Abstract

Introduction

Medical students have been known to face numerous mental health issues at disproportionately high rates. Of pertinence, medical students have been shown to have high rates of suicidal thoughts and behavior. However, little is known about the risks and warning signs for death by suicide in this group. We therefore conducted a systematic review regarding the factors associated with medical student suicide mortality.

Methods

Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, we conducted searches in six different databases. Studies with stratified data on at least one suicide death by a medical student were eligible for inclusion.

Results

Searches produced a total of 1744 articles, and of those, 13 articles were eligible for inclusion. There was a pooled total of 362 suicide deaths of medical students across five different countries. 67.6% of deaths occurred among male students, primarily in their early twenties. Students in their later years of medical school were shown to be more likely to die by suicide, as were those with a history of psychiatric issues such as depression. Motivations for suicide were academic stress/failure, harassment/bullying, and relationship issues. Warning signs for suicide among medical students were recent changes in mood/behavior and leaving a suicide note.

Discussion

Numerous risks and warning signs of suicide have been described in our review. Medical schools may have an important role in lowering suicide deaths by medical students; impactful change can occur through better support, changes in curriculum, and appropriate data collection.

HIGHLIGHTS

Numerous modifiable risk factors have been linked to suicide in medical students

Warning signs include recent changes in mood/behavior, and leaving a suicide note

Medical schools need proactive, multi-level approaches to reduce medical student suicide

INTRODUCTION

Medical students face a wide array of stressors during their education. Stressors that are commonly experienced by medical students are feelings of helplessness, loss of emotional connection to those outside of medical school, frustration, and competition (Dahlin et al., Citation2005; Dyrbye et al., Citation2008; Saipanish, Citation2003; Wilson et al., Citation2023). Studies in the United States of America (USA) have shown that the medical student mental health tends to start declining for students during their education due to factors such as stress, burnout, and depressive moods; notably, the mental health outcomes of this group are frequently poorer compared to age matched populations (Dahlin et al., Citation2005; Dyrbye et al., Citation2008). This all has broader implications and consequences, such as detrimental effects on ethical conduct, empathy, professionalism, and relationships, and – critically – contributes to suicidal ideation (Dyrbye et al., Citation2008; Oreskovich et al., Citation2012; Shanafelt et al., Citation2003; West et al., Citation2006).

As is the case with younger people in the general population, suicidality among medical students is a major issue (World Health Organization, Citation2021). A meta-analysis of 195 studies which encompassed more than 129,000 medical students worldwide showed that 27.2% of students screened positive for depression and that 11.1% reported suicidal ideation during medical school (Rotenstein et al., Citation2016). These findings have also been replicated in other reviews (Kaggwa et al., Citation2022; Watson et al., Citation2020).

While there is a notable amount of literature on aspects of suicidal ideation, suicidal behavior, and suicide rates among medical students (Blacker et al., Citation2019; Kaggwa et al., Citation2022; Watson et al., Citation2020), little has been written regarding risk and warning signs for suicide mortality in this group. It is essential to study these factors in order for support to be provided to those who are at the highest risk. Therefore, our objective is to provide a systematic review of the literature regarding factors and warning signs associated with suicide mortality among medical students. To our knowledge, this is the first review to be written on this topic.

METHODS

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., Citation2021). There was no registered protocol for this review.

Searches

Searches were conducted on January 31, 2023 in six different databases: PubMed, Scopus, Embase, PsycInfo, Web of Science and Global Health. Search terms were developed based on the population under study (which was medical students), and health outcomes, which were death by suicide. Search terms, by respective database, are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Eligibility Criteria

Full-text studies were eligible for inclusion in this review if they: (1) were written in English, (2) included medical students who died of suicide, and (3) described any demographic or other factors for those who died. A preliminary search of the literature showed that there were a limited number of large-scale studies on this topic, and the authors therefore aimed to allow for as broad of an inclusion criterion as possible in order to include as much literature as possible. While the authors also recognize that literature from decades earlier may not be as relevant as more recent literature, it was deemed worthwhile to not place any restrictions on place or date of publication to ensure that as much literature as possible could be gathered; an added benefit of this was that it allowed for comparisons of risks and warnings across time periods. Furthermore, case reports, case series, and studies utilizing secondary sources of data were all eligible for inclusion in this review. Articles were excluded if they were not in English, did not describe details regarding suicide deaths of medical students, or did not provide stratified data.

