ABSTRACT

In post-WWII United States, Maidenform’s “I dreamed I went shopping in my Maidenform bra” campaign (1949–1969) was seen as a prime example of the psychoanalytical sell: the ads seemed to tap into the repressed psyche of the 1950s housewife, directly pulling the levers of deep-seated sexual desires. This remarkable account has carried over into more recent analyses with little interrogation as to its soundness, and non-Freudian variants have equally re-iterated a “duped housewives” narrative. These accounts, however, tend miss out on the humor that characterized both the ads and the audience’s responses to them. The Dreams might have led to purchase, but they were also reimagined across popular culture in the form of plugs, puns, spoofs, jokes, pranks, parodies, fancy dress, and college floats. In this paper, I explore how Maidenform’s message migrated from the company’s control to a fixture in consumer culture. I argue that humor enabled audiences to mull over the implications of ads’ message and articulate the tensions and discomforts around the depiction of women’s bodies and mental aspirations. This study highlights how consumer responses can complicate dominant narratives in the history of advertising to women.

When Maidenform set its iconic “I dreamed I […] in my Maidenform bra” campaign (the “Dreams,” 1949–1969) in motion, it did so with a dose of cheek: the puns, as well as the overt references to the Freudian naked dream, invited audiences to take the ad in jest. Yet our understanding of the campaign does not acknowledge the role that humor has played in its longevity. Instead, the dominant explanation has relied on a psychoanalytic version of the questionable maxim that “sex sells:” women were buying more bras as a result of a cathartic (or neurotic) lever being pulled by her exposure to another woman’s wish-fulfilment (e.g., Vance Packard Citation1957). In an often-quoted 1963 article for Advertising Age, art director Stephen Baker purported that …

The sad, or happy truth is that any woman worth her sex is basically deep down a born exhibitionist. […] Maidenform dreams allow the eager females to take a brief but meaningful excursion into the wicked land of violent and base emotions, uninhibited men, and “bad” women.Footnote1

Baker may not have intended his comment to be taken in earnest, but his verdict echoes the records left behind by observers in the industry, which overshadowed other explanations and responses. In one swoop, these commentators acknowledged the existence of female sexuality whilst denying women their voices: women were not depicted as sentient and sensuous beings in control of their own dreams, but as the subjects of inner forces that could find their way to the surface if triggered from the outside. Much of the subsequent literature on Maidenform has failed to question this interpretation; one scholar, for example, writes that Maidenform “us[ed] images of sex and power (or the illusion of power) to sell directly to the fantasies, the presumed unconscious, of millions of American women” (Paul Rutherford Citation2007, 99). The ads have therefore been condemned by some as manifestations of the symbolic violence that sustained inequalities (Barbara J Coleman Citation1995) by glorifying domestic femininity (Nancy Patton Mills Citation2006), distracting women with escapist, unattainable fantasies (Wendy A Burns-Ardolino Citation2007; Stephanie Molholt Citation2008; Maire Orav Simington Citation2003), or reinforcing her self-identification as a sex object (Jill Fields Citation2007). Others, however, have argued that their consumption can be understood as an act of resistance to the selfsame: a feminist desire for self-love and actualization (Janice Odom Citation2016; Nancy Lyons Citation2005; Astrid Van den Bossche Citation2014).

Whether considered oppressive or emancipatory, the campaign exemplifies the structural workings of patriarchal marketing (Lauren Gurrieri Citation2021), but scholars have yet to fully consider the responses of contemporaneous audiences, and explain how the ads became a popular cultural reference and a conduit for social communication (William Leiss, Stephen Kline, Sut Jhally, Jackie Botterill and Kyle Asquith Citation2018). The tagline cropped up across media, including comedy sketches, plugs on popular radio and television shows, event invitations, and even anecdotes that were reframed as Dream-like situations (also see Van den Bossche Citation2022). The brand was celebrated in the song “Dardanella” by Bing Crosby and Louis ArmstrongFootnote2 and in musical Top Banana,Footnote3 thus assuming widespread recognition. While commodity feminism has been critiqued for “elid[ing] the social dimension which conditions the contradictions experienced in daily life” (Robert Goldman, Deborah Heath and Sharon L Smith Citation1991, 336), popular responses to such advertising give a concrete form to how these contradictions are experienced: the reinvention, co-option, and repurposing of the Dreams and the Dreamer in jokes, costumes, newspaper columns, poetry, cartoons, and spoofs evidence a range of views on women’s bodies and societal roles.

The purpose of this article is to demonstrate that these archival traces can be used to reveal (Stephanie Decker and Alan McKinlay Citation2020) how the campaign led a rich and often conflicted life in the minds of its audiences, where humor was alternatingly used to challenge and reinforce the strictures of commercialized femininity. In the following, I will briefly detail the campaign and the archival materials that underpin this historical study, before presenting a range of responses. I trace, in particular, the reactions that deal with two specific preoccupations: a) the anxieties raised by the psychoanalytic mind, which expressed tensions between genders and what they were allowed to think; and b) the depiction of the aspiring body, which threatened the (economic) social order.

Maidenform’s dreams: the campaign and the archives

Running from September 1949 to August 1969, the Dreams navigated and, to some extent, reflected, the societal sea-changes that took place in the aftermath of World War II. They fit, in the first instance, in advertising’s attempt to reconcile women’s wartime bravery with domestic ideals of femininity (Emily Westkaemper Citation2017), and over time articulated an alternative vision of consumption to second-wave feminist critiques of capitalist oppression (cf. Joanne Hollows Citation2013). Maidenform’s ads mainly consisted of the depiction of a “Dreamer,” a fashionably dressed model who had, despite the care in her appearance, dressed her upper body only in a bra. The accompanying tagline explained that “I dreamed I […] in my Maidenform bra.” The ellipsis, which also informed the overall tableau, was filled by anything from mundane, everyday activities (e.g., “went shopping”), to the desirable (“went skiing”), the aspirational (“was a lady ambassador”), the fantastical (“was a mermaid”), the absurd (“was sawed in half”), and the plainly punny (“got a lift”). These two unwavering characteristics were enough to lend the Maidenform campaign a visual expression that could vary considerably throughout the 1950s and 1960s without losing its coherence as a campaign. They also provided the ads with a formula that distinguished them from their competitors: Maidenform’s models were rarely sultry; the ads always depicted the entirety of the body (thus avoiding hero-shots and close-ups, which were relegated to the back of women’s magazines and could otherwise be construed as “indecent”); and the backdrops never included other people (with the exception of a few cartoon figures).

