’ attention to EO strategies, and the corresponding moderating effects of entrepreneurs’ age, gender and education level, offering fresh perspectives on how seeking advice from family members (advisor familiness) may shape the inherent nature of their strategic attention (e.g. EO), and how entrepreneurs’ gender, age and education level may moderate the effects of advisor familiness on EO. By offering answers to the inquiries, the study opens a novel avenue for studying family members, entrepreneurs’ characteristics and EO in tourism entrepreneurship research.

Tourism entrepreneurs associate frequently with family members (Zeng et al., Citation2022). Existent research on the influence of family members on entrepreneurship centred upon emotional, financial and labor support, with information support, for example, advice seeking with family members being underexplored (Van Doorn et al., Citation2022a). However, unlike managers in large organisations with resources to access professional services, tourism entrepreneurs leading SMEs, constrained by budget limitations, primarily rely on free advice from personal contacts among their connections, which provides crucial information support influencing their attention to EO (Cross et al., Citation2001). Family members are the first resort for most entrepreneurs to seek help, and their advice usually has a high weight in entrepreneurs’ strategic decision-making (Aldrich & Cliff, Citation2003). Despite the importance of advice seeking with family members, research regarding advice seeking with family members is scarce (Ma et al., Citation2020). To address this gap, we created the concept of advisor familiness to measure the degree of family involvement in entrepreneurs’ advice seeking.

Furthermore, entrepreneurs’ gender, education level, and age are pivotal in the context of family involvement in influencing entrepreneurs’ attention to pursue EO. Entrepreneurs’ characteristics will significantly influence entrepreneurial strategy (Van Doorn et al., Citation2022b). While both internal and external factors offer stimuli (e.g. advice network), the interpretation and impact on strategic decisions are shaped by entrepreneurs’ cognitive processing, which is influenced by their backgrounds (Van Doorn et al., Citation2017). In essence, factors like gender, education, and age are crucial as they mould the cognitive frameworks of entrepreneurs, subsequently influencing the strategic direction and success of their ventures (Heyden et al., Citation2013; Van Doorn et al., Citation2013). Understanding these factors is important not just in theory, but also has practical value in forecasting tourism firm performance.

Given the research gaps in extant literature and the practical relevance of the gaps, the study endeavours to address two pivotal research queries by surveying 447 tourism entrepreneurs: (1): What is the relationship between advisor familiness and EO? and (2) how do entrepreneurs’ personal characteristics, such as gender, education level and age, moderate the relationship between advisor familiness and EO?

By answering the research questions, the study endeavours to offer theoretical contributions to tourism entrepreneurship literature and the attention-based view through the lens of advice seeking, EO and entrepreneurs’ characteristics. First, the study seeks to enrich the advice seeking and EO literature from a familiness perspective, being among the first to identify advisor familiness as an antecedent to EO. Through this finding, the study also contributes to the attention-based view by offering insights into how advisor familiness manners entrepreneurs’ attention to EO. Second, the study seeks to contribute to advice seeking and EO literature as well as to the attention-based view by unveiling the role of individual traits including gender, education level, and age in moderating the relationship between advisor familiness and EO.

2. Literature review and conceptual development

2.1. Attention-based view

The attention-based view posits that firm-level strategic behaviour is shaped by the focused attention of entrepreneurs to allocate the firms’ strategic resources to pursue certain strategies (Ocasio, Citation1997). Entrepreneurs’ attention to prioritise certain strategies can be interpreted as a function of external information input (e.g. advice seeking) and internal individual characteristics (Van Doorn et al., Citation2017). In tourism firms, entrepreneurs’ advice seeking from their personal contacts serves as an important resource of knowledge that shapes entrepreneurs’ knowledge base and the attention to strategic priority (Van Doorn et al., Citation2013; Zeng et al., Citation2022). Henceforth, the attention-based view is suitable for exploring how factors like entrepreneurs’ advice seeking and demographic attributes, such as gender, educational level, and age, can impact their prioritisation of such entrepreneurial strategies as innovation, risk-taking, and proactiveness (Van Doorn et al., Citation2013).

2.2. Entrepreneurial orientation

As an important precursor to tourism firm performance (Fadda, Citation2018; Tajeddini et al., Citation2020), EO received limited attention in tourism studies but however is one of the most studied concepts in entrepreneurship (Rauch et al., Citation2009). Miller (Citation1983) was among the first to propose the concept of EO (e.g. making innovation on products and services, devising risky strategies, and proactively innovating to meet competition). Since its introduction in 1980s, EO has attracted considerable academic attention and its weight in achieving superior firm performance has been supported by a myriad of studies (Covin & Slevin, Citation1989; Tajeddini et al., Citation2020). It may be arguable that EO has different dimensions (Wiklund & Shepherd, Citation2005); however, it is generally accepted that proactiveness, innovativeness and risk taking are the three key EO dimensions (Van Doorn et al., Citation2017).

