ABSTRACT

In this paper I describe how I used the creative writing of Interactive Fiction (IF) and autoethnographic playthroughs to gain a richer understanding of my professional identity as a secondary school English teacher and my positionality as a qualitative researcher working in the context of CentreTown academy. Using this novel combination of research methods, I offer insight into the discomfort and unease that I experience as an English teacher working in a large, inner-city secondary academy in England, as well as the factors that motivate me as a teacher-writer. These personal insights are remarkable, for in an education sector preoccupied with improving measurable outcomes, nuanced accounts of the discomfort that results-driven, performative approaches to education can produce become noteworthy counter-narratives.

June 2023

The conference that I am attending is well underway, and the air-conditioned auditorium is pleasingly cool in comparison to the sweltering afternoon outside. Slouched in a robustly upholstered, maroon-coloured chair, my notebook perched on the little fold-out table before me, I listen to the first keynote speaker as she describes the ‘rampant and joyful’ writing that occurred in the preschool environments in which she has worked (Rowe Citation2023). She foregrounds the value of allowing children to explore their personal interests with pens in their hands.

It is joyous. It is thrilling. It is painful.

For even as my smile broadens, I feel my body sag. When did the personal and the playful fly from my practice? Students entering my lessons at CentreTown AcademyFootnote1read the curricular texts that have been selected for them and write in response to the tasks that I direct them towards. Moreover, I no longer feel that I have the time to run the creative writing club that I did in previous years. During my lessons, the words rampant and joyful do not spring to mind. The playful sense of pleasure that the speaker conjures when she plays us videos of children writing is, I feel, uncomfortably absent in my own classroom.

And I feel myself a traitor, for I personally recognise that instruction which allows space for students to pursue their own interests and curiosities can be both effective (promoting good academic outcomes) and affective (resulting in positive dispositions and feelings) (Young Citation2019). However, this belief does not manifest in my practice, for I am part of an institution that values and enacts a curriculum that is rich in prescribed knowledge, but which allows little time and space for knowledge and experience generated via more personal forms of inquiry.

***

A week or so later, I sit down to begin redrafting the conference paper that I have entitled ‘Creative Writing and Autoethnography: A Layered Approach to Exploring Positionality’. I remind myself that autoethnography requires me to lay my vulnerabilities bare and to foreground a situated yet personal narrative, and so it is that I start to dig further into the conflicts that live through me and which relate to my work as an educator, conflicts between the personal and the prescriptive, the individual and the institution.

These conflicts feel important, for they are part of a personal story that subverts impersonal yet dominant discourses at play in the context of school-based education in England. I work in a large, inner-city secondary academy, an environment where measurable academic outcomes are valued highly, whilst the personal values of teachers feel subjugated (Ball Citation2003); an environment in which evidence-based practice is prized, but the word evidence remains narrowly and undemocratically defined (Biesta Citation2007; Yandell Citation2019); a world in which cultures of surveillance and datafication narrow the focus of education, focusing teacher attention on performance rather than learning, on data rather than lived experience (Page Citation2017); an educational environment that seems to privilege white, middle-class norms (Kulz Citation2014) and to position democratic ideals as ‘bumps in the road to market-orientated progress’ (Kulz Citation2020, 66). These dominant and impersonal narratives can make academies feel like exam factories (Hutchings Citation2015). They also work to marginalise and silence qualitative accounts of personal discomfort, accounts that do not feature in the experimental evidence-base from which school leaders routinely draw (Biesta Citation2007). As ‘qualitative methodologies provide an effective counterpoint to the quantitatively driven nature of the academies programme’ (Kulz, Ruth, and Kirsty Citation2022, 13), I am here working to bring such an account to the fore, to tell a research story that grapples with my own nuanced sense of unease.

An index of methods

I look to my left. On the kitchen table beside me is the novel that I am currently reading: Elena Ferrante’s The Story of a New Name (Ferrante Citation2013), a novel in which the author helpfully offers readers an index of characters at the start of the book. I could do something similar, I think, by providing my readers with an index of methods, methods that play a significant role in the unfolding of this particular story.

Action research

This article forms part of a larger Educational Action Research Project (Noffke and Brennan Citation2014) exploring the possibilities for Interactive Fiction (IF) in the secondary school English classroom. As an Action researcher, I interrogate my own practice as a teacher of English and as a writer of IF. As such, my own positionality is of vital importance; the variety of fluid ways in which I relate to both secondary schools and the genre of IF form an important part of my work. My positionality is shaped by my values, and Action Research is a fundamentally values-based form of research, as the values of the researcher provide the impetus for the intervention that is enacted (Coghlan Citation2016; Coghlan and Shani Citation2021). Therefore, it is important for researchers like me to establish ways of interrogating and articulating their own nuanced values and the experiences that lie behind them. In this paper I use various forms of writing in order to look beyond my professional role as a teacher, rendering myself more ‘accountable and vulnerable’ (Denzin Citation2003, 137) by exploring some of the personal feelings and formative experiences that shape my positionality.

