Abstract

The persistence of extreme suicide disparities in American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) youth signals a severe health inequity with distinct associations to a colonial experience of historical and on-going cultural, social, economic, and political oppression. To address this complex issue, we describe three AI/AN suicide prevention efforts that illustrate how strengths-based community interventions across the prevention spectrum can buffer suicide risk factors associated with structural racism. Developed and implemented in collaboration with tribal partners using participatory methods, the strategies include universal, selective, and indicated prevention elements. Their aim is to enhance systems within communities, institutions, and families by emphasizing supportive relationships, cultural values and practices, and community priorities and preferences. These efforts deploy collaborative, local approaches, that center on the importance of tribal sovereignty and self-determination, disrupting the unequal power distribution inherent in mainstream approaches to suicide prevention. The examples emphasize the centrality of Indigenous intellectual traditions in the co-creation of healthy developmental pathways for AI/AN young people. A central component across all three programs is a deep commitment to an interdependent or collective orientation, in contrast to an individual-based mental health suicide prevention model. This commitment offers novel directions for the entire field of suicide prevention and responds to calls for multilevel, community-driven public health strategies to address the complexity of suicide. Although our focus is on the social determinants of health in AI/AN communities, strategies to address the structural violence of racism as a risk factor in suicide have broad implications for all suicide prevention programming.

HIGHLIGHTS SECTION

Structural violence of racism and colonization are social determinants of suicide.

Collaborative and power-sharing implementation strategies can disrupt oppression.

Strengths-based collectivist strategies can buffer structural suicide risk.

Suicide is a leading cause of death for young people ages 10 through 24 in the United States, and suicide rates are increasing disproportionately for young people ages 10 to 14 (Centers for Disease Control, Citation2020). Young people with diverse sexual orientations and gender expressions (Johns et al., Citation2020; Xiao & Lindsey, Citation2021) and who are from diverse racial and ethnic groups are most at risk (Ramchand, Gordon, & Pearson, Citation2021; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Citation2022). These epidemiological patterns signal collective contributing risk among marginalized groups, yet most youth suicide prevention efforts in the U.S. are crisis-oriented, focusing on identifying and linking suicidal individuals to services (Pitman & Caine, Citation2012; Burnette et al., Citation2015; Rubin, Citation2021). This emphasis ignores the structural violence at play, and overlooks barriers that may make mental health resources unavailable or ill-fitting for youth who identify with diverse racial and ethnic groups and sexual orientations (Wexler & Gone, Citation2012; David-Ferdon et al., Citation2016; Sheftall et al., Citation2022). For American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) youth, an individually-focused orientation ignores and perpetuates the fundamental harms of colonization and structural racism that affect health and wellbeing (Elliott‐Groves, Citation2018; Figley & Burnette, Citation2017; Bell et al, Citation2021; Burns et al., Citation2021). Individual-level approaches to suicide prevention alone can further obscure the existing systemic policies and practices, including structural racism, that marginalize some communities and the young people within them (Alvarez, e. al., Citation2022).

The link between marginalization and suicide is also reflected in global suicide trends among historically and institutionally oppressed peoples (Milner, McClure, & De Leo, Citation2012), indicating the importance of structural violence to self-harm and the contribution historical and ongoing oppression and discrimination has in youth suicidality (Brooks, Hong, Cheref, & Walker, Citation2020; Elliott‐Groves, Citation2018; Standley & Foster‐Fishman, Citation2021; McDermott, Hughes, & Rawlings, Citation2018; Wyman Battalen et al., Citation2020; Opara et al., Citation2020; Madubata, Spivey, Alvarez, Neblett, & Prinstein, Citation2021; Martínez-Alés, Jiang, Keyes, & Gradus, Citation2021). To impact suicide rates, suicide prevention efforts must acknowledge and address these key structural contributors (Alvarez, e. al., Citation2022; Marshall, Citation2016; Robinson et al., Citation2018; Brann, Baker, Smith-Millman, Watt, & DiOrio, Citation2021).

UNDERSTANDING AI/AN SUICIDE RISK ACROSS TIME AND INTERSECTING ECOLOGICAL LEVELS

Suicide among AI/AN young people is driven by factors that intersect time and socio-ecological levels. European invasion of what is now called the United States decimated many AI/AN communities through disease and warfare (Brave Heart & DeBruyn, Citation1998; Dunbar-Ortiz, Citation2014). Colonial policies of erasure and removal (e.g., Indian Removal Act of 1830; Indian Relocation Act of 1956; bans on AI/AN religious and spiritual practices until the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978) enacted physical and cultural genocide among many, if not all, AI/AN communities. The impact of colonization continues to pervade Indigenous contemporary experience (Evans-Campbell, Citation2008). Structural violence has been linked to AI/AN suicide for decades (e.g., Barker, Citation2021; Evans-Campbell, Citation2008; Duran, Duran, Heart, & Horse-Davis, Citation1998), yet often the research locates suicide as an individual mental health and Indigenous “problem” (Ansloos & Peltier Citation2022; Ansloos, Citation2018).

An individual-level response to suicide ignores the clear epidemiological patterns that reflect differences based on racial/ethnic identity, age, geography, and/or political context. This orientation is foundationally informed by Western epistemologies that decontextualize issues under study, and conceptualize individuals apart from their family, communities, and connections. Such an orientation centers on Western understandings, and thus systematically diminishes AI/AN knowledges and meanings of the world as exotic, marginal, inferior, or non-existent (Deloria, Citation1997; Smith, Citation2021; Borell, Citation2017). AI/AN communities and critical scholars discern that Western conceptualizations and approaches to suicide prevention are not working because their mechanisms and underlying logics spring from colonial and imperial ideals—the very source of historical trauma and on-going oppression (Reid, Cormack, & Paine, Citation2019). AI/AN communities are demanding that prevention programming look beyond individual risk, consider how structural harms contribute to suicide, and uplift community strengths as central to supporting people’s reasons for life (Barker, Goodman, & DeBeck, Citation2017; Rasmus, Trickett, Charles, John, & Allen, Citation2019; Bryant et al., Citation2021).