More specifically, proactiveness involves encouraging initiative and exploiting opportunities in tourism firms (García-Villaverde et al., Citation2021; Miller, Citation1983). Such proactive tourism firms innovate and develop products and services ahead of their competitors to prepare for future market change (Van Doorn et al., Citation2017). These moves help tourism firms to assume a first-mover advantage, charging premium price and avoiding competitors at the early stage (Tajeddini et al., Citation2020). Henceforth, most tourism entrepreneurs view proactiveness as a critical strategic posture for entrepreneurial tourism firms (Kallmuenzer & Peters, Citation2018).

Innovativeness refers to the pursuit of novel approaches, new technologies, and new products and services, necessitating the commitment of resources and potentially incurring significant financial risks due to unsuccessful outcomes (García-Villaverde et al., Citation2021; Lumpkin & Dess, Citation2001). Innovation can be classified into radical or incremental innovations, with the former mostly being disruptive innovation and the latter mostly being exploitative innovation (Van Doorn et al., Citation2022a). In the tourism industry, firms rarely pursue disruptive innovation, but tend to make incremental and progressive enhancements in their products and services (Paget et al., Citation2010). However, innovation is still an important antecedent to accommodate tourism firm performance (Kallmuenzer & Peters, Citation2018).

Risk-taking refers to the degree of firms’ willingness to invest in endeavours with high uncertainty that may incur costly sacrifices in case of failure (Lumpkin & Dess, Citation2001). Given the uncertain nature of risk taking, its effect on firm performance varies with some authors showing that risky strategies lead to varied firm performance outcomes but may bring profit in the long run (e.g. McGrath, Citation2001); other authors advise that risky strategies are not recommendable to firms because the relationship between risky strategy and firm performance is curvilinear (e.g. Kreiser & Davis, Citation2010). However, entrepreneurship, proactiveness and innovation are all risky in nature as their outcomes are unpredictable.

2.3. Advisor familiness and entrepreneurial orientation

Scholarly inquiry has attended to the antecedents of higher EO as a precursor of improved firm performance (Covin & Wales, Citation2012), with entrepreneurs’ social networks being a crucial factor in tourism entrepreneurship (Tajeddini et al., Citation2020), encompassing entrepreneurs’ family members. Habbershon and Williams (Citation1999) introduced the concept of familiness to assess the degree of family involvement in business management. Building upon this terminology, we create advisor familiness to measure the extent to which family members are embedded in entrepreneurs’ advice networks. Family members play a vital role in firm founding and growth. They provide initial capital, valuable resources, and a stable labour force, contributing to lower costs and risks (Teixeira et al., Citation2019). Moreover, family involvement is argued to enhance the entrepreneurial nature of firms, supporting their pursuit of risky and entrepreneurial activities (Van Doorn et al., Citation2022b). However, from an attention-based view, more findings tend to indicate that family members’ involvement as advisors may render entrepreneurs less attentive to prioritising EO (Van Doorn et al., Citation2022a).

First, family members and the entrepreneurs share commonalities in values, behaviours and thoughts, such that family members’ advice may serve to validate the entrepreneurs’ thoughts rather than to offer fresh insights that can help entrepreneurs pay attention to more innovative strategies (Van Doorn et al., Citation2022b). Second, family members will be less enterprising and reluctant to be a first mover but would rather advise entrepreneurs to attend to strategies that can preserve attained wealth, and avoid risky strategies, making a firm less proactive (Kallmuenzer & Peters, Citation2018). Third, as most family members may provide funds for the entrepreneurs, in order to preserve family wealth, family members turn more cautious in strategic issues and are also less inclined to take risky strategies, making entrepreneurs more risk averse in fear of failure that may incur financial burden (Singal, Citation2014), and consequently, may also prevent the firms from investing resources in expansion, new product development, and R&D, making firms less innovative (Kallmuenzer & Peters, Citation2018). Henceforth, we argue that advisor familiness negatively influences EO.

H1. Advisor familiness negatively influences EO.

2.4. Gender

In a male-dominated social structure, women encounter challenges in accessing entrepreneurship resources, start-up capital, and financing, resulting in fewer resources compared to male entrepreneurs (Figueroa-Domecq et al., Citation2020). Consequently, male entrepreneurs generally outperform females, with higher profit potential (Boley et al., Citation2017). Furthermore, although female entrepreneurs are more disposed to developing personal networks, these networks often lack financial support (Ahl & Marlow, Citation2021). Additionally, female entrepreneurs have fewer opportunities for angel investment, venture capital funding, and initial public offerings (Jennings & Brush, Citation2013).

The above impediments in women's entrepreneurship led to conservativeness of their strategic attention (Yang et al., Citation2017). For example, women tend to choose low-risk industries like retail and personal services, while men opt for high-risk sectors such as manufacturing and corporate services because in these industries female entrepreneurs face strong male prejudice from all sides (e.g. investors, suppliers, colleagues, and customers) (Figueroa-Domecq et al., Citation2020). Perhaps due to the nuanced distinctions in societal expectations for male and female entrepreneurs, female entrepreneurs often exhibit a more conservative approach to financial goals, demonstrating a reluctance towards substantial capital investments and debt, and are less predisposed to seek funding for business expansion (Figueroa-Domecq et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, women prioritise work-life balance, with flexibility in entrepreneurship to accommodate family and personal goals (Figueroa-Domecq et al., Citation2020), and they often emphasise social impact alongside economic returns (Kimbu & Ngoasong, Citation2016). In addition, women entrepreneurs predominantly rely on friends and family as primary funding sources. Consequently, to safeguard the capital acquired from these cherished relationships, they often manifest a heightened risk aversion and resistance to change (Pettersson & Heldt Cassel, Citation2014).

