ABSTRACT

Queer feminist media studies habitually overlooks how popular communications mediate same-sex sexualities beyond the global northwest. Thinking with this gap, this paper problematises mediated queerness in the Arab world. I use the case study of “alternative” music in Israeli-dominated Palestine to theorise how far (or not) Palestinian vernacular modalities constitute a politics of sexuality above and below—although not necessarily in opposition to—the master-narratives of LGBTQ+ recognition, visibility, and the individual closet that often overshadow global commodity platforms. Drawing on my twenty-eight-month ethnography on “alternative” music in Palestine, I explore how queer-identifying Palestinian musicians use music, drag, and performance videos to self-fashion gender and sexual identities, in the context of dominant, media-friendly visions of queerness on digital networks. Through close reading of Bashar Murad’s 2021 song and video, “maskhara” (mockery), and via interviews and ethnographic data, I argue that music constitutes a shifting politics of sexual (in)visibility in Palestine. Musicians move between visible and invisible queer subject positions, depending on audience, locality, and framing. Expanding the field’s focus on Anglo-American sexual representations, then, the contribution theorises mediated queer cultural worldmaking in contexts of settler-colonisation and militarised occupation.

Introduction

Over the past decade, representations of “diverse” femininities, masculinities, and sexualities have exploded onto transnational media platforms. Advertising corporations readily deploy same-sex sexualities to promote their wares across global capitalist markets. Virgin Atlantic Airlines, NatWest Banking, and the dating app Tinder, for example, all produced materials with lesbian and gay (LG)—and, to a lesser extent, bisexual, trans, and/or queer (BTQ+)—messaging in recent times. Similar trends resonate in popular cinema and television. Formats with LG (and sometimes BTQ+) characters are ever-more visible on transnational scales. Digital streaming giant, Netflix, for instance, has entire reels dedicated to films, TV shows, and documentaries centred on LG(BTQ+) plotlines. Popular music echoes similar trends. From the US to South Korea, artists increasingly foreground same-sex sexual identities in their public portfolios and social media outputs. In contrast to the violent ways in which heterosexually-dominated societies subjugate non-heteronormative communities around the world, these “alternate” gender and sexuality performances often elicit huge fan followings, especially among young people connected via digital ecologies like TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube. Media-friendly LG(BTQ+) formations, it would thus appear, today seem welcome across for-profit networks of consumption and exchange.

It is without doubt that the amplification of some–usually only—LG people in mediated spaces from which we have historically been excluded is significant: a point frequently reiterated in the mainstream media. In such arenas, the recognition of gender and sexual “diversity,” across wide-reaching cultural ecosystems, is taken to indicate that previously ostracised communities are now “free” to participate in public life around the globe. Through this lens, representing proud, happy, and modern gays living “outside” of their individual closets, and under the light of the (formerly hostile) liberal state, is celebratory evidence of a nation’s “progress” on sexual “empowerment,” albeit limited to lesbians and gays. Such frames thus funnel LG liberation through the epistemes of identity politics, visibility, and rights-based assimilation into the newly-homonational body politic (Lisa Duggan Citation2002).

However, the assumption that illuminating “diversity” leads to linear progress fosters its own problematics. When platform economies render some same-sex sexualities visible in their global circuits of exchange, other, perhaps anti-normative positionalities necessarily become less visible. This disappears same-sex desiring selves who do not seek cultural luminosity on singularly LG(BTQ+) grounds. And constitutes an individuating politics of sexuality through the metaphor of the closet, whereby homophobia forms the primary axis of an individual’s oppression. The mediated inclusion of some - largely white, middle-class, respectable, and “western” – LG(BTQ+) subjects in global media and communications thus raises important intersectional questions about whom such outlets deem worthy of visibility, as well as the terms through which it is afforded, in transnationally-networked, media saturated environments. Indeed, as the vicious cultural-judicial backlash against trans and non-binary communities in UK/US contexts indicate, there are clear institutional limits to such “inclusive” media discourses.

In this article, I approach queer (in)visibilities and cultural mediation differently. I question how, if at all, cultural representations connected to, but separate from, the advanced capitalist societies of the global northwest engage the hegemonic sexual imaginaries that dominate commodity platforms. I explore the ways in which queer-identifying actors use popular culture to self-fashion their lives and experiences in contexts usually ignored in the communication channels highlighted above: the Middle East’s Arab-majority countries. Using the case study of “alternative” music in Israeli-dominated Palestine, I theorise how far (or not) Palestinian vernacular modalities constitute a politics of sexuality above and below—although not necessarily in opposition to—the master narratives of LG(BTQ+) recognition, visibility, and the individual closet fetishized in the global media.

My argument draws on my twenty-eight-month ethnography on the gender and sexual politics of subcultural music in Palestine (Ramallah, Haifa, Jerusalem) and its diaspora (Amman, London), conducted between 2012 and 2018. Through this data, and in critical dialogue with queer feminist media research, I trace the potentials and pitfalls of visual illumination for sexual and gender justice in the case of Palestine: a political economic context shaped by neoliberal globalisation, Israeli settler-colonisation, and Palestinian statelessness.

Overall, I contend that queer media in Palestine cultivates shifting sexual (in)visibilities as it circulates through different chains of mediatised signification. On one hand, cultural performances engage global-liberal narrativizations of LG identity, while on the other they reconfigure some of the underlying assumptions on which such accounts are based. Cultural production and mediatory practices are therefore important objects of analysis because they forge sites where normative discourses on gender and sexual politics are ruptured and repaired—especially when viewed through transnational lenses.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. First, I outline my entry points, and review the debates about mediated sexualities that animate the piece. Second, I map gender and sexuality in colonised Palestine. I outline what is at stake when the individuating “closet” model is used to theorise queer desire and homophobic oppression under settler domination and militarised violence. Third, I outline my methodological framework, introduce my case study, and situate my positionality in Palestine. Fourth, I discuss my findings. I argue that music expresses and represses different gender and sexual affects. Fifth, and finally, I map my conclusions, and summarise the contributions the paper makes to queer feminist research on mediated sexualities in the twenty-first century.

