Abstract

This paper examines the obstacles to studying and using displaced radio archives, taking as a case study a collection of historic recordings from Nazi Germany that is held at the Czech Radio archive in Prague. This so-called ‘Loot Collection’ (Kořistní fond) occupies an awkward position between established categories and is confronted simultaneously by the challenges common to historic sound archives, and those specific to collections which have been displaced from their point of origin. The paper shares some early analysis of the history and content of this collection, and argues for a transnational approach to ‘activate’ other overlooked archival collections whose history and relevance spreads across contemporary national borders.

Introduction

My motivation was to give an impetus: take a look, what if there is something really interesting there? What if there is something there which has been thought lost for years? It would be a great shame if it sat on the shelf for years to come.Footnote1

These are the words of Czech journalist Pavel Polák on his prize-winning 2017 radio programme about an overlooked archival radio collection.Footnote2 Held in the deepest basement storage room of Czech Radio in Prague, the so-called Kořistní fond (KF) or ‘Loot Collection’ is a vast collection of sound recordings preserving the music, speeches and culture of Nazi German radio.Footnote3 Despite the ongoing fascination with this period of European history in both popular culture and academic research, the vast majority of these recordings have not been heard in over eighty years and the collection remains an untapped resource for both researchers and programme makers. While attempting to research this collection—its content and its archival journey—I encountered many obstacles illustrative of the difficulty of ‘activating’ awkward archives. In this case, the awkwardness is two-fold: as a displaced radio archive, the KF is subject not only to the general challenges faced by all historic audio-visual materials, but also those unique to collections that sit uncomfortably within the institutions which hold them. In order for collections such as this to be fully understood and made available to those who can put them to use, a transnational approach is needed in both research and preservation, one that is supported by international collaboration between archival organisations.

I conducted my research into this collection as part of my work for the University of Amsterdam’s TRACE project (Tracking Radio Archival Collections in Europe, 1930–1960).Footnote4 Within this project, we embrace a broad definition of radio archives that captures both audio materials and the paper collections associated with their creation and management, as produced by any institution or organisation tasked with the preservation of the history of broadcasting.Footnote5 In some cases, it is the archive of a national broadcaster that has taken on much of this responsibility (as is the case in the Czech Republic), elsewhere (as with the German Broadcasting Archive) specific archival institutions are devoted to the preservation of radio history from multiple sources.Footnote6 The TRACE project is premised on the understanding that the often complex journeys taken by radio archival collections in our region and period of study can inform wider studies of broadcasting history, archival heritage, and the shifting geopolitical environment. As such, we seek to spotlight individual collections not only to promote awareness that can encourage further research of the collections themselves, but also to draw out from these case studies the threads that can connect to these wider questions and to the work of scholars in fields outside radio and sound studies. When referring to an archive as ‘displaced’ I am acknowledging, as Lowry has, that archives ‘tell stories through their forms, structures and relations, as well as their content’ and that understanding the journey of an archive moved from its point of creation can therefore further our understanding of its holdings.Footnote7 However, Lowry’s focus on cases where ownership of records is disputed is less relevant in this case.Footnote8 Unlike in some of the case studies presented elsewhere relating to former colonial archives, the power dynamics in this case—in which an occupying regime left behind their own collections which may not have been directly produced or used in the country which now holds them—are rather different, and there has been no push from the German side for restitution of the original materials. It is precisely this ‘awkwardness’ and failure to fit neatly into existing categories that make the KF an interesting case, raising questions about how Nazi-era material can be used in a former Nazi-occupied state, how this collection challenges regular archival practices at Czech Radio, and how perceptions of its origin relate to its prioritisation for preservation and re-use.Footnote9

Dagmar Brunow has argued that audio-visual (AV) archives are active agents in the creation of transnational cultural memory and it could be said that those embedded within broadcasters, whose selection and preservation work can directly affect what archival material is made available for re-use in programming, are more active agents than some.Footnote10 Archives are recognised as actors which have shaped national narratives across Europe, but it is increasingly widely acknowledged that much of media history is ‘entangled’, crossing over institutional and national boundaries in various ways.Footnote11 Some have argued that a transnational approach to the archive can prevent the perpetuation of certain ‘blind spots’ where issues, topics and objects fall outside a national framework. In calling for a transnational approach to ‘activate’ this archive, I am following the lead of film history scholars who have suggested ways in which the potential of often overlooked AV collections could be realised through collaboration between archival institutions and other groups, and by reflecting upon archival spaces as having relevance to wider communities.Footnote12

The KF has been in the possession of Czech Radio (formerly Czechoslovak Radio) since at least the 1950s, but it has hardly ever been used. For decades it was physically isolated from the rest of the collection and the recordings are still not included in Czech Radio’s main catalogue. Although some recent efforts have been made to inventory much of its content, this work is incomplete and this separation impedes access to potential users. After decades stored out of sight, in the post-communist period the collection has received slightly more attention; in the 1990s, the German Broadcasting Archive (Deutsches Rundfunkarchiv, DRA) was made aware of its existence and acquired copies of many of the spoken-word recordings (including Hörspiele or radio plays) which had been missing from its own collections.Footnote13 Polák’s radio report on the collection some twenty years later was lauded, but even this piece contains no actual recordings from the collection, and his hopes that increased attention would prompt its digitisation and study have not yet been realised. As a transnational audio-visual collection, the KF faces many of the same challenges which impede the re-use of sound archives in general, and transnational collections in particular. In what follows, I will identify these challenges and then outline the specifics of this case study, highlighting the factors that need to be taken into account in order to make sense of such a collection.

