ABSTRACT

In this article, I examine the emergence of “meme-feminism” on Iranian social media, which adopts innovative tactics to combat gendered hate online. I propose the concept of “memeing back” at misogyny and numerous gendered inequalities as not only a unique feminist tactic but also a political and satirical world-building practice. With a detailed analysis of theorizations of (digital) feminist activism and mediated visual humor, I demonstrate how the adoption of memes can, through anonymity and visual community-building, extend beyond dominant forms of popular feminism to combat the pervasion of anti-feminism on Iranian social media. I further unpack how this tactic mobilizes feminist memes by utilizing shared aesthetic visualization, a feminist politics of exposure, and visual nagging as embodied and mediated interventions to critique socioeconomic inequalities impacting women-identifying individuals in Iran. On this basis, I argue for the significance of online memes and the “memeing back” tactic in advancing feminist demands under suppressive, violent, and capitalist states.

Introduction

The Instagram pages @zanan_memes and @women_memes1, which post memes with Farsi captions, are among the very first feminist meme pages on Iranian social media. Their bio states, “Meme-ha-ee Baray-e Zanan; Ba Seday-e Boland Bekhandid, Bayad be Seda-ye Ma Adat Konand” (Memes for women (cis); laugh out loud, they [anti-feminists] should get used to our voice). Consistent with this statement, the pages have posted memes almost every day since early 2021 to combat the rising anti-feminism on Iranian social media as well as expose the deeper patriarchal issues that dominate Iranian society in visually innovative and potentially disruptive ways. The memes they post use elements of humor and trolling in a cartoonish and anonymous style. The pages were created in response and as an alternative space to the rise of numerous Iranian anti-feminist online pages. Particularly, under conditions where feminist participation on Iranian social media poses immense material risks of arrest, murder, and imprisonment in the country—not to mention everyday or sudden mass cyberhate attacks—the anonymous memes posted by @women_memes1 seem to visually and creatively combat anti-feminist misogyny and institutionalized violence and the pervasive everyday inequalities in Iran, regardless of “who” is the admin of the page or its possible longevity online. The memes are produced and circulated through tactics of “recombinant adaptation” (Eckart Voigts Citation2017) and aesthetic pop cultural reconfigurations to resonate visually with a broader audience, and yet they remain unique to the Iranian context. This tactical adaptation and aesthetic mobilization of memes serves to mediate, in a humorous and collective way, and challenge intersectional and structural gendered inequalities in Iran. This emerging radical act makes the page an especially interesting case as one of the first feminist pages on Iranian social media.

This article examines the emerging Farsi meme-feminism against the rise of mediated anti-feminism in Iran to demonstrate the importance of this case for highlighting the intersectional struggles of digital activism beyond Western contexts and within the restrictive and violent theocratic context of Iran. Such emerging forms of digital feminism are context-specific yet interconnected and embedded within the broader global struggles, tactics, and forms of networked feminism (Shana MacDonald, Brianna I. Wiens, Michelle Macarthur, and Milena Radzikowska Citation2021) and aesthetic intervention. I detail what I consider the main elements of the emerging Iranian “meme-feminism,” namely world-building through shared tactics of adaptations, aesthetic humor, and visual trolling. I propose the term “memeing back” to describe a unique tactic and appropriate concept for unpacking the transnational interconnectivity of shared global and local humorous vernaculars, image-makings, and solidarity expressed via feminist reconfigurations of new media aesthetics.

As I explain below, the notion of “memeing back” captures how innovative forms of digital feminism have the potential to not only challenge mediated anti-feminism and hate but also cultivate community-building and solidarity among feminists across local and global settings. I address the following questions: How have feminist visual humor and “meme-feminism” acted as affective tools of digital activism on Iranian social media to challenge rising anti-feminism and hate online? How have they served as world-building tactics through community and anonymity? What do “memeing back” and “meme-feminism” look like on Farsi Instagram and Telegram in particular, and what are their aesthetic and tactical interventions? Finally, what are the challenges and contributions of meme-feminism in beyond-Western contexts and broader digital feminisms?

Iranian feminisms vs. the growing Iranian manosphere and anti-feminism

The contemporary global scene of digital activism is increasingly becoming a site of conflict for feminists who are struggling to secure their rights and visibilities and combat the intensifying hatred directed at them online (Debbie Ging and Siapera Eugenia Citation2019; Adrienne L. Massanari and Shira Chess Citation2018; Jacqueline Ryan Vickery and Tracy Everbach Citation2018). This troubling period has been described as a “battleground” on which feminists and anti-feminists (Jessica Ringrose and Emilie Lawrence, Citation2018, 212) fight to shape publics and counterpublics through “popular feminism” or “networked misogyny,” respectively (Sarah Banet-Weiser Citation2018). On this battleground of demands for either spectacular popular feminist visibility or the structural, violent, and misogynist “eliminationism” (Jack Z. Bratich Citation2022) of anti-feminist activism, the struggles and tactics of “networked feminisms” (MacDonald et al. Citation2021) have unfolded in various contexts over the past years.

There has recently been an unprecedented rise in misogynist, anti-queer, and anti-feminist men’s rights activist (MRA) online groups and pages on Iranian social media platforms (Sama Khosravi Ooryad Citation2023). Telegram channels and Instagram pages have attracted a widespread online audience of traditional and conservative Farsi-speaking men. Iranian state-sponsored trolls (Simin Kargar and Adrian Rauchfleisch Citation2019) also support their longevity and even propagate their activism. Their strategies and tactics of organizing and visually manifesting hate toward women and non-binary bodies are broadly aligned with the global trends of MRA groups and subcultures. This phenomenon has led to an increasingly strong global mediated pact that manifests mostly in global “memetic alliances” among these subcultural and organized digital microfascisms (Khosravi Ooryad Citation2023; Bratich Citation2022). Such tactics range from inundating social media with misogynist memes to threatening, mass reporting, and systematically trolling popular Iranian feminist figures. Their “eliminationist” justification for anti-feminist activism reflects the global MRA misogynistic discourses of “injury” and the characterization of feminists as liars and monsters who must be eliminated (Banet-Weiser Citation2018; Euisol Jeong and Jieun Lee Citation2018; Massanari and Chess Citation2018; Bratich Citation2022).

Such misogynistic and queerphobic discourses manifest most forcefully in what Banet-Weiser (Citation2018, 35) calls “networked misogyny,” which implies that patriarchy must be understood in its multiplicity and complexity, and it no longer operates only through “discrete group of organizations, or roles, or spaces” but is “networked” and expressed through various mediated and interconnected ways. In parallel with the emergence of the Farsi Manosphere (Khosravi Ooryad Citation2023) and its coordinated and “networked misogyny” (Sarah Banet-Weiser and Kate M. Miltner Citation2016) on Iranian social media, there has been an ongoing, burgeoning, and understudied kind of digital feminist activism attempting to respond to the overt anti-feminism. This mode of feminist activism has assumed two main forms: first, the activism of individual feminist public figures who campaign on social media with accounts that have thousands of followers; second, the activism of anonymous or collective-based feminist pages that do not revolve around a particular figure but instead seek to create a digital feminist community to anonymously resist anti-feminist and patriarchal discourses on Iranian social media. The latter is the focus of this article. While it is difficult to precisely measure the success of the multivarious forms of digital activism on Iranian social media, it is nonetheless important to highlight the ongoing efforts of these accounts and pages to cultivate spaces of resistance (Selin Çagatay, Mia Liinason and Olga Sasunkevich Citation2022) through networked feminist digital activism.

