ABSTRACT

Ensuring water security for a variety of users is fundamental for the wellbeing of the planet and humankind. To examine how we approach water planning and its value, we interpret water policy and management in Australia and Aotearoa-New Zealand from the viewpoint of the multiple related benefits it provides. Through a Modified Sphere of Needs Met by Water, we demonstrate the potential for an integrated approach to planning for the water cycle, where spiritual and cultural needs are considered iteratively with more utilitarian needs. We illustrate the working of the Sphere through historical and current cases of river dam development in Australia and Aotearoa-New Zealand, examining the potential for more sustainable utilitarian outcomes when spiritual and cultural values are given equal priority. We find integrating spiritual and utilitarian values could improve institutional design, provide for social cohesion, and could be a way of resolving conflicts relating to dams, common throughout the world.

Introduction

A sense of community disempowerment within environmental policy and management has led to a lack of trust in mainstream political process in settler-colonial states such as Australia and Aotearoa-New Zealand (NZ). Increasingly troublesome issues of environmental policy and management serve to demonstrate the lack of trust in mainstream political process (Berry and Jackson Citation2018; Newig and Rose Citation2020; O’Donnell et al. Citation2023). Slow and insipid responses to climate change issues are a case in point, as is a legacy of siloed approaches to water resource management. Water management calls for an integrated approach given interrelationships: upstream catchment management directly affects downstream water flows and water quality (Fenemor et al. Citation2011); surface water management directly influences groundwater (Abbott et al. Citation2019; Ross and Baldwin Citation2022); urban water management is directly impacting the receiving water environment (Vörösmarty Citation2010); and so on. These interdependencies are compounded by increasing extreme droughts, intense rain and exacerbated flood conditions (Becker Citation2021; Tingey-Holyoak, Pisaniello, and Burritt Citation2013). The way these interdependencies are managed has an effect on water uses and values, from community wellbeing to individual health and safety to the sustainability of food production and industrial processing (Garrick et al. Citation2017; Tingey-Holyoak, Fenemor, and Syme Citation2022).

This article assesses the potential for better approaching water policy and planning issues through addressing humanitarian and utilitarian needs met by water in an integrated, simultaneous, way. Through sustaining the cultural and spiritual values of water by providing sufficient quantity and quality of water to meet those needs, integrated management can also meet utilitarian needs: for example, making sure water can sustain spiritual relationships, language, stories, and the plants and animals associated with water, but also continue to supply drinking water and support recreational or commercial activities (AGI Citation2023).

Using historical and current cases of dam development on river systems in Australia and Aotearoa-NZ we highlight the opportunity for improving catchment and water planning from the perspective of spiritual and cultural benefits. We conclude that there is a pressing need to examine commonly held assumptions and philosophies about how we share and plan for water to ensure that the full potential range of benefits from our interaction with such a fundamental resource is maintained. We proceed by applying the lens of the Modified Sphere of Needs Met by Water or ‘Sphere of Needs’ (Syme et al. Citation2008) to consideration of historical factors about why and how we share water, and then four case studies to derive lessons for the future.

What are we sharing? Consideration of the range of human needs met by water

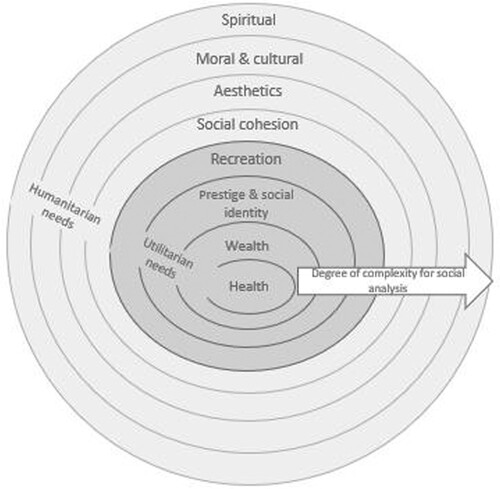

Water is a fundamental human need, and it is also crucial to all plant and animal life, most production processes and so has value to individuals, communities, businesses, and economies (Garrick et al. Citation2017; Ross and Baldwin Citation2022). Syme et al. (Citation2008) developed a Sphere of Needs to help understand the multifaceted benefits that can be delivered by water resources (). The model serves as a simple illustration of the wide variety of benefits that water has to society, to consider when water allocation and management decisions are made (see Gleick Citation1998).

Figure 1. Modified Sphere of Needs Met by Water (Syme et al. Citation2008).

The inner circles reflect the utilitarian uses of water and the outer circles reflect more humanitarian needs including the empowerment of communities. Complexity and diversity of needs increases towards the outer rings of the Sphere of Needs (Syme et al. Citation2008). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs assumed basic needs should be met to reach higher goals such as self-actualisation (Maslow Citation1954; Citation1993). Water planners have often adopted a similar stance (White Citation2020), assuming that wider benefits will ensue once the inner, utilitarian needs have been met. An important second assumption is that because the outer rings are challenging to quantify and driven by factors such as emotion and societal ideas of attachment and identity, they are too ephemeral to drive water planning and cannot be accounted for (Syme et al. Citation2008). For example, as well as utilitarian economic needs met by water represented by the inner rings, water-dependent ecosystems provide ecosystem services that often have uncosted utilitarian value, such as natural water filtration to maintain high water quality (Bark et al. Citation2011). Costing water quality services, for example, is what allows monetary value to be placed on the ecosystem services provided. But if there is calculation of value only from this perspective, there is a risk that the cultural and spiritual value that is placed on such ecosystem services is not considered at the same time (Garrick et al. Citation2017).

The UN/World Bank High Level Panel on Water’s Valuing Water Initiative in 2017 and the UN World Water Day 2021 highlighting raising awareness of valuing water (in its social, cultural, economic and environmental dimensions) and governance globally (Garrick et al. Citation2017; UN Citation2021). Important to both was recognition of needs represented in the outer rings of the Sphere of Needs: integrating the cultural significance of water and the sacred value it holds for human beings into water management and governance (Garrick et al. Citation2017; UN Citation2023). This movement has strong focus on the preservation and promotion of traditional Indigenous knowledge to better manage water resources. Examples of prioritising spiritual and cultural values are visible in the ways Traditional Owners value water in Australia which includes healthy people, healthy land, sovereignty and self-determination, with multiple utilitarian and humanitarian needs being met at the same time (Traditional Owner Partnership and Alluvium Citation2022) and in the Te Mana o te Wai legislated mandate for freshwater management in Aotearoa-NZ (NZ Government Citation2020). Through these approaches and Indigenous knowledge, we can change the current way we value and manage water (Nursey-Bray et al. Citation2014; O’Donnell et al. Citation2023; Taylor et al. Citation2021).

How are we sharing it? Utility has dominated

Utilitarian approaches had primacy in settler-colonial regimes, such as those of such as Australia and Aotearoa-NZ where water was harnessed to underpin development and the economy (Berry and Jackson Citation2018; Byrnes Citation2013; Johnson, Porter, and Jackson Citation2017; Knight Citation2016). Much political gain was seen in commissioning new dams or water infrastructure near election times (Connell Citation2007). In both countries, in this early-stage, engineers sometimes created a sense of urgency and supply crisis to fulfil their desire to build structures (Fenemor Citation1997; Troy and Holloway Citation2004). Such structures were seen as highly desirable to ensuring the appropriate standard of living expected in rich countries. Water planning was dominated by professionals such as engineers, land use planners and economists within institutions that largely followed British traditions (Porter Citation2016). Each department was run by their own professional specialists (Johnson, Porter, and Jackson Citation2017).

