Abstract

Drawing on both the history of emotions and study of radicalised temporalities in fascist cultures, this article defines and explores variants of ‘futural nostalgia’ in British fascist discourses from the 1940s to the present day. It defines ‘futural nostalgia’ as a specific type of nostalgia that is both backward looking and forward focused: it looks to the past to evoke a sense of rooted identity, community and ontological security that underpins myriad critiques of the present day as in crisis; it looks forwards in time to provide a vision of an alternate future based on its idealizations of the past. After conceptualizing this term, it explores forms of postwar British fascism that evoke this trope. Starting with Oswald Mosley and the Union Movement, the article examines variants of futural nostalgia in the emotionology of postwar British fascism, including in the National Front, Blood & Honour, the British Movement, the British National Party and National Action. It concludes by suggesting futural nostalgia is an extreme variant of far-right nostalgia, and further exploration of the phenomenon could help establish family relationships between the fascist and populist far right.

Introduction

This article focuses attention on a trope commonly found in British fascist rhetoric, one that this article will classify as ‘futural nostalgia’. The title of a long running magazine of the British extreme right, Heritage and Destiny, expresses a version of this trope, one that, as such a title suggests, is both backwards-looking and future focused. Generally speaking, nostalgia is a yearning for something seemingly lost that can be discovered in a remembered past. When paired with a radicalised, forward-looking politics based on claims a version of this lost time can be recreated in a new way ‘futural nostalgia’ offers a potent, emotional language that is both past and future orientated and underpins calls for fundamental change from the present day. The concept is heuristically useful as it helps us recognise and analyse the emotive qualities of the fascist politics of time. What follows in this article is an examination of variants of a postwar British fascist emotionology that evoke forms of futural nostalgia, a trope that has been developed by many fringe and marginal movements in this period to engage activists with the idea of connecting with something bigger than the self. To examine this theme within a variety of British fascist cultures,Footnote1 I will focus on fascist movement literatures, such as magazines, books and other such material used to communicate with others, that recall in a future-focused manner nostalgic ideas of a national and racial community.

Conceptualising ‘futural nostalgia’

Fascism is a much-debated phenomenon,Footnote2 but for the purposes of this article I will follow the ‘new consensus’ approach and view fascism as an ideology that promotes revolutionary and anti-liberal forms of ultra-nationalism.Footnote3 Moreover, it focuses on fascism in its marginalised form – which comparativists now recognise has been the much more typical presentation of the ideology, while largescale movements and regimes have been more unusual – and so what follows also contributes to the ‘decentring’ of the study of fascism on interwar cases.Footnote4 It also specifically considers fascism through the lens of the history of emotions,Footnote5 which remains under-examined within fascism studies. Robert Paxton has commented on the ‘mobilising passions’ found in fascism,Footnote6 while other historians and sociologists including Mabel Berezin and Cynthia Miller-Idriss have considered the affective aspects of fascism and the wider extreme right,Footnote7 yet the politics of affect and emotion remains under-explored by historians of fascism, especially those that study British fascism. While this article agrees with the identification of fascism as an ideology it also focuses attention on how fascist cultures foster what Peter and Carol Stearns define as an emotionology, a set of messages telling people how to think and feel.Footnote8

While all fascist cultures are steeped in emotive discourses, how can these be studied? Historians of fascism have often commented on the movement’s ability to provoke intense feelings, while emotions in past cultures that can be analysed by historians through the identification of specific ‘emotion words’ (such as ‘hate’, ‘fear’, ‘love’ or ‘pride’) and wider languages that express emotional content. We may never know exactly what emotions people felt in the past, but historians can study what emotions they recorded and used to develop senses of shared community and mission. To generalise, fascist evocations of both the past and the future typically suggest these each represent superior times to the present day, and so they often use positive emotion words to describe these extensions of time; this is contrasted with the present day where negative emotion words tend to dominate descriptions, as fascist politics seek to explain how society has become singularly mired in crises. In sum, fascist discourses typically idealise the past, catastrophise around the present day, and recall an alternate future. Colin Jordan’s Merrie England, William Joyce’s Twilight Over England and Oswald Mosley’s Tomorrow We Live are each evocative titles that summarise such emotive fascist discourses on past, present and future, respectively.

There is already a rich vein of interest in the ways fascist cultures have developed radicalised temporalities within their rhetorics. George Mosse’s pioneering work on fascist culture was among the first to identify fascism as a revolutionary ideology that sought a ‘new man’ to lead the process of change to a new future.Footnote9 More recently, Emilio Gentile has explained that fascism sought an ‘anthropological revolution’ and a new future through elemental change and belief in the new order of fascism and its political religion.Footnote10 Roger Griffin’s influential concept of fascism as ‘palingenesis’, or rebirth of an ultra-nationalist community, has informed much debate on fascist senses of time. For Griffin, palingenesis is a specific type of revolutionary mythology that provides fascists with a sense of meaning and purpose, idealising a mythic version of the past in order to present the present day in crisis and disarray and so requiring a racially transformed future, achieved through a process of national or racial rebirth.Footnote11 In The Nature of Fascism, Griffin argued that fascism is not ‘nostalgic’, as this term connotes only a return to the past, and so fails to grasp the radically forward-looking thrust of fascism. In his subsequent work, Griffin has drawn on theorists such as Peter Osborn to reflect on the politics of time in fascism and employs Osborne’s use of the term ‘futural’ to convey the ways fascist visions are informed by the past but also seek to transcend it.Footnote12 Following this, what I am theorising here is the fascist employment of a specific type of nostalgia that is also future-focused or futural, one distinct from other variants of nostalgia that may lead to passivity and inaction.

Following Griffin and others, many current historians of comparative fascism have also come to regard a radicalised politics of time as central to interpreting fascist culture. The study of radicalised emotions that relate to temporality, such as nostalgia, are also therefore relevant to the growing interest in radicalised senses of time now found in the study of fascist political cultures.Footnote13 Fernando Esposito and Sven Reichardt recognise the temporalities of interwar fascisms were driven by projections of a mythic past to evoke an idealised future, the Thousand Year ‘Third Reich’ being a clear case in point in a mythic construction that was seen as fundamentally new as well as connected to a specific, idealised past.Footnote14 Raul Carstocea has written of the ‘insurgent temporalities’ that underpin fascist ideology, again seeing in the romanticised national past an idealised blueprint for a modernised future, one ultimately to be initiated though violent, revolutionary praxis.Footnote15 These approaches to fascist temporalities have often drawn on François Hartog’s notion of ‘regimes of historicity’, a conceptual framework for analysing ways cultural production develops evocations of the past, the present and the future, and how these relate to one another.Footnote16 For fascists, this article contends, emotions such as futural nostalgia are crucial to developing a particular sense of the past that underpins extremist beliefs in the present through the fantasy of a revolution to come in the future.

Regarding fascist and wider far right uses of nostalgia, notably the postwar Italian Social Movement used the pithy slogan ‘Nostalgia for the Future’ to draw out how its vision of the past would inform a new Italy to come.Footnote17 This striking phrase was also used as the title for Gregory Maertz’s recent exploration of National Socialist era art in Germany, a study which highlights that, while fascinated by the past, Nazism’s artists were future-focused as well.Footnote18 Nostalgic emotions have been commented on in the study of the wider far right, but often analysts need to do more to engage critically with the dynamics of nostalgia in an interdisciplinary manner. Nostalgia has been discussed by, among others, Cas Mudde who noted that nostalgia has been central to Trump’s ‘Make America Great Again’ slogan as well as the 2016 Brexit campaign in the United Kingdom seeking to ‘Take Back Control’.Footnote19 Anders Hellström, Ov Cristian Norocel and Martin Bak Jørgensen present nostalgia as a crucial framing emotion for many far-right agendas that recall an ethnically pure past that ‘never quite existed’, used to undergird tropes such as calls for tighter migration policies and greater securitisation of the state.Footnote20 Ruth Wodak has also commented on the role played by nostalgia, stating the far right often has recourse to: ‘a backwards-oriented politics, an anachronistic agenda attempting to preserve some illusionary past, infused with much nostalgia and anti-intellectualism. This “arrogance of ignorance”, as I have termed it, permeates many domains of our societies’.Footnote21