In recent years, the dominance and excessive visibility of popular feminist figures on Iranian social media have undeniably grown alongside global manifestations of popular feminism. As Banet-Weiser (Citation2018, 37) has demonstrated, the self-oriented spectacular visibility of “popular feminism has been in large part about making what is hidden, routinized, and normalized about popular misogyny more public, displayed, and explicit.” The gesture of “making visible” is crucial for understanding how the political and patriarchal underpinnings of otherwise normalized invisible discourses function. Iranian manifestations of popular feminism consist of mediated, contested campaigns and individualized acts and performances that seek to attain recognition of their suffering and the injustices women face in Iran (Sara Tafakori Citation2021). However, I assert that such forms of popular feminist activisms and strategies on Iranian social media often direct an excessive amount of attention and credit to individual (public) figures—most of whom reside outside of Iran and have numerous privileges and access to resources—consequently overshadowing and further marginalizing other forms of less visible but decades-long grassroots activism.

These forms of popular feminism reflect the focus on “individualism and entrepreneurialism” that dominates our contemporary mediascape; nevertheless, I echo the claim that we can still envision a “different feminist politics” (Sarah Banet-Weiser, Rosalind Gill and Catherine Rottenberg Citation2020), hopeful manifestations of which include the new forms of collective feminist activism in Iran and around the world (Jinsook Kim Citation2021; Verso Books Citation2018; Wiens Citation2021; Sama Khosravi Ooryad Citation2022). Regarding Iranian feminist activism in the past decades, it is imperative to explicate the absolute atrocities that have been imposed on individual feminist and socialist activists, both within Iran and in the diaspora, who are active online using their own names and identities.

As its central focus, this article emphasizes the visual, collective, and anonymous conceptions of digital feminism—especially in restrictive and violent contexts and contested terrains, such as that of Iran—that have received less attention in research. Anonymity is crucial for continuing resistances within the violent context of Iran, where feminist and social activists are at constant risk of harassment, arrest, and imprisonment. Notably, following the (trans)national spark of extraordinary feminist revolts in the aftermath of the state murder of a Kurdish-Iranian woman, Jina Amini, numerous anonymous individuals performed collective acts of online and offline protest in affective, solidaristic ways that were inspired by one another’s acts (L Citation2022). The ongoing political violence directed at women and marginalized bodies in Iran requires such innovative tactics to counter violence and continue the resistance.

In my analysis of the memes below, I highlight the continuation of anonymous and mediated features of such performances in (Iranian) mediated spaces as both emerging and important aesthetic tools for digital feminist activism in this context. Feminist activists around the world have strategically employed anonymity to sustain their activism under suppressive states. For instance, in the 2019 women’s rights march in Istanbul, “anonymous visibility” offered a way to safely, temporarily, and strategically unite feminists (Çagatay, Liinason, and Sasunkevich Citation2022, 220). The interconnected and interdependent characteristics of anonymity and collectivity within emerging feminist activisms, such as the transnational performances of Las Tesis (Mia Liinason Citation2023), are key to the potential of anon-visual (digital) activism to move beyond dominant forms of popular feminism.

In the following sections, I first contextualize feminist theories on memes, trolling, and humor and unpack the collectivity and world-building aspects of what I call “meme-feminism.” I then discursively and conceptually analyze a selection of memes from the pages @women_memes1 and @zanan_memes to explore several aspects of such “meme-feminism” on Farsi Instagram and Telegram. By adopting an intersectional lens to investigate this growing phenomenon, I focus on the aesthetics, world-making, and affective qualities of such activism as well as its potential to visually engage with debates on social reproduction theory. I also examine the significance of the memes in terms of their depiction of the broader socioeconomic situation in Iran. Finally, I attend to the limitations and potentials of this emerging phenomenon in effectively mobilizing grassroots actions toward the material structural changes needed to fight the nation’s religio-capitalist-heteropatriarchy.

Internet memes and feminist (re-)appropriation: theoretical and methodological settings

In this article, I think with and build upon Jessica Ringrose and Emilie Lawrence’s (Citation2018) and Carrie A Rentschler and Samantha C Thrift’s (Citation2015) theorizations of “doing feminism in the network” and “feminist politics of humor” as well as Jeong and Lee’s (Citation2018) and Whitney Phillips (Citation2015) notions of “mirroring misogyny” and “trolling back.” With these concepts, I explore the emerging meme-feminism in Iran as a significant case beyond the Western (anglophone) digital context that exposes the absurdities and violence of systemic misogyny and anti-feminism online. Moreover, I follow Banet-Weiser’s (Citation2018) idea of “populist feminism,” which explains the increasingly need for forces and tactics that are “populist,” in the sense of doing feminism for broader groups, to counter the escalating, heavily mediated “networked misogyny” through collective activisms and structural critique (Banet-Weiser, Gill, and Rottenberg Citation2020, 19). I argue that this form of populist feminism has been partly mobilized through the visual mobilization of feminist memes, some of which are examined in this article. Here, the elements of these memes that are humorous and accessible to the broader public support a critique of the blatant anti-feminism and structural misogyny in the country.

The enactment of humor through internet meme cultures and its adoption by feminist online networks have been subjects of ongoing scholarly debate among feminist media scholars (e.g., Limor Shifman and Dafna Lemish Citation2010; Phillips Citation2015; Jessica Drakett, Bridgette Rickett, Katy Day and Kate Milnes Citation2018; Jenny Sundèn and Susanna Paasonen Citation2020). Humor provides feminist digital activists with a tool to prepare for moments of being a “spoilsport” (Sara Ahmed Citation2010, 581). In this regard, Ringrose and Lawrence (Citation2018, 687–688) have considered the example of “visual memetic expressions of feminist humor” on Tumblr, which included feminist memes mocking the absurd claim by MRAs that women are “man-hating.” Additionally, in an examination of memes about the viral and memetic event of the “binder full of women” in the US, Rentschler and Thrift (Citation2015, 331) have theorized “the affective, technological and cultural politics of digital feminisms and their contemporary modes of action” (351). Adrienne L Massanari (Citation2019, 31) has similarly suggested that new media tools such as “memes, reaction GIFs, and tweets can serve to coalesce sentiment and do the everyday, affective work of feminism.”