However, unlike female entrepreneurs who are less prone to taking risks and more attentive to family matters, male entrepreneurs are more driven by financial goals (Moswete & Lacey, Citation2015). In order to realise their financial goals, male entrepreneurs are more opportunity-driven than female entrepreneurs (Figueroa-Domecq et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, male entrepreneurs tend to have more firm resources, and higher total assets (Lee & Marvel, Citation2014) such that male entrepreneurs will be more enterprising and more daring to take risks and make innovations. Henceforth, we argue that gender moderates the relationship between advisor familiness and EO, while male entrepreneurs will be less influenced by the negative effects.

H2. Entrepreneur’s gender moderates the negative relationship between advisor familiness and EO, with male entrepreneurs being less impacted by the negative effects.

2.5. Education level

Education level is negatively related to risk aversion (Fuentelsaz et al., Citation2018). Highly educated entrepreneurs have the knowledge and intellectual ability to calculate the risks with higher precisions, such that entrepreneurs with higher education level will be more attentive to allow their firms to take calculated risks (Hoskisson et al., Citation2017). Moreover, higher education level also renders entrepreneurs to be more attentive to innovation (Fuentelsaz et al., Citation2018). Entrepreneurs with more education possess better cognitive abilities, receptiveness to innovation, and improved knowledge absorption and application (Hoskisson et al., Citation2017). More education also enhances their ability to identify opportunities, leverage resources, and create viable businesses with sound financial performance (Fuentelsaz et al., Citation2018). Intellectual competence obtained through education also enhances predictive abilities, information retrieval, analysis, and decision-making skills that make entrepreneurs cognizant of the value of proactiveness, and calculated risk-taking (Kayser & Blind, Citation2017).

In summary, entrepreneurs with higher education levels may be more attentive to taking calculated risks, initiating innovation, and adopting proactive approaches. Henceforth, we argue that the entrepreneurs’ education level attenuates the negative effects of advisor familiness on EO.

H3. Entrepreneur’s education level attenuates the negative effects of advisor familiness on EO.

2.6. Age

Although older entrepreneurs possess advantages due to their relevant experience, they exhibit a negative correlation with EO (Zhang & Acs, Citation2018). Older entrepreneurs benefit from their experience, social capital, and accumulated wealth, making them more active in entrepreneurship (Lin & Wang, Citation2019). However, younger entrepreneurs outperform older entrepreneurs in terms of EO, measured by innovation, risk-taking, and proactiveness (Van Doorn et al., Citation2017).

Younger people, with less attention given to the burden of family in comparison to their older counterparts, are more attentive to take calculated risks that can help them achieve entrepreneurial success (Priede-Bergamini et al., Citation2019). At their younger ages, individuals tend to be riskier and more inclined to pursue entrepreneurship (Wach et al., Citation2016). For young entrepreneurs, entrepreneurial success is a way to realise their life value, and initial success may make them more confident and passionate towards entrepreneurship (Wach et al., Citation2016). Consequently, younger entrepreneurs are more willing to take riskier strategies in investing in new companies, launching new products and making innovations (Lévesque & Minniti, Citation2011). Contrarily, senior entrepreneurs, having more experience than younger entrepreneurs, tend to be more conservative from the lessons through their managerial experiences, leading to their risk-taking behaviour being less frequent (Priede-Bergamini et al., Citation2019). Given all these considerations, we argue that an entrepreneur’s age may further strengthen the negative relationship between advisor familiness and EO.

H4. Entrepreneur’s age strengthens the negative relationship between advisor familiness and EO.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data collection

In mid 2022, using a purposive sampling technique, we surveyed Chinese entrepreneurs in the tourism and hospitality sector. Surveys initially developed in English and later translated into Chinese by accredited translators were distributed face-to-face in Guangdong, Beijing, Zhejiang, and Shandong to increase generalisability. We collected 447 valid responses, with approximately equal contributions from the four areas.

To address common method bias, pre-testing involved 20 tourism and hospitality entrepreneurs, resulting in minor adjustments to minimise common method bias (Fuller et al., Citation2016). Additionally, survey anonymity was ensured for response accuracy (Fuller et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, Harman's one-factor test was employed to assess whether a single factor could explain all variances of EO (Fuller et al., Citation2016). The observed results demonstrate effective minimisation of common method bias, as the largest variance recorded is 45.217%, significantly below the threshold of 50% (Fuller et al., Citation2016).

3.2. Measures

For the dependent variable, EO is measured on a seven-Likert scale from risk taking, innovativeness, and proactiveness (Hughes & Morgan, Citation2007). For the independent variable, a measure for advisor familiness was created due to the lack of appropriate measures from the existing literature. Using the name generator method (Laumann, Citation1966), respondents will be asked if the advisor (a maximum of seven) is a direct family member (coded 4), an extended family member (coded 3), a distant family member (coded 2) or a nonfamily member (coded 1). The mean value of the answers represents advisor familiness.

