ABSTRACT

Drawing on a digital ethnography of Istanbul Pride events in 2020 and in-depth interviews with LGBTI+ activists from Turkey, this study examines the transformations in the sites and practices of resistance during the COVID-19 pandemic. For the LGBTI+ community in Turkey, whose rights are already threatened by right-wing populist hegemony in politics, the pandemic brought further challenges and limitations to their public assemblies. While digital technologies afforded new sites for resistance, these spaces are not free from surveillance and inaccessibility, making their potential fragilities important to discuss. In this article, sexual citizenship is a central concept to analyse the resistance practices of the LGBTI+ community. By focusing on the affects and narratives of Pride participants, the article explores new opportunities and threats for the practices of LGBTI+ resistance caused by digitalisation. The analysis suggests that the assemblage of locations, technologies, and bodies primarily initiate novel forms of resistance. The LGBTI+ experiences show technological affordances make located experiences travel to a transnational digital, enabling affective interactions from afar, and that activists navigate their (in)visibilities via digital technologies to transform their resistance practices.

Introduction

In 2020, Istanbul Pride took place entirely online for the first time due to the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions across Turkey. The participants of the annual Pride celebrations came together on platforms such as Zoom, YouTube, Instagram, and a digital parade on an interactive Pride-focused website neredesinlubunya.com. The Istanbul Pride week was eventful, with 36 online panels, workshops, parties, and the traditional Hormonal Tomato Awards, which is given to most homophobic and transphobic public figures or organisations chosen by the LGBTI+ public of Turkey. The theme of this year’s Pride was Ben Neredeyim? (Where am I?) referring to the longing for embodied presence in public and reclaiming spaces of resistance through novel forms of activism.

This article is based on a digital ethnographic study focusing on the first-ever digital-only Pride events in 2020. I frame my study around these questions; how has pandemic digitalisation been reconfiguring the spaces of resistance for the LGBTI+ community? What is the role of affects and their circulations for practising sexual citizenship? I highlight the affective ontologies and the impacts of pandemic temporalities on the LGBTI+ resistance in Turkey. The empirical part of this study is based on my participation in digital solidarity gatherings, such as the Istanbul and Izmir Pride events in 2020 and semi-structured interviews with activists.

In Turkey, the LGBTI+ rights movement has already been challenged by the rising right-wing authoritarianism in the past decade. When the COVID-19 pandemic arrived, governmental restrictions on public gatherings intensified, reshaping socio-political life in response to the public health crisis. The increasing depoliticisation of public life made activists focus more on digital spaces for activism and socialisation. Some events included the digitalised Pride organised by grassroots committees in cities such as Istanbul, Izmir, and Mersin; as well as online gatherings, workshops, and parties hosted by LGBTI+ organisations and collectives. In addition, intensified digitalisation made new transnational connections possible, bringing together the LGBTI+ communities across borders.

Mass media surveillance and control are standard practices by the AKP (Justice and Development Party) government’s electoral authoritarianism in Turkey (Ozgun E Topak Citation2019). Therefore, social media platforms offer a significant space for the LGBTI+ community to produce alternatives against heteronormative moral knowledge regimes. A critical aspect is that digital technologies have also changed and altered governmental tactics for controlling populations. Despite their emancipatory potential, social media have become spaces of political polarisation and information distrust (Seva Gunitsky Citation2015). Whereas the recent political turmoil in Turkey has been deepening right-wing authoritarian hegemony, LGBTI+ activists in Turkey use digital platforms efficiently as part of their struggle (Yasemin Inceoğlu and Savas Çoban Citation2015). However, the feelings of anxiety and fear are also prominent due to the online surveillance regime dominated by the government. It is, therefore, crucial to challenge the linear account of LGBTI+ rights in Turkey from subjugation to liberation, as well as the dichotomised notions of freedom and control when analysing queer politics. Recognising subtle and everyday activisms entails going beyond conventional freedom/control dichotomies and exploring the possibilities for transformative politics. In so doing, I focus on affective solidarities formed beyond traditional online/offline or public/private divisions (Claire Hemmings Citation2012). For Hemmings, solidarity as a feminist practice emerges from the experience of affective dissonances against the hetero-patriarchal ordering of society (Hemmings Citation2012, 148). Mainly, I highlight the transformative role of digital technologies in facilitating such affective solidarities and, therefore, creating “affective counter-publics” (Sarah J Jackson, Moya Bailey and Brooke Foucault Welles Citation2020). Today’s (counter-)publics are digitally networked, with participatory practices enforced by digital affordances, changing how people engage and interact with their environments (Danah Boyd Citation2010). On that note, some scholars argued for an “affective public sphere” as today’s feminist and queer counter-publics are mobilised by sharing emotions such as rage, hope, and care through digital media (Yeran Kim Citation2010; Zizi Papacharissi Citation2015; Margreth Lünenborg Citation2019). In his work on pandemic experiences of LGBTI+ activism from Turkey, Tunay Altay (Citation2022) states that the AKP government had produced a pink line that blocks LGBTI+ visibility. He suggests that digital affordances help the LGBTI+ publics navigate their visibility more fluidly (p.71–72). Combating homophobic politics from the state has been important for the survival of the LGBTI+ in Turkey, especially for the trans community. In Queer in Translation (Citation2020), Savci highlights the importance of hopeless activism for trans resistance, where the AKP and previous governments have used the neoliberal Islamist or secular discourse to reproduce the state as an affective structure of hate against the LGBTI+ counter-publics. This does not mean the struggle against hate is the only motive for activism. Queer hope appears as a strong motive for resistance, not restricted to being a reaction towards heteronormative temporality, with queerness anticipating hope even at times of societal hopelessness (Jose Esteban Muñoz Citation2019; Yener Bayramoğlu Citation2021). Such hope is found in practices of queer(ing) time and space, which I discuss empirically in this article.

