Abstract

Experiences of time and risk during the COVID-19 pandemic were volatile; exacerbated by lockdowns resulting in working from home, social distancing and home schooling. This article explores embodied temporalities of risk before and during the pandemic in relation to alcohol consumption and breast cancer for a small, non-probability sample of Australian women pre-midlife (aged 25–44). Layered inferential analyses of our data, collected at four timepoints pre- and during- the COVID-19 pandemic, enabled an illumination of the horizons of risk in women’s lives (broadly construed) and the ways these were recalibrated during the pandemic to manage its gendered stressors. Findings from this longitudinal study suggest that future risks of breast cancer were often discounted or faded from view, as new risks with more immediate consequences emerged: including viral transmission and surviving the (gendered) emotional/relational labours of lockdown. The immediacy of alcohol’s effects, both positive and negative, stayed in view however for women and served as a source of reflection around ‘health’ and ‘wellbeing’, with psychosocial wellbeing elevated over physical health. Examining the multiple time-framings of risk which co-existed on the horizons for women in pre-midlife helped us to elucidate challenges to decreasing future breast cancer burden at population levels via alcohol reduction alone. These insights advance scholarship on how gendered temporalities of risk are reflexively embodied in daily life.

Introduction

Population health risk prevention messages assume that when individuals know health risks exist they will do whatever they can to decrease the probability of an adverse health event (Brown et al., Citation2013). Yet, this logic is splintered by the plural and co-existing nature of risks that exist in each person’s life to bring about various un/healthy practices (Blue et al., Citation2014). The way/s in which temporalities of risk are perceived, felt and lived are a critical dimension through which (health) risks can be reflexively managed. Furthermore, ideas about probabilities and the future are subjective (Brown, Citation2020), with some futures feeling more ‘calculable’ or ‘thinkable’ (Dean, Citation1999) than others – in turn proscribing possibilities for risk thinking amidst the pressures of daily life (Warin et al., Citation2015). We explore the multiple time-framings of co-existing risks on the horizons of women in pre-midlife (aged 25–44) and how they might ‘compete’ for women’s prioritisation alongside their perceptions of alcohol-related breast cancer risk. Our empirical data, collected at four timepoints pre- and during-the COVID-19 pandemic, enable us to explore how their risk horizons were recalibrated during the destabilising of pandemic time; where perceptions of a stable future were brought into question (Graham, Citation2020) and living conditions were disrupted by lockdown and distancing requirements. Such scholarship is critical for exploring dis/junctures in the future(s) imagined by public health, populations and individuals (Green & Lynch, Citation2022).

Study context

Understandings of what is ‘risky’, and to or for whom, are socially constructed; they are configured by cultural, material, ideological and economic amalgams (Beck, Citation1992; Douglas, Citation1992; Giddens, Citation1991) that prefigure ideas of control, transgression and blame (Alaszewski, Citation2021). Although risk can be suggestive of an objective reading of reality and future likelihoods (Beck, Citation1992; Lupton, Citation1999), these risks might not be thinkable for everyone in the same way (Dean, Citation1999). Making health risks thinkable to individuals is vital for improving public health outcomes. However, when risks are objectively constructed to mitigate unhealthy futures over particular time periods for certain populations (Green & Lynch, Citation2022), they may not resonate with people’s immediate and present experiences and daily realities (Warin et al., Citation2015) – amidst which health may only be a small part, or absent. Time is a key texture in analyses of (health) risk because it marks out the various periods over which risk/s may unfold (Brown et al., Citation2013). Furthermore, subjectivities or phenomenologies of time (Brown, Citation2020) nuance whether risks are ‘thinkable’ (Dean, Citation1999) in particular moments of the present and anticipations of the future.

In this article we examine perceptions about the risks of (not) drinking alcohol in the present vis a vis its dose-response relationship with breast cancer risk and the distorted temporalities of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our data enable us to illuminate the perceived benefits of drinking alcohol within and over various time-framings, textured by volatile renderings and experiences of the future as engendered by pandemic living. Through this incisive theoretical window, important public health implications for breast cancer prevention are devisable. The breast cancer risk associated with alcohol is accumulated over a lifetime (Donat-Vargas et al., Citation2021); with relative risk of breast cancer increasing by up to 11 per cent with every seven standard drinks consumed per week (Sarich et al., Citation2020). Pre-midlife (ages 25–44) is a critical time for population-level breast cancer risk by reducing women’s alcohol intake (Haydon et al., Citation2016; Kippen et al., Citation2017), given average daily consumption and frequency of consumption peak for Australian women in middle age (Leggat et al., Citation2022). While Australian women in midlife recognise that breast cancer risk increases with age (Meyer et al., Citation2019); it is unclear if or how these long-term risks are visible on the risk horizons (Warin et al., Citation2015) of women during pre-midlife (Agabio et al., Citation2021).

The imagery of a ‘risk horizon’ (Warin et al., Citation2015) captures the competing nature of risks in women’s lives, which are each perceived to unfold over subjectively constructed futures of varying lengths. Prioritising health risks on these horizons is ascribed with moral worth within neoliberal citizenship (Crawford, Citation2004) as part of an ongoing self-project extending from values of responsibility and competence that can keep multiple potential futures in mind which can be reflexively conjured to trade-off competing risks against each other (Giddens, Citation1991). Alcohol and risk are often intertwined for reproductive bodies, with alcohol conveying risks for the pregnant body and therefore instilled in the risk rituals of the female life course (Moore, Citation2019) and even pre-conception, because they might one day carry a foetus (Lee et al., Citation2022). In the temporalities imagined by public health scholarship (Green & Lynch, Citation2022), alcohol is ‘concerning’ (Lang et al., Citation2021) and ‘risky’ (Magnus et al., Citation2022) at all points in the female lifecourse; echoing the dominant focus on maternal health in women’s health agendas globally and failure to recognise women’s noncommunicable disease risks (Carcel et al., Citation2024). Drinking practices typically unfold and are described in relation to public health advice (Vicario et al., Citation2021), for example that ‘drinking responsibly’ signals reflexive competence and balance during early parenting (Baker, Citation2017; Cook et al., Citation2022).

