ABSTRACT

Australian dog owners are seeking sustainable alternatives to dog faecal collection and disposal, such as compostable waste bags and home composting. Little is known about dog owners’ attitudes towards composting dog faeces or how they manage dog faeces within private households. Australian dog owners’ (N = 1054) were surveyed to investigate household demographics, how they collect and dispose of dog faeces, their home composting practices, and their attitudes, experiences, and concerns regarding home composting dog faeces. Within households, most dog faeces were collected using tools such as shovels and scoops more than single use bags. General waste bins were the most common home disposal location followed by organic waste bins, home compost and burial. Few participants included compostable plastic dog waste bags in home compost. Most composted dog faeces were applied to non-edible plants within gardens. Over half of dog owners viewed home composting as a potentially effective disposal method and many wanted to home compost dog faeces but were not yet doing so. Reported challenges included a lack of reliable compost information, hygiene concerns and uncertainty how canine de-worming treatments affect compost. Findings are important for conducting future research that reflects current practices and address dog owners’ main concerns and challenges.

1. Introduction

Globally, dog owners are increasingly concerned about the environmental impact of plastic dog waste bags and their decomposition in landfill (Greenman Pedersen Incorporated Citation2009; Nemiroff and Patterson Citation2007). In Australia, legislated public dog waste management requires removal of dog faeces from public spaces via the use of plastic bags, followed by disposal in landfill bins (Keep Australia Beautiful WA Citation2011; New South Wales Government Citation2022b; Parliament of South Australia Citation2020; Victorian Litter Action Alliance Citation2013). Many Australians are seeking more sustainable collection and disposal alternatives such as compostable dog waste bags and home compost (Bayside Council Citation2021; Parletta Citation2021). There is limited research on dog faecal collection, disposal and compost practices, within private households worldwide and particularly within Australia. In the United States and Canada, dog faecal composting has been trialled on large scales within dog parks (Nemiroff and Patterson Citation2007; NowThis Earth Citation2021) and offsite commercial facilities (City of Toronto Citation2018; Krause Citation2023; Reynolds Citation2023). However, most previous trials did not include compostable dog waste bags or test the resulting compost for suitable and/or sanitary applications. These limitations mean previous trials cannot easily inform dog faecal composting within private households.

Dog owners face multiple challenges in accessing sustainable dog faecal composting options. People want reliable information on ‘proper’ disposal methods that will help reduce the environmental impact of their dogs’ faeces (Greenman Pedersen Incorporated Citation2009). Composting, as a dog faeces management option, goes beyond typical bagging and binning, by recycling and utilising this organic waste. Home compost methods in general are under-researched, regardless of whether animal manure is included. To date, very little scientific information exists to guide people on how to effectively compost their dog's faeces and where to safely use it. Consequently, dog owners largely rely on information from non-scientific sources, such as books, online media and local governments.

Most households are not permitted to include dog faeces and compostable plastic bags in kerbside organic waste bins and these rules are becoming increasingly restrictive (New South Wales Government Citation2022a). Councils with access to industrial compost services encourage residents to collect dog faeces using compostable waste bags and place both in household organic waste bins for collection and processing (City of Onkaparinga Citation2022; City of West Torrens Citationn.d.; Green Industries SA Citation2021). Since home compost systems are considered less capable of reaching disinfection temperatures than industrial compost facilities (Barrena et al. Citation2014; Smith and Jasim Citation2009), dog owners are often advised to use home compost systems large enough to generate heat for pathogen reduction (Ackland Citation2018; Natural Resources Conservation Service Citation2005).

Prevailing information for dog owners wanting to home compost their dog faeces is rarely supported with scientific evidence, while recommendations are often contradictory and based on a precautionary approach to potential risks. People are often told to keep dog faeces compost separate from other household food and garden waste compost (City of Onkaparinga Citation2022; Compost Community Citation2021; Environment Victoria Citation2010; Gardening Australia Citation2021; Good Life Permaculture Citation2018; Martin, Gershuny, and Minnich Citation1992; Psiroukis Citation2022). Additionally, dog owners are told to avoid burying or using dog faeces compost near plants grown for human consumption (Ackland Citation2018; City of Onkaparinga Citation2022; Compost Community Citation2021; Environment Victoria Citation2010; Friends of the Port Elliot Dog Park Citation2020; Gardening Australia Citation2015; Green Industries SA Citation2021; Nikolic Citation2021; Psiroukis Citation2022; Seemann Citation2015). Some sources caution against composting dog faeces due to potential risks from dogs’ meat-inclusive diet (Brisbane City Council Citation2021; City of Ipswich Citationn.d.; City of West Torrens Citationn.d.; Desha, Reis, and Caldera Citation2021; Dudman Citation2021; Environment Victoria Citation2010; Friends of the Port Elliot Dog Park Citation2020; Gardening Australia Citation2015; Golden Plains Shire Citationn.d.; Green Industries SA Citation2021; Seemann Citation2015) and medication such as parasite control treatments (City of Onkaparinga Citation2020; Compost Community Citation2021; Desha, Reis, and Caldera Citation2021; Environment Victoria Citation2010). Other sources claim that dog manure is not acceptable for home compost systems (Cairns Regional Council Citationn.d.; City of Casey Citationn.d.; City of Rockingham Citationn.d.; Good Living Citation2022; Inner West Council Citation2021; International Compost Awareness Week Australia Citation2022; Sustainable Gardening Australia Citation2022; Western Metropolitan Regional Council Citationn.d.). However, there is no existing peer-reviewed literature of household dog faecal composting to substantiate or contradict these recommendations.

Previous surveys have investigated general collection and disposal of dog faeces (Greenman Pedersen Incorporated Citation2009; Port Elliot Dog Waste Project Citation2021), but few (Lubeck and Hansen-Connell Citation2021) considered household practices. Recent studies found a small percentage of dog owners are composting their dog faeces at home (Massetti et al. Citation2023; Sherlock, Holland, and Keegan Citation2023). Some dog waste home compost products are commercially available (Biomaster Citationn.d.; Bokashi Composting Australia Citation2014a; Doggie Dooley Citation2020; Rapid Results for Gardens & Lawn Citation2022; Wormfarms Australia Citationn.d.) both in Australia and overseas. Most dog faecal home compost products are designed to be buried in-ground and placed away from areas where edible plants are grown (Biomaster Citationn.d.; Bokashi Composting Australia Citation2014a; Doggie Dooley Citation2020; Rapid Results for Gardens & Lawn Citation2022; Tumbleweed Citation2018). Products generally use either microbial inoculants (Biomaster Citationn.d.; Bokashi Composting Australia Citation2014b; Doggie Dooley Citation2020) or vermicompost worms (Rapid Results for Gardens & Lawn Citation2022; Tumbleweed Citation2018; Wormfarms Australia Citationn.d.) to facilitate the compost process, but instructions about including faeces from dogs treated with de-worming medication and compostable/biodegradable plastic dog waste bags are inconsistent (Biomaster Citationn.d.; Wormfarms Australia Citationn.d.). Additionally, it is currently unknown how many dog owners use home compost systems/ products or their effectiveness at producing a quality, sanitised compost. A better understanding of how dog owners collect, dispose and compost dog faeces within households is needed to inform studies to determine the best practices for home composting dog faeces, including potential risks and the effectiveness of commercial dog faecal home compost product.

