Abstract

The genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) affects up to 84% of postmenopausal women and may significantly reduce the quality of life in some. For symptom relief, there are several non-hormonal and hormonal vaginal products available. In Europe, vaginal estriol (E3) is the most frequently chosen estrogen for GSM treatment. The aim of this systematic review was to assess the impact of vaginal E3 on serum sex hormone levels, an outcome that has been previously used to assess safety in similar products. In our review, we did not find any alterations in serum estrone, estradiol, testosterone, progesterone and sex hormone binding globulin levels after vaginal E3 application. In contrast, some studies showed a minimal and transient decrease in serum gonadotropin levels, which however remained within the postmenopausal range. Similarly, only a few studies reported a minimal and transient increase of serum E3 levels, with the rest reporting no changes. The lack of clinically relevant long-term changes in serum sex hormone levels supports the current literature providing evidence about the safety of vaginal E3 products.

摘要

高达84%的绝经后妇女患有更年期泌尿生殖系统综合征, 可能会显著降低一些妇女的生活质量。为了缓解症状, 有几种非激素和激素阴道产品可供选择。在欧洲, 阴道雌三醇(E3)是GSM治疗中最常用的雌激素。这项系统综述的目的是评估阴道E3对血清性激素水平的影响, 这一结果以前曾用于评估类似产品的安全性。在我们的综述中, 我们没有发现阴道E3应用后血清雌激素、雌二醇、睾酮、孕酮和性激素结合球蛋白水平有任何变化。相反, 一些研究显示, 血清促性腺激素水平略有短暂下降, 但仍在绝经后范围内。同样, 只有少数研究报告了血清E3水平的微小和短暂升高, 其余研究报告没有变化。血清性激素水平缺乏临床相关的长期变化, 这支持了目前提供阴道E3产品安全性证据的文献。

Introduction

The term genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) was introduced as an all-encompassing term for vulvovaginal and bladder atrophy by the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH) and North American Menopause Society (NAMS) in 2014 [Citation1] and describes the hypoestrogenic changes to the vulvovaginal and bladder–urethral areas that occur in menopausal women [Citation2]. GSM symptoms may comprise genital, sexual and urinary symptoms [Citation3]. Symptoms associated with GSM are highly prevalent, affecting up to 84% of postmenopausal women [Citation4], and may have a negative impact on quality of life [Citation3]. Even among menopausal women using systemic menopausal hormone therapy, about 45% still experience GSM symptoms [Citation2].

First-line therapy for GSM symptoms is non-hormonal products [Citation5]. If not sufficient, vaginal estrogens are recommended [Citation5]. According to current guidelines, this may also apply to women suffering from, for example, hormone-sensitive cancers [Citation5]. Approved vaginal estrogens comprise conjugated equine estrogens (CEE), estradiol (E2) and estriol (E3). Yet approval status is not the same internationally. For example, vaginal E3 has not been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for GSM treatment. Hence, it is not listed in the NAMS guideline on GSM management [Citation5]. In Europe, on the contrary, vaginal E3 is the most frequently chosen vaginal estrogen for GSM management (data based on EFFIK’s internal analysis). Therefore, the aim of this comprehensive systematic review was to assess the impact of vaginal E3 on sex hormone serum levels, GSM signs and symptoms, and breast safety. Here, we address the first topic – the other two will follow in separate publications.

Methods and materials

Protocol, information sources and search strategy

A protocol with a detailed methodological strategy was developed in a collaboration of all authors and this protocol was prospectively submitted for registration in the PROSPERO database (acknowledgment of receipt: 296147). However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, all systematic reviews not studying COVID-19 were automatically deemed out of scope by PROSPERO and therefore not accepted for registration. The protocol was hence kept in the University of Bern archives and the exact same protocol was later registered with INPLASY (INPLASY202320023).

Complex literature searches were designed on the topic and executed for the following information sources to identify all potentially relevant documents on the topics:

MEDLINE (Ovid) (including epub ahead of print, in-process and other non-indexed citations, MEDLINE Daily and Ovid MEDLINE versions) (1946–30 March 2021)

CINAHL (1937–30 March 2021)

Embase (Ovid) (1974–30 March 2021)

Cochrane Library (Wiley) (1996–30 March 2021)

Web of Science (Clarivate) (1900–30 March 2021)

ClinicalTrials.gov (NLM)

Initial search strategies in MEDLINE/Ovid were drafted by a medical information specialist (H.J.) and tested against a list of core references to see whether they were included in the search results. After refinement and consultation, complex search strategies were set up for each information source based on database-specific controlled vocabulary (thesaurus terms/subject headings) and textwords. Synonyms, acronyms and similar terms were included in the textword search. No limits have been applied in any database considering study types, languages, publication years or any other formal criteria.