As the water industry matured and easy sites for dams became harder to find, water was increasingly seen as an economic good that had benefits other than irrigation and urban water supply (GDRC Citation1992). There was also competition from wider catchment demands. Exploitation was moving from run-of-river water takes, to groundwater takes and increasingly expensive water storage (NZ Hydrological Society Citation2021). Over-allocation to human use was seen to be causing environmental issues through exacerbating drought conditions and poor consideration of ecological needs (Hamblin Citation2009; Knight Citation2016; Syme, Nancarrow, and McCreddin Citation1999). There was a need to consider more than purely utilitarian considerations in water planning (Anderson et al. Citation2019). Nevertheless, it was tacitly assumed that if utilitarian needs were met, dealing with the wider considerations would naturally follow. The focus was on allocation of volume rather than of benefit (Syme and Nancarrow Citation2012). In 2004 the National Water Initiative was developed as a blueprint for national water reform, agreeing on commitment to ‘other’ public benefits provided by water (DCCEEW Citation2024). In 2023, Australia recommitted to renewing the 2004 National Water Initiative and included a committee on Traditional Owner interests and principles (DCCEEW Citation2024).

Indeed, the value of water to Indigenous people has only relatively recently been acknowledged and especially the deep spiritual significance attached to water by Indigenous communities who believe water to be a sacred and elemental source and symbol of life (Jackson Citation2005; Moggridge and Thompson Citation2021; Taylor et al. Citation2021; Blair Citation2023). Yet, Indigenous stakeholder input to decision-making was neglected until recent times when distinct Australian and Aotearoa-NZ national policies required Indigenous peoples’ participation in activities related to water planning and management (Bark et al. Citation2011; Taylor et al. Citation2021).

Despite historical and cultural differences between Traditional Owners of these countries and with Indigenous communities globally, core to Indigenous water management is the diverse ways of knowing that require reconnection of geographies, cultures and knowledge systems to overcome histories of dispossession and utilitarian approaches promoted through colonialism (Bates et al. Citation2023; Hartwig, Jackson, and Osborne Citation2020; Citation2022; Martuwarra RiverOfLife et al. Citation2021). Yet, water is also acknowledged to have some utilitarian value to contemporary Indigenous livelihoods and many Indigenous communities utilise aquatic resources to supplement or generate income, and Indigenous landowners and corporate organisations may have water entitlements (Bates et al. Citation2023; Hartwig, Jackson, and Osborne Citation2020; Citation2022; Taylor et al. Citation2021). Alongside renewed attention to the National Water Initiative (DCCEEW Citation2024) there is possibility for appropriate consideration of both outer and inner rings at the same time. So far, limited attention has been paid to how Indigenous communities can decolonise current approaches to water planning in Australia (Martuwarra RiverOfLife et al. Citation2021) and despite work on this in Aotearoa-NZ, how this can be operationalised (Taylor et al. Citation2021).

The consequences of prioritising utility: unpacking our beliefs

While the beliefs inherent in a utilitarian view of water may have been appropriate in the developmental phase of its management, it is apparent that they are not as suitable in the mature phase, especially in light of uncertainties exacerbated by climate change, increased environmental awareness, improved ecosystem knowledge and Indigenous rights (Jackson Citation2005). Furthermore, they ignore the many spatial, temporal, cross-scale and cross-sectorial interdependencies in water management. This is simply illustrated in the following summary of the key defining characteristics of pure utilitarian approaches:

Quantification: Water disputes are often framed in terms of allocation of litres of water, or the maximisation of profits measured in dollars of the alternative policies (Syme, Nancarrow, and McCreddin Citation1999). In a situation in which negotiations about water allocation are conducted between interest groups, the frame becomes one of winners and losers, easily measured as allocated litres. Thus, water disputes are reduced to a zero-sum game of winners and losers (Ruhl and Salzman Citation2019). This in turns leads to the psychology of loss (Kahneman and Tversky Citation1982) whereby the value of water loss is much more heavily weighted than water retention. In this case the negotiations become stalemated as ‘in-groups’ and ‘out-groups’ battle for attention. The situation is one of ‘win-lose’ rather than ‘win-win’ and the subtleties and opportunities from water sharing are lost. Most outer benefits such as culture and spirituality can often be recast as neo-liberal problems and redefined in terms of individual property rights or markets (Budds Citation2013). Such approaches can lead to a political economy of water centred on stakeholder lobbying and the theatre of populist politics (Syme, Nancarrow, and McCreddin Citation1999).

Time perception: Despite many texts and educational programs describing the need to manage the water cycle sustainably, there is little evidence that to this point institutions have succeeded in delivering on it (Flörke, Schneider, and McDonald Citation2018). Whilst individuals and groups who are proximate to the resource are those who are most well placed to plan for it, often political, economic, or social parties who are detached from the resource by time and space exert their power (Ostrom Citation1990). European concepts of linear time have dominated thinking in water resource planning (Loucks and Van Beek Citation2017). Economic modelling has estimated future demand in straight lines expressed as nett present value when deciding whether water developments are cost-effective. These approaches are not only inappropriate if one has a utilitarian view of water, but deficient if water management is to assist the functioning of the water cycle across time and space (Capra and Luisi Citation2014). First Nations and Māori culture provide a cyclical view of time (Knudsen Citation2004) which has the potential of defining and reinforcing the outer benefits while acknowledging the need for the more utilitarian inner needs at the same time.

Scale: Although solutions to water problems need to be integrated across macro, meso and micro scales, this can lead to conflict resulting from scale inconsistencies (Bates et al. Citation2023). For example, as water issues move from local/regional to basin/state level to the national/federal level, the individuals and groups included or excluded in the frame are dynamic which may result in winners and losers (Parsons, Fisher, and Crease Citation2021; Patrick, Syme, and Horwitz Citation2014). Similar scale issues arose with the introduction of water accounting through the Water Accounting Standards Board in Australia which suffered fundamental challenges for small scale and groundwater users in accessing data (Tello and Hazelton Citation2018; Tingey-Holyoak and Pisaniello Citation2019). Scale issues are also arising with the setting of national ‘bottom-line’ water quality standards in Aotearoa-NZ (Fenemor Citation2017), where, for example, exemptions from water quality standards are provided for specific growing areas deemed nationally important (NZ Government Citation2020). Consideration of improving benefits across rings in the Sphere of Needs that accounts for multiple scales could also help support more participative management.

The advantages of integrating outside needs

While water management often prioritises utilitarian values, the UN High Level Panel on Water recognised in its Bellagio Principles on Valuing Water in 2017, that water has multifaceted values that vary by stakeholders (UN Citation2017). Water can heal, cleanse, purify or bring blessings and so there is a need to consider water from beyond an economic perspective and to encompass the spiritual and sacred values that many communities attribute to water (UN Citation2021). The spiritual needs met by water in the outer Sphere are very present in Indigenous communities today. For the Wayuu people in Columbia, water is a living being at the heart of traditional rituals and ceremonies (Ulloa Citation2020). For Hindus, the river Ganges is considered sacred (Blair Citation2023; Zara Citation2015). For the Ngarrindjeri people along the lower Murray-Darling in Southern Australia, cultural and spiritual wellbeing is inextricably linked with sustainable land use and water flows (Birckhead et al. Citation2011). For the Māori of Aotearoa-NZ, there are inseparable ties to their water for every iwi in a rohe (tribal territory) as the essence of life, significant for spiritual health and healing (Taylor et al. Citation2021).

Through the rise of informal public input into resource management and the demands for more holistic planning, the outer parts of Sphere of Needs have started to come into focus (e.g. Grillos, Zarychta, and Nunez Citation2021). In Australia and Aotearoa-NZ, we have the advantage of diverse Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and Māori cultures which sees humanity embodied in an environment with mutual obligations to nurture (see O’Donnell et al. (Citation2022; Citation2023) and Robson-Williams, Painter, and Kirk (Citation2022)). The spiritual and wellbeing effects of conservative management of the environment, especially water, for all in the community are now understood. If these advantages are realised long term water management can more sustainably support communities from the ‘outside-in’.

To do so we will need to consider the need for holistic means of evaluating the effects of water management policies. This requires thinking beyond typical jurisdictional or physical boundaries (Ross and Baldwin Citation2022) and is influenced by the overarching frame within which the water system and the community around it operate. It also requires culturally appropriate and place-based tailored solutions for regionally specific cultural values (Jackson Citation2005). This includes Indigenous water values of viewing land and water holistically, linking social, ecological, and biological systems with cultural practices; the importance of sufficient and quality water for the health of the land and food systems (Jackson Citation2005; Te Aho Citation2019).