Creative writing

Central to this research is the creative writing of a work of IF entitled The Doodle (Holdstock Citation2022), a story that is set in a secondary school environment. However, the extent to which the creative writing of such a work might be seen as a research method is contested (Kara Citation2015). Writing is often seen as a means of presenting research findings, rather than a means of producing knowledge (Cook Citation2013). Creative writing is also frequently positioned as a form of artistic or imaginative practice rather than a research method that can contribute to the production of knowledge (Cowan Citation2021). The work of creative practitioners is not always ‘understood’ or ‘valued’ in academic contexts (Webb Citation2012, 9). However, imaginative forms of creative writing can be a valuable ‘means of discovery’ (Cook Citation2013, 204), drawing attention to things that the researcher in question might otherwise remain unaware. I adopt this stance, conceptualising research methods diffractively; my methods do not represent or replicate the world, but they do shape or interfere with the ways I perceive my experiences (Haraway Citation1992). Creative research methods can therefore help us to map our perceptions in ways that traditional methods do not, enabling us to respond to different research questions (Kara Citation2015). From this perspective, creative writing can ‘bring what is experienced as outside or beyond language into language’ (206). Moreover, ethnographers use creative forms of writing when they imaginatively synthesise narratives, drawing upon data to produce writing which conjures a ‘resonance of truth’ – texts that strive not for accuracy of representation, but which instead use literary techniques to convey a more personal truth (Davis and Ellis Citation2013). Clough argues that, within the world of education, there is an urgent moral need for researchers to share such personal truths, for in a sector where the ‘furniture of audit’ works to marginalise the personal, researchers need to tell the truths that might otherwise never be heard (Clough Citation2002, 99). In this paper, I use the creative writing of IF as a means of discovering a nuanced and personal truth that might otherwise remain hidden. In so doing, I engage in a Creative Analytical Process (CAP) that uses various forms of writing, including creative writing, to unearth ‘that which was unknowable and unimaginable using conventional analytic procedures’ (Richardson and Elizabeth Citation2005, 963).

Autoethnography

Autoethnography involves the production of a self-narrative, a written exploration of the self as a socially situated entity (Denzin Citation2014); it connects the ‘personal to the cultural’ (Ellis and Bochner Citation2000, 739), often seeking to portray personal experience in an imaginative and evocative fashion (Muncey Citation2010). To adopt such an evocative style is an academically unconventional choice and has resulted in some researchers struggling to find outlets for the dissemination of their research (Muncey Citation2010.). However, it must be stressed that autoethnographers are often committed to an ‘analytic research agenda’ (Anderson Citation2006, 375), and while Ellis and Bochner argue that autoethnography is not a vehicle for producing ‘distanced theorising’ (Citation2006, 433), autoethnography does seek to critique the relationships between an individual and their social situation, often requiring the researcher to reveal their vulnerable self (Muncey Citation2010, 50).

However, autoethnography does not necessarily reveal ‘the self to the self’ in the same way that creative writing does, as it does not engage with ‘unconscious processes’ in quite the same fashion (Cook Citation2013, 200). As a result, I here assert that a combination of creative writing and autoethnography might enable a researcher to understand their own positionality in ways that individual methods would not allow. Both methods require the writer to use language in evocative and imaginative ways and cannot therefore be viewed as entirely distinct from one another. Gilbert and Macleroy (Citation2020) have argued that researchers can use autoethnography to research creative writing, and I here seek to extend this claim by arguing that researchers might find the writing of fiction to be a useful research method when used in conjunction with autoethnography. To research my own positionality in this paper, I seek to conduct ‘Good Autoethnography’ (Adams and Herrmann Citation2023) by producing a reflexive account of my own (auto-) experiences reading ‘The Doodle’. In so doing, I provide a unique perspective on the positioning of teachers and students within English secondary schools today (ethno-). Finally, I attempt to do so in an innovative and evocative fashion, engaging in a creative analytical writing process (−graphy).

Interactive fiction

Written texts that produce ‘narrative during interaction’ (Montfort Citation2011, 26) and which are read using digital devices such as computers, tablets or smartphones can be defined as works of Interactive Fiction (IF). Such works of fiction are typically non-linear, as the narrative produced varies depending upon the decisions and actions of the reader/player. Choice-based works of IF like ‘The Doodle’ can be written using the open-source writing tool, Twine (Klimas Citation2016). I introduce IF here, as the creative writing of IF plays a significant role in this research story; the fact that my research involves the creative writing and autoethnographic analysis of ‘The Doodle’ renders it novel, as such a combination of methods has not, to my knowledge, been employed by other researchers within the field of education. Moreover, using IF as a means of exploring the identities and experiences of practicing teachers is a worthwhile endeavour, for although IF is said to have the capacity to enable the production of ‘games exploring personal experiences’ (Friedhoff Citation2014) and texts that can ‘put players into the mind of a game’s creator’ (Sarkar Citation2015), it has yet to be used by researchers to consider, for example, the identities of teachers as writers (Cremin et al. Citation2019).

The Playthrough

I here argue that playthroughs can be used to produce autoethnographic accounts of texts produced via creative writing. In ‘Videogames For Humans’, writers play works of interactive fiction, providing readers with reflective accounts of the reading/playing experience. For example, Lana Polansky conducts a playthrough of ‘Mangia’ by Nina Freeman (a game exploring the writer’s experience of chronic illness) (Freeman and Lana Citation2015). As she conducts this playthrough, Polansky writes about how the story made her think and feel about her own past medical experiences. Inspired by this form of playthrough, my own research features an autoethnographic playthrough of a self-authored work of IF.