Mediating queer (in)visibilities in media and popular culture

Critical work in queer feminist communications problematises the notion that media illumination engenders progress for homoerotic politics. Questioning the inclusion of some LG(BTQ+) “issues” in historically derogatory, US/UK media from the neoliberal 1990s onwards, researchers unpack the conditions under which LG(BTQ+) identities appear, the terms of representation, the scope of activities permitted (or not) once granted visibility, as well as whom or what benefits from such incorporations (e.g., Kate McNicholas Smith Citation2020; Larry Gross Citation2001; Ron Becker Citation2006; Suzanna Walters Citation2001). As these writers show, those featured are overwhelmingly young, attractive, cisgendered, able-bodied, mononormative (assuming monogamy is “normal”) (Meg-John Barker, Rosalind Gill and Laura Harvey Citation2018), and often male, white, and “western.” Moreover, their mediated worldmaking tends to hinge on achieving the “gay” right to enter such typically heteronormative and heteropatriarchal domains of marriage (Kate McNicholas Smith and Imogen Tyler Citation2017), property ownership, and respectable intimate “outness.” These “new” homo-mediations thus call disciplined, homonormative (Duggan Citation2002) subjects into being as they appear to expand representational intelligibility. Orientated around integration into, rather than transformation of, pre-existing gendered, raced, classed, and sexual systems, such anesthetized media “diversities” turn queer struggle away from collective organising, and towards assimilationist norms. As these newly-palpable sexual subjects enter platformed networks of consumption and exchange, then, they join neoliberalism’s gendered economies of visibility (Sarah Banet-Weiser Citation2018), in which a sanitized form of market luminosity supersedes political mobilisation as means and ends of “empowerment” for subjugated gender/sex subjects.

This research therefore highlights the limits of LG(BTQ+) mediated visibilities for sexual justice movements in the UK and North America. However, its terms of engagement mean it privileges majoritised communities in the global northwest. Thereby reflecting what, as many note are (e.g., Karma Chavez Citation2013; Audrey Yue Citation2014; Ahmet Atay Citation2021; Shinsuke Eguchi Citation2021), wider race, nation, and citizenship-based biases in queer communications theory. While some US-located scholars use their positions to challenge the sexual geopolitics of empire—showing how the US deploys Duggan’s (Citation2002) homonormativity to construct US exceptionalism on the world stage (Jaspir Puar Citation2007)—it does not offer much about actual homo-desiring peoples’ self-mediatory practices in the global south. This is especially true of the Arab world, which is under-theorized and under-represented in media scholarship in general, and queer feminist media literature specifically. Thus, because much of the existing cultural research on mediated sexualities critiques mainstream media legibility in the west, anti-normative queer embodiments (for instance, within subcultures), and intersectional (brown, black, working class, rural, religious, older, refugee, migrant etc.) queer positionalities are under-explored. Not only does this neglect those for whom sexual luminosity is undesirable, unsafe, or impermissible. It further dislodges important opportunities for theorising less visible or non-city-centric modes of queer worldmaking across a range of contexts (Richard Phillips, Diane Watt and David Shuttleton Citation2000).

Part of this problem is of course methodological. In bringing to light the compromised ways in which platform logics render LG(BTQ+) subjects intelligible under late-modern capitalism, analysis necessarily rests on data that can be seen. The queer textual commentator, in other words, can only launch a queer textual enquiry when presented with representations that can be read as “not-straight.” Echoing wider trends in media theorising, where audio-visual data rather than ethnographic study often retains object primacy, US-dominated communications research thus risks adding undue weight to the directly visible as it takes up queer theory.

We therefore need an empirically-grounded framework for conceptualising people’s shifting–potentially visible, potentially invisible—queer productions at different media junctures. A bottom-up model that avoids getting “stuck” at the level of representation, without losing site of the homonormative power relations that structure who or what is deemed worthy of LG(BTQ+) legibility within late-modern capitalism’s globally mediated chains of sexual signification. For this paper, this means asking how queer-identifying Palestinians’ self-fashioning practices unfold in the context of dominant, media-friendly visions of queerness form the northwest. How, if at all, does the former draw and/or differ from the latter?

Thus, a more salient (for this article) body of research foregrounds non-western lenses to theorise same-sex sexualities as negotiated, produced, and performed in people’s everyday media landscapes (e.g., Dina Georgis Citation2013; Eddie Omagi Citation2023; Emil Edenborg Citation2019; Ghassan Moussawi Citation2015; Masha Neufeld and Wiedlack Katharina Citation2020; Katharina Wiedlack Citation2023). Many of these writers problematise the politics of recognition that have dominated LGBTQ+ activisms in the global northwest since Stonewall. In his ethnographic work on queer clubbing in Nairobi, for instance, Omagi (Citation2023) explores how gay Kenyans cloak their sexual identities as they navigate the city’s homophobic police regime. Teasing out the spatial dimensions of self-chosen opacity, Ombagi argues that his participants shift between visible and invisible queernesses as they move between selectively-coded leisure hubs. Outside the club, queer men maintain corporeal invisibility in relation to wider non-queer communities, while their patronage inside the club communicates queerness to the other queers present. Here, then, invisibility becomes a technology of queer worldmaking, rather than merely state violence or queer absence. Described as a spatially-operationalised form of queer ambivalence, Ombagi thus challenges visible/invisible-emancipated/oppressed binaries to argue that what is read is always relational: it depends on context, location, and audience.

Similarly, Wiedlack (Citation2023) and Neufeld and Wiedlack (Citation2020) contend that lesbian women in Russia employ queer unrecognizability in effort to circumvent the heteronormative, heteropatriarchal, and imperial gazes that fix their bodies within rigid sexual ontologies. Whereas western representations of—mainly male—gay Russian subjects traffic victim narratives, Neufeld and Wiedlack (Citation2020) suggest, women’s DIY TV productions explore such complexities as what it means to use “transparent closets” for queer expression and identity-construction. This idea of the closet as selectively inhabited depending on audience and the level of safety it affords, again echoes the need to understand how technologies of queer self-formation always emerge in conversation with context. The maintenance of sexual indeterminacy, in other words, might better activate an affective politics of sexual subversion than its more visible counterparts in current-day Russia (Wiedlack Citation2023).