Similar to dog waste surveys, home compost studies rarely ask participants about including dog faeces in home compost systems. Very few of surveyed home composters in the United Kingdom reported composting pet waste, but it is unknown what proportion of this waste was dog faeces (Bench et al. Citation2005). In Australia, a multi-council-led trial investigated how much pet faeces and plastic pet waste bags could be diverted from landfill by residents using a commercially-available home compost system (Northern Beaches Council Citation2016; Willoughby City Council Citation2018). Limited publicly available information could be found on the results of this trial. Findings from one council indicated that most pet faeces composted were from dogs (Willoughby City Council Citation2018).

This is the first study to comprehensively investigate dog faecal collection, disposal and home composting practices amongst Australian dog-owning households. It explores home compost methods, compost end uses and dog owners’ overall attitudes towards home composting dog faeces. The survey also identifies dog owners’ main dog faecal home composting challenges and concerns that remain unaddressed by popular advice and product manufacturers. As this study was conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, rates of dog ownership and local regulations have changed. Findings from this paper provide essential knowledge to inform the design and implementation of future household compost trials that reflect dog owners’ current practices and concerns.

2. Methods

The study design was an anonymous, cross-sectional survey of Australian dog owners. Data were collected online using the Survey Monkey platform between Dec 2019 and April 2020 (CQUniversity Human Ethics Approval Number 2213). Members of the public older than 13 years of age and living in Australia with at least one household dog were invited to participate. Participants were screened for eligibility at the start of the survey through an informed consent question.

Participants were recruited through traditional and social media using simple random and convenience sampling methods. A survey link was promoted through the authors’ social networks including Twitter, LinkedIn and Facebook. Further study recruitment was achieved through CQUniversity networks including digital newsletters, media releases and letters to the editor. Radio interviews and newspaper articles (digital and print) with the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC), The Advertiser, and regional/community outlets resulted in national exposure of the study and broad participant recruitment.

The survey consisted of multiple-choice questions relating to household (human and dog) demographics. Demographic questions focused on household rather than personal factors, so questions about age, gender, education, etc. were intentionally omitted. Participants were asked to describe their geographic location, property/dwelling type, property location and home ownership status. Participants were asked the number of people living in the household and their caretaking relationship with resident dog(s). Regarding dog demographics, owners were asked the number of dogs living within the household, where the dog(s) spend most of their time within the property, the quantity of faeces their dog(s) produced daily and where faeces were posited. Participants were also asked how often their dog(s) received preventative worming medication.

Multiple-response questions explored participating dog owners’ household dog faecal collection and disposal practices. Questions asked how frequently participants picked up dog faeces at home, what tools they used for picking up, and where they disposed of faeces after collection. When responses included home compost as a location for disposal, additional questions were triggered asking about the type of home compost system being used, what other organic materials people put in their compost, and where the finished compost was used within their property. Multiple-choice and open-ended questions were used to assess participants’ attitudes towards home composting as an effective method for dog faeces disposal and their willingness to engage in this practice.

Multiple-response categorical questions (select all that apply) were coded into dichotomies (selected/not selected). Open-ended responses from multiple-response questions were classified into existing categories where possible, then new categories as necessary. Responses to multiple-option categorical questions were reported as n values while single-option categorical questions were reported as percentages.

Descriptive statistical analysis, Chi-Square test of independence, and Fisher's exact test (FET) were conducted using IBM SPSS version 28. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Qualitative data from a single open-ended question were categorised using Microsoft Excel version 16.64 and used to provide further insight into quantitative results. Figures were created with Adobe Illustrator CC version 26.5 and open-source application Flourish Studio (Canva, UK).

Not all entered postcodes from the property location question corresponded with a suburb in that area. Therefore, property location was classified using postcode data according to the Australian Statistical Geography Standard's five relative remoteness classes: major city, inner regional, outer regional, remote and very remote (Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2018). Recoded postcode data will ensure accurate reporting and comparisons with previous and future studies.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Dog-owning household demographics

Household characteristics of participating dog owners and their dogs are described in . Survey participants represented a sample of dog owners across all Australian states and territories. Most participants (67 per cent) lived in major cities, followed by regional (34.6 per cent) and remote (0.7 per cent) areas. Participants generally owned their homes (82.8 per cent) and lived in detached properties with private land (87.0 per cent). The majority of respondents (88.2 per cent) were primary caretakers for their dogs. Households tended to have two to four people (78.1 per cent) and one to two dogs (93.6 per cent) in residence. Within the household, a third (33.9 per cent) of dogs spent all or most of their time indoors, and half (51.9 per cent) a combination of indoors and outdoors. Household demographics in this survey represented a sample similar to those from recent Australian pet ownership surveys (Animal Medicines Australia Citation2022; Nguyen et al. Citation2021; Wilkins et al. Citation2020). Most (91.4 per cent) households from Wilkins et al. (Citation2020) lived in detached homes; 76 per cent of them owned and 24 per cent rented. Dog owners surveyed by Nguyen et al. (Citation2021) lived in mostly suburban (72.9 per cent) areas, followed by urban (20.3 per cent) and rural (6.8 per cent). Respondents to an Animal Medicines Australia (Citation2022) survey had an average 1.3 dogs per dog-owning household. Most households from Port Elliot Dog Waste Project (Citation2021) had 1 dog (54.2 per cent) or 2 dogs (34.0 per cent).

Table 1. Household characteristics of Australian dog owners and their dog(s).

Surveyed dog owners reported most dog faeces were produced within households (41.2 per cent always or usually at home; 51.8 per cent sometimes at home/sometimes away from home), indicating more collection, disposal and composting opportunities occur at home than away from home. Participants estimated the total volume of faeces their dog(s) produce each day using a quantity of Bunnings sausages as unit of measure. Bunnings sausages are iconic in Australian popular culture (Cassar Citation2022) and were chosen as a recognisable visual reference for approximation. Daily volumes of dog faeces were largely produced within households in low (22.0 per cent), < 1 sausage) to moderate (71.1 per cent; 1–5 sausages) amounts. Most (79.9 per cent) dogs were treated for intestinal worms regularly (at least once every 1, 2, 3 or 4 months), followed by occasionally (17.1 per cent; once every 6 months, yearly, when dog(s) show signs of infection, when reminded by vet, dose frequency according to treatment packaging, and when travelling interstate) and rarely (3.0 per cent; once every 1–3 years, rarely, and never).

3.2. Household disposal practices

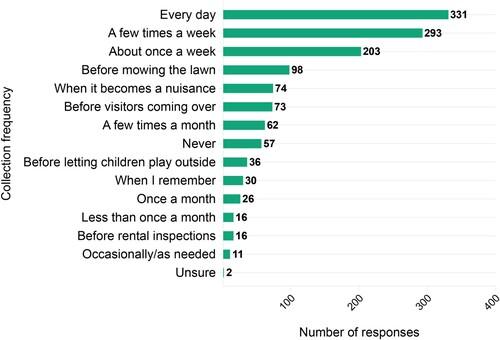

Surveyed dog owners reported how frequently they pick up dog faeces within their households, what tools they use for collection and where they dispose of the faeces. Dog faeces were generally picked up at home at least once a week (n = 827), with nearly a third doing so daily (n = 331) (). Collection frequency is consistent with Lubeck and Hansen-Connell (Citation2021). People who never collected faeces at home (n = 57), commonly noted in free-text responses that their dog(s) did not deposit faeces within their properties.

Figure 1. Household dog faeces collection frequency (n = 1054 participants, total responses n = 1328, multiple response options).