The searches were run in the medical bibliographic databases MEDLINE and Embase, the Cochrane Library, CINAHL, Web of Science and ClinicalTrials.gov, an international clinical trials registry. The initial searches were conducted on 31 March 2021, whereas an update using the exact same algorithm was conducted prior to publication, on 26 January 2023.

The search concepts used were ‘postmenopausal women’, ‘genitourinary syndrome of menopause ‘(GSM), ‘vaginal estriol (E3)’ and ‘serum levels’ (estriol, estradiol, follicle stimulating hormone [FSH]).

In addition to electronic database searching, reference lists and bibliographies from relevant publications were checked for relevant studies. The final detailed search strategies are presented in the Supplemental Appendix.

Included were only controlled trials comparing intravaginal application of E3 and their effect on serum hormone levels to other local estrogens, non-hormonal local treatments or E3 in different doses in postmenopausal women (natural or iatrogenic) as well as single-arm pre–post interventional studies [Citation6] studying administration of vaginal E3 monotherapy, systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The serum hormones of interest were mainly E2, E3, and FSH, but estrone (E1), luteinizing hormone (LH), sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG), prolactin (PRL), testosterone and progesterone were also included in the study. Excluded were studies not studying the outcomes of interest or studying local treatments other than vaginal E3 monotherapy or other routes of E3 administration as well as all other study types not falling under the inclusion criteria.

Study selection process

All identified citations were imported into EndNote and duplicates were removed. The remaining citations were imported into the Rayyan Screening tool, and titles and abstracts were independently screened by two authors (A.K. and P.S.) and tested against the inclusion criteria. The full-text screening and the data extraction followed and were conducted by the same team with the same standards. Any discrepancies throughout the process were resolved after discussion. The same process was followed after the updated search before publication.

Results

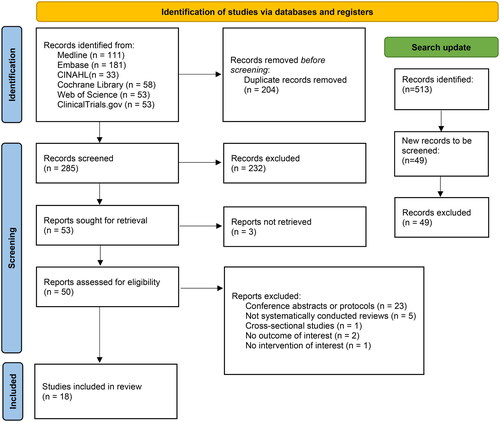

After the initial search, 489 articles were identified and after deduplication 285 articles remained to be screened. A total of 232 articles were deemed out of scope after the initial title and abstract screening and were excluded. The remaining 53 articles were screened in full text. A total of 23 articles were excluded as duplicates, study protocols or conference abstracts, five articles as not systematically conducted literature reviews and one article as a cross-sectional/no intervention study. Two further articles were excluded for not studying our outcome of interest (hormonal serum concentrations) and one article for studying a combined E3/progesterone vaginal product (not monotherapy), whereas for three articles no full-text access could be obtained even after requests to the corresponding authors and as such they had to be excluded. The 18 remaining articles met the inclusion criteria and data were extracted. The updated search returned 49 new articles, none of which fulfilled the inclusion criteria ().

Of the 18 included articles, seven were controlled trials (two placebo-controlled trials, two head-to-head comparisons [E3 vs. CEE], two dose-comparisons, and one placebo-controlled and head-to-head comparison study [E3 vs. E2 vs. placebo]), eight were pre–post interventional studies (six single-arm and two multi-arm), two were systematic reviews and one was a meta-analysis [Citation6–8].