The KF occupies an awkward liminal space between categories: it is a German collection displaced from Germany; it is a Czech collection but the content is not Czech; it is a sound collection, but little of it can be directly played. These contradictions have led to the collection’s simultaneous and contrasting assessment as both very valuable and totally worthless, a ‘treasure trove’ and ‘useless deadstock’, war loot and unwanted leftovers.Footnote14 With this case study I hope to put the KF in dialogue with wider questions of European media archiving. Firstly, I will examine some of the technical issues of sound archiving raised by a sound collection that cannot be heard, highlighting the difficulties of historical sound carriers and their accompanying documentation. I will then discuss some of the challenges facing transnational collections that do not sit easily within the established national frameworks that dominate both archiving and broadcasting, before moving into the specifics of the creation and relocation of the KF itself. In the final section, I will highlight some of the challenges and opportunities offered by the KF in its current condition, and briefly present an overview of its content. To conclude, I will suggest some of the actions that would need to be taken in order to truly ‘activate’ this collection, and make it usefully accessible. Before so doing, I would like to make clear that nothing in this article is intended as a critique of current or former archival professionals at any institution. All were working under different constraints—almost always including that of limited time and limited funding—and those efforts made so far to preserve and document the KF should be appreciated. My admiration on this point notwithstanding, I hope that this case study offers a new approach to researching historic sound archives, and making use of some of the collections which sit overlooked on archive shelves.

A Sound Collection You Cannot Hear: Challenges of Historic Radio Collections

Historic sound collections are demanding and require extensive processing if they are to be fully ‘activated’ for use by their holding institutions. The term ‘activation’ has been interpreted in many different ways in relation to archives, sometimes pertaining to an approach to archiving (e.g. incorporating previously overlooked sources into a dynamic network of objects and ‘knowers’) and sometimes applied to the end goal of archival research (e.g. specifically mobilising archival sources to support activism).Footnote15 While some have characterised the issue of access as a precursor to activation, in the case of the KF, I consider the two to be intertwined; to be truly ‘active’, an archival collection needs to be fully accessible to potential users, i.e. they must know of its existence, be able to identify potentially useful objects within it, and exploit these objects for a given purpose (e.g. research, programme making).Footnote16 The process of activation is therefore multi-stage as, in this example, it requires promotion of the collection among possible users, proper cataloguing, and finally possible digitisation or other processing of the objects to make them usable. Obstacles to activation can relate to the sound carriers themselves (e.g. the obsolescence of historic recording technologies), to their accompanying documentation (or lack thereof), as well as to their actual content, and the KF offers examples of all three.

In contrast to archival institutions whose collections are largely comprised of paper, archives with AV collections face further challenges relating to the physical format of their holdings and their inevitable obsolescence. With each new innovation in AV technology, the preservation of older formats becomes more challenging. In order to maintain access to historic holdings, AV preservation institutions are engaged in a process of duplication (i.e. making new copies of existing recordings on new carriers/technology) and maintenance of obsolete carriers and playback equipment which is never-ending: ‘nothing has ever been preserved—it is only being preserved’.Footnote17 For institutions with large historical collections, carriers can vary hugely, from early wax cylinders to grooved discs of varied sizes and formats, steel tape, magnetic tape, digital tape, film tape, CDs, and many generations of digital recordings. The perennial challenge of obsolete formats—physical and digital—becoming unplayable is faced by all such institutions and responses to it are traditionally limited by time and resources.Footnote18

In the case of the KF, the carriers impose a second obstacle to accessibility as almost half of the collection is preserved solely on metal matrix discs, with the rest comprising pressed discs and a small number of tapes. A matrix disc (also known as just a matrix, or a disc stamper) is the metal ‘negative’ plate from which gramophone discs are pressed, and preserving them offered a more robust long-term storage solution from which further pressings could be made if necessary.Footnote19 However, they are not directly playable without specialist equipment; in order to play or transcribe directly from a matrix disc—without making a new pressing—a specialist stylus is required and these have become increasingly difficult to acquire since discs have lost their dominance as a format. This has forced archivists to consider how to manage sound collections that they cannot actually play. While other institutions have worked around this issue by using accompanying documentation and related material to inventory their matrix collections, we here encounter a further obstacle to use of the KF as many of the recordings lack such contextualising information; while they are labelled with a matrix number, the latest surviving pre-1945 German radio catalogue only documents recordings up to early 1939, so there is no entry to which this number can be matched for wartime recordings.Footnote20