The ads varied in representational style, as did the copy, the models, the format, the media schedule, and even the brand spelling and slogan. Yet until the mid-1960s, after which the campaign eventually petered out, there had been one more feature that sustained the series’ appeal: its sense of humor. Characterized by the use of puns and prosody, the copy was written in the first-person perspective and often made intertextual references, implying a witty and cultured Dreamer:

[1] “Hear the waves of applause, the oceans of compliments. I’m the luckiest mermaid ever […]” (1951)

[2] “I’m madder than a hatter, but it really doesn’t matter … ” (1955)

[3] “Here a stretch … There a stretch … Everywhere a stretch, stretch.” (1968)

As advertising executive Kitty d’Alessio, who had overseen much of the campaign’s development and eventually became president of luxury brand Chanel (US), reminisced:

People looked for [the Dreams] because they were campy. They certainly stopped traffic, people looked at them and people thought about them, remembered them and looked for the next one. We tried to put that element into the ads.Footnote4

Humor thus helped propel the Dreams campaign into popular culture, and Maidenform made a point out of inviting the attention of a much broader audience than was typically assumed in undergarment advertising. The ads were circulated in general interest publications such as the New York Times Magazine and replicated in window displays on trafficked commercial streets, thus travelling well beyond the confines of women’s magazines. In doing so, the ads were not only challenging the protected feminine sphere (the boudoir realm of bras, girdles, corsets, garters, stockings, and slips), but they recast the usual advertiser-to-audience relationship: they drew in “surplus” audiences (cf. Henry Jenkins, Sam Ford and Joshua Green Citation2013).

Maidenform’s commitment to a word-of-mouth strategy is also borne out by their continuous recycling of popular culture references and audience responses. They celebrated them because, in their own words, “[e]very time the Maidenform name (to say nothing of complete Maidenform ad copy) gets into print, more and more women decide that a bra that’s worth writing about is certainly worth buying.”Footnote5 Maidenform therefore reprinted any plugs, spoofs, jokes, and puns that they came across in the company’s employee magazine, the Maiden-forum, and their trade magazine, the Maidenform Mirror. The Maiden-forum compiled company announcements, employee news, sneak-peeks into life at the different Maidenform factories, retailer stories, general interest articles, and a variety of contributions by employees such as poetry, cartoons, and even children’s drawings (also see Vicki Howard Citation2001 on how Maidenform used the Maiden-forum to foster a commercial beauty culture amongst their employees). The Maidenform Mirror, on the other hand, was distributed to retailers and trade dealers every two months; it focused on communicating company news, announcing upcoming or ongoing promotions, celebrating retail initiatives, and introducing new products. By reprinting comedic reuses and responses to the Dreams in both publications, the company showcased its cultural and commercial successes to its business partners as well as its own employees, and effectively created an archive of the campaign’s reception (Van den Bossche Citation2022).

This study draws primarily on materials that were reprinted by Maidenform, but their origins vary widely: some of the cartoons, for example, were purposefully drawn for Maiden-forum or Maidenform Mirror readers, but most examples were lifted from other trade publications such as Broadcast, student campus magazines such as the Yale Record, and popular magazines such as Mademoiselle. The collection was further supplemented with findings in the Adam Matthew “Popular Culture in Britain and America 1950–1975” archive, and serendipitous yields from digital search engines (Michael Hancher Citation2016). There is often no clear authorship to the responses except for those produced by professional cartoonists, and it is therefore difficult to paint a useful picture of the authors’ gender, class, race, ethnicity, and sexuality. As noted by Van den Bossche (Citation2022) and more broadly by Jennifer Aston et al. (Citation2022), archival silences surrounding gender and gendered activities in advertising and business history require a rethinking of the role of the historian in recovering women’s experiences. In this case, the materials that I have gathered show how ordinary consumers and media professionals of both sexes felt compelled to respond to or riff on the campaign. I argue that the purposes to which the campaign was put exemplify how the depiction of women’s consumption could be used to debate more fundamental gendered concerns.

Co-opting, reinventing, and spoofing the dreams

By displacing a halfway dressed female body from the dressing room to the public arena, Maidenform demanded that audiences bring together two realms—the public and the private—to an in-between that shed new light on the undergarment and the woman wearing it. What kind of cultural logic could reconcile a space that blended the hidden with the exposed, the domestic with the worldly, and the sensual with the everyday? And where did this place the idealized public figure of the chic and laborious suburban housewife?

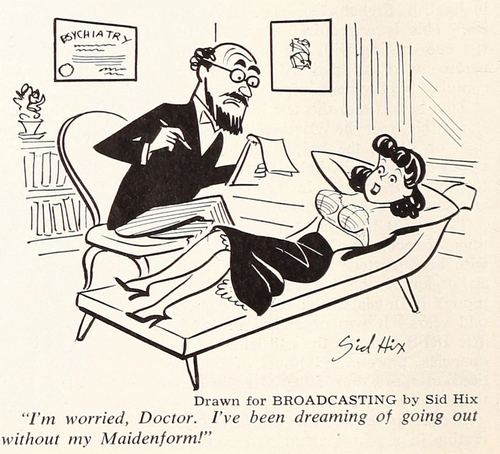

As highlighted above, the campaign’s seriality was key to its prolificacy: for audiences, half the fun was in imagining what the Dreamer did next. Yet audiences did not only imagine, they articulated: readers took pleasure in mimicking the ads’ witty taglines both in form and in spirit. , for example, shows the Maidenform Mirror reprint of a postcard that was sent to Maidenform headquarters with a request for a free style booklet. This particular postcard distinguished itself from other requests because it was addressed as follows:

Figure 1. “In the mail … Maidenform receives dreamy postcard,” Maidenform Mirror, May 1954, p. 8. Image taken by author from the Maidenform Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

I dreamed I was a postman and I rang twice and delivered this to – Maidenform New York 16. N.Y.

A little flourish on the “i” in Maidenform imitates the brand logo, and on the back, the sender completed the joke with a doodle of a postal officer in action. Repurposed in this way, the use of the tagline indicated a tacit approval of the original, and a desire to use this approval to foster a sense of belonging with others. Piggybacking on this engagement, Maidenform organized tagline contests that earned contestants cash prizes and free holidays. The entries would not have looked out of place in the series: a “graceful, grey-haired grandmother,” for example, “dreamed I found the Fountain of Youth;” another winning contestant “dreamed I was just a silhouette until I was spotlighted in my Maidenform bra.”Footnote6