PRIORITIZING COMMUNITY AND CULTURAL STRENGTHS

For AI/AN people, Indigenous intellectual traditions, including cultural teachings and practices, are the heart of individual, family, and community wellness (Allen, Wexler, & Rasmus, Citation2021; Barker, Citation2017). Suicide scholars have identified the adverse impact of forced social, cultural, and economic change on AI/AN community health and wellbeing (Elliott‐Groves, Citation2018; Walls, Hautala, & Hurley, Citation2014; Wexler, Citation2009). This perspective acknowledges colonial and imperial ideals of domination and extraction as underlying causes of AI/AN suicide, and recognizes that healing and human development takes place within the context of social and cultural relations. By centering on Indigenous theories and practices, scholars and practitioners can participate in the co-creation of suicide prevention programs that are, at once, local, sustainable, and ethical. In this way, suicide prevention necessarily unsettles societal structures that center on and privilege the dominant culture (Delgado & Stefancic, Citation2001). This shift orients toward strengthening social relationships, collective practices, and cultural identities as mechanisms for reducing risk for suicide among AI/AN young people (Bryant et al., Citation2021). Thus, suicide prevention strategies for Indigenous youth must recognize and prioritize community and cultural strengths, including community relationships and cultural practices. In this way, suicide prevention strategies can offer understandings and tools to navigate and resist unfair and burdensome circumstances, while elevating cultural strengths for healing and transformation (Fitzgerald, Johnson, Allen, Villarruel, & Qin, Citation2021). This redefinition of the suicide prevention goals from exclusively preventing a tragic outcome to also promoting health and wellbeing widens the aperture of suicide prevention to include a continuum of strengths-based movements that enhance (and measure) protective factors, support, and cultural and intergenerational learning. Such approaches push against the status quo of medicalized approaches to suicide, thereby offering innovative and practical strategies for suicide prevention, not just Indigenous communities, but for all peoples. In addition, such an approach shows promise for other historically marginalized communities suffering increasing rates of youth suicide (Center for American Indian Health, Citation2021).

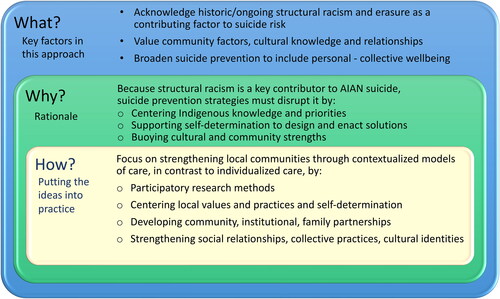

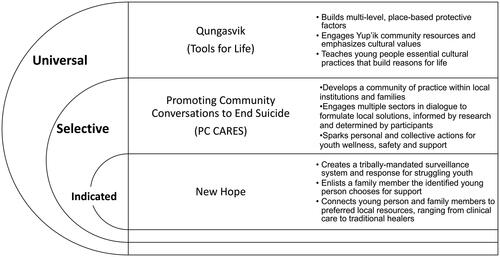

By seeking to understand and make visible the underlying causes of mental health despair in relation to colonial domination and extraction, prevention researchers can play a key role in co-creating and co-developing strategies that are guided and informed by Indigenous knowledges and values that have informed generational approaches to healing and helping. We profile three long-standing participatory research partnerships with Indigenous communities where suicide prevention efforts both acknowledge harms caused by structural violence, and more importantly, implement interventions that include cultural strengths and knowledges (Ka’apu & Burnette, Citation2019) and build on the sociocultural structures within communities (Bryant et al., Citation2021). These AI/AN suicide prevention efforts reorient suicide prevention to include concepts of equity, justice, mutuality, fairness, democracy, and community self-determination (Fitzpatrick, Citation2018). Both historical and contemporary contextual factors create AI/AN risk, and thus prevention efforts must acknowledge and address them. shows the reasoning for this approach, and delineates the underpinning assumptions (what), the rationale (why), and how: the key practices for implementation. illustrates how the three strength-based interventions highlighted in this essay apply key concepts and fit within the prevention spectrum.

AI/AN COMMUNITY-DRIVEN, STRENGTHS-BASED, AND COLLECTIVE STRATEGIES

Lessons learned from AI/AN communities expand on recent calls to include social determinants in suicide prevention efforts (Iskander & Crosby, Citation2021; Steelesmith et al., Citation2019; Hirsch & Cukrowicz, Citation2014; David-Ferdon et al., Citation2016), and focus on structural violence created by colonization. At a time when suicide rates are rising most precipitously for young people ages 10 to 14 who belong to marginalized communities (Benton, Citation2022), this perspective is vital. Here, we extend this view to include the importance of strengths-based, relationship-oriented and culturally-situated strategies of AI/AN suicide prevention as a way to resist oppression and elevate collective and personal visions for life. Our examples from Yup’ik, Inupiaq and White Mountain Apache communities respond to the impact of colonization and historical trauma and importantly promote multilevel protective factors and preventive processes within communities. Indirectly challenging structural racism, each exemplar incorporates a collective orientation to strengthen connectivity between generations, social networks, and cultures over time, and ranges from health promotion to crisis intervention or across the prevention spectrum to reflect universal, selective and indicated approaches.