Even the material which could be played on existing equipment (i.e. that stored on disc and tape) is not digitised, or accessibly catalogued. Although the preservation of its archive is part of Czech Radio’s mission and it is working to digitise more of its historical material, there is a significant backlog of recordings to process and it has to prioritise those which are most in-demand among programme makers, as well as those carriers which are most at risk of degradation.Footnote21 The KF—largely unknown and therefore unrequested, and stored for the most part on carriers at minimal risk of damage—naturally features relatively low in the list of priorities and could take decades to be processed.Footnote22 The collection is therefore caught in something of a vicious circle: its holdings are not findable so programme makers do not request them, but because they are not requested the archive does not dedicate time to making them findable. Some time and resources must therefore be devoted to it, in order to establish whether it is worth devoting time and resources to. The question of the KF’s content and therefore its perceived relevance to Czech Radio’s audience is key here, and the fact that the KF is largely German rather than Czech in nature doubtless plays a part in its assessment from a Czech broadcasting point of view. The question of the collection’s national origins is therefore a factor in its neglect, and this relates to a wider issue of the preservation of transnational archives.

A Transnational Collection in a National Framework

As a collection of originally German objects held in a Czech institution and relating to a pivotal and dark period in the shared history of both states, this case study offers a further challenge to the national paradigm that still dominates in archiving. There is growing support for the benefits a transnational approach can bring to studies of radio and large-scale international projects such as Europeana Sound are testament to efforts in this area.Footnote23 However, wider academic discussions of shared archival heritage, or archives which are integral to the histories of more than one state, are generally dominated by studies of former global empires, focusing on disputes over which state is the rightful successor to, for example, the archive of a former colonial administration.Footnote24 The KF, by contrast, is an example of a transnational collection relating to two neighbouring European states; as Näripea et al have discussed in relation to film archives, the period in which technology has enabled the recording and preservation of AV materials overlaps with a turbulent period in which both borders and prevailing political ideologies in Central and Eastern Europe have shifted repeatedly, creating heritage collections which move in and out of political favour and often straddle the histories of more than one current state.Footnote25

However, the fields of both broadcasting and archiving in much of Europe continue to be dominated by large national institutions, generally state-funded and tasked with a correspondingly ‘national’ mission in terms of the heritage they preserve (even if they participate in international projects such as Europeana). The role of national archives in establishing and perpetuating ‘national narratives’ throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries has been discussed by Berger and others, but increasingly scholars are highlighting cases which defy this national mould, and sit uncomfortably in archives with a single national focus.Footnote26 In their article on Ottoman film heritage, Özgen and Rongen-Kaynakçi warn that a failure to acknowledge the shared history of early cinema across the former Ottoman empire risks leaving items now held in various ‘national’ institutions of successor states ‘forgotten, misidentified, or abandoned’. They argue that a purely national approach to film history creates ‘gaps, absences, and silences’ around objects whose context does not map onto present national borders, and that a transnational approach to the archive offers opportunities to ‘activate (i.e. excavate, spotlight)’ such objects, allowing scholars to challenge accepted narratives and deepen our understanding.Footnote27 Given the nature of these objects, ‘activation’ may well demand the co-operation of multiple institutions, possibly across multiple countries, to reflect upon how these objects unite their respective areas of interest. In order to better understand how the KF relates to both German and Czech history—and how it has already been the subject of some international collaboration between the two countries—it is worth briefly reviewing what is known (and what can be surmised) of its history.

Loot or Leftovers? A History of the Collection

Although the name ‘Loot Collection’ implies that the KF was plundered from German hands, and it is sometimes described as having been taken as reparations, the evidence suggests this is a misnomer and the collection could more accurately be described as leftover. Based on surviving archival sources and the content of the discs themselves, it seems that the KF is made up of one or more archival collections from Germany that were relocated to the Protectorate for safekeeping during the later years of the war. In comparison to German cities which had been subjected to bombardment from early in the conflict and faced increasing numbers of attacks from late 1943 onwards, the Protectorate remained out of Allied bombing range until very late in the war and never suffered a major raid. Although it has not been possible as yet to find surviving documentation relating to the relocation of the matrices, it is known that, from the summer of 1942 onwards, there was a mass programme of relocating German archival holdings to safer locations, including within the Protectorate.Footnote28 Several stately homes in the Protectorate, generally far from urban centres and providing the necessary dry, safe conditions, were identified as suitable locations and commandeered.Footnote29 Ferdinand Thürmer, who oversaw broadcasting in the Protectorate, wrote specifically about broadcasting offices and archives being moved to Prague from 1944 onwards as radio infrastructure within Germany was damaged and threatened.Footnote30 Other archival references suggest that this included collections from the Reichssender Berlin, also relocated to Prague in 1944—the year in which the latest KF recording was made—but no specific mention of a collection that could have become the KF has yet been found, and may not have been preserved.Footnote31

The use of stately homes for archival storage continued in post-war Czechoslovakia and Czechoslovak Radio’s archives were held in the chateau at Přerov nad Labem from the late 1950s until the year 2000. While the majority of the collection was housed in the chateau itself, the KF received rather different treatment, according to later head of the Czech Radio archives Eva Ješutová:

The radio archive at that time was located in Přerov nad Labem, where it took up the whole of a beautiful Renaissance chateau. But this collection [the KF] was separated into its own depot […] almost as a punishment. It was originally a pub but had already been disused for fifty years. There was a brick floor, wooden shelves, lots of dust and dirt. There on the shelves lay many gramophone records and metal matrix discs. Lots of them were unfortunately broken. The floor was covered in shards of broken discs. Full of spiders, cobwebs. Maybe also mice.