These contributions present insights into the ways that visible and invisible body stylisations produce queer subjectivities in relation to the dominant discourses of a particular sociohistoric order. Foucauldian (Citation2003, 145–169) technologies of self, in other words, through which human beings constitute themselves as subjects via the discursive and material resources to which they have contextual access. Foucault developed the concept of the technologies of self towards the end of his life. He wanted to understand how the technologies of power, or the political rationalities that forge a society via its governing systems and social institutions, produce subjects whose micro-behaviours, identities, and beliefs work in reproductive synergy with the macro-structures of knowledge and domination. Framing the technologies of self as immanent to the technologies of power—with the body acting as an intermediary between the two -, he argued that the subject’s methods of self-production always unravelled in connection with the scientific, religious, technological, and other discourses that make up a historical era. Subjectification (the process of becoming a subject) is therefore intimately bound together with certain forms of subjugation. The self, in other words, has no “inner” reality revealed through disclosure. Rather, self-knowledge is product and producer of historically situated praxis: a vehicle of power, and an object for analysing its operation.

This is useful for my purposes because it helps drill down into the power relations, or Foucauldian ‘truths’ (Citation2003, 300–318), that shape how people use physical artefacts, embodied practices, and cultural symbols to manage their identities within various social locations. For Foucault (Citation2003, 300–318), there is no position outside of power. While some subject’s cultural, material, and/or discursive position(s) in a given social order could enable them to question, pull apart, or reassemble norms (a process Michel Foucault (Citation1986) termed critical self-aestheticization), this always takes place in conversation with that norm’s pre-existing mode of administration. Put differently, transgression is, to some degree, always organised by that which it subverts. This framework is therefore not about the total overthrow of repressive structures, but the ways that an individual’s, or a group of individuals’ (often, those marginalised by some aspect of a structure’s distribution of resources and ideological centres of power), self-representations might create discursive fissures that bend, disrupt, or fashion anew some aspects of a disciplinary system, while (re)affirming others.

Thus, to understand how homoerotic self-making unravels in a specific epoch, we need to understand how that epoch’s prevailing political rationalities manage knowledge about gender and sexuality. In this paper, I am approaching music, fashion, and digital media as commoditised technologies of self that forge and perform contingently (in)visible queer subjectivities in contemporary Palestine: a political economic context fused through Israeli settler-colonisation, Palestinian political statelessness, and globalised neoliberal capitalism. Unravelling queer subject formation in colonised Palestine therefore necessitates situating how these local, regional, and transnational forces animate competing master-narratives of gender and sexual selfhood: an analytic to which I now turn.

Gender and sexuality in Palestine

Theorising sexuality from the Arab world makes reappraising the universalised frames in which liberal media discourse trades especially pressing. As scholarship on/from Palestine (Jason Ritchie Citation2010) and other Arab-majority countries (Georgis Citation2013; Moussawi Citation2015; Sabiha Allouche Citation2020) suggests, the notion that the “closet” forms the primary obstacle to queer flourishing requires adjustment. Primarily, because its individuated focus cannot account for the ways that Israeli settler-colonialism and patriarchal Palestinian nationalisms socially produce gender, and politically manage sexuality, in the colony. What role, then, do settler and anti-colonial normativities play in the production of sexualities and their liberatory strategies in current-day Palestine?

In his book Queer Palestine (Sa’ed Atshan Citation2020) argues that multifaceted gazes discipline LGBTQ+ Palestinians beyond the homophobic closet. Israeli institutions, queer Zionist activists, Palestinian governing bodies (the Palestinian Authority, PA, in the West Bank; Hamas in Gaza), Palestinian religious organisations, Palestinian familial units, and western-based journalists, filmmakers, and academics all, Atshan argues, appropriate queer subjectivities for different ends.

While overlapping, these regulatory pressures adopt distinctive logics on either side of the Green Line. In Israel, the state subjects Palestinians to its racist and racializing “pinkwashing” regime. For decades, the government has produced global PR campaigns focused on projecting Israel’s “gay friendly” status onto the world stage (Puar Citation2007). Globally, Israel showcases its institutional cache of homonational rights (to marry, adopt children, or serve in the military, premising Israeli-Jewish gay/lesbian “freedom” on the “right” to maim or kill Palestinians) to narrativize itself as a regional “gay haven.” Suturing sexuality to colonial power through orientalist discourse, this mobilises closet epistemes to equate “non-outness” with a place or people’s collective “backwardness.” Israeli-Jewish LG(BTQ+) visibility in Israel is thus a mechanism through which the state renders Palestine and the Palestinians “anti-queer,” “uncivilised,” and “regressive” enough to legitimise Israeli domination.

This does (at least) two things. First, it reroutes international attention from Israel’s genocidal war crimes and towards its supposedly “progressive” stance on LG(BTQ+) rights. Second, it reduces queer Palestinians’ “liberation” to domestication into liberal Zionist gay/lesbian identities. Which, as queer Palestinians demonstrate, grants Palestinians access to LG spaces as “out” non-heterosexuals, on condition that they renounce their “threatening” Palestinianness (Ghadir Shafie Citation2015). Because, then, Israeli “modernity” requires Arab “traditionalism” to operate discursively, queer Palestinians in Israel “must” make themselves available for rescue by liberal Zionist normativity, if they want to participate in Israel’s LG community circuits. And even then, as Ritchie (Citation2010) shows in his ethnography of clubbing with Palestinian friends in the Israeli-Jewish gay clubs of Tel Aviv, simply looking or sounding Arab is often enough to guarantee rejection at the door. The racializing checkpoint is, as Ritchie therefore concludes, far more likely to repress queer Palestinians than the individual closet. In Israel, sexuality is always entangled with settler-colonial discourses of civic racial supremacy.

In the West Bank, alongside Israeli pinkwashing, Palestinian LGBTQ+ communities are subject to an invasive web of internal heteropatriarchal surveillances. While same-sex relations are not judicially criminalised, in 2019 the increasingly unpopular PA introduced new legislation targeting LGBTQ+ organising across Areas A and B. Ratified amidst swelling civilian anger with the unelected, corrupt, and male-dominated political establishment, the leadership sought to bolster its own fragile rule by cracking down on gender and sexual diversity in the areas under its jurisdiction. Characteristic of populist administrations around the globe, this top-down attempt to erase LGBTQ+ Palestinians from the collective imaginary mobilised homophobic discourse to reinforce support for the pseudo-government among its conservative and patriarchal powerbases. In the West Bank, then, the ruling elite casts LGBTQ+ Palestinians as “foreign” threats to the social, moral, and political order of things, in effort to reproduce heteronational sovereignty in society.

