ABSTRACT

Possibly no other media event has given rise to the widespread ridiculing of domestic violence as the livestreaming of Johnny Depp’s defamation action against his former wife Amber Heard. This article analyses the social media commentary surrounding a Tik Tok released by the Milani cosmetic company, which used the attacks on Heard as an advertising opportunity. The paper contextualises Milani’s intervention in the case within the wider social media commentary targeting Heard’s makeup and appearance and maps its aftermath in the emergence of a cross-platform hashtag #BruiseKit that generated a series of viral posts and videos featuring young women painting fake bruises on their faces. It concludes that the largescale diffusion of reactionary gender ideologies evidenced in the media data was partly shaped by commercial interests and platform incentives, but not—for the most part—driven by formal political actors. Rather, misogyny was commodified. It was produced and consumed as a form of entertainment.

Misogyny is rarely deemed to be acceptable. And yet, as Kate Manne (Citation2017) argues, it thrives—and is normalised—precisely because of this capacity to characterise itself as marginal, by passing itself off as bizarre and aberrant, or presenting itself as a joke. Manne’s analysis of misogyny’s socio-linguistic alibi aptly describes the logic of the media commentary that accompanied the livestreaming of Hollywood actor Johnny Depp’s legal action against his former wife, Amber Heard. Although critical and even feminist voices could be heard in the media mix, the dominant public descriptions of the toxic user-generated content that circulated on social media platforms such as TikTok, YouTube, Twitch, Twitter, and Instagram, functioned to de-gender and therefore de-politicise the phenomenon. In the mainstream media, user-generated content was trivialised as “ridiculous” and “funny” (eg. James Weir Citation2022), marginalised as “bizarre” (eg. Meredith Clark Citation2022a), pathologized as “sick” (eg. Dani di Placido Citation2022), “deranged” and “unhinged” (eg. Amelia Tait Citation2022), or cast outside credulity altogether, positioned as an “unreal story” (eg. Nick Wallis Citation2023) that allegedly did not correspond to any social or material reality at all. Although a handful of journalists applied a gendered lens to the case—for example, Moira Moria Donnegan (Citation2022), writing in the Guardian, labelled it a “public orgy of misogyny” – progressive critics more often framed the public shaming of Amber Heard within a narrative about the twilight of feminism, as “#MeToo backlash,” “#MeToo fatigue” or the “Death of #MeToo” (eg. Spencer Bokat-Lindell Citation2022).

This article analyses the social media narrative surrounding the Milani cosmetic company’s intervention in the trial, specifically the release of a TikTok on the company’s official account that labelled Heard a liar. It contextualises the brand’s intervention against a wider social media conversation about Heard’s makeup and appearance, then maps its aftermath in a minor hashtag #BruiseKit that generated a series of viral videos featuring young women using makeup to paint fake bruises on their faces.

Following Tanya Serisier (Citation2018), it argues that the highly publicised success of high profile cases that have marked the #MeToo era—such as the cases against Bill Crosby, Harvey Weinstein, Bill O’Reilly, and E Jean Carroll’s action against Donald Trump—have largely functioned via a logic of exceptionalism. This obscures the historically persistent patterns of doubt and disbelief that, as Leigh Gilmore (Citation2017) argues, work to selectively produce women as “tainted witnesses.” The article situates the social media commentary on the Depp case within these culturally and historically produced modes of judging women, which it argues have been incentivised, monetised, and given new affordances by social media platforms. Focussing on a “small stories” (Alexandra Georgakopoulou Citation2016) dataset of just over 113k tweets, the article identifies that much online activity derived from social media accounts that were broadly entertainment focused and did not map easily onto political positions. And yet, a closer reading suggests that this is not the same as a flattening, thinning out, or elimination of politics. Rather, misogyny was commodified—that is, produced and consumed as a form of entertainment.

Background

On June 1 2022, the District Court of Fairfax County, Virginia, in the United States, announced a verdict in the Depp defamation case against Amber Heard, reaching an opposite conclusion to the 2020 verdict handed down in a trial by judge alone in the United Kingdom (High Court of Justice/UK Citation2020). In the UK case, Depp had taken action against the Sun newspaper and its publishers over a 2018 article entitled “Gone Potty: How can JK Rowling be ‘genuinely happy’ casting wife-beater Johnny Depp in the new Fantastic Beasts film?” (Dan Wootton Citation2018). The article referenced a restraining order that Heard had taken out against Depp in a Los Angeles court in 2016, after Heard claimed Depp had assaulted her, throwing a mobile phone at her, and hitting her cheek and eye “with extreme force” (Nicky Woolf Citation2016). The UK judge found in favour of the Sun, accepting that the evidence before the court established the allegation that Depp was a “wife-beater” – that is, a perpetrator of domestic abuse—to be “substantially true.” But, in the US case, the jury reached a different conclusion.

In the Fairfax County action, Depp’s claim centred on a 2018 article published in the Washington Post entitled, “I spoke up against sexual violence—and faced our culture’s wrath. That has to change” (Amber Heard Citation2018). The article was written by Heard in conjunction with the American Civil Liberties Union, which had arranged the publication in Heard’s capacity as their women’s rights ambassador. This time, Depp sued Heard directly, without naming the Washington Post or the American Civil Liberties Union in his statement of claim. Although the Washington Post article had not named Depp, the jury accepted that he had been identified by implication. They also accepted Depp’s argument that Heard had acted with “actual malice,” placing her beyond the usual free speech protections enshrined in US law. They found Heard liable on three counts of making statements that Depp claimed were false and defamatory, including:

Count 1

I spoke up against sexual violence—and faced our culture’s wrath. That has to change.

Count 2

Then two years ago, I became a public figure representing domestic abuse, and I felt the full force of our culture’s wrath for women who speak out.

And,

Count 3

I had the rare vantage point of seeing, in real time, how institutions protect men accused of abuse (Editor’s Note in Heard Citation2018).

The jury awarded Depp $15 million, including $5 million in punitive damages that had to be reduced to $350,000, in accordance with Virginia state’s statutory cap. In a seemingly contradictory finding, the jury also awarded Heard $2 million in a cross suit against Depp’s lawyer, Adam Waldman. Waldman had alleged that Heard and her friends had roughed up Depp’s apartment as part of a sex abuse “hoax.” Beyond these three seemingly contradictory legal findings—that is, the UK finding against Depp, and the US verdicts against both Heard and Waldman—the judge’s decision to livestream a trial that centred on claims of gender-based violence has been the subject of criticism.