However, memory of the collection seems to have been lost in Germany until the DRA learned of its existence in 1988. In contrast to decades of Czech indifference, there was immediate interest on the German side, in keeping with the organisation’s stated aim ‘to archive and document historically significant audiovisual media’ from Germany’s past.Footnote35 Early investigations showed that the DRA had the necessary equipment to transcribe from the matrices and could produce new recordings of broadcast quality. Although it took several years for the details of an exchange arrangement to be agreed, the DRA found much of interest in the collection and the first fruit of the collaboration was the re-broadcast of Günter Eich’s radio play Rebellion in der Goldstadt, originally broadcast in 1940 as part of an anti-British propaganda campaign. As no recordings were thought to have survived and the original scripts were not preserved, this play was believed to be lost and its rediscovery was celebrated as part of the 70th anniversary celebrations of radio in Germany in 1993.Footnote36 This was followed by several years of collaboration, during which the DRA purchased the necessary equipment for Czech Radio to transcribe from the matrices in Přerov (thereby limiting the need to transport the historic carriers) and, over the course of the 1990s, requested copies of specific recordings which Czech Radio duly supplied on R-DAT (digital tape). The DRA’s requests focused initially on Hörspiele like Eich’s, followed by other spoken-word recordings (speeches and news recordings), but largely excluded the music recordings which comprised the majority of the collection. After receiving some 240 R-DAT tapes, the DRA made its final requests in 1998, concluding what the institution viewed as a successful cooperation that enabled the rediscovery of some important historic recordings which had not been preserved within Germany, thereby filling in some important ‘gaps’ in their holdings.Footnote37

On the Czech side, however, this collaboration did not notably raise the prestige of the collection. Although much of the spoken-word material is of less obvious use to a mainly Czech-language broadcaster, Czech Radio does broadcast in German, and the music selection is truly international. When asked about the collection in 2022, however, staff described it as ‘useless deadstock’, taking up several hundred metres of archive space and never used for anything.Footnote38 As mentioned earlier, a spreadsheet of the collection was compiled in the mid 2010s which does yield further information on its holdings and, in order to try and open up the content of the collection to researchers, I will summarise here what I have ascertained about its content, and the challenges facing those wishing to work with it.

Working with the KF: Opportunities and Challenges

The KF contains just under 20,000 matrices and 10,000 discs, as well as 240 R-DAT digital tapes and some older tape recordings, largely taken from discs. As is often the case with radio archives, the KF is a hybrid collection not only of sound carriers but also of documentation; Czech Radio also holds some physical copies of printed pre-war RRG catalogues which cover recordings made from 1929 until early 1939, some of which are annotated by hand. It is believed that there was previously additional documentation held relating to the post-1939 recordings, but this is no longer found within the archive, believed lost. The main reference source for the KF itself is a spreadsheet which condenses the collection into 4,055 entries (where e.g. a speech spans multiple matrix numbers/discs, these are often summarised in a single entry, as are duplicates of the same discs). Data fields within the spreadsheet capture information on content, matrix number, disc number, tape number or corresponding R-DAT, the original broadcasting station, date of broadcast, length, and some notes on e.g. damage to specific discs within each entry. This spreadsheet was shared with the TRACE project and has been subjected to some data cleaning and analysis.Footnote39

In terms of content, my analysis suggests the KF as a whole is approximately 75% music, comprising a wide array of genres (in rough order of prevalence, these include military music and marches, folk/world music, classical, light or entertainment music, songs, and opera/operettas). It is a highly diverse collection: more than 900 individual composers are named within it, of which more than 700 have only one or two recordings included in the collection. The few composers who feature more frequently are largely prominent German and Austrian figures of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (e.g. Johann Strauss II, Wagner, Bach, Mozart, Beethoven) and only two figures who were still living at the time the KF was made: Nazi songwriters Herms Niel (1888–1954) and Hans Baumann (1914–1988). Within the approximately 25% of the collection that is made up of spoken word recordings, there are a number of Hörspiele as well as other cultural content (humorous sketches, poems, lectures and educational talks) and a significant number labelled as ‘news’ including public and Nazi party events and speeches. Some prominent Nazi figures feature here (including Hitler, Goebbels, Himmler, and Hess). There are some differences between those items on disc and those on matrix which suggest the former may have come from regional broadcasting stores (they are exclusively pre-war recordings, largely from Stuttgart or Frankfurt) and the latter from a more central collection (the latest is from 1944 and most are of non-specific origin, labelled RRG or Deutschlandsender), but no documentation to substantiate this.