Yet, empirical research elucidates the risks of not drinking that women perceive in their present(s) and potential futures. Not drinking presents risks for everyday relationships, activities and pleasures, such as difficulty switching from daily gendered duties to spaces of pleasure (Kersey et al., Citation2023), difficulty staving off boredom (Emslie et al., Citation2015), making it harder to make sense of female relationships and identities (Moore, Citation2019), to smooth difficulties at home (MacLean et al., Citation2022) and to manage gendered responsibilities of care for themselves and others (Jackson et al., Citation2018). These are short-term realities in which not drinking alcohol is perceived as risky; compounded by the immediate embodied pleasures of drinking alcohol (Poulsen, Citation2015) which might anaesthetise feelings of time passing (Heyes, Citation2020). While these risks are situated against the gendered impacts of the pandemic (Johnson, Citation2022), the prioritisation of women’s pleasure remains problematic in public discourse (Keane, Citation2023). Not drinking may also be considered risky by women who see alcohol in the present attached to the realisation of various open-ended fantasies of what a ‘good life’ is (Lunnay et al., Citation2023) or should be like (Foley et al., Citation2021). The risks of (not) drinking are therefore temporally situated within women’s lives, and cannot be simply aligned or equated with biomedical risk mitigation.

A long and linear future is central to public health’s current imaginings of breast cancer risk, accrued incrementally with each drink across the life course (Donat-Vargas et al., Citation2021). This departs from the short-term risks of consuming alcohol that seem more prescient during drinking sessions generally (Foster & Heyman, Citation2013) and also for women in midlife (Dare et al., Citation2020). The place of alcohol on risk horizons are further inflected by gendered temporal configurations arising from particular cultural-generational landscape/s (Brown, Citation2020). These configurations were disrupted by policy and pragmatic changes during the pandemic (Bröer et al., Citation2021), which distorted experiences of time (Holman et al., Citation2023) and perceptions that time is a standard or knowable continuum at all (Brown et al., Citation2013) that moves towards a certain and controllable future (Graham, Citation2020). The COVID-19 pandemic therefore altered the conditions in which women’s drinking takes place and its perceived value in dealing with stress (Cook et al., Citation2021) in relation to other long-term risks like breast cancer (Lunnay et al., Citation2021). Our manuscript uses unique longitudinal data collected over four timepoints with eight women in different circumstances (n = 31 interviews), to explore: (1) how and where alcohol-related breast cancer risk features in women’s risk horizons during pre-midlife; (2) how these perceptions co-exist with other risks from (not) drinking within pre-midlife and (3) the impact of the pandemic in destabilising the temporal architecture(s) which constitute risk horizons and the reflexive recalibration of competing risks by the women we interviewed.

Methodology

Design and sample

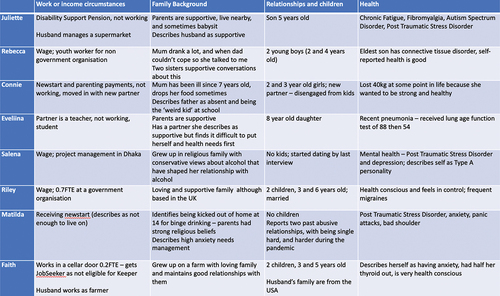

The study was initially designed to recruit 35 pre-midlife women yet was disrupted after interviewing eight women by COVID-19 and the lockdown/distancing restrictions that emerged in Australia in early 2020. We pragmatically adjusted our design to remain engaged with those eight women over time, to understand if/how their perceptions of health risks changed as the pandemic unfolded – with a specific focus on alcohol consumption and perceptions of breast cancer risk. This progressive interviewing pre- and during-pandemic enabled us to focus on the situated in-flux nature of risk practices (Moore, Citation2019) which change over time in relation to experiences of change, insight, and reflection (Saldaña, Citation2003). Our sample purposively included women with differing life chances (access to social, cultural and economic capital, family history, health issues, cultural background); circumstances (living, work, relationship, parenting); and reported alcohol consumption (no alcohol or light consumption through to moderate-heavy consumers). provides the variable social vectors in women’s lives that formed the varied social contexts experienced by our participants.

Recruitment, data collection, and ethics

Women were recruited to the study via known networks, snowballing from other studies, and/or local community centres (particularly to engage women with reduced social and cultural capital). The centres were attended by Author BL to explain the research aims and develop rapport. Women were initially asked to participate in a once-off interview (January 2020), but were re-contacted in March 2020 when the pandemic emerged in Australia to ask if they would participate in a further 3 interviews (April, July, December 2020). Women provided informed consent twice; at the pre-pandemic interview for a single timepoint and then at interview #2 for follow-up at 2 subsequent timepoints. Full ethical approval was provided for this research (including modifications and re-contact) by Flinders University Human Research Ethics Committee (project 7479). A small reimbursement was provided to acknowledge women’s time spent participating. Seven of the eight participants completed all four interviews; one participant (working class position) declined to participate in the final interview; explaining that ‘nothing has changed in my health and alcohol consumption’. Our data set therefore comprises 31 interviews.

Interviews were completed by an experienced qualitative researcher aged in her 40s. Initial interviews were in-person (60–80 minutes) with follow-up interviews 2–4 by Zoom (20–40 minutes). Semi-structured guides were used, developed progressively to account for changes in COVID-19 countermeasures and periods of restrictions as well as emergent findings from previous interviews – so that lines of inquiry regarding health, risks, drinking, time-framings, and pandemic living could be more deeply understood. Examples of questions included ‘Is breast cancer something that has crossed your mind before?’; ‘What makes drinking worthwhile?’; ‘What do you think women you share life with are dealing with?’; ‘What has changed in your list of priorities since COVID?’ or ‘Has COVID had an impact or changed the reasons why you consume alcohol do you think?’

Data analysis

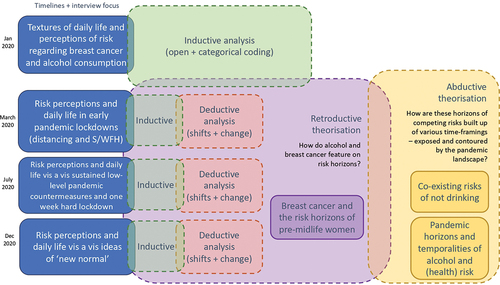

Inductive coding was completed after each round of interviews by author BL to shape the next interviews. Author KF reviewed all interviews in 2021. Transcripts were read to build familiarity with the data; then each participant’s content was coded into a matrix under conceptual headings derived from the first round of interviews (such as ‘alcohol’, ‘a week in the life’, ‘health’, ‘breast cancer’). Categories in each participant’s matrix varied slightly to reflect the nuanced conversations with each participant. Content was added to the matrix for interviews 2–4, resulting in a four-column grid for each participant that contained their key excerpts and ideas captured during each interview (approx. 20 pages of coding per participant). The fit of our emerging study findings with multidisciplinary literatures on health risk, breast cancer, alcohol consumption and the gendered life course was iteratively considered by all authors to refine analysis and interpretation. Our approach layered inferential processes (Meyer & Lunnay, Citation2013) including: (1) inductive analysis of women’s breast cancer perceptions and alcohol consumption (in-time); (2) deductive analysis of change in these topics (over time) as the pandemic unfolded; (3) retroductive theorisation of how/why/in what instances alcohol and breast cancer feature on participants’ risk horizons; and (4) abductive theorisation of how participants’ risk horizons and their internal components (such as competing risks) are built up of various time-framings including ideas about the future, which shifted pre- and during-pandemic. These processes are displayed in .