Everyday readers were not the only ones to engage playfully with the campaign. Maidenform encouraged trade and retail partners to follow suit, often offering materials for stores to customise at will. Numerous newspaper “co-op” ads made use of the license to copy the ads in the early 1950s, such as for example department store Woodward & Lothrop’s 1952 “I dreamed I went shopping at ‘Woodies’” in the Washington Post. Letting go of the Dreamer was both an astute and risky tactic for the company: the Dreams proliferated, but there was no controlling how they were reworked. Department store Hecht’s, for example, cheekily placed two dreaming women in an “adult western” (a much more explicit reference to sex than Maidenform would allow) and exposed not only their bras, but also revealed a girdle. Some of these tie-ins allowed Maidenform to observe how the boundary of propriety was shifting, and to tiptoe along: Maidenform showed a model in both bra and girdle just a few months later. But the path to problematic parodies was a short one: a New York Journal-American columnist, for example, reported on a spoof created by the owner of bed sheets manufacturer Spring Cotton Mills Co., who “takes great joy in writing the ribald ads for his product […in] such national magazines as will accept them.”Footnote7 Titled “I dreamt I went shopping without my slip,” the ad showed an image of tennis player Gertrude Moran—who reached infamy when her lace knickers became visible during a match in Wimbledon 1949—and told the story of a Dreamer who drums up a crowd of male admirers as she rushes to a store without her slip. She is offered a job demonstrating a “pulsating mattress,” before she wakes up from her dream.Footnote8 Though her reasoning was not clarified in the press article, Maidenform founder Ida Rosenthal expressed the wish in 1960 that the industry would abandon cooperative advertising altogether.Footnote9

Many of these reworkings thus give insight into how the public grappled with the notion that the female body had been exposed to a broad cast of audiences: they pushed the portrayal of the Dreams to their limits, and articulated the cultural anxieties that they gave rise to. Texts that spoof usually generate an interpretive distance from which the reader is invited to take a critical stance towards the original, and a number of elements that made the Dream acceptable to its mass audiences were put under scrutiny by inverting them, thus “expos[ing] the model’s conventions and lay[ing] bare its devices” (Ziva Ben-Porat Citation1979, 247). In the following, I turn to two of these devices: First, I discuss the depiction of a mind that dreams, and unpack resulting anxieties specific to the early 1950s. Second, I look at the depiction of a body that aspires, tracing concerns that evolved throughout the late 1950s and segued into the counter-cultural 1960s.

Depicting the dreaming mind: policing mental freedom

In 1951, two years after the publication of the first Dream, a reporter for the Hartford Courant used the Maidenform Dreamer as a figure to press upon readers the psychological pressures faced by astronauts as a consequence of the hardships and isolation of their occupation. He explains:

[The astronauts] also suffer severe and strange hallucinations. After Air Force tests, some subjects reported seeing little men running all over the control boards.

Thus, the space traveler is likely to give the girlie who continually dreams she is going some place in her Maidenform bra a run for her lingerie.Footnote10

The reporter thus shows how widely recognizable the antics of the Dreamer had become, but also condescendingly dismissed “the girlie’s” aspirations as delusions. Such dismissals exemplify one side of a fault line in interpretation that either celebrated the mental freedoms showcased by the Dreams, or met them with opprobrium.

In the early 1950s, the Dreamer’s oneiric activities were commonly interpreted along Freudian lines as the expression of wish fulfilment: the articulation of a secret desire. While the reference to Freud could have been (and was) perceived as amusing by itself, it also doubled as a widely peddled explanation of the campaign’s success: the very suggestion of sexual transgression was supposedly liberating to women, thereby compelling them to purchase the product that was advertised (Packard Citation1957). The belief that psychoanalysis could persuade, and even “brainwash” (Daniel Pick Citation2022), audiences into acts of consumption was rapidly gaining popularity in advertising circles (Westkaemper Citation2017). Psychoanalysis offered not only an explanation for how the mind worked, but also how it could become deviant: the horrors of fascist Germany, the fearsome anti-communist persecutions of the McCarthy era, myths about the Soviet Union’s brainwashing superpowers, and a new discomfort with unbridled capitalism and mass advertising fueled the American citizen’s fear of losing control and inadvertently engaging in unsanctioned behavior (Lawrence R Samuel Citation2013; Pick Citation2022). As a result, the Freudian theory of a libidinous subconscious that could rebel at any moment gave audiences a particular conception of the fragility of the mind.

Even though the campaign’s origins did not involve psychoanalytic research methods, Maidenform was viewed as a prime example of the power of psychoanalytic advertising. As a contemporaneous pundit opined:

whether conscious or not, the wish to appear naked or scantily clad in a crowd of people is present in most or all of us. The copy writer […] permits the reader, by identification with the girl in the advertisement to fulfil this exhibitionistic wish.Footnote11

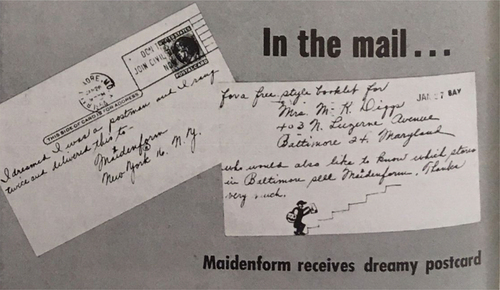

Exhibitionism—which itself was a highly gendered interpretation of the image—posed a problem for sexual morality, and as such needed to be stemmed. One way was to reintroduce shame: In Los Angeles Occidental College’s student magazine Fangsquire (1951), for example, the Maidenform model was cut out from the “I dreamed I went to the zoo” ad (1950) where she was fawning at the attention she was receiving, and superimposed on a college bar scene instead. Discovering that she had turned up in her “whoops!,” the model now looked as if she was hiding her face in embarrassment. Company cartoonist Sol Zasloff’s drawing imagined what might happen if the exhibition went further, and shows a woman blushing at the thought (). Both are examples of a reversal of the self-possession that characterized the original Dreamer: although the origin of the ads’ creative idea is unclear, one version of events credits copywriter Mary Filius with elevating the image from a gag about Freudian naked dreams, where the Dreamer blushes with embarrassment, to a message of confidence and enjoyment (Van den Bossche Citation2022).

Figure 2. A cartoon by Sol Zasloff, published in the Maiden-forum, May 1953. Image taken by author from the Maidenform Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

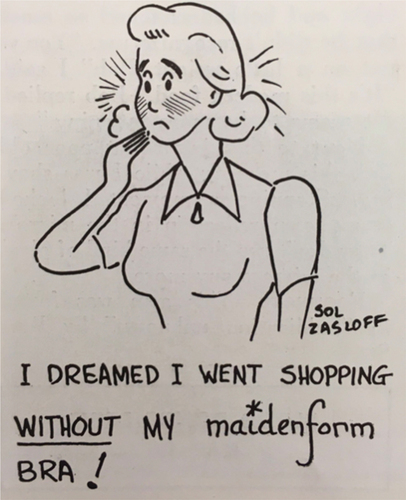

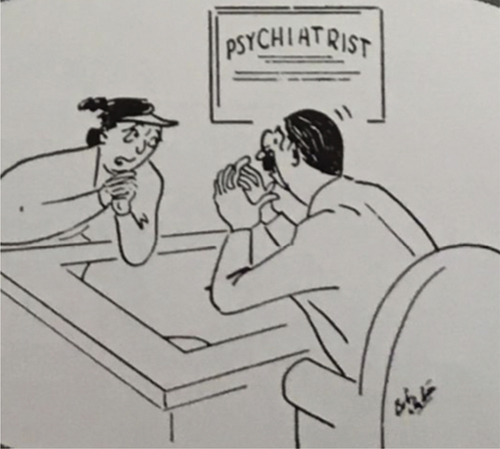

Another way to deal with the threat of exhibitionism was to suggest that the Maidenform wearer would require psychoanalytic intervention. A student medical journal, for example, ran a cartoon depicting a woman anxiously leaning over her psychiatrist’s desk: “ … and I keep dreaming I’m walking down Fifth Avenue, but without my Maidenform Bra” (). Patient and doctor are clasping hands in a mirror image of each other, her anxiety matched by his keen interest. The male gaze scrutinizes the female mind. Frequently, it was his perspective, rather than hers, that was cast as problematic. In the Advertising Age’s column “The Creative Man’s Corner,” an imagined conversation about “I dreamed I was a toreador” (1951) makes explicit the mental wanderings of men when confronted with her “exhibitionism.” The woman patiently explains:

Figure 3. A cartoon published in the Journal of the Student American Medical Association, March 1954, reprinted in the Maidenform Mirror, July-August 1954. Image taken by author from the Maidenform Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

You see, a bull is a symbol of fertility. Now. Imagine—and excuse me for smiling—you were a bull, and you saw a female matador out in the ring in a Maidenform bra. What would your reactions be? […] Exactly. Now, as I see it, this ad causes a woman to feel that, if she wears a Maidenform bra, men are going to charge at her the way a bull charges at a matador. […] as you know, men undress women with their eyes.Footnote12

As her interlocutor replies that the ad is illogical because when “I undress a woman with my eyes, I don’t stop until—,” she cuts him off and accuses him both of taking his imaginings too far, and of being overconfident in the mental faculties of his sex:

There you go being vulgar. That’s the trouble with you men. You’re always thinking the worst things. […] The way you act, men are the only logical creatures in the world. […] [The ad is] perfectly logical as far as my eyes are concerned, and as far as your eyes are concerned, I think you ought to read Popular Mechanics.

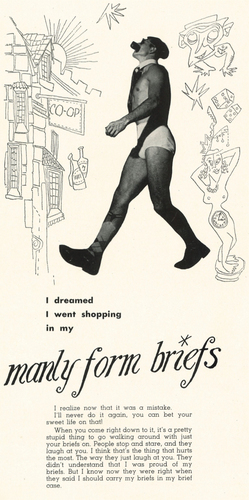

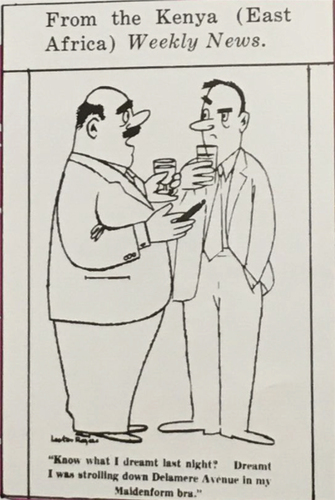

Ironic inversions (cf. Linda Hutcheon Citation1985), where the Dreamer becomes male (or, more accurately put, where males dare dream like the Dreamer), spelled out the vulnerabilities normally ascribed to women. The Yale Record imagined a man shopping in his “manly form briefs”—but instead of extolling the freedom of the dream, he denounces it as “a stupid thing to do:” “People stop and stare, and they laugh at you. They didn’t understand that I was proud of my briefs” (). Echoing the line-drawn style of the early Dreams, the spoof materializes the man’s dreamscape in the background: Featuring a naked woman with a clock on her stomach (symbolizing, perhaps, the pressure to procreate?), dice, liquor bottles, and a little monster, the scene suggests a rather more risqué subconscious than the Maidenform woman’s. Both this, his upright strut, and the concluding pun (“I should carry my briefs in my briefcase”) mark a double edge in the joke: this Dreamer’s dream was best left (by his own confession) unexplored. Similarly, Kenya Weekly News showed two men in suits enjoying a cocktail and cigar, with the one confiding in the other, “Know what I dreamt last night? Dreamt I was strolling down Delamere Avenue in my Maidenform bra” ().Footnote13 The addressee’s raised eyebrow tells it all: what was his companion doing, imagining himself in a bra, in public?

Figure 4. A spoof in the Yale Record, January-February 1950. The copy reads: “I realize now that it was a mistake./I’ll never do it again, you can bet your sweet life on that!/When you come right down to it, it’s a pretty stupid thing to go walking around with just your briefs on. People stop and stare, and they laugh at you. I think that’s the thing that hurts the most. The way they just laugh at you. They didn’t understand that I was proud of my briefs. But I know now they were right when they said I should carry my briefs in my brief case.” Courtesy of the Yale Record and the Archives at Yale.

Figure 5. Cartoon reprinted in the Maidenform Mirror, October-November 1959. The copy reads: “Know what I dreamt last night? Dreamt I was strolling down Delamere Avenue in my Maidenform bra.” Image taken by author from the Maidenform Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

Upon closer inspection, however, jokes about the psychology of the Dreamer could also offer more subversive readings. Sid Hix’s cartoon published in Broadcasting shows a fashionably coiffed young woman lying down on a chaise longue: “I’m worried, Doctor,” she says, “I’ve been dreaming of going out without my Maidenform!” (). The psychiatrist looks remarkably like Freud and is staring at the model’s breasts with a vague look of panic on his features. She, on the other hand, is perfectly comfortable: so comfortable that she is not just in her bra, but her arms are bent casually underneath her head, and her slip is showing underneath her skirt (at the time, this would have been considered unseemly). The Dreamer’s poise (she was, to quote radio host Dorothy Kilgallen Kollmar, “happy as a clam”Footnote14) was a crucial detail in the original ads that implied she was not a Freudian dupe after all. By quoting the fashionable model’s self-possession, the cartoon was therefore also mocking the psychoanalytic fever that shrouded the campaign’s reception, and that might have elicited the audience’s skepticism. A question mark thus hovered over both characters: was she neurotic, or was she self-possessed? Was he an expert, or was he a pervert? The cartoon played with the different minds at stake and articulated the consequences. It might have revealed the model’s neurosis to some audiences, but to others, it would have betrayed the limits of the poor psychiatrist’s abilities, and cast judgement over those who sided with him. This joke was as much on Freud and his Madison Avenue acolytes as it was on the Dreamer.

Dressing the aspiring body: figure control as conduit to agency and ability

By the late 1950s, jokes about the psychoanalytic mind had run their course, and the campaign had fully transitioned into full-page colour advertisements that focused on word play, intertextual referencing, and spectacular new settings: “I dreamed I had a stylish carriage” and “I dreamed I drove them wild,” for example, riffed on popular films Gigi (1958) and Ben Hur (1959), while “I dreamed I was a trademark” poked fun at the usually bare-breasted White Rock fairy. A remarkable 1961 ad, “I dreamed I was a knockout,” blended the image of Marilyn Monroe with that of boxer Gorgeous George. These were far more suggestive than their earlier counterparts and fully used the power of double entendre to elicit a chuckle; they worked because laughing about sex was becoming permissible. Thus, rooted in the early 1950s but more fully articulated as the 1960s ramped up towards counterculture revolutions, spoofs and parodies began targeting the norming of the female body itself, and how it featured in the landscape of women’s economic agency and opportunity.