The utilitarian benefits need not be compromised, and one way forward is for all rings of the Sphere of Needs to be approached in an iterative way. In the following section we provide further examples of water management issues amenable to this approach.

Methods

Desk-based case studies were chosen as a demonstration of a significant water issue that affects many different users with different needs. We initially chose a wide set of case studies, including dam development, irrigation utilities, and specific regional cases. However, as the research progressed, the cases that provided the most stability of data and comparison across time and location were in dam development (Riege Citation2003). The research team had significant prior experience with dam planning research globally, but in particular Australia and Aotearoa-NZ. Furthermore, dam development for irrigation and other regimes is fraught with tension everywhere around the world (Berry and Jackson Citation2018; Blair Citation2023). Australia and Aotearoa-NZ were purposefully chosen as desk-based case study locations, with different histories between First Nations people in Australia and the Māori in Aotearoa-NZ in terms of cultural reconnection and Indigenous sovereignty.

Aotearoa-NZ is home to 892,200 Māori making up 17 per cent of the population (StatsNZ Citation2023). The Treaty of Waitangi was signed on 6 February 1840 but differences in interpretation between government and the Māori saw governments confiscating land. Resistance to this resulted in the New Zealand Wars from 1845 at 1872 (Jones Citation2000). Policies of significant negative impact included the Tohunga Suppression Act 1907 relocating Māori tribes from their traditional lands and removing them from their traditional food and water sources (Archibald Citation2006), decimating the connection of the Māori with their land and water. Australia is home to 745,000 First Nations people making up three per cent of the population (IWGIA Citation2023). Australia was also colonised by England; however, there was and remains no treaty with First Nations people. Catastrophic policies included in all states, except Tasmania, Chief Protectors or a Protection Board being given power over Indigenous people from 1911, including in some cases the power to remove them from their traditional lands to reserved lands (Archibald Citation2006). Since then, disconnection with water has prevailed under settler colonial water planning regimes that are only relatively recently being given attention.

Whilst Indigenous people are culturally diverse and do not share homogenous traditions and practices, colonisation in both countries functioned to disempower and disconnect Indigenous relationships with land and water (Archibald Citation2006). At community levels, there is some evidence that culturally appropriate healing interventions are effective when rooted in connection to the land and water (Boot and Lowell Citation2019; Te Aho Citation2016).

Choice of dam development as a case in water planning

The choice of dam development for desk-based case studies followed reflection on how dams related to different needs in the Sphere. The construction of dams has provided a more reliable source of water for communities and business but disrupted the natural flow cycle needed for healthy rivers and wetlands.

Ongoing construction of large dams is still considered by some as an optimal option to meet future increases in water, food, and energy demands, which may be crucial to meet basic human needs as well as sustain economic development (Loucks et al. Citation2017). Large dams are important for generating electricity and irrigation, but they often severely modify river hydrology and geomorphology and thus impact downstream communities and aquatic environments (Wishart et al. Citation2020).

Dam development, large and small, can go straight to the heart of contemporary water resources conflict, to identify where in the Sphere stakeholders see the needs to be met by water. Depending on where the needs are, dams can be viewed as blockages of a living holy being or the source of power for cities and irrigation for essential food production (Fisher Citation2010). Indeed, construction of large dams in many places has historically been met with excitement and resistance, sometimes in equal measure (Berry and Jackson Citation2018; Blair Citation2023).

The value created from the construction of large dams can be considered to vacillate between rings of the Sphere of Needs depending on perceptions of the economic, social, and environmental benefits and impacts. Large dam development can be viewed as working from the inner rings as an efficient means to store critically needed water, to produce electricity, and to control the flow of rivers but can also be viewed from the outer rings as having extremely negative environmental and social impacts (Fisher Citation2010). There is also an increasing interest in restoring social and economic values through the decommissioning or alteration of large dams which is not without negative impacts also (Hammersley, Scott, and Giullett Citation2018).

The International Commission on Large Dams (ICOLD), the leading association of the $20 billion per year dam industry, estimates that the world’s rivers have been reshaped and regulated by means of more than 40,000 large dams since the 1950s (Wishart et al. Citation2020). Worldwide, reservoirs created by dams are estimated to have a combined storage capacity of 10,000 cubic kilometres, equal to five times the volume of water in all the rivers in the world (Fisher Citation2010). The human consequences of large dams are even more dramatic than the ecological consequences, that are well known. Empirical evidence shows the social disruption is significant, with vast impacts from disrupted downstream habitats and life cycle cues for fish and other river species, as well as fishing, cropping and grazing systems that rely on flood-plain ecosystems (Richter et al. Citation2010).

Choice of specific case study locations

We demonstrate some of the issues related to the Sphere of Needs through historical and contemporary dam development case studies in Australia and Aotearoa-NZ. Many New Zealand rivers are modified by large water storage development projects for hydroelectricity, irrigation, water supply, industrial purposes and flood protection (Gluckman et al. Citation2017). In many parts of the world, including Aotearoa-NZ, the driver of dam development is hydroelectricity, which makes this very relevant as a case study location. Hydro-electric power schemes use 16–33 per cent of New Zealand’s total water resources (Young, Smart, and Harding Citation2004). Such large water projects have caused dramatic changes to the seasonal pattern of flows, the strength of the connection between the mountains and the sea, and the ability of a river to carry sediment and dilute contaminants – all affecting the mauri or life-essence of a river (Young, Smart, and Harding Citation2004).

In Australia, large dams in the south of the country provide 75 per cent of Australia’s total annual water use (CSIRO Citation2014). The history of dams goes back thousands of years. Dam construction, traditionally dug with wooden tools, has been a water storage method used by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and is still used today in some areas (Bayley Citation1999). But the history of large in-river dams (those measuring 15 metres or more from foundation to crest) spans only the past six decades. Most dams were constructed between 1955 and 1980 and have resulted in greatly reduced inflows to many reservoirs and systems, exacerbating conflict between upstream and downstream users and those advocating for the restoration of cultural or environmental flows. In Australia, large dam development historically and currently faces many questions about how humanitarian and utilitarian needs can be considered adequately together (e.g. Hart, O’Donnell, and Horne Citation2019), making Australia also relevant as a demonstration case for many parts of the world.

Australia

Australia is one of the many places around the world where there has been a growth in the construction of large dams in recent times. In Australia, the primary interest is in the construction of new large dams for meeting the utilitarian needs of supply of water for irrigation in the relatively undeveloped northern half of Australia and securing a reliable supply of water for regional cities and towns and existing irrigation areas (McMahon and Petheram Citation2020; Petheram et al. Citation2014).

Historical case – Gordon-below-Franklin Dam, Tasmania

We firstly explore dams through the case of Gordon-below-Franklin Dam in Tasmania. This case study examines the proposal in 1979 by the Hydro-Electric Commission of Tasmania to build a dam on the Gordon River below the Franklin River.Footnote1 The dam was to provide a substantial increase in the production of electricity, accounting for some 21 per cent of the state’s supply. This proposal resulted in political turmoil with alternative dam proposals being advanced by the state opposition and the upper house (the Legislative Council) (see Twomey Citation2017 for a fuller description of this very tumultuous period of Tasmanian politics).

The problem for the Tasmanian government was that the Gordon River was perceived by many in the Tasmanian community to have highly significant cultural and conservation value, so the water was very much meeting the outer needs of the Sphere. An impassioned protest led by local conservationist Bob Brown in a Tasmanian protest morphed into a nationwide movement, ultimately resulted in the founding of the Tasmanian Greens political party. In 1982 the federal Labor party at its national conference adopted a No Dams policy and subsequently campaigned nationally to achieve this aim. Once elected, the Labor government was obliged to use its coercive powers, if possible, to stop the construction of the Dam if it could not come to an agreement with the Tasmanian government. Since it could not come to an agreement, the Commonwealth government was successful in the High Court in it granting legitimacy for the Commonwealth government to use its reserve powers over the state to prevent construction.

Three considerations relating to the outer rings of the Sphere of Needs were pivotal to the decision. These were:

human rights demonstrated through the adherence to international agreements and Australia’s commitment as a good, international citizen,

an early and powerful recognition expression of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture in terms of attachment to a specific environment and

at least a tacit recognition that the natural environment contributes to national human wellbeing (O’Donnell et al. Citation2022).