Responsive research designs are highly valuable in qualitative research (Popay et al., Citation1998), allowing insight gained during data analysis to inform ongoing data collection and interpretation. Our progressive semi-structured interviewing technique enabled exploration of emergent understandings stemming from the changing COVID-19 context (i.e. case numbers, pressers, level of restrictions). Focussing our interpretive lens on how risk practices are situated (Moore, Citation2019) and develop over time (Saldaña, Citation2003) enabled us to theoretically examine how the concept of a risk horizon (Warin et al., Citation2015) has conceptual utility for unpacking complex interweavings of the past, present and future in the time-framings of health risk (Brown, Citation2020). We were able to observe in our data framings of risk at different points in the life course and shifts in these per external contingencies like the pandemic and generational social norms shaping alcohol consumption. Our work cannot, however, be understood as representative of a wider population although saturation can be reached at small numbers (Hennink et al., Citation2016). The data we collected regarding changes in drinking practices were based on self-reports because we were focussed on risk perceptions, rather than quantitave measure of change following standardised procedures.

Findings

Below we present our data analysis organised by themes: the first section illuminates the position of Breast cancer and the risk horizons of pre-midlife women. Here we predominantly focus on data from the first set of interviews (pre-pandemic). Where data in the first section is not collected from the pre-pandemic interviews this is identified. The second section Co-existing risks of not drinking explores the plethora of risks women described that patterned their decisions about drinking alcohol, including how and where health featured (or did not). In the third and final section Pandemic horizons and temporalities of alcohol and (health) risk we collate evidence of women’s changed perceptions of time, the future, and risk horizons captured through their epiphanies including stark and important instances where they experienced a change in their perceptions of risk (Saldaña, Citation2003), as conveyed in interview rounds #2–4. Throughout, we use pseudonyms for anonymity.

Breast cancer and the risk horizons of pre-midlife women

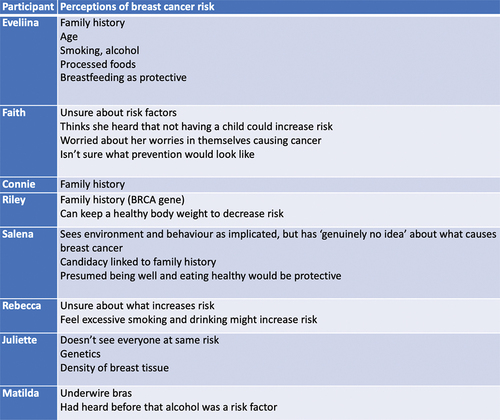

Our interviewees did not consider pre-midlife (ages 25–44) as ‘risky’ for long-term disease such as breast cancer – it was not part of their risk horizon. Rather, the potential for this health misfortune was described as a concern that belonged to a future period of the life course (midlife); perhaps, also influenced by their perceptions that breast cancer was a ‘game of fortune’ rather than amenable to preventive action (see ). Although Faith (#1), age 32, recognised she was ‘getting older’ and had done the bowel screening (sent at age 50 in Australia), she had not had a mammogram or thought about breast cancer because, as she explained:

it sounds horrible but I’m not at the age range where I should be worrying too much. (Faith, #1)

Rebecca identified that ‘feeling healthy’ made breast cancer feel ‘a bit abstract’, suggesting that perceived health in the present can influence women’s perception of their distance from risk and the relativity of breast cancer potential on their horizon risks (#2). Eveliina relayed the relationship between her age and health as shortening her risk horizon:

… when you’re younger you can do things to your body or neglect it, and you bounce back. But I’m starting to be in that age where all the wear and tear and things is starting to show. (#1)

Despite feeling like her ‘age’ was starting to show and therefore needing to pay attention to her health, she did not consider breast cancer to be on her risk horizon:

I still fall short of the age bracket where that messaging starts to be so loud that you can’t ignore … (Eveliina, #1)

Salena described being able to shelve cancer risk from her immediate future because she considered it something for ‘older people’:

Like many things that are scary, I just try and not think about it. (#1)

She acknowledged the serious risk of breast cancer, but her attitude to self-examining her breasts (as well as pap smears) demonstrated a distance from that risk:

‘you know that you should, but … ’. (#1)

Although there was a tacit assumption breast cancer risk would be more salient during midlife, other more immediate risks made it difficult for Eveliina to keep health on the horizon:

As women we’re really good at looking after other people or people we love, make a lot of effort … why don’t we look after ourselves the same way? (#1)

Connie conveyed an over-cluttered risk horizon – there were too many risks to respond to (elevating stress), so she described a need to demote or disregard some risks so that there was less clutter and she didn’t feel she was going to go ‘insane’:

I try to minimise every risk and I stress myself out a lot over it … But then everything conflicts with each other these days as well I find. So I think you just find what works best for you and try to do that otherwise I’ll go insane. (#1)

Faith (#3) echoed this idea – that when there is so much risk-thinking to do about health in the present, it becomes too difficult for women to know which health risks are reasonable for concern, resulting in Faith using self-talk to ‘calm down’ about all health risks, so that risk didn’t dominate daily life:

… sometimes I do think to get myself checked but then I think about how about I just get myself checked for every cancer that is out there, you know what I mean. It’s one of those things, I could have this, I could have that … I can’t get checked for everything to make sure I don’t have anything.

Breast cancer was positioned as far away in women’s risk horizons – as only a potential concern. In the present, short-term benefits of alcohol were described by seven of the eight women we spoke with (noting Matildahad been sober for 11 years) and we consider these in the following section.

Co-existing risks of not drinking in the present

Women were aware of the multiple risks of drinking but also of not drinking. They situated risks in the present, informed by their imaginings about the future and momentum of the past, and these commonly sat in tension with each other. For Riley, alcohol was a ‘quick’ way to get ‘pleasure’ or a ‘buzz’ amidst her feelings of working ‘hard’ at parenting (#1). Faith described ‘ritual’ drinking as a way of ‘soothing’ her problems, ‘taking the edge off’ and letting the day ‘fade away’. (#1) Drinking wine was ‘her little treat to have for such a hard day’s work’ when watching TV once the kids were in bed to ‘calm’ down and stop her being so ‘uptight’:

At the end of the day, when you’ve just been through everything that you go through with a 3 and a 5 year old that at the end of the day is, yeah, it kind of just … takes the edge off mummy. You know, you’re not so bossy and cranky. (during-pandemic, #4)

Further, Faith felt alcohol helped her to ‘glimpse … at who I used to be before I had a kid’ (#2); but also that it was ‘bad for you’ and that ‘I do hope one day I will cut it out’ because ‘I don’t feel I’m at a healthy stage with drinking’. The benefits that alcohol brought in terms of stopping her from being a ‘bitch to everyone in the house’ meant she overlooked the potential negatives of alcohol to health. Eveliina articulated a similar ‘trade-off’ between the ‘buzz’ of alcohol and the next day being a ‘write-off’, feeling that as she had gotten older ‘it goes more towards the not nice buzz’ (#2).

