ABSTRACT

Drawing on promotional materials in 2007–2008 and in 2021–2022, this article examines both Olympics to explore how the state has evolved in its governmental rationalities, and the related cultural and political implications. The 2022 Winter Games, despite its comparatively low profile and challenges posed by Covid-19, provided the Chinese state with a key moment to advance its confidence doctrine. Three discourses were mobilised pertaining to, first, the CCP’s superb leadership and problem-solving skills; second, China’s mega-infrastructure; and, third, created + made in China. The 2022 Olympics thus mobilised three confidence-driven discourses: leadership confidence, techno-scientific confidence, and creative confidence. In doing so, the 2022 Olympics envisioned, narrated, and materialised the popular discursive signifiers – technology, green and sustainability, and the future – the authorities already actively promoted in its political initiatives and policies. This contributed to the inward-oriented beliefs of self-reliance and self-improvement. Where we witnessed in 2008 a sense of curiosity and openness, within China and the world at large, we now face the complexities, dangers, and cultural essentialism, if not narcissism, of a confident China.

We have two focuses this time. The first is together for a better future. The second is unity. Our perspective is global, the mankind, it’s our [world]. Therefore, this is, in fact, a cultural confidence. (Zhang Yimou, the director of the opening ceremony of the 2022 and the 2008 Olympics, said in an exclusive interview on CCTV-13)Footnote1

Beijing the dual Olympic city

Zhang Yimou produced the opening ceremonies of both the 2008 and 2022 Olympics in Beijing. Whereas the first was, rather queerly, billed as China’s “coming out party,” the latter presented a confident and strong nation. Indeed, since the 2008 Summer Olympics, China has leapt forward with its technology-led political economy. With its steadily growing economy, its rise as a global power, China has demonstrated political and cultural confidence to the world. In fact, confidence has become a principal theme in the political philosophy of the Chinese Communist Party (thereafter, CCP) – known as the “confidence doctrine” – since Xi Jinping’s ascendency to the presidency in 2012.Footnote2 This “confidence doctrine” was officially written into the Party Charter in 2017.

This article examines this discourse of confidence of the CCP over the course of 14 years by zooming in onto the 2022 Winter Olympic Games, while reflecting upon the differences with the 2008 Olympics, that we have researched earlier (Chong Citation2017; de Kloet et al. Citation2008). We ask ourselves: how is the confidence doctrine translated towards the 2022 Olympics, and how does this differ from 2008, and what are the wider (geo)political and cultural implications?

Our analysis is built upon the promotional materials in 2007–2008 and 2021–2022. For the 2008 Olympics, we had conducted extensive ethnographic research that also included images (photos), official promotional materials and media reports we collected since November 2007 to November 2008. Due to strict COVID-19 measures, we could not conduct ethnographic research in the city in person in 2022. Our analysis draws on a parallel set of materials – the images taken in the city of Beijing from May 2021 to March 2022, official promotional materials (e.g. documentaries), and media reports from January to March 2022 – as for the 2008 Olympics.Footnote3 However, given the already available analyses of the 2008 Olympics (see, for example, Broudehoux Citation2007; Chong Citation2011; Citation2013a; Citation2013b; Schneider Citation2019), we focus in our analysis particularly on the 2022 materials.

Despite its comparatively low profile and challenges posed by COVID-19 and the growing critiques over sustainability and social responsibilities over the Olympics across the globe (Kobayashi et al. Citation2024), as we will show, the CCP continued to employ this mega-event in its population management and its geopolitical positioning (Schneider Citation2019). The confidence doctrine is articulated through three recurring discursive themes in the promotional materials and media reports, first, CCP’s superb leadership and problem-solving skills; second, the mega-infrastructures; and, third, created + made in China. These gesture towards three overlapping modes of confidence: leadership confidence, techno-scientific confidence, and creative confidence. Underpinning these discourses are the often vague and ambivalent discursive signifiers technology (keji), green (luse) and sustainability (kechixu), and the future (weilai). The authorities have been actively promoting these tropes in their political initiatives and policies, such as Common Prosperity, Made in China 2025, Ecological Civilisation, and Mass Entrepreneurship and Innovation.

The repetitive and assertive emphasis of “We” China, the CCP, and Chineseness being the answer and the solution to all kinds of challenges and difficulties in the 2022 Winter Games points towards an increasingly confident but also inward-looking gaze, one ridden with an essentialism, if not narcissism, as we will show. This inward-oriented positive feeling about oneself actively cultivates and encourages self-strength and self-reliance.Footnote4 This is markedly different from the more insecure and anxious China as we analysed during the 2008 Summer Games. Where we witnessed in 2008 a sense of curiosity and openness, within China as well as the world, we now face the complexities and dangers when an excessively confident and self-centred China gains currency in our times.

The dual Beijing Olympics offers an important empirical case study (and likely a cautionary tale) to roll back to Asia’s decolonisation efforts and to explore the paradox and dangers of becoming “inward-oriented” and “falling back” to the nation, and the related essentialised ideas of “China” and Chineseness. The central issue – “catching up” and being recognised to be on par with the West – that haunts Asia and China for over a century remains stubbornly present. A confident China appears powerful and self-assured for its population, and to the world. But is it really?

In what follows we will briefly discuss the vexed relationship between China and “The West” and related decolonisation efforts. This will then be followed by a visual and discursive analysis of the three confidence discourses mobilised by the state in the promotional materials of the Winter Games. Pointing to the dangers of essentialism and narcissism, we will then discuss the cultural and political implications from these two Olympics for China and the world.

From “catching up” with the West to a confident China

The dominance of the West has for a long time subjugated the rest to, epistemological and ontological, injustices and violence, as well as anxieties and desires of “catching up.” From the ideological critique of the West to the search for “methods,” intelligentsia in post-colonial studies and (Asian) cultural studies have been searching for ideas and tools to decolonise, to break the domination of the West in subjectivity formation over the past century (Chen Citation2010; Chua Citation2015; Fanon Citation1967; Iwabuchi Citation2020; Mizoguchi Citation2016; Takeuchi Citation2005; Walker and Sakai Citation2019).

Naoki Sakai (Citation2010), for instance, wrote against the West-defined area studies that created the binary of the West and the other in knowledge-production. Whereas Kuan-Hsing Chen (Citation2010) found ideological critiques not powerful enough to disrupt the existing orders. Inspired by Takeuchi Yoshimi’s 1960s lecture on “Asia as method,” Chen proposed to take Asia as “an imaginary anchoring point” (Citation2010, 212), and “emotional signifier” (213) that unites Asians together as a collective entity. Asia as method is not only a theoretical project but also a political strategy, a practice and an intervention to break the stubborn routine of looking upon the “superior” West. Rather, Asia as method proposes to draw references with the neighbouring countries, which share “common destinies” and past experiences. This “methodological” approach politicises Asian cultural studies by emphasising “inter-Asia referencing” as both a concept and an approach.

Meanwhile, other Asian cultural studies scholars witnessing the trans-national cultural exchanges, as well as the transformations brought forth by mobility and globalisation, have accentuated the importance of inclusivity, openness and coevalness (de Kloet, Chow, and Chong Citation2020; Iwabuchi Citation2016; Citation2020; Iwabuchi et al. Citation2004; Lo Citation2013). The transformation China has demonstrated through the two mega-events probes us to reflect and rethink the relationship between the state and society, China and the West, Asia and Europe, the past, the present, and the future.