For moderators, we measured gender by male and female, education level by categories from primary school to Ph.D. and age by the chronicle age of the entrepreneurs. Based on previous studies that found the possibility of control variables to influence risk taking, innovative and proactive behaviour, we controlled for respondents’ previous primary industry, serial entrepreneurship, marital status, equity share, and firm size (Kallmuenzer & Peters, Citation2018; Zeng et al., Citation2022). We further controlled advisor age and advice frequency (Zeng et al., Citation2022). Primary industry comprises 12 options from the Standard Industrial Classification System (Mun et al., Citation2019), but later was coded into dummy variables with Service (Tourism & Hospitality) and Other services coded 1, and all other industries coded 0. Serial entrepreneurship is measured by the number of companies the respondent had founded plus one. Equity share equals the percentage of ownership the respondent holds in the company. Advice frequency measures the frequency of seeking advice from the reported advisor over the past half a year (Morrison, Citation2002).

4. Analyses

4.1. Descriptive analyses

An analysis of the data () reveals that a significant proportion of respondents, 329 out of 447, had prior engagements in the tourism sector before establishing their own enterprises, representing 73.6% of the sample. In terms of gender distribution, males comprised 39.8% (178 respondents) while females represented 60.2% (269 respondents). When examining educational qualifications, a majority, 64.7% (289 respondents), possessed either an associate or bachelor's degree. This was followed by those with a high school diploma at 20.6% (92 respondents), a middle school diploma at 7.2% (32 respondents), and a master's degree at 6.7% (30 respondents). Cumulatively, 71.6% of the tourism entrepreneurs in the sample had attained higher education. Age-wise, the predominant age bracket for these entrepreneurs was between 25–45 years, with a notable peak at the age of 30, and a subsequent decline on either side.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and correlations.

4.2. Confirmatory factor analyses

Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were conducted on EO, including risk taking, innovativeness, and proactiveness. The first item of risk taking, which stated ‘The term ‘risk taker’ is considered a positive attribute for people in our business,’ exhibited a low loading and was subsequently removed from the analysis. The results of the CFA indicate an acceptable overall model fit (χ2 = 67.465, df = 17, χ2/df = 3.969, p < .001, GFI = 0.966, NFI = 0.959, NNFI = 0.948, IFI = 0.967, CFI = 0.969, TLI = 0.948, and RMSEA = 0.082, AGFI = 0.927, SRMR = 0.043). CFA results for EO show satisfactory factor loadings () and AVE exceeding 0.50, indicating good convergent validity as per Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981). CR values above 0.70 indicate satisfactory internal consistency (Hair et al., Citation2010).

Table 2 . CFA results of EO.

4.3. Regression and hypothesis testing

To evaluate the hypotheses, Hierarchical Multiple Regression was employed instead of Structural Equation Modeling, given that the study embraced a reflective approach (George, Citation2011). This approach perceives subdimensions as outcomes emanating from the overarching EO construct and operationalises EO utilising a composite score, encapsulating risk-taking, proactiveness, and innovativeness (George, Citation2011; Van Doorn et al., Citation2017). We calculated the VIFs to avoid multicollinearity, revealing that the biggest VIF among all variables is around 1.6 for entrepreneurs’ age, well below the threshold of 10 (Neter et al., Citation1990).

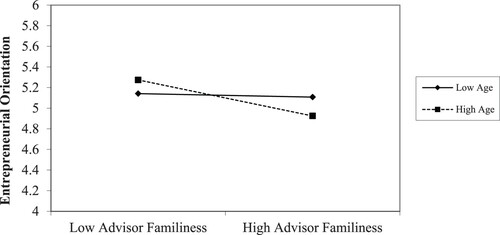

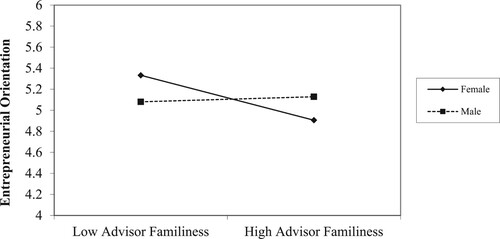

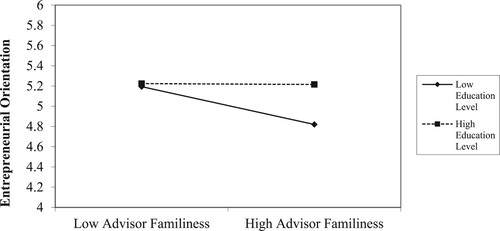

presented the detailed analyses. Model 1 contained the control variables, while model 2 contained the moderators and the independent variables. Model 3 presented the interaction effects. Before testing Model 3, we mean-centred all items to lessen multicollinearity (Aiken et al., Citation1991). Model 2 showed that advisor familiness negatively influenced EO (β = – .11, p < .01), supporting H1. Model 3 showed that gender moderated the relationship between advisor familiness and EO (β = .25, p < .001), supporting H2; male entrepreneurs appeared to be less affected by the negative effects of advisor familiness. Model 3 also showed that an entrepreneur’s age strengthened the negative relationship between advisor familiness and EO (β = – .01, p < .05), supporting H4. Further, the education level appeared to attenuate the relationship between advisor familiness and EO (β = .12, p < .05), supporting H3. Henceforth, all hypotheses are supported.