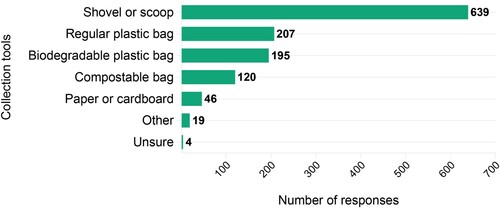

Participants used multiple-use tools such as shovels and scoops (n = 639) more than single use bags (n = 522; compostable, biodegradable and regular combined) to collect dog faeces within households (). Compostable plastic dog waste bags were used least (n = 120), compared to biodegradable plastic (n = 195) and regular plastic (n = 207). Tools specified in the ‘other’ category included bags of unknown material (e.g. dog waste, nappy, recycled) (n = 7), tongs (n = 6), gloves (n = 4), bare hands (n = 1), and compost bin (n = 1). This survey's reported bag use contrasted with the Port Elliot Dog Waste Project (Citation2021) findings that compostable and biodegradable bags (60 per cent and 64.7 per cent) were used more frequently than regular plastic bags (24.1 per cent) or no bags (18.0 per cent). Differing results are likely because the Port Elliot Dog Waste Project (Citation2021) survey question asked about bags use for general dog faecal collection, not just household pickup. Specific types of dog waste bags available in public spaces vary by local council.

Figure 2. Household dog faeces collection tools (total participants n = 1054, total responses n = 1230, multiple response options).

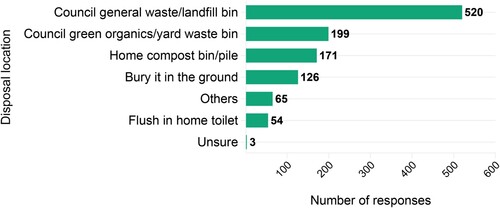

Most household dog faeces were placed in general waste bins (n = 520) (), similar to other studies (Evans McDonough Company Inc. Citation2005; Greenman Pedersen Incorporated Citation2009; Port Elliot Dog Waste Project Citation2021). High proportions of landfill disposal are likely due to limited access to kerbside organic waste recycling services. Surveyed dog owners also disposed of their dog faeces where it could be either industrially (n = 199) or home (n = 171) composted or buried it in the ground (n = 126). Compared to this study, the Port Elliot Dog Waste Project (Citation2021) surveys showed a higher preference for organic waste bin disposal (39.8 per cent) over home compost (4.3 per cent) or burial (5.9 per cent). However, their sample had a large proportion (>90 per cent) of dog owners from South Australia, where most council organic bins allow dog faeces and compostable plastic bags (Green Industries SA Citation2021; Port Elliot Dog Waste Project Citation2021). Disposal location responses in the ‘other’ category included gardens, under shrubs, bushes and trees (n = 31), unused areas of property/paddock/bushland (n = 12), neighbouring property/land (n = 7), sewers (n = 4), fire heaps (n = 4) and pit/hole/grass pile (n = 3). A few dog owners (n = 4) also stated here that they hose and/or mow (uncollected) dog faeces into their lawns.

Figure 3. Household dog faeces disposal location (total participants n = 1054, total responses n = 1138, multiple response options).

It was tested whether there were differences in dog faeces disposed in home compost systems (category selected vs. not selected) as a function of three household variables on the N = 1032. People who de-wormed their dog(s) more often were no more or less likely to home compost dog faeces than those who de-wormed dog(s) less often, (χ2(2) = 4.37, p = .11). Additionally, there were no statistically significant differences found in whether people used home compost systems for dog faeces and daily volume of dog faeces produced (FET, p = .91) or for the type of property (FET p = .28). In contrast, Smith and Jasim (Citation2009) found property type (living in detached/semi-detached properties to be a major factor in home composting rates.

3.3. Household composting practices and experiences

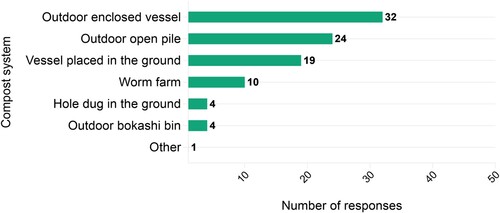

Of the whole survey sample, only some dog owners reported disposing of dog faeces in home compost (). These respondents were asked follow-up questions on what type(s) of compost system they use, what additional feedstocks (if any) they include in compost containing dog faeces, and where on their property they use this compost. Outdoor enclosed vessels were most common, followed by open piles and in-ground compost units (). Worm-based home composts, use of microbial compost treatments and placing dog faeces holes without treatment were less common. This study's dog owners reported an overall preference for using compost vessels and piles associated with general household waste (Bench et al. Citation2005; Smith and Jasim Citation2009) over home compost systems designed specifically for dog faeces.

Figure 4. Household dog faeces compost systems (total sample of home composters n = 171, total responses n = 94, multiple response options).

Qualitative responses revealed some participants’ confusion about the distinctions between dog faeces disposal and composting on and in the ground (e.g. ‘Throw it on the garden or behind the garden near the fence where there is a bit of a ditch’. ‘60 lt rubbish bin with no bottom buried up to rim which is moved when full hole back filled and bin installed in new site’. ‘Dedicated in ground dog poo composter’). Their confusion is understandable since most commercial dog faecal home compost systems are designed for in-ground use (Biomaster Citationn.d.; Bokashi Composting Australia Citation2014b; Doggie Dooley Citation2020; Rapid Results for Gardens & Lawn Citation2022; Tumbleweed Citation2018). Comments indicated participants generally expected to need to dig a hole in the ground for composting dog faeces. Some dog owners considered dog faeces a ‘natural’ material, and/or fertiliser, that will break down naturally either when left in situ on soil surfaces or buried in the ground. However, evidence shows this practice can contaminate soil and water (Bishop and DeBess Citation2020; Center for Watershed Protection Citation1999; Cinquepalmi et al. Citation2012; City of Kirkland Public Works Citation2020; Deviane and Harrison Citation2016; Ervin et al. Citation2014; Massetti et al. Citation2022; Palmer et al. Citation2008; Traversa et al. Citation2014). Burying dog faeces in the ground, without prior treatment or means to accelerate decomposition, does not fit the definition of composting (Diaz et al. Citation1993; Epstein Citation1997). Commercial products for home composting dog faeces are different from simple burial since they use treatments (e.g. microbial inoculants, worms) and additional inputs (e.g. paper, sawdust, grass clippings, water, mixing/aeration) (Bokashi Composting Australia Citation2014a; Rapid Results for Gardens & Lawn Citation2022; Tumbleweed Citation2018; Wormfarms Australia Citationn.d.). The ideal household conditions and inputs needed to achieve effective treatment of dog faeces need further investigation.

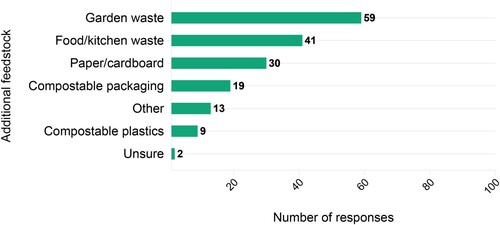

The most common feedstocks added to dog faecal home compost systems were garden waste, food scraps and paper (). These feedstocks are also the most frequently home composted general household wastes (Smith and Jasim Citation2009). Other feedstocks composted were compost additive, sawdust/worm castings, kitty litter and nothing.

Figure 5. Additional feedstocks used in household dog faeces compost systems (total sample of home composters n = 171, total responses n = 173, multiple response options).