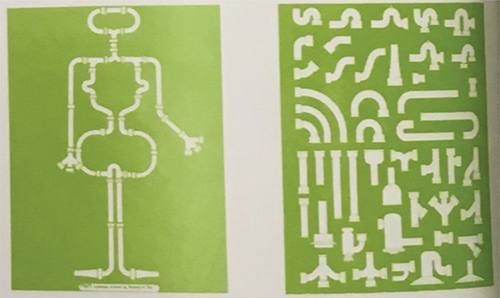

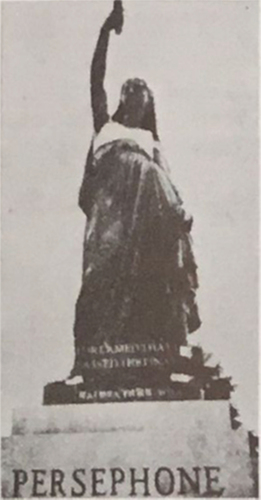

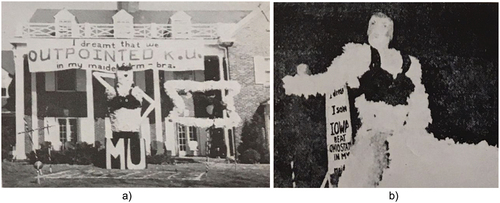

In 1963, a pipe manufacturer set a contest in which participants were tasked with “making a thing” by assembling pipe connector pieces and naming the result. The winning submission, depicted in , was titled “I dreamed I had a pipe dream without my Maidenform bra.”Footnote15 The image shows an abstracted female figure with two u-pipes as breasts, and two larger bends as hips. The pun and image speak to the inventiveness of this contestant, but they also articulate, in no uncertain terms, the connection that had been forged between Maidenform, “figure control,” and achievement (Jane Farrell-Beck and Colleen Gau Citation2002). , for example, shows how the ads were brought to life in 1962 in a college prank at Butler University, Indianapolis, where a campus statue of Persephone was dressed in a bra and a sign reading, “I dreamed I passed the final in my … ” The prank suggested that this college fixture was going to do very well in her upcoming examinations thanks to her new undergarment “supporting” her normally nude breasts. No stranger to campus life, the Dreamer was frequently adopted by college students across the United States as a makeshift mascot to adorn homecoming floats or sorority and fraternity houses, often having her dream that she had beaten a rival institution in a sports competition (see ).

Figure 7. The winning entry to pipe manufacturer Barlett-Snow-Pacific’s “make a thing” contest, Maidenform Mirror, November-December 1963. Image taken by author from the Maidenform Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

Figure 8. Photograph of the Persephone statue dressed in a bra at Butler University, Indianapolis, Maidenform Mirror, May-June 1962, p. 6. Image taken by author from the Maidenform Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

Figure 9. Left to right: a) Fraternity house homecoming decoration at Missouri University, Maidenform Mirror, April-May 1955. b) Iowa State University float, Maidenform Mirror, December 1952 – January 1953. Image taken by author from the Maidenform Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

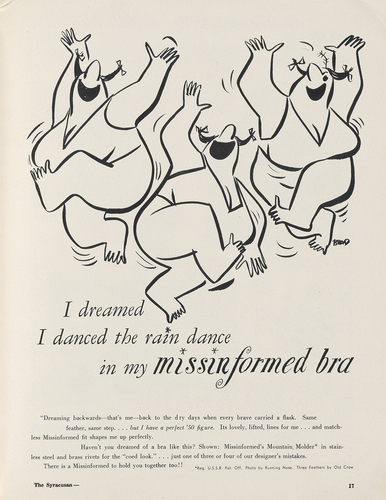

To understand the spoofs of the 1960s, we must go back to the way in which curvature was seen to structure the physical (and thus social) relationship between men and women in the 1950s (Elizabeth Matelski Citation2017). At the time, a commonly expressed point of tension was the fear that women might be deluding themselves by trying to shape their bodies into submission. Some commentaries outrightly body shamed: Implying that large figures were irremediable, the Coast Guard Academy in Connecticut spoofed the Dream by showing one of their male cadets in his “skivies [sic]:” “There is a made-in-form for every figure. Small, medium, or impossible.”Footnote16 Other critics questioned striving for these body ideals more generally: Bradley Anderson (creator of Marmaduke) deplored the women who were “dreaming backwards” in their “missinformed” [sic] bra (). In his cartoon, the voluptuous women are performing an ostensibly futile “rain dance,” their bow-tied pigtails mark them out as infantile, and the reference to materials such as “stainless steel and brass rivets” questions the wearability of an undergarment otherwise sold as competitively comfortable. The suggestion was that the women were gullible, rather than empowered.

Figure 10. A spoof by cartoonist Brad Anderson (creator of Marmaduke) published in Syracuse University’s Syracusan, May 1950, and reprinted in the Maidenform Mirror, August 1950. The copy reads: “Dreaming backwards—that’s me—back to the dry days when every brave carried a flask. Same feather, same step … but I have a perfect ‘50 figure. It’s lovely, lifted, lines for me … and matchless Missinformed fit shapes me up perfectly. / Haven’t you dreamed of a bra like this? Shown: Missinformed’s Mountain Molder* in stainless steel and brass rivets for the ‘coed look.’ … just one of three or four of our designer’s mistakes. / There is a Missinformed to hold you together too!” Image from the Syracuse University Student Publications Collection, University Archives, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries.

The question of whether women could or should “control” their bodies for societal advantage betrayed a disquiet about how doing so successfully could pose a threat to the economic order. The more common fear, frequently expressed in jokes about the disappointments of marriage, is exemplified in a reader’s letter to the Advertising Age, which, referencing the above-mentioned toreador ad, voiced concern over “the young ladies of this generation[’s …] bloodthirsty acrobatics just to show their ‘boobytraps.’” His pun out of the way, the reader fretted about “what the young men of the present generation think when they discover they have been cleverly deceived by false fronts of near impeccable perfection.”Footnote17 In other words, Maidenform was seen to assist women in inveigling men to secure financial advantage under false pretenses.