These variegated assessments of nostalgia within literatures on fascism and the wider far right certainly raise important issues. Yet, ‘nostalgia’ as an analytical term deserves further critical exploration to unpick what the emotion might be doing for those drawn to fascist groups, and how it can be combined with a radicalised future-looking emotive ideals as well. Helpfully, Hans George Betz has discussed the emotion thoughtfully, and critically explored the power of nostalgia to animate forms of the populist radical right in Europe since the turn of the millennium. He explains that, as well as anger and hate, other emotions such as ‘nostalgia can also represent an emotional counterweight providing a positive sense of reassurance and comfort’, and adding the emotion also relates to grief, morning and the loss and rediscovery of a sense of ‘home’.Footnote22 Nostalgic thoughts can provide ontological security. Francesca Polletta and Jessica Callahan, meanwhile, have argued that ‘nostalgia narratives’ have been a crucial part of Trump’s ‘deep truth’ that have allow his stories to resonate among many supporters.Footnote23

While nostalgia is most simply defined as a yearning for an earlier period deemed somehow better, many who have studied the term note that it a concept laced with ambiguities, and that it defies simple explanation. The term is derived from ‘nostos’, to return, and ‘algos’, or pain. References to the notion of nostalgia are found in classical texts, most famously Homer’s epic poem, The Odyssey, where the concept of a longing to return home informed the narrative of Odysseus’s epic journey. The term ‘nostalgia’ itself was coined by Johaness Hofer in 1688, and until recent times has often been considered either an illness or a psychiatric disorder. Even in contemporary colloquial contexts, nostalgia carries with it a suggestion of naivety and ignorance, as implied by the works of Mudde, Wodak, and others. Yet it is too simplistic to see nostalgia merely as a comforting delusion, a naïve and kitsch interpretation of a past that never was – though undoubtedly nostalgic cultural production by fascists can often manifest such qualities. Nostalgia’s specific blend of a positive personal or cultural memory combined with a sense of loss gives it a potent and bittersweet affective signature that helps explain its important resonance for many fascists as a potent force for radicalised messaging. For those drawn to such bittersweet nostalgic tropes, the positives typically outweigh the negatives, and this gives politicised variants of nostalgia a mobilising potential while also conveying a sense of ontological security though select images of the past. Politicised nostalgia can also be part a solution to senses of insecurity and fear created by modernity. Alistair Bonnett has noted that left-wing politics has typically been resistant and dismissive of the power of nostalgia and has failed to recognise how ‘nostalgia works within and against the present, that it reconstitutes modernity, that it is not just reactive but reaches out and down to shape our hopes for the past and the future’.Footnote24 Like others who have studied the phenomenon in detail, Bonnett explains that nostalgia is far from a simple emotion, and underscores how it can play an important role in the ways people come to terms with modernity.

That nostalgia offers community and can be triggered by loneliness, dread and fear is also much commented upon in the psychological literature on the emotion, which has repeatedly noted the problems with conceptualising the many ambiguities of the term.Footnote25 Some approaches have delved further into how nostalgic thoughts plays a crucial role in making sense of time, and show that it can be a mechanism to assert a sense of wellbeing and provoke a wider range of ‘positive’ emotions.Footnote26 Notably, among social psychologists, Terror Management Theorists (TMT) have examined how nostalgia can play a crucial role in managing one’s awareness of the flow of time and in particular overcome fears of mortality.Footnote27 TMT sees as elemental to human psychology the need to manage awareness of existential fears posed by knowledge of the inevitability of one’s own death. As such, nostalgia can function as a mechanism to manage existential fear through the development of a sense of meaning and purpose to life that allows transcendence from individual mortality. Inspirer of TMT, the anthropologist Ernest Becker, noted that creating idealised projections that look both backwards and forward in time are crucial to overcoming the crisis of awareness of one’s finitude, explaining, ‘The burdens of [man’s] painful existence in the here and now are overcome as he projects himself into a heroic past or a victorious future’.Footnote28 Idealised, heroic projections of the past and redemptive visions of the future are, of course, commonplace in fascist cultures, contrasted with a present day typically framed through negative emotions such as despair and anger towards a political mainstream that fails to identify an existential crisis facing an in-community, a race or nation, as well as hatred to those deemed ‘other’ who are deemed antithetical to the ‘in-community’.Footnote29

As cultural theorist Svetlana Boym identifies, cultures of nostalgia span senses of the individual and the communal, allowing for feelings that map the ‘relationship between individual biography and the biography of groups or nations, between personal and collective memory’. In her exploration of the emotion in the wake of the collapse of communist regimes in Europe, Boym proposes a specific sub-variant, ‘restorative nostalgia’. In some ways akin to what this article is calling ‘futural nostalgia’, this variant of the emotion fails to understand its own ‘nostalgic’ qualities and instead sees its discourses as a truth, becomes obsesses with the loss of something that never was and develops conspiracies to underpin why this has become so.Footnote30 This powerful variant of nostalgia for Boym contrasts with a more playful, and arguably healthier, ‘reflective nostalgia’ that is aware of its delusional qualities but finds ways to take comfort from knowingly false yet reassuring ideals. In Boym’s formulation, restorative nostalgia underpins many modern nationalist agendas, as well as phenomena that become obsessed with a particular cause, such as religious revivals. The idea that emotions such as nostalgia are not merely superficial but have an ability to address existential questions and can provide affirming solutions to offer a sense of meaningful ontological security has been explored in various philosophical literatures, including the work of Simone Weil, Martin Heidegger, Hannah Arendt, and Zygmunt Bauman.Footnote31 Space does not allow for full unpacking of these various examinations of managing the past and one’s place in time through nostalgia, but it is clear there are a wide range of thinkers concerned with the existential questioning generated by modernity who have seen idealisations of the past as a common solution to overcoming deep-seated fears and concerns.

To summarise, ‘futural nostalgia’ can be defined as the combination of a profound yearning for a seemingly lost past that is used to develop a politics that sees the present day facing an elemental crisis and seeks a fundamentally new future based on this idealised past. As such variants of futural nostalgia have been a common element in postwar British fascism’s culture (as it has been in many other fascist cultures). This is a generic phenomenon, one that has been used differently by a variety of more intellectual British fascists, overtly neo-Nazi fascists and those seeking mainstream support and who therefore have tended to publicly distance themselves from overt fascism. To examine the ways such futural nostalgia has become an important part of post-1945 British fascist emotionologies, the article will start with Oswald Mosley’s postwar politics, before considering diverse examples including from the National Front, Blood & Honour, the British Movement, the British National Party and National Action. Across all these groups, specific messaging that evokes forms of futural nostalgia has varied significantly, yet recognising this underpinning emotionology helps establish ‘family relationships’ between such variagated groups that make these distinctly fascist.

Oswald Mosley and early postwar British fascism

To begin this exploration of British fascists drawing on an emotionology steeped in futural nostalgia, a useful place to begin is with Oswald Mosley’s postwar politics. Mosley was a leading British fascist activist in the 1930s and openly identified as such, founding the British Union of Fascists (BUF) in 1932 after rejecting mainstream politics and finding inspiration from continental fascist groups and regimes.Footnote32 While the BUF was the largest of the interwar fascist groups in the United Kingdom, like other British fascists Mosley was interned during the Second World War and so the movement fell into decline. After the war’s end, he led a follow-on group, the Union Movement (UM), founded in 1948, and to a degree distanced himself from the label ‘fascist’. Nevertheless, following the methodology of this article, he and others will nevertheless be described as ‘fascist’ if they promoted a variant of revolutionary, anti-liberal ultra-nationalism, which Mosley continued to do so in his later years. As Graham Macklin has demonstrated, Mosley’s postwar career included networking among likeminded fascist intellectuals in Europe as well as on occasion engaging in electioneering in Britain under the Union Movement banner.Footnote33 He was an initial ‘pioneer’ of specifically anti-immigration politics in post-1945 Britain and was also an early proponent of Holocaust denial ideas.Footnote34 While these later years were not politically successful, he also became an inspiration for subsequent generations of British fascists.