Some people put compostable packaging in their dog faecal home compost systems, and a few added compostable plastics, including dog waste bags. Dog owners showed preference for using scoops and shovels for household collection and may be reluctant to home compost these bags due or their uncertainty about whether bags can be added to home compost systems. Of the dog faecal home compost products reviewed in , only one states that compostable bags can be used in their system (Bokashi Composting Australia Citation2014a). Another accepts ‘biodegradable’ bags, but does not stipulate their compostability (Rapid Results for Gardens & Lawn Citation2022), while the anaerobic system states both biodegradable and compostable bags are unsuitable (Doggie Dooley Citation2020). The other products do not mention whether or what types of dog waste collection bags can be used (Biomaster Citationn.d.; Tumbleweed Citation2018; Wormfarms Australia Citationn.d.). Since home compostable plastic bags are designed to help reduce environmental pollution, their effectiveness at breaking down within dog faecal home compost systems should also be evaluated.

Future surveys can be improved by clarifying the definition of ‘composting’ There was some confusion in this survey's responses about what participants considered ‘composting’. Questions should make clear distinctions between home composting (with treatment), burial (with/without treatment), and use of council organic waste bins (industrial compost). The same distinctions should apply to types of plastic dog waste bags used in home composts (e.g. biodegradable, certified industrially compostable, certified home compostable).

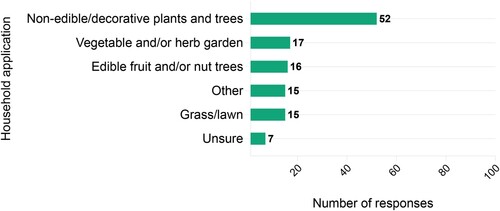

Amongst participants currently home composting dog faeces, most people applied this compost to non-edible plants/trees and lawns or left it in-ground (). This practice reflects prevalent popular media recommendations to avoid use in edible gardens (Ackland Citation2018; City of Onkaparinga Citation2022; Compost Community Citation2021; Environment Victoria Citation2010; Friends of the Port Elliot Dog Park Citation2020; Gardening Australia Citation2015; Green Industries SA Citation2021; Nikolic Citation2021; Psiroukis Citation2022; Seemann Citation2015). Despite this advice, others did apply dog faecal compost to vegetable/herb gardens and edible fruit/nut trees. In open ended responses to this question, some people stated that their dog faecal compost was unfinished/unapplied (e.g. ‘Haven't yet filled the 3 buried bins I have, but only plan to use compost on non edible plants’), while others left the compost in-ground or did not use it on plants (e.g. ‘I just let it degrade where the compost bin is half buried and then move the bin elsewhere’).

Figure 6. Household application of home composted dog faeces (total sample of home composters n = 171, total responses n = 122, multiple response options).

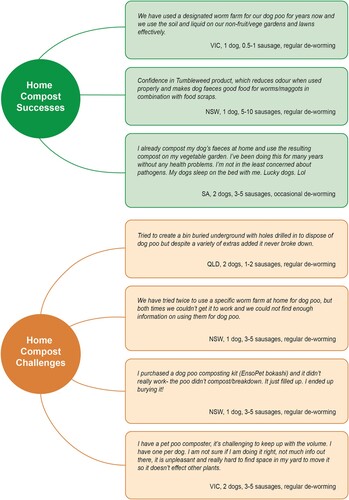

Qualitative open-ended survey questions provided participants opportunities to describe their experiences with home composting dog faeces. Responses were categorised into two main repeated themes relating to participants’ successes and challenges, with representative examples shown in . Dog owners within both categories described using commercially available dog faecal home composting products, but their results with these systems varied.

Figure 7. Dog owners’ experiences (successes and challenges) of home composting dog faeces. Quoted participants are identified using their location (state), number of household dogs, volume of dog faeces produced daily and frequency of intestinal worming treatment administration (regular, occasional, rare).

Successful compost experiences included low odours and/or pests and long-term well-maintained systems (sometimes for years). People composted dog faeces with other household wastes (e.g. food scraps, garden waste) in the same system, and reported effective use of compost in gardens. Responses about compost application primarily mentioned non-edible, ornamental plants and trees, similar to the survey's quantitative findings (). Other dog owners experienced challenges such as repeated and unsuccessful attempts at home composting their dog faeces and a lack of useful information for troubleshooting. They described unpleasant odours and pests, slow or no breakdown of dog faeces, and issues with the volume of dog faeces exceeding capacity of compost systems. Problems with worms dying in dog faecal compost systems were also a relatively common response.

Interestingly, challenges reported by this study's dog owners were common amongst households who used little, or no, dog faeces in their home composts. Obstacles such as presence of rodents and foul odours were reported even in composts that did not contain dog faeces (Faverial and Sierra Citation2014). Flies were common pests in general household organic waste (no manure) home composts (Bench et al. Citation2005; Smith and Jasim Citation2009). While only 6 per cent of Bench et al. (Citation2005) home compost participants included pet waste in their in-ground compost units, 53 per cent reported problems with slow decay. Long degradation times were also observed in non-faecal compost studies (Bergersen, Bøen, and Sørheim Citation2009; Evans McDonough Company Inc. Citation2005; Fernando Citation2021). Participants from Evans McDonough Company Inc. (Citation2005) reported slow decay by worms, a similar challenge experienced by dog owners in this study.

Despite participants’ reported challenges in home composting dog faeces, many surveyed dog owners were willing to use home compost as a method for dog faeces disposal (multiple-choice, single-response question). Over half (n = 551, 54.2 per cent) responded that were not composting dog faeces at home yet but would like to do so. Nearly one quarter (n = 251, 24.7 per cent) stated that they were not interested in home composting dog faeces and 21.1 per cent (n = 214) stated that they were already doing so. There were no statistically significant differences found between the proportion of dog owners willing to home compost dog faeces and property location (FET p = .46) or for home ownership (FET p = .42). The large proportion of dog owners willing to try home composting was unexpected, given the precautionary nature of current advice. These findings indicate a high demand, across dog-owning household demographics, for compost as a method of disposal.

Participants who were not home composting their dog faeces, but wanted to, were asked where they would most likely use composted dog faeces within their households (n = 998, multiple responses). These future composters stated they would more likely use dog faecal home compost on nonedible plants/trees (n = 405) and lawns (n = 198) compared to edible fruit/nut trees (n = 138) and vegetable/herb gardens (n = 127). Use of composted dog faeces was similar amongst current and future composters with preference for application on on-edible plants.

Participants also reported their uncertainty of where to use future dog faecal compost (unsure, n = 109) and concerns for hygienic use on plants for human consumption. Open-ended responses (n = 21, 2.0 per cent) included general safety concern (‘Wherever it would be safe to use it’), uncertainty about applying dog faecal compost to home-grown produce (‘ Wondering if it's safe in gardens of root vegetables, carrots, potatoes, etc.’), and preference for a single household compost system rather than a separate one for dog faeces (‘I want general use compost; I do not want to have to segregate compost’.).

3.4. Household composting attitudes

All dog owners were asked about their views on home compost as an effective method of dog faeces disposal (multiple-choice, single-response question). Most participants answered that it may be an effective solution, but more information is needed on how to do it properly (n = 573, 54.4 per cent). Some considered home composting to be an effective method (n = 147, 13.9 per cent), while others were unsure (n = 129, 12.2 per cent) and others thought it was not effective (n = 85, 8.1 per cent). Open-ended responses (other, please specify; n = 82, 11.4 per cent), largely described participants’ concerns about potential contaminants in dog faeces and a lack of composting space within their properties.