In short, the decision was made by the High Court at least substantially, from the perspective of the outer rings of the Sphere of Needs.

One can only speculate more than thirty years on as to whether this was a good decision or not. Certainly, the local Tasmanian community did not think so at the time as Labor lost all five Tasmanian seats in the 1983 Federal election. Times have changed and renewable energy in the context of climate change is a valuable commodity. Nevertheless, the fundamental benefit of the decision and others starting from the outside is that there are no opportunity costs. That is, if our values change the resource is still available. It is also worthy of note that tourism associated with preservation also provides utilitarian as well as environmental and cultural benefit for many Australians. The long-term productivity gains and community empowerment from cultural and individual sense of attachment and identity are irreplaceable.

Contemporary case – northern territory dam development

More recently, the case of dams in Northern Australia is evolving and could be supported by more active consideration of elements of the Sphere of Needs. The plans to grow Northern Australia’s population and industry means that it requires more water. Plans for new dams and storage facilities to capture floodwaters from local river systems in the range of hundreds of thousands of megalitres have been proposed for many years. The federal government has been supporting such initiatives through schemes such as the $5 billion Northern Australia Infrastructure Facility and a National Water Infrastructure Development Fund. A two-and-a-half-year CSIRO study examined the potential of four large dams in Far North Queensland’s Mitchell River catchment and two dams on the Northern Territory’s Adelaide River. The report estimated enormous inner benefits, including expanded agricultural development that could create up to 15,000 jobs and generate $5.3 billion annually – including a $2.6 billion economic boost to Darwin (Petheram et al. Citation2018). Specifically, a dam diverting the Adelaide River in the Northern Territory, called the Adelaide River Offstream Water Storage project could have immense inner need-meeting potential, such as up to 1400 jobs in farming activity, 500 jobs in mining and support up to 90,000 ha of dry-season horticulture and mango trees (Petheram et al. Citation2018).

However, over many years Traditional Owners and native title holders have resisted attempts at damming in the Northern Territory (see O’Donnell et al. Citation2022). The CSIRO study also found that some of the catchments where the 128 projects were assessed only had 1500 people living in them and many of these contain Indigenous communities who fear great disempowerment. The Northern Territory has the highest proportion of Indigenous people of any Australian jurisdiction (O’Donnell et al. Citation2022). Jackson and Barber (Citation2016) note primarily how Indigenous engagements with water are dynamic and contextually contingent, with attitudes and values shaped by diverse pre-existing water histories (Hart, Horne, and O’Donnell Citation2016). They are not fixed and stagnant in a non-natural structure, like a dam. Dams can contrast with the natural geographical variation and can create a new landscape with new values that change the scope of public debates or decisions about dams. If the outer needs met by water are not very carefully valued, by changing the water landscape, the geographies change, and communities can become disempowered (Owens et al. Citation2022).

The historical approaches of the Gordon-Below-Franklin Dam were largely focused on the inner rings of the Sphere of Needs. A mid-range approach was finally met when the High Court blocked the project, fostering economic value through tourism. Through this decision, moral and cultural rings of the Sphere became the working area, rather than health and wealth, which was the original aim of dam development. In more recent times, there also appears to be consideration of moral and cultural needs in Northern Territory dam development planning, however the focus on wealth and the boost for the prestige of the region are no doubt apparent. A more coordinated and iterative approach that includes working from outer rings with greater involvement of First Nations communities and more coordinated, transparent and integrated process has been proposed but whether that will prevail is yet to be seen (Hart, O’Donnell, and Horne Citation2019).

Aotearoa-NZ

It is important to provide water management context to dam development cases in Aotearoa-NZ. The new underpinning concept to Aotearoa-NZ water management, Te Mana o te WaiFootnote2, imposes a hierarchy of obligations that prioritise the health and well-being of water first, the health needs of people second, and the ability of people and communities to provide for their social, economic, and cultural well-being third. As a further example, the government now recognises the Whanganui River as a legal person, having the same rights and responsibilities as a human person (Cheater Citation2018; Taylor et al. Citation2021). The Waitangi Tribunal, created in 1975, provided an avenue for the Whanganui Iwi to establish their relationship with the river legally (Cheater Citation2018). These are shifts in thinking that put the health of the water first (Our Land and Water NZ Citation2020).

Water policy is currently evolving to apply Indigenous management concepts to all water bodies (Robson-Williams, Painter, and Kirk Citation2022). Work is now under way with iwi and hapū to explore what Te Mana o te Wai means for them culturally and spiritually in order to create tools, guidance, and support for all users of water in Aotearoa-NZ where many are struggling to understand and give effect to this mātauranga Māori centred concept (Our Land and Water NZ Citation2020). So, in this sense the concept of Te Mana o te Wai seems to be working outside-in on the Sphere of Needs (Syme et al. Citation2008). However, to advance the working of the Sphere, the needs of water itself need defining, potentially relating to freshwater ecosystem health (defined in the NPSFM 2020) alongside spiritual and cultural values, and may well even include ideas of sense of attachment to the water body. Then the Sphere of Needs could be applied to decide the quality and quantity of water available for human health (inside needs), followed by the wellbeing of people socially and culturally (outside needs), then economic wellbeing (inside needs). Then there are needs that can be met concurrently by giving the water primacy. This reconceptualising of how we empower communities by concurrently empowering the water source is a somewhat radical idea. As proposed by Taylor et al. (Citation2021), such an approach requires mapping the needs of the water, and necessarily reframes environmental governance to stimulate more caring attitudes to water whilst also meeting both inner and outer human needs concurrently – to enhance health and protect mana (spiritual power, authority, prestige) of communities.

The legal framework above stems from the intrinsic spiritual values of an Indigenous belief system for the first time. And yet in the case of the Whanganui River, despite the river’s new legal status, there are still challenges created by existing large dams (Lurgio Citation2019). Whilst the power company only diverts a relatively small proportion of the water of the Whanganui River, this is still causing cultural and spiritual damage for local iwi (Lurgio Citation2019). The new law does not reverse pre-existing laws, including Genesis Energy Ltd.’s right to divert water until 2039. The conflict between utilitarian needs and spiritual and cultural needs met by water is a fine balance for the country of nearly five million people. The following section will consider a historical and contemporary case of dams in Aotearoa-NZ.

Historical case – Waitaki River Dams

The Waitaki River is a major river on the South Island; its catchment is the third largest in Aotearoa-NZ. The Waitaki River drains the central mountains of the South Island to the Lindis Pass. It now powers the turbines of multiple power stations and like other rivers dammed for hydroelectricity, its flow variability has been reduced (Knight Citation2016). This damming was in place before recognition of cultural values was mandated and the impact of hydro dam development on traditional Māori taonga was ignored (Macpherson and Clavijo Ospina Citation2018; Morris and Ruru Citation2010; Te Aho Citation2016). In 1925 the South Island needed more electricity to sustain an expanding population and engineers started work on the 36 m-high Waitaki Dam (Morris and Ruru Citation2010).

The Waitaki Dam provided residents great utilitarian benefit through electricity. It also led to the development of the 110m high Benmore Dam completed in 1965, followed by the Aviemore Dam completed in 1968 (Bloomberg Citation2001). Between 1970 and 1985 water from Lakes Tekapo, Pukaki and Ohau was diverted through a series of four low-head dams. This made the upper Waitaki development scheme the largest of its kind in the world and resulted in significant employment and revenue for the region (Bloomberg Citation2001). The retail value of the power generated on the Waitaki is estimated to be $700 million per year (Bloomberg Citation2001). There is also significant agricultural production and the spread of irrigation especially for dairying. However, the utilitarian needs met resulted in significant environmental, cultural and spiritual loss, including the extinction of several species of native birds, eels and fish, river iwi (tribes) being unable to gather important food species, knowledge about species and fishing practices not being passed down to whanau, a loss of connection between youth and the elders who possessed such knowledge, and loss to language as names of different species, and different stages of their lifecycles, were no longer spoken (Te Aho Citation2016).