In 1947, Mosley published The Alternative, a major exploration of a new type of postwar fascism. He proposed dramatic changes to renew society in the future, notably the union of Europe into a new single nation, Europe-A-Nation, to solve the emerging crisis of a Cold War international order dominated by two superpowers, the USSR and the USA. He also idealised the ‘thought-deed’ man as the heroic figure that would lead the revolutionary changes he deemed were needed. Near the beginning of The Alternative, Mosley reflected on past and future in typically futural nostalgic ways, rhetorically questioning how the past offered a sense of security that would provide a guide to the future as follows: ‘Do the roots still grip and grow in the deep, strong soil of European tradition and culture, so that an ever finer growth of human achievement may evolve to adorn a world which owes nearly all to that inspiration?’ He explained the crisis of the present day in terms of two threats, the ‘mob’ and ‘money’, and was hopeful for change despite the profundity of the present day’s predicament, explaining that ‘Western man’ when faced with ‘moments of collapse’ in the past has ‘so far always exerted itself in time’.Footnote35 Interwar BUF culture has itself often focused on idealising the Tudor era as one of national political flourishing, and here too Mosley discussed the Elizabethan age as being an exemplary, ‘heroic’ time, one that was representative of one face of the ‘soul of England’. He contrasted this spirit with its negative double, the ‘inhibited prig’ of a puritanical England that deceived others and pursued private profit. His concern was to inspire the ‘man of life enthusiasm’ and a ‘cultural expansion’ possessed with ‘Hellenic charm’ to oppose the ‘cautions, inhibited’ aspect of Englishness. His emotive and intellectualised rhetoric continued with the claim that a crucial lesson to learn from the past was that ‘Puritanism bent, twisted and deformed for generations the gay, vigorous and manly spirit of the English’.Footnote36 The idealised future could only emerge if this puritanical culture was destroyed thereby allowing a new heroic era to flourish.

Mosley’s subsequent political writings also often discussed the past to idealise a new future in emotive ways. The essay ‘European Socialism’ from 1956, and reissued a decade later as a pamphlet, used the term ‘socialism’ essentially to legitimise a sense of a right-wing, hierarchical community, not to overcome societal inequalities. As in other texts, here Mosley discussed uniting Europe and while European nations needed to combine as one, they also needed to develop new modes for exploiting empires in Africa to enable ‘the lifting of European civilisation to ever higher forms of life’ in the future. In these ways, Mosley’s thinking was certainly radically futural, and commenting on his distinct appreciation of time was a common trope in his critiques of the political mainstream. According to Mosley, his European socialism was truly a ‘dynamic’ form of politics, in contrast to the ‘static’ understanding of time found in the political mainstream of the left and the right. Mosley explained his vision was focused on ‘constant advance, not a frigid is, nor, worse still, like the policies of the old parties in the present world a frozen was’.Footnote37 Note here the use of the word ‘old’ as a pejorative related to time for mainstream parties. While primarily focused on the sketching out of some of his signature postwar concepts ‘Europe-A-Nation’ and ‘Europe-Africa’, a final section in the pamphlet saw Mosley reflect again on temporality, in a section titled ‘On our present policy in relation to the past’. Here, Mosley explained that it was crucial to develop a ‘spiritual kinship’ with the past, and that the ‘Fascist and National Socialist revolutions’ in Italy and Germany needed to become part of the shared European past, not be excluded from it, as these regimes had certainly developed important advances. He also explained that while the postwar realities called for a new politics, not a re-run of interwar fascisms, this new politics needed to connect to a distant past to offer its new future:

… we Europeans are part of an organic process which has already 3,000 years of great history and is moving to ever higher forms … Nature works not in a steady progression, but in great leaps after long lethargies; and the greatest of all these forward springs is expressed by modern science. That is why for practical purposes all things are new after the cataclysm which precipitated this great advance. For this reason we must think again; then act most strenuously, and on a greater scale than ever because we have greater possibilities. But we remain in the service of the European spirit in a movement to ever higher forms, which began millenia [sic] before us and will continue long after we are gone.Footnote38

In such statements, Mosley attempted to powerfully set out to his readers a conviction in a metanarrative that clearly justified a visionary and forward-looking politics, informed by the breakthrough of modern science, yet one that also needed to connect backwards to thousands of years of European history if it was to overcome the crisis of the present and reach a higher form.

Such futural nostalgia was also a feature of the Union Movement’s newspaper Action, which repeatedly discussed issues such as the breakup of the British empire using tropes of the present day as defined by an existential crisis, the past being a place to find inspirational ideals and the future being fundamentally different through the possibilities offered by a fascist politics.Footnote39 An emotive language of betrayal, specifically of white people, was used to comment on the seminal 3 February 1960 ‘Winds of Change’ speech. ‘MacMillan Betrays Our White Civilisation’ was the headline for an Action article penned by Mosley that heightened its emotive language by talking of the nature of morality. The development of empire was underpinned by a ‘true morality’, while for Mosley it was not moral to sacrifice ‘your own people who have created everything to other people who have created nothing’. He added: ‘Rather it is the way of morality to give our own civilisation place and opportunity to reach further heights, and the under developed people space and opportunity … to reach the level where we stand today’.Footnote40 Emotion was central to this argument as the breakup of the empire was deemed immoral as well as a ‘betrayal’ because it was empowering ‘under developed people’; meanwhile, his call for the continued domination of Britain over others was part of the nation’s moral advancement.

Other articles in Action were nostalgic for the British Union of Fascists itself, a common variant of the trope used to help legitimise previous iterations of fascism. This included an article from 1961 that explained that the BUF’s forward-looking ethos was steeped in revitalising British traditions, and this dynamic was still to be found in the postwar Union Movement. The discussion reflected on the importance of the black fencing outfit that Mosley had worn in 1932 and 1933 when representing England and explained:

Mosley took from the start a typically English style for his Movement’s dress [i.e. a black outfit], symbolising its policy which was summed up in the slogan ‘Britain First’. It symbolised also something quite new in British politics: the protest of youth and all vital forces in the country against the tired and inept misgovernment of the old parties, an appeal to the sportsmanlike instincts of the British character and to all manly pursuits in which Mosley has distinguished himself in fencing and boxing.Footnote41

Mosley’s fascist masculinity here was nostalgically tied to a distinctly British set of traditions around sport that also underpinned the fascist challenge the political and cultural mainstream. Moreover, nostalgia for a fascist group active three decades earlier was used to express the need to find an alternative to mainstream politics in the then present. Remembering the fascist past in such a positive manner was important for Union Movement activists, forming a crucial part of their political identity that continued the quest for a fascist future.

The Union Movement’s evocation of the past in such emotive ways was not merely the preserve of Mosley and publications from the ‘centre’ of the organisation, such as Action. It is often interesting to explore the grass roots materials developed by such movements, and these too exhibited content evoking a fascist temporality through futural nostalgia. The Flash was one such small-scale organ promoting Union Movement ideas. Short articles included several evocating the present day as a liminal period between a better past and an ideal future such as ‘Arise’, written by a contributor named ‘Ram Rod’, which began:

With one foot in a dead and dying world and the other in a world that at all costs we must see born, we must be certain of the courage of what our minds tell us and apply ourselves by patriotic service to the things so urgently necessary and restore at least in part the grandeur, stability and the world influence of our once mighty empire and people. As patriots we must not be idle and spinelessly watch the slow decline any further of our ‘tight little island’.Footnote42

While recapturing elements of a past to recreate a new future was a key theme of this article, another essay, ‘Racial Suicide’ by A. White, drew to mind a looming existential threat and saw the future unfolding in terms of terminal decline, unless a dramatically alternate path was taken: ‘Are you really satisfied to see our race travelling along this road to extinction or will you join us in our fight to save our country and way of life?’ it questioned, implying readers needed to fight to preserve their race.Footnote43

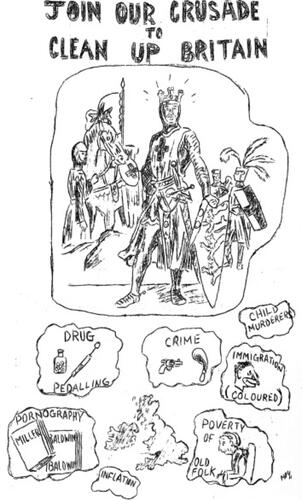

Another of these grass-roots Union Movement publications, Britain Awake – which described itself as ‘The organ of the west London Union Movement’ – again set out an emotive commentary framed around a sense of decline in the present. It decried changing standards on acceptable language to draw out a sense of decline in the present in a section called ‘Colour Blindness’, thereby using nostalgia to underpin defence for its overt bigotry. The short article decried the recent retitling of Agatha Christie’s book Ten Little Niggers to Ten Little Indians, and the renaming of shoe polish from ‘nigger brown’ to ‘dark brown’. The article also worried that the golliwog symbol may soon be removed from Robertson’s jam.Footnote44 Such racist laments, used to exemplify a sense of things getting worse in the present, were underpinned by a sense of nostalgia for when these had been more accepted languages. Medievalism was also part of the Union Movement’s emotionology in such publications,Footnote45 likening its campaigning to a crusade and thereby recalling a sense of the past in terms of a noble and chivalric order, which it compared with a range of threats found in the present day, including immigration, crime, drugs, pornography, child murdered and poverty in old age. Again, a type of futural nostalgia underpins this presentation of an idealised past and a present day in crisis.Footnote46