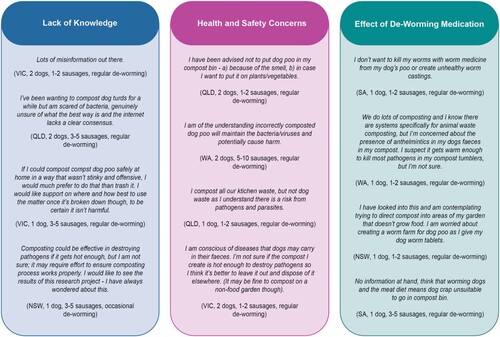

An open-ended, follow-up question asked participants to elaborate on their answer about home compost's effectiveness. Qualitative responses (n = 866) were grouped into one or more categories by common topic, and provided detail on what compost information dog owners want and/or need. Most responses related to three main topics: lack of knowledge, health and safety concerns and effects of worming treatments (). In knowledge-related responses, participants described their uncertainty about effective home compost methods, integrating dog faeces into established compost systems, and appropriate use of compost. Health and safety concerns mostly focused on bacterial and parasitic pathogens present in dog faeces, how to reduce transmission of pathogens through compost, and whether dog faecal compost would contaminate plants grown for human consumption. Dog owners also expressed uncertainty about whether canine anthelminthic medication from dog faeces might contaminate compost or kill worms typically used in vermicomposting.

Figure 8. Main participant response topics and example quotes Dog owners’ views on the effectiveness of home composting dog faeces as a disposal method. Main response topics were lack of knowledge, health and safety concerns, and the effect of dog de-worming medication on home compost. Quoted participants are identified using their location (state), number of household dogs, volume of dog faeces produced daily and frequency of intestinal worming treatment administration.

Additional responses from the follow-up question (effectiveness of home compost as disposal method) provided further insight into dog owners’ overall attitudes. Response topics beyond the main three presented in were categorised into six groups: prior unawareness of/ advice against dog faecal composting, concerns about composting faeces from carnivorous animals, compost nuisance concerns, compost logistical/resource limitations, compost interest/support, compost disinterest/opposition and compost confusion. Beyond the lack of knowledge topic discussed earlier, participants’ comments suggested they had not heard of home composting dog faeces (e.g. ‘I had no idea it could be done let alone how’, ‘I’d never thought of composting dog faeces but would like to know more about it so that I’m not putting more into landfill’), or they had read or been told not to do so (e.g. ‘my vet said it was unhealthy to compost dog faeces and especially not put it on edible plants!’). Responses also revealed owners’ presumptions about not composting faeces from meat-eating animals (e.g. ‘Don't know anything about it. Thought that carnivore poo was bad for the garden. Maybe this is a myth.’; ‘Because more info is required regarding dog poop compost – It's very different compared to using horse/cow manure on your gardens’). Nuisance concerns mentioned were foul odours and pests from including dog faeces in compost (e.g. ‘I think it would smell/attract flies’).

Home compost logistical issues included keeping up with large volumes of dog faeces/multiple dogs, rental restrictions, cost of home compost products, physical limitations of maintaining certain types of compost systems (e.g. ‘Mum is not able to dig holes in her clay soil if she needs a new hole when one site fills up’), and the amount of time required to process compost. Other household challenges stated were a lack of garden space/small property size, unsuitable soil (clay/rocky) for burying dog faecal compost units, and local water restrictions. Participants interested in and/or supportive of home composting dog faeces described their desires to reduce household waste (especially plastic), divert organic material from landfill, and use dog faeces as fertiliser in home gardens. In contrast, comments from people uninterested in-home composting noted lack of time, space or use for compost, and preference for industrially composting their dog faeces through council organic bins. Additionally, responses highlighted participants’ ambiguity on what household practices, especially burial, are considered composting (e.g. ‘Already bury in the garden, is that classes [sic] as composting?’; ‘As stated earlier most of my dog faeces is scattered in garden mulch, leaf litter, or in the past when I had 2 large dogs I used to bury the faeces in a deep holes around the garden, so I think I am already composting dog faeces.’).

Dog owners overwhelmingly reported a need for reliable information and support to safely home compost dog faeces. Other studies have found limited knowledge of compost techniques/skills to be a main obstacle for successful home composting (Edgerton, McKechnie, and Dunleavy Citation2009; Fernando Citation2021; Karkanias, Perkoulidis, and Moussiopoulos Citation2016; Parletta Citation2021; Sulewski et al. Citation2021; Tucker et al. Citation2003). Participants already home composting dog faeces and those who wished to do so required sufficient space, time, and equipment (e.g. appropriately sized home compost system to manage volume of dog faeces produced). These resources were also considered essential for general household waste composting. Non-significant associations in quantitative data were found between home composted dog faeces and volume of faeces or worming frequency. However, qualitative responses showed that participants’ lack of knowledge and health and safety concerns are priority issues that need to be addressed to support people in effectively home composting dog faeces.

Participants’ concerns were unsurprising since currently available advice to dog owners wanting to compost their dog faeces is often inconsistent and unsupported with scientific evidence. Some dog faeces compost products and methods claim to reduce or eliminate pathogens (Bokashi Composting Australia Citation2014a; Tumbleweed Citation2018; Wormfarms Australia Citationn.d.), yet they all caution against using dog faecal compost on or plants for human consumption. Many dog owners expressed concerns about dog faecal pathogens potentially contaminating their compost and edible produce. Some people thought dog diets (e.g. meat-based, raw) might influence pathogen contamination. While domestic dogs are often incorrectly labelled as carnivores, they are considered facultative carnivores who have evolved to eat omnivorous diet through co-habitation with humans (Alessandri et al. Citation2019; Rooney and Stafford Citation2018; Stafford Citation2006). Faeces from dogs fed raw meat diets have been shown to contain more zoonotic bacteria and/or parasites than dogs fed commercial diets (Schmidt et al. Citation2018; van Bree et al. Citation2018). Australian industrial compost quality standards test for indicator bacteria including E. coli, Salmonella and, occasionally, soil transmitted helminth parasites (Standards Australia Citation2012). These standards and test methods may be used as a benchmark for evaluating the safe application of home composted dog faeces. While some respondents reported concerns about canine parasites in home compost, the compost Standard alone does not address this issue. Further testing may be required for the presence of soil transmitted parasites shed in dog faeces.

Surveyed dog owners reported a high rate of administering regular worming treatment that is consistent with other Australian studies on canine anthelmintic use (Nguyen et al. Citation2021; Palmer et al. Citation2008). Nguyen et al. (Citation2021) found most dog owners were aware these treatments reduce the infection risk in dogs and transmission risk to humans. This study's participants expressed dual concerns about potential parasitism from including dog faeces in home compost and how anthelmintic residue from faeces might affect compost worms. While regular prophylactic treatment is likely to reduce the risk of transmitting canine intestinal worms through composting, this study's participants did not appear to connect worming medication with reduced transmission or concentration of parasites in dog faecal compost. Instead, qualitative responses described more concern about the impact of drug residue on the composting process. This uncertainty is likely due to conflicting advice that wormed dog faeces cannot be composted at all (Compost Community Citation2021), can only be composted two weeks post-treatment (Rapid Results for Gardens & Lawn Citation2022), or can be composted without affecting vermicompost worms (Wormfarms Australia Citationn.d.). Again, there is no literature to validate or refute these claims.

4. Conclusion

This is the first study to investigate Australian dog owning households’ dog faecal collection and disposal practices as well as dog owners’ attitudes and practices regarding home composting dog faeces. Results showed a large volume of dog faeces is produced and regularly picked up within households. Much of the faecal matter ends up in landfill, while some is composted industrially through council organic waste bins. People composting their dog faeces at home tend to use general household compost systems and treatments over those designed specifically for dog faeces. Most home composted dog faeces are applied to non-edible plants, largely due to owners’ concerns about dog faecal pathogens.