Study Screening

As per the PRISMA guidelines, after searches were conducted, duplicate articles were removed during the screening process. Thereafter, articles were analyzed by title/abstract, with remaining articles then screened by full text. Reasons for exclusion by full text were provided. The entire screening process was conducted independently by two reviewers (K.V. and H.P.), with discrepancies being resolved by consensus.

Data Extraction

Data relating to characteristics of studies, and characteristics of those who died by suicide, was extracted. In terms of study characteristics, the following information was retrieved from each study: year, setting, date of suicide(s), sources of data, and analyses/data provided (such as descriptive statistics). For individual characteristics of those who died by suicide, the following information was extracted by study: number of deaths, gender breakdown, setting, date, age, means of suicide, year in program for medical degree (MD)/bachelor of medicine, bachelor of surgery (MBBS), comorbidities, and other factors. Other factors included relevant variables such as whether or not they left a suicide note, sources of stress, relationship status, and recent changes in behavior. As was the case with selection of articles, data extraction was conducted independently by two reviewers (K.V. and H.P.), with any discrepancies again being resolved by consensus.

Synthesis and Reporting of Data

After extraction of data was completed, data was pooled wherever possible. This was done by providing a summated tabulation of relevant variables for those who died by suicide; this was done for total deaths, gender, country, means/method of suicide, comorbidities, year of study in medicine, factors contributing to motive for suicide, and other factors such as relationship status, changes in mood/behavior, and if they left a suicide note. Additional data and trends were also described qualitatively.

Quality Assessments

Each of the studies included in this review underwent a quality assessment. The quality assessment tools used in this review were the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal tools (Joanna Briggs Institute., Citation2023). Following approaches that have been taken previously (Adalbert et al., Citation2021; Bowring et al., Citation2016; Xu et al., Citation2017), the tools were adapted to provide a score based on the number of “yes” or “no” responses for each relevant metric. If a particular metric was not relevant to the study, then it was marked as “not applicable (NA)” and did not contribute to the total score. While the JBI tools have different total metrics across study methodologies (for example, cohort studies are on an eleven-item scale, whereas case series are on a ten-item scale), scores were compared across methodologies by calculating a percentage based on the total number of “yes” responses to relevant metrics.

RESULTS

Article Inclusion

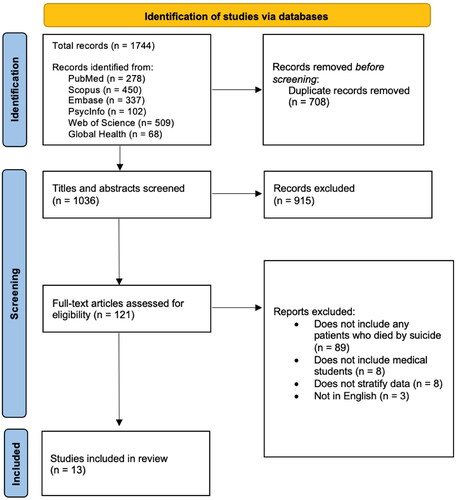

Searches produced a total of 1744 articles. After 708 duplicates were removed, a total of 1036 articles were screened by title/abstract. Of those, 121 underwent full-text analysis to determine eligibility. Ultimately, 13 articles were deemed to be eligible for inclusion in this review. The most frequent reasons for exclusion of articles (during the title/abstract and full-text screening stages respectively) were that they did not include any patients who died of suicide, did not include medical students, or did not provide stratified data. The screening workflow is depicted in .

FIGURE 1. PRISMA diagram depicting workflow for the screening process (adapted from Page et al., Citation2021).