Finally, the emotive aspects of modern war were used for futural nostalgic value by Mosley, to help connect his politics to an ideal of the nation. The November 1965 edition of Mosley’s intellectual magazine The National European typified this tendency, offering a characteristic example of his fascist futural nostalgia that appropriated the memory of twentieth century war, and especially the fallen soldier. On the cover, next to a picture of the Cenotaph, it asked: ‘They Died – For What?’ The accompanying editorial began by highlighting the hundreds of thousands of young men who died in the two worlds wars, and who were promised a ‘bright and glittering future’ by the ‘old politicians’. Yet, the text lamented, the ‘stream of promises of a better world to come’ from the political mainstream had not materialised and so Mosley described how the postwar British welfare state was now in crisis, becoming overwhelmed by the ‘fresh huge inflow from the unemployed of the coloured Commonwealth which adds up to the impression of Britain the scrapheap of Western civilisation’. Such a crisis at home was compounded by international failure, a trajectory that over the preceding twenty years was described using emotive words such as ‘decline’ and an ‘erosion’, to paint a picture of a country facing the threat of communism and a worsening national and international crisis. While narrating deterioration into multifaceted crises in the present, the text concluded with hope for the future by re-stating the core mission: ‘we who have opposed them [i.e. the old politicians] throughout are those who will build a new world out of the wreckage’.Footnote47 Futural nostalgia here linked Britain’s war dead to a fascist mission for a new future. The fallen soldiers from previous generations were heroized, a betrayal by the mainstream political elite was diagnosed, and only people such as Mosley possessed the visionary ability to recognise the sense of chaos unfolding in the present and offer a possibility for a new future inspired by fascist ideals. That many of those who had died in the Second World War had specifically fought against fascism was, of course, not discussed by Mosley.

From the National Front to National Action

So far, I have focused on Mosley and the Union Movement to highlight some telling examples of British fascism’s futural nostalgia. It has shown this phenomenon can have a variety of layers, recalling distinct periods ranging from millennia of human history, to a more specific focus on times such as the Tudor age, to recalling warmly developments of just a few decades previously, such as aspects of the interwar fascist past, while also promoting a radical future-focused politics. These tropes were quite widespread across a range of British fascist groups, so what follows will now offer some more summary assessments of variations of futural nostalgias in other varieties of postwar British fascism.

Like Mosley, the National Front (NF), founded in 1967, was also interested in developing a nostalgic politics, including around the theme of the nation’s war dead. The NF lacked Mosely’s pro-European vision, while by the 1970s it was predominantly led by John Tyndall,Footnote48 a man who had been a co-founder with Colin Jordan of the National Socialist Movement in 1962 before trying to rebrand his neo-Nazi beliefs as something more clearly patriotic, firstly through the Greater Britain Movement in 1964 and then in the 1970s as a leading figure within the NF itself. NF publications such as National Front News discussed themes including remembering the British war dead, in part as a strategy to appropriate a patriotic issue likely to help legitimise its agenda. Reporting on war remembrance by the NF included a report from 1978 that commented proudly on the way the organisation had marked Remembrance Sunday each year since 1968. The report took care to explain the structure of the NF’s approach to the parade, which was led by the ‘Flag Party’, followed by the ‘Manchester NF Drum Corps’, and then the ‘Wreath-Laying Party’, who comprised leading NF figures with significant military records headed by the party’s Chairman, Tyndall. Behind these formal groups followed many NF supporters with military records who, it noted, were wearing their ‘glinting medals’. The NF facilitating a sense of pride in past miliary service and sacrifice, through a formalised procession, was clearly a strong emotional element of such reporting. Another that was identified was the ways the group was also being humiliated by the state. Underscoring the movement’s overt bigotry, it specifically critiqued the police for placing ‘one of London’s tiny handful of Negro constables at the head of the NF column’, contrasting this detail with the ‘moving ceremony at the Cenotaph’ carried out by the NF, which was followed by speeches at a gathering on the South Bank, where it claimed the party raised a record £1,400 from the assembled crowd.Footnote49

Fabian Virchow has examined emotions in German neo-Nazi marches,Footnote50 and he notes how a wide range of emotive aspects feature in the cultures around fascist marching, from pride and empowerment to frustration and hatred. Such a palette of emotions can be seen in other instances of the reporting of NF marches. A report on a NF St. George’s Day parade from 21 April 1984 criticised the state’s attempt to ban the protest in Salford, yet praised NF organisers for swiftly redeploying the march in the centre of Stoke-on-Trent, leading to a successful event that outwitted ‘bemused Reds who had assumed that we would simply cancel our activity’.Footnote51 Commentary on the marking of days such as these was a step change from the bulk of the reporting in such NF publications, which mainly focused on evoking a sense of crisis in the present, and its newspapers more typically featured articles on affecting issues such as white people as victims of attacks by people of colour, IRA terrorism, threats to the nation posed by European Economic Community, the decline of empire, and the failures of the political mainstream. The need to overturn such multifaceted decline into chaos in the present day was evoked by statements such as a call for the ‘return of leadership and statesmanship to British affairs’, a point its newspapers and leaflets repeatedly noted, as well as seeking in the future ‘Closer links to the White Commonwealth’. Here is a clear point of contrast to Mosley.

Nevertheless, while the NF was more typically focused on discussing the crisis in the present, at least in its campaigning literature, more visionary slogans calling for a fundamentally new future also on occasion featured in these materials: ‘The future belongs to us!’, exclaimed one headline from 1977, reporting on John Tyndall’s campaign to become MP for Hackney South and Shoreditch;Footnote52 while into the 1980s the similar phrase ‘Tomorrow Belongs to Us’ became an evocative BNP slogan.Footnote53 The editorial of the same edition of National Front News explained the wider politics of emotion being developed by the NF in clear terms: ‘If the information which we give arouses our readers to feel anger – which we hope it does – all we ask is that they channel that reasonable and adult emotion into constructive and constitutional political activity’.Footnote54 The organisation was certainly attuned to the value of emotions in its campaigning.

Tyndall himself was keen to indulge in his own brand of futural nostalgia in his book The Eleventh Hour. In a political autobiography format, he expanded on various aspects of British nationalism, as well as his own belief in a British fascist agenda that linked past to future. Of his own name, ‘Tyndall’, he reflected that his family could be traced back to the War of the Roses and prominent ancestors included William Tyndale, the sixteenth century reformation scholar and publisher of the Bible, as well as the nineteenth-century philosopher Professor John Tyndall. While he had not firmly established these figures as direct ancestors, he explained he was sure this could be achieved given the unusualness of his name.Footnote55 Regarding the nation’s past, like Mosley, Tyndall saw the Tudor era as a time of great national flourishing: ‘not only was patriotic sentiment strong and national policy governed by patriotic considerations’, he explained, ‘but the nation was organised in a community regulated by certain civic disciplines, which induced the strict coordination of the national economy in the service of the national good’.Footnote56 This idealised vision of the Tudor era was then destroyed by the rise of liberalism, according to Tyndall, which had remained the key barrier to overcoming national failure ever since. Tyndall was also admiring towards Mosley’s development of fascism in Britain in the 1930s, exclaiming that it offered a ‘total challenge to the liberal outlook that preceded it’, and that it was ‘much more than a new political movement; it was a new creed, almost a religion’,Footnote57 which he meant as a complement. His final chapter, ‘The Way Ahead’, then delved further into the crisis of the present day, and the need to recall the past to develop a new future. He discussed, in a highly emotive use of rhetoric, the ways liberalism was making society ‘terminally sick, in the manner of a political, economic, social and spiritual AIDS’.Footnote58 To resolve this present-day existential crisis, he called for a ‘political outlook which is, in relation to the present, revolutionary [emphasis in original]’.Footnote59 He concluded this call for a new future with a particularly evocative expression of futural nostalgia:

Today, from out of the chaos and the ruin wrought by the old politics, new men are rising … Above them as they work are the spirits of legions of mighty ancestors … Today we feel the voices of these past generations calling down to us in sacred union, urging us to be worthy of their example and their sacrifice. To them we owe it to fight on, and to dare all, so that a great land and a great race may live again in splendour.Footnote60

Tyndall’s leadership of the NF, and later founding of the British National Party, which he led from 1982 until 1999, was clearly informed by this variant of futural nostalgia. Yet other groups also expressed these tropes in potent ways, including much more overtly embracing Nazi-era tropes.