In addition to feminist humor, the tactic of “trolling back” offers another approach to combat the escalating misogyny online. In the North American context, Phillips (Citation2015, 160) has suggested that “trolling trolls” could be an effective “countertrolling” strategy. Such “feminist trolling” is a means of “strategic intelligence gathering:” the feminist digital activists allow the “bigots [to] keep talking,” thereby revealing their own mischievous behavior (164). In this way, the potential of trolling as a feminist strategy is based not on “unsympathetic laughter” but rather a “shared sense of communal laughter that is ambiguous only in its celebration of the grotesque” (Massanari Citation2019, 32) and the absurdity of systematic misogyny. Likewise, the South Korean online feminist group Megalia has devised the specific strategy of “mirroring misogyny,” which copies the language and dialect of online misogynistic trolls and could have its own contested consequences but first and foremost “reveals how bizarre the original [act of online sexism] was” (Jeong and Lee Citation2018, 708).

With few exceptions, feminist humor and visual tactics enacted through internet memes have focused largely on Western and anglophone digital spheres. Beyond such contexts, and alongside this trajectory, I build on the above-mentioned feminist theorizations of internet memes as well as feminist humor and trolling strategies to introduce and develop the concept of “memeing back” and examine it on Iranian social media. I illustrate how this humorous, image-based (anti-)trolling strategy adopts and re-appropriates contextual visual material via techniques of “recombination” (Voigts Citation2017) to allow feminists to utilize it to expose the absurdities of anti-feminist rhetoric and sentiments. It mainly follows the “trolling back” strategy identified by Phillips, but it does so exclusively through the medium of satirical memes. The core visual tactic of “memeing back” arguably distinguishes it as a unique form of humor and unprecedented strategy for challenging anti-feminism and misogyny on Iranian social media. As detailed below, the presence of localized visual elements (e.g., the figure of the Iranian Biscuit mother) or global pop-cultural icons (e.g., Spider-Man) makes the humor of these memes accessible and visually relatable to a broader audience.

Crucially, my analysis also builds on Bell Hooks’s (Citation1989) concept of “talking back,” thus adding a feminist visual dimension to this semantic tactic that makes it more pertinent to our contemporary media ecology. Hooks (Citation1989, 15) has insisted that “talking back” is “a form of conscious [rebellion] against dominating authority.” In emphasizing a shift from silence to speech, both Hooks (Citation1989, 29) and Audre Lorde (Citation1984) have stressed the power of speech for the exploited, oppressed, and voiceless to reclaim their voices and be liberated. “talking back” is, according to Hooks (Citation1989, 27), a powerful “act of resistance, a political gesture that challenges politics of domination.” Following this gesture, I argue that my term “memeing back” extends “talking back” in political and resistant ways as a mode of resisting violent domination and forms of power by innovatively and visually responding to gendered hate online.

Moreover, I argue that “memeing back” involves intentional anonymity and is not a reactionary or passive response to systemic or everyday misogyny. On the contrary, it uses its collective, globally, and locally shared imaginaries to mobilize a politics of exposure of the absurdity of both Manospheric gendered hate and the broader patriarchal issues in Iran and beyond. Here, I draw from Thomas Hobson and Kaajal Modi’s (Citation2019, 336) analysis of Fully Automated Luxury Communism (FALC) memes and their argument that online political memes are “sites of collective meaning-making” and “world-making” with potentialities for “shaping discourse, guiding action and uniting communities.” Accordingly, I argue that the community orientation of meme-making, its feminist aesthetic re-appropriations, and the strategic anonymity of meme pages such as @women_memes1 under the heavily restricted and controlled spaces of Iranian social media offer important insight into the “political and utopian imaginaries” (Hobson and Modi Citation2019, 347) of such efforts—imaginaries that tactically and aesthetically evidence the political and feminist significance of online memes as new sites of both mediated interactions and radically utopic and potentially emancipatory mobilizations.

In this study, I draw from my ongoing digital ethnographic research on selected channels and pages on Iranian social media and the memes published and circulated therein. I specifically focus on the activities of the Telegram and Instagram pages @zanan_memes and @women_memes1 between January 2021 and May 2022. During this period, @zanan_memes posted a total of 178 memes before it was allegedly mass reported by anti-feminists and Iranian Cyber Army hackers. However, the admins regained control of the pages and continued to post memes. All of the memes and pages examined from this period are publicly available, and both pages are run anonymously. Since the total number of memes is relatively small, I conduct a visual and critical analysis of “exemplar” memes (Ringrose and Lawrence Citation2018) that I selected according to their current themes and visual figures.

Ultimately, I base my analysis on two dominant themes that allow for unpacking and clarifying the concept of “memeing back”: (1) the use of humor and irony through a mixture of Farsi captions and memetic figures as well as the (re-)appropriation of pop cultural cartoonish meme templates to mobilize a world-making feminist aesthetic intervention; and (2) the highlighting of state-sponsored socioeconomic injustices in Iran to expose the absurdities of anti-feminist rhetoric and arguments through memes that focus on topics such as wage gaps and housework. For the second theme, I theoretically draw from Silvia Federici’s (Citation2012) work on social reproduction theory, which is politically embedded in long-standing grassroots movements whose political agenda of structural transformation centers women’s labor in both the household and the broader society. I expand on Federici’s work to show how emerging meme cultures and feminist reworkings of it are challenging and exposing the largely feminized household labor in Iran.

These interconnected themes are explained further in the following sections through the mapping of the exemplar memes. With such “selective mapping” (Ringrose and Lawrence Citation2018, 214), I unpack how the Iranian version of “meme-feminism” is affectively cultivated by the visual memetic utilization of “irony and wit to expose inequality” in unique tactics and practices that are contextually distinct yet connect with a global audience by means of globally shared visual vernaculars.

In line with the term “memeing back,” I also argue that the audience of the memes is not necessarily men in the Iranian Manosphere, and memes of such tacticality do not have to directly respond to any anti-feminist rhetoric. Rather, there are indications that the “memeing back” tactic aims to engage women and feminists on Iranian social media.

“Memeing back:” exposing the absurdity of the Farsi Manosphere through the affectivity of feminist visual fun

To determine what “memeing back” visually exposes or responds to in the Iranian context, we must consider how anti-feminists and members of the emerging Iranian Manosphere have frequently cited Mehrieh and “compulsory military service” for men as evidence in their posts and arguments promoting hatred of feminists—yet, they have neglected the numerous structural and state-sponsored patriarchal privileges afforded to (cis-)male individuals in Iran. To effectively grasp the working of (anti-)feminist memes produced and circulated on Farsi Instagram and Telegram, one must first understand the anti-feminist discourses that are mobilized under the guise of “male victimhood” (Kate Manne Citation2018) in these mediated spaces. Among the many issues that anti-feminist MRA groups mobilize on Iranian social media to attack or blame feminists, Mehriah and compulsory military service for men are the most notable.