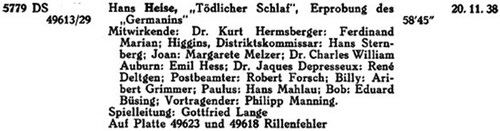

The spreadsheet itself also exemplifies some of the problems faced by archives in terms of metadata. For some items in the collection—notably those from the pre-war era which are included in the printed RRG catalogues—the matrix number can be matched to an often very detailed entry. In the case of a long musical recording, a single catalogue entry can cover dozens of discs with each short piece detailed, including performers (orchestras and soloists), conductors, venues, dates, length of each individual piece as well as composer and title, the transmitter/station which originally recorded it and—in some cases—technical notes on sound quality. To make the task of cataloguing the KF itself more achievable, this data has been largely curtailed or—in some cases—omitted from the spreadsheet. An example is shown in and .

Figure 1. Entry for DS 49613/29 in RRG Catalogue, 1939Footnote47

TABLE 1. Corresponding entry for DS 49613/29 in Czech Radio’s KF spreadsheet

While both entries include the matrix numbers, date of recording, original broadcaster, author surname and first title, much of the other information is lacking from the spreadsheet. The RRG entry tells us this is a radio play (as it is in the corresponding section of the catalogue), where the KF description not only omits this but also implies (through its mention of ‘Soloists’) that it may be music. The RRG lists ten members of the cast and their characters’ names, as well as a note on ‘groove errors’ on two particular discs, none of which is recorded in the KF entry. The spreadsheet does provide some information specific to the KF, however, namely that only the first two parts of the recording are also preserved on disc, and that there is a copy on R-DAT, meaning this was one of the lost recordings requested by the DRA in the 1990s. Someone consulting the catalogue specifically for reference to radio plays might overlook this, however, as there is no category signifying its content, and details of the cast and characters would not be searchable.

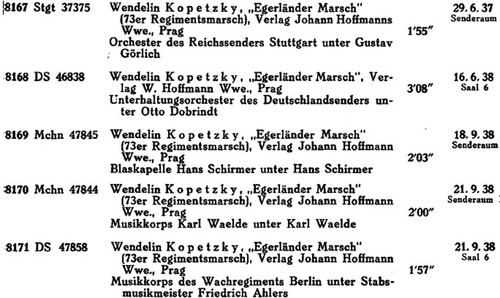

A further challenge facing many transnational collections is also made clear here: the question of translation.Footnote40 As seen above—where ‘Tödlicher Schlaf’ has become ‘Smrtící spánek’ [Deadly Sleep]—much of the information on the KF has been translated into Czech in the spreadsheet. While this is intended to make the spreadsheet (and therefore its recordings) more accessible to Czech programme-makers and archival visitors, it does of course add a barrier to those who do not speak Czech, and risks the possibility of translation errors. There is also the question of whether or not to ‘translate’ names into more standard Czech spellings or equivalents. For example, shows five different recordings of the ‘Egerländer Marsch’ by Wendelin Kopetzky in the 1939 RRG catalogue.

FIGURE 2. Wendelin Kopetzky pieces in the RRG Catalogue, 1939Footnote48

All five of these recordings are preserved in the KF but two of them are attributed to ‘Kopetzky, W.’ (preserving the German spelling), one to ‘Kopecký, W.’ (using a Czech spelling for the surname, but preserving the W for the first name), and three to ‘Kopecký, V.’ (using Czech variants for both names). Similarly, four of the five recordings are listed as ‘Chebský pochod’, and one as ‘Egerländer Marsch’, with Cheb and Eger being the Czech and German names respectively for the same city in what is today the west of the Czech Republic. Thus the possible distortion of translation is added the constraints of time and length already imposed by the data transfer process, resulting in the omission of a great deal of metadata from the spreadsheet. Even were a researcher able to access this source, they would therefore need knowledge of both German and Czech and would still risk limitations on what they could find.

Conclusion

It is my contention that the ‘activation’ of a transnational collection like the KF—by which I mean the making of the objects within it fully findable and usable to interested parties—requires international collaboration, in this case including the combined expertise and resources of both Czech Radio and the DRA. In my discussions with each institution, I have established that interest in the collection continues on the DRA side, that archivists at Czech Radio agree that its international collections have been overlooked, and that both are keen to engage in international collaboration. There are some practical obstacles to this, from general challenges such as that of language (although co-operation in the 1990s was largely conducted in German, the only shared language between current staff is English, imposing an additional level of translation on communication) to specific challenges relating to this collection, such as those outlined above. In theory, however, standardisation on e.g. naming conventions and translation could be agreed, and time invested to correct existing errors and to fill in gaps in the existing spreadsheet where possible (for example, some entries currently marked as ‘unknown’ are included in the 1939 RRG catalogue and easily findable using OCR scans).Footnote41 Once this catalogue is as complete as possible, it could be better promoted within Czech Radio (and ideally incorporated into the main database). The discs and tapes could be digitised on demand, although digital archival objects are no more immune to the problems of obsolescence than older formats and digital preservation is an ongoing challenge faced by AV heritage institutions.Footnote42 Sourcing a specialised stylus to transcribe from matrix discs is a further difficulty, meaning the fundamental issue of accessing the recordings held solely on matrix would likely remain.