Announced less than 6 months before the Winter Games started, the 2022 Olympics slogan, “Together for a shared future” (yiqi xiang weilai),Footnote5 – though resonating with CCP’s foreign-policy goal “community of common destiny for mankind” (renlei mingyun gongtongti) since 2012 – articulates a similar cosmopolitan sharedness and inclusivity, as the 2008 slogan, “One World, One Dream.” Yet, not quite. The word “dream” was mentioned in nearly all the 2008 Olympics promotion materials (Chong Citation2011). This dream was built upon the discourse of national humiliation and the haunting images of “the sick man of East Asia.” The notion of “one dream” was rightly critiqued for its authoritarian singularity: whose world are we referring to, and whose dream? (de Kloet and Scheen Citation2013). It seems, in retrospective, fair to say that “One Dream” spoke about the Chinese pursuit of “catching up” with the “One World” defined by the hegemonic West. Just as Mizoguchi critiqued Eurocentrism in 1989, “that the world was the method for China amounts to the world having been nothing but Europe” (Citation2016, 516). China in 2008 was mirroring itself against the Western standard.

China was not alone, as the official materials drew repeated references with the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and the 1988 Seoul Olympics to accentuate the importance of the Olympics to the ascendency of the two neighbouring countries: Japan and South Korea (Chong Citation2017). They too accelerated modernisation through “following” and “catching up” with the West. The 2008 Olympics demonstrated China and the CCP’s relentless efforts in performing its best to look and act on par with the West to be recognised and acknowledged as equals. China was, as political scientist Steinfeld infamously entitled his book Playing Our Games (Citation2010), following “a global system that we [the West] designed and that we dominate” (231). The city of Beijing was deliberately dressed up as a global city. “New Beijing, Great Olympics” was a slogan regarding the massive transformation taking place in Beijing. It was a time of frantic (re)building; consequently, cranes dominated the skyline, and the character “chai” – referring to its planned demolition – was all over the city. Ironically, China faced severe critique, often from the West, when moulding itself into the imagined modernised West.

Not only the cityscape but also Chinese citizens required transformation. The volunteers, taxi-drivers, and the ordinary people were subjects of suzhi (human quality) training and English language training. Their etiquette and behaviour were “corrected” through civility campaigns – for example, not to spit in public, queue orderly in public transport, speak English correctly to welcome foreign guests, and smile properly – to display a presentable China to the world (Chong Citation2011).

The state’s efforts in ensuring an impeccable Olympics could have motivated it to actively draw reference with the neighbouring Asian countries, to which Chua (Citation2015) called this referencing “Asian models.”Footnote6 We witnessed what we subjectively perceived as the process of Singaporisation of Beijing, as the city seemed to draw reference from Singapore and adopted authoritarian managerial practices of urban governance that made the city cleaner, tidier, more organised, efficient, and effective in daily operation. Singapore, as an authoritarian city–state, has rarely been critiqued; quite the contrary, its managerial governance has been positively received in the West. Inter-Asia referencing was both enabling as well disabling. Singapore may have been a source of inspiration, yet its “success” does not always get translated into similar effects/results, even among Asian countries with similar temporal and cultural dynamics. The Singaporisation of Beijing has accelerated since the 2008 Games, (re)gentrification has resulted in the exclusion of the low-end population in 2018, and the gradual “disappearance” of the un-representable in the city of Beijing.

China around 2008 was struggling with its inferiority complex: it was nervous, anxious, and insecure, but it was also a time full of curiosity, eagerness and excitement. This ontological and epistemological insecurity produced the desire for transformation, not a lack, as Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1984) reminded us, but a generative force that directed outward-looking exploration and inspiration. The successfully held 2008 Beijing Olympics gave China the sense of confidence it desired; and, unfortunately, it also advanced the discourse of “positive” authoritarianism (with Chinese characteristics) vis-à-vis the time-consuming and inefficient democracy. Realising the aspirational force of dream, the state pushed forward “the Chinese Dream” (zhongguo meng) in 2012.Footnote7 The Olympic dream has thus swiftly morphed into a Chinese dream within only four years.

De-colonisation runs the dangers of blindly “catching up” with the West, resulting in unproductive and frustrating results that reproduce inequality and domination. Unfortunately, this “alert” could easily flip into the opposite that privileges the “local” and the indigenous, the Asian-ness, and the “Chineseness” in this case. Critiques about cultural essentialism, such as Tu Wei-ming’s Cultural China: The Periphery as the Centre (Citation2005), have emerged since the 1990s (Ang Citation2001; Chow Citation1993); and yet, the heated discussion – seemingly “dated” in this age of technological progress and the constant pursuit of innovation and the “new” – remains relevant and perhaps, more urgent and concerning in recent years. Despite decades of deconstruction in academia, cultural essentialism has not waned at all, on the contrary, it is the glue that holds China together.

As Kobayashi et al. (Citation2024) pinpoint, the recent three consecutive Olympics from 2019 to 2022 were held in South Korea, Japan and China, all exclusively in East Asia, which could implicate an important shift of economic and geopolitical power from the West to the East. Meanwhile, the world is also witnessing an uncanny return of the familiar antagonism of the past, with a similar set of power-relations that mark the present: a return of the recognisable “old futures” (Hoyng and Chong Citation2022). Geopolitical tensions have been building up in the past few years, from Sino-US trade war to global suspicions on Chinese technology. These tensions could, to a great extent, reflect the anxieties the US (and the liberal West) have been facing upon the shifting economic and geopolitical order. China’s authoritarian rules and human rights violations in Xinjiang and Hong Kong further intensify the growing distrust between China and the liberal West. The diplomatic boycott – initially the US and Australia, then followed by the United Kingdom and Canada in December 2021 – could have further deteriorated China’s motivation in conjuring a more positive image on the global stage. This antagonistic tension has pushed China to resist the hegemonic West, building a stronger wall around itself.

When Mizoguchi proposed China as method, he asked his Japanese counterparts to be reflective and open as “to take China as a method is to take the world as a goal” (Citation2016, 516). He was wishing for a pluralistic world where China (as well as Europe) is one of the constitutive elements, not the dominant whole. We are now experiencing – unfortunately – the dangerous return of the either-or, an oppositional tension rather than an explorative, coeval, dyadic relationship. Our analysis not only reveals China’s changing rationalities in governance but more urgently, probes us to further engage with a call for transformation that is neither “catching up” nor “returning,” but realising the dyadic relationship between the past and the present, China and the West.

China’s triple confidence

Even taking the differences in popularity between the Summer and the Winter Olympics and the uncertainties brought by the COVID-19 pandemic into consideration, the relatively “low-profile” promotion for the Winter Games does suggest that China no longer depends on an Olympics – solely – to assert itself globally. Promotional materials were relatively scarce if we compared them to the year 2008. The subway stations were devoid of advertising, as new rules have been in place. From the summer of 2021, only months away from the Winter Olympics, and during the Tokyo Olympics in July–August 2021, one would come across commercial advertisements that sponsored the national team in Beijing, but, again, drastically fewer than compared to the 2008 Olympics. Now and then, one could find posters promoting some Winter Olympic sports in xiaoqu (residential communities/neighbourhood) but they were often mixed with other advertisements or public service advertisements. The 2022 Olympics were less of a spectacle;Footnote8 however, this mega-event remained significant for the CCP to communicate its political rationalities to the population, and the world.