While Tyndall represented an older generation of British fascism, by the end of the 1970s NF figures such as Joe Pearce sought to connect with younger activists. Music was a key aspect of this new wave of British fascist activism, and while Tyndall was an admirer of Wagner, Pierce’s generation sought to create their own white power music.Footnote61 Pearce was a central figure publishing the newspaper of the Young National Front, Bulldog, which from the later 1970s was a publication that championed white power music as part of its activism. Like other NF literatures, Bulldog articles spoke regularly and in emotive ways of a society in crisis and on the cusp of an all-out race war in the near future. Much of the time the magazine was focused on present-day concerns, though specific ideas regarding history were touched upon, such as references to empire and slavery. In some ways these cut against the use of the past as a resource for evoking nostalgia. For example, one editorial by Pearce commented on the idea that white people were, in fact, the most exploited in history. According to the analysis, while black people had been victims of slavery, the only white people who had actually benefitted from this were wealthy slave-owners who at the same time exploited white people in Britain. Emotive imagery was used to evoke such ignored white suffering in the past: ‘Let’s not forget the pregnant women who were forced to crawl around on their hands and knees for hours on end in coal mines or … the eight year old boys who were forced to earn a living by climbing up filthy chimneys’, he explained to help reach the conclusion that ‘the most exploited people …. were the White workers of Britain’.Footnote62

Meanwhile, another edition of Bulldog, from 1984, was concerned with using memories of death and sacrifice to radicalise young readers. It focused on the killing of National Front organiser Albert Mariner in 1983, and featured the lyrics to ‘Sick Society’, a song by the white power band Skrewdriver, that reflected on the death of this former serviceman as follows:

You risked your life for this country when you were young…

Cos the love of the Red, the White and the Blue was in your heart…

Now look at the sick society,

Now look back in time,

Now look at the sick society,

Who commits the crime.

Here, an idealised, romanticised sense of the past was evoked to help generate an emotive depiction of the descent into chaos in the present day, linked to themes of loss and mourning as well. The edition of Bulldog that featured these lyrics also reflected on a police raid on Pearce and other leading NF figures. The front-page report concluded: ‘THEY CAN STOP THE REVOLUTIONARY BUT NOT THE REVOLUTION’. Meanwhile the Editorial, by ‘Captain Truth’, explained the heightening tensions of the group were because ‘the Capitalist system is collapsing, and their multi-racial experiment is failing’.Footnote63 In other words, the crisis in the present day would lead to a revolutionary change to come.

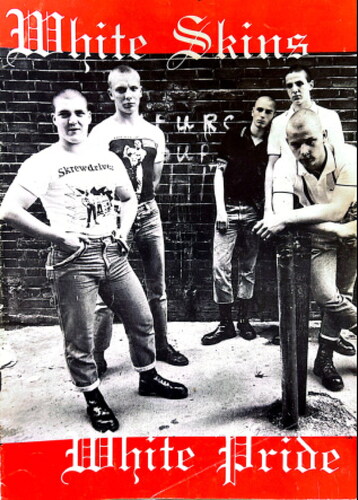

The younger generation of activists such as Pierce that animated Bulldog were also the progenitors of the Blood & Honour movement that emerged by the later 1980s, led by Ian Stuart Donaldson of Skrewdriver. Here too aspects of futural nostalgia were part of the cultural dynamics, as found in a booklet from 1988, White Skins, White Pride. It was described in its opening pages as a ‘Picture book [that] is a celebration of White Pride; the pride in their Race of the skinhead movement worldwide’. The short introduction also explained that followers of the movement were akin to the Stormtroopers of the early Nazi regime and rather than this being an insult, the Blood & Honour movement saw themselves as representing a time to come, and ‘are proud to be regarded as the Stormtroopers of the New Dawn’.Footnote64 While evoking the idea of a new future in such ways, the book itself was filled with evocative pictures of activists linked to the white power music scene from the later 1970s up until 1988 that called to mind a sense of a community of opposition. This included photos of various white power bands performing, as well as scenes of supporters at gigs performing Hitler salutes, and pithy depictions featuring activists surrounded by swastikas and other overtly Nazi-era emblems. The front cover featured German skinheads from Hannover, a picture reproduced later in the volume and dated to 1983, with the caption ‘Greetings from the Fatherland’.Footnote65

The tone for captions was also often light-hearted and distinctly nostalgic, bringing to mind warm memories of the recent past in relation to the movement, such as ‘Brutal Attack fan stares in amazement as Ken McLellan buys a round’;Footnote66 or indulged in humour, such as the caption accompanying an image of two policemen talking to an activist in the street: ‘“What’s all this short hair and Union Jacks then son?” – Britain ‘82’.Footnote67 Yet the radical tenor of the movement was also represented in visual form; one image was a black and white picture of a skinhead male holding a gun superimposed onto a red background with a black and white swastika.

Linked to Blood & Honour was the British Movement, an organisation founded in 1968 by Colin Jordan that initially pursued electoral success until Jordan’s departure in the later 1970s. By the mid 1990s the British Movement was relaunched and has since promoted an overtly neo-Nazi politics, especially in its magazine Broadsword. Its title itself is an example of futural nostalgia, referencing an early modern type of sword described as ‘the traditional weapon of our Celtic and Nordic ancestors’,Footnote68 thereby steeping suggestions of militancy in historical legitimacy. There was repeated engagement with a fascist emotionology, and especially emotive reflections on nostalgia and the placement in time, in many editions of Broadsword. Examples include the cover of an early edition that expressed its liminal idea of temporal placement very clearly, baring the headline: ‘We are Not the Last of Yesterday. But the First of Tomorrow’.Footnote69 Meanwhile, the first edition of Broadsword exemplified the romanticised past underpinning the group’s futural outlook, exclaiming: ‘Britain was all once countryside; villages and hamlets, farms and settlements, market towns, fishing villages, harbours and coves’, yet this had been destroyed by industrialisation that caused people to lose connection with ‘their tradition’s and so ‘the shires went to sleep, their importance lost’. The article, titled ‘Shires Awake’, added that ‘Their [sic] is a direct almost magical link between those who farm the land and those whose generations of blood, sweat and tears have made the soil part of their being, their heritage, the heart of the Folk’. While spending several paragraphs explaining that National Socialism was the only ideology able to restore the link with ‘our heritage’, it concluded that ‘the shires must Awake and lead our Folk back to their heritage’.Footnote70 Fears for the future as a continuation of a worsening present were often expressed in Broadsword; issue nineteen for example was a special edition focused on ‘the fight against Britain sinking into the multiracial swamp’, according to its editorial.Footnote71 One lamenting article was titled ‘The Destruction of England: The decline of the Anglo-Saxon people’ and its text asked ‘“Three lions of a shirt!” IS THAT ALL THE IDENTITY THE ENGLISH HAVE LEFT?’ It concluded that only ‘National Socialism can save England and the English’.Footnote72 Another article, ‘The Last Days of a White World’, used various newspaper clippings to evoke the idea that white people were facing future elimination in the UK.Footnote73 The fascist past was also recalled in positive and nostalgic ways in this edition of Broadsword; a subsequent article presented ‘historical analysis by “a true believer”’, which reflected on the alleged benefits of the Third Reich’s culture and society, which it claimed included a youthful and responsive political leadership, the promise of a car and modern holidays, positive roles for women as part of the national community and a firm stance opposing homosexuality. Germany’s National Socialist society would be a clear improvement on contemporary Britain as according to this glowing, futural nostalgic account, as the Nazi regime had ‘enabled Germany to create an economy and sense of national spirit based on the concept of the common good before personal gain’.Footnote74

Over time, specific elements of Broadsword focused on aspects of the past. For example, the first edition of a regular column called ‘Our Ancestors’ was deemed necessary in order to overcome what it regarded as the failure of mainstream education to educate young people about the nature of British history. Without efforts to counter this, ‘a whole generation of White British youngsters will be totally cut off from their heritage and cultural roots’ in the name of multiculturalism and political correctness. It also explained that future editions of the column would explore firstly the Celts, considered here to be the ‘first Britons’, while also discussing the Romans, the Vikings and the events of 1066. The feature was set alongside a picture of the Germanic pagan god Odin.Footnote75 While other columns in the series developed this theme, other Broadsword articles were explicit about the positive vision for the future offered by National Socialism. This included one titled ‘Building an N.S. Future’, which explained the aim of the organisation was ‘the creation of a National Socialist New Order in the UK’, and concluded ‘the time for our Struggle is coming. We must rise to meet that challenge and Build an NS Future’.Footnote76 However, in the 2000s such unconcealed neo-Nazism was not likely to lead to mass support.