Study Characteristics

Studies from five different countries were included: Bharat (India) (Chahal et al., Citation2022; Jahan et al., Citation2021; Jha et al., Citation2014; Pruthi et al., Citation2015; Singh, Citation2022), Japan (Uchida & Uchida, Citation2017), USA (Cheng et al., Citation2014; Hays et al., Citation1996; Kaltreider, Citation1990; Rockwell et al., Citation1981; Simon, Citation1968), Bangladesh (Mamun et al., Citation2020), and Canada (Simon, Citation1968; Zivanovic et al., Citation2018). Dates of suicide deaths varied greatly across studies, ranging from 1950 – 2022. Sources of data were most frequently either surveys/questionnaires/interviews disseminated to the deans of medical schools who thereafter provided information and statistics regarding medical student suicide (n = 6), or retrospective data from news reports which provided details of student suicides (n = 7). Characteristics of studies are listed in . Overall, study quality tended to be relatively low, with the average quality assessment score being 58.3%. However, studies by Jahan et al. (Citation2021) and Uchida and Uchida (Citation2017) were exceptions to this, as they had overall quality assessment scores of 80.0% and 90.9% respectively. Commonly identified methodological flaws, as per the quality assessments, were a lack of consideration of confounding variables, a lack of clarity regarding demographics/clinical histories, and limited statistical analyses being conducted.

TABLE 1. Characteristics of all included studies.

Student Suicide Totals

There was a pooled total of 362 medical student suicide deaths. Sample sizes across studies tended to vary greatly. Multiple studies included no more than two deaths (Jahan et al., Citation2021; Jha et al., Citation2014; Kaltreider, Citation1990), with the highest number of deaths reported in a single study being 125 (Chahal et al., Citation2022). The highest number of deaths were described in India (44.7%), followed by Japan (27.2%), and USA (22.4%).

Demographics

Demographics, and other factors connected to student suicide death, are listed in . The majority of studies reported a higher proportion of deaths among male medical students compared to female students. For example, Hays et al. (Citation1996) reported 15 medical student suicides, 14 of which (93.3%) occurred among males. Similarly, of the 80 suicide deaths reported by Uchida and Uchida (Citation2017), 65 (81.3%) occurred among males. The pooled total of all studies showed that 67.6% of medical student suicides were among males. Pooled findings are listed in .

TABLE 2. Characteristics of medical students who died by suicide.

TABLE 3. Pooled totals of medical student suicide factors.

Though there was heterogeneity in reporting of age, when reported, it was shown that the overwhelming majority of those who died were in their early twenties, with the oldest individual being 30 years of age (Rockwell et al., Citation1981). Studies that did stratify for differences in age by gender did not find any notable differences. For example, in a study on 125 suicide deaths, the mean age of males who died (78 total deaths) was 21.2 years (SD = 2.3), whereas the mean age for females (47 total years) was 21.1 years (SD = 2.2) (Chahal et al., Citation2022).

Year of medical school was also consistently reported across studies. The highest proportion of recorded deaths occurred in the final years (4th/5th/6th/immediately prior to graduation) of medical school (30.1%). Proportions tended to be slightly lower in each respective earlier year of medical school, with those in their 3rd years making up 29.0% of total deaths, those in 2nd year making 23.7% of deaths, and those in their 1st year making up 17.2% of deaths. A single study statistically analyzed differences in suicide deaths among medical students of different years and showed both that first year students were significantly less likely to die by suicide compared to other year groups, and that those in their final years were the most likely of year groups to die by suicide (Uchida & Uchida, Citation2017); notably, this study also showed that those who repeated an academic year in medical school had higher rates of suicide. (Uchida & Uchida, Citation2017).

Means/Method of Suicide

The most commonly reported method of suicide was hanging (64.3%), which was reported across four studies (Chahal et al., Citation2022; Cheng et al., Citation2014; Mamun et al., Citation2020; Singh, Citation2022). The next most frequently reported means were jumping from a building (12.1%), and overdose/poisoning (12.1%). Standing in front of a train and firearm usage were other means, that were described less frequently. Notably, six studies did not describe the means of suicide at all (Zivanovic et al., Citation2018; Uchida & Uchida, Citation2017; Simon, Citation1968; Rockwell et al., Citation1981; Pruthi et al., Citation2015; ; Jahan et al., Citation2021).