Televised court hearings are not unusual in the United States. Historically, some of the most widely watched US trials have centred on claims of gender-based violence, including, for example, the Ted Bundy and OJ Simpson trials, and the so called “New Bedford” or “Big Dan’s gang rape case” (Paul Thaler Citation1994), which continues to be characterised in the media via a misogynistic trope that dehumanises and erases the victim (a woman was raped, not a city or a building). What sets Depp v Heard apart—even by US standards—is that the trial was livestreamed on the internet in the age of social media, making it the first largescale celebrity trial of the streaming age. Digital broadcast network Court TV applied for, and was granted, rights to film the trial, with the presiding judge finding that the statutory protections usually extended to victims of sexual offences under Virginia state law do not apply in civil cases. The judge also overruled objections relating to the sensitivity of domestic violence, saying, “I don’t see any good cause not to do [livestream] it” (Gene Maddeus Citation2022). The resulting order allowed every US network the right to screen as much of the Court TV coverage as they wished, using a media pool system (Depp v Heard Citation2022). The YouTube channel of Court TV’s competitor the Law and Crime Network swiftly became the most popular venue for the coverage, reaching a peak audience of 3.5 million concurrent viewers on the day of the verdict, with an estimated 65% of this audience located outside the United States (Law and Crime Network Citation2022c).

The use of cameras dramatically expands visibility and audibility beyond that which is normally available to a person seated in the public or media gallery of most physical courtrooms (Camilla Nelson Citation2023). Moreover, unlike the kind of vision that is shot with a court’s own camera—which tends to offer limited, stationary angles with low production values—the Depp case was shot using multiple high-quality digital broadcast cameras, facilitating a diversity of angles and perspectives, including close ups. This not only afforded medium close-up shots of witnesses giving testimony, and lawyers arguing, but also—significantly—reaction shots from other trial participants, dramatically heightening the news values (Tony Harcup and Deirdre O’Neill Citation2017) of conflict and drama. This diversity of camera angles and perspectives facilitates a very different kind of court watching, including the close monitoring of facial expressions, such as Depp smirking, and Heard crying. The ubiquity of individual reaction shots, coupled with wider angled courtroom shots, also made fleeting, background or peripheral moments highly visible, such as Depp’s lawyer stealing the actor’s sweets, or the judge’s visibly affronted face in reaction to the doorman’s testimony, which was delivered via Zoom, vaping in his car, before driving off.

On the internet, the availability of free, high quality trial vision afforded—and in this sense encouraged—media audiences to scrutinise every square centimetre of the courtroom, with a kind of conspiratorial zeal. Otherwise innocuous looks, gestures and asides were transformed into mysterious clues, which, as the analysis in the later sections of this article points out, were subsequently investigated by teams of amateur online sleuths. Misinformation flourished. Depp’s lawyer Camille Vasquez was quickly cast as Depp’s romantic interest, with animated discussions across a variety of social media platforms commenting on her allegedly intimate interactions with her client (Peony Hirwani Citation2022). Social media users falsely alleged that Heard had copied quotes from The Talented Mr. Ripley in her testimony (Dan Evon Citation2022), and that she had been snorting cocaine while testifying on the witness stand (Nur Ibrahim Citation2022). Heard’s attorney—the target of much online vitriol—was also conspiratorially constructed as an undercover Depp fan (Hannah Sparks Citation2022), based on a blurry videoclip of the crowd from the 2013 London premiere of Depp’s Lone Ranger film.

The material that circulated on the internet to sustain and allegedly “evidence” these stories, included screenshots of the courtroom, intercut with media and fan-based ephemera, often marked up with a digital tool, or cropped and enlarged. Courtroom images were remixed and reposted on Twitter, Snapchat, and Instagram. Video clips were spliced together, paired with comedic soundtracks and clickbait headlines such as “Johnny Depp’s Lawyer Destroys Amber Heard,” “[Johnny] Lost his F*** Finger,” or “LIAR! Amber Heard Testimony is WORST performance EVER” (Popcorned Planet Citation2022). On Twitch and YouTube, dedicated groups of content makers provided live trial commentary, with open chat boxes featuring real time viewer comments, to which the content creator occasionally responded (Tom Murray Citation2022).

As Manne (Citation2017) points out, although the language of misogyny draws on socially, culturally, and historically established tropes and repertoires, it is rarely directed against all women but invariably targets one woman in particular who is seen to be defying accepted norms. Misogyny, in this sense, is always personal. So too, the social media commentary around the Depp case was grounded in deeply personal insults about Heard’s face, hair, clothes, make up and—quite specifically—her tears. Everything Heard said or did was meticulously dissected and produced as evidence of a lack of honesty. Heard’s claim to identify herself a survivor of domestic abuse was stereotypically attributed to her alleged greed and ambition, positioned as an attempt to enhance her celebrity. Heard was depicted as crazed and vengeful, or as a troubled woman with an undiagnosed mental health problem. By contrast, Depp was enveloped in what Manne calls “himpathy,” defined as the “inappropriate and disproportionate sympathy powerful men often enjoy” (Manne, Citation2017, p.265–6). Depp’s acts of violence that were alleged in evidence—including a documented threat to “rape [Amber’s] burnt corpse” – were minimised or cast as witty and charming.

Against this background, a plethora of social media users focused on Heard’s makeup, igniting a stream of commentary around a topic which, as Buzzfeed put it, “the internet has really fixated on” (Ikran Dahir Citation2022). The following sections of this article present an ethnographic analysis of this smaller conversation that was staged within larger media narrative of the trial, supercharged by a TikTok published on the official account of the Milani makeup corporation.

Research design and methodology

This article investigates how gender is constructed through a highly mediated court event, focusing on the interactions between a mediatising justice system (Jane Johnston Citation2018) and a hyper-mediatised public (Mark Deuze Citation2014; Jesper Stromback Citation2008; Frank Esser and Jesper Strömbäck Citation2014). It notes the media footprint generated by the Depp case includes over 18 billion #JusticeForJohnnyDepp views on TikTok, over 83.9 million streaming hours watched on YouTube, more than 17 million Twitter posts, and over 12,000 mainstream media news stories, in addition to podcasts, blog posts and articles in niche, magazine-style, and trade publications (David Sillito Citation2022; Jonathan Cohen Citation2022). This article takes a “small stories” (Georgakopoulou Citation2016) and “thick data” (Guillaume Latzko-Toth, Claudine Bonneau and Millette Mlanie Citation2016) approach to this enormous dataset, focusing on a selected Twitter corpus that is small enough to be analysed using qualitative rather than computational methods, aiming at depth rather than breadth.

Tweets in the corpus were collected from the Twitter Application Programming Interface (API), using Python based software TWARC2. I applied for, and received, academic research status from Twitter Corporation. The API allows researchers to run queries related to search terms (such as a word, phrase or hashtag) over a designated time period. I set the time period to start from the first day of trial (ie. April 11 2022), and the end seven days after the trial concluded on June 1 2022 (ie. June 8 2022), to capture the social media conversation that occurred in the aftermath of the verdict. The search string used was limited to tweets associated with the celebrity identifying codes specifically allocated by Twitter Corporation for “Johnny Depp” and “Amber Heard.” Within this pool, I generated a search string that included the brand name “Milani” as well as the words “makeup,” “make up,” or “bruise” to capture the contextual exchanges that were associated with this part of the social media conversation. This generated a sample of 113, 374 tweets.