Mehrieh is an agreed-upon monetary payment of gold coins given to a bride by the groom or his father upon marriage. The exact value is specified in the marriage contract when a couple expresses their desire to marry in Iran. There has been ongoing debate about the objectifying nature of such agreement, and feminist activists in Iran have long protested the inequality of marriage contracts and their terms as well as the lack of legal support for women in seeking divorce and even in trying to fully claim their Mehrieh payment (Azadeh Davachi Citation2015). Despite the complexities and problematics of this law, Iranian MRAs and coordinated anti-feminists have not targeted the system that issues such laws in the first place; instead, they have mobilized the Mehrieh discourse to reorient attention away from this unjust system and toward the “feminists” who they believe are fully at fault. To this end, they have propagated misogynistic memes and clips across Telegram and Instagram and promoted offline activities, such as gatherings in front of the parliament in Tehran to protest feminists who they claim put men in jail in Iran for not paying Mehrieh (Isna Citation2021).

The second topic that is a common focus of these groups and their anti-feminist arguments is the compulsory military service for men in Iran. The MRA channels have dedicated pages and chatrooms for discussing this topic and advancing a discourse of “male victimhood,” as Manne (Citation2018) has argued. Such discourse supports their claims of being deeply discriminated against in Iran and of feminists and their “false accusations of sexual assault, their love for gold, and laziness” being to blame for it.

The @women_memes1 page has devoted a considerable portion of its meme production to addressing the absurdity of these arguments, which have been the most frequent and visible on social media. The memes posted by @women_memes1 employ “memeing back” as a tactic of exposure that adopts an affective feminist politics of humor (Rentschler and Thrift Citation2015) and re-appropriation to challenge systemic and coordinated misogyny through online tools in the Iranian context. Such tactic not only exposes the absurdity of anti-feminist arguments that blame women and feminists for such laws but also highlights patriarchal and social injustices in Iran through the visual medium of memes (see and ).

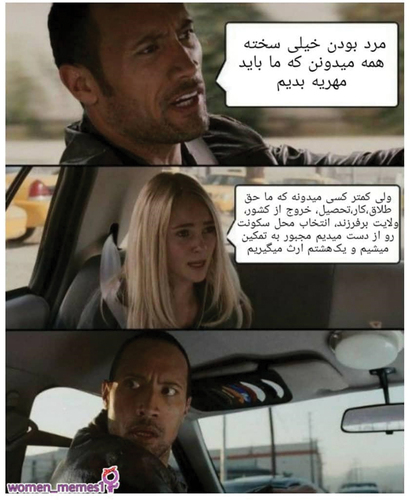

Figure 1. The meme parodying the anti-feminists’ argument on having to pay Mehrieh with the woman providing a list of what rights women do not have in Iran.

The “annoyed bird” meme template in is used to explain how the bird—here, an Iranian feminist trying to talk about women’s issues in Iran—is overshadowed by a shouting crow, who keeps saying, “we pay Mehrieh, we do compulsory military service, etc.” The “annoyed bird” meme features a four-panel image of a bird whose voice is obstructed by a large shouting crow (Know Your Meme Citation2016). The template is adapted from a webcomic series. With this template, the Farsi version of the meme seeks to indicate indirectly how the crow (i.e., anti-feminist MRA groups) overshadows and deliberately ignores women’s numerous problems in Iran by shouting repetitively about the issues that it considers to be the most pressing for (cis-)men in Iran.

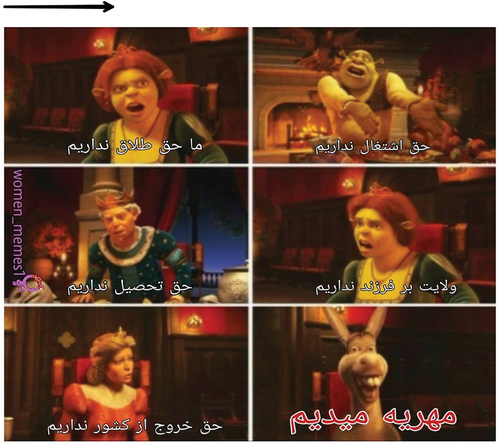

In another example, the “Shrek, Fiona, Harold, Donkey” meme adapts and remixes popular characters from the animated media franchise Shrek. displays this meme template with Farsi captions conveying a dialogue. First, Fiona angrily says that we (Iranian women) do not have the right to divorce. Next, Shrek states that we (Iranian women) do not have (equal) wage rights. Fiona and Harold then complain that we (Iranian women) cannot study and travel abroad or claim custody of our children without the permission of the husband or father. In the last panel, the smiling donkey character—representing Iranian husbands (or even MRAs)—concludes, “[but] we pay Mehrieh!”

Figure 3. The meme is making fun of how in all situations, the only argument against women’s unequal rights in Iran is that men (cis) pay Mehrieh.

At first glance, the “Shrek, Fiona, Harold, Donkey” meme seems merely another adaptation of this meme template, which has received numerous captions from around the world. While the meme genre itself has become a new form of pop culture (Marcel Danesi Citation2019), the layers of transmedia storytelling (Henry Jenkins Citation2003) of memes make sense to those who either share global knowledge of the (visual) message of the meme or are situated in the local context that the meaning of the meme addresses. The content of the meme in highlights feminist reworkings of the fairy tale genre to show how Fiona is deviant and engages in “unapologetically unprincessy” behavior (Amber Leab Citation2011), such as nagging, burping, and eating rats, thus subverting “established notions of feminine desirability” in this animation.

In addition, the technique of “recombinant appropriation” (Voigts Citation2017, 287) makes it possible for viral memes to be adapted to new contexts via circulation and remodeling. They can also become “aesthetically important” through “transform[ing] the textuality of cultural production”—in as much as they transform it politically by “seeking to replace the power imbalance between cultural producers and audience by models of circulation.” In further discussing the notion of “recombinant appropriation,” Voigts (Citation2017, 290) has recounted the ways in which such technique works through contemporary cultural products, such as internet memes, some of which tend to be “hybrid, derivative, parasitic, critical, comic, playful, transgressive, humorous, […].” I believe that such humorous hybridity, when coupled with the “feminist politics of [visual] fun” (Ringrose and Lawrence Citation2018) and global shared knowledge of the subversive appropriation of pop cultural figures, could create a transgressive potential for feminist memes to challenge power structures with available mediated tools. Such potential manifests in the “Shrek, Fiona, Harold, Donkey” meme, which combines a pop-cultural element with the contextualized notion of Mehrieh in a visual-discursive manner. The audience of the meme, which is mostly women and feminists who see and like the memes on Instagram, can immediately recognize the visual fun by looking at both the characters and the captions that are playfully rendered together. As the main audience, women in Iran can most easily recognize the visual fun of such memes, particularly in their challenge of structural inequalities. These women know better than anyone that utilizing the anti-feminist discourse on Mehrieh to prove the Iranian version of “male victimhood” is just an absurdly funny rhetoric in a society that denies almost all rights and freedoms to women, which fits with the visuality that the funny donkey embodies in the meme.