These critiques coincided with an increased discussion of sex and in particular women’s sexuality in popular media (Kinsey’s and later Master & Johnson’s research on sex were topics du jour), and a loosening of mores as a result. One sorority at Iowa State provided a concrete example in a poem that they sent to Maidenform when they won a prize for their “I dreamed I saw Iowa beat Ohio State in my Maidenform bra” float (). In the poem, they acknowledge the publicity that they brought to Maidenform, but proceed to reference the “panty raids” that had sprung up across colleges earlier in 1952 (John J Sloan and Bonnie S Fisher Citation2010):

Fifty thousand acclaimed our float

And hopped upon the Maidenform boat

We won a trophy that is true

Wasn’t that a good plug for you!

Perhaps you heard of us last Spring

When “Panty Raids” were quite the

thing,

The fellas raided both House and

Dorm —

For they too wanted a Maidenform.

Now we’re short of lots of kissing

For in our figures something’s missing

Could it be that we’re not warm

Cuz someone cupped our Maidenform.

The form of the poem indicates that it was meant to be taken in good humor, but its contents point to events that were deeply threatening to women’s safety and integrity: historical accounts of the raids report various levels of violence and assault across campuses. Explained away by one university official as the result of “sex, simple-mindedness, and just a means of blowing off steam” (Paulina Ann Batterson Citation2001, 145), the raids exemplified how perceptions of sexual liberation—materialized in the literal theft of underwear—were used to write off male violence. Women were at best subjected to double ignominy: not only was their space and privacy invaded, but the looters made off with their possessions.

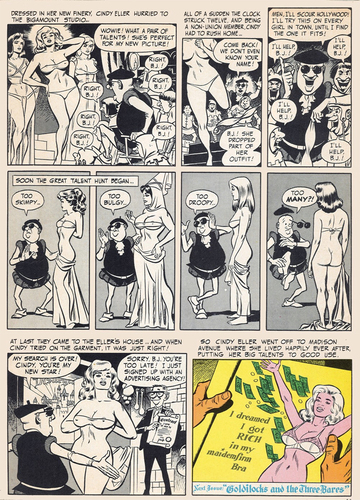

By the early 1960s, the threat of the aspiring body matured into fears that women might successfully turn to occupations that could profit from the male gaze. This anxiety is explored in a strip by comic artist Wallace Wood for the men’s magazine Cavalcade in 1965 (), in which he imagines Cinderella turning down her prince (figured here as an erotic film director in search of his new star) for a modelling job in advertising.Footnote18 This erotic retelling contains a few jabs at the advertising world and capitalism in general,Footnote19 but more importantly, it casts Maidenform as an alternative route to success (“I dreamed I got RICH”). (According to a Maidenform ad executive, the models were indeed paid a double hourly rate because of the undesirability of the work; Kitty d’Alessio Citation1990.) While her occupation is not conventionally aspirational, it does show a woman in possession of her body and, as a result, independent means. Though met with opprobrium, accounts that assured women could have pre- or extramarital sex as well as financial independence were beginning to take a broader foothold through publications such as Helen Gurley Brown’s Sex and the Single Girl (1962).

Figure 11. Second page of “Far Out Fables: The story of Cindy Eller” by Wallace Wood, Cavalcade, 1965.

While Far Out Fables’ eroticism permitted a more celebratory reading of the emancipated woman, other satires spelled out her threat to the institution of marriage and its moralistic division of labor. A high-profile satire by MAD Magazine (), “I dreamed my husband caught me posing,” describes how economic necessity led the model to take a job posing in a bra and a slip. The model stands defiant as the husband’s jaw slacks in “purple rage” at the discovery. Complicit and equally caught in the act, the cameraman hides his face in his hand and glances at staff outside the frame (or more concretely, the reader). Unlike the Dreams, or the Cinderella parody, there is nothing glamorous or fantastical about the scene. The Dreamer’s innocence had been obliterated: this supposedly respectable (by virtue of being married) woman posed knowingly for money.

Figure 12. A MAD magazine spoof, 1962. The copy reads: “PURPLE RAGE … that’s what he was in … especially since I’d told him it was for ‘Pepsi-Cola’! But what’s a professional model supposed to tell her guy … when lingerie ads are getting sexier and sexier, and they’re just about the only jobs available these days? Hah?”

Conclusion

What then can we learn from the parodies, spoofs, jokes, and other such reworkings of Maidenform’s advertisements? Gender historians have productively revived perspectives that bring the subversive potential of laughter back to the fore (e.g., Anna Foka and Jonas Liliequist Citation2015), and there is ample contemporary evidence from media studies and marketing research demonstrating that people use humorous devices to upend consumerist messaging through playful resistance (e.g., Ilona Mikkonen and Domen Bajde Citation2013) and culture jamming (e.g., Marilyn DeLaure and Moritz Fink Citation2017). These bodies of literature agree that humor has the ability to break open the ordinary and effect change, just as much as it has the ability to reinforce the status quo (Simon Critchley Citation2002). Yet historical considerations of everyday gendered uses and critiques of promotional media do not feature large in our understandings of 20th century consumer culture.

The plurality evident in the humoristic responses to the Maidenform Dreams belies the simplicity of the psychoanalytic explanation that has hitherto framed our understanding of the campaign’s impact, and highlights how humor was a key device both in the ads and in its cultural uptake. Assessing Maidenform’s trajectory in light of these responses provides a way into questioning the common depiction of the 1950s as reigned by a “monolithic and one-dimensional” Cold War culture marked by political conservatism and social conformity (Martin Halliwell Citation2007, 4). Not only did Maidenform actively seek out engagement and word-of-mouth advertising by challenging undergarment advertising norms, the tagline and imagery were spontaneously adopted to unravel the ramifications of aspiring female bodies and minds.

Without further reception evidence, it is difficult to tell how many of the examples offered above were intended—and consistently read—as ironic or supportive takes on mid-century gender ideals; as Liliequist and Foka note, “laughter can be disciplining and rebellious, repressive and subversive, or self-ironic and self-degrading” (Citation2015, 1). Advertisements that draw on gender norms are particularly prone to such interpretive instability (Stephen Brown, Lorna Stevens and Pauline Maclaran Citation1999) because the tense relationship between feminism, femininity and commerce, especially in the wake of second-wave feminism, tended to cast mainstream consumption as un-feminist (Linda M Scott Citation2006). Yet paying attention to the audience’s responses can work as a counterforce against “trivializing the complexities of women’s [commercial, representational] lives” (Gurrieri Citation2021, 365). As Kathy Peiss noted on the cosmetics industry, the market for feminine products “should be understood not only as a type of commerce but as a system of meaning that helped women navigate the changing conditions of modern social experience” (Citation2011, 6). I extend this argument by pointing to the consumption of advertising itself as a conduit to social debate.