These recent manifestations of anti-queer sentiments echo a longer history of gendered nationalisms in Palestine’s political cultures of resistance. Because Israeli domination works through orientalist scripts about Arab gender identities and sexualities (Walaa Alqaisia Citation2020), conventional Palestinian anti-colonial narratives suture regulatory femininities, masculinities (Rema Hammami Citation1990), and erotic desires to their resistance scripts. Like other anti-colonial nationalisms, men defend the nation through arms, while women reproduce its fighters via childrearing (Rhoda Kanaaneh Citation2002). Top-down Palestinian national discourse is therefore patriarchal and heteronormative. It premises the nation’s liberation on heterosexual sex acts, rendering same-sex desire a threat to collective survival. It is therefore banal, but necessary, to note that homophobic nationalism (Ebtihal Mahadeen Citation2021) in Palestine is, as elsewhere, performative and not reflective of ideal-type national identities and hegemonically-masculine aspirations for liberation. Homophobia, in other words, is a politically constructed rather than culturally fixed social relation.

In this context, closet metaphors again prohibit comprehension of the normative political work that sexuality “does” under military occupation and authoritarian rule. Moreover, because being “out” carries with it risks of social, psychic, and/or physical harm, as a liberatory technology it is limited to certain Palestinian subjects. Indeed, to come “out” publicly requires an individual has enough social and/or economic support in the community to contain the backlash such visibility might entail. Without these additional capitals, “coming out” – as elsewhere—risks threatening the familial or kinship ties (perhaps) required for socioeconomic reproduction, if state welfare is thin on the ground (Allouche Citation2020). As in other backdrops, then, being a sexually “out” self is more desirable when one has adequate class security. Activists in Palestine thus routinely advocate strategic invisibility as a safer, more pleasurable way to foster queer liveability in the colony (Lynn Darwich and Haneen Maikey Citation2014). In the West Bank, the experiential dimensions of sexuality are therefore in part shaped through socioeconomic hierarchies.

By dislocating sexuality from the colonial matrix of power, the allegorical closet undercuts the complex ways in which Israeli settler-colonialization and heteropatriarchal Palestinian nationalisms together animate sexual materialities on either side of the apartheid wall. In Palestine (as elsewhere), it is nonsensical to treat patriarchy or homophobia as stand-alone oppressions. Instead, refuting the individuating notion that moving past shame to pride by “coming out” liberates the gender/sexual self, Palestinian activists focus on the structural inequalities, and related cultural messages, that differently mark colonized bodies (Haneen Maikey and Mikki Stelder Citation2015). Mobilizing the politicised meaning of “queer,” these authors argue that the struggle for Palestine is a struggle against normativity, rather than (only) for national territory. The anti-racist fight against Israeli settler-colonisation is, in other words, immanent to the queer feminist fight against Palestinian heteronationalism: intersections that are illegible in platformed media’s preoccupation with liberal representation.

Methods

This paper is based on over a decade of engagement with the “alternative” music scene in Palestine. Over a twenty-eight-month period between 2012 and 2018, I conducted fieldwork in Palestine (Haifa, Jerusalem, Ramallah) and its diaspora (Amman, London) on the gender and sexual politics of Palestinian popular music. During that time, I carried out over one hundred qualitative interviews with musicians, fans, DJs, and event planners from Palestine; and took part in more than two hundred participant observations at the parties, bars, raves, and concerts they frequent. I also thematically analysed ca. fifty audio-visual documents (songs, music videos, live performances). I received full ethical approval from the University of Exeter in 2011, before fieldwork began. I took informed consent from all participants, ensured anonymity, gave pseudonyms to all transcripts, stored all data on encrypted software, and refer only by name to participants’ published materials.

To understand how music fashions queer subjectivities within its contexts of origin, I combine textual analysis with ethnographic data. My intention being to deepen representational materials with insights from the lives of its creators. First, I advance an intersectional, queer feminist reading of electro-pop artist Bashar Murad’s single, maskhara (mockery), released in 2021 through indie label PopArabia. Second, I weave evidence from my interviews and participant observations to discuss the cultural scene the song substantiates. I focus on this track because it critically reflects on gender and sexuality in the Palestinian case. Thirty-year old, Jerusalem-based Bashar is the only publicly-identifying queer musician living in Palestine—an identification partly made possible through his elevated class position and family’s supportive, artistic outlook (his father founded the influential 1980s band Sabreen). This is not to reduce Bashar or his music to innately “gay” and/or “middle-class” standpoints—his work also engages the politics of Israeli settler-colonialism, critiques the internal Palestinian leadership, and offers social commentary on a range of issues. Nonetheless, since much of his content satirises dominant femininities, masculinities, and heteronormativities, it helps theorise how popular music negotiates sexuality beyond the global north.

Before I attend to such themes, however, I want to note how my positionality shapes the material presented here. First, as a lesbian, I am interested in queer politics. And, as a lesbian, I am sceptical of the corporate take-over of LGBTQ+ desires in service of platformed media logics. Second, as a leftist, feminist, and anti-racist, I act—and write—in solidarity with grassroots struggles for social justice, in Palestine and elsewhere. This makes it critical to highlight that I stand in Palestine as a white ciswoman and bearer of a British passport: the state whose 1917 invasion of the Levant, and subsequent mandate in Palestine, provide(d)s ongoing support to the Zionist movement’s settler aspirations in the Middle East. My British positionality therefore enables and demands that I take a stand on Israel’s colonial project in Palestine. To write about Palestine, or any context of extreme injustice, in a “neutral” voice is to collude with the oppressor. I choose a side when I witness the violent ways in which the Israeli state abuses the lives, lands, and bodies of my Palestinian friends, colleagues, and research participants. I am not, however, a white saviour. Nor do I seek individual forgiveness for the British state’s past and present atrocities in Palestine. Instead, I hope my work might, in its own small way, stand in solidarity with those engaged in struggles for freedom and justice in Palestine and beyond.