In and , this subversive appropriation entails the use of fictional visual characters from a webcomic and an animated series with the addition of original parodic textuality specific to the Iranian social media context to mobilize a visual aesthetics and textual intervention into the dominant narratives embedded in anti-feminist rhetoric in Iran. By depicting the large crow, the nagging Fiona and Shrek, and the “funny donkey” echoing the Mehrieh and compulsory military service talking points of Iranian MRA groups, these Farsi feminist memes achieve a potentially subversive manifestation of such feminist “recombinant appropriation” visually remixing and humorously capturing elements of misogynistic discourse to undermine that very discourse.

Thus, the concept of “memeing back” describes this technique of innovatively challenging numerous inequalities against women—here, in Iran—by employing contextual humor and the rhetoric of misogyny to discredit ludicrous anti-feminist arguments online. Following Margaret Wetherell’s (Citation2012, 13, 145) account of “affective practices” as continually flowing and emerging at multiple surfaces and levels, I argue that an affective form of visual satire is mobilized online against explicitly state-sponsored misogyny in the Iranian context through the remixing and re-appropriating of global viral templates and pop cultural figures. Despite the ongoing violence in the everyday lives of marginalized bodies in Iran and similar contexts, such visual affectivity offers a “therapeutic element” (Ringrose and Lawrence Citation2018, 218) for the viewer or intended audience. Instead of simply expressing frustration at persisting inequalities, the elements of (dark) humor and absurd fun are affectively and memetically utilized to criticize injustices without necessarily conveying a one-dimensional approach to women’s issues in Iran.

The feminist tactic of “absurd laughter” has been similarly performed and observed in the Nordic context. Sundèn and Paasonen (Citation2020) have argued for multivarious manifestations of such absurdity and its reclamations through affective feminist tactics that engage parody, irony, ridicule, and other rhetorical tools—seen, for instance, in the figure of the “shameless hag”—or by becoming an unruly female spectacle in a male-dominated setting. I see the “memeing back” tactic in the Iranian context as a similar continuation of such reclamations of absurd laughter and humor, particularly since it can visually activate multiple affects—from rage and ridicule to laughter and playfulness—in an audience that has experienced life under a gender apartheid regime that seeks only to infuse sadness, frustration, and hopelessness into society.

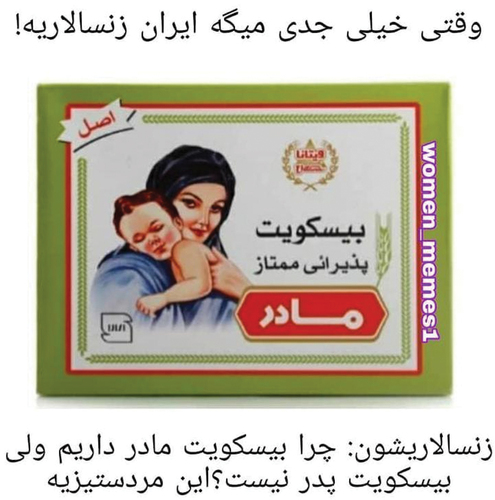

The “memeing back” strategy incorporates localized popular culture, imagery, and language to ridicule the logic of misandry within the rising Iranian Manosphere. For instance, displays an image of a popular Iranian biscuit brand, Mother, with the caption, “Why don’t we have a biscuit named father? This is misandry!” By applying the logic of Iranian anti-feminists, which constantly ignores systemic inequalities against women and other marginalized people in Iran in favor of blurring complexities by focusing on surface-level labels, the “memeing back” tactic mocks the sheer absurdity of such logics while embodying a mode of “feminist [visual] trolling” to contextually respond to these baseless arguments.

Memeing back at systemic socioeconomic inequalities against women in Iran: visual nagging and satirical re-appropriating

Another element that strongly characterizes these emerging Farsi feminist memes is the satirical depiction of inequalities that affect women in Iran with respect to wages, housework, and other socioeconomic aspects. In the Global Gender Gap Report 2022, Iran is among the three countries with the largest gender gap (World Economic Forum Citation2022). While women comprise the majority of university graduates in Iran, their actual participation and employability after graduation is very low (Human Rights Watch Citation2017). Women are being increasingly limited to the roles of housewives and “sacred” mothers who are expected to perform unpaid labor to enable the traditional family to thrive.

The socioeconomic crises in Iran due to state corruption and mass suppression (Amnesty International Citation2023) and the privatization of multiple sectors have indeed impacted all individuals and communities in Iran regardless of age, ethnicity, or gender. However, the impact of these crises and systemic inequalities has disproportionately affected women, sexual minorities, ethnic minorities, and the working class, all of whom have been revolting against such socioeconomic suppressions (Frieda Afary Citation2023). In addition, the gender segregation laws and policies issued by the Islamic regime in Iran have long restricted the access of women to many public places and activities (Leila Mouri Citation2014). These unjust laws have fueled the infamous gender apartheid in Iran for decades.

Many Iranian feminist activists have long objected to these unjust laws, campaigned to change them, and continually critiqued these inequalities in public online/offline spaces (Tafakori Citation2021; Khosravi Ooryad Citation2022). I argue that the emerging Farsi meme-feminism is a direct extension of both feminist struggles from the past decades and the fight to enter the realm of the digital and visual vernacular by making visible these inequalities in satirical and innovative ways. These novel techniques are not so novel in other contexts, such as the humorous Reddit community TrollX, which uses humor and feminist trolling to oppose the online aggression and material inequalities that women face in the US (Massanari Citation2019), and the South Korean parody community of Megalia (Jeong and Lee Citation2018).

In criticizing the wage and gender pay gap as well as other structural and everyday inequalities in the Iranian context, the novelty of meme-feminism and the “memeing back” tactic is that, instead of reactively trolling specific groups or individuals, it adopts the long-established stereotype of the “nagging woman.” This tactic utilizes the visuality of the medium of memes to create a series of what I call “visual nagging” that satirically “exposes” the absurdity of the logics deployed by advocates of unequal laws. Through this exposure, it “reclaims” and “reappropriates” stereotypical characteristics of women in mediated spaces to challenge the systemic socioeconomic inequalities that harm them.

In theorizing about feminists as “willful women,” Sara Ahmed (Citation2014) has discussed how anti-feminist and sexist discourses continually portray women in a certain way, and “[w]omen are already heard in this way, as complaining, moaning, whinging.” By not accepting these stereotypes, Ahmed (Citation2014) has argued, women become “willful women,” as “these are willful assignments; given to those who are not willing to accept how they are assigned.” Through their rejection of this violent depiction of them, these “willful women” refuse to be seen as such, and they resist by continuing that refusal. Here, I build upon Ahmed’s theory and hooks’s (Citation1989) notion of “talking back” at dominant authority to argue that the satirical adoption and representation of “assigned roles” by the individuals they impact (i.e., women and marginalized bodies) is also a willful act of reclaiming and resisting.