The Opening Ceremony for the 2022 Games was scheduled for 4 February 2022. The number 4 (sì) is considered an inauspicious number, as it sounds like the word “death” (sǐ) in Chinese. This ominous date reflects a curious change in self-assertion, when comparing the country’s obsessive pursuit of the auspicious number 8 in 2008: the Opening Ceremony started at 8pm on 8 August 2008, with numerous experiments in controlling rainfall on that day. The number 8 (bā) sounds similar to fortune and prosperity (fā). It seems as if China was announcing to the world: China is strong, it no longer requires the mysterious forces of luck. More to that, the date was chosen to present a historical confident China. The organisers kick-started the ceremony by announcing its “the beginning of spring (lichun),” the beginning of a new year according to the more-than-3000-year-old lunisolar calendar. It symbolised the ancient scientific wisdom China has continuously narrated. As we have explained earlier, this discourse of confidence only intensified in the years after, especially after Xi Jining came to power, and culminated during the 2022 Olympics in three specific modes of confidence, related to leadership, technology, and creativity respectively. How does such a confidence look and feel like, and what are its implications for both China and the world at large?

CCP’s superb leadership and problem-solving skills: leadership confidence

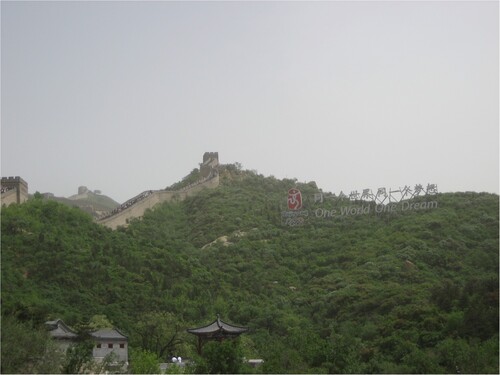

Already in 2008, China was proud on its achievements in preparing for the Olympics. It boosted the building – on time – of new venues, new subway lines, and a clean-up of the city as a whole. Its slogan “New Beijing Great Olympics” was just one of the multiple possible examples that celebrated the becoming of a new city and a new nation (see ). The new is always already entangled with the past, in this poster signified by juxtaposing the image of the Birds Nest with the temple of Heaven. The discourse of newness signifies a move away from the past, as such, it also reflects a discontent or insecurity, as if things have to change to secure a better future. When the past was invoked, it was usually the long durée that was privileged, whereas the revolutionary past was silenced. The slogan “One World, One Dream” was to be found everywhere, including the conspicuous sign displayed next to the Great Wall. Here the Olympics hark back to China’s alleged long history, symbolised by the Great Wall. But, somehow ironically, the letters also resonate with the famous Hollywood sign (see ). While this represents a confidence in the building of a new yet historically rooted city, and in a new China, compared to the 2022 Olympic, in 2008 there was more ambivalence as well as more openness to the world at large.

Already in October 2021, China announced that all the Olympics venues and related facilities were completed.Footnote9 China has become and wanted to appear more confident, and this confidence has been regularly and repetitively performed to ensure recognition, dissemination, and internalisation. This leadership confidence was discursively constructed in three aspects.

The first is through (re)presenting the unprecedented difficulties and challenges to accentuate CCP’s super leadership and problem-solving skills. Covid-19, a global health crisis, was such an unprecedented challenge. It resulted in the postponement of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics to the summer of 2021, with the Japanese government facing mounting calls for cancellation within Japan.Footnote10 The Chinese authorities ensured the Winter Games were held on schedule successfully, secured and controlled. It put forward effective and well-managed countermeasures, the recurrent slogan “simple, safe, and splendid” (jianyue, anquan, jingcai) presented the organising principle. It ensured the safety of the population and the Olympic participants by making the Games “simple.” The 19-day Games took place on a strictly secured “closed loop system,” participants were segregated from the city. Televised and broadcast online with high quality, there were nearly no spectators on sites.

The anti-COVID measures involved detailed and careful micromanagement: no community outbreaks during or after the Games. It was held, again, smoothly, and successfully with Team China ranking the third in the Olympics chart, China’s best-ever result at the Winter Games. The CCP is shown to be powerfully equipped with managerial wisdoms and solutions, not only leading China out of difficulties but also outperforming the general expectations, and the Western counterparts, especially in relation to counter-Covid measures.

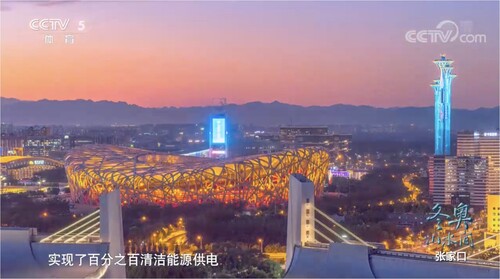

The second aspect is the forthright claims of excellence by the regular and repetitive use of superlatives in asserting China’s outstanding performance in organising the Winter Olympics. Beijing being the first and the only duo Olympic city, held within the time span of 14 years, was mentioned in almost all media materials (). The first Winter Olympics facing the COVID-19 pandemic was another regular highlight. Other notable examples are the first in the Olympics history to use 100 percent green energy (), the world’s first autonomous bullet train with a 5G live broadcast studio on board, the world’s first transcritical carbon dioxide (CO2) direct cooling technology in ice-making technology, the Shougang Park being the world’s most successful revitalisation example of Industrial Heritage, the newly built National Speed Skating Oval being the largest ice arena in Asia, the worlds’ first permanent venue for Big Air. Its pronouncement of being the first in history, the world’s first, the only, the longest, the fastest, the biggest, the most advanced, the best, so on and so forth, spells out an assertive, if not obsessive-compulsive, pursuit of supremacy vis-à-vis the (imagined) competitive counterparts/others.

Figure 3. Beijing: the first duo Olympics city (2022). Source: http://ent.people.com.cn/n1/2022/0123/c1012-32337641.html (accessed on 17 February 2022).

Figure 4. The 2022 Olympics would be the first in the Olympics history to use 100 percent green energy. Source: https://2022.cctv.com/2022/01/18/VIDENHYopjgqTumXVuoUmVrN220118.shtml?spm=C67245673465.P7DLnZmkcxGg.0.0 (accessed on 21 January 2022).

Often these superlative claims were spoken and accentuated by “Western” faces, despite its confidence, China apparently still wanted the affirmation of the desired Other – the Caucasian white men (). These white men, representing the West, were also mobilised to articulate the huge challenges China was facing. Apart from Covid-19, the organisation of Winter Olympics was shown to face numerous challenges, such as the making of snow and ice for the competitions, as the country had limited experience with winter sports. The “Western” experts were used to “dismiss” the critiques (CGTN, 16 January 2022).Footnote11 Also, the formation of medical teams for the Winter Games was marked as the first-ever. China (and these medical professionals) had no experience in Winter Sports medics, yet, their self-encouragement was “we need to perform much better than them” ().Footnote12 The “them” here referred to the imagined “experienced” Western counterparts that had years of Winter Sports emergency training. China’s confidence was reinforced by its resilience and strength in taking on unprecedented levels of difficulties and challenges in organising the well-operated Games.

Figure 5. Wolfgang Schädler, the head coach for the Chinese Luge team, said “This is unquestionably the world’s most splendid luge track.” Source: https://sports.cctv.com/2022/01/16/VIDEX49CQgo3tOiPukZGDujc220116.shtml?spm=C73465.PPhwmWKcKcH2.EKT5Lpy95bel.4. (accessed on 21 January 2022).

Figure 6. “We need to perform much better than them,” said the doctor in China’s first Winter Sports medical team (2022). Source: https://tv.cctv.com/2022/01/16/VIDEd2ZVWcDqSRLQTLebRpR8220116.shtml?spm=C55924871139.PT8hUEEDkoTi.0.0 (accessed on 21 January 2022).