Analysis

The song

Maskhara documents how settler-colonial power, capitalist fantasies about “the good life,” and sexed/gendered societal controls inflict economic, social, and psychic wounds on the colonised. Reiterating the track’s title (“Mockery”), the song uses play to expose and ridicule, as well as critique and reconfigure, how these discrete but intersecting normativities constrain everyday life in Palestine. Lyrically, the piece couples a potent sense of melancholic despair with an overwhelming desire to escape social reality. Throughout, Bashar reiterates the motif that someone or something is forcing him spatially, temporally, and affectively backwards. The opening lines, for instance, cynically state “two steps forwards, and ten back [khatuteen l’adam, w asha l’waraa] I see clouds these days, where’s the light? [shaif ghiem hal’iyam, ween al-fadaa?].” This sets the tone for the rest of the track. We hear about the army (al-jeish) with the machine gun (rashash) who demand he moves “back” (irja’ liwaraa) at a checkpoint; the society in which “no one understands [his] way of life [wala hada fahim asalebee]; and the cigarettes and whiskey that never satisfy him [ma bitkafeene], no matter how many he consumes. Amplifying the psychic impact of these mutually reinforcing structures on his mental health, Bashar describes being “depressed for two years [sarlee santeen fiktiab].” Discursively, the song thus points to the ways that colonial power (the army), social norms (the society that fails to understand him), and capitalist myth (that addictive consumer items, such as alcohol, numb wounds) together enact racist, gendered, and economic controls in the colony. The piece, in other words, linguistically renders a Fanonian (Citation1952 [2008]) take on the affective injuries that unjust systems of power inflict on the oppressed.

Interestingly, however, the embodied and sonic elements that also make up maskhara undo some of the desolation Bashar lyrically enfolds into the song. As is characteristic of his work, the track exudes a high-pop, almost saccharine musical energy. The beat is bouncy, playful, and extremely camp. Many of the lyrics rhyme (e.g., fadaa [lit. space, but here implying light/illumination via the sky] and waraa [back/behind]), further affecting the absurd. Bashar also intertwines Arabic oud melodies with his globalised electro-pop registers. This reiterates the singer’s Palestinian demography, and adds to the piece’s spirited tone. It is, however, Bashar’s self-directed YouTube music video that epitomises maskhara’s kitsch aesthetic. The footage locates the singer in the psychosocial reality of Palestine under Israeli domination. We see settler power permeating the most intimate of spaces—the opening scene, for instance, depicts Bashar sleeping in a bedroom surrounded by the ominously-grey concrete slabs of Israel’s apartheid wall. Other militarised signifiers appear throughout the text. Soldiers, checkpoints, and tanks visually perform the discursive sense of containment about which Basher sings. Importantly, Bashar intersects these images of colonial power with markers of emotional distress. As he vocalises struggles with his mental health, for example, we see the singer lying on a psychiatrist’s couch as a fair-skinned man in a doctor’s laboratory coat peers over him, flanked by two women in white nurses’ outfits. After which Bashar is manhandled into a straitjacket by several menacing-looking, medicalised figures. Conjuring a powerful sense of subjection to co-constitutively racializing military and medical gazes, this panopticon-esque imagery reinforces the notion that systemic subjugation to the prison (whether carceral or clinical) industrial complex inflicts extreme psychic violence on the colonised.

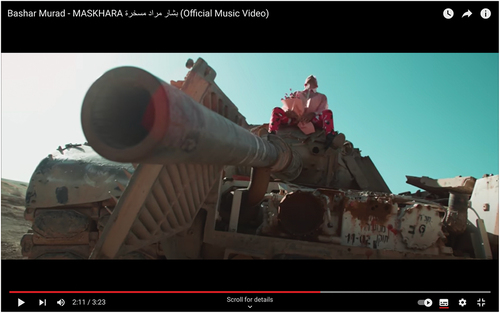

However, while these filmic imaginaries articulate psychosocial melancholia under settler domination, Bashar’s self-presentation in the video operates across a different register. Upending conventional norms around masculinity, and in stark contrast to the monotone hues of the apartheid wall and the psychiatric hospital, he wears fluorescent makeup and bright, flamboyantly-coloured clothing throughout. The closing scene is particularly powerful. It depicts Bashar in the West Bank on top of an abandoned Israeli tank. Both the vehicle and the landscape appear in muted, dull colours. Bashar, however, is wearing luminous pink army gear and camp, pink sunglasses. In his hand he holds a bunch of pink flowers. Intertextually evoking the 1960s “flower power” protests against the US invasion of Vietnam, we watch him stuff the bouquet into the tank’s phallically erect firing canon, which he subsequently straddles (). In dramatic contrast to the medical and military masculinities that dominated earlier shots, Bashar claims his own queer masculinity through stereotypically feminine pink signifiers, homoerotic bodily movements, and transnational anti-violence registers.

Queer masculinities, Palestinian heteropatriarchies, and Israeli homonationalisms

Immediately, then, we can frame the track and music video as Foucauldian (Citation2003, 145–169) forums of queer masculine self-making. Through movement, sound, dance, and dress, the spectacular camp aesthetics reassemble heteronormative ideas about gender and sexuality in colonised Palestine. As I have shown, social reproduction within conventional Palestinian national(istic) discourse depends on capitalist modernity’s sex/gender binary. In the video, however, Bashar self-fashions gender ambiguously, via femininity, on his homo-desiring, masculine-presenting body. He therefore queers (for those with the required reading glasses) the assumption that cisgendered masculinity and heterosexual eroticism are the innate “essences” on which anti-colonial resistance scripts necessarily unfold in Palestine. Understood from its Palestinian locale, then, maskhara satirises the PA’s crackdown on gender and sexual fluidity in the West Bank, forming novel materialities out of heteronational norms.