The large proportion of dog owners willing to try home composting, with more information, demonstrates the potential for more dog faeces to be diverted from landfill and recycled within households. Present and future composters expressed a need for reliable information on how to safely and effectively compost and utilise dog faeces at home. Dog owners predominantly require knowledge on appropriate dog faecal home compost methods/techniques, avoiding dog faecal pathogen transmission, and how canine anthelmintics affect compost worms.

Australian dog ownership rates and organic waste management legislation have both changed since this survey was conducted in 2019-2020, and dog faecal disposal practices have likely been impacted. Dog ownership increased substantially across the country during the COVID-19 pandemic (Animal Medicines Australia Citation2021), so the amount of households’ dog faeces and disposal methods may have also changed. Rapid information and policy changes may also contribute to the confusion within the general public on this topic.

The use of dog faeces in home compost systems remains under-researched. Future surveys on household management of dog faecal waste should clarify the difference between composting via council organic waste bins for offsite processing and composting using within private gardens. Further investigation is needed to understand how access to council organic waste bins for dog faeces and compostable plastic dog waste bags influences dog faecal disposal and composting practices. Additionally, research is needed on how and where dog owners obtain information on dog faecal disposal and home composting to better inform evidence-based communication addressing dog owners’ challenges identified in this study. Future studies on dog faecal home composting practices should investigate the site-specific environmental conditions and inputs needed to effectively compost dog faeces and associated waste gas and safely use the end product without restrictions within domestic gardens.

Australian dog owners want to include dog faeces within home compost and use it within home gardens. In order to do so, they need accurate information relating to the safety and effectiveness of dog faecal compost as a soil conditioner.

Declarations

EB was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Stipend. The other authors did not receive support from any organisation for the submitted work. All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organisation or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Dog Faecal Disposal Practices_Supplementary Material.docx

Download MS Word (31.1 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Professor Tania Signal for reviewing survey questions and providing insightful feedback as well as Associate Professor Amanda Rebar for providing advice on statistical analyses. The valuable contributions of all survey participants are also greatly appreciated.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ackland, L. 2018. “Don’t Waste Your Dog’s Poo – Compost It.” The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/dont-waste-your-dogs-poo-compost-it-107603.

- Alessandri, G., C. Milani, L. Mancabelli, M. Mangifesta, G. A. Lugli, A. Viappiani, S. Duranti, et al. 2019. “Metagenomic Dissection of the Canine gut Microbiota: Insights Into Taxonomic, Metabolic and Nutritional Features.” Environmental Microbiology 21 (4): 1331–1343. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.14540

- Animal Medicines Australia. 2021. Pets and the Pandemic: A Social Research Snapshot of Pets and People in the COVID-19 Era. https://animalmedicinesaustralia.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/AMAU005-PATP-Report21_v1.41_WEB.pdf.

- Animal Medicines Australia. 2022. Pets in Australia: A National Survey of Pets and People, vol. 2022. https://animalmedicinesaustralia.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/AMAU008-Pet-Ownership22-Report_v1.6_WEB.pdf.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2018. 1270.0.55.005 - Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS): Volume 5 - Remoteness Structure, July 2016. https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/mf/1270.0.55.005.

- Barrena, R., X. Font, X. Gabarrell, and A. Sánchez. 2014. “Home Composting Versus Industrial Composting: Influence of Composting System on Compost Quality with Focus on Compost Stability.” Waste Management 34 (7): 1109–1116. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2014.02.008

- Bayside Council. 2021. Community Dog Poo Organic Recycling - Phase 2. Accessed 14 July. https://www.bayside.nsw.gov.au/news/keep-australia-beautiful-nsw-award-nomination-recycled-organics-award.

- Bench, M. L., R. Woodard, M. K. Harder, and N. Stantzos. 2005. “Waste Minimisation: Home Digestion Trials of Biodegradable Waste.” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 45 (1): 84–94. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2005.02.003

- Bergersen, O., A. S. Bøen, and R. Sørheim. 2009. “Strategies to Reduce Short-Chain Organic Acids and Synchronously Establish High-Rate Composting in Acidic Household Waste.” Bioresource Technology 100 (2): 521–526. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2008.06.044

- Biomaster. n.d. Pet waste. Accessed 19 July. https://www.biomaster.com.au/pet-waste-treatment.

- Bishop, G. T., and E. DeBess. 2020. “Detection of Parasites in Canine Feces at Three Off-Leash Dog Parks in Portland, Oregon 2014.” Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Reports, vol. 22, p. 100494.

- Bokashi Composting Australia. 2014a. EnsoPet Instructions. Accessed 14 July. https://images.zeald.com/site/bokashi/images/instructions/EnsoPet%20Instructions.pdf.

- Bokashi Composting Australia. 2014b. Ensopet. Accessed 14 July. https://www.bokashi.com.au/EnsoPet.html.

- Brisbane City Council. 2021. Compost. Accessed 12 December. https://www.brisbane.qld.gov.au/clean-and-green/green-home-and-community/sustainable-gardening/compost-and-food-waste-recycling/compost.

- Cairns Regional Council. n.d. A Guide to Easy Composting. https://www.cairns.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/129691/Composting-at-Home-Fact-Sheet.pdf.

- Cassar, S. 2022. Everything You Need to Know About the Iconic Bunnings Sausage Sizzle. Accessed 10 October. https://www.theurbanlist.com/melbourne/a-list/bunnings-sausage-sizzle.

- Center for Watershed Protection. 1999. A Survey of Residential Nutrient Behavior in the Chesapeake Bay. Ellicott City, MD. https://cfpub.epa.gov/npstbx/files/unep_all.pdf.

- Cinquepalmi, V., R. Monno, L. Fumarola, G. Ventrella, C. Calia, M. Greco, D. de Vito, and L. Soleo. 2012. “‘Environmental Contamination by Dog’s Faeces: A Public Health Problem?’.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 10 (1): 72–84. doi:10.3390/ijerph10010072

- City of Casey. n.d. Your Guide to Composting in Casey. Accessed 12 December 2022. https://www.casey.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files-public/user-files/Waste%20%26%20environment/Guides/Casey-Compost-Guide.pdf.

- City of Ipswich. n.d. Guide to Composting and Worm Farms. Accessed 12 December 2022. https://www.ipswich.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/98205/Worm-Farm-Guide.pdf.

- City of Kirkland Public Works. 2020. City of Kirkland Pet Waste - Bacteria Monitoring, Outreach and Education. https://www.kirklandwa.gov/files/sharedassets/public/public-works/2020-kcd-pet-waste-final-report.pdf.

- City of Onkaparinga. 2020. Worm Farming, Bokashi and Composting. Accessed 12 December 2022. https://www.onkaparingacity.com/files/assets/public/waste-and-recycling/homecompostingsystems.pdf.

- City of Onkaparinga. 2022. Compostable Dog Waste Bags. Accessed 16 July. https://www.onkaparingacity.com/Services/Waste-and-recycling/Waste-and-recycling-education-and-support/Compostable-dog-waste-bags.

- City of Rockingham. n.d. Compost at Home. Accessed 12 December 2022. https://rockingham.wa.gov.au/forms-and-publications/your-city/protecting-our-environment/compost-at-home-guidelines.

- City of Toronto. 2018. Dog waste Program - Parks. Accessed 6 August. https://www.toronto.ca/311/knowledgebase/kb/docs/articles/parks,-forestry-and-recreation/parks/standards-and-innovation/waste-collectiondiversion/dog-waste-program-parks.html.