QUNGASVIK: CULTURAL RESISTANCE TO THE MARGINALIZATION OF YUUYARAQ (THE YUP’IK WAY OF BEING)

Qungasvik is an Indigenously-developed (Walters et al., Citation2020), strengths-based intervention to confront suicide and alcohol misuse among young people in rural Alaska Native communities. The approach reorients suicide prevention through intervention activities that constitute cultural resistance to historical and ongoing oppression, and to the marginalization of yuuyaraq, the Yup’ik way of life. Qungasvik is defined through four characteristics: (a) Indigenous local control, (b) Indigenous theory of change model, (c) Indigenous contextual and community-driven implementation, and (d) Indigenous approach to knowledge development (Rasmus et al., Citation2019). These four elements center Qungasvik in a Yup’ik knowledge system. This system guides the implementation of strategies that strengthen protective, culturally- and locally defined social relationships, practices, attitudes, values, and identities as protective mechanisms to reduce suicide risk.

Using an upstream and Indigenous theory-driven implementation approach, Qungasvik (ph. Kung-az-vik, Tools for Life) builds multi-level, place-based protective factors for Yup’ik young people living in rural communities in southwest Alaska. Qungasvik reflects and builds on cultural practices that instruct young people in a Yup’ik Indigenous knowledge system learned experientially through yuuraraq (Rasmus, Charles, & Mohatt, Citation2014). The Qungasvik manual (Qungasvik Team, 2018; http://www.qungasvik.org/home/) is organized into modules that are described in the community as teachings. Each teaching provides a basic outline for conduct of an essential Yup’ik cultural practice. As a tribally directed community based participatory research (CBPR) intervention (Rasmus et al., Citation2019), each community adapts these teachings, determining how the teaching will be delivered by them. In addition to enhancing responsiveness to the unique sociocultural structures of these geographically dispersed Yup’ik communities, this adaptive process to implementation enhances local control and ownership, positioning each Indigenous community as an entity with its own distinct cultural protocols and key knowledge that are both crucial and central to constructing a suitable and meaningful intervention.

Qungasvik intervention fidelity involves adhering to (a) the cultural protocols of a Yup’ik community organizing process (Rasmus et al., Citation2019), and (b) delivery in Yup’ik, of the qanruyutet, or the specific protective factors that are assigned to each teaching in the manual (Qungasvik Team, 2018). The socio-organizational protocols for intervention implementation that Qungasvik draws from are described in Yup’ik as qasgirarneq (encircling). Implementation activities according to this protocol begin well before any young people are brought into the teachings. Encircling involves a collective coming together of the Elders, leaders, and family members and the coming to a shared belief in the transformative power of Yup’ik ways of life to build reasons for life for young people. In part, this process involves always coming together to plan important activities, identifying and recruiting those with expertise to lead and carry out the activity, ending in coming together again for a de-briefing on where the activity succeeded in its aims and what has been learned. Cultural experts (individuals recognized by community members as Elders for their cultural knowledge and leadership) are nominated based on their specialized expertise for the planning and delivery of each teaching. While colonization deeply disrupted the yuuyaraq, or ancestral ways of living for Yup’ik families and communities, the centering of Yup’ik knowledge and culture bearers on the frontlines of community-based efforts reenergizes the active process of working within a community’s cultural values to reduce suicide and alcohol misuse among young people.

Qungasvik is a complex or multilevel intervention. The implementation model emphasizes community level efforts that include critical processes of staff onboarding and training. These highlight relationship building between staff and community Elders. Elders provide support, guidance, and cultural knowledge instruction. Coalition building among community partners and parents of young people additionally foster preparatory community action (Rasmus et al., Citation2014). Qungasvik includes elements of universal prevention strategies aligned with a Yup’ik cultural worldview directly promotive of well-being. These protective beliefs, values, and experiences are understood to in turn foster reasons for life and sobriety; these are indirect protective factors that buffer co-occurring suicide and alcohol use risk. This Yup’ik theory of protection (Rasmus et al., Citation2019) composed of family, individual, and community level protective factors is described in the community as dependent, independent, or interdependent qanruyutet. As an intervention, Qungasvik transects the prevention spectrum. While a universal prevention strategy, it also includes elements of selective prevention strategies. In a Yup’ik culturally commensurate approach to this work, these selective prevention elements are delivered through the Qungasvik modules as part of the collective process with all youth. Though the strategies are specifically directed at those young people who are struggling, these teachings are shared with all, so as not to spotlight individuals in this smaller group who are at heightened risk. More detailed description of the intervention and the Yup’ik system of knowledge guiding it appear in a journal special issue (Allen & Mohatt, Citation2014).

PC CARES: PROMOTING COMMUNITY CONVERSATIONS ABOUT RESEARCH TO END SUICIDE, A COMMUNITY MOBILIZATION APPROACH TO UNIVERSAL AND SELECTIVE SUICIDE PREVENTION DEVELOPED WITH INUPIAQ AND YUP’IK COMMUNITIES

Developed in partnership with rural Inupiaq and Yup’ik Alaska Native (AN) communities, Promoting Community Conversations about Research to End Suicide (PC CARES) is a community mobilization intervention which emphasizes community and cultural knowledges, priorities, relationships, and contexts as key to preventing suicide and promoting health. PC CARES involves locally-facilitated series of community education sessions to spark universal and selective prevention activities within institutions and families that increase youth wellbeing and offer support when young people are struggling, but not yet in crisis. This approach reorients suicide prevention to acknowledge struggles caused by colonization and structural violence, and includes concepts such as equity, mutuality, fairness, and community self-determination (Trout, McEachern, Mullany, White, & Wexler, Citation2018; Fitzpatrick, Citation2018).

Uplifting participants’ knowledges, experiences, and relationships, PC CARES uses critical health education techniques to deliver a series of “Learning Circles” (LC). The content of these LCs includes scientific best practices at universal and selective (including postvention) levels (see pc-cares.org), but the number of sessions and the specific content of each is determined with community members and leaders. The pattern of activities within LCs include facilitator-designed opening and closing of sessions, typically opening with a prayer by a community Elder to honor the work. LCs then orient participants to the process and purpose of the session, which include agreements for working together, reminders about safely talking about suicide, and reflection on learning and application from prior LCs. The central LC content includes three main components: 1) “what does the research show” a segment where suicide prevention research—including information targeting universal and selective levels of prevention–is presented in a short, “bite-sized” format; 2) “what do we think,” where participants are invited to reflect and discuss the local relevance of presented information; and 3) “what do we want to do” where participants are prompted to apply the information to their lives, jobs, and communities (Wexler et al., Citation2016). Structured dialogue in each LC is designed to spark locally driven application and grow a collective sense of responsibility for action among family members, community workers, professionals, and other community members in attendance.