The political participation and resistance practices of the LGBTI+ community are central topics in studies of sexual citizenship. As a term first coined by David T Evans (Citation1993), “sexual citizenship” refers to the possibilities and limitations of sexual expressions when defining political participation. The prior analyses documented well how queer politics does not necessarily challenge normative citizenship as nationalistic, colonial, and capitalistic discourses reproduced a commitment to heterosexual marriage, binary gender regime and their reproductive roles (David Bell and Jon Binnie Citation2000; Diane Richardson Citation2017; Leticia Sabsay Citation2012). In this article, I use “sexual citizenship” to highlight the centrality of gender and sexuality in disciplining (non-)citizen subjects in Turkey. I consider “citizenship” a concept to define the subject’s role concerning the disciplinary state, to highlight this subject’s struggle to obtain rights that are not yet given, and to critique the legal definition of citizenship as an exclusionary status. Therefore, I recognise the notion of citizenship as a participatory practice beyond being a (un)given legal status of sexually and gender variant subjects. Such a perspective brings the question of the spatiality of resistance practice (or activism) to the forefront, considering the impacts of digital technologies in our socio-political lives. If the LGBTI+ community is a form of (counter-)public, understanding why and how specific communicative tools are used for affective solidarities is crucial for studying resistance practices. My focus is, therefore, drawn upon acts of citizenship (Engin F Isin Citation2008; Joe Turner Citation2016), which carry the transformative potential for the LGBTI+ lives that are presumably marginalised. There are associated limitations, however, to the usage of the concept of sexual citizenship. Putting citizenship at the centre of studying political subjectivity may result in a methodological nationalism which portrays the bordered nation-state as the sole or main unit in making of citizen-subjects (Andreas Wimmer and Nina Glick Schiller Citation2002). My epistemic focus on practices of citizenship aims to challenge such legalised and bordered understanding of citizenship as the sole category of the Turkish nation-state and think of how LGBTI+ resistance and futurity can imagine a (sexual) citizenship as transnational and solidaristic. Another possible critique is that the concept can lead LGBTI+ to be exclusionary for trans and gender-variant experiences. In this article, I frame sexual citizenship from a trans-feminist perspective, where the usage of the term acknowledges the centrality of situated trans experiences in defining the LGBTI+ resistance in Turkey.

The practice of sexual citizenship should also be investigated within the temporalities of the pandemic. It is important to explore how digitalisation during the pandemic reconfigured the spaces of resistance for the LGBTI+ community. Zeynep Tufekci (Citation2017) highlights that today, we talk of a “complex interaction of publics, online and offline, all intertwined, multiple, connected, and complex, but also transnational and global” (p.6). This applies to the LGBTI+ rights movement partially transformed by online and offline entanglements, where technological affordances have their agential power in (re)defining the forms of struggle. I consider refracted public a valuable concept to understand the networked resistance tactics by activists going beyond dualisms of private/public and individual/collective action. Crystal Abidin (Citation2021) introduced this concept to refer to online cultures taking advantage of visibility regimes (Boccia Artieri, Stefano Brilli Giovanni and Elisabetta Zurovac Citation2021), which produce survival strategies against the hegemony of surveillance and algorithmic systems. The refracted public is formed by encoded, subtle, yet effective communication between networked publics, which use online and offline spaces creatively and interchangeably. The refracted public is a reaction to the contested internet culture that derived from data leaks, new authoritarianism, retrogressive protests, and, most recently, the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, today’s networked sub-communities do not seek mass visibility but rather intended measures of (in)visibility, what Abidin calls silosociality (Abidin Citation2021, 4). The “silos” refer to covert online spaces serving the interest of the networked publics, with certain vernacular and sensibility (Katrin Tiidenberg, Natalie Ann Hendry and Crystal Abidin Citation2021). Such covert tactics of resistance are not new to the LGBTI+ community in Turkey but have existed, for instance, in the queer vernacular of lubunca (Ozban Citation2022) and online spaces (Serkan Görkemli Citation2012).

Politics of affect and queer assemblages

I focus on the transformations in the LGBTI+ resistance cultures of the daily practices rather than analysing emancipatory outcomes of contentious resistances. The focus, therefore, is that understanding resistance beyond its measure of success, and embrace acts of failure. For doing this, I adopt an affective epistemology that focuses on the affective dissonances of everyday activism, considering subtle and temporal interventions as transformative for resistance cultures (Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick Citation2003; Natalie Kouri-Towe Citation2015). In her book Touching Feeling, Sedgwick talks about “affective turn” to critique dichotomous perspectives as limiting in understanding how the agency functions in social movements (Sedgwick Citation2003, 12). Her epistemology focuses on encounters where the agency is driven by emotions and socialisation that are fundamental for LGBTI+ resistance (Kouri-Towe Citation2015). Hemmings (Citation2012) argues that “affective solidarity” emerges when negative emotions such as failure are experienced. Such experiences of anger or frustration against injustice cause affective dissonances that produce the necessary critical position and urge for action for social transformation (p.157). Sara Ahmed (Citation2004) also discussed the ontology of emotions as they move between bodies and objects. She grants emotions the power to intensify bodily positions, directing individuals or collectives towards new politicised engagements. Such an approach moves away from the essentialism of bodily experience and instead positions the body as a multi-layered, experiential, and culturally embedded entity (Kathy Davis Citation2013). Therefore, identifying the self depends not on essentialised and sexed bodies but on body-to-body interactions (not necessarily human), which Puar describes as assemblages (Jasbir Puar Citation2020). These are the bodies of (non-)humans, technology, institutions, places, etc. I explore how such interactions and affective dynamics work in the context of Turkey in the following sections of this article. Thus, I approach LGBTI+ resistance practices as “affective assemblages” (Jasbir Puar Citation2017; Charlotte Halmø Kroløkke Citation2014), which brings an epistemology of emotions and assemblage of bodies together. In line with such an approach, Çağatay Selin, Mia Liinason and Olga Sasunkevich (Citation2022) conceptualise resistance beyond the dichotomies between individual and collective, as well as visible and invisible practices. They argue that resistance is a multi-scalar experience transforming our thinking about togetherness and navigating between scales from local to transnational (p.69). My approach to LGBTI+ resistance is inspired by their discussions beyond predetermined dichotomies of political practices. Therefore, I offer an analysis of subtle experiences of resistance that do not limit themselves to contentious politics. The following section provides a genealogical reading of sexual citizenship in Turkey to situate the contemporary sexual rights struggle.