Motives for Suicide

Motivations for suicide were described in five studies (Pruthi et al., Citation2015; Mamun et al., Citation2020; ; Jahan et al., Citation2021; Chahal et al., Citation2022; Jha et al., Citation2014). Academic stress, and academic failures were the most common factors attributed as motive for suicide (59.2%). Aside from this, harassment/humiliation/bullying/hazing of students was described 20.4% of the time, as were relationship issues. Relationship issues included marital discord, troubled love affairs, recent death of a loved one, and parental divorce (Chahal et al., Citation2022; Mamun et al., Citation2020; Pruthi et al., Citation2015).

Additional Factors

Leaving a suicide note was an important suicide warning sign which occurred among 21 individuals who died by suicide. Other prominent warning signs, which were predominantly shown by males, were a recent change in mood/behavior, a past suicide attempt, and absenteeism from work/class (Chahal et al., Citation2022).

Pre-existing comorbidities were denoted for 44 (12.2%) of deaths. These were nearly universally psychiatric/mental health problems, which were rarely described in further detail of those comorbidities which were specified, four individuals had depression, and one individual had a personality disorder.

DISCUSSION

Our review has highlighted that certain medical students may be at a higher risk of suicidality, and suicide mortality in particular. Summarized key findings of this review, as well as implementable strategies to lower risk, are shown in . It has been shown that males may be at an elevated risk, as are those who are undergoing academic stress, failing in school, facing harassment/bullying, and are experiencing hardships in personal relationships. Those with psychological comorbidities and those in the later years of medical school, particularly those who have had to repeat a year, may also be at higher risk.

TABLE 4. Summary of key risk factors and warning signs for medical student suicide, and implementable strategies to support students.

These findings have important implications for medical schools and public health programs that seek to address suicidality among medical students. It has already been well-documented, regardless of whether they are dealing with suicidality or not, that stress and anxiety due to academic studies is widespread amongst medical students (Abdulghani et al., Citation2011; Bergmann et al., Citation2019; Ragab et al., Citation2021). Wellness interventions and provision of academic supports, even to those who are not necessarily reaching out for assistance, will hence be imperative. Wellness can also be maintained by ensuring ease of access to medical student counseling services, emergency crisis support, and primary health care.

Curriculum changes utilizing a pass/fail grading system and collaborative, peer-support based learning programs alongside individualized interventions that foster cultivation of extra-curricular hobbies, support networks, and student resilience may all offer practical benefits (Klein & McCarthy, Citation2022). Addressing mental health stigma and encouraging open discussion of mental health challenges will be valuable. As well, considering that failure in exams tended to exacerbate risk for suicide, future research should focus on how medical schools can reshape curriculums and support students who are either failing, or are on the verge of failing. Importantly, even those who are close to finishing medical school may continue to show a high risk for death by suicide.

A number of important warning signs were shown by those who died by suicide. Leaving a suicide note should be regarded as a clear and immediate risk for imminent suicide; less clearly immediate warning signs were recent changes in mood/behavior, absenteeism, and past suicide attempts. It has previously been stated that for medical students, awareness of mental health symptoms, their identification, and the availability of mental health services dedicated specifically to medical students can all have a role in reducing suicide in this group (Gentile & Roman, Citation2009). Building on this, it is important that medical school faculty are also aware of these potential warning signs. Furthermore, as a number of the deaths were by hanging and hence likely to be in students’ place of residence, it is imperative that some mental health resources be available to students at any hour of the day/night to be able to address possible imminent mental health emergencies.

An important finding from our review is that much of the data regarding suicide mortality among medical students is either described in minimal detail from university deans, or is from news reports. This has been shown to be the case across cultural contexts. Therefore, there is a clear and urgent need for universities to develop databases and information tracking with investigations and follow-up to better understand the factors associated with medical student suicide. Sharing of knowledge among universities and policymakers at state, national and even international levels in a manner that ensures both transparency, and confidentiality, will be valuable in helping to better shape suicide prevention programs for this potentially high-risk group. In addition, more large-scale research should be dedicated toward better understanding potential warning signs, the effectiveness of wellness initiatives in lowering suicide rates, and the persisting impacts of suicide on medical students and faculty.