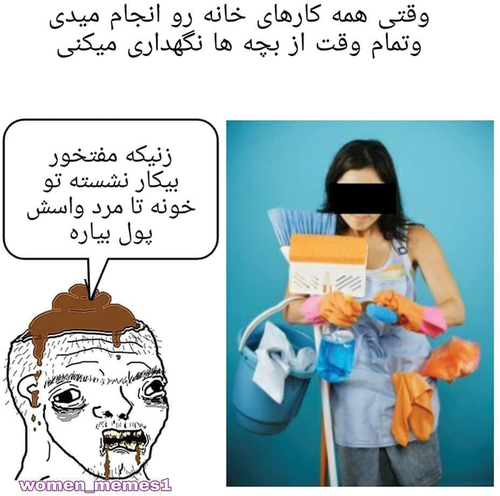

presents one example of such willful talking back. In this meme, Wojak embodies the MRA rhetoric by taunting the housewife mother for being a lazy woman who sits idly at home and waits for her man to bring money for her. In the top caption, the housewife complains with a nagging expression that a mother and housewife does all of the housework and full-time childcare. In this scene of debate between a “moaning woman” and the MRA Wojak, this meme visually juxtaposes the two figures and arguments and is captioned in a way that ascribes the “moaning” stereotype to the woman while exposing the “complaining idiocy” of the Wojak-man character. Thus, the depictions and captions in the meme are a form of “visually nagging” and willfully critiquing the domestic labor historically imposed on women. The meme does not depict the woman rebelling against the household workload or attending a demonstration; instead, it intentionally visually depicts the reality of many women under the current capitalist patriarchy: holding all of the household cleaning materials while nagging. Thereby, it attempts to memetically and satirically visualize the experience of a wageless mother working full-time as a housewife at home while still receiving misogynistic comments about her idleness. While not fully embodying a willful character or explicitly resisting misogynist stereotypes, the “nag” figure in these memes exposes the inequality of laws against women in Iran, particularly regarding wages and household labor. At the same time, it embodies and reclaims the nagging cliché specifically to critique the broader structural injustices that devalue women’s labor in this context. In this regard, I assert that the nagging character in memes such as the one in features elements of both visual nagging and willfully talking back at the Manospheric taunting of Iranian women and mothers as “lazy.”

As Federici (Citation2012, 96) has stated, “domestic work is considered by many to be women’s natural vocation, so much so that it is often labeled ‘women’s labor.’” This label has historically served capitalist and patriarchal institutions, governments, and discourses that have constructed the figure of the “full-time housewife” through “a complex process of social engineering that in a few decades [–] removed women—especially mothers—from the factories, substantially increased male workers’ wages, enough to support a “nonworking” housewife.” Similar social engineering processes have been undertaken in modern Iran in both the pre- and post-revolutionary periods. In the Pahlavi era, the role of the mother as a housewife and child bearer was exalted to encourage traditional family roles (Firoozeh Kashani-Sabet Citation2011). In the post-revolutionary era, the mythical figure of the sacrificial or martyr’s mother has been at the core of fundamentalist “nation-building discourses” (Khosravi Ooryad Citation2022). Hence, in Iran, the wageless domestic labor of mothers and wives has been largely naturalized as an assumed dutyFootnote1 carried out by these women, and housework is equated to the “natural vocation” of women in service of the state.

In accordance with my analysis of the visual nagging tactic in memes, Federici (Citation2012) has highlighted the “nagging” embedded in discourses that depict or reduce the struggle of women against wageless housework. Such violent manipulation through reduction has not only been historically “imposed on women, but it has been transformed into a natural attribute of [her] female physique and personality, an internal need, an aspiration, supposedly coming from the depth of [the] female character” (Federici Citation2012, 16). When women confront and oppose this assumption, they are seen as “nagging bitches, not as workers in struggle” (160).

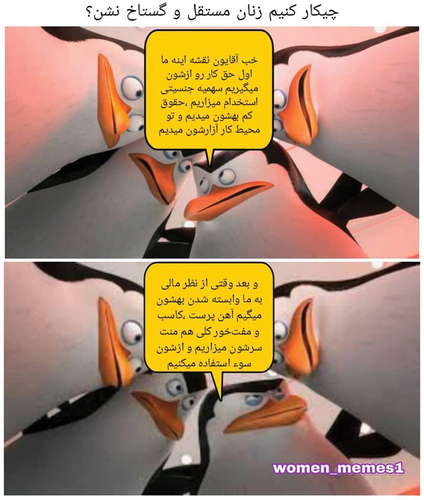

I argue that the “nagging bitches” in the memes analyzed here perform this visual nagging to “meme back” at systemic inequalities through a visual politics of exposure. The memes politically and satirically visualize the “institutionalization of an unequal division of power that has disciplined [women] as well as men” (Federici Citation2012, 33). In , for instance, the visual nagging tactic manifests in the “Spider-Man pointing at Spider-Man” meme, where all three Spider-Man characters are pointing at each other. Through its captions, this meme illustrates the vicious circle that exists for Iranian women who struggle to find jobs outside of the home: one Spider-Man echoes the male discourse in Iran, telling women to work and have jobs if they want equality; another Spider-Man impersonates women, requesting wage equality; and the final Spider-Man represents an employer, stating that he only hires male (cis) employees. Similarly, in , the penguin cartoon characters in the meme are portrayed as men who are plotting to deny women jobs, harass them, exclude them from public arenas, and then call them idle and dependent on their husbands’ money. The fact that both of these memes feature male characters who are either perpetuating a recursive situation or plotting an event reflects the satirical ways in which visual nagging as a critique is at play within these memes.

Figure 6. Spider-man meme exposing gendered wage inequality in Iran.

The adoption of cartoonish (male) characters from popular viral memes is, I argue, a tactical, mediated way of not only utilizing popular culture to raise awareness of systemic inequalities regarding housework and the gender pay gap in Iran but also ironically transferring the critical visual message that, in such a vicious cycle, women have no power whatsoever and are constantly absent from the debates, lawmaking procedures, and policies. Specifically, the Spider-Man characters, who embody the unfair stipulations for women’s employability in Iran, are visually the kind of cartoonish figures that are reappropriated to critique the very unequal laws and demands.

The template of the Spider-Man pointing meme, which was first spread within the Black hip-hop Twitter community in the mid-2010s (Know Your Meme Citation2011), has produced numerous impersonations and digital embodiments. From Black Twitter to the emerging Farsi meme-feminism on Instagram, the embedded and embodied circulatory aspect of memes further evidences the “potential of online memes to act as sites of intersubjective imagination and world building” (Hobson and Modi Citation2019, 330). In the context of a disastrously large gender pay gap, a rise in globally mediated anti-feminism, and the immediate targeting of feminists for arrest and harassment, it seems apt to rethink our ways of resistance and accept Hobson and Modi’s (Citation2019, 337) claim that “[o]ur memes of production [are] important sites of political imagination [which] represent important opportunities to rethink our means of production.” In this regard, I assert that “memeing back,” which is embodied here by the nagging figure in the Farsi feminist adaptation of the Spider-Man meme, arguably creates an “intersubjective worldbuilding site” for willfully responding via memetic exposure to one of the most notorious manifestations of capitalist patriarchy—the gender pay gap—and the exploitation of women’s labor in Iran and beyond.