The Dream tagline continued to be repurposed as a vehicle to satirize endemic inequalities. In 1966, writer, academic and civil rights activist Julius Lester repurposed the Dream tagline in his essay “The angry children of Malcolm X” to point to deep disillusionments with a persistently racist society, a pacifying capitalist system, and the violence inflicted on Black civil rights workers:

How naive, how idealistic [Black civil rights workers] were then. They had honestly believed that once white people knew what segregation did, it would be abolished. But why shouldn’t they have believed it? They had been fed the American Dream, too. They believed in Coca Cola and the American Government. “I dreamed I got my Freedom in a Maidenform bra.” They were in the Pepsi Generation, believing that the F.B.I. was God’s personal emissary to uphold good and punish evil.Footnote20

Lester’s redeployment of the tagline highlighted how White women had achieved freedoms from oppression and violence that Black people conclusively had not. Similarly, drawing on Maidenform’s legacy of upheaving through public attire, equal rights activist Leo Skir’s account of his city council hearing testimonial on facing discrimination as a gay man in 1971 was titled “I should have worn my Maidenform bra!” to indicate that he would have made more of an impact had he worn a dress in solidarity with transgender people.Footnote21

While social consensus had been drifting back to a normalization of highly restrictive gender roles, the Dreams gave an opportunity to challenge the tide by breaking down the barriers between the public and the private, and revealing an agentic female mind. By following, tweaking, and breaking the blueprint set out by the original ads, audiences expressed the pleasures, discomforts, illuminations, incongruences, and censures that these ads elicited. Many of the examples above were neither supportive nor celebratory of women, but the question of gender and aspiration had been broached nonetheless.

Ironically, Maidenform’s intervention in the sector’s advertising norms was soon absorbed by the industry, and eventually made the Dreamer’s state of undress look modest in comparison to the counterculture woman of the late 1960s. Playtex’s last print campaign for its girdle, for example, featured a model whose breasts were covered only by her thick brown locks, staring intently at the reader. Jantzen took “the underworld in its stride” with sunglassed models flashing their underwear from underneath glossy black raincoats. These ads were neither witty nor coyly romantic, they were confidently sultry. Even the Dreams’ psychoanalytic connotations, once a source of novelty, became a common humorous trope in underwear advertising. In 1964, for example, a slip advertisement for Hollywood Vassarette featured a psychoanalyst’s couch in the background: “Oops! We’ve made a Freudian slip!”Footnote22 The innovation of the Dreams, which was to cheekily allude to the life of the female mind, had become commonplace. As stand-up comedian Phyllis Diller jested, “my best Maidenform bra is now a soup ladle.”Footnote23

Acknowledgement

My deepest thanks go to the welcome and help received at the Archives Center of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, as well as from participants at the Hagley Museum and Library fall conference, “Commercial Pictures and the Arts and Technics of Visual Persuasion,” where I presented an early version of this paper. This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council, the Scatcherd European Scholarship, Green Templeton College, and the Saïd Business School Foundation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Astrid Van den Bossche

Astrid Van den Bossche is Lecturer in Digital Marketing and Communications at the Department of Digital Humanities, King’s College London. She is particularly interested in scepticism, humour, and enchantment as forms of engagement with promotional culture, economic socialisation through fiction, and the application of computational methods in the study of consumer culture.

Notes

1. Stephen Baker, “Is the Maidenform Bra Gal Having Dreams of Nightmares?,” Advertising Age, June 24, 1963, NMAH.AC.0585 Box 2, Folder 7, Maidenform Collection, 1922–1997, Archives Center, National Museum of American History.

2. Crosby, Bing, and Louis Armstrong. Dardanella. Vol. Bing & Satchmo. Capitol Records, LLC, 1960.

3. Maiden-Forum. “‘Top Banana’ Features Maidenform in Supporting Role,” August 1954. NMAH.AC.0585 Box 22, Folder 10.

4. Kitty d’Alessio, “Interview with Kitty d’Alessio,” August 8, 1990, NMAH.AC.0585 Box 1, Folder 21.

5. “More on Maidenform ads by New York newspaper columnist,” Maidenform Mirror, June 1951, p. 8, NMAH.AC.0585 Box 19 Folder 0.

6. “MF Dream Contest a Huge Success,” Maiden-Forum, February 1956, NMAH.AC.0585 Box 21, Folder 0. “Dream-Contest Winners Feted,” Maiden-Forum, September 1957, NMAH.AC.0585 Box 21, Folder 0.

7. John McClain, “Mad about Manhattan: The Advertising World,” Maidenform Mirror, June 1951, NMAH.AC.0585 Box 19, Folder 0, Maidenform Collection, 1922–1997, Archives Center, National Museum of American History.

8. Ibid.

9. “Ida Rosenthal: ‘Industry’s Best Years to Come,’” Women’s Wear Daily, September 29, 1960(Women’s Wear Daily Citation1960).

10. “What They Say…,” Advertising Age, July 31, 1961, Internet Archive.

11. “Ad-Men’s Trade Magazine’s Applaud Maidenform Ads,” Maidenform Mirror, July 1953, NMAH.AC.0585 Box 19, Folder 0.

12. “The Creative Man’s Corner,” Advertising Age, April 23, 1951, Internet Archive.

13. Reprinted in the Maidenform Mirror, October-November 1959, NMAH.AC.0585 Box 20 Folder 0.

14. “Maiden Form’s ‘Dream Series’ Hits the Airways on WOR,” Maidenform Mirror, October 1949, NMAH.AC.0585 Box 19, Folder 0.

15. “A Maidenform Pipe Dream…,” Maidenform Mirror, December 1963, NMAH.AC.0585 Box 20, Folder 0.

16. Reprinted in the Maidenform Mirror, December 1952 – January 1953, NMAH.AC.0585 Box 19 Folder 0.

17. Carl Culpepper, “Voice of the Advertiser: A Matter of Form,” Advertising Age, May 14, 1951, Internet Archive.

18. “Far Out Fables: The Story of Cindy Eller,” Cavalcade, February 1965, Vol 5 N. 2, p.40–41. Internet Archive.

19. Note that Wood’s career saw him work both for Madison Avenue and the satirical MAD magazine, spoofing the very same commercial culture that he was helping create.

20. Lester, 1966, “The Angry Children of Malcolm X,” in Look Out, Whitey, Black Power’s Gonna Get Your Mama. Copy consulted in the Adam Matthew archive, “Popular Culture in Britain and America, 1950–1975,” p. 3.

21. Skir, 1971, “Equal Right Hearings Continue. ‘I Should Have Worn my Maidenform Bra!,” Gay, December 20, p. 6.

22. “Advertisement for Hollywood Vassarette,” Mademoiselle, April 1964, Open Library.

23. “Phyllis Diller’s Gag File,” March 13, 1968, 2003.0289.01.01 Drawer No. 33, Part 2, National Museum of American History.

References

- Aston, Jennifer, Hannah Barker, Gabrielle Durepos, Shenette Garrett-Scott, Peter James Hudson, Angel Kwolek-Folland, Hannah Dean, Linda Perriton, Scott Taylor, and Mary Yeager. 2022. “Take Nothing for Granted: Expanding the Conversation About Business, Gender, and Feminism.” Business History 66 (1): 93–106. doi:10.1080/00076791.2022.2123470.