Framing sexual citizenship in the context of Turkey

The participatory measure for sexual citizenship is challenged by the right-wing conservative imposition of the AKP government in Turkey. Such politics have caused a widespread polarisation of social groups especially visible on social media (Özduzen and Korkut Citation2020). I call this fragmentation a participatory crisis, as Nira Yuval-Davis (Citation1997) feminist political analysis suggests, that citizenship can be used as an organising principle for the depoliticisation of populations. A long legacy of the constructions of normative citizenship in Turkey causes the limitations on sexual citizenship. The transition from the Ottoman Empire to the secular Turkish Republic redefined Turkish citizens as a subject-in-westernisation emphasising gender equality in legal terms (Yesim Arat Citation2010). Nevertheless, this was because of a familial construction of citizenship objectifying heterosexist reproduction as the main principle of Turkish modernity (Olgu Sirman Citation2013). Mia Liinason, Selin Çağatay and Olga Sasunkevich (Citation2023) analyse Turkish exceptionalism by highlighting the country’s bridging role between East and West. They argue that during the initial period of the conservative-Islamist AKP government, the national identity came to be characterised by tolerance. Nevertheless, a deepening exclusion of minority groups such as Kurdish citizens, asylum seekers and refugees from Syria, and the LGBTI+ communities has been visible (p.8). President Erdoğan’s electoral authoritarianism (Işık Yilmaz and Gulnur Bashirov Citation2018) furthered an authoritarian turn in Turkey towards a right-wing populist ideology after the Gezi Park Resistance in 2013 (Seyla Benhabib Citation2013). Erdoğan’s authoritarian longings to create pious and depoliticised generations are accompanied by a robust anti-gender discourse (Gökariksel et al. Citation2019), like other right-wing populist attacks on the LGBTI+ lives by the governments in Hungary, Poland, and Bulgaria. Erdoğan’s unconstitutional decision to withdraw from the Istanbul ConventionFootnote1 is the most concrete example of targeting feminist and LGBTI+ activists’ achievements. In April 2020, Ali Erbaş, the Director of Religious Affairs, called for a fight against the evil of homosexuality as “it brings illnesses and corrupts generations” during his Friday preaching focusing on the pandemic (Hilal Köylü Citation2020). Although the Turkish constitution does not criminalise LGBTI+ identities, the marginalisation of LGBTI+ citizens in Turkish society has been intensifying both in the forms of police interventions against public demonstrations and through the production of hate speech on conventional and social media channels.

Besides the disciplining of sexual citizenship, many scholars have discussed the long-lasting LGBTI+ resistance in Turkey with strong spatiality. The research includes different topics, such as the presence of LGBTI+ artists at the stages of art scenery (Eser Selen Citation2012), neighbourhood resistance by trans citizens against urban gentrification projects (Pınar Selek Citation2001; Aydın D Ünan Citation2015), occupation of Gezi Park in Istanbul as an LGBTI+ cruising spot (Cenk Özbay and Evren Savcı Citation2018; Ali E Erol Citation2018) online spaces as a platform for queer politicisation (Görkemli Citation2012; Ozgur Çalışkan Citation2021) and hashtag activism and networked resistance during Pride events in Istanbul (Onur Kilic Citation2023). Other studies also stated that resistance to moral geographies is a critical spatial dimension of LGBTI+ activism and that creating safe spaces is an urgent issue for the movement (Erol Citation2018; Özlem Atalay and Petra L Doan Citation2019). From these vantage points, my approach to sexual citizenship sees the LGBTI+ identities as subjects of assemblage between ongoing networks of bodies, technologies, and spaces. The LGBTI+ resistance, therefore, is to be found at the intersection of emotions, corporeality, and affordances, where queer politics is reassembled with online-offline entanglements.

Methodology

This study adopts a digital ethnographic perspective highlighting the online manifestations of the LGBTI+ community during Istanbul Pride in 2020. My study recognises multi-sites of ethnography, considering online presences and offline appearances as important analytical categories, as suggested by some feminist ethnographers (Angela Cora Garcia, Alecea I Standlee, Jennifer Bechkoff and Yan Cui Citation2009; Christine Hine Citation2017; Alessadro Caliandro Citation2018). The multi-sites of ethnography refer to thinking beyond national or rural–urban boundaries and online-offline divisions. Therefore, a digital ethnography can also be a multi-sited ethnography. Such thinking framed my study, as I did not limit the selection of the research participants through certain geographic boundaries, but instead, based it on a shared experience of participating in online Pride events and affiliation to the LGBTI+ rights struggle in Turkey. The online spaces I was part of themselves also involved different sites such as Zoom, YouTube, and Instagram, bringing Turkish-speaking queer bodies together from a variety of locations.

In the same way digital technologies can impact bodily presence, corporeality can also transform the affordances of digital spaces (Garcia et al. Citation2009; Hine Citation2017). On that note, I argue for the epistemological need to explore emergent resistance tactics by the LGBTI+ community, where technology is used in novel ways via hyperlinks, hashtag activisms, and cross-platform campaigns for their political participation. To grasp these novel and dynamic interactions, Caliandro (Citation2018) suggests reshaping ethnography as a flexible method for dynamic online environments (p.552). Taking the messiness of the digital as a precondition, he suggests following the online social formations based on an empirical object, such as a topic of discussion that connects different actors. As a significant digitalised event in pandemic times, Istanbul Pride provides an ideal case to understand the impacts of digitalisation on LGBTI+ political and social life. John Postill and Sarah Pink (Citation2012) equated this methodological choice by the ethnographer as a place-making practice. In this study, digital Pride events form this “ethnographic place” based on people’s constantly evolving and changing online/offline networking.

Motivated by the discussions above, this multi-sited ethnography combines (a) participant observations during chosen digital Pride events and (b) semi-structured interviews with LGBTI+ activists from Turkey.

For participant observation, I followed LGBTI+ digital activism on Twitter and Instagram since the beginning of the pandemic in February 2020. In June 2020, due to the pandemic immobility, I was not able to travel to Turkey. I followed the transformation to digital activism and observed that Istanbul and Izmir Pride Committees, with their long-term experience in queer organizing, were able to bring together many LGBTI+ individuals not only from their cities but from a variety of geographies. Similarly, to many other Turkish-speaking LGBTI+ individuals, I had the opportunity to participate in the Pride in the cities of Istanbul and Izmir in 2020 as highlight events in digitalised settings. My experience of Pride ethnography encapsulates the messy connections and networking of LGBTI+ individuals through multiple digital platforms such as Zoom, YouTube, Twitter, and Instagram. Furthermore, the symbolic importance of the event in connecting online publics with offline struggles illustrates how affective solidarities are formed and sustained.

I conducted in-depth interviews with chosen LGBTI+ activists from Turkey between late 2020 and early 2021. The participants were chosen for the study because they had experienced digital Pride yet had long pre-pandemic LGBTI+ activism experiences. I conducted interviews to explore offline experiences not provided by digital affordances and see different perspectives on digital activism within the community. While I chose my first participants from LGBTI+ individuals I interacted with before and during the digital Istanbul Pride, I used snowball sampling to expand the scope and diversity of the participants. The choice of participants reflects the diverse gender, sexuality, class, and ethnic identifications within the LGBTI+ community. In selecting interview participants, I was driven by my encounters before, during and after Istanbul Pride in 2020. I (re)contacted 8 LGBTI+ activists who had partaken in the digital Pride events to conduct semi-structured interviews and listened to their experiences of the pandemic restrictions and the genealogy of their activism.

I categorised the main interview questions under three themes: (1) identification and perceptions of spaces of LGBTI+ resistance, (2) the daily and/or political usage of digital platforms, and (3) perceived fragilities and challenges for identifying as LGBTI+ in Turkey.