This positive feeling about the CCP-led China is further advanced through the third aspect: The authorities’ thoughtful and visionary care for the general population, especially towards the rural (often the less developed and less well-offs) – in hosting the Winter Olympics, as orchestrated in the notion of a “People’s Olympics.” The CCP promised to direct and share the “high-quality” urban resources to the rural area. It would be frugal, minimising waste by reusing existing Olympics venues, on the one hand; and, on the other hand, it would further advance rural and tourism developments around Yanqing District and Zhangjiakou District. This rural development echoes with the CCP’s political call – “common prosperity” – to boost social equality. The Games were the platform to demonstrate the CCP-led governance that emphasises prudent practice, honesty with no corruption, openness, and sharing. The CCP presented itself as the government that cares for the people: not only economic development, but the authorities were also shown to care for the well-being of the children – the future generation – and the seniors, the general population by promoting winter sports in ordinary everyday life.

The flip side of care and protection is control. The CCP was shown repeatedly to be in full control – assuming the role of a paternal figure in the Chinese family – ensuring national securities and managing uncertainties and risks within and outside China. Challenges as well as global critiques of China become important to justify CCP’s leadership and control in the name of security and protection. China’s leadership confidence discourse orchestrated a dependency towards the CCP leadership. The Olympics boosted China’s confidence, yet the positive feelings about the CCP-led China may be a little too good, and too much inflated, running the danger that China, and the Chinese population, locks itself up within its own vision.

Mega-infrastructures: techno-scientific confidence

The 2008 Olympics involved a radical restructuring of the city. This also involved the destruction of old hutongs, images of which circulated widely (see ), to make place for new subway stations or parks. The building of the new city was often hazy, as the city of Beijing was suffering from strong air pollution (see ). The pollution only intensified in the years after, to decrease in the late 2010s after drastic measures were taken by the government. The building of a new Beijing thus came at a price, signified by destruction and pollution, but 14 years later during the Winter Olympics, we witness a much more confident commitment to techno-scientific progress.

Emphasising China’s commitment to sustainability, the official budget for the 2022 Winter Olympics was set at USD3.9 billion, the cheapest Olympics in the last two decades (Insider, 30 January 2022). Nonetheless, reports have cast doubt about the “real” cost as numerous infrastructure projects have been built, including Daxing International Airport, high-speed rail, and competition venues around Yanqing District and Zhangjiakou District. Although they do not quite alter the cityscape as much as the venues did in 2008, massive transformations happened in Yanqing and Zhangjiakou. Again, these infrastructural projects were finished well ahead of schedule, and smooth-functioning for the Winter Games, thus performing a capable and well-organised China.

Mega-infrastructures are important visual symbols of excellence. Large-scale infrastructural projects have been central in projecting CCP’s modernisation achievements and asserting its legitimacy, to which anthropologist Johnathan Bach calls China “the paradigmatic infrastructural state” (Citation2016). In preparation for the 2008 Olympics, infrastructural projects such as metro systems, roads, the Olympics venues, the Olympics Green, the central business district (CBD), (re-)gentrification of urban Beijing (e.g. hutongs) were built to present a modernised China. Mega-infrastructures are materialised systems that concretely demonstrate the authorities’ scientific knowledge and technological know-how, as Vivienne Shue argued, both are “morally sound and good” (Citation2010, 50) for acquiring modernisation-enabled legitimacy.

Infrastructure divides the developed from the developing/underdeveloped. Anthropologist Brian Larkin argues that an analysis of infrastructures cannot be separated from the civilisation history and our belief and imagination of human mastery: “infrastructures bring about change, and through change they enact progress, and through progress we gain freedom” (Citation2013, 332). It is this sense of empowerment that generates “desire and awe in autonomy of its function” (Citation2013, 333). Infrastructure is inseparable from modernisation, to which developing societies have been working hard to catch up (Edwards Citation2003; Rankin Citation2009).

China is not alone. Cities and nations “copy” infrastructural projects, in Larkin’s words, “to participate in a common visual and conceptual paradigm of what it means to be modern” (Citation2013, 333). This “copying” is so common that Dalakoglou (Citation2010), in his study of Albania, calls this obsession “infrastructural fetishism.” The modern Olympics also provides such a platform, as well as a justification for infrastructural projects. In China, not only are these infrastructures built for their aesthetic modernised symbolic looks, they are also made to perform superbly to showcase CCP’s excellent techno-scientific management. They boost China’s techno-scientific confidence.

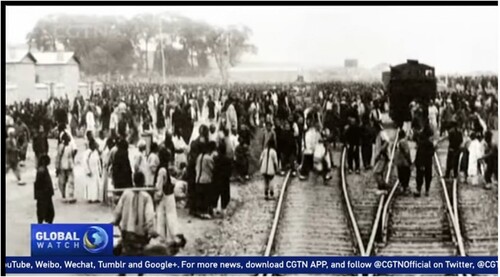

The high-speed train that was built to connect the three Olympic sites was one of the exemplary cases, demonstrating the ruling authorities’ achievements.Footnote13 This achievement was magnified by and through the juxtaposition of the past and the present. A black-and-white image of the construction of the railway in pre-modern China () is juxtaposed with the recently built ultra-modern bullet train station (), the contrast amplifies the achievements of the current state. Images of this bullet train, framed against the natural surroundings, present strikingly similar images of the world’s fastest Japanese bullet train with Mount Fuji in the background. China looks and performs – infrastructurally – so magnificently like the modernised Japan, though the latter would not be mentioned and compared openly and publicly.

Figure 9. The construction of China’s first railway in pre-modern time. Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=upfuhOLqY4c&list=PLryvsQ9JUl__OC1x4srHQcw6NiPK3NOb1&index=6. (accessed on 16 February 2022).

Figure 10. China’s custom-made bullet train for the 2022 Olympics. Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=upfuhOLqY4c&list=PLryvsQ9JUl__OC1x4srHQcw6NiPK3NOb1&index=6. (accessed on 16 February 2022).

Aside from the material structures, the authorities have also infrastructuralised created-in and made-in-China technologies to ensure a highly functional well-operated Winter Games. The bullet train was the first to have a 5G technology in ultra-high-definition (UHD) live broadcast: superb quality in superb speed! The Olympics indeed was a stage to showcase how China has morphed from being a factory of the world towards a place of technological innovation. Official materials employed the popular discourse of “heikeiji” (black technology) to create a marvellous sense of “futuristic technologies only portrayed in science fiction narratives” (de Seta Citation2021) in China’s innovative technologies. It mystifies and generates a desire for exceptional technology, in describing the advanced technologies being mobilised in the Winter Games.

The infrastructuralisation of technologies was accelerated and amplified in the wake of the counter-COVID measures. The “closed loop system” was set to ensure safety and to minimise physical contact. Within the Olympics sites, unmanned stores were set up; while robots were put to perform a broad range of tasks, including preparing and serving meals and drinks, performing security duties, hotel check-in, and translation. Platform applications became indispensable, including cashless payment and health monitoring (through the “My2022” smartphone app).