Future research on medical student suicide should also aim to evaluate differences and similarities between risk factors for suicidal ideation and planning, compared to risk factors for death by suicide; this will be integral in further supporting students who may be in the latter stages of contemplating a suicide attempt. Utilization of existing theoretical models to guide future research and policy development in this domain will be integral. An example of this is the integrated motivational-volitional model (IMV) of suicidal behavior, which breaks down suicide risk into three progressively significant phases: the pre-motivational phase, where specific factors (such as life events) can increase risk for eventual development of suicidal ideation; the motivational phase, where threats to self and feelings of entrapment can further increase risk and severity of suicidal intent; and the volitional phase where there is behavioral enactment in times of vulnerability when there is planning, access to means, exposure to suicide, and other emergent triggering events (O'Connor & Kirtley, Citation2018).

Studies from five different countries were included in this review and, of these countries, the highest proportion of data came from India. Notably, compared to USA and Japan (where studies in this review were conducted), India has a lower nationwide suicide mortality rate as of 2019 (World Health Organization, Citation2022). The suicide rate (deaths per 100,000 individuals) in India was 12.7 in the year 2019, compared to the rate in USA which was 16.1 and Japan, which had a rate of 15.3 (World Health Organization, Citation2022). Of further relevance is that Bangladesh, which is a context with one included study in this review, had a nationwide suicide rate of 3.7 (World Health Organization, Citation2022). Therefore, a trend observed from this data is that, while lower-middle income countries (LMICs) tend to have lower suicide rates in the general population when compared to high-income countries (HICs), medical students may nonetheless be at a higher risk of suicide in LMICs compared to HICs. Additionally, it is noteworthy that suicide rates across both HICs and LMICs are markedly higher amongst males compared to females (World Health Organization, Citation2022), as this trend was also demonstrated in this review, amongst medical students. In consideration of all of this, future research should focus toward understanding the factors that contribute to suicide risk both across, and within countries. More research is also clearly needed in other countries and cultural contexts.

There were a number of limitations to our review. Studies from only five countries in the world were included, which limits the generalizability of the findings; furthermore, of the studies that were included, only a segment provided a thorough description of factors, motives, and methods of suicide. An additional limitation was that a high number of included studies relied on reporting of isolated cases with small sample sizes, and only one study provided comparisons with control groups (Uchida & Uchida, Citation2017). Quality assessments demonstrated that numerous studies had methodological flaws that commonly resulted in poor study quality. There is a hence a clear need for more studies that provide comprehensive reporting of suicide-related factors for medical students, and which utilize comparison groups (such as students from other academic disciplines) when possible.

Regardless of the aforementioned limitations, there are important strengths to this review. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review on the topic of medical student mortality risks and warning signs, and it hence provides important insights regarding the most severe mental health consequences of hardships faced by medical students. Furthermore, these findings offer a number of different avenues for future research based on the diverse risk factors, warning signs, and demographic factors that were described. These findings have the potential to encourage positive change in medical school curricula, and to provide a basis behind better data collection and data sharing between universities regarding medical student suicide mortality.

In conclusion, this review has shown that there are numerous potential warning signs and risk factors for suicide among medical students. Being male, in the final years of medical school, and having psychological comorbidities may increase risk. Academic stress/failure, harassment/bullying and relationship issues may also be contributors to suicide risk. Awareness of warning signs such as recent changes in behaviors and leaving a suicide note are important in identifying at-risk students. Medical schools, through better support, revisions of curricula, and data collection, can offer a valuable role in helping to prevent medical student suicide.

AUTHOR NOTE

Karan Varshney (MPH), Hinal Patel (MD), and Mansoor Ahmed Panhwar, School of Medicine, Deakin University, Waurn Ponds, Australia.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (22.4 KB)ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors have no additional acknowledgements to be made. No financial support was provided for this work.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Abdulghani, H. M., AlKanhal, A. A., Mahmoud, E. S., Ponnamperuma, G. G., & Alfaris, E. A. (2011). Stress and its effects on medical students: A cross-sectional study at a college of medicine in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition, 29(5), 516–522. https://doi.org/10.3329/jhpn.v29i5.8906