Table 3 . The regression results.

demonstrated the interaction effect between advisor familiness and gender, which indicated a significant difference between male and female entrepreneurs. For female entrepreneurs, a negative interaction was detected between advisor familiness and EO, signalling that advisor familiness might pose a severer negative effect for female entrepreneurs. However, for male entrepreneurs, advisor familiness did not seem to interact as negatively with EO as female entrepreneurs. A further slope test showed that the relationship for males was insignificant (p > .10) while the relationship for females was significant (p < .01).

Figure 2. Interaction Plot between Advisor Familiness and Gender. I

depicted how the interaction between advisor familiness and education level influenced EO. Entrepreneurs with higher education levels were not affected by advisor familiness (p > 0.10). However, entrepreneurs with lower education levels seemed to witness stronger negative effects of advisor familiness on EO (p < 0.01).

Figure 3. Interaction Plot between Advisor Familiness and Education Level.

showed the interaction between advisor familiness and age on EO. Among older entrepreneurs, a stronger negative effect of advisor familiness on EO was detected (p < 0.01), while the influence of familiness on EO among younger entrepreneurs was insignificant (p > 0.10).

5. Discussion and conclusion

5.1. Summary of findings

Entrepreneurs in the tourism industry interact strongly with family members in their business pursuits (Li et al., Citation2022). Family members are believed to be the most accessible source for entrepreneurs, and entrepreneurs have the tendency to adopt advice from family members due to their emotional connection (Aldrich & Cliff, Citation2003). This is the reason why this study examined the role of family members in entrepreneurs’ advice network. From an attention-based view, the study investigated how advisor familiness influences entrepreneurs’ attention to pursuing EO as well as the moderation effects of the entrepreneur’s personal characteristics (i.e. gender, education level and age). This study not only finds that advisor familiness negatively influences entrepreneurs’ attention to prioritising risk taking, innovation and proactiveness, but also detects significant moderating effects from entrepreneurs’ gender, age and education. For example, male entrepreneurs appear to be less influenced by advisor familiness. Moreover, better-educated entrepreneurs are less affected by advisor familiness. However, entrepreneurs’ age tends to strengthen the negative effects of advisor familiness on EO. The research answers the call for study in tourism entrepreneurs’ ego network (Yachin, Citation2021).

5.2. Theoretical contributions

First, the research addresses the inconsistencies regarding the role of family members in entrepreneurship through the angle of advice network. Since family members as a resource for entrepreneurs are important for entrepreneurial success (Li et al., Citation2022), and the perceived support from family members will increase an entrepreneur’s self-efficacy and tendency to take risks (Hallak et al., Citation2014), some may intuitively argue that advisor familiness positively influences EO. However, our findings reveal that advisor familiness lowers EO, echoing some prior studies proposing that family involvement may lead to less innovation and risk-taking behaviours (Naldi et al., Citation2007; Peters & Kallmuenzer, Citation2018). Our research extends the findings to an advice seeking context and contributes to the attention-based view by identifying advisor familiness negatively influences entrepreneurs’ attention to prioritising EO.

Second, the study offers theoretical contributions to the attention-based view through finding that entrepreneurs’ individual characteristics, including education, age and gender, further interact with advisor familiness to influence entrepreneurs’ attention to EO. Specifically, education is an antecedent to increasing an entrepreneur’s human capital (Hoskisson et al., Citation2017). Given that highly educated entrepreneurs have the capacity to absorb information quickly, they tend to season the advice from family members better to cope with the issues that arise in the firm (Fuentelsaz et al., Citation2018). This study discovered that an entrepreneur’s education level attenuates the negative effects of advisor familiness on EO, a finding that is in line with previous research that corroborates individuals’ education level is negatively correlated with risk aversion, inertia to innovation and lack of foresight (Fuentelsaz et al., Citation2018; Hoskisson et al., Citation2017; Kayser & Blind, Citation2017). Senior entrepreneurs, though possessing more resources experience and experience (Lin & Wang, Citation2019), are more negatively influenced by advisor familiness.

This study also contributes to the gender entrepreneurship literature by detecting a strong gender influence on the relationship between advisor familiness and EO. More specifically, male entrepreneurs are less swayed by advice from family members when pursuing risk-taking, innovative and proactive behaviours, which provides further explanations on why male entrepreneurs tend to have a higher level of risk-taking behaviour as compared to their female counterparts (Figueroa-Domecq et al., Citation2020; Jennings & Brush, Citation2013; Lee & Marvel, Citation2014).