While smaller groups such as the British Movement engaged in overtly neo-Nazi futural nostalgia, the BNP of the 2000s used a different variant of these tropes to promote a sense of political legitimacy. Like other British fascist groups, the BNP in the 2000s sought a political and demographic revolution to ‘return’ to an imagined version of a white Britain, although in a modernised form. Notably, the BNP gained 57 local councillors and two MEP by 2009, following the takeover by a ‘modernizing’ leader, Nick Griffin, in 1999.Footnote77 The re-framing of the BNP’s politics in the 2000s clearly sought a specific memory of the past. In terms of its public facing discourse at least, the party focused far more on the nostalgia element rather than the revolutionary vision. It used a variety of approaches here. Strikingly, Christmas is a time for nostalgia, and the BNP repeatedly engaged with this idea. One piece of BNP online content was a YouTube video from 2009 featuring Nick Griffin retelling the nativity story;Footnote78 another saw Griffin and other leading BNP figures pose for a billboard featuring Griffin holding a glass of wine alongside a Christmas tree, with the slogan ‘Merry Christmas from Nick Griffin and the BNP’.Footnote79 Such innocuous, affective presentations of the BNP’s public face steeped in family friendly and nostalgic festive references typified its efforts to rebrand and legitimise the party. These were not always taken at face value by the wider public.

For an organisation that sought patriotic legitimacy, like the NF the BNP unsurprisingly also homed in on the memories of the Second World War, and some of the most striking election broadcasts by the party featured the Second World War in prominent ways. This included a party-political broadcast from 2009 that began by asking: ‘Do you remember when our country was a wonderful place?’. The commentary then evoked the theme of dead British soldiers, and their sacrifices, by explaining ‘our war heroes defied European dictators’ to ‘preserve traditional Christian values’. An image of Winston Churchill then appeared, accompanying stock footage to visually represent Second World War conflict, while later in the broadcast Nick Griffin talked while sat at a desk, behind which was a bookcase featuring British military medals. A sense of crisis in the present day was unsurprisingly then reflected upon, drawing on themes including immigration, described as an ‘invasion’; Islamist terrorism, discussed as a major threat; and condemnation of the supposed banning of St George’s Day celebrations.Footnote80 The use of wartime memories was repeated in other BNP material including its 2010 Party Election broadcast, which this time saw Griffin sat at a desk behind which was a framed photo of Churchill.Footnote81 On at least one occasion, its use of such wartime imagery was called out by the party’s many critics: a BNP campaigning leaflet featured an image of a Spitfire from the Royal Air Force’s 303 Squadron, which was in fact a unit comprised of Polish airmen, sparking mocking criticism from the Daily Telegraph and Daily Mail among others.Footnote82

While such campaigning media was directed to wartime themes, the party was also repeatedly expressive of the fear that white people would a become minority, or even be eliminated completely, from the United Kingdom. White pride was the counterpoint to this fear. The party’s intellectual magazine, Identity, often dwelt on this issue. One editorial by leading figure Paul Golding stated: ‘According to DNA research by Oxford University’s Professor Sykes, white people in Britain whose maternal grandmother was born here before 1948, are 99% descended from those who lived in these islands between 10,000 and 40,000 years ago!’ While Professor Sykes’s popular science work itself has been criticised for its embellished nature,Footnote83 Golding’s article used it as proof to evidence the idea of a white British community that stretched back thousands of years, one that now faced a grave threat to its continuance. People such as himself were being betrayed by ‘a mountain of lies used by the internationalists’, he added, and the ‘only alternative to betrayal’ was the politics of his party. For Golding, the BNP’s fascist politics offered the true solution as it alone was focused on restoring links to the past to give white people security and pride in a world apparently gone awry: ‘I am proud of my rich British and white European heritage and roots and I am not going to betray them or my country’,Footnote84 Golding’s emotive rhetoric stressed.

Griffin also wrote on this theme. Another edition of Identity from 2007 featured the headline ‘We’ve Always Been Here’. This was the title of a four page ‘Chairman’s Article’ by Griffin reflecting on Stephen Oppenheimer’s book The Origins of the British,Footnote85 which itself argues that the genetic ancestry of the peoples of Britain primarily derive from Palaeolithic era migrants from Iberian Peninsula. Whatever the merits or issues with Oppenheimer’s thesis, for Griffin the book allowed for his own exploration of issues around British identity and the past. He stated it showed that Celt and Anglo-Saxon heritage was now less significant than previously thought by nationalists such as himself, yet Oppenheimer’s book also had a value in disproving the modern liberal idea that ‘we are a mongrel national of immigrants’. While critiquing multiculturalism using supposedly scientific evidence, in terms of its presentation the article was set in front of evocative images of Stonehenge and a primitive stone age era style hut, linking these images steeped in the ancient past to a racial sense of white identity. It also included various provocative, futural nostalgic statements combining a sense of reconnecting with the past and the need to become politically active to overcome an existential threat, such as:

This place made us, and we made it. Those who deny this are the real racists. We – the English, the Scots, The Irish and the Welsh, collectively known as the British – are the First Peoples of our Island home. Knowing this we are more entitled than ever to organise and act to preserve our rights, our heritage and our identity against our own treacherous liberal ‘elite’ and the genocidal level of immigration they promote.Footnote86

Presenting white people as facing a ‘genocide’ has become a popular extreme right narrative since the 2010s, often known as the great replacement theory,Footnote87 while this trope has a longer history within the movement as well.Footnote88

After Griffin’s departure from the BNP in 2014, his engagement with variants of futural nostalgic activism has continued, for example through his ‘Templar Report’, an online streamed show and website that sees Griffin discuss issues of the day through a conspiracy theory lens, while evoking the memory of the Knights Templar as a solution to crisis. Associated with this is a range of merchandise for sale via a related website, which includes the book Deus Volt: The Great Reset Resistance that draws on the ideals of the medieval past to discuss the present day in crisis due to the consequences of Covid-19 lockdowns, proposing the need to develop radical political solutions to overthrow a conspiring set of global forces active in the 2020s. The term ‘great reset’ itself refers to another conspiracy theory narrative that became popular during Covid-19 lockdowns.Footnote89 As well as such exciting texts steeped in politicised interpretations of an idealised past and a present day in crisis, visitors to the website can join the organisation by paying $890 for a ‘Full Knight & Regalia Package’, which includes gloves, beret, jewellery and a cape.Footnote90 Such items help activists develop a futural nostalgic way of dressing as well as thinking.

While Griffin’s post BNP activism has veered into overt medievalism and conspiracy theory driven online activism, other splinters from the BNP in the 2010s helped create a new trend in extremist politics: neo-Nazi accelerationism, a movement defined by wanting to speed up the collapse of the capitalist system through direct militant action to create a revolutionary shift to a white supremacist new order.Footnote91 The first group in this vein in the UK was National Action, founded in 2013, including by former BNP Youth activist Alex Davies. In both its materials as well as overt idealisation of Nazism and Adolf Hitler, the group produced a discourse that romanticised the fascist past as part of its idealisation of a fascist future to come. Like the Union Movement and others before it, National Action recalled the memory of Mosley in a clearly futural nostalgic manner, including in the booklet Attack. Mosley’s name was referenced on 17 of the 44 pages of this major statement of the movement’s programme for action, which also included stylized images of Mosley and drew on quotes from his writings for much of the underpinning emotionology of the text. As well as using Mosley to evoke legitimacy for present day violent activism to initiate a revolution, the text’s futural nostalgia explained that a new type of nationalism was also needed, one rooted in a centuries long vision of the past: ‘It must cut across ages, it must be a unified concept of the nation from its earliest past to a vision of the future – for which will be needed an ideology strong enough to last a thousand years’.Footnote92 Again drawing on Mosley, the last words of the booklet added:

To the dead heroes of Britain, in sacred union, we say: Like you we give ourselves to England; across the ages that divide us; across the glories of Britain that unite us. We gaze into your eyes and we give you this holy vow: We will be true – Today, Tomorrow, and Forever! ENGLAND LIVES!Footnote93

While unattributed, these are the closing words of a speech by Mosley from 16 July 1939, delivered at Earls Court. This again is a clear example of an earlier fascist politician being recalled in a nostalgic manner by a group also espousing the need to ‘accelerate’ the coming of a political revolution and a new era. National Action was proscribed in December 2016 under terrorism legislation, including for idealising the murderer of Jo Cox MP earlier that year;Footnote94 yet other forms of neo-Nazi accelerationism that also yearn for a fascist past to inform their visions of a future to come have continued to proliferate in the later 2010s and early 2020s.