Rhizomatic Analysis

In my autoethnographic playthrough of ‘The Doodle’, I position the story as a rhizomatic text and analyse it accordingly. Drawing upon Deleuze and Guattari’s conceptualisation of a rhizome as an evolving and fluid network of relations (Deleuze and Guattari Citation2003), rhizomatic analysis positions texts as rhizomatic, examining the ‘intertextual linkages not only between different texts but also between texts and the socio-cultural and political “stems” that adhere to the creation and reading of the text’ (Gardner Citation2014, 232). Adopting such an approach facilitates an understanding of ‘the connectivity of the self to the social world’ (244), and in considering the connections that I perceive to exist between ‘The Doodle’ and the social world in which I participate, I discover qualitative aspects of my own positionality. To view texts rhizomatically is to suggest that language does not represent content, but rather interacts with it in a complex and fluid array of ways. No two rhizomatic journeys are the same, making all textual readings somewhat unique (Leander and Wells Rowe Citation2006). The rhizomatic singularity of a reading (or playthrough) reveals its personal nature and, as such, rhizomatic analysis feels like an appropriate method to employ given that I am aiming to explore my personal and evolving sense of unease. Moreover, given the non-linear nature of choice-based IF, a rhizomatic approach that recognises the fluid and networked nature of a text feels apt; like a rhizome, a work of IF is not organised in a linear fashion on a printed page, but can instead be navigated (and understood) in a variety of ways.

My research story: a summary

Right now, this paper is feeling rather fragmented; I’ve started with a vignette and followed that up with an index of methods, but how does it all fit together? How can I put all these pieces into context? As an English teacher, I sometimes refer to study guides and plot summaries with my students, using them as tools to help students consolidate and develop their understanding of the stories we are studying. At this stage of my paper, I think, something akin to a plot summary might help my readers to understand and contextualise the story I am trying to tell.

I used the above-described research methods as part of my PhD action research project exploring the possibilities for Interactive Fiction (IF) in the secondary school English classrooms that I work in. Said project began in 2019 and was initiated in response to a ‘living contradiction’ (Whitehead Citation1989, 44); on the one hand I wanted to teach in a way that nurtured the meaning-making capacities of my students. On the other hand, I found myself enacting practices that positioned pupils as passive recipients; when studying texts, I felt that my students were receiving interpretations rather than participating in the social practice of meaning-making (Street Citation2003). As choice-based IF depends upon readers making choices, I felt that it could help me to facilitate a greater degree of participation amongst my students, preventing them from becoming passive recipients of teacher-delivered, prescribed ideas.

At the start of my research, I conducted some reconnaissance to find out more about Twine, Interactive Fiction and the ‘living contradiction’ that I felt to exist. To do this, I began writing a work of IF that is set in a secondary school classroom: ‘The Doodle’. While The Doodle is a work of fiction, it is inspired by my experiences working in CentreTown Academy – a large, inner-city, secondary academy that forms part of a multi-academy trust.

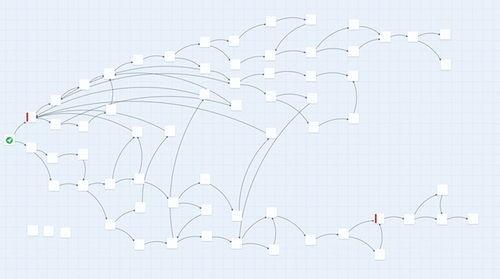

The Doodle is a non-linear story that explores one young carer’s experience of a school day. During the story, a doodle that she draws in the margin of her exercise book comes to life, resulting in a range of potential consequences. A story map of The Doodle can be seen in .

Figure 1. An up to-date story map for the doodle (Holdstock Citation2022).

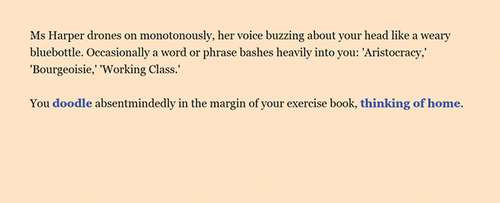

In 2020, I began conducting an autoethnographic playthrough of this text, narrating the experience of reading/playing The Doodle and exploring it rhizomatically by considering the various personal and intertextual linkages that I felt ran through it. In revisiting the story in this way, my positionality as a teacher and a researcher became increasingly ‘legible’ (Stewart Citation2014, 119); it began to ‘quicken, rinding up like the skin of an orange’ (Stewart Citation2010, 339). As a result, the playthrough developed over time; I have revisited and enriched it on several occasions, and a short extract from it forms the following section of this paper. The extract contains an autoethnographic reading of a single passage from ‘The Doodle’ (), demonstrating the way that an autoethnographic playthrough of a piece of self-authored interactive fiction shed light on the nuanced sense of unease to which I have already alluded.

Figure 2. The opening passage from the doodle (Holdstock Citation2022).

The Playthrough: an extract

This is the section where all the pieces must come together, where the research needs to come to life. I’m a little nervous as I begin re-reading and tinkering with my playthrough. I’m only sharing a short extract of it in this paper, an extract which includes a reading of a single, short passage from The Doodle. Will this be enough? How much can this single passage uncover for me and for my readers? To what extent will I be able to help them see what I feel?

As the passage visible in shows, The Doodle begins in a classroom setting. I do not state this explicitly, but the signs are clearly there – one character is given the title of ‘Ms. Harper’ rather than a first name, and you, the protagonist, are doodling in your ‘exercise book’.