Conclusion

In this article, I have analyzed the meme-feminism emerging on Iranian social media to combat systemic and coordinated hatred and misogyny online. I have conceptualized the specific tactic of “memeing back” based on examples from feminist meme pages on Farsi Instagram and Telegram. Furthermore, I have highlighted the feminist world-building practices and the community-building potential of these memes through the mobilization of anonymous captioning and aesthetic features, such as techniques of recombination, shared humorous vernaculars, and visual nagging.

Nevertheless, I partly agree with Silvia Federici (Citation2020, 11), who, in historicizing and theorizing the body in our current predicament, has warned us about naively turning to digital technology as a means of emancipating marginalized bodies while ignoring “the constraints that technologies place on our lives and their increasing use as a means of social control as well as the ecological cost of their production.” Federici’s account offers a necessary political-economic critique of the multiple oppressive and exploitative functions of digital technologies toward marginalized bodies. In view of this, a detailed political-economic analysis of doing digital feminism within such mediated terrains as that of Iran demands a separate future study. Moreover, it is important to highlight the urgent need for a detailed critical study on the online rise in transmisogynistic hatred directed against trans-queer persons on Iranian social media. Besides acknowledging such critiques of digital technologies and the political potentialities of online memes, this article has aspired to show how the emerging meme-feminism in the Iranian context offers an important contextual vision of how memes can act as political tools for structural, satirical critique of anti-feminism and the numerous socioeconomic inequalities impacting women and marginalized bodies in Iran. Crucially, the anonymity, novel aesthetic visuality, and collective nature of such meme-feminism on Iranian social media signal a remarkable political turn in doing feminist digital activism in networked and community-oriented world-building ways without centering or endangering certain figures’ (popular) activisms.

As mentioned at the beginning of this article, all sorts of activism are being severely repressed in the current violent context of Iran. Amid the burgeoning feminist revolution there, social media and memetic activism have proven to be vital to the continuation of resistance, which constitutes further potent evidence of the entanglement of digital and material struggles in hyper-filtered and massively suppressed contexts. Consequently, these meme pages and other feminist and socialist Instagram pages on Iranian social media are at constant risk of being mass reported, shadow banned, and suspended. While there is no guarantee of how long they could thrive online, the memes themselves analyzed here offer worthwhile contextual grounds for future studies on memes and aesthetic mobilizations within feminist movements, particularly those under restrictive and violent states. As I have illustrated, “memeing back” and other praxis-oriented aesthetic interventions could be deployed in other interconnected ways to support a more robust, life-affirming fight against the ever-emerging suppressive tools of offline and online hate and anti-feminism in Iran and globally—and, accordingly, to mobilize a feminist future of mediated, ongoing, on-the-ground resistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sama Khosravi-Ooryad

Sama Khosravi Ooryad is a MSCA-PhD candidate at the Department of Cultural Sciences, University of Gothenburg. Her emerging research interests span internet memes, (beyond-Western) mediated spaces, online hate cultures, feminist theory, gender & politics, and digital cultures. E-mail: xxx@xx

Notes

1. Performing this duty, under sharia law, has a specific name called Tamkin (Farsi legal term meaning compliance). Tamkin means that a married woman should keep the household together, raise children (along with the husband), not engage in works outside house that would endanger the family, and, above all, sexually attend to the husband whenever he wishes. The law states that husband is entitled/encouraged to do such duties too; in practice, however, it is mostly wives who are obliged to obey and perform such duties.

References

- Afary, Frieda. 2023. “Iranian Labor Unions Have Led Inspiring Solidarity Strikes Amid the Uprising.” Truthout, January 19. https://truthout.org/articles/iranian-labor-unions-have-led-unprecedented-solidarity-strikes-amid-the-uprising/

- Ahmed, Sara. 2010. “Killing Joy: Feminism and the History of Happiness.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 35 (3): 571–594. doi:10.1086/648513.

- Ahmed, Sara. 2014. “Feminist Complaint.” Feministkilljoys (Blog). Accessed November 25, 2022. https://feministkilljoys.com/2014/12/05/complaint/

- Amnesty International. 2023. “Iran: Shameful Anniversary Celebrations Amid Decades of Mass Killings and Cover-Ups.” February 3. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2023/02/iran-shameful-anniversary-celebrations-amid-decades-of-mass-killings-and-cover-ups/

- Banet-Weiser, Sarah. 2018. Empowered: Popular Feminism and Popular Misogyny. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Banet-Weiser, Sarah, Rosalind Gill, and Catherine Rottenberg. 2020. “Postfeminism, Popular Feminism and Neoliberal Feminism? Sarah Banet-Weiser, Rosalind Gill and Catherine Rottenberg in Conversation.” Feminist Theory 21 (1): 3–24. doi:10.1177/1464700119842555.

- Banet-Weiser, Sarah, and Kate M. Miltner. 2016. “#masculinitysofragile: Culture, Structure, and Networked Misogyny.” Feminist Media Studies 16 (1): 171–174. doi:10.1080/14680777.2016.1120490.

- Books, Verso, ed. 2018. Where Freedom Starts: Sex Power Violence #metoo. New York: Verso.

- Bratich, Jack Z. 2022. On Microfascism: Gender, War, and Death. New York: Common Notions.

- Çagatay, Selin, Mia Liinason, and Olga Sasunkevich. 2022. Feminist and LGBTI+activism Across Russia, Scandinavia and Turkey: Transnationalizing Spaces of Resistance. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Danesi, Marcel. 2019. “Memes and the Future of Pop Culture.” Brill Research Perspectives in Popular Culture 1 (1): 1–81. doi:10.1163/25894439-12340001.

- Davachi, Azadeh. 2015. “Chaleshi Ba Naam-E Mehrie-Ye zanan” [A Challenge Called women’s Dowry]. Radiozamane, October 27. https://www.radiozamaneh.com/243090/

- Drakett, Jessica, Bridgette Rickett, Katy Day, and Kate Milnes. 2018. “Old Jokes, New Media – Online Sexism and Constructions of Gender in Internet Memes.” Feminism & Psychology 28 (1): 109–127. doi:10.1177/0959353517727560.

- Federici, Silvia. 2012. Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle. Oakland: PM Press.

- Federici, Silvia. 2020. Beyond the Periphery of the Skin: Rethinking, Remaking, and Reclaiming the Body in Contemporary Capitalism. Oakland: PM Press.