- City of West Torrens. n.d. Composting at Home. Accessed 12 December 2022. https://www.westtorrens.sa.gov.au/files/sharedassets/public/objective-digitalpublications/external-website/fact-sheets/composting-at-home-booklet.pdf.

- Compost Community. 2021. Composting Pet Poo - Can I or Can’t I?. https://www.compostcommunity.com.au/pet-poo.html.

- Desha, C., K. Reis, and S. Caldera. 2021. “What Can Go in the Compost Bin? Tips to Help Your Garden and Keep Away the Pests.’ Accessed 14 July 2021. https://theconversation.com/what-can-go-in-the-compost-bin-tips-to-help-your-garden-and-keep-away-the-pests-156342.

- Deviane, M., and J. Harrison. 2016. Livable City Year 2017: Pet Waste and Water Quality in the City of Auburn. Seattle: University of Washington. https://lcy.be.uw.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/35/2017/05/ENVH545_PetWaste_Web.pdf.

- Diaz, L. F., G. Savage, L. Eggerth, and C. Golueke. 1993. “Composting.” In Composting and Recycling: Municipal Solid Waste, 1st ed., edited by L. F. Diaz, G. Savage, L. Eggerth, and C. Golueke, 121–174. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

- Doggie Dooley. 2020. How Does a Doggie Dooley Work?. Accessed 14 July. https://doggiedooley.com/how-it-works.

- Dudman, P. 2021. Week 5: How to compost. Accessed 12 December. https://www.sbs.com.au/food/article/2012/07/06/week-5-how-compost.

- Edgerton, E., J. McKechnie, and K. Dunleavy. 2009. “Behavioral Determinants of Household Participation in a Home Composting Scheme.” Environment and Behavior 41 (2): 151–169. doi:10.1177/0013916507311900

- Environment Victoria. 2010. Fact Sheet: The Quick Guide to Composting, Worm Farms and Bokashi. http://environmentvictoria.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/composting-fact-sheet.pdf.

- Epstein, E. 1997. The Science of Composting. Lancaster, Pa: Technomic Publishing.

- Ervin, J. S., L. C. Van De Werfhorst, J. L. S. Murray, and P. A. Holden. 2014. “Microbial Source Tracking in a Coastal California Watershed Reveals Canines as Controllable Sources of Fecal Contamination.” Environmental Science & Technology 48 (16): 9043–9052. doi:10.1021/es502173s

- Evans McDonough Company Inc. 2005. Summary of Composting Survey Conducted in Alameda County, Prepared for Alameda County Waste Management Authority. https://www.stopwaste.org/sites/default/files/Documents/compostsurveysummary.pdf.

- Faverial, J., and J. Sierra. 2014. “Home Composting of Household Biodegradable Wastes Under the Tropical Conditions of Guadeloupe (French Antilles).” Journal of Cleaner Production 83: 238–244. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.07.068

- Fernando, R. L. S. 2021. “‘People’s Participation in Home Composting: An Exploratory Study Based on Moratuwa and Kaduwela Municipalities in the Western Province of Sri Lanka’.” Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal 32 (2): 344–358. doi:10.1108/MEQ-03-2020-0051

- Friends of the Port Elliot Dog Park. 2020. Become an Eco-Friendly Dog Poop Manager. https://epwn.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Managing-dog-poop-at-home.pdf.

- Gardening Australia. 2015. FAQs - Green Rhubarb | Composting Dog Waste | Gypsum and Lime. Accessed 19 July. https://www.abc.net.au/gardening/factsheets/faqs—green-rhubarb-composting-dog-waste-gypsum-and-lime/9436874.

- Gardening Australia. 2021. FAQs – Callus | Old potting mix | Composting dog poo. Accessed 19 July. https://www.abc.net.au/gardening/factsheets/faqs-–-callus-old-potting-mix-composting-dog-poo/13396608.

- Golden Plains Shire. n.d. Residents’ Guide to Home Composting. Accessed 12 December 2022. https://www.goldenplains.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/Compost%20booklet%2014.4.2016_web.pdf.

- Good Life Permaculture. 2018. Home Composting in Hobart. Accessed 12 December 2022. https://rethinkwaste.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Home-composting-in-Hobart.pdf.

- Good Living. 2022. A Beginner’s Guide to Composting. https://www.environment.sa.gov.au/goodliving/posts/2019/05/guide-to-composting.

- Green Industries SA. 2021. Recycle Right - Pet Waste. Accessed 16 July. https://www.recycleright.sa.gov.au/pet-waste.

- Greenman Pedersen Incorporated. 2009. Hillsborough County Pet Waste Research, Florida. http://www.hillsborough.wateratlas.usf.edu/upload/documents/HC-pet-waste-study-final-report.pdf.

- Inner West Council. 2021. A Guide to Composting. Accessed 12 December 2022. https://www.innerwest.nsw.gov.au/ArticleDocuments/1103/IWC_0009_CompostCollective_DL4ppFlyer_FA_R3.pdf.aspx.

- International Compost Awareness Week Australia. 2022. About Composting: Home Composting. Accessed 12 December. https://www.compostweek.com.au/about-composting/.

- Karkanias, C., G. Perkoulidis, and N. Moussiopoulos. 2016. “Sustainable Management of Household Biodegradable Waste: Lessons from Home Composting Programmes.” Waste and Biomass Valorization 7 (4): 659–665. doi:10.1007/s12649-016-9517-1

- Keep Australia Beautiful WA. 2011. Dog Poo Fact Sheet. Accessed 20 December. https://www.kabc.wa.gov.au/library/file/Fact%20sheets/Dog%20poo%20Fact%20sheet%20KAB(1).pdf.

- Krause, D. 2023. “Calgary Pilots Compost Bins at Two City Dog Parks.” Livewiere Calgary. Accessed 10 Aug 2023. https://livewirecalgary.com/2023/04/21/calgary-pilots-compost-bins-at-two-city-dog-parks/.

- Lubeck, A., and M. Hansen-Connell. 2021. Coon Creek Watershed District - Ditch 39 Subwatershed Community Survey, Saint Paul, Minnesota. https://www.wilder.org/sites/default/files/imports/CoonCreek_Ditch39_CommunitySurvey_12-21.pdf.

- Martin, D. L., G. Gershuny, and J. Minnich. 1992. The Rodale Book of Composting. New, revised edn. Emmaus, PA: Rodale Press.

- Massetti, L., R. J. Traub, L. Rae, V. Colella, L. Marwedel, P. McDonagh, and A. Wiethoelter. 2023. “Canine Gastrointestinal Parasites Perceptions, Practices, and Behaviours: A Survey of dog Owners in Australia.” One Health 17: 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.onehlt.2023.100587

- Massetti, L., A. Wiethoelter, P. McDonagh, L. Rae, L. Marwedel, F. Beugnet, V. Colella, and R. J. Traub. 2022. “Faecal Prevalence, Distribution and Risk Factors Associated with Canine Soil-Transmitted Helminths Contaminating Urban Parks Across Australia.” International Journal for Parasitology 52 (10): 637–646. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2022.08.001

- Natural Resources Conservation Service. 2005. Composting Dog Waste, Fairbanks, Alaska.

- Nemiroff, L., and J. Patterson. 2007. “Design, Testing and Implementation of a Large-Scale Urban dog Waste Composting Program.” Compost Science and Utilization 15 (4): 237–242. doi:10.1080/1065657X.2007.10702339

- New South Wales Government. 2022a. FOGO Information for Households. Accessed 1 August. https://www.epa.nsw.gov.au/your-environment/recycling-and-reuse/household-recycling-overview/fogo-information-for-households.