The API provides a snapshot of user activity driven by relevance rather than completeness. This means that the API may not give access to all tweets but allows the researcher to construct a dataset that is far more reliable and substantial that anything that might be retrieved using Twitter Advanced Search, or via Tweetdeck. Data returned by the API included the text and time of the tweet, the screen names of senders, the numbers of “Likes,” “Replies,” “Retweets” and “Mentions,” as well as media attachments or urls embedded in the tweet. The media that circulated within the tweets (including, gifs, pictures, videos and links to professional/commercial media outlets) were analysed.

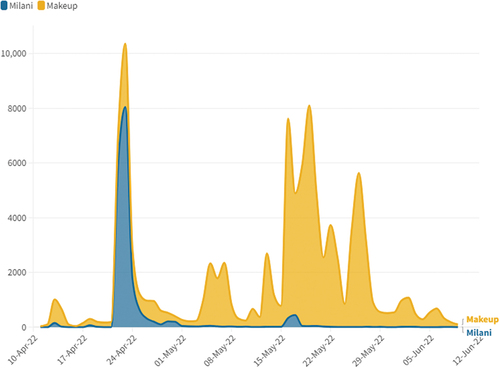

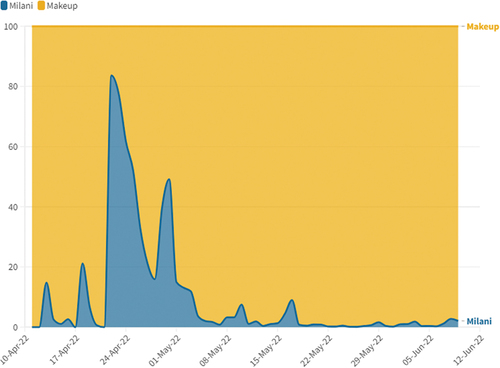

and provide a visualisation of this Twitter dataset across the timeframe of the trial. separates the conversation around the Milani brand from the wider conversation around make-up and bruises. shows the conversation around Milani as a proportion of the total conversation around Heard’s makeup. These quantitative diagrams allowed me to visualise patterns in the conversation over time, and to assess the impact of the Milani cosmetic company’s intervention, which appeared to act as a catalyst in social media exchanges.

Figure 1. Tweets associated with Amber Heard’s makeup across the time of the trial.

Figure 2. Tweets using the Milani brand name as a proportion of the total tweets focused on amber Heard’s makeup across the time of the trial.

In the second phase of the analysis, I initially read through the tweets focusing on measures of engagement, and the circulation of other media (ie. mainstream/commercial media and cross platform social media content) within the Twitter streams. By reading the original tweets I was able to analyse the use of language, images/gifs, the inclusion of urls/links to other media, observe how users presented themselves in Twitter profiles and handles, as well as how well networked they were, according to the number of followers and affiliations demonstrated by their use of hashtags, and the mentions they used and/or received. Based on these observations, I separated the online narrative into three overlapping phases/strands. The first phase of the conversation focused on Amber Heard’s makeup, the second phase focused on what users called the “Milani evidence,” and the third phase coalesced in a minor hashtag #BruiseKit, which proliferated more widely on TikTok.

In addition, because many tweets targeted specific media outlets and news stories, contextual media data was obtained via a systematic media search using Factiva, set to an identical timeframe as the API search. The search string “Amber Heard and Milani,” produced 81 news stories in which the brand name was specifically mentioned once duplicates were removed. As the content of Factiva is limited by commercial and contractual arrangements, an additional 28 magazine stories were identified via images and urls included in the API data, obtained via Google search, and manually added to the media corpus.

Lastly, in accordance with university ethics protocols, I have only specified Twitter handles and usernames in the case of verified accounts that identify a professional role associated with the account (eg. journalists, media organisations, brands), or verified users operating monetised influencer accounts. I have applied this ethical framework to the dataset irrespective of whether the users have been named in mainstream media stories. Any analysis that refers to gender or cultural identity relates to the user’s self-identification and self-presentation to their social media community.

Observations and analysis

Phase 1 – Amber Heard’s Makeup

In her opening statement, Heard’s lawyer informed the court that Heard had used colour correcting makeup to hide her bruises in the aftermath of the alleged domestic violence incidents set out in Heard’s response to Depp’s statement of claim. “Well, let me show you this … ” said Elaine Bredehoft, displaying a makeup palette to the jury. “This was what she used. She became very adept at it. You’re going to hear the testimony from Amber about how she had to mix the different colours for the different days of the bruises as they developed in the different colouring … ” (Law and Crime Network Citation2022b). On Twitter, networked actors immediately began conducting their own real-time investigations of the evidence as it is put before the court. Within hours, web-sleuths had named Milani as the manufacturer of the makeup palette. They also broke the news that the makeup’s 2017 release date did not coincide with the 2012–16 timeline of Heard and Depp’s relationship.

Perhaps the first to make this connection was a European fan-based account carrying popular culture and video gaming content, which had previously targeted high-profile feminists associated with the UK case. This probable ground-zero tweet included a tightly cropped screenshot of Bredehoft showing the makeup palette to the jury, another closeup of the palette, and a 2017 Milani advertisement launching a new “All in One Correcting Kit.” The three tight-cropped photographs endowed the tweet with a forensic aura, mimicking the investigative mode and aesthetics of “digilante” true crime forums (see, for example, Frauke Reichl Citation2019; Benjamin Loveluck Citation2020). Only in this tweet, the forensically styled images are anarchically juxtaposed with a text drawing an analogy between the Milani makeup palette and a retro-look Smeg-brand fridge that has “travelled back in time.” In combination with the images, the Smeg reference communicates an idea of expensive designer fakery. It is also probable that—for this online community—the specific choice of kitchen appliance refers to the misogynistic comic book trope known as “fridging” (or “women in refrigerators”), a hackneyed story device through which a male superhero character discovers his inner-strength after his girlfriend has died a gruesome death inside a refrigerator. The tweet was not accompanied by any hashtag but attracted over 1.1k engagements (retweets, quote tweets, likes and bookmarks) from followers. From there, the Twitter story grew in fits and starts, attaching itself to a range of high circulating hashtags, including #JusticeforJohnnyDepp and #AmberHeardisaLiar with the “time travel” motif—and a screenshot of a red Smeg fridge—appearing in a range of posts. Read within its social context, the image of the red Smeg fridge constitutes a threat (see broader discussion of multimodal social semiotics in Theo van Leeuwen Citation2005; Gunther Kress and Theo Van Leeuwen Citation2001).