The following serum hormones and protein levels were reported, respectively: E2 by 14 studies [Citation9–23], E3 by 15 studies [Citation9–13,Citation15,Citation18–27], gonadotropins (FSH and/or LH) by 13 studies [Citation9–11,Citation15–17,Citation19–26], E1 by 11 studies [Citation9–11,Citation13,Citation15–21,Citation24], SHBG by 11 studies [Citation9,Citation14–16,Citation19–25], PRL by four studies [Citation9,Citation15,Citation20,Citation24], testosterone by two studies [Citation14,Citation16] and progesterone by one study [Citation22]. Within the two systematic reviews there were seven additional studies that were not picked up by our algorithm and are reported as part of those two reviews [Citation28–34].

Serum estriol

The majority of studies did not observe a change in serum E3 levels after vaginal E3 application [Citation9–13,Citation15,Citation18,Citation20,Citation22,Citation25,Citation27] (). Four studies reported significant changes in serum E3 levels after vaginal E3 application [Citation19,Citation21,Citation24,Citation26]. The first assessed serum E3 levels before and 2 weeks after daily vaginal application of 0.5 mg E3, either as cream or a suppository [Citation24]. Compared to baseline, conjugated serum E3 levels were significantly increased at the end of treatment regardless of application type (from 0.28 ± 0.01 nmol/l to 1.48 ± 0.2 nmol/l for the vaginal cream and from 0.33 ± 0.05 nmol/l to 1.57 ± 0.2 nmol/l for the vaginal suppositories); unconjugated serum E3 levels were only increased after vaginal E3 cream treatment (from <0.05 nmol/l to 0.23 ± 0.08 nmol/l). The second study assessed the pharmacokinetics of daily vaginal application of 0.03 mg E3 for 4 weeks, followed by a maintenance therapy three times weekly for 8 weeks [Citation21]. As the serum E3 peak level was significantly lower and somewhat delayed at week 4 compared to baseline (from a maximum concentration of 168 pg/ml at 3 h post administration to a maximum of 43.7 pg/ml at 8 h post administration), a minimal and transient systemic E3 absorption was suspected. Another pharmacokinetics study found a dose-proportional increase of serum E3 after single application of 0.002% and 0.005% E3 vaginal gel but a less than dose-proportional increase for the 0.1% E3 vaginal cream [Citation26]. The same study concluded that the systemic exposure is reduced after chronic use, as after daily treatment with the aforementioned doses for 21 days the mean serum E3 was lower in each group to a statistically significant degree for the two lower concentration products (no arithmetic results available). A systematic review of 22 studies included three additional studies that reported significant but transient serum E3 level increases after vaginal E3 application [Citation19]. Normalization of serum E3 levels was found 8 h (vaginal 0.5 mg E3 ovula – from a baseline of 0.15 nmol/l to an increase to 0.4 nmol/l at 4 h and normalization to <0.10 nmol/l at 8 h) [Citation32], 24 h (unconjugated serum E3 levels: vaginal 0.5 mg E3 suppository and cream – from a baseline of zero for both to 0.3 nmol/l at 30 min for both, a further increase to 0.51 nmol/l for the suppositories and 0.61 nmol/l for the cream at 1 h and normalization after 24 h for both) and 48 h (conjugated serum E3 levels: vaginal 0.5 mg E3 suppository and cream – from a baseline of 0.3 nmol/l for both to 1.43 nmol/l at 8 h for the suppositories and 1.33 nmol/l at 4 h for the cream to normalization after 48 h for both) [Citation33] after singular application [Citation32], or after a 14-day application respectively [Citation33]. The third study concluded that vaginal absorption of E3 (measured by unconjugated serum E3 levels – area under the curve 9133 on day 0 to 6743 on day 21) declined with time after daily treatment with vaginal E3 suppositories at 1 mg for 21 days [Citation30].

Table 1. Effects of vaginal estriol (E3) on serum E3 levels.

Serum estradiol and estrone levels

None of the identified studies reported an increase of serum E2 [Citation9–22] or E1 [Citation9–11,Citation13,Citation15–21,Citation24] levels after vaginal E3 application ( and Supplemental Table 1). This indeed is no surprise as the enzymatic metabolization from E2 to E1 to E3 is a ‘one-way street’ [Citation35]. In contrast, one study using vaginal CEE at 1.25 mg per day as a comparator found a significant increase in serum E2 and E1 levels [Citation9]. However, if vaginal CEE was applied at a lower dose (0.625 mg) and frequency (daily for 2 weeks and then once weekly for 2 years), serum E2 levels remained unchanged after 2 years [Citation14]. Similarly, studies using vaginal E2 as a comparator did not report significant long-term serum E2 [Citation16,Citation32,Citation34] or serum E1 [Citation16,Citation32,Citation34] level changes, respectively.