The sociocultural approach of PC CARES prioritizes the structure and quality of relationships, collective practices, and social identities within Indigenous communities (Bryant et al., Citation2021). It intentionally builds a community of practice to address the complex and often highly personal issue of youth suicide. An important tenant of PC CARES is that scientific insights can offer new perspectives to address suicide, but community members - through dialogue and reflection - are best able to apply (or not) the research to their lives and work. In this way, the intervention builds on scientific and Indigenous knowledges, making room for participants to resist the typical prescriptive approach to suicide prevention by re-interpreting research information based on their local knowledge (Ka’apu & Burnette, Citation2019).

PC CARES challenges structural racism by unsettling academic and scientific assumptions that knowledge is imparted by experts to those understood as less knowledgeable (a designation which is often racialized). The PC CARES model does this by asserting that community members are best able to assess and apply research-based knowledge to their communities, families, and interpersonal relationships. Through community conversations, participants discuss research findings and evidence-based practices, and explore how (or if) these scientific recommendations apply to their specific circumstances, cultural protocols, and contexts. In this key way, PC CARES acknowledges and uplifts participants’ expertise by inviting them to incorporate their local and cultural knowledges and to consider how their understandings intersect with scientific ideas of best practices. PC CARES promotes self-determination and empowerment at the individual and collective levels, first by asking participants to individually make sense of scientific evidence, and then facilitating connection with other participants to develop a community of practice where local people work collaboratively in their own community to use their ideas to prevent suicide. This approach restructures participants’ relationship to research evidence as active and informed parties in an intervention landscape which has historically almost ubiquitously positioned them as passive recipients of scientific knowledge (Freire, Citation2013).

PC CARES outcomes include strengthened social relationships and local capacity to apply evidence-based strategies in creative, culturally meaningful and appropriate ways. Outcomes include interpersonal support, education and outreach to promote safety and wellness, engaging young people in healthy, often cultural, activities, and suicide prevention and postvention in times of vulnerability. Preliminary results show PC CARES participants did more of these actions after participating in the intervention and reported a strengthening of their ‘community of practice’ or the relationships they could rely on to take local action for suicide prevention.Network analyses revealed that community members with a close friend or family member participating in PC CARES were also more likely to increase suicide prevention activities, without attending PC CARES themselves, indicating a community mobilization effect (Wexler et al., Citation2019). In this way, the intervention prioritizes community relationships and creative, locally-derived application of scientific research to reduce suicide risk and promote youth wellbeing.

NEW HOPE: AN INDICATED INTERVENTION DEVELOPED BY WHITE Mountain APACHE TRIBE-JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PARTNERS

The White Mountain Apache Tribe’s (WMAT) multi-level, public health approach to suicide prevention includes surveillance, case management, community education, and culturally-adapted and culturally-grounded interventions delivered by community mental health specialists and Elders. In 2002, the WMAT exercised its sovereignty and mandated a community-based suicide surveillance system, known as “Celebrating Life (CL)” (Cwik et al., Citation2014). The enactment of this tribal mandate was underpinned by a community-based value system that centers on collective protection of all human beings. As the CL system matured, tribal stakeholders sought the development of interventions to reduce suicide risks and promote protective factors. This approach addresses structural racism by upholding tribal sovereignty that WMAT has always had as the basis for its own holistic and culturally-grounded system of care for those at risk for suicide. This tribally owned and led community-based system by its very nature is trauma informed and exists outside of colonial structures and procedures that exist in mainstream mental health service delivery.

New Hope (NH) is an indicated intervention designed to reduce suicide risk among youth after a suicide attempt developed by WMAT-Johns Hopkins University (JHU) partners (Cwik et al., Citation2016a). This intervention is based on a brief, empirically-validated Emergency Department (ED) intervention (Rotheram-Borus, Piacentini, Cantwell, Belin, & Song, Citation2000). New Hope was adapted in terms of cultural resonance, delivery setting, and facilitation with guidance from a Community Advisory Board and Apache implementers (Cwik et al., Citation2016b). NH is delivered by an Apache case manager to youth and selected family support person in a 2-4 hour visit in a youth-preferred setting and has been adapted to also target youth experiencing recent suicide ideation and binge substance use (O’Keefe et al., Citation2019). NH encourages youth to choose a caring adult to participate in the intervention because family members are critical to reinforcing skills and goals identified during the intervention (Rotheram-Borus et al., Citation1996). The intervention emphasizes the seriousness of the at-risk behavior; teaches coping skills to reduce risk, including emotion regulation, cognitive restructuring, social support, and safety planning; and helps youth overcome barriers to treatment motivation, initiation, and adherence (Cwik et al., Citation2016a).

A centerpiece of NH is a 20-minute video produced by WMAT-JHU with Indigenous actors. It includes vignettes specific to the characteristics of suicide in this community, and Elders speaking in Apache (with sub-titles) about the seriousness of suicide, its impact on the community, their concern for the adolescent, and beliefs about the communal importance of each individual’s life relative to carrying forward their ancestors’ pursuit of survivance and future community well-being. The video uplifts protective Indigenous values and concepts selected to redirect youth’s intentions to self-harm by helping them understand their role in their future, the future of their family, and the community. Key messages strive to connect youth to the power of their Elders and community, and the sacred role each individual plays in moving from a traumatic past to a healthier future for all Apache people. A pilot evaluation of NH showed that after participation, youth who had a recent suicide attempt experienced decreased depression symptoms, suicide ideation, negative cognitive thinking, and increase in connectedness with mental health services (Cwik et al., Citation2016b). Additional evaluation of NH is underway as part of the National Institutes of Health’s Collaborative Hubs to Reduce the Burden of Suicide among American Indian and Alaska Native Youth (U19). This current trial expands the pilot in important ways methodologically, conceptually, and culturally by examining resilience and local indicators of well-being as protective factors against suicide (O’Keefe et al., Citation2019; Haroz et al., Citation2022).