The 5G wireless network technology was hailed as the basic infrastructure for the well-functioning technological and communication system. The Olympics was not open to the public, audiences could only watch in distant yet clearly through cutting-edge technologies – 4 and 8 K UHD – at home or huge display-screens in the city. This was said to be a 5G-assisted high-definition cloud broadcast mega-event, with a free visual-angle spectator experience. To promote Winter Sports, virtual reality experiences were provided by the organisers. Even a non-sport item like the torch was operated by eco-friendly hydrogen; while sports uniforms were technologically enhanced to improve athletes’ performances. Created-in- and made-in-China technologies are narrated as essential solutions to all situations China face. The words of Zhang Yimou allude to the magical – or, (dis-)illusional – functions projected on the relationship between China and technologies: “We will use the power of technology to make sure that the stadium, even with a lot less people, does not look empty, we will make it ethereal and romantic at the same time.”Footnote14 Technology-based, and -built infrastructures, just like the material systems, promise the arrival of modernity, and help boost China’s confidence. No questions or doubts, or any critical reflection and enquiries, regarding the use of technologies, are encouraged, ushering the country into a state of technological bliss.

Created + Made in China: creative confidence

Starting from bidding the Winter Olympics, we need to respond to global communities’ concerns, from climate change to environmental protection, to concerns over sustainability, we [China] must give them a Chinese response/answer. (Prof. Zhang Li, Dean of the School of Architecture of Tsinghua University, designer of “Snow Ruyi,” and the chief planner of the Zhangjiakou Winter Olympics sites)Footnote15

The 2022 Winter Games stood in stark contrast: barely any global celebrity architect was included in the process, except the late Zaha Hadid who designed Daxing International Airport, but her presence was barely mentioned in the media materials. In 2008, China asserted itself by “borrowing” the fame of the Western architects and allowed them to “experiment,” in some cases, “duplicate” their designs so that Beijing could look like a global city. It was also around this period that the (soft-)power of creativity started drawing official attention. The global discourses of creativity and tech-driven innovation have advanced over the years, and both have been actively mobilised in China’s political initiatives in the past decade.

The mobilisation of creativity and innovation has been a political mandate, first, to correct, getting rid of the embarrassing image of China-as-pirate-nation, and the derogatory meanings associated with “copying,” in Pang’s words, “copying – in its many forms of piracy, plagiarism and forgery – is demonised as unimaginative, lazy theft” (Citation2008, 118). Second, China has learnt how to play the game, following the rules of the global (mostly, Western) knowledge economy that celebrates newness and that dramatises the effects and achievements of progress. Created- and Made-in-China (guochan), is a declaration that China has the mind, resources and skills for leadership and self-reliance.

The Sino-US tech tensions since 2018 have shown how creativity and innovation have been weaponised in the level of geopolitics and national security. They have enabled the authorities to mobilise the discourse of “the West fears China’s rise,” and further accelerated the country’s popular belief that creativity and innovation are indispensable to modernisation and China’s ascendency to superpower status. The 2022 Olympics presented the platform to harbour creativity- and innovation-driven confidence and self-reliance.

During the 2022 Olympics, China tried to write off the visual traces of “following” or “copying” the imagined West/others.Footnote16 Regarding the competition venues, the promotion materials emphasised entirely their Chinese-inspired elements. Labelled as the “Flying Snow Dragon,” the National Sliding Centre for bobsled, skeleton and luge events has a 360-degree Chinese mythical dragon-shaped track (). Whereas, the National Ski Jumping Centre is dubbed as “Snow Ruyi” () as it resembles a traditional Chinese auspicious sceptre-like object that symbolises “good luck” (Global Times, 17 February 2022). Both were designed by Chinese architects.

Figure 11. The 360-degree Chinese dragon-shaped National Sliding Centre (2022). Source: https://sports.cctv.com/2022/01/16/VIDEX49CQgo3tOiPukZGDujc220116.shtml?spm=C73465.PPhwmWKcKcH2.EKT5Lpy95bel.4. (accessed on 21 January 2022).

Figure 12. “Snow Ruyi,” the National Ski Jumping Centre (2022). Source: https://2022.cctv.com/2022/01/18/VIDENHYopjgqTumXVuoUmVrN220118.shtml?spm=C67245673465.P7DLnZmkcxGg.0.0 (accessed on 21 January 2022).

The priority in the process of planning and design, however, lies not so much in the “look,” but more in China’s commitment to the slogan-turned “Green Olympics.” All the construction projects were designed and made to meet the principles of green, low-carbon sustainable development. The designer of “Snow Ruyi,” Prof. Zhang said:

We hope to present the Chinese idea of nature, which is to say, the harmonious symbiosis between man and nature, through the Snow Ruyi. We tried to minimise the footprint of artificial interventions upon the existing landscape, making our building blend in with the overall environment … We’ll also keep a close eye on post-Games usage of these venues, and if conditions permit, we’ll ask the public to help us record the post-Games life of these venues. We have done some preliminary studies so far, but the true test is the real life after the Games.Footnote17

Figure 13. The Chinese ecological philosophy “the harmonious symbiosis between man and nature” repeatedly shown during the 2022 Winter Olympics. Source: https://sports.cctv.com/2022/01/16/VIDEX49CQgo3tOiPukZGDujc220116.shtml?spm=C73465.PPhwmWKcKcH2.EKT5Lpy95bel.4. (21 January 2022).

The Winter Olympics was made to serve as “an ecological model”Footnote18 that showcased the CCP-led vision of a green future and a sustainable living environment for the population. The authorities demonstrated a strong awareness of the environmental impact, declaring how they did their best to mobilise numerous well-thought, and expert-advised (techno-)scientific measures to avoid “irreversible changes” and minimise “ecological disruption.”Footnote19

Measures taken in relation to the protection of the natural environment include, first, scientific evaluations of the Olympic sites, led by university professors and students. These were conducted to access the ecological impact and present a thorough plan to retain biodiversity in the area before construction started. Second, ecological restoration went hand in hand with the venue-construction projects, e.g. preserve the existing soils, plants and trees, and the overall ecosystems by transplanting them in the nearby area as the preferred measures.

Often, poetic Chinese language – “shanshui yijiu, feiniaoguilin” (Similar landscape as before, birds return home), “jin ziran, qiao yinjie” (close to nature, skilful borrowing), “qiaoyu yinjie, jingzai tiyi” (skilful borrowing, appropriate application) and “suiyou renzuo, wanzi tiankai” (created by mankind, similar to the nature) – is used as to inject the ecological civilisation with the right dose of aesthetic and linguistic Chineseness.

The creative and ecological confidence of the CCP was also articulated through the Olympic venues. First, the eight existing 2008 Olympic venues were reused, for example, the National Aquatics Centre (Water Cube) was remodelled into Ice Cube for ice sports. Second, existing buildings were modernised, for example, Shougang, the former state steel mill, was “revitalised” and transformed into Shougang Park with the towering jump for the 2022 Games and “a high-end industrial innovation highland in western Beijing and a post-industrial cultural and sports creative base in the future” (“Shougang Park,” Citationn.d.). Third, so-called “intelligent” architectural designs were used. For instance, by integrating the natural landscape in the structure of “Snow Ruyi” without serious alteration of the environment (), and by incorporating the Chinese architectural design of having a wooden roof onto the National Sliding Centre to keep track frozen and therefore to minimise energy consumption. Fourth, the authorities claimed to aim to reduce and recycle materials. One prominent example concerns snow production, facing critique of a mass waste of energy and water, the authorities showed how the water used would be recyclable and reusable through a reservoir in the same area. Another example was the installation of gabion walls, to minimise transportation of stone, waste and soil outside the area ().

Figure 14. Using 95 percent of the original landscape without alteration (2022). Source: https://2022.cctv.com/2022/01/18/VIDENHYopjgqTumXVuoUmVrN220118.shtml?spm=C67245673465.P7DLnZmkcxGg.0.0 (accessed on 21 January 2022).