- Adalbert, J. R., Varshney, K., Tobin, R., & Pajaro, R. (2021). Clinical outcomes in patients co-infected with COVID-19 and Staphylococcus aureus: A scoping review. BMC Infectious Diseases, 21(1), 985. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06616-4

- Bergmann, C., Muth, T., & Loerbroks, A. (2019). Medical students’ perceptions of stress due to academic studies and its interrelationships with other domains of life: A qualitative study. Medical Education Online, 24(1), 1603526. https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2019.1603526

- Blacker, C. J., Lewis, C. P., Swintak, C. C., Bostwick, J. M., & Rackley, S. J. (2019). Medical student suicide rates: A systematic review of the historical and international literature. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 94(2), 274–280. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002430

- Bowring, A. L., Veronese, V., Doyle, J. S., Stoove, M., & Hellard, M. (2016). HIV and sexual risk among men who have sex with men and women in Asia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS and Behavior, 20(10), 2243–2265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-015-1281-x

- Chahal, S., Nadda, A., Govil, N., Gupta, N., Nadda, D., Goel, K., & Behra, P. (2022). Suicide deaths among medical students, residents and physicians in India spanning a decade (2010–2019): An exploratory study using on line news portals and Google database. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 68(4), 718–728. https://doi.org/10.1177/00207640211011365

- Cheng, J., Kumar, S., Nelson, E., Harris, T., & Coverdale, J. (2014). A national survey of medical student suicides. Academic Psychiatry: The Journal of the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training and the Association for Academic Psychiatry, 38(5), 542–546. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-014-0075-1

- Dahlin, M., Joneborg, N., & Runeson, B. (2005). Stress and depression among medical students: A cross‐sectional study. Medical Education, 39(6), 594–604. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02176.x

- Dyrbye, L. N., Massie, F. S., Eacker, A., Harper, W., Power, D., Durning, S. J., Thomas, M. R., Moutier, C., Satele, D., Sloan, J., & Shanafelt, T. D. (2010). Relationship between burnout and professional conduct and attitudes among US medical students. JAMA, 304(11), 1173–1180. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.1318

- Dyrbye, L. N., Thomas, M. R., & Shanafelt, T. D. (2006). Systematic review of depression, anxiety, and other indicators of psychological distress among US and Canadian medical students. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 81(4), 354–373. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200604000-00009

- Dyrbye, L. N., Thomas, M. R., Massie, F. S., Power, D. V., Eacker, A., Harper, W., Durning, S., Moutier, C., Szydlo, D. W., Novotny, P. J., Sloan, J. A., & Shanafelt, T. D. (2008). Burnout and suicidal ideation among US medical students. Annals of Internal Medicine, 149(5), 334–341. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-149-5-200809020-00008

- Dyrbye, L. N., West, C. P., Satele, D., Boone, S., Tan, L., Sloan, J., & Shanafelt, T. D. (2014). Burnout among US medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general US population. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 89(3), 443–451. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000134

- Gentile, J. P., & Roman, B. (2009). Medical student mental health services: Psychiatrists treating medical students. Psychiatry , 6(5), 38–45.

- Hays, L. R., Cheever, T., & Patel, P. (1996). Medical student suicide, 1989–1994. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 153(4), 553–555. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.153.4.553

- Jahan, I., Ullah, I., Griffiths, M. D., & Mamun, M. A. (2021). COVID‐19 suicide and its causative factors among the healthcare professionals: Case study evidence from press reports. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 57(4), 1707–1711. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12739

- Jha, M. K., Mazumder, A., & Garg, A. (2014). Suicide by medical students–a disturbing trend. Indian Journals, 14(1), 40-42.