- Ging, Debbie, and Siapera Eugenia, eds. 2019. Gender Hate Online: Understanding the New Anti-Feminism. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hobson, Thomas, and Kaajal Modi. 2019. “Socialist Imaginaries and Queer Futures: Memes as Sites of Collective Imagining.” In Post Memes: Seizing the Memes of Production, edited by Alfie Brown and Dan Bristow, 327–352. Earth: Punctum Books.

- Hooks, Bell. 1989. Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black. Reprint, 2015 ed. London: Routledge.

- Human Rights Watch. 2017. It’s a Men’s Club: Discrimination Against Women in Iran’s Job Market. May 25. https://www.hrw.org/report/2017/05/25/its-mens-club/discrimination-against-women-irans-job-market

- Isna. 2021. “Tajammo-E Mardan Moghabel-E majlis” [Men Demonstrating in Front of Parliament to Reduce Amount of Dowry]. October 19. https://www.isna.ir/news/1400072719457/تجمع-مردان-مقابل-مجلس-برای-کاهش-میزان-مهریه

- Jenkins, Henry. 2003. “Transmedia Storytelling: Moving Characters from Books to Films to Video Games Can Make Them Stronger and More Compelling.” MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2003/01/15/234540/transmedia-storytelling/.

- Jeong, Euisol, and Jieun Lee. 2018. “We Take the Red Pill, We Confront the DickTrix: Online Feminist Activism and the Augmentation of Gendered Realities in South Korea.” Feminist Media Studies 18 (4): 705–717. doi:10.1080/14680777.2018.1447354.

- Kargar, Simin, and Adrian Rauchfleisch. 2019. “State-Aligned Trolling in Iran and the Double-Edged Affordances of Instagram.” New Media & Society 21 (7): 1506–1527. doi:10.1177/1461444818825133.

- Kashani-Sabet, Firoozeh. 2011. Conceiving Citizens: Women and the Politics of Motherhood in Iran. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Khosravi Ooryad, Sama. 2022. “Dadkhah Mothers of Iran, from Khavaran to Aban: Digital Dadkhahi and Transnational Coalitional Mothering.” Feminist Theory 25 (1): 42–63. doi:10.1177/14647001221127144.

- Khosravi Ooryad, Sama. 2023. “Alt-Right and Authoritarian Memetic Alliances: Global Mediations of Hate within the Rising Farsi Manosphere on Iranian Social Media.” Media, Culture & Society 45 (3): 1–24. doi:10.1177/01634437221147633.

- Kim, Jinsook. 2021. “Sticky Activism: The Gangnam Station Murder Case and New Feminist Practices Against Misogyny and Femicide.” JCMS: Journal of Cinema and Media Studies 60 (4): 37–60. doi:10.1353/cj.2021.0044.

- Know Your Meme. 2011. “Spider-Man Pointing at Spider-Man.” Know Your Meme. Accessed 11 July 2023 https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/spider-man-pointing-at-spider-man

- Know Your Meme. 2016. “Annoyed Bird.” Know Your Meme. Accessed 12 July 2023. https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/annoyed-bird

- L. 2022. Figuring a women’s Revolution: Bodies Interacting with Their Images, Translated by, Alireza Doostdar. Jadaliyya. https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/44479

- Leab, Amber. 2011. “Animated children’s Films: Onion Have Layers, Ogres Have Layers—A Feminist Analysis of Shrek.” Btchflcks, November 29. https://btchflcks.com/2011/11/animated-childrens-films-onions-have-layers-ogres-have-layers-a-feminist-analysis-of-shrek.html

- Liinason, Mia. 2023. “Radicality and Revolt: Transnational Struggles, Spaces and Emergent Feminist Agendas.” Keynote address at Resisting Patriarchal Worlds, Traveling Struggles, and Feminist Networks: Transnational Solidarity with “Woman, Life, Freedom” (symposium), Lund University, Lund, Sweden.

- Lorde, Audre. 1984. “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action.” In Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, edited by Audre Lorde, 40–44. Trumansburg, NY: Crossing Press.

- Manne, Kate. 2018. Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Massanari, Adrienne L. 2019. “Come for the Period Comics. Stay for the Cultural Awareness: Reclaiming the Troll Identity Through Feminist Humor on Reddit’s/R/TrollXchromosomes.” Feminist Media Studies 19 (1): 19–37. doi:10.1080/14680777.2017.1414863.

- Massanari, Adrienne L., and Shira Chess. 2018. “Attack of the 50-Foot Social Justice Warrior: The Discursive Construction of SJW Memes as the Monstrous Feminine.” Feminist Media Studies 18 (4): 525–542. doi:10.1080/14680777.2018.1447333.

- Mouri, Leila. 2014. “Gender Segregation Violates the Rights of Women in Iran.” Iran Human Rights, September 3. https://iranhumanrights.org/2014/09/gender-segregation/

- MacDonald, Shana, Brianna I. Wiens, Michelle Macarthur, and Milena Radzikowska, eds. 2021. Networked Feminisms: Activist Assemblies and Digital Practices. London: Lexington Books.

- Phillips, Whitney. 2015. This is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things: Mapping the Relationship Between Online Trolling and Mainstream Culture. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- Rentschler, Carrie A., and Samantha C. Thrift. 2015. “Doing Feminism in the Network: Networked Laughter and the ‘Binders Full of Women’ Meme.” Feminist Theory 16 (3): 329–359. doi:10.1177/1464700115604136.

- Ringrose, Jessica, and Emilie Lawrence. 2018. “Remixing Misandry, Manspreading, and Dick Pics: Networked Feminist Humour on Tumblr.” Feminist Media Studies 18 (4): 686–704. doi:10.1080/14680777.2018.1450351.

- Shifman, Limor, and Dafna Lemish. 2010. “BETWEEN FEMINISM AND FUN(NY)MISM: Analysing Gender in Popular Internet Humour.” Information Communication & Society 13 (6): 870–891. doi:10.1080/13691180903490560.

- Sundèn, Jenny, and Susanna Paasonen. 2020. Who’s Laughing Now? Feminist Tactics in Social Media. London: The MIT Press.

- Tafakori, Sara. 2021. “Digital Feminism Beyond Nativism and Empire: Affective Territories of Recognition and Competing Claims to Suffering in Iranian Women’s Campaigns.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 47 (1): 47–80. doi:10.1086/715649.

- Vickery, Jacqueline Ryan, and Tracy Everbach, eds. 2018. Mediating Misogyny: Gender, Technology, and Harassment. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Voigts, Eckart. 2017. “Memes and Recombinant Appropriation: Remix, Mashup, Parody”. In The Oxford Handbook of Adaptation Studies, edited by Thomas Leith, 308–327. 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199331000.013.16.

- Wetherell, Margaret. 2012. Affect and Emotion: A New Social Science Understanding. London: Sage.

- World Economic Forum. 2022. Global Gender Gap Report 2022. July 13. https://www.weforum.org/reports/global-gender-gap-report-2022