Figure 15. The use of gabion wall as decoration and structural support (2022). Source: https://sports.cctv.com/2022/01/16/VIDEX49CQgo3tOiPukZGDujc220116.shtml?spm=C73465.PPhwmWKcKcH2.EKT5Lpy95bel.4. (accessed on 21 January 2022).

In 2022, we witnessed the marriage of two Olympics concepts, namely “Green Olympics” and “Hi-Tech Olympics.” In official promotion material, “Going Green” was (mis-)translated to “keji tian dongle” (literally “technology adds power”). This may suggest the intimate and mingling relationship between both concepts “Green/Ecological” and “technology” for the organising authorities. Technology was presented as the scientific-proven solution to China’s commitment of ecological preservation and protection, as official banners displayed the following slogans: “Smart Construction, Green Development” (see ); “China construction, constructing the future.”

Figure 16. “Smart Construction, Green Development” (2022). Source: https://tv.cctv.com/2022/01/15/VIDElAPBxLLAajSP7patk4Ql220115.shtml?spm=C55924871139.PT8hUEEDkoTi.0.0 (25 May 2022).

Technology is presented as panacea for the man-made disruption to the environment and the nature. Innovative and creative technologies, “smart” designs with “smart” use of materials – the selection as well as the minimum use of resources in infrastructure and venue-construction – were presented as scientific and technological-sound solutions to these concerns. Numerous Chinese world-class, advanced, techno-scientific innovative measures were demonstrated.

First, regarding artificial snow: China emphasised it is not the first one to use artificial snow; but it was the one offering the best solutions by a Chinese technology research team, led by the Chinese Academy of Sciences scientist, Qin Dahe. Ice was created and made via the innovative, eco-friendly, safe, and low-cost transritical CO2 technology, invented by Peking University professor, Zhang Xinrong ().

Figure 17. Carbon dioxide transcritical direct cooling ice-making, Created-in-China; while the white man is reduced to the role of operator (2022). Source: http://ent.people.com.cn/n1/2022/0123/c1012-32337641.html (accessed on 17 February 2022).

Second, clean energy, such as solar energy and windmills, was used to power the whole event. China fulfilled its promised by powering the whole Olympics through green energy. Third, low carbon emission was promoted throughout, claiming to help lift poverty, quality of living, and transform the economy. The sophisticated hi-tech climate control platform ensures efficiency, minimising energy consumption. Electric autonomous vehicles were widely used within the Olympics sites. Degradable materials were used for cutleries and plates, and paper tickets were replaced by e-tickets.

This nationalised creative discourse was enhanced through the appearances of confident, mostly “young,” well-dressed, well-versed presentable, above all, Chinese professionals and experts, both men and women (), such as university professors, architects and alike. Prof. Zhang Li, mentioned in the quotation above, was a representative example, speaking fluently and eloquently in an RP-like English accent with humour and wit in a CCTV interview.Footnote20

Figure 18. Zhang Yuting, born in the 1980s, was one of the architects of “Flying snow dragon” (2022). Source: https://sports.cctv.com/2022/01/16/VIDEX49CQgo3tOiPukZGDujc220116.shtml?spm=C73465.PPhwmWKcKcH2.EKT5Lpy95bel.4. (accessed on 21 January 2022).

The challenges and difficulties that emerged from organising the 2022 Winter Olympics were described and accentuated as “special” conditions that required and could only be effectively resolved through Chinese creative and technological-innovative solutions, for the benefit of the people and the country. These Created-in- and Made-in-China measures asserted the population that China is always in control, regardless the challenges. All this helps cultivate strong positive feelings about the national achievements, China is strong, full of creative confidence, and it does not rely on others; while the others would need China because of its creativity and innovation.

Together for a shared future?

The 2022 Olympics took place against a backdrop of increased global connectedness and antagonism. Communication innovations, such as social media, did not bring the openness many expected, and a looming shifting world order creates fear that intensifies geopolitical tensions. The rise of Xi Jinping has marked a move towards a more assertive, more confident, and more controlling China. The Belt and Road initiative speaks of China’s eagerness to connect with the world, beyond the hegemonic West. Technological developments have accelerated China’s global economic power, reshaping the country’s self-image as a leading scientific-technological superpower that is no longer lagging behind or merely a copycat of the West. China does not need the world as much as it did before, so it seems. In the CCP’s centenary celebration during the summer of 2022, Xi made international headlines again by warning against external threats that “will have their heads bashed bloody against a Great Wall of steel forged by over 1.4 billion Chinese people.”Footnote21

The confidence doctrine that we have analysed in this article, with its three different yet overlapping articulations in leadership confidence, techno-scientific confidence and creative confidence, signifies a movement from looking outwards in 2008 to moving inwards by 2022. With hindsight, the not-so-confident China in 2008 was nervous and eager to look outwardly for its self-strengthening aspiration. This engendered optimism and excitement, leaving the impression that China could become more open and more democratic. Not only did the state agree to give more room for “dissensus” by assigning public protest zones and lifting internet bans on, for example, Facebook and the international press, but it also promoted the rise of a “creative China” through zones like 798 and the transformation of hutongs into creative spaces. It was also the year that Ai Weiwei became a global celebrity, and there was a space for different cultural productions to question the Olympic dream. Ou Ning’s documentary Meishi Street (2006) portrayed, for example, the resistance of the local inhabitants of a street in the centre of Beijing against forced demolition (de Kloet Citation2016). Migrant workers released a CD titled “Our World, Our Dream” (de Kloet and Scheen Citation2013). With hindsight, the possibility of such a clear protest, as well as the making and screening of this documentary in China, and the release of such a CD, attests to the relatively open atmosphere.

In 2022, China actively promoted an “inward” approach by emphasising “self-reliance” and “self-strengthening.” We thus wonder, could it be that China is becoming a bit too confident? Or, in other words, does the doctrine of confidence lead to increased cultural narcissism? China’s inward-looking process is uncannily projected in the popular buzzword “neijuan” (involution) that emerged in recent years. Although neijuan/involution refers to the zero-sum game generated by stiff competition in China, its broader implication of stagnation, as implicated in Geertz’s theory of agricultural involution (Citation1963), does present a warning tale. Growth in a politically cultivated confidence in China, as mediated through the 2022 Beijing Olympics, does not necessarily generate growth in the country’s overall advancement. The current economic crisis, with an increasing number of youth unemployment and a highly instable real estate market, attests to this.

A paradoxical condition has thus emerged: the more confident China seems to be, the more global contestations it is confronted with; the more bullied and humiliated it feels, the more urgently it feels the need to assert itself; the more control it imposes within the country and in international relationships, the harder it is for it to acquire the soft power it longs for. The confident China of the 2022 Olympics is one that is more closed as well as more contested internationally, whereas the less confident China of 2008 is one that is more open, and to which the world was also more curious.

The confidence doctrine essentialises China and sets it apart from other countries in its reification of Chineseness. Compared to 2008, it seems as if the world has moved backward, or, should we say, more realistic? Maybe the cosmopolitanism of the 2008 Games were merely a guise, an empty façade, devoid of meaning, and maybe the current more antagonistic and more confident performance of “China” helps to question the power and hegemony of that other narcissist state, the United States? The 2022 Olympic Games put afront the prolonged and antagonistic divide of the East–West. How to search for ways to curb the extension of the “old futures”? Can one say no to the haunting return of the old futures? What has engendered the Chinese state’s obsessive pursuit of its confidence boost in the past few years? Our study has mapped three discourses that jointly constitute the confidence doctrine. Clearly, the Olympics help to shape the geopolitical power of China, especially inwardly, towards its own citizenry.