A significant limitation of the interviews is that, due to pandemic conditions, the meetings took place on Zoom. Therefore, I reflect upon the lack of knowledge that could be caused by not being on the site physically. Under these circumstances, location is regarded as a digitalised and narratively formed experience. Nevertheless, as many of the activists I interviewed used the same location and platform (Zoom and their homes/rooms), the setting of the interviews reflected the perceived reality of digital Pride events. Therefore, I combine conventional methods such as interviews with digital media as a fieldwork environment to grasp what has happened in digital spaces and understand why people participate in specific online settings.

Analysis

In June 2020, my participant observation at the digital Istanbul Pride Week was a unique experience as the first fully digital Pride ever from Turkey. While sitting in my room in Gothenburg, Sweden, I could partake in more than 15 events. The participants were in various places in Turkey and countries such as Germany, Greece, Italy, Norway, the United States, Canada and others. Pride events have been particularly contested in Turkey since 2015 as the local governorates of the largest metropolises, Istanbul, Ankara, and Izmir, banned the event in these cities. Istanbul Pride, being the oldest and largest Pride event in the country with peaceful political demonstrations and cultural activities, had seen unlawful police interventions, resulting in the detentions and injuries of Pride participants. Social media is vital for documenting discrimination and showing solidarity for Turkey’s LGBTI+ community at local and transnational levels. While the streets of Istanbul were missing the rainbow flags and political slogans from the LGBTI+ community and allies, thousands of people gathered on platforms such as Zoom, YouTube, and Instagram to participate in more than 30 events organised by the Istanbul Pride Committee.

(Re)assembling sexual citizenship: affective solidarities at the digital

Listening to the LGBTI+ activists’ experiences revealed how the affective dissonances took place for them in forming solidarities. Their located resistance both before and during the pandemic provides hints of sexual citizenship as a practice. While participants of this study have long and diverse histories of LGBTI+ activism at individual and organisational levels, their participation in Istanbul Pride events served as their unifying experience. For all the participants of this study, Istanbul Pride has a fundamental role in raising emotions such as hope, love, anger, and compassion. They have varied involvement with Istanbul Pride, some being part of the organising committees in different years from the early 2010s. Due to their long history of activism, the participants could observe the authoritarian turn in Turkey targeting the LGBTI+ community and the spatial challenges resulting from the pandemic. While listening to activist trajectories, I identified oftentimes dichotomous views on the impacts of digital technologies in the LGBTI+ movement culture. Although the activists expressed dualisms between the embodied collectivity of offline spaces and the disembodied individuality of online ones, their lived resistance practices blurred such sharp divides. In this section of the analysis, I focus on the examples of networked resistance practices by the participants that challenge the perceived dichotomies of embodiment/disembodiment and individual/collective actions on digital platforms.

Eda (she/they) is one of those activists from Istanbul who had been an active member of the Istanbul Pride Committee for several years, including the banned Pride events of 2015 and 2016. Eda’s activist trajectory combines involvements groups such as the LGBTI+ student organisation in her university, a separatist LBT+ activist group, Istanbul Pride Committee, and a queer neighbourhood collective in Istanbul. In the earlier years of her activism, Eda focused on street activism to reclaim the public sphere. As Eda moved to Berlin, Germany, a year before the pandemic started, she felt an important aspect was missing from her activism. When I asked her what she was missing from her days in Istanbul, she replied,

I miss the streets; resistance and activism on the streets. I never want to deny how important and life-saving queer friendship is, these are the reasons why the chosen family and finding lovers have led me to progress in my own queer activism, but after a point, doing the street activism that I am longing for. (…) Here [in Berlin] I do not have the urge to go demos, it’s not the same survival and emotional urge I had in Turkey, which called me to the streets. (Eda)

The digital Istanbul Pride in June 2020 helped her feel reconnected to Turkey, including online queer parties and gatherings that took her back to times in Istanbul. However, her reconnection felt temporal and has been missing a corporeal aspect. She described that digital Pride was only half of the full experience;

Why half experience? We don’t really just come together and take off our bras and run to the stage to meet a friend from the crowd. Or, I don’t know, you can’t kiss at some point with someone you’ve given the glad eye at the beginning of the night. The togetherness of bodies I realised its importance during the pandemic. I don’t want to think binary about online and offline, but I think bodies have another potential when they come together. I can get offline at the digital level anytime … I can disappear … (Eda)

Eda expressed her nostalgia about street activism consolidated by a sense of fragility in digital spaces, equated with the lack of corporeal connection with other LGBTI+ individuals. For all activists I interviewed, friendship had been a necessary precondition for initiating their activism, where solidaristic friendships inspired other political organising. As Jose Esteban Muñoz (Citation2009) argues, queer nostalgia and loss relate to affective historicity in queer politics, where the movement draws its energy from achievements and failures of the past to designate its anticipation of queer future. In Turkey, the deepening authoritarian regime, and the constraints on the spaces of resistance increase the importance of affective histories that are vital to mobilise novel resistance practices.

Besides, digital technologies facilitate further networking beyond borders. During the pandemic, Instagram provided Eda with an alternative participation when an LGBTI+ student uprising started in Istanbul’s Boğaziçi University in early 2021. Eda shared this experience;

When the Boğaziçi protests emerged, I started following all the live streams on Instagram. Those live streams are elevating my emotional involvement so much. I had become brave enough to post a lot about those protests and feel involved, as I was feeling like I was there, knowing every detail of the protest (…), yet it (live stream) became a paradoxical experience by escalating my longing to be there (Eda)

Eda’s virtual participation in a street protest at Boğaziçi University in Istanbul caused mixed emotions of solidarity and longing to be there. This experience revived a virtual form of togetherness with her community due to the affective solidarity (Hemmings Citation2012) created by the protests. For Sedgwick (Citation2003), such performative action can change the personal and spatial status through the affective dissonance it stimulates. Eda’s encounter with the protest transformed her position in Berlin from a sense of disconnection to political action. Her feelings of rage and despair of being far away from the struggle are created by the very effect of interacting bodies and objects, as objects become “sticky” by passing emotions (Ahmed Citation2004). For Eda, the mobile device afforded her to witness state-induced violence during the protests, blurring the binaries between embodiment and disembodiment as she “was feeling like she is there” through her mobile device. The digital affordances provided that affective relationship for Eda to take further action by posting about the protests online and supporting the cause of the movement without being there physically, turning her ambivalent position of being far and close at the same time into a transformative action.