My own relationship with classroom spaces is based on a wealth of past experiences: as a child I was privately educated at two independent boys’ boarding schools. At these establishments I spent a great deal of time in classrooms, studying, learning, reading and socialising. Moreover, as an undergraduate, master’s student and now as a PhD candidate, I have entered many more classroom environments, each one different from the last. Finally, as a professional adult I have worked in secondary school classrooms as an English teacher, form tutor and employee. With this wealth of classroom experience behind me, I feel comfortable entering a classroom space, as I understand broadly what is expected of me. This is because, as an able-bodied white man who is a proficient speaker and writer of standard English, I am on the privileged side of an entrenched linguistic divide; in the context of school-based education, linguistic proficiency is often understood using ‘deficit and dichotomous framings’ that position ‘working-class, disabled, and racialised children as producing less legitimate language than their wealthier, able-bodied, and white peers’ (Cushing Citation2024, 1). My classroom comfort derives from my own racial and class-based privilege.

However, I also associate the classroom space with a degree of stress and anxiety. As a schoolboy I was, on some occasions, made to feel insecure about my academic ability as well as my social role within the dynamic of class, and as a teacher I have seen multiple students react badly to the confines and expectations of the classroom.

Thinking of classrooms sends my mind meandering back to French classrooms that I sat in as a schoolboy. I was in the top French set for several years at secondary school, but I felt somewhat inadequate within this space. My teacher set us weekly translation quizzes that tested us on the grammar and vocabulary we had encountered that week, and I remember performing poorly. There were native French speakers in the class, a fact that exacerbated my insecurities and reduced the linguistic privilege to which I was accustomed. During the lessons, my teacher posed a large number of challenging questions, and I regularly felt worried that my inadequacy as a linguist would be exposed.

Moreover, older students from my boarding house were taught in the classroom opposite, and they would regularly be dismissed before us. As they passed our open door, they would call to me in a high-pitched trill: ‘Sammy!’ Their mockery of my then high-pitched voice still makes my skin crawl, particularly when I recall the face of my French teacher. He did not support me by speaking to these older students or even by closing the door, choosing instead to join in with the laughter. Students in my own class, along with the teacher, started referring to me as Sammy, using an artificially high pitch when doing so, highlighting something else that marked me out as different and seemingly inferior to other members of the all-male group. As a result, the classroom became a space within which I felt increasingly vulnerable and defensive. Part of me enjoyed the pressurised environment of that particular top French set, but part of me was always on edge, aware of my own vulnerability.

I know that I learned an enormous amount in that French class, but I still carry with me the discomfort instilled in me by the teacher in question. The tension that exists in the opening passage of The Doodle between the teacher’s imposed droning and the student’s distracted doodling brings these memories to mind; as a reader I am wondering when the student will be found out, when their doodling wilfulness will be exposed to Miss Harper’s straightening hand, an educational force that works to straighten ‘out the body of the child so that the child, in willing right, faces the right way’ (Ahmend Citation2014, 72).

In the opening passage of The Doodle, the protagonist draws in the margin of their exercise book. For me, the doodle here functions as a symbol of creative self-expression, a form of creativity that is quite literally being marginalised by the student, the school, the teacher, or some combination thereof. However, the doodling is occurring inside an exercise book; the school is providing the student with creative resources – a book in which to doodle. There is a tension here; on the one hand school seems to be facilitating creative self-expression. On the other hand, such creativity can only occur in the margins of an exercise book – it does not take centre stage.

Again, I recollect my days in the secondary school French classroom, noticing as I do so, the ways in which The Doodle continuously draws my attention to questions of linguistic privilege by reminding me of a classroom space in which my own privilege was reduced. Every year our French teacher would give us a hardback notebook in which to jot down new vocabulary that we encountered. However, said notebooks were never checked, and I usually took them back to my room at the boarding house and used them for writing private poems, rhymes, song lyrics and random jottings. Their textured, hard-backed solidity was satisfyingly secure and made my creative endeavours feel more substantial. However, I never wrote in this personal style during lessons, perhaps because, as I have already explored, classrooms were not always places in which I felt secure. Moreover, although there were ample opportunities for me to participate as a school student in extra-curricular creative activities such as school plays and musical productions, the public nature of such activities and a perceived elitist attitude to creative ability made them feel intimidating for students who, like me, felt somewhat vulnerable or relatively inexperienced when compared to their peers. My high voice had already been mocked by others, so taking to the stage was an unwelcome prospect.

Like the character in The Doodle, I used school resources to do something creative. Like the character in The Doodle, I did so in the margins, surreptitiously, appropriating academic resources for my own creative ends. However, as a boarder, I was able to engage in such creative forms of expression in my own room. I had my own relatively secure space, my own desk, quiet hours of free time during which I was free to do my own thing. In contrast, the character in The Doodle is in a lesson, and perhaps does not have the time and resources to engage in self-directed creative endeavours. At CentreTown Academy, the school where I work, the school day starts at 08:25 when students line up outside, and ends at either 15:25 or 16:15, depending on the day. Students have one 20-minute morning break and one half-hour lunch break. All teachers are encouraged to follow a prescribed lesson structure that respects Rosenshine’s principles of instruction (Rosenshine Citation2012), to incorporate explicit instruction into their lessons and to draw from a prescribed range of teaching techniques, techniques akin to those found in Doug Lemov’s ‘Teach Like A Champion’ (Lemov Citation2015). For example, teachers are encouraged to instruct their students to SLANT, and SLANT posters can be found in many classrooms, suggesting that students’ bodies and gestures are constantly being ‘standardised and regulated’ whilst they are at school (Cushing Citation2021). As such, from the perspective of a student, the school day might seem somewhat repetitive, limiting and creatively stifling. Personally, I would feel inclined to forgive a student for doodling in the margin of their exercise book, whilst simultaneously feeling obliged to intervene in order to divert their attention back towards the lesson content. For me, the passage dives into the heart of this conflict, the conflict between creative self-expression and institutional expectations. As a teacher, I am forced to confront my own discomfort regarding the role that I play in this conflict; I feel obliged to respect institutional expectations whilst also recognising the limitations that they impose upon self-expression. As a teacher, I sometimes feel stifled and ‘uncreative’ due to the nature of the accountability systems which shape my work (Perryman et al. Citation2011), and I suspect that students might feel similarly stifled.