- New South Wales Government. 2022b. Companion Animals Act 1998 No 87. Accessed 19 July 2022. https://legislation.nsw.gov.au/view/html/inforce/current/act-1998-087#sec.20.

- Nguyen, T., N. Clark, M. K. Jones, A. Herndon, J. Mallyon, R. J. Soares Magalhaes, and S. Abdullah. 2021. “Perceptions of dog Owners Towards Canine Gastrointestinal Parasitism and Associated Human Health Risk in Southeast Queensland.” One Health 12: 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.onehlt.2021.100226

- Nikolic, V. 2021. Dog Poo Compost Systems Australia - Turning Poop Into Fertile Soil. Accessed 19 July. https://gentledogtrainers.com.au/dog-poo-compost/.

- Northern Beaches Council. 2016. Pet Poo Composting Trial Begins. Accessed 14 July 2022. https://www.northernbeaches.nsw.gov.au/council/news/media-releases/pet-poo-composting-trial-begins.

- NowThis Earth. 2021. How to Dispose of Dog Poop the Green Way https://www.youtube.com/watch?v = iSUEYHAynJg.

- Palmer, C. S., R. C. A. Thompson, R. J. Traub, R. Rees, and I. D. Robertson. 2008. “National Study of the Gastrointestinal Parasites of Dogs and Cats in Australia.” Veterinary Parasitology 151 (2-4): 181–190. doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.10.015

- Parletta, N. 2021. “Australian Dogs Poo the Weight of the Sydney Harbour Bridge Each Month. Where Should It Go? Pathogenic and Methane-Producing, Poo is the Worst Part of Pet Ownership. But in South Australia, A Group of Enterprising Pet Owners Are Piloting Solutions.” Accessed 14 July 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2021/apr/11/australian-dogs-poo-the-weight-of-the-sydney-harbour-bridge-each-month-where-should-it-go?CMP = Share_iOSApp_Other.

- Parliament of South Australia. 2020. Dog and Cat Management Act 1995, South Australia. https://www.legislation.sa.gov.au/__legislation/lz/c/a/dog%20and%20cat%20management%20act%201995/current/1995.15.auth.pdf.

- Port Elliot Dog Waste Project. 2021. Dog Waste Surveys. https://epwn.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Survey-1-and-2-tables-and-graphs-Jul-2021.pdf.

- Psiroukis, M. 2022. How to Start a Compost System. Accessed 12 December. https://www.choice.com.au/outdoor/gardening/products-and-advice/buying-guides/composting.

- Rapid Results for Gardens & Lawn. 2022. How to Use the Pet Poo Composter. Accessed 14 July 2022. https://www.rapidresults.com.au/wp-content/uploads/How-to-Use-the-Pet-Poo-Composter.pdf.

- Reynolds, L. 2023. Got Dog Poop? Let This Vermicomposting Success Story Inspire You. Accessed 6 Aug. https://www.treehugger.com/dog-poop-vermiculture-compost-myles-stubblefield-7096547.

- Rooney, N., and K. Stafford. 2018. “Dogs (Canis Familiaris).” In Companion Animal Care and Welfare, edited by J. Yeates, 81–123. Wiley. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10 .1002/9781119333708.ch4.

- Schmidt, M., S. Unterer, J. S. Suchodolski, J. B. Honneffer, B. C. Guard, J. A. Lidbury, J. M. Steiner, J. Fritz, and P. Kölle. 2018. “The Fecal Microbiome and Metabolome Differs Between Dogs fed Bones and Raw Food (BARF) Diets and Dogs fed Commercial Diets.” PLoS One 13 (8): e0201279.

- Seemann, R. 2015. The Pet Poo Pocket Guide: How to Safely Compost and Recycle pet Waste. Gabriola Island, BC: New Society Publishers.

- Sherlock, C., C. V. Holland, and J. D. Keegan. 2023. “Caring for Canines: A Survey of Dog Ownership and Parasite Control Practices in Ireland.” Veterinary Sciences 10 (2): 1–13. doi:10.3390/vetsci10020090

- Smith, S. R., and S. Jasim. 2009. “Small-scale Home Composting of Biodegradable Household Waste: Overview of key Results from a 3-Year Research Programme in West London.” Waste Management & Research 27 (10): 941–950. doi:10.1177/0734242X09103828

- Stafford, K. 2006. “Canine Nutrition and Welfare.” In The Welfare of Dogs, 83–100. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Standards Australia. 2012. Composts, Soil Conditioners and Mulches (Incorporating Amendment Np. 1) (AS 4454-2012). Sydney: Standards Australia.

- Sulewski, P., K. Kais, M. Gołaś, G. Rawa, K. Urbańska, and A. Wąs. 2021. “Home Bio-Waste Composting for the Circular Economy.” Energies 14 (19): 1–25. doi:10.3390/en14196164

- Sustainable Gardening Australia. 2022. The Science of Composting. Accessed 12 December. https://www.sgaonline.org.au/the-science-of-composting/.

- Traversa, D., A. Frangipane di Regalbono, A. Di Cesare, F. La Torre, J. Drake, and M. Pietrobelli. 2014. “Environmental Contamination by Canine Geohelminths.” Parasites & Vectors 7 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1186/1756-3305-7-67

- Tucker, P., D. Speirs, S. Fletcher, E. Edgerton, and J. Mckechnie. 2003. “Factors Affecting Take-up of and Drop-out from Home Composting Schemes.” Local Environment 8 (3): 245–259. doi:10.1080/13549830306660

- Tumbleweed. 2018. Pet Poo Worm Farm. Accessed 6 August. https://tumbleweed.com.au/collections/worm-farming/products/pet-poo-worm-farm.

- van Bree, F. P. J., G. Bokken, R. Mineur, F. Franssen, M. Opsteegh, J. W. B. van der Giessen, L. J. A. Lipman, and P. A. M. Overgaauw. 2018. “Zoonotic Bacteria and Parasites Found in raw Meat-Based Diets for Cats and Dogs.” The Veterinary Record 182 (2): 1–7. doi:10.1136/vr.104535.

- Victorian Litter Action Alliance. 2013. Dog poo Litter Prevention kit, Sustainability Victoria. Melbourne: Victoria. https://www.litterwatchvictoria.org.au/resources/Litter-Prevention-Kit_DOG%20POO_2014.pdf.

- Western Metropolitan Regional Council. n.d. How to Compost. Accessed 12 December 2022. https://www.wmrc.wa.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Factsheet-How-toCompost-2019.pdf.

- Wilkins, R., F. Botha, E. Vera-Toscano, and M. Wooden. 2020. The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey: Selected Findings from Waves 1 to 18, Melbourne Institute: Applied Economics & Social Research, University of Melbourne. https://melbourneinstitute.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/3537441/HILDA-Statistical-report-2020.pdf.

- Willoughby City Council. 2018. Pet Waste Trial Results. Accessed 29 July. https://www.google.com/url?sa = t&rct = j&q = &esrc = s&source = web&cd = &cad = rja&uact = 8&ved = 2ahUKEwi9 ( 6yHgqP5AhWj4TgGHTuhAlEQFnoECCIQAQ&url = http%3A%2F%2Fedocs.willoughby.nsw.gov.au%2FDocumentViewer.ashx%3Fdsi%3D5185785&usg = AOvVaw38RVmxWfrB7nI7wqWPQKHS.

- Wormfarms Australia. n.d. Worm Farm Pet and Animal Waste. Accessed 19 July. https://www.wormfarmsaustralia.com.au/worm-farms/worm-farm-dog-waste-pooch-loo-worm-farm/.