Table 2. Effects of vaginal estriol (E3) on serum estradiol (E2) levels.

Serum gonadotropin levels

Six [Citation9–11,Citation21,Citation22,Citation24,Citation26] out of 13 identified studies [Citation9–11,Citation15–17,Citation19–22,Citation24–26] reported significant changes in serum FSH levels, two of which also found significant changes in serum LH levels [Citation9,Citation22] (). Vaginal E3 at 0.5 mg daily for 2 weeks followed by 0.5 mg twice weekly for 6 weeks significantly decreased serum FSH levels without affecting LH (from a baseline of 14.2 μg/l to 13.5 μg/l at 2 weeks for the cream and from 14.9 μg/l to 13.7 μg/l for the suppositories) [Citation24]. Similarly, high-dose vaginal E3 cream at 0.1% daily for 3 weeks significantly decreased serum FSH levels (from 79.1 IU/l on day 1 to 68.25 IU/l on day 21), which was not found for lower doses (0.005%, 0.002%) [Citation26]. Indeed, the dose and frequency of vaginal E3 application are relevant factors. Daily application of vaginal E3 at 0.5 mg for 2 weeks [Citation22], at 0.05 mg for 3 weeks [Citation10,Citation11] or at 0.03 mg for 4 weeks [Citation21], respectively, significantly decreased serum FSH levels (from 75.7 mU/ml on day 1 to 66.0 mU/ml on day 14, from a baseline of 54.6 mIU/ml to 47.6 mIU/ml on day 7, and from a baseline of 107.88 mU/ml to 98.94 mU/ml on day 28, respectively). Serum FSH levels returned to baseline levels when the application frequency of vaginal E3 at 0.03 mg was reduced to three times weekly for 8 weeks (103.55 mU/ml) [Citation21] and the frequency of vaginal E3 at 0.05 mg to two times weekly for 9 weeks (51.4 mIU/ml) [Citation10,Citation11]. When comparing vaginal E3 to other vaginal estrogen therapies, Luisi et al. showed that the daily use of 1.25 mg vaginal CEE for 3 weeks decreased both FSH and LH more than daily use of 0.5 mg vaginal E3 throughout the treatment (days 8, 15 and 21), at a statistically significant level (FSH from a baseline of 75.2 mIU/ml to 70.5 mIU/ml on day 21 for the vaginal E3 group and from a baseline of 71.0 mIU/ml to 55.6 mIU/ml on day 21 for the CEE group) [Citation9].

Table 3. Effects of vaginal estriol (E3) on serum gonadotropin (FSH and LH) levels.

Serum SHBG levels

None of the included studies induced significant changes in serum SHBG levels after vaginal E3 application [Citation9,Citation14–16,Citation19–22,Citation24] (Supplemental Table 1). In contrast, one study using vaginal CEE at 1.25 mg per day as a comparator found a significant increase of serum SHBG levels [Citation9].

Serum prolactin, testosterone and progesterone levels

All but one study [Citation24] reported no impact of vaginal E3 application on serum PRL levels (Supplement Table 1). The latter reported a significant increase in serum PRL levels after application of vaginal E3 cream at 0.5 mg daily for 2 weeks but not for vaginal E3 suppositories at the same dose and frequency of application [Citation24]. Serum testosterone [Citation14,Citation16] and progesterone [Citation22] levels remained unchanged after vaginal E3 application, which again is no surprise as E3 cannot be enzymatically metabolized ‘back’ to E2, testosterone and progesterone.