Deniz (they/them), a non-binary activist from Cyprus, moved to Istanbul in 2011 to find other LGBTI+ people like themselves. For Deniz, a Turkish-speaking Cypriot, Istanbul was the place to go, as LGBTI+ organising was not as vibrant in Nicosia back then. They were involved in organisational activism in Istanbul shortly before and during the Gezi Park Resistance 2013. Gezi Park Resistance provided Deniz the space for street activism. They describe those years as follows;

I felt more like an activist there. Because you are on the street, you are experiencing those events. You are fighting for something and exposed to that incoming tear gas. Whether you define yourself there or not, you become an activist. You are there because you are standing still and not running. Yes, you become an activist even without the need for description. But when I look now, I am looking for a field of struggle to continue being an activist myself. (Deniz)

While Deniz emphasised the primary role of street activism, their own practice combines online and offline by recording feminist and LGBTI+ rights protests and making reels/videos online. As an activist focusing on visual content creation, Deniz’s visible online presence was helpful as a strategy for coming out in various political and social settings;

Digital spaces helped me feel safer about my non-binary identity in different groups, whether online or offline. I am a leftist activist, and sometimes I join socialist political meetings. Whenever I went to those groups before, I had to come out repeatedly because sometimes I was misgendered and felt othered. After using my gender pronoun in digital spaces and the non-binary symbol in my account name on Instagram, I started feeling better and understood by my political and social circles. (Deniz)

Despite Deniz being misgendered through the binary construction of gender by the cis-normative social circles, the assemblage of digital and corporeal identity facilitated safer spaces for them. Deniz’s example shows how assemblages of online-offline appearances can (re)articulate LGBTI+ identities, helping activists tackle participatory challenges they may have based on intersectional identity positions.

I observed that participants’ ambivalent experiences regarding the impacts of digital spaces on their activism are related to the continuous divisions between online and offline spaces, embodied and disembodied actions, as well as oppression and liberation positions. For example, Idil (she/her), a transgender rights activist who was involved in organisational activism in Ankara and on social media for a long time, commented on online events:

[On Zoom] time is used more efficiently, and we see that the person shares what they want to talk about in a more organised manner and expresses themselves efficiently, which is good for participation. But not being able to have bodily contact, small talks during breaks, not being able to come together, not being able to do the thing that planted the seeds of that network, that is bad of course. (Idil)

However, Idil and other activists have been consciously transgressing this presumed divide by using platforms such as Zoom, YouTube and Instagram to organise solidarity gatherings, discussions, and LGBTI+ events and interact with new people from far away, which they had not been accustomed to before the pandemic. It is important to think of such novel resistance practices beyond pandemic temporality, where online engagements commonly merge and open space to corporeal togetherness in the long run. Therefore, the reimagining of sexual citizenship is possible through such transformative experiences based on activists’ affective solidarities. Puar (Citation2017) uses assemblage theory to deconstruct the primacy of identification as a precondition of queer politics and sees identification as a continuum. The identification process occurs when queer bodies encounter others. These bodies are not necessarily humanoid or organic, but also inorganic, locational, institutional, or technological. Therefore, Eda’s resistance could occur with the assemblage of protesting bodies, locations of struggle, and digital technologies, even when she is physically absent from the scene. The following part explores how discourses on freedom and control regimes influence participatory measures for LGBTI+ activists.

‘The digital’ as a contested space of resistance

For the LGBTI+ community in Turkey, social media has become a space of contestation rather than free expression. The surveillance regimes, algorithmic systems, and other impacts of dataisation continuously threaten LGBTI+ political participation. However, sexual citizenship is a practice that goes beyond the dichotomy of freedom and control. During interviews, all participants mentioned their recurrent fears about exposing their sexual orientation and gender identities online. For some, this fear led them to limit their political participation on social media, such as being hesitant about sharing their views, restricting or freezing their Twitter accounts, etc. Such actions are mainly affected by activists’ perception of social media as a space of control in authoritarian temporality. For instance, Hakan (he/him) is an activist from a small town in the Black Sea region with a conservative family background. He found out about the LGBTI+ community and came out after he moved to Istanbul for his higher education. He explained his first participation in Istanbul Pride in 2014 as life-changing, where later he became actively involved in the LGBTI+ organisations in Istanbul and hosted an event during Istanbul Pride in 2020. While he is an activist with certain visibility in the community, Hakan finds it difficult to expose his identity online, fearing traceability;

Every time, I think twice before sharing something. I am not that afraid of Instagram. I am so afraid of Twitter that I don’t even have an account there. Because even if you retweet something on Twitter, you can be detained. Once, a friend of mine shared an absurd tweet, shared a humorously ironical tweet, the police raided his house at night and took him to Ankara (Hakan)

In the above quote, Hakan shows that digital actions, direct or indirect, are not anonymous or separated from the ontology of the embodied self. As he cannot separate his physical or digital presence, his body carries the potential to be digitised as information. From an assemblage perspective, the traces of the body are found at the intersection of digital and physical, as the body does not end at the skin (Donna J Haraway Citation2023; Puar Citation2017). An important implication of such a perspective is that online and offline presences should be seen as the continuation of each other. Queer bodies become punishable whether they are or are not present in resistance in physical forms through detainment and imprisonment. Mert (he/him), an activist from Izmir involved in organisational activism for over a decade, explained why he does not have a Twitter account, although he believes Twitter is a crucial platform for LGBTI+ resistance.

I think we have a horrible tracking and policing of Twitter in Turkey. I do not know how some activists share content on Twitter without fear, especially when the content criticises the government. (Mert)

In this case, the discourses of control are a crucial part of digital technologies where traceability in producing statistical and marketable values becomes a source of fear. Such technologies are not only used as neoliberal tools, by the marketability of the subjects through algorithms but also as governmental tools for tracing with authoritarian agendas. For Ahmed (Citation2004), fear as an affect shrinks bodily presence and hampers the mobility of the fearing subject. Therefore, fear can travel through surveillance of bodies at online and offline spaces. In this regard, the participatory crisis for sexual citizens needs the consideration of bodies both as informational entities and physical beings.