However, the largest single obstacle to such collaboration is likely to be the perennial challenge of resourcing, both in terms of financing and of staffing. While the potential preservation projects an institution like the Czech Radio archive could pursue are numerous, the amount of funding available is distinctly finite, and a strong case would have to be made to prioritise this collection over others.Footnote43 Previous studies of ‘joint’ or ‘shared archival heritage’ could offer possible solutions here, however; Riley Linebaugh has charted how a general move away from post-war conceptions of shared human heritage in favour of more rigid understandings of national ‘ownership’ of archives has accompanied international disputes over post-colonial collections, and highlighted how integral formal international agreements and frameworks often are to the defining and processing of ‘joint heritage’ in such cases.Footnote44 The 1990s collaboration on the KF is an example of the kind of work that can be done with a shared transnational collection when there is no accompanying political dispute, and it is possible that taking a wider view of the heritage contained within the collection—the shared European cultural heritage of much of the musical content for example—would simultaneously widen the field of interested institutions. A multi-lateral collaboration incorporating such bodies could provide a further pooling of resources, making ‘activation’ more affordable for all involved.

Until it is explored in more detail, we cannot know whether the KF is concealing treasures on a par with the much celebrated wartime Wilhem Furtwängler recordings recovered from Russia or something more modest, but such a diverse collection is bound to offer material of interest to scholars in a range of fields.Footnote45 As has been mentioned, previous bilateral collaboration has meant that researchers today are able to access some of the spoken word recordings of most mainstream interest (i.e. plays by popular authors, speeches by prominent Nazis, wartime reportages) via the DRA, but this is only a fraction of the collection. As far as I am aware, no research has been done into the musical holdings which may contain unique recordings and interpretations, and archivists at Czech Radio estimate that up to 30% of the discs have not been identified at all. The KF may therefore be of interest to musicologists and others, as well as historians of Nazi Germany, but few are likely to come across it until it is ‘activated’. While all material would ideally be digitised and accessible, this is likely to remain a distant dream unless the collection receives some specific funding; as Irena Řehořová has pointed out in the case of the Czech National Film archive, the ideal of a digitised, accessible AV collection often does not correspond to archival realities.Footnote46 The KF thus remains displaced, inactive, and in an awkward position: not in-demand enough to warrant attention in an environment of limited resources, but unable to initiate demand until it receives some attention.

Acknowledgements

Original research for this article was conducted at the Czech Radio archive in Prague, the Bundesarchiv Berlin, and the Deutsches Rundfunkarchiv (Frankfurt and Potsdam). The author would like to thank the staff of these institutions, as well as those of the University of Amsterdam Department of Media Studies, notably Dr Carolyn Birdsall of the TRACE project. This work was funded by the Dutch Research Council (NWO) under Grant 016.Vidi.185.219.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Erica Harrison

Erica Harrison, Department of Media Studies, Universiteit van Amsterdam, Netherlands, Amsterdam. E-mail: [email protected]

Notes

1 Česko-německá novinářská cena, ‘Pavel Polák’.

2 Polák won the Czech-German Journalism Prize for ‘Tajemný kořistní fond.’

3 I have used the name ‘Kořistní fond’ and associated abbreviation (KF) throughout this paper, as this is the name commonly used to refer to this collection in the other sources cited. However, as discussed in more detail in the section 'Loot or Leftovers?', I believe this title to be inaccurate as the evidence suggests this collection does not constitute war loot.

4 More information on the TRACE Project and associated publications can be found on trace.humanities.uva.nl.

5 Birdsall and Harrison, ‘Introduction,’ 5–6.

6 The German Broadcasting Archive (Deutsches Rundfunkarchiv, DRA) was founded by the ARD (Arbeitsgemeinschaft der öffentlich-rechtlichen Rundfunkanstalten der Bundesrepublik Deutschland), the consortium of German regional public broadcasters, and Deutschlandradio (the national public radio broadcaster).

7 Lowry, Displaced Archives, 1.

8 Lowry, ‘Displaced Archives,’ 142.

9 von Oswald and Tinius, Awkward Archives, 19.

10 Brunow, ‘Curating Access,’ 99.

11 Berger, ‘The Role of National Archives.’ On Entangled media histories see Cronqvist and Hilgert, ‘Entangled Media Histories,’ 131. Also the various responses to it.

12 Paalman et al., ‘Introduction,’ 4.

13 Correspondence relating to this collaboration is held in DRA Frankfurt, in the folder ‘Prerov-Prag’.

14 Polák and the articles about his programme both refer to the collection as a ‘treasure’, the more modest assessment was made by an employee of Czech Radio to the author in March 2022.

15 Yaneva Crafting History, 11; Buchanan and Bastian, ‘Activating the Archive.’

16 Paalman et al., ‘Introduction,’ 2.

17 Edmondson, Audiovisual Archiving, v; also 55–6.

18 Cocciolo, Moving Image, 51. Cocciolo advocates for digital migration of analogue materials ‘rather than relying on aging media carriers and obsolete playback equipment’, but notes that the degree to which this is possible depends on the size of the institution.

19 Valentyn, ‘Die Entwicklung der Schallaufzeichnung,’ 235.

20 See for example Rodriguez and Tomlinson, ‘Tune Chasin' the Past.’

21 Czech Radio. ‘Kodex Českého rozhlasu,’ Article 13.

22 Polák, ‘Tajemný kořistní fond.’

23 See, for example, Föllmer and Badenoch, Transnationalizing Radio Research; Europeana Sounds was a 2014–17 project aggregating digitised sound content from a range of European institutions, see eusounds.eu/.