This first phase of the Twitter conversation was largely associated with male-identified fan-based accounts, but quickly spread to other areas of the internet. This expanded Twitter conversation soon became dominated by female-identified users, mostly drawing attention to the inadequacy of concealer to coverup a bruise. Users continued in web-sleuthing mode, often circulating fashion shoots and red carpet photographs of Heard as alleged “evidence” of their claims. In these tweets, photographs were often methodically sequenced by date, or meticulously marked up with digital drawing tools (red circles or arrows), so that the aesthetic of the closeup photograph was semantically equated with veracity. Alleged “forensic” findings were usually flagged in an accompanying text, for example, “no evidence of any facial bruising,” “no racoon eyes” and “no marks whatsoever.”

Overwhelmingly, posts were shaped by a discursive construction of domestic violence that has long been rejected by experts as a myth (e.g. Evan Stark Citation2007; Rosemary Hunter Citation2006), including the idea that “real” domestic abuse entails physical violence (as one user put it, “black eyes, busted lips, broken nose”), and victim-survivors are obliged to produce proof of physical injury before they can be believed (“why no broken vessels in the eyeball … ?” or “a broken nose swells, black eyes swell, injuries like these SWELL”). Tweets in this category overwhelmingly focussed on the absence of visible physical injuries in celebrity or red carpet photographs as alleged “evidence” of their claims. Some alleged the attached photographs demonstrated that the actor was too glamourous to be a “real” victim. Others drew on the cultural trope of the femme fatale to suggest that glamour and attractiveness made the actor “even more dangerous.” Conversely, a significant number of tweets featured unflattering photographs (eg. a commercial shoot in which a possible pimple or rash was visible), suggesting the pictures provided “evidence” that Heard had fabricated the abuse allegations because she couldn’t use colour correcting makeup to camouflage a skin condition.

Unlike the earlier male-identified phase of the Twitter conversation, this largely female-identified discussion was shaped by a system of “selective belief,” in which binary cultural categories of “real” and “pretend” victims operate “counter-intuitively,” so that the recognition given to one kind of victim is used to cast doubt on the claims of another victim (Serisier Citation2018, 202; see also Gilmore Citation2017). As one user put it in a tweet directed “@washingtonpost,” not all of “us” are Johnny Depp fans “some of us are victims who don’t like when people make up stories to profit themselves while extorting real victims.” This binary construct of “real” and “pretend” victims of domestic abuse gradually became a structuring principle of the social media conversation, as it moved away from male-identified and fan-based accounts and into the mainstream.

Phase 2 – the “Milani evidence”

Nine days after Bredehoft presented her opening statement to the court, the male-identified stan account that had first named Milani announced—“LOL” – the makeup company behind the colour correcting palette had confirmed the findings of his online investigation. On April 22, Milani released a TikTok from its official account that effectively labelled Amber Heard a liar. “You asked us … ,” Milani posted. “Let the record show that our Correcting Kit launched in 2017!” (Milani Cosmetics Corporation Citation2022). The video—which reached 5.7 million views and 1,219,400 engagements on TikTok—mimics the epistemic modality of web-sleuthing which was the dominant linguistic style in the social media conversation, also sharing the ironic/anarchic address that marked the early fan-based conversation. The video starts with a text overlay—“What” – followed by a dynamic arrow pointing playfully at video-footage of Heard on the witness stand, as if she were an avatar in a computer game rather than a human being. The video then cuts to a torso shot of a female office worker walking down a corridor, presumably at Milani HQ, before entering an office where she investigates some computer files. “Take note,” reads the text overlay. “Alleged abuse was around 2014–2016, got divorced 2016, makeup palette release date: December 2017.”

The Milani TikTok engages sexist tropes on several levels. Firstly, the logic of digital detection works to reinforce the idea that victims of gender-based violence are untrustworthy and require investigation. Secondly, by setting the online investigation to the soundtrack of “International Superspy” (a theme-song drawn from Nickelodeon’s computer-animated children’s television series the Backyardians), the TikTok equates women with children, and abuse claims to childish pranks. In short, it trivialises abuse claims, infantilises victims, and holds survivors up to ridicule. To underscore this meaning, the text accompanying the video ends with a goggle-eye emoji, followed—in the comment boxes—by a string of cry-laughing emojis ending with the startling claim that Milani’s intervention in the legal action is neutral and impartial, concluding, “We are here to provide the facts … .”

As seen in and , the Milani TikTok supercharged the second phase of the social media conversation. Fan-based accounts are still conspicuous in the Twitter data, with several long investigative threads boasting a visual breakdown of “the Milani evidence” constructed out of digital ephemera (makeup advertisements, magazine clippings, photographs). But the Milani TikTok effectively pulled the makeup conversation out of the margins and into the mainstream. The corporate TikTok was played at full length on Court TV and the Law and Crime Network, garnering over 100 newspaper and magazine stories, spreading along highly trafficked commercial media networks. Buzzfeed even reported that “a public relations representative for Depp” had been sending the TikTok to journalists (Dahir Citation2022). The Milani brand name dominated this phase of the online discussion, with users expressing strong brand identification, declaring, for example, “I am now a loyal customer of MILANI,” and—in reference to Heard’s continued engagement by rival brand L’Oréal—“@LOrealParisUSA, take note” or “In a world of L’Oréal’s, be a Milani.”

Strong brand identification soon gave way to a more generic discussion around Heard’s makeup and appearance. But the linguistic residue of the Milani TikTok remained palpable in interactions in which the gender stereotypic cultural connotations of makeup, fabrication, acting and lying, were connected to Heard’s testimony. Although Twitter posts occasionally appeared which were highly critical of the way that the makeup corporation had ridiculed an alleged victim of domestic violence to build its brand (asking, for example, “Who the hell is running Milani’s socials … ?” or characterising the Milani post as “shameful”), nuanced gender-informed criticisms were scarce. Even highly critical social media posts tended to degender and therefore depoliticise the Milani TikTok by marking it as aberrant, variously characterising it as “weird,” “crazy as –,” “surreal,” and, in reference to the Netflix science fiction series, “psychotic Black Mirror sh*t.”

At the height of social media’s preoccupation with the Milani brand, tweets exchanging links to mainstream media stories about the “Milani evidence” regularly reached over 10k engagements each. Stories circulating widely in this phase of the Twitter conversation included Radar online’s “Makeup Brand Debunks Amber Heard’s Claim That She Used Their Product To Cover Bruises From Johnny Depp” (Whittney Vasquez Citation2022), Okay magazine’s “Milani Cosmetics Claps Back After Amber Heard Claimed She Used The Product To Cover & Touch Up Bruises From Johnny Depp” (Okay magazine Citation2022) and the Daily Mail’s “Makeup brand accuses Amber Heard’s lawyer of lying in court amid Johnny Depp’s $100 million defamation case” (Lillian Gissen Citation2022). Each of these stories legitimised Milani’s intervention in the legal action as a measure required to protect the company’s commercial integrity, using terminology such as “debunking,” “refuting,” “clapping back” or “firing back” to suggest the company was merely defending itself against an alleged prior attack by Heard.