Juliette perceived that her mothers’ generation drank to ‘fix’ everything and that her friends ‘started to turn to alcohol’ to ‘drink their problems away’ (#1); but also that alcohol helped her feel ‘relaxed’ and ‘like an adult’ when out to dinner with friends, or have a ‘lightened’ and ‘buzz vibe’ when drinking at home (#2). She also reported drinking orange whisky when she got a sore throat on her grandmothers’ advice (#2) and identified relational conflict was a risk to not drinking, especially with her husband’s family where she accepted wine even though she didn’t want to drink because it made it easier for her husband to refuse it, in light of his attempts to manage his alcohol-dependence:

I’ve just gone, screw it, I’ll just drink the one drink. It’s fine. It’s easier than arguing. (#3)

Salena drank to both ‘let go’ and ‘be in control’ as well as socialise – saying that alcohol was a form of mental health ‘self-care’ albeit ‘harmful’ to physical health, particularly in the context of her experiences with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and situational depression (#1). Connie described herself as ‘more of a binge drinker’ and rationalised its value as making ‘things more interesting’:

I drink to have a good time … If there’s an occasion, I like to let my hair down and lose the inhibitions a bit, I guess. I’m constantly thinking … trying to do something and hold everything together. It’s nice to have a bit of a break from that. (#1)

Risks associated with not drinking therefore took up space in the risk horizons for women we interviewed as it threatened the loss of something valuable in multiple domains: release from responsibility, anxiety and stress (letting go), reward for hard work, a way to relax in the home setting, to have a good time, feel calm, perform identity-work or practice self-care. These risks tended to coalesce within relatively short-term time-framings.

Rather than health being absent, it was arranged in a calibrated hierarchy of co-existing priorities; and women described ways in which they worked to decrease the health ‘riskiness’ of their drinking. Eveliina tried spirits like gin because they were ‘cleaner’ (#2); Juliette tried to only drink enough so that she felt ‘light’ but not enough to get a hangover (#2) and less again if she was already unwell or in pain because it ‘won’t help’ the situation (#3). Riley avoided drinking two nights in a row to stave off migraines (#1), and Rebecca felt that headaches were a key reason to drink less, in part because they symbolised remorse and an association with her mother who ‘drinks too much’ in ways considered socially unacceptable (#1). The negative impacts of alcohol were more clearly visible in a shorter future. Keeping the longer-term health risks like breast cancer in view was difficult, perhaps linked with the banal social acceptability of consuming alcohol in Australia, as Salena notes:

We know that alcohol is a carcinogen, but it’s so much more socially acceptable [than smoking]. I don’t – every time I drink alcohol I do not think of it as a carcinogen. (#1)

Connie needed certainty that stopping drinking would ‘make an impact’ to breast cancer risk; Faith would only stop for a ‘serious reason’ like if she knew ‘categorically’ that it increased breast cancer risk because ‘of what it helps me with I suppose’ (#1); Juliette wanted to know at what ‘level’ and ‘over what timeframe’ alcohol actually increased breast cancer risk before she changed anything (#1). Salena identified a tipping point at which she might reorganise the position/s of breast cancer and alcohol on her risk horizon:

If [the risk of breast cancer] was probably going to be more than 25%, then yeah, I would definitely think about cutting down my alcohol consumption.

Several co-existing risks therefore surrounded (not) drinking for the women we interviewed, within relatively short-term futures. We turn now to explore how women’s alcohol-related risk for breast cancer fundamentally changed through the pandemic, destabilising assumptions about the future, and about time itself.

Pandemic horizons and temporalities of alcohol and (health) risk

Women’s daily lives changed significantly during the pandemic. Some women were able to do their paid work from home, while others took leave from paid work, or were made redundant. The increased gendered labour for many women during this time has been well-documented (Craig & Churchill, Citation2021; Wood et al., Citation2021), and impacted all women in this study. Health and community services, playgrounds and playgroups closed (interview round #2); then re-opened (interview round #3) and closed again during another 5-day lockdown (interview round #4); disrupting daily and weekly routines as well as future planning. The feeling of a suspended future and a protracted present resonated through interviews conducted during the pandemic, giving an emotional tone of uncertainty where everything was ‘subject to change’ and ‘you can’t take anything for granted’ (Riley, #3); as well as a pragmatic experience that:

… everywhere we go … you just go with what the new rules are, and you wait to hear what the next step is. (Faith, #4)

Eveliina doubted that ‘going back to normal’ would happen and reflected on learning about ‘how precarious things are’ (#4). The valuable roles of alcohol enlarged at the same time as her certainty in the future dissolved. Pre-pandemic she reported going through phases of not drinking at all, with most alcohol consumption happening outside of her home, and feeling alcohol had ‘low utility’ to reduce stress at home (#1); yet soon after the pandemic emerged she conveyed drinking regularly at home not only because she could not go out but because it helped to ‘break the routine’ (#2). Prior to our third interview she was diagnosed with sleep apnoea, which shifted the balance as to whether drinking was ‘worth it’ and, accordingly, she had not drunk much for a while (#3). However during our last interview, she described consumption patterns that had increased since before the pandemic, seemingly tethered to a ‘why not’ attitude, where alcohol had become:

Almost … ritual as well, like, ‘Okay, now we’re having a drink. It’s the weekend or it’s, you know, the workday is over’ … [it’s] very important for us to mark that time because with work it’s kind of just spills out of office hours and it’s like there’s always more work to be done. (#4)

Connie had also found herself drinking larger quantities of alcohol during the pandemic, trying different drink types (pink gin) ‘just for something to do’ and because she saw alcohol as ‘a boredom killer’ (#2). She described avoiding thinking about breast cancer risk and ‘negative things in general … because COVID-19 has been in the spotlight’ (#3) – filling her risk horizon. It seemed she had to bring her risk horizon closer, to only be thinking in the ‘short-term’ because ‘the idea of long-term risks is a bit overwhelming’ (#4), consistent with a philosophy she communicated with us in our first interview where she explained she did not want the fear of illness to control her life (#1). Yet, when restrictions lifted and Connie was getting out of the house again, she had ‘not really felt the need’ to ‘just drink for the sake of having a drink’ and also that ‘[drinking’s] not all it’s cracked up to be … so I just stopped’ (#3). The short-term negative impacts of drinking were key risks to continuing drinking, but she felt another substance could help to relieve stress:

I’ll end up vomiting or the next day, I’ve got a hangover and a headache … [whereas with marijuana] I like the fact that I can just get it over and done with and then relax … I’m just relaxed and want to eat. (#4)

Salena moved to Dhaka just before the pandemic (between interviews #1-#2) with strict border controls prevented her from returning to Australia. She found herself trying to ‘hang on’ to ‘activities that create[d] meaning and normalcy’ while missing home (#2). These priorities were closer on her horizon than her concern about SARS-COV-2:

I’m young and relatively healthy and I have no real comorbidities. I’m female… if I do get it, I’ll probably be fine. (#2)

Salena described her social wine or beer consumption pre-pandemic as a ‘reward on a Friday night’ (#1) shifted to drinking Pepsi and whisky ritually most evenings to ‘chill out’ or ‘numb’ (#2) and give reprieve from boredom and work stress during (Dhaka) lockdowns. She felt life’s uncertainty would ‘be easier tonight if I have a drink’, and make her ‘feel better right now’ (#2) which illustrates the short-term nature of gains from drinking alcohol. As the rhythms of her work-at-home days developed, Salena reflected on having to ‘delay’ drinking while ‘waiting’ for the end of her day to begin (#3), which alcohol helped to achieve:

… feel comforted … end my day … [give] permission to allow myself to not work anymore … I think it’s just like that signal for now is the time when I don’t have to think, and [can] just be, and enjoy myself. (#3)

Salena described being more likely to drink larger amounts of alcohol and ‘not worry’ about long-term health risks in the COVID-19 context – actively shutting them out – including breast cancer:

I genuinely haven’t even thought about it … it’s like just one more thing that I don’t want to think about. (#3)

The de-prioritisation of breast cancer as a long-term risk of alcohol held even when she saw information on her Instagram feed alcohol consumption having a tri-fold impact on breast cancer risk – quipping:

I was like ‘probably should think about that’ but haven’t. (#4)

The risks Salena did see from drinking alcohol in the pandemic context were the ‘heightened’ level and rush of ‘baseline emotional responses’. These risks were framed in terms of mental health, where ‘drinking a lot of alcohol could very easily pop me in a spot where I’m like, feeling really emotional’ (#4). While she recognised she might need to ‘shift’ out of relying on drinking more, she also recognised the ‘constant changes’ to daily life meant ‘you just recalibrate what risk is and what’s normal’, including what ‘amount of risk’ you live with. She conveyed that ‘this year has all been about just getting through another day’ (#4) – suggesting her risk horizon was circumscribed by a very short, almost immediate, future.

Rebecca tried to find a ‘middle ground’ in how concerned she was about the perceived risk/s of the pandemic, because while ‘I’m not overly panicked if we get [the virus]’ still it does ‘creep into my head’ (#2). The prominence of SARS-COV-2 transmission on her risk horizon was demonstrated in keeping her son home from childcare for ‘civic duty’ (#2) and ‘kid-swapping’ with family to avoid kindergarten (#3). In the ‘eerieness’ of an uncertain future, alcohol continued to demarcate weekend time for her early in the pandemic because ‘that’s how you relax, that’s how you define Saturday’ (#2). Yet this remained in tension with her ‘ultra-awareness’ of not becoming ‘too much’ when drinking like she felt her mother was – ‘bordering on alcoholic’ (#2). After restrictions lifted she stopped drinking altogether, because:

I probably had a few drinks at times I wouldn’t normally drink, and I just feel crappy when I drink … (#3)

While initially she was worried about her family pressuring her to drink, she found they did not notice at a family event, when she ‘felt more in control when I wasn’t drinking’ (#3). Rather than breast cancer being a specific health risk on her horizon that motivated her to stop drinking in the present, she was motivated by wanting to have a ‘healthy’ future where she was in control:

If I started going down a worried path of worrying about breast cancer … there’s other stuff to worry about before that. (#3)

Eveliina felt ‘terrified’ about getting SARS-COV-2 because she would ‘get really ill’ (#2), yet breast cancer risk had been pushed further away:

I haven’t had the time, energy and resources [to see my GP]. So something like breast cancer, which is kind of not on my radar, is just definitely not on my radar. (#4)

Riley identified that breast cancer was not really ‘in the mix’ of possible risks (#2) and that while the pandemic ‘makes you think about your health’ (#3), breast cancer ‘hadn’t featured’ (#3) and had stayed ‘distant’ (#4) because of the overwhelming fear of contracting COVID. Her feelings of ‘vulnerability’ to SARS-COV-2 extended from her knowledge that:

people in their 30s and 40s who had no underlying risk factors do get really sick and die from this disease … I’m in my early 40s … for someone of my age it’s not impossible … it’s a heightened sense of your own mortality. (#2)

Rather than experiences of a ‘precarious’ and ‘unpredictable future’ early in the pandemic, which brought Riley’s physical health into view as needing more ‘attention’, as pandemic lockdowns continued she began to prioritise the ‘risk to my mental health’ as being ‘of greater concern’ (#3). Her alcohol consumption changed as she started to drink shandies a few evenings a week in order to relax, using lemonade to make alcohol ‘last longer’ (#4) and lower short-term risks of headaches. Matilda similarly thought of alcohol risks in the short term, stating that she ‘hadn’t thought about’ breast cancer risk (#3) and didn’t feel it was ‘something she should be worrying about’ (#4). She remained sober during the pandemic and described how when ‘everything else stopped’ it actually helped ‘to realise certain things’ she wanted to change in life and enabled her to focus on ‘the now’ rather thinking about the future ‘too much’ (#2). Shortening her risk horizon sharpened her willingness to ‘get my shit together’ (#3). Faith too ‘craved’ the temporal dislocations of pandemic lockdowns because it relieved anxiety around the ‘deadlines’ and ‘pressure’ of parenting that needed ‘one eye always on the clock’ – instead giving her ‘all day every day to be a mum’ (#2). Although she knew ‘younger people can get [SARS-COV-2] and they can die’; she wasn’t ‘really too worried for myself or my husband’ – only her asthmatic two-year-old (#2). She initially felt lockdown put her ‘off drinking because it was quite stressful … a different kind of stress’ than ‘being a mum all day’: it was ‘quite scary’ and a ‘downer’ that removed life’s rhythms:

… it doesn’t even matter that the weekend’s here, because I’m just doing the same thing every day … we can’t treat ourselves … it feels a little bit sad, so you don’t really want to drink … I feel a bit in a rut like there’s nothing to drink for’. (#2)