Finally, senior entrepreneurs, though possessing more experiences to have more accurate judgment and resources to boost their confidence (Lin & Wang, Citation2019), are more negatively influenced by advisor familiness (i.e. be more conservative or risk-averse). This finding is in line with previous findings (e.g. Priede-Bergamini et al., Citation2019) that senior entrepreneurs’ experience makes them more calculated towards risks and returns of adopting proactive, innovative and risky strategies. This finding also suggests that senior entrepreneurs are more burdened with family so that they are more risk aversed (Priede-Bergamini et al., Citation2019). In other words, the spill-over effects of entrepreneurial failure will be more damaging to the family (Priede-Bergamini et al., Citation2019). Our finding regarding the age effect consolidates previous findings to an advice seeking context.

5.3. Practical contributions

The findings of the current study offer several important practical implications for tourism entrepreneurs. As the results imply, advisor familiness negatively influences the EO of tourism businesses. Since in the tourism industry family members have a high involvement (Li et al., Citation2022), tourism entrepreneurs are suggested to keep or retain family members as a source of advice but at the same time should understand that the influences they are receiving may contradict what they wish to pursue. Under such circumstances, tourism entrepreneurs should resort to non-family members (e.g. close friends, acquaintances, and professional contacts) to avoid redundant and conservative information that may make them more conservative, risk-averse and less enterprising (Li & Liu, Citation2018). While the findings are intuitive regarding gender and education level, the results suggest that for tourism entrepreneurs should strategically utilise their resources in an environment where family members are highly involved in order to achieve better entrepreneurial performance. This is particularly important when an entrepreneur’s age exerts an unexpected strengthening effect on the relationship between advisor familiness and EO.

The findings also provide practical implications for tourism policymakers. First, based on the results of the study, entrepreneurs higher in education level will be less affected by advisor familiness. Henceforth, policymakers should provide more accessible education opportunities for entrepreneurs, especially to understand the value of taking risks, innovation and proactiveness. Second, female entrepreneurs in general face more obstacles during their entrepreneurship trajectory and henceforth may be more negatively affected by advisor familiness. Policymakers should provide more support for female entrepreneurs, such as favourable financing policies, subsidies for women entrepreneurs who are burdened with family affairs, and training programs for women entrepreneurs to understand the importance of EO in achieving better entrepreneurial performance. Third, sessional training programs should be initiated for entrepreneurs to understand the importance of EO, so that senior entrepreneurs, women entrepreneurs and lower-educated entrepreneurs can strive to take risks, innovate and pre-empt.

5.4. Limitations, future research and conclusion

Notwithstanding the valuable findings from the study, several limitations are discussed in the following, which also open valuable avenues for future research:

First, sampling may limit generalisability; data collected from four Chinese regions along the coast may not apply to all of China. Cultural differences between China and the West warrant caution when applying findings. Cross-cultural studies are recommended for future research. Second, data collected during China's COVID-19 crisis in mid 2022 may not reflect normal conditions. Performance in the tourism and hospitality industries was likely worse due to travel restrictions. Future studies should extend the current study by comparing the pandemic and post-pandemic data in tourism and hospitality industries. In other words, longitudinal studies are recommended to examine advisor familiness over a longer period and account for pandemic effects. Third, advisor familiness measurement is limited to a single item, lacking a multidimensional perspective. Future research should develop a multi-item measure and explore the effects of individual traits within the family. Third, consideration should be given to family members who are entrepreneurs, as they may positively influence entrepreneurial orientation. Finally, other personal characteristics like income and marital/family status should be examined alongside gender, age, and education levels.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data can be supplied upon reasonable request.

References

- Ahl, H., & Marlow, S. (2021). Exploring the false promise of entrepreneurship through a postfeminist critique of the enterprise policy discourse in Sweden and the UK. Human Relations, 74(1), 41–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726719848480

- Aiken, L. S., West, S. G., & Reno, R. R. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage.

- Aldrich, H. E., & Cliff, J. E. (2003). The pervasive effects of family on entrepreneurship: Toward a family embeddedness perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(5), 573–596. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00011-9

- Boley, B. B., Ayscue, E., Maruyama, N., & Woosnam, K. M. (2017). Gender and empowerment: Assessing discrepancies using the resident empowerment through tourism scale. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(1), 113–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1177065

- Covin, J. G., & Slevin, D. P. (1989). Strategic management of small firms in hostile and benign environments. Strategic Management Journal, 10(1), 75–87. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250100107

- Covin, J. G., & Wales, W. J. (2012). The measurement of entrepreneurial orientation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(4), 677–702. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00432.x

- Cross, R., Borgatti, S. P., & Parker, A. (2001). Beyond answers: Dimensions of the advice network. Social Networks, 23(3), 215–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-8733(01)00041-7

- Fadda, N. (2018). The effects of entrepreneurial orientation dimensions on performance in the tourism sector. New England Journal of Entrepreneurship, 21(1), 22–44. https://doi.org/10.1108/NEJE-03-2018-0004

- Fadda, N., & Sørensen, J. F. L. (2017). The importance of destination attractiveness and entrepreneurial orientation in explaining firm performance in the Sardinian accommodation sector. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(6), 1684–1702. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-10-2015-0546

- Figueroa-Domecq, C., De Jong, A., & Williams, A. M. (2020). Gender, tourism & entrepreneurship: A critical review. Annals of Tourism Research, 84, 102980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102980

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Sage Publications Sage CA. Los Angeles, CA.