24 A number of such studies are included in Lowry, Displaced Archives.

25 Näripea, Special Issue.

26 Berger, ‘The Role of National Archives.’

27 Özgen and Rongen-Kaynakçi, ‘Transnational Archives,’ 82; 78.

28 See for example ‘Betr: Luftschutzmassnahmen in Archiven [Re: Air protection measures in archives]’, Zipfel to Reichsprotektor, 8 August 1942 in ÚŘP, Pododdělení I3e (Swientkova registratura), Inv. Č. 1, sign. 6000A.

29 Examples of requisition slips can be seen in ÚŘP, Inv. Č. 14, sign. 6100, ka. 4.

30 Thürmer, ‘Sendergruppe Böhmen-Mähren,’ 28

31 Eisenhofer, ‘Mein Leben beim Rundfunk,’ 176; Kaiser, ‘Einblick in die Tonabteilung [Insight into the Sound Department]’ in DRA Frankfurt, ‘Prerov—Prag’. Eva Ješustová’s suggestion that the collection was moved from Dresden to Plzeň for safekeeping, and that from there one quarter was taken to Prague and the remaining three quarters to Moscow by the Red Army, has not been possible to substantiate as yet.

32 Polák, ‘Tajemný kořistní fond.’

33 Spalová, ‘Remembering the German Past.’

34 Soukup, ‘Zakleté hlasy,’ 1; Jiraková, ‘The Programme and Archive,’ 285.

35 DRA. ‘Über uns [About us].’ DRA. Accessed 3 December 2023. https://www.dra.de/de/das-dra/ueber-uns

36 Wagner, ‘Günter Eich.’ In Germany the collection is known as the ‘Prager Funde’ or ‘Prague findings’.

37 The author interviewed Joachim-Felix Leonhard, Director of the DRA 1991–2001, on 16 December 2022.

38 Said to the author during an archive visit in March 2022.

39 Given that the spreadsheet does not include all data for all 4,055 entries, the analysis recorded here is based on approximated data (wherever data is missing I have excluded that entry from that calculation).

40 One case study of enabling multilingual access in digital collections is Mutusiak et al., ‘Multilingual Metadata.’

41 Optical Character Recognition creates a readable—and therefore searchable—PDF version of a scanned document. Such scans of the RRG catalogues are already in use in the TRACE project.

42 Cocciolo, Moving Image, 57–8.

43 These comments are based on conversations I have had with representatives at both institutions at various times in 2022.

44 Linebaugh, ‘Joint Heritage,’ 20–4; 31–4.

45 Schulz, ‘Attention Please, Recording!’ Having been taken to Russia in the 1940s, a number of recordings of wartime concerts by the Berlin Philharmonic conducted by Furtwängler were returned to Germany in the 1980s and 1990s, remastered, and released.

46 Řehořová, ‘Curating Access.’

47 RRG, Schallaufnahmen der Reichs-Rundfunk, 305.

48 Ibid., 666.

Bibliography

- Berger, Stefan. “The Role of National Archives in Constructing National Master Narratives in Europe.” Archival Science 13, no. 1 (2013): 1–22. doi:10.1007/s10502-012-9188-z.

- Birdsall, Carolyn, and Erica Harrison. “Introduction: Researching Archival Histories of Radio.” TMG Journal for Media History 25, no. 2 (2022): 1–12. doi:10.18146/tmg.841.

- Brunow, Dagmar. “Curating Access to Audiovisual Heritage: Cultural Memory and Diversity in European Film Archives.” Image & Narrative 18, no. 1 (2017): 97–110. http://ojs.arts.kuleuven.be/index.php/imagenarrative/article/view/1486.

- Buchanan, Alexandrina, and Michelle Bastian. “Activating the Archive: Rethinking the Role of Traditional Archives for Local Activist Projects.” Archival Science 15 (2015): 429–451. doi:10.1007/s10502-015-9247-3.

- Česko-německá novinářská cena [Czech-German Journalism Prize]. “Pavel Polák ‘Tajemný kořistní poklad [Mysterious Looted Treasure]’”. Accessed April 3, 2023. http://cesko-nemecka-novinarska-cena.cz/story/pavel-polak-tajemny-koristni-poklad/.

- Cocciolo, Anthony. Moving Image and Sound Collections for Archivists. Chicago, IL: SAA, 2017.

- Cronqvist, Marie, and Christoph Hilgert. “Entangled Media Histories: The value of Transnational and Transmedial Approaches in Media Historiography.” Media History 23, no. 1 (2017): 130–141. doi:10.1080/13688804.2016.1270745.

- Czech Radio. “Kodex Českého rozhlasu” [Codex of Czech Radio]. Czech Radio. Accessed April 3, 2023. http://rada.rozhlas.cz/kodex-ceskeho-rozhlasu-7722382.

- Edmondson, Ray. Audiovisual Archiving: Philosophy and Principles. Paris: UNESCO, 2004. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000243973.