China’s cultural and political confidence might no longer require a massive celebration of the Olympics; yet, the Winter Olympics motto does reflect its awareness – and the global discursive rhetoric – of the importance of sharedness and global cooperation for China and the world. We suggest two forms of inter-Asia referencing that may help to foster cooperation rather than unbridled confidence, the first related to previous Olympics that were held in Asia, the second to the aftermath of the COVID-19 lockdowns in 2022. Indeed, perhaps it is now more urgent than ever to inter-reference with the democratising experiences of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and the 1988 Seoul Olympics in Japan and South Korea. Second, the COVID-19 protests that unfolded in China at the end of 2022, resulting in the empty A4 demonstrations, also suggest that the leadership may have been somehow a bit too confident in itself, and in its power to control wisely and benevolently. Rather than talking and writing endlessly about geopolitics in abstractum, it may be more fruitful to explore, with history as a method, what untapped potentials the Olympics, and the events unfolding during the Olympic years of 2008 and 2022, may still hold for China and the world.

Special terms

Acknowledgements

Both authors would like to thank the editors and anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Gladys Pak Lei Chong

Gladys Pak Lei Chong is Associate Professor of the Department of Humanities and Creative Writing, Hong Kong Baptist University. She is the author of Chinese Subjectivities and the Beijing Olympics (2017), co-editor of Trans-Asia as Method: Theory and Practices (2020) and Critiquing Communication Innovation (2022). Some of her journal articles have appeared in Global Media and China, Visual Studies, Science, Technology and Society, The Information Society, Chinese Journal of Communication, China Information, International Journal of the History of Sport, and Journal of Current Chinese Affairs. Her research on youth aspirations, and technology, security, and risk are funded by the Hong Kong Research Grant Council.

Jeroen de Kloet

Jeroen de Kloet is Professor of Globalisation Studies at the Department of Media Studies at the University of Amsterdam. Publications include a book with Anthony Fung Youth Cultures in China (Polity 2017), and the edited volumes Boredom, Shanzhai, and Digitization in the Time of Creative China (with Yiu Fai Chow and Lena Scheen, Amsterdam UP 2019) and Trans-Asia as Method: Theory and Practices (with Yiu Fai Chow and Gladys Pak Lei Chong, Rowman and Littlefield, 2019). His new book is It's My Party – Tatming Pair and the Postcolonial Politics of Popular Music in Hong Kong (with Yiu Fai Chow and Leonie Schmidt, Palgrave, 2024).

Notes

1 Zhang’s response here was very much rehearsing (reading) CCP’s recent political ideas: “community of common destiny for mankind” and cultural confidence.

2 It initially only has “three confidences” (sange zixin) that urge the population to have confidence in “path, political system and guiding theories” of CCP. “Cultural confidence” and “historical confidence” were added to “the Three Confidences” in 2016 and 2021 respectively. https://www.12371.cn/special/zggcdzc/zggcdzcqw/ (accessed on 1 June 2022).

3 These cover both official and commercial media materials, including 10 traditional and new social media channels, from the People’s Daily, Xinhua, Global times, Beijing Daily, CCTV, to Douyin, Kuaishou, Weibo, WeChat and Zhihu.

4 Focusing on sport, Brownell (Citation2023) believed that China has become more integrated into the world order, “more open, and less xenophobic” (25). Taking a different focus on the population management and China’s geopolitical positioning, our analysis unveils a different argument from Brownell.

5 This slogan replaced the original slogan “Joyful Rendezvous Upon Pure Ice and Snow” (chunjie de bingxue, jiqing de yuehui), which was lengthy and less captivating. The contrast in slogan promotion between 2008 and 2022 is revealing.

6 Chua (Citation2015) pinpointed that Asian countries and cities have been referencing with their neighbours, and China in particular with Singapore, in his words, “China would like to replicate, if possible, despite the difference in scale, Singapore’s success in captiatlist development while maintaining a non-corrupt, elected, single-party dominant state power with a high degree of electoral popularity, and hence legitimacy to govern” (74).

7 “The Chinese Dream” (zhongguo meng) was officially promoted by Xi Jinping (general secretary of the Communist Party of China) in 2012. Tracing the population management strategies since the Olympics, it is not hard to observe that the word “dream” has ascended to its socio-cultural and political significance through its hugely popular use in the Olympics promotions (e.g. slogans like “One World, One Dream” “tongyi shijie tongyi mengxiang,” posters, and media productions like Dream Weaver (zhu meng, 2008). Dream Weaver, directed by Gu Jun, was the official Olympic documentary, supported by the Beijing Organizing Committee for the Games of the XXIX Olympiad (hereafter BOCOG).

8 It is important to note that in general, the summer Olympics always attract more attention worldwide when compared to the Winter Olympics.

9 #Beijing2022 Winter Olympic venues complete construction (29 October 2021). People’s Daily, China. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QmQX_3tlbWo&list=PLryvsQ9JUl__OC1x4srHQcw6NiPK3NOb1&index=5.

10 The Japanese government was severely criticised for not cancelling the 2020 Games. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-57911122.

11 Zheng, Y. (16 January 2022). Experts dismiss criticisms of artificial snow for Beijing 2022. CGTN. Retrieved from https://news.cgtn.com/news/2022-01-16/Experts-dismiss-criticisms-of-artificial-snow-for-Beijing-2022-16S1qD785HO/index.html.

12 From Beijing to Beijing: Second Episode Kind-hearted Chinese Medical Teams (2022). Retrieved from https://tv.cctv.com/2022/01/16/VIDEd2ZVWcDqSRLQTLebRpR8220116.shtml?spm=C55924871139.PT8hUEEDkoTi.0.0.

13 High Speed Railway for 2022 Winter Olympics in construction (18 April 2018). CGTN. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=upfuhOLqY4c&list=PLryvsQ9JUl__OC1x4srHQcw6NiPK3NOb1&index=6.

14 Winter Olympics Approaching: Interviews with Director Zhang Yimou (2022). In CCTV-13. Retrieved from https://tv.cctv.com/2022/01/21/VIDEb9Jj04JVEHeHA7l0EkkH220121.shtml.

15 Winter Olympics Landscape: Zhangjiakou (2022). CCTV. Retrieved from https://2022.cctv.com/2022/01/18/VIDENHYopjgqTumXVuoUmVrN220118.shtml?spm=C67245673465.P7DLnZmkcxGg.0.0.

16 In 2008, the official materials would selectively “forget” foreign architects when mentioning the iconic architectural buildings (Chong Citation2017, 148).

17 Chen, Xi. (16 February 22). "Snow Ruyi'” designer reveals how Olympic venue showcases beauty of Chinese culture. Global Times. Retrieved from https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202202/1252388.shtml#:∼:text=%22We%20established%20the%20image%20of,Chinese%20culture%2C%22%20Zhang%20said.

18 Winter Olympics Landscape: Yanqing District (2022). CCTV. Retrieved from https://sports.cctv.com/2022/01/16/VIDEX49CQgo3tOiPukZGDujc220116.shtml?spm=C73465.PPhwmWKcKcH2.EKT5Lpy95bel.4.

19 Winter Olympics Landscape: Zhangjiakou (2022). Retrieved from https://2022.cctv.com/2022/01/18/VIDENHYopjgqTumXVuoUmVrN220118.shtml?spm=C67245673465.P7DLnZmkcxGg.0.0.