In addition, by topping a key icon of Israeli hyper-masculine military hegemony (the tank) with his queerly Palestinian-ised male body, the singer visually (a point to which I will return) anchors both queerness and Palestinianness to landscapes in which Israel denies either exist. Through this lens, the performance undoes the Zionist claim that gender and sexual difference is legible only under Israeli modernity. Bashar’s use of pink iconography therefore “pinkwatches” – that is, highlights to disrupt—the ways that the settler state, as well as the wider Anglo-Euro-American imperialisms of which it is a citation, represent Arab sexualities through orientalist frames to pinkwash Zionist colonial aspirations in the Middle East.

Rendered thus, the piece exposes how white supremacist capitalist patriarchy mobilises sex/gender discourse to (re)produce Israeli-Jewish ascendancy in Palestine. It thus reiterates that the struggle for Palestine is a queer issue. By suturing questions of sexuality to both homocolonial and heteronational governmentalities (and vice versa), maskhara refuses to reduce sexual justice to the single-axis paradigm (of rights, representation, and recognition) on which romanticised “diversity” discourse predominantly focuses. Instead, Bashar highlights how sexuality “does” politics in militarised contexts of extreme injustice. Repoliticizing liberal modernity’s depolitized ideas about queer rebellion, then, the song makes the case for understanding sexuality, and its discursive production and material regulation, in contextual conversation with the other (gender, race, class, nation, etc.) normativities through which Zionism produces Israeli hegemony in Palestine. It thus complexifies the relationship between sexual desire, gender identification, and Palestine’s revolutionary goals. And in so doing, marks gender and sexuality as currency for assessing whether Palestine’s decolonial future is to be realised, positioning the politics of sexual transgression as blueprint for decolonisation itself. This is not, then, about camp-as-failing (in Butler or Halberstein’s sense) to reiterate dominant norms, but instead, about camp-as-imagining a different social order via the rearrangement of such norms.

Queer visibilities—queer vulnerabilities

Given the trouble it makes for, in particular, heteronational power, as Bashar’s music (and alternative music in general) becomes more visible, it often engenders backlash among some in Palestine’s conservatively-aligned communities. In June 2022, for instance, the musician was scheduled to play a concert in Ramallah. A small group of young conservative men, however, shut down the show before it began. Emphasising the tensions between heteronational and queer-sexuality discourses, footage (later circulated on YouTube) shows the men accusing the venue’s staff of hosting a party for sexual perverts (hafla al-shudhudh al-jinsiyya). Mobilising homophobia, the confronting group conclude that such a “homosexual” (al-shaadhayn al-jinseeya: literally homosexual but—unlike the less-loaded term mithleen, meaning alikeness—connoting perversion/deviance) party would be anti-Palestinian, and thus required banning.Footnote1

Such moral panics are revealing because they zoom in on the contradictory work to which vernacular music is put to “do” at different societal junctures. The interchange between the bar staff and the conservative youth especially articulates problems with closet repertoires. Far from an individual’s online visibility leading to offline linear “progress,” we see instead the risks associated with “being out” in contexts where anti-colonial resistance narratives operate dissimilar gender and sexuality scripts. Here, then, music mediates anxieties around desire, public intimacy, modernity, and social change; spotlighting the multiple regimes of subjectification into which stateless, colonised, and globalised Palestinians are today unevenly incorporated.

While cultivating queer visibilities, music therefore also constitutes queer vulnerabilities. As a result, musicians often reported code-switching between different performance venues, in line with the level of safety they considered each to afford. Twenty-six-year-old West Bank-based musician Alaa, for example, told me about his wardrobe preparations for different shows. Alaa is a drag enthusiast and accomplished pole dancer. When we last met, he had a large show coming up in Ramallah. I asked him how he felt about translating the underground drag work he sometimes does in smaller clubs and private parties to this more publicly-accessible stage. And he said that:

Actually, I have been thinking about [performing in drag], but I don’t know if I’m ready to do it here [in Palestine]. I don’t know. I don’t know. I honestly don’t know … I have a really big performance coming up in April [and] I wanna do something big … I have in my head the idea that there has to be a bride on the stage, but I don’t yet know how it’s going to be – if it’s going to be me, or if it’s going to be [a ciswoman] … I’m not sure yet. I’m still working it out. I would definitely – in a heartbeat I would [perform in drag] if I wasn’t here, you know? I would sing the whole song in a wedding dress. I would love that. I feel like that would be perfect. But here, you know, you have to think twice about things. It’s not like I’m saying no, but I’m just thinking about the right way to do it for me. To not go too extreme all of a sudden, because I don’t wanna push people … I feel [safer] somewhere smaller, because [the big show] is very open to the public… the all male groups, you know the macho guys … . (Jerusalem, 02/02/2018)

Alaa weighs his personal desire to perform on stage in drag against his perceptions of gendered expectations in his community—as he thrice repeats, he “doesn’t know” how best to balance the two. The artist’s intimate deliberations over dressing and styling for the stage point to his understanding of bodies as engaged in sociocultural struggles over the moral legitimacy of sex and gender difference in society, here sited on contrasting visions of masculinity. His ambivalence reiterates the wider life that music and fashion take on in colonised Palestine, which in Alaa’s narrative mediate questions about what is and is not deemed permissible in embodiment. His comments thus present queer worldmaking as a potentially shifting social practice, subject to change between differently-coded contexts. Similarly to Omagi (Citation2023) and Wiedleck’s (Citation2023) participants, he ponders if maintaining certain levels of queer unreadability in mainstream publics might avoid the cultural marking that could impede queer liveability in Palestine’s underground enclaves, where signalling queerness is more commonplace. His thoughts therefore illuminate the internal conflicts and contextual blockages missed in analysis focused solely on signification.

During fieldwork, I witnessed many examples of such space and audience-based motif-switching. This photograph (), for instance, details one of Bashar’s shows I attended in Jerusalem. Differently to the spectacularly camp personas he writes into digital videos like maskhara, his onstage presence more closely adheres to modernity’s gender binary.