- Fuentelsaz, L., Maicas, J. P., & Montero, J. (2018). Entrepreneurs and innovation: The contingent role of institutional factors. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 36(6), 686–711. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242618766235

- Fuller, C. M., Simmering, M. J., Atinc, G., Atinc, Y., & Babin, B. J. (2016). Common methods variance detection in business research. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 3192–3198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.12.008

- García-Villaverde, P. M., Ruiz-Ortega, M. J., Hurtado-Palomino, A., De La Gala-Velásquez, B., & Zirena-Bejarano, P. P. (2021). Social capital and innovativeness in firms in cultural tourism destinations: Divergent contingent factors. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 19, 100529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100529

- George, B. A. (2011). Entrepreneurial orientation: A theoretical and empirical examination of the consequences of differing construct representations. Journal of Management Studies, 48(6), 1291–1313. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.01004.x

- Habbershon, T. G., & Williams, M. L. (1999). A resource-based framework for assessing the strategic advantages of family firms. Family Business Review, 12(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.1999.00001.x

- Hair, J. F., Black, W., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective. Pearson.

- Hallak, R., Assaker, G., & O’Connor, P. (2014). Are family and nonfamily tourism businesses different? An examination of the entrepreneurial self-efficacy–entrepreneurial performance relationship. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 38(3), 388–413. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348012461545

- Heyden, M. L., Van Doorn, S., Reimer, M., Van Den Bosch, F. A., & Volberda, H. W. (2013). Perceived environmental dynamism, relative competitive performance, and top management team heterogeneity: Examining correlates of upper echelons’ advice-seeking. Organization Studies, 34(9), 1327–1356. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840612470229

- Hoskisson, R. E., Chirico, F., Zyung, J., & Gambeta, E. (2017). Managerial risk taking: A multitheoretical review and future research agenda. Journal of Management, 43(1), 137–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316671583

- Hughes, M., & Morgan, R. E. (2007). Deconstructing the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and business performance at the embryonic stage of firm growth. Industrial Marketing Management, 36(5), 651–661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2006.04.003

- Jennings, J. E., & Brush, C. G. (2013). Research on women entrepreneurs: challenges to (and from) the broader entrepreneurship literature? Academy of Management Annals, 7(1), 663–715. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2013.782190

- Kallmuenzer, A., & Peters, M. (2018). Entrepreneurial behaviour, firm size and financial performance: the case of rural tourism family firms. Tourism Recreation Research, 43(1), 2–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2017.1357782

- Kayser, V., & Blind, K. (2017). Extending the knowledge base of foresight: The contribution of text mining. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 116, 208–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2016.10.017

- Kimbu, A. N., & Ngoasong, M. Z. (2016). Women as vectors of social entrepreneurship. Annals of Tourism Research, 60, 63–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.06.002

- Kreiser, P. M., & Davis, J. (2010). Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance: The unique impact of innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking. Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship, 23(1), 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/08276331.2010.10593472

- Laumann, E. O. (1966). Prestige and association in an urban community: An analysis of an urban stratification system. Bobbs-Merrill.

- Lee, I. H., & Marvel, M. R. (2014). Revisiting the entrepreneur gender–performance relationship: a firm perspective. Small Business Economics, 42(4), 769–786. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-013-9497-5

- Lévesque, M., & Minniti, M. (2011). Age matters: How demographics influence aggregate entrepreneurship. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 5(3), 269–284. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.117

- Li, Q., Zhang, H., Wu, M.-Y., Wall, G., & Ying, T. (2022). Family matters: Dual network embeddedness, resource acquisition, and entrepreneurial success of small tourism firms in rural China. Journal of Travel Research, 61(8), 1757–1773. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472875211047275

- Li, Y. -Q., & Liu, C. -H. (2018). The role of network position, tie strength and knowledge diversity in tourism and hospitality scholars' creativity. Tourism Management Perspectives, 27, 136–151.

- Lin, S., & Wang, S. (2019). How does the age of serial entrepreneurs influence their re-venture speed after a business failure? Small Business Economics, 52(3), 651–666. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9977-0

- Liu, C.-H. S., & Lee, T. (2019). The multilevel effects of transformational leadership on entrepreneurial orientation and service innovation. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 82, 278–286.

- Lumpkin, G. T., & Dess, G. G. (2001). Linking two dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation to firm performance: The moderating role of environment and industry life cycle. Journal of Business Venturing, 16(5), 429–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(00)00048-3

- Ma, S., Kor, Y. Y., & Seidl, D. (2020). CEO advice seeking: An integrative framework and future research agenda. Journal of Management, 46(6), 771–805. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206319885430

- McGrath, R. G. (2001). Exploratory learning, innovative capacity, and managerial oversight. Academy of Management Journal, 44(1), 118–131. https://doi.org/10.2307/3069340

- Miller, D. (1983). The correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms. Management Science, 29(7), 770–791. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.29.7.770

- Morrison, E. W. (2002). Newcomers’ relationships: The role of social network ties during socialization. Academy of Management Journal, 45(6), 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.2307/3069430

- Moswete, N., & Lacey, G. (2015). ‘Women cannot lead’: Empowering women through cultural tourism in Botswana. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(4), 600–617. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2014.986488

- Mun, C., Kim, Y., Yoo, D., Yoon, S., Hyun, H., Raghavan, N., & Park, H. (2019). Discovering business diversification opportunities using patent information and open innovation cases. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 139, 144–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.11.006

- Naldi, L., Nordqvist, M., Sjöberg, K., & Wiklund, J. (2007). Entrepreneurial orientation, risk taking, and performance in family firms. Family Business Review, 20(1), 33–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2007.00082.x

- Neter, J., Kutner, M. H., Nachtsheim, C. J., & Wasserman, W. (1990). Student Solutions Manual for Use with Applied Linear Regression Models, & Applied Linear Statistical Model Fourth Edition. Irwin/McGraw Hill.