While she would still ‘have a drink at night just to enjoy it or whatever’ she attempted to have a few alcohol-free nights per week, which ‘is not normal for me, it’s weird’ (#2). Although she described returning to drinking ‘most nights’ as pandemic lockdowns continued, she started gym classes when restrictions eased, finding they helped ‘[get] my identity back since having kids and everything’ (#3) a purpose for which alcohol had previously been important (#2). She described the classes giving her something to look forward to, so she ‘[didn’t] need a drink’ (#3). Her alcohol-free nights were instigated in response to the embodied experiences of drinking, so that alcohol would ‘keep me up at night or make me feel a bit crap the next morning’ (#3). Despite these changes, Faith also described that long-term health risks had ‘completely gone out the window’, because it:

[put] life a bit more back into perspective in that way … made me less worried about my health, only in the way – I only worry about COVID-19. I don’t worry that I have cancer and I’m going to die soon. (#2)

Compounding the perceived value of alcohol in managing a vacuous present, threatened by pandemic-derived boredom and stress, our data suggest that the faintly visible long-term health risks which might stem from alcohol consumption were erased by or occluded for women in our study, as they sought to help manage the immediate present which felt more overwhelming and consumed their attention. The short-term health impacts of alcohol however stayed visible for all of the women we interviewed, with mixed description of how this influenced consumption (except for Matilda who remained sober throughout the pandemic).

Discussion

Our findings illuminate that for women we interviewed, concern about breast cancer was located in a distant ‘future’. Rather than being something that belonged on the risk horizon of pre-midlife (25–44), they saw its relevance within a later period of the lifecourse: when they were no longer ‘too young’ to offset worry about breast cancer. The epiphanies (Saldaña, Citation2003) conveyed to us during the pandemic, display how these risk horizons were recalibrated to nearer futures to block out nascent uncertainties and unknowabilities of longer-futures arising within pandemic instabilities (Graham, Citation2020). While breast cancer risk was faintly glimpsed as part of these longer futures (‘midlife’) before the pandemic (although de-prioritised because it was viewed as relevant for thought and preventive action in later life), during the pandemic these longer-futures were not visible on the risk horizons of women pre-midlife: they were ‘looked past’ (Brown, Citation2020), ‘strategically ignored’ (McGoey, Citation2012) or ‘shuttered out’ (Beck, Citation1992) altogether. While this may have been for some an intentional and reflexive decision, it also showcases how ‘risk continuums’ (Alaszewski, Citation2021) are built from certain time-framings (Brown et al., Citation2013) – where the relative ‘size’ or intensity of the immediate present might occlude gaze to the far futures of breast cancer risk (Lunnay et al., Citation2021) depicted by and imagined within public health risk management strategies (Green & Lynch, Citation2022).

Our data shows that when only shorter-futures stay in view, the risks of (not) drinking alcohol are repositioned within more immediate risk horizons. Notwithstanding the stressors of the pandemic and its countermeasures, the feeling of a protracted present was relayed as beneficial by some women – with everything else at a standstill, they were able to (re)consider their priorities and identities in life, akin to the Project of the Self (Giddens, Citation1991), where individuals seek to bridge their present life towards a future deemed valuable that reflexively minimises risk – as required for responsible neoliberal citizenship. Matilda wanted to ‘get her shit together’ while Rebecca conjured the ‘ultra-awareness’ of her mother becoming ‘too much’ when she drank. Both women link their pasts to risks and futures (Zinn, Citation2005) desired and/or desirable to avoid (Brown, Citation2020). For Rebecca, the risk of becoming ‘too much’ when drinking was located in a very near future (specific drinking occasions) but was also connected to a desire for a longer-term future (and biographical) shift towards non-drinking, which she enacted during the course of the study.

For others, the risks of not drinking crystallised during futures of nearer time-frames. Early in the pandemic, alcohol helped negotiate layered and conflicting material-temporal disruptions brought about by ‘normal’ life abruptly stopping and the additional (gendered) labour(s) this required from women (i.e. Connie making sure her kids did not bother her new partner or Eveliina’s delivering food to her elderly parents). It seemed that this period was experienced as a hysteresis (Graham, Citation2020), with alcohol bringing stability and pleasure in the same way a holiday might (Ward et al., Citation2022). However, as pandemic disruptions lingered, new spaces opened spaces for women to reflect on the various risks to (not) drinking in the present and how alcohol featured in imagined selves cast largely within short time-frames (i.e. surviving the pandemic). This supports assessments that the interruptions of the pandemic initially caused a ‘standstill’ which then progressed to phasic and continuous change (Bröer et al., Citation2021). Negative health impacts of alcohol appeared to be felt in near-term futures (i.e. drinking occasion or next day) while perceived risks of not drinking alcohol spanned days (not having access to calm and relaxation). Connie explained the pandemic made her critical of alcohol’s impact on physical and mental health, so she stopped drinking altogether after increasing her consumption at the beginning of the pandemic (switching instead to marijuana for better stress relief and fewer side effects). Eveliina, Salena and Juliette maintained their consumption increases per recognition of alcohol’s (perceived) value in managing pandemic stressors – which had an unclear endpoint during our final interviews with them in later 2020. Faith was more conscious of her drinking because she now linked it to other activities occurring twice-weekly that resonated with bridging from her biographical present to a projected and desired future, yet nonetheless steeped in her past (going to the gym and ‘getting her identity back since I had kids and everything’).

Our data show how newly-experienced pandemic-temporalities stimulated reflection about the heirarchies of risk of (not) drinking alcohol, which were reflexively recalibrated by women using awareness of alcohol within their pandemic present and immediately-anticipated futures. Pitching information about alcohol health risks within shorter risk horizons (Foster & Heyman, Citation2013; Warin et al., Citation2015) – like over a week or a month – might make these risks more ‘thinkable’ for women in midlife (Dean, Citation1999) as a precursor to becoming more actionable. This will help to account for the way in which breast cancer drifts further away on women’s risk horizons (Lunnay et al., Citation2021) and also for the fact that some women will not see themselves as a candidate for breast cancer anyway (Batchelor et al., Citation2023). Our data further suggest that desired futures were more motivating than ones to be avoided because of health risks (Brown, Citation2020). It would seem that these nearer futures feel more ‘real’ for individuals (Green & Lynch, Citation2022). Explicitly inviting reflexivity around alcohol’s place in identity-work within a near-term biographical future that balances health and risk (Zinn, Citation2005), may help both the negative and positive benefits of alcohol stay visible on the risk horizon of women pre-midlife.