As a teacher reading this passage from The Doodle, I also acknowledge a rising sense of tension; the classrooms in the school where I work have glass walls that allow passing teachers to look in; learning walks and lesson drop-ins are a common occurrence. In fact, readers of The Doodle are simultaneously positioned as the protagonist (‘You’), and as an observer; I am reminded of the lesson observations and drop-ins that I have conducted, times when I have watched teachers and students in the classroom, noting the ways in which they behave. To what extent could a student’s off-task doodling be sustained in such a surveillance-rich, post-panoptic environment (Page Citation2017), and will this particular student face some form of sanction? I remember the zero-tolerance tactics of the academy described in Kulz’s ‘Factories For Learning’ (Kulz Citation2017), and I wonder how much doodling this student will get away with.

In this passage from The Doodle, the protagonist, like the students I encounter on a daily basis, is sat in a classroom. She is a student, and as such forms part of a teacher-student relationship that involves an unequal balance of power. My understanding of this power imbalance adds to the rising sense of tension evoked by this passage. In schools like CentreTown Academy, school-wide habits and routines encourage and enable teachers to control the embodied behaviour of students. In the same way that teachers at King Solomon Academy can ‘clap in a particular pattern to gain the class’s attention’ (Duoblys Citation2017), teachers at CentreTown Academy can, like military commanders, expect all students to fall silent, raise their hands and face the front when they themselves raise their hands into the air. Furthermore, much like the staff at King Solomon Academy, many teachers at CentreTown Academy are relatively young and white. Being a white, male, materially and linguistically privileged and privately-educated teacher working in a state-funded, inner-city, secondary school with a diverse student community, I often feel uncomfortable with the socio-economic teacher-student power dynamics that are at play in the classrooms within which I work; to my students, I both embody and enforce the white middle-class norms that academies can seek to impose upon students (Kulz Citation2014). Therefore, the setting of The Doodle brings my discomfort to the fore; I do not merely ask myself if and when the protagonist will get caught doodling, but I am aware of the race and class-based power imbalances that are potentially at play, and the military-style interventions that could be used to uphold them.

When I was a school student, my classes were quite small; I do not recall sitting in a lesson alongside more that 18 other boys. Moreover, we routinely sat in a horseshoe formation, and many of my English lessons were dominated by whole-class discussions. Contrastingly, almost all classrooms at CentreTown Academy feature desks that are organised into rows which face the front of the room, and classes typically contain up to 32 students. Whereas when I was at school, whole-class discussion formed a significant part of what it meant to study English, at CentreTown Academy, lessons are rather more PowerPoint oriented, with less time and space available for whole-class discussion and student contributions. For me, the lack of time and space available for student contributions and public acts of self-expression reflects the increased attention that government and schools are paying to curricula that are deemed to be ‘knowledge-rich’ (Gibb Citation2021). Foregrounding prescribed curricular knowledge can spark debates amongst educators regarding the relative importance of knowledge and skills. It can also serve to position teachers as ‘little more than transmitters of knowledge’ (M. M. Young Citation2018, 2). Most importantly for me though, it can signal the marginalisation of the funds of knowledge and experience that students bring into the classroom themselves (Moll et al. Citation1992), and it is this marginalisation that causes me discomfort as I read this passage from The Doodle. Why, for example, is Ms Harper so disconnected from the student in this passage? Why is her voice described as a monotonous drone and compared to a ‘weary bluebottle’?

My concern regarding what I shall here describe as a teacher-student disconnect, coupled with my discomfort regarding the power dynamics at play within secondary school academies such as the one where I work, may explain why I chose to include the words ‘Aristocracy’, ‘Bourgeoisie’, and ‘Working Class’ in this opening passage of The Doodle. Ms Harper teaches her students about Marxist class consciousness by lecturing them in a monotonous drone and without questioning them or encouraging them to interrogate the issues of class, power and privilege that are at play in their own lives, their own classrooms. For me, the passage therefore seems to interrogate educational forms of hypocrisy, living contradictions that are enacted by practicing teachers and school leaders. I am reminded again of Kulz, who argues that in the neoliberal academy, ‘structural inequalities’ linger ‘beneath the rhetoric of happy multiculturalism and aspirational citizenship’ (Kulz Citation2014, 685). As a story The Doodle was partly inspired by a video I watched about young carers (Trust Citation2018), but the protagonist’s status as a young carer is not revealed in this passage. The disadvantages she faces as a result of her status as a young carer are rendered invisible to both the reader and the teacher. In fact, such forms of disadvantage are actively concealed by impersonal pedagogies and an emphasis on prescribed knowledge rather than funds of knowledge, a fact that triggers discomfort in me and that I believe I sought to interrogate when writing this story. As a teacher, it is the unpredictability of student contributions and interactions that makes teaching a joyous and exciting profession for me. In this short passage, these exciting educational opportunities occur only in the margins, in the background, behind the teacher’s dominant drone.