REORIENTING INDIGENOUS SUICIDE PREVENTION: MOVING FROM AN INDIVIDUALLY-CENTERED MENTAL HEALTH MODEL TO A COMMUNITY-CENTERED AND RELATIONALLY-FOCUSED APPROACH

The three case examples described above illustrate the deeper implications of strengths-based and relationally-oriented strategies for suicide prevention that move away from an individually-oriented mental health model to a community-centered and relationally-focused approach. All three honor, reflect and build upon community and cultural perspectives and knowledges, and thus indirectly challenges structural racism that privileges an Eurocentric and individualistic approach. Such efforts resist historical and contemporary colonialism and challenge ongoing structural violence of racism by centering AI/AN values, practices, and knowledges.

In this community-driven, relationally-focused model of AI/AN suicide prevention, the protective elements in worldview, practices, and values as expressed through AI/AN culture and local control represent strategies of resistance that hold significant promise for tailoring effective prevention approaches. Accordingly, AI/AN communities in their response to suicide have advocated for self-determined prevention strategies that utilize Indigenous cultural strategies to promote individual and community protection and well-being (Wexler & Gone, Citation2015). These interventions are typically developed through grassroots community efforts based in local expertise and leadership, grounded in Indigenous knowledge and practices, and often supported through political contexts of tribal sovereignty and self-determination.

Reorienting suicide prevention to affirm the expertise of each AI/AN community in confronting suicide is key to challenging the historical and ongoing structural racism and colonization which is linked to increased suicide risk in these communities. Suicide intervention research, then, includes an imperative that programs and policies are tribally-led and reflect community priorities. Contemporary expressions of historical and current strengths in response to historical and on-going colonial trauma counters deficit formulations, and emphasizes protection conferred through emic strategies over approaches focused primarily on risk reduction (Allen et al., Citation2021). This pivot toward cultural and community models of care reduces suicide risk and reflects important linkages to meaning making, belonging, connectedness for young people and to Indigenous cultural resilience.

Such efforts center cultural understandings and experiences in ways that buffer the effects of colonization or structural violence, and offer important developmental resources for identity development, connection, purpose, and spirituality which can be important touchstones for young people on their paths to adulthood (Allen et al., Citation2021; Elliott-Groves & Fryberg, Citation2019; Fine & Ruglis, Citation2009; Appadurai, Citation2004). These distinctive and animating features of Indigenous life-affirming programming aim to develop resilience, and ultimately support young people’s wellbeing. The role of tribal sovereignty and community self-determination to support and put forth traditional-values-based interventions is an important step toward decolonizing institutional racism inherent in US federal Tribal health and human service systems. Such interventions aim to strengthen communities to better support the young people living in them. In these ways, AI/AN suicide prevention considers and integrates tools for resisting structural violence experienced by marginalized youth and develops processes and navigational attributes needed for positive, culturally-rooted development in context.

IMPLICATIONS OF COMMUNITY CENTERED, RESISTANCE PERSPECTIVE FOR SUICIDE PREVENTION WITH OTHER POPULATIONS EXPERIENCING MARGINALIZATION AND OPPRESSION

The three examples from AI/AN communities presented here offer models of successful and promising strength-based efforts with translational potential across cultures, communities, and contexts. A first step in translating the work presented for other communities involves acknowledging and understanding the complex impact of structural racism on young people of color (Alvarez, Polanco-Roman, Samuel Breslow, & Molock, Citation2022). Another involves reorienting preventative efforts to more broadly value and promote health, holistically. This wider perspective includes the material circumstances, social and political context of communities and families, not just the mental health of individuals within them. Individually-focused approaches alone are not sufficient. We can no longer ignore the social determinants of mental health and suicide. A concerted focus needs to be on the structural racism that affects the health and wellbeing of Indigenous and other marginalized youth. This effort must be done through collaborative and power-sharing processes.

Identity development, including cultural identity, is critical to youth suicide prevention and linked to connectedness, purpose, spirituality, and reasons for living (Wexler, Gubrium, Griffin, & Difulvio, Citation2012). Identity and life-affirming programming needs to develop resistance to marginalizing narratives and support community, relationships, cultural dynamics that enable resilience to support young people’s wellbeing. Connectedness, interpersonal and intergenerational protective factors deserve growing recognition, attention, and application in suicide prevention. This work is best accomplished through grassroots community efforts based in local expertise and embedded in larger community systems of care and development. Such strengths-based approaches can be valuable for all, especially marginalized populations.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lisa Wexler

Lisa Wexler, Professor of Social Work and Research Professor at the Research Center for Group Dynamics, Institute for Social Research, 3838 1080 South University, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

Lauren A. White

Lauren A. White, PhD Student, Joint Program for Social Work and Psychology, School of Social Work, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

Victoria M. O’Keefe

Victoria M. O’Keefe, Assistant Professor, Mathuram Santosham Endowed Chair in Native American Health, Johns Hopkins University, Department of International Health, Social & Behavioral Interventions, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA

Stacy Rasmus

Stacy Rasmus, Director, Center for Alaska Native Health (CANHR), Research Associate Professor Institute of Arctic Biology, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, AK, USA

Emily E. Haroz

Emily E. Haroz, Associate Scientist, Department of International Health, Social & Behavioral Interventions, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore MD, USA