In escalating cycles of amplification, both Court TV and the Law and Crime Network used the Milani TikTok to bookend Heard’s direct examination on trial day 16. Court TV claimed the Milani issue was “blowing up on social media” (T. V Court Citation2022), while the Law and Crime Network reported the internet was going “wild with this.” It even brought in a legal expert to affirm “this is a huge point” and “an unforced error,” reducing Heard to a “patchwork defence.” The expert raised the spectre that Heard was attempting to gaslight the legal profession, in the hope “we would never figure it out. We would never catch on” (Law and Crime Network Citation2022a). The intensity of the coverage convinced at least one TikTok user to travel to the Virginia courthouse to give the “Milani evidence” to Depp’s legal team. “Johnny Depp fan praised for attempt to hand-deliver Milani Cosmetics ‘evidence’ in Amber Heard case,” ran a hands-off headline (Meredith Clark Citation2022b). It is only towards the end of the article that the journalist reveals that this “praise” had come from social media followers.

Conversely, Twitter users took issue with critical and even neutral media stories, labelling them “gaslighting” and “fake news.” For example, when Newsweek (Ryan Smith Citation2022) ran a “fact check” finding that the Milani brand name had not been mentioned in the trial transcript, but merely displayed as a generic prop, users labelled the media outlet “manipulative.” Pro-Heard media coverage was pilloried on Twitter, with complaints serially directed to news outlets—for example, “@nytimes It’s called #gaslighting” or “@washingtonpost, @nytimes, @msnbc” followed by “trusted credible news source is less credible than a celebrity gossip outlet #TMZ.” Jezebel was prominent among the media outlets called out, with one opinion piece (Caitlin Cruz Citation2022), attracting oppositional tweets such as “@Jezebel No,” “@Jezebel Amber Heard lied” and “@Jezebel I mean come on, these people are nasty rich.”

Online identities are far from authentic or guaranteed, and Sentinel Bot (Citation2022) estimates that at least ten percent of the Twitter conversation was generated by bots. However, although much—or indeed most—of the Twitter conversation is startlingly regressive, only a tiny handful of accounts presented with overtly conservative or “alt-right” connections. A tiny handful of user profiles self-identified as “white” (suggesting racist allegiances), or carried overtly abusive tweets from the manosphere, such as, “PSYCO BITCH … CUMS TO HOLLYWOOD.” A larger number made frequent use of MAGA-style terminology, such as “truth,” “sanity,” and “fake news.” But political readings were not always obvious. More often, the Twitter data contained confusing and uncomfortable juxtapositions of sex, race, and class. For example, otherwise toxic accounts sometimes self-presented as queer-allies or pro-choice on abortion. Other tweets demanded to be read intersectionally. For example, Twitter users self-identifying as Latina, Afro-Caribbean or Afro American, frequently defined themselves as “real victims” in opposition to the “dishonest behaviour” of “#whitewomen” like Heard. Or else declared that Heard should be punished because the “only thing more dangerous than a white man in America is a crying white [woman].” Economic class was also a feature of the data, with tweets slamming Heard as “nasty rich,” or carping at the idea of a multi-millionaire purchasing mall-brand concealer, tweeting “the idea of her living this rich life and getting Milani make-up is hilarious.”

In this sense, the social media data can usefully be read in the context of Alice E Marwick’s (Citation2021) theory of “morally motivated” networked harassment. As Marwick points out, networked audiences with very different moral standards and values are frequently present in a single networked conversation and these amorphous networked groups frequently justify largescale abuse directed at a target by constructing their cause as somehow “morally right”. Marwick’s “morally right” common cause was overwhelmingly built through users’ selective belief in “real” as opposed to “pretend” domestic violence victims, in a binary structure that positions “real victims” as in need of protection from “pretend victims”. Such tweets typically alleged Heard was “such a disgrace to real fckn victims” and that women “who truly are victims will suffer bc of her”. Or else alleged the toxic dynamics of the social media conversation had “nothing to do with how women support the me too movement!?” or “the only reason woman [sic] rights are pushed back is because of woman [sic] like Amber Heard”.

Phase 3 – #BruiseKit

In the third—overlapping—phase of the social media conversation, discussion shifted away from corporate and mainstream media coverage, to cluster around a number of monetised influencer accounts, with significant segments of the audience gravitating towards LawTube, a neologism used to designate a plethora of YouTube accounts run by influencers who self-identify as lawyers. Emily D Baker—self-described as the “internet’s go-to entertainment legal analyst” – ran the fastest growing of these accounts, rising from 200k subscribers at the start of trial, to 731k on the day the verdict was announced. The channel has cross platform distribution via Twitter, TikTok, and Instagram, with a new podcast The Emily Show launched off the back of Baker’s trial coverage, currently ranked in the Top 5 for news and entertainment, with 18 million downloads to date (Emily D Baker Citation2023). Baker’s makeup videos, including “Did Milani Cosmetics Destroy Amber Heard’s Defense? Lawyer Reacts!” (Emily D Baker Citation2022a) and “Lawyer Reacts! … Trial Day 16” (Emily D Baker Citation2022b) reached more than 1.5 million and 924k views, with over 6k and 2k YouTube comments, respectively. Baker’s verdict video clocked up more than 2.3 million views (Emily D Baker Citation2022c). The segment of the Twitter audience drawn to this type of account tended to possess—or, at least, value—an encyclopaedic knowledge of the case, placing a premium on their expertise and authority, as one user tweeted, for example, if “you don’t know” about “amica cream, Milani, a mega pint, the muffins” then “you shouldn’t be commenting, just saying.”

Baker’s livestreamed trial commentary was delivered via a greenscreen profile set against courtroom video relayed from the camera pool. “No, no, no, not the makeup palette,” she called, midway through Heard’s direct examination. And again, “No, no, no, no, no, no … it’s happening. It’s happening. Now!” (Baker Citation2022b). The commentary was accompanied by occasional tweets to her followers, “The Milani Makeup Pallet is on the stand with Amber Heard … ” In the sidebar, subscriber comments appear in real time. They include so called Super Chat messages in which subscribers reveal they paid as much as $10 to have their comment feature more prominently on the screen. Occasionally Baker reads a comment, or uses it as a discussion prompt, such as “Why did her testimony sound like a makeup tutorial?.”

LegalBytes, a YouTube channel run by self-identified lawyer Alyte Mazeika, with over 250k subscribers, also featured prominently in the social media conversation. Mazeika’s commentary on “Trial Day 16” – the day Bredehoft asked Heard to explain her makeup routine to the court—gained more than 1 million views (LegalBytes Citation2022). Discussion among Mazeika’s subscribers ranged from the uses of concealer to cover up a bruise to the uses of makeup to generate a fake bruise. “Like, oh, oh no, you’re making a joke that she used a bruise kit to make the bruise not cover the bruise?” Mazeika responded. “Because she did say bruise kit” (LegalBytes Citation2022). This focus on bruises, concealer, and makeup routines, soon grew into a viral social media moment, driven by self-described makeup artists, fashion stylists, and their audiences, posting links, and responding to each other with one-liners. “A bruise kit is to make bruises. NOT … cover bruises” or “It’s a #BruiseKit, not a bruise kit!” or “#AmberHeard let it slip she used a #BruiseKit admitted it on stand!”