Practicing sexual citizenship as a refracted public

In Istanbul Pride Citation2020, the digital-only feature of the event highly decreased the physical aspects of violence, whereas safety measures in online spaces still had to be taken. Cybersecurity had already been on the agenda of the Istanbul Pride Committee before the pandemic arrived, as homo/bi/transphobic attacks would happen occasionally. When I interviewed Burak (he/him), he was in the Istanbul Pride Committee for the preparations of the Pride in 2021, which also took place mostly on digital platforms. Burak has a background in digital communication design, and he has used his digital communication skills to contribute to Pride activism in Istanbul for several years since 2017. Drawing on his experience from different Pride committees, he explained his earlier work on cybersecurity measures as follows;

We [the Pride Committee] have been working on cybersecurity measures since 2017. We joined training programs and learned how to make our accounts more protected. However, as the committee changes every year and we are not a corporate entity, it is difficult to sustain the security measures in the long-term. (Burak)

Burak’s comment indicates that digital spaces are not an exception in political contestation. Yet, they are a site of struggle where technological affordances could be used for better safety. Burak also highlights the temporality of resistance, seeing the discontinuity as a problem in tackling surveillance regimes. As Tufekci (Citation2017) argues, authoritarian governments use oppression tactics such as producing an information glut, inducing confusion and distraction, and mobilising counter-movements (p.6). Turkish government uses a troll army (Ergin Bulut and Erdem Yörük Citation2017) to produce hate speech and misinformation about the LGBTI+ community through spamming and reposting manipulative hashtags on Twitter. Such threats to democratic participation in digital spaces have made activists navigate between online visibility and security, making invisibility a conscious choice of resistance (Çağatay, Liinason, and Sasunkevich Citation2022). Francesca Stella (Citation2015) emphasises that acts of resistance that are not overtly visible can be transformative, especially in contexts where sexual citizenship faces substantial heteronormative limitations. Such queer politics going beyond in/visibility dichotomy reframes sexual citizenship contentious politics and embraces the transformative covert actions. During our interview, Mert, involved in activism himself as early as 2008, shared his observations on activism;

In the past, it was like getting married to an LGBTI+ organisation, when you would do activism. It was a strong commitment. There is no need to make such big commitments now. I think it provides a context where you can come together quickly and disperse quickly. The downside to this could be; long-term institutional transformations may not be achieved. Or, I don’t know, it may cause the dissolution of an organisational culture. The resistance becomes a little more like hit-and-run, do you see what I mean? It has advantages and disadvantages. (Mert)

During Istanbul Pride in 2020, Zoom was the main platform, used for eight of the fifteen events I participated in. As earlier registration and a collective agreement for safe space at the beginning of each session was necessary, the atmosphere felt more controllable yet participatory. Another notable action was having a team responsible for technical issues and cybersecurity during the events. The help of the technical team and the affordances of Zoom made muting, banning, or privately messaging participants possible, making the space more definable. In such ways, Istanbul Pride in 2020 provided an alternative site of collective presence after the extensive amount of oppression that had challenged the safety of the LGBTI+ community in previous years.

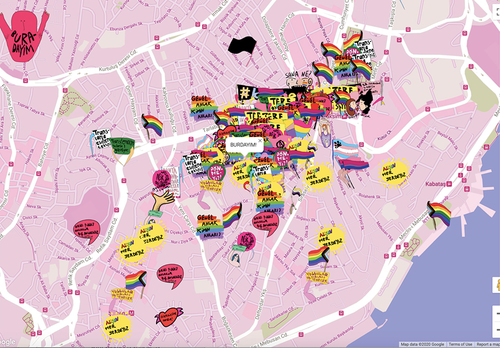

While online events were not new for many, the study participants found one resistance practice especially creative and novel: the digital Pride Parade. For this “surprise” event of Istanbul Pride Week, the organising committee prepared a website called Neredesin LubunyaFootnote2? (Where are you, Lubunya?). I got the news about this surprise during one of the Zoom sessions the day before the march and via the Instagram account of Istanbul Pride. Seven of the interviewees mentioned that they interacted with the digital parade website as well. The website neredesinlubunya.com included an interactive world map centring on Istanbul and its famous Istiklal Street, where Pride parades had traditionally taken place since 2003.Footnote3 On this map, people could mark themselves at their locations in Istanbul or worldwide, alongside a pin with different visuals. These pins represented banners they would hold during a Pride parade. They could also attach a personal message or a political slogan they would shout in a physical Pride parade to be shared on this website.

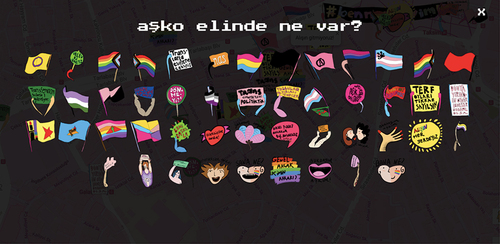

In , the pin designs represent sexuality and gender-diverse identifications, including bisexual, pansexual, transgender, and asexual flags and political slogans commonly used by the LGBTI+ community. Some examples from these slogans are “If morality is oppression and violence, we are immoral,” “We are everywhere, get used to it,” “The world will turn upside down if ibneler* (faggots) have freedom.” and “TERF (trans-exclusionary radical feminists) votes should be recounted!.” The visuals show how queer knowledge from an intersectional perspective has been produced with the assemblage of bodies (through the engagement of participants), technologies (neredesinlubunya.com website and the pins), and places (interactive digital map of Istanbul).

Figure 1. The pins that could be chosen to mark oneself on the map. The text above the pins says, “what are you holding, love?” (Istanbul Pride Citation2020a).

Neredesin Lubunya? project demonstrated the integrity of spatial resistance for the LGBTI+ community in Turkey, and showed the possibility of digitally amplified embodied action, even when the conventional spaces of resistance are inaccessible. As seen in above, the symbolic importance of Istiklal Street on the map created a sense of affective resonance in a space where the LGBTI+ community historically resists. Whereas the impossibility of Pride on the streets posed a severe threat to socialisation and politicisation at a time the LGBTI+ communities of Turkey needed it at the utmost level, Neredesin Lubunya? managed to bring people together beyond the in/visibility paradigm. This is a novel form of resistance where an assemblage of emotions, (digitised) bodies, and locations are formed to actualise a Pride march despite the pandemic restrictions. I see this as a form of silosociality, where a covert collective action creates a space protected from police violence by bringing LGBTI+ individuals together virtually. For Tiidenberg, Ann Hendry, and Abidin (Citation2021) such spaces “run a lesser risk of context collapse, making it a more pleasant, safe-feeling, creative-seeming, and justice-oriented social space for users” (p.60). The LGBTI+ “silos” (Abidin Citation2021) have their vernacular Lubunca, which is used on the pins and speech bubbles that the participants wrote during digital march.

Figure 2. Map of Beyoğlu district of Istanbul. The densely pinned area on the map is the surroundings of Istiklal Street, where Istanbul pride takes place annually (Istanbul Pride Citation2020b).