Mary F. Cwik

Mary F. Cwik, Senior Scientist, Department of International Health, Social & Behavioral Interventions, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore MD, USA

Allison Barlow

Allison Barlow, Senior Scientist, Department of International Health, Social & Behavioral Interventions, Director, Johns Hopkins Center for American Indian Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore MD, USA

Novalene Goklish

Novalene Goklish, Senior Research Associate, Behavioral Health Program Manager, Johns Hopkins Center for American Indian Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Whiteriver, AZ, USA

Emma Elliott

Emma Elliott, Assistant Professor, Banks Center for Educational Justice, Affiliate Faculty, Learning Sciences & Human Development, Seattle, WA, USA

Cynthia R. Pearson

Cynthia R. Pearson, Research Professor, Director of Research, Indigenous Wellness Research Institute, University of Washington-School of Social Work, Seattle, WA, USA

James Allen

James Allen, Department of Family Medicine and Biobehavioral Health, Memory Keepers Medical Discovery Team - American Indian and Rural Health Equity, University of Minnesota Medical School, Duluth MN, USA

REFERENCES

- Allen, J., & Mohatt, G. V. (2014). Introduction to ecological description of a community intervention: Building prevention through collaborative field based research. American Journal of Community Psychology, 54(1–2), 83–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-014-9644-4

- Allen, J., Wexler, L., & Rasmus, S. (2021). Protective factors as a unifying framework for strengths-based intervention and culturally responsive American Indian and Alaska native suicide prevention. Prevention Science, 23(1), 59–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-021-01265-0

- Alvarez, K., Polanco-Roman, L., Samuel Breslow, A., & Molock, S. (2022). Structural racism and suicide prevention for ethnoracially minoritized youth: A conceptual framework and illustration across systems. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 179(6), 422–433. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.21101001

- Ansloos, J. (2018). Rethinking indigenous suicide. International Journal of Indigenous Health, 13(2), 8–28. https://doi.org/10.32799/ijih.v13i2.32061

- Ansloos, J., & Peltier, S. (2022). A question of justice: Critically researching suicide with Indigenous studies of affect, biosociality, and land-based relations. Health, 26(1), 100–119. https://doi.org/10.1177/13634593211046845

- Appadurai, A. (2004). The capacity to aspire: Culture and the terms of recognition. Culture and Public Action, 59, 62–63.

- Barker, J. (2021). Red scare: The state’s Indigenous terrorist (Vol. 14). University of California Press.

- Barker, J. (Ed.). (2017). Critically sovereign: Indigenous gender, sexuality, and feminist studies. Duke University Press.

- Barker, B., Goodman, A., & DeBeck, K. (2017). Reclaiming Indigenous identities: Culture as strengths against suicide among Indigenous youth in Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health = Revue Canadienne de Sante Publique, 108(2), e208–e210. https://doi.org/10.17269/cjph.108.5754

- Bell, S., Deen, J. F., Fuentes, M., & Moore, K. (2021). AAP COMMITTEE ON NATIVE AMERICAN CHILD HEALTH. Caring for American Indian and Alaska Native children and adolescents. Pediatrics, 147(4), e2021050498. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2021-050498

- Benton, T. D. (2022). Suicide and suicidal behaviors among minoritized youth. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics, 31(2), 211–221.

- Borell, B. (2017). The nature of the gaze: A conceptual discussion of societal privilege from an indigenous perspective [Doctoral dissertation]. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Massey University, SHORE & Whāriki Research Centre, College of Health, Aotearoa New Zealand.

- Brann, K. L., Baker, D., Smith-Millman, M. K., Watt, S. J., & DiOrio, C. (2021). A meta-analysis of suicide prevention programs for school-aged youth. Children and Youth Services Review, 121, 105826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105826

- Brave Heart, M. Y., & DeBruyn, L. M. (1998). The American Indian Holocaust: Healing historical unresolved grief. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research, 8(2),60–82. https://doi.org/10.5820/aian.0802.1998.60

- Brooks, J. R., Hong, J. H., Cheref, S., & Walker, R. L. (2020). Capability for suicide: Discrimination as a painful and provocative event. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 50(6), 1173–1180. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12671

- Bryant, J., Bolt, R., Botfield, J. R., Martin, K., Doyle, M., Murphy, D., Graham, S., Newman, C. E., Bell, S., Treloar, C., Browne, A. J., & Aggleton, P. (2021). Beyond deficit: ‘strengths‐based approaches’ in Indigenous health research. Sociology of Health & Illness, 43(6), 1405–1421. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.13311

- Burnette, C., Ramchand, R., & Ayer, L. (2015). Gatekeeper training for suicide prevention: A theoretical model and review of the empirical literature. Rand Health Quarterly, 5(1), 16.

- Burns, J., Angelino, A. C., Lewis, K., Gotcsik, M. E., Bell, R. A., Bell, J., & Empey, A. (2021). Land rights and health outcomes in American Indian/Alaska native children. Pediatrics, 148(5), e2020041350. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-041350

- Center for American Indian Health. (2021). Culture forward: A strengths and culture based tool to protect our native youth from suicide. John Hopkins Bloomberg school of Public Health. https://caih.jhu.edu/programs/cultureforward

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. (2022). Web-based injury statistics query and reporting system (WISQARS) [online]. www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars

- Centers for Disease Control. (2020). WONDER. https://wonder.cdc.gov/controller/datarequest/D76

- Cwik, M. F., Tingey, L., Lee, A., Suttle, R., Lake, K., Walkup, J. T., & Barlow, A. (2016a). Development and piloting of a brief intervention for suicidal American Indian adolescents. American Indian. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research (Online), 23(1), 105–124. https://doi.org/10.5820/AI/AN.2301.2016.105