Conclusions

This article has explored variants of what it has defined as ‘futural nostalgia’, a trope found in many British fascist discourses from the 1940s to the present day. It has suggested this is an important aspect of the emotionology developed by a wide range of British fascist figures and political organisations, one that can offer an alternative sense of ontological security to those drawn to them through evocations of a specific sense of the past and the future. For the fascists discussed here, across generations of activism there has been repeated efforts to imagine the national past in idealised ways that also relate to projections of a revolutionary escape from liberal modernity and a new future. Futural nostalgia has provided activists with emotive discourses offering the promise of re-connecting with an idealised white nationalist community larger than the self. This trope relates to the theoretical discussion on what nostalgic emotions might be doing for people developed at the beginning of this article. This short review of literatures on nostalgia demonstrated that experts from various disciplines suggest the emotion relates to the need to develop narratives and mythologies around the individual self that provide answers to questions of meaning and purpose, even life and death. Nostalgia can be a way to overcome loneliness and fear and can spark a sense of wellbeing, security, and community. Notably, the British fascists discussed here have developed their emotive discourses in stark ways to achieve such ends, repeatedly presenting their political messages as solutions to perceived existential threats deemed to be facing white people in their present-day contexts, while both idealising white communities in the past and imagining their rebirth in the future.

This discussion has also shown that, while following a common pattern, there is a great deal of variety in how futural nostalgia has been evoked within British fascist cultures. It has explored books, magazines, marches, song, election broadcasts and internet content. For Mosley, futural nostalgia was developed in quite intellectualised ways, while other variants saw it developed in much more pithy and overtly patriotic forms, as with the National Front. Sometimes it has been used to attempt a populist connection, in which case patriotic themes (such as memory of war sacrifice) have come to the fore, as was the case with the British National Party in the 2000s. At other times it has been used to underpin overtly neo-Nazi youth cultures, such as Blood & Honour and more recently National Action. In other formats it has led to a more complex neo-Nazi culture steeped in a specifically British reworking of National Socialist ideas, as found in the British Movement’s literature. Futural nostalgia is also a discourse that allows for intergenerational connections to be alluded to, as can be seen in the repurposing of Mosley’s interwar memory by the Union Movement in the 1960s, as well as the more recent appropriation of Mosley by contemporary British neo-Nazis, such as National Action in the 2010s. Such nostalgia for the fascist past itself has become an important aspect of the wider trend of futural nostalgia, yearning for earlier instances of fascism, especially aspects of the Third Reich, and seeing in it a positive past that offers solutions to existential questions deemed to face white people in the present day.

Finally, the article has specifically focused on a selection of British fascist figures and groups, and has sought to consider an emotionology that includes futural nostalgia that draws people to its ‘positive’ vision. This focus for analysis leads to (at least) two areas of questioning for ongoing research into such British fascist emotionology. Firstly, this discussion on British fascism raises the question of how its futural nostalgia might relate to a more moderated versions of the phenomenon found in the populist radical right. This would allow exploration of the wider range of groups that fit more clearly into the populist radical right category, from the Monday Club to the United Kingdom Independence Party. How similar or different were their politics to the more extreme, fascist emotionology examined here? Is there a wider ‘family relationship’ or ‘functional equivalence’ between these phenomena that the history of emotions can examine in more depth? Secondly, while alluded to in various discussions through this article, emotive, fascist idealisations of the past and the future are often used to underpin and legitimise the articulation of many racist, homophobic and bigoted sentiments towards others. These expressions have had consequences. The recent history of British fascism has not only been rhetorically and symbolically violent, but it has also led to physical attacks and on occasion deadly violence towards people of colour and women in particular. The role of extreme variants of nostalgia as an emotion that underpins such rhetorically and physically violent actions towards those deemed outside the white ‘in-community’, which has been repeatedly idealised by such futural nostalgic discourses, is also crucial to examine in future work on the emotionology of British fascism.

Data statement

Physical data supporting this publication is stored at the Searchlight Archive that is managed by the University of Northampton, and details on how to access this can be found here: https://www.northampton.ac.uk/about-us/services-and-facilities/the-searchlight-archives/. List of archive boxes consulted from this collection are: SCH/01/RES/BRI/13/008; SCH/01/RES/BRI/05/003; SCH/01/RES/BRI/02/022; SCH/01/RES/BRI/03/006; SCH/01/RES/BRI/03/022; SCH/01/RES/BRI/02/009.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Paul Jackson

Paul Jackson is Professor in the History of Radicalism and Extremism at the University of Northampton. He specializes in the history and contemporary dynamics of fascism and the extreme right, and his most recent book is Pride in Prejudice: Understanding Britain’s Extreme Right (2022). He has engaged widely with the media, including national and international press, as well as for BBC radio and television, and has engaged with a wide range of policymakers, professionals and activists. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 Studies of postwar British fascism not cited elsewhere in this article include: Liam Liburd, ‘Turn Again, Fascist Studies: New Perspectives on British Fascism’, 20th Century British History, 32.3 (2021), 462–66; Nigel Copsey and John E. Richardson, Cultures of Post-War British Fascism (Abingdon: Routledge, 2015); John Richardson, British Fascism: A Discourse-Historical Analysis (Stuttgart: Ibidem-Verlag, 2017); Nicholas Hillman, ‘“Tell Me Chum, in Case I Got It Wrong. What Was It We Were Fighting during the War?” The Re-Emergence of British Fascism, 1945-58’, Contemporary British History, 15.4 (2001), 1–34; Paul Stocker, Lost Imperium: Far Right Visions of the British Empire, c.1920-1980 (Abingdon: Routledge, 2021).

2 Recent texts here include: Daniel Woodley, Fascism and Political Theory Critical Perspectives on Fascist Ideology (Abingdon: Routledge, 2009); David Renton, Fascism: History and Theory (London: Pluto Press, 2020); Zeev Sternhell, The Birth of Fascist Ideology: From Cultural Rebellion to Political Revolution (Princeton, N.J. ; Princeton University Press, 1994); Walter Laqueur, Fascism Past, Present, Future (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996); Kevin Passmore, Fascism: A Very Short Introduction, Second edition. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

3 For a discussion on the term ‘new consensus’, see: Roger Griffin, ‘Studying Fascism in a Postfascist Age. From New Consensus to New Wave?’, Fascism, 1.1 (2012), 1–17. For studies that draw on the idea of fascism as a revolutionary form of ultra-nationalism, see: Roger Griffin, Fascism: An Introduction to Comparative Fascist Studies (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2018); Roger Eatwell, Fascism: A History (London: Pimlico, 2003); Stanley G. Payne, A History of Fascism, 1914-1945 (London: UCL Press, 1995).

4 Roger Griffin, ‘Decentering Comparative Fascist Studies’, Fascism, 4.2 (2015), 103–18.

5 Central texts on the methods used in the History of Emotions include: Jan Plamper, History of Emotions: An Introduction, trans. by Keith Tribe, First edition. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015); Rob Boddice, The History of Emotions (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2018); Barbara Rosenwein, Generations of Feeling: A History of Emotions, 600-1700 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016); William Reddy, The Navigation of Feeling: A Framework for the History of Emotions (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

6 See: Robert O. Paxton, The Anatomy of Fascism (London: Penguin, 2005), 40 – 2.

7 Mabel Berezin, ‘Political Belonging: Emotion, Nation, and Identity in Fascist Italy’, in State/Culture (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2018), pp. 355–77; Cynthia Miller-Idriss, Hate in the Homeland: The New Global Far Right (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2022), 44.

8 Peter Stearns and Carol Stearns, ‘Emotionology: Clarifying the History of Emotions and Emotional Standards’, The American Historical Review, 90.4 (1985), 813–36.