- Joanna Briggs Institute. (2023). Critical appraisal tools. Jbi.global. JBI. 2023. https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools

- Kaggwa, M. M., Najjuka, S. M., Favina, A., Griffiths, M. D., & Mamun, M. A. (2022). Suicidal behaviors and associated factors among medical students in Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports, 11, 100456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadr.2022.100456

- Kaltreider, N. B. (1990). The impact of a medical student’s suicide. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 20(3), 195–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278X.1990.tb00104.x

- Klein, H. J., & McCarthy, S. M. (2022). Student wellness trends and interventions in medical education: A narrative review. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 9(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01105-8

- Mamun, M. A., Misti, J. M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2020). Suicide of Bangladeshi medical students: Risk factor trends based on Bangladeshi press reports. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 48, 101905. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2019.101905

- O'Connor, R. C., & Kirtley, O. J. (2018). The integrated motivational–volitional model of suicidal behaviour. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 373(1754), 20170268. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2017.0268

- Oreskovich, M. R., Kaups, K. L., Balch, C. M., Hanks, J. B., Satele, D., Sloan, J., Meredith, C., Buhl, A., Dyrbye, L. N., & Shanafelt, T. D. (2012). Prevalence of alcohol use disorders among American surgeons. Archives of Surgery , 147(2), 168–174. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.2011.1481

- Page, M. J., Moher, D., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … McKenzie, J. E. (2021). PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 372, n160. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n160

- Pruthi, S., Gupta, V., & Goel, A. (2015). Medical students hanging by a thread. Education for Health , 28(2), 150–151. https://doi.org/10.4103/1357-6283.170129

- Ragab, E. A., Dafallah, M. A., Salih, M. H., Osman, W. N., Osman, M., Miskeen, E., Taha, M. H., Ramadan, A., Ahmed, M., Abdalla, M. E., & Ahmed, M. H. (2021). Stress and its correlates among medical students in six medical colleges: An attempt to understand the current situation. Middle East Current Psychiatry, 28(1), 75. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43045-021-00158-w

- Rockwell, F. R. A. N., Rockwell, D., & Core, N. (1981). Fifty-two medical student suicides. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 138(2), 198–201.

- Rotenstein, L. S., Ramos, M. A., Torre, M., Segal, J. B., Peluso, M. J., Guille, C., Sen, S., & Mata, D. A. (2016). Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA, 316(21), 2214–2236. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.17324

- Saipanish, R. (2003). Stress among medical students in a Thai medical school. Medical Teacher, 25(5), 502–506. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159031000136716

- Shanafelt, T. D., Sloan, J. A., & Habermann, T. M. (2003). The well-being of physicians. The American Journal of Medicine, 114(6), 513–519. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00117-7

- Simon, H. J. (1968). Mortality among medical students, 1947-1967. Journal of Medical Education, 43(11), 1175–1182. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-196811000-00012

- Singh, O. P. (2022). Increasing suicides in trainee doctors: Time to stem the tide!. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 64(3), 223–224. https://doi.org/10.4103/indianjpsychiatry.indianjpsychiatry_355_22

- Uchida, C., & Uchida, M. (2017). Characteristics and risk factors for suicide and deaths among college students: A 23-year serial prevalence study of data from 8.2 million Japanese college students. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 78(4), e404–e412. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.16m10807

- Watson, C., Ventriglio, A., & Bhugra, D. (2020). A narrative review of suicide and suicidal behavior in medical students. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 62(3), 250–256. https://doi.org/10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_357_20

- West, C. P., Huschka, M. M., Novotny, P. J., Sloan, J. A., Kolars, J. C., Habermann, T. M., & Shanafelt, T. D. (2006). Association of perceived medical errors with resident distress and empathy: A prospective longitudinal study. JAMA, 296(9), 1071–1078. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.9.1071

- Wilson, R., Varshney, K., Petrera, M., Hoff, N., Thiel, V., & Frasso, R. (2023). Reflections of Graduating medical students: A photo-elicitation study. Medical Science Educator, 33(2), 363–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-023-01758-3

- World Health Organization. (2021).) Suicide. Who.int. World Health Organization: WHO; 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide

- World Health Organization. (2022). Suicide mortality (per 100 000 population). Who.int. World Health Organization; WHO; 2022. https://data.who.int/indicators/i/16BBF41Xu

- Xu, Y., Chen, X., & Wang, K. (2017). Global prevalence of hypertension among people living with HIV: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Society of Hypertension: JASH, 11(8), 530–540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jash.2017.06.004

- Zivanovic, R., McMillan, J., Lovato, C., & Roston, C. (2018). Death by suicide among Canadian medical students: A national survey-based study.