A long search for redress seemed to begin in 1975 with the establishment of the Waitangi Tribunal, which allowed for Māori people to seek redress and make a claim for any harm caused and to take control of the fishing grounds around the dams in accordance with their traditional culture (Te Aho Citation2016; Ruru Citation2013).

Contemporary case – far North iwi Te Rarawa

Te Rarawa is a Māori iwi of Aotearoa-NZ’s North Island. The iwi is one of the six Muriwhenua iwi of Northland (National Library Citation2023). In 2020 Far North iwi group Te Rarawa built a dam to mitigate the effect of droughts and allow pasture to be converted to horticulture to create jobs for the region’s Māori community (De Graaf Citation2020). The project received $3 million from the Provincial Growth Fund and the dam holds 350,000 cubic metres of water, diverted from the flood prone Awanui River. The iwi project is low impact, primarily utilising existing infrastructure and the natural land formation to create low-cost off-stream water storage. The project was established to protect the local community from the increasing severity and frequency of droughts, and enables a reliable water supply which stores water from the wet months for both cultural and community economic resilience. Furthermore, staying connected to the needs of the water-dependent ecosystem, Te Rarawa intends to harvest water during peak flows and store it for use during dry periods (De Graaf Citation2020). The iwi in this case is leading the planning of project in a way that meets their utilitarian needs but will also integrate spiritual and cultural needs.

Historically, health, wealth and prestige were the focus of dam development, very firmly embedded in the inner rings of the Sphere of Needs. Today, Aotearoa-NZ dam development has what appears to be a highly integrated approach, where iwi-led planning means that health and wealth can still be considered as inner rings, but that moral and cultural needs are also considered, exemplifying an integrated approach to balancing the needs met by water. The legislative moves to recognize Indigenous values and incorporate humanitarian values into decision-making related to fresh water (NZ Government Citation2020) demonstrate how far Aotearoa-NZ has progressed as a nation in dealing with some very complex issues arising from inner and outer parts of the Sphere of Needs. Nevertheless there has been negotiated compromise, which has been a painful process, but these show that it is possible to work from the outer rings of the Sphere of Needs whilst still acknowledging the inner ones.

Discussion and conclusion

Cases from the large dams in Tasmania and Northern Australia demonstrate the risks of a focus on the inner, utilitarian needs. Examples of ways of thinking from new approaches to fresh water in Aotearoa-NZ provide a contrast. Cases demonstrate that coming from different parts of the Sphere of Needs is largely inevitable. What is needed however, is somehow to integrate the economic values of power production, irrigation and drinking water, drought protection etc (inner rings) with the protection of cultural, environmental and spiritual values (Bark et al. Citation2011).

The proposed damming in Northern Australia provides a live example of how complex the decisions are and how potentially interwoven some of the inner and more outer, humanitarian needs are. In the NT, Indigenous water planning, recognising the relationship of environmental health to well-being, means outer needs are of prime consideration. The case of Aotearoa-NZ demonstrates how policy can take this to the next level by including the needs of the water as an underpinning management concept, in addition to setting the precedent of giving a body of water the ultimate empowerment through legal personhood – at least for one river – and for co-management (Geddis and Ruru Citation2019; Macpherson and Clavijo Ospina Citation2018; O’Donnell et al. Citation2023).

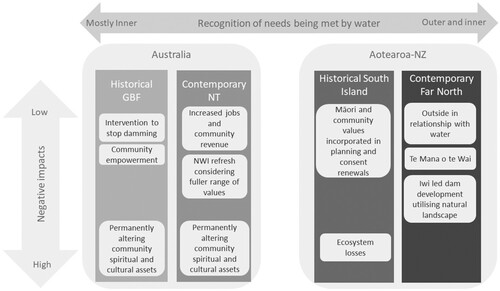

In 2017 Australia also passed its first legislation that recognized a river (the Birrarung/Yarra River) as a living entity, formally recognising the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung people as Traditional Owners (O’Donnell et al. Citation2023). Whilst this points toward more holistic river management, proposals for new dams continue and remain contentious. A trend toward reliance on market mechanisms to resolve competing uses has meant access to water has been formalised and separated from land titles, and water for those entitlements can now be bought and sold separately from land. Water markets cannot achieve the goals of the outer rings of the Sphere of Needs without adequate underpinning regulation, including political processes for decision-making. Water markets can provide a method for re-allocating scarce water to maximise economic benefits, but this needs to be regulated in a manner which simultaneously provides for the values represented by the outer rings of the Sphere. Renewed attention to the ‘other’ public benefits in the National Water Initiative and focus on Traditional Owner interests could provide a path forward. In Aotearoa-NZ challenges still exist with dams that were developed in the past, however new approaches to community led water storage that enhance and work with the natural landscape to protect the Aotearoa-NZ communities from climate change provide one exemplar of empowerment through integrating humanitarian and utilitarian values. highlights how the different ways of valuing the inner and outer needs met by water can have different outcomes in terms of community empowerment, including the specific elements that pertain to each case.

Figure 2. Cases mapped against different degrees of inner and outer need integration and resulting potential for negative impacts.

serves to highlight the persistence of issues of dams in Australia and the altering of water assets that have significant spiritual meaning and the negative impacts that can result. Despite community empowerment in the historical case in Australia, the examples largely show potential for negative impacts when mostly inner rings of the sphere are considered. The development of policy based on Māori values in Aotearoa-NZ, in addition to the significance of the beginnings of legal empowerment of water, have the potential for fewer negative impacts when the outer and inner needs of the Sphere are being met.

We are not saying that inclusion of First Nation flows is merely dealing with the outer, cultural and spiritual rings of the Sphere of Needs. Rather we are arguing that by meeting these we will gain new opportunities for water managers and institutional design to deal with the wider public good. Working in an integrated way between outside and inside needs and considering cultural and spiritual needs as fundamental – whether Indigenous or local community needs – provides new opportunities to positively impact other more utilitarian benefits as well and indeed could be a solution for improved water planning.

It must be noted that these cases are not designed to form a comparison of the two countries original inhabitants’ approaches and needs. Water has enormous cultural importance for both nations. For Māori, it acts as a link between the spiritual and physical worlds, and the wellbeing of an iwi is linked to the condition of the water. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people water is core to life and protecting and managing water is a custodial and intergenerational responsibility (AGI Citation2023). It is important to again note that there are significant historical contrasts and distinctions within each country – affecting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and Māori groups, each of which have their own cultural norms, dialectal groups, water values and hopes for and approaches toward decolonial water futures (Martuwarra RiverOfLife et al. Citation2021).

Nevertheless, the issue for dam development in both countries continues to be daunting. Can we try to prioritise the outer rings of the Sphere of Needs when planning projects through participatory design? How can states and land districts meet the needs of disparate populations within their jurisdictions? How can competing cultural and environmental concerns be met? How can accounting frameworks that support spiritual or Indigenous valuation approaches which emphasise the spiritual dimension of water best be utilised?

Use of the Sphere of Needs by planners could assist as a preliminary high-level ‘check-in’ tool to ensure officials are acting not just from utilitarian needs, out to humanitarian needs, as final ‘last thought’ considerations. To integrate these outer needs requires deeper more qualitative understanding and involvement of Indigenous people as well as the range of stakeholders, fostering community empowerment. However, planners could use the tool early in the planning process to better integrate humanitarian needs with utilitarian needs to help guide the deeper analysis required to address the many spatial, temporal, cross-scale and cross-sectorial interdependencies in water management. Initial check-in with the Sphere of Needs could also serve to ensure that scarce financial resources are not just targeted at the water systems that are demonstrating stress on the inner rings – that high value culturally and spiritually stressed water systems are also prioritised, and these communities empowered, as are intergenerational sustainability. However, extensive regionally sensitive analysis would then be required through an applied culturally-fit accounting tool designed to develop and assess specific cultural and spiritual indicators for a particular water system (see Nursey-Bray and Arabana Aboriginal Corporation Citation2015; Nursey-Bray and Palmer Citation2018). Supported by rich qualitative data and notes, the UN’s System of Environmental and Economic Accounting–Ecosystem Accounting (SEEA-EA) holds potential as an organising framework, and is beginning to be applied in collaboration with Indigenous communities (see Normyle, Vardon, and Doran Citation2022). The power of the framework for addressing Indigenous water values is that it would allow for wider understanding across contexts and encourage investment in Indigenous-designed and led restoration and adaptation projects (Nursey-Bray and Palmer Citation2018).