Furthermore, and speaking to the gendered asymmetries that shape differently situated subjects’ experiences of non-heterosexualities, lesbian and bisexual women rarely front their sexual identities in their public musical outputs or media interviews in the same way that some male figures in Palestine are able. Instead, embodied disclosure is centred on the safety and security that a particular space and its community is perceived to afford. While my interviews with lesbian and bisexual women often featured discussions of our various attachments to different queer femininities and self-identities, this was contained to the time-space of the interview, protected by participant anonymity, and made undeniably easier because I am lesbian-identifying. Achieving individual visibility was, then, an ambivalent, considered social practice for many of the queer young adults with whom I worked. For many, it was often not the most important aspect of quotidian getting by. These shifting modes of self-representation thus press the need to dispense with unhelpful ideas about queer “authenticity” in/of capitalist media cultures, which assume an internally coherent sovereign self fixes the subject to innate gender and sexual signs regardless of context.

Local pleasures, global entanglements?

As well as working outside fixed liberal identity codes, others highlighted that there is nothing inherent about “queer” markers that guarantees they will be universally read as such. As twenty-five-year-old, West Bank-based Omar noted, disparate vocabularies often underpin differently located readers’ viewing practices. While detailing the gender and sexual commentary he writes into his audio-visual productions, he said that:

… the thing is, not everyone understands what I’m trying to do … they think I want to dress up [to gender-bend] for fun, because it’s cool – I like that though, it gives me a bit of freedom to do what I want! (Ramallah, 03/04/2018)

Omar suggests that codes habitually rendered queer in global media are not necessarily interpreted that way by audiences in Palestine. His point is important because it stresses that queer codes are relational rather than universal. Signs have histories rooted to specific locations that shape their interpretation across different fields. For Omar, that some in his audience in Palestine might not understand his social and political intent is useful—it enables him to work as he desires, without becoming “trapped” by visibility in the fashion outlined above.

The notion of selective non-readability poses further questions about where, why, and to whom these technologies of homoerotic self-making are legible, if not to wider audiences in Palestine. West Bank-based artist Tawfiq sheds some light on this point. Similarly to Alaa, Tawfiq also enjoys spectacular camp styles. Outlining such influences on his work, he told me that:

I am obsessed with [the TV show] RuPaul’s Drag Race … I only started watching it last year, but I binge-watched the whole thing. Before I went to a few drag shows … in America … but I didn’t appreciate it at the time because I didn’t really get it … I thought it was just people dressing up, like a man dressing up as a woman. But then when I watched [Drag Race], I saw how much skill goes into it, and how much talent … it’s not just that you have to look pretty. You have to do your own make-up, sew your own clothes, do your hair, your own performance, whether comedy or music or dance, and then it made me really appreciate drag … Because it’s part of gay culture. I’m obsessed with drag queens! Like if you look at my Instagram, it’s all drag queens … they have so many ideas, and are so talented, and I even watch it to get ideas for performances … I definitely get inspiration from drag. (Jerusalem, 01/03/2018)

Tawfiq speaks to the transnationally-networked media platforms that make certain LGBTQ+ sensibilities available to those with discursive, cultural, and economic access around the globe. As he puts it, “drag … [is] a part of gay culture,” to which he asserts desired belonging via Instagram, TV, and America. His words thus recall the globally-familiar queer representations with which I opened this paper. As we have seen, in the Palestinian context, fashion and music cultivate a digitally-mediated embodied politics of heteronational and homo-settler-colonial remaking. For artists like Omar, the pleasures of using such items to cultivate and perform knowledge of oneself as a queer subject partly lies in their perceived capacity to remain “below the radar” of intelligibility across mainstream cultural publics in Palestine.

What Tawfiq therefore adds are the transnational vocabularies and digital materialities that make such relational opacities possible for some in Palestine. Moreover, noting that gender (whether read as straight or gay) is socially achieved via corporeal labour – “make-up … clothes … and hair[styles]”–he underscores how the technologies of self to which he, and others in his community, have access take shape through the commodities that neoliberal capitalism globalises for individuated identity distinctions. Which in effect attributes “gender-bending” qualities only to signifiers comfortable recognised as such by platform logics (items like the jalabiyya, or long “male” robes, do not, for instance, find themselves lauded in musicians’ media productions as queer satire). His words thus emphasise the material capitals required to engage in such commodity-mediated forms of gender non-conformity. Thereby underscoring the wider totalities with which Palestinian musical subjectivities are also entangled.

This is not to disappear the queer joys that gender subversion affords its patrons. It is rather to ground the economic elements of subjectification alongside its confrontational cultural counterparts. As a material practice, then, queer self-fashioning in Palestine is product and producer of transnational LGBTQ+ modernities mediated by global platform capitalism, which simultaneously contest and are contested by heteronational (Palestinian) and homonational (Israeli) regimes of control. The multiscalar normativities with which queer media from Palestine interacts thus warn against easy categorisation of the work as either total resistance to, or outright domination by, power (tropes common in cultural studies analysis of the Palestinian case). Instead, these musicians’ shifting sexual productions unravel in contextual conversation with intersecting settler-colonial, heteronational, and neoliberal-capitalist discursive materialities in contemporary Palestine.

Conclusions

This paper deployed a transnational perspective to consider how queer-identifying Palestinians’ self-fashioning practices unfold in the context of dominant, media-friendly visions of queerness form the global northwest. My main argument was that music constitutes a shifting politics of sexual (in)visibility in Palestine. Musicians move between more and less legible queer subject positions, depending on audience, locality, and framing. On one hand, camp embodiments foster queer masculinities that reimagine heteronormative and homonormative signs. Such cultural interventions celebrate queer erotica, and rebuke the militarised masculinities on which stereotypical settler-colonial and anti-colonial gender/sex scripts operate. On the other, however, while fashion, movement, and sound produce new possibilities about gender and sexuality locally, they also work through commodity spectacles found in platformed mediascapes. I therefore suggested that queer self-making produces and is produced by intersecting local, regional, and global complexes, into which Palestinians are unevenly incorporated.

Overall, then, the paper made the case for theorising mediated queerness from the Arab world, an underrepresented region in queer feminist discussions of popular culture and mediated sexualities. Thus, expanding the field’s predominant focus on sexual representations in global northwest media, the contribution provides insights on queer cultural worldmaking in contexts of settler-colonial domination, militarised occupation, and platformed capitalism.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Polly Withers

Polly Withers is a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at the LSE Middle East Centre.

Notes

1. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKoUfMkfxpE [accessed 09/09/2023].