20 Watch it again: Looking ahead to Beijing Winter Olympics (2022). Retrieved 24 February 2022 from China Daily website: https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202112/24/WS61c550e8a310cdd39bc7d49d.html.

References

- Ang, Ien. 2001. On Not Speaking Chinese: Living Between Asia and the West. London: Routledge.

- Bach, Jonathan. 2016. “China’s Infrastructural Fix.” Limn, 7. https://limn.it/chinas-infrastructural-fix/.

- Broudehoux, Anne Marie. 2007. “Spectacular Beijing: The Conspicuous Construction of an Olympic Metropolis.” Journal of Urban Affairs 29 (4): 383–399. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9906.2007.00352.x.

- Brownell, Susan. 2023. “How China’s Two Olympic Games Changed China and the Olympics.” In Sports Mega-Events in Asia, edited by Koji Kobayashi, John Horne, Younghan Cho, and Jung Woo Lee, 23–46. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Chen, Kuan-Hsing. 2010. Asia as Method: Toward Deimperialization. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Chong, Gladys Pak Lei. 2011. “Volunteers as the ‘New’ Model Citizens: Governing Citizens through Soft Power.” China Information 25 (1): 33–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/0920203X10393212.

- Chong, Gladys Pak Lei. 2013a. “Chinese Bodies That Matter: The Search for Masculinity and Femininity.” International Journal of the History of Sport 30 (3): 242–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2012.754428.

- Chong, Gladys Pak Lei. 2013b. “Claiming the Past, Presenting the Present, Selling the Future: Imagining a New Beijing, Great Olympics.” In Spectacle and the City, edited by Jeroen de Kloet and Lena Scheen, 135–155. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam.

- Chong, Gladys Pak Lei. 2017. Chinese Subjectivities and the Beijing Olympics. London: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Chow, Rey. 1993. Writing Diaspora Tactics of Intervention in Contemporary Cultural Studies. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Chua, Beng Haut. 2015. “Inter-Asia Referencing and Shifting Frames of Comparison.” In The Social Sciences in the Asian Century, edited by Carol Johnson, Vera Mackie, and Tessa Morris-Suzuki, 67–80. Acton: Australian National University.

- Dalakoglou, Dimitris. 2010. “The Road: An Ethnography of the Albanian-Greek Cross-Border Motorway.” American Ethnologist 37 (1): 132–149. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1425.2010.01246.x.

- de Kloet, Jeroen, Gladys Pak-Lei Chong, and Wei Liu. 2008. “The Beijing Olympics and the Art of Nation-State Maintenance.” Journal of Current Chinese Affairs 2: 5–35

- de Kloet, Jeroen. 2016. “Rescuing History from the City.” In Cities Interrupted – Urban Space and Visual Culture, edited by Christoph Lindner and Shirley Jordan, 31–48. London: Bloomsbury.

- de Kloet, J., Yiu Fai Chow, and Gladys Pak Lei Chong. 2020. Trans-Asia as Method: Theory and Practices. London: Rowman and Littlefield.

- de Kloet, Jeroen, and Lena Scheen. 2013. “Pudong, the Shanzhai Global City.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 16 (6): 692–709. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549413497697.

- de Seta, Gabriel. 2021. “A New AI Lexicon.” Accessed November 20, 2022. AI Now Institute website: https://medium.com/a-new-ai-lexicon/heikeji-黑科技-black-technology-4b04fdda2338.

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Felix Guattari. 1984. Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. London: Athlone.

- Edwards, Paul N. 2003. “Infrastructure and Modernity: Force, Time, and Social Organization in the History of Sociotechnical Systems.” In Modernity and Technology, edited by Thomas J. Misa, and Philip Brey, 185–225. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Fanon, Frantz. 1967. Black Skin, White Masks. New York: Grove Press.

- Geertz, Clifford. 1963. Agricultural Involution: The Processes of Ecological Change in Indonesia. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Hoyng, Rolien, and Gladys Pak Lei Chong. 2022. “Introduction: New, Old, and Uncertain Futures.” In Critiquing Communication Innovation, edited by Rolien Hoyng and Gladys Pak Lei Chong, ix–xxxiv. Michigan: Michigan State University Press. https://doi.org/10.14321/j.ctv2cmr97c.

- Iwabuchi, Koichi. 2016. “Trans–East Asia as Method.” In Routledge Handbook of East Asian Popular Culture, edited by Koichi Iwabuchi, Eva Tsai, and Chris Berry, 276–294. London: Routledge.

- Iwabuchi, Koichi. 2020. “Trans-Asia as Method: A Collaborative and Dialogic Project in a Globalized World.” In Trans-Asia as Method: Theory and Practices, edited by Jeroen de Kloet, Yiu Fai Chow, and Gladys Pak Lei Chong, 25–42. London: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Iwabuchi, Koichi, Stephen Muecke, and Mandy Thomas. 2004. Rogue Flows: Trans-Asian Cultural Traffic. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

- Kobayashi, Koji, John Horne, Younghan Cho, and Jung Woo Lee. 2024. “Introduction to the Special Issue: Mediating the East Asian Era of the Olympic Games (2018–2022).” Communication and Sport 12 (1): 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/21674795231208363.

- Larkin, Brian. 2013. “The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure.” Annual Review of Anthropology 42 (1): 327–343. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-092412-155522.

- Lo, Kwai Cheung. 2013. “Rethinking Asianism and Method.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 17 (1): 31–43.

- Mizoguchi, Yuzo. 2016. “China as Method.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 17 (4): 513–518. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649373.2016.1239447.

- Pang, Laikwan. 2008. “China Who Makes and Fakes.” Theory, Culture & Society 25 (6): 117–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276408095547.

- Rankin, William J. 2009. “Infrastructure and the International Governance of Economic Development, 1950–1965.” In Internationalization of Infrastructures: Proceedings of the 12th Annual Conference on the Economics of Infrastructures, edited by Jean-Francois Auger, Jan Jaap Bouma, and Rolfe Kunneke, 61–75. Delft: Delft University of Technology.

- Ren, Xuefei. 2008. “Architecture and Nation Building in the Age of Globalization: Construction of the National Stadium of Beijing for the 2008 Olympics.” Journal of Urban Affairs 30 (2): 175–190. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9906.2008.00386.x.

- Sakai, Naoki. 2010. “From Area Studies toward Transnational studies.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 11 (2): 265–274.

- Schneider, Florian. 2019. Staging China: The Politics of Mass Spectacle. Leiden: Leiden University Press.

- Shougang. n.d. “Shougang Park.” Shougang. Accessed November 20, 2022. https://www.shougang.com.cn/en/ehtml/ShougangPark/.

- Shue, Vivienne. 2010. “Legitimacy Crisis in China?” In State and Society in 21st Century China, edited by Peter H. Gries and Stanley Rosen, 24–49. London: Routledge.

- Steinfeld, Edward Saul. 2010. Playing our Game: Why China’s Rise Doesn’t Threaten the West. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Takeuchi, Yoshimi. 2005. “Asia as Method.” In What Is Modernity? Writings of Takeuchi Yoshimi, edited by Richard F. Calichman, 149–166. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Tu, Wei Ming. 2005. “Cultural China: The Periphery as the Center.” Daedalus 134 (4): 145–167. https://doi.org/10.1162/001152605774431545.

- Walker, Gavin, and Naoki Sakai. 2019. “Guest Editors’ Introduction: The End of Area.” Positions 27 (1): 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1215/10679847-7251793.