This article focuses our attention on different ways that water planning can be approached and what that means for individuals, communities, and environments. We suggest that an integrated approach that gives equal priority to spirituality and cultural values provides an opportunity to positively impact the other needs met by water and as such benefits the entire population. Aiming to meet these needs could improve institutional design, provide for social cohesion, and potentially improve sustainable utilitarian outcomes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 This is a highly truncated summary of a conflict that had many nuances: legal, political and in terms of the willingness of the community to defend their environment and culture. The reader is directed to Coper, Roberts, and Stellios (Citation2017), for a more detailed review and interpretation of the Gordon Dam case.

2 Te Mana o te Wai is the new approach to Aotearoa-NZ water management under the National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management, enacted in 2017 and updated in 2020 (NZ Government Citation2020). However, at the time of writing, the new National-led NZ government has stated they will review the NPSFM including Te Mana o te Wai (Beehive, Citation2024).

References

- Abbott, B. W., K. Bishop, J. P. Zarnetske, C. Minaudo, F. S. Chapin, S. Krause, and G. Pinay. 2019. “Human Domination of the Global Water Cycle Absent from Depictions and Perceptions.” Nature Geoscience 12 (7): 533–540. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-019-0374-y.

- Anderson, E. P., S. Jackson, R. E. Tharme, M. Douglas, J. E. Flotemersch, M. Zwarteveen, C. Lokgariwar, et al. 2019. “Understanding Rivers and Their Social Relations: A Critical Step to Advance Environmental Water Management.” WIRES Water 6 (6): 1381. https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1381.

- Archibald, L. 2006. Decolonization and Healing: Indigenous Experiences in the United States, New Zealand, Australia and Greenland. Ottawa: Aboriginal Healing Foundation. https://epub.sub.uni-hamburg.de/epub/volltexte/2009/2898/pdf/deconolization.pdf.

- Australian Government Initiative (AGI). 2023. Australian and New Zealand Guidelines for Marine and Freshwater Management: Cultural Values, Water Quality, https://www.waterquality.gov.au/anz-guidelines/guideline-values/derive/cultural-values.

- Bark, R., D. H. MacDonald, J. Connor, N. Crossman, and S. Jackson. 2011. Water Values. Canberra, Australia: Water Science and Solutions for Australia. https://www.csiro.au/en/research/natural-environment/water/water-book/water-values.

- Bates, W. B., L. Chu, H. Claire, M. J. Colloff, R. Cotton, R. Davies, … R. Q. Grafton. 2023. “A Tale of Two Rivers–Baaka and Martuwarra, Australia: Shared Voices and Art Towards Water Justice.” The Anthropocene Review. https://doi.org/10.1177/20530196231186962.

- Bayley, I. A. E. 1999. “Review of How Indigenous People Managed for Water in Desert Regions of Australia.” Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia 82: 17–25.

- Becker, P. 2021. “Fragmentation, Commodification and Responsibilisation in the Governing of Flood Risk Mitigation in Sweden.” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 39 (2): 393–413. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654420940727.

- Beehive. 2024. “Government Takes First Steps Towards Pragmatic and Sensible Freshwater Rules”, Beehive.govt.nz. https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/government-takes-first-steps-towards-pragmatic-and-sensible-freshwater-rules.

- Berry, K. A., and S. Jackson. 2018. “The Making of White Water Citizens in Australia and the Western United States: Racialization as a Transnational Project of Irrigation Governance.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 108 (5): 1354–1369. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2017.1420463.

- Birckhead, J., R. Greiner, S. Hemming, D. Rigney, M. Rigney, G. Trevorrow, and T. Trevorrow. 2011. Economic and Cultural Values of Water to the Ngarrindjeri People of the Lower Lakes, Coorong and Murray Mouth. River Consulting: Townsville.

- Blair, H. 2023. “Saving India’s Rivers: Ecology, Civil Society, Religion, and Legal Personhood.” World Development Sustainability 3: 100068.

- Bloomberg, S. 2001. “Waitaki: Water of Tears, River of Power.” New Zealand Geographic, Issue 051 May, June 2001. https://www.nzgeo.com/stories/waitaki-water-of-tears-river-of-power/.

- Boot, G. R., and A. Lowell. 2019. “Acknowledging and Promoting Indigenous Knowledges, Paradigms, and Practices Within Health Literacy-related Policy and Practice Documents Across Australia, Canada, and New Zealand.” The International Indigenous Policy Journal 10 (3). https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/iipj/vol10/iss3/2.

- Budds, J. 2013. “Water, Power, and the Production of Neoliberalism in Chile, 1973–2005.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 31 (2): 301–318. https://doi.org/10.1068/d9511.

- Byrnes, J. 2013. “A Short Institutional and Regulatory History of the Australian Urban Water Sector.” Utilities Policy 24: 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jup.2012.09.001.

- Capra, F., and P. L. Luisi. 2014. The Systems View of Life: A Unifying Vision. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cheater, D. 2018. “I am the River, and the River is Me: Legal Personhood and Emerging Rights of Nature.” West Coast Environmental Law. https://wcel.org/blog/i-am-river-and-river-me-legal-personhood-and-emerging-rightsnature?msclkid=c86a5292aefe11ec99b5ffa299ae9ee7.

- Connell, D. 2007. Water Politics in the Murray-Darling Basin. Canberra: Federation Press.

- Coper, M., H. Roberts, and J. Stellios. 2017. The Tasmanian Dam Case: 30 Years On: An Enduring Legacy. Armidale: The Federation Press.

- CSIRO (2014). Northern Rivers and Dams: A Preliminary Assessment of Surface Water Storage Potential for Northern Australia, CSIRO Land and Water Flagship Technical Report. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.4385.2960.

- De Graaf, P. 2020. “Far North iwi Te Rarawa Launches Wáter Storage Project to Boost Jobs, Fend off Droughts.” NZ Herald, 22 June 2020. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/northern-advocate/news/far-north-iwi-te-rarawa-launches-water-storage-project-to-boost-jobs-fend-off-droughts/OIDID754GABHPKBZOMICVMMZGY/.

- Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW). 2024. National Water Initiative. https://www.dcceew.gov.au/water/policy/policy/nwi#toc_0.

- Fenemor, A. D. 1997. “Floods and Droughts: Case Studies.” Chapter 11 in Floods and Droughts – the New Zealand Experience, New Zealand Hydrological Society, 187–201. Richmond, New Zealand: Caxton Press.

- Fenemor, A. D. 2017. “Water Governance in New Zealand – Challenges and Future Directions.” New Water Policy & Practice 3 (1): 9–21. https://doi.org/10.18278/nwpp.3.1.3.2.2.

- Fenemor, A. D., C. Phillips, W. J. Allen, R. G. Young, G. R. Harmsworth, W. B. Bowden, L. Basher, et al. 2011. “Integrated Catchment Management – Interweaving Social Process and Science Knowledge.” New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 45 (3): 313–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/00288330.2011.593529.

- Fisher, W. F. 2010. “Going Under: The Struggle Against Large Dams”, April 2, 2010. https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/going-under-indigenous-peoples-and-struggle-against-large.

- Flörke, M., C. Schneider, and R. I. McDonald. 2018. “Water Competition Between Cities and Agriculture Driven by Climate Change and Urban Growth.” Nature Sustainability 1 (1): 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-017-0006-8.

- Garrick, D. E., J. W. Hall, A. Dobson, R. Damania, R. Q. Grafton, R. Hope, C. Hepburn, et al. 2017. “Valuing Water for Sustainable Development.” Science 358 (6366): 1003–1005. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao4942.

- Geddis, A., and J. Ruru. 2019. Places as Persons: Creating a New Framework for Māori-Crown Relations. Melbourne, Australia: The Frontiers of Public Law (Hart Publishing).