- Batterson, Paulina Ann. 2001. Columbia College: 150 Years of Courage, Commitment, and Change. Columbia: University of Missouri Press.

- Ben-Porat, Ziva. 1979. “Method in Madness: Notes on the Structure of Parody, Based on MAD TV Satires.” Poetics Today 1 (1/2): 245–272. doi:10.2307/1772049.

- Brown, Stephen, Lorna Stevens, and Pauline Maclaran. 1999. “I Can’t Believe It’s Not Bakhtin!: Literary Theory, Postmodern Advertising, and the Gender Agenda.” Journal of Advertising 28 (1): 11–24. doi:10.1080/00913367.1999.10673573.

- Burns-Ardolino, Wendy A. 2007. Jiggle: (Re)shaping American Women. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- Coleman, Barbara J. 1995. “Maidenform(ed): Images of American Women in the 1950s.” Genders 21 (3).

- Critchley, Simon. 2002. On Humour. London: Routledge.

- d’Alessio, Kitty. 1990. “Interview with Kitty d’Alessio.” In Maidenform Collection, 1922-1997. Archives Center, National Museum of American History.

- Decker, Stephanie, and Alan McKinlay. 2020. “Archival Ethnography.” In The Routledge Companion to Anthropology and Business, edited by Raza Mir and Anne-Laure Fayard, 17–33. New York: Routledge.

- DeLaure, Marilyn, and Moritz Fink, eds. 2017. Culture Jamming: Activism and the Art of Cultural Resistance. NYU Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1bj4rx2.

- Farrell-Beck, Jane, and Colleen Gau. 2002. Uplift: The Bra in America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Fields, Jill. 2007. An Intimate Affair: Women, Lingerie, and Sexuality. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Foka, Anna, and Jonas Liliequist, eds. 2015. Laughter, Humor, and the (Un)making of Gender: Historical and Cultural Perspectives. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Goldman, Robert, Deborah Heath, and Sharon L. Smith. 1991. “Commodity Feminism.” Critical Studies in Mass Communication 8 (3): 333–351. doi:10.1080/15295039109366801.

- Gurrieri, Lauren. 2021. “Patriarchal Marketing and the Symbolic Annihilation of Women.” Journal of Marketing Management 37 (3–4): 364–370. doi:10.1080/0267257X.2020.1826179.

- Halliwell, Martin. 2007. American Culture in the 1950s. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Hancher, Michael. 2016. “Re: Search and Close Reading.” In Debates in the Digital Humanities, edited by Matthew K. Gold and Lauren F. Klein, 118–138. Minneapolis London: University Of Minnesota Press.

- Hollows, Joanne. 2013. “Spare Rib, Second-Wave Feminism and the Politics of Consumption.” Feminist Media Studies 13 (2): 268–287. doi:10.1080/14680777.2012.708508.

- Howard, Vicki. 2001. “‘At the Curve Exchange’: Postwar Beauty Culture and Working Women at Maidenform.” In Beauty and Business: Commerce, Gender, and Culture in Modern America, edited by Philip Scranton, 195–216. New York ; London: Hagley Perspectives on Business and Culture Routledge.

- Hutcheon, Linda. 1985. A Theory of Parody: The Teachings of Twentieth-Century Art Forms. New York ; London: Methuen.

- Jenkins, Henry, Sam Ford, and Joshua Green. 2013. Spreadable Media: Creating Value and Meaning in a Networked Culture. New York: New York University Press.

- Leiss, William, Stephen Kline, Sut Jhally, Jackie Botterill, and Kyle Asquith. 2018. Social Communication in Advertising: Consumption in the Mediated Marketplace. New York: Routledge.

- Liliequist, J., and A. Foka. 2015. “General Introduction.” In Laughter, Humor, and the (Un)making of Gender: Historical and Cultural Perspectives, edited by A. Foka and J. Liliequist, 1–2. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lyons, Nancy. 2005. “Interpretive Reading of Two Maidenform Bra Advertising Campaigns.” Clothing and Textiles Research Journal 23 (4): 322–332. doi:10.1177/0887302X0502300412.

- Matelski, Elizabeth. 2017. Reducing Bodies: Mass Culture and the Female Figure in Postwar America. London: Routledge.

- Mikkonen, Ilona, and Domen Bajde. 2013. “Happy Festivus! Parody as Playful Consumer Resistance.” Consumption Markets & Culture 16 (4): 311–337. doi:10.1080/10253866.2012.662832.

- Mills, Nancy Patton. 2006. Portraits through the Lens of Historicity: The American Family as Portrayed in ‘Ladies’ Home Journal’, 1950–1959. Ph.D., Duquesne University.

- Molholt, Stephanie. 2008. “A Buck Well Spent: Representations of American Indians in Print Advertising since 1890.” Ph.D., Arizona State University.

- Odom, Janice. 2016. “Desire as Resistance: Narcissism and Visual Rhetoric in the 1949 Maidenform Bra ‘I Dreamed’ Ad.” Women’s Studies in Communication 39 (1): 1–27.

- Packard, Vance. 1957. The Hidden Persuaders. New York: Penguin Books.

- Peiss, Kathy Lee. 2011. Hope in a Jar: The Making of America’s Beauty Culture. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Pick, Daniel. 2022. Brainwashed: A New History of Thought Control. Main edition ed. London: Wellcome Collection.

- Rutherford, Paul. 2007. A World Made Sexy: Freud to Madonna. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Samuel, Lawrence R. 2013. Freud on Madison Avenue: Motivation Research and Subliminal Advertising in America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Scott, Linda M. 2006. “Market Feminism: The Case for a Paradigm Shift.” Advertising & Society Review 7 (2). doi:10.1353/asr.2006.0026.

- Simington, Maire Orav. 2003. “Chasing the American Dream Post World War II: Perspectives from Literature and Advertising.” Ph.D., Arizona State University.

- Sloan, John J., and Bonnie S. Fisher. 2010. The Dark Side of the Ivory Tower: Campus Crime as a Social Problem. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Van den Bossche, Astrid. 2014. “The Id Goes Shopping in Its Maidenform Bra: Navigating Gender Spheres in the Postwar ‘Dreams’ Campaign.” Advertising & Society Review 15 (2). doi:10.1353/asr.2014.0012.

- Van den Bossche, Astrid. 2022. “In Search of the Female Gaze: Querying the Maidenform Archive.” In The Routledge Companion to Marketing and Feminism, edited by Pauline Maclaran, Lorna Stevens, and Olga Kravetz, 120–137. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Westkaemper, Emily. 2017. Selling Women’s History: Packaging Feminism in Twentieth-Century American Popular Culture. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

- Women’s Wear Daily. 1960. “Ida Rosenthal: ‘Industry’s Best Years to Come,’”.