- Eisenhofer, Matthäus. Mein Leben beim Rundfunk: Erinnerungen und Berichte [My Life in Broadcasting: Memoirs and Reports]. Gerlingen: Bleicher Verlag, 1970.

- Föllmer, Golo, and Alexander Badenoch, eds. Transnationalizing Radio Research: New Approaches to an Old Medium. Bielefeld: transcript Verlag, 2018.

- Jiraková, Jana. “The Programme and Archive Collections of Czechoslovak Radio in Prague.” Fontes Artis Musicae 38, no. 4 (1991): 282–287. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23507986.

- Linebaugh, Riley. “‘Joint Heritage’: Provincializing an Archival Ideal.” In Disputed Archival Heritage, edited by James Lowry, 19–48. London: Routledge, 2022.

- Lowry, James, ed. Displaced Archives. Abingdon: Routledge, 2017.

- Lowry, James. “‘Displaced Archives’: Proposing a Research Agenda.” In Archives in a Changing Climate – Part I & Part II, edited by V. Frings-Hessami and F. Foscarini, 141–150. Cham: Springer, 2022. doi:10.1007/s10502-019-09326-8.

- Mutusiak, Krystyna, Ling Meng, Ewa Barczyk, and Chia-Jung Shih. “Multilingual Metadata for Cultural Heritage Materials: The Case of the Tse-Tsung Chow Collection of Chinese Scrolls and Fan Paintings.” The Electronic Library 33, no. 1 (2015): 136–151. doi:10.1108/EL-08-2013-0141.

- Näripea, Eva. “Special Issue on Film Archives in Eastern Europe.” Studies in Eastern European Cinema 11, no. 2 (2020). http://www.tandfonline.com/toc/reec20/11/2?nav=tocList.

- Özgen, Asli, and Elif Rongen-Kaynakçi. “Transnational Archive as a Site of Disruption, Discrepancy, and Decomposition: The Complexities of Ottoman Film Heritage.” The Moving Image 21, no. 1–2 (2021): 77–99. doi:10.5749/movingimage.21.1-2.0077.

- Paalman, Floris, Giovanna Fossati, and Eef Masson. “Introduction: Activating the Archive.” The Moving Image 21, no. 1-2 (2021): 1–25. doi:10.5749/movingimage.21.1-2.0001.

- Polák, Pavel. “Tajemný kořistní fond” [The Mysterious Loot Collection]. Zaostřeno (radio programme), Český rozhlas PLUS, Prague, Czech Republic, February 14, 2017. http://prehravac.rozhlas.cz/audio/3903210.

- ‘Prerov-Prag. Archive folder, Deutsches Rundfunkarchiv [DRA], Frankfurt.

- Řehořová, Irena. “Curating Access, Shaping Cultural Memory: The Czech National Film Archive in the Era of Digitisation.” Studies in Eastern European Cinema 11, no. 2 (2020): 186–201. doi:10.1080/2040350X.2019.1708044.

- Rodriguez, Sandy, and Christina Tomlinson. “‘Tune Chasin’ the Past: Unlocking the Hidden Contents of a Disc Stamper Collection.” Poster at International Association of Music Libraries, Archives, and Documentation Centres. Congress (26 July 2012: Montréal, Québec). http://mospace.umsystem.edu/xmlui/handle/10355/48325.

- RRG. Schallaufnahmen der Reichs-Rundfunk G.m.b.H von Anfang 1936 bis Anfang 1939 [Sound recordings of the Reichs-Rundfunk G.m.b.H from the start of 1936 to the start of 1939]. Berlin: RRG, 1939.

- Schulz, Eric. “Attention please, Recording!” In Berliner Philharmoniker: Wilhelm Furtwängler, The Radio Recordings, 1939–1945. Berlin: Berlin Phil Media, 2018.

- Soukup, Ivan. “Zakleté hlasy” [Enchanted Voices]. Haló sobota (Rudé právo), June 15, 1981.

- Spalová, Barbora. “Remembering the German Past in the Czech Lands: A Key Moment Between Communicative and Cultural Memory.” History and Anthropology 28, no. 1 (2017): 84–109. doi:10.1080/02757206.2016.1182521.

- Thürmer, Ferdinand. “Sendergruppe Böhmen-Mähren.” Archive folder A04/18, DRA Potsdam.

- Úřád říšského protektora [ÚŘP, Office of the Reichsprotektor]. Archival series, National Archives Czech Republic.

- Valentyn, E. van den. “Die Entwicklung der Schallaufzeichnung im Grossdeutschen Rundfunk” [The Development of Sound Recording in Greater German Radio]. Reichsrundfunk, August 31, 1941, 234–239.

- Von Oswald, Margareta and Jonas Tinius, eds. Awkward Archives: Ethnographic Drafts for a Modular Curriculum (Volume 1). Berlin: Archive Books Berlin, 2022.

- Wagner, Hans-Ulrich. “Günter Eich: Rebellion in der Goldstadt.” Rundfunk und Geschichte 24, no. 4 (1998): 268–269. http://rundfunkundgeschichte.de/assets/RuG_1998_4.pdf.

- Yaneva, Albena. Crafting History: Archiving and the Quest for Architectural Legacy. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2020.