- Gleick, P. H. 1998. “Water in Crisis: Paths to Sustainable Water Use.” Ecological Applications 8 (3): 571–579. https://doi.org/10.1890/1051-0761(1998)008[0571:WICPTS]2.0.CO;2.

- Gluckman, P., A. Bardsley, B. Cooper, C. Howard-Williams, S. Larned, J. Quinn, … D. Wratt. 2017. New Zealand’s Fresh Waters: Values, State, Trends and Human Impacts. Auckland, New Zealand: Office of the Prime Minister’s Chief Science Advisor.

- GRDC. 1992. “The Dublin Statement on Water and Sustainable Development.” https://www.gdrc.org/uem/water/dublin-statement.html.

- Grillos, T., A. Zarychta, and J. N. Nunez. 2021. “Water Scarcity and Procedural Justice in Honduras: Community based Management Meets Market-based Philosophy.” World Development 142: 105451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105451.

- Hamblin, A. 2009. “Policy Directions for Agricultural Land Use in Australia and Other Post-Industrial Economies.” Land Use Policy 26 (4): 1195–1204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2009.01.002.

- Hammersley, M. A., C. Scott, and P. Giullett. 2018. “Evolving Conceptions of the Role of Large Dams in Socio-economic Resilience.” Ecology and Society 23 (1): 09928–230140. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09928-230140.

- Hart, B., A. Horne, and E. O’Donnell. 2016. “Rush to Dam Northern Australia Comes at the Expense of Sustainability.” The Conversation June 27 2016. https://theconversation.com/rush-to-dam-northern-australia-comes-at-the-expense-of-sustainability-61566.

- Hart, B., E. O’Donnell, and A. Horne. 2019. “Sustainable Water Resources Development in Northern Australia: The Need for Coordination, Integration and Representation.” International Journal of Water Resources Development 36 (5): 777–799. https://doi.org/10.1080/07900627.2019.1578199.

- Hartwig, L. D., S. Jackson, F. Markham, and N. Osborne. 2022. “Water Colonialism and Indigenous Water Justice in South-Eastern Australia.” International Journal of Water Resources Development 38 (1): 30–63.

- Hartwig, L. D., S. Jackson, and N. Osborne. 2020. “Trends in Aboriginal Water Ownership in New South Wales, Australia: The Continuities Between Colonial and Neoliberal Forms of Dispossession.” Land Use Policy 99: 104869. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104869.

- International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA). 2023. “The Indigenous World 2023: Australia – IWGIA.” https://www.iwgia.org › australia › 5143-iw-2023-australia.

- Jackson, S. 2005. “Indigenous Values and Water Resource Management: A Case Study from the Northern Territory.” Australasian Journal of Environmental Management 12 (3): 136–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/14486563.2005.10648644.

- Jackson, S., and M. Barber. 2016. “Historical and Contemporary Waterscapes of North Australia: Indigenous Attitudes to Dams and Water Diversions.” Water History 8 (4): 385–404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12685-016-0168-8.

- Johnson, L., L. Porter, and S. Jackson. 2017. “Reframing and Revising Australia’s Planning History and Practice.” Australian Planner 54 (4): 225–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/07293682.2018.1477813.

- Jones, R. S. 2000. “Rongōa Māori and Primary Health Care.” Master of Public Health, Thesis. University of Auckland: http://www.hauora.com/downloads/files/Thesis-Rhys%20Griffith%20JonesRongoa%20Maori%20and%20Primary%20Health%20Care.pdf.

- Kahneman, D., and A. Tversky. 1982. “The Psychology of Preferences.” Scientific American 246 (1): 160–173. https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican0182-160.

- Knight, C. 2016. New Zealand’s Rivers: An Environmental History. Christchurch, New Zealand: Canterbury University Press.

- Knudsen, E. R. 2004. “The Circle & the Spiral: A Study of Australian Aboriginal and New Zealand Māori Literature.” Rodopi 68: 1–32.

- Loucks, D. P., and E. Van Beek. 2017. Water Resource Systems Planning and Management: An Introduction to Methods, Models, and Applications. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Loucks, D. P., E. van Beek, D. P. Loucks, and E. van Beek. 2017. “Water Resources Planning and Management: An Overview”. Water Resource Systems Planning and Management: An Introduction to Methods, Models, and Applications, 1–49.

- Lurgio, J. 2019. “Saving the Whanganui: Can Personhood Rescue a River?” The Guardian, 30 Nov, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/nov/30/saving-the-whanganui-can-personhood-rescue-a-river.

- Macpherson, E., and F. Clavijo Ospina. 2018. “The Pluralism of River Rights in Aotearoa New Zealand and Colombia.” Journal of Water Law 25: 283–293.

- Martuwarra RiverOfLife, K. S. Taylor, and A. Poelina. 2021. “Living Waters, Law First: Nyikina and Mangala Water Governance in the Kimberley, Western Australia.” Australasian Journal of Water Resources 25 (1): 40–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/13241583.2021.1880538.

- Maslow, A. H. 1954. Motivation and Personality. New York: Harper.

- Maslow, A. H. 1993. The Farther Reaches of Human Nature. New York: Penguin Compass.

- McMahon, T. A., and C. Petheram. 2020. “Australian Dams and Reservoirs Within a Global Setting.” Australasian Journal of Water Resources 24 (1): 12–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/13241583.2020.1733743.

- Moggridge, B. J., and R. M. Thompson. 2021. “Cultural Value of Water and Western Water Management: An Australian Indigenous Perspective.” Australasian Journal of Water Resources 25 (1): 59–71.

- Morris, J. D., and J. Ruru. 2010. “Giving Voice to Rivers: Legal Personality as a Vehicle for Recognising Indigenous Peoples’ Relationships to Water?” Australian Indigenous Law Review 14 (2): 49–62.

- National Library. 2023. Te Rarawa. The National Library of New Zealand, https://natlib.govt.nz/records/22350276.

- Newig, J., and M. Rose. 2020. “Cumulating Evidence in Environmental Governance, Policy and Planning Research: Towards a Research Reform Agenda.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 22 (5): 667–681. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2020.1767551.

- Normyle, A., M. Vardon, and B. Doran. 2022. “Ecosystem Accounting and the Need to Recognise Indigenous Perspectives.” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 9 (1): 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01149-w.

- Nursey-Bray, M., and R. Palmer. 2018. “Country, Climate Change Adaptation and Colonization: Insights from an Indigenous Adaptation Planning Process, Australia.” Heliyon 4: e00565–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e00565.

- Nursey-Bray, M. J., J. Vince, M. Scott, M. Haward, K. O’Toole, T. Smith, and B. Clarke. 2014. “Science Into Policy? Discourse, Coastal Management and Knowledge.” Environmental Science & Policy 38: 107–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2013.10.010.

- Nursey-Bray, M., and Arabana Aboriginal Corporation. 2015. “Cultural Indicators, Country and Culture: The Arabana, Change and Water.” The Rangeland Journal 37: 555–569. https://doi.org/10.1071/RJ15055.

- NZ Government. 2020. National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management 2020.

- NZ Hydrological Society. 2021. “From Hydrology to Policy Development and Implementation: Trends in Aotearoa New Zealand’s Freshwater Management and Governance.” In 60th Anniversary Publication of the NZ Hydrological Society, December 2021, edited by A. Fenemor and N. Kirk, 39–56. Wellington, New Zealand: New Zealand Hydrological Society.

- O’Donnell, E., S. Jackson, M. Langton, and L. Godden. 2022. “Racialized Water Governance: The ‘Hydrological Frontier’ in the Northern Territory, Australia.” Australasian Journal of Water Resources 26 (1): 59–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/13241583.2022.2049053.

- O’Donnell, E., M. Kennedy, D. Garrick, A. Horne, and R. Woods. 2023. “Cultural Water and Indigenous Water Science.” Science 381 (6658): 619–621. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adi0658.

- Ostrom, E. 1990. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge University Press.

- Owens, K., E. Carmody, Q. Grafton, E. O’'Donnell, S. Wheeler, L. Godden, R. Allen, et al. 2022. “Delivering Global Water Security: Embedding Water Justice as a Response to Increased Irrigation Efficiency.” WIRES Water 9 (6): e1608. https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1608.