Discussion

This systematic review did not find any clinically relevant long-term serum hormone or protein level changes. Serum levels are often used as a proxy when studying the safety of vaginal estrogenic products [Citation10,Citation11,Citation17,Citation19–21,Citation23], although that is not a prerequisite posed by authorities’ guidelines (either the FDA or European Medicines Agency [EMA]) [Citation36,Citation37]. Due to the enzymes’ characteristics in sex hormone synthesis, an increase of serum E1, E2, testosterone and progesterone levels after E3 application is simply impossible [Citation35]. The reported increase in serum E3 levels by some studies can be explained as a direct effect of vaginal absorption. Indeed, several other studies on the effect of vaginal E2 on serum levels of estrogens only showed a small increase in serum E2 levels, which was the estrogen that was directly applied and absorbed in that case [Citation38,Citation39] and failed [Citation38,Citation40] or only found a small increase [Citation39] in the levels of E1. This increase in E1 could be explained by the potential conversion of E2 to E1 through 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, a step that is not even feasible after application of E3, as there is no known physiological pathway for the conversion of E3 to a different type of estrogen. In theory, vaginal application of E2 could also lead to an increase in serum E3, but we were not able to find any studies on that topic.

Only one study reported an increase in serum PRL levels [Citation24], which can probably be attributed to the known fluctuation of PRL itself. Furthermore, there were no serum PRL level changes if the same vaginal E3 dose was applied in another galenic form [Citation24]. Also, the reported increased serum PRL level was within the normal range and thus clinically irrelevant.

Although some studies found significant alterations in serum gonadotropin levels [Citation9–11,Citation21,Citation22,Citation24,Citation26], they always remained within the postmenopausal range and are thus clinically irrelevant. When looking only into data from studies that used lower-dose E3 vaginal preparations (<0.5 mg), two studies [Citation10,Citation11,Citation26] still reported a statistically significant decrease in FSH with a 0.03 mg and a 0.05 mg preparation, yet as mentioned those decreases were transient and clinically insignificant with the lowest reported FSH to be at 68.25 IU/l (decreased from a baseline of 79.1 IU/l).

Thus, the only clinically relevant serum hormone level change would be that of E3. The majority of studies did not report any changes in serum E3 levels after vaginal E3 application [Citation9–13,Citation15,Citation18,Citation20,Citation22,Citation25,Citation27]. The remainder only found transient increases of serum E3 levels [Citation19,Citation21,Citation24,Citation26], and importantly no significant differences when compared to vaginal E2, CEE or placebo application [Citation9–11,Citation19,Citation32]. If we focus again on studies using low-dose E3 preparations (<0.5 mg), there are still two to report statistically significant increases in serum E3 levels [Citation21,Citation26]. This increase was less prominent for those preparations when compared to the 0.5 mg preparations, while as mentioned it seemed to be less prominent with chronic use of the products. Of note, the method used to measure the serum E3 did not appear to have significant effect on the results. All included studies used either radioimmunoassay, gas chromatography–mass spectrometry or liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry, yet all three methods were used both in studies reporting no changes as well as in those reporting a statistically significant increase.

There are also some limitations to this systematic review. First, some studies were conducted for pharmacokinetic purposes allowing no extrapolation to long-term use. Secondly, sample sizes were quite small, which is common for pharmacokinetic studies. Third, comparisons between studies were difficult due to different doses, galenic forms and application frequencies.

Overall, the results of our systematic review support previous reviews that vaginal E3 application in postmenopausal women does not cause any clinically significant serum hormone level changes [Citation17,Citation19]. Furthermore, from a biochemical point of view, E3 products have a lower potential to alter the rest of serum estrogens when compared with E2 products, as there is no known pathway for the conversion of the less potent E3 to the more potent E2. However, in order to assess the long-term safety of vaginal E3 products and be able to draw definite conclusions, larger observational and randomized trials would be necessary with additional endpoints other than serum hormone levels, such as estriol conjugates in the breast, endometrial or myometrial tissue.

Conclusions

Vaginal E3 for GSM treatment does not exert clinically relevant effects on serum sex hormone levels. Thus, based on the current literature and considering serum hormones’ alterations as a proxy for safety, vaginal E3 products can be considered as safe as other vaginal estrogens.

Potential conflict of interest

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. P. Stute, C. Betschart and D. Wunder have been part of an interdisciplinary expert board funded by EFFIK SA. A. Kolokythas reports no conflict of interests. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Source of funding

Nil.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (248.2 KB)Supplemental Material

Download PDF (258.8 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Marc von Gernler from the University Library of Bern for his valuable help in the literature searches, especially the update prior to publication.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Portman DJ, Gass MLS, Vulvovaginal Atrophy Terminology Consensus Conference Panel. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2014;21(10):1063–1068. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000329.