Where impersonal pedagogies are concerned, I worry that the popularity of direct instruction as a teaching strategy can lead English teachers towards monologic forms of practice that do not allow space for students to express their feelings and opinions (Gilbert Citation2022). Perhaps, therefore, Ms Harper is the teacher I fear I might be, or could become. I worry that monologic teaching practices could render me indifferent towards the creativity and life experiences of the students I teach. The verb drone that I use to describe Ms Harper’s voice is suggestive of exactly such a form of indifferent, mechanical teaching.

The character of Ms Harper is certainly shaped by my own experiences. As a child and later at university, I attended many classes, workshops and lectures that were not designed in a way that maximised student engagement. I recall a linguistics course that I took during my Erasmus year in Paris. The class was small – there were, I seem to remember, only half a dozen students in attendance. Every Wednesday morning, we met for three hours to listen to the drone of a senior lecturer who was approaching retirement age as she buzzed her way through a detailed account of the French language’s linguistic history. She spoke in French, and although my French was at a good level, I struggled to follow her. Her lectures were littered with complex terminology that I did not understand, and I regularly fell asleep. She did not always notice my drowsiness, engrossed as she was in the hand-written lecture notes that she kept in an old and battered exercise book. Ms Harper then, as well as representing a teacher who is somewhat indifferent to the personal identities and humanity of her students, embodies a form of teaching that does not attend to the way a learning experience might feel for the students involved. Her drone does not excite me, and it does not seem to interest the story’s protagonist.

At the end of this passage, how best to proceed? I have two choices available to me: I can click on the ‘doodle’ or on the phrase ‘thinking of home’. Both options appear to offer something that is of interest to me: if I select the doodle, I believe I will find out more about what the character is drawing, how they are choosing to express themselves, but if I select the second link, I will likely discover more details regarding the students’ home life and, perhaps, the reasons behind their distraction. Both options offer me, as a reader, a potential chance to connect more deeply with the student-character in question. Both options offer me something that I, as a teacher, am looking for.

Discussion

The playthrough feels rich, layered, textured, but perhaps a touch messy. What do I want my readers to focus on? How can I put this rhizomatic tangle of feeling into some sort of frame for my readers to look at and to interrogate? And what are the big ideas that I want to present to my readers as noteworthy topics for contemplation?

The above playthrough extract reveals some of the connections, relations and linkages that form The Doodle. For me, in the context of this playthrough, the passage that I have considered exists in fluid, rhizomatic relation to a range of other texts, memories, places, discourses and desires. My qualitative exploration of this rhizomatic text has allowed me to form a greater understanding of the sense of educational unease to which I have alluded. As a teacher of English, and a teacher who writes creatively for pleasure, it is the marginalisation of creative self-expression and students’ own funds of knowledge and experience that seems to concern me; such processes contribute to a worrying teacher-student disconnect, a disconnect that is exacerbated by school-based cultures of surveillance, uncomfortable race and class-based student-teacher power imbalances, monologic and seemingly impersonal pedagogical approaches, an emphasis on knowledge-rich curricula, and the concealment of structural inequalities that shape the educational lives of students.

My creative writing and autoethnographic playthrough also helps me to better understand what drives me as a teacher. My desire to enable my students to participate more fully in the creative process of meaning-making during English lessons appears to be underpinned by a desire to render my classroom a space in which creativity is respected, funds of knowledge and experience are valued, and students are made to feel secure and inspired rather than vulnerable and disengaged. As such, my playthrough helps me to understand my uneasy positionality in relation to the performative school culture within which I work and the students with whom I share the classroom. Moreover, by writing imaginatively and autoethnographically, I have strengthened the connection that exists between my writerly and my teacherly selves. This process has enabled me to recognise the joy that I, as a teacher-writer, find in forging human connections within the classroom space and in facilitating unpredictable acts of imaginative self-expression.

Conclusion

It’s September 2023, and I’m presenting at the conference now, nearing the end of my session. What do I want my audience to take away from this paper? In what ways could my research story influence or impact them, and how can I get this across? For me, the most important thing is not actually the novel combination of methods I have employed, but rather the countercultural, qualitatively rich and messy story that said methods have helped me to unearth. Yes, I pitched this as a methodological paper, but I’m not presenting my readers with a neat methodological package that can offer them a reliable way of discovering an elusive truth about themselves. Instead, I’m offering them a research story that, I hope, will mean something to them.

I have here described how I used creative writing in conjunction with autoethnographic playthroughs to produce unique insights into my own positionality, using these methods to unearth the personal values and desires that motivate me, and which contribute to my own discomfort and unease. However, my methods are perhaps best considered in the context of a more extensive ‘research-assemblage’ (Fox and Alldred Citation2015). My research-assemblage includes the methods I have described, but also encompasses a range of connected entities: memories, spaces, materials, texts and discourses that my rhizomatic approach to autoethnography has brought to the fore. For example, I have explored the ways in which my relationship with teaching and with CentreTown Academy is informed not only by, for example, Kulz’s research into neoliberal academies, but also by my own socio-economic privilege and my memories of my time at school. I have described the way in which this assemblage relates to the sense of unease that I experience as a teacher-writer working in a secondary academy and the factors that motivate and excite me. I believe that the unearthing of such things renders this research story, and the research methods involved, remarkable, for in an education sector preoccupied with the discovery and implementation of strategies that seem capable of improving measurable outcomes, textured accounts of the experiences and feelings of teachers – things that are not easy to measure – become noteworthy and important counter-narratives.