Parodies soon appeared, with Twitter users sharing tips on “how to actively use AH bruise kit,” with photographic illustrations. The largest user engagement in the dataset came from shared TikTok videos. On TikTok the hashtag #BruiseKit went viral, with scores of videos parodying Heard’s testimony by restaging it as a makeup tutorial, in which makeup was being used to paint on bruises, rather than conceal them. Many were set to the soundtrack of Heard’s testimony, with some reaching up to 12 million views. These videos are clearly entertainment-oriented, featuring a high concentration of humorous memes and meme-like activities. On Twitter and TikTok, replies to shared content mostly took the form of endorsements, although critical—and alarmed—reactions also formed a small part of the dataset. For example, “Women are doing their make up … using soundclips … of johnny depp calling [Heard] a whore … I’m actually speechless” and “there are literally videos of Johnny acting like a psycho … y’all white bychhes [sic] are going to hell.” The data suggests that this wide diffusion of reactionary gender ideologies was not driven by formal political actors. Rather, the dominant expression is in this phase of the conversation is the cry-laughing emoji, and the exclamation “LOL.”

Conclusion: commodifying misogyny

Misogyny, Manne (Citation2017) argues, is like the “law enforcement arm” of a patriarchal social order. It targets and punishes highly visible women who are not playing their patriarchally approved role. It does this to enforce the gender norms that keep women in their patriarchally approved place. The social media targeting Amber Heard’s make up originated in fan-based accounts, including a handful of male-identified accounts that had previously attacked high-profile feminists associated with the earlier UK trial. But as the conversation broadened, it began to centre on accounts with a much wider entertainment focus, often with less overt, and sometimes uncomfortable or conflicting socio-cultural and political allegiances. Most of these accounts were female identified. At this stage of the conversation, selective patterns of doubt and disbelief began to appear in the data. Specifically, binary categories of “real” and “fake” victims of domestic abuse materialised in the data, structuring the conversation so that Heard’s claim to be a “victim” was positioned as an attempt to undermine the rights of “real victims.” Analysis of the data revealed that this largescale diffusion of reactionary gender ideologies was not—for the most part—driven by formal political actors. Indeed, the high concentration of memes and meme-like activities across all stages of the social media conversation rendered political allegiances unclear. And yet, a close reading of the data suggests this was not the same as a thinning out or flattening of politics. Rather, a structural analysis of the digital media sphere suggests misogyny was commodified—that is, it began to circulate as a tradeable commodity in a digital marketplace in which emotions such as horror and outrage could be harnessed and converted into cash.

In this respect, it is important to contextualise the data by recognising the ways in which money flows through mediated relationships. In the broader media sphere, corporations extracted profits. Court TV quadrupled its audience (PR Newswire Citation2022). The Law and Crime Network saw a fiftyfold increase in its internet reach, with an estimated one billion visitors to its site across the trial period (Law and Network Citation2022c). Ben Shapiro’s right-wing news platform the Daily Wire reportedly spent tens of thousands on “anti-Amber” social media advertising, attempting to lure disaffected “pro-Johnny” social media users (Aja Romano Citation2022). Starbucks opened rival “Johnny” and “Amber” tip jars, as a marketing gimmick. German supermarket chain Lidl released an Amber Heard parody advertisement (Reena Gupta Citation2022). The online marketplace Redbubble floated a range of trial merchandising, including “Don’t be an Amber” and “Team Johnny” t-shirts, as well as “mega-pint” and “muffin” stickers. Coffee mugs featuring the “Amber Turd” and “Me Poo” hashtags were offered for sale at online outlets from AliExpress to niche handcrafted goods specialist Etsy (Anya Zoledziowski Citation2022).

Likewise, scores of monetised social media accounts jumped on board, prompting Taylor Lorenz (Citation2022), writing in the Washington Post, to declare content creators the “real winners” of the trial. According to analytics firm Social Blade, Emily D Baker’s YouTube channel was earning up to $109k per month at the height of the trial (Blade Social Citation2022b), a calculation based on a projection of advertising revenue, relying on YouTube’s complex formula that includes fluctuating payment variables, such as viewer dropout rates and penalties for swearing. Blade Social (Citation2022c, Citation2022a) similarly estimated that Mazeika’s LegalBytes earned up to $5,000 in a single week and YouTube identity DUIGuy—who, at one stage, made a supporting appearance on LegalBytes—was earning in a similar category. Revenue is also earned for views and subscriptions on TikTok and Instagram, not to mention YouTube’s Super Chat feature, with Business Insider suggesting that Baker was once again the top earner in this category (Tanya Chan and Geoff Weiss Citation2022; Geoff Weiss Citation2022).

The reality was that pro-Depp content was a lot more popular—gaining more Likes, Views, and Shares—than pro-Heard content. Hence, as profits accumulated in the digital economy, platform incentives helped shape public opinion. On social media, creator-driven coverage acted as a catalyst that effectively legitimised misogyny by commodifying pro-Depp content on a massive scale. Images of domestic and sexual abuse taken from Heard’s trial testimony circulated as comedy and entertainment, and digital platform incentives acted as a central driver for this new normal.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Camilla Nelson

Camilla Nelson is Associate Professor in Media at the University of Notre Dame Australia and an EG Whitlam Research Fellow at the Whitlam Institute within Western Sydney University. She is interested in voice and representation and how this shapes outcomes for people. A former journalist, Camilla has a Walkley Award for her work at the Sydney Morning Herald. She writes regularly for The Conversation and provides commentary for a wide range of media outlets, including ABC television and radio. Her most recent books include Dangerous Ideas About Mothers, and Broken: Children, Parents and Family Courts. Her current research focuses on the mediatisation of justice systems.

References

- Baker, Emily D. 2022a. ”Did Milani Cosmetics Destroy Amber Heard’s Defense? Lawyer Reacts!.” YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HAP8b2S9GWA.

- Baker, Emily D. 2022b. “Lawyer Reacts! Johnny Depp V. Amber Heard Trial Direct Examination Day 16.” YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M6xG3KzZh-8&t=15103s.

- Baker, Emily D. 2022c. “Lawyer Reacts! Live verdict in the Johnny Depp V. Amber Heard Trial.” YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hRcwlmTY9cY.

- Baker, Emily D. 2023. “Emily D Baker: The Internet’s Go-To Legal Analyst.” https://emilydbaker.com/.

- Bokat-Lindell, Spencer. 2022. “Is the #metoo Movement Dying?.”New York Times. June 9.