- Ocasio, W. (1997). Towards an attention-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 18(S1), 187–206. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199707)18:1+<187::AID-SMJ936>3.0.CO;2-K

- Paget, E., Dimanche, F., & Mounet, J. P. (2010). A tourism innovation case: An actor-network approach. Annals of Tourism Research, 37(3), 828–847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2010.02.004

- Peters, M., & Kallmuenzer, A. (2018). Entrepreneurial orientation in family firms: The case of the hospitality industry. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(1), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2015.1053849

- Pettersson, K., & Heldt Cassel, S. (2014). Women tourism entrepreneurs: doing gender on farms in Sweden. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 29(8), 487–504. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-02-2014-0016

- Priede-Bergamini, T., Lopez-Cozar-Navarro, C., Benito-Hernández, S., Rodríguez-Duarte, A., & Platero, M. (2019). The dual effect of the age of the entrepreneur on the innovation performance of the micro-enterprises. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing, 11(1), 81–102. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEV.2019.096659

- Rauch, A., Wiklund, J., Lumpkin, G. T., & Frese, M. (2009). Entrepreneurial orientation and business performance: An assessment of past research and suggestions for the future. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 761–787. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00308.x

- Singal, M. (2014). Corporate social responsibility in the hospitality and tourism industry: do family control and financial condition matter? International Journal of Hospitality Management, 36, 81–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2013.08.002

- Tajeddini, K., Martin, E., & Ali, A. (2020). Enhancing hospitality business performance: The role of entrepreneurial orientation and networking ties in a dynamic environment. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 90, 102605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102605

- Tang, T.-W., Zhang, P., Lu, Y., Wang, T.-C., & Tsai, C.-L. (2020). The effect of tourism core competence on entrepreneurial orientation and service innovation performance in tourism small and medium enterprises. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 25(2), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2019.1674346

- Teixeira, R. M., Andreassi, T., Köseoglu, M. A., & Okumus, F. (2019). How do hospitality entrepreneurs use their social networks to access resources? Evidence from the lifecycle of small hospitality enterprises. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 79, 158–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.01.006

- Van Doorn, S., Heyden, M. L., Reimer, M., Buyl, T., & Volberda, H. W. (2022a). Internal and external interfaces of the executive suite: Advancing research on the porous bounds of strategic leadership. Long Range Planning, 55(3), 102214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2022.102214

- Van Doorn, S., Heyden, M. L., & Volberda, H. W. (2017). Enhancing entrepreneurial orientation in dynamic environments: The interplay between top management team advice-seeking and absorptive capacity. Long Range Planning, 50(2), 134–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2016.06.003

- Van Doorn, S., Jansen, J. J., Van den Bosch, F. A., & Volberda, H. W. (2013). Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance: Drawing attention to the senior team. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 30(5), 821–836. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12032

- Van Doorn, S., Tretbar, T., Reimer, M., & Heyden, M. (2022b). Ambidexterity in family firms: The interplay between family influences within and beyond the executive suite. Long Range Planning, 55(2), 101998. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2020.101998

- Wach, D., Stephan, U., & Gorgievski, M. (2016). More than money: Developing an integrative multi-factorial measure of entrepreneurial success. International Small Business Journal, 34(8), 1098–1121. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242615608469

- Wales, W. J., Covin, J. G., & Monsen, E. (2020). Entrepreneurial orientation: The necessity of a multilevel conceptualization. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 14(4), 639–660. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1344

- Wiklund, J., & Shepherd, D. (2005). Entrepreneurial orientation and small business performance: a configurational approach. Journal of Business Venturing, 20(1), 71–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2004.01.001

- Yachin, J. M. (2021). Alters & functions: exploring the ego-networks of tourism micro-firms. Tourism Recreation Research, 46(3), 319–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2020.1808933

- Yang, E. C. L., Khoo-Lattimore, C., & Arcodia, C. (2017). A systematic literature review of risk and gender research in tourism. Tourism Management, 58, 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.10.011

- Zeng, Z., van Doorn, S., & Liu, F. (2022). Advice network of tourism entrepreneurs: co-owner advisor, advice frequency, advisor seniority and entrepreneur advisor. 2022 ANZMAC Conference, Perth, Australia.

- Zhang, T., & Acs, Z. (2018). Age and entrepreneurship: nuances from entrepreneur types and generation effects. Small Business Economics, 51(4), 773–809. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0079-4