- Cwik, M., Barlow, A., Goklish, N., Larzelere-Hinton, F., Tingey, L., Craig, M., Lupe, R., & Walkup, J. T. (2014). Community-based surveillance and case management for suicide prevention: A tribally initiated system. American Journal of Public Health, 104 Suppl 3(Suppl 3), e18-23–e23. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.301872

- Cwik, M., Tingey, L., Maschino, A., Goklish, N., Larzelere-Hinton, F., Walkup, J., & Barlow, A. (2016b). Decreases in suicide deaths and attempts linked to the white mountain apache suicide surveillance and prevention system, 2001-2012. American Journal of Public Health, 106(12), 2183–2189. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303453

- David-Ferdon, C., Crosby, A. E., Caine, E. D., Hindman, J., Reed, J., & Iskander, J. (2016). CDC grand rounds: Preventing suicide through a comprehensive public health approach. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 65(34), 894–897. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6534a2

- Delgado, R., & Stefancic, J. (2001). An introduction to critical race theory. New York University.

- Deloria, V. (1997). Red earth, white lies: Native Americans and the myth of scientific fact. Fulcrum Publishing.

- Dunbar-Ortiz, R. (2014). An indigenous peoples’ history of the United States (vol. 3). Beacon Press.

- Duran, E., Duran, B., Heart, M. Y. H. B., & Horse-Davis, S. Y. (1998). Healing the American Indian soul wound. In International handbook of multigenerational legacies of trauma (pp. 341–354). Springer.

- Elliott‐Groves, E. (2018). Insights from Cowichan: A Hybrid approach to understanding suicide in one First Nations’ collective. Suicide and Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 48(3), 328–339. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12364

- Elliott-Groves, E., & Fryberg, S. A. (2019). A future denied” for young Indigenous people: From social disruption to possible futures. Handbook of Indigenous Education, 631–649.

- Evans-Campbell, T. (2008). Historical trauma in American Indian/Native Alaska communities: A multilevel framework for exploring impacts on individuals, families, and communities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 23(3), 316–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260507312290

- Figley, C. R., & Burnette, C. E. (2017). Building bridges: Connecting systemic trauma and family resilience in the study and treatment of diverse traumatized families. Traumatology, 23(1), 95–101. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000089

- Fine, M., & Ruglis, J. (2009). Circuits and consequences of dispossession: The racialized realignment of the public sphere for US youth. Transforming Anthropology, 17(1), 20–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-7466.2009.01037.x

- Fitzgerald, H. E., Johnson, D. J., Allen, J., Villarruel, F. A., & Qin, D. B. (2021). Historical and race-based trauma: Resilience through family and community. Adversity and Resilience Science, 2(4), 215–223. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42844-021-00048-4

- Fitzpatrick, S. J. (2018). Reshaping the ethics of suicide prevention: Responsibility, inequality and action on the social determinants of suicide. Public Health Ethics, 11(2), 179–190. https://doi.org/10.1093/phe/phx022

- Freire, P. (2013). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Routledge.

- Haroz, E. E., Ivanich, J. D., Barlow, A., O'Keefe, V. M., Walls, M., Kaytoggy, C., Suttle, R., Goklish, N., & Cwik, M. (2022). Balancing cultural specificity and generalizability: Brief qualitative methods for selecting, adapting, and developing measures for research with American Indian communities. Psychological Assessment, 34(4), 311–319. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0001092

- Hirsch, J. K., & Cukrowicz, K. C. (2014). Suicide in rural areas: An updated review of the literature. Journal of Rural Mental Health, 38(2), 65–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/rmh0000018

- Iskander, J. K., & Crosby, A. E. (2021). Implementing the national suicide prevention strategy: Time for action to flatten the curve. Preventive Medicine, 152(Pt 1), 106734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106734

- Johns, M. M., Lowry, R., Haderxhanaj, L. T., Rasberry, C. N., Robin, L., Scales, L., Stone, D., & Suarez, N. A. (2020). Trends in violence victimization and suicide risk by sexual identity among high school students—youth risk behavior survey, United States, 2015–2019. MMWR Supplements, 69(1), 19–27. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su6901a3externalicon

- Ka’apu, K., & Burnette, C. E. (2019). A culturally informed systematic review of mental health disparities among adult Indigenous men and women of the USA: What is known? British Journal of Social Work, 49(4), 880–898. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcz009

- Madubata, I., Spivey, L. A., Alvarez, G. M., Neblett, E. W., & Prinstein, M. J. (2022). Forms of Racial/Ethnic Discrimination and Suicidal Ideation: A Prospective Examination of African-American and Latinx Youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 51(1), 23-31.

- Marshall, A. (2016). Focus: Sex and gender health: Suicide prevention interventions for sexual & gender minority youth: An unmet need. The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 89(2), 205.

- Martínez-Alés, G., Jiang, T., Keyes, K. M., & Gradus, J. L. (2021). The recent rise of suicide mortality in the United States. Annual Review of Public Health, 43, 99–116. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-051920-123206

- McDermott, E., Hughes, E., & Rawlings, V. (2018). The social determinants of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth suicidality in England: A mixed methods study. Journal of Public Health (Oxford, England), 40(3), e244–e251. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdx135

- Milner, A., McClure, R., & De Leo, D. (2012). Socioeconomic determinants of suicide: An ecological analysis of 35 countries. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 47(1), 19–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-010-0316-x

- O’Keefe, V. M., Haroz, E., Ivanich, J., Goklish, N., Larzelere-Hinton, F., Cwik, M., & Barlow, A. (2019). Testing the impact of brief risk reduction and cultural strengths-based interventions on reducing youth suicide risk in an American Indian community using a SMART design. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1675. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7996-2

- Opara, I., Assan, M. A., Pierre, K., Gunn, J. F., III, Metzger, I., Hamilton, J., & Arugu, E. (2020). Suicide among Black children: An integrated model of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide and intersectionality theory for researchers and clinicians. Journal of Black Studies, 51(6), 611–631. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021934720935641