- Bot, Sentinel. 2022. “Targeted Trolling and Trend Manipulation: How Organized Attacks on Amber Heard and Other Women Thrive on Twitter.” Last Modified. July 18. https://botsentinel.com/reports/documents/amber-heard/report-07-18-2022.pdf.

- Chan, Tanya, and Geoff Weiss. 2022. “Depp V. Heard Trial: How Much Money YouTubers Made.” Business Insider. June 13. https://www.businessinsider.com/how-much-top-law-youtubers-made-during-depp-heard-trial-2022-6.

- Clark, Meredith. 2022a. “The Bizarre Parasocial Fans of the Johnny Depp V Amber Heard Trial.” The Independent. May 30. https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/johnny-depp-fans-amber-heard-trial-reddit-b2090316.html.

- Clark, Meredith. 2022b. “Johnny Depp Fan Praised for Attempt to Hand-Deliver Milani Cosmetics ‘Evidence’ in Amber Heard Case.” Independent. April 26. https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/amber-heard-johnny-depp-trial-milani-b2065010.html.

- Cohen, Jonathan. 2022. “Social Media’s Verdict on the Johnny Depp/Amber Heard Trial.” Last Modified June 9. https://www.listenfirstmedia.com/blog-social-medias-verdict-on-the-johnny-depp-amber-heard-trial/.

- Court, T. V. 2022. “Makeup Brand Debunks Amber Heard’s Claim.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yJD5ybK42R8.

- Cruz, Caitlin. 2022. “A Makeup Brand is Trying to Profit off of the Johnny Depp/Amber Heard Case.” Jezebel. April 22. https://jezebel.com/a-makeup-brand-is-trying-to-profit-off-of-the-johnny-de-1848829985.

- Dahir, Ikran. 2022. “All Rise, the TikTok Courtroom of Amber Heard and Johnny Depp is Now in Session.” Buzzfeed. April 29. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/ikrd/milani-cosmetics-tiktok-about-johnny-depp-and-amber-heard.

- Depp v Heard. 2022. CL-2019-2911. Order dated March 29.

- Deuze, Mark. 2014. Media Life. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Donnegan, Moria. 2022. “The Amber Heard-Johnny Depp Trial Was an Orgy of Misogyny.” The Guardian. June 2. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/jun/01/amber-heard-johnny-depp-trial-metoo-backlash.

- Esser, Frank, and Jesper Strömbäck. 2014. Mediatization of Politics: Understanding the Transformation of Western Democracies. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Evon, Dan. 2022. “Fact Check: Did Amber Heard Steal ‘Talented Mr. Ripley’ Lines During Depp Trial?.”Snopes. May 5. https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/amber-heard-johnny-depp-trial/.

- Georgakopoulou, Alexandra. 2016. “Small Stories Research: A Narrative Paradigm for the Analysis of Social Media.” In The SAGE Handbook of Social Media Research Methods. edited by Luke Sloan and Anabel Quan-Haase, 266. United Kingdom: SAGE Publications, Limited.

- Gilmore, Leigh. 2017. Tainted Witness: Why We Doubt What Women Say About Their Lives. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Gissen, Lillian. 2022. “Makeup Brand Accuses Amber Heard’s Lawyer of Lying in Court Amid Johnny Depp’s $100 Million Defamation Case – Revealing Concealer Kit Her Legal Team Claimed She Used to Cover Bruises from Alleged Abuse Wasn’t Sold Until AFTER They Split.” Daily Mail. April 23. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-10744393/Makeup-brand-says-concealer-Amber-Heard-used-cover-bruises-Johnny-Depp-abuse-DIDNT-EXIST.html.

- Gupta, Reena. 2022. “Here are the Companies That Participated in Amber Heard’s Global Humiliation.” Junkee. August 18. https://junkee.com/companies-heard-humiliation/338988.

- Harcup, Tony, and Deirdre O’Neill. 2017. “What is News?: News Values Revisited (Again.” Journalism Studies (London, England) 18 (12): 1470–1488. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2016.1150193.

- Heard, Amber. 2018. “I Spoke Up Against Sexual Violence — and Faced Our Culture’s Wrath. That Has to Change.” The Washington Post. 18 December. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/ive-seen-how-institutions-protect-men-accused-of-abuse-heres-what-we-can-do/2018/12/18/71fd876a-02ed-11e9-b5df-5d3874f1ac36_story.html.

- High Court of Justice/UK. 2020. “Depp v News Group Newspapers Ltd [2020] EWHC 2911.”

- Hirwani, Peony. 2022. “It’s sexist’: Johnny Depp’s Lawyer Camille Vasquez Shuts Down Dating Rumours with Actor.” The Independent. 10 June. https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/news/johnny-depp-camille-vasquez-dating-rumours-b2098022.html.

- Hunter, Rosemary. 2006. “Narratives of Domestic Violence.” The Sydney Law Review 28 (4): 733–776.

- Ibrahim, Nur. 2022. “Fact Check: Does Video Show Amber Heard Sniffing Cocaine at Depp V. Heard Trial?.” Snopes. May 10. https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/amber-heard-sniff-cocaine-trial/.

- Johnston, Jane. 2018. “Three Phases of courts’ Publicity: Reconfiguring Bentham’s Open Justice in the Twenty-First Century.” International Journal of Law in Context 14 (4): 525–538. doi:10.1017/S1744552318000228.

- Kress, Gunther, and Theo Van Leeuwen. 2001. Multimodal Discourse: The Modes and Media of Contemporary Communication. London: Arnold.

- Latzko-Toth, Guillaume, Claudine Bonneau, and Millette Mlanie. 2016. “Small Data, Thick Data: Thickening Strategies for Trace-Based Social Media Research.” In The Sage Handbook of Social Media Research Methods. edited by Luke Sloan and Anabel Quan-Haase, 199–214. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Inc.

- Law, and Crime Network. 2022a. “Did Amber Heard Actually Use Milani Makeup to Hide Bruises?.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZBlaMypLlp8.

- Law, and Crime Network. 2022b. “Johnny Depp V Amber Heard Defamation Trial-Opening Statement – Amber Heard’s Attorney.” 1 May 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-CyOiHTzsYY&t=2273s.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-CyOiHTzsYY&t=2273s.

- Law, and Crime Network. 2022c. “Law and Crime Network Hits Record 330 Million Viewers on Depp V. Heard Coverage.” Law and Crime Network. May 2. https://lawandcrime.com/live-trials/live-trials-current/depp-v-heard/lawcrime-network-hits-record-330-million-viewers-on-depp-v-heard-coverage/.

- LegalBytes. 2022. Johnny Depp V. Amber Heard, TRIAL DAY 16. Cross Exam Of Amber Heard!. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gsr4uFRYrXw.

- Lorenz, Taylor. 2022. “Who Won the Depp-Heard Trial? Content Creators That Went All-In.” Washinton Post, June 2.

- Loveluck, Benjamin. 2020. “The Many Shades of Digital Vigilantism. A Typology of Online Self-Justice.” Global Crime 21 (3–4): 213–241. doi:10.1080/17440572.2019.1614444.