Conclusion

In this article, I explored the LGBTI+ resistance practices from Turkey to discuss sexual citizenship as an act rather than a stable(ized) identity position. My analysis of affective politics emphasised the primary role of emotions flowing between locations, technologies, and bodies in providing novel forms of resistance. I argue for the agential role of digital affordances in articulating sexual citizenship by providing alternative forms of political participation, such as joining a protest from afar or using new coming-out tactics. Through my participant observation at Istanbul Pride, I explored silosociality in digital spaces that increase the participatory potentials of sexual citizens. I argue that online presence does not only cause a blurring of safety/visibility boundaries but also provides flexibility to LGBTI+ “silos”. The LGBTI+ resistance finds this transformative potential in the “grey zone” between contentious and subtle activism, where we do not privilege mass visibility as the only measure for social change (Çağatay, Liinason, and Sasunkevich Citation2022). In this regard, Istanbul Pride used subtle forms of resistance as tactics to reach the intended audience. In the longer term, the disappearance of the LGBTI+ bodies from the spaces of resistance would deepen a participatory crisis, with decreased interventions in the heteronormative public sphere. The ambivalence and temporality in pandemic times have shown that social change could happen suddenly, transforming our everyday relationships so quickly that our presumptions on social and political interactions can easily be obsolete.

Acknowledgements

This article was written as part of the transdisciplinary research cluster TechnAct: Transformations of Struggle supported by the Swedish Research Council under reference number 2018-03869. I am very thankful for the precious contributions of my research participants and for sharing their time for this study. I also would like to send my thanks to the anonymous peer reviewers of this study and to my PhD supervisors, Mia Liinason and Marta Kolankiewicz, for their helpful feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Onur Kilic

Onur Kilic is a Ph.D. candidate at the Department of Gender Studies in Lund University. He is a researcher in the project TechnAct, a research cluster devoted to the interconnections between digital technologies and emergent feminist and queer communities in transnational space. Onur’s research interests include, among others; LGBTQI+ movement cultures in Turkey from a transnational perspective, online and offline entanglements in activism, queer theory, networked resistance practices, and qualitative research methods such as digital ethnography.

Notes

1. Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence (CETS No.210).

2. Lubunya or Lubun is a queer vernacular that originally refers to feminine gays, transvestites, and trans-women. Today, it is used as an umbrella term for LGBTI+ individuals.

3. First attempt for a Pride march was in 1993 in Beyoglu, which was resulted the police intervention. The first successful march took place in 2003, organised by LambdaIstanbul.

References

- Abidin, Crystal. 2021. “From ‘Networked publics’ to ‘Refracted publics’: A Companion Framework for Researching ‘Below the radar’ Studies.” Social Media+ Society 7 (1): 2056305120984458.

- Ahmed, Sara. 2004. “Affective economies.” Social Text 22 (2): 117–139.

- Altay, Tunay. 2022. “The Pink Line Across Digital Publics: Political Homophobia and the Queer Strategies of Everyday Life During COVID-19 in Turkey.” European Journal of Women’s Studies 29 (1_suppl): 60S–74S.

- Arat, Yesim. 2010. “Women’s Rights and Islam in Turkish Politics: The Civil Code Amendment.” The Middle East Journal 64 (2): 235–251.

- Artieri, Boccia, Stefano Brilli Giovanni, and Elisabetta Zurovac. 2021. “Below the Radar: Private Groups, Locked Platforms, and Ephemeral Content—Introduction to the Special Issue.” Social Media+ Society 7 (1): 2056305121988930.

- Atalay, Özlem, and Petra L. Doan. 2019. “Reading the LGBT Movement Through Its Spatiality in Istanbul, Turkey.” Geography Research Forum 39: 106–126.

- Bayramoğlu, Yener. 2021. “Remembering Hope: Mediated Queer Futurity and Counterpublics in Turkey’s Authoritarian Times.” New Perspectives on Turkey 64: 173–195.

- Bell, David, and Jon Binnie. 2000. The Sexual Citizen: Queer Politics and Beyond. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Benhabib, Seyla.2013. “Turkey’s Authoritarian Turn” The New York Times. Accessed December 20. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/04/opinion/turkeys-authoritarian-turn.html

- Boyd, Danah.2010. “Social network sites as networked publics: Affordances, dynamics, and implications.” In A networked self, edited by Zizi Papacharissi, 47–66. New York: Routledge.

- Bulut, Ergin, and Erdem Yörük. 2017. “Digital Populism: Trolls and Political Polarization of Twitter in Turkey.” International Journal of Communication 11: 25.

- Çağatay, Selin, Mia Liinason, and Olga Sasunkevich. 2022. Feminist and LGBTI+ Activism Across Russia, Scandinavia and Turkey. Springer Nature. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-84451-6.

- Caliandro, Alessadro. 2018. “Digital Methods for Ethnography: Analytical Concepts for Ethnographers Exploring Social Media Environments.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 47 (5): 551–578.

- Çalışkan, Ozgur. 2021. “Digital Pride on the Streets of the Internet: Facebook and Twitter Practices of the LGBTI Movement in Turkey.” Sexuality & Culture 25 (4): 1447–1468.

- Davis, Kathy. 2013. Reshaping the Female Body: The Dilemma of Cosmetic Surgery. New York: Routledge.

- Erol, Ali E. 2018. “Queer contestation of neoliberal and heteronormative moral geographies during #occupygezi.” Sexualities 21 (3): 428–445.

- Evans, David T. 1993. Sexual Citizenship: The Material Construction of Sexualities. London: Routledge.

- Garcia, Angela Cora, Alecea I Standlee, Jennifer Bechkoff, and Yan Cui. 2009. “Ethnographic Approaches to the Internet and Computer-Mediated Communication.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 38 (1): 52–84.

- Gökarıksel, Banu, Christoper Neubert, and Sara Smith. 2019. “Demographic Fever Dreams: Fragile Masculinity and Population Politics in the Rise of the Global Right.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 44 (3): 561–587.

- Görkemli, Serkan. 2012. “Coming Out of the Internet: Lesbian and Gay Activism and the Internet as a ‘Digital Closet’ in Turkey.” Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies 8 (3): 63–88.

- Gunitsky, Seva. 2015. “Corrupting the Cyber-Commons: Social Media as a Tool of Autocratic Stability.” Perspectives on Politics 13 (1): 42–54.

- Haraway, Donna J.2023. “A Cyborg Manifesto: An ironic dream of a common language for women in the integrated circuit.” In The Transgender Studies Reader Remix, edited by Susan Stryker and Dylan McCarthy Blackson, 429–443. New York: Routledge.

- Hemmings, Claire. 2012. “Affective Solidarity: Feminist Reflexivity and Political Transformation.” Feminist Theory 13 (2): 147–161.

- Hine, Christine.2017. “From virtual ethnography to the embedded, embodied, everyday internet.” In The Routledge companion to digital ethnography, edited by Larissa Hjorth, Heather Horst, Anne Galloway, and Genevieve Bell, 47–54. New York: Routledge.