Conclusion

Our analysis suggests that making alcohol-related breast cancer risk ‘thinkable’ for women pre-midlife requires complex considerations of the competing temporalities and time-framings of risk which compete for attention during women’s pre-midlife – and in which long-term health might not be the ultimate value (Crawford, Citation1984). This is prescient given post-pandemic shifts in Australia’s healthy living guidelines (2023) which explicitly outline there is ‘no safe level’ of alcohol consumption for anyone at any time (Department of Health, Citation2023) – which may have little bearing in the material space of women’s lives that pattern their daily realities and render futures of varying lengths (Warin et al., Citation2015). Public health policy and approaches that are open to and reflective of these realities and subjective futures are urgently needed to manage alcohol-related risk, such as intervening at structural levels (such as alcohol availability and marketing) rather than at the level of individuals (risk messaging) and we advocate for this approach. Our work illustrates the value of using the concept of a ‘risk horizon’ to explore the reflexive work required to engage with the various time-framings of health risk and how these are enfolded within imaginings of the future, experiences and temporalities of the present (Bröer et al., Citation2021); as well as the epiphanies described during research which link participants pasts’ (Saldaña, Citation2003) to changes in (health) risk-thinking and reflection.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Dr Margaret Becker for undertaking the interviews, and for the women who participated in several interviews with us during a tumultuous year.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agabio, R., Madeddu, C., Contu, P., Cosentino, S., Deiana, M., Massa, E. … Sinclair, J. (2021). Alcohol consumption is a modifiable risk factor for breast cancer: Are women aware of this relationship? Alcohol and Alcoholism, 57(5), 533–539. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agab042

- Alaszewski, A. (2021). Plus ça change? The COVID-19 pandemic as continuity and change as reflected through risk theory. Health, Risk & Society, 23(7–8), 289–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698575.2021.2016656

- Baker, S. (2017). Patterns and perceptions of maternal alcohol use among women with pre-school aged children: A qualitative exploration of focus group data. Journal of Addiction Research & Therapy, 8(5), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-6105.1000347

- Batchelor, S., Lunnay, B., Macdonald, S., & Ward, P. R. (2023). Extending the sociology of candidacy: Bourdieu’s relational social class and mid‐life women’s perceptions of alcohol‐related breast cancer risk. Sociology of Health & Illness, 45(7), 1502–1522. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.13644

- Beck, U. (1992). Risk society: Towards a new modernity. University of Munich.

- Blue, S., Shove, E., Carmona, C., & Kelly, M. P. (2014). Theories of practice and public health: Understanding (un)healthy practices. Critical Public Health, 26(1), 36–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2014.980396

- Bröer, C., Veltkamp, G., Bouw, C., Vlaar, N., Borst, F., & de Sauvage Nolting, R. (2021). From danger to uncertainty: Changing health care practices, everyday experiences, and temporalities in dealing with COVID-19 policies in the Netherlands. Qualitative Health Research, 31(9), 1751–1763. https://doi.org/10.1177/10497323211005748

- Brown, P. (2020). Studying COVID-19 in light of critical approaches to risk and uncertainty: Research pathways, conceptual tools, and some magic from Mary Douglas. Health, Risk & Society, 22(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698575.2020.1745508

- Brown, P., Heyman, B., & Alaszewski, A. (2013). Time-framing and health risks. Health, Risk & Society, 15(6–07), 479–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698575.2013.846303

- Carcel, C., Haupt, S., Arnott, C., Yap, M. L., Henry, A., Hirst, J. E., Woodward, M., & Norton, R. (2024). A life-course approach to tackling noncommunicable diseases in women. Nature Medicine, 30(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02738-1

- Cook, M., Dwyer, R., Kuntsche, S., Callinan, S., & Pennay, A. (2021). ‘I’m not managing it; it’s managing me’: A qualitative investigation of Australian parents’ and carers’ alcohol consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic. Drugs: Education, Prevention & Policy, 29(3), 308–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2021.1950125

- Cook, M., Pennay, A., MacLean, S., Dwyer, R., Mugavin, J., & Callinan, S. (2022). Parents’ management of alcohol in the context of discourses of ‘competent’ parenting: A qualitative analysis. Sociology of Health & Illness, 44(6), 1009–1026. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.13475

- Craig, L., & Churchill, B. (2021). Working and caring at home: Gender differences in the effects of COVID-19 on paid and unpaid labor in Australia. Feminist Economics, 27(1–2), 310–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2020.1831039

- Crawford, R. (1984). A cultural account of “health”: Control, release, and the social body. In J. McKinlay (Ed.) Issues in the political economy of health care (pp. 60–104). Routledge.

- Crawford, R. (2004). Risk ritual and the management of control and anxiety in medical culture. Health, 8(4), 505–528.

- Dare, J., Wilkinson, C., Traumer, L., Kusk, K. H., McDermott, M. L., Uridge, L., & Grønkjær, M. (2020). “Women of my age tend to drink”: The social construction of alcohol use by Australian and Danish women aged 50–70 years. Sociology of Health & Illness, 42(1), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12991

- Dean, M. (1999). Risk, calculable and incalculable. In Lupton, D. (Ed.), Risk and sociocultural theory (pp. 131–159). UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Department of Health. (2023) How much alcohol is safe to drink? Australian Government. Retrieved September 21st, 2023, from https://www.health.gov.au/topics/alcohol/about-alcohol/how-much-alcohol-is-safe-to-drink

- Donat-Vargas, C., Guerrero-Zotano, Á., Casas, A., Baena-Cañada, J. M., Lope, V., Antolín, S., … Pollán, M. (2021). Trajectories of alcohol consumption during life and the risk of developing breast cancer. British Journal of Cancer, 125(8), 1168–1176. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-021-01492-w

- Douglas, M. (1992). Risk and blame: Essays in cultural theory. Routledge.

- Emslie, C., Hunt, K., & Lyons, A. (2015). Transformation and time-out: The role of alcohol in identity construction among Scottish women in early midlife. International Journal of Drug Policy, 26(5), 437–445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.12.006

- Foley, K. M., Warin, M., Meyer, S. B., Miller, E. R., & Ward, P. R. (2021). Alcohol and flourishing for Australian women in midlife: A qualitative study of negotiating (un) happiness. Sociology, 55(4), 751–767. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038520973580

- Foster, J., & Heyman, B. (2013). Drinking alcohol at home and in public places and the time framing of risks. Health, Risk & Society, 15(6–07), 511–524. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698575.2013.839779

- Giddens, A. (1991). The constitution of modernity. Stanford University Press.