Ethical approval

This research was granted by the Department of Educational Studies, Goldsmiths College, University of London. Ethical approval was granted on 20 May 2020.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my PhD supervisors, Professor Vicky Macleroy and Dr Francis Gilbert, for the support they have offered me during the drafting of this paper. I would also like to acknowledge the feedback provided to me by delegates at the Oxford Ethnography and Education Conference, 2023.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. I use a pseudonym when referring to the school where I work in an attempt to preserve its anonymity.

References

- Adams, T. E., and A. F. Herrmann. 2023. “Good Autoethnography.” Journal of Autoethnography 4 (1): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1525/joae.2023.4.1.1.

- Ahmend, S. 2014. Willful Subjects. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Anderson, L. 2006. “Analytic Autoethnography.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 35 (4): 373–395. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891241605280449.

- Ball, S. J. 2003. “The teacher’s Soul and the Terrors of Performativity.” Journal of Education Policy 18 (2): 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/0268093022000043065.

- Biesta, G. 2007. “Why “What Works” Won’t Work: Evidence-Based Practice and the Democratic Deficit in Educational Research.” Educational Theory 57 (1): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-5446.2006.00241.x.

- Clough, P. 2002. Narratives and Fictions in Education Research. Maidenhead: Open University press.

- Coghlan, D. 2016. “Retrieving a Philosophy of Practical Knowing for Action Research.” International Journal of Action Research 12 (1): 84–107. https://doi.org/10.1688/IJAR-2016-01-Coghlan.

- Coghlan, D., and A. B. Shani. 2021. “Abductive Reasoning as the Integrating Mechanism Between First- Second- and Third-Person Practice in Action Research.” Systemic Practice and Action Research 34 (4): 463–474. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11213-020-09542-9.

- Cook, J. 2013. “Creative Writing As a Research Method.” In Research Methods for English Studies, edited by G. Griffin, 200–217. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Cowan, A. 2021. “‘No Additional Information required’: Creative Writing As Research Writing.” TEXT Journal 25 (2): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.52086/001c.17723.

- Cremin, T., D. Myhill, I. Eyres, T. Nash, A. Wilson, and L. Oliver. 2019. “Teachers As Writers: Learning Together with Others.” Literacy 54 (2): 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/lit.12201.

- Cushing, I. 2021. “Language, Discipline and ‘Teaching Like a champion’.” British Educational Research Journal 37 (1): 23–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3696.

- Cushing, I. 2024. “Social In/Justice and the Deficit Foundations of Oracy.” Oxford Review of Education 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2024.2311134.

- Davis, C. S., and C. Ellis. 2013. “Autoethnographic Introspection in Ethnographic Fiction: A Method of Inquiry.” In Knowing Differently: Arts-Based and Collaborative Research Methods, edited by P. Liamputtong and J. Rumbold, 99–117. New York: Nova Science Publishers.

- Deleuze, G., and F. Guattari. 2003. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Translated by Brian Massumi. London: Continuum.

- Denzin, N. K. 2003. Performance Ethnography: Critical Pedagogy and the Politics of Culture. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Denzin, N. K. 2014. Interpretive Autoethnography. Second ed. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Duoblys, G. October 5, 2017. One, Two, Three, Eyes on Me! https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v39/n19/george-duoblys/one-two-three-eyes-on-me.

- Ellis, C. S., and A. P. Bochner. 2000. “Autoethnography, Personal Narrative, and Personal Reflexivity.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln, 733–768. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Ellis, C. S., and A. P. Bochner. 2006. “Analyzing Analytic Autoethnography – an Autopsy.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 35 (4): 429–449. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891241606286979.

- Ferrante, E. 2013. The Story of a New Name, Translated by Ann Goldstein. New York: Europa Editions.

- Fox, N. J., and P. Alldred. 2015. “New Materialist Social Inquiry: Designs, Methods and the Research-Assemblage.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 18 (4): 399–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2014.921458.

- Freeman, N., and P. Lana. 2015. “Mangia by Nina Freeman, Played by Lana Polansky.” In Videogames For Humans, edited by M. Kopas, 273–316. New York: Instar Books.

- Friedhoff, J. 2014. “Untangling Twine: A Platform Study.” DiGRA’13 7:1–10. http://www.digra.org/wp-content/uploads/digital-library/paper_67.compressed.pdf.

- Gardner, P. 2014. “Who Am I? Compositions of the Self: An Autoethnographic, Rhizotextual Analysis of Two Poetic Texts.” English in Education 48 (3): 230–249. https://doi.org/10.1111/eie.12032.

- Gibb, N. July 21, 2021. Speech: The Importance of a Knowledge-Rich Curriculum. https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/the-importance-of-a-knowledge-rich-curriculum.

- Gilbert, F. 2022. “The Reciprocal Rebellion: Promoting Discussion in Authoritarian Schools.” Changing English 29 (3): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/1358684X.2022.2069547.

- Gilbert, F., and V. Macleroy. 2020. “Different Ways of Descending into the Crypt: Methodologies and Methods for Researching Creative Writing.” New Writing (Routledge) 18 (3): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790726.2020.1797822.

- Haraway, D. 1992. “The Promises of Monsters: A Regenerative Politics for Inappropriate/D Others.” In Cultural Studies, edited by L. Grossberg, C. Nelson, and P. Treichler, 295–337. New York: Routledge.