- Isin, Engin F.2008. “Theorising Acts of Citizenship.” In Acts of citizenship, edited by E. F. Isin and G. M. Nielsen. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Jackson, Sarah J, Moya Bailey, and Brooke Foucault Welles. 2020. # HashtagActivism: Networks of Race and Gender Justice. London: Mit Press.

- Kilic, Onur.2023. “‘Every Parade of Ours is a Pride Parade’: Exploring LGBTI+ Digital Activism in Turkey.” Sexualities 26 (7): 731–747.

- Kim, Yeran. 2010. “The Affective Public Sphere.” Media & Society 18 (3): 146–191.

- Kouri-Towe, Natalie. 2015. “Textured Activism: Affect Theory and Transformational Politics in Transnational Queer Palestine-Solidarity Activism.” Atlantis: Critical Studies in Gender, Culture, and Social Justice 37 (1): 23–34.

- Köylü, Hilal. 2020. “Korona Günlerinde Diyanet’e ‘Nefret Suçu’ Tepkisi”. Deutsche Welle. https://www.dw.com/tr/korona-günlerinde-diyanete-nefret-suçu-tepkisi/a-53260541

- Kroløkke, Charlotte Halmø. 2014. “West is Best: Affective Assemblages and Spanish Oöcytes.” European Journal of Women’s Studies 21 (1): 57–71.

- Liinason Mia, Selin Çağatay, and Olga Sasunkevich. 2023. “Varieties of exceptionalism: A conversation.” In Transforming identities in Contemporary Europe, edited by Elisabeth L Engebretsen and Mia Liinason. New York: Routledge.

- Lünenborg, Margreth.2019. “Affective publics: Understanding the dynamic formation of public articulations beyond the public sphere.” In Public spheres of resonance, edited by Anne Fleig and Christian von Scheve, 29–48. New York: Routledge.

- Muñoz, Jose Esteban. 2009. “From Surface to Depth, between Psychoanalysis and Affect.” Women & Performance: a Journal of Feminist Theory 19 (2): 123–129.

- Muñoz, Jose Esteban.2019. Cruising Utopia. 10th Anniversary ed. New York: New York University Press.

- Ozban, Esra.2022. “New Channels in Digital Activism: Lubunya Digital Cultures in Turkey.” In LGBTQ Digital Cultures: A Global Perspective, edited by Paromita Pain, 130–143. New York: Routledge.

- Özbay, Cenk, and Evren Savcı. 2018. “Queering Commons in Turkey.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian & Gay Studies 24 (4): 516–521.

- Özduzen, Ozge, and Umut Korkut. 2020. “Enmeshing the Mundane and the Political: Twitter, LGBTI+ Outing and Macro-Political Polarisation in Turkey.” Contemporary Politics 26 (5): 493–511.

- Papacharissi, Zizi.2015. Affective Publics: Sentiment, Technology, and Politics. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Postill, John, and Sarah Pink. 2012. “Social Media Ethnography: The Digital Researcher in a Messy Web.” Media International Australia 145 (1): 123–134.

- Puar, Jasbir. 2017. Terrorist assemblages : Homonationalism in Queer Times. 10th anniversary expanded ed. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Puar, Jasbir.2020. “‘I would rather be a cyborg than a goddess’: Becoming-intersectional in assemblage theory.” In Feminist Theory Reader: Local and Global Perspectives, edited by Carole McCann, Seung-kyung Kim, and Emek Ergun, 405–415. New York: Routledge.

- Pride, Istanbul. 2020a.”neredesinlubunya.com”. Accessed July 2, 2020. http://neredesinlubunya.com

- Pride, Istanbul. 2020b.”neredesinlubunya.com”. Accessed July 2, 2020. http://neredesinlubunya.com/

- Richardson, Diane. 2017. “Rethinking Sexual Citizenship.” Sociology 51 (2): 208–224.

- Sabsay, Leticia. 2012. “The Emergence of the Other Sexual Citizen: Orientalism and the Modernisation of Sexuality.” Citizenship Studies 16 (5–6): 605–623.

- Savcı, Evren.2020. Queer in Translation: Sexual Politics Under Neoliberal Islam. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. 2003. Touching Feeling. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Selek, Pınar. 2001. Maskeler Süvariler Gacılar: Ülker Sokak: Bir Altkültürün Dişlanma Mekanı [Masks, Troopers, Women: Ülker Street a Place for the Social Exclusion of a Subculture]. Vol. 8. Istanbul: Ayizi.

- Selen, Eser. 2012. “The Stage: A Space for Queer Subjectification in Contemporary Turkey.” Gender, Place & Culture 19 (6): 730–749.

- Sirman, Olgu. 2013. “The Making of Familial Citizenship in Turkey.” In Citizenship in A Global World: European Questions and Turkish Experiences, edited by F. Keyman and A. Icduygu, 147–172. London: Routledge.

- Stella, Francesca. 2015. Lesbian Lives in Soviet and Post-Soviet Russia: Post/Socialism and Gendered Sexualities. London: Springer.

- Tiidenberg, Katrin, Natalie Ann Hendry, and Crystal Abidin. 2021. Tumblr. Cornwall: John Wiley & Sons.

- Topak, Ozgun E. 2019. “The Authoritarian Surveillant Assemblage: Authoritarian State Surveillance in Turkey.” Security Dialogue 50 (5): 454–472.

- Tufekci, Zeynep. 2017. Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Turner, Joe. 2016. “(En)gendering the Political: Citizenship from Marginal Spaces.” Citizenship Studies 20 (2): 141–155.

- Ünan, Aydın D. 2015. “Gezi Protests and the LGBT Rights Movement: A Relation in Motion.” In Creativity and Humour in Occupy Movements: Intellectual Disobedience in Turkey and Beyond, edited by Ayşe Yalcintas, 75–94. London: Palgrave Pivot.

- Wimmer, Andreas, and Nina Glick Schiller. 2002. “Methodological Nationalism and Beyond: Nation–State Building, Migration and the Social Sciences.” Global Networks 2 (4): 301–334.

- Yasemin, Inceoğlu and Savas Çoban. 2015. “Sokak ve Dijital Aktivizm: Eylemin Sokaktan Siber Uzaya Taşınması ya da Vice Versa.” In İnternet ve Sokak: Sosyal Medyada Dijital Aktivizm ve Eylem, edited by Yasemin Inceoğlu and Savas Çoban, 19–72. İstanbul: Ayrıntı.

- Yilmaz, Işık, and Gulnur Bashirov. 2018. “The AKP after 15 Years: Emergence of Erdoganism in Turkey.” Third World Quarterly 39 (9): 1812–1830.

- Yuval-Davis, Nira. 1997. “Women, Citizenship and Difference.” Feminist review 57 (1): 4–27.