References

- Allouche, Sabiha. 2020. “Different Normativity and Strategic ‘Nomadic’ Marriages: Area Studies and Queer Theory.” Middle East Critique 29 (1): 9–27. doi:10.1080/19436149.2020.1704504.

- Alqaisiya, Walaa. 2020. “Decolonial Queering: The Politics of Being Queer in Palestine.” Journal of Palestine Studies 47 (3): 29–44. doi:10.1525/jps.2018.47.3.29

- Atay, Ahmet. 2021. “Charting the Future of Queer Studies in Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies: New Directions and Pathways.” Communications and Critical/Cultural Studies 18 (2): vii–xi. doi:10.1080/14791420.2021.1907847

- Atshan, Sa’ ed. 2020. Queer Palestine and the Empire of Critique. Standard: Stanford University Press

- Banet-Weiser, Sarah. 2018. Empowered: Popular Feminism and Popular Misogyny. Durham & London: Duke University Press

- Barker, Meg-John, Rosalind Gill, and Laura Harvey. 2018. “Mediated Intimacy: Sex Advice in Media Culture.” Sexualities 21 (8): 1337–1345. doi:10.1177/1363460718781342

- Becker, Ron. 2006. Gay TV and Straight America. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press

- Chavez, Karma. 2013. “Pushing Boundaries: Queer Intercultural Communications.” Journal of International & Intercultural Communication 6 (2): 83–95. doi:10.1080/17513057.2013.777506

- Darwich, Lynn, and Haneen Maikey. 2014. “The Road from Antipinkwashing Activism to the Decolonization of Palestine.” Women’s Studies Quarterly 42 (3–4): 281–285. doi:10.1353/wsq.2014.0057

- Duggan, Lisa. 2002. “The New Homonormativity: The Sexual Politics of Neoliberalism.” In Materializing Democracy: Toward a Revitalized Cultural Politics, edited by Russ Castronovo and D. Nelson Dana, 175–194. Durham: Duke University Press

- Edenborg, Emil. 2019. “Visibility in Global Queer Politics.” In The Oxford Handbook of Global LGBT and Sexual Diversity Politics, edited by Michael Bosia, 348–363. Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Eguchi, Shinsuke. 2021. “On the Horizon: Desiring Global Queer and Trans* Studies in International and Intercultural Communications.” Journal of International & Intercultural Communication 14 (4): 275–283. doi:10.1080/17513057.2021.1967684

- Fanon, Franz. 1952. Black Skin White Masks. London: Pluto

- Foucault, Michel. 1986. The Care of the Self: Volume 3 of the History of Sexuality. Translated by Robert Hurley. New York: Pantheon Books

- Foucault, Michel. 2003. Essential Foucault; Selections from Essential Works of Foucault, 1954–1984. edited by Paul Rabinow & Nikolas Rose. New York: The New Press

- Georgis, Dina. 2013. “Thinking Past Pride: Queer Arab Shame in Bareed Mista3jil.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 45 (2): 233–251. doi:10.1017/S0020743813000056

- Gross, Larry. 2001. Up From Invisibility. New York: Colombia University Press

- Hammami, Rema 1990. “Women, the Hijab and the Intifada.“ Middle East Report. Accessed 10 20 2021. https://merip.org/1990/05/women-the-hijab-and-the-intifada/

- Kanaaneh, Rhoda. 2002. Birthing the Nation: Strategies of Palestinian Women in Israel. Los Angeles: University of California Press

- Mahadeen, Ebtihal. 2021. “Queer Counterpublics and LGBTQ Pop-Activism in Jordan.” British Journal of Middle East Studies 48 (1): 78–93. doi:10.1080/13530194.2021.1885850

- Maikey, Haneen, and Mikki. Stelder. 2015. “Dismantling the Pink Door in the Apartheid Wall: Towards a Decolonized Palestinian Queer Politics.” Thamyris/intersecting 30: 83–104

- McNicholas Smith, Kate. 2020. Lesbians on Television. Bristol: Intellect Books

- McNicholas Smith, Kate, and Imogen Tyler. 2017. “Lesbian Brides: Post-Queer Popular Culture.” Feminist Media Studies 17 (3): 315–331. doi:10.1080/14680777.2017.1282883

- Moussawi, Ghassan. 2015. “Uncritically Queer Organizing: Towards a More Complex Analysis of LGBTQ Organizing in Lebanon.” Sexualities 18 (5–6): 593–617. doi:10.1177/1363460714550914

- Neufeld, Masha, and Wiedlack Katharina. 2020. “Visibility, Violence, and Vulnerability; Lesbians Stuck Between the Post-Soviet Closet and the Western Media Space.” In LGBTQ+ Activism in Central and Eastern Europe, edited by Radzhana Buyantueva and Maryna Shevtsova, 51–76. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan

- Omagi, Eddie. 2023. “Nairobi Queer Visibilities/Invisibility and Forms of Queer Ambivalence.” Urban Forum 34 (2): 169–177. doi:10.1007/s12132-023-09485-z

- Phillips, Richard, Diane Watt, and David Shuttleton. 2000. De-Centring Sexualities. London: Routledge

- Puar, Jaspir. 2007. Terrorist Assemblages. Durham: Duke University Press

- Ritchie, Jason. 2010. “How Do You Say “Come Out of the closet” in Arabic? Queer Activism and the Politics of Visibility in Israel-Palestine.” GLA: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 16 (4): 557–575. doi:10.1215/10642684-2010-004

- Shafie, Ghadir. 2015. “Pinkwashing: Israel’s International Strategy and Internal Agenda.” Kohl: A Journal for Body & Gender Research 1 (1): 82–86. doi:10.36583/kohl/1-1-11

- Walters, Suzanna. 2001. All the Rage: The Story of Gay Visibility in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

- Wiedlack, Katharina. 2023. “In/Visibility and the (Post-Soviet) ‘Queer closet’.” Journal of Gender Studies 32 (8): 922–936. doi:10.1080/09589236.2023.2214886

- Yue, Audrey. 2014. “Queer Asian Cinema and Media Studies; from Hybridity to Critical Regionality.” Cinema Journal 53 (2): 145–151. doi:10.1353/cj.2014.0001