- Holdstock, S. February 9, 2022. The Doodle. https://makingmeanings.itch.io/the-doodle.

- Hutchings, M. 2015. Exam Factories? The Impact of Accountability Measures on Children and Young People. London: NUT. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309771525.

- Kara, H. 2015. Creative Research Methods in the Social Sciences. London: Policy Press.

- Klimas, C. March 2, 2016. Twine. Accessed November 5, 2022. https://twinery.org/.

- Kulz, C. 2014. “”Structure Liberates?”: Mixing for Mobility and the Cultural Transformation of “Urban children” in a London Academy.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 37 (4): 685–701.

- Kulz, C. 2017. Factories for Learning. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Kulz, C. 2020. “Everyday Erosions: Neoliberal Political Rationality, Democratic Decline and the Multi-Academy Trust.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 42 (1): 66–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2020.1861928.

- Kulz, C., M. Ruth, and M. Kirsty. 2022. “Introduction: A Time and a Place: Doing Critical Qualitative and Ethnographic Work Across an Academised Educational Landscape.” In Inside the English Education Lab: Critical Qualitative and Ethnographic Perspectives on the Academies Experiment, edited by R. McGinity and K. M. C. Kulz, 1–32. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Leander, K. M., and D. Wells Rowe. 2006. “Mapping Literacy Spaces in Motion: A Rhizomatic Analysis of a Classroom Literacy Performance.” Reading Research Quarterly 41 (4): 428–460. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.41.4.2.

- Lemov, D. 2015. Teach Like a Champion 2.0. New york: Jossey-Bass.

- Moll, L. C., C. Amanti, D. Neff, and N. Gonzalez. 1992. “Funds of Knowledge for Teaching: Using a Qualitative Approach to Connect Homes and Classrooms.” Theory into Practice 31 (2): 132–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405849209543534.

- Montfort, N. 2011. “Toward a Theory of Interactive Fiction.” In IF Theory Reader, edited by Kevin Jackson-Mead and J Robinson Wheeler, 25–58. Boston: Transcript on Press.

- Muncey, T. 2010. Creating Autoethnographies. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. http://methods.sagepub.com.gold.idm.oclc.org/book/creating-autoethnographies.

- Noffke, S. E., and <. N. A. I. N. Brennan. 2014. “Educational Action Research.” In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Action Research, edited by S.E. Noffke, Brennan, M., D.Coghlan, David Noffke, and Mary Brydon-Miller, 285–288. Vols. 1-2. London: Sage.

- Page, D. 2017. “The Surveillance of Teachers and the Simulation of Teaching.” Journal of Educational Policy 32 (1): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2016.1209566.

- Perryman, J., S. Ball, M. Maguire, and A. Braun. 2011. “Life in the Pressure Cooker – School League Tables and English and Mathematics Teachers’ Responses to Accountability in a Results-Driven Era.” British Journal of Educational Studies 59 (2): 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2011.578568.

- Richardson, L., and A. S. P. Elizabeth. 2005. “Writing: A Method of Inquiry.” In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by N Denzin and Y S Lincoln, 959–978. London: Sage.

- Rosenshine, B. 2012. “Principles of Instruction: Research-Based Strategies That All Teachers Should Know.” American Educator Spring:12–39. https://www.ibe.unesco.org/fileadmin/user_upload/.

- Rowe, D. E. 2023. “Why Preschool Writing Matters and How Adults Can Support Our Youngest Writers.” International Conference 2023, UKLA. Exeter University, Exeter.

- Sarkar, S. April 24, 2015. Twine Makes Game Development More Accessible, but to Whom? Accessed March 8, 2023. https://www.polygon.com/2015/4/24/8485839/games-for-change-2015-twine-panel.

- Stewart, K. 2010. “Worlding Refrains.” In The Affect Theory Reader, edited by M. Gregg and G. J. Seigworth, 339–353. Durham & London: Routledge.

- Stewart, K. 2014. “Tactile Compositions.” In Objects and Materials: A Routledge Companion, edited by P Harvey, E, Casella, G Evans, C McLean, E. B Silva, N Thoburn, and K Woodward, 119–127. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Street, B. 2003. “What’s ‘New’ in New Literacy Studies? Critical Approaches to Literacy in Theory and Practice.” Current Issues in Comparative Education 5 (2). https://doi.org/10.52214/cice.v5i2.11369.

- Trust, C. 2018. https://carers.org/young-carers-schools. https://carers.org/young-carers-schools.

- Webb, J. 2012. “The logic of Practice? Art, the academy, and fish out of water.” TEXT 16 (Special 14): 1–16. (Special Issue Number 14: Beyond Practice-Led Research)http://www.textjournal.com.au/speciss/issue14/Webb.pdf. https://doi.org/10.52086/001c.31174.

- Whitehead, J. 1989. “Creating a Living Educational Theory from Questions of the Kind, ‘How do I Improve my Practice?’.” Cambridge Journal of Education 19 (1): 41–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764890190106.

- Yandell, J. 2019. “English Teachers and Research: Becoming Our Own Experts.” Changing English 26 (4): 430–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/1358684X.2019.1649087.

- Young, M. 2018. “A knowledge-led curriculum: Pitfalls and possibilities.” Impact Autumn (4): 1–4.

- Young, R. 2019. What is it Writing For Pleasure teachers do that makes the difference?. UK: The Goldsmiths’ Company & The University Of Sussex. https://writing4pleasure.com.