- Pitman, A., & Caine, E. (2012). The role of the high-risk approach in suicide prevention. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 201(3), 175–177. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.111.107805

- Ramchand, R., Gordon, J. A., & Pearson, J. L. (2021). Trends in suicide rates by race and ethnicity in the United States. JAMA Network Open, 4(5), e2111563. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.11563

- Rasmus, S. M., Charles, B., & Mohatt, G. V. (2014). Creating Qungasvik (a Yup’ik intervention “toolbox”): Case examples from a community-developed and culturally-driven intervention. American Journal of Community Psychology, 54(1–2), 140–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-014-9651-5

- Rasmus, S. M., Trickett, E., Charles, B., John, S., & Allen, J. (2019). The qasgiq model as an indigenous intervention: Using the cultural logic of contexts to build protective factors for Alaska Native suicide and alcohol misuse prevention. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 25(1), 44–54. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000243

- Reid, P., Cormack, D., & Paine, S. J. (2019). Colonial histories, racism and health—The experience of Māori and Indigenous peoples. Public Health, 172, 119–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2019.03.027

- Robinson, J., Bailey, E., Witt, K., Stefanac, N., Milner, A., Currier, D., Pirkis, J., Condron, P., & Hetrick, S. (2018). What works in youth suicide prevention? A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine, 4-5, 52–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2018.10.004

- Rotheram-Borus, M. J., Piacentini, J., Cantwell, C., Belin, T. R., & Song, J. (2000). The 18-month impact of an emergency room intervention for adolescent female suicide attempters. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(6), 1081–1093. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.68.6.1081

- Rotheram-Borus, M. J., Piacentini, J., Van Rossem, R., Graae, F., Cantwell, C., Castro-Blanco, D., Miller, S., & Feldman, J. (1996). Enhancing treatment adherence with a specialized emergency room program for adolescent suicide attempters. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 35(5), 654–663. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199605000-00021

- Rubin, R. (2021). New Grants for Suicide Prevention. JAMA, 326(12), 1138–1138. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.15923

- Sheftall, A. H., Vakil, F., Ruch, D. A., Boyd, R. C., Lindsey, M. A., & Bridge, J. A. (2022). Black youth suicide: Investigation of current trends and precipitating circumstances. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 61(5), 662–675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2021.08.021

- Smith, L. T. (2021). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Standley, C. J., & Foster‐Fishman, P. (2021). Intersectionality, social support, and youth suicidality: A socioecological approach to prevention. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 51(2), 203–211. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12695

- Steelesmith, D. L., Fontanella, C. A., Campo, J. V., Bridge, J. A., Warren, K. L., & Root, E. D. (2019). Contextual factors associated with county-level suicide rates in the United States, 1999 to 2016. JAMA Network Open, 2(9), e1910936-e1910936. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.10936

- Trout, L., McEachern, D., Mullany, A., White, L., & Wexler, L. (2018). Decoloniality as a framework for indigenous youth suicide prevention pedagogy: Promoting community conversations about research to end suicide. American Journal of Community Psychology, 62(3-4), 396–405. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12293

- Walls, M. L., Hautala, D., & Hurley, J. (2014). “Rebuilding our community”: Hearing silenced voices on Aboriginal youth suicide. Transcultural Psychiatry, 51(1), 47–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461513506458

- Walters, K. L., Johnson-Jennings, M., Stroud, S., Rasmus, S., Charles, B., John, S., Allen, J., Kaholokula, J. K., Look, M. A., de Silva, M., Lowe, J., Baldwin, J. A., Lawrence, G., Brooks, J., Noonan, C. W., Belcourt, A., Quintana, E., Semmens, E. O., & Boulafentis, J. (2020). Growing from our roots: Strategies for developing culturally grounded health promotion interventions in American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian communities. Prevention Science: The Official Journal of the Society for Prevention Research, 21(Suppl 1), 54–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-018-0952-z

- Wexler, L. (2009). Identifying colonial discourses in Inupiat young people’s narratives as a way to understand the no future of Inupiat youth suicide. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research (Online), 16(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.5820/aian.1601.2009.1

- Wexler, L. M., & Gone, J. P. (2012). Culturally responsive suicide prevention in indigenous communities: Unexamined assumptions and new possibilities. American Journal of Public Health, 102(5), 800–806. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300432

- Wexler, L., Gubrium, A., Griffin, M., & Difulvio, G. (2012). Promoting positive youth development and highlighting reasons for living in northwest Alaska through digital storytelling. Health Promotion Practice, 14(4), 617–623. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839912462390

- Wexler, L., McEachern, D., DiFulvio, G., Smith, C., Graham, L. F., & Dombrowski, K. (2016). Creating a community of practice to prevent suicide through multiple channels: Describing the theoretical foundations and structured learning of PC CARES. International Quarterly of Community Health Education, 36(2), 115–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272684X16630886

- Wexler, L., Rataj, S., Ivanich, J., Plavin, J., Mullany, A., Moto, R., Kirk, T., Goldwater, E., Johnson, R., & Dombrowski, K. (2019). Community mobilization for rural suicide prevention: Process, learning and behavioral outcomes from Promoting Community Conversations About Research to End Suicide (PC CARES) in Northwest Alaska. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 232, 398–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.05.028

- Wyman Battalen, A., Mereish, E., Putney, J., Sellers, C. M., Gushwa, M., & McManama O'Brien, K. H. (2020). Associations of discrimination, suicide ideation severity and attempts, and depressive symptoms among sexual and gender minority youth. Crisis, 42(4), 301–308. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000718

- Xiao, Y., & Lindsey, M. A. (2021). Racial/ethnic, sex, sexual orientation, and socioeconomic disparities in suicidal trajectories and mental health treatment among adolescents transitioning to young adulthood in the USA: A population-based cohort study. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 48(5), 742–756. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-021-01122-w