- Maddeus, Gene. 2022. “Why Was Depp-Heard Trial Televised? Critics Call It ‘Single Worst Decision’ for Sexual Violence Victims.” Variety. May 27. https://variety.com/2022/film/news/johnny-depp-amber-heard-cameras-courtroom-penney-azcarate-1235280060/.

- Manne, Kate. 2017. Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny. Oxford University Press.

- Marwick, Alice E. 2021. “Morally Motivated Networked Harassment as Normative Reinforcement.” Social Media + Society 7 (2): 205630512110213. doi:10.1177/20563051211021378.

- Milani Cosmetics Corporation. 2022. “You Asked Us … Let the Record Show That Our Correcting Kit Launched in 2017.” Tik Tok. https://www.tiktok.com/@milanicosmetics/video/7089220965246356782.

- Murray, Tom. 2022. “Depp V Heard: How Courtroom Live-Streaming Turned an Ugly Battle Between Exes into a Circus.” The Independent. 6 May. https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/features/johnny-depp-amber-heard-trial-livestream-b2072870.html.

- Nelson, Camilla. 2023. “The ‘Most maligned’ Witness in the Christopher Dawson Case: Gender, Power, Media and Legal Culture in the Digitally Distributed Live-Streamed Court.” Crime, Media, Culture. doi:10.1177/17416590231168330.

- Okay magazine. 2022. “Milani Cosmetics Claps Back After Amber Heard Claimed She Used the Product to Cover & Touch Up Bruises from Johnny Depp.” April 22. https://okmagazine.com/p/milani-cosmetics-claps-back-amber-heard-bruises/.

- Placido, Dani di. 2022. “The Narcissism at the Heart of the Johnny Depp and Amber Heard Trial.” Forbes magazine. May 21. https://www.forbes.com/sites/danidiplacido/2022/05/21/johnny-depp-and-amber-heards-trial-has-stans-scrambling-to-control-the-narrative/.

- Planet, Popcorned. 2022. LIAR! Amber Heard Testimony is WORST Performance EVER. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Eanzg2c0R8A.

- PR Newswire. 2022. “Court TV Sets Network Viewership Record as More Than Half a Million Viewers Tune in for Depp Vs. Heard Verdict.” June 7. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/court-tv-sets-network-viewership-record-as-more-than-half-a-million-viewers-tune-in-for-depp-vs-heard-verdict-301563115.html.

- Reichl, Frauke. 2019. “From Vigilantism to Digilantism?” In Social Media Strategy in Policing: From Cultural Intelligence to Community Policing, edited by Akhgar, Babak Bayerl, Petra Saskia, Leventakis, George, Akhgar, Babak, Leventakis, George, and Bayerl, Petra Saskia, 117–138. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Romano, Aja. 2022. “Why the Depp-Heard Trial is so Much Worse Than You Realize.” Vox. May 20. https://www.vox.com/culture/23131538/johnny-depp-amber-heard-tiktok-snl-extremism.

- Serisier, Tanya. 2018. Speaking Out : Feminism, Rape and Narrative Politics. s.l: Springer international pu.

- Sillito, David. 2022. “Amber Heard and Johnny Depp’s Trial by TikTok’.” BBC Online. June 1. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-61649522.

- Smith, Ryan. 2022. “Fact Check: Did Amber Heard Lawyer Say She Used Specific Makeup on Bruises?”, April 27. https://www.newsweek.com/fact-check-amber-heard-lawyer-specific-makeup-bruises-johnny-depp-defamation-trial-1701478.

- Social, Blade. 2022a. “DUIGuy.” https://socialblade.com/youtube/channel/UC8CgVu25gujqkgXzoC7ueKA.

- Social, Blade. 2022b. “Emily D Baker.” https://socialblade.com/youtube/user/emilydbaker/monthly.

- Social, Blade. 2022c. “LegalBytes.” https://socialblade.com/youtube/c/legalbytesmedia.

- Sparks, Hannah. 2022. “TikTok Sleuths Think Amber Heard’s Lawyer is a Secret Johnny Depp Fan.” New York Post. April 27. https://nypost.com/2022/04/27/tiktok-thinks-amber-heard-lawyer-is-secret-johnny-depp-fan/.

- Stark, Evan. 2007. Coercive Control: The Entrapment of Women in Personal Life. Oxford University Press.

- Stromback, Jesper. 2008. “Four Phases of Mediatization: An Analysis of the Mediatization of Politics.” The International Journal of Press/politics 13 (3): 228–246. doi:10.1177/1940161208319097.

- Tait, Amelia. 2022. “Amber Heard V Johnny Depp Has Turned into Trial by TikTok – and We’re All the Worse for It.” 11 May. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/may/11/amber-heard-jonny-depp-trial-tiktok-fans.

- Thaler, Paul. 1994. The Watchful Eye: American Justice in the Age of the Television Trial. Westport, Conn: Praeger.

- van Leeuwen, Theo. 2005. Introducing Social Semiotics. London and New York: Routledge.

- Vasquez, Whittney. 2022. “Makeup Brand Debunks Amber Heard’s Claim That She Used Their Product to Cover Bruises from Johnny Depp.” Radar Online. April 22. https://radaronline.com/p/milani-cosmetics-amber-heard-bruises-johnny-depp-tik-tok/.

- Wallis, Nick. 2023. Depp V Heard: The Unreal Story. Bath, UK: Bath Publishing.

- Weir, James. 2022. “Johnny Depp, Amber Heard Trial: Ridiculous Reality Behind Court Circus.” News.Com.au. May 1. https://www.news.com.au/entertainment/celebrity-life/johnny-depp-amber-heard-trial-ridiculous-reality-behind-court-circus/news-story/610d918194f27be62c576207861abd3b.

- Weiss, Geoff. 2022. “YouTuber LegalBytes Sees Growth by Livestreaming Depp.” Business Insider. April 21. https://www.businessinsider.com/law-youtuber-legalbytes-streaming-johnny-depp-amber-heard-trial-2022-4.

- Woolf, Nicky. 2016. “Amber Heard Granted Restraining Order Against Husband Johnny Depp.” The Guardian. May 28. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2016/may/27/johnny-depp-restraining-order-amber-heard-divorce-domestic-violence.

- Wootton, Dan. 2018. “Gone Potty: How Can JK Rowling Be ‘Genuinely happy’ Casting Wife-Beater Johnny Depp in the New Fantastic Beasts Film?”. The Sun April 27. https://www.thesun.co.uk/tvandshowbiz/6159182/jk-rowling-genuinely-happy-johnny-depp-fantastic-beasts/.

- Zoledziowski, Anya. 2022. “People are Already Making Money off the Johnny Depp Trial.” Vice News. June 7. https://www.vice.com/en/article/5d3m3d/people-profiting-justice-for-johnny-depp-t-shirts.