- Crean-Tate KK, Faubion SS, Pederson HJ, et al. Management of genitourinary syndrome of menopause in female cancer patients: a focus on vaginal hormonal therapy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222(2):103–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.08.043.

- Shim S, Park KM, Chung YJ, et al. Updates on therapeutic alternatives for genitourinary syndrome of menopause: hormonal and non-hormonal managements. J Menopausal Med. 2021;27(1):1–7. doi: 10.6118/jmm.20034.

- Baber RJ, Panay N, Fenton A. 2016 IMS recommendations on women’s midlife health and menopause hormone therapy. Climacteric. 2016;19(2):109–150. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2015.1129166.

- “The 2022 Hormone Therapy Position Statement of The North American Menopause Society” Advisory Panel. The 2022 hormone therapy position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2022;29:767–794. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000002028.

- Thiese MS. Observational and interventional study design types; an overview. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2014;24(2):199–210. doi: 10.11613/BM.2014.022.

- Nair B. Clinical trial designs. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2019;10(2):193–201. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_475_18.

- Vieta E, Cruz N. Head to head comparisons as an alternative to placebo-controlled trials. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;22(11):800–803. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.11.011.

- Luisi M, Franchi F, Kicovic PM. A group-comparative study of effects of Ovestin cream versus Premarin cream in post-menopausal women with vaginal atrophy. Maturitas. 1980;2(4):311–319. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(80)90033-x.

- Sánchez-Rovira P, Hirschberg AL, Gil-Gil M, et al. A phase II prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled and multicenter clinical trial to assess the safety of 0.005% estriol vaginal gel in hormone receptor-positive postmenopausal women with early stage breast cancer in treatment with aromatase inhibitor in the adjuvant setting. Oncologist. 2020;25(12):e1846-1854–e1854. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2020-0417.

- Hirschberg AL, Sánchez-Rovira P, Presa-Lorite J, et al. Efficacy and safety of ultra-low dose 0.005% estriol vaginal gel for the treatment of vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women with early breast cancer treated with nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitors: a phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Menopause. 2020;27(5):526–534. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001497.

- Wesel S, Etienne J, Lestienne MC. Clinical, cytological and biological study of the intra-vaginal administration of oestriol (Ortho-Gynest) in post-menopausal patients. Maturitas. 1981;3(3-4):271–277. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(81)90034-7.

- Te West NID, Day RO, Hiley B, et al. Estriol serum levels in new and chronic users of vaginal estriol cream: a prospective observational study. Neurourol Urodyn. 2020;39(4):1137–1144. doi: 10.1002/nau.24331.

- Hoz F-DL, Orozco-Gallego H. Estriol vs. Conjugated estrogens of equine origin in the treatment of the genitourinary syndrome of menopause, Ginecol. Obstet México. 2018;86:117–126.

- Haspels AA, Luisi M, Kicovic PM. Endocrinological and clinical investigations in post-menopausal women following administration of vaginal cream containing oestriol. Maturitas. 1981;3(3–4):321–327. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(81)90041-4.

- Biglia N, Peano E, Sgandurra P, et al. Low-dose vaginal estrogens or vaginal moisturizer in breast cancer survivors with urogenital atrophy: a preliminary study. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2010;26(6):404–412. doi: 10.3109/09513591003632258.

- Crandall CJ, Diamant A, Santoro N. Safety of vaginal estrogens: a systematic review. Menopause. 2020;27(3):339–360. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001468.

- Te West N, Day R, Graham G, et al. Serum concentrations of estriol vary widely after application of vaginal oestriol cream. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;87(5):2354–2360. doi: 10.1111/bcp.14635.

- Rueda C, Osorio AM, Avellaneda AC, et al. The efficacy and safety of estriol to treat vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: a systematic literature review. Climacteric. 2017;20(4):321–330. doi: 10.1080/13697137.2017.1329291.

- Kicovic PM, Cortes-Prieto J, Milojević S, et al. The treatment of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy with Ovestin vaginal cream or suppositories: clinical, endocrinological and safety aspects. Maturitas. 1980;3(3-4):321–327. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(80)90029-8.

- Donders G, Neven P, Moegele M, et al. Ultra-low-dose estriol and Lactobacillus acidophilus vaginal tablets (Gynoflor(®)) for vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal breast cancer patients on aromatase inhibitors: pharmacokinetic, safety, and efficacy phase I clinical study, Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;145(2):371–379. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2930-x.