- Parsons, M., K. Fisher, and R. P. Crease. 2021. Decolonising Blue Spaces in the Anthropocene: Freshwater Management in Aotearoa New Zealand. 494. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature.

- Patrick, M. J., G. J. Syme, and P. Horwitz. 2014. “How Reframing a Water Management Issue Across Scales and Levels Impacts on Perceptions of Justice and Injustice.” Journal of Hydrology 519: 2475–2482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2014.09.002.

- Petheram, C., J. Gallant, P. Wilson, P. Stone, G. Eades, L. Roger, A. Read, et al. 2014. Northern Rivers and Dams: A Preliminary Assessment of Surface Water Storage Potential for Northern Australia, CSIRO Land and Water Flagship Technical Report. Canberra, Australia: CSIRO.

- Petheram, C., I. Watson, C. Bruce, and C. Chilcott, eds. 2018. Water Resource Assessment for the Mitchell Catchment. A Report to the Australian Government from the CSIRO Northern Australia Water Resource Assessment, Part of the National Water Infrastructure Development Fund. Australia: Water Resource.

- Porter, L. 2016. Unlearning the Colonial Cultures of Planning. London, UK: Routledge.

- Richter, B. D., S. Postel, C. Revenga, T. Scudder, B. Lehner, A. Churchill, and M. Chow. 2010. “Lost in Development’s Shadow: The Downstream Human Consequences of Dams.” Water Alternatives 3 (2): 14–42.

- Riege, A. M. 2003. “Validity and Reliability Tests in Case Study Research: A Literature Review with ‘Hands-on’ Applications for Each Research Phase.” Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal 6 (2): 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1108/13522750310470055.

- Robson-Williams, M., D. Painter, and N. Kirk. 2022. “From Pride and Prejudice Towards Sense and Sensibility in Canterbury Water Management.” Australasian Journal of Water Resources 26 (1): 84–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/13241583.2022.2063483.

- Ross, H., and C. Baldwin. 2022. “Water as a Source of Innovation in Environmental Policy and Management.” Australasian Journal of Environmental Management 29 (2): 97–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/14486563.2022.2090126.

- Ruhl, J. B., and J. E. Salzman. 2019. “Why Environmental Zero-Sum Games are Real.” Beyond Zero-Sum Environmentalism, 19–26. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3401601.

- Ruru, J. 2013. “Indigenous Restitution in Settling Water Claims: The Developing Cultural and Commercial Redress Opportunities in Aotearoa, New Zealand.” Pac. Rim L. & Pol’y J. 22: 311.

- Stats, NZ. 2023. “Māori Population Estimates: At 30 June 2022 – Stats NZ.” https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/maori-population-estimates-at-30-june-2022/#:~:text=At%2030%20June%202022%3A,17.4%20percent%20of%20national%20population.

- Syme, G. J., and B. E. Nancarrow. 2012. “Justice and the Allocation of Natural Resources: Current Concepts and Future Directions.” In The Oxford Handbook of Environmental and Conservation Psychology, edited by S. D. Clayton, 93–112. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199733026.013.0006.

- Syme, G. J., B. E. Nancarrow, and J. A. McCreddin. 1999. “Defining the Components of Fairness in the Allocation of Water to Environmental and Human Uses.” Journal of Environmental Management 57 (1): 51–70. https://doi.org/10.1006/jema.1999.0282.

- Syme, G. J., N. B. Porter, U. Goeft, and E. A. Kigton. 2008. “Integrating Social Wellbeing into Assessments of Water Policy: Meeting the Challenge for Decision Makers.” Water Policy 10 (4): 323–343. https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2008.152.

- Taylor, L. B., A. Fenemor, R. Mihinui, T. A. Sayers, T. Porou, D. Hikuroa, … M. O’Connor. 2021. “Ngā Puna Aroha: Towards an Indigenous-Centred Freshwater Allocation Framework for Aotearoa New Zealand.” Australasian Journal of Water Resources 25 (1): 27–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/13241583.2020.1792632.

- Te Aho, Linda. 2016. “Legislation – Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River Claims Settlement) Bill – the Endless Quest for Justice.” Maori Law Review. (online): http://maorilawreview.co.nz.ezp.lib.unimelb.edu.au/2016/08/legislation-te-awa-tupua-whanganui-river-claims-settlement-bill-the-endless-quest-for-justice/.

- Te Aho, Linda. 2019. “Te Mana o te Wai: An Indigenous Perspective on Rivers and River Management.” River Research and Applications 35 (10): 1615–1621. https://doi.org/10.1002/rra.3365.

- Tello, E., and J. Hazelton. 2018. “The Challenges and Opportunities of Implementing General Purpose Groundwater Accounting in Australia.” Australasian Journal of Environmental Management 25 (3): 285–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/14486563.2018.1431157.

- Tingey-Holyoak, J. L., A. Fenemor, and G. Syme. 2022. “Enhancing the Value of Water: The Need to Start from Somewhere Else.” Australasian Journal of Water Resources 26 (1): 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/13241583.2022.2088138.

- Tingey-Holyoak, J., and J. D. Pisaniello. 2019. “Water Accounting Knowledge Pathways.” Pacific Accounting Review 31 (2): 258–274. https://doi.org/10.1108/PAR-01-2018-0004.

- Tingey-Holyoak, J. L., J. D. Pisaniello, and R. L. Burritt. 2013. “Living with Surface Water Shortage and Surplus: The Case of Sustainable Agricultural Water Storage.” Australasian Journal of Environmental Management 20 (3): 208–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/14486563.2013.819302.

- Traditional Owner Partnership and Alluvium. 2022. Framework: Multiple Benefits of Ownership and Management of Water by Traditional Owners. Report produced for Traditional Owner Partnership, Central and Gippsland Region Sustainable Water Strategy. https://alluvium.com.au/project/multiple-benefits-of-ownership-and-management-of-water-by-traditional-owners/.

- Troy, P., and D. Holloway. 2004. “The Use of Residential Water Consumption as an Urban Planning Tool: A Pilot Study in Adelaide.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 47 (1): 97–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/0964056042000189826.

- Twomey, A. 2017. “Prelude to the Tasmanian Dam Case-Constitutional Crises, Reserve Powers and the Exercise of Soft Powers.” In The Tasmanian dam Case: 30 Years On: An Enduring Legacy, 44–50, edited by M. Coper, H. Roberts, and J. Stellios. Annandale: The Federation Press.

- Ulloa, A. 2020. “The Rights of the Wayúu People and Water in the Context of Mining in La Guajira, Colombia: Demands of Relational Water Justice.” Human Geography 13 (1): 6–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1942778620910894.

- United Nations (UN). 2017. Bellagio Principles on Valuing Water. Final report, https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/15591Bellagio_principles_on_valuing_water_final_version_in_word.pdf.

- United Nations (UN). 2021. The United Nations World Water Development Report 2021: Valuing Water. UNESCO, Paris. S., Borde R., Brown J., Calamia M., Mitchell. https://www.unwater.org/publications/un-world-water-development-report-2021.

- United Nations (UN). 2023. Valuing Water Initiative. https://valuingwaterinitiative.org/.

- Vörösmarty, C. J. 2010. “Global Threats to Human Water Security and River Biodiversity.” Nature 467: 555–561. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09440.

- White, P. A. 2020. “Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs and Water Management.” Journal of Hydrology (NZ) 59: 1–16.

- Wishart, M. J., S. Ueda, J. D. Pisaniello, J. L. Tingey-Holyoak, and E. B. García. 2020. Laying the Foundations: A Global Analysis of Regulatory Frameworks for the Safety of Dams and Downstream Communities. Washington DC, US: World Bank Publications.

- Young, R., G. Smart, and J. Harding. 2004. “Impacts of Hydro-Dams, Irrigation Schemes and River Control Works.” Freshwaters of New Zealand 37: 1–15.

- Zara, C. 2015. “Rethinking Tourist gaze Through Hindu Eyes: The Ganga Aarti Celebration in Veranasi, India.” Tourist Studies 15 (1): 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797614550961.