- Graham, H. (2020). Hysteresis and the sociological perspective in a time of crisis. Acta Sociologica, 63(4), 450–452. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699320961814

- Green, J., & Lynch, R. (2022). Rethinking chronicity: Public health and the problem of temporality. Critical Public Health, 32(4), 433–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2022.2101432

- Haydon, H., Obst, P., & Lewis, I. (2016). Beliefs underlying women’s intentions to consume alcohol. BMC Women’s Health, 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-016-0317-3

- Hennink, M. M., Kaiser, B. N., & Marconi, V. C. (2016). Code saturation versus meaning saturation: How many interviews are enough? Qualitative Health Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316665344

- Heyes, C. J. (2020). Anaesthetics of existence: Essays on experience at the edge. Duke University Press.

- Holman, E. A., Jones, N. M., Garfin, D. R., & Silver, R. C. (2023). Distortions in time perception during collective trauma: Insights from a national longitudinal study during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, & Policy, 15(5), 800. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0001326

- Jackson, K., Finch, T., Kaner, E., & McLaughlin, J. (2018). Understanding alcohol as an element of ‘care practices’ in adult white British women’s everyday personal relationships: A qualitative study. BMC Women’s Health, 18(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-018-0629-6

- Johnson, S. (2022). Women deserve better: A discussion on COVID‐19 and the gendered organization in the new economy. Gender, Work & Organization, 29(2), 639–649. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12785

- Keane, H. (2023). The drinking at home woman: Between alcohol harms and domestic experiments. The Sociological Review, 71(4), 801–816.

- Kersey, K., Hutton, F., & Lyons, A. C. (2023). Women, alcohol consumption and health promotion: The value of a critical realist approach. Health Promotion International, 38(1), daac177. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daac177

- Kippen, R., James, E., Ward, B., Buykx, P., Shamsullah, A., Watson, W., & Chapman, K. (2017). Identification of cancer risk and associated behaviour: Implications for social marketing campaigns for cancer prevention. BMC Cancer, 17(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-017-3540-x

- Lang, A. Y., Harrison, C. L., Barrett, G., Hall, J. A., Moran, L. J., & Boyle, J. A. (2021). Opportunities for enhancing pregnancy planning and preconception health behaviours of Australian women. Women & Birth, 34(2), e153–e161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2020.02.022

- Lee, E., Bristow, J., Arkell, R., & Murphy, C. (2022). Beyond ‘the choice to drink’in a UK guideline on FASD: The precautionary principle, pregnancy surveillance, and the managed woman. Health, Risk & Society, 24(1–2), 17–35.

- Leggat, G., Livingston, M., Kuntsche, S., & Callinan, S. (2022). Alcohol consumption trajectories over the Australian life course. Addiction, 117(7), 1931–1939. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15849

- Lunnay, B., Foley, K., Meyer, S. B., Warin, M., Wilson, C., Olver, I., Miller, E. R., Thomas, J., & Ward, P. R. (2021). Alcohol consumption and perceptions of health risks during COVID-19: A qualitative study of middle-aged women in South Australia. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 616870. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.616870

- Lunnay, B., Warin, M., Foley, K., & Ward, P. R. (2023). Is happiness a fantasy only for the privileged? Exploring women’s classed chances of being happy through alcohol consumption during COVID-19. In Ward, P., & Foley, K. (Eds.), The emerald handbook of the sociology of emotions for a post-pandemic world (pp. 113–133). Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Lupton, D. (1999). Risk and sociocultural theory. Cambridge University Press.

- MacLean, S., Room, R., Cook, M., Mugavin, J., & Callinan, S. (2022). Affordances of home drinking in accounts from light and heavy drinkers. Social Science & Medicine, 296, 114712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114712

- Magnus, M. C., Hockey, R. L., Håberg, S. E., & Mishra, G. D. (2022). Pre-pregnancy lifestyle characteristics and risk of miscarriage: The Australian longitudinal study on women’s health. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 22(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-04482-9

- McGoey, L. (2012). The logic of strategic ignorance. The British Journal of Sociology, 63(3), 533–576. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2012.01424.x

- Meyer, S. B., Foley, K., Olver, I., Ward, P. R., McNaughton, D., Mwanri, L., Miller, E. R., & Haighton, C. (2019). Alcohol and breast cancer risk: Middle-aged women’s logic and recommendations for reducing consumption in Australia. Public Library of Science ONE, 14(2), e0211293. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0211293

- Meyer, S. B., & Lunnay, B. (2013). The application of abductive and retroductive inference for the design and analysis of theory-driven sociological research. Sociological Research Online, 18(1), 86–96. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.2819

- Moore, S. (2019). Risk rituals and the female life-course: Negotiating uncertainty in the transitions to womanhood and motherhood. Health, Risk & Society, 22(1), 15–30. CHRS-2018-0101.R3.

- Popay, J., Rogers, A., & Williams, G. (1998). Rationale and standards for the systematic review of qualitative literature in health services research. Qualitative Health Research, 8(3), 341–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973239800800305

- Poulsen, M. (2015). Embodied subjectivities: Bodily subjectivity and changing boundaries in post-human alcohol practices. Contemporary Drug Problems, 42(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091450915569499

- Saldaña, J. (2003). Dramatizing data: A primer. Qualitative Inquiry, 9(2), 218–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800402250932

- Sarich, P., Canfell, K., Egger, S., Banks, E., Grace, J., Grogan, P., & Weber, M. (2020). Alcohol consumption, drinking patterns and cancer incidence in an Australian cohort of 226,162 participants aged 45 years and over. British Journal of Cancer, 124(2), 513–523. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-020-01101-2

- Vicario, S., Peacock, M., Buykx, P., Meier, P., & Bissell, P. (2021). Negotiating identities of ‘responsible drinking’: Exploring accounts of alcohol consumption of working mothers in their early parenting period. Sociology of Health and Illness, 43(6), 1454–1470. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.13318

- Ward, P. R., Foley, K., Meyer, S. B., Thomas, J., Huppatz, E., Olver, I., , and Lunnay, B. (2022). Uncertainty, fear and control during COVID-19 … or … making a safe boat to survive rough seas: The lived experience of women in South Australia during early COVID-19 lockdowns. In Brown, P. R., & Zinn, J. O. (Eds.), Covid-19 and the sociology of risk and uncertainty: Studies of social phenomena and social theory across 6 continents (pp. 167–190). Springer International Publishing.

- Warin, M., Zivkovic, T., Moore, V., Ward, P. R., & Jones, M. (2015). Short horizons and obesity futures: Disjunctures between public health interventions and everyday temporalities. Social Science & Medicine, 128, 309–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.01.026

- Wood, D., Griffiths, K., & Crowley, T. (2021). Women’s work: The impact of the COVID crisis on Australian women. Grattan Institute. Retrieved February 5th, 2024, from https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2021-03/apo-nid311282.pdf

- Zinn, J. (2005). The biographical approach: A better way to understand behaviour in health and illness. Health, Risk & Society, 7(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698570500042348