- Pfeiler G, Glatz C, Königsberg R, et al. Vaginal estriol to overcome side-effects of aromatase inhibitors in breast cancer patients. Climacteric. 2011;14(3):339–344. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2010.529967.

- Pavlović RT, Janković SM, Milovanović JR, et al. The safety of local hormonal treatment for vulvovaginal atrophy in women with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer who are on adjuvant aromatase inhibitor therapy: meta-analysis. Clin Breast Cancer. 2019;19(6):e731–e740. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2019.07.007.

- Mattsson LA, Cullberg G. A clinical evaluation of treatment with estriol vaginal cream versus suppository in postmenopausal women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1983;62(5):397–401. doi: 10.3109/00016348309154209.

- de Oliveira Filho RV, Antunes NDJ, Ilha JDO, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of three dosages of oestriol after continuous vaginal ring administration for 21 days in healthy, postmenopausal women. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;85(3):551–562. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13822.

- Delgado JL, Estevez J, Radicioni M, et al. Pharmacokinetics and preliminary efficacy of two vaginal gel formulations of ultra-low-dose estriol in postmenopausal women. Climacteric. 2016;19(2):172–180. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2015.1098609.

- Buhling KJ, Eydeler U, Borregaard S, et al. Systemic bioavailability of estriol following single and repeated vaginal administration of 0.03 mg estriol containing pessaries. Arzneimittelforschung. 2012;62(8):378–383. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1314822.

- Batra S, Iosif S. Progesterone receptors in vaginal tissue of post-menopausal women. Maturitas. 1987;9(1):87–93. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(87)90056-9.

- Keller PJ, Riedmann R, Fischer M, et al. Oestrogens, gonadotropins and prolactin after intra-vaginal administration of oestriol in post-menopausal women. Maturitas. 1981;3(1):47–53. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(81)90019-0.

- Heimer G, Englund D. Estriol: absorption after long-term vaginal treatment and gastrointestinal absorption as influenced by a meal. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1984;63(6):563–567. doi: 10.3109/00016348409156720.

- Heimer GM, Englund DE. Plasma oestriol following vaginal administration: morning versus evening insertion and influence of food. Maturitas. 1986;8(3):239–243. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(86)90031-9.

- Punnonen R, Vilska S, Grönroos M, et al. The vaginal absorption of oestrogens in post-menopausal women. Maturitas. 1980;2(4):321–326. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(80)90034-1.

- Mattsson LA, Cullberg G. Vaginal absorption of two estriol preparations. A comparative study in postmenopausal women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1983;62(5):393–396. doi: 10.3109/00016348309154208.

- van Haaften M, Donker GH, Haspels AA, et al. Oestrogen concentrations in plasma, endometrium, myometrium and vagina of postmenopausal women, and effects of vaginal oestriol (E3) and oestradiol (E2) applications. J Steroid Biochem. 1989;33(4A):647–653. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(89)90055-1.

- Taylor HS, Pal L, Sell E. Speroff’s clinical gynecologic endocrinology and infertility. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2019.

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Estrogen and estrogen/progestin drug products to treat vasomotor symptoms and vulvar and vaginal atrophy symptoms—recommendations for clinical evaluation. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). 2019. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/estrogen-and-estrogenprogestin-drug-products-treat-vasomotor-symptoms-and-vulvar-and-vaginal-atrophy.

- European Medicines Agency. Clinical investigation of medicinal products for hormone replacement therapy oestrogen deficiency symptoms in postmenopausal women - scientific guideline. European Medicines Agency. 2006. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/clinical-investigation-medicinal-products-hormone-replacement-therapy-oestrogen-deficiency-symptoms.

- Mitchell CM, Larson JC, Crandall CJ, et al. Association of vaginal estradiol tablet with serum estrogen levels in women who are postmenopausal: secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(11):e2241743. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.41743.

- Weisberg E, Ayton R, Darling G, et al. Endometrial and vaginal effects of low-dose estradiol delivered by vaginal ring or vaginal tablet. Climacteric. 2005;8(1):83–92. doi: 10.1080/13697130500087016.

- Del Pup L, Postruznik D, Corona G. Effect of one-month treatment with vaginal promestriene on serum estrone sulfate levels in cancer patients: a pilot study. Maturitas. 2012;72(1):93–94. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.01.017.