9 George L. Mosse, ‘Introduction: The Genesis of Fascism’, Journal of Contemporary History, 1.1 (1966), 14–26.

10 Emilio Gentile, ‘Fascism as Political Religion’, Journal of Contemporary History, 25.2/3 (1990), 229–51.

11 Roger Griffin, The Nature of Fascism (Abingdon: Routledge, 1993), 35.

12 Roger Griffin, Modernism and Fascism: The Sense of a Beginning under Mussolini and Hitler (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), 56 – 8; Osborne, Peter, The Politics of Time : Modernity and Avant-Garde (London: Verso, 1995).

13 Roger Griffin, ‘Fixing Solutions: Fascist Temporalities as Remedies for Liquid Modernity’, Journal of Modern European History, 13.1 (2015), 5–23.

14 Fernando Espositoand Sven Reichardt, ‘Revolution and Eternity. Introductory Remarks on Fascist Temporalities’, Journal of Modern European History, 13.1 (2015), 24–43.

15 Raul Carstocea, ‘Breaking the Teeth of Time: Mythical Time and the “Terror of History” in the Rhetoric of the Legionary Movement in Interwar Romania’, Journal of Modern European History. Vol 13 no. 1 (2015), pp. 79–97.

16 François Hartog, Regimes of Historicity: Presentism and Experiences of Time (Columbia: Columbia University Press, 2016). See also Reinhart Kosseleck, Futures Past: On the Semitics of Historical Time (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004.

17 For a website recalling nostalgically the MSI including its use of this slogan, see: https://azimutassociazione.wordpress.com/2015/12/27/quella-nostalgia-dellavvenire-verso-il-settantennio-di-nascita-del-movimento-sociale-italiano/(accessed 23 November 2023).

18 Gregory Maertz, Nostalgia for the Future Modernism and Heterogeneity in the Visual Arts of Nazi Germany (Stuttgart, Ibidem Verlag, 2019).

19 Cas Mudde, The Far Right in America, First edition. (London: Taylor and Francis, 2017), 108-110.

20 Anders Hellström, Ov Cristian Norocel and Martin Bak Jørgensen ‘Nostalgia and Hope: Narrative Master Frames Across Contemporary Europe’ in Norocel, Ov Cristian, Anders Hellstrom, and Martin Bak Jorgensen, Nostalgia and Hope: Intersections Between Politics of Culture, Welfare, and Migration in Europe (Springer Nature, 2020), 1 – 15.

21 Ruth Wodak, The Politics of Fear: Analyzing Right-Wing Popular Discourse(Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, 2013), 186.

22 Hans-Georg Betz, ‘The Emotional Underpinnings of Radical Right Populist Mobilization: Explaining the Protracted Success of Radical Right- Wing Populist Parties’ (2020) available at: http://www.radicalrightanalysis.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Betz_2020_The-emotional-underpinnings-of-radical-right-populist-mobilization_CARR.pdf. See also Hans-Georg Betz and Carol Johnson, ‘Against the Current-Stemming the Tide: The Nostalgic Ideology of the Contemporary Radical Populist Right’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 9.3 (2004), 311–27.

23 Francesca Polletta and Jessica Callahan, ‘Deep Stories, Nostalgia Narratives, and Fake News: Storytelling in the Trump Era’, American Journal of Cultural Sociology, 5.3 (2017), 392–408.

24 Alastair Bonnett, Left in the Past: Radicalism and the Politics of Nostalgia (New York: Continuum, 2010), p. 169.

25 This literature includes:, Erica G. Hepper, Timothy D Ritchie, Constantine Sedikides, and Tim Wildschut, ‘Odyssey’s End: Lay Conceptions of Nostalgia Reflect Its Original Homeric Meaning’, Emotion 12.1 (2012), 102–19; Clay Routledge, Jamie Arndt, Tim Wildschut, Constantine Sedikides, Claire M Hart, Jacob Juhl, et al., ‘The Past Makes the Present Meaningful: Nostalgia as an Existential Resource’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101.3 (2011), 638–52; Clay Routledge, Tim Wildschut, Constantine Sedikides, Jacob Juhl, and Jamie Arndt, ‘The Power of the Past: Nostalgia as a Meaning-Making Resource’, Memory, 20.5 (2012), 452–60; Jacob Juhl, Clay Routledge, Jamie Arndt, Constantine Sedikides, and Tim Wildschut, ‘Fighting the Future with the Past: Nostalgia Buffers Existential Threat’, Journal of Research in Personality, 44.3 (2010), 309–14; Clay Routledge, Jacob Juhl, Andrew Abeyta, and Christina Roylance, ‘Using the Past to Promote a Peaceful Future: Nostalgia Proneness Mitigates Existential Threat Induced Nationalistic Self-Sacrifice’, Social Psychology, 45.5 (2014), 339–46.

26 Nicholas J. Kelley, William E. Davis, Jianning Dang, Li Liu, Tim Wildschut, and Constantine Sedikides, ‘Nostalgia Confers Psychological Wellbeing by Increasing Authenticity’, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 102 (2022).

27 Clay Routledge, Jamie Arndt, Constantine Sedikides, and Tim Wildschut, ‘A Blast from the Past: The Terror Management Function of Nostalgia’, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44.1 (2008), 132–40. For an introduction to TMT, see: Sheldon Solomon, Jeff Greenberg, and Tom Pyszczynski, The Worm at the Core: On the Role of Death in Life (New York: Random House, 2015).

28 Ernest Becker, The Birth and Death of Meaning An Interdisciplinary Perspective on the Problem of Man (New York: Free Press, 1971), 158.

29 On the role of ‘in-community’ construction in political extremism, see: J. M. Berger, Extremism (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2018).

30 Sveltana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia (New York: Basic Books, 2008), for her typology of nostalgia see the introduction.

31 For an exploration of these philosophers and nostalgia, see: Giulia Bovassi, ‘Philosophy and Nostalgia: “Rooting” within the Nostalgic Condition’, in Intimations of Nostalgia (Bristol: Bristol University Press, 2022), 31–51.

32 For more on interwar British fascism, see: Thomas P. Linehan, British Fascism, 1918-1939: Parties, Ideology and Culture (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000).

33 Graham Macklin, Very Deeply Dyed in Black: Sir Oswald Mosley and the resurrection of British fascism after 1945 (London: I. B. Taurus, 2015).

34 Joe Mulhall, British Fascism after the Holocaust: From the Birth of Denial to the Notting Hill Riots 1939-1958 (Abingdon: Routledge, 2021) p. 72.

35 Oswald Mosley, The Alternative (Ramsbury: Mosley Publications, 1947), 20 – 1.

36 Mosley, Alternative, 23 – 7.

37 Oswald Mosley, European Socialism (London: Sanctuary Press Ltd., 1965), 4.

38 Oswald Mosley, European Socialism (London: Sanctuary Press Ltd., 1965), 19.

39 Oswald Mosley, ‘What Now? The Choices’, Action no. 106. February 1963, 1–2.

40 Oswald Mosley, ‘MacMillan Betrays our White Civilisation’, Action no. 59 March 1960, p.1 and 4.

41 ‘The Story of the Union Movement (2): The Facts About the Blackshirts’ Action no. 68 January 1961.

42 Ram Rod, ‘Arise’, The Flash, no. 1, 1964, 3.

43 A. White, ‘Racial Suicide’, The Flash, no. 1, 1964,6–8.

44 Britain Awake. The Searchlight Archive, SCH/01/RES/BRI/13/008.

45 Studies of fascist medievalism include: Cord Whitaker, ‘The Problem of Alt-Right Medievalist White Supremacy, and Its Black Medievalist Answer’ in Louie Dean Valencia-García ed., Far-Right Revisionism and the End of History (Abingdon: Routledge, 2020); Rachel E.Moss, ‘Teaching Medieval Chivalry in an Age of White Supremacy’, New Chaucer Studies, 3.2 (2022); David I Kertzer and Gunnar Mokosch, ‘The Medieval in the Modern: Nazi and Italian Fascist Use of the Ritual Murder Charge’, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, 33.2 (2019), 177–96. It can also be seen in the work of contemporary figures such as Anders Breivik, see: Mattias Gardell, ‘Crusader Dreams: Oslo 22/7, Islamophobia, and the Quest for a Monocultural Europe’, Terrorism and Political Violence, 26.1 (2014), 129–55.

46 Britain Awake. The Searchlight Archive, SCH/01/RES/BRI/13/008.

47 ‘Editorial’, The National European no. 17, November 1965.